Flood Forecasting for Transportation Resilience: A Guide (2024)

Chapter: 2 Data Foundations

CHAPTER 2

Data Foundations

Key Focus

Discovering available data sources and models for flood forecasting and how DOTs can access and interpret them.

Key Takeaways

- DOT data holdings (such as asset information and hydraulic models) can be extremely valuable for flood forecasting but are often difficult to catalog and access.

- Flood forecasting at the state scale often requires organization as well as automation that requires standardized, machine-readable, and readily available formats. Conversion of data into a usable database may require significant time and effort.

- Implementing data standards across an organization enables more efficient use of data and reduces the reliance on institutional knowledge.

- Flood forecasting will become more precise over time through enhanced data holdings, validation, and targeted investments.

- For most data types, existing federally produced data or data services are an adequate starting place.

Actions to Accomplish

- Determine your DOT’s data foundation goals.

- Identify data sources and take stock of your internal repositories.

- Identify locations of interest that are critical to operations and vulnerable to flooding.

- Determine ways to manage and integrate data into operations and data-sharing needs.

2.1 Overview

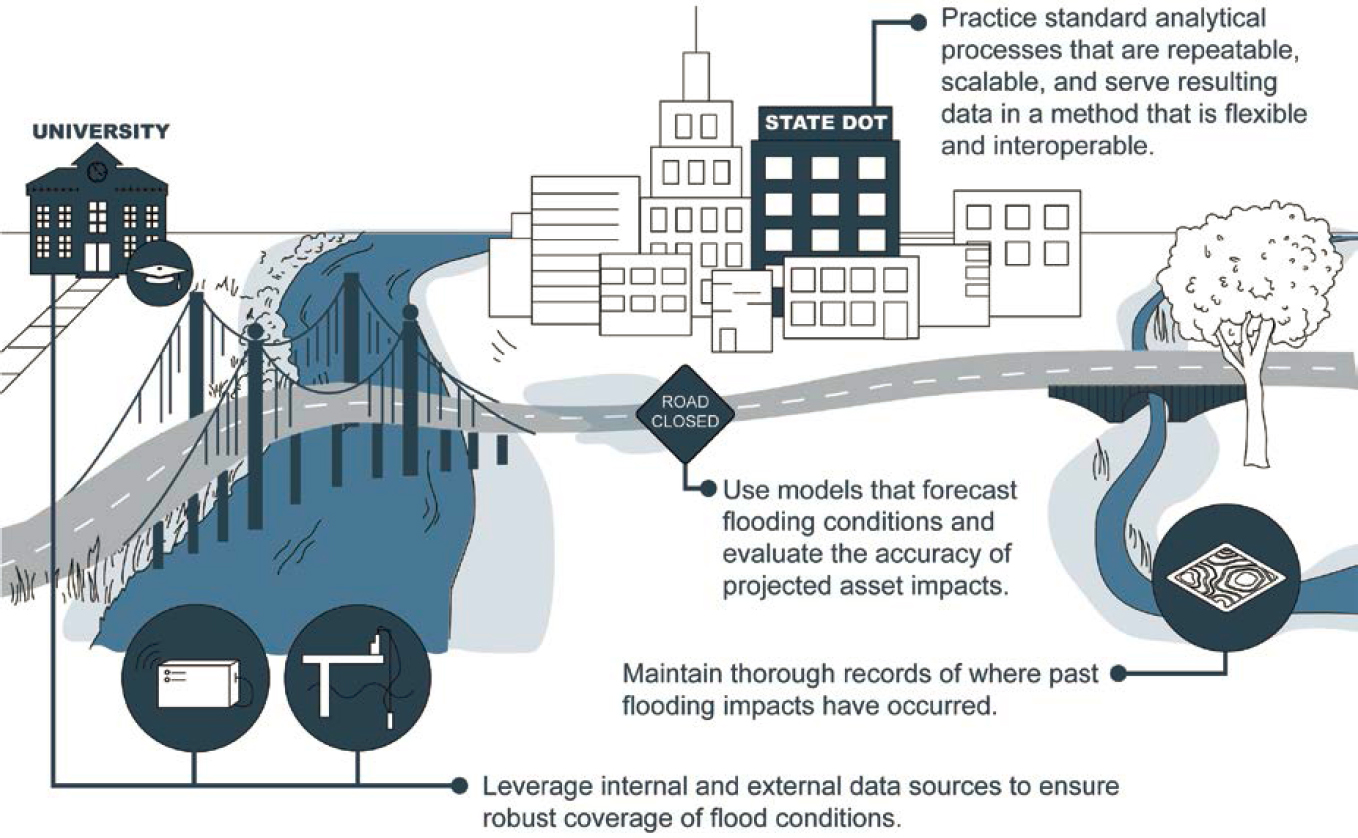

Data foundations refer to the key datasets that state DOTs need to begin forecasting flood events and use the results to assess impacts to their assets. Figure 2-1 highlights mature capabilities that support data foundations.

How do you want to build your foundations? Key information in this chapter:

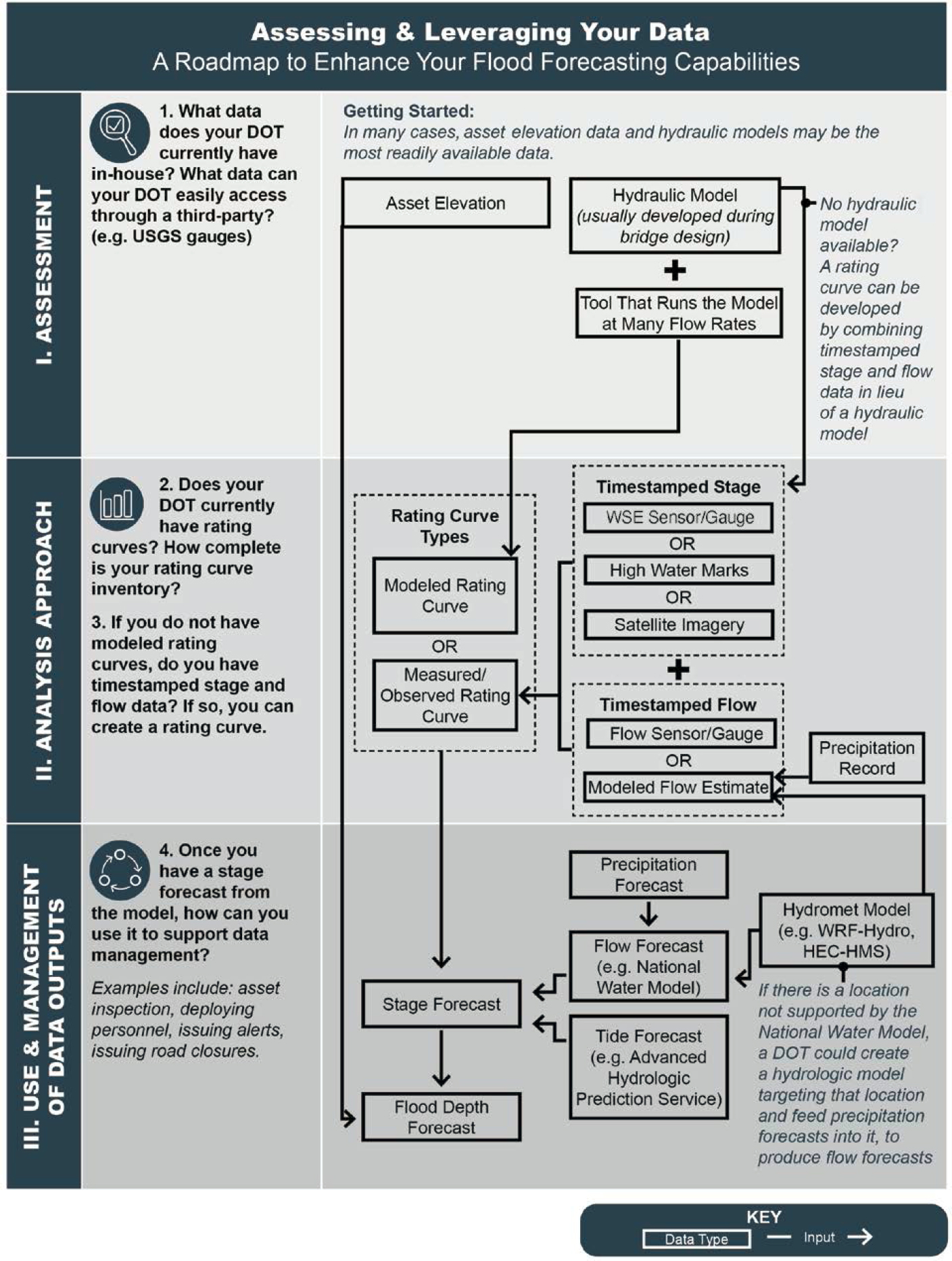

- For a road map to enhance your flood forecasting capabilities by assessing and leveraging your data, see Figure 2-2.

- For data foundation inputs, see Table 2-5.

- For creating rating curves, see Table 2-7.

- For deploying forecast models at DOT locations of interest, see the Use and Management of Data Outputs section.

2.2 Introduction

This chapter summarizes foundational datasets for flood forecasting, key inputs and processes for developing models, and how to leverage the resulting forecasts. DOTs that want to start flood forecasting will find information to weigh various approaches and obtain an overview of how these analyses work. DOTs that already use flood forecasts but want to build or advance capabilities will find ways to develop models and rating curves as well as to make flood forecasts more streamlined and shareable across departments (for definitions, visit the Key Terms section).

Central to any flood forecasting capability is good quality data. State DOTs rely on observational and modeled data to forecast flooding at transportation assets like roads and bridges. Typical flood forecasting systems continuously ingest raw forecast data and develop simulations to translate the input forecast data (precipitation or river flow) into an output flood elevation at a given location. Flood forecasting may include using regular weather forecasts and stream gauge thresholds to inform asset inspection, deploy personnel, issue alerts, and make road and bridge

closure decisions. This chapter will discuss how asset elevations can be paired with observed and modeled water elevation data to produce flood forecasts that support decision-making. Various sections in this chapter are incorporated into a road map to enhance flood forecasting capabilities by assessing and leveraging data (see Figure 2-2).

DOTs currently rely on asset data and flood forecasts to anticipate flood impacts, with varying degrees of complexity in the forecasting outputs. A mature DOT operation for assessing and leveraging flood forecasting data will include the ability to perform the following:

- Leverage internal and external data sources to ensure robust coverage of flood conditions.

- Maintain thorough records of where past flooding impacts have occurred.

- Use models that forecast flooding conditions and evaluate the accuracy of projected asset impacts.

- Practice standard analytical processes that are repeatable, scalable, and serve resulting data in a flexible and interoperable way.

This chapter is organized into the following sections to cover how DOTs may start or expand their asset data inventories and flood forecasting capabilities:

- Data Inputs. Provides an overview of common datasets a DOT needs to access or build before advancing to developing stage-discharge rating curves.

- Analysis Approach. Provides an overview of how, using these data inputs, DOTs create rating curves.

- Use and Management of Data Outputs. Describes the data outputs and forecasts that result from flood forecasting and how DOTs can use them in their decision-making.

- Roles and Partnerships. Identifies responsibilities of different personnel to operationalize a flood forecasting system.

Key Terms

A flood forecasting system orchestrates data inputs, models (or simulations), and forecasts to inform asset management. These elements are described in more detail in Table 2-1, Table 2-2, and Table 2-3.

- Data Inputs. Defining data inputs is the first step in developing a flood forecast capability. Types of data inputs are shown in Table 2-1.

- Models. Models simulate geophysical relationships that provide insights into when, where, and how much flooding will occur. Types of models are shown in Table 2-2.

- Forecasts. Forecast tools are used in tandem with models to predict flood impacts on DOT assets. Types of forecast tools are shown in Table 2-3.

A fully operational flood forecasting service relies on elevation data, historic flooding records, and what transportation assets a DOT wants to flood forecast, referred to in this guide as “locations of interest.”

2.3 Data Inputs

State DOTs leverage a variety of federal, state, and local data sources to support existing monitoring and response to flooding. A fully operational flood forecasting capability relies on elevation data, historic flooding records, and what transportation assets a DOT wants to flood forecast, referred to in this guide as “locations of interest.”

