Strengthening the U.S. Medicolegal Death Investigation System: Lessons from Deaths in Custody (2025)

Chapter: 3 Data on Deaths and Deaths in Custody

3

Data on Deaths and Deaths in Custody

Incomplete or inaccurate data on the cause and circumstances of a death hinder both the ability of public health officials to generate findings that positively affect population health and the ability of the justice system to hold responsible the perpetrators of unnatural deaths. Absent accurate data that provide a comprehensive picture of the landscape of deaths in custody, the nation’s ability to address systemic issues and reduce deaths in custody is limited, which compromises the ability to improve public health and the practice of forensic medicine or serve the interests of criminal justice.

Medicolegal death investigation (MLDI) systems play a critical role in data collection and are important users and evaluators of these data. This chapter describes efforts to collect data on deaths and particularly deaths in custody, obstacles to collecting these data, and currently available data.

COLLECTING DEATH DATA

A death certificate is the single most important source of information on cause and manner of death. Death certificates provide legal and administrative documentation and vital statistics for epidemiologic and health policy purposes. To “satisfy these functions, it is important that death certificates be filled out completely, accurately, and promptly” (Brooks and Reed, 2015, p. 74).

“Despite the importance of accurate death certification, errors are common. Studies at various academic institutions have found errors in cause and/or manner of death certification to occur in approximately 33% to 41% of cases” (Brooks and Reed, 2015, p. 74). The content and structure

of death certificates vary by state, but most follow the structure of the U.S. Standard Certificate of Death (see Figure 3-1; Brooks and Reed, 2015), which includes “demographics/statistics (e.g., name, social security number, race, occupation), method/place of bodily disposition (e.g., funeral home, burial vs. cremation, cemetery site), and death information (e.g., date and time, cause, manner)” (Brooks and Reed, 2015, pp. 74–75).

Death certificates are filed with the vital records office of the state where the death occurred. The state then sends the death certificate to the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). NCHS’s National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) aggregates these data to provide the most complete data on births and deaths in the United States (Data Foundation, 2024).1 NVSS does not, however, provide data on in-custody deaths, in part because there is no mechanism for routine collection of this information. There is, for instance, no universal requirement that the fact that a death occurred in custody be reported on death certificates.

CDC’s National Violent Death Reporting System collects data on violent deaths, including homicides, suicides, and deaths where individuals are killed by law enforcement acting in the line of duty. This information is collected from death certificates, coroner/medical examiner reports, and law enforcement reports and entered into an anonymous database. Collected data elements provide valuable information about violent deaths, but they do not provide an indication of whether a death occurred while a decedent was in custody. Nevertheless, there have been important efforts to collect death-in-custody data.

THE DEATHS IN CUSTODY REPORTING ACTS OF 2000 AND 2013

In the United States, the most significant actions taken to collect death-in-custody data were passage of the federal Death in Custody Reporting

___________________

1 There are ongoing efforts to modernize vital records systems by moving from paper-based processes to electronic records and adopting common tools and standards for data. Unfortunately, the current vital records system is “a patchwork of 57 separate state and local vital records offices . . . with locally-determined priorities” and varying levels of sophistication and resources. This heterogeneity is driven in part by “the inherently intergovernmental nature of the U.S. vital records systems [that] introduces complexities and inconsistencies among jurisdictions” and “limited and inconsistent federal support [that] creates underinvestment in vital records data infrastructure.” As a result, “death data are neither timely nor granular enough for certain key research purposes” (Data Foundation, 2024).

SOURCE: CDC, 2003. As a work of the U.S. federal government, the image is in the public domain.

Acts (DCRAs) of 20002 and 2013.3 This legislation sought to collect comprehensive statistics on the number of deaths that occur in the custody of law enforcement and at correctional facilities (see Box 3-1) and information regarding the circumstances of those deaths. DCRA 2000,4 which expired in 2006, was reauthorized and amended in DCRA 2013.5 DCRA 2013 (see Appendix C) established “an incentive for states to report in-custody death data by allowing the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) to reduce a state’s allocation under the Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant (JAG) Program6 by up to 10% if [the state does] not comply with reporting requirements” (BJA, 2019b; James, 2023).

To implement the requirements of DCRA 2000, the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), the primary statistical agency of DOJ, created the Death in Custody Reporting Program (later known as the Mortality in Correctional Institutions [MCI] program). Until 2019, this program

collected data on people who died while they were incarcerated in state prisons and local jails. BJS started to collect data on in-custody deaths directly from local jails in 2000 and state prisons in 2001. DOJ reported that BJS was able to obtain an average annual response rate of 98% for local jails and 100% for state prisons. BJS continued to collect these data

___________________

2 Death in Custody Reporting Act of 2000. Pub. L. No. 106-297. 114 Stat. 1045, 2000.

3 Death in Custody Reporting Act of 2013. Pub. L. No. 113-242. 128 Stat. 2860, 2014.

In general, the Acts may be seen as an effort to increase public accountability and transparency as, before DCRA 2000, there was no consistent national system for tracking deaths in custody. State and federal agencies collected some information, but it was fragmented, inconsistent, and often not made public. The Act created a legal requirement for states to report these data to the federal government, ensuring there was a clear record. The 1990s also saw increasing attention to deaths involving law enforcement and carceral facilities, especially in cases where civil rights violations were alleged. Policymakers and advocates pushed for better data collection to identify possible patterns of abuse or neglect, detect racial or demographic disparities in deaths, and support civil rights enforcement by DOJ.

