Forecasting the Ocean: The 2025–2035 Decade of Ocean Science (2025)

Chapter: Summary

Summary

Every person on Earth is affected by the condition of the ocean. The ocean is shifting in unanticipated ways and at an unprecedented pace, with changes apparent at local, regional, and global scales. The ocean provides essential resources such as food, mode of transport, energy, minerals, medicines, and opportunities for recreation, all of which contribute to U.S. economic competitiveness and well-being for individuals and communities. It protects large parts of our national borders. The ocean also plays an important role in generating hazardous conditions that impact communities near coasts, where half the world’s population resides, as well as communities farther inland.

Societal interests in the ocean—from economic activities and national security, food, recreation, and tourism—have garnered attention and support from citizens and legislators for decades. Funding for basic ocean science research through the National Science Foundation’s (NSF’s) Division of Ocean Sciences (OCE) since the 1950s has promoted U.S. world leadership in the field of ocean science and produced major scientific discoveries. For example, support from OCE has improved our ability to forecast El Niño events, providing up to 18 months’ notice to prepare for and mitigate the effects of these and other ocean processes that dramatically impact the U.S., global weather, and economies. Support from OCE led to the discovery of hydrothermal vents as well as a massive microbial community deep below the seafloor, which have granted a window into the limits of life on Earth (and contributed to development of new biotechnologies). OCE-supported research increased our understanding of which marine species (including commercially relevant fish) are sensitive to changing ocean conditions, allowing for a more focused deployment of resources to sustain vulnerable species, including new efforts to conserve, restore, and future-proof coral reefs. Moreover, OCE’s support of basic research on comb jellies led to discoveries of biomolecules that could lead to advances in neuroscience and treatments for diseases like Alzheimer’s.

At the start of this new decade (2025–2035), U.S. investment in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics in general, and the geosciences in particular, is not keeping pace with growing societal needs. For instance, policymakers need better information on how ecosystem change influences important fisheries, how greater access to the Arctic will challenge U.S. national security, and how much more heat the ocean will absorb from the atmosphere as the climate continues to warm. At the same time, other countries, including U.S. competitors, are increasing their investments in ocean science and advancing their capacities, thus challenging U.S. scientific leadership. The United States is at a critical juncture, in which major investments are needed for upgrading and replacing infrastructure to support basic and applied research. Without such investments, the United States will lose preeminence in this globally competitive endeavor.

This report provides advice to NSF on focusing its investments in ocean research, infrastructure, and workforce to meet national and global challenges in the coming decade and beyond, and in doing so, enhance national security, scientific leadership, and a thriving blue economy.

THE COMMITTEE’S TASK

NSF asked the committee for advice on a research, infrastructure, and workforce development strategy that will advance understanding of the ocean’s role in the Earth system from 2025–2035, and beyond. With the understanding that the Ocean Sciences Division at NSF (OCE) will continue to fund basic research across the ocean sciences, the committee was instructed to highlight a few research priorities for additional investment. The committee concluded that these priorities should include multi-sectoral and multi-disciplinary, use-inspired and societally-relevant components; they should provide opportunities to increase the workforce and broaden opportunities in ocean science, and these research priorities should enable new opportunities for OCE to work together with other units within NSF and with agencies and organizations outside of NSF, to address urgent questions surrounding ocean and Earth system science.

THE CHALLENGE FOR THE NEXT DECADE

Understanding and anticipating change in the ocean and how this change affects marine ecosystems and humans has never been more urgent. The committee poses the following challenge to NSF and to the broader ocean science community for the next decade: by 2035, establish a new paradigm for forecasting ocean processes at scales relevant to human well-being.1 Establishing this paradigm will require a relentless focus on furthering basic science to observe and understand ocean processes through the lens of disciplinary, as well as transdisciplinary, innovative research practices. Progress on this research will contribute to federal management and policy decisions that promote adaptation to changes in the Earth system, resiliency, national security, and prosperity in the ever-changing environment and, it will position the United States as a leader in transformative ocean science.

