Long-Term Health Effects of COVID-19: Disability and Function Following SARS-CoV-2 Infection (2024)

Chapter: 3 Selected Long-Term Health Effects Stemming from COVID-19 and Functional Implications

3

Selected Long-Term Health Effects Stemming from COVID-19 and Functional Implications

Long COVID is associated with a wide range of new or worsening health conditions and encompasses more than 200 symptoms involving many different organ systems (Davis et al., 2021; Lubell, 2022). Given the extensive range of symptoms, there have been attempts to cluster these health effects, but to date no consensus in this regard has been reached.

This chapter begins with an overview of the full range of symptoms and health effects associated with Long COVID and a summary of the condition’s epidemiology. The chapter then focuses on three health effects of Long COVID that may not be captured in SSA’s Listing of Impairments but can significantly affect one’s ability to participate in work or school: chronic fatigue and post-exertional malaise (PEM), post–COVID-19 cognitive impairment (PCCI), and autonomic dysfunction. Although a great number of Long COVID health effects could impact function, the committee thinks it will be useful for SSA to become familiar with these three, as they are particularly challenging to treat because of their multisystem nature. (See Chapter 5 for an overview of similar multisystem chronic conditions.) These are the novel conditions for which people seek out Long COVID clinics. For each of these three health effects, the chapter provides an overview of

- the frequency and distribution of their severity and duration in the general population, as well as any differences along racial, ethnic, sex, gender, geographic, or socioeconomic dimensions, or differences specific to populations with particular preexisting or comorbid conditions;

- clinical standards for diagnosis and measurement of each of these health effects;

- any special considerations regarding identification and management of these health effects in special populations, including pregnant people and those with underlying health conditions;

- best practices for quantifying the functional impacts of these health effects; and

- identified challenges for clinicians in evaluating persons with these health effects.

The symptoms and health effects discussed in detail in this chapter do not represent the full range of effects experienced by patients with Long COVID. In an effort to be inclusive, the committee includes at the end of this chapter annex tables organized by body system of selected health effects associated with Long COVID, along with their potential functional impacts and selected management guidelines.

OVERVIEW OF HEALTH EFFECTS ASSOCIATED WITH LONG COVID

Epidemiology of the Long-Term Health Effects of SARS-CoV-2 Infection

Data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) National Health Interview Survey show that in 2022, 6.9 percent of U.S. adults and 1.3 percent of children had Long COVID at some point, while 3.4 percent of adults and 0.5 percent of children had Long COVID at the time of interview (Adjaye-Gbewonyo et al., 2023; Vahratian et al., 2023). Based on these surveys, it is estimated that approximately 8.9 million adults and 362,000 children reported Long COVID symptoms in the United States in 2022 (Adjaye-Gbewonyo et al., 2023; Vahratian et al., 2023). Among adults in the United States, data from the CDC’s Household Pulse Survey show that the prevalence of Long COVID declined from 7.5 percent in June 2022 to 5.9 percent reported in January 2023, then increased to 6.8 percent in January 2024 (NCHS, 2024). Despite an overall decline in prevalence since June 2022, Long COVID’s disease burden remains substantial. In January of 2024, approximately 22 percent of adults with Long COVID reported significant activity limitations (NCHS, 2024).

The body of epidemiological research shows great variation in the incidence and prevalence of the long-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection. These variations reflect the dynamic changes in the pandemic itself, as the virus has evolved and spawned many variants and subvariants throughout the pandemic’s course; the effect of vaccines, which were introduced in December 2020 and later shown to reduce the risk of long-term health effects; and the effect of treatments for acute infection (e.g., steroids,

antivirals), which may reduce the risk of long-term health effects. In addition, since awareness about Long COVID in the medical community and the public is still lacking, reported prevalence may be an underestimate.

Adding to this complexity is the broad multisystem nature of the long-term health effects of SARS-CoV-2 and the fact that these effects are expressed differently in different age groups and sexes and by baseline health (Maglietta et al., 2022; Rayner et al., 2023; Tsampasian et al., 2023; Wong et al., 2023). Variation in incidence and prevalence estimates also stems from heterogeneities in study designs, including choice of control groups (e.g., whether studies included people with negative SARS-CoV-2 tests or no known SARS-CoV-2 as controls); methods used to account for the effect of baseline health in ascertaining whether the emergence of specific health effects following infection represents new disease; specification of outcomes; and other methodological differences.

Because of the considerable variation in estimates of the long-term health effects seen in Long COVID, the committee presents average estimates for different body systems based on the published literature. Among people who had COVID-19, most estimates of long-term cardiovascular health effects, which comprise a broad array of sequelae, regress around 4 percent (Xie et al., 2022b). Neurological and psychiatric conditions are also common among people who had COVID-19, with estimates of around 6 percent (Harrison and Taquet, 2023; Ley et al., 2023; Taquet et al., 2021, 2022; Wulf Hanson et al., 2022; Xie et al., 2022a; Xu et al., 2022). The reported incidence of gastrointestinal disorders post–COVID-19 is highly variable, but estimates suggest 6 percent (Xu et al., 2023). Respiratory problems persist in some people following SARS-CoV-2 infection, and prevalence studies at 6 months to 2 years suggest estimates of 2–4 percent (Wulf Hanson et al., 2022). Endocrine conditions are estimated to affect 1–2 percent of people previously infected with SARS-CoV-2 (Ssentongo et al., 2022). Similarly, estimates of the prevalence of genitourinary disorders is around 1 percent (Kayaaslan et al., 2021).

Terminology

The committee considers a health condition to be a state, including injury, illness, or physical or mental diagnosis, that adversely affects a person’s physical and/or mental health and well-being. A symptom is a subjective manifestation of disease experienced and reported by a patient, while a sign is an objective manifestation of disease that an examining practitioner can observe or measure (King, 1968; NIH, n.d.). In the context of this study, the committee uses health effects as an umbrella term that includes symptoms, health conditions, and other sequelae caused by or associated with prior infection with SARS-CoV-2.

Full Range of Health Effects

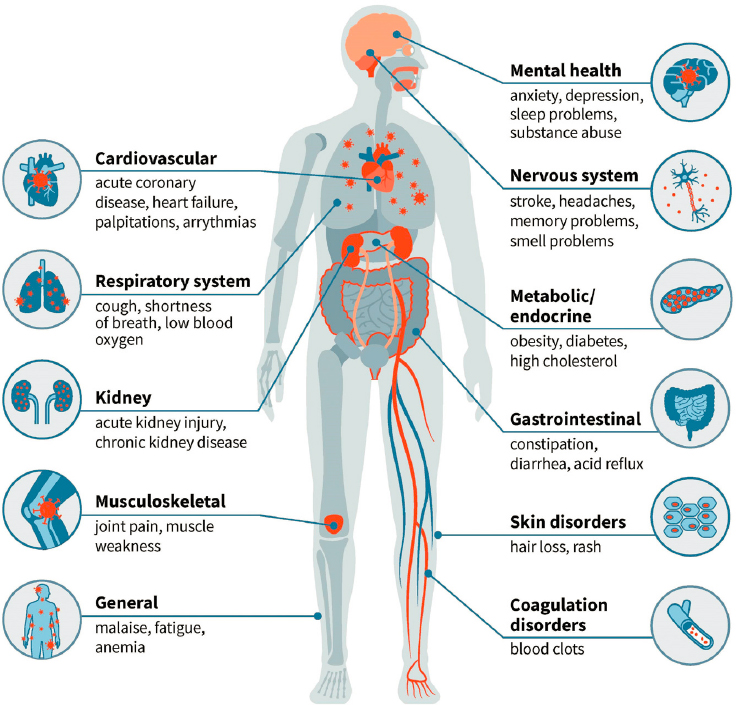

SARS-CoV-2 infection can lead to post-acute and long-term health effects in nearly every organ system (see Figure 3-1). As described in Chapter 1, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health model of disability identifies three domains of functioning: body functions and structures (i.e., physiological functions of the body, including psychological functions, and functioning of body structures), activity (i.e., actions or tasks), and participation (i.e., performance of tasks in a social context, such as school or work), all of which are mediated by personal and environmental factors that can either enhance or diminish an individual’s activity and participation (WHO, 2023b). Health effects associated with Long COVID may manifest as impairments in body structures and

SOURCE: Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

physiological functions, with resulting activity limitations and restrictions on participation. The impairments associated with Long COVID may affect mental (e.g., cognitive, psychosocial, emotional) functioning as well as physical functioning. In addition, individuals with Long COVID may experience multiple and potentially overlapping symptoms and conditions, including PEM, PCCI, and autonomic dysfunction. A number of preexisting conditions (e.g., diabetes, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, dementia) can increase the risk of adverse outcomes from SARS-CoV-2 infection, both during and following acute infection (Awatade et al., 2023; Dubey et al., 2023; Núñez-Gil et al., 2023; Steenblock et al., 2022; Treskova-Schwarzbach et al., 2021). Although persistent health effects associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection may include worsening of preexisting conditions, this chapter focuses primarily on newly acquired conditions. Health care providers and patients need to be aware of potential worsening of preexisting conditions and continue to monitor and treat them as needed. Additionally, the variable health effects of Long COVID may have different impacts on different patients depending on the burden of the preexisting condition, further emphasizing the need for a patient-specific approach for monitoring and treatment of health conditions.

