Review of the Army's Technical Guides on Assessing and Managing Chemical Hazards to Deployed Personnel (2004)

Chapter: Appendix C Example Use of Probits for Developing Chemical Casualty Estimating Guidelines

Appendix C

Example Use of Probits for Developing Chemical Casualty Estimating Guidelines

INTRODUCTION

Chemical casualty estimating guidelines (CCEGs) were introduced by the subcommittee for the purpose of better informing commanders of potential decrements in troop strength that might jeopardize the ability of troops to successfully complete missions. The CCEGs will provide data sets that can be used quantitatively to estimate the nature and extent of impacts on mission performance. Specifically, CCEGs are tools by which the severity of adverse outcomes to mission accomplishment can be estimated from chemical concentrations. Generally they will be set for atmospheric compounds whose toxic potency is quite high. The application of these tools will generate specific response rates (e.g., 25%, 50%) for defined concentrations of chemicals in the breathing zone of military personnel.

The health impacts of chemical agents generally form a continuum from mild physical or sensory alterations—such as mild skin irritation—that pose distractions but are easily accommodated, to impairment of vision and balance that might limit effective use of battlefield equipment, to central nervous system (CNS) depression that would limit necessary cognitive functions, to asphyxiation or serious organ damage and failure leading to death. The medical outcome depends directly on the delivered dose and the inherent toxicity of the chemical. For airborne substances, exposures are characterized by the concentration(s) in air at the breathing zone and the duration of contact.

For field commanders to make informed choices between one course of action and another, arguably less dangerous one (within the context of an assortment of many types of risks), appropriate comparisons must be made. Two types of information in particular are needed to make such comparisons of estimated impacts on troop viability and vulnerability: (1) the severity of the immediate medical consequences during the course of the mission, and (2) the likely number of troops affected in the exposure scenario envisioned during the course of the specific mission.

OBJECTIVE

The purpose of the exercise reported herein is to explore the feasibility of using an approach that relies in part on probit analysis to describe, for three levels of severity (mild, moderate, and severe), the expected exposureincidence response for the reasonably healthy young adults that comprise the deployed population. As discussed in Chapter 4, this is not a definitive protocol for how to develop CCEGs. Rather, it is an example of one possible approach. The subcommittee recommends that the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) develop guidance for establishing CCEGs and have that methodology peer-reviewed before application (see Chapter 4).

This analysis focuses on inhalation as the dominant pathway of exposure for military personnel. Unlike military exposure guidelines (MEGs) and other methods to identify levels of exposure that are unlikely to cause injury, the CCEGs (as envisioned here) are media-specific chemical concentrations expected to cause health impairments sufficient to reduce unit strength and therefore pose what the Army calls a medical threat. They are designed to evaluate course-of-action options that are expected to involve chemical exposures. Combat situations can result in human casualties that, although undesired, must nevertheless be tolerated to achieve military objectives. With that in mind, CCEGs allow commanders to weigh chemical risks against other operational risks and decide which chemical risks should be avoided and which must be borne for the sake of the mission.

Note that the approach described herein is intended to produce information about potential health impacts in a form that would allow field commanders to compare the impacts on the achievability of mission objectives from an assortment of chemical and nonchemical hazards that could degrade mission effectiveness. That is accomplished by using an approach that estimates the percentage of troops likely to be incapacitated (and the nature and duration of that incapacitation) by exposures to toxic agents.

Such output is comparable to outputs from other processes that estimate, for example, casualties from enemy fire or from weather conditions that might disable mechanized equipment.

APPROACH AND ORGANIZATION

The probit analysis the subcommittee envisions is predicated on having available incidence data for acute toxicity (i.e., for effects that materialize within minutes to several days following initial exposure). Those data must be reliable to provide useful guidance; peer-review is one major means of achieving the desired level of reliability and predictability.

To be most useful, the toxicity data should span three levels of severity:

-

Mild pathological responses. Most commonly sensory discomfort and irritation and some mild non-sensory effects observed in groups containing a range of normally distributed susceptibilities that would also be found in populations of healthy, young adults.

-

Moderate pathological responses. Temporarily debilitating systemic dysfunctions in groups containing a range of normally distributed susceptibilities that would be found in healthy, young adults.

-

Severe pathological responses. Reversible or irreversible damage to organ functions that is incapacitating, life-threatening, or actually lethal observed in groups comparable to healthy, young adults.

This scheme resembles the graded acute exposure guideline levels (AEGLs) of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (NRC 2001) in several respects, and similar classifications might be adopted for CCEGs.

The data should be subjected to some form of weight-of-evidence analysis in which the quality of the data are examined critically and the degree of consistency and concordance is evaluated closely. That process should include some decision rules for determining the relative value of and reliance on primarily human and secondarily animal data, and vice versa.

