Flood Forecasting for Transportation Resilience: A Guide (2024)

Chapter: 5 Communications

CHAPTER 5

Communications

Key Focus

Developing tools and resources to communicate internally and externally about flood forecasting before, during, and after an event.

Key Takeaways

- Communication is important at every step of flood forecasting—from business processes to decision-making conversations and dissemination of flood forecasting information.

- Discussions are needed to establish protocols. Topics include when flood forecasting information is good enough to make decisions, how to talk about uncertainty, and staff roles and responsibilities.

- Investing in relationships with internal and external partners is an effective practice for communicating about flood impacts on transportation systems.

- When sharing data with partners, the data must be accessible and interoperable.

- As a DOT’s communications expand to a broader audience, a validation practice is needed to improve accuracy. Transparency around uncertainties with the information is important.

- There are tools and resources to manage and support communications.

Actions to Accomplish

- Determine who is important to reaching your goals.

- Create a business process for whom flood forecasting information goes to at various stages, including decision-making conversations, validation, and dissemination.

- Develop a process to evaluate new sources of information to integrate into operational decision-making.

- Create a plan for how you communicate uncertainty. Communicate uncertainty as you build confidence in your flood forecasting capabilities in consistent and accessible ways.

- Develop capabilities to disseminate flood event information to multiple platforms.