4 Death in Custody Reporting Act of 2000. Pub. L. No. 106-297. 114 Stat. 1045, 2000.

5 DCRA 2013 does not mandate that collected death-in-custody data be made public.

6 Death in Custody Reporting Act of 2013. Pub. L. No. 113-242. 128 Stat. 2860, 2014.

The Edward Byrne Memorial JAG Program “is the leading source of federal justice funding to state and local jurisdictions.” For details about the program, see BJA (2019b).

James (2023) noted that DOJ “has yet to impose a JAG penalty on noncompliant states because states might not have a mechanism to require local governments to report in-custody deaths, and local governments might be more knowledgeable about certain in-custody deaths, such as deaths that occur in law enforcement custody” (p. 11).

BOX 3-1

Types of Carceral Facilities and Numbers Incarcerated

The carceral system consists of different kinds of facilities, each serving different functions and housing different categories of individuals. In this report, the term carceral facility is used generally to refer to facilities where individuals are involuntarily housed.

Those under the care and custody of local, state, or federal correctional authorities are generally housed in one of two types of facilities: jails or prisons.

Local jails confine individuals before or after adjudication and are usually operated by local law enforcement authorities, such as a sheriff; police chief; or county, city, or tribal administrator. Those confined in a jail following criminal convictions are usually sentenced to a term of imprisonment of 1 year or less. Operated by local governments (typically county sheriffs’ departments), county jails detain individuals awaiting trial or serving short sentences (usually less than a year). Regional jails include two or more jail jurisdictions with a formal agreement to operate a jail facility. Jails may house adults, juveniles (in which case they are often referred to as juvenile or youth detention facilities), or both (BJS, 2025).a

Prisons are usually operated under the authority of a state department of corrections (for individuals convicted of state crimes) or the Federal Bureau of Prisons (for individuals convicted of federal crimes). Persons confined in a prison following a criminal conviction typically have been sentenced to a term of imprisonment exceeding 1 year (BJS, n.d.).

Operated by the U.S. Department of Defense, military prisons detain military personnel convicted of crimes under the Uniform Code of Military Justice. A notable example is the United States Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

The term detention center can refer to a facility that holds people awaiting deportation or arrest processing. It is also a general term encompassing short-term police lockups, jails, prisons, prison camps, and other facilities.

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security operates two kinds of facilities. Customs and Border Protection operates detention facilities to house individuals accused of immigration violations, typically for no longer than 72 hours. For longer detention, individuals are transferred to an immigration detention center operated by Immigration and Customs Enforcement, where they are held awaiting deportation or resolution of their immigration cases.

It is difficult to provide an authoritative count of the number of individuals in custody in carceral facilities in the United States, given fluctuations in the incarcerated population and the absence of a system that collects data across various facility types. However, the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) reported that at the end of 2022, “correctional authorities in the United States had jurisdiction over 1,230,100 persons in state or federal prisons”b (BJS, 2023, p. 1); and, in mid-2023, “local jails held 664,200 persons in custody” (BJS, 2025).

Sawyer and Wagner (2025) provide further detail on those held in carceral systems in the United States:

[T]hese systems hold nearly 2 million people in 1,566 state prisons, 98 federal prisons, 3,116 local jails, 1,277 juvenile correctional facilities, 133 immigration detention facilities, and 80 Indian country jails, as well as in military prisons, civil commitment centers, state psychiatric hospitals, and prisons in the U.S. territories. (p. 1)

__________________

a Many of the data about those in custody come from the BJS of the U.S. Department of Justice. BJS issues reports on many topics related to incarcerated individuals in local, state, and federal facilities. It is important to recognize, however, that BJS does not routinely issue updates to its reports and that collected data are not necessarily comprehensive and accurate. BJS data can be supplemented by data collected by other government agencies, researchers, investigative journalists, and nonprofit organizations, but it is an immense challenge to aggregate data from multiple sources to provide comprehensive, timely, and accurate numbers on those in custody, their conditions, and deaths that occur in custody. It is important to keep in mind when considering the data cited in this report.

b “An estimated 32% of sentenced state and federal prisoners were black; 31% were white; 23% were Hispanic; 2% were American Indian or Alaska Native; 1% were Asian, Native Hawaiian, or Other Pacific Islander.” “The 2022 imprisonment rate for black persons (1,196 per 100,000 adult U.S. residents) was more than 13 times the rate for Asian, Native Hawaiian, or Other Pacific Islander persons (88 per 100,000); 5 times the rate for white persons (229 per 100,000); almost 2 times the rate for Hispanic persons (603 per 100,000); and 1.1 times the rate for American Indian or Alaska Native persons (1,042 per 100,000)” (BJS, 2023, p. 13).

even after the requirements of DCRA 2000 expired in 2006, ultimately collecting data until 2019.” (James, 2023)7

Data elements collected included demographics, offense(s) for which the person was held, location and time of death, and manner of death. BJS asked for detailed information related to manner of death that it then classified using International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision codes. 8

___________________

7 BJS stopped collecting data through the MCI when the Office of Management and Budget “determined that there was significant overlap between the data collected through MCI and [the] DCRA program and [that] reporting to both programs would have been burdensome to states” (James, 2023).

8 Presentation to the committee, Kevin Scott, Acting Director, Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice, June 17, 2024.

“The 10th edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) is a medical coding system designed by the World Health Organization (WHO) to catalog health conditions by similar disease categories under which more specific conditions are listed, thus mapping complex diseases to broader morbidities” (AAPC, 2025). The United States uses its own variation.

