Transforming the Workforce for Children Birth Through Age 8: A Unifying Foundation (2015)

Chapter: 12 A Blueprint for Action

Children’s development from birth through age 8 is rapid and cumulative, and the environments, supports, and relationships they experience have profound effects. Their health, development, and early learning provide a foundation on which later learning—and lifelong progress—is constructed. Young children thrive and learn best when they have secure, positive relationships with adults who are knowledgeable about how to support their individual progress, and consistency in high-quality care and education experiences as children grow supports their continuous developmental achievements. Thus, the adults who provide for the care and education of young children bear a great responsibility. Indeed, the science of child development and early learning makes clear the importance and complexity of working with children from birth through age 8.

Although they share the same objective—to nurture young children and secure their future success—the various professionals who contribute to the care and education of these children are not perceived as a cohesive workforce, unified by their contributions to the development and early learning of young children and by the shared knowledge base and competencies needed to do their jobs well. An increasing public understanding of the importance of early childhood is reflected by greater emphasis on this age group in policy and investments. Yet the sophistication of the professional roles of those who work with children from infancy through the early elementary years is not consistently recognized and reflected in practices and policies that have not kept pace with what the science of child development and early learning indicates children need.

A growing base of knowledge describes what adults should be doing to

support children from the beginning of their lives. Much is known about how children learn and develop, what professionals who provide care and education for children need to know and be able to do, and what professional learning supports are needed for prospective and practicing care and education professionals. Although that knowledge increasingly informs standards and other statements and frameworks articulating what should be, it is not fully reflected in what is—the current capacities, practices, and policies of the workforce, the settings and systems in which they work, the infrastructure and systems that set qualifications and provide professional learning, and the governmental and other funders that support and oversee those systems. As a result, knowledge is not consistently channeled to adults who are responsible for supporting the development and early learning of children, and those adults do not consistently implement that knowledge in their professional practice and interactions with children. This gap exists in part because current policies and systems do not place enough value on the knowledge and competencies required of professionals in the workforce for children from birth through age 8, and the expectations and conditions of their employment do not adequately reflect their significant contribution to children’s long-term success.

The breakdowns that have led to this gap include the lingering influence of the historical evolution of the expectations and status of various professional roles that entail working with young children; limited mutual understanding, communication, and strategic coordination across decentralized and diverse communities of practice and policy; and limited resources for concerted efforts to review and improve professional learning systems. These disconnects and limitations serve as barriers to both improving how the current workforce is supported and transforming how the workforce needed for the future is prepared.

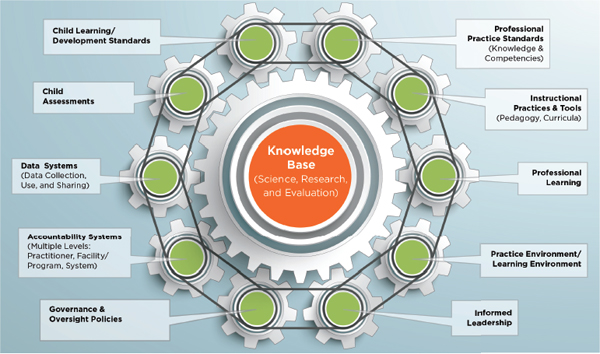

Better support for care and education professionals will require mobilizing local, state, and national leadership; building a culture in higher education and ongoing professional learning that reflects the importance of establishing a cohesive workforce for children from birth through age 8; ensuring practice environments that enable and reinforce the quality of their work; making substantial improvements in working conditions, well-being, compensation, and perceived status or prestige; and creating consistency across local, state, and national systems, policies, and infrastructure. As with multiple sets of complex gears, many interconnected elements need to move together to support a convergent approach to caring for and teaching young children—one that allows for continuity across settings from birth through elementary school, driven by the shared core of the science of child development and early learning (see Figure 12-1).

Yet strengthening the workforce is challenging because the systems, services, and professional roles that contribute to supporting the health,

FIGURE 12-1 Interacting elements of supporting quality professional practice for the care and education of children from birth through age 8.

development, and early learning of children from birth through age 8 are diverse and often decentralized. Those who care for and educate young children work in disparate settings such as homes, childcare centers, preschools, educational programs, and elementary schools. Their work relates directly to those who provide such services as home visiting, early intervention, and special education, and is also closely connected to the work of pediatric health professionals and social services professionals who work with children and families. Oversight and influence are complicated, and achieving coherence is challenging, because the care and education of young children take place in so many different contexts with different practitioner traditions and cultures; funded through multiple governmental and nongovernmental sources; and operating under the management or regulatory oversight of diverse agencies with varying policies, incentives, and constraints.

At the same time, this means that there are many diverse ways to drive changes to strengthen the workforce at the community, state, and national levels. Some opportunities are centralized, such as federally funded programs for early childhood care and education or federal programs that support elementary education. Others are predominantly local, such as public education. Still others are in the private sector, although often subject to state-level regulation, such as childcare centers and family childcare, as well as private elementary schools. Education professionals, the organizations that support and train them, and administrators and leaders can identify and create opportunities for improvement in numerous ways. State and federal policy makers can help by eliminating barriers to a well-qualified professional workforce and to a streamlined and aligned system of services for children from birth through age 8. National organizations outside of government can inform changes by providing guidance and support.

Synchronous changes at all of these levels, and carried out within and across different systems, will require coordinated, strategic systems change in which stakeholders work more collectively and with better, mutually beneficial alignment among policies, resource allocation, infrastructure, professional learning, leadership, and professional practice.

This chapter presents the committee’s recommendations, together with considerations for their implementation, as a blueprint for action that can be taken by stakeholders at the local, state, and national levels to help achieve this systems change and close the gap between what is known and what is done. These recommendations are based on the findings and conclusions, presented in depth in the preceding chapters of this report, that resulted from the committee’s review of evidence, analysis and interpretation, and deliberations.

This blueprint for action is based on a unifying foundation that encompasses essential features of child development and early learning, shared

knowledge and competencies for care and education professionals, and principles for effective professional learning. This foundation is meant to help provide coherence in informing the coordinated change that is needed across systems. Because this will require a collective approach among multiple sectors and a range of stakeholders, the blueprint also offers a framework for collaborative change of this kind.