5.1 Overview

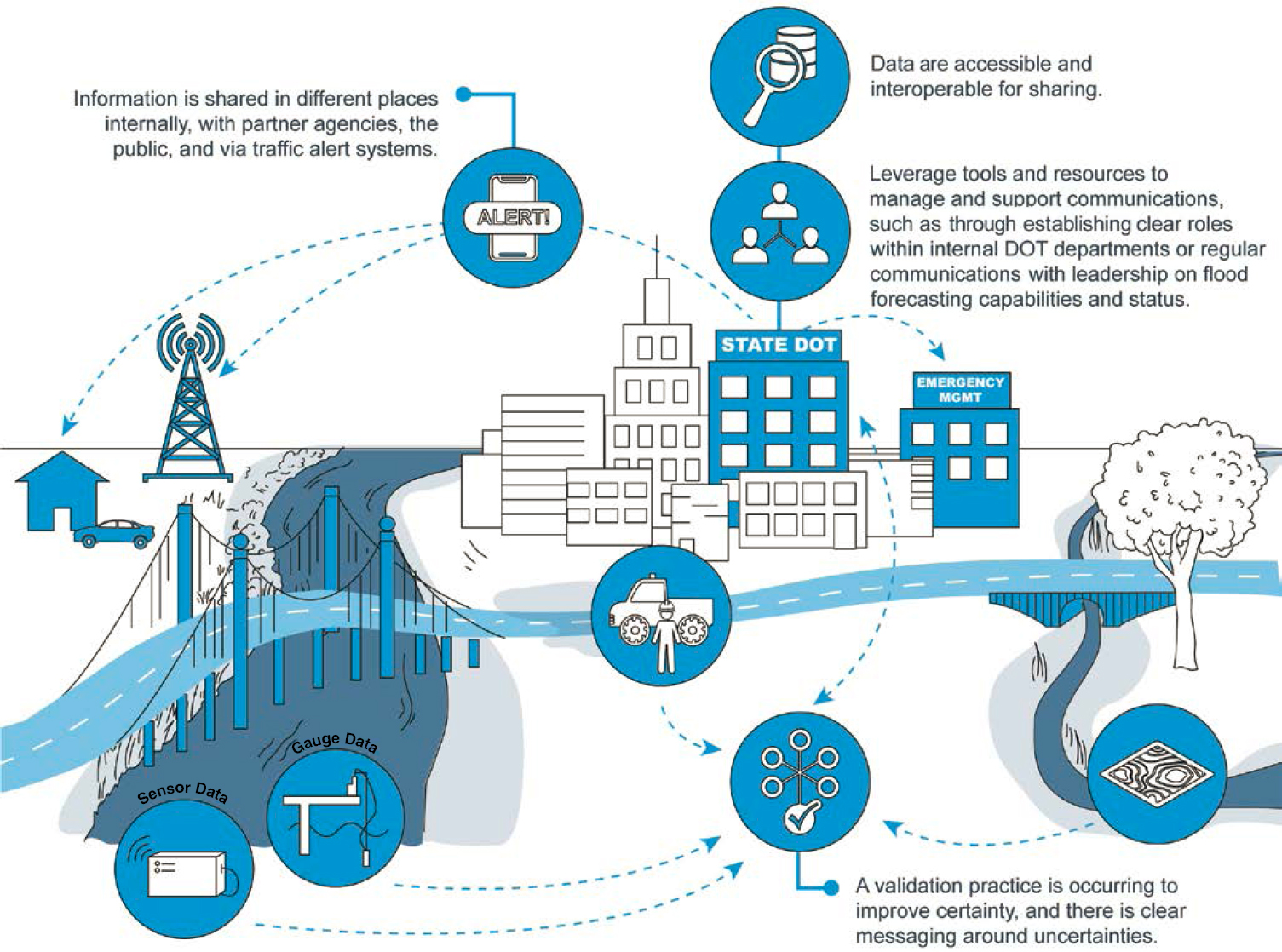

“Communications” refers to methods for sharing flood forecasting information within a team as well as with key stakeholders and the public. Figure 5-1 highlights mature communication capabilities.

How do you want to build your communications? Key information in this chapter:

- For whom and how each teammate is involved in a flood forecasting effort, see the Know Your Team section.

- For example communication resources and social media posts, see Figure 5-2 and Figure 5-3.

- For qualities and tips to make information more decision ready, see the Interoperable Communications section.

5.2 Introduction

Flood forecasting is a group effort. Communicating effectively to internal departments, leadership, stakeholders, and the public is crucial to leveraging flood forecasts—from closing a road to informing investment decisions. Successful communications build organizational support, create feedback loops, and empower decision-making.

This chapter will focus on how core users of flood forecasting can use internal communication methods to plan for, monitor, and respond to flood forecasts. DOTs that want to start flood forecasting will find out how to bring critical departments together, define roles, and develop communication protocols. DOTs with internal relationships that enable effective flood forecast monitoring and operations will find methods and considerations for communicating forecasts externally.

The following capabilities align with mature DOT communications:

- Information is shared in different places internally, as well as with partner agencies, the public, and via traffic alert systems.

- Data are accessible and interoperable for sharing.

- A validation practice is occurring to improve certainty, and there is clear messaging around uncertainties.

- Tools and resources are leveraged to manage and support communications, such as through establish clear roles within internal DOT departments or regular communications with leadership on flood forecasting capabilities and status.

This chapter is organized into the following sections to cover how DOTs may begin developing or expanding their communication capabilities:

- Know Your Team. Provides an overview of roles needed and typical corresponding job titles.

- Tools and Resources. Includes example tools, resources, and social media posts.

- Interoperable Communications. Provides an overview of why interoperability is important and tips for creating interoperable and usable communications.

Visit the Partnerships in Practice section of Chapter 3 for an overview of partnership types, communication methods, and sample messaging. That section also has text boxes for use in building confidence in flood forecasts needed to integrate external partners, sample monitoring interface elements, and common questions when onboarding a monitoring team.

5.3 Know Your Team

Knowing which teammates are involved in a flood forecasting effort and how is important. For example, individuals who monitor field conditions may set up operational procedures, monitor forecasts, and clearly communicate with field staff. Table 5-1 summarizes typical responsibilities needed during key forecasting stages. It also includes examples of staff titles involved during these stages.

Making the Business Case for Leadership

An important step that may be a barrier to getting started with flood forecasting is making the case for leadership support. Flood forecasting can offer the benefits of better preparation for flooding events, supporting faster response in the field and enabling more efficient use of resources.

Key considerations to address are the level of effort and cost to design and maintain the system within the agency or to contract with a commercial provider. DOTs can gather lessons learned from systems in practice to help with developing a business case for flood forecasting.

