Increasing the Utility of Wastewater-based Disease Surveillance for Public Health Action: A Phase 2 Report (2024)

Chapter: 3 Analytical Methods and Quality Control for Endemic Pathogens

3

Analytical Methods and Quality Control for Endemic Pathogens

Appropriate analytical methods and quality control are central to producing reliable and interpretable data for national wastewater-based infectious disease surveillance. In this chapter, the committee discusses specific characteristics of analytical methods and associated quality criteria appropriate to a robust wastewater surveillance program for endemic pathogens and discusses technical constraints and opportunities. This chapter is focused on known endemic targets and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methods that are likely to be used in the near term in the National Wastewater Surveillance System (NWSS) for endemic pathogen monitoring. Methods for emerging and unknown organisms are discussed in Chapter 6. The chapter begins with an overview of the state of analytical capacity for wastewater-based infectious disease surveillance, including sample processing, concentration, analysis, and storage, and then discusses opportunities for improving quality control. Research and development needs are also identified.

STATE OF ANALYTICAL CAPACITY

Current wastewater-based infectious disease surveillance efforts are hindered by significant data comparability issues. Myriad methods are employed to concentrate, detect, and quantify endemic pathogens, and the lack of consistency has led to a troubling amount of incomparable and sometimes unreliable data, complicating the interpretation and communication of findings (Ciannella et al., 2023). Data reliability was particularly a concern early in the pandemic as methods employed were evolving or

inadequately validated, and some reliability issues remain today. Statistical analysis of the entire NWSS data set will prove difficult given these issues (Parkins et al., 2023).

As the NWSS program works to address these issues, additional targets are also being added, necessitating an understanding of the analytical specificity and sensitivity for the new targets. If the intent is to fit all targets into a single sample processing and analysis framework, which target and/or use case will determine the framework used? Different use cases and public health actions may require different workflows and pre-analytical sample processing strategies to generate actionable public health data. For instance, concentration, purification, and extraction methods optimized for viruses may result in suboptimal performance for bacterial or yeast targets. This may have implications in the sensitivity of the methods and whether they are “fit for purpose” for their intended use case. Differences in molecular detection methods may vary from target to target, particularly between RNA and DNA targets, but the variation in performance is unlikely in most cases to be significant relative to variability in concentration, purification, and extraction methods once optimized for a target (Wade et al., 2022).

Concentration, Extraction, and Purification Methods

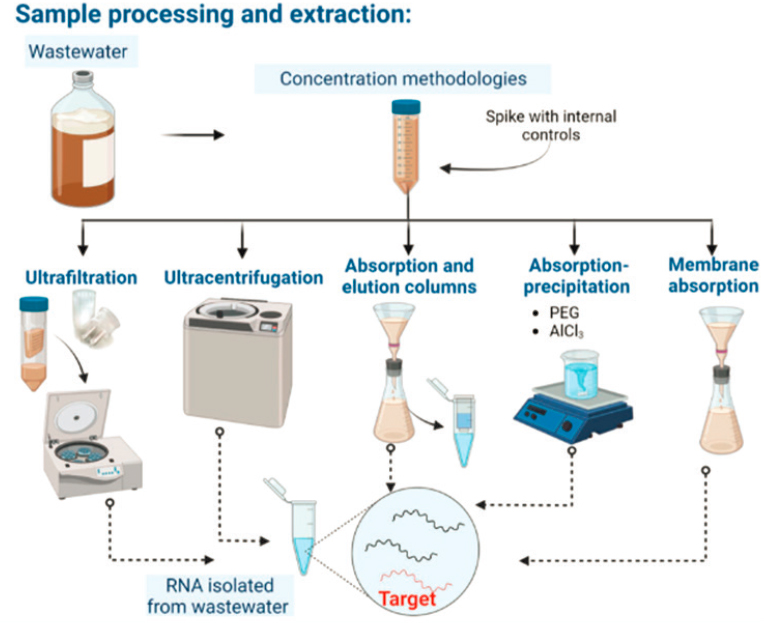

Understanding performance in the stages of concentration, extraction, and purification are pivotal in the pre-analytical sample processing for wastewater surveillance. A variety of different methods have been evaluated for either liquid or solid samples, each with its strengths and limitations (see Figure 3-1) (Ciannella et al., 2023; Pecson et al 2021; Philo et al., 2021; Chik et al., 2021; Rusinol et al., 2020). No current approach has been identified as optimum for both solids and liquids. In addition to the impact on PCR-based detection, concentration and extraction can impact sequencing methods (Hielmso et al., 2017).

Methods may vary significantly in performance across targets and different matrices. For example, filtration and ultrafiltration methods are often used to concentrate viruses in liquids based on adsorption or size exclusion, respectively, whereas centrifugation may be instrumental for concentrating bacteria and protozoa via density differences. Chemical flocculation or precipitation techniques can also be used to concentrate particles, thereby increasing the yield of target pathogens for analytical purposes. The efficacy of these methods can be variable, influenced by factors such as the pathogen target, the wastewater matrix (e.g., liquid versus solid phase, pretreatment level, age) and the chemical composition of samples (see Figure 3-2) (Pecson et al., 2021; Zahedi et al., 2021). Further, the study methodologies for comparing concentration methods varies between studies, with different target organisms, methods and matrices. North and Bibby (2023)

SOURCE: Parkins et al., 2023.

found concentration efficiencies for native targets were not representative of seeded targets, and that significant differences in method performance was demonstrated across native targets. Identification of the most effective concentration methods would require additional studies using a consistent study design, set of targets, and wastewater matrices across an array of wastewater samples.

