Nationwide Response Issues After an Improvised Nuclear Device Attack: Medical and Public Health Considerations for Neighboring Jurisdictions: Workshop Summary (2014)

Chapter: 8 Reorienting and Augmenting Professional Approaches

Reorienting and Augmenting Professional Approache

Key Points Made by Individual Speakers

• Under conditions of heavy patient load, triaging moderately injured patients first saves three times more victims than saving severely injured patients first.

• MedMap is an important tool for obtaining situational awareness. It posts the path of the plume, transport sites, and the locations of local hospitals and assembly centers through an interactive geographical information system-based electronic mapping.

• Instead of focusing on the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders, mental health professionals should deliver psychological first aid post-incident. Behavioral health providers should be integrated with traditional response provider teams.

• First responders and health care workers need education and training in radiation safety to improve their perception of risks, to ensure they protect themselves and families to reduce health risks, and to improve their performance and decision making during an event.

• If the incident commander decides that high radiation doses to emergency workers are justified, the workers must be made aware of the doses and the adverse health consequences in order to give informed consent before proceeding with the rescue mission.

Throughout the workshop it was evident that many federal resources are available to assist communities, including recently developed systems and technology to give local jurisdictions and responders on the ground a better common operating picture and improved situational awareness. Traditional response protocols may not be enough to address all of the issues caused by an improvised nuclear device (IND) detonation. Additionally, local planners and authorities need to be prepared to

reorient typical approaches to their field after an event with such a magnitude as an IND detonation. Triage approaches may be altered, the mental health manifestations of evacuees and first responders may be different, and additional education in this type of workplace safety and health standards could help responders perform their job duties better.

Norman Coleman, senior medical advisor and chief of the chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear team within the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR), spoke to the importance of a systems-based approach to an IND detonation. When so many different agencies and levels of responders will be involved, having a framework to turn to would help alleviate some of the chaos. As mentioned in Chapter 5, he and colleagues devised the RTR system for responding to mass casualties, with the name an abbreviation for Radiation-specific TRiage, TReatment, and TRransport sites; the purpose of the RTR system is to characterize, organize, and efficiently deploy resources and personnel in appropriate categories (Hrdina et al., 2009). RTR-1 sites are those in which patients have both radiation and physical damage, RTR-2 sites lie in the path of the radioactive plume but do not have physical damage, and RTR-3 sites are spontaneous collection points with neither radiation nor structural damage. The RTR sites are designated by the incident commander in real time with feedback from emergency responders on the ground. At each RTR site, the following functions are performed:

• Identification

• Triage

• Medical stabilization (or provision of palliative care)

• Decontamination

• Transport of victims, many of whom are candidates for the Radiation Injury Treatment Network’s (RITN’s) specialty care

As another system to assist state and local entities in response, Coleman and colleagues also developed a tool called MedMap, also mentioned in Chapter 5, which is used for obtaining situational awareness for responding authorities at the site as well as at the federal level in order to coordinate resources. MedMap posts the location of each RTR

site, the path of the plume, and the locations of local hospitals and assembly centers through an interactive geographical information system-based electronic mapping. Its purpose is to create a seamless common operating picture, both within federal Emergency Support Function (ESF)-8 partners and among their local counterparts, in order to produce a more effective response. Locals can also use the tool to map critical infrastructure and to better coordinate deployments. Coleman also noted that other features can be loaded into MedMap, including hospital occupancy rates, RITN hospitals, nursing homes, schools, Veterans Administration hospitals, weather, and the locations of sites stocked with medical countermeasures.

As John Hick of Hennepin County Medical Center mentioned in Chapter 2, patients with acute radiation syndrome (ARS) resulting from an IND attack will need cytokine treatment within 24 hours. While the federally controlled Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) is designed to warehouse and distribute medical countermeasures in the event of a medical emergency, supplies will not be available to local health care facilities until 1 to 3 days after being requested, which emphasizes the importance of having the resources necessary for an adequate response available at the local level. To make cytokines more readily available and to reduce the cost of replenishing stockpiles, in 2012 Coleman and colleagues proposed the establishment of locally or regionally controlled user-managed inventories (UMIs). Serving as a supplement to SNS, UMIs would stock medical countermeasures that have dual uses (e.g., the same cytokines used for ARS can also be used after routine bone marrow transplants). Those medical countermeasures would be cycled through a local or regional pharmacy so that they would be used during nonemergencies before their expiration date. This would be a cost-effective approach because it would avoid the costs of disposal and repurchase of unused (expired) supplies.

