Defense Software for a Contested Future: Agility, Assurance, and Incentives (2025)

Chapter: 3 Assurance

3

Assurance

INTRODUCTION

Will a software product behave correctly under expected operating conditions? The product’s users desire assurance that that is the case. Although software correctness has been a concern since the beginning of the computer era, a more recent concern1 has been the ability of software to function securely in the face of malicious attacks. The committee was tasked with focusing primarily on security assurance.

Over the past 60 years, practices for achieving assurance have evolved with the growing need for security and the emergence of new techniques for creating assured software. This chapter begins with an overview of the software assurance problem and some of the techniques that are used to address it. The overview is followed by a detailed discussion of assurance practices that have been adopted by some commercial vendors and government programs, beginning with formal verification—the most effective—and continuing to other techniques that can be less effective but are less challenging to adopt at scale. This chapter also provides a brief summary of the issues associated with formal verification of properties other than security.

Following the discussion of assurance practices, the next sections describe tools and processes that have been widely adopted by commercial vendors to achieve security assurance and then describe the assurance requirements that the U.S. government

___________________

1 W. Ware, 1979, “Security Controls for Computer Systems: Report of Defense Science Board Task Force on Computer Security,” RAND Corporation, https://www.rand.org/pubs/reports/R609-1.html.

imposes on commercial vendors and on Department of Defense (DoD) programs. This chapter concludes with findings and recommendations.

BACKGROUND AND DEFINITIONS

Formal Methods

Formal methods constitute the gold standard for creating high assurance software. With formal methods, engineers construct mathematically rigorous models (e.g., using first-order logic, type theory, or a domain-specific logic) that describe the architecture and behavior of the system and its environment. These models make it possible to formally prove properties about the architecture (e.g., “commands are only executed for previously authorized entities”). Formal proofs can be easily and automatically audited by a third party, eliminating the need to trust the reasoning embodied in the proof.

Of course, the formal model is only useful if it faithfully represents the actual system and its environment and captures properties of the system that are relevant. One way to realize a faithful connection is to automatically realize the model through synthesis of code from the specification of the model. Alternatively, one can analyze the code to extract a model and prove a formal connection such as refinement; all behaviors that can be exhibited by the code are captured by the model. A third option is to use a program logic (such as Hoare logic) where developers simultaneously construct the code and model, and the rules of the program logic ensure that only valid models are associated with the code. The important point of all of these approaches is that they synchronize the connection between the model and the code.

Formal methods are not a silver bullet for correct software construction. In particular, the following issues should be considered:

- Formal methods work best when the software is designed with proofs in mind,2 so it is hard to apply this approach to legacy code;

- Constructing models and conceiving of the properties to check can sometimes be as complicated as constructing the code itself;

- Building formal proofs of properties is itself an engineering discipline that is not widely known, and it involves a substantial effort; and

- Models may fail to capture important details (e.g., timing or other resource constraints) that are necessary to gain assurance.

___________________

2 T. Murray and P. van Oorschot, 2018, “BP: Formal Proofs, the Fine Print and Side Effects,” 2018 IEEE Cybersecurity Development (SecDev), pp. 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1109/SecDev.2018.00009.

Perhaps most importantly, the model may fail to accurately capture the behavior of the environment, such as hardware, legacy software modules, or other physical components.

Nevertheless, formal methods provide a qualitative leap in assurance compared to standard approaches of software construction by

- Replacing informal and under-specified English descriptions of the system with mathematically precise and rigorous definitions,

- Replacing human reasoning and auditing of code with machine-checkable proofs in a formal logic,

- Ensuring that the model and code are faithfully synchronized, and

- Covering all cases and paths (including potentially infinite paths) through symbolic reasoning, when compared with testing.

Analysis Tools

Analysis tools examine software as it exists and attempt to determine correctness. These tools fall into two broad categories:

- Static analysis tools examine code, whether source code or binaries, and construct a model of the possible behaviors of the code when executed. That model can then be queried to determine if the code is free of particular bad behaviors (e.g., dereferencing a null pointer). Because most properties of interest are undecidable, static analysis will err, often exhibiting both false positives (alarming on non-issue) and false negatives (failing to issue an alarm). However, static analyses can reason about all possible behaviors of the code by constructing suitably conservative models. Generally speaking, source code analysis is easier and more precise but requires access to the source code, whereas binary code analysis is generally less precise (i.e., leads to more error reports that are false positives).

- Dynamic analysis is performed against the code as it is executing on a particular set of inputs and in a particular environment. Dynamic monitoring analysis is used in operational deployments to look for anomalous behavior. Dynamic testing analysis exercises the code under controlled conditions, determining if tested input matches expected output. “Fuzzing” is a particularly effective approach of dynamic testing analysis, where a set of inputs is generated (perhaps randomly) to help exercise different paths in the code.

Compared to static analysis, dynamic analysis does not generate false positives. However, a given test run only sees one possible path in the code given the input, and generally, the number of paths is at least exponential in the size of the code (if not unbounded due to loops, recursion, and/or the space of possible inputs). Thus, dynamic analysis is best suited for identifying the presence of bugs, while static analysis is best suited for establishing their absence.

Evidence

Evidence in this context refers to the architectural documentation (as described in the previous chapter on agility) and the results of formal, static, and dynamic analysis. The more complex the system, the greater the collection of evidence.

While some evidence will be human generated and maintained (e.g., “Quality Assurance engineer 1 attests that the red light came on and was visible.”), that evidence is comparatively expensive. Evidence that is automatically generated, such as reports indicating how much source code was analyzed with which tools, scale well and allow for further evaluation and automation. The value of automated evidence also manifests in Executive Order 14028 on Improving the Nation’s Cybersecurity.3

Assurance

Assurance indicates the confidence that the consumer has that the software product will behave correctly in all circumstances and will successfully resist malicious attempts to compromise its behavior. Assurance encompasses a wide range of activities during the development of the software product with an aim to create a final product that does what it is supposed to, and no more or less. Assurance involves the architectural design, analysis, and resulting evidence to reach a view on the correctness of the software.

The majority of security vulnerabilities have been attributed to flaws of design, implementation, or both. An early, prominent bit of malware, the Internet Worm (1988) leveraged, among other vulnerabilities, a flaw in the fingerd system daemon.4 This flaw is a near-canonical example of how things can be done poorly. There was a design flaw, where the protocol (part of the interfaces called for in the architecture) was not well specified and did not correctly describe the messages exchanged between client and server. This design flaw was compounded with an implementation flaw, a classic memory safety issue that allowed the overwriting of memory (while there was no limit in practice on the size of input to the system daemon, there was a buffer limited to 200

___________________

3 Executive Office of the President (EOP), 2021, “Improving the Nation’s Cybersecurity.” Executive Order 14028, May 12, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/05/17/2021-10460/improving-the-nations-cybersecurity Executive Order 14028.

4 E. Spafford, 1988, “The Internet Worm Incident,” Technical Report CSD-TR-933, Department of Computer Science, Purdue University.

bytes). This flaw rarely caused anything other than a mysterious crash in normal circumstances. However, with a suitably skilled adversary, the flaw became a security vulnerability, which was exploited to great effect on November 2, 1988, when the nascent Internet went down.

Assurance techniques can only be applied to that which is known or designed. A poorly specified system may pass an assurance phase but still be insecure or unreliable. For example, if a system service was specified to “take a line of input, parse it, and execute it,” then one could generate assurances that the service would read arbitrary data and execute it, but not whether it should. A more subtle example is a cryptographic library that has been painstakingly evaluated for its correctness, but the service that uses the library does not have sufficient controls on its cryptographic key management.5

Finally, the assurance process can never be a one-and-done process. Threats continue to evolve as capabilities elsewhere change. A fully specified implementation of the Rivest–Shamir–Adleman (RSA) algorithm as part of a web server’s Transport Layer Security (TLS) protection may be provably correct, but later research can show that it is vulnerable to a new class of attack, such as the key being derived through a timing-based side channel.6 The assurance process inherently reflects a moment in time and requires updates just as the software does.

