Applications of an Analytic Framework on Using Public Opinion Data for Solving Intelligence Problems: Proceedings of a Workshop (2022)

Chapter: 1 Public Opinion Data and the Analytic Framework

1

Public Opinion Data and the Analytic Framework

HISTORY AND CURRENT STATUS OF PUBLIC OPINION RESEARCH IN THE INTELLIGENCE COMMUNITY

Regina Faranda (director of the Office of Opinion Research at the U.S. Department of State) explained that public opinion has played an important role in the intelligence analysis that supports U.S. policy since 1948. The Office of Opinion Research has a mandate to ensure that the U.S. government is aware of how the global public thinks and how that affects U.S. interests. To fulfill this mandate, she continued, it is imperative that intelligence analysts keep pace with current trends in public opinion research methods.

Faranda shared an example of the intelligence community’s (IC’s) effective use of public opinion research in the identification of macrotrends, which could help predict when conditions are most suitable for protests. Relevant data collection could include public views of the economy, politics, food insecurity, local leaders, and corruption. Although these factors alone might not provoke a protest, public opinion research offers insight into individual drivers of protest alongside regional context to create better predictions. Social science research is most useful when understood within a regional or national context. She mentioned that protest has become a normalized form of expression in certain countries; for example, in some African nations, people who have experienced bribery are more likely to support anticorruption protests. Public opinion research can also help identify redlines for the public in the form of constitutional revision, egregious corruption, or attempts to circumvent term limits.

CHALLENGES FOR INTELLIGENCE ANALYSTS IN A CONTINUALLY EVOLVING LANDSCAPE

Faranda described the rapidly changing landscape within which intelligence analysts work; for example, the evolution of machine learning and the tools for data modeling, the increased use of social media, and the broad access to quick and inexpensive communication have created an inflection point for public opinion research. She emphasized that the significance of public opinion analysis is unlikely to diminish, and the use of empirical research is likely to increase. However, as public opinion research becomes exponentially more sophisticated in the United States, the quality of opinion research abroad varies widely and often lags behind that of the United States, creating challenges for drawing on the findings from international survey research to inform U.S. foreign policy. Further complicating this issue is the fact that policy readers have to be able to understand increasingly technical arguments. She asserted that the IC has a responsibility to make these arguments more relatable for its clients.

A representative from the IC championed the Analytic Framework’s role in helping intelligence analysts leverage the most recent advances in social and behavioral sciences to complete their jobs, which vary from day to day and between individuals. She highlighted several differences between the work of analysts in the IC and experts in academia. Intelligence analysts

- diagnose a situation as it unfolds and look for the implications;

- react to events where they occur instead of developing their own lines of inquiry;

- generalize from findings that might not relate to the problem at hand and operate under significant ambiguity;

- have customers who are generalists, not experts, who are responsible for making decisions about difficult real-world problems; and

- assess the meaning of complex developments under significant time pressure and present their findings concisely to busy policy makers.

A representative from the IC remarked that the past decade of protests around the world has solidified for intelligence analysts and policy makers the importance of understanding public mood. However, with the widespread use of polling and the criticism of polling methods around the world (e.g., in the context of U.S. elections) as well as the fact that, as Faranda mentioned, international polling methods often lag (or are perceived to lag) behind those of the United States, she noted that it can be difficult for intelligence analysts to communicate assessments about foreign publics to U.S. policy makers. Analysts make judgments and present their best insights in short time frames. Furthermore, products from the

IC generally reflect the coordinated views of several stakeholders instead of a single author. Highly skilled analysts often reach varied conclusions about the same phenomenon owing to the differences in their quantitative, qualitative, and statistical training and to constraints on data availability, data access, and time. The IC is challenged to ensure that it rigorously synthesizes and clearly communicates these insights across methodological divides. She asserted that the Analytic Framework could help intelligence analysts select and apply the best methods to derive judgments; synthesize perspectives; and provide concise, persuasive, and timely insights about what they think, what they know, and how they know it to diverse customers who lack the time and expertise to discuss the underlying analytical methodology.

