Health Disparities in the Medical Record and Disability Determinations: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 2 Overview, Concepts, and Framing

2

Overview, Concepts, and Framing

Key Messages from Individual Speakers

- The medical model of disability locates the problem of disability at the person, and it operates in the context of disease, disorders, and impairments. The social model of disability understands disabilities in terms of attitudinal barriers, barriers in the built environment, and noninclusive practices that work together to prevent people with impairments from participating in various activities. (Houtrow)

- The Social Security Administration’s (SSA’s) disability programs are not driven by diagnoses but are evidence- or impairment-driven programs. (Nibali)

- Achieving health equity is not a finite project that will be implemented or completed in a predictable period of time. It requires a constant process and engaging a cycle of improvement that actively engages those most affected in all stages of the process. (Platt)

- Billing is at the core of electronic health records, but today they are central to clinical care, quality reporting, and regulatory compliance, serving as accessible repositories of patient information and supporting clinical decision making. Clinical decision support is an increasingly important function of electronic health records. (Kawamoto)

The workshop’s first session provided a high-level overview of topics that served as background for the rest of the workshop. The four speakers in this session were Amy J. Houtrow, professor and vice chair in the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation for Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine; Vincent Nibali, policy analyst at the Social Security Administration (SSA); Jonathan Platt, assistant professor at the University of Iowa College of Public Health; and Kensaku Kawamoto, associate chief medical information officer at University of Utah Health and professor and vice chair of clinical informatics in the University of Utah’s Department of Biomedical Informatics.

DEFINITION OF DISABILITY

Houtrow began her presentation by displaying a thought bubble containing words people might associate with disability, depending on their perspective (Figure 2-1). She explained:

From a doctoring perspective, we might think of a health condition or a disorder or a disease. From a person’s body and how it works, we might think of impairments. And people with disabilities often think of disability as identity.

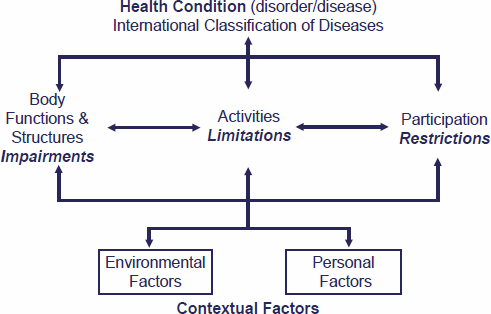

In the academic world, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health provides a useful framework for framing and understanding disability (Figure 2-2) and the experiences of people with disabilities

SOURCE: Houtrow presentation, April 4, 2024.

SOURCES: Houtrow presentation, April 4, 2024; World Health Organization (WHO). 2001. CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

(World Health Organization, 2001). Clinicians use the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) to classify the myriad diseases, disorders, and conditions that affect humans. Environmental and personal factors interact with an individual’s health condition and contextualize people’s experiences. Houtrow said:

When we think about a health condition, we are thinking about impairments at the body level, activity limitations in what someone does, and participation restriction and how they are able to engage successfully as desired in society.

Houtrow explained the difference between the medical and social models of disability. The medical model locates the problem of disability at the person, and it operates in the context of disease, disorders, and impairments. The social model understands disabilities in terms of attitudinal barriers, barriers in the built environment and noninclusive practices that work together to prevent people with impairments from participating in various activities.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines disability as

Any condition of the body or mind (impairment) that makes it more difficult for the person with the condition to do certain activities (activity limitation) and interact with the world around them (participation restrictions). (CDC, 2024)

Based on this definition, CDC estimates that 27 percent of U.S. adults have a disability. According to the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA), a person with a disability is someone who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities.1 This includes people who have a history or record of such an impairment or a person others perceive as having such an impairment (Civil Rights Division, 2008).

Houtrow said meeting SSA’s definition of disability requires an individual be unable to engage in any substantial gainful activity because of a medically determinable physical or mental impairment expected to lead to death or that has lasted or is expected to last for a continuous period of at least twelve months. Making that determination requires objective medical evidence and laboratory findings, among other considerations. SSA considers children to be disabled if the child has a medically determinable physical or mental impairment or combination of these two factors, if the impairment results in marked and severe functional limitations, and if the impairment has lasted, or is expected to last, for at least one year or until death. Domains of activity for assessing a child’s functioning include acquiring and using information, attending to and completing tasks, interacting and relating with others, moving about and manipulating objects, caring for one’s self, and health and physical well-being.

