Evaluation of the Exploratory Advanced Research Program (2022)

Chapter: Section 2 - Evaluation of EAR Program Processes

SECTION 2

Evaluation of EAR Program Processes

The enabling legislation authorizing the EAR Program provides very little detail prescribing how FHWA should organize and operate the Program. As a result, the Program’s operational activities and governance have evolved substantially since 2007. This section describes those activities based on the Program’s operations as of 2020 and assesses the alignment between the Program’s management and its strategic objectives.

2.1 EAR Program Objectives and Strategy

The EAR Program’s FY 2008 BAA provides a succinct statement of the Program’s purpose and goals:

The program scope is intentionally ambitious and broad to address the wide spectrum of topics and strategic objectives that the funded investigations will support. . . . Strategically, this research will help the FHWA improve highway safety, reduce congestion on the Nation’s highways, reduce environmental and health impacts of the Nation’s highways, and reduce the long term costs and improve the efficiency of the Nation’s highways. This program is intended to spur innovation and focus on high risk and high payoff R&D projects.

As of FY 2020, FHWA (2020) expanded this description of the EAR Program to specify more precisely its criteria for selecting research to support:

Exploratory Advanced Research bridges basic and applied research. In contrast to basic research, EAR Program funded research projects have a mission-orientation. In contrast to applied research, EAR Program funded research does not pursue a narrowly-defined application or product. Incremental advances and demonstrations or evaluations of existing technologies are not within the scope of this program.

The Program’s purpose and intent are defined primarily through its interpretation of what constitutes “exploratory advanced research,” which the BAA equates with “transformational research.” The Program’s focus is framed in relation to the three forms of R&D defined by the Office of Management and Budget: basic research, applied research, and experimental development (National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, 2018).

Basic research is defined as experimental or theoretical work undertaken primarily to acquire new knowledge of underlying foundations of phenomena and observable facts. . . . Applied research is defined as original investigation undertaken in order to acquire new knowledge. Applied research is, however, directed primarily towards a specific practical aim or objective. Experimental Development is defined as creative and systematic work, drawing on knowledge gained from research and practical experience, which is directed at producing new products or processes or improving existing products or processes.

Because the EAR Program states that it excludes work on existing technologies—implying that research should focus on novel concepts and technologies—it also excludes research that constitutes “incremental advances,” thus concentrating more on research that can generate

more radical progress in scientific knowledge. Unlike basic research, which seeks to generate knowledge for its own sake, the EAR Program is motivated by the desire to help FHWA address key social outcomes related to highway transportation.

One way that the EAR Program frames its research objectives is through the FHWA TRL framework. This rubric defines a continuum of progress, from a research concept to a technology ready for use in the marketplace or a field setting. FHWA developed a TRL framework, shown in Table 2-1, based on the early TRLs defined by NASA and the Department of Defense. The EAR Program expects that its research projects will focus on concepts at TRL 2 or 3 and advance them up to TRL 6 or 7.

Summarizing the key points from the Program description, the projects funded by the EAR Program should have most of the following properties:

- The projects should focus on novel technologies (those not previously applied to surface transportation) or use novel methods for conducting research.

- The projects should have the potential to generate results with substantial benefits to FHWA in advancing progress toward improved highway safety, efficiency, and sustainability.

- The projects should investigate fundamental principles and phenomena but in the context of the potential real-world applications and utility of the research results.

- The projects should generate new knowledge and insight that can then be disseminated to the broader communities involved in highway research and operation, including FHWA and U.S. DOT, state and local transportation authorities, and private firms.

These characteristics echo a category of research known as “use-inspired basic research” or “directed basic research,” identified by the scholar Louis Stokes in his book Pasteur’s Quadrant (Stokes, 1997). This type of research combines some of the characteristics of basic and applied research (using the Office of Management and Budget definitions). Section 4 discusses the implications of this type of research in more detail.

The EAR Program’s strategy and governance are constrained by its position within the FHWA R&T system. The Program is a component within the FHWA Office of Corporate Research, Technology, and Innovation Management, distinct from the other offices that focus on R&D applied to specific FHWA priorities (the Office of Infrastructure R&D, the Office of Operations R&D, and the Office of Safety R&D). As noted earlier, the EAR Program has a relatively modest budget and competes for funding with those other offices. To manage

Table 2-1. FHWA TRL taxonomy.

| Type of Research | TRL | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Research | 1 | Basic principles and research |

| 2 | Application formulated | |

| 3 | Proof of concept | |

| Applied Research | 4 | Components validated in laboratory environment |

| 5 | Integrated components demonstrated in laboratory environment | |

| Development | 6 | Prototype demonstrated in laboratory environment |

| 7 | Prototype demonstrated in operational environment | |

| 8 | Technology proven in operational environment | |

| Implementation | 9 | Technology refined and adopted |

potential conflicts, the EAR Program has developed a complementary relationship with other parts of FHWA R&T:

- The EAR Program involves the staff of the R&T Offices, as well as other components across FHWA, in identifying the research topics for future BAAs so that those offices’ needs and priorities are reflected in the Program’s annual funding strategy.