Triaging in an Austere Environment

The magnitude of an IND attack may also dictate that first responders alter their typical triage approach in order to try to save more lives with scarce resources. Coleman described the findings from a triage model he and colleagues developed called the model of resource- and time-based triage (MORTT). This model was developed because conventional triage algorithms make the assumption of unlimited medical re-

sources being available. This alternative was designed as a flexible framework for testing various decisions related to allocating limited resources; however, it should be used to explore prioritizations in advance of an event, not after. When responding to an IND event, scarce resources will be the norm. According to MORTT, triaging moderately injured victims first, then the severely injured victims, followed by the mildly injured (Mod-Sev-Mild) saves 10 percent more lives than conventional triaging systems. The case for treating moderately injured patients first is bolstered by the additional finding that as victim loading increases in relation to resources available (at 10x on the x-axis), the Mod-Sev-Mild triaging system saves three times more victims than does Sev-Mod-Mild (Casagrande et al., 2011). When age and gender are entered into the model, the outcome is unaffected. Although first responders are expected to have a difficult transition in reorienting their approach to triaging away from severely injured first to moderately injured first, they are likely to feel more comfortable knowing that subsequent re-triaging should occur as more medical resources (e.g., hospital beds) become available. Coleman emphasized that continuing re-triaging is necessary, taking into account the ongoing fluctuating amounts of resources and personnel that could become available.

An important refinement to triaging patients in crisis conditions is to deal not only with the patient’s needs, but also with the effectiveness of the intervention (Caro et al., 2011a,b). Coleman asserted that, in a crisis, priority should be given to patients with the highest need and for whom interventions are expected to be most effective. If the available resources are not going to be effective, then it is unfair to others to expend the resources on a high-need patient. Also, depending on the situation and resources at hand, it may be more effective to switch from individual patient-focused outcomes to population-focused outcomes. The goal in this type of rare response, when resource scarcity dictates interventions, should be saving the largest number of lives. As evidenced in the MORTT model, the priority shifts to victims for whom the intervention would be most effective as opposed to those with the most severe injuries (IOM, 2012). The utilitarian goal of providing “the greatest good for the greatest number” (i.e., saving the most lives) should be moderated and balanced by the principle of ethics and fairness in making decisions about lifesaving interventions. It is also important that the standards of care that emerge are standardized across regions; otherwise, hospitals operating next to one another with different parameters become even more chaotic.

Coleman concluded his presentation by noting that while general models such as MORTT are useful, preparation and response are specific to a given city or region. It is important to become familiar with the various tools and systems in advance through education, training, and updates. Deciding on the triage approach for scarce resources requires a difficult conversation and needs community agreement and attention before an incident through preplanning and interactive public discussions.

MENTAL HEALTH IMPLICATIONS OF AN IND

Ann Norwood, a senior associate at the UPMC Center for Health Security, addressed the role of mental health providers in an outlying community approximately 2 weeks post-detonation. She stressed that mental health professionals, like emergency responders, need to reorient their professional approach in the face of an IND attack. Mental health professionals must shift from their standard orientation—diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders—to realizing the near-universal set of psychological responses to an IND attack: fear, shock, horror, and anxiety; a strong urge to be with loved ones; an intense hunger for information, especially about loved ones; a diminished ability to retain and process information (i.e., cognitive narrowing); and uncertainty. As an example, research has shown that 61 percent of people living in outlying communities less than 100 miles from Ground Zero reported substantial stress within days of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks (Schuster et al., 2001).

