Flood Forecasting for Transportation Resilience: A Guide (2024)

Chapter: 3 Prepare and Monitor

CHAPTER 3

Prepare and Monitor

Key Focus

Establishing workflows to anticipate flood impacts from forecasted events.

Key Takeaways

- Identifying priority assets, such as scour-critical bridges, and corresponding critical impact thresholds is essential to establishing monitoring protocols.

- Sensors provide key data inputs for establishing flood forecasts in real time.

- Standard operating procedures are useful tools to define monitoring timeframes, thresholds, and roles of key personnel.

- Partnerships can increase monitoring capacity.

- Services from federal agencies, such as the NWS and USGS, offer forecast and monitoring support.

- State and local public agencies may also offer on-site monitoring support.

Actions to Accomplish

- Identify who will monitor flood forecasts for which DOT assets.

- When preparing a monitoring plan, establish roles and communication channels between the state DOT and district/regional offices.

- Determine a timeline for the monitoring that is to be done before an event.

3.1 Overview

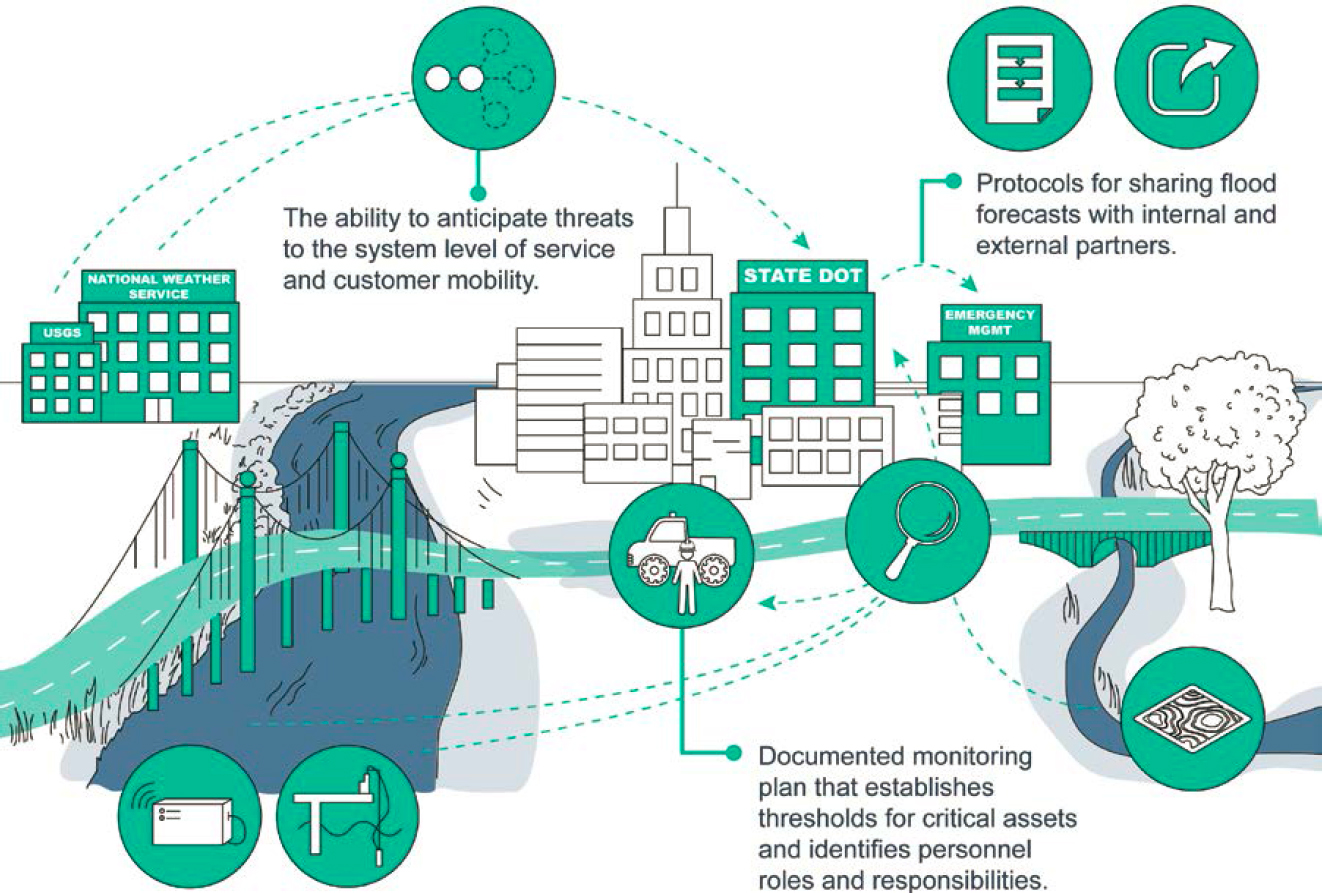

“Prepare and monitor” refers to the established DOT protocols and partnerships that lead to proactive flood event management. Figure 3-1 highlights mature flood preparation and monitoring capabilities.

3.2 Introduction

DOTs often rely on historical knowledge of flooding impacts and reported conditions in the field to prepare for flooding events. In a nationwide survey of state DOTs (Park et al. 2021), 38% of participants reported that their state DOT did not perform flood prediction modeling. Monitoring protocols help establish a more proactive approach to flood event management. This chapter will focus primarily on the steps taken before a flooding event. Response during a flooding event is covered in Chapter 4: Operations.

How do you want to enhance your flood monitoring workflows and capabilities? Key information in this chapter:

- For key questions to ask when developing a monitoring plan, see the Developing a Monitoring Plan section.

- For information on sensors, see Table 3-3.

- To identify opportunities for coordination and questions to ask when onboarding a monitoring team, see the Partnerships in Practice section.

This chapter presents key questions for DOTs to consider when documenting workflows for anticipating flood impacts and draws from case studies and examples of existing DOT practices for monitoring and preparing for flooding events. DOTs that want to start flood forecasting will find information to begin building a monitoring plan and identify key personnel to engage. DOTs that already flood forecast and want to enhance their capabilities will find effective practices that leverage data sources or tools they may be using.

