Health Disparities in the Medical Record and Disability Determinations: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 4 Disparities and Bias in Evaluative Testing and Recording of Medical Information

4

Disparities and Bias in Evaluative Testing and Recording of Medical Information

Key Messages from Individual Speakers

- Ensuring fairness in artificial intelligence (AI) applications is necessary for advancing health equity, and that depends on selecting the appropriate data for training an algorithm, how the algorithm is designed, and how it is deployed in clinics and hospitals. (Chin)

- Individuals and organizations must accept responsibility and be accountable for achieving equity and fairness in outcomes from health care algorithms. (Chin)

- There are areas of the application for disability determination that fall short of being inclusive. The level of documentation required can be troubling for anybody of any race, but that documentation is difficult to obtain for minoritized individuals because of the difficulty they have getting a diagnosis. (Thornton)

- A survey of physicians across the country found that only 60 percent would welcome people with disabilities in their practices, only 40 percent were very confident in their ability to provide quality care, and 36 percent knew little to nothing about the Americans with Disabilities Act. (Lagu)

- There is no federal law and few state mandates, as there is with race and ethnicity, to collect data on disability, and as a result, there are limited data on how many people with disabilities do not get recommended health care interventions. (Lagu)

- Being diagnosed with a disability can put a target on one’s back and can cause more oppression and more people to treat an individual with a disability differently. (Link)

- In Black communities, parents, caregivers, and community members want to protect people from being labeled by medical professionals as disabled. As a result, they do not interact with the health care system for fear that being labeled as having a disability will cause more structural harms. This leads to underrepresentation of Black individuals in some disability datasets. (Link)

The workshop’s third session discussed common tests and clinical algorithms that are inaccurate or inappropriate for specific populations, inequities in accessing diagnostic testing and treatment that may negatively affect disability applications, and biases in the documentation of clinicians of care in the medical record and how findings from tests or screens deemed as objective medical evidence may be minimized. The four speakers in this session were Marshall H. Chin, the Richard Parrillo Family distinguished service professor of health care ethics at the University of Chicago; Gloria Thornton, founder of Amplified Disabled Voices LLC; Tara Lagu, professor of medicine and medical social sciences and the director of the Center for Health Services and Outcomes Research at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine; and AJ Link, president of the National Disabled Legal Professionals Association and an adjunct professor of space law at Howard University School of Law. Rupa Valdez, planning committee member and professor at the University of Virginia and president of the Blue Trunk Foundation, moderated a brief question-and-answer period following the four presentations.

GUIDING PRINCIPLES TO ADDRESS THE EFFECT OF ALGORITHM BIAS ON DISPARITIES IN HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE

Marshall H. Chin said a paper he and his colleagues published in 2023 on how to address algorithmic bias received a great deal of attention, including from the White House, because it pertains to actions regarding the way artificial intelligence (AI) uses algorithms (Chin et al., 2023). He explained that a health care algorithm is a mathematical model used to inform decision making, such as determining whether someone has a disability or not. An algorithm could also be used for treatment, prognosis, risk stratification, triage, and the allocation of resources. AI, he explained, learns by inferring

relationships in a large dataset. The issue is that an algorithm is a black box with limited transparency for how it produces its results.

An unbiased algorithm, said Chin, is one in which patients with the same algorithm score or classification have the same basic needs. An example of a biased algorithm is one clinicians have used to determine who is eligible for a kidney transplant. This algorithm inaccurately assigned higher levels of kidney function to Black patients compared to White patients with the same score on glomerular filtration rate, a primary measure of kidney function. This flaw resulted in delays in referral for kidney transplant for Black individuals (Vyas et al., 2020). Perhaps the most famous example examined a proprietary commercial algorithm designed to determine who would be eligible for chronic disease management programs (Obermeyer et al., 2019). This algorithm made it such that Black patients had to be sicker than White patients to qualify for these programs because it used money and resource use as a proxy for health.

