Strengthening the U.S. Medicolegal Death Investigation System: Lessons from Deaths in Custody (2025)

Chapter: 2 The Medicolegal Death Investigation System in the United States

2

The Medicolegal Death Investigation System in the United States

As noted in Chapter 1, the medicolegal death investigation (MLDI) system is responsible for conducting death investigations and certifying the cause and manner of unnatural and unexplained deaths (Zaychik, 2024). The individuals entrusted with determining cause and manner of death rely on a careful examination of the body (which may include an autopsy performed by a forensic pathologist or other medical professional), examination of the circumstances of the death, analysis of medical records (including the patient’s medical history) and the results of toxicology and other laboratory tests, and evidence collected from the scene of death.

This chapter discusses the evolution of the MLDI system in the United States, the individuals who conduct medicolegal death investigations and their qualifications; standards for conducting medicolegal death investigations; and the role of coroners, medical examiners, and forensic pathologists in the public health and criminal justice systems.

THE EVOLUTION OF MLDI SYSTEMS

MLDI systems have their roots in the coroner system of medieval England. The term coroner is derived from the Norman-French word corouner, which means “crown officer.” The coroner’s role initially involved investigating deaths that were sudden, unexpected, or suspicious to determine the cause of death and whether foul play was involved and, if foul play was suspected, to identify the perpetrator. The function of a coroner was closely tied to the crown’s interest in maintaining law and order within the realm (IOM, 2003, p. 8).

The office of coroner was formalized in England during the 12th century under the reign of King Richard I. The crown appointed coroners who typically were local officials with legal and investigative authority. Over time, the coroner’s duties expanded to include holding inquests to determine the cause of death in cases where cause was unclear or disputed.

The coroner system in the United States is inherited from English law. In early American history, coroners typically were elected officials responsible for investigating deaths within their jurisdiction and determining whether they warranted further legal action, such as a criminal investigation or the initiation of probate proceedings.

In 1860, the state of Maryland, recognizing that coroners needed medical expertise, enacted legislation empowering coroners to mandate the presence of physicians during inquests (NRC, 2009, p. 241). In 1877, Massachusetts established an important national precedent when it replaced coroners with medically qualified examiners. Physicians serving as medical examiners began performing autopsy procedures for coroners in Baltimore in 1890. In 1918, before forensic pathology had emerged as a medical subspecialty, New York City established the country’s first medical examiner system when it appointed a designated pathologist as its chief medical examiner. These developments reflected the public’s growing insistence on medical proficiency and qualifications in conducting death investigations.

In 1928, the National Research Council of the National Academy of Sciences released a report that provided a critical assessment of the coroner system in the United States. The report recommended abolishing the coroner’s office, transferring its medical duties to a medical examiner’s office led by a trained pathologist, and equipping the office with necessary scientific staff and equipment. It also called for the establishment of medicolegal institutes for the purpose of providing medical examiners an opportunity for hospital and university affiliation, emphasizing a greater role for physicians in forensic science and legal proceedings (NRC, 1928). The report spurred an initial shift from coroners to medical examiners in the United States (IOM, 2003).1 And, in 1954, the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws issued the Model Post-Mortem Examinations Act, which provided an early model for medical examiner post-mortem examinations.

___________________

1 Between 1960 and 1979, 12 states transitioned from coroner-led to medical examiner–led systems. From 1980 to 1999, three additional states made this transition. As of March 2024, 23 states and the District of Columbia have medical examiner systems; the remaining states are largely served by coroners (see CDC, 2023).

THE MLDI SYSTEM IN THE UNITED STATES

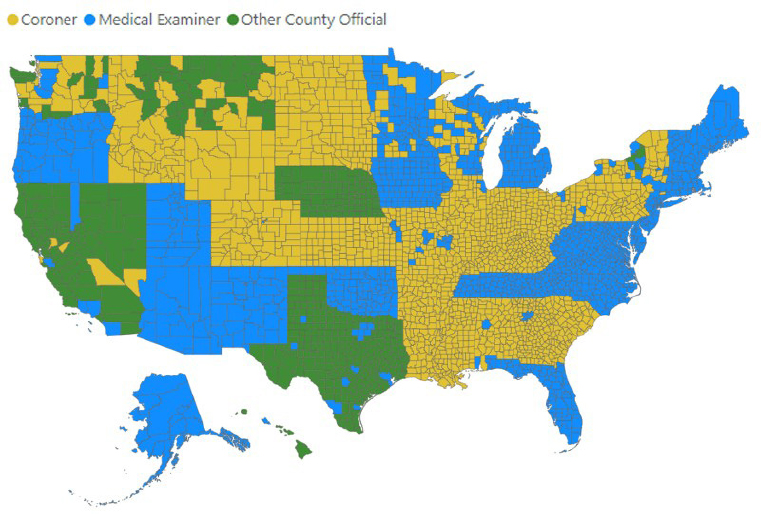

Today, medicolegal death investigations are conducted under three systems in the United States: coroner systems, medical examiner systems, and systems using other county officials (see Figure 2-1). In some states, all counties have the same type of MLDI system, while the type of system varies by county in others. Some states have local medical examiners, while other states have a centralized state medical examiner system. Each state sets standards for which deaths require investigation and what professional training and continuing education is required for those conducting the investigations (CDC, 2024).