OCEAN SCIENCE RESEARCH PRIORITIES

To truly increase fundamental understanding of ocean processes to the point of being able to predict them in areas that are of vital importance to society, the committee recommends that investment be focused on facilitating and promoting research around three main themes and associated urgent research questions: Ocean and Climate, Ecosystem Resilience, and Extreme Events, described in the following sections.

The ocean is presently absorbing 90 percent of the heat and approximately 30 percent of the carbon that result from global emissions of greenhouse gases. Any decline in these rates of uptake would accelerate carbon dioxide (CO2) accumulation and warming in the atmosphere. In essence, the ocean has served as a buffer, absorbing much of the excess CO2 emitted since the industrial revolution and thus lessening the degree of change seen in Earth’s climate. It is unlikely that the ocean will continue this same rate of absorption, and it is possible that the patterns of ocean circulation that regulate Earth’s climate will shift. Large changes in ocean circulation will influence hurricane and storm development and movement; ice sheet stability; ocean chemistry, including acidification, nutrient speciation and cycling; and ocean productivity and ecosystem health, including major die-off events (e.g., coral bleaching). These changes could be gradual, or more sudden and dramatic, or even irreversible. Additional research will be required to forecast such changes and inform society on the anticipated conditions in the coming decades. Thus, the first urgent research question is How will the ocean’s ability to absorb heat and carbon change?

Research targeting this question is wide-ranging and could include topics such as developing new approaches to observe heat transport, improving predictions of marine ice sheet instability, and developing ways to quantify variability in the carbon cycle. Potential outcomes of this work include improved forecasts

___________________

1 Forecasting the state of the ocean at scales relevant to human well-being must occur at various temporal and spatial scales as dictated by the societal questions at hand and by the nature (e.g., rates of change, response times) of the ocean system processes.

of potential tipping points in the Earth system, the ability to predict ocean uptake of CO2 and thus assess the potential for climate mitigation strategies such as marine CO2 removal.

Fundamental changes in both the Earth and ocean’s systems are resulting in shifts to ecosystems that may negatively impact the local and global communities that depend on them. Humans could lose not only direct benefits they derive from the ocean (e.g., food and other biological products, coastal protection), but also benefits of marine ecosystems in the global earth system (e.g., carbon and nutrient cycling), which affect human health and well-being. Forecasting the resilience of marine ecosystems to these ecosystem shifts remains a significant challenge. Reducing the scientific uncertainty around ecosystem change would enhance communities’ ability to adapt and maintain functionality. Therefore, the second urgent research question is How will marine ecosystems respond to changes in the Earth system?

Examples of research directions that support this question include determining the effects of warming, acidification, and de-oxygenation on the dynamics and productivity of ocean biota, and co-developing tools for rapid measurements and assessments of ocean biological and functional diversity. Development of food web models that can predict food security, assessment of potential ecosystem effects of deep-sea mining, and design of effective area-based conservation measures are just a few of the societally relevant outcomes of such research.

While the ocean provides many benefits to society, it is also the source of devastating events such as earthquakes, tsunamis, hurricanes, storm surges, and flooding that directly impact coastal communities. In addition to these coastal hazards, increased precipitation, atmospheric rivers, and heatwaves have far-reaching impacts on coastal and inland communities. Long-term hazards, such as saltwater intrusion and land loss from sea level rise, currently threaten coastal communities and are expected to become increasingly more severe. Societal vulnerability to these extreme events can be profound, including its dependence on massive, century-scale investments such as port facilities, existing commercial fishing fleets, offshore energy infrastructure, coastal development, and national defense infrastructure. In light of this dependence on

the ocean, and the socio-economic and life-saving benefits of forecasting extreme events, improving the ability to observe, understand, and thereby forecast extreme events across spatial and temporal scales relevant to human well-being is critical. To facilitate societal adaptation in the United States and across the globe, the third urgent ocean science question is How can the ability to forecast extreme events driven by ocean and seafloor processes be improved?

Example research directions in support of this theme include integration of knowledge to improve early warning systems of geohazards, increasing ability to predict global weather extremes and apply these forecasts to inform sustainable urban planning, agricultural and forestry practices, and coastal community climate mitigation strategies. Ultimately, the research required to improve forecast of extreme events will improve the safety of communities vulnerable to extreme weather and geophysical hazards.