Chin explained that biases can arise in both model development and use. The algorithm that powers pulse oximetry, for example, overestimates oxygen saturation in Black individuals (Shi et al., 2022). Ensuring fairness in AI applications is necessary for advancing health equity, he said, and that depends on selecting the appropriate data for training an algorithm, how the algorithm is designed, and how it is deployed in clinics and hospitals (Rajkomar et al., 2018).

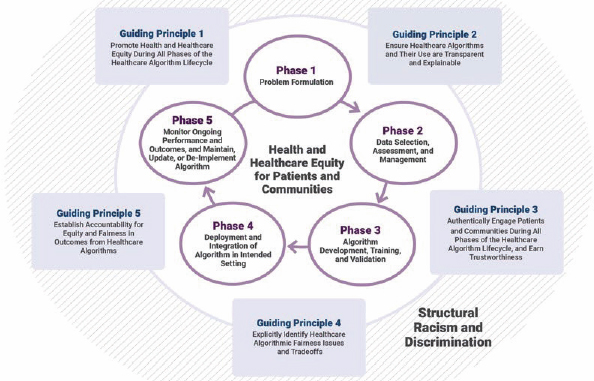

In response to a request from Congress, Chin cochaired a nine-person diverse panel to develop five guiding principles to address the effect of health care algorithms on racial and ethnic inequities in health and health care, each of which is operationalized at the individual, institutional, and societal levels (Figure 4-1). While many groups developing algorithms start with data selection, Chin argued that determining the problem at hand before thinking about data is critical, particularly if the algorithm’s goal is to maximize the health of patients and communities. “In some ways, if you have the wrong problem and goal, that is just the setup for all types of bad things happening,” said Chin. Also important is looking for bias at each of the different phases of an algorithm’s life cycle.

The first guiding principle is to promote equity in all phases of an algorithm’s life cycle. Health equity, said Chin, means that everyone has a fair and just opportunity to be healthy. Achieving health equity requires valuing everyone equally, with focused and ongoing societal efforts to address avoidable inequalities, as well as historical and contemporary injustices, which includes addressing systemic racism and the elimination of health and health care disparities. A fair and equitable algorithm produces equitable outcomes.

The second guiding principle—ensure transparency and explainability—means that all relevant individuals should understand how their data are used

SOURCES: Chin presentation, April 4, 2024; Chin et al., 2023. CC-BY-NC-ND.

and how AI systems make decisions. To be transparent, every algorithm, its attributions and its correlations, should be open to inspection. Explanations should correctly reflect the system’s process for generating output, which should be used only when the system achieves sufficient confidence in its results (Zuckerman et al., 2022).

Chin said the third principle is to authentically engage patients and communities to earn trust. This requires engaging patients in choosing a problem, selecting the data to inform the algorithm, developing and deploying the algorithm, and monitoring its output. “Patients must know how an algorithm affects their care,” he said. Trustworthiness, he added, is earned through authenticity, ethical practices, data security, and timely disclosures of algorithm use. He noted there are important data sovereignty issues for American Indians and Alaska Natives regarding data ownership.

The fourth principle—identify fairness issues and trade-offs—is critical, said Chin. Algorithmic fairness and bias issues arise from both ethical choices and technical decisions at each stage of the algorithm’s life cycle. It is important to identify fairness and bias issues and address them directly, with fair distribution of social benefit and burden serving as an ethical framework for judging fairness and bias. From a technical perspective, Chin explained that different technical definitions of algorithmic fairness are mathematically mutually incompatible, trading off maximizing accuracy of an algorithm for entire groups and minimizing accuracy differences among subgroups across definitions.

The panel’s report argues for mitigating bias both through social means, by having diverse teams and codevelopment, and by using technical algorithmic fairness tool kits. “We also need to view algorithms and accompanying policies and regulations through frames of equity of harms and risks,” said Chin, particularly for algorithms dealing with disability where there is the potential for high-risk and high-harm issues to arise. Models, said Chin, should be optimized for equity in clinical outcomes or resource allocation using bias mitigation methods and human judgment, with explicit identification of trade-offs among competing values and options.