OVERVIEW OF THE ANALYTIC FRAMEWORK

Elizabeth Zechmeister (co-lead expert contributor for the Analytic Framework, and Cornelius Vanderbilt Professor of Political Science and director of the Latin American Public Opinion Project at Vanderbilt University) elaborated on the heterogeneity in (1) intelligence analysts’ prior training and experience with survey methodology; (2) the types of questions being explored by intelligence analysts and the ways that survey data intersect with them; and (3) the types of data that are available or could be generated to make an assessment. Recognition of this heterogeneity played an important role in the creation of the multilayered Analytic Framework (NASEM, 2022), which was generated with the contributions of an advisory panel of 12 experts in survey and social science research methods; 5 subject-matter experts who authored four commissioned papers; a technical writer who wrote the synthesis; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine staff; and liaisons from the IC. Because public opinion data are a critical input into intelligence analysts’ assessments of attitudes in foreign populations, she continued, the following question guided the work of the expert contributors to and authors of the Analytic Framework: how can the IC analyze, make inferences from, and present public opinion data in ways that align with best practices, while acknowledging that these data are not always perfect or complete?

Zechmeister emphasized that the Analytic Framework is not designed to offer direct answers to research questions or a set of preset instructions for every situation. Instead, it empowers intelligence analysts to conduct systematic evaluations guided by best practices. In essence, the analyst has three tasks: make an estimate about public attitudes and/or opinions; use available techniques to make that estimate as precise as possible; and make an assessment about the degree of certainty or uncertainty of that estimate. She remarked that the Analytic Framework introduces intelligence analysts

to the appropriate ways to use and evaluate public opinion data, with careful attention to the design and interpretation of attitudinal data, the adjustment of inferences to communicate likely bias and uncertainty, the use of alternative data sources when appropriate, and the combination of insights from different data sources (i.e., triangulation).

Structure of the Analytic Framework

Zechmeister and Charles Lau (co-lead expert contributor for the Analytic Framework and director of the International Survey Research Program at RTI International) outlined the structure of the Analytic Framework, which consists of a foundational layer, a synthesis layer, and a graphic layer.

Foundational Layer

Zechmeister noted that the foundational layer is targeted toward intelligence analysts with prior training and experience in survey methodology. It includes four white papers (summarized below), which contain detailed discussions of and citations to relevant academic work.

“Drawing Inferences from Public Opinion Surveys: Insights for Intelligence Reports,” by René Bautista (associate director of the Methodology and Quantitative Social Sciences Department at NORC, University of Chicago), provides an overview of how survey methodologists evaluate data quality using two criteria: credibility and soundness. Credibility can be assessed by collecting contextual information about the survey’s purpose, authenticity, and sponsorship, as well as the reputation of the survey firm, through the documentation that accompanies the data. A lack of available documentation indicates a lower level of credibility. Soundness considers the survey design features that can influence bias and error; for example, the nature of the sample (probability versus nonprobability); whether the sample represents the population of interest, sample coverage, item measurement (i.e., what the question was and how it was asked); response rates; and weights. Zechmeister pointed out that a higher survey participation rate is not always indicative of high quality or representativeness, and that if nonresponse to a particular question is high, respondents could be censoring answers to a sensitive question. Thus, the analyst could consider the following question: Is there evidence that participation in the survey is skewed in a way that the survey weights cannot overcome to make inferences about the population of interest? Bautista’s paper presents a rating system that intelligence analysts can use to help assess about the quality of a dataset and to explain their level of confidence in the result to the customer: (1) “credible and sound”; (2) “partially credible, partially sound”; or (3) “not credible, not sound.”

“Alternatives to Probability-based Surveys Representative of the General Population for Measuring Attitudes,” by Ashley Amaya (senior survey methodologist at Pew Research Center), offers guidance on how to select and use nonprobability-based approaches to gather insight on public opinion. Zechmeister commented that although pure probability-based survey methods are the “gold standard,” they are not always available or required to address particular research questions. Amaya’s paper reveals that the selection of alternative methods depends on the question (e.g., assessment of the general population or a subgroup) and the priorities (e.g., timeliness, single-point precision, or across-time changes) of interest, and that nonprobability alternative sources can be evaluated for their strengths and weaknesses with the use of a 2 × 2 matrix: (1) designed data, which emerge from a systematic attempt to address a particular question, versus organic data, which emerge for another purpose but might still provide insight into public opinion; and (2) primary data (i.e., collected by the researcher) versus secondary data (i.e., collected by others). Alternative approaches include complex sample surveys, nonprobability surveys (e.g., an online survey for which participants are invited from a firm-maintained panel, often based on quotas for age, wealth, location, and gender), qualitative research, and social media data. Zechmeister mentioned that although online surveys might have coverage issues (e.g., lack of Internet access in certain countries), the data from those surveys could still be useful. The same principle applies to social media data, which are often noisy and biased but could help to uncover the context in which many in a population are functioning. Amaya’s paper also highlights ethical considerations for alternatives to pure probability-based general population surveys.