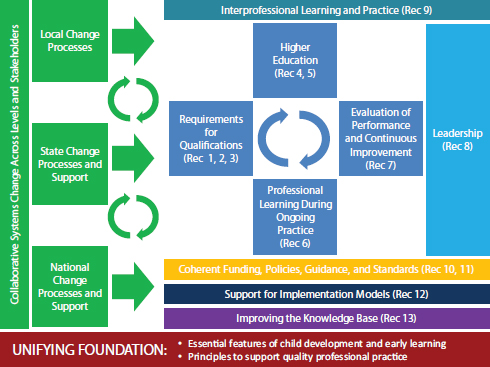

As the core of the blueprint, the committee offers recommendations for specific actions to improve professional learning systems and policies and practices related to the development of the early care and education workforce. Figure 12-2 illustrates how changes in the committee’s major areas of recommendations are interconnected and unified by a shared foundation. The two leftmost circular arrows show how local, state, and national changes need to work in synchronicity, while the central circular arrows show how changes in different aspects of professional learning and workforce development need to work together to lead to quality professional practice, including qualification requirements, higher education, profes-

FIGURE 12-2 A blueprint for action with a unifying foundation, a framework for collaborative systems change, and interrelated recommendations.

sional learning during ongoing practice, and evaluation and assessment of professional practice. Several important elements—including interprofessional practice; well-informed and capable leadership; coherent policies, guidance, and standards; support for implementation; and a connection to the evolving knowledge base—make up a frame for workforce development and professional learning and provide the coherence needed to align specific actions.

The committee recognizes the challenges of the complex, long-term systems change that will be required to implement its recommendations. Full implementation in some cases could take years or even decades; at the same time, the need to improve the quality, continuity, and consistency of professional practice for children from birth through age 8 is urgent. Balancing this reality and this urgent need will require strategic prioritization of immediate actions as well as long-term goals with clearly articulated intermediate steps as part of pathways over time. The pace of progress will depend on the baseline status, existing infrastructure, and political will in different localities. Significant mobilization of resources will be required, and therefore assessments of resource needs, investments from government at all levels and from nongovernmental sources, and financing innovations will all be important.1

The foundation for a workforce that can truly meet the needs of children from birth through age 8 is based on essential features of child development and early learning and on principles that guide support for high-quality professional practice with respect to individual practitioners, leadership, systems, policies, and resource allocation.

_____________

1 While acknowledging that the availability of resources is an important reality that would affect the feasibility of the committee’s recommendations, the sponsors specified in clarifying the study charge that this committee not conduct analyses addressing funding and financing. The sponsors did not want the committee to be swayed by foregone conclusions about the availability of resources in interpreting the evidence and the current state of the field and in carrying out deliberations about its recommendations. The sponsors also recognized that the breadth of expertise required to fulfill this committee’s broad and comprehensive charge precluded assembling a committee with sufficient additional breadth and depth of expertise in economics, costing and resource needs assessment, financing, labor markets, and other relevant areas to address funding and financing issues (public information-gathering session, December 2013).

Essential Features of Child Development and Early Learning

Several essential features of child development and early learning inform not only what children need but also how adults can meet those needs, with support from the systems and policies that define and support their work:

- Children are already learning actively at birth, and the early foundations of learning inform and influence future development and learning continuously as they age.

- A continuous, dynamic interaction among experiences (whether nurturing or adverse), gene expression, and brain development underlies the capacity for learning, beginning before birth and continuing throughout life.

- Young children’s development and early learning encompass cognitive development; the acquisition of subject-matter knowledge and skills; the development of general learning competencies; socioemotional development; and health and physical well-being. Each of these domains is crucial to early learning, and each has specific developmental paths. They also are overlapping and mutually influential: building a child’s competency in one domain supports competency-building in the others.

- Stress and adversity experienced by children can undermine learning and impair socioemotional and physical well-being.

- Secure and responsive relationships with adults (and with other children), coupled with high-quality, positive learning interactions and environments, are foundational for the healthy development of young children. Conversely, adults who are underinformed, under-prepared, or subject to chronic stress themselves may contribute to children’s experiences of adversity and stress and undermine their development and learning.

Principles to Support Quality Professional Practice

The following principles are based on what the science of child development and early learning reveals about the necessary competencies and responsibilities of practitioners in meeting the needs of young children. They encompass the high-quality professional learning and supports needed for practitioners to acquire, sustain, and update those competencies. Yet adults who master competencies can still be constrained in applying them by the circumstances of their settings and by the systems and policies of governance, accountability, and oversight that affect their practice. Thus, the following principles also apply to the characteristics of practice environments,

settings, systems, and policies that are needed to ensure quality practice and to support individual practitioners in exercising their competencies.

For the diverse agencies, institutions, funders, and professionals involved in the care and education of young children, coming together to adopt these principles across sectors, systems, settings, and professional roles will create a shared identity. This identity will be based not on historical traditions or practice settings, but on integrally related and mutually supportive contributions to sustained positive outcomes for the development and early learning of young children. The emergence of this shared identity and unified purpose has the potential to be transformative if accompanied by a willingness to develop shared strategies for investment and to share both responsibility and credit for long-term outcomes.

- Professionals need foundational and specific competencies. Care and education professionals are best able to help young children from birth through age 8 develop and learn when they have a shared foundation of knowledge and competencies related to development and early learning across this age span (see Box 12-1). This foundation needs to be augmented by shared specialized knowledge and competencies within a type of profession (see Box 12-2 for educators and Box 12-3 for education leadership), as well as further differentiated competencies that depend on specialty or discipline and age group.

- Professionals need to be able to support diverse populations. Care and education professionals, with the support of the systems in which they practice, need to be able to respectfully, effectively, and equitably serve children from backgrounds that are diverse with respect to family structure, socioeconomic status, race, ethnicity, culture, language, and ability.

- Professional learning systems need to develop and sustain professional competencies. To foster high-quality practice, care and education professionals need access to high-quality professional learning that supports them in the acquisition and application of the competencies they need, both in degree- and certificate-granting programs and during ongoing practice throughout their career. High-quality professional learning systems encompass a coherent series of activities that prepare professionals for practice, assess and ensure their competency to practice, and enhance the quality of their ongoing professional practice. High-quality professional learning activities are intentional, ongoing, coherent, collaborative and interdisciplinary, tied to practice experience, and responsive (see Box 12-4).

- Practice environments need to enable high-quality practice. Care and education professionals are best able to engage in high-quality professional practice when the settings in which they work are safe and well maintained, provide a high-quality learning environment for children, maintain a reasonable class size and ratio of adults to children for substantial and consistent group and individualized interactions to support learning, are well resourced with materials and supplies, and are guided by informed and competent leadership.

- Practice supports need to facilitate and sustain high-quality practice. Care and education professionals are best able to engage in high-quality professional practice when they experience the support of supervisors, mentors, and a community of peers; regularly assess and reflect on the effectiveness of their practices in order to improve them; are guided by thoughtfully designed workplace and oversight policies that support their practices; are compensated in a manner that recognizes their important role with young children; and have access to and time and resources for ongoing professional learning and career development.

- Systems and policies need to align with the aims of high-quality practice. Children benefit from consistency and continuity in high-quality learning experiences over time. This results when policies are aligned in accord with principles for high quality across the professional roles and settings that provide care and education for different age groups/grade levels, as well as across the sectors that provide closely related services for young children, especially health and social services.

- Professional practice, systems, and polices need to be adaptive. Research will continue to provide new information about how children learn and develop; how adults can best support them; and how adults can best be supported in their professional learning, practice environments, and practice supports. Accordingly, the systems that support children, the professionals who work within them, and their professional learning systems all need to adapt iteratively, with evaluative components that are embedded in continuous improvement processes.