A mature flood monitoring capability will include:

- The ability to anticipate threats to system level of service and customer mobility,

- A documented monitoring plan that establishes thresholds for critical assets and identifies personnel roles and responsibilities, and

- Protocols for sharing flood forecasts with internal and external partners.

This chapter is organized into the following sections to cover how DOTs may start or expand their monitoring capabilities:

- Developing a Monitoring Plan. Provides key questions to build or enhance a flood risk monitoring plan and examples of key features to enhance monitoring efficiency.

- Leveraging Real-Time Data. Describes data types available that may support a DOT’s efforts to build out real-time road network monitoring, including sensors, and options to manage data from multiple sources.

- Partnerships in Practice. Identifies opportunities for coordination within a DOT and with external partners to monitor flooding events.

TIPS AND TOOLS

TIPS AND TOOLS

See the Activity for Building a Monitoring Plan in Appendix B to work through the chapter questions in more detail.

3.3 Developing a Monitoring Plan

Monitoring plans detail protocols for the types of information and frequency at which it should be collected when preparing for a flooding event. Such plans also describe what tools should be leveraged in the process. A documented monitoring protocol can support the transfer of knowledge and employee onboarding, as well as communicating processes with partners to leverage resources—both within the DOT and externally. The foundational questions in Table 3-1 can be used to guide the development of a monitoring plan. DOTs can also use these questions to evaluate existing monitoring plans for completeness and identify opportunities for improvement.

Table 3-1. Foundational questions to guide the development or completion of a monitoring plan.

| What are our priority assets for monitoring? | Priorities can be established using different metrics, such as the magnitude of damages, traffic volume, route redundancy, scour-critical bridges, and frequency of flooding. |

| What baseline data exist? What additional data sources are needed? | As outlined in Chapter 2, it is important to establish baseline data, such as typical high water levels and water rise rates seen at locations of interest. Then, take stock of what additional data sources are needed. |

| What are the flood threshold elevations for priority assets? | Critical asset structural information, such as scour critical, can be compared to forecasted water level conditions to determine when flood waters are likely to affect asset operations. |

| At what frequency should monitoring occur? | Monitoring frequency can be based on hours, days, or weeks, with frequency increasing based on increasing severity of conditions. |

| What tools are used to monitor when and where it will flood? | This procedure can include desktop monitoring leveraging national, state, and local data sources as well as field equipment to monitor real-time conditions at specific asset locations. |

| What are our expected staffing needs? | Staff will be required to monitor priority assets. This can include a centralized approach or a decentralized approach, where monitoring responsibility is more heavily placed on the state or regions/districts of the DOT. Key personnel may include hydraulics and hydrology, emergency management, and maintenance staff. |

| Whom do we need to contact? | Staff should have established points of contact at the DOT region/district or state to report observed conditions. Automated messaging can also be used to issue alerts when predicted or observed conditions exceed critical threshold elevations. |

Monitoring Plans in Practice: Minnesota DOT Bridge Flood Response Plans

Monitoring Plans in Practice: Minnesota DOT Bridge Flood Response Plans

The Minnesota DOT (MnDOT) Bridge Office has developed bridge monitoring recommendations based on asset priority. All scour-critical bridges have Plans of Action (POAs) that contain details on monitoring the specific bridge site. The following actions are recommended as general guidelines for bridges without a POA:

- Districts are responsible for determining which bridges will be monitored.

- The district must be prepared to monitor water surface elevations when flooding occurs after rainfall or snowmelt.

- The district should conduct a pre-flood site investigation on high monitoring priority bridges that includes measuring baseline river-bed elevations, marking and surveying a reference point to measure the water surface elevation, and marking the water surface elevation at which monitoring should begin.

- All critical piers and abutments should be monitored to determine changes in the channel bottom elevation. If the bed has lowered significantly, monitor it at a minimum of twice per day and contact the District Scour Coordinator or Bridge Office Flood Coordinator.

- Close the bridge if scour threatens the bridge’s stability.

Uncertainty: How Do DOTs Measure or Assess Uncertainty?

One of the most challenging elements of beginning and operating a flood forecasting system is being able to answer the question: “How sure are you?” Clear communication about what forecasts mean and their limitations is essential to building organizational confidence. DOTs use a variety of sources to measure uncertainty, including:

- Evaluating Probabilities. Quantifying the likelihood of the flood event occurring. In the project survey of state DOTs, 50% of respondents reported evaluating probabilities as their method to account for and communicate uncertainty when taking action for specific assets.

- False Alarm Rates. Tracking in real time what happened, along with a history of the prediction.

- Confusion Matrix. Classifying events to compare when observations align with the forecast (true positive); when the prediction showed an event, but the event did not happen (false positive); and when a prediction did not show an event, but an event occurred (false negative). This can be used as a tool to understand quality.

- Tool Assessment Reviews. Conducting an independent review of flood prediction models in terms of accuracy, applicability, timeliness, and usability (Park et al. 2021).

As part of this research effort, a confusion matrix was used to assess the performance of the National Water Model (NWM) stream discharge forecasts,

The Challenge of Heavy Rainfall

Impacts caused by high-intensity or long-duration rainfall, also known as pluvial hazards, have historically been insufficiently assessed. Pooling and ponding caused by such hazards can significantly impair transportation system level of service. More research is needed to develop forecasting capabilities for these kinds of hazards. Identifying thresholds can be particularly challenging given the dependencies that event severity has on rainfall characteristics, antecedent conditions, stormwater infrastructure capacity, and state of repair.

which had a resulting global 73% true positive rate for discharge spikes from medium-range forecasts. The research team established a threshold of 2 cubic meters per second to weed out smaller bumps in a forecast. An additional filter was added to account for unusually high flow for a specific stream. For example, it is more typical for a small stream to double in size than a large river. These predictions were only included if they occurred more than 16 hours before an event.