Annex Tables 3-1 through 3-11 at the end of this chapter list selected health conditions associated with Long COVID in adults, organized by body system. Annex Table 3-12 lists selected health effects that are not organ system–specific, including chronic fatigue and PEM, ME/CFS, and fever. These tables include a summary of the potential functional implications of the conditions, selected clinical guidelines for their diagnosis and management, and potentially relevant SSA Listings for adults, where applicable. For the functional implications, the committee chose to focus on the kind of information that SSA collects about functioning in adults, which comes from a variety of sources, including the applicant, medical providers, employers, and other third parties with knowledge of the applicant. Information collected about physical functioning encompasses such activities as sitting, standing, walking, lifting, carrying, reaching, gross manipulation (e.g., handling large objects), fine manipulation (e.g., handling small objects, writing, typing), climbing, and low work (e.g., stooping, crouching, kneeling, crawling) (SSA, 2020). Annex Table 3-13 lists the physical; vison, hearing, and speaking; and mental activities the committee considered in populating the tables, along with their definitions. The committee populated the column on potential functional limitations based on the members’ collective expertise. SSA also collects information about the applicant’s ability to perform various daily activities, such as dressing, bathing, self-feeding, and using the toilet, as well as preparing meals, doing house- and yardwork, getting around, and shopping.

The long-term health effects associated with Long COVID can affect people across race, ethnicity, sex, gender, and age groups. Generally, the risk—on the relative scale—of these long-term health effects increases according to the severity of acute infection: the risk is 2–3 times greater in people who were versus were not hospitalized, and greatest in people who required intensive care (Núñez-Seisdedos et al., 2022; Xie et al., 2022b). However, because most people infected with SARS-CoV-2 experience mild or moderate disease that does not require hospitalization, those with mild or moderate cases constitute the majority of individuals with long-term adverse health effects of SARS-CoV-2 (Lai et al., 2023; Spagnuolo et al., 2020). Rates of Long COVID among pregnant women who had COVID-19 during pregnancy are similar to those of the general population (Kandemir et al., 2024). In addition, among pregnant women with COVID-19 at delivery, rates of caesarean delivery and frequency of maternal complications increased (Knight et al., 2020; Prabhu et al., 2020). The risk of Long COVID among adult females is about twice that among adult males (Munblit et al., 2021; Perlis et al., 2022; Sudre et al., 2021). Some pediatric studies also report a higher prevalence of Long COVID in female compared to male children and adolescents, although the exact risk is still undefined (Vahratian et al., 2023; Zheng et al., 2023).

Some of the long-term health effects of acute SARS-CoV-2 infection are chronic and can negatively impact individuals’ quality of life; ability to participate in the labor market or school; and, in some cases, life expectancy. The extent to which the long-term health effects of infection will have a functional impact on a person’s life and ability to work or participate in school can depend on health and functional status prior to COVID-19 and the severity of the medical condition(s). In addition, symptoms and related functional limitations may fluctuate, waxing and waning over time.

Clustering of Health Effects

Given the vast number of symptoms and health effects associated with Long COVID, several research groups have attempted to cluster patients with similar effects to better understand the disease (see Table 3-1).

The committee found that the evidence on clustering of the post-acute and long-term health effects of SARS-CoV-2 remains inconsistent across studies as a result of differences in study designs, populations studied, enrollment criteria, the era in which the study was undertaken (reflecting the possible differential effect of variants, changes in clinical care, and vaccination on phenotypic clusters), specification of post-acute and long-term health effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection, methodological approaches to clustering, and other factors. These differences yielded inconsistent results

TABLE 3-1 Research on Clusters of Long COVID Health Effects

| Reference | Population and Study Type | Time after Initial COVID-19 Infection | Clustering Methodology | Proposed Long COVID Symptom Clusters | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canas et al. (2023) | Prospective cohort study, 9,804 UK-based adults | 84 days | Unsupervised clustering analysis of time-series data, additional testing using data from Covid Symptom Study Biobank |

|

Subclusters determined for wild-type variant in unvaccinated people, alpha variant in unvaccinated people, and delta variant in vaccinated people. |

| Evans et al. (2021) | PHOSP-COVID cohort, 1,077 UK adults | 2 and 7 months | Clustering large applications k-medoids approach |

|

46% in the mild cluster. Full recovery reached in 3% of the very severe cluster, 7% of the severe cluster, 36% of the moderate cluster, and 43% of the mild cluster. Elevated serum C-reactive protein was positively associated with cluster severity. |

| Fischer et al. (2022) | Predi-COVID cohort in Luxembourg, 288 participants | 12 months | Hierarchical ascendant classification |

|

48% in the mild cluster. Severe cluster had a higher proportion of women and smokers. |

| Reference | Population and Study Type | Time after Initial COVID-19 Infection | Clustering Methodology | Proposed Long COVID Symptom Clusters | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frontera et al. (2022) | 242 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 | 12 months | Unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis |

|

The study administered psychological therapy and medications to cluster 2 and PT or OT to cluster 3. They found 100% of those who received psychiatric therapy, 97% who received PT/OT, and 83% who received few interventions improved over time |

| Goldhaber et al. (2022) | UC San Diego health system, 999 respondents | Unspecified | Exploratory factor analysis |

|

Neurocognitive burden associated with depression and anxiety. Musculoskeletal burden associated with older age |

| Kenny et al. (2022) | Multicenter prospective cohort, 233 individuals, 77% mild initial illness | 4 weeks or more | Multiple correspondence analysis on the most common self-reported symptoms and hierarchical clustering |

|

Clusters 1 and 2 had greater functional impairment, longer work absence |

| Kisiel et al. (2023) | 506 patients from 3 Swedish cohorts, mostly hospitalized | 12 weeks or more | K-means cluster analysis and ordinal logistic regression were used to create PCS scores |

|

59% in the mild cluster. Cluster 3 had the most reduced work ability. Smoking, high BMI, diabetes, and COVID-19 onset severity were predictors of cluster 3. |

| Thaweethai et al. (2023) | Prospective cohort study of 9,764 adults at 85 enrolling sites in 33 states plus Washington, DC, and Puerto Rico | 6 months or more | Unsupervised machine learning |

|

Using least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO), found most representative Long COVID symptoms to be smell/taste, PEM, chronic cough, brain fog, and thirst. |

| Tsuchida et al. (2023) | Adolescents and adults in an outpatient clinic in Japan | 2 months or more | Cluster analysis was performed using CLUSTER (SAS Ver 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), and cluster classification was performed. |

|

Clusters 2 and 3 had higher proportions of autonomic nervous system disorders and leave of absence from work and school |

| Wulf Hanson et al. (2022) | Pooled 54 studies and 2 medical record databases with data for 1.2 million individuals from 22 countries | 3 months | Selected based on reporting frequency in published studies and availability of health state in Global Burden of Disease study |

|

Among individuals with COVID-19, 6.2% had long COVID at 3 months: 10.6% for female adults, 5.4% for male adults, 2.8% for children and young people. |

| Yong and Liu (2022) | Review of 43 studies on Long COVID | 3 months or more | “narrative review” of the literature (not systematic) |

|

Among individuals with Long COVID symptoms 3 months after symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection, an estimated 15% continued to experience symptoms at 12 months. |

across studies, making it challenging to weave the evidence into a coherent narrative to inform policy discussions and clinical care. The heterogeneity of results reflects both the nascency of the field (less than 3.5 years old) and the complexity of Long COVID itself. The generation of better-quality and more consistent evidence will require consensus on terms, definitions, and methodological approaches.

