Strengthening the U.S. Medicolegal Death Investigation System: Lessons from Deaths in Custody (2025)

Chapter: 5 Forensic Pathology and Cause and Manner of Death: Challenges and Opportunities

5

Forensic Pathology and Cause and Manner of Death: Challenges and Opportunities

To make correct determinations of cause and manner of death, forensic pathologists must collect and interpret information from many sources. This chapter uses a case study presented to the committee at an information-gathering session to set the stage for an examination of topics including the scientific bases for determinations of cause of death in death-in-custody cases; ensuring that forensic pathologists are protected from factors that may bias their diagnosis, including undue influence; and the collection and review of information necessary to make valid determinations of cause and manner of death.

ESTABLISHING CAUSE AND MANNER OF DEATH: A DEATH-IN-CUSTODY CASE STUDY

At the committee’s February 2025 meeting, Deland Weyrauch, a deputy medical examiner for the Montana Medical Examiner’s Office in Billings, Montana, presented the case of a 24-year-old man who died in a tribal prison and whose death was ultimately determined to be a suicide. The case illustrates the complexity of medicolegal death investigations and offers a useful framework against which to consider challenges and opportunities

for forensic pathology and the medicolegal death investigation (MLDI) system.1

As a first step in all death investigations where an autopsy is performed, a body must be transported to an autopsy facility. In the Weyrauch case, the local coroner transported the body from the location of the death in northeast Montana to the Montana Medical Examiner’s Office in Billings in south central Montana, a 4.5-hour drive.

Weyrauch collected preautopsy information from law enforcement and preincarceration medical records. This material revealed that after an emergency room visit, the decedent had been in a tribal prison for 2.5 days for aggravated disorderly conduct, had a history of schizophrenia and methamphetamine use, and was reportedly in his normal state of health 20 minutes before he was found unresponsive.

The decedent had visited the emergency department because of a suspected overdose of psychiatric medications. There, he was treated per poison control recommendations and showed no clinical, diagnostic testing, or laboratory findings concerning serious intoxication or physiological derangement. He was subsequently discharged to law enforcement and died in prison.

Weyrauch proceeded with an autopsy. In his initial physical examination of the body, Weyrauch found no obvious signs of traumatic injury, struggle, or self-harm. Photographs were taken to document all visible injuries, which included scrapes and healing bruises.

Procedures were used to dissect every neck muscle individually to look for subtle bleeds and signs of neck compression. The examination yielded no indications (such as petechial hemorrhages) that would support a finding of traumatic asphyxia (such as neck or chest compression or airway obstruction resulting in a deficient supply of oxygen to the body). Having found no indications of obvious disease or injury, Weyrauch proceeded to conduct a microscopic tissue examination, which revealed myoglobin casts in the kidneys. Recognizing that rhabdomyolysis (a condition where muscle tissue breaks down and releases myoglobin, potassium, and other intracellular contents into the bloodstream) is the only way to get such

___________________

1 In correspondence to the committee dated May 16, 2025, Weyrauch suggested that this type of case is quite rare (delayed toxicity death related to rhabdomyolysis that also happens to occur in custody). He noted that, in general, “1) in-custody deaths generally involve more time-intensive investigation because they are higher profile/higher scrutiny, carry a burden to rule out many diseases/injuries, may have complex circumstances, and generally have more documentation to review such as prison video, body cam footage, custodial facility records, etc. and 2) we frequently investigate deaths that are equally as complex as the one I presented, but are very different in the details,” estimating that “somewhere around 1/20 to 1/30 medical examiner cases require a similar degree of time/effort/resources.”

casts, Weyrauch sent a tissue sample for laboratory testing to confirm the diagnosis. The test was positive, and Weyrauch proceeded to consult clinical resources to clarify whether rhabdomyolysis could stop a person’s heart in the absence of outward symptoms. His research found that symptoms of rhabdomyolysis “may be vague or absent in up to 50 percent of patients”; with this condition, the muscles spill potassium into the blood and, with extensive muscle damage, can trigger cardiac arrest by arrythmia.2

Weyrauch now had what he believed to be a plausible diagnosis for mechanism of death. However, as the underlying causes (etiologies) of rhabdomyolysis are numerous (see Table 5-1), cause and manner of death remained to be determined. Haloperidol and atypical antipsychotics as a drug class have specifically been implicated and associated with the condition, and in medical records from the emergency department, “per family report,” the decedent’s refill of psychiatric medications “included over 80 tablets of haloperidol and over 60 of a drug called olanzapine, which is an atypical antipsychotic.” Postmortem toxicology results indicated that these two drugs were the only active drugs in the decedent’s system; methamphetamine was detected in a urine sample, but was not present in the blood, suggesting methamphetamine had been used while he was in the community but had been completely metabolized out of the blood during his time in prison. The decedent had not been administered any medication while in prison in the days leading up to death, indicating the postmortem haloperidol and olanzapine levels were attributable to ingestion prior to incarceration.

Physical restraint may lead to rhabdomyolysis; given the decedent’s history of psychiatric illness and Weyrauch’s knowledge of deaths in custody, he thought it advisable to investigate whether the decedent had been physically restrained. He “reviewed reports, made phone calls, [and] crucially obtained all the video the prison had showing the decedent, from intake to [prison staff] ushering him into his cell.” Staff “did put him in [a] wheelable restraint chair,” but, Weyrauch wondered, “did being in this restraint chair contribute to the death?” Was “there struggle, fighting against the restraints, muscle exertion, [or] an actual mechanism for how this would have led to the rhabdomyolysis?”

According to Weyrauch, video showed the decedent throughout his arraignment in prison sitting calmly in a restraint chair,

___________________

2 Rhabdomyolysis typically results from severe muscle damage, and evidence of extensive muscle damage was absent in this case. The medications prescribed to the decedent can cause sedation, and in suicidal ingestions, asphyxia from drug-induced torpor or coma could also cause death.

TABLE 5-1 Causes of Rhabdomyolysis

| Hypoxic | Physical | Chemical | Biologic |

|---|---|---|---|

|

External

Carbon monoxide exposure Cyanide exposure Internal Compartment syndrome Vascular compression Immobilization Bariatric surgery Prolonged surgery Sickle cell trait Vascular thrombosis Vasculitis |

External

Crush injury Trauma Burns Electrocution Hypothermia Hyperthermia (heat stroke) Internal Prolonged and/or extreme exertion Seizures Status asthmaticus Severe agitation (delirium tremens, psychosis) Neuroleptic malignant syndrome Malignant hyperthermia |

External

Alcohol Prescription medications Over-the-counter medications Illicit drugs Internal Hypokalemia Hypophosphatemia Hypocalcemia Hypo-/hypernatremia |

External

Bacterial, viral, and parasitic myositis Organic toxins Snake venom Spider bites Insect stings (ants, bees, wasps) Internal Dermatomyositis, polymyositis Endocrinopathies Adrenal insufficiency Hypothyroidism Hyperaldosteronism Diabetic ketoacidosis Hyperosmolar state |

SOURCE: Presentation to the committee, Deland Weyrauch, Deputy Medical Examiner, Montana Medical Examiner’s Office, February 4, 2025. Table reproduced with permission of Elsevier Science & Technology Journals, from Zimmerman, J. L., and M. C. Shen. 2013. “Rhabdomyolysis.” Chest 144(3): 1058–1065, permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center.

legs dangling, shoulders relaxed, not struggling. Staff said they put him in this chair because he was very inconsistent about following directions. He . . . wouldn’t get dressed, wouldn’t walk to his arraignment, so they needed to physically move him to a place he wouldn’t voluntarily go.

Having found no reason to implicate physical restraint in the death, Weyrauch still viewed manner of death as an open question. Did the decedent knowingly and purposefully act and intend to end his life? While there was no indication of previous suicide attempts or ideation, in reviewing the emergency medical services report from the decedent’s visit to the emergency department, Weyrauch discovered that the decedent had stated to ambulance staff that he had taken “all four bottles of” haloperidol and olanzapine, thrown up twice, and that this was his “first attempt of suicide.” Medical staff documented that he was alert and fully oriented during this interaction and noted his psychiatric history but did not describe any active psychosis.