BOX 12-1

Foundational Knowledge and Competencies for All Adults with Professional Responsibilities for Young Children

The committee identifies the following general knowledge and competencies as an important foundation for all adults with professional responsibilities for young children.

All adults with professional responsibilities for young children need to know about

- How a child develops and learns, including cognitive development, specific content knowledge and skills, general learning competencies, socioemotional development, and physical development and health.

- The importance of consistent, stable, nurturing, and protective relationships that support development and learning across domains and enable children to fully engage in learning opportunities.

- Biological and environmental factors that can contribute positively to or interfere with development, behavior, and learning (for example, positive and ameliorative effects of nurturing and responsive relationships, negative effects of chronic stress and exposure to trauma and adverse events; positive adaptations to environmental exposures).

All adults with professional responsibilities for young children need to use this knowledge and develop the skills to

- Engage effectively in quality interactions with children that foster healthy child development and learning in routine everyday interactions, in specific learning activities, and in educational and other professional settings in a manner appropriate to the child’s developmental level.

- Promote positive social development and behaviors and mitigate challenging behaviors.

- Recognize signs that children may need to be assessed and referred for specialized services (for example, for developmental delays, mental health concerns, social support needs, or abuse and neglect); and be aware of how to access the information, resources, and support for such specialized help when needed.

- Make informed decisions about whether and how to use different kinds of technologies as tools to promote children’s learning.

BOX 12-2

Knowledge and Competencies for Educators of Children Birth Through Age 8

In addition to the foundational knowledge and competencies in Box 12-1, the committee identifies the following as important shared competencies that all professionals who provide direct, regular care and education for young children need to support development and foster early learning with consistency for children on the birth through age 8 continuum.

Core Knowledge Base

- Knowledge of the developmental science that underlies important domains of early learning and child development, including cognitive development, specific content knowledge and skills, general learning competencies, socioemotional development, and physical development and health.

- Knowledge of how these domains interact to facilitate learning and development.

- Knowledge of content and concepts that are important in early learning of major subject-matter areas, including language and literacy, mathematics, science, technology, engineering, arts, and social studies.

- Knowledge of the learning trajectories (goals, developmental progressions, and instructional tasks and strategies) of how children learn and become proficient in each of the domains and specific subject-matter areas.

- Knowledge of the science that elucidates the interactions among biological and environmental factors that influence children’s development and learning, including the positive effects of consistent, nurturing interactions that facilitate development and learning as well as the negative effects of chronic stress and exposure to trauma and adversity that can impede development and learning.

- Knowledge of the principles for assessing children that are developmentally appropriate; culturally sensitive; and relevant, reliable, and valid across a variety of populations, domains, and assessment purposes.

Practices to Help Children Learn

- Ability to establish relationships and interactions with children that are nurturing and use positive language.

- Ability to create and manage effective learning environments (physical space, materials, activities, classroom management).

- Ability to consistently deploy productive routines, maintain a schedule, and make transitions brief and productive, all to increase predictability and learning opportunities and to maintain a sense of emotional calm in the learning environment.

- Ability to use a repertory of instructional and caregiving practices and strategies, including implementing validated curricula, that engage children through nurturing, responsive interactions and facilitate learning and

-

development in all domains in ways that are appropriate for their stage of development.

- Ability to set appropriate individualized goals and objectives to advance young children’s development and learning.

- Ability to use learning trajectories: A deep understanding of the subject, knowledge of the way children think and learn about the subject, and the ability to design and employ instructional tasks, curricula, and activities that effectively promote learning and development within and across domains and subject-matter areas.

- Ability to select, employ, and interpret a portfolio of both informal and formal assessment tools and strategies; to use the results to understand individual children’s developmental progression and determine whether needs are being met; and to use this information to individualize, adapt, and improve instructional practices.

- Ability to integrate and leverage different kinds of technologies in curricula and instructional practice to promote children’s learning.

- Ability to promote positive social development and self-regulation while mitigating challenging behaviors in ways that reflect an understanding of the multiple biological and environmental factors that affect behavior.

- Ability to recognize the effects of factors from outside the practice setting (e.g., poverty, trauma, parental depression, experience of violence in the home or community) that affect children’s learning and development, and to adjust practice to help children experiencing those effects.

Working with Diverse Populations of Children

- Ability to advance the learning and development of children from backgrounds that are diverse in family structure, socioeconomic status, race, ethnicity, culture, and language.

- Ability to advance the learning and development of children who are dual language learners.

- Ability to advance the development and learning of children who have specialized developmental or learning needs, such as children with disabilities or learning delays, children experiencing chronic stress/adversity, and children who are gifted and talented. All early care and education professionals—not just those in specialized roles—need knowledge and basic competencies for working with these children.

Developing and Using Partnerships

- Ability to communicate and connect with families in a mutually respectful, reciprocal way, and to set goals with families and prepare them to engage in complementary behaviors and activities that enhance development and early learning.

- Ability to recognize when behaviors and academic challenges may be a sign of an underlying need for referral for more comprehensive assessment, diagnosis, and support (e.g., mental health consultation, social services, family support services).

- Knowledge of professional roles and available services within care and education and in closely related sectors such as health and social services.

- Ability to access and effectively use available referral and resource systems.

- Ability to collaborate and communicate with professionals in other roles, disciplines, and sectors to facilitate mutual understanding and collective contribution to improving outcomes for children.

Continuously Improving Quality of Practice

- Ability and motivation to access and engage in available professional learning resources to keep current with the science of development and early learning and with research on instructional and other practices.

- Knowledge and abilities for self-care to manage their own physical and mental health, including the effects of their own exposure to adversity and stress.

Comparison to National and State Statements of Core Competencies

A scan across national and state statements of core competencies for educators suggests that there is broad agreement on what educators who work with children from infancy through age 8 need to know and be able to do.a However, there are variations in emphasis and gaps. Organizations and states that issue statements of core competencies for these educators would benefit from a review aimed at improving consistency in family engagement and assessment and enhancing their statements to reflect recent research on how children learn and develop and the role of educators in the process. Areas likely in need of enhancement in many existing statements include teaching subject matter–specific content, addressing stress and adversity, fostering socioemotional development, promoting general learning competencies, working with dual language learners, and integrating technology into curricula.

_____________

a See Chapter 7 for an in-depth discussion of the example competency statements.

BOX 12-3

Knowledge and Competencies for Leadership in Settings with Children Birth Through Age 8

In addition to the foundational knowledge and competencies in Box 12-1, center directors, childcare owners, principals, and other leaders and administrators who oversee care and education settings for young children birth through age 8 need both specific competencies and overlapping general competencies with the roles of the specific professionals they supervise. The committee identifies the following important competencies that are needed by these leaders across settings:

Practices to Help Children Learn

- Understanding the implications of child development and early learning for interactions of care and education professionals with children, instructional and other practices, and learning environments.

