Developing a 21st Century Neuroscience Workforce: Workshop Summary (2015)

Chapter: 1 Introduction and Overview

From its very beginning, neuroscience has been fundamentally interdisciplinary. As a result of rapid technological advances and the advent of large collaborative projects, however, neuroscience is expanding well beyond traditional subdisciplines and intellectual boundaries to rely on expertise from many other fields, such as engineering, computer science, and applied mathematics. This raises important questions about how to develop and train the next generation of neuroscientists to ensure innovation in research and technology in the neurosciences. In addition, the advent of new types of data and the growing importance of large datasets raise additional questions about how to train students in approaches to data analysis and sharing. These concerns dovetail with the need to teach improved scientific practices ranging from experimental design (e.g., powering of studies and appropriate blinding) to improved sophistication in statistics. Of equal importance is the increasing need not only for basic researchers and teams that will develop the next generation of tools, but also for investigators who are able to bridge the translational gap between basic and clinical neuroscience.

_________________________

1The planning committee’s role was limited to planning the workshop, and the summary has been prepared by the workshop rapporteurs (with acknowledgment of the assistance of staff as appropriate) as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop. Statements, recommendations, and opinions expressed are those of individual presenters and participants, and are not necessarily endorsed or verified by the Institute of Medicine, and they should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus.

WORKSHOP OBJECTIVES

Given the changing landscape resulting from technological advances and the growing importance of interdisciplinary and collaborative science, the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM’s) Forum on Neuroscience and Nervous System Disorders convened a workshop on October 28 and 29, 2014, in Washington, DC, to explore future workforce needs and how these needs should inform training programs (see Box 1-1 for the Statement of Task). Workshop participants considered what new subdisciplines and collaborations might be needed, including an examination of opportunities for cross-training of neuroscience research programs with other areas. In addition, current and new components of training programs were discussed to identify methods for enhancing data handling and analysis capabilities, increasing scientific accuracy, and improving research practices. Lastly, the roles of mentors, mentees, training program administrators, and funders in the development and execution of revised training programs for new and current researchers were considered.

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

The following report summarizes the presentations from expert speakers and discussions among workshop participants, starting with a review of the current and future diversity of neuroscience in this chapter. The ensuing chapters provide an overview of the challenges and opportunities in training related to basic research, tool development and big data (Chapter 2), protocol design and experimental rigor (Chapter 3), transdisciplinary research (Chapter 4), and translational research (Chapter 5). Cited references, the workshop agenda, a list of registered attendees, and participant biographies can be found in the appendixes of this report.

BOX 1-1

Statement of Task

- Explore future workforce needs in light of new and emerging tools, technologies, and techniques.

- Consider what new subdisciplines and/or collaborations with other fields might be needed moving forward.

- Describe opportunities and challenges for cross-training of neuroscience research programs with other areas (e.g.,

engineering, computer science, mathematics, physical sciences) and across research environments (e.g., academia, industry).

- Identify current components of training programs that could be leveraged and new components that could be developed that might lead to the following:

- Greater interdisciplinary and collaborative approaches.

- Enhanced data handling and analysis capabilities.

- Increased scientific accuracy and reproducibility.

- Improved awareness of ethical research practices.

- Examine roles of training program funders (e.g., government, fellowships), administrators, mentors, and mentees in developing and executing revised training programs to meet the needs outlined above.

- Consider mechanisms for updating researcher competencies at multiple levels (e.g., postdoctoral, independent investigators) to meet the needs outlined above.

THE CURRENT AND FUTURE DIVERSITY OF NEUROSCIENCE

There are two key considerations in developing a neuroscience workforce for the 21st century: the intellectual and scientific progress in the field is shaping the need for new training, and challenges related to funding and advancement opportunities make it increasingly important to prepare trainees for a range of careers. To set the stage for discussions about developing training programs to prepare trainees for the future of neuroscience and ensuring that the field has individuals with the appropriate backgrounds, Story Landis, former director of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), described the current state of neuroscience, including both the challenges and potential opportunities. The remainder of the workshop summary focuses primarily on the new training needed to continue to make intellectual and scientific progress in neuroscience.