Houtrow commented on the language for discussing disability. Person-first language, such as “Amy is a person with disabilities,” shifts the focus from the impairment to the social barriers that impede full participation in society as desired. Identity-first language, such as “I am a disabled woman,” treats the disability as a cultural identity from which the individual cannot separate themself. Houtrow said:

There are ongoing conversations about when and where this language should be used, and it is really about a shared common goal to recognize, affirm, and validate all of our identities in personhood and to recognize people with disabilities as equal members in our society. Today you will hear both, and both are deemed acceptable.

OVERVIEW OF SSA’S DISABILITY DETERMINATION PROCESS

Vincent Nibali explained that while the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI) programs have different nonmedical eligibility requirements, both have the same medical and vocational eligibility requirements and both are only for individuals with a complete disability

___________________

1 Major life activities include eating, sleeping, speaking, breathing, walking, standing, lifting, bending, thinking and concentrating, seeing and hearing, and working, reading, learning, and communicating.

that leaves the individual unable to work. SSA defines disability for adults as the inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity (SGA) because of a medically determinable physical or mental impairment that will likely result in death or that has lasted or that will likely last for a continuous period of not less than twelve months. SGA is an SSA term defined by earnings per month. For 2024, the value for SGA is $1,550 or more per month and $2,590 for blind individuals.

To determine if an adult meets the requirement to be unable to engage in SGA, SSA has a five-step, sequential evaluation process that allows it to make a disability decision at the earliest possible step without prejudicing any claimants:

- Is the individual engaged in SGA?

- Is the impairment a medically determinable physical or mental impairment that is severe, and does it meet the duration requirement (see Box 2-1)?

- Does the individual’s medical condition meet or medically equal a listing, where listings are publicly available sets of criteria for specific impairments that SSA believes represent a higher level of limitation than the program requires in general (see Box 2-2)?

- Does the impairment prevent the individual from performing their past relevant work?

- Does the individual have the ability to adjust to other work?

BOX 2-1

Definition of Terms Relevant to Determining Impairment Severity

- Medically determinable impairment: An impairment must result from anatomical, physiological, or psychological abnormalities that can be shown by medically acceptable clinical and laboratory diagnostic techniques. Therefore, a physical or mental impairment must be established by objective medical evidence from an acceptable medical source.

- Objective medical evidence: Signs, laboratory findings, or both.

- Acceptable medical source: A licensed physician or psychologist, or when within the scope of their practice, an optometrist, podiatrist, speech-language pathologist, audiologist, licensed advanced practice registered nurse, or licensed physician assistant.

SOURCE: Nibali presentation, April 4, 2024.

BOX 2-2

Listings of Impairments

Listings of impairments describe for each of the major body systems impairments that SSA considers to be severe enough to prevent an individual from doing any gainful activity, regardless of age, education, or work experience. In the case of children under age 18, the impairment must be severe enough to cause marked and severe functional limitations. The listings are special rules that provide SSA with a mechanism to identify claims that it should clearly allow. An impairment (or combination of impairments) is medically equal to a listed impairment in the listings if it is at least equal in severity and duration to the criteria of any listed impairment.

SOURCE: Nibali presentation, April 4, 2024.

Nibali explained that if an individual meets the criteria of a listing, SSA will find them disabled at Step 3, with no need to proceed to Steps 4 and 5. However, SSA will never find someone is not disabled if they do not meet the Step 3 criteria. He also noted that SSA’s disability programs are not driven by diagnoses but are evidence- or impairment-driven programs. “Just because a doctor has never signed on the line diagnosing you with a specific condition does not mean we cannot consider that condition or the underlying limitations from it,” said Nibali. Before moving to Steps 4 and 5, SSA determines an individual’s “residual functional capacity,” the most a claimant can do, despite their limitations. This determination is based on all relevant evidence in the case record and considers all medical determinable impairments, even those that are not severe.

To define the work requirements for Steps 4 and 5, SSA has used the 1991 edition of the Dictionary of Occupational Titles. However, because this publication has not been updated, SSA is working with the Bureau of Labor and Statistics to collect data and develop a new set of vocational requirements it will use for Steps 4 and 5.