RECOMMENDATION 2.2: The National Science Foundation’s Division of Ocean Sciences should support basic research that addresses the goal of forecasting ocean processes at scales relevant to human well-being, with emphasis on the following themes and questions:

- Ocean and Climate: How will the ocean’s ability to absorb heat and carbon change?

- Ecosystem Resilience: How will marine ecosystems respond to changes in the Earth system?

- Extreme Events: How can the ability to forecast extreme events driven by ocean and seafloor processes be improved?

This compelling, cross-cutting research portfolio can galvanize the ocean science community to work together toward the challenge while offering opportunities to build new partnerships and increase interest in multiple aspects of oceanographic research.

WHAT WILL IT TAKE?

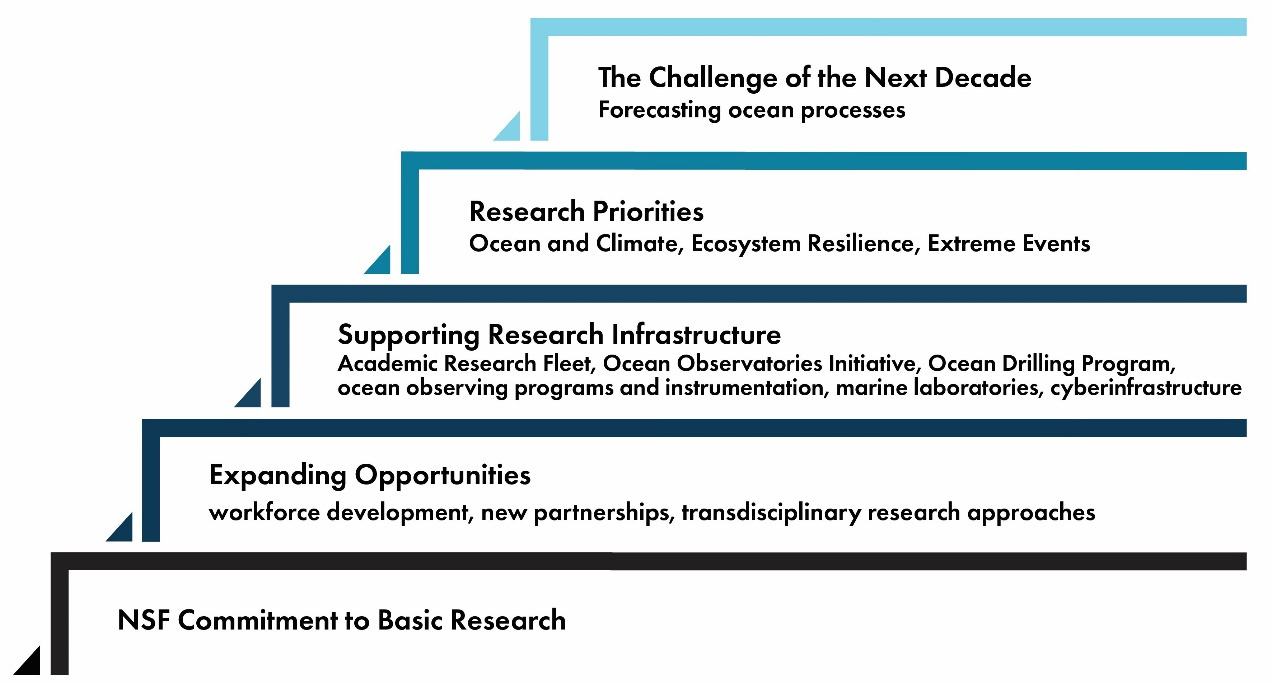

NSF is the only U.S. federal funding agency founded with the explicit mission to sponsor basic research. For the field of ocean sciences, basic research includes improving fundamental understanding of the ocean and its interactions with other parts of the Earth system. Basic research underlies progress across the range of applied and solutions-oriented work in the ocean sciences.