- The EAR Program asks the R&T Offices (and occasionally other parts of FHWA) to provide staff who are responsible for overseeing EAR projects (i.e., AOTRs), thus eliminating the need for the Program to hire dedicated project officers.

- The EAR Program involves FHWA R&T staff in many Program activities, such as briefings on project results. This ensures that the other offices benefit from the new knowledge generated by EAR-funded projects and that the research remains focused on areas relevant to R&T.

A key body involved in the governance of the EAR Program is the FHWA Corporate Implementation Group (CIG). This group is composed of representatives from the FHWA R&T Offices, and at times other parts of FHWA (such as the ITS JPO), and meets three to five times a year. Among other topics, the CIG receives reports on activities and research results from the EAR Program (including the NRC RAP). The group also resolves management issues (e.g., staff workload, timelines, cybersecurity) and advises the EAR Program Director on strategic planning and priorities.

Beyond FHWA R&T, the EAR Program relies on a number of other stakeholder organizations to plan and carry out its strategy:

- The Program draws on other components of FHWA for advice on research topic selection; for experts to serve as proposal reviewers; and, occasionally, for staff who can serve as project oversight officers. The Program has worked particularly well with staff from the Office of Planning on topics related to transportation system modeling and forecasting and with the ITS JPO on topics relevant to intelligent transportation. Other sources of topics include the office overseeing policy, the office overseeing freight management, other FHWA divisions, and the Resource Center.

- The Program maintains relationships across U.S. DOT, given that its scope can relate to other aspects of transportation. The EAR Program has recruited proposal reviewers and workshop participants from the Federal Railroad Administration, the Bureau of Transportation Statistics, the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration, and the Volpe Center, among other agencies.

- From time to time, the EAR Program reaches out to other federal agencies for expertise in specific research areas or to coordinate on future research relevant to those agencies. The Program has, in the past, developed formal agreements with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the National Science Foundation, DOE (and ORNL in particular), and NASA. The Program has also consulted with the Department of Homeland Security, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and similar agencies on specialized topics. Kuehn has served as the FHWA representative on interagency working groups and committees under the National Science and Technology Council, particularly on topics related to artificial intelligence.

- Many of the topic areas for EAR-funded research are expected to benefit state and local transportation authorities. Therefore, those agencies may be future transition partners involved in implementing technologies and concepts developed with EAR funding, and they often have input relevant to planning future research investments. State DOT personnel have participated in workshops convened by the EAR Program or have been included in proposal review panels. State DOTs have also been included as partners in EAR-funded research projects led by academic and industrial researchers.

Table 2-2. EAR Program stakeholder groups and their involvement in program activities.

| Stakeholder/Processes | Topics & Project Selection | Project Eval & Technical Support | Technical Eval | Transition Support | Outreach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FHWA EAR Program staff | X | X | X | X | X |

| CIG1 | X | X | X | X | |

| FHWA R&T Office staff | X | X | |||

| FHWA AOTRs | X | X | X | X | |

| Volpe Center | X | X | X | X | |

| Other federal agencies | X | X | X | ||

| State and local authorities | X | X | |||

| University researchers | X | ||||

| Industry | X | X |

1 CIG includes members from different types of stakeholders.

- Members of the broader surface transportation research community have been involved in the EAR Program in various ways. Some proposal review panels have included experts from industry and from nonprofits focused on surface transportation and highway activities. The EAR Program leverages FHWA’s relationship with TRB to identify experts and disseminate research results. Other experts involved in EAR Program review panels work in automotive manufacturing, freight transportation, and construction. Most significantly, the EAR Program conducts outreach to researchers in academia, nonprofits, and industry to solicit new proposals relevant to topics listed in the EAR BAAs.

Table 2-2 summarizes the degree to which different stakeholder groups contribute to various EAR Program activities. Kuehn maintains active relationships with this broad range of organizations and entities, often reaching out personally with requests for expertise, participation, and input. The members of the CIG have also leveraged their relationships and contacts to assist the Program. This network of contributors and interested parties helps to maintain the relevance and currency of the EAR Program’s research planning activities. Kuehn also participates in transportation research conferences and similar events to maintain those relationships, make new contacts, and promote the EAR Program.

2.2 EAR Program Management and Activities

The EAR Program conducts specific ongoing activities to carry out the life cycle of research planning, management, and dissemination. The evaluation examined activities in the following categories:

- Activities related to the formulation and selection of topics for inclusion in the annual EAR BAA,

- Activities for processing submitted proposals and selecting projects for funding,

- Oversight of funded projects and support activities to assess project results, and

- Activities to promote the dissemination of research results and potential transition of results to other research and technology development organizations.