SELECTED MULTISYSTEM HEALTH EFFECTS ASSOCIATED WITH LONG COVID

Three health effects associated with Long COVID that have a significant effect on functioning and are particularly challenging to manage—chronic fatigue and PEM, PCCI, and autonomic dysfunction—are reviewed in this section. There is significant overlap among the symptoms associated with these conditions.

Chronic Fatigue and Post-Exertional Malaise

PEM, also called post-exertional symptom exacerbation, is characterized by a severe worsening of fatigue and other symptoms following physical, mental, social, or emotional exertion that would not typically cause such a reaction in healthy individuals. This exacerbation of symptoms can occur immediately after the stressor or can be somewhat delayed (hours to days). In addition, an episode of PEM can last for days or even weeks. The specific symptoms that worsen vary among individuals, but often can go beyond fatigue to include muscle or joint pain, cognitive difficulties, sleep disturbances, headaches, flu-like symptoms, and/or gastrointestinal disturbances (Vernon et al., 2023).

Fatigue, broadly defined as a distressing or persistent tiredness that is neither proportional to recent activity nor alleviated by rest (Sandler et al., 2021; Twomey et al., 2022), is the most dominant symptom of Long COVID in several studies, ranging from 19 percent to 76.3 percent of patients (Cheung et al., 2023; Hartung et al., 2022; Ho et al., 2023; Kayaaslan et al., 2021; Líška et al., 2022; Sánchez-García et al., 2023; Štſpánek et al., 2023). Of the many descriptive studies that have captured fatigue and other symptoms seen in Long COVID, only a small proportion make a point of measuring PEM. In a large cross-sectional sample of adults who were selected from post–COVID-19 online groups, PEM was reported by 89.1 percent (95% confidence interval [CI] 88–90%); for most participants, PEM lasted a few days (Davis et al., 2021). A recent analysis of the National Institutes of Health Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery (RECOVER) longitudinal study was aimed at developing and validating a quantitative definition of Long COVID using multiple symptoms. In that study, PEM was reported in 87 percent of patients identified as having Long COVID (Thaweethai et al., 2023).

Diagnosis

Both post-COVID fatigue and PEM are generally diagnosed based on patient-reported symptoms and a detailed medical history. Typically, a thorough medical evaluation—which may include blood tests, imaging studies, and other diagnostic tests—is conducted to rule out other possible causes or contributing factors.

In clinical settings, health care providers typically evaluate chronic fatigue and PEM by asking patients to describe their symptoms in detail, including by inquiring about the type of exertion (physical, emotional, or mental) that leads to worsening of symptoms; the duration and severity of the symptom worsening that follows those stressors; how long it takes for the symptoms to return to baseline; what symptoms are experienced; and whether there is a prodrome related to the worsening of the symptoms. Multiple validated questionnaires can be used to measure a person’s perception and severity of fatigue and PEM (Davenport et al., 2023; FACIT, 2021), such as the DePaul Symptom Questionnaire–Post-Exertional Malaise (DSQ-PEM), which captures the frequency and severity of PEM symptoms (Bedree et al., 2019; Cotler et al., 2018; Davenport et al., 2023; FACIT, 2021).

One approach to diagnosing PEM, investigated in myalgic encephalitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) but not yet in Long COVID, involves two consecutive days of cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) (Stevens et al., 2018). Deconditioned adults and those with other chronic conditions show minimal variation between the first and second day of CPET measurement. In ME/CFS patients with PEM, multiple studies reveal a significant decline in oxygen consumption (V∙ O2) at peak performance and the ventilatory anaerobic threshold on the second day of CPET testing (Davenport et al., 2019; Stevens et al., 2018). The ventilatory anaerobic threshold reflects a person’s ability to sustain continuous work and is more related to everyday exertion. This drop in V∙ O2 between the first- and second-day CPET measurements suggests that patients with PEM risk entering anaerobic metabolism during activities they could have completed without it just the day before (Stevens et al., 2018). In ME/CFS, symptoms most associated with PEM after exercise include cognitive dysfunction, reduced self-reported daily functioning, and mood disturbances (Chu et al., 2018). Although 2-day CPET helps with understanding the physiologic response to exercise in patients with PEM generally, there are health system and patient-level barriers that potentially limit the broad implementation of 2-day CPET in diagnosing PEM in Long COVID and ME/CFS. The health system barriers include limited or inequitable access to CPET, with even fewer trained clinicians who can apply and interpret 2-day CPET to diagnose PEM. Patient-level barriers include prolonged recovery from testing and the prohibitive cost of testing without adequate insurance coverage. Several studies have explored the role of CPET in Long COVID, but not all

have used PEM as an inclusion criterion (Baratto et al., 2021; Durstenfeld et al., 2022; Evers et al., 2022; Wernhart et al., 2023). Although much of the existing research on 2-day CPET in PEM has been in patients with ME/CFS, the findings should be expected to generalize, regardless of suspected onset. Nevertheless, additional research is needed to compare 2-day CPET results in Long COVID versus ME/CFS.

Functional Impacts

Chronic fatigue symptoms in Long COVID impact a person’s ability to work and perform activities of daily living, which makes clinical care and rehabilitation a priority for these patients (Walker et al., 2023). They can also impact productivity by preventing a return to pre-COVID functional levels, thereby affecting the social and economic health of the impacted individual. A cross-sectional observational study on the impact of fatigue on function in 3,754 Long COVID patients, conducted at 31 post-COVID clinics in the United Kingdom, found that 94 percent (3,541) were of working age (18–65 years). Half (n = 1,321/2,600, 50.8 percent) of those who completed the “working days lost” questionnaire reported the loss of at least 1 day of work in the last month. Approximately 20 percent (20.3 percent) reported losing 20–28 days of work, and 20 percent also reported the inability to work completely. These results were associated mainly with fatigue (Walker et al., 2023). Symptoms of chronic fatigue in Long COVID may also influence a person’s attitudes toward leisure time, thereby impacting mental health functioning and perceived stress.

Since PEM is considered a hallmark symptom for diagnosing ME/CFS (CDC, 2021b; IOM, 2015; NICE, 2021d), Long COVID patients with PEM may also fit criteria for ME/CFS. Understanding the functional impact of PEM is made more challenging by the fluctuating nature of the symptom complex and the fact that often people can compensate for limitations in function by first making compensatory changes in the time, effort, and resources they ascribe to certain tasks or by making compensatory changes in their social or leisure activity patterns (NICE, 2021d).

One recent study comparing PEM symptoms in Long COVID with those in ME/CFS found that the PEM symptoms were more likely to improve over 1 year in individuals with Long COVID, while there was no improvement in those with ME/CFS. However, 51 percent of the individuals with ME/CFS in this study had already had symptoms for >4 years, while 82 percent of those with Long COVID had had symptoms for <1 year (Oliveira et al., 2023). In a large cross-sectional sample of adults selected from post–COVID-19 online groups, those participants who had versus those who did not have PEM at 6 months or more after their COVID-19

illness had a significantly higher average number of Long COVID symptoms that persisted beyond 6 months (Davis et al., 2021). In a smaller cross-sectional analysis of more than 200 adults with at least 4 weeks of persistent symptoms after acute COVID-19 illness, PEM was associated with more severe fatigue and a higher risk of work status limitations, no or low physical activity, lower general health, and lower social functioning (Twomey et al., 2022). In a population-based longitudinal cohort study, PEM was associated with increased risk of other symptoms, such as insomnia, cognitive impairment, headache, and generalized pain, compared with those with fatigue without PEM. The presence of PEM was also associated with increased risk of functional impairment, reduced work capacity, and reduced physical activity (Nehme et al., 2023). Similarly, another population-based longitudinal study conducted in Switzerland describing the long-term trajectory of post-COVID symptoms in adults at 1, 2, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 months after SARS-CoV-2 infection found that PEM was more likely in those who had worsening of or no change in their perceived health status compared with those who reported improvement or showed continued recovery (Ballouz et al., 2023).

Treatment

When PEM is identified, the focus of treatment turns to comprehensively assessing and managing the functional impact of these symptoms, along with other Long COVID–related symptoms. When PEM is present, rehabilitation interventions and other treatment approaches may need to be personalized to enhance patient safety (Herrera et al., 2021; WHO, 2023a). For physical activity, the anerobic threshold can be used as the physical activity ceiling for safe activity to avoid PEM, recognizing that the nature of PEM is that the anerobic threshold may vary based on the patient’s previous activities and other recent stressors (Davenport et al., 2010).