BJS in 2003 “started the Arrest-Related Deaths (ARD) program to implement DCRA 2000 requirements pertaining to deaths that occurred when someone was in the process of being arrested” (James, 2023).9 The program relied on state coordinators to identify and report all eligible arrest-related deaths. BJS determined in 2011 that it was undercounting arrest-related deaths,10 and the program was discontinued in 2014 “over concerns about data quality and coverage issues.” 11,12

BJS created the Federal Deaths in Custody Reporting Program, which, starting in fiscal year (FY) 2016, surveys federal law enforcement agencies on an annual basis about deaths that fall under the scope of DCRA (BJS, 2020),13 and “federal law enforcement and correctional agencies continue to report deaths that occur in their custody to BJS on an annual basis” (BJA, 2022).

___________________

9 Data elements collected included demographics, circumstances of the death, location and time of death, and manner of death (Scott, 2024).

10 “The program relied on state reporting coordinators in each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia to identify and report on all eligible cases of arrest-related deaths. BJS ultimately determined...that the data collected did not meet BJS data quality standards as the program identified only about half of the arrest-related deaths that occurred each year” (DOJ, 2016, p. 7).

11 11 BJS concluded that underestimation problems with the ARD program were attributable, in part, to ‘the reliance on centralized state-level reporters who lacked standardized modes for data collection, definitions, scope, participation, and available resources’” (James, 2023).

12 Coverage of arrest-related deaths was less complete than coverage of deaths occurring in local jails and state prisons, with only 36 states reporting arrest-related deaths every year between 2003 and 2011 (47 states reported in 2011) (Scott, 2024).

While BJS has no active data collection on arrest-related deaths at the state and local levels (and no plans to restart its lapsed collection), the agency, in an effort to improve measurement of arrest-related deaths, piloted a program to collect data using a combination of open-source methods with machine learning, paired with surveys of law enforcement agencies associated with deaths and the medical examiner/coroners associated with the law enforcement agency (Scott, 2024).

“Instead of relying solely on States to affirmatively submit information on reportable arrest-related deaths, BJS” employed “a mixed method, hybrid approach that used open sources to identify eligible cases, followed by data requests to law enforcement, medical examiners, and/or coroner offices for incident-specific information about the decedent and circumstances surrounding the event. During the follow-up, BJS also would request information on other arrest-related deaths that had not been identified through open sources. The results of the redesigned ‘open source review’ approach showed substantial improvements in data coverage and quality” (DOJ, 2016, p. 7). Notably, the open-source review found 386 possible deaths between June and August 2015. A BJS survey of law enforcement agencies and medical examiners/coroners resulted in response from at least one of the two for 93 percent of the possible deaths. Law enforcement agencies confirmed 296 deaths and identified 48 additional deaths (Scott, 2024).

13 Scott, 2024.

While BJS continues to collect death-in-custody data from federal law enforcement agencies, in 2016,14 DOJ determined that the Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA),15 the agency that “administers the Byrne JAG program and the compliance and penalty determinations that program requires,” should manage the collection of the state and local data required by DCRA 2013.16 BJS would cease to “administer the DCRA collection because its compliance is tied to the administration of the Byrne JAG Program, and BJS’s statistical directives make clear that it ‘must function in an environment that is clearly separate and autonomous from the other administrative, regulatory, law enforcement, or policy-making activities’ of the Department” (DOJ, 2016, p. 8).17

However, this approach has come with substantial challenges. In a presentation to the committee, Michelle Garcia, BJA, stated,

BJA is a grant-making organization and . . . what had been a function of one of our research arms [BJS] of OJP [the DOJ Office of Justice Programs] has now gone over to a grantmaking agency that did not have the infrastructure in place originally to be able to fully execute. [It took a] little bit of time . . . to develop the questionnaire, develop the performance management system to be able to collect data from states, to socialize this with states so they understood what their responsibilities were in collecting and reporting the data, to make sure we had the appropriate staffing to support the states in doing this work, to look at data, to see where there are gaps, to work with open source data. It definitely took time . . . to get to where we are now, where we think we are supporting the states very well in what they are doing. . . . We know that the states still have challenges. And we still do not have complete data.

___________________

14 The 2016 date is implied by the press release available at https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-announces-new-steps-expand-vital-law-enforcement-data-collection.

15 BJA was created in 1984 “to reduce violent crime, create safer communities, and reform” the U.S. criminal justice system. Its “mission is to provide leadership and services in grant administration and criminal justice policy development to support state, local, and tribal justice strategies to achieve safer communities” (BJA, 2019a).

16 The 2016 date is implied by the press release available at https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-announces-new-steps-expand-vital-law-enforcement-data-collection.

17 BJS was not precluded from collecting federal death-in-custody data, however, because DCRA 2013 did not impose a financial penalty on federal agencies that failed to provide data (presentation to the committee, Alexis Piquero, Professor, University of Miami, April 2, 2024).

BJS was established on December 27, 1979, under the Justice Systems Improvement Act of 1979. Pub. L. No. 96-157. 93 Stat. 1167, 1979.

Beginning with the first quarter of FY 2020, states were required to submit in-custody data to BJA’s Performance Measurement Tool (PMT)18 via JAG Program State Administering Agencies (SAAs).19 SAAs are responsible for compiling data “from state and local entities including law enforcement agencies, local jails, correctional institutions, medical examiners, and other state agencies and submitting the data to BJA” (BJA, 2022). “For each death in custody, SAAs must enter the following information into the PMT:

- The decedent’s name, date of birth, gender, race, and ethnicity

- The date, time, and location of the death

- The law enforcement or correctional agency that detained, arrested, or was in the process of arresting the deceased

- A brief description of the circumstances surrounding the death” (BJA, 2022).