RECOMMENDATION 2.1: The National Science Foundation’s Division of Ocean Sciences should continue to support a broad portfolio of basic research to ensure that scientists and engineers of the future have access to a continually improved understanding of the ocean to advance and fuel innovation and resilience in the United States.

Accelerating U.S. scientific progress in understanding and forecasting ocean systems and processes will require an integrated approach that takes full advantage of emerging technologies and methods along with new resources. This includes embracing new artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques; reinvesting in ocean science infrastructure and core science research; curating vast sets of ocean data; developing novel observational technologies that fully utilize advances in robotics, environmental genomic analysis, and acoustics capabilities; and thinking creatively about how to utilize existing underwater infrastructure, such as communication cables, for research. Accelerating ocean science knowledge will also require international collaborations, U.S. public–private partnerships, thoughtful consideration of open and accessible data management, and broadening participation to ensure that all ways of knowing are incorporated. In short, the field of ocean science must transform so that research advancements are accelerated and can be applied rapidly to the urgent issues that the United States and our planet face now and in the near future. OCE continues to play a crucial role in funding these efforts (Figure S.1).

EXPANDING OPPORTUNITIES

Supporting and integrating the research needed to achieve the research priorities of the next decade require a transformation within ocean science into a field that is more collaborative, leveraging both intellectual and financial resources. To accomplish this, the committee recommends that OCE commit to expanding opportunities for science in a manner that promotes transdisciplinary research, expands the workforce, and includes new partnerships.

Transdisciplinary mindsets, skillsets, and practices—including collaboration with scientists in other disciplines, such as social sciences, and with local knowledge holders—will be key to actualizing the new paradigm of ocean science. Including multiple perspectives, among not only ocean science researchers, but also ocean science funding agencies and their directorates, will advance innovation and application of basic research. The path toward conducting successful transdisciplinary ocean science research has been partially exemplified, as evidenced by research projects in ocean acidification, marine heatwaves, and hypoxia, but it is not easily put into practice. For example, understanding ocean acidification, a chemistry problem that is deeply intertwined with the ecosystem and society, requires a shift in standard research practices to bring together differing knowledge holders to conduct research on complex interactions of multiple stressors.

In recent years, NSF has recognized the importance of supporting transdisciplinary science, as evidenced through their support of new projects such as the Cascadia Coastlines and Peoples Hazards Hub. Going forward, resource investment is needed, both fiscally and programmatically (including leadership development, management, and outcome assessments), to continue to support and incentivize building and sustaining transdisciplinary research teams in the field of ocean sciences.

RECOMMENDATION 3.1: To foster transdisciplinary research that promotes emerging solutions to challenges related to changes in ocean systems and processes, the National Science Foundation’s (NSF’s) Division of Ocean Sciences should invest in projects that utilize a participatory process toward relationship-building and collaborative efforts, establishing long-term trust and knowledge-sharing and impacting broad interests. NSF should explicitly enable research that crosses directorates and programs and intentionally facilitate efforts to dismantle barriers to transdisciplinary approaches and implementation. Potential strategies include:

- supporting projects with measurable social and environmental returns on investments, especially use-inspired and solutions-oriented research on the changing ocean;

- investing in training an expanded ocean science workforce that includes developing essential science, technology, engineering, and mathematics skills as well as transdisciplinary skills that enable meaningful connections to the humanities, social sciences, and economics;

- implementing requirements for proposals that encourage partnerships with interest holders including local communities, regional organizations, Indigenous and Tribal groups, and others, to participate in ocean research; and

- financially supporting platforms and networks that facilitate knowledge exchange between interest holders, sectors, and disciplines.

Successfully addressing ocean science research challenges in the coming decade will require the cultivation and development of an expanded ocean science workforce. The workforce will benefit not only from high-quality scientific training, but also from training in (1) collaborative science methodologies to engage with and learn from those who have differing perspectives and knowledge systems, (2) best practices for engaging in use-inspired research, (3) pathways to interacting with industry partners and interested communities, and (4) collaboratively developing and implementing research that addresses societal needs. Investing in training for transdisciplinary skills can result in a workforce prepared to succeed not only in the academic sector of ocean sciences but also more broadly in solutions-oriented science and other sectors of the U.S. economy. For example, opportunities to participate in an oceanographic research cruise, or work remotely with robotic systems, can catalyze an early-career individual to build a varied set of skills with wide application.