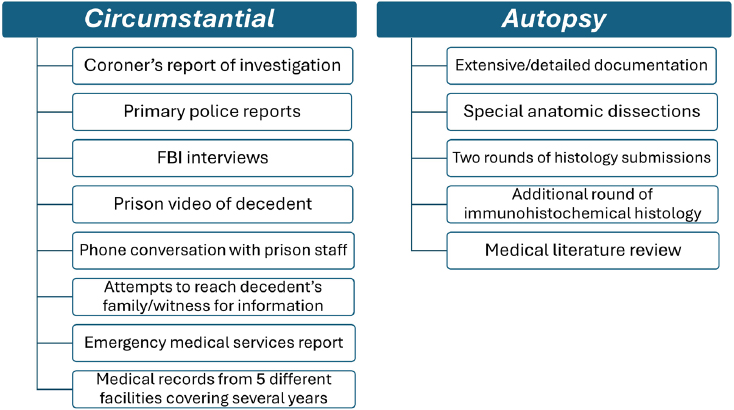

With this information in hand, Weyrauch certified the cause of death as “complications including rhabdomyolysis due to recent olanzapine, haloperidol, and methamphetamine intoxication” and manner as “suicide” with “ingested medication” as a description of how the injury occurred (given the presence of evidence that supported intentional overdose). To reach these determinations, Weyrauch had depended on an array of information (see Figure 5-1) that required substantial resources, including extensive forensic analysis; access to toxicology and pathology expertise; and coordination with a coroner, law enforcement and corrections officials, and medical personnel. What is noteworthy, beyond the extensive information that was considered for this case, was the amount of time and effort it required Weyrauch to collect and review the information.3

CASE COMPONENTS IMPACTING CAUSE- AND MANNER-OF-DEATH DETERMINATIONS

The Weyrauch case provides clear illustration of how complexity and indeterminacy affect cause- and manner-of-death determinations, the resources that may be needed to make these determinations, and challenges medical examiners and coroners may face when making such determinations. It contains many of the components that play a part in medicolegal death investigations and illustrates the challenges faced by forensic pathologists in reaching a determination of cause and manner of death. In the following sections, important components of medicolegal death investigations

___________________

3 The committee was, however, unable to obtain precise information on cost and number of hours involved.

NOTE: Some information presented in this figure would not be available in all cases (e.g., in cases without Federal Bureau of Investigation [FBI] involvement, FBI interviews would not be a source of information); the figure does not include all potential sources of information (e.g., genetic tests).

SOURCE: Presentation to the committee, Deland Weyrauch, Deputy Medical Examiner, Montana Medical Examiner’s Office, February 4, 2025.

are considered, beginning with components most evident in the case Weyrauch presented.

Access to Forensic Pathologists and Autopsy Services

As noted in Chapter 2, the shortage of board-certified forensic pathologists in the United States places limits on the ability of the MLDI system to perform investigations into cause and manner of death in every instance. The dearth of forensic pathologists means that, particularly in cases where a death occurs in a remote area (as was the case in the Weyrauch example), time, cost, and resources for transporting a body to a medical examiner or forensic pathologist’s office may determine which cases receive an autopsy.4 In Montana, a state of 1.13 million people,5 the Montana Medical Examiner’s Office, which provides autopsy services and death investigation resources for county coroners, law enforcement agencies, and county

___________________

4 Presentation to the committee, Deland Weyrauch, Deputy Medical Examiner, Montana Medical Examiner’s Office, February 4, 2025.

5 1,137,233 as of July 1, 2024 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2024b).

attorneys, has only two locations: the Montana State Crime Lab in Missoula and the Eastern Forensic Science Division in Billings. Similarly, Nebraska, which has just over 2 million residents, is served by the Douglas County morgue in Omaha, the state’s only public autopsy facility.6 For Washington state, geography complicates autopsy services for eastern counties, as all contracted forensic pathologists reside west of the Cascade Mountains.7 According to Hayley L. Thompson, coroner for Skagit County, Washington, “Currently, only one pathologist is willing to drive to the eastern side” of the state, and “this has resulted in coroner offices having to forgo an autopsy (because there’s no pathologist available) or wait several days for an autopsy to be done.”8

Collecting Information That Informs Determinations of Cause and Manner of Death

From preinvestigations conducted in advance of an autopsy through certification of cause and manner of death, a range of information from multiple sources is needed to ensure that determinations of cause and manner of death are correct. As the Weyrauch case illustrates, such information can be circumstantial (e.g., information from scene investigation, interviews, police reports, video, medical records) or obtained directly from the decedent’s body postmortem (e.g., external or internal examination of the body, analysis of laboratory test results) (see Figure 5-1). Inaccurate determinations can result from incomplete or incorrect information (e.g., due to a lack of access to information), poor communication (e.g., between medical examiners and coroners and investigative agencies, law enforcement officials, corrections officials, medicolegal death investigators, health care providers, and social service personnel), or implicit or explicit bias. Information collection may also be constrained by financial9 and other limitations.10 As in any practice of medicine, even if all of the information concerning a case is complete and correct, biased reasoning can lead to an inaccurate determination. These limitations mirror and are emblematic of errors and inaccuracies in other medical specialties (e.g., internal medicine),

___________________

6 An office performing autopsies in the central part of the state closed in 2022 and an office performing autopsies in the western part of the state closed in 2024 (presentation to the committee, Erin Linde, Forensic Pathologist, Omaha, Nebraska, February 4, 2025).

7 Contract forensic pathologists serve the coroner offices in eastern Washington, other than those serviced by the Spokane County medical examiner.

8 Presentation to the committee, Hayley L. Thompson, Skagit County Coroner, Mount Vernon, Washington, September 19, 2024.

9 Certain investigative techniques (e.g., genetic testing, genetic genealogy) are too expensive for many offices.

10 These might include time constraints, inadequate facilities, and lack of access to (or unfamiliarity with) relevant medical literature.

reflecting the reality that forensic pathology is the practice of medicine and not a strict forensic science (Graber, Franklin, and Gordon, 2005).

Medicolegal death investigators are a critical source of information for forensic pathologists, as they often rely on the information gathered by medicolegal death investigators to interpret the physical findings from the examination of the decedent’s body. Medicolegal death investigators are also important because they are usually the first to examine death scenes.11 Their information-gathering assists medical examiners and coroners by providing not only documentation of the scene of a death but also the decedent’s medical history, statements from witnesses and family members, and photographs of the body. Beyond initial scene investigation, medicolegal death investigators establish the decedent’s identity, identify and notify next of kin, manage the proper handling of the body before autopsy, assist in maintaining the chain of custody for evidence, and work to ensure that all documentation is thorough and accurate. The absence of an investigation by a medicolegal death investigator may make it more difficult to determine cause and manner of death, disadvantage those conducting autopsies and conducting prosecutions, and hinder prevention efforts.12

The National Institute of Justice publication Death Investigation: A Guide for the Scene Investigator describes medicolegal death investigators as the foundation of a medicolegal death investigation (NIJ, 2024a). The guide emphasizes the importance of their role in documenting relevant information about deaths, including at minimum the reporting agency’s information; the reporting individual’s name and call-back number; the associated law enforcement case number and/or hospital record number; the decedent’s demographics, including name, date of birth, age, race, ethnicity, and biological sex; details about suspected cause and manner of death; summary of terminal events and reported medical history; and apparent scene safety or security concerns (NIJ, 2024a, p. 2). The guide also emphasizes the importance of medicolegal death investigators in facilitating collaboration and ensuring timely notification of other parties (e.g., next of kin, law enforcement, district attorneys/prosecutors, public health officials, crime lab personnel, forensic pathologists, anthropologists, body transport services, funeral homes, emergency management, organ and tissue procurement agencies) to facilitate a coordinated response to a death (NIJ, 2024a, p. 8).

___________________

11 Examination of incident scenes may also yield critical information (e.g., in cases where an individual experienced a health emergency and was transported to a medical facility, it may be important to examine the scene where the health emergency occurred).