While medical examiners and coroners are generally responsible for determining cause and manner of death, medicolegal death investigators and other medical and criminal justice staff also play important roles in

NOTE: As of 2023, 11 states had coroner systems in place across all counties, and 14 other states had coroner systems serving some of their counties. Another 22 states and Washington, DC, were served entirely by medical examiner systems, including 11 that had a centralized state medical examiner and 3 states that were served by a regional medical examiner. Several states have a mix of the two systems, with some counties served by coroner systems and others by medical examiner systems.

SOURCE: CDC, 2023. As a work of the U.S. federal government, the image is in the public domain.

medicolegal death investigations. In some jurisdictions, the final say in cause and manner of death falls on elected or appointed officials who do not have medical training (The Editors, 2021). In other jurisdictions, death certificates are completed by contracted health care systems, physicians, or wardens.

Coroners

Coroners oversee death investigations and certify cause and manner of death within particular jurisdictions, with specific roles and responsibilities varying by state. In some states, coroners may perform autopsies if they are licensed physicians. In other states, coroners may order autopsies but must rely on medical examiners or forensic pathologists to perform them.

In some jurisdictions, coroners are elected officials or individuals who have been appointed based on administrative qualifications and have administrative oversight of death investigations. In other jurisdictions, coroners are required to be physicians or to have training in forensic pathology or a related medical field.

Elected coroners must meet varying residency, age, and other qualifications. Common coroner qualifications include being a registered voter, meeting minimum age thresholds (typically between ages 18 and 25), an absence of felony convictions, and completion of a training program. In addition to coroners, coroner offices may be staffed by deputy coroners, nurse coroners, medicolegal death investigators, forensic analysts and toxicologists, and administrative staff. However, some coroners do not have offices and operate with very limited budgets and equipment (see, e.g., Box 2-2).

In some jurisdictions, sheriffs perform coroner duties. In California, for instance, there are sheriffs’ departments in all 58 counties. Forty-eight counties “provide for the Sheriff to assume the duties of the Coroner. The Sheriff is a constitutionally elected official. The Coroner, in those counties where the Sheriff doesn’t assume both roles, is responsible for inquiring into and determining the circumstance, manner, and cause of all violent, sudden, or unusual deaths. Some counties have independently elected Coroners and others have appointed Coroners, or Medical Examiners who perform the duties of the Coroner” (Prados et al., 2022, p. 142).

Medical Examiners

Medical examiners are physicians, and in nearly all jurisdictions they are required to have additional specialized training in forensic pathology or a related field. They are responsible for investigating and examining deaths that are sudden, unexpected, or violent. They determine cause and manner of death, utilizing their medical expertise when reviewing medical

BOX 2-1

What Is an Autopsy?

An autopsy is a systematic examination of a body after death that is conducted to determine cause and manner of death. While the time and resources devoted to an autopsy may vary based on the circumstances of a death, the nature of the death, and jurisdiction, autopsies typically involve the following steps:

- After obtaining necessary legal permissions (or operating under statutory authority) and reviewing the circumstances of the death, including police reports, witness statements, and the deceased individual’s medical history, the pathologist conducts an external examination of the body.

- Photographs are taken to document salient information such as visible injuries, scars, and identifying features such as tattoos.

- The body is evaluated for lividity, rigor mortis, and temperature to estimate the time of death.

- Clothing is examined to identify signs of struggle, foreign substances, and other case-relevant evidence.

Depending on the complexity of the case and what is known of the circumstances of death, it may be possible to make a determination of cause and manner of death based upon an external examination. In other cases, a thorough internal examination of a body may be necessary to identify internal conditions (such as disease or internal injury) through gross and microscopic analysis of tissues.

When an internal examination is performed

- Incisions are made to open the chest and abdomen (and sometimes the skull) to allow for inspection of internal organs and tissues.

- Organs are removed and examined for abnormalities or damage, with tissue samples taken for microscopic analysis (in medicolegal autopsies, most tissues are returned to the body, while certain organs are retained for further analysis).

- Toxicological analyses are performed to detect the presence of drugs, alcohol, or other toxins.