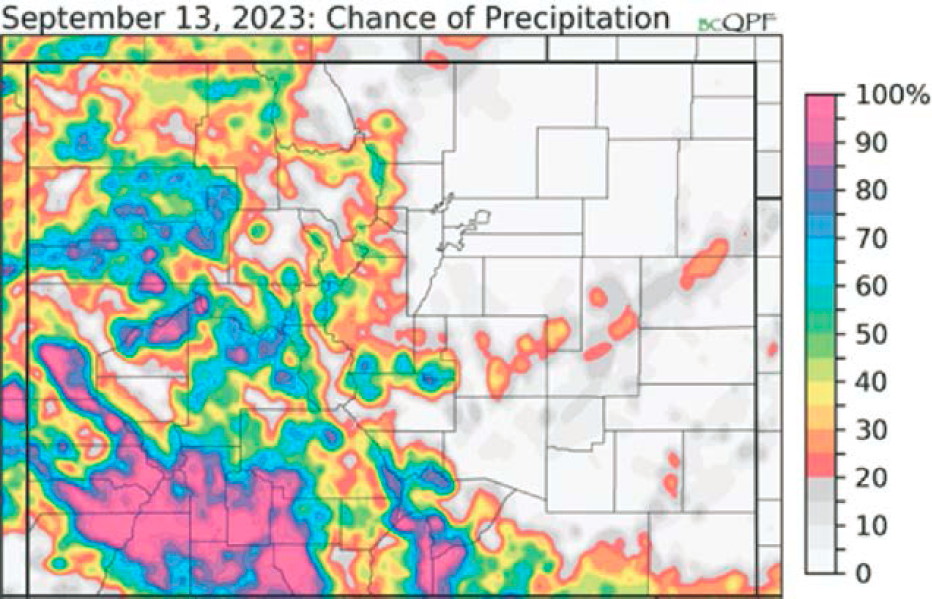

Visualizing projected flood impacts can also play an important role in communicating uncertainty. Displaying potential impacts in terms of event likelihood can help DOTs direct resources to monitor areas with higher risk. The Colorado Water Conservation Board issues a Flood Threat Bulletin that provides an overview of the potential flood threat facing the state of Colorado. The bulletin is issued regularly from May 1st through September 30th. A precipitation map is included, displaying the quantitative precipitation forecasts (QPFs) in terms of the chance of precipitation, as shown in Figure 3-2 (Colorado Water Conservation Board 2023). An additional product, a Flood Threat Outlook, is produced twice weekly and provides an overview of the flood threat and precipitation amount/probabilities in the state over the following 15 days.

While this type of quantitative display can be helpful for technical staff, it is important to also consider how risk and uncertainty can be communicated to different audiences. The Flood Threat Bulletin presents flood threat information in qualitative terms using the following definitions for each threat level:

- None: less than 10% expected probability of flooding within a given county

- Low: 10%–30%

- Moderate: 30%–60%

- High: greater than 60%

- High impact: greater than 60% and a severe threat to life and property.

These threat levels are based on several factors, including the magnitude and duration of the expected event. These qualitative categories account for a margin of error in the precipitation

Figure 3-2. Example chance of precipitation map from the Colorado Flood Threat Bulletin.

estimates while providing a quick summary of flood threats that can support DOT personnel and the public in identifying elevated flood threats.