To build capabilities, a DOT often uses existing data to start flood forecasting while identifying and expanding its use of additional datasets. In many cases, asset elevation data and hydraulic models are the most readily available data. Existing models are often available to DOTs because they are produced

Table 2-1. Types of data inputs.

| Locations of interest | Locations of interest represent transportation asset locations where DOTs want to flood forecast due to factors such as past incidents, changed conditions, or scour concerns. |

| Ground elevation data | Ground elevation data characterizes landscape topography critical to building flood forecasting models and determining asset elevations (U.S. Geological Survey 2023a). Elevation data can be collected through lidar technology and converted to a surface grid digital elevation model (DEM) (U.S. Geological Survey n.d.). |

| Asset flood threshold elevations | Asset flood threshold elevations identify when an asset will be affected by flooding. Example thresholds include a bridge deck elevation or a low spot on a road. |

| Historical flooding records | Historical flooding records provide documentation of previous flood impacts and can support prioritizing locations for flood monitoring and forecasting. |

Table 2-2. Types of models.

| Meteorologic | Meteorologic models provide rainfall and wind predictions, which can be used with hydrologic, hydraulic, coastal, and statistical models to assess potential flood impacts. |

| Hydrologic | Hydrologic models simulate the movement of water through river basins by representing the physical processes involved, such as precipitation, evaporation, infiltration, and runoff. They consider factors such as soil properties, topography, and vegetation cover, and their primary outputs are channelized flow rates. |

| Hydraulic | Hydraulic models estimate the behavior of water, such as stage (the height of the water above or below a reference point) and velocity, within a river channel or floodplain. They require input data such as the geometry of channel and overbank areas, friction parameters, and flow rates. |

| Coastal | Coastal models focus on predicting the behavior of storm surges from coastal, lacustrine, or estuarine water bodies. To calculate flood conditions for a given storm event, their required input data include topography, bathymetry, and friction. |

Table 2-3. Types of forecast tools.

| Stage-discharge rating curves | Stage-discharge rating curves provide an important relationship used in flood forecasting that defines a river flood height for any given river flow rate. These can be developed by running hydraulic models at many flow rates. |

| Scour-critical thresholds | Scour-critical thresholds are often expressed as a stream discharge rate (the volume of water flowing through a channel) or water surface elevation. It is convenient to have thresholds expressed in terms of discharge since flow forecasts are widely available and can be directly used without developing a hydraulic model or rating curve. |

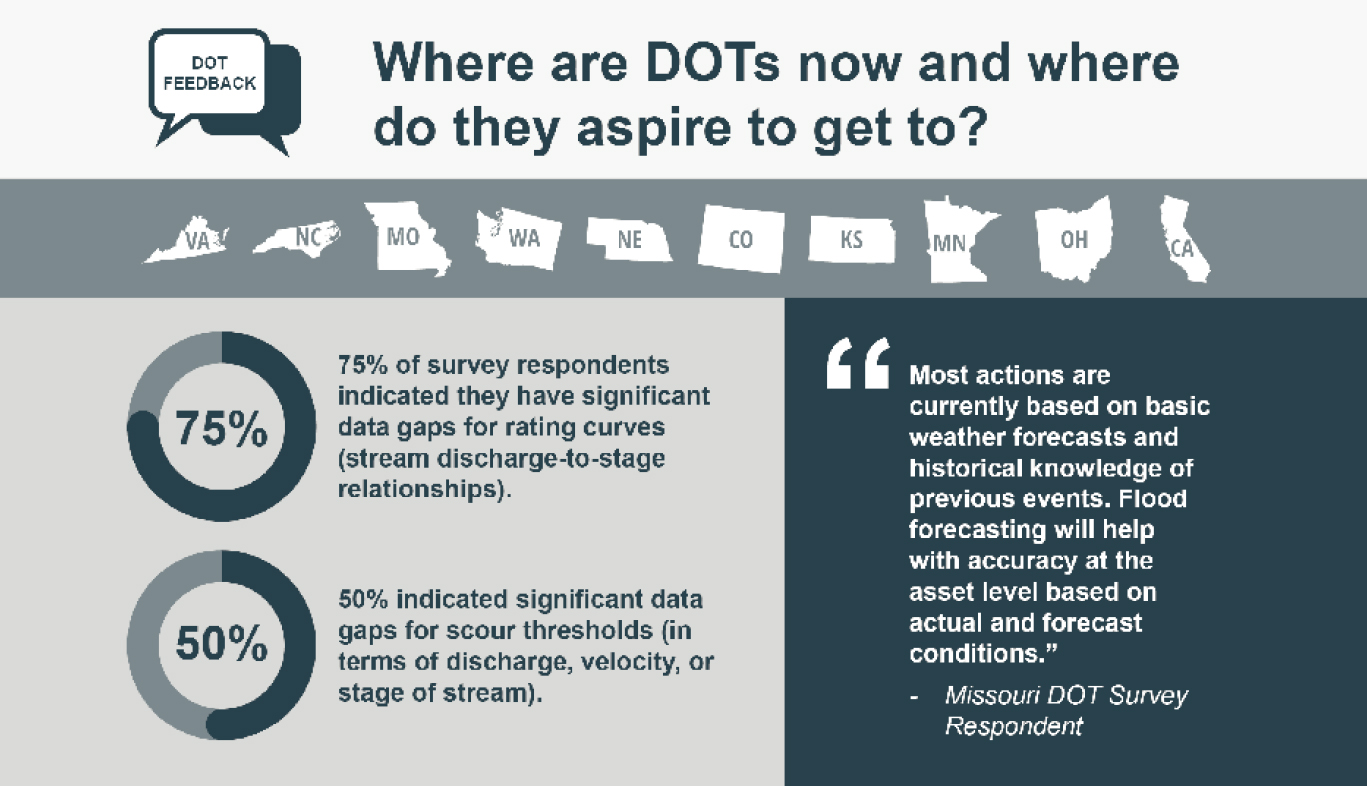

during the design and engineering phases of transportation infrastructure projects, such as for bridges and culverts. On the other end of the spectrum, rating curves and scour thresholds are more challenging to build toward and are capabilities missing for many DOTs (see Figure 2-3 for statistics). Both rating curves and scour thresholds can play a key role in developing an operational flood forecasting capability.

