Resilience in Transportation Networks, Volume 1: Resilience Case Studies (2024)

Chapter: Section 3: Case Studies

Section 3: Case Studies

3A.1: ARC Vulnerability and Resiliency Framework for the Atlanta Region

Summary

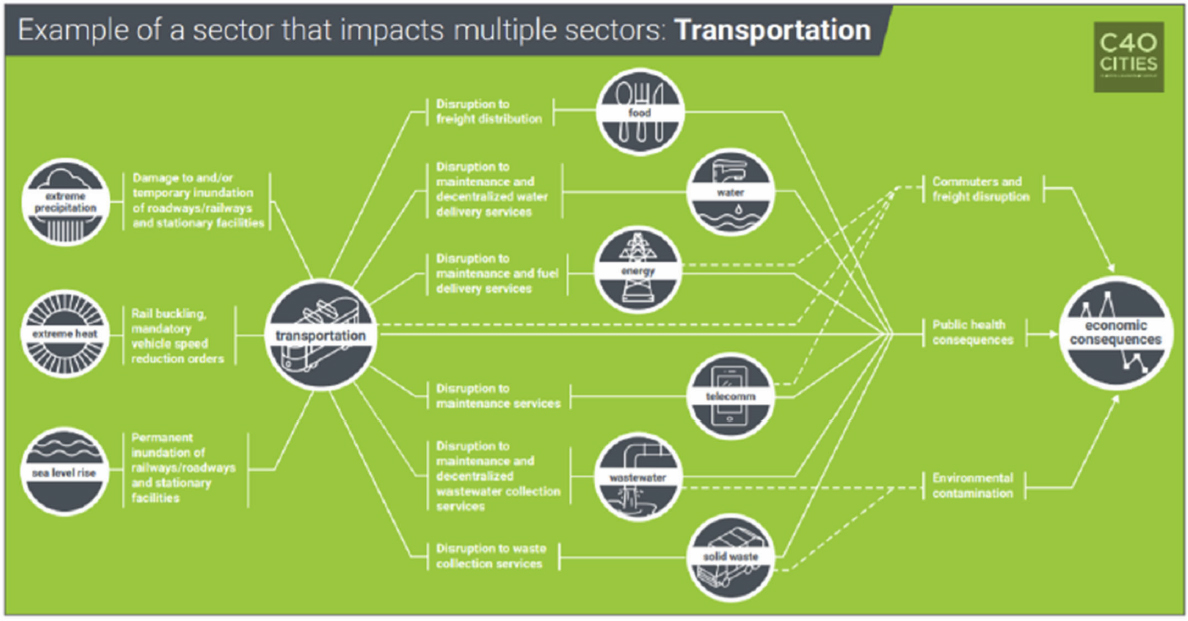

The ARC Vulnerability and Resiliency Framework for the Atlanta regions builds on the FHWA Climate Change & Extreme Weather Vulnerability Assessment Framework, extending it to focus more on transportation-related decision-making. Assessing vulnerability has primarily focused on transportation assets, as previous disasters have demonstrated that transportation network failures significantly exacerbate large-scale disruptions. This exacerbation has shown to be due

to cascading effects resulting from dependencies in the transportation system and illustrating the impact of transportation system resilience on other policy areas.

The framework was used to identify critical assets, facilities, and services in the transportation network, consider the effects of climate change on local environmental conditions, and identify vulnerabilities by scoring their exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity. The anticipation that future conditions will differ from present conditions is central to the analysis, and scenario-based forecasting is used to explore impacts under different assumptions and timescales. A combination of GIS, travel demand modeling, and expert guidance are used to make the assessment. The risk appraisal is then linked to transportation decision-making, including impact on other policy areas, such as public health, through incorporation into other planning efforts and supporting efforts by partner agencies.

Data is the greatest challenge to engaging in a resilience and vulnerability assessment, and a repository of relevant geodata must be created and populated. While existing data sources and tools can be leveraged, substantial data cleaning and correction is necessary before analysis can be performed.

The effort is part of the “100 Resilient Cities” initiative funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, which funded a “Chief Resilience Officer” position for several years in Atlanta, providing an explicitly responsible person for resilience issues and activities. While the foundation funding is not replicable, many practices and procedures pioneered by network members remain applicable in other contexts. Drawing on the experience of other agencies in applying frameworks is very important, as is the existence of formal channels for doing so.

Making the shift toward a resilience-based framework requires changing existing processes and protocols. Guidance for the framework included recommendations for incorporating it into operational processes. Further, having an explicit framework makes it possible to compare transportation policies and initiatives for conformity with resilience principles.

Keywords: risk assessment, data-driven models, institutional capacity, governance, adaptation

Description of Resilience Approach Taken

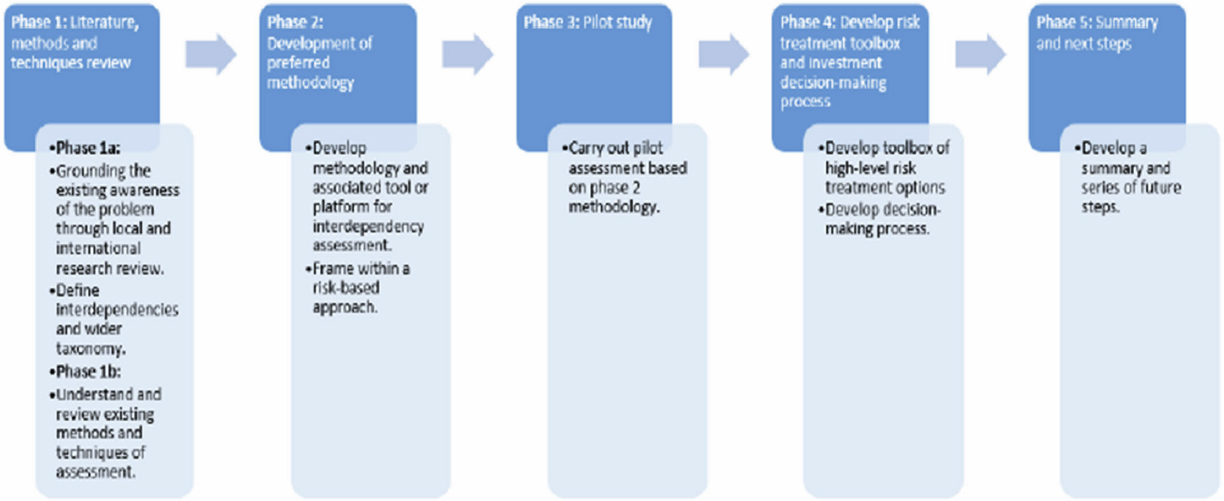

Development of a framework to: “emphasize the linkage between the results of a vulnerability assessment to the decision-making processes that ultimately define the transportation system through investments and operational changes” (Filosa et al. 2017), leading to:

- Planning goals, objectives, and performance measures sensitive to system resilience

- Comprehensive/modal plan elements in which resilience is an important system characteristic

- Project criteria that provide additional weight to projects that enhance system resilience

- Projects and strategies that enhance resilient system performance

The resilience approach taken was intended to extend the FHWA Vulnerability Assessment Framework beyond transportation system assets to include public health, safety, and economic development. Extending it beyond assets to those functions and systems depends on transportation system network resilience.

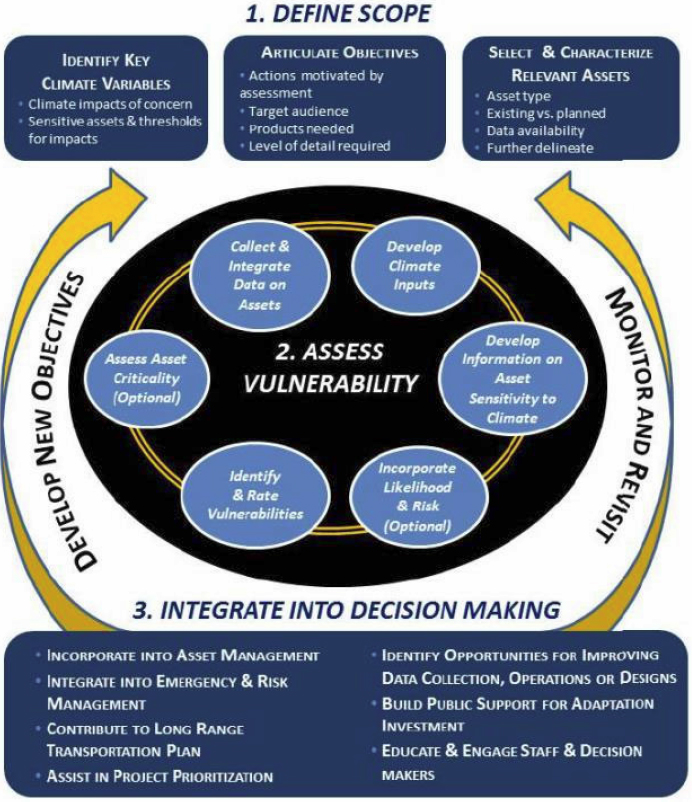

Figure 11: FHWA Climate Change & Extreme Weather Vulnerability Assessment Framework.