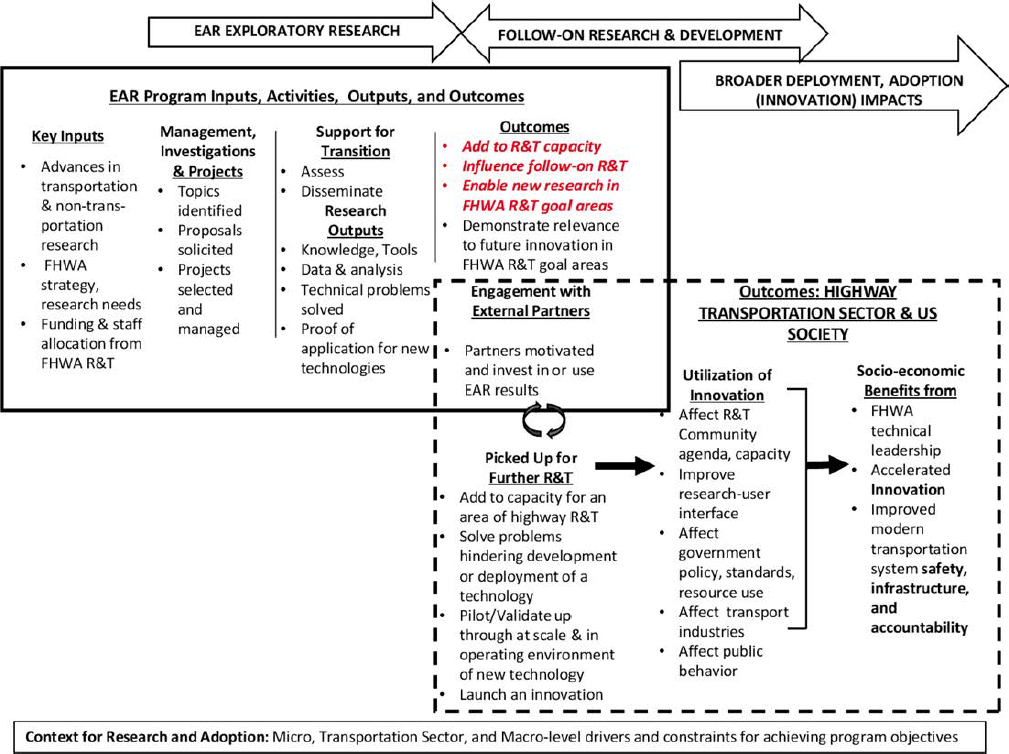

To aid in analyzing EAR Program operations, this evaluation developed a program logic model that depicts the inputs required to conduct EAR Program activities; the internal Program operations to carry out its mission; and the processes by which the Program’s research results

are disseminated through project outputs, which may influence both short-term and long-term outcomes. This logic model is depicted in Figure 2-1.

Examples help to illustrate the elements of the logic model and what they encompass:

Key inputs include the primary resources guiding and enabling the EAR Program. The Program draws on existing fundamental research in transportation and other relevant fields. FHWA’s strategy and research priorities set the parameters of the EAR Program and the function it performs within the FHWA R&T Program. FHWA also establishes the annual funding and staffing levels for the Program.

Management, investigations, and projects. EAR Program activities include the usual management activities of strategic and implementation planning as well as communication and involvement with stakeholders. Before soliciting any proposals, at regular intervals Program staff receive ideas on topic areas from FHWA R&T staff, do their own research, and host a variety of workshops and other events to gather ideas and discuss priorities. Proposals are solicited and reviewed by topic experts for merit. A final group of projects is approved for the next cycle of project funding.

Support for transition. Once a project generates outputs and results (see the following paragraphs), the EAR Program also supports utilization of the research by publicizing project and Program results. EAR Program staff and project managers also look at project results to separate out those that are likely to be picked up by others. For those results, the Program staff assembles an expert panel to assess the stage of the research in order to communicate how far each research result has progressed on the path to development and application.

Outputs of EAR-funded research projects may include:

- New data, knowledge, and knowledge tools;

- Solutions to certain technical problems; and

- Proof that an application based on the research may be feasible and justifies further R&D.

These outputs are described in reports, journal articles, presentations, demonstrations, and other works that are then disseminated to interested audiences.

Shorter-term outcomes are effects influenced directly by EAR Program activities. Several aspects of FHWA capabilities and agency operations benefit from EAR Program contributions. These include increases to the capacity, capabilities, and knowledge of FHWA R&T; influence over future R&T research investments; and the development of demonstration programs to test technologies based on EAR-funded research. Beyond FHWA, the EAR Program’s immediate outcomes touch many organizations across the surface transportation research community, industry, and stakeholders:

- Engagement with external partners. This broadens the community of practice working in the research areas funded by the EAR Program and helps to provide a receptive audience of researchers who can move technologies from the early applied research stage to experimental development and implementation. Engagement also facilitates three sets of further outcomes.