Several compounds were identified as prospective candidates for this feasibility exercise. The compounds are divided into two groups: (1) those for which AEGLs have been published (NRC 2000, 2002, 2003), and (2) a sampling of compounds identified in U.S. Army Center for Health Promotion and Preventive Medicine’s Technical Guide 230 (TG-230), but not included among the AEGLs, that would likely have some applicable incidence data. The compounds in each group are listed in Table C-1.

TABLE C-1 Candidate Compounds

|

Compounds in TG-230 with AEGLs |

Compounds in TG-230 with No AEGLs |

|

Aniline |

Acrolein |

|

Arsine |

Ammonia |

|

Diborane |

Benzene |

|

Dimethylhydrazine |

Carbon tetrachloride |

|

Hydrogen cyanide |

Carbon monoxide |

|

Hydrogen sulfidea |

Ethylene oxide |

|

Methyl isocyanate |

Formaldehyde |

|

Monomethylhydrazine |

Hydrazine |

|

Nerve agents: GA, GB, GD, GF, VX |

Methyl bromide |

|

Phosgene |

Toluene diisocyanate |

|

Propylene glycol dinitrate Sulfur mustard 1,1,1,2-tetrafluoroethane (HFC-134a) 1,1-dichloro-1-fluoroethane (HCFC-141b) |

|

|

aA draft AEGLs document is available, but has not yet been finalized. |

|

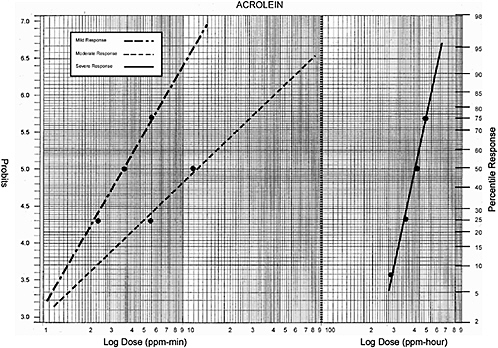

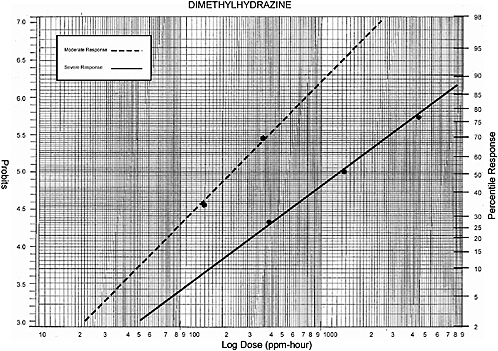

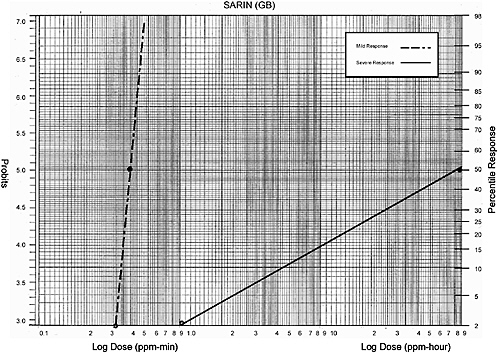

From among the candidate compounds, seven substances were selected, and their acute toxicity data was analyzed to obtain data relevant to the plotting of incidence on the basis of the three categories: mild, moderate, and severe. The dose unit selected for this exercise, a reflection of exposure via the inhalation pathway, is parts per million-hour (ppm-hour) (and ppm-minute [min] for acrolein), which is the product of concentration and time (C × t). To the extent possible, the same unit was used for all plots to simplify comparisons. Probits were plotted for the log-dose versus the log-percent response between 2% and 98% (see data sheets and graphs at the end of this appendix; note that the probit scale is on the left side of the plot). Each curve was derived by plotting the values for the data. Alternatively, however, probit values could also be calculated against log-dose. Indeed, calculating at least two probit values for each curve offers the advantage of being able to estimate any point on the curve in order to estimate the expected consequences for specific log-doses. In either case, the plots can be computerized to facilitate field comparisons of medical consequences from exposures to toxic agents.

Doses were obtained from data derived from observations of either humans or laboratory animals. For simplicity, uncertainty factors were not used in the analysis. However, when the selected doses were obtained from data from laboratory animals, consideration was given to adjusting the inhalation doses for differences in inhalation rates and metabolic rates between humans and the test species. When adjusting the doses, consideration

was given to the application of a methodology that was proposed by EPA (1994) in its guidelines for the derivation of reference concentrations (RfC) for substances present in ambient air. The subcommittee authoring this report chose its own set of relatively simple decision rules for these examples. Those rules were applied to achieve dose-equivalency for inhaled substances when using probit analysis to estimate the number of potential casualties from short-term exposures to toxic agents. Ultimately, DOD would need to develop its own approach and have it peer-reviewed. The decision rules used here apply solely to situations in which human doses are estimated from laboratory animals. They include the following:

-

If a substance causes local toxicity (e.g., skin or lung irritation), the inhaled concentration for humans is set equivalent to that obtained from the data in laboratory animals. This was applied to acrolein and sarin (“mild”).