FHWA Framework

The FHWA framework on which the ARC’s was based was articulated as having two parts: Part 1) Defining the Scope of the Analysis and Part 2) Vulnerability Assessment. Part 1 has three steps: “1) identifying key climate variables to study, 2) articulating objectives for the assessment, and 3) selecting and characterizing relevant assets to study”; Part 2 assesses vulnerability in terms of sensitivity, exposure, and adaptive capacity (see Figure 11) (Filosa et al. 2017). Sensitivity analysis consists of identifying critical thresholds (such as height or heat tolerance) by working with asset owners. Analysis of exposure is determined through GIS. A combination of raster analysis (heat), elevation (LIDAR data), and tagging was used to identify at-risk assets or assets that had been affected by recent extreme weather events, such as flooding. The need for manual assessment and correction of data was noted. Analysis of adaptive capacity itself had three elements: impact on network function, expected downtime, and replacement costs. Network modeling was suggested to explore network vulnerability, “assumed reconstruction or restoration times are developed for different types of facilities based on previous experiences and close consultation with the asset owners’ and replacement vs. repair costs require consideration” (Filosa et al. 2017).

The framework then suggests calculating a vulnerability score for all assets, with the capacity to provide rankings across the region, analyzed in the entire region by geographic subarea, mode, asset type, or asset owner. The framework also suggested modeling vulnerability across multiple different climate scenarios (weighted more near-term conditions more heavily).

ARC Region Vulnerability and Resilience Framework

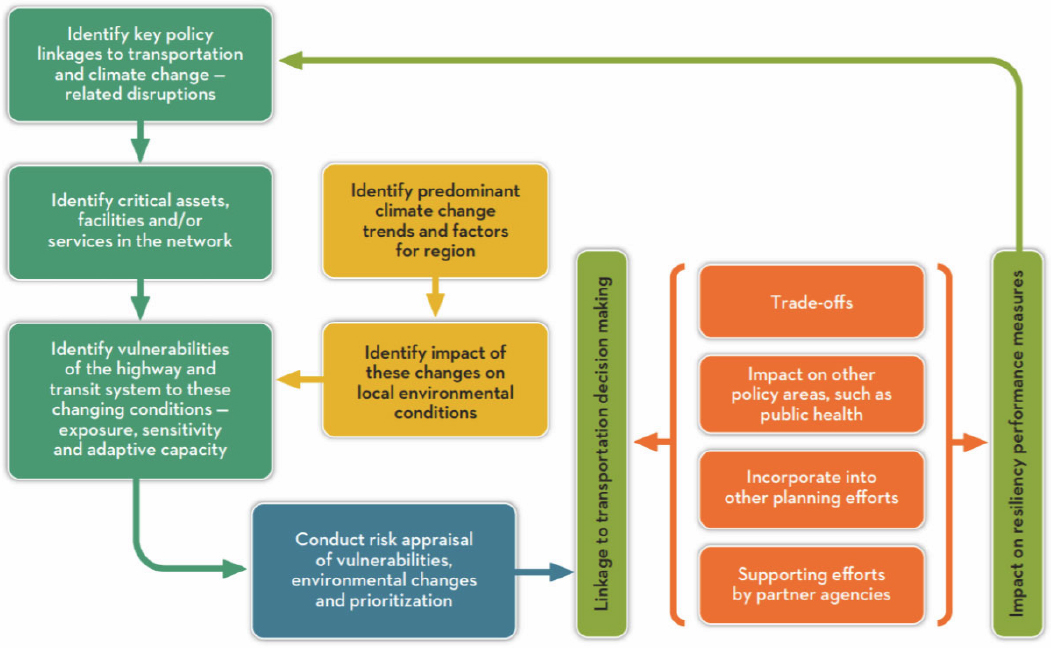

The ARC Region Vulnerability and Resilience Framework closely mimics the elements and steps of the FHWA framework but provides a more directive flow of the processes involved and greater emphasis on transportation decision-making and associated linkages. The proposed framework is visually represented in Figure 12.

Figure 12: Proposed ARC Readiness Framework.

Essential to the framework is linking risk appraisal (blue in Figure 12) to transportation decision-making (kelly green in Figure 12) and connecting it to other policy areas, supporting partner agency efforts, and incorporating it into other planning efforts.

The scope of the intended function of the resilience approach is essentially one of contingency planning, identifying what might go wrong and the necessary actions to take when things do. Its sophistication lies in methods used to assess which things might go wrong by using the universe of infrastructure present in GIS data and estimating infrastructure importance in system function.

The anticipated benefits of the approach lie in preventing potential future harms through risk reduction and readiness. A vulnerability assessment enables an agency to make appropriate investment decisions and appropriate institutional preparations by estimating both chances of failure and consequences.

Implementation costs of the ARC Vulnerability and Resiliency Framework for the Atlanta Region are difficult to assess. It represents merely the most recent phase of a process begun in 2013 as part of the “100 Resilient Cities” initiative, which included a “Chief Resilience Officer” staff position funded by the Rockefeller Institute. This initiative continued with the Transportation System Vulnerability & High-Level Risk Assessment, a specialized LRTP element funded for about $175,000 (Atlanta Regional Commission 2020). The total program has been in operation for over six years and is ongoing.

The data, computing, and analytics costs are difficult to state because much of the data and computing/analytics capacity were pre-existing within the Atlanta Regional Commission. For example, scoring the criticality of roads and bridges requires the application of an existing travel demand model. GIS capable of hydrological modeling was necessary, but the USDOT Vulnerability Assessment Scoring Tool (VAST) provides a way to assess vulnerability (Filosa et al. 2017). An essential part of the ARC Vulnerability and Resiliency Framework for the Atlanta Region was delivering a series of recommendations on necessary actions and policy changes to implement the framework. Hence, the process is ongoing, as are the tasks.

Critical Assessment of Success or Challenges of Approach

Continuation is the fundamental measure of policy success. Atlanta remains active in resilience-related research, recently selected to participate in a Growing Convergence Research project introduced by the National Science Foundation to enhance urban resilience to extreme climatic events (Georgia State University 2020). It is possible that the ARC Vulnerability and Resiliency Framework has been a successful element in the ARC region’s resilience planning efforts.

Key success factors in this approach included extending an existing resilience framework and using the FHWA framework as the base, ensuring a common understanding with state transportation agencies. The extension of the framework to locally important issues was an influential factor. Also, the development of the framework made it possible to move beyond existing paradigms, such as “reliability” and peak-hour travel-time regularity metrics, toward a framework capable of incorporating extreme events and non-standard conditions in decision-making.

The primary challenge in developing and applying a vulnerability and resilience framework lies in the data, computing, and analytics requirements. A repository of relevant geodata must be created, populated, and maintained. Analytical capacity must be obtained, either by repurposing existing capacity or finding funding for additional capacity. While an increasing amount of geodata are publicly available, most data require enrichment by additional attributes before they can be effectively used.

Replicability of The Approach for Other Agencies

The core element of the approach is developing a resilience framework, which provides an explicit frame for understanding and discussing resilience in the preparedness, response, and recovery/adaptation phases. This approach is assessed to be a replicable and practical approach.

In contrast, the funding that made this possible is much less replicable. In 2013, the Rockefeller Foundation pioneered an initiative known as “100 Resilient Cities” “to help more cities build resilience to the physical, social, and economic challenges that are a growing part of the 21st century” (Rockefeller Foundation, 2020). The “100 Resilient Cities” initiative funded 80 global cities, including several major cities in America. Atlanta applied and was selected. Program sponsorship enabled hiring a “Chief Resilience Officer” and provided access to partners, technologies, and services necessary to develop a robust resilience strategy. The “100 Resilient Cities” initiative also established a network to share resilience approaches.

However, future resilience work has been made easier by the capacity to draw upon prior work by the cities in the “100 Resilient Cities” initiative. In the near term, the Rockefeller Foundation continues to fund “Chief Resilience Officer” positions. So, it remains possible in the near term to directly contact such key persons in developing resilience frameworks (Cities Today, 2020) for organizations interested in doing so. In the long-term, two successor organizations carry on the mission: the non-profit Resilient Cities Catalyst (https://www.rcc.city) and Global Resilient Cities Network (https://www.rockpa.org/project/global-resilient-cities-network).

Some of the practices pioneered by the “100 Resilient Cities” initiative is replicable, such as creating an executive-level post (“Chief Resilience Officer”) capable of directing focus within city governance. The core of the success of the “100 Resilient Cities” initiative was networking with other cities to discover reliant approaches.