“Ascertaining True Attitudes in Survey Research,” by Kanisha Bond (assistant professor of political science at Binghamton University, State University of New York), defines “true attitudes” as “predispositions that are honestly held, and reflective of the respondent’s sense of the real state of the world; true responses to attitude inquiries…are honestly communicated descriptions of those predispositions” (NASEM, 2022). Attitudes are difficult to measure because they are multidimensional; for example, survey results can include implicit/explicit attitudes, nonattitudes, strategic responses that mask true attitudes, partial attitudes, and nonresponses. Bond’s paper emphasizes that the ethical and technical issues of measuring attitude are intertwined—ethics can affect the quality as well as the technical ability of a survey to reveal true attitudes (e.g., if participants experience harm during the data collection or fear retribution for their responses, they are unlikely to provide high-quality responses). Lau observed that unethical surveys can also lead intelligence analysts to make inaccurate recommendations to policy makers. Bond’s paper describes eight challenges that arise when trying to measure true attitudes, especially in locations with high conflict:

- Purposeful misrepresentation (a researcher deceives a respondent);

- Power dynamics (respondents either answer the survey in favorable ways to please the sponsor or contribute false information to sabotage the survey);

- Fragile or volatile contexts (being in a conflict area can alter attitudes);

- Potential for direct harm (sensitive survey questions can cause trauma or create security risks for respondents);

- Sensitive topics (respondents might underreport “socially undesirable” attitudes);

- Time (people’s attitudes change over time and in different environments);

- Sampling and exposure (populations can be over-surveyed); and

- Questionnaire type, question forms, and intercultural literacy.

Her paper assists intelligence analysts in identifying these challenges, connecting that understanding to the interpretation of data, and recognizing how policy recommendations could be affected. Understanding the data generation process helps an analyst assign bias to items and avoid presenting an inaccurate policy recommendation.

“Integrating Data Across Sources,” by Josh Pasek (associate professor of communication and media and political science, faculty associate in the Center for Political Studies, and core faculty for the Michigan Institute for Data Science at the University of Michigan) and Sunghee Lee (research associate professor at the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan), offers guidance to intelligence analysts about how to apply multiple datasets to answer a question. Lau explained that combining datasets helps to better understand the flaws of those datasets and employ methods to correct them, and to enhance the quality of the policy recommendation. Pasek and Lee’s paper defines data integration as “the process of taking multiple diverse streams of information and finding ways to use them jointly to make conclusions, reconcile their differences, and/or determine where they provide complementary or conflicting understandings” (NASEM, 2022). The paper emphasizes that before integrating data, intelligence analysts should understand the nature of the data and harmonize those data to confirm that integration and comparison are possible, using processes such as data cleaning, linking sample data with the population, addressing data missingness, generating a composite measure, and validating. Once the data have been harmonized and then combined, several techniques are available for data analysis and integration (e.g., ensemble methods).

Synthesis Layer

The second layer of the Analytic Framework, the synthesis layer, “Using Public Opinion Research to Answer an Intelligence Question,” written by Rona Briere (independent contractor), presents the core components of the Analytic Framework in a way that is more accessible to intelligence analysts who do not have extensive training in or experience with survey methodology. Zechmeister described this layer as an “orientation to the fundamental ideas and best practices of public opinion research.”