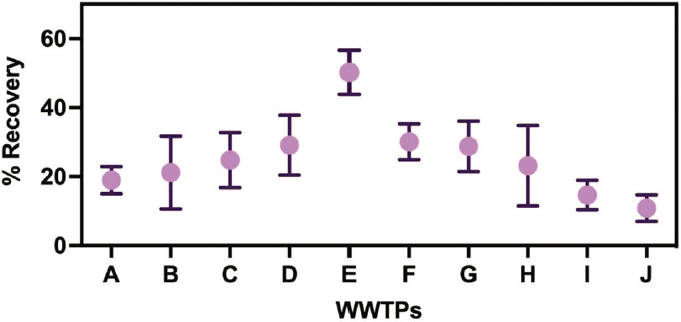

In the extraction step that follows concentration in wastewater surveillance for SARS-CoV-2, the selection of reagents and kits is pivotal to the isolation of nucleic acids from the concentrated sample. The efficiency and variability of these methods for a single target, but also between targets, can significantly impact the purity and quantity of the recovered genetic material, making comparability between methods difficult to interpret. In research exploring the variability among samples from the same site collected at different times during the same day for SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater, Bivins et al. (2021) noted that process recovery efficiency

SOURCE: Ahmed et al., 2022c.

was highly variable. Recent research efforts have shown that while commercially available extraction kits are widely used, the performance of various concentration and extraction procedures can vary significantly depending on the sample type and the presence of inhibitors (Bivins et al., 2021; Langan et al., 2022; Pérez-Cataluña et al., 2021; Steele et al., 2021). This necessitates careful selection and optimization of extraction methods for accurate wastewater-based epidemiology in COVID-19 surveillance. Furthermore, this variability calls for validation testing of commercial extraction kits using standardized samples and rapid dissemination of these results. Whitney et al. (2021) developed a kit-free extraction method, significantly enhancing RNA recovery efficiency, highlighting the potential of alternative approaches over traditional extraction kits.

Purification aims to alleviate the effects of inhibitors and other contaminants that could affect PCR amplification. Methods such as spin-column-based purification and bead-based magnetic separation are widely used (Ciannella et al., 2023). However, the efficiency of purification needs to be balanced against the potential loss of target nucleic acids, which is a trade-off that can affect sensitivity.

Without standardized concentration and extraction protocols, comparison of data between laboratories may be confounded (Servetas et al., 2022). Pecson et al. (2021) demonstrated the effect of different pre-treatment, concentration, extraction, and analysis methods across 32 different laboratories and 36 different standard operating procedures based on analysis of SARSCoV-2 concentrations from replicates at a single wastewater treatment plant (see Figure 3-3). Eighty percent of the sample results were within a 2.3 log range (200-fold difference), but the authors also reported that recovery efficiency across the methods (determined by human coronavirus OC43

SOURCE: Pecson et al., 2021.

matrix spike) varied by seven orders of magnitude (10-million fold; Pecson et al., 2021). Additionally, variability between repeated runs of the same protocol can directly impact the quality and reliability of the PCR results, reducing confidence in the surveillance outputs and further complicating the task of comparative analyses across different jurisdictions.

Within the NWSS, there exists a significant diversity in the methods employed, reflective of the unique circumstances and capabilities of individual laboratories and the desire to be as inclusive as possible during the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 3-4). As of May 2024, samples from 8.7 percent of NWSS sites were analyzed through a national testing contract, managed by Verily, which uses a single method for all sample processing and analysis, and 11.7 percent of NWSS sites were analyzed by WastewaterSCAN, which uses a different method (K. Cesa, CDC, personal communication, 2024). The remaining 80 percent of sites rely on individual public health laboratories that employ a diversity of methods. Feedback from local jurisdictions reveals an appreciation for the principle of standardization, but at the same time a reluctance to move away from their own established methods. This is due, in part, to concerns about being able to compare data from the new methods with the historical baseline, as well as an uncertainty about which methods are truly the best practices for their system, in light of the heterogeneous composition of wastewater across the nation. This preference underscores a tension between the need for standardized practices and the desire to maintain locally optimized methods. Development of a robust national wastewater surveillance system necessitates resolving this tension to ensure the production of reliable data that can be effectively compared across different programs, thereby facilitating more informed public health decisions. This resolution requires careful consideration of local needs and capabilities while striving for a level of standardization that enhances the overall quality and comparability of wastewater surveillance data.

As the demand for data from wastewater surveillance grows, there is an increasing need for the development of best practice guidelines that address the specific challenges of concentration, extraction, and purification in wastewater matrices (Ahmed et al., 2020; Servetas et al., 2022). Such guidelines should be informed by comparative studies that assess the performance of different methods under a variety of conditions, ultimately leading to a consensus on the most effective and reliable approaches for pathogen recovery prior to PCR analysis.