In addition to using self-report questionnaires to capture the severity of patients’ fatigue and functional limitations, clinicians may ask patients to track their activities in detailed diaries to better capture the types of activities that are most likely to trigger PEM for each individual. Preventing PEM or lessening its severity may require identifying those triggering factors, such as physical, mental, and emotional stressors; orthostatic intolerance; hormonal factors in women; environmental factors (humidity and extreme temperatures); sensory stimuli (light, noise, and smells); certain foods; and infections, including reinfections with SARS-CoV-2. Teaching patients to respect their physiological limits is an important aspect of managing PEM. An important aspect of rehabilitation for people living with PEM is the provision and use of assistive products and environmental modifications to

prevent PEM and its functional impact (WHO, 2023a). Therefore, another important aspect of management is facilitating work or school accommodations that may be necessary to prevent PEM (e.g., flexible hours, telecommuting options, specialized equipment to reduce physical or cognitive exertion).

Selected Populations

To date, few research studies have explored differences in PEM’s prevalence, severity, and functional impact by race/ethnicity, rurality, or other social factors. A study using the TriNetX database to look at the use of outpatient rehabilitation for a post-COVID condition did find that Hispanic individuals had a significantly higher incidence of fatigue (Hentschel et al., 2022). There also is a scarcity of information on Long COVID fatigue and PEM and the impact of the condition in pregnant and lactating women, even though women appear to be at higher risk for the condition (Pagen et al., 2023).

Post-COVID-19 Cognitive Impairment

Cognitive impairment has emerged as one of the most commonly reported health effects associated with Long COVID, potentially portending significant consequences for patient functioning and quality of life. Cognitive impairment is defined as difficulties with thinking processes that can impact various cognitive domains, including memory, attention, processing speed, language, visuospatial, and executive functions (e.g., multitasking, judgment, problem solving). In patients with Long COVID, cognitive impairment has been characterized primarily by deficits in executive functioning (Becker et al., 2023). Cognitive impairment associated with Long COVID can vary in severity, from mild to severe, and often has an impact on instrumental activities of daily living.

Studies have reported varied rates of PCCI ranging from 8 to 80 percent (Becker et al., 2021), likely the result of varying measurement of cognition, including self-reported versus objective neuropsychological measures; use of cognitive screeners (which are insensitive to milder forms of impairment) (Lynch et al., 2022); and telephonic or online administration of measures versus validated, in-person assessments. However, the most robust studies have found PCCI to occur in approximately 24 percent of patients post COVID-19, across the spectrum of acute COVID severity (Becker et al., 2021). These cognitive deficits have been found to persist several months following SARS-CoV-2 infection (Becker et al., 2021, 2023), with some studies reporting long-term persistence beyond 1 year (Cavaco et al., 2023). While the severity of PCCI is relatively mild in comparison to the deficits

seen in neurodegenerative diseases and severe traumatic brain injuries, it can still contribute to significant functional disability in those impacted (Delgado-Alonso et al., 2022).

PCCI can occur regardless of age, preexisting comorbidities, vaccination status, and COVID-19 variant. However, vulnerability to the condition appears to be greater in Black, Hispanic, female, and older-aged populations (Jacobs et al., 2023; Valdes et al., 2022), a finding that has substantial implications for occupational and social functioning. Female sex has also been associated with a greater probability of PCCI (Jacobs et al., 2023; Valdes et al., 2022). Differences have been found among racial and ethnic groups, such that Black and Hispanic individuals may be more likely to experience Long COVID and PCCI compared with non-Hispanic White individuals (Jacobs et al., 2023). Fewer years of education, Black race, and unemployment with baseline disability have likewise been found to confer a greater risk of PCCI (Valdes et al., 2022). Finally, preexisting conditions, including headaches (Jacobs et al., 2023), cognitive impairment (Valdes et al., 2022), neurological disease (Hartung et al., 2022), and renal disease (Bucholc et al., 2022), all appear to confer greater risk of PCCI. Conversely, some data suggest that the COVID-19 vaccine may reduce the risk of PCCI (Gao et al., 2022).

While the term “brain fog” has been deemed synonymous with cognitive impairment in the Long COVID literature, the two may be distinct clinical entities (McWhirter et al., 2023; Orfei et al., 2022). Brain fog is not a recognized medical diagnosis in itself, but rather a debilitating symptom that is usually seen in association with other factors, such as fatigue, psychosocial stress, and both physical and mental conditions (Jennings et al., 2022). Brain fog seen in patients following SARS-CoV-2 infection has anecdotally been described as inattention, forgetfulness, difficulty concentrating, and difficulty finding words (McWhirter et al., 2023). While these difficulties are often observed in formal neuropsychological assessments, it is well known that patients’ subjective cognitive reports may sometimes be discrepant with objective neuropsychological findings (Schild et al., 2023). Nevertheless, it is important to note that individuals with cognitive impairment may report brain fog as a symptom, and that brain fog and PCCI may be equally functionally disabling in patients with Long COVID.

Diagnosis

The prevalence of cognitive impairment, including mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and more severe forms of cognitive impairment (e.g., dementia), increases with age. It is generally uncommon (i.e., less than 3 percent of the population) before age 65 and increases dramatically

after age 75 (Casagrande et al., 2022; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2020). The prevalence of MCI can be difficult to estimate due to several factors. There are varying diagnostic criteria for MCI. Additionally, as the population ages, some cases of MCI return to normal cognition with ongoing follow-up while others progress to dementia (Casagrande et al., 2022; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2020). In addition to a comprehensive medical history, the clinical standard for diagnosis of cognitive impairment includes a comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation consisting of standardized tests that have well-established normative data (Becker et al., 2023; Casaletto and Heaton, 2017). These tests allow a clinician to compare an individual’s scores with those of a normative population, adjusted for age; education; and sometimes other factors, such as sex. An individual’s performance on these tests is often categorized according to standard deviations (SDs) below the mean of the normative sample. Scores within 1 SD below the mean are considered “average,” whereas scores between 1 and 1.5 SDs below the mean are considered “mildly impaired” or “below average,” and those more than 2 SDs below the mean are considered “moderately to severely impaired.” A neuropsychological evaluation often tests all cognitive domains, including attention, working memory, processing speed, executive functions, language, visuospatial abilities, and learning and memory (Becker et al., 2023).

Many clinical challenges are involved in the evaluation and diagnosis of individuals with PCCI. As noted above, some individuals with Long COVID may report brain fog or other cognitive concerns and experience functional impairment, while not necessarily meeting the clinical diagnostic threshold for cognitive impairment (Davis et al., 2023). This may occur for several reasons.

First, most neuropsychological measures were developed to assess individuals with neurodegenerative disorders or traumatic brain injury (Casaletto and Heaton, 2017; Harvey, 2012) and may not adequately capture the often subtle impairment that can result from COVID-19. Similarly, many caveats apply to the normative data with respect to the populations that are considered “normal,” as norms may not always account adequately for such factors as education, cultural background, language proficiency, and other individual differences.

Second, the theory of cognitive reserve posits that individual differences in the ability to cope with brain pathology or damage are influenced by the brain’s resilience and adaptability, which is often related to such factors as educational attainment, occupational complexity, lifelong learning and stimulation, and social engagement (Stern et al., 2019). Individuals with a high cognitive reserve may not immediately show

impairment on neuropsychological tests for several reasons: (1) they may be adept at using alternative cognitive strategies or recruiting additional brain resources to compensate for those areas that are impaired; (2) they may have started with a higher baseline of cognitive abilities, and thus will still score within the “normal” range on tests even if they have experienced some decline; and (3) their brain may be better able to cope with or resist damage because of its adaptability (Stern et al., 2019). At the same time, however, by the time these individuals’ cognitive symptoms become apparent or manifest on neuropsychological tests, the underlying brain pathology may be quite advanced. In some cases, individuals with high cognitive reserve may report subjective cognitive decline; they feel that their cognitive abilities have diminished even if they still score well on formal testing. This subjective feeling may be attributable to patients’ awareness of subtle changes or difficulties that are not yet detectable with standardized tests, a phenomenon that may be consistent with the concept of brain fog. This phenomenon underscores the importance of considering a comprehensive clinical picture, including subjective reports, daily functioning, and other factors, in conjunction with neuropsychological test scores. Without prior neuropsychological testing, it can be challenging to determine the degree of decline or change from an individual’s baseline cognitive abilities, especially if those baseline abilities were above-average.