If SAAs do not have sufficient information to complete certain data elements, they may enter “unknown” for those data values (when allowed in the PMT). “For cases that remain under investigation, the ‘manner of death’ should be reported as ‘Unavailable, Investigation Pending,’” and SAAs “should specify when they anticipate obtaining the information” (BJA, 2022).

BJA has acknowledged the challenges facing the agency in collecting state death-in-custody data. It has found it difficult to obtain timely and accurate data reporting. States fail, for example, to submit reports; submit reports with “0” reportable incidents; or submit reports with incomplete or inaccurate data. Further, SAAs often do not have the funding, resources, or time to correct data issues and lack communication avenues or credibility with state and local agencies. Collecting law enforcement data has been particularly challenging.

In 2022, the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Government Affairs released a report on DOJ’s implementation of the requirements of DCRA 2013. The report asserted that “DOJ failed to properly manage the transition of DCRA 2013 data collection from BJS to BJA” and that “BJA’s failure to properly collect and report on custodial death data stands in marked contrast to

___________________

18 The PMT is available at https://ojpsso.ojp.gov/. A document that describes steps users must take to use the Death in Custody Reporting Act Import Feature is available at https://bja.ojp.gov/funding/performance-measures/DCRA-PMT-Import-Feature-User-Guide.pdf.

19 “State Administering Agencies (SAAs) are entities within state and territorial governments and the District of Columbia that are responsible for comprehensive criminal justice planning and policy development. In addition, these agencies allocate resources statewide and distribute, monitor and report on spending under the” Byrne Memorial JAG “program and, in most cases, other grant programs” (NCJA, n.d.).

BJS’s successful efforts to do these same things for 20 years” (U.S. Senate Committee on Homeland Security & Governmental Affairs, Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, 2022, p. 5). Further, “to the extent that DOJ sought to assign DCRA 2013 responsibilities to BJA, it should have done more to equip it with the resources and strategies it already knew to be successful so that DOJ could meet its statutory obligations” (U.S. Senate Committee on Homeland Security & Governmental Affairs, Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, 2022, p. 5). The report concluded that

DOJ’s failure to implement DCRA has deprived Congress and the American public of information about who is dying in custody and why. This information is critical to improve transparency in prisons and jails, identifying trends in custodial deaths that may warrant corrective action—such as failure to provide adequate medical care, mental health services, or safeguard prisoners from violence—and identifying specific facilities with outlying death rates. DOJ’s failure to implement this law and to continue to voluntarily publish this information is a missed opportunity to prevent avoidable deaths. (U.S. Senate Committee on Homeland Security & Governmental Affairs, Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, 2022, p. 6)

Separately, a 2022 U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO, 2022) report discussed DOJ’s response to DCRA 2013 requirements, including its collection, study, and use of data to reduce deaths in custody. GAO (2022) found that, despite multiyear efforts by states and DOJ to collect death-in-custody data, DOJ had not studied the state data because they were incomplete.20

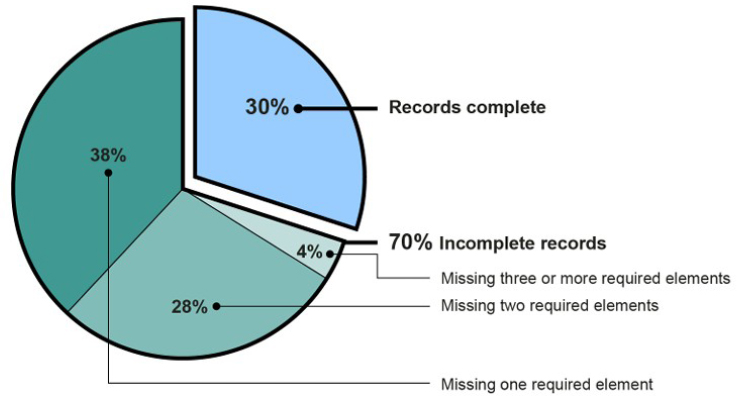

GAO (2022) compared FY 2021 records that states submitted to DOJ with publicly available data; it identified nearly 1,000 deaths that potentially should have been reported to DOJ but were not. Further, “70 percent of the records provided by states were missing at least one element required by DCRA, such as a description of the circumstances surrounding the individual’s death or the age of the individual” (GAO, 2022, p. 9; see Figure 3-2).

In FY 2023, BJA required states to submit a DCRA State Implementation Plan that describes how a state will collect data on in-custody deaths and report them to BJA (BJA, 2024a). DOJ will then determine each state’s

___________________

20 In her June 17, 2024, presentation to the committee, Michelle Garcia, BJA, stated,

When we talked [to GAO] in 2022, absolutely we had no intent of releasing the data at that time because it would give a skewed picture because it was incomplete from all the states. We are now talking about what level of data to release and when to release that, and we do intend to release some data but it’s a matter of being [able to] stand behind the data we have from the states.

BJA began posting data in November 2024 (see footnote 25).

NOTE: GAO analyzed fiscal year 2021 data the U.S. Department of Justice collected from states in response to the Death in Custody Reporting Act, as of November 16, 2021. Required elements include biographical information on the deceased, as well as the date, time, and location of death; the law enforcement agency that detained, arrested, or was in the process of arresting the deceased; and a brief description of the circumstances surrounding the death.

SOURCE: GAO, 2022, p. 9. As a work of the U.S. federal government, the image is in the public domain.

compliance with DCRA reporting requirements annually.21 According to BJA (2023), compliance is determined based on the following:

- BJA-approved DCRA State Implementation Plan (with annual resubmission/report in subsequent fiscal years)

- Comprehensive, complete, and accurate DCRA reports provided to BJA quarterly

- Evidence of continuous quality improvement where gaps and challenges are identified

Additionally, BJA will conduct annual reviews of open-source records to identify unreported deaths in custody (BJA, 2023).