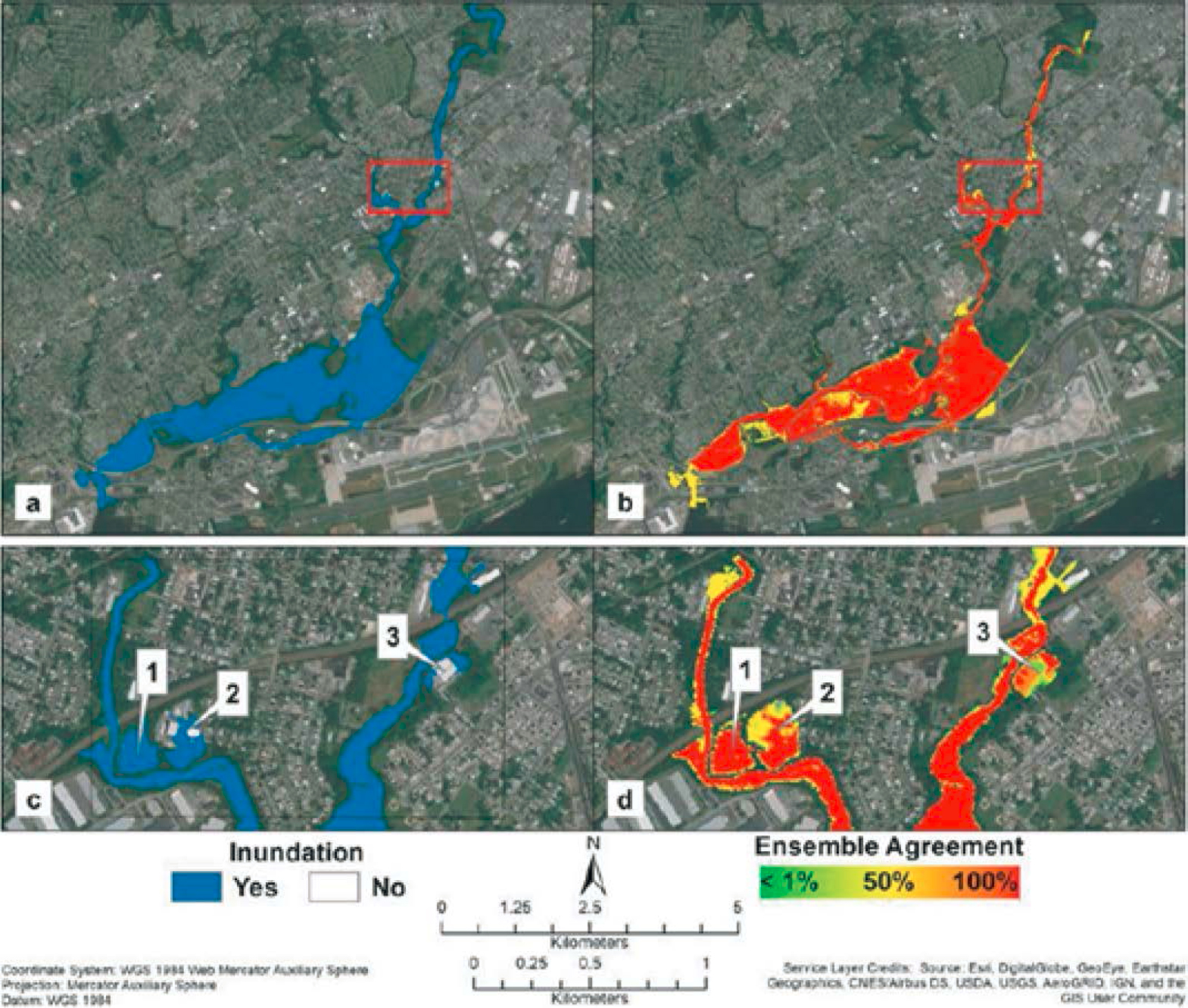

A flood forecasting team can assess uncertainty based on the level of agreement between multiple forecasts or hydraulic models. A study published in the Journal of the American Water Resources Association, “A Hydraulic MultiModel Ensemble Framework for Visualizing Flood Inundation Uncertainty,” developed an interactive web-based visualization of flood inundation (Zarzar et al. 2018). Uncertainty is classified based on model ensemble agreement, meaning that areas with high model agreement have higher confidence and higher flood risk than areas with low model agreement, as shown in Figure 3-3. While this ensemble hydraulic modeling approach is intensive, it illustrates an innovative way to visualize uncertainty and support focusing resources where the flood risk is greatest (Zarzar et al. 2018).

TIPS AND TOOLS

TIPS AND TOOLS

Data accuracy and completeness are significant challenges in implementing a flood monitoring system. To build certainty, improve factors such as coverage, accuracy, format, and timeliness (Park et al. 2021).

Tips for Building Confidence in Flood Forecasts Needed to Integrate External Partners

Through conversations during this research, DOTs mentioned various ways they might approach building confidence.

- Virginia DOT wanted to start with a best guess of an asset elevation and trigger information and update through field validations over time. The strategy would include noting a place, such as “this data is a best guess of this elevation and comes from [an example data source].”

- The DOTs of Colorado, Minnesota, and California (Caltrans) mentioned the potential value in picking locations with existing information, such as gauges, to see how the forecasting utility works along with a mix of areas with unknowns or “problems.”

- Missouri DOT was interested in a false alarm rate to track real time what happened along with a history of what the prediction said. Similarly, the North Carolina DOT and Caltrans recommended a “look-back” feature to compare a prediction with observations.

- Caltrans recommended thinking about spreading across geographic features, such as flash flood areas, mountain, and coastal areas, to build model confidence in those places.