The assurance process itself is a combination of a variety of elements, depending on the technologies involved and the level of assurance desired. An older codebase, perhaps written in a language that does not afford modern safety techniques, will end up with a process that leverages static analysis, simulation, and exhausting—if not exhaustive—test cases. A modern system, with well-defined architectural boundaries, could be constructed as a provable system that by its nature creates a high-assurance software product.

COMMERCIAL OFF-THE-SHELF PRACTICES

This section examines the current state of commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) development practices from an assurance perspective—ordered by the level (breadth and depth) of assurance a practice provides, highest to lowest. It starts with formal methods, which provide strong and broad security guarantees; then considers memory-safe programming languages, which provide strong assurance about a particular security property;

___________________

5 National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), 2023, “CVE-2023-37920 Detail,” NIST National Vulnerability Database, https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2023-37920.

6 D. Brumley and D. Boneh, 2003, “Remote Timing Attacks Are Practical,” Proceedings of the 12th USENIX Security Symposium.

and then practices that vendors currently apply to software products that may include years-old legacy components written in unsafe programming languages.

Formal Methods

Software has been developed commercially since the dawn of computing some 75 years ago, and software engineering methods have evolved substantially. From the beginning, those programming computers were keen to develop reliable methods by which they could assure that their software would do what they intended. At its 1968 Conference on Software Engineering, the NATO Science Committee declared that it had got to the point that there was a “software crisis” and that “software engineering” was needed to address it.7 Edsger Dijkstra, who attended the event, had been an outspoken advocate of “structured programming” and earlier in 1968 had published an article that argued the dreaded GOTO command should be banned.8 Doing so made it easier for a programmer to reason about a program’s behavior by connecting its spatial flow on the page with its execution in time. A year later, Tony Hoare (who attended the 1969 iteration of the NATO conference) proposed a method for deductively proving properties of a structured program.9 Hoare’s work relied crucially on a 1967 paper by Floyd who proposed the deductive approach for “flowchart” programs.10 Starting then, and sustained up to the present day, there has been an interest in developing such formal methods to build software that is verified to behave as intended, where verification leverages mathematical, logical reasoning.

To use formal methods, an engineer authors a formal specification that precisely describes the system’s intended behavior and then uses tools to automatically (or semi-automatically) reason that the system’s code indeed implements this behavior. Formal methods are the gold standard for assurance, providing mathematical proof that the software behaves properly under all operating conditions captured in the specification. Contrast this level of assurance to that gained from typical software testing, which only considers some operating conditions. These conditions are often chosen according to the structure of the code being tested. For example, tests may be selected so that all lines, branches, or combinations of branch conditions are executed by at least one test. While the hope is that the chosen tests generalize to conditions not explicitly tested, there is rarely a guarantee that this is the case. Empirical studies show that deployed

___________________

7 B. Randell and P. Naur, 1969, “NATO Software Engineering Conference 1968,” Scientific Affairs Division, NATO, January, https://www.scrummanager.com/files/nato1968e.pdf.

8 E.W. Dijkstra, 1968, “Letters to the Editor: Go to Statement Considered Harmful,” Communications of the ACM 11.3:147–148.

9 C.A.R. Hoare, 1969, “An Axiomatic Basis for Computer Programming,” Communications of the ACM 12.10:576–580.

10 R.W. Floyd, 1967, “Assigning Meanings to Programs.” Proceedings of Symposia in Applied Mathematics 19–31.

software often exhibits defects in code that was exercised by one or more tests, just not in the precise way needed to expose the defect.

While the assurance appeal of formal methods is clear, its use in industry began only toward the end of the 1980s and had limited application through the 1990s. Knight et al.11 cite the following three main reasons for this: (1) non-trivial added development costs, (2) the need for developers to understand difficult mathematics, and (3) inadequate tool support. Since that paper was published in 1997, extensive research and development investments have ameliorated all three of these reasons, but most especially the first and third. Accompanying these efforts has been a series of impressive demonstrations of what formal methods can achieve on industrial strength software. As the technology has improved, formal methods advocates have persuaded product decision makers to use formal methods by adjusting their argument to focus on achieving (re)assurance efficiently, and acknowledging and addressing technology risks. The remainder of this section focuses on a few notable developments. For a more thorough and complete treatment of the historical uses and lessons of formal methods, see the survey of Huang et al.12

CompCert

In 2005, the French research laboratory INRIA released the first version of CompCert, a formally verified compiler from a large subset of the C programming language to PowerPC assembly code.13 All of CompCert’s internal algorithms, including those for stack allocation, instruction selection, register allocation, and performance optimization, are verified to be correct. At the time of release, the front-end (which translates a program’s source text into an internal data structure called the abstract syntax tree, or AST) and final assembler and linker (which translate the assembly code into the final executable) were not verified, but later work14 closed this gap somewhat by verifying the parsing and type checking components of the front end.

CompCert is implemented and verified using the Rocq proof assistant15 (originally called Coq, and renamed to Rocq in 2025). When using Rocq, an engineer writes code in a functional programming language called Gallina and proves theorems about the execution of that code by providing proofs that string together a series of automated steps called tactics. Rocq is able to reliably and automatically check the veracity of these

___________________

11 J.C. Knight, et al., 1997, “Why Are Formal Methods Not Used More Widely?” Fourth NASA Langley Formal Methods Workshop, Vol. 3356, NASA Langley Research Center.

12 L. Huang, et al., 2023, “Lessons from Formally Verified Deployed Software Systems (Extended Version),” arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.02206.

13 X. Leroy, 2009, “Formal Verification of a Realistic Compiler,” Communications of the ACM 52.7:107–115.

14 D. Monniaux and S. Boulmé, 2022, “The Trusted Computing Base of the Compcert Verified Compiler,” European Symposium on Programming, Springer International Publishing.

15 ROCQ, “Rocq Prover,” https://rocq-prover.org, accessed June 11, 2025.

proofs. The Gallina code is extracted (basically, a process of very lightweight compilation) into an industrial strength programming language called OCaml, which can then be compiled and executed.

CompCert’s unveiling was an important milestone within the formal methods community, but its impact gained significant mainstream interest in 2011 when Yang et al.16 published experimental results of the use of an automated test generation tool called CSmith. In the experiments, CSmith repeatedly and randomly generates small, well-defined C programs that it compiles using several different compilers, including mainstream compilers gcc and clang/LLVM, as well as CompCert. If any of the resulting outcomes differ, in the sense that one compiler fails while the others do not or the execution of the generated program yields a result different than the others, then that signals a bug in one or more of the compilers. Using CSmith, Yang et al. found hundreds of bugs in the mainstream compilers, but only a handful in CompCert, all of which were in the unverified front-end. Quoting from that paper:

The striking thing about our CompCert results is that the middle-end bugs we found in all other compilers are absent. As of early 2011, the under-development version of CompCert is the only compiler we have tested for which Csmith cannot find wrong-code errors. This is not for lack of trying: we have devoted about 6 CPU-years to the task. The apparent unbreakability of CompCert supports a strong argument that developing compiler optimizations within a proof framework, where safety checks are explicit and machine-checked, has tangible benefits for compiler users.

To date, no bugs have ever been found in the verified components of CompCert. These results have served as a strong motivator for the continued development of formal methods by researchers and their adoption by practitioners. CompCert itself has seen industrial adoption, by Airbus and a few other companies, with parent company Absint providing support.17

seL4

The next significant milestone for formal methods coming out of the research community was the unveiling of the seL4 microkernel in 2009.18 seL4 was designed to be used as a trustworthy foundation for building safety- and security-critical systems, offering

___________________

16 X. Yang, et al., 2011, “Finding and Understanding Bugs in C Compilers,” Proceedings of the 32nd ACM SIGPLAN Conference on Programming Language Design and Implementation.

17 AbsInt, n.d., “CompCert: Formally Verified Optimizing C Compiler,” https://www.absint.com/compcert/index.htm, accessed June 11, 2025.

18 G. Klein, et al., 2009, “seL4: Formal Verification of an OS Kernel,” Proceedings of the ACM SIGOPS 22nd Symposium on Operating Systems Principles.