- Ability to keep current with how advances in the research on child development and early learning and on instructional and other practices inform changes in professional practices and learning environments.

Assessment of Children

- Knowledge of assessment principles and methods to monitor children’s progress and ability to adjust practice accordingly.

- Ability to select assessment tools for use by the professionals in their setting.

Fostering a Professional Workforce

- Knowledge and understanding of the competencies needed to work with children in the professional setting they lead.

- Ability to use knowledge of these competencies to make informed decisions about hiring and placement of practitioners.

- Ability to formulate and implement policies that create an environment that enhances and supports quality practice and children’s development and early learning.

- Ability to formulate and implement supportive and rigorous ongoing professional learning opportunities and quality improvement programs that reflect current knowledge of child development and of effective, high-quality instructional and other practices.

- Ability to foster the health and well-being of their staff and seek out and provide resources for staff to manage stress.

Assessment of Educators

- Ability to assess quality of instruction and interactions, to recognize high quality, and to identify and address poor quality through evalua-

-

tion systems, observations, coaching, and other professional learning opportunities.

- Ability to use data from assessments of care and education professionals appropriately and effectively to make adjustments to improve outcomes for children and to inform professional learning and other decisions and policies.

Developing and Fostering Partnerships

- Ability to support collaboration among the different kinds of providers under their leadership.

- Ability to enable interprofessional opportunities for themselves and their staff to facilitate linkages among health, education, social services, and other disciplines not under their direct leadership.

- Ability to work with families and support their staff to work with families.

Organizational Development and Management

- Knowledge and ability in administrative and fiscal management, compliance with laws and regulations, and the development and maintenance of infrastructure and an appropriate work environment.

Comparison to Statements of Leadership Competencies

A review of examples of statements of core competencies from early childhood organizations and elementary education leadership organizations suggests that there is a distinction in the stated expectations for these two categories of leaders whose professional roles fall within the birth through age 8 range.a Those for principals include competencies for organizational management but are mainly focused on knowledge and competencies needed for instructional leadership to create working environments and supports for educators that help them improve their instructional practice. Those representing leaders in early childhood settings focus on how well a leader can develop and manage a well-functioning organization.

To create a more consistent culture of leadership expectations better aligned with children’s need for continuous learning experiences, states’ and organizations’ statements of core competencies for leadership in elementary education would benefit from a review of those statements to ensure that the scope of competencies for instructional leadership encompasses the early elementary years, including prekindergarten as it increasingly becomes included in public school systems. States and organizations that issue statements of core competencies for leadership in centers, programs, family childcare, and other settings for early childhood education would benefit from a review of those statements to ensure that competencies related to instructional leadership are emphasized alongside administrative and management competencies.

_____________

a See Chapter 7 for an in-depth discussion of the example competency statements.

BOX 12-4

Principles for Professional Learning Systems

A high-quality professional learning system provides practitioners with coherent, interrelated, and continuous professional learning activities and mechanisms that are aligned with each other and with the science of child development. These activities and mechanisms need to be sequenced to prepare practitioners for practice, assess and ensure their competency to practice, continuously enhance the quality of their ongoing professional practice throughout their career, and provide opportunities for career development and advancement. High-quality professional learning activities and mechanisms have the following characteristics:

Intentional

- Guided by the available science on child development and early learning, instructional and other practices, and adult learning.

- Guided by alignment between the developmental needs of children and professional learning needs for acquiring and sustaining core competencies and professional practice standards.

- Guided by the context of the diverse settings in which professionals might practice and the diverse populations of children and families with whom they might work.

Ongoing

- Designed to support cumulative and continuous learning over time, with preparation experience that leads to a period of supervised practice, followed by independent practice with ongoing, individualized supports from supervisors, coaches, mentors, and/or peers.

Coherent

- Coherent in the types and sequence of professional learning to which individual practitioners have access and in which they engage to support a continuum of growth, as opposed to discrete, potentially disjointed learning experiences.

- Coherent and aligned with a shared foundation of knowledge of child development across professional roles.

A FRAMEWORK FOR COLLABORATIVE SYSTEMS CHANGE

The collective insight, expertise, and action of multiple stakeholders are needed to guide the implementation of changes to policies and systems that affect workforce development across settings and roles involved in the care and education of children from birth through age 8. Important work related to the principles and recommendations in this report is currently being carried out by many strong organizations. However, much of this work is being done in relative isolation or as part of collaborations that are not comprehensive in encompassing all that is needed to support de-

- Coherent and comprehensive in what professional learning is available in a given local system.

- Coherent and aligned in content and aims across the full breadth of supports and mechanisms that contribute to improving professional practice, including higher education, ongoing professional learning, the practice environment, opportunities for professional advancement, systems for evaluation and support for ongoing quality improvement, and supports for the status and well-being of the workforce.

- Coherent and coordinated with respect to professional learning activities for professional roles across practice settings and age ranges within the birth through age 8 span.

Collaborative and Interdisciplinary

- Based on an ethic of shared responsibility and collective practice for promoting child development and early learning.

- Providing shared professional learning opportunities for professional roles across practice settings and age ranges within the birth through age 8 span (e.g., cross-disciplinary courses and professional learning communities).

- Leveraging collaborative learning models (e.g., peer-to-peer learning and cohort models).

Tied to Practice

- Designed to provide field experiences and/or to tie didactic learning to applied practice experience with ongoing, individualized feedback and support.

Responsive

- Designed to take into account variations in entry points and sequencing for accessing professional learning.

- Designed to take into account career stage, from novice to experienced.

- Designed to take into account challenges faced by practitioners with respect to accessibility, affordability, scheduling/time/logistics constraints, baseline skills, and perceptions about professional learning activities and systems.

velopment and early learning for these young children. This existing work can be leveraged to accomplish more effective, widespread, and lasting change if knowledge and expertise are shared and efforts are coordinated through a more comprehensive framework. The persistently diffuse nature of the many systems and organizations that serve these children calls for approaches that are more collaborative and inclusive, and many of the committee’s recommendations rely on a collective approach of this kind.

Drawing on the unifying foundation presented in the preceding section and best practices for collaborative approaches to systems change,

BOX 12-5

Features of Collaborative Systems Change for the Birth Through Age 8 Workforce

All systems change efforts are grounded in professional competencies for child development and early learning.

Collective efforts need to be guided by the science of child development and early learning and aligned with the core competencies for care and education professionals outlined in Boxes 12-2 and 12-3 and with the principles for professional learning listed in Box 12-4. Therefore, an important part of the formative work for agencies and organizations involved in supporting children from birth through age 8 at the national, state, and local levels is to assess and revise as needed any current statements of professional competencies for both practitioners and leaders, and to review the extent to which all professional learning and workforce development opportunities, policies, and supports are informed by and aligned with those competencies.