Graphic Layer

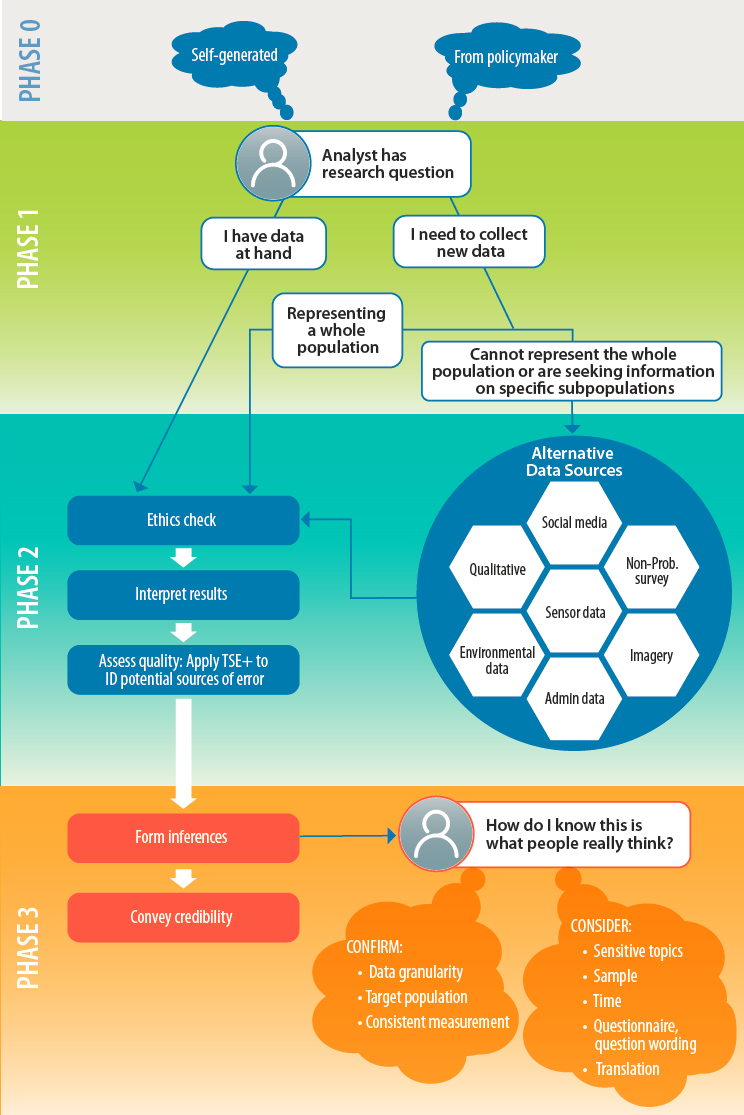

Zechmeister explained that the top layer of the Analytic Framework is a graphic that presents a decision tree with four iterative phases, which could be useful to guide the work on a time-sensitive task of an intelligence analyst who has either attended this workshop or has read the synthesis layer. During Phase 0, the analyst generates or is assigned a research question. In Phase 1, the analyst collects existing data and/or decides to collect new data, based on available resources, the question, and the time line. She emphasized how important it is for the analyst to consider whether the existing data represent the population of interest—the foundational layer of the Analytic Framework includes guidance on the use of alternative sources to strengthen inferences. Phase 2 provides an opportunity to analyze the data by conducting an ethics check, interpreting the results that can be generated with the data, and evaluating the quality of the data. Phase 3 serves to inform the inferences that the analyst has drawn and to build confidence in those inferences. The analyst iterates through this process, with consideration for aspects that could confirm, qualify, or contextualize the inferences (e.g., whether the population might self-censor on a certain type of question) (see Figure 1-1).

Responses to the Analytic Framework

A representative from the IC reiterated the challenges of bridging the gap between the IC and academia. However, the Analytic Framework helps shift the IC’s focus away from answering narrow questions toward thinking more broadly and with more structure. She underscored a gap in the literature included in the Analytic Framework, which is a lack of information on the relationship between attitudes and behavior. She encouraged the experts to continue to share innovative methods with the IC as well as areas of uncertainty for which they have not yet identified the best route to address difficult questions.

Bautista expressed his hope that the Analytic Framework will expose analysts to strategies that they might not encounter in academic textbooks.