When the autopsy is complete, an autopsy report is produced that documents the pathologist’s methods, findings, and conclusions. The report is used to assist in making determination as to the cause and manner of death and often for public health and legal purposes. In some cases, forensic pathologists are called upon to testify in court regarding their findings, methods, conclusions, and determinations of cause and manner of death.

history and conducting physical examinations of the deceased. While medical examiners often have a background in forensic pathology, they are not required to be forensic pathologists.

Medical examiners are typically appointees. A chief medical examiner may lead an office staffed by deputy or assistant medical examiners, medicolegal death investigators, forensic analysts and toxicologists, and administrative staff. These offices may also have chiefs of staff or general counsels. In some localities, medical examiner offices face staff and other resource constraints.

Forensic Pathologists

Forensic pathology is a formal field of study and practice that originated in the early 20th century. A subspecialty of pathology, it focuses on investigating deaths, especially those that are unnatural or suspicious. To make determinations of cause and manner of death, forensic pathologists typically conduct autopsies and other postmortem examinations of the decedent (CAP, n.d.; see Box 2-1). In 20 states, and in Washington, DC, laws require that autopsies be performed only by pathologists (CDC, 2024).

Forensic pathologists undergo rigorous training. After obtaining a medical degree from an accredited medical school, forensic pathologists undertake residency training in anatomical pathology (3 years), combined anatomic and clinical pathology (4 years), or combined anatomic and neuropathology (4 years). During residency, trainees gain experience in pathology (including in the examination of tissues and organs) and autopsy procedures.

After completing residency training, individuals enroll in forensic pathology fellowship programs. Accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and certified by the American Board of Pathology (ABP), these fellowships typically last 1–2 years. During a fellowship period, fellows receive specialized training in forensic pathology and forensic radiology, focusing on forensic autopsy techniques, forensic toxicology, forensic anthropology, and research in forensic pathology.2

___________________

2 Forensic pathologists rely upon a range of skills and expertise as their work requires them to collect various types of evidence from the body, such as biological samples, trace evidence, and foreign objects. They analyze these materials using specialized techniques to identify information that may help determine the cause of death or assist in criminal investigations. They also review medical records, including previous medical history, diagnostic tests, and treatment regimens, to gain insights into the deceased individual’s health status and any underlying medical conditions that may have contributed to the individual’s death. In cases where the identity of the deceased is unknown or uncertain, forensic pathologists employ techniques such as DNA analysis and dental record comparisons to assist in identification.

Thereafter, pathology fellows obtain board certification in forensic pathology via examinations administered by ABP.

Continuing education and professional development are integral aspects of a forensic pathologist’s career. Forensic pathologists are expected to engage in ongoing learning activities to stay updated on advances in the field, maintain their licenses, and fulfill continuing medical education requirements. Practical experience gained through conducting autopsies, analyzing evidence, providing expert testimony in court, and collaborating with multidisciplinary teams further enhances their acumen.

Medicolegal Death Investigators

Medicolegal death investigators are frequently the first to examine death scenes, collect information and evidence, and liaise with families and law enforcement to support investigative processes. They assist medical examiners and coroners by documenting the scene of a death, gathering the decedent’s medical history, interviewing witnesses and family members, photographing the body, and managing the proper handling of the body before autopsy. By providing a detailed report of their findings, medicolegal death investigators help coroners and medical examiners understand the context and circumstances surrounding a death.

Beyond initial scene investigation, medicolegal death investigators assist in maintaining the chain of custody for evidence and ensuring that all documentation is complete and accurate. Forensic pathologists often rely on the information gathered by medicolegal death investigators to interpret medical and physical findings during autopsies (NIJ, 2024a).

There are no formal degree programs for medicolegal death investigators. Training programs are available,3 and investigators may elect to obtain professional certification.4 The Office of Justice Programs of the U.S. Department of Justice publishes a guide for death scene investigators (NIJ, 2024a). The guide, now in its third edition, presents current information about issues relevant to the profession, including job details and functions, with the aim of guiding medicolegal death investigators in their workflows (NIJ, 2024a).

STANDARDS IN MEDICOLEGAL DEATH INVESTIGATIONS

Standards for medicolegal death investigations are typically driven by systems of accreditation and certification, whereby independent examiners

___________________

3 E.g., the Death Investigation Training Academy.

4 E.g., from the American Board of Medicolegal Death Investigators or other certifying organizations.

and auditors test and audit performance, policies, and procedures of practitioners and facilities (NRC, 2009, p. 194). Accreditation does not mean that an accredited facility does not make mistakes or utilize best practices in every case. Instead, it means that a facility “adheres to an established set of standards of quality and relies on acceptable practices within these requirements” (NRC, 2009, p. 195). An accredited laboratory, for example, must have a management system for its operations, with monitoring and response methods in place (NRC, 2009, p. 195).