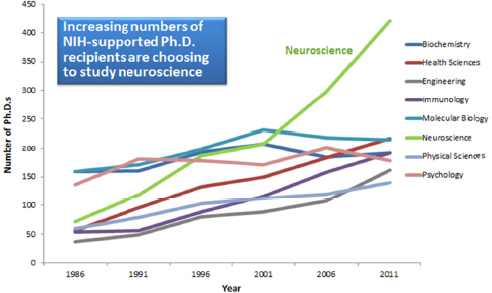

The field of neuroscience finds itself in the midst of an era of unprecedented growth and popularity, she noted. For the past decade, the number of new neuroscience Ph.D.s has significantly outpaced every other life sciences discipline, with the next most popular field producing only half as many graduates per year (see Figure 1-1). Relative to other fields, neuroscience funding is also on the rise. In 2014 the National Institutes of Health (NIH) funded more neuroscience research than cancer

research for the first time in its history, noted Landis. Yet, she added, despite living in what can be considered a “golden age” of neuroscience, there is a feeling of doom and gloom regarding career prospects.

Challenges for the Next Generation of Scientists

Over the past decade, the United States has seen an overall decrease in scientific research and development spending (when adjusted for inflation), particularly for the life sciences (Macilwain, 2013; Rockey and Collins, 2013; Wadman, 2013). This decrease in spending was exacerbated by the sequestration in 2013, in which major funding agencies, such as NIH and the National Science Foundation (NSF), were affected by additional budget cuts, directly affecting the number of new and ongoing research projects that could be supported. The current financial climate, coupled with the increasing size of the workforce, has put the goals of obtaining a faculty position and establishing a laboratory out of reach for the vast majority of graduates. The reality is that less than one in five Ph.D. graduates will go on to take a research faculty position, despite such a position being reported as the goal of more than 50 percent of graduate students (Cyranoski et al., 2011; Sauermann and Roach, 2012). Landis referred to this disparity as the “training valley of death.”

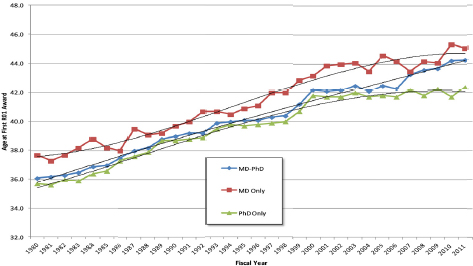

Even when trainees do transition into research faculty positions, data show that career trajectories start later with each passing year. The average age at which those with a Ph.D. in the life sciences receive their first R012 grant has been steadily increasing for decades, rising from age 36 in 1980 to age 42 in 2011 (see Figure 1-2). By comparison, said Terry Sejnowski, professor of the Computational Neurobiology Laboratory at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, the average age of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) engineers who put the first man on the moon was 26, meaning that they were 18 when President Kennedy gave his famous “moonshot” speech.

Training and Career Path Diversity

To address the uncertain career prospects faced by young trainees, Landis pointed to two solutions that could be executed in parallel. First, she said there is a moral imperative to provide students with opportunities for training in non-academic careers. Second, she suggested that the

_______________________

2See http://grants.nih.gov/grants/funding/r01.htm (accessed October 28, 2014).

FIGURE 1-1 Number of Ph.D.s awarded on an annual basis in different fields of science and engineering.

NOTE: NIH = National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Story Landis presentation, NINDS, October 28, 2014.

FIGURE 1-2 Average age of principal investigators with M.D.-Ph.D., M.D., or Ph.D. at the time of first R01 equivalent award from the National Institutes of Health, fiscal years 1980 to 2011.

SOURCE: Story Landis presentation, NINDS, October 28, 2014, based on materials from a blog post by Sally Rockey. http://nexus.od.nih.gov/all/2013/11/14/%20whats-trending-in-phd-fields (accessed October 28, 2014).

field needed to take a serious look at the idea of “right-sizing” training—gradually reducing the number of students entering Ph.D. programs—an idea that has been around for a while and was recently addressed in a high-profile commentary written by National Cancer Institute director Harold Varmus and others (Alberts et al., 2014). Along with right-sizing, Alberts and colleagues (2014) suggested limiting the number of years a postdoctoral fellow can be supported by federal grants, increasing the number of permanent staff scientist positions at universities, and reversing the trend over the past few years of supporting trainees with investigators’ research grants in the form of research assistantships. Several workshop participants voiced similar suggestions, saying that training grants, which are peer reviewed, allow students and postdoctoral researchers the freedom of instigating their own projects and provide experience that can help them flourish in the early stages of their careers. Alberts and colleagues (2014) further suggested that trainees be offered more opportunities to explore non-academic careers through extracurricular courses, internships, conferences, or workshops (see Box 1-2).