Third, performance validity can sometimes be an issue in the clinical evaluation of PCCI. That is, an individual’s performance on neuropsychological tests can be influenced by various factors unrelated to PCCI, such as anxiety, depression, fatigue, or even the specific circumstances of the testing day. Such conditions as sleep disorders or chronic pain, medications, or other medical issues can influence cognitive performance and may lead to inconsistent test results, complicating their interpretation. In some cases, an individual’s effort on a test may be called into question; that is, some individuals may have difficulty fully engaging with the evaluation, usually because of psychological or situational factors. It is also possible that individuals may purposely underperform (e.g., for secondary gain, such as disability claims). Fortunately, neuropsychologists have performance validity measures that can detect suboptimal effort.

Finally, it is important to note that other conditions can mimic the symptoms of PCCI. For example, depression may increase one’s perception of brain fog and contribute to poor attention and concentration (Cristillo et al., 2022). Identifying whether cognitive deficits are due to PCCI or other factors can therefore be challenging. For this reason, a thorough medical history can be extremely useful in ruling in or out other potentially contributing factors.

Functional Impacts

Quantifying the functional impacts of PCCI involves integrating a comprehensive medical history, results of objective neuropsychological tests, subjective symptom reports, and real-world observations. A neuropsychological evaluation can help in identifying specific areas of cognitive strength and weakness and in predicting where an individual may have the most difficulty from day to day.

Several instruments (e.g., Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scale) can be used to gauge how PCCI may be impacting daily tasks, such as managing finances, following instructions, or planning activities. Other self-report tools can help capture individuals’ perceptions of their cognitive and functional challenges. For example, numerous self-report instruments have been shown to adequately capture the severity and functional impact of symptoms associated with self-reported brain fog, such as the Neuro-QOL Scale (Shirley Ryan AbilityLab, 2019), the Cogstate (Maruff et al., 2009), or the Everyday Cognition scale (ECog) (Farias et al., 2008). Feedback from family members, coworkers, or educators can also provide a comprehensive view of an individual’s functioning by offering insight into observed challenges in task completion, time management, or problem solving in real-world settings. Similarly, review of work performance evaluations or school assessments can be helpful in delineating where an individual may be struggling. Especially in complex cases, a neuropsychologist may work closely with other professionals (e.g., occupational therapists, speech therapists, educators, vocational counselors) to provide a holistic understanding of the individual’s functional challenges.

Selected Populations

Research on PCCI in selected populations is limited. As described above, several studies have found racial and ethnic differences in the incidence of PCCI, whereby minoritized populations may be disproportionately impacted (Jacobs et al., 2023). While a neuropsychological evaluation can be extremely valuable in quantifying PCCI and its functional impact, it may not always be accessible to all individuals, and there are many barriers to care. First, because of high demand and a limited number of trained neuropsychologists, there can be extended wait times for an evaluation. Second, many neuropsychologists practice in urban areas or academic medical centers. Therefore, people living in rural or remote areas may not have easy access to a neuropsychologist and may have to travel significant distances for an evaluation. Third, neuropsychological assessments can be costly, and not all insurance plans cover them adequately; individuals without insurance may not be able to afford the evaluation. Finally, in certain cultures

or communities, stigma may be associated with seeking psychological or neuropsychological services, preventing some individuals from pursuing an evaluation.

In addition, certain populations may not derive the same benefit from an evaluation. Several cultural nuances come into play here. First, individuals who speak languages other than English and those whose cultural background differs from that of the majority U.S. population may not have access to appropriate and culturally sensitive evaluations or even to neuropsychologists or interpreters with whom they can communicate, which can lead to misinterpretation of results. Second, most neuropsychological tests were developed and standardized on English-speaking populations, and appropriate normative data may not be available for the individual in question. In this case, an individual’s performance can be over- or underestimated. Finally, in some cultures, cognitive challenges may be expressed more in somatic or physical terms, which can affect self-report measures, clinical interviews, and even effort on the neuropsychological tests. Thus, data derived from neuropsychological evaluations in such populations must often be interpreted with some caution.

Autonomic Dysfunction

Orthostatic intolerance and autonomic dysfunction have emerged as a distinct symptom cluster in Long COVID (El-Rhermoul et al., 2023). Autonomic dysfunction is any disturbance of the autonomic nervous system, inclusive of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS). POTS has increasingly been observed in patients following SARS-CoV-2 infection (Amekran et al., 2022). Other, less frequent types of autonomic dysfunction observed in patients with Long COVID include neurocardiogenic syncope (NCS) and orthostatic hypotension (OH) (Blitshteyn and Whitelaw, 2021). When objective tests do not confirm an established autonomic disorder (i.e., POTS, NCS, or OH), but autonomic symptoms arise upon assuming an upright posture and are relieved by being supine, then the diagnosis of orthostatic intolerance can be given. Some symptoms of autonomic dysfunction, such as lightheadedness, improve quickly upon lying down, but other symptoms, such as fatigue and brain fog, can persist for hours or days at a time and can impact activities of daily living (Fedorowski, 2019; Vernino et al., 2021).

Although POTS is itself a diagnosable multisystem disorder, it also has emerged as a distinct phenotype of Long COVID (El-Rhermoul et al., 2023). POTS is characterized by a sustained heart rate of 30 beats per minute or more in the absence of orthostatic hypotension (Amekran et al., 2022). Like Long COVID, POTS is a multisystem disorder; common symptoms include

fatigue, nausea, dizziness, palpitations, chest pain, and exercise intolerance. POTS, and autonomic dysfunction generally, often present secondary to viral infections. Some studies have suggested that POTS could contribute to the pathophysiology of Long COVID, explaining the persistence of symptoms such as fatigue and cognitive issues in Long COVID patients, although the evidence for this hypothesis is limited (Amekran et al., 2022; Barizien et al., 2021; El-Rhermoul et al., 2023; Isaac et al., 2023). Mechanisms of action may include direct tissue damage, immune dysregulation, hormonal disturbances, elevated cytokine levels, and persistent low-grade infection (Carmona-Torre et al., 2022). Autonomic dysfunction appears to play a significant role in Long COVID and its potential neurological complications (Buoite Stella et al., 2022; Diekman and Chung, 2023).

The prevalence of POTS in the general U.S. population varies, with estimates ranging from 0.1 to 1 percent and a higher incidence among females, although in the general population is likely significantly under-diagnosed (Arnold et al., 2018; Bhatia et al., 2016; Shaw et al., 2019). POTS occurs most frequently in females aged 12–50 and is less common in young children (Amekran et al., 2022). Among people with Long COVID, one study reports 4.1 percent of respondents had received a diagnosis of POTS by the time of the survey, and 33.9 percent of those who reported tachycardia had symptoms suggestive of POTS (Davis et al., 2021). Another study reported 12 percent of individuals with Long COVID who underwent standard autonomic testing had results consistent with POTS (Bryarly et al., 2022). Studies indicate that 25–66 percent of Long COVID patients report autonomic dysfunction (Ladlow et al., 2022; Larsen et al., 2022). One study found orthostatic hypotension in 14 percent of subjects with Long COVID symptoms (Buoite Stella et al., 2022). Kavi (2022) cites unpublished data indicating that Long COVID clinics report 15–50 percent of patients having postural symptoms. These numbers should be taken as preliminary estimates given that most of the data to date came from small retrospective studies that vary in timing after initial SARS-COV-2 infection, definitions of POTS and autonomic dysfunction, and testing protocols.

Diagnosis

The diagnostic criteria for POTS are

- a sustained increase in heart rate upon assuming an upright position of ≥30 beats per minute in adults or ≥40 beats per minute in adolescents aged 12–19,

- the presence of chronic symptoms of orthostatic intolerance for at least 3 months, and

- the absence of orthostatic hypotension (Kavi, 2022; Raj et al., 2021, 2022).

In addition to a detailed medical history and physical examination, evaluating for orthostatic intolerance includes autonomic function tests and questionnaires. Autoantibody testing can provide supporting evidence.