Organizations such as the National Association of Medical Examiners (NAME), the American Academy of Forensic Sciences, the International Association of Coroners & Medical Examiners (IACME), and the American Board of Medicolegal Death Investigators (ABMDI) promote the professional development of MLDI professionals through education and certification and improvements in the MLDI system through accreditation and the promulgation of standards. These organizations do not routinely monitor adherence to standards or have power to enforce standards.

NAME develops and promulgates forensic autopsy standards and “serves as a resource to individuals and jurisdictions seeking to improve medicolegal death investigation by . . . working to develop and upgrade national standards for death investigation” which are published to “provide a model for jurisdictions seeking to improve death investigation” (NAME, n.d.-a). NAME also “offers a voluntary inspection and accreditation program for medicolegal death investigative offices” (NAME, n.d.-b). Its inspection and accreditation checklist covers topics such as facilities, policies, staffing, operating procedures, reporting, and record-keeping, as well as morgue operations, autopsies, histology, and toxicology (NAME, 2024).

As of March 13, 2025, there were 77 NAME-accredited coroner and medical examiner offices. The cost of NAME accreditation varies. “Offices serving less than 2 million in population will pay $5,000 the first year and $2,500/year for the next three” years, while “offices over 2 million in population will pay $8,500 the first year and $3,500/year for the next three” years (NAME, n.d.-b).

IACME offers training to enhance the professionalism and competence of MLDI offices. It offers accreditation, hosts an annual training symposium, and publishes position papers regarding medicolegal death investigations and investigators. Its “accreditation process provides coroner and medical examiner offices the opportunity to self-assess and, subsequently, have auditors to review applicable standards”; it “allows coroner and medical examiner offices to ensure they are conducting business practices and procedures in compliance with established standards” (IACME, n.d.).

Currently, 40 medical examiner and coroner offices have IACME accreditation, which represents only 17 percent of offices nationwide (Brooks,

2021).5 The cost of accreditation is based on population, with initial costs ranging from $2,000 to $4,000 (plus travel costs for two auditors to visit for an on-site inspection). Annual costs of maintaining accreditation range from $300 to $1,200. There may be additional upfront costs, especially in the first year, to bring a facility up to accreditation standards and ensure that all required policies are in place to pass an audit. In addition, an annual report must be submitted to IACME to certify that there have been no substantial changes.6

Challenges to accreditation include

- a lack of support from governing bodies for accreditation (which may stem from low budgets that cannot accommodate the cost of accreditation);

- lack of staff;

- lack of experience with medicolegal death investigations (which may be due to a lack of deaths—e.g., 99 offices reported no cases in 2018, and another 16 offices accepted none); and

- limited access to resources (including training).7

The accreditation of facilities is complemented by the certification of individuals (NRC, 2009, p. 208), as certification ensures the competency of individual examiners (NRC, 2009, p. 208). However, many individual practitioners (forensic pathologists, coroners, medicolegal death investigators) are not certified.

ABMDI offers general certification for medicolegal death investigators. Bethany Smith, executive director of ABMDI, stated that the certification program serves to

___________________

5 About 14 percent of coroner offices and about 29 percent of city, county, district, or regional medical examiner offices were accredited by either NAME or IACME. Fifty-two percent of state medical examiner offices were accredited (Brooks, 2021).

6 The IACME standard for in-custody death investigations is that “the agency shall have a written policy defining law enforcement related and in-custody deaths, their special investigative considerations, and case postmortem examination requirements.” Other relevant IACME standards include the following: “The agency shall conduct an independent investigation separate from law enforcement or other investigative entities (Required); The agency shall have a written policy requiring medicolegal death investigators to take scene photographs independent from other investigative agencies (Required); The chief/lead investigator shall be registered by the American Board of Medicolegal Death Investigators (ABMDI) or its Forensic Specialties Accreditation Board (FSAB)-accredited equivalent (Required); The majority of the medicolegal death investigators should be registered by the American Board of Medicolegal Death Investigators (ABMDI) or its Forensic Specialties Accreditation Board (FSAB)-accredited equivalent (Not Required); Board-certified forensic pathologists (American Board of Pathology [ABP]) shall perform/supervise forensic autopsies (Required)” (presentation to the committee, Kelly Keyes, President, IACME, June 17, 2024).

7 Keyes, 2024.

encourage adherence to high standards of professional and ethical conduct when conducting medicolegal death investigations, recognize qualified individuals who have voluntarily applied for basic and advanced levels of professional certification, and grant and issue certificates to individuals who have demonstrated their mastery of investigational techniques and who have successfully completed rigorous examination of their knowledge and skills in the field of medicolegal death investigation.8

Certification levels include Registry Certification9 for entry-level investigators and Board Certification for experienced professionals.10 Investigators must recertify every 5 years. Some states, such as New York and Michigan, mandate certification or training for medicolegal death investigators.