SOURCE: G. Heiser, 2025, “The seL4 Microkernel an Introduction,” white paper, The seL4 Foundation, Revision 1.4 of 2025-01-08, https://sel4.systems//About/seL4-whitepaper.pdf. CC BY-SA 4.0.

high assurance and high performance. It is available as open source on GitHub19 and supported by the seL4 Foundation.20

The seL4 verification effort, depicted in Figure 3-1, works by refinement. There are three descriptions of the system: the abstract model, the C implementation, and the binary code. The abstract model describes the basic behavior of seL4, and proofs about its confidentiality, integrity, and availability establish seL4’s security properties. In turn, each description serves as a specification for the description one level lower, and a formal proof shows that the latter refines (or “implements”) the former. This means that the security properties proved of the abstract model hold for the lower-level descriptions. The proofs are carried out in a framework called Isabelle/HOL, where HOL stands for “higher order logic.” At the time of its initial release, the seL4 source code included 10,000 lines of C, and seL4’s set of proofs was 200,000 lines long. This set has now grown to well over 1 million lines, most of this manually written and then machine checked.

___________________

19 seL4 Foundation, n.d., “seL4 Microkernel and Related Repositories,” https://github.com/seL4, accessed June 11, 2025.

20 seL4 Foundation, n.d., “The seL4 Foundation,” https://sel4.systems/Foundation, accessed June 11, 2025.

Since the time of its original release, seL4 has seen industrial use by several companies,21 such as DornerWorks,22 Collins Aerospace, and Boeing. seL4 users are interested in building systems that require high levels of reliability and security. The U.S. government is also a willing partner. In the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency’s (DARPA’s) 2015 High-Assurance Cyber Military Systems program,23 seL4 was used to build a quadcopter drone, which was successfully able to resist red-team attacks.

NATS iFACTS and SPARK Pro

In 2011, Altran UK launched the NATS iFACTS system, which augments the tools available to en route air traffic controllers in the United Kingdom. In particular, it supplies electronic flight-strip management, trajectory prediction, and medium-term conflict detection for the United Kingdom’s en route airspace. iFACTS may be the largest formally proven system ever developed. Work had begun on iFACTs in 2006, and when it was completed, it comprised 250,000 lines of code, with proofs of the absence of runtime exceptions, functional correctness, and memory constraints. It is still in active use today.

iFACTS is written in SPARK,24 a subset of the Ada programming language extended with contracts to express properties that should always hold when the contract is reached during execution.25 SPARK was first developed in 1987 by researchers at the University of Southampton, whose company was acquired by Praxis (later renamed Altran UK) in the early 1990s. During the 1990s, SPARK was used on government projects aiming for the highest levels of assurance. SHOLIS (1993–1999), a system aimed to assist naval crews with the safe operation of helicopters at sea, was the first attempt at serious proof of a non-trivial system. It exemplified the problems that Knight et al. describes about the tools in the 1990s: the automated prover (the “Simplifier”) used at the time was resource intensive, taking hours or days to run even on a single sub-program, and proof engineers still had non-trivial manual work to do (which was similar to the use of tactics for proofs in Coq or Isabelle).

By 2006, things had advanced much further. A key to the success of iFACTS is that the SPARK language it was programmed in was limited in ways that supported automatic proof while being appropriate to the target domain. SPARK had well-defined semantics (no “unspecified” behavior as with the more popular C language), with no support for true pointers or dynamic memory management, which imposed strong limits on the

___________________

21 Trustworthy Systems, n.d., “Our Partners and Sponsors,” https://trustworthy.systems/partners, accessed June 11, 2025.

22 M. Miles, 2023, “Building Secure and High-Performance Software Products with seL4 and NVIDIA Hardware,” DornerWorks (blog), https://www.dornerworks.com/blog/sel4-nvidia.

23 Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), 2012, “HACMS: High-Assurance Cyber Military Systems,” https://www.darpa.mil/research/programs/high-assurance-cyber-military-systems.

24 R. Chapman and F. Schanda, 2014, “Are We There Yet? 20 Years of Industrial Theorem Proving with SPARK,” Interactive Theorem Proving: 5th International Conference, ITP 2014, Held as Part of the Vienna Summer of Logic, VSL 2014, Vienna, Austria, July 14–17, 2014, Proceedings 5, Springer International Publishing.

25 AdaCore, n.d., “SPARK Pro,” https://www.adacore.com/sparkpro, accessed June 11, 2025.

data structures and coding style that could be employed. These limits were not out of step with the expectations of the military and civil aviation software development (i.e., real time systems with tight resource requirements), and they made it feasible to prove that memory accesses were safe (i.e., indexes into the array were valid) and memory was never exhausted (because it was all preallocated). The up-front limits also had the benefit that they forced iFACTS’s users to think carefully about upper bounds (e.g., the maximum number of aircraft under consideration at any time) so they could be specified in the system requirements. Note that at the time of this writing SPARK does support pointers and more full featured data structures, imposing a Rust-style borrow semantics to ensure safety.26

The SPARK language’s proof support had also come a long way since the 1990s. On iFACTS, the Simplifier was ultimately able to automatically prove more than 150,000 verification conditions—individual facts that together ensure the full specification are correctly implemented by the software—in about 3 hours, in part by leveraging caching and parallelism. Today, the SPARK Simplifier’s custom prover has been replaced by general-purpose Boolean satisfiability modulo theories (SMT) solvers,27 and its manual proof steps can be carried out in interactive provers like Isabelle or Coq. Thus, it is able to easily leverage algorithmic and usability advances in both kinds of technologies. The full SPARK toolchain is now developed open source28 and continues to enjoy industrial use, perhaps most prominently at NVIDIA for its graphic processing unit’s system management and firmware components.29

Project Everest

In 2016, researchers at Microsoft and INRIA (and, later, Carnegie Mellon University) set out to build and deploy formally verified implementations of several components of the HTTPS ecosystem, such as the record layer of the TLS protocol and its underlying cryptographic algorithms. The verified cryptographic code has seen wide deployment, including in Mozilla’s Firefox web browser, the Linux kernel, mbedTLS, the Tezos blockchain, the ElectionGuard electronic voting SDK, and the Wireguard VPN.30 Project Everest has also developed a verified version of the eBPF interface used in the Windows implementation. A notable feature of all of these deployed artifacts is their high performance, which always approaches but sometimes even exceeds that of popular unverified implementations.

___________________

26 Rod Chapman, personal communication, February 27, 2025.

27 C. Barrett, R. Sebastiani, S.A. Seshia, and C. Tinelli, 2009, “Satisfiability Modulo Theories,” Chapter 33 in Handbook of Satisfiability, IOS Press. 10.3233/978-1-58603-929-5-825.

28 J. Kanig, et al., n.d., “spark2014,” https://github.com/AdaCore/spark2014, accessed June 11, 2025.

29 AdaCore, n.d., “AdaCore NVidia: Joining Forces to Meet the Toughest Safety and Security Demands,” https://www.adacore.com/nvidia, accessed June 11, 2025.

30 See the Project Everest website at https://project-everest.github.io.

Project Everest’s artifacts are implemented and verified using a programming language called F*.31 Like Rocq’s Gallina and Isabelle, F* is a functional programming language, but unlike those two, verification relies heavily on the use of automated SMT solvers. This automation aims to reduce human engineering effort, but it can introduce problems such as proof instability,32 which increases maintenance costs. To mitigate these problems, F* developers can leverage a framework called Meta-F* to perform tactic-based proofs, in all or in part.33

In any engineering organization, if an outside team presents a new technology, no matter how valuable it is, it is unlikely that the team understands all the nuances of integrating such a technology into a product’s engineering system. And a change that involves new languages, new compilers, and so forth, brings along additional hurdles to adopting worthwhile new technologies. Project Everest was no different, and while engineering teams recognized the value of formal verification, the specifics of incorporating such a change were daunting.