-

If the substance causes systemic toxicity (e.g., CNS depression) and the effect is caused by the parent substance or stable metabolites (i.e., half-life measured in hours or more), the inhaled concentration for humans is set equivalent to that obtained from the data in laboratory animals. This was applied to aniline, hydrogen cyanide, and sarin (“severe”).

-

If the substance causes systemic toxicity (e.g., liver injury) and the effect is caused by the reactive parent substance or highly reactive metabolite(s) (i.e., half-life measured in minutes), the inhaled concentration for humans is estimated by adjusting the concentration obtained from the data in laboratory animals in accordance with the body weight of the species to the -0.75 power, because there exists considerable evidence for the validity of such a procedure (Clewell et al. 2002; NRC 2001). This was applied to dimethylhydrazine and propylene glycol dinitrate.

The results of this process were estimated doses for humans that were considered equipotent in their toxic severity.

FINDINGS

The compounds evaluated in detail are aniline, 1,1- and 1,2-dimethylhydrazine, hydrogen cyanide, propylene glycol dinitrate, acrolein, the chemical warfare agent sarin, and hydrogen sulfide. AEGLs values were available for all of these compounds except acrolein. The relevant information for each compound is described at the end of this appendix on two

pages: (1) a fact sheet with a summary of the relevant data for the subject compound and (2) the actual plot of the data.

These compounds span a range of chemical classes and acute toxicological manifestations. However, this is merely a small sample that was useful for an initial feasibility study; the exercise would need to be expanded to draw any firm, generalized conclusions about the validity of this means of data analysis and visualization.

With the exception of acrolein, the interpretations of the raw toxicity data on which the chemical plots were based were adopted directly from the AEGL documents (NRC 2000, 2002, 2003; EPA 2002). Reliance on those documents provides a strong element of peer-review that should minimize controversy about data selection and application. Note also that, in many cases, the dose-response relationships are bounded by only a few points and that some points require inference from the range of toxicological information available for a substance. Ultimately, however, the plots enable identification of all values along each curve.

The results indicate that, for the compounds examined, it is generally possible to obtain estimates of toxicological impacts within each of the three categorical groups of severity in terms of the fraction of a group impacted. The exception was dimethylhydrazine. There were no data on that chemical suitable to estimate the frequency of dose-dependent, mild adverse consequences. Also, the information on acrolein is somewhat different from that on the other compounds. For both mild and moderate impacts, the irritation effects are more time-dependent than they are for the other compounds; but for severe outcomes, the impact can be scaled by concentration, keeping time fixed.

Aniline and hydrogen cyanide had the most directly applicable data sets; the data sets for the other compounds were less robust for the purpose of this report. This leads to perhaps the most vital observation: this approach, regardless of its desirability, might be impractical for several reasons. First, the number of compounds having toxicity data in the form required for the approach to be functional appears to be very limited. Although many studies describe changes in pathological severity with increasing doses, they report far less often on the incidence rates in members of the groups observed. That is particularly true for human studies. Indeed, many human studies are merely case reports, and they have the added limitation of having either no exposure data or data that are highly imprecise.

Available animal studies of acute toxicity also have major limitations. Although most compounds have been tested for lethality (lethal dose in 50% of subjects [LD50] and lethal concentration in 50% of subjects [LC50]),

few have been tested for less severe effects. Only longer-duration studies report on sublethal effects and the frequency of responders. Another major limitation is the lack of statistical power. Studies deemed most toxicologically significant often have been performed in dogs or monkeys. Such studies frequently use only three to five experimental subjects per group. Thus, the points on the subcommittee’s probit plots appear to be more precise than they actually are. This limitation precluded the calculation of standard deviations around data points or confidence intervals around curves.

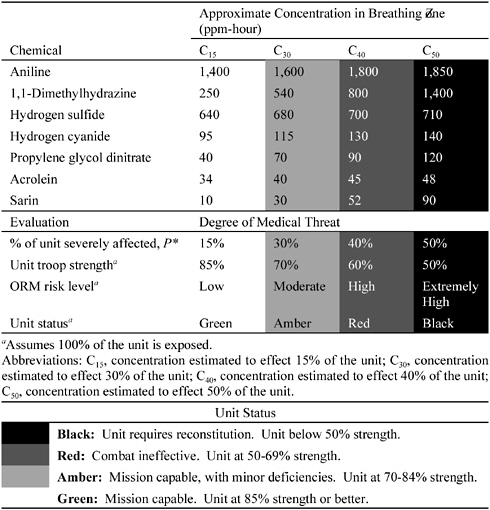

Table C-2 provides an example of how CCEGs could be used to estimate impacts on troop strength. For the seven example chemicals, the concentrations estimated to severely affect 15%, 30%, 40%, and 50% of the unit are tabulated to correspond to the affiliated operational risk-management (ORM) risk level and unit status, assuming that the fraction F of the unit exposed is F = 1.0 (i.e., that 100% of the unit is exposed). A measured or modeled concentration for a given chemical could be compared with the values in the table to estimate the potential impact on missions. (See Chapter 4 and Appendix E for how to estimate mission impacts for cases in which only a percentage of the unit is exposed. See Appendix E for how to estimate impacts from exposures to multiple chemicals.)