Government agencies, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the U.S. Department of Justice, and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), contribute to standards for medicolegal death investigations by funding forensic science research and developing guidelines for the practice of forensic science. NIST, through its Organization of Scientific Area Committees (OSAC), establishes consensus-based standards to advance forensic practices.11

___________________

8 Presentation to the committee, Bethany Smith, Executive Director, ABMDI, June 17, 2024.

9 Registry Certification requires that the investigator verify current employment “by a Medical Examiner/Coroner office with the job responsibility to independently conduct medicolegal death investigations, or supervise such investigations”; sign a code of ethics and conduct; and complete an examination with 240 multiple-choice questions. Exam topics include interagency communication, communication with families, scene response and documentation, body assessment and documentation, completing the investigation, and forensic and medical knowledge (Smith, 2024).

10 Board Certification requires an associate’s degree or higher; verification of current employment “by a Medical Examiner/Coroner office with the job responsibility to independently conduct medicolegal death investigations, or supervise such investigations”; at least 4,000 hours of experience; reaffirmation of a code of ethics and conduct; references from a forensic science specialist, law enforcement, and an administrator/supervisor; and completion of an examination with 240 multiple-choice questions (Smith, 2024).

11 Following the publication of the 2009 National Research Council report, NIST developed the OSAC to facilitate the creation and adoption of scientific standards in forensic science, promoting quality and consistency across disciplines. Relevant OSAC areas for medical examiners include forensic pathology, toxicology, death investigation, and forensic science standards. Information about OSAC is available at https://www.nist.gov/adlp/spo/organization-scientific-area-committees-forensic-science.

MEDICOLEGAL DEATH INVESTIGATIONS: AN UNEVEN LANDSCAPE

In the United States, the workload, expertise, and resources of medical examiner and coroner systems vary by region. These systems typically function independently, prompting significant differences in death investigation practices and standards. In the absence of a centralized national system, system type, resource allocation, and standard-setting are the responsibility of state and local governments (see Box 2-2). There is, however, no mechanism to ensure that, once established, standards for medicolegal death investigations are followed.

Most MLDI systems are chronically underfunded. Rural areas are particularly under resourced. Moreover, a lack of access to top-of-the-line facilities, training, and staffing limits the ability of practitioners to meet accreditation standards and perform investigations (NIJ, 2019).

Just as troubling, as mentioned previously, is that demand for forensic pathologists significantly exceeds the supply nationwide. The shortage of board-certified forensic pathologists has significantly impeded medicolegal death investigations, with many offices unable to recruit or retain qualified personnel (see Box 2-3). According to a 2019 report from the National Institute of Justice (2019), an analysis of data through 2017 suggested that currently there are “only 400-500 physicians who practice forensic pathology full time, which is less than half of the total estimated need for 1,100-1,200 forensic pathologists in the United States” (pp. 72–73). More recently, J. Keith Pinckard, immediate past president of NAME, estimated that “there are about 800 certified forensic pathologists working full time, and it’s estimated that at least twice as many are needed to serve the entire country” (Lewis, 2024). Pinckard stated that “not enough doctors are choosing this specialty” for reasons that “are multifactorial but largely economic. . . . Jobs tend to be in the government sector and as physicians, they are not paid as well as what they could earn in other specialties in hospital or private practice” (Lewis, 2024).

According to the College of American Pathologists (CAP, n.d.), an average of 37 new forensic pathologists have been certified yearly over the last 10 years. Surveys of newly trained forensic pathologists indicate that retention rates are low, with only 21 full-time forensic pathologists remaining in the field per year (a number too small to replace those leaving) (CAP, n.d.).

In 2024–2025, there were 51 U.S. forensic pathology programs accredited by the ACGME, with 60 resident fellows (McCloskey and Riyad, 2025). Program graduates often prefer to work in metropolitan areas where they trained, and this may lead to a concentration of professionals in more populated regions. Forensic pathologists in less populous areas may experience professional isolation, lacking peers and colleagues for support

BOX 2-2

Death Investigation in Nebraska and Alabama: Case Studies

Presenters to the committee included a forensic pathologist from Nebraska and a coroner from Alabama. These individuals described norms and challenges in their respective states, demonstrating the heterogeneity in medicolegal death investigation systems.

Nebraska

Nebraska employs a county-based coroner system in which an elected county attorney serves as the ex officio coroner. There are 93 counties in Nebraska, and in the last election cycle, 30 county attorneys were elected.

Coroner duties may be delegated to the county sheriff, deputy county sheriff, or another peace officer (Nebraska Revised Stat. § 23-1210, 2024). Each county is responsible for the cost of autopsy services (including transportation to an autopsy facility).

Each coroner or deputy coroner is required to complete initial death investigation training within 1 year of election/appointment. There is wide variation in knowledge, training, experience, and autopsy referral practices.