The above elements may represent a clear limit to replicability beyond the executive branch of big cities. Effective replication would require drawing on state transportation agency-relevant aspects of city operations practices, such as vulnerability assessments. To replicate the framework and associated processes, state transportation agencies can leverage document resources from city resilience networks and cities to develop their own frameworks and plans. Likely, several state transportation agencies are already engaged in resilience practices, but a coordinating entity to provide collaboration between agencies is lacking, impairing the dissemination of effective practices. The presence of a coordinating entity (the Rockefeller Foundation) and dedicated personnel (Chief Resilience Officers) was central to the “100 Resilient Cities” program. AASHTO’s Resilient and Sustainable Transportation Systems Technical Assistance Program may be able to fill part of this need (AASHTO, 2020).

Key Takeaways

Assessing vulnerability is essential to resilience and a core part of preparedness activities. Assessing vulnerability has primarily focused on transportation assets, as previous disasters have demonstrated that transportation network failures significantly exacerbate large-scale disruptions. Effective emergency response and relief require functional transportation and communication systems, because when those systems fail, the emergency response system fails.

Large-scale regional disruptions build the political will to engage in resilience activities and to privilege them. In the past decade, Atlanta has faced the worst winter storm in city history, a tropical storm, tornadoes, and flooding. Changing climatic conditions are generating increasingly extreme heatwaves and rainfall, with concomitant drought and flooding.

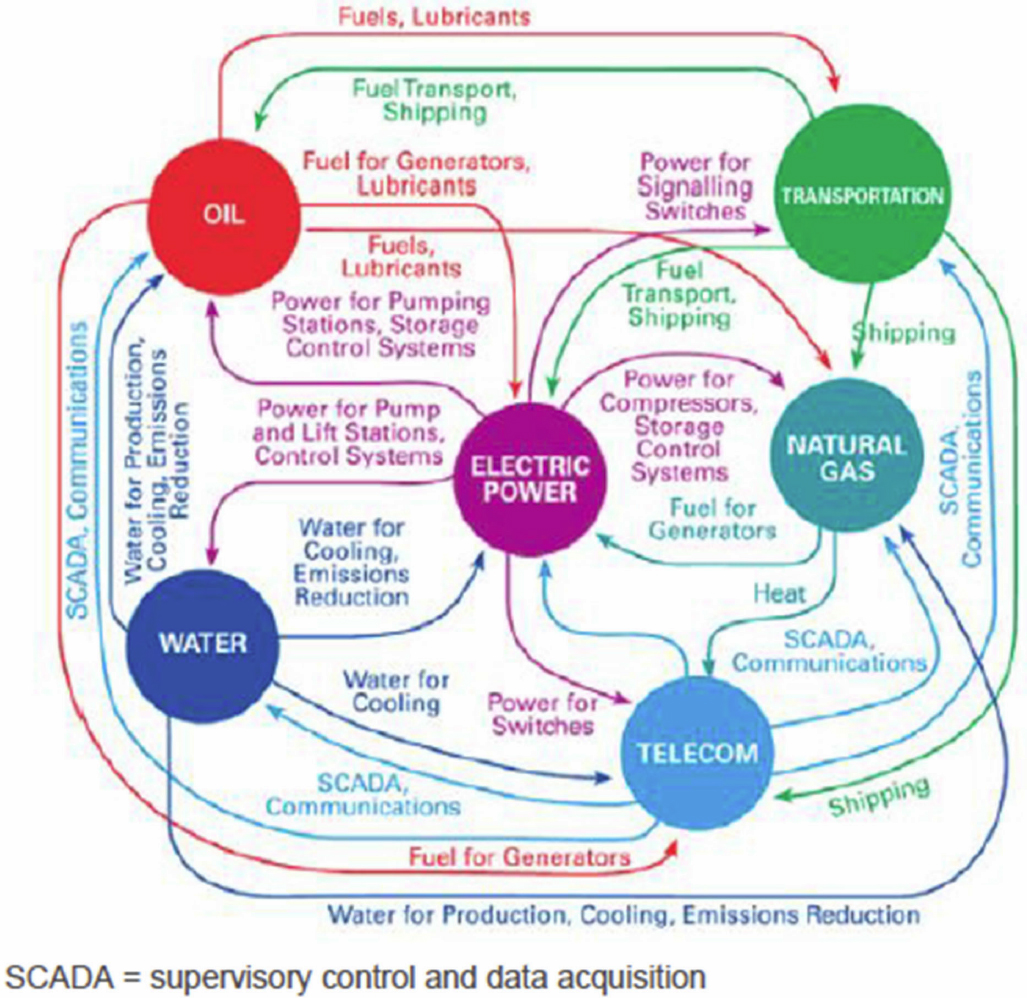

A systems resilience focus in the transportation planning process emphasizes the reliability of the transportation system rather than just efficiency. It suggests a need for safeguards to protect the transportation system and its users. A systems resilience focus considers the importance of dependencies and cascading effects in the transportation system and the implication of transportation system resilience to other policy areas. Together, this suggests the importance of institutional connections and coordination. A systems resilience focus also acknowledges change and considers future projected weather patterns in the decision-making process.

3A.2: Climate Ready Boston

Summary

The city of Boston generally takes its vulnerability to climate change seriously, especially its vulnerability to rising sea levels, and finds its existing defenses will likely be insufficient in the coming decades. The city has spent time analyzing and quantifying the risk by mapping the zones of risk and structures/infrastructure at risk and the likelihood and timescales at which those risks will occur. New conditions will generate new risks, such as new flood inflow points, and reduce existing solutions, such as high sea levels preventing outflow. Solving the problem requires public investment in both gray and green infrastructure and retrofits of private property. Even maintaining the status quo requires substantial investment, but cost-benefit analysis suggests doing so is preferable. Getting the money (federal, state, developers, investors) through financing and funding (taxes, fees, partnerships) to pay for the financing is discussed, including some novel state-specific initiatives.

Keywords: flood, sea-level rise, risk assessment, preparedness, data-driven models

Description of Resilience Approach Taken

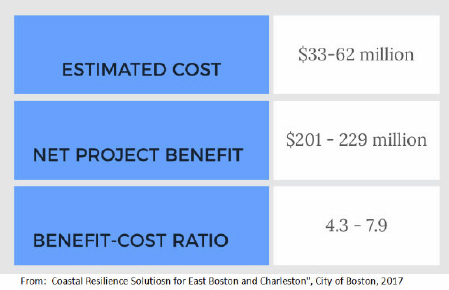

This resilience approach is best described as preparedness in a risk reduction and readiness sense. The approach intends to identify long-term risks and plan to take long-term actions to ameliorate long-term risks. The implementation cost of risk identification and making mitigation plans were minimal, with the cost of implementing the identified solutions running from a few million to half a billion dollars (City of Boston, 2016). These costs were set against the value generated by the suggested improvements, providing a rough cost-benefit analysis of risk reduction in the case of flooding, and identifying benefits to existing public infrastructure such as fire stations (see Figure 13).

In response to the challenge of climate change, including flooding, snowstorms, and hotter summers, the Climate Ready Boston initiative was intended to produce a systemic and comprehensive framework. This framework was developed working with local climate scientists, engineers, planners, and designers to identify vulnerable locations and engage in changes to promote resilience (City of Boston, 2016).