A comprehensive view of the workforce is taken across professional roles, settings, and age ranges.

Attention to the workforce for early childhood education often centers on the preschool years, and discussion of improving continuity often focuses on children entering kindergarten. This focus is due in part to the relative strength of central oversight for publicly funded or subsidized preschools through Head Start and the emergence of preschool as part of public elementary school systems. Attention to these settings and age ranges continues to be important, but to be successful, collective efforts need to place similar emphasis along the full birth through age 8 range and across professional roles and settings. In particular, concerted attention is needed to incorporate into these efforts the workforce development needs of those who provide care and education for infants and toddlers. These professionals have historically had the weakest, least explicit and coherent, and least resourced infrastructure for professional learning and workforce supports. Practitioners in settings outside of centers and schools, such as family childcare, have historically had even less infrastructure for professional learning and workforce supports. A critical role of these collective efforts, then, is to create this much-needed infrastructure for these professionals. At the other end of the age spectrum, concerted attention is also needed to incorporate educators and other professional roles in early elementary schools. For them, professional learning is already supported through a more explicit and robust infrastructure. However, the practices entailed in educating the youngest elementary students can be insufficiently emphasized in the context of the broader K-12 professional learning systems that incline toward the education of older children. The collective efforts envisioned by the committee therefore need to inform and improve this existing infrastructure.

A comprehensive view is taken of professional learning and factors that affect professional practice.

A number of factors contribute to workforce development and to quality professional practice for both practitioners and leaders. Higher education programs, mentoring and coaching, and in-service professional development are all important mechanisms for developing and sustaining the knowledge and competencies of professionals. Other elements not always treated as an integrated part of professional learning, such as agencies that regulate licensure and credentialing systems and program quality assurance systems, also can contribute directly to the quality of professional practice. All of these elements need to be represented in collaborative efforts to develop a comprehensive and more coordinated system of professional learning so that goals are aligned across the elements, and each contributes to systems that are better coordinated and less disparate. Other factors also are important and are influenced or controlled by stakeholders other than the professionals themselves or the systems that provide their education and training. These include the practice environment, such as staffing structures, working conditions, and staff-to-child ratios; the availability of supplies, instructional materials, and other resources; the policies that affect professional requirements, opportunities for professional advancement, and assessment systems; and the status and well-being of the workforce, such as incentives that attract and retain these professionals, perceptions of care and education professions, compensation, and stressors and the availability of supportive services to help manage them. To achieve the ultimate aim of ensuring sustained systems change, it is important to see these factors as working collectively and to engage stakeholders with influence across these various elements.

Diverse stakeholders are engaged in collaborative efforts.

In addition to comprehensive representation of practice communities across professional roles, settings, and age ranges as described above, engaging diverse stakeholders means representing the multiple relevant disciplines in the research community, policy research and analysis, policy makers and government leadership, higher education, agencies that oversee licensure and credentialing as well as accreditation, and organizations that provide ongoing professional learning. For some areas of action, it may also be important to collaborate or consult with organizations whose mission relates to the professionals who work with children and families in the closely related sectors of health and social services, as well as with organizations that represent family perspectives.

In addition, the workforce itself and the children and families it serves represent a racially, ethnically, linguistically, and socioeconomically diverse population. The entities that assume responsibility and leadership for changes that will affect them need to ensure that this diversity is considered and reflected in their decision making and actions and to include perspectives from individuals that reflect a similar diversity. Similarly, circumstances vary widely in different localities, which makes geographic diversity another important dimension to consider, especially

for national coordination efforts or for state efforts in states with a wide range of local contexts.

Context matters.

The steps needed for change will depend on factors that are specific to the context of different state and local environments, and different strategies and timelines will be needed accordingly. Different localities will have different strengths and different gaps in their professional learning infrastructure at the outset, and the amount and sources of their financial and other resources will vary. Education levels in the population and the labor market also will vary, which affects the supply and demand characteristics of both the current workforce and the pipeline for the potential future workforce. Solutions may vary as well according to population density and the availability and accessibility of services and institutions.

A backbone infrastructure is established.

A key factor in the success and sustainability of collaborative efforts is having some form of backbone infrastructure. The role of a backbone organization is to convene the various stakeholders; to maintain and refine the collaborative strategy; and to facilitate, coordinate, and monitor the progress of collaborative efforts. There currently exists no such backbone organization to represent workforce development comprehensively across professional roles, settings, and age ranges entailed in care and education for children from birth through age 8.

One approach would be to create a new backbone organization to facilitate collective efforts, such as a new coalition at the national, state, or local level. Such a backbone organization could provide sustainable leadership for the change process—a challenge for diverse stakeholders that each are understandably driven by their own priorities based on the oversight mechanisms and incentive structures that inform their routine responsibilities and functioning. However, forming a new organization would require significant financial resources. Another approach would be for an existing organization to assume the leadership role in facilitating the collaborative change process. This approach would not eliminate the resource requirement, but would limit the need for investment in new organizational infrastructure. With this approach, however, the direction of collective efforts could be drawn toward the core priorities of the lead organization, which also could lack credibility or have difficulty gaining the confidence of other sectors or disciplinary perspectives. Therefore, the lead organization would need to commit to inclusivity and neutrality. For example, a lead organization whose primary or historical focus was early childhood education would need to commit to being inclusive of early elementary perspectives and stakeholders. Similarly, a lead organization typically focused on higher education would need to commit to being inclusive of other components that contribute to ongoing professional learning.

A smaller-scale alternative to a full-scale collaborative initiative would be to establish periodic convenings and other mechanisms for communication among stakeholders doing related work. This approach would require fewer resources,

but might also be less likely to lead to concrete collaborative actions and might be difficult to sustain.

One way individual organizations could enhance their commitment to ongoing collaboration and inclusivity would be to broaden their internal guidance and oversight mechanisms, such as their boards of directors or advisory committees, to include expertise and representation across the birth through age 8 continuum, even if their core mission is related to a subset of roles, age ranges, or settings. Doing so would reinforce the importance of aligning across professional roles and settings, facilitate communication with collaborative partners, and hold the organization accountable for a commitment to an inclusive and collaborative approach.

Another important aspect of coordinated systems change is that not every action taken to improve professional learning and workforce development will require the collective action of all stakeholders. Some actions will be specific to a subset of professional roles, such as infant-toddler specialists, early elementary teachers, Head Start center directors, or mental health consultants. Some actions can be taken at the level of smaller collaborations or at the level of institutions or even individuals. But through the facilitation of a backbone infrastructure, these cascading levels of implementation can be linked to contribute to the ultimate common agenda so that each aspect of professional practice strengthens and is improved by advances in other aspects.

Duplication of effort is avoided.