Norwood emphasized that mental health providers nationwide should turn to delivery of psychological first aid, the purpose of which is to reduce the distress caused by traumatic events and to build short- and long-term adaptive functioning (National Center for PTSD, 2006). Psychological first aid is useful not only for victims, but also for health care workers and first responders. Psychological first aid can be delivered wherever these groups are situated, whether in shelters, field hospitals and medical triage areas, acute care facilities (for example, emergency departments), staging areas, respite centers for first responders and relief workers, emergency operations centers, or crisis hotlines. Norwood recommended that behavioral health providers should be integrated with teams of traditional response providers. They should tap into the natural resilience of survivors and should watch for people who are not resilient

because they will be vulnerable to developing posttraumatic stress disorder and other longer-term mental disorders.

Norwood cautioned against providing mental health consultations to one group of victims: people with stress-related physical symptoms, such as nausea, dizziness, chest pain, and other symptoms of acute anxiety. If such people seek medical help, the first responder or clinician should avoid referring them to a mental health provider. Making a psychiatric referral signifies to these patients that their symptoms are being discounted and they are “all in their head.”

From a mental health perspective, an IND attack is more difficult to respond to than other disasters for several reasons: Radiation is highly feared; it is undetectable to the senses (leaving people ignorant about where they can retreat to for safety); it is poorly understood; it is linked to cancer; it is associated with genetic damage; and it engenders scientific disagreement over what levels are safe. Given the intensity of fear and uncertainty that radiation evokes, hospitals are expected to become magnets for concerned people after an IND blast. People will likely flock to hospitals to be evaluated for radiation exposure, to have medications replaced, to search for a safe haven, and to search for relatives from whom they have been separated. It will be important to deter healthy people from seeking hospital care and refer them either to family support centers for tracking down loved ones or to community reception centers for assessing their radiation exposure.

Further emphasizing Garrett’s earlier point about “socialized preparedness,” Norwood also noted that we need to foster greater levels of personal and family preparedness. In circumstances where it is hard to get people engaged, she suggested reaching out to people who are highly prepared and using them to model preparedness and educate their peers. Research reveals that directly reaching out to people whose preparedness is low is likely to be unsuccessful.

HEALTH AND SAFETY OF EMERGENCY RESPONDERS

Capt. James Spahr, the associate director of emergency preparedness and response of the National Institute Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), began his presentation by describing his agency’s role in certifying personal protective equipment geared for chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear incidents. NIOSH has approved more than 130 different types of makes and models of respirators calibrated against ra-

diation agents. The remainder of Spahr’s presentation concerned challenges to responders and guidance regarding radiation exposures in emergency situations.

Emergency responders summoned to an IND detonation include the obvious—firefighters, police, emergency medical services—plus the not so obvious, i.e., urban search and rescue, utility workers, truck drivers, equipment operators, and debris contractors, among others (OSTP, 2010). One of the greatest challenges is to train the full range of responders in radiation safety in order to make a nuclear event “less scary,” to minimize the responders’ health risks and improve their performance and decision making. Most responders lack training in radiation safety, which likely contributes to the research finding that responders are often reluctant to respond to an event involving significant radiation hazards. Another challenge is to train responders to understand that the severe damage zone has not only radiological hazards, but also numerous physical and chemical hazards, including collapsed structures, heat and fire, broken glass and sharp objects, and downed power lines and ruptured gas lines. Monitoring responders’ radiation doses is challenging. It is accomplished by a combination of area monitors and personal dosimeters. The results then need to be passed up through the chain of command because it will ultimately fall to the incident commander to determine whether radiation levels are safe enough to allow responders to remain in the area.

Another significant challenge for responders during an emergency is to shift away from compliance with radiation limits set forth by the Occupational Safety Health Administration and focus instead on emergency occupational standards and guidelines, which give more discretion when dealing with lifesaving missions. In 1992 the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued radiation guidelines for emergency procedures, which established doses of 25 rem (roentgen equivalent man) as an upper limit for large life-saving operations (EPA, 1992). Because EPA’s guidelines were geared for a nuclear plant accident and not nuclear terrorism, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) modified the policy in 2008. The new policy avoided setting a dose limit for large-scale lifesaving operations after nuclear terrorism (FEMA, 2008). Instead, DHS and the National Council on Radiation Protection (NCRP) based the policy on recommendations from NCRP Commentary No. 19, using a “decision dose” not to exceed 50 rad (0.5 Gy) whole-body dose over a short period of time (NCRP, 2005). A “decision dose” refers to the absorbed radiation dose that triggers a decision by the incident commander about whether to withdraw emergency responders from within or near the inner