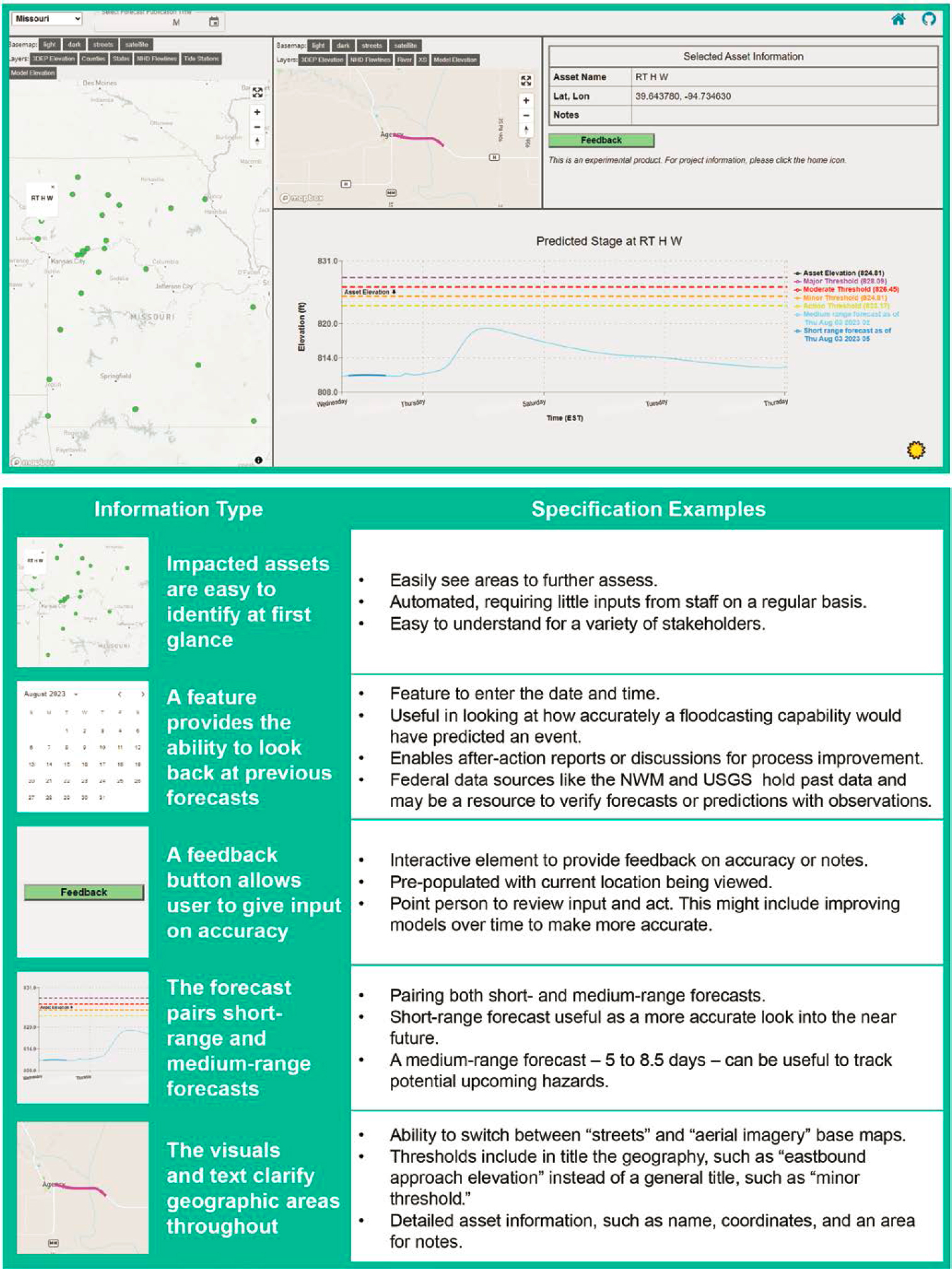

Monitoring Interface Elements

Data presentation interfaces can streamline a proactive monitoring approach by supporting the quick identification of assets with potential flood impact. To inform the development of this guide, the research team created a dashboard to demonstrate the potential functionality, use cases, and operational utility that a flood forecast capability would offer at locations of interest for participating DOTs. The demonstration dashboard used the NWM, research team-derived, or DOT-supplied rating curves and estimates of asset impact thresholds to forecast impacts at locations of interest provided by the 10 DOTs participating. The platform enabled the engagement with DOT participants to move beyond hypothetical questions (such as “How would you use flood forecast information?”) to more practical application insights. Participating DOT partners were better able to discuss the operational possibilities and challenges having such a capability would pose.

Using the demonstration dashboard, DOTs identified key features that would support their monitoring efforts, as shown in Figure 3-4.

Interface Maintenance

Maintenance is important to take into consideration when assessing the level of effort needed to operate a flood monitoring interface. This maintenance can include troubleshooting system errors and routine checks to ensure proper interface function. Some commercial options may offer interface maintenance as part of the service provided. The following key questions can assist DOTs in developing a maintenance plan for a flood monitoring interface:

- Will interface maintenance be conducted internally or by an external partner?

- Who will be the designated point of contact for reporting issues encountered in the monitoring interface?

- How will issues encountered be recorded and tracked?

- What end-users need to be notified if the monitoring system is not functioning properly?

- How often will routine maintenance checks be performed on the monitoring interface?

3.4 Leveraging Real-Time Data

Real-time data can support predictive flood hazard modeling efforts and provide actionable information in the moment. Data types available include broad-scale weather reporting and forecasting, video feeds of critical network nodes, and sensors monitoring water-body or road surface conditions. DOTs can leverage existing data sources across various data types to develop monitoring plans and supplement them with additional video or sensor networks to increase monitoring specificity. Table 3-2 and Table 3-3 summarize available data sources that may support DOTs’ efforts to build out real-time road network monitoring and future flood hazard forecasting.

Data Types

Real-time data can come from a variety of sources, such as those shown in Table 3-2.

The use of real-time data is already widespread for DOTs across a range of data types. Nearly all survey respondents indicated that they use some form of real-time data to monitor roadway conditions. Many survey respondents indicated that their teams already leverage water level and discharge data from USGS gauge services and, to a lesser extent, local or state gauge data. The DOTs of Ohio, North Carolina, California, Washington, Missouri, Minnesota, and Kansas indicated that they rely on closed-circuit television (CCTV) footage to monitor roadway conditions; however, none of these DOTs currently use CCTV footage to monitor roadways specifically for flooding or ponding. The California DOT (Caltrans) is the only one that reported using drones to monitor roadways; this method could benefit DOTs interested in monitoring roadway conditions at various locations that do not need continuous monitoring.

A survey administered for a previous NCHRP project reinforces this finding. Based on 43 DOT respondents, the three most reported instruments for flood monitoring were federal stream gauges (41 respondents), federal rain gauges (25 respondents), and nonfederal stream gauges (17 respondents) (Park et al. 2021).

For most DOTs, less than 10% of streams crossing roads are equipped with gauges.

Source: Park et al. (2021).

Table 3-2. Real-time data source types.

| Closed-circuit television (CCTV) | CCTV transmits video signals from a camera to a specific place or limited set of monitors. CCTV systems can be used to observe conditions at a site of interest from a distance, such as from an operations control room. |

| Radar | Radar uses radio waves to determine the distance, angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site transmitting the radio waves. Radar systems require equipment components to transmit and receive radio waves to calculate the radar system’s spatial relationship to other objects. |

| Ultrasonic | Ultrasonic systems use sound to detect the distance between the system and other objects. These systems transmit a high-frequency sound and capture the audio waves that reflect off other objects. The system uses the time between transmitting and receiving sound waves to calculate distance. |

| Sonar | Sonar systems use sound to detect the distance between the system and other objects. These systems are well suited to detecting distances underwater, generally use lower-frequency sounds than ultrasonic sensors, and have a larger detection range. The system uses the time between transmitting and receiving sound waves to calculate distance. |

Table 3-3. Real-time data sources to support flood monitoring.

| Data Category | Data Type | Type of Sensor | Spatial Coverage | Cost Types | Setup | Data Output Format | Dashboard URL | Notes and Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative/Descriptive: General | Weather forecast description | N/A | Local or regional | Qualitative data evaluation | N/A | Text, audio, video | https://www.weather.gov/ | Qualitative weather forecasts are often available for the upcoming week as well as for the morning, afternoon, and evening of the current day and the next day. These forecast reports can help DOT staff qualitatively identify periods of forecasted high precipitation with some amount of spatially specific information. |

| Qualitative/Descriptive: Specific Location | Closed-circuit television (CCTV) | Video | Local | Equipment capital cost and maintenance; data processing and management | May require gaining access to existing CCTV streams or setting up new ones | Video | N/A | Live video streams from CCTVs at crucial sites can provide data on the current site status, where flooding is occurring, and the qualitative severity of flooding. CCTV data may already exist and be available to use, or DOTs may install CCTVs at sites of concern. |