All death investigations are performed by law enforcement. There are no medicolegal death investigators and no central repository of data resources.a

As of July 1, 2024, the estimated population of Nebraska was 2,005,465. The Douglas County morgue in Omaha is the state’s only public autopsy facility (U.S. Census Bureau, 2024c). Under the Nebraska system, 87 percent of unattended deaths (when an individual dies alone and their body is not discovered for a period of time) are not autopsied (Herbers and Turley, 2025). The state ranks in the bottom half nationally, with 30 states and the District of Columbia having higher unattended death autopsy rates (Herbers and Turley, 2025).

and collaboration, with limited opportunities to conduct forensic death investigations (including autopsies)—factors that make these positions less attractive.

Medicolegal Death Investigation Facilities, Employees, and Caseloads

In 2018, the most recent year for which data are publicly available, there were more than 2,000 medical examiner and coroner offices in the United States, with 1,630 coroner offices; 384 city, county, district, and regional medical examiner offices; and 22 state medical examiner offices. Despite their higher number, coroner offices served only 34.3 percent of the total U.S. population. City, county, district, and regional medical examiner offices covered 44.5 percent of the U.S. population, and state medical examiner offices covered 21.2 percent. Of the 10,930 full-time equivalent

Alabama

Alabama employs an elected coroner system. Coroners in Alabama must be at least 25 years old and a high school graduate, and live in the county of service. In addition, a coroner must not be a felon and must be registered to vote. Coroners are typically elected with no medical or forensic knowledge, although about 50 percent of the coroners now have some medical knowledge (e.g., from service as a nurse or paramedic) or some type of medical background.

Elected coroners are funded by the counties they serve. An ongoing Alabama study found that the average coroner’s office receives less than 0.1 percent of their county’s yearly budget. In one county with about 40,000 residents, 0.003 percent of the county’s budget is allocated for the performance of death investigations.

Offices often do not have funding for the basic tools needed to perform death investigations. “They don’t have cameras; they do not have morgues. Some counties do not have body bags. They don’t have disposables, an office, a phone, a vehicle, or even a computer. They’re running everything on their private phone,” stated Cilina Evans, Shelby County Coroner. In counties where the population is less than 50,000 (i.e., half the counties in Alabama), the coroner often has another full-time job because of the low coroner salary.

“Low pay and the lack of office support makes the job unappealing to more qualified candidates. In some cases, and in Alabama about 30 percent [of the time], the coroner’s position is held by a funeral director, which is a conflict of interest to me,” Evans said. Support staff often work with no pay, she continued, and this “leads to poor death investigations or death investigations not even being performed, particularly the scene investigations.” b

__________________

a Presentation to the committee, Erin Linde, Forensic Pathologist, Omaha, Nebraska, February 4, 2025.

b Presentation to the committee, Cilina Evans, Coroner, Shelby County, Alabama, September 19, 2024.

(FTE) personnel working in medical examiner and coroner offices that year, 890 were forensic pathologists. By comparison, 2,210 FTE personnel were nonphysician coroners, 97 percent of whom worked in coroner offices; 4,120 FTE personnel were medicolegal death investigators, who were the most common type of FTE employee (38 percent). In 2018, medical examiner and coroner offices received 1.3 million death referrals and initiated in-depth investigations in 605,000 cases, accepting an average of 80 cases per FTE autopsy pathologist, nonphysician coroner, death investigator, and forensic toxicologist. On average, these offices conducted 1 full autopsy for every 7 cases referred and every 3 cases accepted (Brooks, 2021, p. 4).12

___________________

12 Almost three-quarters (74 percent) of forensic pathologists worked in medical examiner offices, and more than three-quarters (78 percent) were serving jurisdictions with populations of 250,000 or more (Brooks, 2021). NAME (2020) forensic autopsy performance standards state that a “forensic pathologist shall not perform more than 325 autopsies in a year” and “recommend that no more than 250 autopsies be performed per year” (p. 10).

BOX 2-3

Medical Examiners in New York City

As of the writing of this report, New York City had 18 medical examiners, a little more than half the number of staff in 2021. Because of low staffing, the city “has stopped doing autopsies at the city medical examiner’s office in Queens and has consolidated those services in Brooklyn and Manhattan” (Lewis, 2024). In response to the shortage, city medical examiners have stopped doing autopsies on suspected drug overdoses. And, Lewis (2024) reported, “as more of their peers leave, substitutes have to testify in the criminal cases they left behind—a practice known as ‘surrogate testimony’ that is under growing scrutiny in the courts.”