RECOMMENDATION 3.2: The National Science Foundation’s Division of Ocean Sciences (OCE) is uniquely positioned to shape the future of ocean sciences research and policy by cultivating a workforce that includes multiple skillsets and knowledge systems. OCE should:

- Explicitly support reskilling and upskilling, as well as mentorship, of the academic ocean science workforce to better engage with industry, entrepreneurs, interest holders, and other partners, to promote leadership development in seagoing technologies, data management, cultural competencies, and educational and mentoring practices.

- Support workforce development by investing in vocational and academic pathways, such as offering scholarships and apprenticeships; establishing fellowships with thoughtful considerations of metrics that support underserved student and professional populations, including students, researchers, or interest holders in the locations where the research is being conducted; and funding and incentivizing collaborative projects that bring together researchers from varied geographic and disciplinary backgrounds.

- Promote safe working environments by enforcing and incentivizing policies that protect people from discrimination, harassment, and bullying.

Partnerships with other sectors can reduce the expense of working in the ocean. New, creative partnerships could engage multiple sectors and foster a broader, more collaborative approach to ocean and Earth science. Development of strategic partnerships will be both necessary and critical to accomplishing the ambitious and urgent research portfolio put forward, specifically in the area of ocean observing (including platforms, data, and technology development) across ocean physics, chemistry, biology, and geology. Partnerships will also promote opportunities to engage with knowledge systems and communities across different disciplines and sectors with interests in the health of the ocean.

RECOMMENDATION 3.3: To bolster and leverage urgent ocean science research over the next decade, National Science Foundation’s (NSF’s) Division of Ocean Sciences (OCE) should explore various ways of bringing new resources to this work, including expanding partnership

with other NSF directorates, related mission agencies, industry, and other organizations. OCE should seek greater interagency cooperation through federal policies and mechanisms for leveraging NSF-funded basic ocean science research with those mission agencies. Developing new partnerships in ocean sciences, as well as other disciplines, may increase support available for the development of new technologies, data curation, solutions-oriented research, and the basic research that will fuel these developments.

Supporting Research Infrastructure

Regaining U.S. leadership in ocean science will depend on physical infrastructure for observing and studying the ocean to answer the questions of the next decade. The committee recommends continued funding for core OCE-supported infrastructure in support of the three research priorities, as well as investment in new and emerging observational technologies and cyberinfrastructure. The importance of investment in new and improved technologies for ocean observing and computing cannot be overstressed.

Academic Research Fleet

The Academic Research Fleet (ARF), including the National Deep Submergence Facility (NDSF), remains a vital part of collecting oceanographic data at sea and is required infrastructure for basic ocean science research and for research related to the urgent ocean science priorities described in this report. The ARF also plays an important role in ocean science workforce development by providing support for early-career training onboard vessels.

In the coming decade, research vessel capacity will be significantly reduced, owing to the end-of-life of multiple research vessels across the intermediate, global, and local classes. The overall estimated losses in ship time will be partly mitigated when the new NSF-owned regional-class research vessels come online. However, they are not replacements for the global-class vessels that can operate for longer periods at sea, operate in more challenging sea states, and carry a heavier load of instrumentation than smaller vessels. As several ships near their end-of-life, replacements with comparable or better capabilities are necessary to accomplish high priority science. Without replacing the global-class vessels, U.S. leadership in ocean science will be vastly diminished.

RECOMMENDATION 4.1: The National Science Foundation’s (NSF’s) Division of Ocean Sciences and appropriate partners should conduct an evaluation that details the funding allocation for the Academic Research Fleet in order to make informed distributions of the limited resources available over the next decade and beyond. The evaluation should consider metrics such as days of use funded by NSF; use of local vessels for NSF-funded research; geographic distribution of assets; and alternative mechanisms for providing researchers with access to the coasts (including salt marshes) and sea, such as through marine laboratories or new partnerships.