CONCLUSIONS

Military field commanders need reliable estimates of the nature and magnitude of health impairment resulting from toxic exposures to agents that could be encountered during missions that have military objectives. This process seems comparable to the estimation of battle casualties when planning missions with combat roles.

Estimating toxic effects that might impair the performance of deployed units during missions is theoretically possible by evaluating the limited number of acutely toxic agents that could be encountered in some battlefield conditions. However, the data needed to perform those evaluations and to obtain reliable estimates easy to use in the field (e.g., graphic representations) appear to be available for only some of the substances of interest to the military. Furthermore, for those compounds for which estimates are feasible and graphic displays are possible, the information should be applied with some understanding of the strengths and limitations of the data, and caution should be exercised to avoid placing too much confidence in the seeming precision of numerical values.

FACT SHEETS AND PROBIT PLOTS1

|

Acrolein |

|

|

Mild Effects—irritation of eyes, nose, and throat |

|

|

NOAEL (human) = 0.1 ppm for 8 hour |

|

|

Data (human) from Stevens et al. 1961: |

|

|

0.5 ppm-5 min |

25% response |

|

? ppm-min |

50% response (estimated) |

|

0.5 ppm-12 min |

90% response |

|

Mode of toxic action: local tissue damage on immediate contact, with increasing time of contact |

|

|

Allometric scaling: not applicable |

|

|

Uncertainty factors: none |

|

|

Data plotted for humans: |

|

|

2.5 ppm-min |

25% response |

|

3.8 ppm-min |

50% response (estimated) |

|

6.0 ppm-min |

75% response |

|

Moderate Effects—severe irritation of eyes, nose, and throat; respiratory distress |

|

|

Data (human) from Sims and Pattle 1957: |

|

|

1.2 ppm-5 min |

25% response |

|

2.5 ppm-5 min |

50% response (estimated) |

|

8 ppm-10 min |

75% response |

|

Mode of toxic action: local tissue damage on immediate contact, with increasing time of contact |

|

|

Allometric scaling: not applicable |

|

|

Uncertainty factors: none |

|

|

Data plotted for humans: |

|

|

6.0 ppm-min |

25% response |

|

3.8 ppm-min |

50% response |

|

? ppm-min |

75% response |

|

Severe Effects—respiratory failure to mortality |

|

|

Data (rat) from Smyth 1956 |

|

|

8 ppm-4 hour |

8% response |

|

10 ppm-4 hour |

25% response (estimated) |

|

12 ppm-4 hour |

50% response (estimated) |

|

14 ppm-4 hour |

75% response (estimated) |

|

Acrolein |

|

|

Mode of toxic action: local tissue damage on immediate contact, with increasing time of contact |

|

|

Allometric scaling: 1:1 for rat:human |

|

|

Uncertainty factors: none |

|

|

Data plotted for humans: |

|

|

32 ppm-hour |

8% response |

|

40 ppm-hour |

25% response |

|

48 ppm-hour |

50% response |

|

56 ppm-hour |

75% response |

|

Mode of Action: tissue damage on immediate contact, cumulative with time of contact |