He emphasized the value of contextual elements (highlighted in his paper), which are critical in the overall assessment of any survey. Amaya commented that in addition to discussing nonprobability-based approaches, her paper describes several probability-based approaches for surveys with a purpose other than to measure the general population, and includes techniques that illuminate the best option. Her paper also presents an overview of the advantages and disadvantages of each alternative approach. She urged intelligence analysts to reflect on these strengths and weaknesses alongside the evaluative measures presented in Bautista’s paper. It is critical to understand priorities before choosing a dataset. Because no dataset is perfect, she stressed that the best choice is the one that works for the analyst and their purpose. Pasek pointed out that combining datasets can lead to several possible outcomes and answers to a question, which can be both inspiring and discouraging. Although combining data will always be messy, he continued, identifying consistencies will provide strong support for inferences.

Bond emphasized that because technical and ethical approaches to understanding attitudes are intertwined, they have to be carefully balanced (in addition to weighing issues of robustness and precision in estimation). The question of whether a systematic ethical irregularity exists affects how well intelligence analysts can use data to infer what people think, and she indicated that further conversation about that issue would be beneficial. Faranda asserted that it is crucial to be attentive to the “people part of public opinion”—for example, questions have to be relevant and phrased in a way that people can access. Quoting anthropologist Cora Du Bois, Faranda said, “It behooves us to . . . use our new powers with judicious and constructive wisdom.” Courtney Kennedy (expert contributor for the Analytic Framework and director of survey research at Pew Research Center) championed Faranda’s advice never to lose focus of the people in the population of interest, especially as online data collection increases and more countries are surveyed online. She revealed that conducting online surveys makes it easier to lose touch with how people are reacting to questions, and suggested the development of best practices for how to test and ensure that online measurements are sound and resonate with the population.

ETHICAL AND CULTURAL CONSIDERATIONS IN THE COLLECTION AND USE OF PUBLIC OPINION DATA

Ethical Considerations

Zachariah Mampilly (expert contributor for the Analytic Framework and Marxe Endowed Chair of International Affairs at the Marxe School

of Public and International Affairs, City University of New York) echoed Bond’s assertion that the ethical and technical facets of public opinion research are intertwined: no inherent tradeoff between them exists, especially in the case of foreign policy. Unethical research practices undermine the quality of the research and could thus undermine foreign policy objectives. He encouraged workshop participants to read Bond’s paper in the Analytic Framework as well as additional literature on the ethical issues that arise specifically in political violence–affected contexts (see ARC, n.d.; Arjona, Mampilly, and Pearlman, 2019).

Mampilly cited the Tuskegee experiment as an example of the long afterlife of unethical research (e.g., reluctance toward COVID-19 vaccinations among certain communities) and the need to be concerned about the victims of such unethical experimentation. Because the U.S. government distinguishes itself from its enemies in terms of its concern with ethical practices, he continued, ethics are not only a moral imperative but also an essential component of the identity of the United States.

Reflecting on the connection between academia and the IC, Mampilly remarked that their relationship is the closest it has been for decades. For example, after Vietnam, suspicions arose owing to the perception that academic researchers were being turned into “tools of the U.S. government.” This perception began to change after 9/11, when cooperation between academia and the IC improved significantly. The level of collaboration between the two communities has continued to fluctuate over the course of administrations. Now, the nature of the relationship between academia and the IC is being reevaluated, and he described an opportunity for enhanced inquiry into ethical research between the two communities.

Bond explained that both challenges and opportunities arise in understanding true attitudes of a population as a result of the ethical and technical considerations for survey research. She also described the interconnected nature of those who conduct research and those who participate in research and noted that ensuring the security and safety of all individuals involved in survey research is critical. Because the “human core” (i.e., human ideals, beliefs, preferences, and political behaviors) is paramount, she continued, research should be conducted ethically and rigorously.

Bond commented that researchers should be attuned to systematic ethical irregularities. She stressed that the purpose of her paper is not to “make calls” for others about what constitutes an appropriate research process; instead, it provides general guidance about acceptable research practice and acceptable uses of human data. Various professional associations (e.g., the American Association for Public Opinion Research [AAPOR] and the American Political Science Association) have developed codes of ethics, but those do not replace the personal ethics of any intelligence analyst who is engaged with the research; the analyst plays just as important a role

as the research subject in terms of ethical considerations. The more volatile the environment, she continued, the more opportunity for ethical irregularities to arise; the paper explores how to determine what respondents think based on their location in their complex security relationships. The concept of a “true attitude” emerges when asking whether something is “real” to the respondent; “Is what you are telling me what you believe?” is a complicated, yet universally human question. She suggested supporting individuals in their thoughts about and challenges in doing ethical work as well as raising awareness of context and the integration of that context into the work.