Partners That Make Up Your Team

Not every DOT has the same set of partners. Often, the right partner depends on the individual serving in a role at a particular time. As such, partners may sometimes look nontraditional; an example might be a natural resources group. A best practice is to stay aware and open so as to identify potential partner opportunities.

These flood forecasting partnerships can be formal or informal. When formal, an interagency body is involved in coordination, regular operations, and joint decision-making. As discussed in the Operations chapter, a DOT’s response to more severe flooding events may include engaging external partners

Table 5-1. Example flood forecasting responsibilities.

| Steps | Example Responsibilities and Titles |

|---|---|

| Build data foundations |

|

| Monitor flood predictions |

|

| Monitor field conditions |

|

| Respond |

|

| Record impacts |

|

| Communicate |

|

to establish EOCs, where emergency operations are directed and coordinated across multiple agencies. While EOCs are often temporary, TMCs are permanent entities that can coordinate with EOCs during an emergency event or during regular operations. TMCs monitor roadway conditions, support motorists and responding field personnel, and actively manage traffic flow. This group may consist of the core flood forecast team (e.g., partnering research institutions, field staff, engineers who develop data, and staff that monitor), agency safety personnel, agency communication staff, state hazard resilience staff, local community representatives, and federal agency representatives such as the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) or FEMA.

In addition, for more specialized efforts, DOTs may set up a working group. For example, a DOT may set up a working group to undertake research or examine past road closures to identify flood forecasting locations. DOTs may also be part of Silver Jackets groups, which are interagency teams that facilitate collaborative solutions to state flood risk priorities. See Chapter 6 for more on collaborating with external partners.

For example, Ohio DOT (ODOT) coordinates across divisions and other state organizations using different communication methods internally and externally. The agency:

- Coordinates across internal divisions and other state organizations that focus on maintenance, hydraulics, emergency management, communications, operations, and natural resources.

- Works with federal agencies or external partners, including NWS, FEMA, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and FHWA.

- Collaborates with Ohio Emergency Management Agency on hazard mitigation planning efforts.

- Handles press communication through its Public Information Office and radio alerts via the Ohio Emergency Management Agency.

5.4 Communication Tools and Resources

DOTs log and store flood data in several ways, including in existing bridge and culvert plans, local files, inspection reports, databases, and management systems, as well as via commercial offerings. These sources are likely familiar for DOTs, but DOTs can sometimes have critical information that is not aggregated and used.

Some DOTs share these databases or repositories with other divisions and offices or state and federal agencies. In some cases, states store these data across multiple locations or databases, while in others, they are in an integrated structured database. According to NCHRP Synthesis 573: Practices for Integrated Flood Prediction and Response Systems, most of the information shared across federal, state, and local organizations was via email (19 of 39 respondents marked as one of the options; respondents were allowed to select multiple answers) or online platforms (8 of the 39 respondents) (Park et al. 2021).