|

|

Dose-duration relationship: linear, C1 × t = k (?) |

|

|

Delayed sequellae: decrements in respiratory function |

|

|

For comparison: |

OSHA PEL = 0.1 ppm-8 hour OSHA STEL = 0.3 ppm-15 min |

|

Aniline |

|

|

Mild Effects—clinical cyanosis without hypoxia |

|

|

NOAEL (human) = 5% MetHb |

|

|

Data (rats) from Kim and Carlson 1986: |

|

|

720 ppm-hour |

25% response (estimated from database) |

|

800 ppm-hour |

50% response (22-23% MetHb) |

|

880 ppm-hour |

75% response (estimated from database) |

|

Mode of toxic action: stable metabolite causing MetHb formation |

|

|

Allometric scaling: 1:1 for rat:human |

|

|

Uncertainty factors: none |

|

|

Data plotted for humans: |

|

|

720 ppm-hour |

25% response |

|

800 ppm-hour |

50% response |

|

880 ppm-hour |

75% response |

|

Source: NRC 2000 |

|

|

Moderate Effects—fatigue, lethargy, dyspnea, headache |

|

|

Data (rats) from Kim and Carlson 1986: |

|

|

1,080 ppm-hour |

25% response (estimated) |

|

1,200 ppm-hour |

50% response (41-42% MetHb) |

|

1,320 ppm-hour |

75% response (estimated) |

|

Mode of toxic action: stable metabolite causing MetHb formation |

|

|

Allometric scaling: 1:1 for rat:human |

|

|

Uncertainty factors: none |

|

|

Data plotted for humans: |

|

|

1,080 ppm-hour |

25% response |

|

1,200 ppm-hour |

50% response |

|

1,320 ppm-hour |

75% response |

|

Source: NRC 2000 |

|

|

Severe Effects—severe hypoxia to asphyxiation to death |

|

|

Data (rat) from Bodansky 1951, Kiese 1974, and Seger 1992: |

|

|

1,436 ppm- hour |

10% response |

|

1,600 ppm- hour |

20% response |

|

1,812 ppm- hour |

40% response (70-90% MetHb) |

|

2,120 ppm-hour |

70% response |

|

Mode of toxic action: stable metabolite causing MetHb formation |

|

|

Allometric scaling: 1:1 for rat:human |

|

|

Uncertainty factors: none |

|

|

Aniline |

|

|

Data plotted for humans: |

|

|

1,436 ppm-hour |

10% response |

|

1,600 ppm-hour |

20% response |

|

1,812 ppm-hour |

40% response |

|

2,120 ppm-hour |

70% response |

|

Source: NRC 2000 |

|

|

Mode of Action: MetHb formation at all levels |

|

|

Dose-duration relationship: linear, C1 × t = k |

|

|

Delayed sequellae: possible human carcinogen |

|

|

For comparison: |

|

|

AEGL-1 = 8 ppm-hour; 1 ppm-8 hour (includes UF of 10 for children) |

|

|

AEGL-2 = 12 ppm-hour; 1.5 ppm-8 hour (includes UF of 10 for children) |

|

|

AEGL-3 = 20 ppm-hour; 2.5 ppm-8 hour (includes UF of 10 for children) |

|

|

1,1- and 1,2- Dimethylhydrazine |

|

|

Mild Effects—slight tremors of extremities |

|

|

NOAEL (human): insufficient data |

|

|

Data: insufficient |

|

|

Mode of toxic action: reactive metabolite causing uncharacterized central nervous system effects |

|

|

Allometric scaling: not applicable |

|

|

Uncertainty factors: none |

|

|

Data plotted for humans: insufficient data |

|

|

Source: NRC 2000 |

|

|

Moderate Effects—muscle fasciculations, tremors, vomiting |

|

|

Data (dog) from Weeks et al. 1963: |

|

|

80-120 ppm-hour |

33% response |

|

200-250 ppm-hour |

66% response |

|

Mode of toxic action: reactive metabolite causing uncharacterized central nervous system effects |

|

|

Allometric scaling: (body weight)-0.75 |

|

|

Uncertainty factors: none |

|

|

Data plotted for humans: |

|

|

150 ppm-hour |

33% response |

|

390 ppm-hour |

66% response |

|

Source: NRC 2000 |

|

|

Severe Effects—convulsions to mortality |

|

|

Data (dog/rat/mouse/hamster) from Weeks et al. 1963 |

|

|

450 ppm- hour |

25% response (estimated) |

|

300 ppm- hour |

50% response |

|

3,300 ppm- hour |

66% response (estimated) |

|

Mode of toxic action: reactive metabolite causing uncharacterized central nervous system effects |

|

|

Allometric scaling: (body weight)-0.75 |

|

|

Uncertainty factors: none |

|

|

Slope (rat): 14.7 |

|

|

Data plotted for humans: |

|

|

450 ppm-hour |

25% response |

|

1,471 ppm-hour |

50% response |

|

4,950 ppm-hour |

75% response |

|

Source: NRC 2000 |

|

|

Hydrogen Cyanide |

|

|

Mild Effects—headache, weakness |

|

|

NOAEL (human) ≈ 5 ppm-8 hour/day, 5 day/week (NIOSH 1976) |

|

|

Data (human) from El Ghawabi 1975: |

|

|

8 ppm-hour |

25% response |

|

10 ppm-hour |

50% response |

|

12 ppm-hour |

75% response (estimated) |

|

Mode of toxic action: stable metabolite produces inhibition of cellular respiration |

|

|

Allometric scaling: not applicable |

|

|

Uncertainty factors: none |

|

|

Dose-duration relationship: log, C3 × t = 1 |

|

|

Data plotted for humans: |

|

|

8 ppm-hour |

25% response |

|

10 ppm-hour |

50% response |

|

12 ppm-hour |

75% response |

|

Source: NRC 2002 |

|

|

Moderate Effects—central nervous system depression |

|

|

Data (monkey) from Purser 1984 |

|

|

30 ppm-hour |

25% response (estimated) |

|

35 ppm-hour |

50% response (estimated) |

|

40 ppm-hour |

75% response (estimated) |

|

Mode of toxic action: stable metabolite produces inhibition of cellular respiration |