Cultural Considerations

Michele Gelfand (expert contributor for the Analytic Framework; John H. Scully Professor in Cross-Cultural Management and professor of organizational behavior, Stanford Graduate School of Business; and professor of psychology [by courtesy], School of Humanities and Sciences, Stanford University) explained that the realities that surround humans, like culture, tend to be taken for granted or misunderstood; people often do not realize how they are part of a culture or how they have been affected by cultural values and norms until they experience another culture. She emphasized that culture affects each stage of the research process.

Gelfand asserted that cross-cultural research poses several unique methodological issues. Research itself is a cultural process, and the result could be the introduction of several “extraneous variables” unrelated to the question of interest. Each of those variables can pose “rival hypotheses” for any differences identified across cultures; if these variables are not addressed, conclusions could be misleading. These rival hypotheses can be represented as a regression problem, Y′ = τy + Σki, + ε, where ki is any systematic variation other than τ that affects Y′ (the prediction) (see Malpass, 1977). In other words, the sum of ki’s is the bias that affects the prediction. In unicultural research, she continued, researchers are implicitly aware of possible cultural ki’s that can bias results; within cross-cultural research, however, unknown cultural ki’s might not be measured or controlled, thus affecting interventions.

Gelfand emphasized that although constructs and measurements should be representative of the culture of interest, people often try unsuccessfully to transfer constructs and measurement developed in the United States into another cultural context. She explained that this use of “imposed etics”1 is similar to comparing apples to oranges. She provided an example research question relating to whether organizational embeddedness, a U.S. construct,

___________________

1 Merriam Webster defines “etic” as “of, relating to, or involving analysis of cultural phenomena from the perspective of one who does not participate in the culture being studied.”

had a role in radical organizations in terms of predicting attitudes toward radicalization. Using techniques such as confirmatory factor analysis, the first step was to assess whether the construct represented the phenomenon in this particular context. She underscored the importance of equivalence of measurement—that is, whether items are relevant, similar across cultures, contaminated, or deficient. Because a technique such as confirmatory factor analysis could not address issues of deficiency in particular, it was necessary to conduct interviews and focus groups in the country of interest to better understand constructs and add items more relevant in that country’s context. She suggested a “combined etic-emic2 strategy” (Berry, 1969), in which a researcher begins with a particular cultural perspective; collects culture-specific (i.e., “emic”) information from other countries; and incorporates this information to create a new “etic” so that the final construct is more representative across cultures. A relevant example is work on the U.S. construct of organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs) in China (Farh et al., 1997). The researchers discovered that certain dimensions of OCBs were relevant in both cultures; others were relevant in the United States but not relevant in China; and still others were relevant in China but not relevant in the United States. She cautioned researchers about their constructs; what has developed to scale in the United States could be irrelevant, deficient, or contaminated in other contexts.

Gelfand asserted that methods for cross-cultural research should be appropriate, be replicable, have ample depth, and be ethically acceptable (see Gelfand et al., 2002; Hui and Triandis, 1985). She pointed out that triangulating multiple methods in cross-cultural research could enhance confidence in the results. Interviews and focus groups could offer great depth of information and emic perspectives, but problems could arise when cultural ki’s are added, thus misrepresenting attitudes. For instance, although an interviewer might be readily trusted in the United States, this is uncommon in other parts of the world, where more time is spent to develop trust. Furthermore, interviewer characteristics could differentially impact participants, the interview could prompt reactance (e.g., if payment is offered for participation), the format of the interview might be culturally inappropriate (e.g., a female interviewing a male), or the interview could lack standardization. To avoid the influence of cultural ki’s, she suggested developing a structured interview protocol, reviewing the content and structure with local collaborators and being prepared to make changes as needed, using local interviewers with characteristics similar to those of the participants, conducting a pre-interview/focus group to detect problems, and standardizing interviewers. Questionnaires are less expensive than

___________________

2 Merriam Webster defines “emic” as “of, relating to, or involving analysis of cultural phenomena from the perspective of one who participates in the culture being studied.”