The long-term status of global-class research vessels is concerning; the committee urges interested parties to initiate and/or continue significant and intentional planning for replacements. Without such planning and subsequent implementation, accomplishing high-priority basic and solutions-oriented science will be compromised, and U.S. leadership in providing access to the ocean will be curtailed.

Ocean Observatories Initiative

NSF’s Ocean Observatories Initiative (OOI) has seen many successes over the past decade and as it stands, would partially support the urgent research questions for the next decade such as forecasting extreme events and providing data critical to forecasting changes in circulation, carbon and heat transfer, and understanding changes to fisheries and marine ecosystems. However, OOI was not designed to align with

specific science needs and would benefit from a revisioning and restructuring exercise that takes into consideration the current and future needs of the ocean science community broadly and how best to meet those needs.

RECOMMENDATION 4.2: The National Science Foundation’s Division of Ocean Sciences should conduct a revisioning and restructuring exercise for the future of the Ocean Observatories Initiative (OOI). The review, which should occur as a fully separate activity from the usual renewal/recompete discussions, could include:

- an analysis of the scientific contributions of each of the OOI arrays;

- reconsideration of the goals and objectives of the program to better address the needs of the ocean science community and align with the evolving and urgent ocean science questions for the next decade; and

- consideration of how to incorporate technology that may not have existed when OOI was originally envisioned, including innovative ways to observe and measure biological abundances and processes, such as low-cost distributed observational networks.

This recommended review differs from, and should be independent of, the renewal process that is focused on how well the infrastructure is meeting the requirements of the existing cooperative agreement. Rather, this investigative approach would provide a timely path forward for the next iteration of OOI that takes advantage of strategic partnerships, the evolution of ocean sciences and technological capabilities over the two decades since the OOI was originally conceived, and the approaches needed to address the urgent research priorities laid out in this report, as well as other science questions. This recommended review should occur well before the initiation of the review/renewal discussion regarding the current cooperative agreement.

Scientific Ocean Drilling

For nearly 60 years, scientific ocean drilling has played a pivotal role in our understanding of the Earth system, such as elucidating theories on plate tectonics and ice sheet behavior and constraining climate models. Going forward, scientific ocean drilling remains an important tool for answering the urgent science questions of the next decade around the topics of climate forecasting, carbon and heat cycling, subseafloor microbial communities, and forecasting geohazards. However, the contract for the primary drilling platform supported by the United States since 1985, the JOIDES Resolution, expired in 2024. As such, the future of the scientific drilling program is unknown. Efforts to develop plans for a new vessel—and in the meantime, to secure mission-specific drilling vessels to continue the work of this legacy program—are seen as key steps forward. Without new approaches to addressing both legacy assets and infrastructure needs, the capacity for future U.S. operational and scientific leadership is bleak. It is unlikely that such U.S. leadership can be regained without a U.S.-based drillship. Dedicated funding will be needed to maximize research enabled by the use of legacy assets and to plan for a new era of scientific ocean drilling which includes U.S. leadership and embraces international collaboration.

RECOMMENDATION 4.3: The National Science Foundation (NSF) should take action to regain U.S. leadership in scientific ocean drilling on a global stage. To support basic ocean science and the urgent ocean science research portfolio identified in this report for the next decade and beyond, the committee makes the following recommendations:

- Legacy assets: NSF’s Division of Ocean Sciences (OCE) should create a dedicated funding line for the Legacy Asset Projects program to support expedition-scale collaborations, which maximize the return on legacy assets by providing funding to scientists to conduct large-scale research with existing cores and data.

- New drilling infrastructure:

- OCE should develop a sustainable ocean drilling program, taking into account the need for a U.S.-based drillship. The committee urges NSF to creatively implement management and operational models that ensure viable long-term operations of such a vessel, including developing and nurturing more options for industry work. Such new management and operational models may differ significantly from the recently concluded drilling program.

- Until a dedicated drillship is available, OCE should continue to support the use of mission-specific platforms for addressing high-priority, urgent science questions, and to the extent possible, support efforts to retain the technical and engineering expertise in deep-sea coring previously employed by the United States with the JOIDES Resolution.