Two forms of standing tests are used to diagnose POTS in Long COVID patients. These tests assess heart rate and blood pressure changes upon assuming an upright position, providing insight into autonomic dysfunction and orthostatic intolerance. In the active stand test, patients rest supine for 5 minutes, then immediately stand up, and their blood pressure and heart rate are measured at 2, 5, and 10 minutes. This test captures the immediate response to standing and helps identify orthostatic tachycardia and associated symptoms (Espinosa-Gonzalez et al., 2023). Another potentially useful test is the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA’s) lean test, which involves the patient leaning against a wall after resting supine, with blood pressure and heart rate measured every minute for 10 minutes. This posture minimizes the impact of skeletal muscle pump effects on the cardiovascular system (Espinosa-Gonzalez et al., 2023; Kavi, 2022). These standing tests can be conducted in the primary care setting and may provide valuable information for diagnosing POTS without the need for specialist consultation or specialized equipment (Kavi, 2022).

The head-up tilt test is a specialized assessment used in secondary or tertiary health care settings to investigate autonomic dysfunction (Espinosa-Gonzalez et al., 2023). Head-up tilt table testing is usually performed with a motorized table with a foot board for weight bearing (Benditt et al., 1996). The patient lies supine, loosely restrained by safety straps to prevent injury if loss of consciousness occurs. After a variable period of supine rest, usually 15 minutes but in some studies up to 60 minutes, the tilt table is brought upright, usually to 60–70 degrees. This test, designed to explore the underlying causes of loss of consciousness, is the accepted method for investigating fainting in controlled laboratory conditions. During the test, the patient is positioned on a table equipped with motorized tilting capability. Blood pressure and heart rate measurements are taken while the patient is in a supine position and then gradually tilted upward to approximately 60 degrees for a duration of up to 45 minutes (Espinosa-Gonzalez et al., 2023). If syncope or presyncope occurs, the patient is promptly returned to the supine position. While this specialized test is not essential for a straightforward diagnosis of orthostatic tachycardia, it is useful in investigating specific symptoms, such as unexplained syncope. Not all individuals with orthostatic symptoms require head-up tilt testing.

COMPASS-31 is a standardized, easy-to-complete autonomic questionnaire used to screen for autonomic dysfunction and track symptom changes over time (Larsen et al., 2022). Questions fall into one of six domains: orthostatic intolerance, vasomotor, secretomotor, gastrointestinal, bladder, and pupillomotor function. The questionnaire generates a weighted score from 0 to 100, with a score of ≥20 suggesting moderate to severe autonomic

dysfunction (Larsen et al., 2022). COMPASS-31 is frequently used to assess symptoms of autonomic dysfunction in Long COVID research (Bryarly et al., 2022; Buoite Stella et al., 2022; Seeley et al., 2023). Individuals with Long COVID could benefit from screening for symptoms of autonomic dysfunction (e.g., through use of the COMPASS-31 questionnaire), and those experiencing symptoms of orthostatic intolerance would benefit from further evaluation for disorders such as POTS or orthostatic hypotension (Larsen, Stiles, and Miglis, 2021).

Autoantibody testing can provide supporting evidence for diagnosis, although it is currently not particularly sensitive or specific (Carmona-Torre et al., 2022). A feature of POTS following SARS-CoV-2 infection is a high prevalence of specific circulating autoantibodies, including G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) antibodies (such as adrenergic, muscarinic, and angiotensin II type-1 receptors) and the ganglionic neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (g-AChR). Other recognized autoantibodies in POTS include circulating antinuclear, antithyroid, anti-NMDA-type glutamate receptor, anticardiac protein, anti-phospholipid, and Sjögren’s antibodies (Carmona-Torre et al., 2022).

Functional Impacts

Symptoms resulting from autonomic dysfunction following SARS-CoV-2 infection have a substantial impact on individuals’ functioning and quality of life in the short, medium, and long terms (Carmona-Torre et al., 2022). Symptoms are associated with loss of school and work participation, especially in young women (Bourne et al., 2021). In a study involving 20 adult Long COVID patients (70 percent female), residual autonomic symptoms persisted in 85 percent of participants 6–8 months after SARS-CoV-2 infection, with 60 percent being unable to return to work (Blitshteyn and Whitelaw, 2021). Haloot and colleagues (2022) investigated a sample of 40 Long COVID patients who were diagnosed with POTS and found that disabling symptoms persisted in 100 percent of previously high-functioning participants even after 6 months, indicating the enduring impact of the condition. McDonald and colleagues (2014) assert that young adults with POTS experience a degree of functional impairment comparable to that reported in congestive heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, leading to a notably low quality of life. A prospective study of 99 participants—including those with post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) (another term used for Long COVID), those with POTS, and healthy controls—revealed a high burden of autonomic dysfunction in those with PASC, leading to poor health-related quality of life and high health disutility (Seeley et al., 2023).

Approximately 50 percent of patients with POTS recover within 1–3 years, with lifestyle measures aiding recovery (Fedorowski, 2019). Exercise therapy, including rowing or cycling, has been shown to be effective in improving functioning in individuals with POTS following COVID-19. A minimum of 3 months of exercise therapy has been recommended, and symptoms often worsen before improving (Fu and Levine, 2018; Shibata et al., 2012). The course of recovery for symptoms associated with autonomic dysfunction in Long COVID entails remitting and relapsing as a result of various factors, such as comorbid conditions, stress, and overexertion (Barizien et al., 2021; Seeley et al., 2023); therefore exercise therapy must be individualized and closely monitored.

Assessing the ability to work in individuals experiencing orthostatic intolerance is challenging because of the unpredictable postexertional increase in symptoms for several days after prolonged periods of upright posture. This intolerance can significantly contribute to disability, and the ability to quantify the extent of functional impairments is limited. Self-reported symptom severity is critical in evaluating disability in individuals dealing with both orthostatic intolerance and Long COVID.

Overall functioning in chronic illnesses is often assessed in adults through self-report health-related quality of life questionnaires, such as the 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36), the EuroQOL, or the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) questionnaires (Cook et al., 2012; EuroQol Group, 1990; Ware and Sherbourne, 1992). A newly developed self-report questionnaire, the Malmö POTS symptom score, has shown promise for assessing symptom burden and measuring disease progression in adults with POTS (Spahic et al., 2023). For pediatric patients, age-specific instruments, such as the Functional Disability Inventory or Pediatric Quality of Life (PedsQL), are used into young adulthood, effectively distinguishing between healthy and chronically ill individuals (Claar and Walker, 2006; Varni et al., 2001; Walker and Greene, 1991). Self-reported measures of general or cognitive fatigue include the PedsQL, the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI), the Wood Mental Fatigue Inventory, the Fatigue Severity Scale, and others (Bentall et al., 1993; Krupp et al., 1989; Varni and Limbers, 2008; Wood et al., 1991).

Selected Populations

Research on Long COVID-associated POTS in selected populations is limited. In a recent study of pregnant women with POTS not specific to Long COVID (8,941 female patients, 40 percent pregnant), the authors found that the severity of pregnancy symptoms in the first trimester could predict the severity of symptoms in the second and third trimesters

(Bourne et al., 2023). If symptoms improved in the first trimester, they were more likely to continue to improve in the later trimesters, while if symptoms worsened in the first trimester, they were likely to continue to worsen in the second and third trimesters. Other selected populations that may experience autonomic dysfunction from Long COVID and thus require health equity considerations include people with certain conditions and/or disabilities, racial and ethnic minorities, people diagnosed as overweight or obese, and uninsured or underinsured individuals. One example of clinical considerations regarding health equity is those with impaired mobility or severe orthostatic intolerance. Some of these patients may be unable to perform standard testing for autonomic dysfunction, such as a 10-minute stand test, requiring testing modifications (Blitshteyn et al., 2022).

HEALTH EFFECTS OF LONG COVID IN CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS

While there are various definitions of children, adolescents, and young people, for the purposes of this report “children” or “pediatrics” will refer to the entire pediatric age range and “adolescents” to children in the older end of the spectrum (i.e., ages ~11 to 18 years). Although rates vary by age, children infected with SARS-CoV-2 usually have mild disease (COVID-19) with low rates of hospitalization (<2 percent) or death (<0.01 percent) (Bhopal et al., 2020, 2021). Nonetheless, persistent health effects following SARS-CoV-2 infection have been reported in children, with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) and Long COVID being commonly reported (Lopez-Leon et al., 2022). Additionally, Kompaniyets and colleagues (2022) found selected health effects for which children with SARS-CoV-2 infection are at increased risk: pulmonary embolism (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 2.01), myocarditis and cardiomyopathy (aHR 1.99), venous thromboembolic events (aHR 1.87), acute and unspecified renal failure (aHR 1.32), type 1 diabetes mellitus (aHR 1.23), coagulation and hemorrhagic disorders (aHR 1.18), smell and taste disturbances (aHR 1.17), type 2 diabetes (aHR 1.17), and cardiac dysrhythmias (aHR 1.16). Vaccination has been shown to reduce the risk of infection and protect against COVID-19–associated illness, including MIS-C, in children (Fowlkes et al., 2022; Tannis et al., 2023; Yousaf et al., 2023; Zambrano et al., 2022), although the majority of children in the United States remain unvaccinated against COVID-19 (AAP, 2023; CDC, 2021a; Zambrano et al., 2024).