The final principle is accountability. Individuals and organizations must accept responsibility and be accountable for achieving equity and fairness in outcomes from health care algorithms. Organizations should be comprehensive in establishing processes at each stage of the life cycle of the algorithm to facilitate equity and fairness in outcomes. Organizations should also have an inventory of their algorithms and periodically screen them for, and mitigate, bias. Chin said:

We think it is important to have very important oversight of prediction models, with checkpoint gates at each phase of the algorithm life cycle, oversight governance structures that involve the public, and an investment in the infrastructure to do things the right way in terms of avoiding bias.

All regulations and incentives should support equity and fairness, and algorithms should not be deployed before validating them on the affected population. In addition, “those persons and communities who have been harmed by unfair algorithms should be redressed,” said Chin.

Chin concluded his presentation with a list of overarching issues and challenges:

- Technical definitions and metrics of fairness rarely translate clearly or intuitively to ethical, legal, social, and economic conceptions of fairness.

- Trade-offs among competing fairness metrics and values are common.

- There is no cookie-cutter solution to fairness and equity, making it imperative to individualize each use case.

- There can be trade-offs between equity and justice versus efficiency and saving money.

- Communication challenges include explaining probabilities and distributions, assessing and explaining real data and synthetic data, assessing and explaining the validity of applying a specific algorithm to a specific individual, and explaining the difference between legal informed consent and patients truly understanding and providing informed consent.

Regulations and incentives, said Chin, should support equity and fairness while also promoting innovation. In addition, the AI field needs to create an ethical, legal, social, and administrative framework and culture that redresses harm while encouraging quality improvement, collaboration, and transparency similar to recommendations for patient safety. As a final comment, he said,

ChatGPT and other AI language models have spurred widespread public interest in the potential value and dangers of algorithms. Multiple stakeholders must partner to create systems, processes, regulations, incentives, standards, and policies to mitigate and prevent algorithm bias in health care. Dedicated resources and the support of leaders and the public are critical for successful reform. It is our obligation to avoid repeating errors that tainted use of algorithms in other fields.

HEALTH INEQUITIES THROUGH THE LENS OF A PERSON WITH DISABILITIES

Gloria Thornton said that as a person with disabilities, she has been treated in a variety of ways, and she noticed that multiple factors contribute to why she is treated differently, including being a woman, being African American, having invisible disabilities, being visibly disabled, having a mental health diagnosis, and being educated. “Whenever I speak on this topic, it is coming from a place of passion and love, but also frustration and a level of sadness,” she said.

When Thornton was in middle school, she began having noticeable health issues that doctors kept dismissing as anxiety, depression, a lack of social skills, or a failure to thrive. “This is when my fear of medical providers started and my medical files began to receive life-altering notes that made finding reputable doctors for my care difficult,” she explained.

In December 2020, Thornton contracted aseptic meningitis from a treatment one of her most trusted clinicians suggested via home health. “While the doctor was amazing, the nurse that I had at the time decided that my doctor’s instructions were too long, and she did not want to stay at my house for the allotted twelve hours, so she did the twelve-hour treatment in four,” said Thornton. The result was an almost two-week stay in the hospital, where she had time to think about what happened to her and experience of medical biases firsthand. Because of the emergence of COVID-19 at that time, she was sent home prematurely but had to be readmitted several days later. During this admission, the doctor on her floor refused her multiple daily medications and pain medications, although he could see her visible pain. His reason was that “People like you don’t have pain from diseases like this.”

In July 2022, Thornton was experiencing back pain and saw a physician assistant who told her he would help her find answers. However, after ordering

a couple of tests, he sent her a note telling her to find someone else because her problems were “above his pay grade.” “Stories like this are all too common,” said Thornton, who added that having information in the EHR that paints an individual as being noncompliant, incompetent, lying, or exaggerating will lead to many adversities in getting care. For one thing, it was difficult for her to get assistance through either Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) or Supplemental Security Income (SSI). “This is why it is important to focus on specific definitions of terms used within different health records and program requirements,” she said.