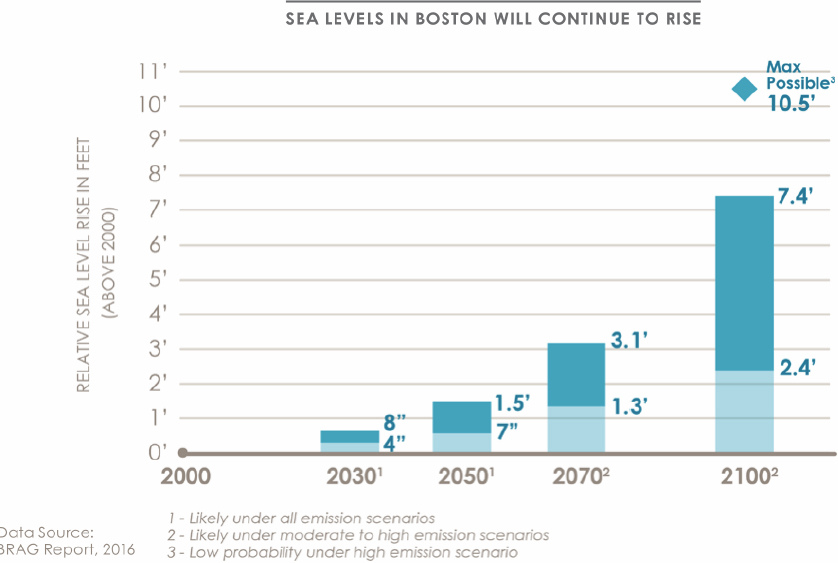

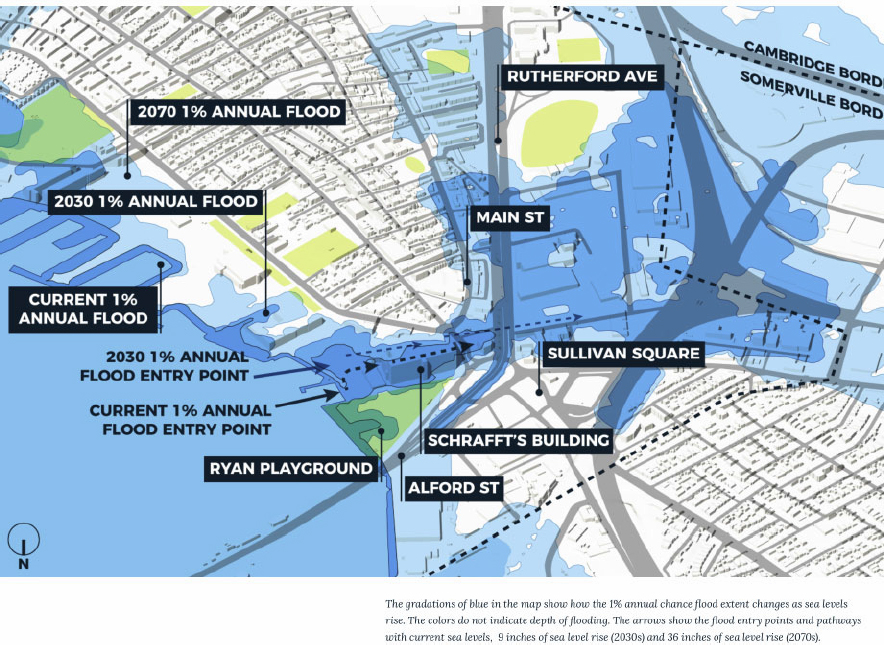

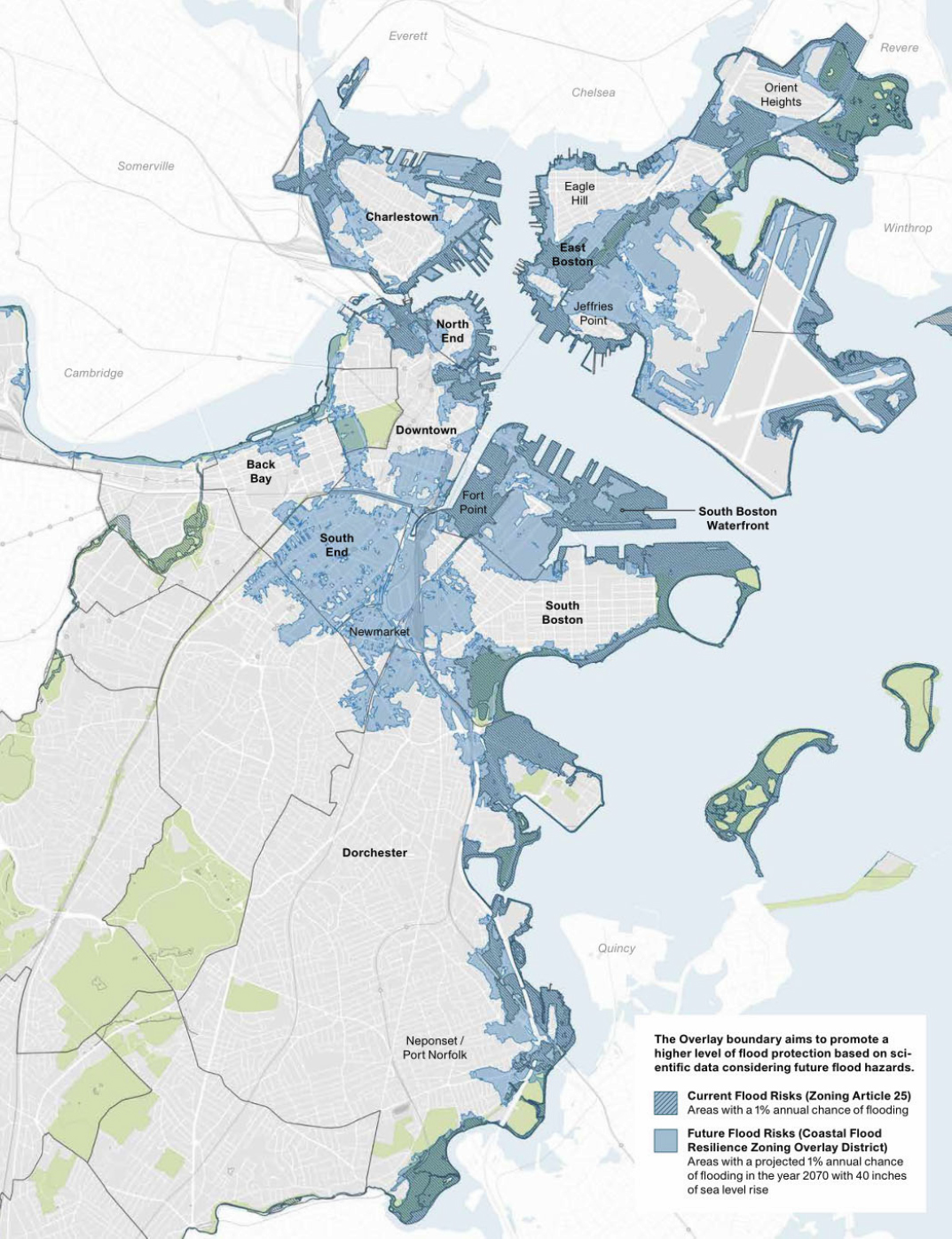

Expected impacts of climate change included increased extreme precipitation and increased sea-level rise. Climate change is generating stronger, wetter storms, resulting in higher storm surge levels on top of the baseline sea-level rise, causing additional flooding with greater frequency (see Figure 14).

Buildings and land areas thus exposed to stormwater flooding are identified and quantified for several forecast periods (2030, 2050, 2070, 2100) and mapped (see Figure 15). This process revealed that 10% of the existing buildings would be exposed to coastal and riverine flooding, 5% flooding at high tide, and 25% during severe events (City of Boston, 2017).

Climate Ready Boston developed a detailed asset inventory by combining over a hundred data sets. It also identified interdependencies between different assets and amenities, individual and systemic vulnerabilities, and existing resilience measures. Both fixed guideway transit and major roads are essential public facilities identified as vulnerable. Those that are transit-dependent were found vulnerable to disruptions to the fixed guideway transportation network (City of Boston, 2016)

Other particular vulnerabilities included rail impairment due to high temperatures and roadway buckling on asphalt roads experiencing sub-surface moisture. Stormwater vulnerability was predicted to most likely increase due to outfalls being unable to discharge because of higher sea levels, with effects concentrated in low-lying areas and areas with poor drainage. Underground transportation infrastructure was understood as special risk (City of Boston, 2016).

The planned adaptive approach is to improve flood defenses, create resilient infrastructure, and adapt existing buildings to changing conditions through local planning, mitigating flood risk, and making coordinated infrastructure investments. Providing financial, technical, and insurance assistance was also suggested. Specific initiatives included evaluating the current flood insurance market, engaging in better flood-risk ratings, and advocating for changes in the National Flood Insurance Program. Currently, insurers underestimate the risks of extreme storms and associated disruption due to communication, power, and transportation failures.

A framework of strategies and related initiatives is laid out. Resolution actions are identified as short, medium, and long-term. Suggested actions included providing temporary flood barriers, “green” infrastructure such as flood-resilience parks and amenities, and district-scale protections. Other proposed actions include education and readiness training, local planning efforts, infrastructure investment prioritization frameworks, re-zoning, and preparation of municipal buildings.

