Opportunities and Approaches for Supplying Molybdenum-99 and Associated Medical Isotopes to Global Markets: Proceedings of a Symposium (2018)

Chapter: 7 Molybdenum-99 Supply Sustainability

7

Molybdenum-99 Supply Sustainability

Historically, reactor operators have charged suppliers of molybdenum-99 (Mo-99) only for the marginal operating costs associated with target irradiation and not for costs related to reactor general operation, maintenance, and decommissioning (OECD-NEA, 2010). These costs were absorbed by the governments that own the reactors because the reactors were constructed for purposes other than medical isotope production. International organizations such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Nuclear Energy Agency (OECD-NEA) have recognized that as medical isotope production is progressively becoming a larger part of reactors’ workloads, the historic pattern of government subsidization has proven to lead to Mo-99 market sustainability issues. To create a sustainable Mo-99/Tc-99m market, the High-Level Group on the Security of Supply of Medical Isotopes agreed on six principles in 2011 (OECD-NEA, 2011), one of which is full cost recovery (FCR). FCR was a central topic of discussions at the symposium.

Mr. Jan Willem Velthuijsen (PricewaterhouseCoopers) noted that FCR is not a price-setting tool but rather a methodology to define cost elements and determine the cost associated with Mo-99 production. He added that private industry would go beyond implementing FCR to make profit.

GOVERNMENT SUBSIDIZATION OF MOLYBDENUM-99 PRODUCTION

Mr. Velthuijsen provided the economist’s perspectives on the problems caused by government subsidization of Mo-99 production:

- Welfare loss. When Mo-99/Tc-99m prices remain low due to government subsidies, there is little incentive to use Mo-99/Tc-99m efficiently. Inefficient utilization of Mo-99/Tc-99m leads to several problems including increasing radioactive waste.

- Transfer of welfare. Taxpayers pay for the subsidies provided by governments in countries with reactors used for Mo-99 production. Healthcare consumers in countries that consume Mo-99/Tc-99m without producing it domestically benefit disproportionately from the subsidies.

- No incentive for new capital through private investments. Because Mo-99 prices remain low, new Mo-99 producers struggle to ensure a viable business case with private funding alone.

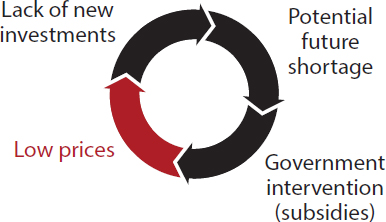

Mr. Velthuijsen recognized that governments still have large incentives to subsidize Mo-99 production to ensure availability. For example, delay of private investments in Mo-99 production (either to support new production or maintenance and upgrades at existing Mo-99-producing facilities) could lead to governments stepping in and offering the needed funds to ensure that no shortages occur. This, in his view, starts a vicious cycle of continued subsidy provision (Figure 7.1).

Uneven subsidization of the supply is also problematic. Mr. Velthuijsen explained that if one supply chain participant is still being subsidized by its government, existing nonsubsidized suppliers are forced to lower the price for which they sell Mo-99 and therefore are not able to earn back their investments for maintenance and upgrades of the production facilities or for conversion from highly enriched uranium (HEU)- to low-enriched uranium (LEU)-sourced production. Eventually, these nonsubsidized suppliers face the risk of being pushed out of the market. New potential suppliers who plan to enter the market at FCR face the same challenges.

Implementation of FCR would lead to increases in prices of Mo-99/Tc-99m, medical isotopes that have traditionally been underpriced. Mr. Velthuijsen noted that the market’s willingness to increase prices depends on availability of alternatives to Mo-99/Tc-99m imaging, pass-through of price increases along the supply chain, and willingness to pay more for Tc-99m imaging.

PROGRESS TOWARD FULL COST RECOVERY

Evaluating the progress made by existing producers toward FCR is difficult because of the large variability in the ownership structure of production facilities such as research reactors used to produce Mo-99. Some of the reactors currently used for Mo-99 production are publicly owned. For example, Mr. Velthuijsen noted that HFR (Netherlands) is owned by the European Commission; OPAL (Australia), Maria (Poland), SAFARI-I (South Africa), and RA-3 (Argentina) are owned by national governments. LVR-15 (Czech Republic), BR-2 (Belgium), RIAR (Russia), and Karpov (Russia) are owned by research institutes that are indirectly controlled by the government.