- International collaboration and coordination:

- NSF and international funding agencies and governments should coordinate and collaborate globally toward an integrated, long-term strategy for scientific ocean drilling. Such collaboration will require meaningful and transparent reciprocity in scientific participation levels, financial support, scientific planning, and more among contributing partners.

- OCE should renew dialogue with both new and long-standing international partners to identify cost-sharing models for dedicated drillship operations; such models may include scientist shipboard participation proportional to international contribution levels.

Additional Supporting Infrastructure

In addition to supporting the ARF, the OOI, and ocean drilling, OCE supports several other programs that provide the infrastructure to collect data that is necessary to answer the urgent ocean science research questions of the next decade such as the Ocean Bottom Seismographic Instrument Pool, Marine Rock and Sediment Sampling, Ocean Data Facility, Mooring Facilities and Services, autonomous platforms, and marine laboratories. Existing infrastructure is not enough; continued development and/or adaptation of new tools and technologies will enable the sampling of the depths of the ocean and seafloor. Technological development should be supported and conducted in collaboration with strategic partners, involving use-inspired focus groups, community engagement, and broad access for participation and input by transdisciplinary groups.

RECOMMENDATION 4.4: In addition to continuing funding for existing facilities as they support ocean science research priorities for the next decade, the National Science Foundation’s Division of Ocean Sciences, in cooperation with agency and other partners (including private philanthropies), should explicitly support:

- the increased use of autonomous assets for making sustained observations and increasing the efficiency of oceanographic expeditions (expanding the footprint of the vessel while at sea);

- new mechanisms for providing researchers with access to instrumentation—for example, shared instrument pools;

- the collaborative development of revolutionary and innovative sensor technologies for such efforts as collecting ocean chemistry data (e.g., partial pressure of carbon dioxide), biological data (e.g., environmental and organismal DNA, bio-sensors for species abundance), and measuring seafloor geodesy;

- new avenues for bringing novel sensors to market at scale and broadening access to the larger research and management community;

- expansion of data curation efforts to support bioinformatics, artificial intelligence, other analyses, and modeling; and

- the evaluation of new applications of acoustics (e.g., distributed acoustic sensing), Science Monitoring and Reliable Telecommunications cables, and other emerging technologies to identify their potential to contribute to future research.

Universal to all oceanographic assets, data curation that follows FAIR (findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable) and CARE (collective benefit, authority to control, responsibility, ethics) principles is essential for the collaborative development and access of more accurate ocean and seafloor forecasting models, especially when utilizing advances in machine learning and artificial intelligence. The collection and effective integration of disparate ocean datasets—especially new datasets from emerging technologies, such as biotechnology, to support artificial intelligence and machine learning—are needed to create a unified and interoperable ocean information system. Much can be gleaned from existing and recent national and international efforts to develop robust ocean data management strategies; a workshop series or other convening activity would be an appropriate next step for OCE.

RECOMMENDATION 4.5: The National Science Foundation’s Division of Ocean Sciences should fund a convening activity, such as a series of workshops, that seeks to gather expert advice and input, review established strategies, and develop peer-reviewed guidelines and practices for ocean science data curation, computing, and security, both on research vessels and on shore, integrating findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (FAIR) and collective benefit, authority to control, responsibility, ethics (CARE) principles and the required supporting cyberinfrastructure. Data and computational experts from adjacent fields (e.g., applied mathematics) should be encouraged to participate.

CONCLUSION

The 2025–2035 Decadal Survey was developed to ensure that OCE will be empowered to continue to provide the foundational support for ocean science research, not only within NSF, but also across the federal agencies that use ocean science research to accomplish their missions. Now is the time for the United States to invest and take leadership in answering the urgent ocean science priorities outlined in this report, allowing researchers, policy makers, and other leaders to anticipate and understand changes in the ocean system. Such understanding is critical for national security, economic prosperity, environmental stewardship, and for the well-being of humans and the ecosystems on which they depend, in the next decade and beyond.