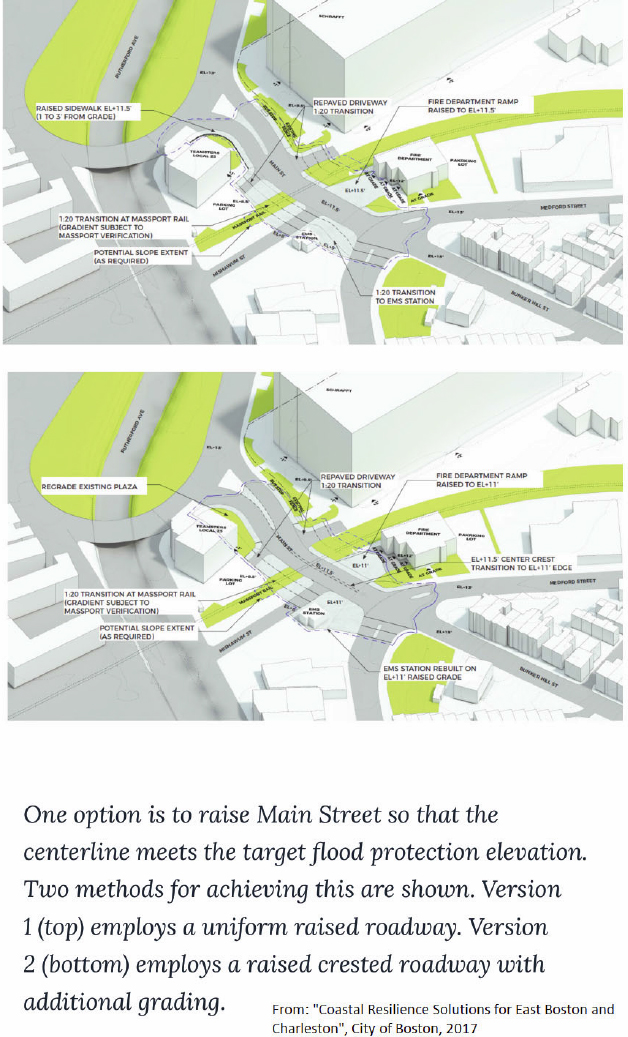

The analysis is based on focus areas, providing district-specific analysis and planning recommendations. The district-specific research also includes a written analysis of impacts and mapping that identifies flood pathways, locations, and depths and identifies vulnerabilities where existing dams/barriers could be overtopped and how the flooding of some facilities could overflow into nearby areas. The study also analyzes changes in impacts over time. For example, 0.7’ in 2030 might become 4.4’ in 2070, transforming a nuisance into a major destructive event. While reinforcing existing flood pathways is suggested, the need for new infrastructure is diagnosed when estimated rising sea levels show new, additional flood pathways being created. Planned actions include elevating small sections of some roads in partnership with the state DOT. Long-term needs suggest a new system of elevated parks and walkways to provide new open space and waterfront access to create sufficient elevations along the shore to act as barriers to predicted 2070 sea levels. Activities in combination with private development are suggested as a funding mechanism. Bunding with scheduled improvements to parks and roadways is also recommended. Potential design solutions were detailed (see Figure 16). Regulatory changes to zoning, coastal zone management, and other regulatory tools were also suggested (City of Boston, 2017).

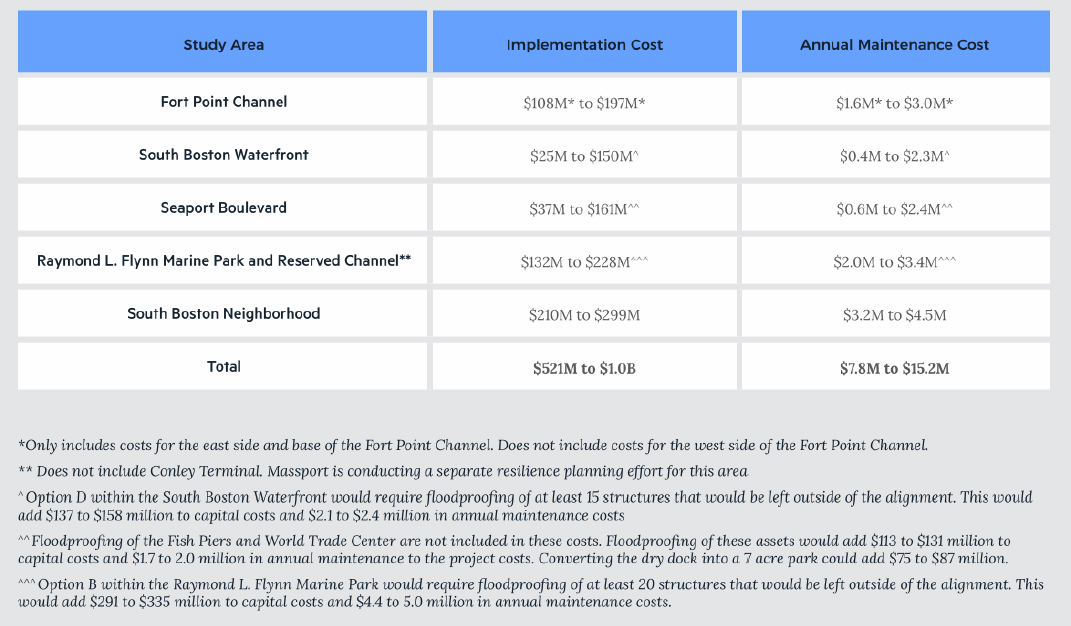

Analysis was done iteratively, with different districts done in different years and providing different outputs for different districts. A later implementation provided annual maintenance costs associated with improvements (see Figure 17) (City of Boston, 2018).

Some proposed investments, such as a harbor barrier, run into billions of dollars, with expected completion timelines after 2050.

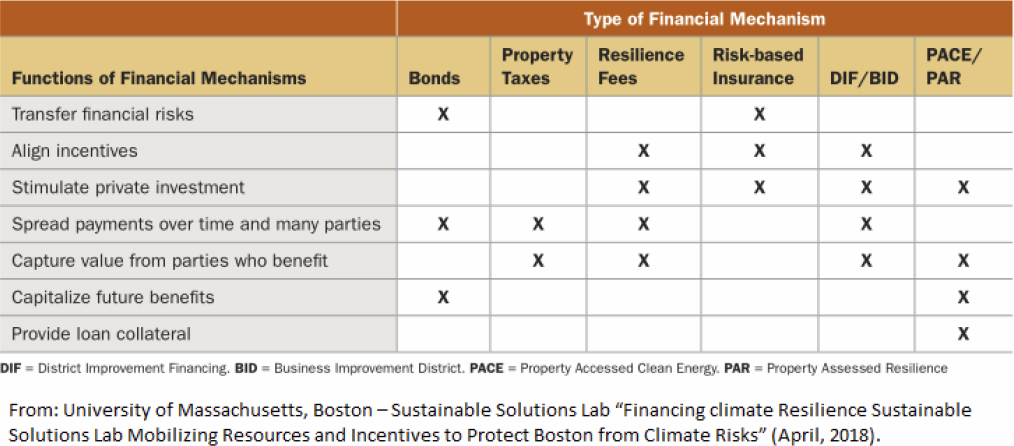

Further analysis extends the definition of resilience beyond risk reduction to include improved emergency response and disaster recovery capacity by ensuring the reliability and continuity of essential services, government agencies, and critical businesses. It also includes pre-distancing financial preparation through insurance or catastrophe bonds. Catastrophe bonds, paying out a set amount when set conditions are met, ensure against risk, trading a stream of payments against a potential windfall in a disastrous situation. Other financial mechanisms considered include bonds, tasks, fees, insurance premiums, District Improvement Financing, Business Improvement Finance, and assessed fees/tax on resilience (see Figure 18) (University of Massachusetts, Boston 2018).

Further suggestions also included revenue-backed bonds using money from local open-space funding initiatives, increased gas taxes, and funding from a Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, district-level financing regimes making use of tax-increment financing, and Business Improvement Districts. More novel recommendations include a “District Resilience Improvement” apportioning assessment based on risk and property value and negotiating funding from non-property tax paying entities such as utilities and transit providers. The potential was identified for establishing a stormwater utility charged with providing stormwater service, collecting a fee as a surcharge on water/sewer billing in proportion to runoff generated, within mitigating reductions for green infrastructure or on-site retention. Community Facilities Districts in California are suggested as a model. The Infrastructure Investment Incentive Program, a Massachusetts-specific program, provides funds from RDA bonds during construction for private development and then relies on local assessments to repay the bond. This arrangement is highly suitable for developing infrastructure associated with new development.

The use of “linkage” fees is suggested for parcel/building level financing by first mandating infrastructure associated with development but permitting payment into a linkage fund instead of their direct provision. Boston currently uses such a system to fund affordable housing. “Green Bonds,” such as those issued by Connecticut Green Bank, offer zero-interest loans for energy-efficient upgrades, repaid through a small surcharge on future electricity bills, thus providing retrofit capacity to persons and organizations otherwise lacking in financial ability (Wong, 2019). Connecticut also offers the Shore Up CT program, providing home retrofit loans to elevate homes in danger of flooding. Property Assess Clean Energy (PACE) has been used to finance energy retrofits, with repayment ensured through a lien on the building. It is identified as being suitable for multifamily properties or community development corporations. Adapting such arrangements to “Property Assessed Resilience” has occurred in Florida and San Francisco, CA. In California, “Community Facility Districts” offering non-FEMA insurance for perceived over-priced risks have been suggested, matching the insurance with fees to provide premiums.

FEMA provides flood insurance to many jurisdictions but underprices risk to maintain affordability (Wong, 2019). However, it provides a mechanism for communities to obtain lower premiums (up to 45%) by engaging in activities that reduce flood risk for public information and mapping, zoning and building regulation, flood damage reduction, improved drainage systems, floodplain management, and other activities. Only a small fraction of communities participates in this program.

As addressed previously, catastrophe bonds, paying out a set amount when set conditions are met, ensure against risk, trading a stream of payments against a potential windfall in a disastrous situation. The Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) of New York maintains a fire and earthquake bond to guard against storm surges and earthquake events. Another insurance-like bond known as a “contingent bond” transfers project underperformance risk to outside investors, providing a hedge in case projects intended to improve resilience fail.