Among the long-term health effects of COVID-19, type 1 diabetes has garnered specific attention, showing a higher incidence rate among children in the first year of the pandemic compared with a prepandemic period

(incidence rate ratio [IRR], 1.14; 95% CI, 1.08–1.21) (D’Souza et al., 2023). This finding was mirrored in the months 13–24 of the pandemic, as shown in a meta-analysis (IRR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.18–1.37) (D’Souza et al., 2023). The increased risk of type 1 diabetes in children after SARS-CoV-2 infection was found even when compared with diagnosis of acute respiratory infection unrelated to COVID-19 (Barrett et al., 2022; Rahmati et al., 2023; D’Souza et al., 2023). Additional studies are needed to further delineate this phenomenon.

MIS-C presents within 2–6 weeks of acute SARSs-CoV-2 infection as a systemic inflammatory illness. Criteria for case definition include severity necessitating hospitalization, fever above 100.4 degrees Fahrenheit, laboratory evidence of systemic inflammation, and multisystemic organ involvement that cannot be explained by another diagnosis (CDC, 2023a). Organ systems affected by MIS-C include gastrointestinal (80–90 percent), mucocutaneous (74–83 percent), cardiovascular (66.7–86.5 percent), hematologic (47.5 percent), respiratory (36.5 percent), and neurologic (12.2 percent) (Blatz and Randolph, 2022). Reassuringly, with MIS-C–directed treatment, the mortality rate has been 1–2 percent (Blatz and Randolph, 2022; Feldstein et al., 2021).

Although children with MIS-C present as critically ill, most inflammatory and cardiac manifestations resolve rapidly (Rao et al., 2022; Penner et al., 2021). However, some children do experience more long-lasting effects (Penner et al., 2021). One study tested children 6 months after hospitalization on the 6-minute-walk test and found that 45 percent of the patients scored below the 3rd percentile for age, demonstrating functional impairment (Penner et al., 2021). In this same study, 98 percent of the children were able to return to full-time education, but formal neuropsychological testing was not conducted to assess school performance (Penner et al., 2021). More research is needed to characterize the potential long-term effects of MIS-C.

Pediatric Long COVID is a separate entity from MIS-C. The true prevalence of Long COVID symptoms and health effects remains unclear for multiple reasons and varies widely in the literature, including limited studies and heterogeneous samples (Pellegrino et al., 2022). However, rates of pediatric Long COVID are lower than the rates of adult Long COVID (Behnood et al., 2022; CDC, 2023b; Jiang et al., 2023; Rao et al., 2022; Zheng et al., 2023). The risk of Long COVID may be associated with severe symptoms during initial infection, hospitalization, the number of organ systems involved, the number of symptoms at presentation, lack of vaccination against COVID-19, medical complexity, and body mass index ≥85th percentile for age and sex (Bygdell et al., 2023; Funk et al., 2022; Rao et al., 2022). Children with MIS-C may also develop Long COVID (Maddux et al., 2022).

Children with Long COVID may have health effects across body systems (Table 3-2). Commonly reported symptoms include fatigue (sometimes with PEM), weakness, headache, sleep disturbance, muscle and joint pain, respiratory problems, palpitations, altered sense of smell or taste, dizziness, and autonomic dysfunction (Morrow et al., 2022; Rao et al., 2022). Guidelines specific to pediatric Long COVID can aid in the diagnosis and management of the condition in children (Malone et al., 2022).

A systematic review of 22 studies (n = 23,141) from 12 countries identified fatigue (47 percent) as the most dominant Long COVID symptom in children and young people (age ≤ 19 years old), followed by headache (35 percent) (Behnood et al., 2022); these findings are consistent with those of several adult studies (Cheung et al., 2023; Líška et al., 2022; Sánchez-García et al., 2023; Štěpánek et al., 2023). In another systematic review and meta-analysis of 21 pediatric studies (n = 80,071), the prevalence of Long COVID was reported as 25.24 percent, with fatigue (9.66 percent) being the second most dominant clinical manifestation, behind mood symptoms (16.50 percent). Sleep disorders (8.42 percent), headache (7.84 percent), and respiratory symptoms (7.62 percent) were among the top-ranked Long COVID manifestations (Lopez-Leon et al., 2022). It is important to note that for this systematic review and meta-analysis, Long COVID criteria included symptoms lasting for at least 4 weeks, which likely contributed to the higher reported prevalence compared with findings of other studies. Studies have shown that isolation, increased stress, and loss of parents and caregivers significantly impacted children’s development during the pandemic and may lead to a future rise in mental illnesses (Lopez-Leon et al., 2022) and other Long COVID sequelae.

Fatigue and PEM present similarly in pediatric populations compared to adults and are common in children with Long COVID; however, data from pediatric populations with ME/CFS indicate better long-term recovery compared with adults (Carruthers et al., 2011). In a cohort observational study of nearly 800 children, ME/CFS had a mean duration of 5 years, with 54 percent of patients reporting recovery between 5–10 years, and 68 percent of patients reporting recovery after more than 10 years (Rowe, 2019); this issue has not been explicitly studied in children with Long COVID.

POTS and other forms of autonomic dysfunction have also been reported in children with Long COVID (Morrow et al., 2022). Presentations and symptomatology, including orthostatic dizziness, palpitations, chest pain, diaphoresis, and nausea, are similar to those in adults. However, the diagnostic criteria for POTS are different in children and in adults: for individuals aged 12–19, the required heart rate increment is an increase of at least 40 beats/minute on a standing tolerance test, compared with 30 beats/minute in adults (Morrow et al., 2022; Vernino et al., 2021). One study compared 29 adolescents with Long COVID who developed

TABLE 3-2 Common Long COVID Symptoms in Children and Adolescents by Body System

| Respiratory | Shortness of breath or dyspnea |

| Chest (thoracic) pain or tightness | |

| Cough | |

| Difficulty with activity/exercise intolerance | |

| Cardiovascular | Palpitations or tachycardia |

| Dizziness/lightheadedness | |

| Syncope | |

| Chest pain | |

| Difficulty with activity/exercise intolerance | |

| Neurological | Headache |

| Dizziness/lightheadedness or vertigo | |

| Orthostatic intolerance | |

| Syncope or presyncope | |

| Tremulousness | |

| Paresthesia or numbness | |

| Difficulty with attention/concentration | |

| Difficulty with memory | |

| Cognitive impairment or brain fog | |

| Special Senses | Abnormal or loss of smell or taste |

| Musculoskeletal | Weakness |

| Muscle, bone, or joint pain | |

| Gastrointestinal | Nausea |

| Vomiting/reflux | |

| Abdominal pain | |

| Bowel irregularities (constipation/diarrhea) | |

| Weight loss | |

| Lack of appetite | |

| Mental Health | Anxiety |

| Depression/low mood | |

| Increased somatic symptoms | |

| School avoidance | |

| Regression of academic or social milestones | |

| No specific organ system | Fatigue (general); Post-exertional malaise |

| Exercise intolerance | |

| Sleep disturbances | |

| Fever |

SOURCES: Behnood et al., 2022; Borch et al., 2022; Drogalis-Kim et al., 2022; Funk et al., 2022; Jiang et al., 2023; Kompaniyets et al., 2022; Kostev et al., 2022; Leftin Dobkin et al., 2021; Lopez-Leon et al., 2022; Malone et al., 2022; Mariani et al., 2023; Morrow et al., 2022; Pellegrino et al., 2022; Radtke et al., 2021; Riera-Canales and Llanos-Chea, 2023; Roessler et al., 2022; Sansone et al., 2023.

an inappropriate sinus tachycardia or POTS with 64 adolescents who developed autonomic dysfunction prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. The authors concluded that, at least with regard to heart-rate variability, adolescents with POTS diagnosed following SARS-CoV-2 infection were not significantly different from the prepandemic controls (Buchhorn, 2023). Management of POTS is similar for children and for adults, with lifestyle interventions and physical therapy protocols being first line, augmented by medications when indicated.