other methods and allow for the relatively unobtrusive collection of significant amounts of data; however, differences in respondents’ motivations to answer questions, differences in familiarity with materials, and problems with rating scales and response sets across cultures create challenges. She advised conducting extensive piloting, gathering input from local collaborators, using alternative scale formats, being cautious of using long surveys with complex language, and combining questionnaires with other methods to reveal convergence. Another key consideration in cross-cultural research is language. Although the right choice of language is not always obvious, it is important because it communicates the purpose of the study and can influence the results. She cautioned researchers to take care with accurate translation and backtranslation. Field or laboratory experiments can be useful in addressing causality and understanding implicit attitudes, but they can be obtrusive, lack context, create a differential understanding of the task and the motivation, and include manipulated variables with different strengths. She advocated for researchers to conduct multiple pilots and gather feedback from local collaborators, anticipate changes and revise as appropriate to reflect context, use local experimenters who have similarities to the participants, and use experimentation alongside other methods. Content analysis is an unobtrusive way to gather accounts of culture from documents. For example, linguistic dictionaries (Choi et al., 2022) can be created to better understand cultural constructs and underlying attitudes, and proverbs can be analyzed to understand how cultures view risk (Weber et al., 1998). She suggested that researchers invite local collaborators to identify appropriate documents, be cautious of noncomparable sources, and create a reliable coding manual in all cultures. Observations are also used in cross-cultural research, providing unobtrusive data and indicators that can be difficult to evaluate with other methods. She encouraged researchers to confirm that the situation sampling is appropriate, that participants in field experiments are standardized, and that ethics are considered within a local context. Ecological and historical databases provide a rich source of data to connect cultural dimensions but can be unreliable, she continued, and computational methods can aid in the study of cultural dynamics and the study of theories that are difficult to test in the field. She advocated for clear and carefully justified assumptions, understanding of the generalizability of results, and replication with other methods. Because cultural assumptions can affect choices made in the models, however, she reiterated the importance of working with local collaborators. Overarching concerns about analyzing data relate to cultural response sets, structural equivalence, and aggregation issues.

In summary, Gelfand reiterated that cross-cultural research is far more complicated than unicultural research, owing to the emphasis on the appropriateness, reliability, depth, and ethics of each method amidst a

backdrop of cultural concerns. She reaffirmed the value of using pilots for tasks and instructions, being flexible to adjust, measuring and controlling rival hypotheses, using multiple complementary methods, and partnering with local collaborators. Dedicating attention to these ethical and cultural considerations results in greater confidence in policy recommendations.

Discussion

An intelligence analyst noted that when work has to be completed within 24 hours, an analyst might not have time to reflect on herself or the scenario from an ethical perspective. She wondered how to make space for these important considerations when in “go-mode.” An intelligence analyst highlighted the ethical decision of whether to use certain data to answer a question while in “go-mode”—one that might require telling the policy maker that the answer is unknowable (e.g., it is unethical to justify a policy recommendation based on the results of a push poll), even if that contradicts the culture of the IC and its incentives. Bond suggested developing strategies to think through these issues before a high-pressure situation arises—for example, by creating an ethical code that guides every step of the work whether or not in crisis mode. She emphasized that analysts and researchers alike should always be in “ethical go-mode,” continually protecting themselves and others who are helping to complete the work. She encouraged a more concerted effort to create this detailed guidance ahead of time to avoid having to make judgment calls during high-pressure situations that could incite mistakes, because anyone using data from humans about humans is responsible for their care and the care of the people who provided those data. Mampilly remarked that the Analytic Framework provides an ethics checklist as a starting point for any research that is being evaluated to make policy recommendations. He also urged the IC to foster a “culture of ethics.” He described the immense pressure on junior analysts who want to make both actionable and ethical recommendations—ethics should not be compromised to make actionable recommendations, but a culture shift is required to embrace this mindset. An intelligence analyst explained that experienced intelligence analysts who have completed graduate studies have been introduced to these ethical standards, but new analysts have not had the opportunity to think deeply about ethical considerations and would benefit from additional guidance.