These foundational data inputs can be obtained from external providers or developed in-house by state DOTs. Federal data sources often leveraged include the National Weather Service (NWS) local meteorological forecasts, NWS Advanced Hydrologic Prediction Services (AHPS) for riverine stage/elevation and tide stage/elevation, and U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) gauge services for stream discharge and stage.

Despite differences in approach and data holdings between DOTs, common datasets are needed to enable a flood forecasting capability. Table 2-4 provides a framework to classify datasets by how the data can be accessed, what geographic coverage is available, and what resources are needed to collect and use this information. This table should assist the reader in reviewing Table 2-5, Table 2-7, and Table 2-9. Table 2-5 outlines examples of foundational datasets with corresponding classifications. Tables that outline data to support developing a rating curve and creating forecasts from that rating curve are provided in the Analysis Approach (Table 2-7) and the Use and Management of Data Outputs (Table 2-9) sections.

DOTs currently store asset data and locations of interest in a variety of formats with different technical requirements. It is beneficial for DOTs to choose data formats that are convenient for staff to maintain and are also machine-readable. Table 2-6 illustrates some benefits and drawbacks of competing data formats. When identifying locations of interest may also be an appropriate time to establish baseline data, such as typical water levels and typical rate of water rise.

TIPS AND TOOLS

TIPS AND TOOLS

At the heart of flood forecasting are good data and information. Your organization may already have information that will enable you to flood forecast. Reach out to your colleagues to identify available data.

TIPS AND TOOLS

TIPS AND TOOLS

DOTs are often rich in the type of information needed to perform flood forecasting. Establishing a flood forecasting capability will help institutionalize knowledge of what information you have, where it is, and how to use it. See Roles and Partnerships for more information on who should be involved.

Table 2-4. Definitions of data classifications.

| Provider Type How can the data be accessed? |

Confederated Data are publicly accessible and provided by a federal government agency or analogous authoritative consortium. |

| State/Local Data are publicly accessible and provided by a state or local government or a university. |

|

| Private Data are restricted to paid access and provided by a commercial vendor or analogous institution. |

|

| Refinement Level How accurate and precise is the data type? |

Low Data are low resolution or are based on an estimate, such as asset elevation from a coarse-modeled elevation surface. |

| Medium Data have a moderate level of accuracy or precision. |

|

| High Data are high resolution and precise, such as ground elevation that is hand measured with a survey tool. |

|

| Availability What geographic coverage is available? |

Low Data are sparsely available. |

| Medium Data are somewhat available in all regions of the continental United States or fully available in select regions. |

|

| High Data are available throughout the vast majority of the continental United States. |

|

| Cost and Effort What resources are needed to collect and use this information? |

Low Requires little to no field work to obtain data and minimal tooling, processing, and storage needs. |

| Medium Requires some fieldwork to collect data and a moderate amount of internal tooling, processing, and storage needs, or a temporary contractor to process and host the data. |

|

| High Requires significant field work, major internal tooling, processing, and storage needs, or a permanent contractor to process and host the data. |

|

| Easily Started Do the data require an analyst to review and edit? |

✓ Do not require a data analyst to input, review, and edit. |

| ✖ May require a data analyst to input, review, and edit. |

| Reliability Do the data formats have quality control measures for the data? |

Low Data format does not have quality control measures, such as restricted data types or ranges. |

| Medium Data format has some quality control measures. |

|

| High Data format has quality control measures for what can be inputted. This typically positively correlates with machine readability. |

|

| Machine readability Can the data be understood and processed by a computer? |

✓ Consistent data in a format that can be read by a computer. |

| ✖ Data in inconsistent formats that cannot be read by a computer, such as embedded in an email message. |

Table 2-5. Fundamental data input examples classified by provider type, availability, and cost and effort to obtain and use.

| Data Type | Use Case | Source | Provider Type | Refinement Level | Availability | Cost and Effort |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ground elevation | Sample to estimate asset elevations | USGS 3DEP | Confederated | Varies | High | Low |

| Non-3DEP | State/local | High | Low | Medium | ||

| Asset elevation | Pair with stage forecast to assess impacts | As-built drawing | State/local | High | Varies | High |

| Sampled from elevation surface | Varies | Low | High | Low | ||

| Recurring event logs (flood/scour) | Inform prioritization of locations of interest | Emergency management and maintenance databases | State/local | High | Low | Medium |

| Satellite imagery | Develop rating curves. To distill the most value, pair with machine learning analysis. | Umbra | Private | High | High | Medium |

| ICEYE | Private | High | High | Medium | ||

| Stream measurements (flow or elevation) | Validate forecasts, develop hydraulic rating curves | Sensors | State/local | High | Low | Medium |

| USGS gauges | Confederated | Varies | Low | Low |

Note: 3DEP are the products of the National Elevation Dataset.

Table 2-6. Data formats for locations of interest.

| Format | Easily Started | Reliability | Machine Readability | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geospatial file (e.g., geopackage or shapefile) | ✓ | ✓ | High | Enforces field types. |

| Microsoft Excel spreadsheet | ✓ | ✖ | Medium | Does not enforce field types. Concurrent edits are possible under certain circumstances. |

| Delimited values (e.g., CSV) | ✓ | ✖ | Medium | Does not enforce field types. Concurrent edits are not possible. |

| Free and open-source software (FOSS) database system (e.g., PostgreSQL) | ✖ | ✓ | High | Highly extensible and standardized. Cloud-compatible. |

| Proprietary database system (e.g., ArcSDE) | ✖ | ✓ | High | Extensible and standardized. Cloud-compatible. Proprietary dependency with licensing fees. |

| Microsoft Access database | ✖ | ✓ | Medium | Obsolete, requires proprietary tooling. |

| Narrative description of location | ✓ | ✖ | Low | Extraction of coordinates is manual or requires the use of artificial intelligence or machine learning. |

Making Elevation Data Work for Your DOT

Elevation data are critical to advancing flood forecasting capabilities. These data can be used to estimate asset elevations or build new hydrologic and hydraulic (H&H) models. The resolution and currency of topographical elevation data can significantly affect the accuracy of H&H models and asset elevation estimates. Low-resolution digital elevation models (DEMs) often do not capture details such as stream thalwegs and road embankments.