12 Presentation to the committee, Jan Gorniak, Forensic Pathologist, World Peace Forensic Consulting, LLC, February 4, 2025. As an example, Gorniak cited the role of a failed jack in a death to illustrate how investigations contribute to prevention efforts by reporting faulty products to the Consumer Product Safety Commission. For a discussion of how medicolegal death investigations benefit public health and safety, see Chapter 2.

In remarks to the committee, Jan Gorniak, a board-certified forensic pathologist and certified death investigator, asserted that “I can’t do my job without the hard work of the investigators. So, you talk about a shortage of forensic pathologists—there’s a shortage of death investigators also. . . . They’re the ones that are running back and forth to the scenes and getting [forensic pathologists] the information that we need.”13

In many instances, investigations are conducted by law enforcement officials for the purpose of determining whether a crime has occurred. While law enforcement may work with medicolegal death investigators, coroners, or medical examiners collaboratively to search for, collect, and package evidence, the investigatory work of law enforcement at a crime scene and beyond has implications for the investigations of medicolegal death investigators and others involved in making determinations of cause and manner of death. Information that is withheld or removed from the scene may adversely affect determinations of cause and manner of death. Incomplete information and investigations can also result from poor communication among investigative agencies, law enforcement officials, corrections officials, medicolegal death investigators, forensic pathologists, and others.14

Deaths in custody can present particular challenges for medicolegal death investigations. Carceral facilities are tightly controlled environments with policies and protocols that can limit information collection.15 Carceral staff sometimes respond to an in-custody death without the necessary training, tools, or experience to protect the body and the area where a death occurs, safeguard all evidence, and enable an effective response (Penal Reform International, 2023, p. 11).16 In addition, carceral facilities are places of high security and may be located in remote areas. Such factors may prevent investigative authorities from gaining access to all the areas and information within a facility or may delay their arrival (Penal Reform International, 2023, p. 11). Furthermore, pertinent information may be wrongly withheld if there is a risk that carceral staff or carceral conditions are implicated (McCann and Bryant, 2025).

___________________

13 Presentation to the committee, Jan Gorniak, Forensic Pathologist, World Peace Forensic Consulting, LLC, February 4, 2025.

14 Gorniak, 2025.

15 For-profit private facilities or health care providers often have policies and procedure in place that limit the exchange of information with other parties (presentation to the committee, Johnny Wu, Executive Vice President and Chief Clinical Officer, Centurion Health, February 4, 2025).

16 In her presentation to the committee, Gorniak described some of the information that should be collected in cases of suicide deaths in custody, including housing status (e.g., whether the decedent was in a single cell or “pod” [a smaller, self-contained housing unit, typically holding 8–16 individuals]) and whether the decedent was on suicide watch, was restrained (and, if restrained, the type of restraint used, how many people were involved in the restraint, and how long they were restrained), and received medical treatment (Gorniak, 2025).

Coroner liaison programs have been developed to improve death investigations by bridging some of these gaps (as well as gaps in investigator expertise) and to provide access to forensic resources. Coroner liaisons can provide support for coroner systems and medical examiner offices by improving communication between the two offices, assisting with (and being a resource for) death investigations and training, and working toward statewide consistency in death investigation procedures (NIJ, 2024b).

The coroner liaison position was devised by the state of Montana after the state identified challenges in its coroner system that included a “lack of consistency in processes, minimal training, lack of casework experience, communication issues with medical examiners, and lack of resources” (Montana Department of Justice, 2024, p. 1). According to the Montana Department of Justice, the position bridges a resource gap and provides consultation, training, and support for the state’s coroner system. Its functions include presenting coroner trainings, training coroners to use the state’s Death Investigation Database system, delivering resources related to death investigation standards that support coroner functions (e.g., by assisting and consulting on death investigations and maintaining access to medical records statewide), and collaborating with medical examiner and autopsy technicians to improve coroner documentation (e.g., by assisting in the optimal completion of investigation reports, medical records, and external reports) (Montana Department of Justice, 2024, p. 3). The coroner liaison position, which reviews between 1,200 and 1,500 cases each year, “has resulted in fewer unnecessary toxicology tests, faster medical record reviews, fingerprinting of all decedents, a decrease in ‘missed cases’ that should have included an autopsy or another investigative avenue . . . established direct contact with every coroner office,” and “improved reporting tools” (Montana Department of Justice, 2024, p. 4).

Examinations/Autopsies

Properly conducted forensic investigations are especially important in cases of deaths in custody, as the circumstances of such deaths may complicate the ability to obtain accurate determinations. Nevertheless, there are no universal standards and requirements for postmortem examinations.

As stated in Box 2-1, an autopsy is a systematic examination of a body after death that is conducted to determine cause and manner of death. Depending on the complexity of the case and what is known of the circumstances of death, it may be possible to make a determination of cause and manner of death based upon an external examination. In other cases, a thorough internal examination of a body may be necessary to identify internal conditions (e.g., disease, internal injury) through gross and microscopic analysis of tissues.

Autopsy laws vary significantly by state, with some states mandating them for certain deaths (e.g., sudden, unexpected infant deaths; deaths where foul play is suspected) and others allowing for discretion by the medical examiner or coroner (World Population Review, 2025). Several states mandate autopsies for deaths in custody. Virginia, for instance, requires autopsies for deaths of those within its Department of Corrections.17 Although autopsies are sometimes inconclusive, they are the benchmark for determining the cause of death, and they frequently reveal injuries and conditions that were not otherwise apparent (Maccio et al., 2025).

Rigorous postmortem examinations are a multistep process that involves not only physical external and internal inspections of the body but also radiologic imaging procedures, laboratory tests, and extensive histologic tissue studies. The National Association of Medical Examiners (NAME, 2020) publishes (nonbinding) forensic autopsy performance standards that outline minimum standards for external and internal examinations of the bodies of the deceased and when complete autopsies should occur.

According to NAME (2020), standards for external examinations of the body allow forensic pathologists to assess available information to

(1) direct the performance of the forensic autopsy, (2) answer specific questions unique to the circumstances of the case, (3) document evidence, the initial external appearance of the body, and its clothing and property items, and (4) correlate alterations in these items with injury patterns on the body. (p. 13)

As part of external examinations, forensic pathologists (or their representatives) measure body length and weight, examine external aspects of the body before any internal examination, and photograph the decedent. They may also document and correlate clothing findings with injuries to the body and identify and collect trace evidence on clothing.

External examinations also document identifying features, signs of or absence of disease and trauma, and signs of death. This involves describing apparent age, phenotypic sex, hair, eyes, and abnormal body habitus; documenting prominent scars, tattoos, skin lesions, amputations, and the presence or absence of dentition; inspecting and describing the head, neck, thorax, abdomen, extremities, hands, and the posterior body surface and genitals; and documenting evidence of medical or surgical intervention. When conducting external examinations, forensic pathologists are advised to describe postmortem changes including livor mortis, rigor mortis, decompositional changes, or evidence of embalming (NAME, 2020). It is

___________________

17 Va. Code Ann. § 32.1-285.

important that the forensic pathologist document injuries to assist in determining “the nature of the object used to inflict the wounds, how the injuries were incurred, and whether the injuries were a result of an accident, homicide, or suicide” (NAME, 2020, p. 15).

In internal examinations, thoracic and abdominal cavities are “examined before and after the removal of organs so as to identify signs of disease, injury, and therapy” (NAME, 2020, p. 18). NAME standards state that forensic pathologists should examine internal organs in situ, describe adhesions and abnormal fluids, document abnormal position of medical devices, and describe evidence of surgery. Forensic pathologists (or their representatives) remove, weigh, dissect, and describe internal organs from the cranial, thoracic, abdominal, and pelvic cavities. Scalp and cranial contents are examined before and after the removal of the brain. A layer-by-layer dissection is performed to properly evaluate trauma to the anterior neck. Removal and dissection of the upper airway, pharynx, and esophagus are also conducted and, in instances where occult neck injury is suspected, the posterior neck is dissected.