|

|

Allometric scaling: 1:1 for monkey:human |

|

|

Uncertainty factors: none |

|

|

Dose-duration relationship: log, C2 × t = k (monkey) |

|

|

Data plotted for humans: |

|

|

30 ppm-hour |

25% response |

|

35 ppm-hour |

50% response |

|

40 ppm-hour |

75% response |

|

Source: NRC 2002 |

|

|

Time to incapacitation (monkey): |

|

|

100 ppm |

19 min |

|

102 ppm |

16 min |

|

123 ppm |

15 min |

|

147 ppm |

8 min |

|

156 ppm |

8 min |

|

Hydrogen Cyanide |

|

|

Severe Effects—stimulation to depression to convulsions to coma to death |

|

|

Data (rat) from E. I. duPont de Nemours Company 1981: |

|

|

88 ppm- hour |

10% response |

|

108 ppm- hour |

25% response (estimated) |

|

139 ppm- hour |

50% response |

|

180 ppm-hour |

75% response (estimated) |

|

Mode of toxic action: stable metabolite produces inhibition of cellular respiration |

|

|

Allometric scaling: 1:1 for rat:human |

|

|

Uncertainty factors: none |

|

|

Dose-duration relationship: log, C2.6 × t = k (rat); C2 × t = k |

|

|

Data plotted for humans: |

|

|

88 ppm-hour |

10% response |

|

108 ppm-hour |

25% response |

|

139 ppm-hour |

50% response |

|

180 ppm-hour |

75% response |

|

Source: NRC 2002 |

|

|

Mode of Action: inhibition of cellular respiration |

|

|

Dose-duration relationship: varies with level |

|

|

Delayed sequellae: none known or anticipated |

|

|

For comparison: |

AEGL-1 = 2.0 ppm-hour; 1.0 ppm-8 hour AEGL-2 = 7.1 ppm-hour; 2.5 ppm-8 hour AEGL-3 = 15 ppm-hour; 6.6 ppm-8 hour |

|

Hydrogen Sulfide |

|

|

Mild Effects—eye pain, photophobia, headache, irritation |

|

|

Data (human) from WHO 1981 and Vanhoorne et al. 1995: |

|

|

6 ppm-hour |

0% response |

|

? ppm-hour |

50% response |

|

? ppm-hour |

75% response |

|

Mode of toxic action: direct effect on contact; edema systemically |

|

|

Allometric scaling: not applicable |

|

|

Uncertainty factors: none |

|

|

Dose-duration relationship: log, C4.4 × t = k (Note - may not apply to all asthmatic individuals) |

|

|

Data plotted for humans: |

|

|

6 ppm-hour |

0% response |

|

Source: EPA 2002 |

|

|

Moderate Effects: lacrymation, photophobia, corneal opacity, tracheobronchitis, central nervous system depression, nasal passage necrosis |

|

|

Data: insufficient |

|

|

Dose-duration relationship: Cn × t = k (Note—might not apply to all asthmatic individuals) |

|

|

Source: EPA 2002 |

|

|

Severe Effects—cerebral and pulmonary edema to respiratory arrest to unconsciousness to death |

|

|

Data (rat) from MacEwen and Vernot 1972: |

|

|

635 ppm- hour |

10% response |

|

712 ppm- hour |

50% response |

|

800 ppm- hour |

90% response |

|

Mode of toxic action: pulmonary and cerebral edema |

|

|

Allometric scaling: 1:1 for rat:human |

|

|

Uncertainty factors: none |

|

|

Data plotted for humans: |

|

|

635 ppm-hour |

10% response |

|

712 ppm-hour |

50% response |

|

800 ppm-hour |

90% response |

|

Source: EPA 2002 |

|

|

Mode of Action: inhibition of electron transport in tissues with high oxygen demand |

|

|

Dose-duration relationship: varies with types of responses |

|

|

Delayed sequellae: none known or anticipated |

|

|

For comparison: |

AEGL-1 = 0.51 ppm-hour; 0.33 ppm-8 hour AEGL-2 = 27 ppm-hour; 17 ppm-8 hour AEGL-3 = 50 ppm-hour; 31 ppm-8 hour |

|

Propylene Glycol Dinitrate |

|

|

Mild Effects—headache |

|

|

NOAEL (human) = 0.03 ppm for 8 hour |

|

|

Data (human) from Stewart et al. 1974: |

|

|

0.1 ppm-hour |

25% response |

|

0.2 ppm-hour |

50% response |

|

0.4 ppm-hour |

75% response |

|

Mode of toxic action: reactive metabolite produces vasodilation of cerebral vessels; decreased blood pressure |