The highest resolution inland federal DEM is the USGS 1-meter product of the National Elevation Dataset (NED). NED products, sometimes referred to as 3DEP, serve as a good default for wide use due to ever-expanding coverage of high-resolution data (suitable for hydraulic analysis), continuous refreshment of low-resolution data (suitable for hydrologic analysis), uniform vertical data, predictable tile layouts and file structure, and high-performance cloud hosting. Other DEM sources, such as NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric

Administration) Digital Coast and state/local/collegiate organizations, may provide additional coverage in certain areas, but are difficult to leverage reliably in a scalable, maintainable manner.

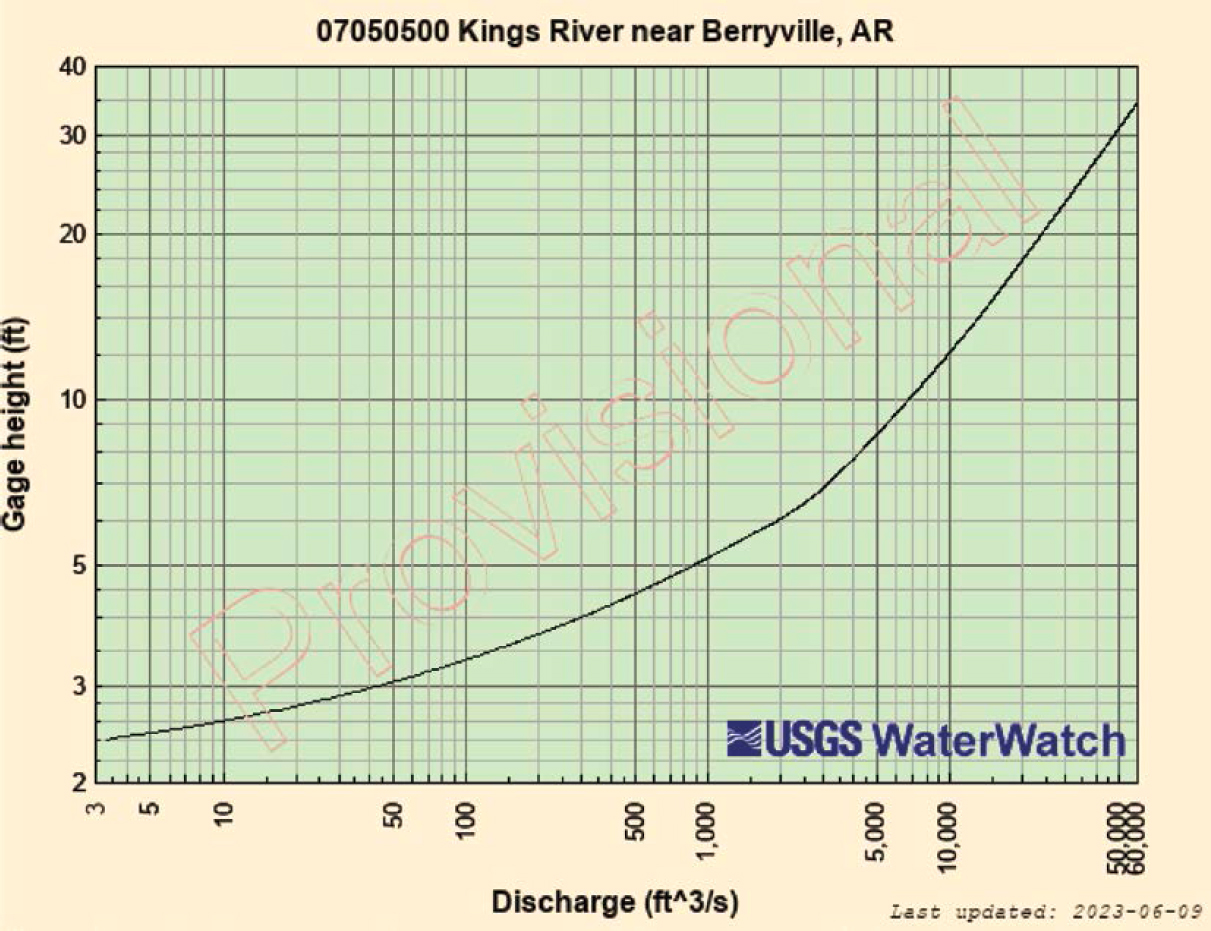

As part of this research effort, the research team sampled DEMs to estimate flood-relevant elevations, such as top-of-deck elevation thresholds that when exceeded result in minor flooding. Based on these elevations and the creation of new hydraulic models, approximate stage-discharge rating curves were developed. Stage-discharge rating curves support flood forecasting by defining a river flood height for any given river flow rate. Predicted flood elevations can be compared to critical asset elevations to evaluate potential impacts.

2.4 Analysis Approach

DOTs use data inputs to create rating curves and the resulting forecasts. As mentioned in the introduction of this chapter, stage-discharge rating curves are an important relationship used in flood forecasting for defining a river flood height for any given river flow rate. If a DOT has either time-stamped stage or flow data or a hydraulic model that can be run at many flow rates, then the agency can create a rating curve. For example, hydraulic rating curve sensors or satellite imagery can be paired with a river flow forecast to produce a river stage forecast. The flood forecasting system continuously ingests raw forecast data and applies the component simulations to translate the input forecast data (typically precipitation or river flow) into an output flood elevation at a given location.

Hydraulic Rating Curves

The hydraulic rating curve defines a river flood height for any given river flow rate using a predetermined mathematical relationship. A rating curve can be generated from any hydraulic model as long as the model can be executed as a spectrum of simulations (varying inputs).

Many existing hydraulic models have been created with the intent of defining required dimensions of an asset, such as appropriate bridge height or target culvert size, and therefore were only executed for specific discrete simulations (e.g., the “50-year flow”). If the model can be executed iteratively across a wide range of flow rates, the combined results of all these simulations serve as a hydraulic rating curve. Figure 2-4 shows a rating curve developed at a USGS gauge site.