According to NAME (2020) standards, documentation of penetrating injuries and blunt impact injuries “should include detail sufficient to provide meaningful information to users of the forensic autopsy report, and to permit another forensic pathologist to draw independent conclusions based on the documentation” (p. 20). Foreign bodies should be recovered and documented for evidentiary purposes, and internal wound pathways should be described.

Scientific and Diagnostic Tests

As part of examinations, forensic pathologists conduct tests, which may be outsourced, to assist in making determinations of cause and manner of death. The Weyrauch example vividly demonstrates the value of such tests, as it provides a striking example of the importance of histological microscopic examination. It is important to note, however, that the costs of tests may challenge the budgets of smaller offices, especially in complex cases. Tests for a single complex case can deplete a limited budget and limit the amount of money available for routine tests. This may be an instance where small jurisdictions would benefit from access to pooled resources or centralized access to resources.

NAME (2020) standards state that X-rays should be taken to detect fractures (which may be the only physical evidence of abuse or trauma) and to detect and locate foreign bodies and projectiles. Specimens such as blood and urine must be routinely collected, labeled, and preserved to be available for needed toxicological, chemistry, or other laboratory tests. Further, “blood or other appropriate samples should be collected, whenever

possible, for potential genetic testing in sudden, unexplained deaths that remain unexplained at the completion of the autopsy” (NAME, 2020, p. 22). The standards state that forensic pathologists should “perform histological examination [microscopic analysis of tissue samples to identify structural changes and diagnose diseases] in cases having no reasonable explanation of the cause of death following gross autopsy performance, scene/circumstance evaluation, and toxicology and vitreous fluid analyses” (NAME, 2020, p. 22). Toxicology tests are performed to detect and identify substances in the body, such as licit and illicit alcohol, drugs, poisons, and heavy metals.

CHALLENGES IN MAKING DETERMINATIONS OF CAUSE AND MANNER OF DEATH

This section discusses additional challenges encountered by forensic pathologists as they seek to establish cause and manner of death. Some challenges result from overt failures (e.g., incorrect applications of scientific principles, inadequate information), while others result from faulty heuristics, a lack of familiarity with current medical knowledge, or cognitive errors that stem from biases or undue influence.

Establishing the Scientific Bases for Cause and Manner of Death

A proximate cause of death is “that which in a natural and continuous sequence, unbroken by any efficient intervening cause, produces the fatality and without which the end result would not have occurred.”18 Proximate causes of death include gunshot wounds, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, lung adenocarcinoma, acute cocaine intoxication, drowning, compression of the neck, and chronic alcohol use disorder.19 A mechanism of death describes nonspecific physiologic events that connect the proximate cause of death with the moment of death. Examples of mechanisms of death include cardiac arrhythmia (an abnormal pattern or irregularity in the heartbeat), asphyxia (a deficient supply of oxygen to the body), metabolic acidosis (a condition in which the body accumulates too much acid in the blood), hypo- or hyperkalemia (abnormally low or high levels, respectively, of potassium in the blood), and exsanguination (bleeding to death). The proximate cause of death explains why a body stopped working, whereas the mechanism of death explains how the body stopped working.

___________________

18 Presentation to the committee, James R. Gill, Chief Medical Examiner, Connecticut Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, April 2, 2024.

19 Gill, 2024.

Determinations of cause and manner of death reflect the interpretation of scientific and investigative information (e.g., medical findings, toxicology or other diagnostic tests, context, and forensic evidence). While it is possible in certain circumstances to have absolute or near absolute certainty about cause and manner of death, determinations made as to cause and manner are generally probabilistic and often framed as a likelihood (e.g., the likelihood that the determination is correct far exceeds 50 percent). While cause and manner of death are certified on death certificates by coroners and medical examiners, neither is legally binding on any party, and both can be contested. This presents challenges for courts seeking to meet the preponderance of evidence standard.

As discussed in Chapter 1, recent high-profile deaths in custody cases have drawn widespread attention to the work of forensic pathologists, medical examiners, and coroners. Serious questions have been raised about the validity of their determinations of cause and manner of death. In some cases, deaths certified as accidental or natural by one pathologist have been labeled homicides by others when, upon reexamination, mistakes, omissions, or questionable conclusions were identified. In other cases, cause of death has been attributed to a condition that may play a role in a death but has not been shown to be causal, or to a diagnosis for which the medical community has asserted that there is little or no scientific or medical basis. Questions about the scientific validity and reliability of cause- and manner-of-death determinations are not confined to death-in-custody cases.20 However, as the focus of the current report is deaths in custody, this chapter considers notable instances where scientific uncertainty and changing medical consensus have led to problematic conclusions regarding the cause and manner of in-custody deaths.

___________________

20 Shaken baby syndrome (SBS)* provides an example of how uncertain or evolving science has affected forensic death investigations. The triad of subdural hematoma, cerebral edema, and retinal hemorrhage was believed to be diagnostic of this condition, and the hypothesis formed the basis for murder prosecutions of parents and caregivers whose infants died and whose bodies bore these findings. However, considerable controversy has arisen as to whether shaking alone is the cause of death in instances when the determination is based solely on the presence of the triad of symptoms (see, e.g., Elinder et al., 2018; Narang, Fingarson, and Lukefahr, 2020; Narang et al., 2025; Sirotnak, 2006). The American Academy of Pediatrics, the Society for Pediatric Radiology, the American Association of Certified Orthoptists, the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, and the American Academy of Ophthalmology emphasize that the triad should never be used in isolation for diagnosing SBS and that medical history, an exam, and context must be considered—and other potential causes ruled out—before reaching a conclusion (Choudhary et al., 2018).

* The term SBS has been supplanted by abusive head trauma as the most comprehensive term for the intracranial and spinal lesions in abused infants and children (Choudhary et al., 2018).

Sickle Cell Trait

Sickle cell trait (SCT) is a genetic condition in which an individual inherits one normal hemoglobin gene (HbA) and one sickle hemoglobin gene (HbS) from their parents. It is markedly more common in individuals of African or Mediterranean ancestry than those of other ancestries. Unlike sickle cell disease, which occurs when an individual inherits two copies of the sickle hemoglobin gene, SCT does not cause severe health complications. Except in rare circumstances, it is a silent condition and is not considered a disease.

Medical experts assert that SCT will not, by itself, cause a fatal outcome. Attributing deaths to SCT, these experts explain, may divert attention from other contributing factors, including inappropriate restraint techniques or misconduct (Mack, Bercovitz, and Lust, 2021).

Despite a lack of scientific evidence supporting SCT as an independent cause of death, medical examiners and others have attributed deaths in custody to complications from SCT. According to an investigation by The New York Times published in 2021, since the late 1990s, SCT has been cited as a contributing factor by medical examiners, law enforcement, and police defenders in at least 46 in-custody deaths of Black individuals (LaForgia and Valentino-DeVries, 2021). In approximately two-thirds of these cases, the deceased had been subjected to forceful restraint, pepper spray, or stun gun shocks.

In 2025, the American Society of Hematology (ASH, 2025) issued a position paper based upon the findings of an expert panel consisting of hematologists, forensic pathologists, and research methodologists; the paper concluded “that any listing on the death certificate of either sickle cell crisis or sickle trait contributing to death is erroneous and must be re-examined for the underlying cause of death.”

ASH (2025) also noted that, among individuals with SCT, rhabdomyolysis

can occur for at least two reasons and may occur in individuals with or without sickle cell trait. The first is exertion-related rhabdomyolysis. Exertion-related rhabdomyolysis in those with sickle cell trait with or without death has been documented in extreme circumstances, including high-intensity military training and elite college-level football training, commonly in combination with severe environmental conditions, including extreme heat and dehydration. The second cause of rhabdomyolysis is trauma or crush injury, which may occur in individuals with sickle cell trait and cause death. Trauma-related rhabdomyolysis may be temporally associated with death in an individual with the sickle cell trait, but the

sickle cell trait is not the cause of death; the cause of death is the muscle injury leading to rhabdomyolysis and the sequelae.