| Drone footage | Video | Local | Equipment capital cost and maintenance; data processing and management | Requires acquisition of drone and staff to operate | Video | N/A | The use of drone footage is similar to that of CCTV footage; however, drones are mobile and can survey stretches of road networks. Unlike CCTV footage, drones are not well suited to long-term site monitoring and are best used during periods of active flooding concern. | |

| Quantitative: Raster | Radar | Radar | National (with local detail available) | Data processing and management | Requires setup to utilize state-level relevant data | Image | https://radar.weather.gov/ | Radar data of storms and precipitation can supplement qualitative weather forecast reporting. Radar data can support preparedness for thunderstorms and other short -duration, high-intensity events with a higher temporal resolution than that usually provided in qualitative weather forecasting. |

| Quantitative: Point | USGS gauge services | Variable | National | Data processing and management | Requires setup to utilize state-level relevant data | Machine-readable data | https://waterdata.usgs.gov/nwis | Stream gauges can provide information on water levels, flow, and velocity. Not all gauges provide all types of data. USGS has an extensive existing network of gauges and also hosts data from state, local, and regional sources. USGS’s database of gauges is not comprehensive; state, local, and regional entities share varying amounts of data with USGS. Water level, flow, and velocity data from stream gauges can inform predictive flood models; data on water -body flood stages are likely necessary to estimate relationships between water levels and flood exposure for nearby roadways. |

| National Weather Service gauges | Variable | National | Data processing and management | Requires setup to utilize state-level relevant data | Machine-readable data | By weather forecasting office for precipitation; see https://www.weather.gov/phi/rainfall-monitoring as an example. See USGS gauge services for stream gauge data. | NWS hosts data for rain gauges and some stream gauges via the AHPS site. USGS manages the federal stream gauge network that AHPS references. Rain gauge data can provide information on potential or current pluvial flooding, as well as fluvial flooding in conjunction with stream gauge data. | |

| State stream gauge data | Variable | State | Equipment capital cost and maintenance; data processing and management | Requires setup to utilize state-level relevant data or potentially installing stream gauges | Machine-readable data | Varies by state | State-level stream gauge network data are likely very similar to USGS gauge data types and monitoring extents. However, some data that are not provided in USGS’s database may be available at the state level. Calibration between water level data and flood exposure for nearby roadways is necessary. | |

| Local stream gauge data | Variable | Local | Equipment capital cost and maintenance; data processing and management | Requires setup to utilize state-level relevant data or potentially installing stream gauges | Machine-readable data | Varies by locality | Local-level stream gauge network data are likely very similar to USGS gauge data types and monitoring extents. However, some data that are not provided in USGS’s database may be available at the local level. Private citizens or nonprofits may monitor water levels, and if data validation processes exist, these data may be usable in larger network modeling. Calibration between water level data and flood exposure for nearby roadways is necessary. |

| Watershed stream gauge data | Variable | Watershed | Equipment capital cost and maintenance; data processing and management | Requires setup to utilize statelevel relevant data or potentially installing stream gauges | Machinereadable data | Varies; Delaware River Basin Commission example: https://webapps.usgs.gov/odrm/map/map.html | Watershed-level stream gauge network. Data are often managed by nonprofit watershed associations or interstate commissions (e.g., the Delaware River Basin Commission). Including stream gauge data from stations outside the state but within watersheds that overlap with state boundaries may improve flood modeling and forecasting. Like other stream gauge data, water level data do not directly predict flood exposure for nearby road networks. | |

| Roadway sensors | Sonar, ultrasonic | Local | Equipment capital cost and maintenance; data processing and management | Requires purchasing, installing, and operating sensors | Machinereadable data | N/A | Sensors monitoring roadways for flooding often rely on ultrasonic data. Unlike CCTV data, sonic sensors can provide machinereadable data and estimate water depths. These monitors can require significant weatherproofing but can provide instant data on current roadway flooding at sites of concern. Low-cost sensors may be appropriate for monitoring pilots and can later be replaced with weatherproof systems. | |

| Polygons and Lines | NWS Flood Inundation Mapping (FIM) services | N/A | Currently select regional, later to be national | Data processing and management | No setup for loading live floodplain forecasts into GIS. Setup needed for automated triggers and communication (alerts, etc.). | Machinereadable data | Access the National Viewer and supporting documents at https://www.weather.gov/owp/operations | Floodplain forecasts derived from streamflow forecasts from NWM and River Forecast Center. Product first announced September 2023 and is experimental. Uses approximate heightabove- nearest-drainage (HAND) method. Currently covers 10% of U.S. population. Plans to cover 100% by 2026. |

Sources: National Weather Service (n.d.), U.S. Geological Survey (n.d.), Delaware River Basin Commission (2023). Note: N/A = not applicable.

Sensor Network Considerations

Expanding real-time monitoring with additional sensor-based data may be a valuable option for DOTs. However, in developing sensor networks, DOTs can consider several key questions prior to investing in additional equipment:

Data Types

- How frequently does the sensor collect data?

- How frequently does the sensor report data?

- What type of data is best suited to the DOT’s monitoring needs? (i.e., does water level matter more than flow or velocity?)

Installation, Operation, and Maintenance

- How is the sensor powered? (Does it require a battery, can it rely on solar power, or does it need to be wired into the electrical grid?)

- Where will the sensor be physically located? Is additional equipment required to install the sensor?

- What weather or other adverse conditions will the sensor be exposed to, and how will this affect sensor operation and maintenance requirements?

- How will the sensor transmit data? Does it rely on a mobile network connection, transmit radio-based data, or save data to an internal system that requires manual data retrieval?