Rating curves from hydraulic models alone may not be sufficient to provide forecasting information, but when used in conjunction with flow predictions, they can form the basis of a forecasting approach.

TIPS AND TOOLS

TIPS AND TOOLS

Rating curves can be created based on the information you already have. After determining what data your DOT has, you can explore options to apply it.

Scour

Another useful dataset that many DOTs may have on hand is scour-critical information, expressed as stage or flow thresholds for bridges or culverts. A scour threshold can be paired with a flow or stage forecast to produce a scour hazard forecast and trigger post-event scour monitoring or repair actions. In cases where scour information includes response activities

Figure 2-4. USGS rating curve example.

based on exceedance of a threshold (e.g., road closure if the flow exceeds a given rate), hydrologic forecasts provide valuable lead time for response management.

Choosing Your Approach

Building on previously noted input data, Table 2-7 includes data that can be leveraged to create a rating curve, how the data can be accessed, what geographic coverage is available, and what resources are needed to collect and use this information.

How Do Flood Forecasting Models Work?

Flood forecasting systems compute physical simulations automatically or on the fly as new forecasts are published. However, in practice, to save considerable processing burden, the results of existing component simulations are cataloged for retrieval based on the closest match to the input forecast.

For example, the following numbered list and Table 2-8 illustrate the broad steps a flood forecasting system follows when creating forecasts:

- Setup and Preprocessing. A hydrologic model is run at varying amounts of rain (3.5, 4.0, 4.5, and 5.0 inches), and the output flow rate of each simulation is saved. A hydraulic model is run at varying amounts of flow to develop a stage-discharge rating curve.

Table 2-7. Datasets to create a rating curve classified by provider type, refinement level, availability, and cost and effort to obtain and use.

| Data Type | Use Case | Source | Provider Type* | Refinement Level* | Availability* | Cost and Effort* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydraulic rating curve | Pair with river flow forecast to produce river stage forecast | HEC-RAS model | Varies | High | Low | High |

| Sensors | State/local | High | Low | High | ||

| High-water marks | Varies | High | Low | High | ||

| Satellite imagery | Confederated/private | Medium | High | Medium | ||

| Scour threshold | Pair with flow and stage forecast to produce scour hazard forecast and trigger post-event scour monitoring and repair actions | Official scour analysis reports | State/local | High | Low | Medium |

*See Table 2-4 for definitions of provider type, refinement level, availability, and cost and effort.

- Ingestion of Live Inputs. A database continuously fetches the latest rain forecast, which indicates that a storm next week will deliver 4.2 inches of rain.

- Sampling of Preprocessed Simulations. The system looks through its own catalog of hydrologic simulations previously run and identifies the two existing simulations that bound the incoming rain forecast (4.0 and 4.5 inches).

- Estimation of Flood Response. The system interpolates between the results of existing hydrologic simulations to estimate the river flow rate, then looks up the corresponding flood stage from the existing rating curve.

Of these steps, all except Step 1 are practically instant, resulting in a system that can react to precipitation forecasts in real time and with low processing overhead.

TIPS AND TOOLS

TIPS AND TOOLS

It is important to present the information of model outputs to the public clearly and understandably, emphasizing the uncertainties associated with the forecasts. For more information, see Chapter 5.

Validation and Communicating Uncertainty

One critical component of any forecasting system is understanding the system’s limitations, uncertainties, and assumptions. The accuracy of forecasts depends on the quality of input data, calibration and validation procedures, and the precision of the model itself. To improve accuracy, underlying simulations and mathematical relationships should be regularly updated as conditions change and new data become available. For example, new development in watersheds, different land use patterns, or enhanced flood control measures could result in changes to the topography and, consequently, hydrologic models that inform flood forecasts.