___________________

21 As of September 26, 2024, BJA had approved implementation plans for the 50 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Approved implementation plans are available at https://bja.ojp.gov/program/dcra/state-implementation-plans.

DEATH-IN-CUSTODY DATA

The challenges of data collection persist, and the lack of comprehensive data on deaths in custody limits the utility of available data. Nonetheless, data collected by government agencies, researchers, investigative journalists, and nonprofit organizations provide a partial picture of the numbers of deaths in custody.22

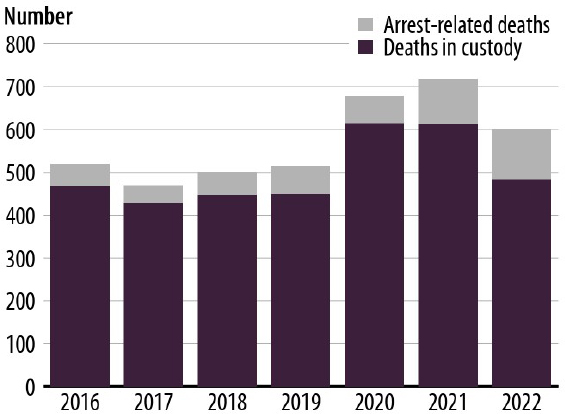

Federal Data

BJS (2024a) data indicate that in FY 2022, U.S. federal law enforcement agencies reported 120 arrest-related deaths and 483 deaths in custody (see Figure 3-3). “From FY 2016 to FY 2022, federal agencies reported an average of 72 arrest-related deaths and 501 deaths in custody each year. From FY 2021 to FY 2022, arrest-related deaths figures increased by 14% and deaths in custody decreased by 21%. The manner of these deaths included homicide, suicide, illness/natural, accident, other, and unknown means” (BJS, 2024a, p. 1).23

State and Local Data

Because death-in-custody data have not been collected or reported uniformly across states and local jurisdictions,24 it is difficult to draw conclusions across jurisdictions or make determinations regarding the quality

___________________

22 While not discussed in the current report, another potential source of data on deaths in custody is judicial opinions in cases where the decedent’s family members sue for damages.

23 Accidents accounted for the largest portion (40 percent) of reported arrest-related deaths in FY 2021, followed by homicides (32 percent) and suicides (23 percent). In FY 2021, about 89 percent of decedents in arrest-related deaths were male, 73 percent were White, and 65 percent were ages 25 to 44. In 44 percent of arrest-related deaths in FY 2021, law enforcement officials were serving a warrant when they made initial contact with the decedent. An immigration violation was the most serious offense allegedly committed by decedents in 46 percent of arrest-related deaths in FY 2021. The majority (80 percent) of the 613 deaths in custody in FY 2021 were due to natural causes or illnesses (including HIV/AIDS), followed by suicide (10 percent). In FY 2021, about 96 percent of those who died in custody were male, 62 percent were White, 32 percent were black, and 53 percent were age 55 or older. The most commonly reported offenses for persons who died in custody in FY 2021 were drug violations (33 percent), followed by sex offenses (17 percent) and weapons violations (16 percent). The 21 percent decrease may be attributable to a decrease in COVID-19-related deaths following the institution of widespread vaccinations against the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

24 In reviewing DCRA State Implementation Plans, the Project on Government Oversight found that “only eight states reported that they had their own laws requiring police, jails, and prisons to regularly report deaths in custody to state authorities. A somewhat larger set of states reported having laws that require a subset of deaths in custody be reported, most often focusing on deaths in jails” (Janovsky, 2024).

NOTE: Excludes federal executions in FY 2020–2022.

SOURCE: BJS, 2024a. As a work of the U.S. federal government, the image is in the public domain.

or value of reported state and local data. Nevertheless, available data shed light on the extent of occurrences of deaths in custody.

In 2019, BJS found that the total number of persons who died in state prisons or private prison facilities under a state contract was 3,853 and that 1,200 individuals died in local jails (BJS, 2021a, 2021b). Notably, the statistics do not include numbers of arrest-related deaths. Reported local jail deaths increased more than 5 percent between 2018 and 2019 and more than 33 percent between 2000, when BJS began its MCI data collection, and 2019 (BJS, 2021a). Box 3-2 provides a summary of the demographic and criminal justice profile of jail decedents.

While DCRA 2013 does not mandate the public release of data, BJA recently published data for thousands of in-custody deaths it has collected from states, territories, and the District of Columbia for FY 2000–2023.25 The data can be filtered by state, year, location type, manner of death, and demographics. When publishing the data, BJA (2024b) made important disclaimers about their completeness and accuracy:

___________________

25 See BJA, 2024b. The data, which are available at https://bja.ojp.gov/program/dcra/reported-data, were first posted online on November 15, 2024. The webpage was modified on December 19, 2024 and January 6, 2025. At the time of the publication of this report, the page lists 5,674 deaths in FY 2020, 6,909 deaths in FY 2021, 6,085 deaths in FY 2022, and 6,725 deaths in FY 2023.

BOX 3-2

Jail Decedents in 2019

Reporting on data from 2019, the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS, 2021c) indicated that 636 jail jurisdictions reported at least one death in that year, and 222 reported two or more deaths. BJS (2021c) included analysis of these data by conviction status, jail size, and cause of death.