PCR Methods in Wastewater Surveillance

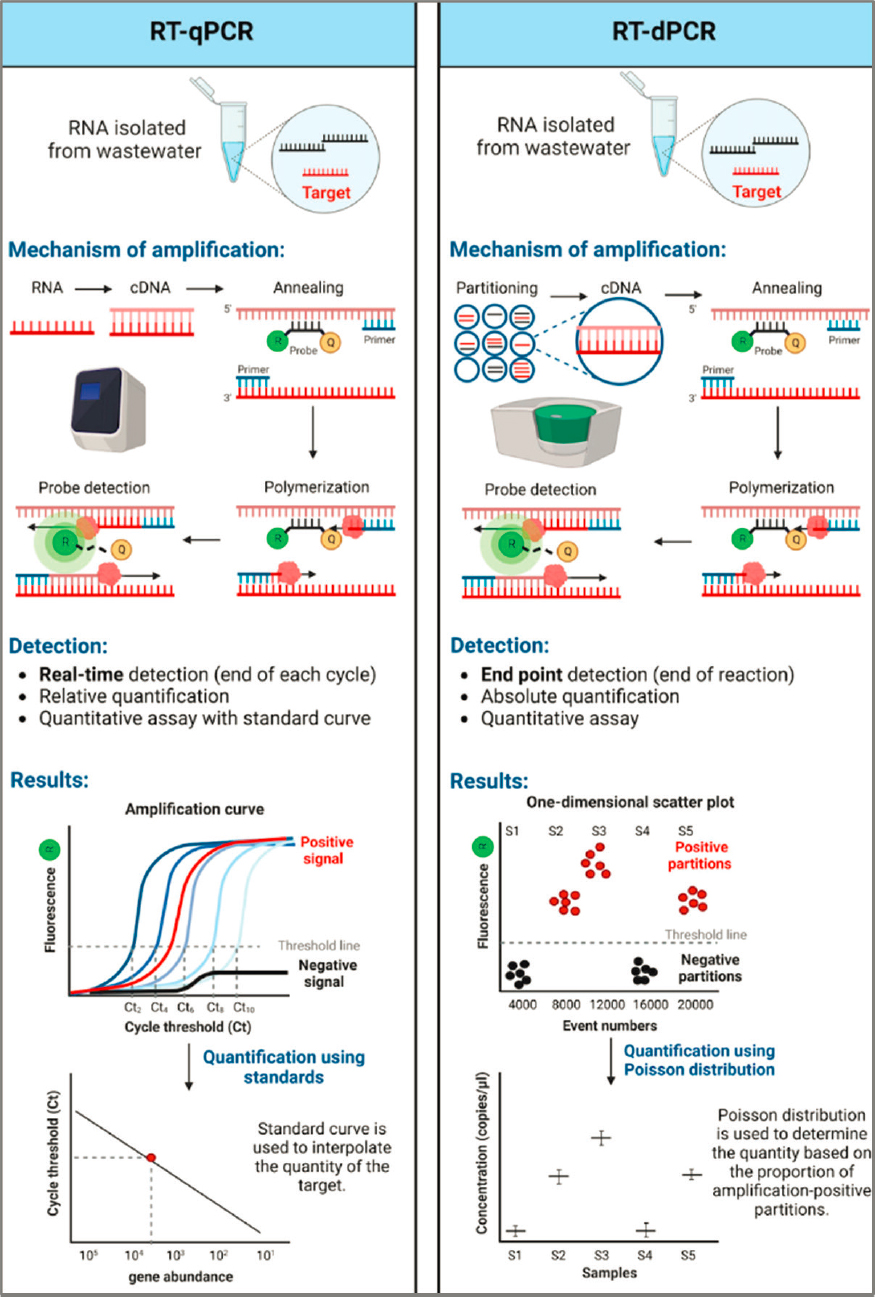

PCR techniques, specifically quantitative PCR (qPCR) and digital PCR (dPCR), are critical in wastewater surveillance for their ability to detect and quantify known pathogens with high sensitivity (see Figure 3-5). PCR-based

methods use primers that are specific to the target strain, variant, or antibiotic resistance gene to select and amplify nucleic acid segments, enabling pathogen detection in wastewater at low concentrations. Standard PCR-based methods target DNA but can be combined with reverse transcription (RT) to target RNA; qPCR uses real-time monitoring of fluorescence over each amplification cycle (termed quantification cycle, Cq) to quantify the original target gene copies in the sample, relative to a standard curve (Kralik and Ricchi, 2017). Due to its speed and efficiency, qPCR is widely adopted allowing for the quantitative analysis of a large number of samples in a relatively short time frame. It is particularly effective for pathogens present at higher concentrations (Ahmed et al., 2022b; Ciesielski et al., 2021). However, qPCR’s reliance on standard curves as a reference for quantification can be a limitation. Each time a new set of experiments is run, the standard curve must be meticulously recalibrated to ensure accuracy. This requirement for frequent recalibration introduces potential variability in the results, as slight differences in calibration can lead to different outcomes. The source of qPCR standards and how they are calibrated can vary significantly between laboratories and methods. The field lacks and would benefit from certified standards that are commercially available. This aspect of qPCR, while fundamental to its operation, can be a source of imprecision, especially when comparing results from different sets of experiments or different laboratories. Additionally, qPCR can be more susceptible than dPCR to inhibitors present in complex wastewater samples, which may affect its accuracy (Tiwari et al., 2022).