Data in Action: The National Water Model

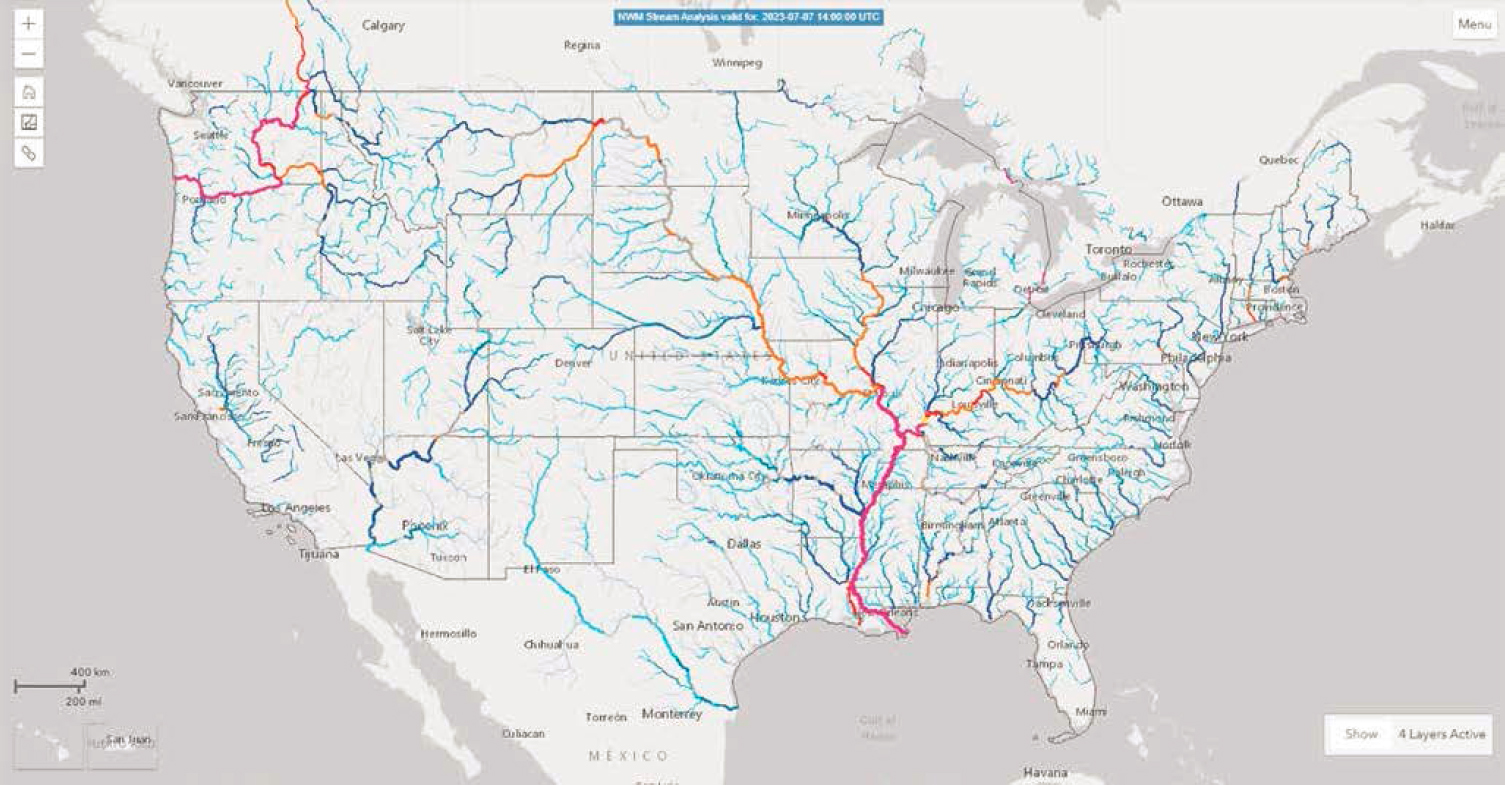

The National Water Model (NWM) is primarily a streamflow forecasting service operated by NWS. It estimates flow for nearly every stream segment within the medium-resolution network of the National Hydrologic Dataset (NHD), covering about 2.7 million locations across the continental United States. The forecast products are provided as short-range (18-hour), medium-range (8.5-day), and long-range (30-day) projections. NWM also covers some areas in Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. See Figure 2-5 for an image of the NWM map viewer.

The NWM system works by gathering meteorological-forcing forecasts (primarily precipitation) from various sources and feeding them into a nationwide WRF-Hydro model, which translates rain into streamflow. NWM publishes the streamflow forecasts as well as the forcing data. Although not commonly used, forcing data can be valuable; for example, a DOT could feed the forcing data into an HEC-HMS model to compute streamflow on the fly more accurately than the nationwide WRF-Hydro model employed by NWM.

In addition to forecasts, NWM also provides analysis and assimilation products, which are produced post-flooding conditions and serve as estimates of what occurred. Users may compare forecasts against these assimilation products to help with debriefing and validation.

In September 2023, NWS launched Flood Inundation Mapping Services, which provides floodplain forecasts derived from streamflow forecasts from NWM and the River Forecast Center for select regional locations. See the Data Types section in Chapter 3 and the Leveraging Partner Resources section in Chapter 6 to learn more.

Figure 2-5. Image of the NWM map viewer.

Table 2-8. Example interpolation of forecast event between pre-simulated events.

| Source of Input Rain | Input Rain Depth (in.) | Flow Rate (cfs) | Flood Stage (ft) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arbitrary simulation input | 5.0 | 22,000 | — |

| Arbitrary simulation input | 4.5 | 21,000 | — |

| Precipitation forecast | 4.2 | 20,400* | 12.7** |

| Arbitrary simulation input | 4.0 | 20,000 | — |

| Arbitrary simulation input | 3.5 | 19,000 | — |

*Forecasted flow interpolated between bounding simulated events;

**forecasted stage identified from existing rating curve.

2.5 Use and Management of Data Outputs

As noted previously, there are foundational datasets common to most flood forecasting programs, but the details of each implementation can vary widely based on data completeness and format. Gaps in the required data may exist. When the 10 participating DOTs were surveyed in 2023, seven responded that they had “significant gaps” in available rating curve data, three indicated significant gaps in asset overtopping elevations (bridges, culverts, and approach roads), and six indicated significant gaps in scour thresholds (identified critical levels of streamflow, velocity, or stage). Encouragingly, only one indicated significant gaps in culvert dimension data (barrel size, length, and shape), and only two indicated significant gaps in low chord elevation data of bridges. This suggests that many DOTs would be able to create detailed hydraulic models for their critical assets that could be used to generate high-quality rating curves to feed into a flood forecasting system.

Forecast models can be deployed independently or coupled in a variety of ways to provide useful information at DOT locations of interest:

- Meteorological forecasts from the weather service can be used to identify likely flood locations based on local knowledge or established relationships (i.e., whenever it rains here, this road floods).

- Hydrologic forecasts, such as those provided by the NWS, can provide advanced warning of potential high-flow locations hours to days in advance.

- Coupled models can provide additional sources for forecasts:

- Meteorologic forecasts developed by the NWS or other entities can be combined with local hydrologic models to provide forecasts at locations of interest where models exist.

- Hydrologic and hydraulic models—or rating curves—can be coupled for forecasting stage and timing of impact based on forecast meteorologic predictions.

- Coastal models can provide surge forecasts using wind and pressure data from meteorological and tidal forecasts.

- Pure tidal forecasts alone can be used to predict flooding in areas susceptible to sunny-day king-tide flooding (nuisance flooding).

TIPS AND TOOLS

TIPS AND TOOLS

Once you have your data and know how to use them, consider how to steward the sources and where to share the data.

Additional details on refinement level, availability, and cost and effort to obtain and use of different forecasts are shown in Table 2-9.