More unconvicted (i.e., pretrial) (192 deaths per 100,000) individuals than convicted (112 per 100,000) individuals died in custody in 2019. “Almost 77% of the 1,200 persons who died in local jails in 2019 were not convicted of a crime at the time of their death. . . . Almost 40% of inmates who died in local jails in 2019 had been held for 1 week or less” (BJS, 2021c, p. 1).

Residents were much more likely to die if they were in a small jail (264 deaths per 100,000 in jails with fewer than 50 residents) than if they were in a large jail (161 deaths per 100,000 in jails with more than 2,500 residents). “Jails with an average daily population of 49 or fewer inmates had the highest mortality rates each year from 2000 to 2019” (BJS, 2021c, p. 1).

Suicide was the leading single cause of death for those in jail in 2019, with 49 deaths per 100,000 individuals. “When the U.S. resident population was adjusted to resemble the sex, race or ethnicity, and age distribution of local jail inmates, inmates were more than twice as likely as U.S. residents to die by suicide in 2019.” And that year, drug- or alcohol-related deaths in local jails were the highest in BJS’s 20-year recorded history (BJS, 2021c, p. 1).

- “BJA is publishing these tables that reflect the information that has been reported by the states. BJA, the Office of Justice Programs, and the Department of Justice make no representations about the completeness or accuracy of this information. This information does not constitute official statistics of the federal government and does not comport with the Information Quality Guidelines of the Department of Justice or Office of Justice Programs. Caution should be taken when interpreting or using this information. States are routinely asked to review, add, and update information. As such, BJA will periodically update the data.” (emphasis added)

- “While states are responsible, under the DCRA statute, for submitting DCRA data to the Department, all of the data originate with entities other than the State Administering Agencies responsible for collecting and submitting the data, including state Departments of Corrections, local law enforcement agencies, local or county jails, and medical examiners or coroners. BJA continues to provide

- training and technical assistance to support states in improving the quality and completeness of all submitted data.”

- “The number of deaths reported to the BJA DCRA program by the states is influenced by a variety of factors including total number of actual reportable incidents, participating state and local agencies, state laws, and state and local procedures related to DCRA data collection and reporting. Accordingly, this data cannot necessarily be used to make accurate comparisons among states. Furthermore, year-to-year comparison or trends are also discouraged due to fluctuations in data reporting over time.” (emphasis added)

DCRA 2013 required the attorney general to carry out a study to determine means by which collected death-in-custody “information can be used to reduce the number of such deaths” and to “examine the relationship, if any, between the number of such deaths and the actions of management of such jails, prisons, and other specified facilities relating to such deaths.”26

To meet this requirement, the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) commissioned two studies. The first, Literature Review and Data Analysis on Deaths in Custody (Duwe, 2022), focused on the “prevalence, patterns, and contexts of deaths in custody”; discussed the “limitations of the existing research”; and presented the findings of an “analysis of data on mortality in correctional institutions” (p. 2).

Building on the first study, in late 2021, NIJ contracted with RTI International to conduct a second, broader “national-level review and analysis of policies, practices, and available data addressing deaths in custody, along with in-depth case studies of multiple sites and agency types” (Duwe, 2022, p. 2). Understanding and Reducing Deaths in Custody: Interim Report (RTI, 2024c) describes findings from the national-level literature and policy review, as well as secondary analyses of existing data, organized by the three main contexts in which deaths in custody occur: jails, prisons, and law enforcement. Based on the study’s findings and existing research, NIJ issued an interim report to Congress encouraging agencies and others “to use existing evidence to increase safety and reduce deaths” (NIJ, 2024c, p. 2). A second report, Understanding and Reducing Deaths in Custody: Case Study Report, describes findings from case studies with 10 criminal justice agencies to “understand the policies, programs, and practices that practitioners engage in to prevent or reduce deaths in custody” (RTI, 2024a, p. 7).

A third, supplemental, report, Understanding and Reducing Deaths in Custody: Analysis of the Bureau of Justice Assistance Death in Custody Reporting Act (DCRA) Data (RTI, 2024b), assesses DCRA data reported to BJA for calendar years 2020–2023, the first full years when BJA had

___________________

26 Death in Custody Reporting Act of 2013. Pub. L. No. 113-242. 128 Stat. 2860, 2014.

responsibility for the collection of death-in-custody data (RTI, 2024b). The report examines BJA DCRA data on arrest-related, jail, and state prison deaths and compares them with other federal and open-source data (RTI, 2024c; see also Burghart, 2025). RTI (2024b) notes important caveats:

The years of data available through these collections and the definitions used in some classifications of deaths do not align with available DCRA data collected by BJA, hindering the ability to make direct year-to-year comparisons between sources. . . . The lack of data with which to make direct comparisons poses a challenge in assessing BJA DCRA data quality against other sources, though comparisons may still be made between the relative patterns and distributions of decedents across datasets, which can still be informative. (p. 2)

That said, RTI (2024b) found that the number of arrest-related deaths reported to BJA was close to the number of officer-involved shootings reported by the Washington Post (RTI, 2024b, p. 3). In comparing BJA data with MCI data, RTI (2024b) noted that BJA’s 2020 data reflected about half the jail deaths found in the 2019 MCI data; however, those numbers align better in the two sets of data from 2021 through 2023. Data on prison deaths “appears to be the most similar between the counts reported through the DCRA data collection and the [MCI] collection” (RTI, 2024b, p. 3). RTI (2024b) concluded that, “in sum, the prevalence of each death type seems to be fairly consistent with other data sources, and the relative patterning of deaths across sectors is consistent with what was reported through the DCRA data collection” (pp. 3–4).