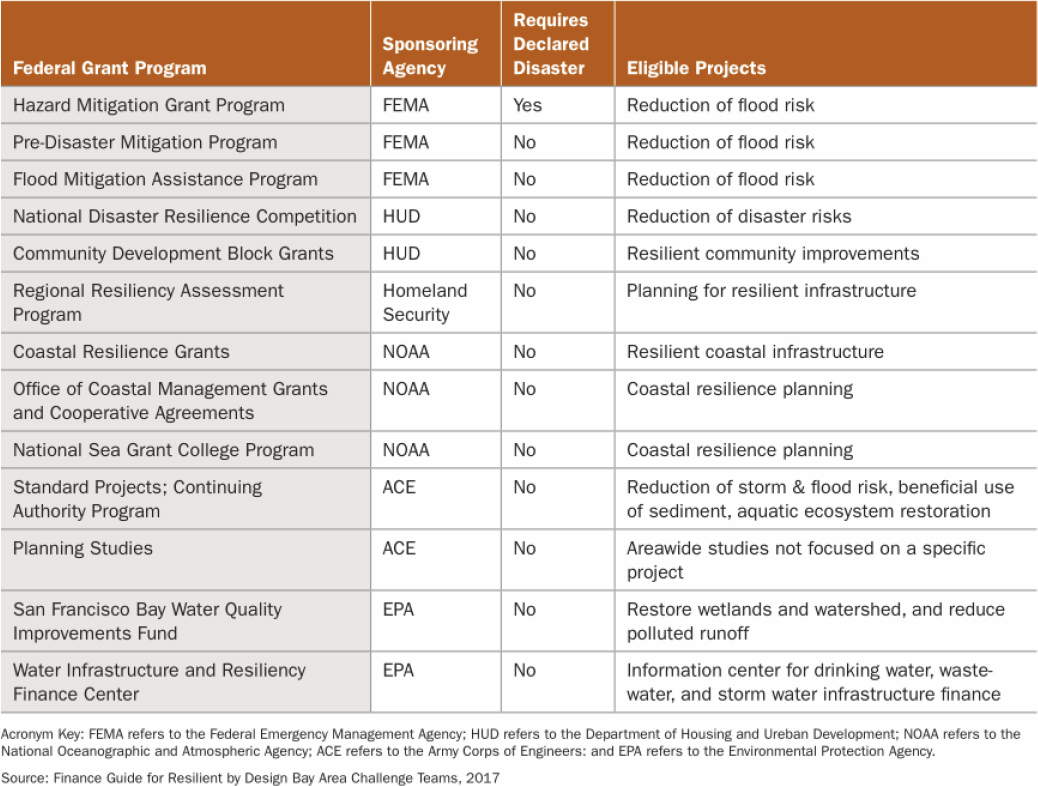

Numerous federal programs offer grants or funding for risk reduction activities detailed in Figure 19 (Resilient Bay Area, 2017).

Critical Assessment of Success or Challenges of Approach

Climate Ready Boston seems to be an effective program for identifying and quantifying risks associated with sea-level rise, coming up with solutions, making plans to implement them, and identifying potential actions necessary. It offers an effective and practical blueprint other communities can follow while engaging in their resilience planning. The approach also uses scenario-based forecasting, providing high-medium-low impact scenarios to assess the bounds of best-case, worst-case, and median outcomes rather than using a single average value for forecasts. The program assesses what is likely to flood, how likely it is, and the costs and benefits of preventing it.

The primary limitation of the approach is that it is primarily a scoping activity, identifying potential actions rather than a planning and implementation process designed to effect change actively. However, this is a reasonable and almost inevitable limitation, given the scale (both temporal and spatial) of the major infrastructure investments necessary to retrofit a small low-lying seaside community to the challenge of sea-level rise. Also, in accordance with the scale, the approach focuses on prioritizing infrastructure investments and matching them with a timescale when needed. For example, half a foot of flooding in 2030 may not require a major multi-billion-dollar harbor barrier, while a four-foot rise in 2070 likely will. The approach also recognizes that the necessary infrastructure will be expensive and provides alternatives for financing the construction and potential novel funding resources available to different levels of government.

In implementation, timing is essential. One theme throughout the report is local floods or disasters occurring either recently or within living memory, emphasizing their potential to increase in severity or frequency. Another theme is the harm of failing to act and how existing infrastructure or structures might be compromised or damaged, resulting in preventable repair costs.

Climate Ready Boston represents a substantial investment in analytic capacity to determine risks and readiness. However, it also represents an investment in brainstorming, presenting potential solutions, and providing cost estimates for those solutions. This investment implies several hundred thousand dollars in either staff or consultant time for analytics and presentation of the results for data assembly and computing, as well as leveraging existing partnerships with educational institutions. The challenge in implementing this approach lies in obtaining or constructing the institutional relationships and technical capacity necessary to carry it out in an effective way. This challenge may make the method unsuitable for application outside major metropolitan areas. The geographic scale of analysis would also likely sit poorly with state transportation agencies attempting to provide coverage of their entire jurisdiction rather than topical and context-dependent application to a limited number of small areas. Figure 20 shows the general area of analysis, including sub-areas. (Boston Planning and Development Agency, 2010).

Replicability of the Approach for Other Agencies

The modeling approaches used to identify locations with increased vulnerability to flooding due to sea-level rise can be replicated using existing GIS tools. Identifying low-lying areas prone to flooding and future inflow points provides an alternative mechanism to FEMA flood maps, which identify only present flood conditions and cannot evaluate future flood risk resulting from changed conditions.

The replicability of the climate resilience funding/financing revenues proposed in a different context is variable. Some funding/financing options are specific to Massachusetts or the city of Boston. Others rely on institutional capabilities unique to Boston or Massachusetts (such as MIT and grants from wealthy family foundations) that are difficult to duplicate.

However, much of the work was accomplished through contracts with private consultants, further matched with in-kind services from the Boston Planning Department and the Boston Environmental Department. The project steering committee included a traditional mix of city departments, nearby cities, and transportation agencies (DOT, Port Authority, Tolls, Transit). It also included many non-governmental organizations and neighborhood associations that helped engage with stakeholder communities. Jurisdictions would need to build working relationships with similar organizations ahead of time or stimulate the creation of such organizations to leverage such a resource

Regarding state-specific assets, the basis of the Climate Ready Boston analysis identifying the flood pathways in East Boston and Charlestown is the Boston Harbor Flood Risk Model developed by the Massachusetts Department of Transportation. The asset is replicable using existing GIS tools but requires specialized knowledge and skillsets. The analysis also leverages graduate student work from at least two institutions (MIT and UMASS Boston). The capacity to generate specific solutions for identified climate risks is impressive but requires substantial resources. While not suitable for all jurisdictions, the course of action undertaken by Boston offers lessons for other major metropolitan areas. The resources developed for Boston to explain funding and financing options can be applied elsewhere, even if at a lower level of sophistication or reduced scale if needed. It is worth noting that developing coastal resilience solutions for Boston is an iterative process, done across multiple districts over time rather than region-wide, hence reducing peak effort, ensuring that deliverables remain timely, and allowing for learning to occur throughout the process.

Key Takeaways

Effective resilience planning requires effective risk assessment of previous and newly emerging risks based on changing conditions. Risk assessment also requires systemic and contingent risk assessment to evaluate the consequences of system failure, and the spillover impacts as one system affects another. The level of specificity needed to do so effectively forbids a region-wide or even citywide application of the methodology. The case shows the value of an ongoing campaign of risk assessment for different communities, carried out incrementally not to overwhelm staff capacity or exhaust participating partners. The use of quantitative metrics is also found to be a key success factor. Effective implementation requires a combination of building risk reduction into ongoing maintenance activities and new infrastructure investments to defend existing development. Inevitably, this requires retrofitting of both public infrastructure and private property.

In some cases, private funds can be leveraged for the former through public-private partnerships. In other cases, public financing can be used for private benefit through bond and loan programs. In many cases, the financial capacity to fund retrofits is limited due to a low return on investment, and the cities may need to profit on loans in the form of reduced risk. While the majority of actions suggested relating to risk reduction, risk reduction can be considered a pre-emptive form of damage mitigation, reducing harm and disruption in the event of a disaster and thus speeding recovery in a post-disaster context.

3A.3: Cyberattack Disruption Case Study

Summary

“COPENHAGEN– Shipping giant A.P. Moller-Maersk, which handles one out of seven containers shipped globally, said the Petra cyberattack had caused outages at its computer systems across the world on Tuesday.” (Reuters - June 27, 2017)

“Texas struck by two ransomware attacks in one week - The Texas Department of Transportation was hit with a ransomware attack last Thursday, marking the second ransomware incident on a state agency in less than a week.” (TechTarget – May 18, 202)

Cyberattacks disrupt private or government infrastructure by gaining and controlling information technology (IT) systems. Cyberattacks are a growing threat to transportation infrastructure networks increasingly managed and linked through technology. The 2017 NotPetya attack on A.P. Moller-Maersk was estimated to cost the company $200 - $300 million affecting not only its container shipping but also tugboat operations, oil and gas production, drilling services, and oil tankers. The attack has now been traced to the Russian military, costing the European subsidiary of Fed Ex, TNT Express, approximately $400 million, and the pharmaceutical giant Merck over $800 million. A White House assessment put the total cost of the NotPetya attack at roughly $10 billion in damages (Wired, 2018).