A modern data management system, supported by policy enforcement, enables a DOT to fully harness the breadth and depth of models and forecasts available to it. For example, every DOT

Table 2-9. Datasets to create a forecast classified by provider type, refinement level availability, and cost and effort to obtain and use.

| Data Type | Use Case | Source | Provider Type* | Refinement Level* | Availability* | Cost and Effort* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| River flow forecast | Pair with hydraulic rating curve to produce stream stage forecast. | National Water Model | Confederated | Medium | High | Low |

| HEC-HMS model | Varies | High | Low | High | ||

| Tide Forecast | Improve the accuracy of riverine hazard forecasts affected by tide. Pair with asset information to produce a tide hazard forecast. | National Weather Service AHPS | Confederated | Medium | Medium-high | Low |

| River stage forecast | Pair with asset information to produce a riverine hazard forecast. | Commercial vendor | Private | Unknown | Unknown | Medium |

| Precipitation forecast | Pair with a hydrologic model (e.g., HEC-HMS or WRF-Hydro) to produce a river flow forecast. | National Water Model Forcing Data | Confederated | Medium | High | Low |

| Scour threshold | Pair with flow and stage forecast to produce scour hazard forecast and trigger post-event scour monitoring and repair actions. | Official scour analysis reports | State/local | High | Low | Medium |

*See Table 2-4 for definitions of provider type, refinement level, availability, and cost and effort.

likely owns a substantial cache of hydraulic models, such as HEC-RAS files, but it is often difficult to extract useful information from them consistently and at a large scale. Many such models were prepared without policies dictating standardization of file naming or metadata (e.g., consistent documentation of vertical datum). Most models are not spatially cataloged and are difficult to identify and retrieve for a given location. By carefully building databases and processes to store, analyze, and serve the required data, the investments already made in producing the raw information (such as the HEC-RAS models) can begin to pay off.

When significant gaps exist, innovative solutions must be employed to make approximate estimates of the missing information, often requiring the handling of data sources that are disparate, overlapping, or inconsistent. When designing such solutions, it is suggested that, where possible, DOTs default to using confederated data sources. These sources typically have high

coverage, ample documentation, and long service lifespans. Tooling designed to leverage confederated sources can be shared widely, and development can be more easily crowdsourced due to high standardization, enabling a community of practice to flourish. Liability associated with authoritative sources is much lower than that of custom data products with less notoriety.

When developing a data management system, an important first step is to define the requirements of the overall flood forecasting program and identify which components will be serviced by third-party vendors. DOTs can then evaluate the existing data management practices of the organization (data holdings, information infrastructure, and agency policies) and draft a timeline or road map for the achievement of goals (high-level, 3-year, or 5-year). The design of the data management system should be tailored to the DOT’s priority data resources. For example, a program aiming to build hydraulic rating curves at each site empirically using stream sensors would have different requirements than a program relying on iterative simulation runs of existing HEC-RAS models to generate rating curves. Differences between these programs would materialize in interagency agreements, data maintenance and update strategies, storage requirements, and processing capabilities. Identifying the roles of personnel in establishing and maintaining a data management system to support flood forecasting is also critical to implementation, as discussed in the next section.

TIPS AND TOOLS

TIPS AND TOOLS

Research partnerships can be a force multiplier for your organization.

2.6 Roles and Partnerships

The road to advanced flood forecasting capabilities does not have to be walked alone. Partnerships promote collaboration and shared experiences, resulting in deepened collective expertise. Research institutions, universities, and local and federal agencies can provide critical technical expertise and funding, as illustrated in Figure 2-6.

Federal agencies, such as the USGS, can assist with field data collection. The U.S. DOT and the FHWA offer funding opportunities for transportation-related research studies. The FTA offers State of Good Repair (SGR) grants to help transit agencies with maintaining bus and rail systems. To be eligible for this funding, DOTs must develop a transit asset management plan that describes the condition of the physical assets the agency owns and maintains and a strategy for investing in those assets. The transit asset management plan further supports transit agencies in managing their assets and achieving SGR as infrastructure ages and natural hazard conditions change.

Research institutions and universities can provide valuable expertise and access to large networks of information. Universities and research institutes can partner with state DOTs on grant funding applications, which can increase the competitiveness of the application.

State DOTs can also explore partnerships and coordination with local transportation planning districts to support alignment with collective regional objectives. The establishment of these types of partnerships can lead to enhanced technical capabilities and coordination of projects to improve overall success and collective impact.

Responsibilities of Different Personnel

With the integration of flood forecasting capabilities also comes a need for additional skills and responsibilities of personnel to deliver and maintain an effective flood forecasting program. Key responsibilities to support a flood forecasting service include the following:

- Forecast Monitoring. Includes monitoring, reporting, and dissemination of flood forecasts.

- Data Validation. Involves quality assurance of reports and validating forecast predictions with in-situ measurements.

- Sensor Monitoring and Maintenance. Ensures that flood monitoring and sensor equipment used to inform the models is functioning, calibrated, and supplying data.

- Response Coordination. Organizes the appropriate response and preparation based on forecast monitoring.

- Data Management. Includes data scrubbing, standardization, and governance regarding the ingestion of data from multiple sources, including real-time flood sensor feeds.

- Resilience. Incorporates the latest climate science data on future conditions within DOT efforts and coordinates with other state agencies and external partners to support future flood risk mitigation in planning efforts.

While these general responsibilities provide insights into the additional roles and capacity needed to support a flood forecasting service, the specific responsibilities and skill sets will differ across DOTs based on different organizational structures. For instance, flood forecast monitoring duties in emergency management may differ from those in operations. For example, the operations department may use flood forecasting to inform appropriate courses of response action, while the emergency management department may focus more on the execution of response actions. Another example of this can be illustrated in the integration of resilience across the engineering and planning department. The planning department’s role could be to provide various design flood elevations for a given roadway, while the engineering department would seek to develop retrofits and solutions to incorporate the planner’s design.

Integrating these flood forecasting responsibilities will mitigate risk, improve response time during a flooding event, and enhance preparation for future flooding events. DOTs might consider formal training programs to support personnel with these new responsibilities.

Capturing Institutional Knowledge

DOTs may consider succession planning and encourage a cross-training approach to knowledge sharing to help reduce existing information gaps. Cross-training allows multiple staff to learn and develop skill sets to minimize the loss of institutional knowledge from turnover. Staff succession planning will help maintain preestablished efficiencies generated by years of experience.

Institutional knowledge should be documented and shared with relevant team members and other DOTs to encourage best practices. Key information to document and share includes:

- Unique flood risk to the DOT or a region within the state,

- Areas frequently affected by flooding,

- DOT response to and recovery from previous flooding events, and

- Lessons learned from previous flood events.