It is important to note that sickled red blood cells found in tissues through histological microscopic examination do not mean that a decedent was experiencing a sickle cell crisis; the cells should not, therefore, be taken as evidence of sickling in vivo. Such cells are most likely to be postmortem artifacts.

Excited Delirium

Excited delirium is a term used by some medical examiners and others to describe extreme agitation accompanied by delirium. It has no agreed-upon definition but has frequently been cited as a cause of death in instances where individuals have died during or after police restraint. Critics argue that, like SCT, “excited delirium” has been employed to absolve law enforcement officers from responsibility in cases where excessive force or restraint may have contributed to a detainee’s death (Obasogie, 2021).

The term is believed to have been introduced in the 1980s by David Fishbain, director of psychiatric emergency services at the University of Miami, and Charles Wetli, a forensic pathologist. The condition was associated with extreme agitation, unexpected strength, and hyperthermia, particularly in individuals intoxicated with cocaine. Though never recognized as a formal medical diagnosis, it gained traction among some medical examiners and law enforcement. A small group of authors, many with ties to TASER International (now Axon Enterprise), a company that manufactures conducted energy devices used by law enforcement officers to momentarily incapacitate individuals by delivering an intense electric shock, helped popularize the term excited delirium by publishing articles on it in medical literature. In 2007, TASER/Axon distributed free copies of Excited Delirium Syndrome, a book by Vincent and Theresa Di Maio, which expanded on Charles Wetli’s concept and further promoted the term at medical and law enforcement conferences. By 2014, Di Maio admitted that he and his wife had “come up with” the term, which has since been widely used to explain deaths in police custody involving restraint, substance use, or mental illness (da Silva Bhatia, 2022).

In its 2017 position paper on recommendations for the investigation and reporting of deaths in police custody, NAME referenced “excited delirium,” noting “the more difficult cases are those where the individual is observed to be acting erratically due to a severe mental illness and/or acute

drug intoxication. These cases have been defined in the literature as excited delirium and often result in a law enforcement response and restraint of the decedent” (da Silva Bhatia, 2022, p. 1595).

The symptoms attributed to excited delirium are vague and open to interpretation. An Austin-American Statesman investigation examining nonshooting deaths in Texas police custody from 2005 to 2017 found that over one in six of the 289 cases were attributed to “excited delirium” (Dexheimer and Schwartz, 2018). A Florida Today report from January 2020 revealed that of the 85 deaths labeled as excited delirium by Florida medical examiners since 2010, at least 62 percent involved law enforcement use of force; 94 percent of those cases involved men, and in 36, the decedents were Black (Sassoon, 2019). A 2018 systematic review found that in addition to agitation, signs and symptoms of excited delirium include bizarre behavior, hypervigilance, fear, unusual strength, lack of tiring, insensitivity to pain, elevated temperature, and noncompliance with police commands. Importantly, these symptoms do not align with the clinical definition of delirium as established in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, a widely used manual for diagnosing and classifying mental disorders, which requires disturbances in attention and cognition (Gonin et al., 2018). Using information from news articles and publicly accessible databases on police killings, one study found that of 166 excited delirium–labeled deaths in police custody from 2010 to 2020, 43.3 percent involved Black individuals (Obasogie, 2021, pp. 1595–1596).21

The term continues to be used even though major health organizations, including the American Medical Association (AMA, 2021) and the World Health Organization, do not recognize excited delirium as a legitimate medical diagnosis. In recent years, multiple organizations, including NAME and the American College of Emergency Physicians, have formally withdrawn

___________________

21 White individuals, at 53 cases, made up 31.9 percent of the deaths, and

[o]f the 166 cases in which the race of the victim is available, [at 72 cases,] Black people make up almost half (43.3%) of the instances in which excited delirium is used to describe why a person died in police custody. When combined, Black and Latinx people constitute at least 56% of the deaths in custody in this sample attributed to excited delirium. This disparity reflects the disproportionate contact that police have with racial minorities as well as the persistent ways that race has framed excited delirium conversations since Charles Wetli and David Fishbain brought the concept into legal and forensic discourses. It is clear that racial minorities are in general more likely to be killed by police, and this initial data suggest that they may also be more likely to have their deaths attributed to what is perceived to be a psychiatric condition. (Obasogie, 2021, pp. 1595–1596)

support for excited delirium as a legitimate diagnosis.22 The AMA (2021) stated that current evidence does not support excited delirium as an official diagnosis and opposes its use until clear diagnostic criteria are established. Three states—California, Colorado, and Minnesota—have banned the use of the term in contexts such as death certificates, MLDI reports, and police training. However, excited delirium instruction remains part of the curriculum of police training in many areas (Lartey, 2024).

Restraint Asphyxia

Asphyxia may be caused by environmental factors (e.g., an irrespirable atmosphere), external or internal airway obstructions, neck or chest compression, or position (e.g., an inverted posture). External causes of asphyxia are diagnosed based on signs supportive of an asphyxial mechanism (e.g., petechiae, neck bruising, fractures) and physical evidence such as the presence of ligature around the neck.23 Diagnoses of asphyxia require that forensic pathologists correctly exclude other causes of death.

Several high-profile arrest-related deaths have occurred during interactions with law enforcement that involved forceful restraint, ultimately resulting in detainees becoming unresponsive or dying.24 These deaths have been attributed to restraint asphyxia, which occurs when physical restraint techniques impede normal breathing (Graham, 2025). Positioning an individual’s body in a way that obstructs airway or respiratory movements, such as being placed face down (prone) with weight applied to the back, hampers chest expansion and diaphragmatic movement (OJP, 1995). Excessive physical exertion, especially when combined with restraint, can lead to a buildup of lactic acid in the blood that results in metabolic acidosis. This condition requires increased ventilation to expel carbon dioxide, but

___________________

22 Presentation to the committee, Altaf Saadi, Assistant Professor of Neurology, Harvard University, December 3, 2024.

NAME’s (2023) position statement on excited delirium states, “These terms are not endorsed by NAME or recognized in renewed classifications of the WHO, ICD-10, and DSM-V. Instead, NAME endorses that the underlying cause, natural or unnatural (to include trauma), for the delirious state be determined (if possible) and used for death certification” (p. 1). Similarly, a report by a task force of the ACEP (2021) states, “Excited delirium syndrome is not a currently recognized medical or psychiatric diagnosis in either the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) of the American Psychiatric Association, or the International Classification of Diseases (ICD10) of the World Health Organization” (p. 11). An ACEP (2023) position statement states that the organization “does not recognize the use of the term ‘excited delirium’ and its use in clinical settings.”

23 Gill, 2024.

24 See, e.g., Eric Garner, George Floyd, and Elijah McClain.

George Floyd had no neck injury, internal injury, or petechiae. Based on the autopsy alone, without considering nonmedical information, his death can be explained by a combination of heart disease and/or a drug intoxication (Gill, 2024).

certain restraint positions impede breathing, exacerbating acidosis, which increases the risk of cardiac arrest (Weedn, Steinberg, and Speth, 2022).25,26

A 2017 NAME position paper found that manner of death in instances of restraint

can often be inconsistent from pathologist to pathologist and from office to office. . . . Manners of death in these cases have included accident due to the emphasis placed on drug toxicity, homicide due to the influence of the restraint and/or altercation, or undetermined due to the inability of the certifying physician to establish a definitive opinion. (Mitchell et al., 2017, p. 614)

Cognitive Bias

Those making cause- and manner-of-death determinations examine data and make interpretations, which means that investigatory evidence is mediated by human and cognitive factors (Dror, 2018). In some cases, contextual information aids examiners in making accurate determinations, but some contextual information can lead to cognitive bias—“unconscious and systematic errors in thinking that occur when people process and interpret information in their surroundings and influence their decisions and judgments” (Da Silva, Gupta, and Monzani, 2023, p. 1).