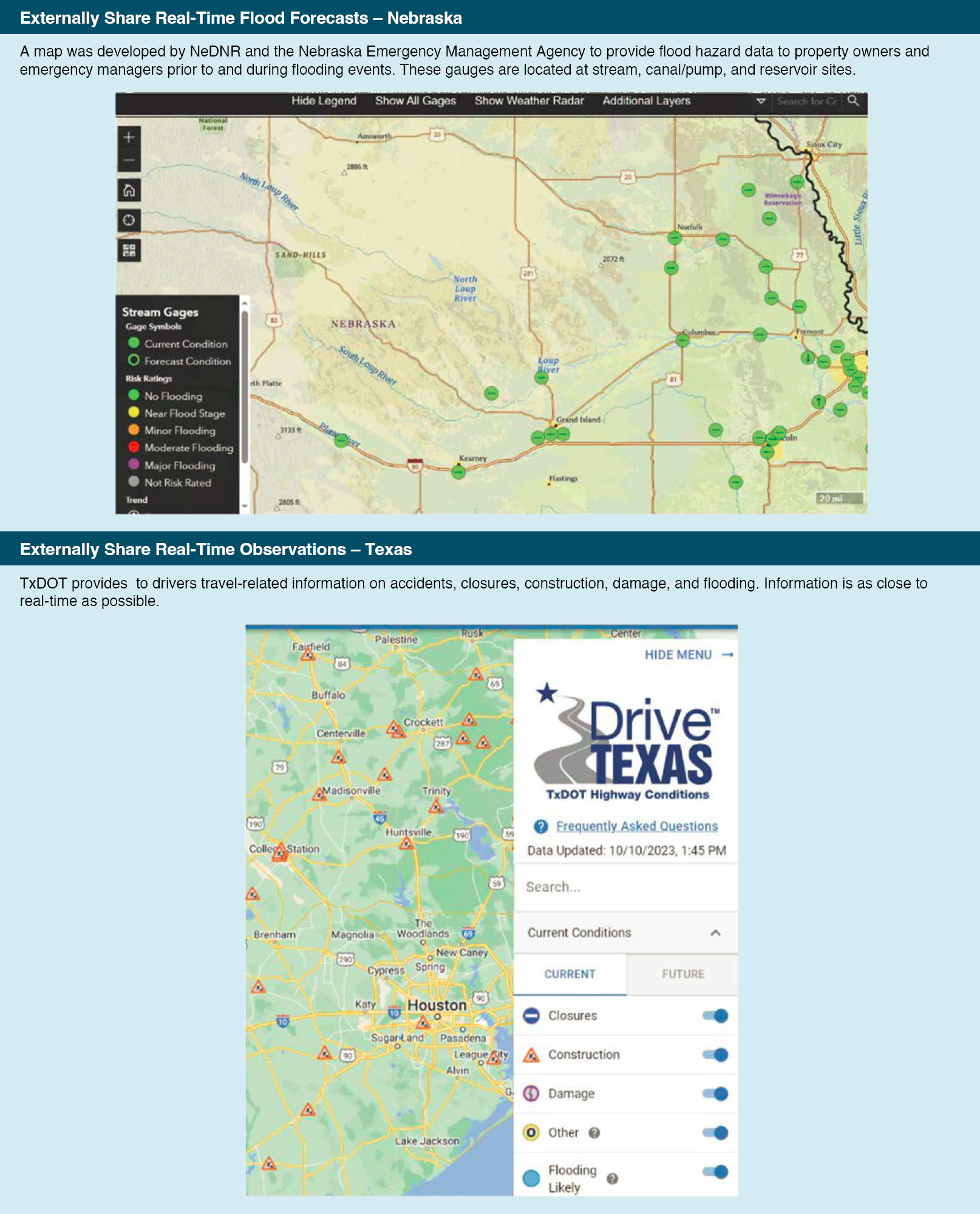

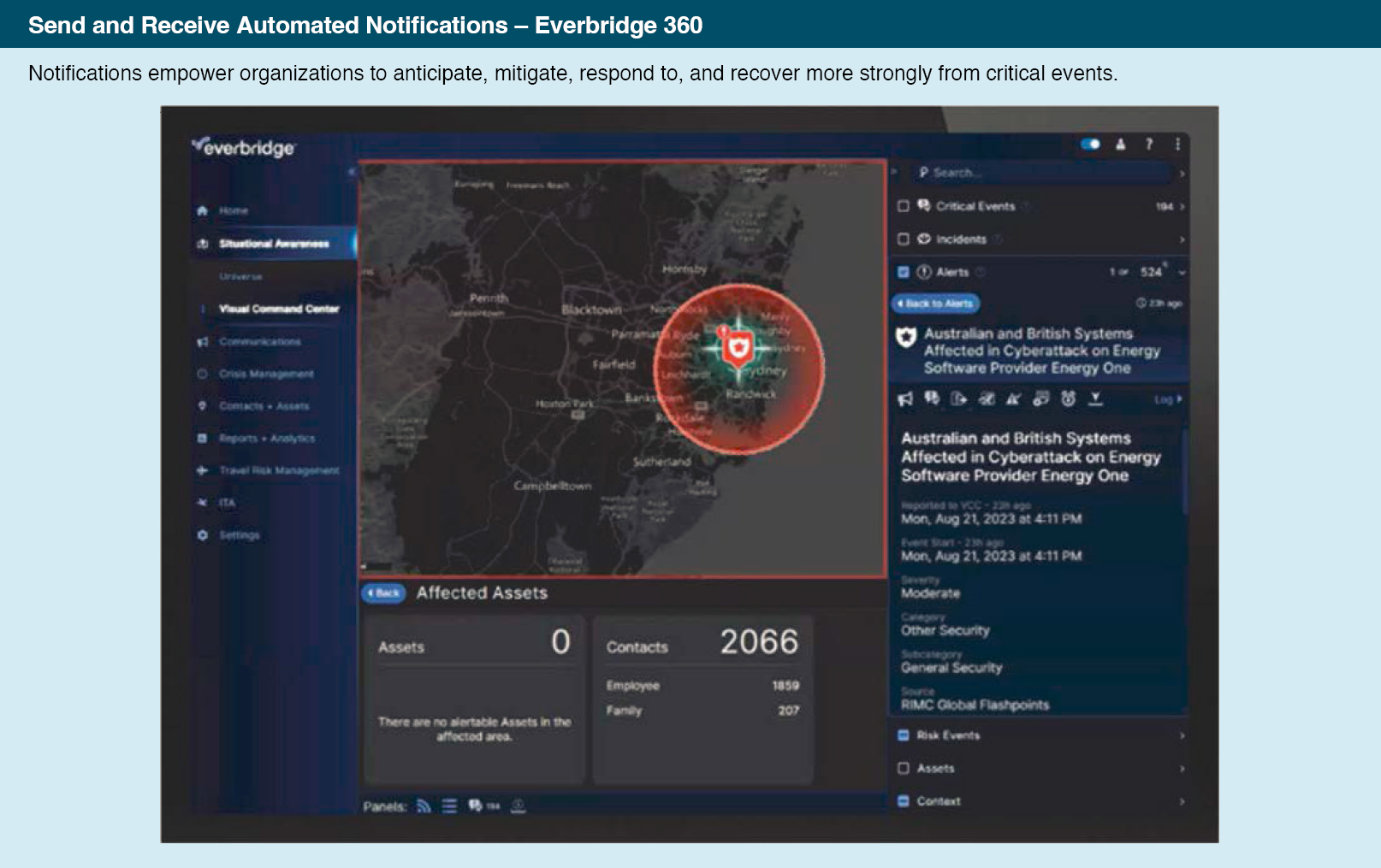

Examples of online platforms are provided in Figure 5-2. The Nebraska Department of Natural Resources (NeDNR) has a public-facing real-time flood forecasting tool. The map was developed by NeDNR and the Nebraska Emergency Management Agency, with funding from FEMA and the state of Nebraska. The map is intended to provide flood hazard data to property owners and emergency managers before and during flooding events. The legend includes gauges with current and forecasted conditions and color icons that represent a range from no flooding to significant flooding. These gauges are located at stream, canal/pump, and reservoir sites (Nebraska Department of Natural Resources 2023). Other tools are shown in Figure 5-2 (real-time observations, automated notifications).