- Picked up for further research and technology development. Because the EAR Program funds only the exploratory stage of research, progress toward technology development requires involvement and investment by transition partners, including other government agencies, research institutions, and industry. These efforts may extend to validation of the functionality and cost of a technology at an ever-more realistic scale and operating environment.

-

Utilization of an innovation generated from EAR-funded research may arise through very different pathways:

- – Influence the R&T agenda. Innovative ideas and concepts may convince members of the surface transportation research community to change the direction and nature of their future work, or they may enable new areas of research. This is evident especially in cases where the EAR Program funds the development of new research tools, methods, and datasets.

- – Intensify researcher–user interactions. Innovations often require intensive collaboration between users and researchers, and this enables users to adopt those technologies rapidly. Examples include increased ability to simulate and forecast technology utilization, facilitation of field-testing and market demonstrations, and promotion of standards-setting efforts.

- – Lead to adoption within the transportation industry. Firms and other industry organizations are likely to be the target end users of technologies developed from FHWA-funded innovation. Innovations could be new or improved raw materials; new products, processes, and business models; and new decision-support tools anywhere along the supply chain.

- – Inform and enhance government policy and operations. Innovations based on EAR-funded projects may be put to use by the federal government, by state DOTs, or by other public agencies. Such innovations might change and improve policies and standards, or

- they could be technology implemented by government users, such as a new decision-support tool for transportation planning.

- – Influence the public and public groups. Some innovations may be targeted directly to the public or public groups, such as advocacy organizations, in order to influence their decisions, behaviors, and actions. Two examples are data or tools that change travel choices and personal mobility devices.

Longer-term outcomes and impacts of the EAR Program are the socioeconomic benefits and costs associated with using the innovations that it supports. These include benefits from innovations in the areas of U.S. DOT strategic goals: safety, infrastructure, and accountability. The EAR Program also supports efforts to enhance innovation within U.S. DOT itself. These long-term outcomes may take years to become evident, and the precise role of the EAR Program in changing such outcomes—for example, decreasing annual highway fatalities—may be obscured by other changes in the transportation system.

The key inputs to the EAR Program are mostly beyond the Program staff’s span of control, although relationships with its stakeholder community can influence the availability of those inputs. This section provides a description and assessment of EAR Program activities related to Program management; selection of research topics and projects; and research oversight, dissemination, and transition. Information related to EAR Program outputs and outcomes can be found in Section 3.

2.2.1 EAR Program Management

The EAR Program manages three primary work-streams: (1) the planning, solicitation, and direct funding of external research projects; (2) planning and execution of support activities for funded research, including TRL and IT assessments, the dissemination of research project descriptions and results, and technology transition; and (3) the NRC RAP. Research project selection and subsequent support tasks involve extensive planning and administration, including

- Publishing BAAs, public research summaries, and workshop reports;

- Reviewing preproposals and proposals, selecting proposal reviewers, and overseeing review panels;

- Recruiting and supporting FHWA project officers who oversee EAR-funded research efforts;

- Reviewing and assessing proposed topics for inclusion in the EAR BAA, including management of workshops convened to assess topics;

- Negotiating support contracts with other agencies and private firms to facilitate technology transition and dissemination of research results; and

- Coordinating EAR Program research activities with other research units at FHWA, U.S. DOT, and other federal agencies.

For the NRC RAP, a staff member of the EAR Program works with the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to recruit postdoctoral scholars and senior researchers for review and selection as Research Associates. That staff member also matches each incoming Research Associate with a staff member at TFHRC, facilitates the Associate’s travel and housing in the DC area, and advises on the dissemination of research results. While Research Associates are not involved with the extramural research funded by the EAR Program, there are cases where Associates’ research has aligned with EAR Program topics. The NRC RAP also contributes to expanding the research capacity at FHWA R&T and helps to recruit new researchers into offices at TFHRC and other FHWA components.

The EAR Program operates with modest staffing levels. The Program Director is, at present, the only full-time position dedicated to EAR research project management. One other position

is designated for Program marketing and communication activities and managing the Research Associates. As a result, the Program is dependent on staff time contributed by other FHWA R&T Offices for project oversight (see Sections 2.2.3 and 2.2.4).

While the Program is highly efficient in managing all Program activities with minimal dedicated staff positions, this raises some potentially detrimental risks. First, it became evident during this evaluation that the volume of record-keeping for the EAR Program has grown over the years, and it appears that the Program Director has the primary responsibility for tracking and storing all such records. Given Kuehn’s other duties, some past project records are not easily located and may no longer be available. The project literature, including FHWA Factsheets describing funded projects and TechBriefs summarizing research results, appears to be mostly complete and accessible via the FHWA R&T website. However, proposals, reports, and other records submitted to the Program would benefit from regular organization and maintenance. The evaluation team has developed a database of prior EAR-funded projects to help rectify this situation.