BOX 1-2

Examples of Non-Academic Careers and Training Opportunities

Science Advocacy and Policy

- American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Science and Technology Policy Fellowship

- Presidential Management Fellowship

- Hellman Fellowship in Science and Technology Fellowship

- Office of Science and Technology Policy Student Volunteer Program

- Society for Neuroscience Early Career Policy Fellows Program

- National Academies Christine Mirzayan Science & Technology Policy Graduate Fellowship Program

- The Optical Society and International Society for Optics and Photonics Arthur H. Guenther Congressional Fellowship

Science Communication

- AAAS Mass Media Fellowship

- Master’s-level programs in Science Writing at the University of California, Santa Cruz; New York University; Johns Hopkins University

- NeuWrite program at Columbia University

- Director of Communication for Neuroscience Institutes/Programs/Universities (Public Relations)

- Director of Outreach: assembles programs for K–12 education and Brain Awareness Week

Science Publishing

- Journal of Emerging Investigators: Students in the Harvard “Paths in DMS (Division of Medical Sciences)” program science-writing path run an online journal dedicated to publishing outstanding high school science fair research projects. The volume of quality submissions has spurred the expansion of the journal to other universities.

Teaching

- Northwestern University Searle Center for Teaching Excellence certificate program

Research in Biotechnology and Pharmaceutical Industry

- Drexel University Master of Science Program in Drug Discovery and Development (see Chapter 5 for more details)

- Postdoctoral fellowships are offered by biotechnology companies such as Amgen, Biogen IDEC, Chiron, GE Healthcare, Genentech, Genzyme, Gilead, Millennium, Serono, and Siemens and pharmaceutical companies such as Abbott, AstraZeneca, Aventis, Eli Lilly, Johnson & Johnson, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Wyeth.

Government

- Program Officer at the National Institutes of Health or National Science Foundation

Business and Consulting

- Consultant (e.g., McKinsey & Company)

Law

- Technology Transfer Specialist at Universities

- Intellectual Property (Patent) Law

Disease Foundations

- Research and Scientific Officer (e.g., Alzheimer’s Association, Simons Foundation, and National Multiple Sclerosis Society)

Data Curation

- Data Curators

NOTE: The items in this list were addressed by individual participants and were identified and summarized for this report by the rapporteurs. This is not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

Several workshop participants noted that this can be a complex challenge because some mentors might not see the value in such opportunities and view any time that trainees spend away from the bench as time wasted. Two graduate students and a postdoctoral researcher said they, like many of their peers, are hesitant to pursue faculty positions because of the perception that faculty are overstressed and underpaid. Sofia Jurgensen, a postdoctoral researcher at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, said that students and postdocs need more freedom to explore such careers and gain real-world experience during their training periods. Marguerite Matthews, a postdoctoral researcher at Oregon Health & Science University, shared Jurgensen’s sentiment, adding that she has heard many of her fellow trainees who are considering non-academic careers despair that all they know is how to carry out research. Most trainees do have transferrable skills—project management, communication, teaching—but what they lack, said Matthews, is the recognition of the value of those skills and the opportunities to develop them into satisfying careers. Several workshop participants noted the importance of the role for institutions to facilitate the exploration of non-academic careers among students (see case example of Harvard University’s “Paths in DMS [Division of Medical Sciences]” program in Box 1-3). In addition, a few workshop participants suggested that allowing students to have more than one mentor might be beneficial to help facilitate this diversity.

BOX 1-3

Program Example: Harvard University’s Paths in DMS (Division of Medical Sciences) Programa

David Lopes Cardozo, associate dean for graduate studies and director of the Division of Medical Sciences at Harvard University, shared his experience counseling trainees in career decisions. Roughly half of his students over the past few years have expressed interest in non-academic careers. Cardozo directs a program at Harvard called “Paths in DMS” that works with trainees to navigate nonacademic career opportunities in neuroscience. The program takes four primary approaches to formalizing training in career diversity:

- Institutional Buy-In

Obtaining approval for career diversity training from the highest levels of the school sent a message to students, especially those experiencing anxiety and despair over their career prospects, that there is no stigma associated with non-academic careers. Important positions such as journal editors, policy makers, and sci-

-

ence communicators all need to be filled with well-educated people, and the university recognizes that training people to succeed in those positions is part of its mission.