According to federal regulations, the law defines disability, for the purpose of Social Security disability programs for adults, as the inability to do any substantial gainful activity for any medically determinable physical or mental impairment that will likely result in death or that has lasted or will likely last for a continuous period of not less than twelve months. While this definition sounds simple and unbiased, there are areas of the application for disability determination that fall short of being inclusive, said Thornton. The level of documentation required can be troubling for anybody of any race, but that documentation is difficult to obtain for minoritized individuals because of the difficulty they have getting a diagnosis. Thornton was told by the hospital system that her records had been destroyed or did not exist. “As a minority disabled woman, I often believe sometimes I am better off avoiding doctors and medical offices due to the amount of medical biases, discrepancies, and ableism I endured,” she said. In the end, she retracted her application,

After describing the multiple steps and multiple clinicians that must be involved to receive a new wheelchair, Thornton said she works as an ombudsman for others to address the problems that create delays. “As an advocate, I use my voice to speak for people with disabilities who are unable to receive the items they need in order to receive the best care,” she said. As a final comment, she noted that SSI and SSDI are designed to help people with disabilities, but the process is so tedious that people like herself either start the application and do not complete it or they attempt to complete the application, receive a denial, and do not try again. “The policies surrounding SSDI and SSI and the definition of disability need to be reassessed in order to focus on the population being helped,” said Thornton. “This is a process designed to help people, but instead it results in people with disabilities dealing with the consistent stress of [getting] approval.”

DATA COLLECTION AND IDENTIFICATION OF DISABILITY STATUS: NECESSARY TOOLS TO IMPROVE CARE ACCESS AND REDUCE HEALTH CARE DISPARITIES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES

Tara Lagu recalled how when she was discharging a patient who used a wheelchair, she could not get her an appointment with a subspecialist, and as she rolled out the door, the patient said this was discrimination. Thinking this assessment was correct, Lagu spent the next year calling subspecialists around the country and asked them if they would make an appointment for a fictional patient who used a wheelchair. What she found was shocking: approximately 22 percent of the 256 practices she contacted would not make an appointment for someone in a wheelchair, either because their practices were in inaccessible buildings or because they could not transfer the patient to an exam table. Slightly more than half of the other clinicians planned to transfer the patient to the exam table manually, which is considered dangerous, and less than 10 percent of the practices had adjustable tables or other accessible equipment.

After publishing her findings (Lagu et al., 2013), Lagu began looking into how this major inequity existed when legislation protects the rights of people with disabilities. “It seems there are persistent disparities in health care access for this group of people,” she said. With two colleagues, she wrote a paper describing what clinicians should do in three realms to care for people with disabilities: physical access, communication access, and programmatic access (Lagu et al., 2014). Enabling physical access requires having room next to the exam table for a wheelchair, an adjustable height table, space to allow transfers, and an accessible route in and out of the exam room.

Communication access means that providers and patients should work together to identify alternative communication methods for patients with disabilities, whether that be having telecommunication devices or sign language interpreters for people with hearing loss, or large print forms for individuals with visual impairments. Programmatic access requires universal access to scheduling, staffing, and other administrative resources; that the system alerts the receptionist and staff when a patient with a disability makes an appointment; and that a room with an accessible table is reserved for the patient’s appointment. When she gets pushback on the need for the scheduling system to alert staff, she counters by pointing out that people with a penicillin allergy rarely get penicillin because that information is in the EHR.

Though Lagu and her colleagues published their second paper in the New England Journal of Medicine, nothing has changed. A subsequent study of clinics with or without adjustable tables found that individuals with disabilities receiving care in those clinics with height adjustable tables reported no difference in perceived quality of care or the exam they received (Morris

et al., 2017). This finding suggested the problem may be related to physician attitudes, so Lagu and colleagues surveyed 71 physicians across the country and found that only 56.5 percent would welcome people with disabilities in their practices, only 40 percent were very confident in their ability to provide quality care, and 36 percent knew little to nothing about the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA) (Iezzoni et al., 2021, 2022).