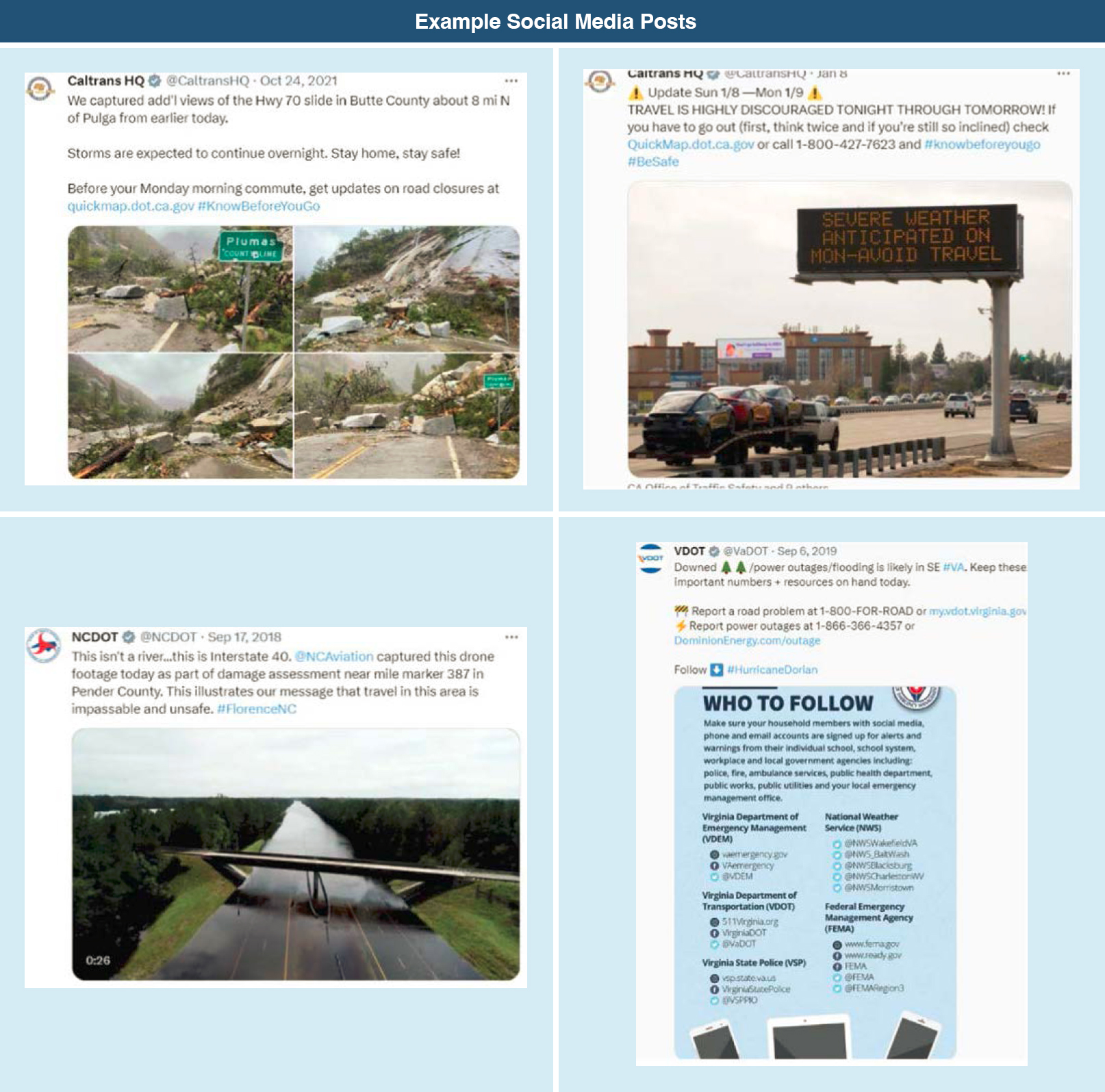

Social media platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram are useful for communicating with the public before an event. Figure 5-3 shows examples of social media posts from Caltrans, VDOT, and NCDOT.

TIPS AND TOOLS

TIPS AND TOOLS

DOTs will need to create ways to communicate uncertainty. See Chapter 3 for information on how DOTs measure and assess uncertainty, tips for building confidence, and sample messaging.

Interoperable Communications

In flood forecasting, information flows from a DOT to local and regional partners and, ultimately, to the public. It is no easy task to get the right information to the right person, at the right time, and at the right place to guide the right decisions and support beneficial outcomes (Open Geospatial Consortium 2023b). While a DOT may have data, analytics, and tools, they are often not connected to or leveraged by key stakeholders and users. Interoperable information can help close that gap. Data are interoperable when they can be easily reused and processed in different applications, allowing different information systems to work together (Gonzales 2018).

TIPS AND TOOLS

TIPS AND TOOLS

“Receiving a large amount of data and then analyzing, processing, and visualizing the data is only the first half of the work. The second half is getting the outputs of that work to the people . . . ”

Interoperable data may seem like the integration of information, but it really requires organizations coordinating with each other and coming up with a common path forward. DOTs need to converse with all potential data users to understand their needs, clarify any areas of confusion, and develop standards.