- Career Tracks

The program encourages students to organize into career tracks and provides relevant coursework to prepare them to enter specific careers. The six paths are biotechnology/pharmaceutical, consulting/business, patent law, science writing and publishing, education and public outreach, and government and public sector. In addition, the program is rolling out an online course that introduces students to the full variety of career options. - Network and Mentoring Events

Alumni and friends of the program—leaders from local companies—are eager to help and are much better prepared to mentor students in finding appropriate non-academic careers than faculty members who often have no experience with jobs outside academia. - Certification

Students completing the curriculum associated with each path earn a certificate that demonstrates to potential employers the students’ commitment to a specific career track.

_________________________

aSee http://www.hms.harvard.edu/dms/resources/paths.html (accessed October 29, 2014).

SOURCE: David Lopes Cardozo presentation, Harvard University, October 29, 2014.

Training a New Generation of Students

Marie-Francoise Chesselet, professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and Thomas Insel, director of the National Institute of Mental Health, noted that the next generation of neuroscientists is truly a “new breed” with respect to this generation being the first to grow up with the technological advances that we have today, namely the Internet. Given this experience, they have different approaches to learning, working with information, and overall social interactions, said Chesselet. A few participants added that from their perspective, the new generation of digital natives often lack the oral and written skills that were seen in earlier generations. Darcy Kelley, professor of biological sciences at Columbia University, agreed, stating that at her institution second-year neuroscience graduate students complete a qualifying exam, which is their thesis proposal. She noted that, in addition to working with an in-house professional writing consultant, her department hired a pro-

fessional non-fiction science writer to help develop the writing skills of students. Several participants stressed that program administrators should be aware of the characteristics of this new generation of neuroscientists when modifying their training programs.

TOPICS HIGHLIGHTED DURING PRESENTATIONS AND DISCUSSIONS

Given the changing intellectual and scientific landscape within the field of neuroscience, trainers (program directors, funding bodies, etc.) seek to develop new courses and training vehicles to prepare students in the best practices in scientific research. Workshop co-chairs Huda Akil, professor of neurosciences at the University of Michigan, and Stevin Zorn, executive vice president of neuroscience research at Lundbeck Research USA, challenged participants to think deeply about the nature of the field of neuroscience. Akil asked workshop participants to consider how neuroscientists might define themselves in terms that are not so rigid that the spirit of being a neuroscientist is lost. Zorn’s questions drilled down further into neuroscience’s identity. Is neuroscience a discipline? Is it an interdisciplinary science? How do we train students to work across disciplines to ensure innovation going forward?

Throughout the workshop, discussions focused primarily on the changing needs and opportunities of graduate neuroscience programs, given the growing importance of interdisciplinary and collaborative science and technological advances in the field. Individual participants discussed a number of central themes, summarized below and expanded on in succeeding chapters. Individual participants also identified areas of core competence in which trainees would benefit from training (see Box 1-4).

BOX 1-4

Suggested Core Competencies for Neuroscience Trainees Presented by Individual Speakers

- Ethics

- Mentoring

- Written and oral communication

- Knowledge of general neuroscience literature and deeper knowledge of subdiscipline literature

- Lab and office management

- Grant-writing skills

- Teaching

- Experimental rigor

- Protocol design (randomization, blinding, sample size calculations)

- Common sense and intuition about data

- Statistical reasoning

- Computer programming (matrix laboratory [Matlab], R, Python, Apache, Hadoop)

- Computer modeling

- Algorithm development

- Data visualization

- Data analysis (regression, multivariate data, multidimensional data, cloud computing, feature extraction, versioning)

- Data literacy (data rights, data licenses)

- Data management (data formats, data platforms)

- Data sharing (application programming interfaces, web scraping, data repositories)

- Tool development (knowledge in physics and engineering)

- Tool implementation (knowledge of optics, genetics, molecular biology)

- Translational science (biomarkers, stem cells, behavioral assays)

- Clinical science (neurobiology of disease)

NOTE: The items in this list were addressed by individual participants and were identified and summarized for this report by the rapporteurs. This is not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

- Basic Research

Basic research is the backbone of the neuroscience enterprise, according to Story Landis; without discoveries of fundamental principles of how neurons and the brain work, clinical treatments are not possible. Participants discussed the importance of making trainees aware of the need to create a balance among basic, clinical, and translational research using an interdisciplinary approach. - Experimental Rigor and Quantitative Skills

Many participants discussed the need for improved training in experimental design and rigor, and noted that without these critical elements, studies are difficult to replicate, which undermines the entire scientific process. In addition, several workshop participants noted that the lack of quantitative skills exacerbates this problem. Participants listed many of the causes of irreproducibility (e.g., poor understanding of statistics, unreliable resources such as cell lines and antibodies, and lack of transparency of re-

-

porting methods and raw data in journals) and suggested strategies and opportunities for enhancing the training of students in these areas. The most important skill, argued one participant, is statistical reasoning, which comes only from an intuitive understanding of probability. Participants discussed innovative approaches to teaching quantitative skills to graduate students and postdoctoral fellows and the need to increase collaborations with expert statisticians.