Unlike qPCR, dPCR provides absolute quantification by partitioning the sample into thousands of microreactions that are each measured by end-point fluorescence and enumerates based on a most probable number (MPN) statistical approach rather than requiring use of a standard curve. This feature reduces the impact of potential inhibitors and enhances the reliability and precision of the quantification, even in samples with low concentration targets in environmental samples with a high background of nontarget DNA (Ahmed et al., 2022b; Ciesielski et al., 2021). Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR), a subset of dPCR, further refines this process by using microdroplets to partition the sample, which allows for precise quantification in a highly reproducible manner. The high initial setup costs of dPCR can be a barrier to its widespread adoption. Typically dPCR also has a smaller dynamic range (about four orders of magnitude) and thus faces limitations when analyzing multiple targets simultaneously (i.e., multiplexing) with highly disparate concentrations in a sample. This can be overcome, however, if the expected range is known prior to the analysis, and adjusted via dilutions correction or through distribution in multiplex assays based on expected ranges. Additionally, recent advances in “next-generation”

SOURCE: Data from APHL, 2024.

dPCR technology have reported increased dynamic range (six orders of magnitude; Jones et al., 2016; Shum et al., 2022).

Both qPCR and dPCR have been useful in wastewater-based infectious disease surveillance. Overall, the selection between these methods has generally depended on the specific requirements of the surveillance program, the available resources, and the intended use of the data. However, multiplexing in wastewater surveillance underscores the distinct attributes of qPCR and dPCR. When addressing the need for simultaneous detection of multiple targets within a sample, the efficiency of qPCR can be compromised. In multiplexing scenarios, the competition for reagents and primer-dimer formations can lead to reduced efficiency and accuracy in qPCR. In contrast, dPCR, with its quantification based on the MPN approach, is less impacted by these factors. Because dPCR partitions the sample into numerous microreactions, each individual reaction is less prone to the complexities and interferences seen in qPCR multiplexing. In addition, because each molecule of target is run in a separate droplet reaction, mismatches in the target with the primer or probe, such as with changing variants of SARS-CoV-2, can be visualized with some dPCR platforms (Schussman et al., 2022). This partitioning effectively isolates the reactions, ensuring that PCR efficiency does not significantly hinder the quantification process. This independence from reaction efficiency in dPCR, along with its enhanced resistance to inhibitors, makes it a more reliable and accurate choice for quantifying diverse targets in multiple assays. The recent advancements in dPCR technology, allowing for a broader dynamic range comparable to that of qPCR (Shum et al., 2022), further reinforce its applicability in multiplexing.

Despite the higher initial setup costs and the requirement for specialized expertise, the precision and reliability of dPCR in complex multiplex assays advocate for its increasing utility in wastewater surveillance. Recently, the NWSS recommended laboratories use dPCR, as opposed to qPCR, because

dPCR is less subject to inhibition (Adams et al., 2024). Nevertheless, the strategic alignment of targets in multiplex assays, considering their concentration ranges and the nature of the targets (e.g., RNA vs. DNA, viral vs. bacterial) is an important consideration to ensure more consistent and reliable results across varied environmental samples. In minimizing the number of workflows, it may also be advantageous to couple pathogens with similar biochemical composition (e.g., coupling enveloped viruses together and coupling nonenveloped viruses together, or coupling DNA targets separately from RNA targets).

Biosafety and Laboratory Processing

One factor limiting the ability of laboratories to analyze wastewater pathogens is the necessity to adhere to biosafety protocols, which are determined based on the agent itself and the particular procedures to be undertaken. In the case of laboratories sampling wastewater for SARS-CoV-2 genetic material, which requires sample concentration as part of the testing, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have indicated that enhanced biosafety level 2 (BSL-2) procedures are needed. This includes a BSL-2 laboratory with unidirectional airflow and use of respiratory protection and a separate designated area for putting on and taking off personal protective equipment.1 CDC and the Water Environment Federation each have separate safety guidance for wastewater treatment plant workers sampling raw wastewater, including use of personal protective equipment (WEF, 2021).2

It should be recognized that, while BSL-2 laboratories are common, laboratories with certification at higher biosafety levels are less common and more expensive to design, operate, and conduct work in. Meanwhile, the concentration of pathogens in environmental samples (as opposed to clinical samples) is generally expected to be low, since in wastewater any human contributions are diluted with a large volume of carriage water in which the material is conveyed.3 However, after concentration of samples, the genome concentration per unit volume in environmental samples could be in the same range as clinical samples, although with a much lower likelihood of containing viable organisms. As of the writing of this report, there has not been isolation of viable SARS-CoV-2 virus (as opposed to its genetic material) in municipal wastewater, and the presence and levels

___________________

1 See https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/lab-biosafety-guidelines.html#environmental-testing.

2 See https://www.cdc.gov/global-water-sanitation-hygiene/about/workers_handlingwaste.html#cdc_generic_section_2-personal-protective-equipment-ppe.

3 An exception occurs when environmental samples are cultured for viable pathogens. In such cases, the levels of pathogens become higher.

SOURCE: Parkins et al., 2023.

of viable microorganisms should determine the risk. Therefore, it may be inappropriate to apply the level of stringency in biosafety requirements for wastewater analyses that would be used for clinical laboratory work with the same pathogens if the risk does not justify the additional burdens posed by enhanced BSL-2. The World Health Organization (WHO) recently approved BSL-2 control measures for “non-propagative diagnostic laboratory work” on SARS-CoV-2, such as sequencing (WHO, 2024).