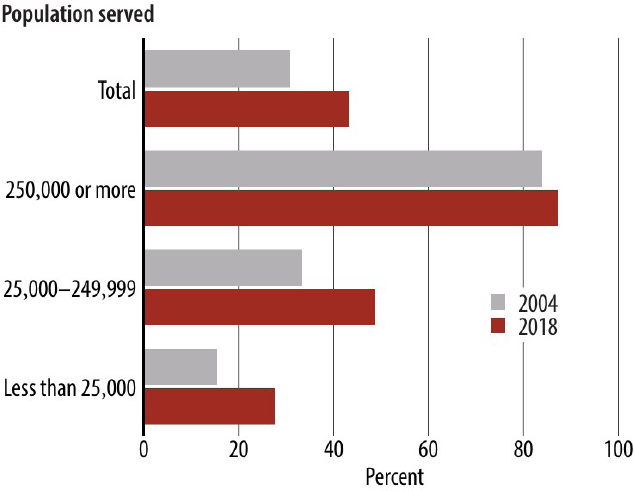

The average medical examiner and coroner office budget in 2018 was $775,000 (Brooks, 2021). The cost of autopsies ranges from $4,000 to $8,000.13 That same year, however, only about 43 percent of medical examiner and coroner offices had a computerized information management system, and only three-quarters of medical examiner and coroner offices had access to the internet separately from a personal device (Brooks, 2021, p. 9). See Figure 2-2 for the percentages of medical examiner and coroner offices with a computerized information management system in 2004 and 2018.

THE ROLE OF CORONERS, MEDICAL EXAMINERS, AND FORENSIC PATHOLOGISTS IN PUBLIC HEALTH

While the focus of work by those conducting medicolegal death investigations has traditionally been to serve the criminal justice system, in recent decades, their role has evolved to encompass work that serves the interests of public safety, medicine, and public health (see Box 2-4).

Information gathered by medical examiners and coroners provides crucial data for national mortality statistics, especially on unnatural and sudden deaths and unexpected natural deaths. Information on cause and manner of death is recorded on death certificates. These data are then reported to state health departments and, through the National Vital Statistics

___________________

13 A 2011 FRONTLINE investigation, Post-Mortem: Death Investigation in America, found that “autopsies are not covered under Medicare, Medicaid or most insurance plans, though some hospitals—teaching hospitals in particular—do not charge for autopsies of individuals who passed away in the facility. A private autopsy by an outside expert can cost between $3,000 and $5,000. In some cases, there may be an additional charge for the transportation of the body to and from the autopsy facility” (PBS, 2011).

Committee members Roger Mitchell Jr. and Jonathan Lucas, who are medical examiners, estimate the current cost range for an autopsy to be $4,000–$8,000 (as of July 2025).

SOURCE: Brooks, 2021. As a work of the U.S. federal government, the image is in the public domain.

BOX 2-4

Identifying Trends in Causes of Death

“Medical examiners and coroners are often the first to see trends in traumatic deaths as well as the other causes of death. Data generated during investigations can be used to confirm hunches and provide evidence needed to inspire change. For instance, the decrease in the motor vehicle traffic death rate, which has been reported as one of the greatest public health achievements of the 20th century, was driven in part by information provided by medical examiners and coroners. In 1979, while Susan Baker was working as an autopsy technician, she had a hunch that infants had higher death rates in crashes than older children. In her own words,

‘[Using death certificate data from the National Center for Health Statistics] it took me about 10 minutes to discover that my hunch had been correct. I remember my excitement, and it turned out that my simple analysis had far-reaching results.’

She published her findings in a short paper that was widely read, and eventually laws were enacted requiring the use of infant car seats.”

SOURCE: Excerpted from Warner, Braun, and Brown, 2017, p. xiv.

System, aggregated by the National Center for Health Statistics. This comprehensive dataset serves as an invaluable resource for analyzing mortality trends and population health. It also provides important metrics on life expectancy and on how causes of death evolve over time (Warner, Braun, and Brown, 2017).

Forensic pathologists play a crucial role as partners to public health officials in the identification of causes and patterns in deaths. Because they perform most of the autopsies carried out in the United States, their work provides valuable disease and cause-of-death information. For example, they collect specimens during autopsies that provide important data for public health studies and report notifiable diseases (diseases that are required by law to be reported to public health authorities14) to health departments and surveillance programs. They identify and confirm that unusual deaths were caused by infectious agents that might signal an outbreak, providing public health authorities with information to act quickly to control their spread.

By investigating deaths related to workplace exposures or environmental factors, such as toxic chemicals or pollution, forensic pathologists highlight potential risks to health and safety. This information informs regulations to improve safety standards and reduce exposure.

Forensic pathologists also document drug-related deaths, providing data crucial for tracking substance abuse trends, such as opioid or synthetic drug epidemics. The evidence provides support to efforts aimed at combating substance abuse through education, regulation, and treatment programs. Forensic pathologists can be the first to identify unusual patterns of death that could indicate bioterrorism or mass poisoning, enabling rapid response to protect communities. In this way, they serve as a critical link between individual death investigations and the broader public health system.