- Next-Generation Tools and Technologies

Powerful new tools are allowing neuroscientists to peer deeper into the workings of the nervous system than ever before. Participants discussed the skills and training necessary to keep up with the already rapid pace of innovation, and opportunities for training students not only in using next-generation tools, but in thinking deeply about their limits and how best to deploy them. Several participants discussed the importance of allowing students to explore external resources outside their institution to learn new techniques from experts in the field and creators of the technology. - Data Handling and Analysis

The era of big data in neuroscience has arrived and brought with it numerous opportunities for powerful analyses of the voluminous data produced by neuroscience’s new tools. Along with those opportunities come challenges in the three main aspects of data handling: data literacy, data management, and data sharing. Several workshop participants discussed specific challenges in these areas, which include developing common data standards and standardized platforms; learning the etiquette regarding the sharing of data; determining which data should be shared; assigning credit to data sharers; and determining efficient methods to annotate data with all of the metadata needed to understand the experimental context. Many participants also described the skills needed to integrate different data types and analyze multidimensional datasets. - Transdisciplinary Neuroscience

As neuroscience becomes more expansive, individuals with skills and knowledge from nearly every discipline of science are needed to work together on increasingly complex projects. Several participants noted that it is in this space where innovation will arise and where there are opportunities to train scientists to

-

work toward a sum greater than the collected parts. For example, developing new tools and technologies requires collaboration with material scientists, chemists, and myriad types of engineers; analyzing multidimensional data requires statisticians and informaticians; and drug development requires clinical experts. To facilitate innovation in the field, several participants discussed the importance of incentivizing a team science approach in neuroscience, and providing students with hands-on experience working in transdisciplinary teams.

- Translational Neuroscience

Workshop participants discussed ways to make all neuroscience trainees aware of the steps required to translate a basic research discovery into a treatment, regardless of their specific role in the process. Several participants also discussed the recent transition within the pharmaceutical industry to focus on rare diseases with a known genetic component that can be exploited to identify biomarkers as a way to stratify patients—a critical step in testing and validating new treatments. Lastly, the need to build strong interdisciplinary teams to conduct translational research was noted by many participants. - Bridging the Gap Between Basic and Clinical Science

Although basic neuroscience has long relied on clinical science to validate and deploy treatments based on fundamental discoveries of the nervous system, a few participants noted that there is a surprising disconnect and lack of cross-training between the two fields. A workshop participant stated that the consequences of the lack of cross-training include inefficient attempts to translate basic findings into treatments and missed opportunities to leverage the clinical setting for important basic research. Opportunities for cross-training noted by a few workshop participants include additional neurobiology of disease and other clinically focused courses, increased availability of clinical rotations to neuroscience graduate students, increased opportunities for clinicians to be exposed to basic neuroscience courses and hands-on research experience, and interdepartmental teams focused on shared clinical goals involving both M.D.s and Ph.D.s (e.g., Parkinson’s disease centers). - Non-Academic Career Paths and Training Models

As neuroscience Ph.D.s continue to pursue career paths beyond academia, participants discussed opportunities available to train-

-

ees to explore such tracks in graduate programs and postdoctoral fellowships. In addition, several participants reviewed alternative models of training beyond the traditional Ph.D. programs, including certificate programs, M.S. programs, and a proposed doctor of neuroscience training program.

- Training of Neuroscientists Versus Training in Neuroscience

Throughout the workshop, many participants asked if it were an unreasonable expectation for trainees to be knowledgeable in each of the many subfields of neuroscience. For example, should students with a cellular and molecular focus also need to have deep knowledge in cognitive and systems neuroscience or techniques like functional magnetic resonance imaging? Would students be better off choosing subfield tracks within graduate school? Other ways of creating tracks to cater to the many skill sets and aspirations of trainees were also addressed by participants. Can there be separate tracks for students who are set on careers in academic research and for students who want to develop expert knowledge about fundamental basic neuroscience versus traditional neuroscience? Are separate programs needed for the training of neuroscientists and for training in neuroscience?