A more significant existential risk to the Program is the tremendous share of Program responsibility and understanding held by one individual: the current Program Director, who has served in that position since 2008. Interviews with stakeholders indicated that Kuehn is well respected in the R&T community and has built substantial goodwill and strong relationships with other FHWA staff and external organizations. However, if Kuehn were to retire or otherwise be unavailable, FHWA may lose substantial institutional knowledge and social capital that is essential for the Program’s continued operations. The EAR Program staff has documented many of the management processes required for administering the EAR Program, but a more comprehensive approach to succession planning may be warranted.

2.2.2 EAR Research Topic Selection

The annual cycle of EAR research funding activities begins with drafting the annual BAA solicitation. The EAR Program regularly canvasses key stakeholders to gather suggestions for future BAA topics. Suggestions are submitted by R&T Office staff, representatives of other FHWA components, and experts at other U.S. DOT agencies as well as, less frequently, experts outside of U.S. DOT.

For suggestions that seem to have noteworthy potential as exploratory advanced research, the Program staff conducts an Initial Stage Investigation (ISI). This process starts with a literature review conducted by the library staff at FHWA R&T, plus informal consultations with knowledgeable experts. If further information is needed, the EAR Program funds a workshop for R&T community members to discuss current developments in the suggested area. In some years, as many as 20 topics were submitted for consideration, although since 2016 the number of topics has varied between six and 10 per year.

During the process of drafting the BAA text, the EAR Program Director presents potential topics to the CIG for discussion. Once there is a consensus on the topics selected for inclusion, the EAR Program staff composes the description of each topic based on findings from the relevant ISI. Topics that are not selected for inclusion may be held for consideration in a later year or discarded. In general, a given BAA lists three or four topics, although in many cases certain topics are subdivided into more specific subtopics.

Four conditions contribute to decisions on the topics to be included in the BAA. The first consideration is relevance to FHWA key objectives and whether the topic represents research gaps that the FHWA R&T Offices cannot address through their own funding or resources. The second factor contributing to topic selection is whether a member of the FHWA R&T staff

(or a representative from another part of FHWA) is willing to perform oversight duties for projects related to that topic. Third, the entire set of proposed topics is assessed to ensure that the range of topics selected is balanced and meets the needs of different offices. Fourth, the topics selected by EAR need to meet the criteria of exploratory research. In other words, the topics need to focus on addressing questions that are relevant to FHWA’s current R&T research efforts but are too high risk and fundamental to fit a more applied research profile of FHWA.

The topic selection process is well structured, and all suggested topics are logged in a Share-Point repository with the name of the individual who submitted the topic and its final disposition. In the interviews, a few stakeholders expressed some concern that a few prior topics did not appear to be “exploratory,” from their perspective, and instead focused on more incremental and applied work. The description of “exploratory advanced research” published in the BAA is intended to be ambiguous to allow flexibility in Program decision-making, but that ambiguity may lead to confusion among observers about why certain topics are deemed “exploratory.”

2.2.3 EAR Program Proposal Review and Project Selection

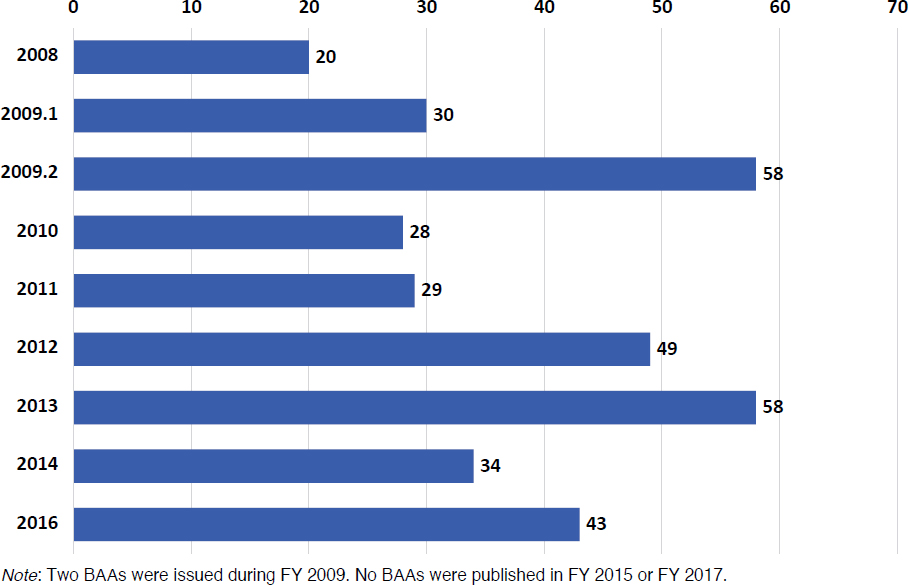

After publication of the BAA, the EAR Program receives proposals for potential topic ideas.1 The number of proposals considered has ranged roughly between 30 and 60 per year, influenced primarily by the number of topics in the BAA.