More recently, Texas state government networks were attacked. In August of 2019, IT systems for the state’s court system, TxDOT, and over twenty city governments were hacked over two weeks. Louisiana schools and the city of Baltimore also reported cyberattacks in 2019. Cyberattacks can be conducted by individual hackers, foreign governments, or hostile state actors. The research identified two prevailing types of cyberattacks that can affect transportation networks.

- Ransomware attacks use malicious software to disable networks, shutting down IT systems until a ransom is paid, and the motivation is usually financial gain.

- Malware attacks use software specifically designed to disrupt, damage, or gain unauthorized access to a computer system and are most often motivated by the desire to cause chaos, usually for political gain.

In the case of the NotPetya attack, Maersk initially reported that the attack included a ransom to be paid in Bitcoin. Maersk did not pay the ransom, and it was later discovered that the damage done by NotPetya was irreversible. Security experts believe the true motive was to

target anyone doing business with Ukraine, using malware distributed via a popular tax accounting software.

The in-depth review of the 2017 NotPetya attack by Wired Magazine concluded that “the most enduring object lesson of NotPetya may simply be the strange, extra-dimensional landscape of cyberwar’s battlefield.” Cyberattacks do not conform to traditional geopolitical boundaries. While most cyberattacks have been terrestrial, the potential exists to target satellite communication systems, which could have huge implications for transportation networks, including impacts from disabling GPS and cell phone networks.

At a recent cyber fraud conference, the head of Maersk’s cybersecurity unit emphasized that both internal and external communication remain one of Maersk’s biggest challenges. The company took the stance of being entirely open and honest with customers about the NotPetya attack. The company was praised for its willingness to communicate quickly and reliably, providing updates at regular intervals via its social media channels to keep customers and investors informed.

Keywords: cybersecurity, cyberattack, network

Information Sharing Analysis Centers- A Broad Communication Response to Cyber Threats

Information Sharing Analysis Centers (ISACs) are a U.S. strategy against cyber threats organized by industry to facilitate information sharing between public and private sector groups. ISACs help critical infrastructure owners and operators protect their facilities, personnel, and customers from cyber and physical security threats and other hazards. ISACs collect, analyze and disseminate actionable threat information to their members and provide members with tools to mitigate risks and enhance resilience.

There are 24 ISACs organized under the National Council of ISACs, of which four are specifically centered around the transportation industry:

- Surface Transportation, Public Transportation, and Over-the-Road Bus ISAC

- Aviation ISAC

- Maritime ISAC

- Maritime Transportation System ISAC

In addition, a multistate ISAC is dedicated to disseminating information to state agencies in general. An ISAC specific to state department of transportation operations was not identified.

American Trucking Association

The American Trucking Association (ATA) participated in an interview to discuss an ISAC it led. Ross Froat, Director of Technology and Engineering Policy at the ATA said the trucking industry had not seen any specific pattern regarding who may be the target of an attack. The ATA has developed Fleet CyWatch, which works with other ISACs like the Surface Transportation, Public Transportation, and Over-the-Road Bus ISAC. However, one must be a member of ATA to join CyWatch.

It is prudent for state departments of transportation to develop their own ISAC, especially in the emerging Connected and Automated Vehicle (CAV) environment. As transportation networks use technology to become more sophisticated and efficient, they also become more vulnerable to cyberattacks.

AP Moller-Maersk

AP Moller-Maersk is one of the biggest shipping companies in the world, controlling around 25% of the world’s shipping capacity. It operates 800 seafaring ships out of 343 ports serving 121. On June 27, 2017, the Maersk network was hacked. Maersk computer screens froze, and a message in red and black lettering appeared. Some messages read “repairing file system on C:” warning operators not to turn off the computer, while others read “oops, your important files are encrypted.” The hack affected computers across Asia and Europe, and the perpetrators demanded $300 worth of Bitcoin to decrypt the files.

The malware used in the attack was developed as a disk-wiping cyber weapon by the Russian military and assisted by a leaked version of the NSA’s EternalBlue hacking tool. Eventually, it was determined that NotPetya’s target was not actually ransom but businesses in Ukraine. However, the malware quickly got out of hand and soon spread worldwide, taking down networks and causing billions of dollars in damage and lost revenue.

Impact on Maersk

The NotPetya cyberattack on Maersk,

- Destroyed nearly 49,000 company laptops,

- Destroyed all print capability and rendered file share as unavailable,

- Disabled its entire network of VoIP phones,

- Destroyed 1,000 applications and rendered 1,200 inaccessible,

- Destroyed 3,500 out of 6,200 servers, and

- Cost the company $250-$300 million.

Maersk Reaction and Remediation

As soon as the attack was confirmed, the company’s IT staff immediately ran into employee offices, telling them to turn off computers or disconnect from the network. It took more than two hours to disconnect Maersk’s entire global network. The company identified servers in Lagos, Nigeria, which had not been connected to the global network due to a local power failure. These servers were carefully transported to world headquarters in Denmark, and the organization’s directories could be recovered from there.

Senior leadership at Maersk decided to be as transparent as possible about what had happened. Using the clean software from the servers in Nigeria, IT teams moved quickly, using reverse engineering, to design and build new machines more resilient to cyberattacks. The company quickly built 2,000 new laptops within nine days of the attack by using this technique, and after four weeks, all 49,000 laptops had been rebuilt.

Description of Resilience Approach Taken

The concept of ISACs was introduced and promulgated under Presidential Decision Directive-63 (PDD-63), signed May 22, 1998, after which the federal government asked each critical

infrastructure sector to establish sector-specific organizations to share information about threats and vulnerabilities. There are 24 ISACs organized under the National Council of ISACs, including a multistate ISAC dedicated to disseminating information to state agencies. There are ISACs centered around the transportation industry:

- Surface Transportation, Public Transportation, and Over-Road-Bus ISAC,1

- Aviation ISAC,

- Maritime ISAC, and

- Maritime Transportation System ISAC.2

Information Sharing and Analysis Centers (ISACs) help critical infrastructure owners and operators protect their facilities, personnel, and customers from cyber and physical security threats and other hazards. ISACs collect, analyze and disseminate actionable threat information to their members and provide members with tools to mitigate risks and enhance resilience.

ISACs have successfully provided operational services that protect critical infrastructures, such as risk mitigation, incident response, and information. Other ISAC services include annual meetings, technical exchanges, workshops, and webinars.

Most ISACs have 24/7 threat warning and incident reporting capabilities and may also set the threat level for their sectors. Many ISACs also have a track record of responding to and sharing actionable and relevant information more quickly than government partners.

Key Takeaways

Because there is no “zero cyber risk environment” cyber security planning is shown by the case to be essential for sustaining network operation and security. In the case, it is clear that prevention and early detection is the most effective counter-measure for a cyber-disruption. The case also points to the importance of Privileged Access Management (PAM) to vital systems. PAM is a system that manages all the system access/restriction within existing active directory in a company. Unlike a superuser scenario, where a user (system admin) who has all the access, this system forms a layer between any user and his capability to access all the servers. for instance, the individual entities in the network can have a separate password and PAM will manage those, thus in case if the superuser credential is compromised the attacker does not have access to all servers and networks. A staff member points out that “Had Maersk have PAM, the impact would have limited to 5000 computers, not 55,000.” Other key findings point to the importance of regular cyber security risk assessments and coordination between state, regional and private sector partners in monitoring and reporting disruptions.

__________________

1 The ATA has developed Fleet CyWatch that works together with the SURFACE TRANSPORTATION, PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION AND OVER-THE-ROAD BUS ISAC. However, you must be a member of ATA to gain access to participate.

2 Maritime ISAC is focused on maritime security and Maritime Transportation System ISAC is focused on cybersecurity within the maritime industry.

3A.4: EPA / Rhode Island Community Planning Framework

Summary

“Planning Framework for a Climate-Resilient Economy” is a report from the U.S. EPA which includes input from the state of Rhode Island (RI). It develops a framework for planning for resilience, and the report gives local governments and stakeholders guidance concerning how to develop and implement this planning framework.

Throughout the document, examples and applications for North Kingstown, RI, are presented. Planned implementation in North Kingstown was sidelined by the election of a new Town Council. But numerous other examples from all over the U.S. are included. The framework is oriented toward the entire local economy, discussing planning and projects for transportation facilities and economic components such as commercial establishments and utilities.

This framework will likely be useful to localities looking to initiate or improve climate resilience efforts, and it is suggestive of how major stakeholders can work together. In most cases, the planning framework will not have a dedicated funding source, nor is the framework currently required by federal or state law. However, it provides guidance for handling threats that may become more serious in the coming years.

In terms of assisting the application and success of the planning framework, federal and state governments may be able to do more by documenting and tracking the success of such local efforts throughout the country. Federal and state governments may also help local efforts by providing technical assistance with GIS analysis, climate modeling, and other information technologies.