Bias is not inherently negative or intentional. Rather, bias affects all individuals, with observer effects “rooted in the universal human tendency to interpret data in a manner consistent with one’s expectations” (Krane et al., 2008, p. 1006). Humans are particularly susceptible to cognitive bias when there are insufficient data or when there are constraints that prevent comprehensive analysis. Even with high-quality data, time limitations or uncertainty about the relevance of information can lead to biased conclusions (Croskerry, Singhal, and Mamede, 2013). In addition, “actions that allow relatively high discretion are most likely to be subject to bias-driven errors” (Glaser, 2024, p. 151).27

In forensic science, as in medicine, bias reduces consistency, leading different experts—or even the same expert at different times—to reach

___________________

25 Presentation to the committee, Victor Weedn, Deputy Medical Examiner, Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Washington, DC, December 3, 2024.

26 “Considerations for both the cause and the manner of death might have been different,” Weyrauch said of his case study, “if the video had indicated a fight with the restraint chair or use of force by staff, or if there was no video made available by the facility to review.”

27 An examination of cases across different policing domains, for instance, revealed that “when discretion is constrained in stop-and-search decisions, the impact of racial bias on searches markedly declines” (Glaser, 2024, p. 151).

different conclusions. This inconsistency is problematic, as it undermines the public’s confidence in the conclusions (Lidén, Thiblin, and Dror, 2023).28

In the absence of training on—or an understanding of—how cognitive bias affects decision-making, forensic pathologists and others conducting death investigations may not appreciate different sources of bias, how bias can impact forensic pathology, or how to mitigate bias.29

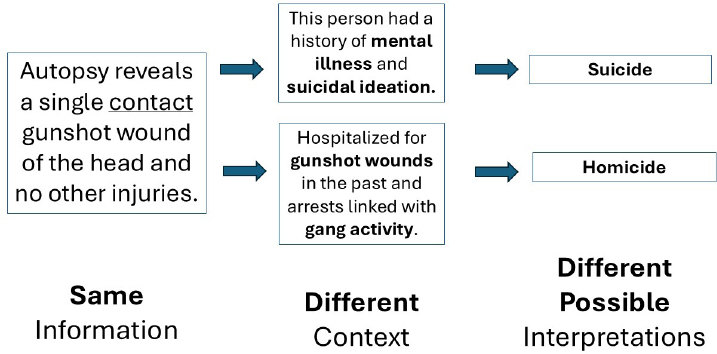

Determinations of manner of death may be affected by knowledge that a death has occurred in custody—knowledge, for example, that law enforcement or corrections officers were present at the place of death may affect the decision on whether to label a death a homicide or undetermined. Knowledge that one may be called to testify as to manner of death in a legal proceeding may lead to bias. Further, knowledge of a decedent’s history may also lead to different conclusions30 (see Figure 5-2).

Linear sequential unmasking (LSU) is an approach to mitigating cognitive bias that controls how and when forensic examiners receive case information.31 The central tenet is that analysts should first evaluate the most objective and relevant evidence—such as physical or biological evidence—before being exposed to potentially biasing contextual information, such as a suspect’s criminal history or eyewitness accounts. By delaying access to potentially biasing information, LSU offers a method by which forensic analysts might reach more independent and evidence-driven conclusions.

An expansion of LSU called LSU–expanded, offers “an approach that is applicable to all forensic decisions rather than being limited to a particular type of decision” (Dror and Kukucka, 2021, p. 1). The method encourages examiners to document their decision-making process in a worksheet to optimize information sequencing and promote transparency in decision-making (Dror and Kukucka, 2021). Taking detailed, time-stamped notes during investigations is crucial, as it preserves decision-making context and mitigates memory-based inaccuracies. Such documentation protects examiners and laboratories by providing clear records of their procedures, which can be useful for testimony or audits and in encouraging the incorporation of effective, standardized protocols into workflows (Dror and Kukucka,

___________________

28 Presentation to the committee, Adele Quigley-McBride, Assistant Professor, Simon Fraser University, September 19, 2024.

29 Presentation to the committee, Itiel E. Dror, Senior Cognitive Neuroscience Researcher, University College London, September 19, 2024. See also Dror and Kukucka (2021) and Dror and Hampikian (2011).

30 Together with physical examinations and medical tests, knowledge of the decedent’s history provides critical information to medicolegal death investigators much as medical history may provide critical information in clinical medicine. Of course, if contextual information is biasing or fragmentary (or if it is used or assessed incorrectly), an erroneous conclusion may be reached.

31 It remains an open question as to who is in the best position to determine what information is released and when.

SOURCE: Adapted from Adele Quigley-McBride, Assistant Professor, Simon Fraser University, presentation to the committee, September 19, 2024.

2021). In addition, detailed, standardized documentation encourages careful decision-making and makes it less likely that steps will be missed. It also preserves the context in which decisions were made and documents the sequence in which an examiner learned information and why an examiner came to a decision.32

To mitigate bias, researchers have suggested avoiding, as much as possible, context that is not needed. Instead, they recommend mandatory reporting of provided contextual information and using bias mitigating techniques, such as constructing plausible alternative hypotheses, before settling on the most likely (Lidén, Thiblin, and Dror, 2023). Many other approaches to avoiding cognitive bias have been suggested, including more frequent use of second opinions and effective peer review processes, as well as exploiting decision-support resources, including artificial intelligence tools used in medical diagnosis (Croskerry, Singhal, and Mamede, 2013). It is worth noting that it is often easier to detect bias than to prevent it, and that second reviews are particularly useful for bias detection.

Undue Influence

It is critical that medical examiner and coroner offices operate without undue influence from those with a stake in an investigation. In the context of deaths in custody, these offices may face pressure from, among others, law enforcement and corrections officers, attorneys, families of decedents,

___________________

32 Quigley-McBride, 2024.

reform advocates, government officials, professional colleagues, academicians, and members of the press and the public.33 Proximity to law enforcement can exert particular influence on medicolegal death investigations; it is important to understand relationships between medicolegal death investigators and forensic laboratories, law enforcement, prosecutors, and others when considering possible sources of influence.

A 2013 NAME position paper on medical examiner, coroner, and forensic pathologist independence states that medicolegal death investigators “must investigate cooperatively with, but independent from, law enforcement and prosecutors.34 The parallel investigation promotes neutral and objective medical assessment of the cause and manner of death” (Melinek et al., 2013).

In testimony to the committee, medical examiners and coroners emphasized the importance of independence. Reade A. Quinton, president of NAME, suggested that the best structure for a medical examiner office is an office that is independent of any other agency: “As soon as you get to a point where you have the medical examiner with oversight by, for instance law enforcement or something like it, that’s when obviously you could run into potential problems.” Medical examiners stress that idea—“and I have to do it in court all the time—that ‘I do not work for the sheriff’s office [and] I do not work for the DA’s office.’”35 Coroner Hayley L. Thompson, in testimony to the committee, emphasized that “investigations can be influenced by pressures that police and other government officials exert on coroners.” “To properly understand deaths in custody,” she said, “there needs to be continuity across the nation in how these deaths are reported, investigated, and ultimately certified.”36

There are, however, jurisdictions where law enforcement officers perform the duties of the coroner (see Chapter 2). Further, in jurisdictions where the position of coroner is an elected position, coroners may face political pressure from constituents to make certain determinations. Similarly, in jurisdictions where funeral directors perform the role of coroner,

___________________

33 Gill, 2024.

34 The 2009 National Research Council report on forensic science endorsed this separation, stating, “Scientific and medical assessment conducted in forensic investigations should be independent of law enforcement efforts either to prosecute criminal suspects or even to determine whether a criminal act has indeed been committed” (NRC, 2009, p. 23).

Surveys of NAME members found that over 70 percent of respondents “had been subjected to pressures to influence their findings, and many had suffered negative consequences for resisting those influences”; in a separate study, over 30 percent of respondents “indicated that fear of litigation affected their diagnostic decision-making” (Melinek et al., 2013, p. 93).

35 Presentation to the committee, Reade A. Quinton, Associate Professor of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Mayo Clinic, and President, NAME, February 4, 2025.