The EAR Program convenes separate expert panels for each topic in the BAA; note that not all topics elicit sufficient proposals to merit awarding funds for that topic. The panel members are selected with the assistance of the CIG. Each proposal is evaluated on two primary criteria: scientific and technical merit, and importance to FHWA programs. To analyze scientific and technical merit, reviewers are instructed to consider how well the proposer describes the project’s technical approach; a comparison of the project to the state of the art in the field; and a proper appreciation of technical challenges, with strategies for mitigating technical risk. Evaluators also examine the proposal’s technology transition plan to see if it offers a realistic assessment of the opportunities to move the research results into practice. To assess importance to FHWA programs, reviewers look especially at how the proposed project would advance progress toward FHWA’s long-term goals. Under this criterion, reviewers can also give higher scores to proposals that develop partnerships with organizations outside of the traditional highway research community.2

A proposal’s budget is not a factor considered by the reviewers, except in two respects. First, reviewers can point out situations where they believe that the proposal budget is substantially lower than the resources required to carry out the project. Also, as originally authorized, the EAR Program can only cover 80% of the proposed budget. The remaining 20%, noted as the proposer’s cost share, must be contributed by members of the proposal team, either as direct funding or as in-kind support (such as free access to data, staff labor, equipment, or similar resources). A proposal can be downgraded during evaluation if it does not meet the cost share requirement. However, this requirement applies only if the project is funded under a cooperative agreement. In certain situations, the EAR Program can elect to structure a project under a research contract, which has more rigid requirements for the research performer. When using a contract, FHWA is allowed to reduce the cost share required.

___________________

1 In FY 2007, the EAR Program used a two-step process that requested preproposals; following review and consultation with expert advisers, a subset of submitters was invited to submit full proposals.

2 The supplementary directions to reviewers are provided as noted in the appendices of most review panel summary reports.

A review of proposal evaluation panel reports from funding competitions between 2007 and 2017 showed that for each year, the total budget of projects deemed worthy of funding by the panels exceeded available EAR funding, often by a substantial amount. The Program Director can thus use cost as an evaluation factor, selecting worthy proposals whose combined budgets are equal to the Program’s budget for that year. The CIG is also consulted in this process.

Once a proposal has been selected for award, FHWA notifies the proposer’s institution and establishes the funding agreement. FHWA can request revisions to the project’s budget, if warranted. Some funded PIs noted during interviews that their projects experienced lengthy delays in starting due to protracted post-award negotiation and processing. The actual timing of the proposal submission deadline and award notifications varied from year to year, due in part to intermittent uncertainty about the Program’s budget and delays in the appropriations process. The interval between submission deadline and award published in the BAA ranged from two months to as long as seven months.

Figure 2-2 provides a count of the proposals reviewed under each BAA, based on tracking data provided by the EAR Program. The EAR Program did not award any funding in FY 2015 or FY 2017 because of lapses in authorization. This uncertainty could cause some proposers to be hesitant about applying for EAR funding, although the evaluation team did not observe any notable decline in proposals due to that disruption.

2.2.4 EAR Program Research Project Oversight and Transition Support

Once the EAR Program awards funding to a research project, primary oversight is the responsibility of the assigned project officer (AOTR) at FHWA. That person is the research team’s primary point of contact at FHWA. Based on survey responses and interviews, these FHWA staff members are active partners to the research teams in guiding research planning and monitoring

results. Each project officer receives regular research progress reports from the project team but also frequently supports the project in other ways:

- Facilitating contact with other researchers at FHWA who are working in topics related to the project;

- Suggesting venues for disseminating research results, such as key conferences or presentations to interested stakeholders;

- Providing telephone consultation, when requested, on project issues; and

- Recommending potential transition partners and introducing project teams to contacts in state transportation authorities, industry, and federal agencies.

Project officers are periodically invited to speak at CIG meetings about achievements of the research teams under their supervision. The group members then provide additional feedback that the AOTR can relay to the project team.

The participation of FHWA research staff as project officers helps to ensure that research projects remain connected to the research interests of FHWA R&T and overall FHWA priorities. Because many of these staff members also serve as proposal reviewers, they have early insight into the research topics that the EAR Program can support, and they guide project teams to investigate specific topics that are beyond the capacity of FHWA research units. This provides valuable intelligence about the state of the art in fields relevant to FHWA R&T and allows FHWA to leverage extramural research efforts in exploring emerging topics. At the same time, the AOTRs face occasional challenges in balancing their work for the EAR Program with their other responsibilities as full-time FHWA research staff.