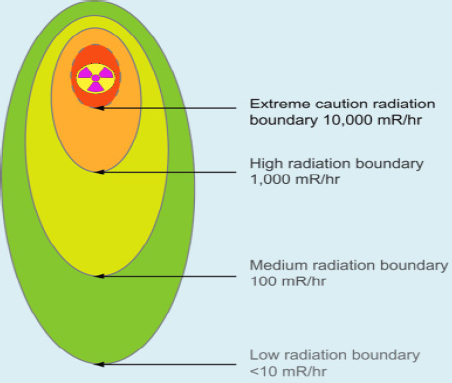

perimeter during the early phase of the response. The NCRP calls for establishing an inner perimeter at an emission rate of 10,000 mR/hr1 and for other perimeters to be set at progressively lower emission rates (see Figure 8-1) (NCRP, 2005). If the incident commander decides that doses above 50 rads to emergency workers are justified, the workers must be made aware of the doses and the adverse health consequences in order to make informed decisions about proceeding with the rescue mission (NCRP, 2010; OSTP, 2010). In other words, worker participation under conditions of high radiation exposure (>50 rads cumulative absorbed dose) during lifesaving missions is voluntary and rests on informed consent. NCRP advises that informed consent documents should be filled out in advance of, rather than during, an emergency. A new guidance document is being developed by DHS to deal specifically with worker safety and health following a nuclear detonation, with expected release in 2013.

FIGURE 8-1 Decision doses.

SOURCE: Presentation by Capt. James Spahr, based on NCRP, 2005.

___________________

1 mR = milliroentgen measurement of energy produced (different from rem, which measures the biological effect of a radiation dose).

Spahr then sought to spotlight NIOSH’s new approach to worker safety and health in public health emergencies. The new approach was motivated by deficiencies in protecting workers at the World Trade Center after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Seeking to foster a culture of safety in disaster response, NIOSH and other federal agencies have created the Emergency Responder Health Monitoring and Surveillance System.2 The system is divided into three phases: (1) pre-deployment (rostering and credentialing workers to ensure that only properly equipped personnel will be selected); (2) deployment (ensuring that all workers receive sufficient onsite training, monitoring, and risk assessment); and (3) post-deployment (conducting exit interviews, health tracking, and writing after-action reports). The intent of the system is to identify formerly unrecognized health hazards, to prevent or mitigate them during the incident, and to track down workers who already were exposed. This new system was successfully field-tested at the Deep Water Horizon emergency operation in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010, during which 55,000 emergency responders across four states were tracked.

Norwood also brought up that health care workers are as deeply unsettled by radiation events as is the greater public. While first responders are typically heroic in crisis situations, survey research has shown that they have a significantly lower degree of willingness to deal with radiation events (Dodgen et al., 2011). Health care workers in hospitals are also hesitant about caring for victims. To support these groups of workers, Norwood recommends educating them about radiation, providing a clear path of action, developing a plan that addresses health care workers’ concerns about the well-being of their loved ones, monitoring the workplace to measure exposure levels, and briefing at the beginning of a rotation.

When responding to an IND event, it will often happen that resources are scarce. Triaging moderately injured victims first saves 10 percent more lives than triaging severely injured first when resources are limited. Attending to the mental health needs of injured and healthy alike is critical to preventing distress and the development of mental disorders like posttraumatic stress disorder and depression, which are highly preva-

___________________

2See http://nrt.sraprod.com/erhms (accessed May 12, 2013).

lent after disasters or emergencies. Mental health professionals should focus on delivering psychological first aid to victims and the “worried well” alike. The mental and physical health of emergency workers is also highly important. In the past, EPA set an upper limit on the dose of radiation allowed for an emergency worker. Because the limit was designed for nuclear accidents, DHS modified the policy to also deal with nuclear terrorism. The new policy does not set an upper limit on dose, but rather sets a dose of 50 rads as a “decision dose” requiring incident managers to make a decision about whether to evacuate responders from the area. If the manager believes that doses above 50 rads are justified for life-saving missions, emergency workers must be notified, and they must give informed consent to proceed with the life-saving mission.