One compelling feature that aided the wide deployment of Project Everest artifacts is the ability to compile a well-behaved subset of F*, called Low*,34 to readable code written in C. This code can, in turn, leverage assembly code verified in an F* framework called Vale.35 This allowed the subset of engineers who are skilled in the intricacies of F* to write the formal specifications and go through the process of verification and then produce C code. The C code could then be added to the project, and the large, existing tool chain of the engineering system could work on what was familiar to it. All the important tools—compilers, linkers, debuggers, deployment, and signing—continued as before, only with better source code. As a bonus, the generated code was even human-readable, which addressed the non-technical problem of how to ensure that the rest of the engineering system “trusted” the generated code.

An early success for Microsoft in this space was EverParse,36 an offshoot of Project Everest that has the goal of generating provably correct parsers. Code that interprets files, such as a photograph encoded in JPEG format, is notoriously hard for humans to write and has been the subject of a wide variety of security issues on all platforms.

___________________

31 See the F*lang website at https://fstar-lang.org.

32 Proof instability occurs when simple, non-functional changes to code, such as renaming variables or reordering definitions, cause automated proofs to fail or time out when they succeeded previously. The root cause of such instability relates to the way that proof obligations are translated from the code into formulae and conjectures given to the SMT solver.

33 G. Martínez, et al., 2019, “Meta-F: Proof Automation with SMT, Tactics, and Metaprograms,” European Symposium on Programming, Springer International Publishing.

34 J. Protzenko, J. Zinzindohoué, A. Rastogi, T. Ramananandro, P. Wang, S. Zanella-Béguelin, A. Delignat-Lavaud, et al., 2017, “Verified Low-Level Programming Embedded in F*,” Proceedings of the ACM on Programming Languages.

35 A. Fromherz, N. Giannarakis, C. Hawblitzel, B. Parno, A. Rastogi, and N. Swamy, 2019, “A Verified, Efficient Embedding of a Verifiable Assembly Language,” Proceedings of the ACM on Programming Languages.

36 T. Ramananandro, A. Rastogi, and N. Swamy, 2021, “EverParse: Hardening Critical Attack Surfaces with Formally Proven Message Parsers,” Microsoft Research Blog.

EverParse was used to define the VMSwitch component in Microsoft’s Hyper-V hypervisor. The hypervisor is the most trusted layer of software, and the VMSwitch component is responsible for routing packets from the network to virtualized network cards among virtual machines. A critical piece of software, parsing data at high speed from untrusted sources, the VMSwitch component was a perfect candidate for being formally verified. The resulting code fit into the existing toolchain smoothly and ended up showing performance improvements as well.

From that success, EverParse found use in other message parsing components, and Everest is being deployed to address critical components that have been subject to attack.

AWS IAM Authorizer

In early 2024, Amazon Web Services (AWS) deployed a formally verified replacement of its customer-facing authorization engine. This engine evaluates requests to access AWS-hosted resources, like storage buckets and computation instances, against Identity and Access Management (IAM) policies written by the AWS customers that own those resources. This authorization engine is used to secure access to more than 200 fully featured services and is invoked more than 1 billion times per second.37 The engine constitutes the first successful application of formal methods to build a performant, functionally equivalent replacement for a highly scaled, legacy system, as opposed to either a new system built with formal methods (as with seL4 and iFACTS) or a system implementing a tightly specified standard (as is the case with CompCert, for C, and Project Everest, for cryptographic algorithms and network protocols).

The IAM authorization engine was implemented and verified using the programming language Dafny.38 Unlike the languages discussed above, Dafny is not primarily a functional programming language, but instead supports both functional and imperative paradigms commonly in use in mainstream languages. As with F*, verification relies on the use of automated SMT solvers, oftentimes with human guidance. Just as the F* team defined a subset of F* called Low* that could be compiled in a readable way to a mainstream language (C), the AWS team defined a subset of Dafny called DafnyLite that they compiled to readable, “idiomatic” Java code, essentially as a transliteration of the Dafny original. This idiomatic, mainstream Java code is what is ultimately deployed, and it provides the benefits of reviewability by domain experts who are not familiar with Dafny, and debuggability in operational settings, mentioned above. Notably, the formally verified authorizer answers authorization requests three times faster than the legacy one.

___________________

37 A. Chakarov, J. Geldenhuys, M. Heck, M. Hicks, S. Huang, G. A. Jaloyan, A. Joshi, et al., 2025, “Formally Verified Cloud-Scale Authorization,” Amazon Science, https://www.amazon.science/publications/formally-verified-cloud-scale-authorization.

38 R. Leino, 2023, “The Dafny Programming and Verification Language,” https://dafny.org.

Usability of Formal Methods

As the previous discussion has emphasized, the difficulty of creating and proving formally verified software poses a major limitation on the scale of adoption of formal methods. Although some schools include education in formal methods in their computer science programs, that education is not mandatory—it is almost always possible to earn a degree in computer science or software engineering without learning to apply formal methods. In addition, as discussed above, the tools used to specify and verify programs are often challenging.

Encouraging the teaching of formal methods is one potential path to broader adoption. As DARPA supported the teaching of VLSI design in the 1980s, it (or other agencies such as the National Science Foundation) might consider programs to encourage the development of textbooks, examples, and access to tools for educational purposes.

Investments in the usability of formal methods would complement investments in teaching and might need to be a prerequisite to an effort to broaden formal methods education. In particular, the emerging capabilities of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) should be explored for their potential. Some areas of potential focus for such investments include the following:

- Development and broad release of reusable models for common components, tools, and languages such as x86, ARM, C++, and other widely used “systems.” Such models are hard and costly to build, but if widely used, they would provide a foundation for broad application of formal methods.

- Tools and AI models to help programmers construct proofs. Such tools (and related tooling such as SAT, SMT, and linear programming solvers) already help with low-level details of proof, such as arithmetic constraints.

- AI-based tools for translating requirement prose into formal specifications or creating specifications from test cases.

- Development of tools for domain-specific logics and frameworks. Advances such as separation logic or incorrectness logic, and associated frameworks such as Iris, F*, and Dafny, have made modular reasoning for realistic software a reality. But the tools to support these logics and frameworks are still relatively primitive and poorly integrated into production software pipelines.

While it seems likely that application of formal methods will be difficult for the near future, investments in usability can reduce the barriers and help to increase the number of programs that benefit from formal methods.

Discussion

The formal methods success stories presented above have the following two common features: the verified artifacts are security and/or safety critical and in wide use (at least in terms of their software category), and the verification work was carried out by experts over an extended period of time.

The specification and verification of the software involved developers with specific training—for most, they were earning a PhD or already had one in a verification-related field. This is because the core human functions of verification involve rigorous, mathematical thinking. These functions are very difficult for most people, and no amount of tool support can make them completely accessible. Even as automation for carrying out proofs has improved (the Everest and AWS IAM work both leveraged SMT solvers extensively, which have been independently improving for years39), there is still the task of precisely writing down the specification. A precise, correct specification is especially important for components with security ramifications. And, for now, a significant part of doing verification proofs is human-driven and requires a nontrivial degree of ingenuity.

The substantial costs of carrying out verification, both in terms of leveraging rare human resources and giving them the time to do their work, strongly influence the kinds of components that it makes sense to verify. The artifacts discussed all have three key features—they are security and/or safety critical, they are in heavy use, and in most cases they are not too large in terms of code size. Both compilers (like CompCert) and operating systems (like seL4) are core components used to build or execute essentially all computing systems, including security critical ones, and bugs in these components can result in highly dangerous vulnerabilities. The cryptographic algorithms implemented by Everest are in broad use for privacy-ensuring, trusted network communications (which make up most communications on the Internet today), as are the communications protocols implemented by it. The AWS IAM Authorizer is also security critical and in heavy use by AWS customers. The fact that all of these artifacts are not too large means that extra development costs for verification are not too large either. SPARK’s iFACTS air traffic control domain is safety critical and iFACTS remains in heavy use today, more than 10 years after it was deployed. It is an outlier in terms of its size, at 250,000 lines of code, which demonstrates what is possible in terms of scale. The committee’s hypothesis is that improvements in tools since its creation in the late 2000s would significantly reduce the effort to build something like it today.