It may be feasible to confine higher hazard operations (and hence the need for a higher-biosafety-level laboratory) to a small footprint, for example by pasteurizing or otherwise inactivating samples. This may be feasible if molecular signatures of pathogens are the only end point to be examined. Some researchers have shown that pasteurization has reduced RNA recovery for SARS-CoV-2 (Islam et al., 2022; Robinson et al., 2022), while others have shown enhanced recovery (Cutrupi et al., 2023; Trujillo et al., 2021). The wastewater matrix has also been shown to influence the effect of pasteurization on RNA recovery (Beattie et al., 2022). More research is needed to determine optimal pasteurization methods for wastewater surveillance if enhanced BSL-2 conditions are expected to remain. Additionally, metadata on sample pretreatment are important because of these effects.

When other pathogens are added to the wastewater surveillance panel, either for endemic or emerging pathogens, a formal risk assessment should be conducted to assess the needed degree of biosafety required based on the proposed sampling and analysis protocols. Ideally, these analyses should be conducted well in advance so that wastewater surveillance can be implemented both safely and quickly for emerging pandemic threats. In addition, the effect of any pasteurization or inactivation process on ultimate method performance (specificity and sensitivity) needs to be evaluated for each target pathogen.

As additional biological knowledge and information about target pathogens is acquired, biosafety practices can and should be reassessed to ensure that they reflect the most current understanding of the biosafety risk. Given the evolving understanding of SARS-CoV-2 risks associated with wastewater surveillance, the biosafety handling regulations around SARSCoV-2 should be reassessed to determine if enhanced BSL-2 procedures remain the appropriate handling guidance.

Sample Archiving

Short-term sample archiving is a necessary component of quality control in wastewater surveillance. Ideally, these samples would be archived for about 3 months to allow for reanalysis in case data anomalies or quality issues are raised. Retrospective investigation of infectious disease outbreaks could be facilitated by the existence of archived samples, as shown by

Teunis et al. (2004) with foodborne outbreaks. In most locations, short-term storage of concentrated, processed extracts for follow-up analysis would not require resources beyond those commonly found in analytical laboratories processing samples.

For a national wastewater surveillance program, a rotating, longer-term (multiyear) sample archive would be useful for understanding clusters of illness that may become apparent. Long-term archiving would not be necessary at every site or even every state. At a national scale, wastewater surveillance sites from several large cities across the country could be identified as key sites for long-term storage. Development of several longer-term archives would likely require purchase of additional -80°C freezers at those select locations.

CDC recommends that processed, concentrated wastewater surveillance samples be archived at -70°C,4 and the Association of Public Health Laboratories recommends storage at -80°C (AHPL, 2022). Raw, unprocessed samples are not typically recommended for archiving because of the large storage space required by raw samples as well as the effect of the freeze-thaw cycle on RNA recovery (Markt et al., 2021). Research suggests that longer-term (35–122 days) freezing of raw wastewater solids also reduced RNA measurements by an average of 60 percent (Simpson et al., 2021). Stability of RNA concentrated on filters after sample processing proved more promising and showed improved recovery after 19 days of storage at -80°C (Beattie et al., 2022). Yet, the integrity of RNA for long-term storage remains poorly understood. Different pathogens are likely to have different survival times under various storage conditions, and these storage effects on recovery need to be understood.

An in-depth research initiative is needed to refine and optimize the process for long-term archiving of wastewater samples. Research should examine best practices for long-term sample integrity at all stages of sample processing, including removal of solid particles and concentration of the microbial fraction (e.g., centrifugation, filtration), use of RNA stabilization solutions or reagents and their implication on downstream analytical methods, and rapid freezing protocols that prevent RNA degradation. Quality control considerations should also be included, such as sample homogenization methods (including even distribution of any stabilizing agent) and best practices for aliquoting the stabilized samples into small volumes. There is a need to develop a protocol for initial quality control checks, such as utilizing qPCR or dPCR to assess RNA integrity prior to storage, which will then serve as a critical baseline for subsequent periodic evaluations to ensure continued sample integrity over time. The research should also determine an ideal long-term storage duration that optimizes space efficiency without

___________________

compromising the integrity of the samples. Establishing a regular monitoring schedule to evaluate the integrity of the stored nucleic acids is vital for enabling timely interventions in the event of degradation. Collectively, these research needs should provide a thorough understanding of each step in the long-term archiving process.

Long-term archiving of wastewater samples also raises questions about what sorts of future analyses utilizing these samples are ethically acceptable. Analyses may, for instance, explore targets that were unknown at the time of sample collection and that contributing communities may view as involving potential stigmatization. In Chapter 4, the committee describes how an ethics advisory body could be helpful in weighing the risks and benefits of proposed secondary uses of NWSS digital data. This body could perform the same work for stored samples.

OPPORTUNITIES TO IMPROVE DATA UTILITY

There are opportunities for improving both data quality and data comparability to enhance the utility of NWSS data. Opportunities to improve data quality involve improving accuracy and precision of data within any given laboratory (intralaboratory). Opportunities for improving data comparability involve steps to characterize and minimize interlaboratory differences in methods or technical implementation of the methods so that data are comparable and relatable for a broader interpretation of the data regionally and nationally.