Collaborative systems change will be most effective when it draws on available resources, frameworks, and guidance and builds on any collaborative efforts already under way—engaging established organizations and leveraging current efforts to avoid creating entirely new infrastructure and solutions. In some cases, existing national-, state-, or community-level efforts already cover some elements of the comprehensive systems change that is needed. For example, many states and communities already have early learning councils or coalitions or similar organizations. Implementation of this report’s recommendations can serve to inform and reinforce the importance of those efforts, to strengthen their infrastructure and resources, and to catalyze a more comprehensive approach. Where coalitions have not yet been formed, local communities can learn from the experiences of other communities that share similar characteristics.

To avoid unnecessary duplication while also more effectively supporting consistency and continuity for children from birth through age 8, existing coalitions could benefit from reviewing their efforts in light of the principles put forth in this report, the specific actions laid out in the recommendations and implementation considerations that follow in this chapter, and the scope of their current coalition partners. For example, are current early learning coalitions focused on workforce development and professional learning? Are they adequately inclusive of both early childhood and early elementary settings? Are current collaborative efforts that focus primarily on services for children inclusive of what is needed to support the adults who work with children? Are these collaborative efforts reaching out to collaborate and coordinate with the health and social services sectors?

Box 12-5 provides a framework for collaborative systems change consisting of features that are key to improving workforce development for care and education professionals who work with children from birth through age 8. In brief, for collaborative change to achieve lasting success it is important to be inclusive in recruiting stakeholders who need to be involved; to establish a backbone infrastructure; to conduct an assessment of baseline capacities, activities, and needs; and to develop a common agenda, mutually reinforcing activities, continuous communication, and a shared measurement approach that can be applied to track progress and course correct as needed.

Appendix F provides examples of references, tools, and resources for best practices in implementing collaborative systems change as a process in general and in particular for early care and education. Examples are also provided of existing initiatives using collaborative approaches; additional examples can be found in the discussion of continuity in Chapter 5 (see Boxes 5-1 and 5-2). The tools and resources described do not represent a comprehensive review, and the committee did not draw conclusions to endorse particular exemplars. Rather, these examples are provided as a prompt to explore available options and resources that can assist in collaborative systems change efforts.

The committee’s recommendations to improve professional learning and policies and practices related to the development of the workforce that provide care and education for children from birth through age 8 address the following key areas: qualification requirements for professional practice (Recommendations 1-3), higher education (Recommendations 4 and 5), professional learning during ongoing practice (Recommendation 6), evaluation and assessment of professional practice (Recommendation 7), the critical role of leadership (Recommendation 8), interprofessional practice (Recommendation 9), support for implementation (Recommendations 10-12), and improving the knowledge base to inform professional learning and workforce development (Recommendation 13). Considerations for implementing these recommendations are highlighted throughout.

Qualification Requirements for Professional Practice

All care and education professionals have a similarly complex and challenging scope of work. However, this fact is not consistently reflected in practices and policies regarding requirements for qualification to practice. Instead the requirements and expectations for educators of children from birth through age 8 vary widely for different professionals based on their role, the ages of the children with whom they work, their practice setting, and what agency or institution has jurisdiction or authority for set-

ting qualification criteria. The result is a mix of legally required licensure qualifications and voluntary certificates, endorsements, and credentials that employers may adopt as requirements or professionals may pursue to augment and document their qualifications.

These different standards for qualification, which often are based more on historical professional traditions or what systems can afford than on what children need, drive differences among professional roles in terms of professional learning, hiring prospects, and career pathways—and ultimately can lead to significant variations in knowledge and competencies and in the quality of professional practice in different settings. This lack of consistency is dissonant with what the science of early learning reveals about the foundational core competencies that all care and education professionals need and the importance of consistency in learning experiences for children in this age range. Greater coherence in qualification requirements across professional roles would improve the consistency and continuity of high-quality learning experiences for children from birth through age 8.

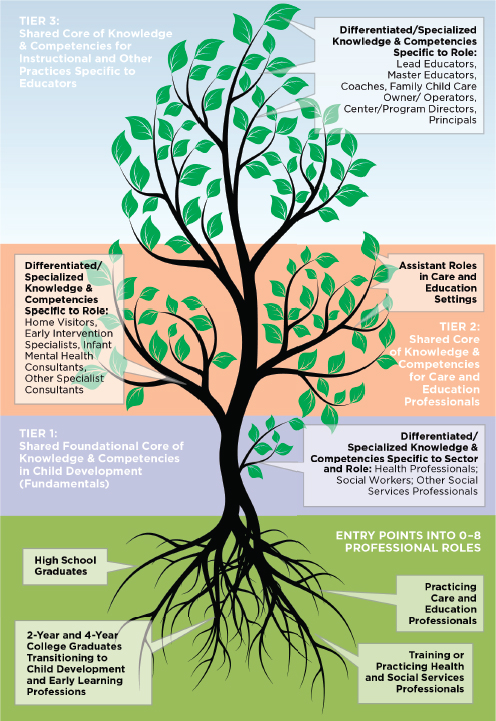

The analogy of a tree is a useful way to characterize the currently diffuse landscape of professional roles in a more coherent way, with both shared and specialized standards for knowledge and competencies (see Figure 12-3). The tree has roots that represent how individuals enter into a role working with young children in different ways with different preexisting qualifications, yet all need access to learning supports to achieve a shared foundation of knowledge and competencies. The trunk represents that shared foundation, from which branches extend to represent the specialized knowledge and competencies needed as individuals pursue differentiated professional roles. As the branches extend, they reflect further differentiation into specialized roles, as well as progression from novice to experienced, including potential advanced education and certification. Even as these roles differentiate, they also need to maintain connections to and alignment with each other to support continuity of care and education and linkages to professionals in other sectors.

A tiered trunk represents first the child development fundamentals that everyone working with children should have (tier 1 in Figure 12-3; see also Box 12-1 earlier in this chapter). From this lower tier as a foundation, professionals in health and social services branch off to their own specific professional qualifications, which both encompass and extend beyond the birth through age 8 range. The middle tier of the trunk represents a core of qualifications related to fostering development and learning that are shared across all professional roles within the care and education sector (tier 2 in Figure 12-3). From this tier extend branches for specialist and consultant professionals who see children for periodic or referral services, such as home visitors, early intervention specialists, and mental health consultants, and who in addition have existing qualification systems specific to their

FIGURE 12-3 Tiered representation of shared and specialized standards for knowledge and competencies of professionals who work with young children.

roles. This core is shared with those professionals who are responsible for regular, daily care and education of children from birth through age 8. Branches also extend from this core for closely supervised assistant roles in care education settings, such as aides and assistant teachers. For other roles, the trunk first extends to another tier with a more specialized set of shared knowledge and competencies related to instructional and other practices that foster development and early learning (tier 3 in Figure 12-3; see also Boxes 12-2 and 12-3 earlier in this chapter). This tier represents those responsible for planning and implementing activities and instruction or those in a leadership position overseeing the professionals who plan and implement instruction, such as the lead educator in classroom settings, the owner/operator in family childcare, the center director/program director, and the principal and assistant principal in schools that include early elementary students. The branches that extend from this trunk represent differentiated competencies and practice experience relevant and specific to subsets within the birth through age 8 continuum of settings; age ranges; roles; and content, subject matter, or other specialization.