The number of jail and arrest-related deaths reported to BJA has increased over time, but the number of prison deaths remained relatively stable (RTI, 2024b, p. 27). Decedent demographics varied by context. RTI (2024b) found that

[f]or ARDs, death caused by use of force was the most prevalent manner of death, followed by suicide, then accidents. In jails, the most prevalent classification was “unavailable pending an investigation,” followed by natural causes, then suicide. In prisons, the most prevalent manner of death was natural causes, followed by unavailable pending an investigation, then suicide. (p. 27)

For jail and arrest-related deaths, individuals between the ages of 25 and 44 had the highest death-in-custody rate. In prisons, individuals aged 55 and older had the highest rate of in-custody death. Male deaths were more prevalent than female deaths in all contexts. Deaths involving White

individuals were most prevalent and were followed by Black individuals, then non-Hispanic individuals (RTI, 2024b).

The report noted that “existing categories related to the manner of death are broad, possibly because the different sectors (i.e., law enforcement, jails, prisons) share the same categories” and suggested that more specific categories for common manners of death “may be more informative for policy and practice” (e.g., creating categories for arrest-related deaths that break down the “use of force” or “homicide” categories could inform the tracking of trends in arrest-related deaths) (RTI, 2024b, p. 28). Similarly, “[t]racking different types of deaths related to natural causes (e.g., heart disease, cancer) in correctional settings would also be informative” (RTI, 2024b, p. 28).

Other efforts to collect state death-in-custody data include Incarceration Transparency, a project of the Loyola University New Orleans College of Law.27 On the basis of public records requests filed with 122 facilities across the state and six coroners, Incarceration Transparency reported that from 2015 to 2021, at least 1,168 people died in custody in Louisiana. Of these individuals, 57.53 percent were Black and 40.58 percent were White (Incarceration Transparency, 2023a, p. 7).28 “Approximately 86% of known deaths behind bars were of people serving a sentence for conviction of a crime. Deaths of people being held pre-trial, i.e. had not yet had a trial on their criminal charges, constituted 13.44% of all known deaths” (Incarceration Transparency, 2023a, p. 20). “The most impacted group of people who died behind bars were Black males, age 55 or older, serving sentences post-conviction” (Incarceration Transparency, 2023a, p. 2). “Medical conditions were the primary cause of death for all known deaths” (Incarceration Transparency, 2023a, p. 3). “Parish jails accounted for 25% of all known deaths 2015-2021. The majority of accidental, suicide, and drug overdose deaths occurred in parish jails, which house both convicted and pre-trial populations” (Incarceration Transparency, 2023a, p. 4).

A parallel effort in South Carolina reported that “from 2015 to 2021, at least 777 people died behind bars in at least fifty-two prisons, jails, and detention centers across” the state (Incarceration Transparency, 2023a, p. 3). Of these deaths, “Black people accounted for 49.03% of deaths (381) and white people comprised 49.03% of deaths (381). The remaining 15 deaths (1.9%) listed race as unknown” (Incarceration Transparency,

___________________

27 Incarceration Transparency tasks upper-level law students with gathering data through an annual seminar on incarceration, taught by Professor Andrea Armstrong of the Loyola University New Orleans College of Law. See https://www.incarcerationtransparency.org/.

28 In Louisiana in 2024, it was estimated that 32.6 percent of the population was Black and 62.6 percent of the population was White (U.S. Census Bureau, 2024a).

2023a, p. 10). In South Carolina, “men represent 93% of people incarcerated after conviction, while women comprise only 7%. Men accounted for 93.82% of known deaths behind bars (729) versus 6.18% (48) for women. Medical deaths were the leading cause of death for both men and women and made up 66.67% (32) of women’s deaths and 67.63% (493) of men’s deaths.”29

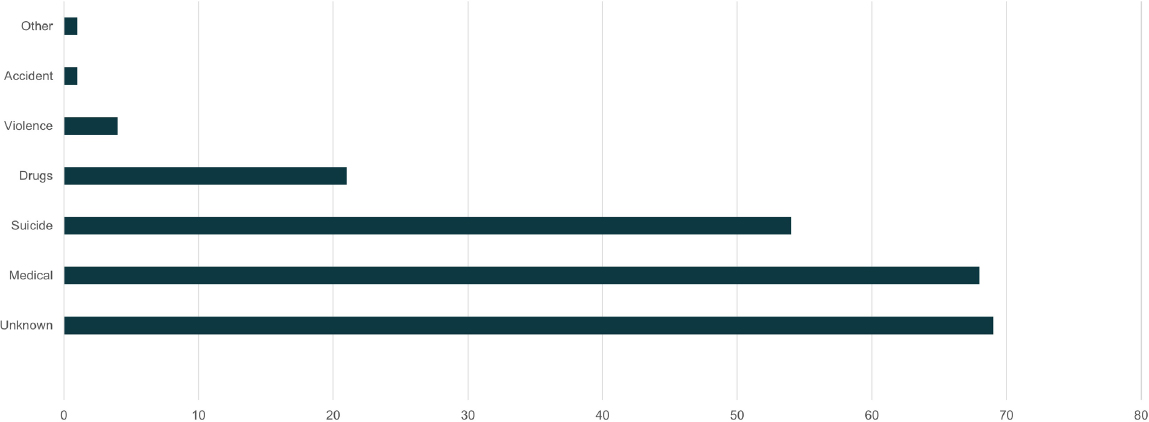

“Approximately 85% of people who died behind bars were convicted and serving a sentence for a crime. One hundred nine people who remained legally innocent and awaited trial represented 14.03% of known deaths from 2015-2021. People also died in jails while they were civilly committed (1 death), on a parole hold (1 death), or on a probation hold (2 deaths)” (Incarceration Transparency, 2023b, p. 19). For a breakdown of causes of jail deaths from 2015 to 2021, see Figure 3-4.