The tools for carrying out formal methods today have dramatically improved compared to where they were a couple of decades ago. Verification languages like Rocq, F*,

___________________

39 S. Kochemazov, A. Ignatiev, and J. Marques-Silva, 2021, “Assessing Progress in SAT Solvers Through the Lens of Incremental SAT,” In Theory and Applications of Satisfiability Testing–SAT 2021: 24th International Conference, Barcelona, Spain, July 5–9, 2021, Proceedings 24, pp. 280–298, Springer International Publishing.

and Dafny (and many others) have been integrated into mainstream interactive development environments (IDEs) to ease their hands-on use. Libraries of proved-correct components, and of useful theorems, have dramatically expanded. Proof automation has also dramatically expanded, with the rise in efficiency of SMT solvers, as well as the rise of AI-based methods. And proof verification is readily and easily integrated into continuous integration (CI), continuous deployment (CD) pipelines.

Formal Methods and Cyberphysical Systems

Many DoD systems, such as sensors, flight controllers, and robots, integrate physical components with multiple software agents into hybrid, embedded, and cyber-physical systems (CPS). Reasoning holistically about assurance for CPS requires different kinds of models and methods than pure software systems. For example, one challenge is integrating control-theoretic models that use continuous mathematics to model physical components with the typically discrete models used for software. Another key challenge is the inherent real-time nature of most CPS.

There is a long tradition of research and development of formal methods for CPS that are not covered here. A relatively recent overview of the field can be found in Alur’s Principles of Cyber-Physical Systems,40 which discusses a “diverse set of subdisciplines including model-based design, concurrency theory, distributed algorithms, formal methods of specification and verification, control theory, real-time systems, and hybrid systems” (p. xi). The committee agreed that CPS assurance is important enough, particularly for safety and security, that like AI, it deserves a separate analysis and study to complement the discussion in this report.

Advocating for Formal Methods

While technological advances are a key enabler of the formal methods success stories, another important lesson is the way formal methods advocates at companies such as Amazon and Microsoft have persuaded product leaders to use the technology. For decades, the argument has been that formal methods, despite their costs, are the only (or best) way to achieve a sufficient level of assurance. This sort of argument, at some level captured in government standards, drove initial uses of SPARK in the 1990s. However, the inability to quantify the assurance benefits against the higher development and maintenance costs impeded that argument from taking hold in the mainstream. The Project Everest and AWS IAM teams addressed this problem by arguing that the high assurance offered by formal methods is not the sole reason to use them, but rather that for applications where high security assurance is a given (and is otherwise established through substantial code review and testing), the use of formal methods is an enabler of

___________________

40 R. Alur, 2015, Principles of Cyber-Physical Systems, MIT Press.

a greater good. It can increase development agility, which in turn leads to a faster (and measurable) increase in software quality.41 Quoting the AWS IAM team’s paper on their work,

In 2019 we decided even more assurance was needed to allow our authorization system to evolve rapidly to meet AWS’s increasing scope and scale. Indeed, the challenge of ensuring the engine’s speed and correctness had increased over time, causing us to wrestle with the question: How do we confidently deploy enhancements to this security-critical component and know that backward compatibility and performance for existing customer workflows are preserved? (p. 2)

They felt that the level of assurance needed was sufficiently high and that traditional methods would take too long to achieve it. Formal methods allowed them to move faster.

While the obvious benefit of formal methods is assured correctness, it also endows two other benefits:

- Understanding: A precise formal specification is easier to read and understand than an optimized implementation. Thus, we can be more confident that changes we make are the right ones, since they are expressed as simple changes to the specification.

- Agility: Formal proofs make changes easier to deploy. This is because proofs give a strong guarantee that changes we make to the production code always precisely match our specification, i.e., they do what we intend. For example, if we want to optimize the engine, we can prove that the optimized version still meets the existing specification. If we wish to add a new feature, we can prove that the new specification is backward compatible with the old one before proving the new code satisfies it. (p. 2)

These theoretical benefits have translated into practical ones:

Using our new formal methods-driven development process, we have already been able to confidently—and swiftly—make changes to [our engine] after it was deployed. (p. 2)

___________________

41 B. Cook, 2024, “An Unexpected Discovery: Automated Reasoning Often Makes Systems More Efficient and Easier to Maintain,” AWS Security Blog, https://aws.amazon.com/blogs/security/an-unexpected-discovery-automated-reasoning-often-makes-systems-more-efficient-and-easier-to-maintain.

In announcements about the use of this formal methods capability, AWS leaders were pleased to point out that the performance benefit of the new engine was three times higher—customers already assumed a high degree of assurance, and now they were getting a substantial performance increase that translates into measurable (dollar) cost savings. The Project Everest and EverParse team could make a similar performance argument. The use of formal methods allowed them to optimize cryptography and parsing algorithms beyond what developers would otherwise be comfortable with. At the same time, the use of formal methods did not impose extra risks by overly complicating the existing development and operational processes. Readable, reviewable code in a mainstream language (either C or Java) was what was deployed.

All of this—technology improvements and a clearer understanding of the business case—has boosted industrial and research interest in formal methods, and so the future looks bright.

Memory-Safe Programming Languages

When one sets out to prove a property about critical software using formal methods, the immediate question is, what is the property being proved? The first property that comes to mind is correctness—that is, that the software does precisely what it is supposed to do. That is essentially what both seL4 and CompCert achieve. In both cases, their developers carefully specified the system’s desired behavior using mathematical logic, and then proved that the actual system code implements that behavior.

But correctness is not the only kind of property. One might be satisfied to prove less specific properties that are nevertheless extremely valuable, such as that the software is always responsive to requests, or that it never leaks private information. In this latter category of property, one can include memory safety. Why? A lack of memory safety turns out to leave a program open to a range of potentially devastating attacks.

For decades it was thought that memory safety could be achieved through more careful coding, or through deployment mechanisms that could mitigate memory safety vulnerabilities, but these interventions have not solved the problem. Memory safety violations continue to be one of the most prevalent and dangerous forms of software vulnerability. For example, Google’s Chromium team reported in 2021 that more than 70 percent of its security vulnerabilities were due to memory safety violations,42 which is just one of a half-dozen similar trends reported by Microsoft,43 Apple, Mozilla, and Linux kernel developers.44

___________________

42 The Chromium Projects, n.d., “Memory Safety,” https://www.chromium.org/Home/chromium-security/memory-safety, accessed June 11, 2025.

43 M. Miller, 2019, “Trends, Challenge, and Shifts in Software Vulnerability Mitigation,” https://github.com/Microsoft/MSRC-Security-Research/blob/master/presentations/2019_02_BlueHatIL.

44 A. Gaynor, 2021, “Quantifying Memory Unsafety and Reactions to It,” https://www.usenix.org/conference/enigma2021/presentation/gaynor.

One could imagine using formal methods to address this problem (and indeed formal methods is a possible vector for proving particular programs are memory safe45), but as discussed above, doing so currently requires special human resources and extra development time, and therefore does not scale beyond core, critical components.

Given all this, many leading companies have turned to a conceptually simple solution—carrying out software development using a programming language that ensures memory safety by default. The key observation is that memory safety vulnerabilities arise in programs written in C, C++, and assembly language. Other modern languages, such as Java, Swift, Go, C#, SPARK, or Rust, make it difficult or impossible to violate memory safety because their implementations strictly enforce memory abstractions. Rust has emerged as a particularly attractive option because such enforcement is very low cost, and thus it can offer performance on par with C or C++, both in terms of execution time and memory use.

What Is Memory Safety?

A software program is memory safe if it only accesses memory it is allowed to, according to the programming language’s definition. To explain, consider the following two examples:

- Suppose a program declares a region of memory accessible by variable name “buf” that is 512 bytes in length. What should happen if the program, when executed, attempts to access the 513th byte of “buf”?

- Suppose the same program specifically gives back (frees) the region referenced by “buf,” so that the region can be reused for some other purpose by the program. What happens if the program nevertheless continues to access that region via “buf”?