Recommendation 1: Strengthen competency-based qualification requirements for all care and education professionals working with children from birth through age 8.

Government agencies2 and nongovernmental resource organizations3 at the national, state, and local levels should review their standards and policies for workforce qualification requirements and revise them as needed to ensure they are competency based for all care and education professionals. These requirements should be consistently aligned with the principles delineated in this report to reflect foundational knowledge and competencies shared across professional roles working with children from birth through age 8, as well as specific and differentiated knowledge and competencies matched to the practice needs and expectations for specific roles.

_____________

2 Government agencies when referred to in this report, whether national (federal), state, and/or local, include those with responsibilities for education (early childhood, elementary, higher education), health and human services, social welfare, and labor, as well as elected officials in executive offices and legislatures.

3 Nongovernmental resource organizations when referred to in this report include those that provide funding, technical assistance, voluntary oversight mechanisms, and research and policy guidance, such as philanthropic and corporate funders, national professional associations for practitioners and leadership, unions, research institutions, policy and advocacy organizations, associations that represent institutions of higher education, and associations that represent providers of professional learning outside of higher education.

The current requirements and expectations for educators of children from birth through age 8 vary widely not only for different professional roles but also by what agency or institution has jurisdiction or authority for setting qualification criteria. Differing standards for qualification drive differences among professional roles in terms of education, training, and infrastructure for professional learning during ongoing practice, and hence differences in knowledge and competencies in different settings.

A review process guided by mutual alignment with the principles set forth in this report across agencies and organizations and across the national, state, and local levels would lay the groundwork for greater coherence in the content of and processes for qualification requirements, such as those for credentialing and licensure. As a result, even when different systems or localities have policies that are organized differently by age ranges and roles, those policies could still work in concert to foster quality practice across professional roles and settings that support more consistent high-quality learning experiences for children from birth through age 8. The scan of example competency statements in Chapter 7, summarized previously in Boxes 12-2 and 12-3, highlights areas likely to be most in need of review in policies for licensure and credentialing.

At the national level, for example, multiple federal programs provide funding, technical assistance, and other support for young children. Examples include the Maternal and Child Health Services Block Grant Program; the Child Care and Development Fund; Head Start/Early Head Start; Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Programs; Preschool Development Grants; Race to the Top funds; and grants through the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act and the Elementary and Secondary Education Act. An effort among the agencies responsible for these programs to use the principles of this report to review and revise expectations for the qualifications of the workforce hired using federal funds would contribute to greater consistency and quality in the experiences that affect the development and early learning of young children. A similar review by national nongovernmental credentialing systems, such as the Child Development Associate (CDA) and National Board for Professional Teaching Standards (NBPTS), would likewise yield opportunities for revisions to optimize continuity for children without disrupting existing specialized and differentiated credentialing systems.

At the state level, there is wide variation in licensure, and licensure commonly has overlap within the birth through age 8 continuum. Review processes within states—driven by mutual alignment with the principles laid out in this report—would ensure that professional practice expectations are more widely in keeping with the science of child development and early learning and more consistent across professional roles and from state to state.

Recommendation 2: Develop and implement comprehensive pathways and multiyear timelines at the individual, institutional, and policy levels for transitioning to a minimum bachelor’s degree qualification requirement, with specialized knowledge and competencies, for all lead educators4 working with children from birth through age 8.

Currently, most lead educators in care and education settings prior to elementary school are not expected to have the same level of education—a bachelor’s degree—as teachers leading elementary school classrooms. A transition to a minimum bachelor’s degree requirement for all lead educators—if implemented through a comprehensive approach alongside other related changes—is likely to contribute to improving the quality of professional practice, creating coherence in qualification systems such as credentialing and licensure, stabilizing the workforce, and improving consistency in high-quality learning experiences and optimal outcomes for children from birth through age 8.

Recommendation 2a: State leadership and licensure and accreditation agencies, state and local stakeholders in care and education, and institutions of higher education should collaboratively develop a multiyear, phased, multicomponent, coordinated strategy to set the expectation that lead educators who support the development and early learning of children from birth through age 8 should have at a minimum a bachelor’s degree and specialization in the knowledge and competencies needed to serve as a care and education professional. This strategy should include an implementation plan tailored to local circumstances with coordinated pathways and timelines for changes at the individual, institutional, and policy levels.

Recommendation 2b: Federal government agencies and nongovernmental resource organizations should align their policies with a multiyear, phased strategy for instituting a minimum bachelor’s degree requirement. They should develop incentives and dedicate resources from existing and new funding streams and technical assistance programs to support individual, institutional, systems, and policy pathways for meeting this requirement in states and local communities.

_____________

4 Lead educators are those who bear primary responsibility for children and are responsible for planning and implementing activities and instruction and overseeing the work of assistant teachers and paraprofessionals. They include the lead educator in classroom and center-based settings, center directors/administrators, and owner/operators and lead practitioners in home-based or family childcare settings (tier 3 in Figure 12-3).

Policy decisions about qualification requirements are complex, as is the relationship among level of education, high-quality professional practice, and outcomes for children. Given that empirical evidence about the effects of a bachelor’s degree is inconclusive, a decision to maintain the status quo and a decision to transition to a higher level of education as a minimum requirement entail similar uncertainty and as great a potential consequence for outcomes for children. In the absence of conclusive empirical evidence, the committee draws on its collective expert judgment to make this recommendation on the following grounds:

- Existing research on this question has important limitations and has produced mixed findings, and as a result it does not provide conclusive guidance. The research does not discount the potential that a high-quality college education can better equip educators with the sophisticated knowledge and competencies needed to deliver high-quality educational practices that are associated with better child outcomes at all ages.

- Holding lower educational expectations for early childhood educators than for elementary school educators perpetuates the perception that educating children before kindergarten requires less expertise than educating K-3 students, which helps to justify policies that make it difficult to maximize the potential of young children and the early learning programs that serve them.

- Disparate degree requirement policies create a bifurcated job market, both between elementary schools and early care and education as well as within early care and education as a result of degree requirements in Head Start and other settings as well as publicly funded prekindergarten programs. Educators who are more able to seek higher education, continue their professional growth, and acquire credentials that qualify them for better-compensated positions leave programs that serve young children and work in schools with older children, or leave less well-resourced preschool and childcare settings for young children for better resourced ones. This situation potentially perpetuates a cycle of disparity in the quality of the learning experiences of young children.

- The current differences in expectations across professional roles are largely an artifact of the historical traditions and perceived value of these jobs, as well as the limited resources available to the care and education sector, rather than being based on the needs of children. These expectations lag behind the science of child development and early learning, which shows clearly that the experiences of children in the earliest years—including their interactions with care

-

and education professionals—have profound effects, building the foundation for lifelong development and learning.