Since introducing the concept of FCR in 2011 (OECD-NEA, 2011) and guidance for FCR implementation in 2012 (OECD-NEA, 2012b), OECD-NEA has twice reviewed progress made by supply participants toward implementing FCR: in 2012 (the report was released in 2013, see OECD-NEA, 2013) and more recently in 2014 (OECD-NEA, 2014b).

The 2012 review found that most reactor operators and processors are gradually implementing FCR for Mo-99 production, but progress toward FCR is uneven. According to the OECD-NEA report, Australia and South Africa are the two countries self-reporting full implementation of FCR. Little additional progress was made from 2012 to 2014 in implementing FCR. This led the OECD-NEA to develop the Joint Declaration on the Security of Supply of Medical Radioisotopes (Sidebar 7.1). The purpose of the Joint Declaration was to “provide a more formal and coordinated political commitment by governments of the countries participating in the HLG-MR that would foster the necessary changes needed across the supply chain, both in producing and user countries.”

Information for OECD-NEA’s review on implementation of FCR is obtained through self-assessments from

SOURCE: Jan Willem Velthuijsen, PwC, Europe.

Mo-99 supply chain participants. Mr. Velthuijsen pointed out that self-assessments are not entirely reliable or representative of the countries’ progress toward FCR because there is no transparency in the methodology used to assess it and/or each country may interpret FCR differently. Also, there is no auditing in place to ensure that the self-assessment is accurate. Mr. Velthuijsen outlined several ways that governments can help with implementation of FCR in the Mo-99 market, for example, by auditing supply chain participants for implementation of FCR or earmarking government subsidies for research performed in reactors that also produce Mo-99. The willingness of the supply chain participants to be subject to government auditing for FCR compliance was not discussed at the symposium.

Mr. Velthuijsen offered his views on the status of some existing and new Mo-99 production projects that appear not to comply with the FCR principle:

- Belgium’s BR-2 receives support from the government for waste management and security of the reactor.

- Netherlands’ HFR reactor received a subsidy for its last refurbishment.

- Argentina’s RA-3 reactor receives support from the government for capital expenditures and waste management. The new RA-10 reactor is paid for with government funds.

PERSPECTIVES ON FULL COST RECOVERY

Several symposium participants offered comments on their company’s or organization’s views on FCR. These comments highlight the range of anticipated differences in implementation of FCR in the Mo-99/Tc-99m supply market in the future.

-

Existing global producers (ANSTO, NTP, IRE, Curium) highlighted the importance of realistic pricing of Mo-99/Tc-99m and of FCR being implemented throughout the supply chain. They all noted some progress toward FCR at the reactor level since the principle was issued by OECD-NEA.

Mr. Jean-Michel Vanderhofstadt said that IRE is negotiating contracts with irradiating facilities based on FCR. To his knowledge the only cost not covered for the irradiation services that IRE receives is initial capital investments for building the reactors because they were built for other purposes many years ago. He added that because of FCR, irradiation costs have increased 400 percent over the past few years. Russia’s Oleg Kononov (Karpov Institute) provided a similar comment, stating that for Mo-99 production in the WWR-c reactor, the only costs not expected to be recovered are the costs for building the reactor.

- Some representatives of new projects that involve construction of new facilities dedicated to medical isotope/Mo-99 production said that implementation of FCR is crucial to the success of their projects. These representatives included Jim Harvey (NorthStar), Katrina Pitas (SHINE), Carolyn Haass (NWMI), Kennedy Mang’era (CIIC), and Ken Buckley (TRIUMF). Mr. Risovaniy (Rosatom) agreed that implementation of FCR for the aqueous homogeneous reactor project that involves construction of a new production facility is essential.

- Implementation of FCR for projects that involve construction of new reactors differed based on whether the reactor to be constructed will be dedicated to medical isotope production or is also intended for research activities.

- Construction of the multipurpose RA-10 reactor in Argentina is subsidized by the Argentinian government.

- Phase 11 of the PALLAS reactor in Netherlands, which will be dedicated to Mo-99 production, is funded by the Department of Economic Affairs and the province of North Holland. The loans received for Phase 1 need to be repaid during subsequent phases.

- Representatives of projects that involve medical isotope production as a secondary purpose and power generation as a primary purpose claimed that most production costs will be recovered by power generation. Two such projects were described at the symposium: Rosatom’s project to produce Mo-99 in RBMK reactors and Flibe Energy’s project to produce Mo-99 in thorium reactors.

___________________

1 Phase 1 involves design, construction licensing, and development of the business case to secure the financing for the next phase.