Improving Intralaboratory Data Quality

Quality data are essential for reliable interpretation and public health decision making. Within each laboratory, good data quality is important to the reliability of individual sample measurements and facilitates the interpretation of trends for repeated samples from a given site. Good intralaboratory data quality also strengthens the ability to compare the analytical results among different sites analyzed by a single laboratory.

Improving intralaboratory data quality decreases the inaccuracy and imprecision that may arise at any stage of the process, from sample storage to concentration method, RNA/DNA extraction, and PCR amplification. Data inaccuracies and imprecision can be associated with a wide range of sources including small deviations in the method protocol, instrument error, reagent variability, and analyst practices. As an example, it is well known that diverse extraction methods contribute to data variability (Figure 3-3). The data variability observed in one step can be amplified by subsequent steps in processing. For example, the extraction step directly affects the yield and purity of nucleic acids and, consequently, the resulting impurities

can impact the PCR reactions (Ahmed et al., 2022c). The following sections discuss several opportunities to improve the precision of measurements within a laboratory and also minimize intralaboratory variability: SOPs, robust quality assurance and quality control (QA/QC), analyst training and proficiency testing, and proper calibration and maintenance of laboratory equipment.

Development of, Validation of, and Adherence to SOPs

A best practice is that each laboratory developing or adopting a wastewater surveillance pipeline should take pains to vigorously evaluate the performance of its methods and validate its application to the types of samples that it receives. Detailed written SOPs specific to the laboratory should be developed for each method in a control chain with explicit details on procedures, reagents, instruments, safety, contraindications, etc., and this information should be made available to provide context for the measurements and aid in understanding observed differences. Deviations from SOPs should be discouraged for all samples, but recorded if they occur. Strict adherence to SOPs will help minimize variability between replicate samples. When a laboratory adopts a new method, initial precision recovery studies should be performed on seeded samples to understand the accuracy and precision. Further, ongoing precision recovery studies should be performed regularly to ensure method performance does not change over time. Matrix spike samples should be processed whenever new sites are brought online or when changes in the wastewater matrix occur to ensure that matrix effects do not adversely impact performance of the methods.

Each new pathogen target added to the wastewater surveillance panel (see Chapter 5) will require development of validated assays that demonstrate high sensitivity and specificity in wastewater to produce data that are both robust and reliable. Many pathogen assays have been developed for the clinical setting, and these assays will need to be demonstrated to work with environmental samples. For targets intended to be implemented nationally, CDC should harness the expertise of the NWSS Centers of Excellence and foster collaborations with academia and commercial interests to develop validated assays that meet performance criteria. Best practices for primer design for PCR assays include robust in silico analysis and performance testing designed to reduce the likelihood of false positives and increase the efficiency of PCR amplification. For targets that may have a more regional implementation, NWSS should define sensitivity and specificity guidelines to ensure that assays target relevant organisms, strains, or variants with the most current genomic sequences. In addition to assay validation, CDC, with assistance from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) or other appropriate national and international standard-setting bodies,

should recommend appropriate standards and spike control materials that can simulate the behavior of the target pathogens in wastewater and provide a reliable benchmark for assay performance.

Robust QA/QC

Minimum criteria for data inclusion that are aligned with the latest standards in PCR data generation and reporting are necessary to ensure quality data in a robust national wastewater surveillance system. These criteria include mandated use of standardized controls, reference materials, and calibration procedures that can be applied universally across various PCR platforms. Existing comprehensive guidelines and standards, such as the Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments (MIQE) guidelines (Bustin et al., 2009), its digital counterpart for dPCR (Huggett et al., 2013), and the Environmental Microbiology Minimum Information (EMMI) guidelines (Borchardt et al., 2021), provide a robust foundation for such a standardization effort. These documents should serve not merely as recommendations but as keystones in laboratory practice. Based on these established guidelines, NWSS should require the following as minimum criteria for data inclusion: use of proper performance controls, control verification, and performance limits for diagnostic assays. Results of these QA/QC steps should be reported as metadata along with data submission.

Use of proper performance controls.

Incorporation of appropriate seeded controls to assess total method recovery as a standard best practice helps in monitoring the efficiency of the sample processing pipeline and ensures performance as intended. Additional seeded controls may be warranted to evaluate performance of individual procedures within the sample processing pipeline (e.g., nucleic acid extraction recovery controls). In addition to the pathogen targets, performance controls for normalization targets should also be included (e.g., pepper mild mottle virus, CrAssphage [Carjivirus communis]; see Chapter 4) because the quantities of these targets are often incorporated in wastewater surveillance data. Seeded controls should be validated in parallel to intended targets during initial precision recovery studies to ensure adequacy as an indicator of performance.

Control verification.

Inclusion of appropriate positive and negative controls is essential to demonstrate the integrity of analysis. Data should only be included in NWSS if positive and negative controls behave as expected in every assay run, with positive controls confirming assay functionality and negative controls ensuring the absence of contamination. Use of inhibition controls should be required to minimize false negatives and evaluate effect

on quantitation. Inhibition controls should consist of the target nucleic acids, because different assays can exhibit different levels of inhibition. Inhibition control tests should be conducted at new locations and when wastewater characteristics change at a specific plant.

Performance limits for diagnostic assays.