- The high level of complex knowledge and competencies that the science of child development and early learning indicates is necessary for educators working with young children of all ages is a strong rationale for equal footing among those who share similar lead educator roles and responsibilities for children. Few would argue, for example, that current expectations for early elementary school teachers should be lowered, and if the work of lead educators for younger children is based on the same science of child development and early learning and the same foundational competencies, it follows that they should be expected to have the same level of education.

- Greater consistency in the minimum educational expectations for similar professional roles regardless of the age of the child will bring the care and education sector in line with other sectors, which do not vary in minimum expectations based on the age of the child. For example, neonatologists and physicians who work with older children have the same minimum education requirement, and the minimum education requirement is the same for social workers who work with young children and their families and those who work with elementary-age children and their families.

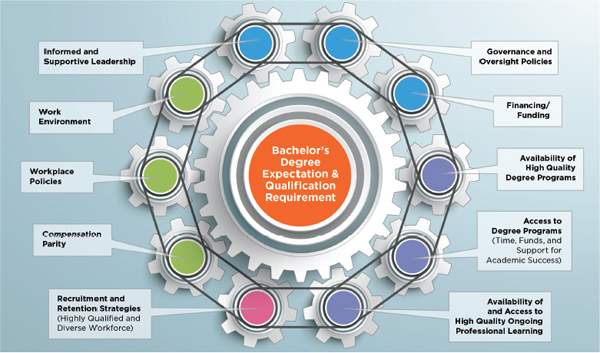

The committee is cognizant of the complex issues that accompany a minimum degree requirement. Most important for this recommendation is that simply instituting policies requiring a minimum bachelor’s degree is not sufficient, and this recommendation is closely interconnected with those that follow. A more consistent bachelor’s degree requirement will be feasible and its potential benefits will be realized only if it is implemented carefully over time in the context of efforts to address other interrelated factors and with supportive federal, state, and local policies and informed, supportive leadership. These multiple factors, to return to the metaphor used earlier, are like interconnected gears that will not function if moved in isolation (see Figure 12-4). Therefore, strategies and implementation plans should include

- Pathways and timelines for lead educators, differentiated by individual needs, to acquire the necessary education in child development and early learning. Considerations should include

- – differentiation between pathways for current professionals with practice experience and those for the pipeline of prospective future professionals entering the field;

FIGURE 12-4 Interrelated components involved in implementing a minimum bachelor’s degree requirement.

-

- – strategies for improving the affordability of higher education programs by mitigating the financial burden of obtaining a degree through, for example, scholarships, tuition subsidies, tuition reimbursement as a benefit of employment, loans for degree-granting programs, and loan forgiveness for care and education professionals who work in underresourced programs; – strategies for improving the feasibility of accessing higher education programs, such as providing adequate time in work schedules and other ways to give those who need to maintain full-time income opportunities to complete degree programs;

- – strategies to provide academic supports that bolster baseline competencies for prospective educators to enter and succeed in college programs; and

- – adaptive considerations for potential evolution in the nature and format of higher education degree and credentialing systems, including potential future alternative equivalents to the bachelor’s degree—as long as the same general level of education is ensured and is accompanied by the specialized education and training in the knowledge and competencies needed to serve as an educator of young children. Such evolution in higher education might derive from the use of remote courses and other technology-driven changes as well as explorations of competency-based fulfillment of degree requirements.

- Pathways and timelines for higher education institutions to

- – improve the quality of specialized training related to practices that foster child development and early learning;

- – build the capacity to absorb the number of students who will need access to those programs; and

- – recruit a pool of educators-in-training that reflects the diversity of the children and communities they serve.

- Pathways and timelines for systems and policy changes to licensure and credentialing.

- Pathways and timelines for systems and policy changes to effect parity in compensation across professional roles within the care and education sector; in workplace policies; and in workplace environments and working conditions, including adequately resourced and high-quality learning environments in practice settings.

- Pathways and timelines to improve the availability, accessibility, and quality of professional learning during ongoing practice. This professional learning should encompass specialized training related to knowledge and competencies needed to engage in instructional

-

and other practices that foster childhood development and early learning, following the principles laid out earlier.

- Assessments of resource needs, followed by resource mobilization plans and innovative financing strategies such as scholarships and stipends for individuals, subsidies for higher education programs, and adjustments to the increased labor costs that will result from parity in compensation and benefits in the care and education sector.5

- Assessments to examine and plans to monitor and mitigate possible negative consequences, such as workforce shortages, reduced diversity in the professions, increased disparities among current and future professionals, upward pressure on out-of-pocket costs to families for care and education (creating a financial burden and potentially driving more families into the unregulated informal sector), and disruptions to the sustainability of operating in the for-profit and not-for-profit care and education market.

- Recruitment plans to engage a new, diverse generation of care and education professionals, highlighting the prospect of a challenging and rewarding career.

- Assessment plans to monitor progress and adapt implementation strategies as needed.

Successful strategies will require cooperative efforts that involve sectors beyond those involved directly in early childhood and elementary education, such as those focused on economic development and postsecondary education. At the federal level, for example, current interagency efforts organized around early learning programs should consult and coordinate with the Office of Postsecondary Education and the U.S. Department of Labor. A similar diversity of sectors will need to be represented in efforts at state and local levels. The range and complexity of factors that need to be coordinated also means that changes to degree requirement policies will need to be implemented over time with careful planning, and as a result, concurrent steps need to be taken to ensure that specialized training related to early childhood development and the core competencies that are critical for quality practice can be achieved through a range of professional learning mechanisms.

If implemented successfully, the shift that will result from this recommendation has the transformative potential to develop a more coherent

_____________

5 As noted earlier, while acknowledging that the availability of resources and the implications of increased costs are an important reality that would affect the feasibility of the committee’s recommendations, in clarifying the study charge the sponsors specified that the committee should exclude from its task conducting analyses about funding and financing.

workforce across all professional roles that support children from birth through age 8, with easier recruitment and better retention of well-qualified individuals for all of these professional roles as well as less competition among settings for the best-prepared employees. In addition, when professionals who work with children prior to elementary school and those working in elementary school settings are expected to have the same credentials and receive comparable rewards, these professionals will be better able to see themselves as part of a continuum with mutual respect and expectations that enable better connections, communication, and collaboration.

Implementation Considerations for Recommendation 2

Phased Approach

This recommendation will need to be implemented through a phased approach. Pathways should be developed as long-term strategies with immediate steps and short-term actions matched to the most critical needs. Phases of implementation should be planned with specific ambitious yet feasible timeline benchmarks for percentages of care and education professionals with a bachelor’s degree. Specific timeline benchmarks for quality improvements and the capacity to absorb more students in degree-granting programs in institutions of higher education will also need to be set and aligned with the timeline for degree requirements. Similarly, timeline benchmarks for changes to related policies will need to be set and aligned. These timelines will also need to be aligned with resource mobilization and financing strategies.

The Importance of Context