Table 3-4. Two state systems for data management.

| Contrail Software, NCDOT | FAST, TxDOT |

|---|---|

| NCDOT uses Contrail, an internally facing proprietary software that allows system users to compile data from multiple gauge sources for analysis and evaluation. The software facilitates operational decisions, emergence operations, and flood early warning systems (OneRain n.d.). | TxDOT developed the Flood Assessment System (FAST), which is made up of six real-time map services. Three of these services come from National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and USGS, and three are internally generated. The underlying technical infrastructure that supports the FAST system is a set of software and data functions called Datasphere, maintained by the company KISTERS. The KISTERS model integration framework is designed to tackle a wide range of modeling tasks and operate on standardized procedures, ensuring reliability, reproducibility, and comparability of results (Bibok et al. 2023). |

Data Management

Aggregating real-time data across various data types and sources can improve monitoring resolution. However, managing data across types and sources can be challenging. At the national scale, the USGS National Water Information System (NWIS) is a data-sharing platform that supports the acquisition, processing, and long-term storage of water data and includes all historical USGS gauge records in the United States. In a survey administered for a previous NCHRP project, approximately half of state DOTs reported using NWIS for flood monitoring (Park et al. 2021). At the state level, Table 3-4 highlights existing systems from North Carolina DOT (NCDOT) and Texas DOT (TxDOT) that combine various systems to provide information at a higher spatial and temporal specificity that would not be possible with only one data source.

In addition to DriveTexas.org, a public-facing web app with current highway conditions across the state, TxDOT is working on a pilot effort to extend monitoring coverage to 80 radar-based gauges, installed and operated by USGS, that can measure both stage and velocity and provide the information necessary to calculate discharge. These gauges also connect to a cellular network, provide real-time data updates, and can produce water elevation data accurate to 2 millimeters. TxDOT found that coupling the radar streamflow gauges with lidar data for stream cross-sections can support predicting road inundation (McCarty et al. 2022).

“If the field—like the county maintenance engineer or bridge program manager—cannot use the data effectively, then it is not worth our while. It’s important they can access and use the information.”

—NCDOT

3.5 Partnerships in Practice

An array of key players are needed to operationalize, monitor, and make decisions based on flood forecasting information. A central office will typically monitor flood forecasting in partnership with district or field offices and will also determine an activation approach based on triggers. When an asset appears to be subject to a hazard impact, a field office or district will inspect or validate that prediction by going to the site to support the data integrity of the forecasting capability. If an asset is washed out or otherwise affected, then someone from the field will assess the damage and come up with a repair, potentially working with others when the damage is severe. All these steps require clear communication processes, roles, and effective tools.

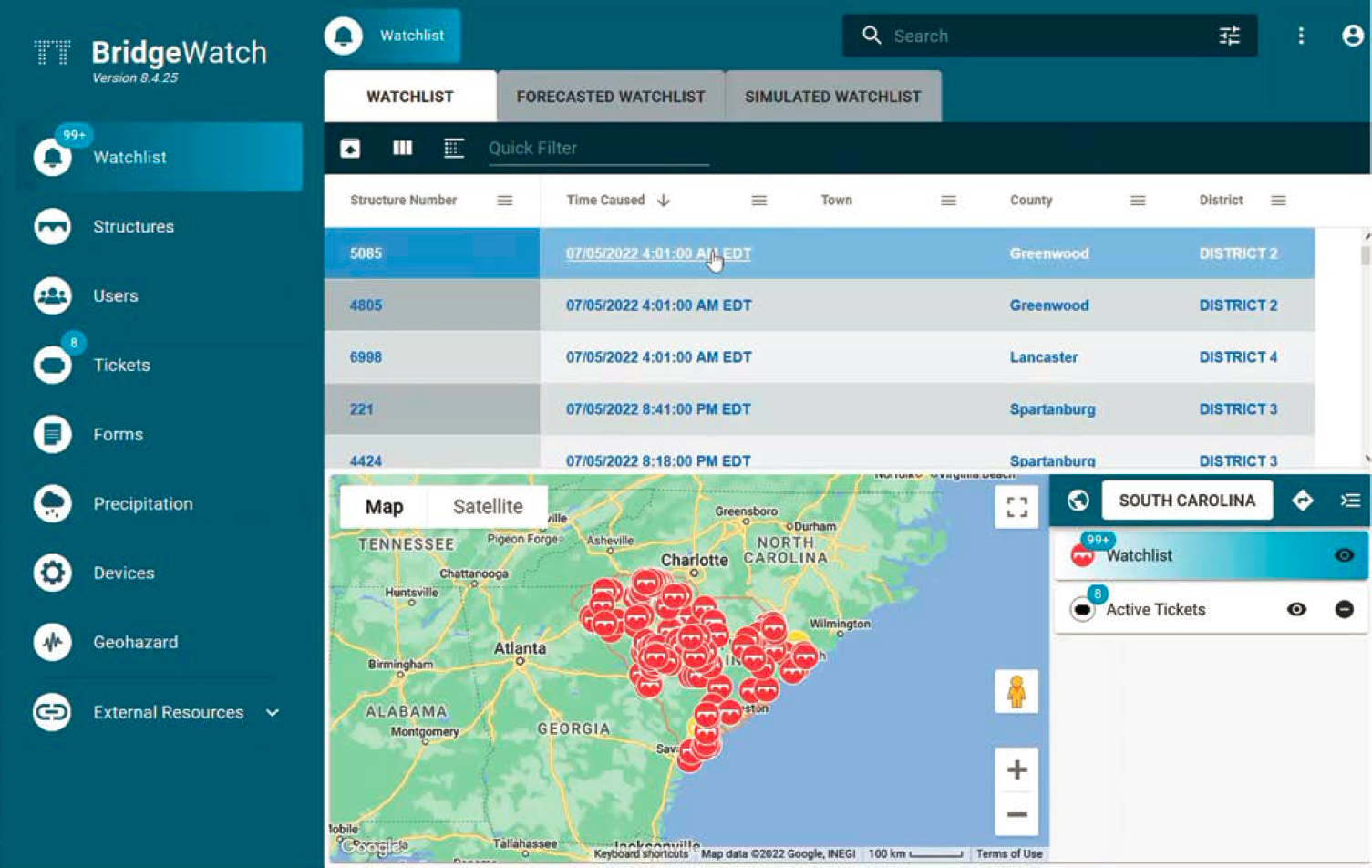

Private partners are often core team members involved in operationalizing a flood forecasting system. Some are involved in contributing key datasets. Others, such as BridgeWatch, monitor assets via a spatially explicit system and can provide real-time alerts or warnings. For example, NCDOT uses BridgeWatch to monitor 15,000 structures. Federal and state partners can also be integrated into the DOT monitoring protocols. For example, Ohio relies on its Office of Local Weather Prediction, and many DOTs rely on NWS briefings. DOT participants cited USGS as a potential partner in helping with field data collection.