Laboratories should validate and report the lower limit of detection (LOD) and the limit of quantitation (LOQ) for each assay used in their program, because these limits are essential for interpreting the significance of low-level detections. The MIQE guidelines (Bustin et al., 2009) and the EMMI guidelines (Borchardt et al., 2021) provide robust frameworks for defining these thresholds. According to these guidelines, LOD is commonly described as the lowest concentration detected with statistical significance using a given procedure or instrument, while LOQ refers to the lowest concentration at which the analyte can be quantitatively determined with acceptable precision and accuracy. According to these guidelines, analysts should perform rigorous validation studies, including the use of standard curves and control materials, to establish these limits for each assay. Standardizing the definition and determination of LOD and LOQ across laboratories will help minimize variability and ensure the reliability of surveillance data. Multiplexing should focus on targets that are expected to be in a similar range.

Analyst Training and Proficiency Testing

Education and training for laboratory personnel, emphasizing the importance of maintaining high-quality standards and following established protocols, are central to data quality. This should include the establishment of benchmarking and regular proficiency testing, enabling laboratories to gauge and calibrate their methods against standardized metrics. Records of personnel training and proficiency testing should be maintained and updated.

Proper Calibration and Maintenance of Instruments and Laboratory Equipment

Inadequate or lack of calibration for laboratory instruments and equipment can be a significant source of uncontrolled variability. This is especially the case if multiple similar instruments (e.g., PCR thermocylers, pipettors) are used interchangeably. Rigorous maintenance and calibration programs should be employed to ensure proper function and quantification, and any deviation from the regular schedule should be recorded.

Improving Interlaboratory Comparability

Maximizing data comparability between laboratories involves not only the data quality issues discussed in the previous section but other greater sources of variability, such as disparate methodologies implemented by different laboratories and differences inherent in the samples each laboratory receives (e.g., from vastly different systems, different types of samples; see Chapter 2). As additional targets are added to wastewater surveillance (see Chapter 5), the selection of sample processing methods is likely to reflect a prioritization of some targets over others, and these priorities may differ among public health jurisdictions. As with intralaboratory data quality, there are opportunities to minimize interlaboratory variability, although some variability is inherent that cannot easily be reduced. There are four main options to minimize interlaboratory variability: (1) defining explicit sample and performance acceptance criteria, (2) limiting methods only to those that perform as well as an approved reference method, (3) developing a standard method, and (4) normalization.

Defining Acceptance Criteria for Samples and Analytical Performance

Definition of explicit performance criteria for a method (e.g., defining the range of acceptable recovery, the lower limit of detection, or limit of quantification) can help to minimize interlaboratory variability. Definition of these types of parameters can allow laboratories the choice to select methods that will work in their setting while maintaining expectations on performance. This is perhaps the least restrictive approach to minimizing interlaboratory differences. Incentivization programs could be implemented to encourage laboratories to consistently meet or surpass these standards.

To improve comparability, the NWSS, in partnership with other standard-setting bodies or organizations, could also establish specific definitions for the equivalent sample volumes or effective sample volumes, which can control for different inputs into a diagnostic assay, accounting for differences in pre-analytical processing. The effective sample volume relates to the proportion of the original sample that is interrogated by the diagnostic assay (Fung et al., 2020). Equivalent sample volumes refer to the original sample volume that is analyzed in each PCR, accounting for sample processing (Crank et al., 2023). Research is needed to define the equivalent and effective sample volume necessary to meet NWSS quality objectives for their intended use cases for each target. Establishing effective and equivalent sample volumes is crucial as they directly influence the limit of detection and the overall interpretability of surveillance findings.

Requiring Performance Equivalent to Validated Reference Methods

A second approach would to be to establish a “gold standard” reference method by which to compare other methods. The reference method would be selected by CDC or the Centers of Excellence to meet performance criteria supportive of the designated use of the data for a particular target. Other methods could then be evaluated for equivalency to the reference against a performance panel. Once demonstrated equivalent, the other methods could be used by laboratories if it better meets their needs. The benefit of this approach is that the universe of methods is narrowed and flexibility is provided to the laboratories to select methods that work with their instrument platforms, experience, and other local conditions. Alternatively, CDC could maintain a limited list of approved and acceptable methods that have been designated as equivalent and/or fit for purpose. This is similar to how WHO has handled methods for polio surveillance.

Requiring Standard Methods

Standardization of all components of sample processing and analysis would seem to offer the greatest ability to minimize variability between laboratories. However, this is also the most onerous approach to accomplish and still would not fully control sources of variability between laboratories. Variability due to matrix effect, system differences, and analyst precision would not be adequately controlled by this standardization approach, and there is concern that differences among wastewater treatment plants may necessitate different methods. Further, forcing laboratories toward a single approach could limit adoption of the method for a variety of issues, such as experience with alternative methods, cost, and available instrumentation. Full standardization may also stifle scientific advancement and engagement by the commercial and academic sectors.

If standardization is determined to be the best way to improve interlaboratory comparability, CDC could couple standardization efforts with the establishment of a centralized certification program for wastewater surveillance. Centralized training could support laboratories in transitioning to these standardized methods, fostering a more unified approach to wastewater surveillance across the board.

Data Normalization

A final option is to control for variability between laboratories during the data analysis and reporting phase through a carefully vetted data normalization process, which, as discussed in detail in Chapter 4, has yet to

be identified. This approach is incumbent on well-validated methods and high-quality data for all laboratories involved, but, ideally, data normalization could adjust for differences in analytical methods used or system characteristics. Further discussion of normalization can be found in Chapter 4.