Pasek proposed removing the sole ethical responsibility from the person who is making the decision (similar to the use of research ethics boards in biomedical and behavioral science) so that the motivation for analysis does not overshadow the ethics of the analysis (i.e., give someone else the power to put an “ethics stop” on the work). In this case, however, ethics would still be considered by everyone involved in the process, as it should

be in any investigation that includes human subjects. Bond pointed out the danger in asking people to separate themselves from their responsibility for ethical decisions. She reiterated that every analyst who engages with data from humans about humans has an individual responsibility, equivalent to that of anyone else in the hierarchy; in other words, ethical responsibility extends beyond ethical practice in data collection to ethical use of the data. James Druckman (expert contributor for the Analytic Framework and Payson S. Wild Professor of Political Science at Northwestern University) supported Pasek’s commentary about relying on external entities to make ethical judgments but suggested first considering the motivations of external sources. Thus, while it might be difficult to trust oneself, it could be equally difficult to identify an entity that could be wholly trusted to provide ethical guidance. Bautista referenced the American Statistical Association’s code of ethics, which highlights a practitioner’s responsibilities to science, the public, research subjects, and colleagues. Such an ethical code is then internalized in the work and reflected in the work products. An analyst indicated that implementers also play an important role in the ethical conduct of research. Because some are willing to do dangerous research for profit or because of ideology, he advised caution on behalf of those implementers.

Addressing Mampilly’s earlier discussions about different administrations’ influences on collaboration between academia and the IC, Faranda proposed that this relationship be normalized. When an administration changes, the IC continues to do its best analysis; however, during times of political tension, support from the academic community is even more critical. Mampilly agreed that the IC is not as politicized as the broader society and can work objectively across administrations; however, academics do not always share that mindset. He suggested dedicating time to creating a healthier relationship between the two communities. Michael Hout (expert contributor for the Analytic Framework and professor of sociology at New York University) observed a difference between career employees and political appointees. For example, even when career employees experience political pressure to change how they do their jobs, most do not, perhaps owing to the support of academia and organizations like the National Academies and the Population Association of America. Diana Mutz (expert contributor for the Analytic Framework, and Samuel A. Stouffer Chair in Political Science and Communication and director of the Institute for the Study of Citizens and Politics at the University of Pennsylvania) added that academics who have interacted with the National Science Foundation through various administrations have been told that their cooperation with the IC is valuable. However, she said that it is important for the IC to communicate more broadly its desire to work closely with academia because those external to the government might be unaware.

Faranda reflected on the current situation in Ukraine, where analysts have asked whether it is ethical to conduct survey research. Her office uses the AAPOR code as a guide, which prioritizes “do no harm.” Important questions to consider include the following: are people being put at risk or being retraumatized? Or, are people being given an opportunity to have their voices heard? She underscored that a checklist of potential harms could serve as an initial guide for decision making. D. Sunshine Hillygus (expert contributor for the Analytic Framework, and professor of political science and professor of public policy [by courtesy] at Duke University) commented that ethics and the potential harm of research are difficult to conceptualize in the abstract. Some researchers are unaware of the type of harm that survey research can cause—for example, via associated disclosure risk. While that might not be an issue if data are not made publicly available, other issues arise when data are collected without explicit consent or are used in ethically unsound ways. Although the AAPOR checklist is suitable to assess transparency and quality, she posited that it could have limited use to assess ethical issues. She wondered how best to think about the questions researchers could be asking; for example, her checklist as a university institutional review board member is likely less comprehensive than what would be useful for an intelligence analyst. Bond explained that an analyst can ask herself certain questions to target higher-level ethical concerns: Were the data provided voluntarily? Where are the respondents located in terms of their power to protect themselves? Where is the survey conductor located? For example, even with a phone survey, a phone line could be re-identified and people could listen in, which could cause harm to individuals. It is critical to think about these issues ahead of time and evaluate their context within broader cultural concerns. She cautioned that relying only on an ethics “checklist” is insufficient, as ethical considerations are far more complicated.

Gelfand said that these issues relate to “ethical climate,” not “individual ethical style,” and a change would need to be implemented over the long term. She advocated for the development of a set of practices and rewards to improve the “ethical climate” and to make ethics a top priority in the IC. She emphasized that this shift requires both training and thought experiments with feedback as well as local collaboration to help intelligence analysts make the most ethical decisions.