A memory-safe program will not allow such accesses. The first is a spatial safety violation (accessing memory beyond the bounds of a contained region), and the second is a temporal safety violation (accessing a region after it has been reclaimed). Such accesses can be disallowed by either (1) identifying programs that might have them and preventing them from being executed or (2) executing the program in such a way that an illegal access is made to be impossible or is blocked when it is attempted. The first is called static enforcement of memory safety, and the second is called dynamic enforcement (see Box 3-1).

___________________

45 N. Chong, B. Cook, K. Kallas, K. Khazem, F.R. Monteiro, D. Schwartz-Narbonne, S. Tasiran, et al., 2020, “Code-Level Model Checking in the Software Development Workflow,” Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE 42nd International Conference on Software Engineering: Software Engineering in Practice.

BOX 3-1 Static and Dynamic Enforcement

Static enforcement requires a program analyzer (as part of the compiler) to consider whether any possible input could result in a violation. This problem is inherently computationally difficult,a which means that a practical analyzer will always falsely reject some programs that are memory safe, forcing the programmer to refactor the program to work around the limitations of the analysis. Dynamic enforcement makes it easier on the programmer by deferring enforcement to execution time, but doing so imposes performance costs due to run-time checks and the additional meta data needed to support the checks. In practice, memory-safe languages use a mix of static and dynamic enforcement mechanisms, and in some cases offer programmers clear control of which they get.

__________________

a M. Might, 2015, “What Is Static Analysis?” https://matt.might.net/articles/intro-static-analysis.

Why Does Memory (Un)safety Matter Today?

Accessing memory illegally, especially by writing to it, has significant security ramifications. In particular, a clever attacker can send input to a program that causes it to illegally access a region of memory that controls or strongly influences how the program behaves. Thus, the attacker can change the program’s execution to varying degrees, in the worst case getting it to execute entirely new code of the attacker’s choosing; this is called a remote code execution attack. The first highly publicized example of such an attack was the Internet Worm in 1988.46 It exploited a memory safety bug in a popular program via a technique called a buffer overflow,47 getting the program to execute functionality that carried out additional attacks on other hosts.

In the decades since 1988, memory safety vulnerabilities have been at the core of many devastating attacks. For example, in 2001, the Code Red worm exploited a memory safety bug in the Microsoft Windows IIS web server and infected 300,000 machines in 14 hours. This worm and others motivated Bill Gates to send a famous email memo to Microsoft employees on January 15, 2002,48 which stated that “trustworthy computing” should become Microsoft’s highest priority and that “now, when we face a choice between adding features and resolving security issues, we need to choose security.” In the years that followed, both industry and academia significantly stepped up their efforts to blunt the effects of memory safety–based vulnerabilities. Recommended approaches included developing better coding practices,49 using code analysis,50 and automated

___________________

46 E.H. Spafford, 1989, “The Internet Worm Program: An Analysis,” ACM SIGCOMM Computer Communication Review.

47 ARS Staff, 2015, “How Security Flaws Work: The Buffer Overflow,” ARS Technica, https://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2015/08/how-security-flaws-work-the-buffer-overflow.

48 B. Gates, 2002, “Bill Gates: Trustworthy Computing,” Wired, https://www.wired.com/2002/01/bill-gates-trustworthy-computing.

49 M. Howard and D. LeBlanc, 2003, Writing Secure Code, Pearson Education.

50 W.R. Bush, J.D. Pincus, and D.J. Sielaff, 2000, “A Static Analyzer for Finding Dynamic Programming Errors,” Software: Practice and Experience 30(7):775–802.

testing (“fuzzing”)51 to find bugs before attackers could exploit them, and deploying mitigations that made any remaining vulnerabilities more difficult to exploit.

These mitigations included compiler-based approaches such as stack canaries52 and control-flow integrity,53 architectural approaches such as the NX bit54 to enforce that memory can be written to or executed but not both, and operating system–based approaches such as address space layout randomization.55

None of these approaches completely solved the problem. Even today, the difficulty of correctly coding complex systems and the practical challenges and limits of code analysis and automated testing mean that memory safety bugs continue to be introduced. (One should not assume that AI tools will solve this problem either, because they are trained on human-produced code, and large language models today tend to produce code with vulnerabilities.56) Attackers also continue to find ways to overcome defenses against exploitation of these bugs. As evidence of this, famously named vulnerabilities such as Heartbleed57 and EternalBlue58 have continued to appear, and by the end of 2024, memory-safety vulnerabilities still make up three of the top eight highest-impact classes of vulnerabilities in software.59

Using Memory-Safe Programming Languages, Especially Rust

Fortunately, memory safety is ensured by many high-level programming languages, meaning that any program you write in those languages and execute with its normal toolchain is sure to be memory safe. This applies for languages like Java, Go, Swift, Rust, SPARK, Scala, Haskell, and many others (with some caveats).60 The only two widely used high-level languages that are not memory safe are C and C++. These languages fail to enforce both spatial safety (ensuring memory region accesses respect their bounds) and temporal safety (ensuring that freed memory does continue to be used).

___________________

51 Wikipedia contributors, n.d., “Fuzzing,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Fuzzing&oldid=1286738009, accessed June 11, 2025.

52 C. Cowan, et al., 1998, “Stackguard: Automatic Adaptive Detection and Prevention of Buffer-Overflow Attacks,” USENIX Security Symposium, Vol. 98.

53 M. Abadi, et al., 2009, “Control-Flow Integrity Principles, Implementations, and Applications,” ACM Transactions on Information and System Security (TISSEC) 13(1):1–40.

54 Wikipedia contributors, 2024, “NX Bit,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=NX_bit&oldid=1256030390.

55 PaX Team, 2003, “PaX Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR),” http://pax.grsecurity.net/docs/aslr.txt.

56 T. Holz, 2025, “Unsafe Code Still a Hurdle Copilot Must Clear,” Communications of the ACM 68(2):95.

57 Blackduck, n.d., “The Heartbleed Bug,” https://heartbleed.com, accessed June 11, 2025.

58 Wikipedia contributors, n.d., “WannaCry Ransomware Attack,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=WannaCry_ransomware_attack&oldid=1284581946, accessed June 11, 2025.

59 MITRE, 2024, “2024 CWE Top 25 Most Dangerous Software Weaknesses,” Common Weakness Enumeration, https://cwe.mitre.org/top25/archive/2024/2024_cwe_top25.html.

60 Most high-level languages offer a “foreign function interface” by which code in that language can call code written in another language, oftentimes C. Use of this FFI risks the called code introducing a vulnerability. High-level languages also often offer some “unsafe” functions or linguistic constructs that can violate memory safety. These are meant for rare, expert use. Oftentimes, it is easy to check that a program does not use these unsafe components. See D. Terei, S. Marlow, S. Peyton Jones, and D. Mazières, 2012, “Safe Haskell,” Proceedings of the 2012 Haskell Symposium.

At the time memory-safety vulnerabilities started becoming a serious issue, C and C++ were enormously popular, and the idea of moving away from them was essentially unthinkable; mitigations and better engineering practices for C and C++ seemed to make sense. But even by the end of the 2000s, it was becoming clear that memory safety is not a practical expectation for programs written in these languages. Thus, began substantial efforts to design and build new, systems-oriented programming languages targeting the same sorts of applications that seemed to require the use of C or C++. These languages include Go (from Google, starting development in 2007), Rust (from Mozilla starting in 2009 and now sponsored by the Rust Foundation), and Swift (from Apple, starting development in 2010). Rust has emerged as particularly attractive because its storage and execution models are very similar to those of C and C++, which target native code and use manual memory management rather than garbage collection.61 Rust code thus enjoys similarly good performance to C and C++ and good interoperability. And it is well designed and implemented. Stack Overflow’s annual developer survey has rated Rust the most admired language for 9 years in a row.62

Tech companies, including Amazon, Microsoft, and Google, are now using Rust both to rewrite legacy code and to build new code. AWS has used Rust to build infrastructure that powers its flagship Lambda, EC2, and S3 services,63 as well new functionality such as the Cedar authorization language.64 Microsoft is rewriting parts of the Windows kernel in Rust, including the font parser and graphics driver.65 A 2022 statement by the chief technology officer of Microsoft’s Azure cloud service declared that new code projects should be written in Rust rather than C and C++.66 At Google, more than 1,000 developers contributed Rust code to various projects in 2022. Both the Android platform and the Chromium browser incorporate Rust actively. Android encourages development of new services, libraries, drivers and even firmware in Rust,67 while third-party libraries

___________________

61 A garbage collector is a language-embedded automatic memory manager. Rather than requiring the programmer to decide when memory regions should be reclaimed, which can lead to temporal safety violations or memory leaks, the garbage collector performs reclamation safely and automatically. The downside is that it may force a change in how objects are represented, complicating interoperability, and takes extra time to find the objects to reclaim.