Speaking with clinicians in focus groups, she found many of the same barriers (Lagu et al., 2022). In addition, some clinicians described specific strategies they use to discharge people with disabilities from their practices. One reason the clinicians gave was that they do not want to fill out the paperwork required for SSDI or SSI. “If you think about this, the need to document medical issues for the Social Security Administration (SSA) is not possible if you cannot get an appointment with a doctor or if your doctor discharges you from their practice,” said Lagu. “This might explain some of the disparities in health care access and quality we have seen.” This, she added, is the ableism that exists in the nation’s health care system and is keeping people with disabilities from getting the care they need and the documentation they need to get the services and benefits SSA can offer.

Lagu noted there is limited federal law and few state mandates, as there is with race and ethnicity, to collect data on disability. As a result, there are no data on how many people with disabilities do not get cancer screenings or cardiovascular interventions. While some health systems want to collect these data, they are discouraged from doing so because if they collect the data and the data reveal gaps in care and a failure to provide the needed accommodations, they will be at risk of unfavorable comparisons to peer organizations that do not collect these data. Without a mandate, few health systems will collect the data voluntarily for all patients, said Lagu, pointing to the need for federal or state laws, policies, and procedures requiring data collection. There is also the need, she added, to incorporate collecting data on disability status into hospital and health system accreditation criteria.

Another issue, said Lagu, is the confusion arising from varying definitions of disability, which raises the question of why the SSA and ADA definitions differ. Lagu explained the ADA is civil rights law, and civil rights should be inclusive and broad, while SSA needs to limit the number of eligible beneficiaries. Complicating the matter, health systems might be on board with collecting the information to accommodate patients, bridging gaps in care, and not violating the ADA, but they are less interested in sharing data from their EHRs if it is used to determine disability, fearing that third parties will use the data for reasons that are beyond the scope of medical care.

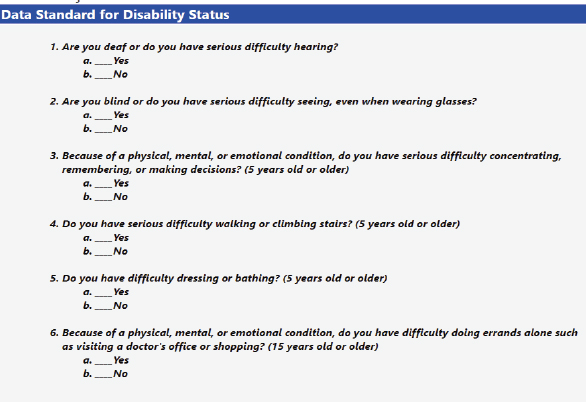

A third issue is that prior attempts to identify disability from the EHR alone have failed, and a fourth issue is the lack of standard questions about disability and accommodations, making data collection challenging. Exist-

ing questions from the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) are broad and do not accurately capture disability severity or chronicity (Figure 4-2). In addition, there are no validated questions about accommodations and no support to conduct the research to validate such questions.

There is also unclear buy-in from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and other federal agencies where people with disabilities experience disparities. Lagu noted that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HHS, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and NIH now recognize disability as a disparity population, but she is waiting to see if these federal organizations will take the necessary steps to support data collection or fund studies that focus on disability independent of race and other social vulnerabilities.

To remedy this situation, Lagu called for working with advocacy groups to highlight and, when possible, address these structural barriers and encouraged being outspoken about these issues. Health systems, EHR vendors, and insurance companies are not the enemy, she added. “I have found that health systems, vendors, and insurance companies actually want to work with us, but they also want the mandate from federal and state governments,” she said. She noted that she is doing research on the margins, so some of this work will get done, but some will not because it will not get funded.