36 Presentation to the committee, Hayley L. Thompson, Skagit County Coroner, Mount Vernon, Washington, September 19, 2024.

a desire to align with the interests of the familial clients of decedents may influence the outcome of an investigation (e.g., hesitancy to list suicide or drug overdose as manner of death on a death certificate either to prevent embarrassment or because the cause or manner of death could influence awarding of death benefits to the family).37

QUALITY ASSURANCE AND ACCOUNTABILITY

How often do forensic pathologists get cause and manner wrong? That is a difficult question to answer, as there are instances where it may not be possible to establish ground truth. Determinations of cause and manner of death represent informed expert opinion. As such, depending upon the information considered, different forensic pathologists can reach different conclusions about the same case. While not required as standard practice, mechanisms are nonetheless available to evaluate investigatory rigor and increase the likelihood that determinations of cause and manner of death are correct.

Peer Review

In recent years, forensic pathologists around the world have worked to incorporate peer review into professional practices. Peer review is a process wherein experts from a specific field or discipline evaluate the quality of their peers’ work to assess validity and quality. The goal of peer review is to improve individual or system performance. It is widely used in the medical and scientific communities to identify and correct errors, and it serves as an important vehicle for education. It is important to note, however, that the quality and meaningfulness of peer review is highly dependent on transparency and the protocol employed.

In the United States, some medical examiner offices hold regular meetings to review case conclusions before they are finalized (prospective review) or after the fact (retrospective review).38 Prospective peer review serves as a preventive measure, as it can identify errors prior to the issuance of a final report. In contrast, retrospective peer review serves as an auditing tool that evaluates whether forensic pathologists have adhered to standards of practice. Peer review can be performed by an individual or a group and may be unblinded or blinded. In unblinded reviews, reviewers have access to all contextual information. Blinded reviews, on the other hand, remove contextual information in an effort to minimize cognitive bias.

___________________

37 Presentation to the committee, Cilina Evans, Coroner, Shelby County, Alabama, September 19, 2024.

38 Such reviews are common for infant or child deaths and deaths in custody.

Peer Review by the Ontario Forensic Pathology Service

At the February 2025 meeting of the committee, Alfredo E. Walker, forensic pathologist and coroner, Eastern Ontario Regional Forensic Pathology Unit, described the peer review program of the Ontario Forensic Pathology Service in Canada, which is, geographically, the largest single MLDI system in the world. The program provides individual reviews of cases of homicides and criminally suspicious deaths, as well as routine cases of noncriminally suspicious deaths. It also provides committee reviews of complex cases and child injury cases. Materials reviewed include final postmortem examination reports, summaries of circumstances of death, summaries of scene examination findings/scene photographs, postmortem examination photographs, routine histology slides, results of ancillary investigations (e.g., biochemistry, toxicology, microbiology), and specialist pathology consultation reports.

In the Ontario Forensic Pathology Service, Walker explained, reviews by a complex case expert committee (CCEC) are mandatory in cases of deaths in custody where a physical altercation between the decedent and correctional staff occurred; deaths where force was used by law enforcement officers; and deaths while detained and physically restrained in a psychiatric facility, hospital, or secure treatment program. CCEC reviews are also mandatory in cases where there is persistent disagreement during peer review based on a perceived error or a difference of opinion between the forensic pathologist who conducted the initial investigation and the forensic pathologist who reviewed the case.39

At CCEC meetings, the originating forensic pathologist presents the case and engages in Q&A. This is followed by roundtable discussion that canvasses the opinions of each panelist, provides an opportunity to discuss the opinions of the panel chair, and considers recommendations for further case workup or analysis. Consensus or majority opinions are documented.40

Peer Review at Forensic Science SA (South Australia)

Forensic Science SA operates within the Attorney General’s Department of the Government of South Australia. Peer review of cases is conducted on both a formal and informal basis at the South Australian state forensic facility, the facility where all medicolegal autopsies from the state of South Australia are carried out.

___________________

39 Presentation to the committee, Alfredo E. Walker, Forensic Pathologist and Coroner, Ontario Forensic Pathology Service, February 4, 2025.

40 Walker, 2025.

From April 1, 2021, to March 31, 2022, the latest period for which data are publicly available, the CCEC reviewed 21 cases (Ontario Forensic Pathology Service, 2022).

Informal peer review happens daily as pathologists working in proximity discuss findings. Formal reviews involve meetings where “the clinical details of each case, the autopsy findings, the proposed ancillary testing and the conclusions/diagnosis” are presented. “The meeting and those who have attended is recorded in the case file, and the agreed upon provisional cause of death, in addition to associated details such as proposed tests and retained specimens (e.g., tissues for histology or blood for toxicology), are then forwarded to the State Coroner’s office” (Sims, Langlois, and Byard, 2013).

Special cases, such as homicides or pediatric deaths, undergo additional scrutiny, including reviews by specialized pathologists. Before releasing final conclusions, an “exit review” may be conducted if changes to the cause of death are necessary. Once reports are complete, certain categories (e.g., deaths in custody, homicides, pediatric deaths) undergo a formal “technical review” by a second pathologist. If disagreements arise, they are documented. Ultimately, because of peer review, “the number of cases requiring supplementary or reissued reports for errors has declined [and] greater uniformity in approach has been achieved.” Further, “time spent on such rigorous reviews may be far less than is incurred in dealing with errors or complex issues that are only identified after reports have been released” (Sims, Langlois, and Byard, 2013).41

In-Custody Mortality Review Panels

Some jurisdictions in the United States support and promote in-custody mortality review panels that conduct internal reviews of deaths occurring in custody. These panels aim to identify potential causes of death, assess the adequacy of care and safety protocols, and make recommendations for preventing similar deaths in the future. They often involve a multidisciplinary team that includes medical professionals, mental health experts, and security staff.

In her February 4, 2025, presentation to the committee, Michelle Jorden, chief medical examiner, Santa Clara County, California, and current vice president of NAME, emphasized the importance of assembling all agencies involved with the decedent to conduct a rigorous system evaluation. Successful evaluations depend on strict confidentiality guidelines that allow the partners to come to the table and freely discuss a particular case.42

___________________

41 In correspondence dated May 1, 2025, Andrew Camilleri, Assistant Director, Science & Support, Forensic Science SA, indicated that the procedure reported in Sims, Langlois, and Byard (2013) “remains broadly aligned with FSSA’s current peer review process, although there have been some changes […that] have not been described in the literature.”

42 Presentation to the committee, Michelle Jorden, Chief Medical Examiner, Santa Clara County, California, and Vice President, NAME, February 4, 2025.

In-custody mortality review panels often generate reports with specific recommendations for policy changes, improved training, enhanced safety protocols, and better access to health care and mental health services. Their reviews are crucial for improving the safety and well-being of individuals in custody, as well as for ensuring accountability and transparency in correctional facilities.

Second and Extrajurisdictional Autopsies

Where cause of death is disputed, a second autopsy may be performed. Second autopsies present technical and interpretive difficulties due to the adulterated state of the body “and usually rely heavily on investigative information, first autopsy findings, and additional documentation from the first autopsy” (Aiken and Nashelsky, 2023, p. 7).

A NAME position paper on second autopsies recommends that they be performed in compliance with NAME’s forensic autopsy standards:

The second autopsy pathologist should generate a complete autopsy report that includes external and internal examination observations, limitations of the examination, final diagnoses, opinions, and cause and manner of death, unless sufficient information is not available for a cause- and manner-of-death determination. A second autopsy report should fully describe the condition of the body as received (externally and internally) and note organs that are not present in the body. Lastly, a second autopsy report should include a list of all items requested from the first autopsy jurisdiction (e.g., investigative reports and photographs) and what was provided. (Aiken and Nashelsky, 2023, p. 4)

NAME suggests that “second autopsies are not necessarily scientifically neutral or devoid of biases as parties may have vested interests in particular autopsy findings” (Aiken and Nashelsky, 2023, p. 3). Nevertheless, second autopsies have uncovered serious errors.