For children, SSA uses a different set of criteria that includes:

- A medically determinable physical or mental impairment or combination of impairments that causes marked and severe functional limitations, and that will likely result in death or that has lasted or will likely last for a continuous period of not less than twelve months; and

- An impairment (or impairments) causes marked and severe functional limitations if it meets or medically equals the severity of a set of criteria for an impairment in the listings, or if it functionally equals the listings.

In the adjudication process for a child’s disability, SSA follows the first two steps in the adult process, but for Step 3, SSA adds the concept of “functionally equals the listings.”2 Nibali specified the term functionally equals the listing means an impairment must be of listing-level severity that results in marked limitations in two domains of functioning or an extreme limitation in one domain compared to children of the same age without impairments. The six relevant domains are acquiring and using information, attending to and completing tasks, interacting and relating with others, moving about and manipulating objects, caring for oneself, and health and physical well-being.

BASICS OF HEALTH DISPARITIES

Jonathan Platt began his presentation by defining key terms and concepts relevant to health disparities and describing potential steps to achieve health equity (see Box 2-3 and Figure 2-3). He noted that people with disabilities experience a range of disparities. For example, while people with disabilities account for 11.7 percent of the school population, they account for 25 percent of all suspensions, 23 percent of all expulsions, and 27 percent of all arrests at school. Black students, who make up 19 percent of students with disabilities, account for 36 percent of suspended students with disabilities (Nowicki, 2018). In addition, people with disabilities are twice as likely to be unemployed (Office of Disability Employment Policy, 2024) and are more likely to be incarcerated (Bixby et al., 2022).

According to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, “Achieving health equity starts with identifying disparities of concern to stakeholders—particularly those members of affected populations—and their potential causes.”3 To illustrate this, Platt presented on what he described as the “4 Steps to Achieving Health Equity.” The first step of health equity includes identifying the upstream social inequities, challenges that affect access to needed resources, and opportunities individuals need to be healthier. The second step of health equity is eliminating the unfair social conditions creating inequity by changing policies, laws, systems, and institutional practices that create barriers and restrict opportunities is critical. While it may take decades or generations to reduce some health disparities, public funders want to see measurable gains

___________________

2 C.F.R. § 416.926a.

3 https://www.rwjf.org/en/our-vision/focus-areas/Features/achieving-health-equity.html (accessed June 26, 2024).

BOX 2-3

Key Health Disparities Concepts and Terms

- Health equity: A state of fair and just opportunities to be as healthy as possible (Harper et al., 2010). Equity is both a process and an outcome, often measured as reductions in disparities by improving the health of disadvantaged groups. Achieving health equity requires removing obstacles and increasing opportunities to maximize health, most often by addressing social determinants of health.

- Health disparities: Avoidable, systematic health differences that adversely affect socially (including economically) disadvantaged groups. They are of concern even when their causes are not fully understood because they affect groups already at an underlying disadvantage and may expand the disadvantage with respect to their health.

- Social determinants of health: Nonmedical factors, such as employment, income, housing, transportation, childcare, education, the legal and political system, access to medical care, and the quality of the places people live, work, learn, and play, that influence health and are shaped by social policies (Krieger, 2001).

- Disadvantaged groups: Those who have been excluded from accessing the social and material resources available to other groups in society, often resulting from discrimination or marginalization. These groups include, but are not limited to, people of color, people living in poverty, LGBTQ+ individuals, women, gender-nonconforming individuals, and people with physical and mental disabilities.

- Discrimination: The process by which individuals or groups are treated unfairly because of their perceived or actual group identity as a means of reinforcing positions of power and privilege. Discrimination arises from socially derived beliefs about groups and their members, and it can occur intentionally or unconsciously and be intrapersonal, interpersonal, or structural (Jones, 2000).

SOURCES: Platt presentation, April 4, 2024. Derived from Harper et al., 2010; Krieger, 2001; and Jones, 2000.

SOURCE: Platt presentation, April 4, 2024.

from their investments in the short term too. The third step of health equity is to identify short- and intermediate-term outcome indicators that could be improved within the time frame of an initiative, said Platt.