SOURCES: Lagu presentation, April 4, 2024; https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=3&lvlid=53 (accessed February 2024).

BARRIERS TO INITIATE PARTICIPATION IN INTERACTING WITH THE SYSTEM

AJ Link told the workshop he is openly autistic, a nonapparent disability, and has other identities, such as being a Black man from Florida, a southerner, a new husband, and a father. “Those are all identities that I carry around the world with me, but that also impacts how I experience going through the health care system when I decide to do it and have the autonomy to choose that,” said Link. He added that he has a different experience than many people with autism because he was diagnosed as an adult and has good health insurance. For him, it was empowering to learn he is autistic because it explained why he struggled with so many things. Although his diagnosis was a powerful revelation for him, Link said that is not always true, particularly for people from marginalized backgrounds. “Oftentimes, being diagnosed can put a target on your back. It can cause more oppression and cause more people to treat you differently,” he said.

Link discussed the barriers to getting care in historically marginalized communities. There is a stigma attached to being disabled, especially if the disability is not apparent. This is especially true for school, where special education was created to reinforce racism and segregation (Connor and Ferri, 2005). In Black communities, he said, patients, caregivers, and community members want to protect people from being labeled as disabled, so they do not interact with the health care system for fear that being labeled as having a disability will cause more structural harms.

Financial issues can be another barrier, and not just being able to afford the cost of a health care visit. Taking time from work, taking the time to find the right physician to see, and having to take public transportation to get to an appointment are the kinds of barriers that prevent people in historically marginalized communities from seeking care. Quality of care is another issue, said Link. “We all know the structural inequalities in our society and where the best care is available,” he said, referring to the geographic barriers to accessing quality care.

The health care system itself and the history of medical racism and abuses the Black community has experienced are other barriers to seeking care, said Link. He also noted the benefits of classism and who benefits from being labeled as disabled. “There is racism within the disabled community, but there is also a level of classism,” said Link. “Most people who are fortunate enough to openly identify as disabled like I am come from a higher stratum of class, where they are protected from the discrimination, the stigma, and then the consequences of being openly disabled.”

Link noted that from a medical perspective, the discussion can center on diagnoses, prescriptions, and recommendations, but regarding adequate access to care, there is the issue of overcoming historical mistrust and convincing

people they will receive quality care that will be helpful. He also questioned whether information about quality care is accessible to marginalized communities in nonmedicalized language.

Another challenge is educating marginalized communities about the benefits available to people with disabilities, such as SSDI or SSI, and the protections they have under civil rights laws such as the ADA or the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. Link asked:

How are we providing that social education that shows that you can use a disabled diagnosis or a diagnosis of a disability as an opportunity to fight for your equal rights when it comes to things like housing, when it comes to things like education, when it comes to things like protection?

Finally, there is the cultural aspect to accessing care. “How do we provide support for those communities that want to be more accessible but do not want to interact with a system that is incredibly racist and ableist?” he asked. “How do we provide the tools for communities to self-accommodate and to identify some of the consequences of disability?” There is a balance here between self-accommodation and seeking care for impairments that need attention from a medical professional. The answer to that problem is to empower people to understand the different disabilities that need medical intervention and disabilities that are strictly problematic because of ableist systems within our communities, he said.

Q&A WITH THE PANELISTS

Rupa Valdez opened the discussion by asking Chin to provide examples of tests or procedures that are less accurate for certain population subgroups. Chin explained that clinical tests often have a normal range, and the question is, where do these normal values originate and how are they adjusted for a patient’s race? Many times, he said, these adjustments are “basically voodoo” and result from explicitly racist attitudes. For example, the racial adjustments for a pulmonary function test were based on a mistaken nineteenth-century view that Black people had less ability to metabolize oxygen and had less lung capacity. The problem, he said, arises when the medical community blindly accepts these reference values even though the scientific evidence base for them is faulty. At the same time, changing a reference value can have downstream effects for determining disability eligibility, so there needs to be the evidence base to make that change. “We cannot divorce some of these technical questions from the societal issues that are involved,” said Chin. For that reason, it is imperative to involve the affected communities, be transparent and explicit about identifying ethical issues, and then address them rather than “sweeping them under the rug.”