62 Stack Overflow, 2024, “Admired and Desired,” https://survey.stackoverflow.co/2024/technology#admired-and-desired.

63 M. Asay, 2020, “Why AWS Loves Rust, and How We’d Like to Help,” AWSOpen Source Blog. https://aws.amazon.com/blogs/opensource/why-aws-loves-rust-and-how-wed-like-to-help.

64 M. Hicks, 2023, “Using Open Source Cedar to Write and Enforce Custom Authorization Policies,” AWS Open Source Blog, https://aws.amazon.com/blogs/opensource/using-open-source-cedar-to-write-and-enforce-custom-authorization-policies.

65 D. Weston, 2023, “Default Security,” presentation given at BlueHatIL, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8T6ClX-y2AE&t=3000s.

66 T. Claburn, 2022, “In Rust We Trust: Microsoft Azure CTO Shuns C and C++,” https://www.theregister.com/2022/09/20/rust_microsoft_c.

67 Comprehensive Rust, n.d., “Welcome to Rust in Android,” https://google.github.io/comprehensive-rust/android.html, accessed June 11, 2025.

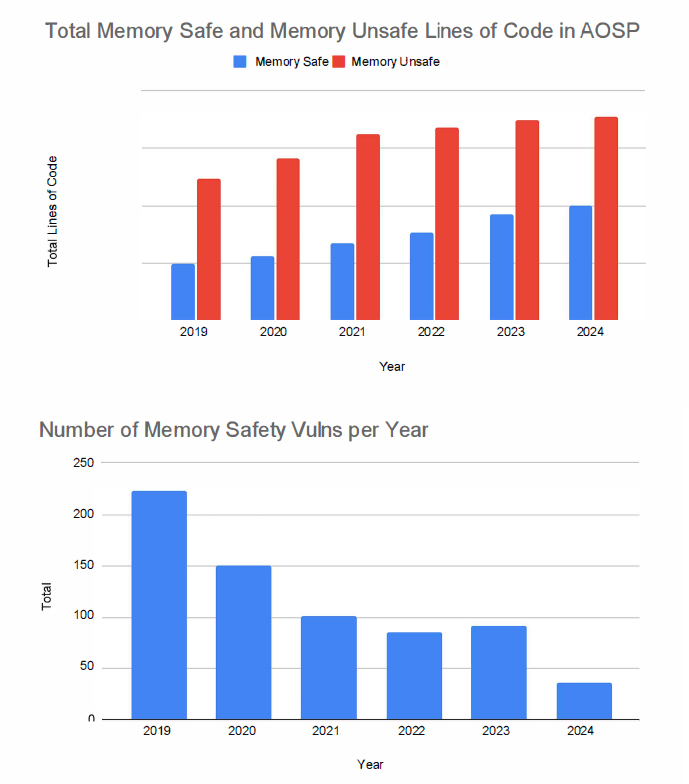

written in Rust can be linked into Chromium.68 The Android team has been using Rust long enough that it has been able to quantify the benefit as follows: “memory safety vulnerabilities in Android dropped from 76 to 24 percent over 6 years as development shifted to memory safe languages” (Figure 3-2).69 Here, the percentage refers to the fraction of vulnerabilities caused by memory safety issues, where the industry norm is around 70 percent. The decay in vulnerabilities was effectively exponential, in essence, as C- and C++-based vulnerabilities were found and fixed, and since no new ones were introduced, the total count of vulnerabilities dropped at the expected rate.70 Separate data from within Google finds that developer productivity when using Rust is up to two times greater than when using C and C++, when all costs are taken into account.71 Internal surveys also show that developers training to learn Rust reach a comfortable level of productivity in only a few months in most cases.

Developing only new code in Rust (or another memory safe language) is perhaps the easiest adoption path, but sometimes it is worth redeveloping (porting) particularly high-security components. This same argument has won the day for the use of formal methods; for example, for CompCert and the AWS IAM authorizer. Such redevelopment is starting to happen. In early 2024, Microsoft put out a call for developers to help port its own C# code to Rust.72 The Internet Security Research Group’s (ISRG’s) Prossimo project has been rewriting core open-source elements of critical libraries (e.g., NTP, DNS, TLS) in Rust for several years.73 Google has even explored porting components written in Go into Rust, for better performance.74 Automated techniques, such as those leveraging generative AI, could accelerate porting to Rust, which is the goal of DARPA’s TRACTOR program.75

A concerted push for the use of memory-safe languages (or at least memory-safe libraries like hardened libc++,76 execution platforms like CHERI,77 or compilers/extensions

___________________

68 Comprehensive Rust, n.d., “Welcome to Rust in Chromium,” https://google.github.io/comprehensive-rust/chromium.html, accessed June 11, 2025.

69 J. Vander Stoep and A. Rebert, 2024, “Eliminating Memory Safety Vulnerabilities at the Source,” Google Security Blog, https://security.googleblog.com/2024/09/eliminating-memory-safety-vulnerabilities-Android.html.

70 N. Alexopoulos, M. Brack, J. Philipp Wagner, T. Grube, and M. Mühlhäuser, 2022, “How Long Do Vulnerabilities Live in the Code? A Large-Scale Empirical Measurement Study on FOSS Vulnerability Lifetimes,” In 31st USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 22).

71 T. Claburn, 2024, “Rust Developers at Google Are Twice as Productive as C++ Teams,” The Register, https://www.theregister.com/2024/03/31/rust_google_c.

72 R. Speed, 2024, “Microsoft Seeks Rust Developers to Rewrite Core C# Code,” The Register, https://www.theregister.com/2024/01/31/microsoft_seeks_rust_developers.

73 Internet Security Research Group, 2025, “Memory Safety,” https://www.memorysafety.org.

74 T. Claburn, 2024, “Rust Developers at Google Are Twice as Productive as C++ Teams,” The Register, https://www.theregister.com/2024/03/31/rust_google_c.

75 DARPA, 2024, “Eliminating Memory Safety Vulnerabilities Once and for All,” https://www.darpa.mil/news/2024/memory-safety-vulnerabilities.

76 A. Rebert, M. Shavrick, and K. Yasuda, 2024, “Retrofitting Spatial Safety to Hundreds of Millions of Lines of C++,” Google Security Blog, https://security.googleblog.com/2024/11/retrofitting-spatial-safety-to-hundreds.html.

77 R. Watson, S. Moore, P. Sewell, B. Davis, and P. Neumann, 2023, “Capability Hardware Enhanced RISC Instructions (CHERI),” University of Cambridge Department of Computer Science and Technology, https://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/research/security/ctsrd/cheri.

SOURCE: J. Vander Stoep and A. Rebert, 2024, “Eliminating Memory Safety Vulnerabilities at the Source,” Google Security Blog, https://security.googleblog.com/2024/09/eliminating-memory-safety-vulnerabilities-Android.html.

like Fil-C78 or Checked C79) has gained momentum in recent years. Recommendations have been made by the government (e.g., the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency80) as well as academia and industry81 to standardize and/or otherwise require the use of memory-safe languages in most security-relevant settings. This push has been

___________________

78 F. Pizlo, 2025, “The Fil-C Manifesto: Garbage In, Memory Safety Out!” Github (blog), https://github.com/pizlonator/llvm-project-deluge/blob/deluge/Manifesto.md.