The fourth step to achieving health equity is to reassess strategies, make adjustments, and plan next steps. “Achieving equity is not a finite project that will be implemented or completed in a predictable period of time,” said Platt, explaining:

It requires a constant process and engaging a cycle of improvement that actively engages those most affected in all stages of the process ... and a sustained commitment to improving health for all, and particularly those with the greatest needs, that must be a deeply held value throughout society.

To end on a hopeful note, Platt discussed successful efforts to reduce social and health inequities. The Villages of East Lake in Atlanta, Georgia, is a community that had experienced a cycle of economic neglect, extreme poverty, violent crime, high unemployment, low educational achievements, and poor health outcomes. A partnership between East Lake residents, the Atlanta Housing Authority, Atlanta Public Schools, and the YMCA created high-quality, mixed-income housing; a cradle-to-college educational pipeline; and wellness resources. This comprehensive community transformation resulted in reduced rates of childhood asthma and obesity, a 90 percent reduction in violent crime, a reduction from 59 to 5 percent of subsidized housing residents on public assistance, and an increase from 13 to 100 percent of nonelderly residents employed or in job training. The success of the East Lake model led to the founding of Purpose

Built Communities, a nonprofit organization that works to replicate the successful elements of the East Lake model in other low-income communities across the nation. Founded in 2009, Purpose Built Communities is now active in 26 communities in 14 states (Purpose Built Communities, 2024).

As an example of a policy that addresses social and health disparities, Platt discussed the 1993 expansion of the earned income tax credit, which gives larger tax refunds to low-income families with children. Studies have shown that expanding the earned income tax credit contributed to improvements in maternal health, mental health, and biological markers of risk for chronic disease (Evans and Garthwaite, 2014). The ADA represents a policy change that expanded access and protections from discrimination for people with disabilities. The Urban Institute’s Disability Equity Policy Initiative aims to equip policy makers and practitioners with the rigorous, timely, and actionable research they need to advance economic mobility, housing stability, community connections, and a more accessible and equitable public safety net (Urban Institute, 2024).

THE PURPOSE AND FUNCTION OF THE MEDICAL RECORD

Kensaku Kawamoto explained that the medical record—also called the health record or patient chart—is a record of a patient’s medical information, including diagnoses, clinical notes, test results, treatments and procedures, social and family history, and medications. For the most part, the electronic medical record and electronic health record (EHR) are synonymous and contain all the information in a patient’s paper chart. In 2004, EHR adoption was at 13 percent; however, the Meaningful Use incentive program has increased EHR adoption to 96 percent of hospitals (ONC, 2021a), and 88 percent of office-based physicians (ONC, 2021b) had adopted EHRs by 2021. Today, most EHRs are commercial systems (Figure 2-4).

SOURCES: Kawamoto presentation, slide 4. Data derived from https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/ehrs/ehr-vendor-market-share-in-the-us.html (accessed March 21, 2024); https://www.definitivehc.com/blog/top-ambulatory-ehr-systems (accessed March 21, 2024).

Billing, said Kawamoto, is at the core of EHR systems and is the reason EHRs were first created. Today, they are central to clinical care, quality reporting, and regulatory compliance, serving as accessible repositories of patient information and supporting clinical decision making. In addition, EHRs help automate and streamline clinical workflows and enable standards-based data sharing. Functionality, he added, can differ significantly across EHR systems or even across institutions using the same system because of customizations. While useful, multiple studies have shown that EHRs are a major cause of physician frustration and burnout (Budd, 2023; Calandra et al., 2022; Robertson et al., 2017).

Clinical decision support is an increasingly important EHR function. In this role, an EHR can provide clinicians and patients with knowledge and person-specific information filtered intelligently and presented at appropriate times, such as through alerts and reminders, to enhance health and health care. EHR-based clinical decision support aims to address two research findings: patients, in general, only receive about half of the evidence-based and recommended care, and it takes 15 to 20 years before best practices are adopted widely (National Academy of Medicine, 2017). However, if not done well, decision support can annoy clinicians with too many pop-up alerts.

Kawamoto explained that federal incentives encourage clinicians and hospitals to use certified EHRs. The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services collaborate to define and regularly update certification requirements. These requirements are the basis for common functionality and interoperability standards applicable to virtually all EHRs. Today, there are penalties for not using a certified EHR. Kawamoto suggested that if SSA would find certain features and information useful, it could make its wishes known to inform future updates to the certification criteria so every EHR could provide the necessary information.

This page intentionally left blank.