|

|

Allometric scaling: not applicable |

|

|

Uncertainty factors: none |

|

|

Data plotted for humans: |

|

|

0.1 ppm-hour |

25% response |

|

0.2 ppm-hour |

50% response |

|

0.4 ppm-hour |

75% response |

|

Source: NRC 2002 |

|

|

Moderate Effects—severe headache, slight loss of equilibrium |

|

|

Data (human) from Stewart et al. 1974 |

|

|

0.5 ppm-hour |

25% response (estimated) |

|

1.0 ppm-hour |

50% response |

|

2.0 ppm-hour |

75% response (estimated) |

|

Mode of toxic action: reactive metabolite producing vasodilation of cerebral vessels; decrease in blood pressure |

|

|

Allometric scaling: not applicable |

|

|

Uncertainty factors: none |

|

|

Data plotted for humans: |

|

|

0.5 ppm-hour |

25% response |

|

1.0 ppm-hour |

50% response |

|

2.0 ppm-hour |

75% response |

|

Source: NRC 2002 |

|

|

Severe Effects—vomiting, central nervous system depression, semi-consciousness, clonic convulsions, mortality |

|

|

Data (monkey) from Jones et al. 1972: |

|

|

33 ppm-hour |

25% response (estimated) |

|

70 ppm-hour |

50% response (estimated) |

|

140 ppm-hour |

75% response |

|

280 ppm-hour |

100% response (estimated) |

|

Propylene Glycol Dinitrate |

|

|

Mode of toxic action: reactive metabolite producing decreased systolic pressure; increased diastolic pressure; myocardial eschimia; increased MetHb |

|

|

Allometric scaling: (body weight)−0.75 |

|

|

Uncertainty factors: none |

|

|

Data plotted for humans: |

|

|

60 ppm-hour |

25% response |

|

119 ppm-hour |

50% response |

|

238 ppm-hour |

75% response |

|

Source: NRC 2002 |

|

|

Mode of Action: cardiovascular toxicity and central nervous system depression |

|

|

Dose-duration relationship: linear, C1 × t = k; for severe, long-duration extrapolation C3 × t = k |

|

|

Delayed sequellae: none identified |

|

|

For comparison: |

AEGL-1 = 0.17 ppm-hour; 0.03 ppm-8 hour AEGL-2 = 1.0 ppm-hour; 0.13 ppm-8 hour AEGL-3 = 13 ppm-hour; 5.3 ppm-8 hour |

|

Sarin (GB) |

|

|

Mild Effects—miosis, rhinorrhea |

|

|

NOAEL (human) 0.016 mg/m3 for 20 min |

|

|

Data (human) from NRC 2003: |

|

|

0.32 mg-min/m3 |

0% response |

|

? mg-min/m3 |

25% response |

|

4 mg-min/m3 |

50% response (ECT50) |

|

? mg-min/m3 |

75% response |

|

Mode of toxic action: local |

|

|

Allometric scaling: not applicable |

|

|

Uncertainty factors: none |

|

|

Data plotted for humans: |

|

|

0.32 mg-min/m3 |

0% response |

|

4 mg-min/m3 |

50% response |

|

Moderate Effects—insufficient data |

|

|

Severe Effects—acetylcholinesterase inhibition to convulsions to mortality |

|

|

Data (monkey) from NRC 2003: |

|

|

1 mg-hour/m3 |

1% response (estimated from rat data) |

|

? mg-hour/m3 |

25% response |

|

27-150 mg-hour/m3 |

50% response |

|

? mg-min/m3 |

75% response |

|

Mode of toxic action: stable metabolite leading to acetylcholinesterase inhibition |

|

|

Allometric scaling: 1:1 for monkey:human |

|

|

Uncertainty factors: none |

|

|

Data plotted for humans: |

|

|

1 mg-hour/m3 |

1% response |

|

90 mg-hour/m3 |

50% response |

|

Mode of Action: inhibition of acetylcholinesterase leading to convulsions and then to death |

|

|

Dose-duration relationship: linear, C2 × t = k (?) |

|

|

Delayed sequellae: delayed neuropathy |

|

|

For comparison: |

AEGL-1 = 0.0028 mg-hour/m3 AEGL-2 = 0.035 mg-hour/m3 AEGL-3 = 0.13 mg-hour/m3 |

REFERENCES

Bodansky, O. 1951. Methemoglobinemia and methemoglobin-producing compounds. Pharmacol. Rev. 3:144-196.

Clewell, H., III., M.E. Andersen, and H.A. Barton. 2002. A consistent approach for the application of pharmacokinetic modeling in cancer and noncancer risk assessment. Environ. Health Perspect. 110(1):85-93.

E.I. duPont de Nemours Company. 1981. Inhalation Toxicity of Common Combustion Gases. Report No. 238-81. Haskell Laboratory, Newark, DE.

El Ghawabi, S.H., M.A. Gaafar, A.A. El-Saharti, S.H. Ahmed, K.K. Malash, and R. Fares. 1975. Chronic cyanide exposure: A clinical, radioisotope, and laboratory study. Br. J. Ind. Med. 32(3):215-219.

EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). 1994. Methods for Derivation of Inhalation Reference Concentrations and Application of Inhalation Dosimetry. EPA/600/8-90/066F. Environmental Criteria and Assessment Office, Office of Health and Environmental Assessment, Office of Research and Development, .S. Environmental Protection Agency, Research Triangle Park, NC. October 1994.

EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). 2002. Hydrogen Sulfide, Interim Acute Exposure Guideline Levels (AEGLs). Interim 4 Technical Support Document: 11/2002. Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Jones, R.A., J.A. Strickland, and J. Siegel. 1972. Toxicity of propylene glycol 1,2-dinitrate in experimental animals. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 22(1):128-137.

Kiese, M. 1974. Methemoglobinemia: A Comprehensive Treatise; Causes, Consequences, and Correction of Increased Contents of Ferrihemoglobin in Blood. Cleveland, OH: CBC Press.

Kim, Y.C., and G.P. Carlson. 1986. The effect of an unusual workshift on chemical toxicity. II. Studies on the exposure of rats to aniline. Fundam. Appl. Toxicol. 7(1):144-152.

MacEwen, J.D., and E.H. Vernot. 1972. Pp. 66-69 in Toxic Hazards Research Unit Annual Report: 1972. Report No. ARML-TR-72-62. NTIS AD755-358. Aerospace Medical Research Laboratory, Air Force Systems Command, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, OH.

NIOSH (National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health). 1976. Occupational Exposure to Hydrogen Cyanide and Cyanide Salts (NaCN, KCN, and Ca(CN)2): Criteria for a Recommended Standard. DHEW (NIOSH) 77-108. Cincinnati: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Center for Disease Control, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

NRC (National Research Council). 2000. Acute Exposure Guideline Levels for Selected Airborne Chemicals, Vol. 1. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

NRC (National Research Council). 2001. Standard Operating Procedures for Developing Acute Exposure Guideline Levels for Hazardous Chemicals. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

NRC (National Research Council). 2002. Acute Exposure Guideline Levels for Selected Airborne Chemicals, Vol. 2. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NRC (National Research Council). 2003. Acute Exposure Guideline Levels for Selected Airborne Chemicals, Vol. 3. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Purser, D.A. 1984. A bioassay model for testing the incapacitating effects of exposure to combustion product atmospheres using cynomolgus monkeys. J. Fire Sci. 2:20-36.

Seger, D.L. 1992. Methemoglobin-forming chemicals. Pp. 800-806 in Hazardous Materials Toxicology: Clinical Principles of Environmental Health, J.B. Sullivan and G.R. Krieger, eds. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins.

Sim, V.M., and R.E. Pattle. 1957. Effect of possible smog irritants on human subjects. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 165(15):1908-1913.

Smyth, H.F., Jr. 1956. Hygienic standards for daily inhalation. Am. Ind. Hyg. Assoc. Q 17(2):129-185.

Stephens, E.R., E.F. Darley, O.C. Taylor, and W.E. Scott. 1961. Photochemical reaction products in air pollution. J. Air Pollut. 4:79-100.

Stewart, R.D., J.E. Peterson, P.E. Newton, C.L. Hake, M.J. Hosko, A.J. Lebrun, and G.M. Lawton, 1974. Experimental human exposure to propylene glycol dinitrate. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 30(3):377-395.

USACHPPM (U.S. Army Center for Health Promotion and Preventive Medicine). 2002a. Chemical Exposure Guidelines for Deployed Military Personnel. Technical Guide 230. U.S. Army Center for Health Promotion and Preventive Medicine. January 2002. [Online]. Available: http://chppm-www.apgea.army.mil/deployment/ [accessed November 25, 2003]

USACHPPM (U.S. Army Center for Health Promotion and Preventive Medicine). 2002b. Chemical Exposure Guidelines for Deployed Military Personnel. A Companion Document to USACHPPM Technical Guide (TG) 230 Chemical Exposure Guidelines for Deployed Military Personnel. Reference Document (RD) 230. U.S. Army Center for Health Promotion and Preventive Medicine January 2002. [Online]. Available: http://chppm-www.apgea.army.mil/deployment/ [accessed November 25, 2003]

Vanhoorne, M., A. de Rouck, and D. de Bacquer. 1995. Epidemiological study of eye irritation by hydrogen sulfide and/or carbon disulphide exposure in viscose rayon workers. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 39(3):307-315.

Weeks, M.H., G.C. Maxey, M.E. Sicks, and E.A. Greene. 1963. Vapor toxicity of UDMH in rats and dogs from short exposures. Am. Ind. Hyg. Assoc. J. 24:137-143.

WHO (World Health Organization). 1981. Hydrogen Sulfide. Environmental Health Criteria 19. Geneva: World Health Organization.