79 D. Tarditi, 2024, “Checked C,” Github (repository), https://github.com/checkedc/checkedc.

80 Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, 2023, “The Case for Memory Safe Roadmaps,” https://www.cisa.gov/case-memory-safe-roadmaps.

81 R. Watson, J. Baldwin, D. Chisnall, T. Chen, J. Clarke, B. Davis, N. Filardo, B. Gutstein, G. Jenkinson, B. Laurie, and A. Mazzinghi, 2025, “It Is Time to Standardize Principles and Practices for Software Memory Safety,” Communications of the ACM.

driven by the existing adoption of memory-safe programming languages and the realization that their benefits very often outweigh their costs.

Engineering with Legacy Code

Despite industry-wide goals of moving to safer languages and techniques, there is an enormous amount of code written in unsafe, legacy languages such as C, C++, or worse. These codebases will be still extant and in wide use for the foreseeable future; the sheer amount of code makes it infeasible for the owners or consumers to migrate to new code.

Change to an existing codebase incurs risk—commonly referred to as the regression rate. During the course of normal engineering, the regression rate is comparatively low. The regression rate ticks up as the code gets older; new engineers may not fully grasp what the code is accomplishing, nor may they entirely understand the behavior of the code as it is, rather than how it was envisioned.

Formal methods are of little help once developers no longer remember what the specification is intended to be. Formal methods work when the desired functionality can be completely specified. If an engineer is unable to articulate completely what an existing library does, formal methods will not help. Instead, there will be a provably correct subset of the functionality instantiated in the new methods, and existing customers will encounter gaps and regressions.

Still, software publishers are finding ways to incorporate better engineering practices to reap benefits.

Static Analysis

Static analysis tools continue to gain functionality and deliver results. From humble beginnings as the “lint checker,” static analysis tools now have the ability to perform high-level syntactic scans and model code and data flow. Such tools have also evolved from a task run at specific times to add-ons that can integrate with the development process, either at the desktop for the individual developer, or in the larger-scale engineering process. There are numerous static analysis tools, both commercial and open source, and new tools and enhancements to existing tools are released often. A Wikipedia article82 gives a sample of the number and variety of tools.

Dynamic Analysis

Dynamic analysis tools also gain functionality as software publishers seek to identify weak areas within their software products. From the humble beginnings where fuzzers would just flood interfaces with random data hoping for a crash, dynamic tools have

___________________

82 Wikipedia contributors, 2025, “List of Tools for Static Code Analysis,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=List_of_tools_for_static_code_analysis&oldid=1285981928.

evolved substantially. Current modern fuzzers have sufficient understanding of the network protocols or invocation patterns to exercise code deep within the software product or component. Dynamic tools are also starting to leverage generative AI frameworks to generate their test patterns, further automating the process and allowing the human programmer to focus on less repetitive tasks.

As with static analysis tools, there are numerous fuzzing tools, both commercial and open source. An article in CSO Online lists some major offerings as of 2022.83

Code Update

There are times when code needs to be updated or rewritten, accepting the risk of regression (hopefully mitigated by other means). As noted above, code that reaches this state is often old, and the current engineering staff may not be as familiar with it as they were in the past.

A promising technique here involves using generative AI models to update and replace old code patterns with better ones. The AI model can remove the old code and replace it with more modern code, including updating the semantics of the code usage, in an automated fashion. This technique promises more reliable code updates for systems where updates were deemed higher risk.

Developer Practices

In many ways, software engineering remains a labor-intensive operation. People write code by typing into their Interactive Development Environment (IDE) and editor of choice; the code is compiled into the actual software product, and then the results are rolled out and tested. The compilation process itself can be time consuming and incorporates the work of many developers. In the enterprise software world, new code can be evaluated and rolled out to web services almost immediately. In the embedded and platform world, there is further testing as the code is applied to emulators, virtual machines, and devices, as a step toward broader testing and evaluation.

As with many endeavors, the human aspect of software development is both the area where small technical improvements can create large gains, and where small behavioral improvements can create even larger gains. Understanding and improving the developer experience and environment is critical for assurance as well as agility.

Tools

The past decade has seen a shift toward automating the downstream aspects of the engineering process—the compilation and testing portions—so that human interaction

___________________

83 J. Breeden, 2022, “10 Top Fuzzing Tools: Finding the Weirdest Application Errors,” CSO Online, https://www.csoonline.com/article/568135/9-top-fuzzing-tools-finding-the-weirdest-application-errors.html.

is limited and more scale can be achieved through automation. To qualify this change, the term “shift left,” which has come to encompass both considering security as part of architecture and design and moving the line where human interaction ends and automation begins, further left in the timeline, increasing the amount of automation in the whole process. The more testing and evaluation, including static and dynamic analysis, that can happen earlier in the process, the smoother the whole pipeline can be.84

The key to this progress, of course, remains the actual developer. The developer is still the one that needs to synthesize the ideas in the specification and architecture into working code, even if they are making use of generative AI code assistants. The more time that an individual developer can spend on the creative process, and less on downstream activities like debugging, the more efficient the developer can be. Sometimes referred to as the “dev inner-loop,” the logical consequence to shifting automation as far left as possible is to optimize how the developers spend their time. All efforts to improve the code at the left-most point, where the developer is typing, pay off by reducing the downstream workload.

Developer Behavior

The model of “Golden Path,” “Developer Guardrails,” or even the pithier “Pit of Success” is the carrot rather than the stick. Imposing standards for coding practices can be difficult—anything that is not automatically validated by the tools is likely to be implemented unevenly. Shifting the approach to make it easier to do the right thing than any other approach yields good results.

For example, Google identified that its different cloud services had different implementations of its access control model. Different implementations would have different semantics, even if the differences were slight, that could create a vulnerability that could be later exploited by an attacker. Google’s solution was two-fold. First, a common library was created by the security team that served as the reference implementation. Its behavior was verified to the extent possible, and the implementation became core to many services.

So far, this is fairly standard engineering—create a library to implement some common functionality. The shift comes from the engineering incentives around the library. If a team used the library correctly and consistently, as confirmed by static checks carried out by a vertically integrated application framework and developer platform, their security reviews were expedited. If they did not use the library, then the team’s service would be subject to additional security reviews. Reviews take time, the service would not roll out as quickly as hoped, and engineers would not get their bonuses. Engineers were

___________________

84 Department of Defense (DoD), 2020, Agile Software Acquisition Guidebook, https://www.dau.edu/sites/default/files/Migrated/CopDocuments/AgilePilotsGuidebook%20V1.0%2027Feb20.pdf.

incentivized to fall into the “Pit of Success” by not creating their own libraries and using the common, high-assurance libraries.85

This pattern is not unique to Google and has shown success in other contexts. However, the more complicated the functionality treated this way, the more likely the library will need to adjust its semantics and grow in functionality. A common case is a relatively simple library—for example, cryptographic functionality, where the library encapsulates simple key management, encryption, and decryption operations. Because it is simple, it is easily adopted by different teams as they abide by the guardrails.

However, a complete security protocol such as the Transport Layer Security (TLS)86 is vastly more complicated, entailing not just the use of encryption for its core functionality, but also key management policy, logging, error handling, performance optimizations, and more. As the complexity grows, so grows the likelihood that a given team will need to add or extend capabilities in the library. Managing this growth correctly enables great efficiencies, but only if the risks are handled appropriately.

COMMERCIAL OFF-THE-SHELF VENDORS AND SECURE DEVELOPMENT

The frequent need for computer users to update (patch) COTS software to correct security vulnerabilities has been a source of frustration since at least the beginning of the 21st century. Government customers, like their commercial counterparts, have shared this frustration.

In late 2001, two major network worms affecting Windows, Code Red and Nimda, caused an upsurge in customer complaints to Microsoft. In response, the Microsoft Windows team conducted what it called a “security push”—what an operational DoD command might refer to as a stand-down—with the aim of identifying and removing as many software vulnerabilities as feasible.87 After a 2-month stand-down and about 9 months of follow-up efforts, Microsoft released Windows Server 2003, its first major product release that demonstrated significant security improvements over its predecessor.