In Pennsylvania, a 2023 investigation by PennLive and the Pittsburgh Institute for Nonprofit Journalism led to the creation of the first comprehensive database of deaths in custody in the state: 65 deaths in custody were identified across the state’s 67 counties in 2022, with only 40 being reported as required. “In all, at least 28 counties had someone die while in custody. This means 39 counties reported no deaths.” Suicide was the most common manner of death in all but one county and accounted for about 40 percent of all deaths in jail. Nine deaths were classified as accidental, most of which were overdoses (but one person choked, and one man drowned in his cell in Philadelphia). Two men died by homicide, and only one death was listed as undetermined (Vaughn and Hailer, 2023).

The Associated Press (AP), in collaboration with the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism programs and FRONTLINE (PBS), conducted an investigation to track nonshooting deaths at the hands of law enforcement between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2021. The investigation identified 1,036 deaths following encounters with law enforcement that involved less-lethal force.30 It found that

___________________

29 “Black South Carolinians represent about 61% of those sentenced to state prisons, compared to 36% white people, and 3% other” (Incarceration Transparency, 2023b, p. 10).

In South Carolina in 2024, it was estimated that 26 percent of the population was Black and 69 percent of the population was White (U.S. Census Bureau, 2024d).

30 To be included, deaths had to involve “at least one type of force, restraint or less-lethal weapon beyond handcuffs. Holding someone face down in what is known as prone restraint and Tasers were the most prevalent types of force. Blows with fists or knees, takedowns and devices to restrain people’s legs were also common. Less so were chokeholds, pepper spray, spit hoods, dog bites and bean bag rounds fired through a shotgun. Reporters excluded deaths by firearm and car crashes after police pursuits.” See https://apnews.com/projects/investigation-police-use-of-force/methodology/.

SOURCE: Madalyn K. Wasilczuk, Associate Professor of Law, University of South Carolina Joseph F. Rice School of Law. Data are derived from Incarceration Transparency (2023b).

more than 800 of the more than 17,000 law enforcement agencies in the U.S. had at least one documented fatality . . . [and that] the nation’s 20 largest cities accounted for 16% of deaths. . . . In all, about 270 of the 1,036 cases AP identified did not appear in any of three well-known, public databases that include non-shooting deaths. (Stevens, Pritchard, and Wieffering, 2024)31

The investigation revealed the following:

- In 740 cases, one or more officers restrained the deceased face down on their stomach, often using body weight.

- In 538 cases, one or more officers used an electronic control weapon (i.e., a taser or stun gun), firing darts intended to cause neuromuscular incapacitation and/or using the weapon directly against the body as a pain compliance technique, known as “drive-stun.”

- In 229 cases, the police encounter was in or near the home of the deceased (this was the most common location).

- In 94 cases, paramedics or other medical staff gave the deceased sedatives during the police encounter.

- In 142 cases, the cause of death cited excited delirium.

- In 28 cases, at least one officer was criminally charged in the death.

- More White people died than any other group, but Black people were disproportionately affected (333 cases).

- In 271 cases, manner of death was ruled a homicide by medical examiner, coroner, or similar official.

- In 443 cases, manner of death was ruled an accident by medical examiner, coroner, or similar official.

- In 48 cases, manner of death was ruled natural by medical examiner, coroner, or similar official.

- In 186 cases, manner of death could not be determined by medical examiner, coroner, or similar official.32

In addition to the 1,036 cases identified by the AP, there were about 100 others that reporters had reason to believe may be cases based on news reports or lawsuit allegations. These cases are not currently in the database

___________________

31 In correspondence dated September 4, 2024, Justin Pritchard, Investigative Editor and Reporter, The Associated Press, stated that the “three well-known public databases” are Fatal Encounters (Burghart, 2025), Mapping Police Violence (Campaign Zero, 2025), and the Reuters database cataloging taser deaths (Reuters, n.d.).

32 See https://apnews.com/projects/investigation-police-use-of-force/all-cases/.

because reporters have not yet independently confirmed the details, sometimes because agencies refused to release information.33

CONCLUSIONS

Conclusion 3-1: The United States does not collect comprehensive and reliable data on deaths in custody despite efforts, such as DCRA 2000 and 2013, to make mandatory the reporting of deaths in custody.

Conclusion 3-2: Deaths in custody are not accurately or routinely reported.

Conclusion 3-3: The cause and manner of death reported on death certificates may not be supported by (or be consistent with) investigatory findings.

Conclusion 3-4: Data collected by CDC’s National Violent Death Reporting System provide valuable information about violent deaths, but they do not indicate whether a death occurred while a decedent was in custody (except, for instance, in cases where deaths were caused by law enforcement acting in the line of duty).

Conclusion 3-5: Comprehensive, accurate data on deaths in custody could be leveraged to improve the MLDI system by raising awareness of the importance of these data for public health and criminal justice.

Conclusion 3-6: Knowledge of the circumstances of deaths in custody can improve our understanding of cases of those suffering from a similar disease or injury, lead to preventive measures that enhance population health, lower the costs of incarceration, and foster new approaches to preventing deaths in custody through the stimulation of evidence-based innovation and quality improvement.

___________________

33 See https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/reporters-documented-1000-deaths-police-use-less-lethal-force/.

This page intentionally left blank.