Post–COVID-19 cognitive impairment (PCCI) or brain fog is reported in children with Long COVID and may manifest in behavioral changes and declining school performance. Limited research has focused on the chronic cognitive effects of COVID-19 in children. Objective neuropsychological data in pediatric patients have shown increased attention deficits in these patients and elevated mood/anxiety concerns (Luedke et al., 2024; Morrow et al., 2021; Ng et al., 2022; Tarantino et al., 2022), although these data came from small, single-center studies. In a survey of 510 children with ages ranging from 1–18 years, 61 percent had poor concentration, 46 percent had difficulty remembering information, 40 percent struggled with completing everyday tasks, and 33 percent had difficulties with information processing (Buonsenso et al., 2022). Importantly, other factors, such as fatigue and mental health problems, should be evaluated when cognitive problems are suspected, as these and other factors can contribute to poor attention and other cognitive difficulties.

With respect to management, a cognitive rehabilitation approach should be considered to improve attention regulation and help the child develop compensatory strategies. Whenever possible, support and accommodations should be offered in school settings to prevent the child from falling further behind academically. Periodic reassessment of cognitive functions is also prudent to monitor progress over time. Finally, screening for mental health problems is critical in children with post-COVID cognitive impairment, as PCCI can greatly impact quality of life.

Children with Long COVID may experience new or worsening mental health conditions, such as anxiety and depression. One study with 236 pediatric Long COVID patients found that irritability, mood changes, and anxiety or depression were found in 24.3 percent, 23.3 percent, and 13.1 percent of the cohort, respectively, suggesting a high prevalence of persistent psychiatric symptoms (Roge et al., 2021). Children may experience anxiety and depression differently from adults. Signs of depression can include behavioral problems at school, changes in eating or sleeping habits, and lack of interest in fun activities, while signs of anxiety in children can include fear of being away from a parent, physical symptoms of panic, and refusal to go to school. Diagnosis involves ruling out other conditions that may affect mood, and often includes interviews with the

child and their caregivers (Cleveland Clinic, 2023). Management of mood disorders for pediatric patients with Long COVID is the same as management for those without Long COVID (e.g., psychotherapy, medications); however, special consideration is warranted for the other comorbid Long COVID symptoms and how they may interact with mood disorders or their treatment. The most common antidepressants for children are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which increase the level of serotonin in the brain.

Although there may be overlap between pediatric and adult presentations and intervention options, particularly among adolescents, pediatric management of Long COVID entails specific considerations: developmentally, some young children and those with developmental disabilities may have difficulty describing their symptoms, and patient histories may come from parents and others outside the home, such as caregivers, coaches, or teachers. Compared with adults, children are healthier, with fewer preexisting chronic health conditions. Conditions that may increase the risk of Long COVID in adults, such as type 2 diabetes, are rarely seen in pediatrics, and Long COVID may therefore represent a large change from baseline for previously healthy children (Malone et al., 2022).

In addition to adverse effects of pediatric Long COVID on participation and performance in school, sports, and other activities (Morello et al., 2023; Pellegrino et al., 2022), it also has been shown to negatively affect family functioning as a whole (Chen et al. 2023). Management of pediatric Long COVID is focused on symptomatic support and from a functional perspective, on activities of daily living, such as participation in school and in activities and hobbies. Additionally, the American Heart Association and American Academy of Pediatrics recommend that those treating pediatric patients with moderate or severe acute SARS-CoV-2 infection or with any prolonged cardiac symptoms (e.g., fatigue, syncope, palpitations) use a screen to assess for the possibility of cardiac complications before recommending a return to physical activity (AAP, 2022a).

While the trajectory for children affected by Long COVID is more favorable than that for adults, additional studies are needed to better understand and characterize the diversity of presentations in children and long-term implications related to quality of life and function. The National Institutes of Health’s (NIH’s) RECOVER initiative currently has ongoing clinical trials and studies under way aimed at further understanding how to treat and prevent Long COVID in children in addition to adults (NIH, 2023). However, more research is still needed (Long COVID and kids: More research is urgently needed, 2022).

As detailed in Chapter 1, SSA’s definition and determination of disability in children and adolescents (<18 years) differs from those in adults. “Disability” for adults in the SSA context centers on work disability or an

inability to perform work-related activities (see, e.g., Annex Table 3-13 at the end of this chapter) and to participate in work “in an ordinary work setting, on a regular and continuing basis, and for 8 hours per day, 5 days per week, or an equivalent work schedule” (SSA, 2021). In contrast, the definition and determination of disability in children incorporates the concept of functioning more broadly (i.e., a child’s qualifying impairment(s) must cause “marked and severe functional limitations”1). When evaluating the effects of an impairment or combination of impairments on a child’s functioning, SSA considers “how appropriately, effectively, and independently” the child performs their activities (everything they do at home, at school, and in the community) “compared to the performance of other children [their] age who do not have impairments.”2 In particular, SSA considers functioning in six domains: “(i) acquiring and using information, (ii) attending and completing tasks, (iii) interacting and relating with others, (iv) moving about and manipulating objects, (v) caring for [oneself], and (vi) health and physical well-being.”3

SELECTED GUIDANCE STATEMENTS SPECIFIC TO LONG COVID

In addition to the diagnosis and management guidelines included in Annex Tables 3-1 through 3-12, selected guidance statements specific to Long COVID are listed in Table 3-3. The CDC (2024) maintains a webpage with information on Long COVID (which the CDC refers to as Post-COVID conditions) for health care providers and the general public, covering the topics of assessment and testing, management, documentation, research, and tools and resources. The latter includes a list of “medical professional organization expert opinion and consensus statements.” The World Health Organization (WHO) (2023a) also maintains a webpage on “clinical management of COVID-19,” which includes a link to the most recent version of its COVID-19 Clinical Management: Living Guidance document. This publication contains “the most up-to-date recommendations for the clinical management of people with COVID-19” and includes a section on the “care of COVID-19 patients after acute illness” (WHO, 2023a).

In the United Kingdom, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, and the Royal College of General Practitioners jointly developed a guideline addressing identification, assessment, and management of the long-term effects of COVID-19 and offering “recommendations about care in all healthcare settings for adults, children and young people who have new or ongoing

___________________

1 20 CFR 416.906.

2 20 CFR 416.926a.

3 20 CFR 416.926a.

TABLE 3-3 Selected Guidance Statements on Long COVID

| Author | Title | Last revised | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | Post-COVID conditions: Information for healthcare providers | February 6, 2024 | CDC (2024) |

| World Health Organization | Clinical management of COVID-19: Living guideline, 18 August 2023 | August 18, 2023 | WHO (2023a) |

| National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, and Royal College of General Practitioners | COVID-19 rapid guideline: Managing the long-term effects of COVID-19 | November 11, 2021 | NICE (2021a) |

| Catalan Society of Family and Community Medicine Long COVID-19 Study Group | Long Covid-19: Proposed primary care clinical guidelines for diagnosis and disease management | April 20, 2021 | Sisó-Almirall et al. (2021) |

| American Academy of Pediatrics | Post-COVID-19 conditions in children and adolescents | September 2, 2022 | AAP (2022b) |

| American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (AAPMR) PASC Multi-Disciplinary Collaborative Pediatric Work Group | Multi-disciplinary collaborative consensus guidance statement on the assessment and treatment of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC) in children and adolescents | August 11, 2022 | Malone et al. (2022) |

| AAPMR PASC Multi-Disciplinary Collaborative Writing Group | Multidisciplinary collaborative consensus guidance statement on the assessment and treatment of fatigue in postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC) patients | July 26, 2021 | Herrera et al. (2021) |

| AAPMR PASC Multi-Disciplinary Collaborative Writing Group | Multi-disciplinary collaborative consensus guidance statement on the assessment and treatment of breathing discomfort and respiratory sequelae in patients with post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC) | November 29, 2021 | Maley et al. (2022) |

| AAPMR PASC Multi-Disciplinary Collaborative Writing Group | Multi-disciplinary collaborative consensus guidance statement on the assessment and treatment of cognitive symptoms in patients with post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC) | December 1, 2021 | Fine et al. (2022) |

| Author | Title | Last revised | Source |

|---|---|---|---|