Valdez asked the panelists to comment on how identifying biased or untrustworthy health care providers changes how people with disabilities seek care. Link replied that it stops people from seeking care that could be beneficial or even lifesaving, and people choose not to go through the hassle of filling out the paperwork for a disability determination. He added that getting a disability diagnosis is more than just having a good doctor, for it affects how he moves through society and what jobs he has. “It is more than just do I have a good provider or can I find a good provider. Is the system working for me in a way that I can survive in society? For a lot of people, that answer is no, unfortunately,” said Link.

Thornton recalled how she had waited six months to get an appointment with her doctor—a time when she was anxious and praying that the doctor would listen to her—only to have him tell her he did not want her as a patient. Frustrated at having to start over, she waited a year before she saw a different provider and had the surgery she should have had earlier.

An unidentified workshop participant asked Lagu to talk about the systemic changes that need to occur. She replied that change must start in medical school and during medical training. She also suggested that physician attitudes would change quickly if they could bill at a higher level for working with patients with a disability and that hospitals would change their behavior quickly if accommodating people with disabilities was included in their accreditation process. Lagu said she has gotten pushback on this idea because it would treat a person with a disability differently. Chin agreed with Lagu that there must be structural reforms, such as designing clinics to be accessible and establishing longer appointment times for conducting disability evaluations.

Link said there is a fundamental tension between the medical model of disability that looks to cure or eradicate impairments versus a rights-based model of disability that acknowledges it is okay to be disabled and provides the right accommodations and access for people with a disability to thrive. “As long as our rights-based model is based on the medical model of disability, you are going to have problems with disabled people trying to access any type of social equality in that framework,” said Link. “I do not know how to fix that, but that is something that we have to admit before we can do any real work.”

Vincent Nibali asked the panelists for their thoughts on how to extract knowledge about community care and support—information that will not be in an EHR—for SSA’s use. Thornton commented that researchers should think about how to access community knowledge and include that in a disability determination. For example, centers for independent living could produce documents that would fill gaps and support a disability determination. Link added that going into communities where there is a level of distrust and asking them to disclose their disabilities is challenging. “It is going to require a

lot of work to build trust before we can even get to the point of saying which members of your community are disabled or display these signs of disability,” said Link. Chin said community involvement is critical for many equity issues and raises the question of what participation means. There is a difference, for example, between a community advisory group and a group involved consistently in decision making.

Thornton pointed to the need to develop a specific definition of disability. In her case, after she had a spinal fusion, her employer sent her a letter informing her she was not disabled enough to qualify for disability, and two weeks later she received another letter saying she was too disabled to return to work and was being severed from the company. “This company is using multiple different definitions and understanding of disability to detrimentally affect my life without speaking [to me] and understanding what is going on.”

Kenrick Cato, Professor of Informatics, University of Pennsylvania, asked the panelists for examples of cultural change that improved this situation. Link said that the process must start with education and getting people to understand that increasing accessibility for disabled people increases access for everyone. Thornton commented that filling out a form at a first visit to a provider and checking a race box is often where a practice’s understanding of who one is as a person stops. However, her cultural understanding would differ from Lagu’s cultural understanding, so these differences will cause significant issues. Chin added that the only way to change cultural attitudes is to have in-person experiences with individuals of different cultural backgrounds. “In the case of a person with disabilities, it cannot just be statistics and quantitative data. It cannot just be abstract stories. It has to be in person and [include] sharing of lived experience and honest discussions. That really is our only chance,” said Chin.

Lagu said she has great hope for the medical profession because there is a grassroots movement among medical students and faculty to incorporate disability education into the medical curriculum and clinical training. “We have seen buy-in from our health system and a real willingness to change attitudes and structural barriers,” said Lagu.