EAR Program Support for Research Dissemination

The EAR Program plays an active role in communicating the significance of funded projects and disseminating research findings from those projects. Within a year of the funding of new awards, the EAR Program composes and publishes EAR Factsheets, which contain summaries of the research projects undertaken related to each BAA topic and their potential significance to FHWA goals. As those projects generate significant findings, the EAR Program may publish a profile of the projects and their results as FHWA TechBriefs. In some cases, the EAR Program also oversees the publication of final project reports, in full and summary format, as official FHWA documents. However, the EAR Program has not documented clear criteria that determine whether project reports are published this way.

The results of EAR-funded research are disseminated most frequently through technical reports issued by the PIs themselves. In many cases, results are also published as journal articles or presentations to technical conferences. Based on information from interviews, PIs are expected to report newly published articles based on EAR-funded research to their FHWA project officers. However, there is no central catalog of these documents, and the progress reports are generally held by those FHWA staff members rather than compiled in a common repository. Like other federal research programs, the EAR Program’s funding agreements requires PIs to acknowledge FHWA support in published articles. However, PIs may overlook including the acknowledgment when submitting article manuscripts. Section 3 documents the evaluation team’s process for identifying and categorizing research publications that appear connected to EAR-funded projects. Given the labor and effort involved, the EAR Program could benefit from collecting information about such articles during and after each research project and storing the reference information in a database.

EAR Program Support for Technology Transition

A key objective of the EAR Program is to advance promising research concepts from exploratory research to technology development. As an exploratory research program, not all

EAR-funded projects will lead to technology transition. In such programs, many efforts produce findings that a research topic or concept is not yet ready for further development for various reasons (e.g., remaining technical barriers, lack of required complementary technologies, insufficient performance to meet potential user needs). During the course of a project, the EAR Program determines whether the results indicate that transition is feasible and then works with the project team on efforts to prepare the technology for future transition.

Beginning in FY 2013, the EAR Program has documented and implemented a structured approach to transition support. Key steps include the following:

- All project proposals and all funded projects are required to include an initial Technology Transition Plan and a Basic Communication Plan. These documents list potential organizations that might have an interest in conducting follow-on research if the project achieves its technical objectives, as well as venues for disseminating research results.

- Each year, the EAR Program staff conducts a scan of all active projects to determine whether any qualify for enhanced transition support. This scan consists of simple screening questions to determine whether a project has achieved sufficient progress, shows promise for potential impact relevant to FHWA, can attract interest from external sponsors, and has a strong project champion willing to follow through on transition efforts.

- Projects that qualify for enhanced support undergo a more detailed analysis, which may include a TRL assessment, an IT assessment, and formulation of an Enhanced Communication Plan. TRL and IT assessments are conducted by individuals or organizations with expertise in the project’s research area. If these assessments state that the technology has reached sufficient maturity and its related software meets minimum standards for reliability and robustness, then the technology can be presented to external sponsors for follow-on investment. The Enhanced Communication Plan identifies specific organizations and individuals to be contacted to share research results and obtain feedback. The evaluation team was provided with a selection of TRL and IT assessment reports and communication plans. Note that these assessments are conducted on both specific project results and more general technology areas. In some cases, the EAR Program has funded multiple projects intended to explore different aspects of the same technology.

- Technologies that are deemed sufficiently mature for transition undergo analysis for an Initial Transition Plan. This plan follows a rubric requiring the examination of key factors that facilitate technology commercialization, such as identification of user audiences and markets, specification of technical hurdles to overcome, estimation of potential user benefits, presence of competing technologies, and a strategy for communicating the technology’s promise to specific organizations. If the Initial Transition Plan still shows that the technology has substantial promise, the EAR Program engages outside experts (most commonly from the Volpe Center) to generate a more detailed Full Transition Plan.

- Additional supplementary materials that may be developed to facilitate the transition of promising research results include logic models (diagramming the inputs, outputs, and outcomes associated with the research area), market assessments to forecast potential technology adoption, and draft statements of work to guide planning of follow-on research.

CIG members also participate in activities related to transition support. Specifically, they review projects early to identify which are ready for general support with transition, and they review projects later to identify which get additional support in the form of an IT or TRL assessment or both and communication plan development. They discuss individual project handoff strategies within FHWA as well as provide general support with transition. Later on, they determine the projects that will receive additional support from potential external partners with similar research interests, such as the Army Corps of Engineers and the Engineering Directorate at the National Science Foundation (NSF).

CIG members have assisted the EAR Program in accessing a range of resources for expertise and partnership opportunities. The group facilitates collaboration with other components within FHWA and also leverages relationships with DOE and other organizations, including the Federal Laboratory Consortium for Technology Transfer. Examples of such outreach activities include

- Developing plans to support investigators in finding interested audiences for their research results,

- Planning workshops on new topics and identifying potential participants, and

- Arranging conversations with experts at the Volpe Center and consulting organizations—such as Noblis—for technical assistance in project selection and oversight.