The qualities listed in the following and the tips in the text box highlight ways that information can be more “decision-ready” (Lavender and Lavender 2022).

- An agreed-upon trigger is present to activate the decision process.

- Access is provided to the information by each decision-maker.

- The most pertinent information is findable.

- Information is in the most useful format (e.g., a map with the key points or issues highlighted or a map showing different colored areas, each indicating a different value).

- A preestablished set of standards exists for data sharing and for partners providing data.

- Information can be uploaded and used on different platforms.

- Data are continually updated and improved.

- There is a preestablished method to extract data from key sources and then transform these into information suitable for supporting decision support.

- There are predefined methods for delivering outputs to key decision-makers.

- All possible users have and know any username and passwords required to access the system.

Tips for Making Information Decision-Ready

- Incorporate street maps, building footprints, and satellite imagery into foundation layers

- Provide visualizations and symbols for how to use the maps

- Consider incorporating web-based searching capabilities

- To help users find and process the data, ensure that datasets are self-describing

- Include a messaging feature

Figure 5-3. Example social media posts.

Figure 5-4. Example process for defining warning symbology.

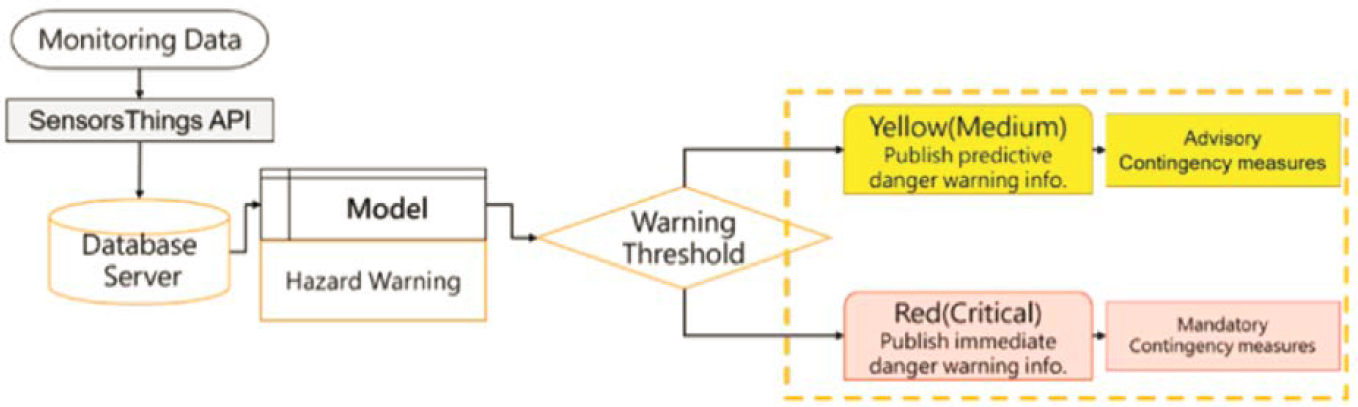

One component of interoperability is working alongside partners to preestablish symbology and thresholds so that information can be clearly interpreted and used when shared. Figure 5-4 shows an example of how partners may record their decisions for which threshold would trigger which corresponding symbology.

In an example of interoperable communications between Caltrans and NWS, Caltrans undertook an effort to improve forecast communications with its state NWS partner. Each had different boundaries and district numbers, which made it challenging to quickly understand which NWS district should act on a potential forecast. These two agencies created a unified forecast notification visual that could be quickly understood within their agency structures to address the issue.

If your DOT is starting to define how to communicate flood forecasting information in more useful ways to users or decision-makers, find an organization that is developing best practices and defining standards. For example, the Open Geospatial Consortium publishes standards and resources around key topics, including natural disasters. The consortium has a disaster pilot, where researchers can employ a use case or challenge to test and refine requirements and needs. Throughout the initiative, outputs have included a user guide, technical report, and feedback on the standards program.