TIPS AND TOOLS

TIPS AND TOOLS

See Chapter 4 for example communication protocols, such as identifying a business process for who receives flood forecasting information at various stages, key decision-making conversations, and developing interoperable data specifications.

See Chapter 5 for communication tools and methods.

See Chapter 5 for communication tools and methods.

Communication Methods

Clear roles within internal DOT departments enable regular and consistent communications. Examples of communications are shown in Table 3-5, and a few examples of how to approach these communications are discussed in the following:

- Create a method for the field to input information to a central office. DOTs have mentioned using a customer service phone number, a form for responders, and a GIS map or Excel spreadsheet to track key information.

- Make information digestible quickly. For example, Caltrans created a consistent format across its 10 offices that could be understood in 15 seconds.

- Solicit feedback from field staff and others with institutional knowledge of where it floods to identify locations of interest. For example, Minnesota sent a message to districts to ask each to send 5 to 10 spots with problems.

Common ways to collect flood monitoring information are directly from a gauge as well as from reports from staff, emergency services, citizens, and images and videos (Park et al. 2021).

Table 3-5. Sample messaging.

| Communicate risk levels at specific assets for field verification | “Assessments needed in next 16 hours at bridge X because anticipate reaching moderate threshold phase.” |

| Notification to leadership for acting on flood forecasts | “Our flood forecasting system is showing an event may be coming/a stage has been met. We’d like to request a decision convening between X stakeholders to decide how and when to respond based on our defined triggers.” |

| Uncertainty is involved in the forecast | “There are uncertainties involved in every flood forecast. Our system relies on monitoring events using X and Y data sources as well as defined thresholds that may indicate a potential event to watch or verify in the field. Every flood event helps improve our understanding of forecast accuracy. By validating results in the field, we can better track false alarms and redefine trigger thresholds.” |

| Messaging to partners and local communities | “As a partner on the state flood forecasting effort for the purposes of X, you have previously mentioned interest in seeing flood forecasts that hit Y triggers. As such, we would like to alert you that our flood forecasting system is showing an event may be coming/a stage has been met. As previously discussed, there are uncertainties involved in every flood forecast.” |

Data in Action: BridgeWatch

BridgeWatch (see Figure 3-5) is a proprietary software from USEngineering Solutions. This software provides real-time flood hazard monitoring at the asset level. It is currently used by several state DOTs, including those of Iowa, Connecticut, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Pennsylvania (USEngineering Solutions 2022). Many states that use the software do so in conjunction with other monitoring and data management systems (Park et al. 2021). The software aggregates multiple streams of real-time data from sources such as NWS and USGS. Local sensor-based monitoring systems can also be incorporated into BridgeWatch data platforms. The service can provide information on precipitation, coastal storm surge flow, hurricane tracking, USGS gauge flow, flood alerts, and scour-critical thresholds in a geospatial format in conjunction with DOT-provided asset locations (USEngineering Solutions 2022).

BridgeWatch can provide real-time alerts for assets at risk of flooding or scour. Alerts often require some collaborative calibration with state DOTs to minimize false alarms; the rate of false alarms can vary by local hydrology and hydraulics (Park et al. 2021). The system provides a mobile device–based platform for on-site documentation and reporting of field observations via a ticket system. The prepackaged nature of BridgeWatch supports implementation of the software for asset management and alert systems, but the proprietary nature of the system reduces modeling and alert system methodology transparency (USEngineering Solutions 2022).

In addition to bridges, USEngineering Solutions also provides monitoring software for dams and other critical infrastructure. These systems are currently less widely adopted by state DOTs (USEngineering Solutions 2022).

Figure 3-5. Sample BridgeWatch image.

External Partners

Once internal roles and communications are established, state DOTs will want to engage partner departments or agencies. There needs to be a base of trust and an understanding of the consequences of impact messaging before bringing in key partners as part of a community of practice. Otherwise, there is a risk external partners will hear about an event and not act or will miscommunicate the forecasts. A validation practice is needed to improve certainty as a DOT’s communications expand to a broader audience. Transparency around uncertainties with the information is important. However, once that base of trust exists, external partners can help maximize the reach and impact of forecasts.

There needs to be a base of trust and an understanding of the consequences of impact messaging before bringing in key partners as part of a flood forecast team.

Each external department will have a different purpose and may ask for communication about different types of data or information. For example, an emergency manager will want to know, in ways that allow them to respond to events quickly, which assets may be most affected by a natural hazard, while, to inform prioritizing future investments, state hazard mitigation staff will want to know how often a particular asset has been affected. A triggering event may be an all-hands-on-deck event for field staff, emergency managers, and others.

Some DOTs may also want to include local or county agencies. For example, to leverage their state tools, the Minnesota and Virginia DOTs were interested in including counties and cities that own bridges and other transportation assets. Some cities and counties may already monitor assets, or DOTs may host and report data for locally owned assets.

Prepare for Common Questions When Onboarding a Monitoring Team

When onboarding staff to a flood forecasting system, be prepared to address some common areas of confusion.

- What do short- versus medium-term probabilities mean and how should you use each?

- How often does the model run?

- What sources are included in the flood forecasting data, such as the National Water Model, local meteorological forecasts, or gauges?

- How is asset susceptibility accounted for? Are asset dimensions such as low chord elevations and culvert size considered when forecasting impacts?

- How much effort would be needed to keep a flood forecasting capability going? What type of engineering support is needed?