The evaluation team was not able to develop a validated list of all projects that had undergone screening for enhanced transition support. The case study analysis used documents obtained from the EAR Program to illustrate TRL and IT assessments for both the subject technologies (CM, TP, and VA) and, in some cases, product-specific IT assessments (for software packages developed in the VA projects). Other technologies that were subject to TRL assessments include sensor and remote video capture technologies, wayfinding and navigation technologies for pedestrians, decarbonization technologies for highway structures, agent-based and evolutionary modeling techniques, nanotechnologies for construction materials, and systems for evaluating connected vehicle applications. The EAR Program publishes information for AOTRs detailing how they can help project teams prepare for transition support. The Program did not indicate how many FHWA staff members have received that information or whether it has improved the quality of transition support.

In the responses to the PI survey, 10 of the 25 respondents were not aware of any TRL or IT assessments related to their project. In two cases, the PIs’ projects were conducted before the EAR Program created and implemented its transition process. Also, there were two instances where the EAR Program had conducted a project assessment that the PI was apparently unaware of. Fifteen of the 25 respondents stated that their projects did not receive any support in developing communication plans. Of the PIs involved in enhanced transition planning, nine rated that support “very effective” or “effective” in aiding the PIs’ transition efforts, and six rated the support “somewhat effective” or “not effective.” Among the 10 PIs involved in communication planning activities, four rated those activities “very effective” or “effective” in assisting the PIs’ own efforts, and six rated them “somewhat effective” or “not effective.” On balance, the PIs who did receive enhanced transition support were generally satisfied with the support received. However, the PIs may not be well positioned to judge the ultimate outcomes of those transition activities.

The EAR Program has instituted more systematic and structured approaches to transition support, including guidelines for FHWA oversight staff, implementation of TRL and IT assessments for selected technologies and projects, formulation of more detailed communications and handoff plans, and approaches to planning research handoffs at different TRLs. However, the Program did not provide any data that track the specific technologies and projects that received such enhanced support, nor has the Program collected information on the results of those enhanced support activities and the eventual outcomes for the technologies assessed. No data exist on the benefits gained by implementing this more structured process or by offering detailed guidelines to AOTRs. The EAR Program might consider developing a monitoring and evaluation (M&E) process and tracking system to understand how these enhanced efforts facilitate technology transition when implemented. A systematic M&E effort could identify opportunities to revise and improve specific efforts, as well as the overall process.

2.3 Findings from the Process Evaluation

The EAR Program appears to have successfully evolved its management structure and practices for implementing the Program, especially given the constraints on its resources. The Program Director has been taking steps to ensure that key processes are well structured and documented to enhance their performance consistency. He has also been successful in enlisting the interest and support of a wide range of stakeholders to provide access to top-level experts, both in the technical domains of EAR-funded research and in justifications that link potential and actual EAR projects to FHWA strategic goals and priorities. The net goodwill that the Program Director has built with a diverse set of Program stakeholders enables the Program to operate efficiently while also responding to the potentially divergent interests of those stakeholders. With the support of upper management through the CIG, the Program Director is able to manage an extremely broad portfolio of research efforts spanning multiple fields.

Within that context, the process evaluation yielded some observations that could improve the EAR Program if it continues under its current structure and mandate:

- This evaluation showed that a retrospective analysis of EAR research activities requires a well-structured data and document management system. Minimal staffing levels for the EAR Program appear to have hampered the investment of time and attention in record-keeping because Program staff must focus on implementing current activities. Developing a more robust infrastructure for record-keeping could yield benefits in the future by enabling more frequent evaluation, deriving lessons learned from both retrospective and concurrent analysis, and more readily identifying opportunities for process improvement.

- With improved record-keeping, the EAR Program could do more targeted evaluation of its own processes and their results. It would be helpful to know, for example, whether better information for FHWA staff about transition support leads to more effective assistance for PIs and more productive transition activities. Program records could also include immediate research outputs (e.g., journal articles, conference presentations, patents, and students trained) associated with each project, offering more insight into the dissemination of knowledge generated by the EAR Program.

- A potential issue complicating Program management is instability in the EAR Program’s budget from year to year. Based on funding availability, it is possible that well-qualified proposals submitted in a year with a lower budget would have been funded if submitted in a year with a higher budget. Budget instability also contributes to inconsistency across years in the proposal submission period and the ultimate award date for funded projects. These circumstances may discourage some proposers from submitting proposals to the EAR Program, since they have no information about the likelihood of receiving an award and may not receive information about new BAAs in a timely manner.

- Ultimately, this evaluation was designed to examine whether the EAR Program has been designed and implemented in a manner that enables it to identify and support exploratory and advanced research topics. In other words, the study was concerned with the appropriateness of the research funded, especially because some projects might be better suited for funding from other programs. Proposers, reviewers, and stakeholders could benefit from more clarity on how they can determine which research topics appear to qualify as exploratory advanced research. Although the uncertainty over the exact meaning of this term helps the EAR Program maintain some flexibility and managerial discretion, it may also reduce confidence that the Program supports research that could not be funded through other channels.