The Autopsy Initiative was established in 2022 to provide second autopsies free of charge for families who have lost loved ones to an in-custody death. As of February 2025, the initiative had conducted 104 autopsies and completed reviews of 20 cases. In each of the completed cases, the second autopsy resulted in a different cause of death determination; 12 cases had what the initiative describes as “a discrepancy, inaccuracy, or suspicious circumstance present,” and some of the discrepancies were significant. In one case, the pathologist conducting the initial autopsy listed cause of death as dehydration/bronchopneumonia, while the second pathologist ruled that the death was caused by asphyxia by manual strangulation.43 In another

___________________

43 Manual strangulation can be difficult to diagnose and is subject to misdiagnosis.

case, a bullet was found in the body of an autopsied individual.44 In three other cases, decedents’ families were told that an autopsy had been performed when it had not.45

In instances where a case is highly sensitive for a jurisdiction, autopsies may be conducted in other jurisdictions to avoid any appearance of bias.

Audits

Several states have mechanisms for audits of the results of death-in-custody investigations.

In testimony to the committee, James R. Gill, Connecticut Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, referred to audits of in-custody deaths by the State of Connecticut.46 Connecticut’s Office of the Inspector General issues investigative reports on the use of force by police officers, including incidents that did not result in death (Division of Criminal Justice, 2025). State law provides that “[w]henever a peace officer, in the performance of such officer’s duties, uses physical force upon another person and such person dies as a result thereof or uses deadly force . . . upon another person, the Division of Criminal Justice shall cause an investigation to be made and shall have the responsibility of determining whether the use of physical force by the peace officer was appropriate.”47 The law also requires that the investigation into any death resulting from the use of force by a police officer be conducted by a state’s attorney from a judicial district other than where the incident occurred.

In New York State, the Attorney General’s Office of Special Investigation (OSI) “investigates deaths caused by police officers or peace officers, including corrections officers. If an investigation shows that a crime was committed, evidence is presented to a grand jury, and if the grand jury returns an indictment, OSI prosecutes the case.” If the “investigation shows that an officer caused a death, but that a crime cannot be proved beyond a reasonable doubt, OSI publishes a report on” its “website detailing the facts disclosed by the investigation and explaining why the evidence would not demonstrate proof beyond a reasonable doubt” (Office of the New York State Attorney General, 2025).

The Washington State Legislature created the Office of Independent Investigations (OII, n.d.) in 2021 “to conduct thorough, transparent, and

___________________

44 Presentation to the committee, Nicole Martin, Legal Program Director, The Autopsy Initiative, February 4, 2025.

In subsequent correspondence, Martin clarified that the bullet was related to the terminal event (and was not, for example, a residual bullet from an earlier incident).

46 Gill, 2024.

47 CT Gen Stat § 51-277a. (2024).

unbiased investigations of cases that involve police use of deadly force.” The formation of the agency was recommended by the Governor’s Task Force on Independent Investigations of Police Use of Force (Washington Office of the Governor, 2020). An 11-member advisory board, which includes family affected by incidents of police use of deadly force, law enforcement, community members, a representative of a federally recognized Washington tribe, a mental health professional, a prosecutor, a defense attorney, and a member of the Criminal Justice Training Commission, was established to work with OII and advise on policies and procedures. The OII (n.d.) began actively investigating deaths in December 2024.

As described in Chapter 2 in Box 2-5, at the murder trial of Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin, David Fowler, former chief medical examiner for the state of Maryland, testified that, in his opinion, George Floyd’s death was caused by a combination of factors, including preexisting heart conditions and drug use, rather than asphyxiation due to Chauvin’s restraint. Following Chauvin’s conviction, more than 450 medical experts signed a letter to the Maryland Attorney General condemning Fowler’s “cause of death opinion, particularly the portion that suggested open-air carbon monoxide exposure as contributory [and said that it] was baseless, revealed obvious bias, and raised malpractice concerns” (Frosh et al., 2021, p.1). They demanded an independent review of all deaths in custody during Fowler’s tenure as chief of the Maryland Office of the Chief Medical Examiner (OCME) (Frosh et al., 2021, p. 2).

In September 2021, Maryland’s Office of the Attorney General appointed an audit design team to design an audit “to assess whether OCME had inappropriately classified deaths that occurred during or soon after restraint, as well as whether OCME’s determinations showed patterns consistent with racial and/or pro-police bias” (Kukucka et al., 2025, p. 9).

Kukucka and colleagues (2025) identified more than 1,300 OCME death-in-custody cases from 2003 through 2019; 87 cases were included in the audit, each involving an unexpected death during or soon after restraint. Extraneous or potentially biasing information was removed from the case files. From September through December 2024, an international group of 12 forensic pathologists reviewed the 87 cases48 and independently opined on the cause and manner of death.49 This audit found the following:

- Case reviewers’ consensus manner-of-death opinion differed from OCME’s manner determination for more than half (44) of the 87 audit cases, including 36 cases that case reviewers unanimously

___________________

48 Each case was reviewed by three pathologists.

49 Five of the reviewers practice outside of the United States, where opinions on manner of death are not proffered.

- deemed homicides but which OCME had ruled as either undetermined (29 cases), accidental (5 cases), or natural (2 cases).

- Whereas case reviewers judged 48 of the 87 deaths as homicides, OCME ruled only 12 of those same deaths as homicides.

- OCME ruled deaths as homicides even less often if the decedent was Black (rather than White) or was restrained by police (rather than by others).

- In nearly half (42) of the 87 audit cases, OCME’s cause-of-death statement referenced “excited” or “agitated” delirium, which has been widely rejected as a valid cause of death. In those cases, OCME almost always certified the manner of death as “undetermined” (93 percent), with only one case (2 percent) ruled a homicide. In contrast, case reviewers deemed 25 of those same 42 deaths (56 percent) to be homicides.

- For 47 percent of cases, at least one case reviewer judged OCME’s cause-of-death determination to be “not reasonable.” For 66 percent of cases, at least one case reviewer judged OCME’s manner-of-death determination to be “not reasonable” (Kukucka et al., 2025, p. 9).

In addition, Kukucka and colleagues (2025) stated that

case reviewers often noted that OCME’s autopsy reports (a) failed to acknowledge restraint as a potential contributing factor when appropriate, (b) correctly acknowledged restraint as a contributing factor but did not certify the death as a homicide (thus violating the “but-for” standard that requires deaths resulting from another person’s actions, regardless of intent, to be certified as homicides), and/or (c) did not provide adequate justification for their determinations. (p. 9)

With regard to the quality of OCME’s investigations, “case reviewers frequently commented that key details about the nature and/or duration of restraint were lacking, such that video (e.g., body-worn camera) footage and/or more reliable first-hand accounts of the restraint would have been helpful” (Kukucka et al., 2025, p. 10).

While case reviewers praised “OCME’s regular use of consultation services (e.g., cardiac pathology, neuropathology),” they noted “routine deficiencies in OCME’s post-mortem examinations, including the number, content, and quality of autopsy photographs” (Kukucka et al., 2025, p. 10). Case reviewers “suggested that law enforcement should be better educated on the dangers of improper restraint and trained in non-lethal restraint techniques, and that crisis response teams should include not only law enforcement but also professionals who specialize in mental health and/or de-escalation” (Kukucka et al., 2025, p. 10).

It is particularly concerning that in over half of the audited OCME autopsies, the reviewers reached manner-of-death determinations different from the original determination. These results are not necessarily representative of the reproducibility rate for manner-of-death determinations in restraint-related deaths, given that the OCME audit is the only audit of this type (and that it was motivated by biased testimony). Nevertheless, the findings raise serious concerns about the reproducibility and accuracy of manner-of-death determinations and highlight a need for rigorous studies of the subject. Such studies could provide valuable information about points of failure in the MLDI system and where improvements might be made.

“Prevention of Future Deaths” Reports

In the United Kingdom, the duty to make a report to prevent future deaths was introduced in the Coroners50 and Justice Act 2009.51 These reports, known as prevention of future deaths reports (PFDs), PFD reports, or Regulation 28 reports (after the section of the Act that details the required process), had previously been discretionary but with the passage of the Act became a statutory requirement. Reports are not restricted to matters causative of the death in question. Further, a PFD is a recommendation that action should be taken, not what that action should be.52