For example, during the opioid crisis, forensic pathologists were at the forefront of identifying drug trends, such as the rise in fentanyl-related deaths. Their investigations provided insight into the types of substances involved in overdoses, helping public health authorities respond more effectively and tailor prevention strategies.15

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the important role that forensic pathologists play in public health. Forensic pathologists often determined cause of death in cases related to COVID-19. Through autopsies, analysis of medical records, and examination of forensic evidence, they determined whether COVID-19 was the primary cause of death or whether other contributing factors were involved. By reporting COVID-19-related deaths,

___________________

14 Notifiable diseases include sexually transmitted infections, viral diseases, and bacterial infections.

15 Presentation to the committee, Margaret Warner, Senior Epidemiologist, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, June 17, 2024.

forensic pathologists provided essential data to help public health officials to monitor the spread of the virus, identify viral hotspots, and implement public health interventions aimed at controlling the pandemic. By investigating clusters of deaths and determining their linkages to specific locations or events, they facilitated the implementation of targeted control measures to contain the spread of the virus and prevent further transmission.16

THE ROLE OF MLDI SYSTEMS IN THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM

Coroners, medical examiners, forensic pathologists, and others who investigate deaths often testify as expert witnesses in legal proceedings, including criminal trials, to present findings and conclusions regarding the cause and manner of death. When called upon as expert witnesses in court proceedings, those conducting medicolegal death investigations are tasked with explaining their findings, interpretations, and conclusions to judges and juries, helping them understand complex medical and scientific information about the case. Their testimony often exerts significant influence on the outcome of a trial or other legal proceeding.

Those investigating medicolegal deaths provide evidence based on their findings from autopsies, medical records, test results, and analysis of physical evidence collected from the scene of death. This evidence can help corroborate or refute other evidence in the case, provide insights into the circumstances surrounding the death, and support the prosecution or defense in legal proceedings (see Box 2-5).

___________________

16 In mass casualty events, forensic pathologists play a crucial role in victim identification, determining cause and manner of death, and assisting in legal and investigative processes.

BOX 2-5

The Importance of Scientifically Based Assessments of Cause and Manner of Death: George Floyd

The death of George Floyd is perhaps the most well-known recent example of a death in custody. The resulting legal proceedings vividly highlighted the important role medical examiners play in determining culpability and the importance of accurate science-based assessments of cause- and manner-of-death determinations.

On May 25, 2020, Floyd died during an encounter with Minneapolis police. Officer Derek Chauvin knelt on Floyd’s neck for over 9 minutes. The official autopsy report by the Hennepin County Medical Examiner ruled Floyd’s death a homicide, citing “cardiopulmonary arrest complicating law enforcement subdual, restraint, and neck compression” (Hennepin County Medical Examiner’s Office, 2020). The findings indicated that, while underlying health conditions and drug use were present, the primary cause of death was the result of actions by law enforcement officers. This was critical at Chauvin’s trial, as several forensic pathology experts presented evidence that supported the finding that neck compression was the primary cause of Floyd’s death (Chen, 2021). To rebut this assertion, the defense called David Fowler, a former chief medical examiner in Maryland, who testified that, in his opinion, Floyd’s death was caused by a combination of factors, including preexisting heart conditions and drug use, rather than asphyxiation due to Chauvin’s restraint (Florido, 2021). Fowler’s conclusions “sparked immediate concern among hundreds of his peers around the country, who suggested he might be motivated by racial or pro-law enforcement bias” rather than scientifically sound evidence (Romo, 2022). These concerns led to an independent audit by Maryland’s Office of the Attorney General of determinations of manner of death in restraint cases during Fowler’s tenure (see Chapter 5). While Chauvin was ultimately convicted of second-degree unintentional murder, third-degree murder, and second-degree manslaughter, the case sparked discussions about the scientific validity of the findings of medical examiners and the influence of external pressures on their determinations of cause and manner of death.

CONCLUSIONS

Conclusion 2-1: The quality of the death investigations in the United States is uneven because of variations in the level of resources (funding, staff, and infrastructure), credentialing, and enforceable standards.

Conclusion 2-2: There is a serious shortage of forensic pathologists to conduct medicolegal death investigations, and many jurisdictions lack qualified medical examiners and coroners or the physical infrastructure necessary to support their work. In very small jurisdictions in particular, limited resources and a limited pipeline of medical residents pursuing forensic pathology specialties pose a significant barrier to rigorous and accurate medicolegal death investigations.

Conclusion 2-3: Efforts have been made to establish standards of practice for medicolegal death investigations. Limited funds are available to train staff to meet standards.

Conclusion 2-4: Insufficient personnel and resources can result in incomplete death investigations, investigations not being conducted, incomplete evidence collection, incorrect conclusions, mistaken diagnoses, or misleading and unobtainable death statistics.

This page intentionally left blank.