A Way Forward

A thorough analysis of existing data and methods used can help determine whether a limited number of sample processing and analytical approaches can achieve adequate data quality to achieve data comparability objectives for the NWSS. However, such analyses require metadata on pre-analytical and analytical methods and controls (and similar reporting as required by EMMI guidelines) be provided along with reported results. The reporting requirements need to be detailed enough to identify slight differences in the applications of the same method across different laboratories. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning should help analyze large data sets to identify the largest sources of variability (see Chapter 4). NWSS may also benefit from lessons learned from ongoing research at the Environmental Protection Agency Office of Research and Development, which is working to develop comparable PCR methods (a standard method and/or performance metrics) for viable pathogens in wastewater to better understand recreational exposure risks and potential drinking water effects.

Once the sources of data variability are well understood, CDC will need to determine the best strategy from those listed above to ensure the production of reliable data that can be effectively compared across the NWSS platform, thereby facilitating more informed public health decisions. This decision requires careful consideration of local needs and capabilities while striving for a level of standardization that enhances the overall quality and comparability of wastewater surveillance data.

Looking Ahead

Technology development offers potential for further improving data quality in wastewater surveillance analysis. For example, support for technologies that automate and standardize steps within the PCR process, including liquid handling, concentration, extraction, and purification, could potentially reduce human sources of error and variability. Innovation in real-time sampling and analysis technologies could spark a quantum leap in wastewater surveillance. The immediacy with which data can be acquired paves the way for a more nimble and precise response to emergent public health threats, an attribute that is indispensable for the early detection and containment of infectious diseases. The sophistication of real-time analysis

tools lies in their ability to detect a broader spectrum of pathogens and substances, including those at lower concentrations that might elude traditional methods. As these technologies evolve to become more user friendly, their application could expand into varied environments, bridging the gap in public health surveillance capabilities, particularly in resource-constrained settings. Such democratization of health monitoring tools is vital for equitable public health interventions.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The observed diversity and the lack of standardization in analytical methodologies for wastewater surveillance have led to significant variability and decreased comparability of data from different sites. The wastewater surveillance system developed through rapid research and innovation, and the resulting interlaboratory variability in methods for extraction, purification, amplification, and data reporting, limits understanding of trends in pathogen concentrations across sites. A wastewater surveillance system with comparable data will better support effective public health interventions at regional and national scales.

Rigorous data analysis efforts are needed to determine whether a single standardized analytical method is necessary to improve NWSS comparability or whether other approaches are reasonable. To minimize interlaboratory variability, the committee identified four alternative strategies: (1) defining acceptance criteria for performance, (2) limiting methods only to those that perform as well as an approved reference method, (3) developing a standard method, and (4) using as yet undiscovered data normalization approaches. Research on the sources of variability in sample processing and analysis is essential to identify the best alternative (or some combination) to improve comparability while balancing associated trade-offs. Full method standardization for sample processing and analysis could offer the greatest ability to minimize interlaboratory variability but it may also stifle scientific advancement.

Rigorous quality control standards should be developed to increase the reliability and interpretability of NWSS data. The NWSS should enforce criteria for data inclusion, including standardized controls, reference materials, and calibration procedures. The committee recommends several best practices for reducing intralaboratory variability, including development and adherence to SOPs that are made available to others, adoption of widely recognized QA/QC guidelines to ensure data consistency and integrity, use of performance controls, and use of positive and negative controls. Additionally, establishing a centralized certification program for wastewater surveillance laboratories, including benchmarking and proficiency testing programs, will align wastewater surveillance methods with these

standards. CDC and its Centers of Excellence should develop validated assays for current and new targets with defined sensitivity and specificity. By spearheading these validation efforts and setting forth recommendations for standard materials, spike controls, and equivalent and effective sample volume parameters, CDC, with assistance from NIST and other standard-setting bodies, can bolster the consistency and comparability of data across surveillance efforts and also expedite the acceptance and integration of novel assays as new targets are added.

NWSS should develop a national system and guidelines for sample storage and invest in research to optimize long-term archiving for wastewater. In a national infectious disease wastewater surveillance system, short-term archiving (approximately 3 months) of all processed samples is essential for quality control, but several large sites should be identified for longer-term multiyear archiving. Several long-term archives would be valuable for retrospective analyses if a new pathogen is detected that was not previously analyzed. A regular monitoring schedule should be developed to assess the integrity of stored nucleic acids, enabling timely interventions if degradation is detected.

CDC should update its risk assessment for laboratories engaged in wastewater surveillance and re-evaluate the necessity of the biosafety level (BSL) 2 enhanced with BSL-3 precautions requirement. BSL-2 laboratories are common, but higher levels are less common and more expensive to design and operate. The understanding of the risks of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater analyses has evolved with time, and future NWSS targets have been identified to inform an updated analysis, recognizing that the required biosafety level is a function of the pathogen, its concentration (and viable state), and the nature of the procedure being undertaken. BSLs applicable to clinical laboratories may not be appropriate for environmental laboratories because of differences in concentrations and laboratory procedures. WHO recently approved BSL-2 controls for nonpropagative laboratory analysis for SARS-CoV-2.