Keywords: land use, recovery, climate change, FEMA, drought

Description of Resilience Approach Taken

“Planning Framework for a Climate-Resilient Economy” (EPA, 2016) helps communities prepare for and mitigate major setbacks from natural disasters. It is intended to help local government agencies, businesses, and non-profits plan, prepare and coordinate their efforts in the face of various climate-related and natural disaster threats. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Office of Sustainable Communities developed the framework. Evidence of climate change and the threat of increased climate change motivated the project.

To assure the framework’s applicability to communities, the EPA worked with the Rhode Island Division of Planning and the town of North Kingstown, RI. The report explains how the framework was developed and applied in North Kingstown. Examples are also provided for many other localities, such as Chapel Hill, North Carolina, and Bethesda, Maryland.

The framework is oriented toward economic resilience and emphasizes maintaining and even increasing economic activity as measured by gross domestic product (GDP), jobs, and property values. Developing the framework requires close cooperation between public agencies and private businesses.

Transportation is identified as a critical economic component, along with utilities, industry, commerce, agriculture, and natural resources. The report points out that some communities address their vulnerability to floods in their local hazard mitigation plan, which is required for certain Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) grants (FEMA,2020). Where such plans exist, they will be informative sources for developing a climate resilience planning framework.

The report also points out that the framework can be applied more qualitatively or quantitatively. A qualitative approach would rely on existing maps, published data, and available knowledge to assess vulnerabilities, potential destruction, and damage from natural disasters. A quantitative approach would use GIS and other software to evaluate vulnerabilities and generate more specific numerical estimates of potential destruction and damage.

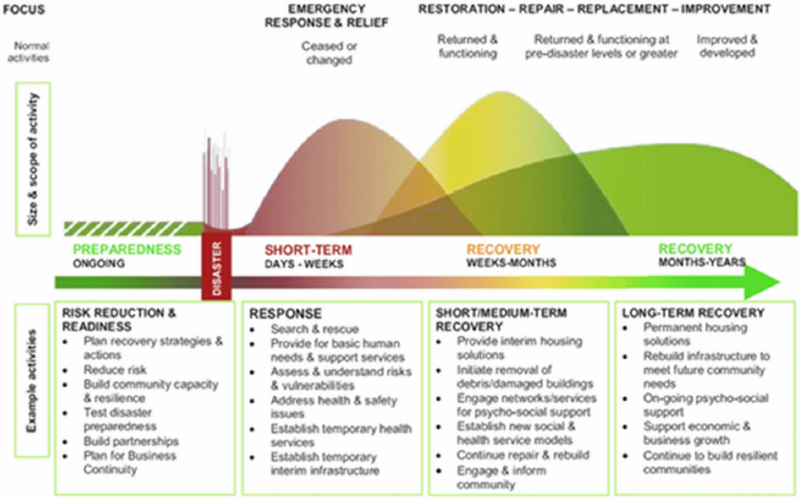

The framework encompasses all the major phases of the resilience cycle, including Preparation, Emergency Response, Short-Term Recovery, and Long-Term Recovery. Most communities are not currently experiencing a disaster nor grappling with immediate consequences of one. Therefore, preparation and protection motivate most of the steps in implementing the framework. Effective implementation requires public involvement, including presenting the framework and receiving community feedback to ensure buy-in.

The framework is oriented toward opportunity as well as protection. As climate threats increase, societal needs and economic systems will likely change. With this potentially dramatic set of changes, many communities may find opportunities to develop new products and services and generate economic and demographic growth as they adapt. For example, an office building in Miami improved its competitiveness by reducing its vulnerability to flooding and wind and guaranteeing electric service.

The framework provides for a specific set of actions, organized into five steps:

- Organize

- Evaluate Projected Climate Change Impacts and Hazards

- Identify Community Assets and Their Vulnerability

- Analyze Overall Economic Implications

- Explore Options to Enhance Resilience and Pursue Opportunities

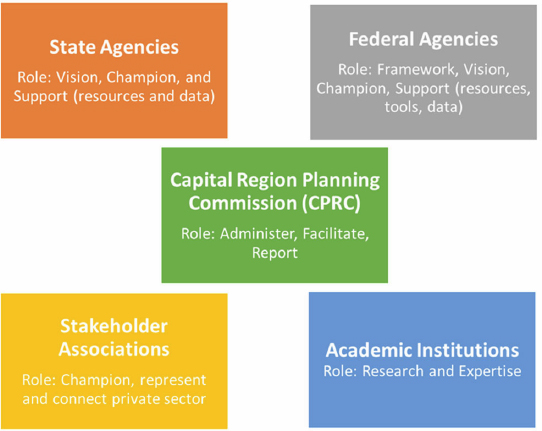

The first step, Organize, is critical for any organization or coalition that decides to apply the framework to strengthen their community. Most typically, a city or county department would lead the effort, but any number of arrangements are possible. This step is broken down into three objectives, 1) establish the assessment team, 2) geographically define the community of interest, and 3) set objectives.

The assessment team should include needed public and private stakeholders and have the technical and managerial expertise to complete the assessment. Sometimes, the community may be defined by city or county boundaries. However, in other cases, it may be practical to customize the area of focus because of a desire to include particular infrastructure, populations, or natural resources in the process. Finally, it is essential to have specific and attainable objectives, including a date for completion, because attempting to do more than can

be accomplished effectively may result in poor results and frustration on the part of the stakeholders.

The second step, Evaluating Projected Climate Change Impacts and Hazards is broken down into three objectives, 1) select climate change scenarios, 2) assess hazards (quantitatively or qualitatively), and 3+) select a method for spatial analysis.

The selection of climate change scenarios is primarily determined by the community’s climate and geographic setting, and area-specific scenarios are available from the National Climate Assessment and other sources. Once the scenarios are established, it is necessary to identify and specify specific hazards. Different areas will have concerns about sea-level rise, drought, tornadoes, extreme heat, or other contingencies. Spatial analysis can project which specific lots and other geographic features have the highest vulnerability. Using a more sophisticated tool, such as the Hazus model or GIS software, permits more quantitative estimates of destruction, damage, and other harms, such as the degradation of drinking water.

The third step, Identify Community Assets and Their Vulnerability, involves converting potential physical harms identified in step two into economic and social consequences. This decisive step entails four sequential objectives, 1) develop an economic assessment methodology, 2) identify community assets at risk, 3) define and apply a local vulnerability scale, and 4) assess potential impacts, negative or positive, on economic activity. Equity could also be considered using a fifth objective, weighting environmental justice issues in the vulnerability ratings, giving a higher score to adverse impacts disproportionately affecting disadvantaged communities.

The third step description features a table laying out the primary methodology. This table includes 25 categories of assets and seven climate-related threats and provides information for North Kingstown as an example. The 25 assets are classified into five categories: Transportation, Industrial Areas, Commercial Areas, Agriculture/Fisheries, and Natural Resources. Most specific assets, such as Roads, Annual Crops, and Wetlands, are still fairly broad. However, Commercial Operations are defined as more specific sites, usually within a radius of 300 feet or less. The categories of climate-related threats include inland flooding, wind damage, and drought.

In the North Kingstown example, vulnerability for each cell in the table is rated High, Moderate, Low or None. Of 175 cells, about 37 are rated High (some of the vulnerability ratings are Moderate/High hybrids or designated High for coastal facilities). These high vulnerability cells include Bus Service in a Blizzard, Waterfronts Facing Sea Level Rise, Commercial Operations Vulnerable to Wind Damage, Agricultural Operations Vulnerable to Flooding, and Coastal Natural Resources Exposed to Storm Surge.

An important question in step three is how much effort and other resources can be applied. Implementation can vary regarding the amount of labor, technical tools, and specialized analysis required. An example of an increased labor effort would be finding and checking most employers and commercial establishments in the study area. If technical expertise is available, it can be used to apply GIS, Hazus, or statistical software to develop more comprehensive and quantitative data.

The fourth step, Analyze Overall Economic Implications for the Community, is a less resource-intensive step. However, it is important to go beyond cataloging impacts on individual assets and to consider the community as a whole. Three applicable objectives are 1) estimate effects on the overall business climate, 2) analyze effects on real estate values and residential areas, and 3) consider interactions between public and private sectors during the recovery period. The report recommends some effort to fulfill each of these three objectives.

Analyzing the effects of a climate disaster on the overall business environment could entail the impact of one major business’ potential failure on smaller companies or the effects of a disaster on financial factors, such as the availability of capital and insurance. The impacts on real estate and residential areas to analyze could include the estimated number of residents leaving the area in the wake of a disruption and adverse effects on residential property. Finally, effects to consider regarding public-private interaction include adverse effects on municipal revenues and developing a consensus concerning rebuilding strategies.

Step five, Explore Options to Enhance Resilience and Pursue Opportunities, is the culmination of the framework, and its results should influence the plans and budgets of each locality. The specific processes and documents may vary across states or particular municipalities. This step can be broken down into two distinct objectives, 1) raise public awareness and garner support, and 2) identify actions.

Raising public awareness should flow from providing public access at the beginning of the process and throughout the previous steps. Public interest in, and support for specific actions and coalitions to develop the resilience program, is necessary to achieve implementation.

The essential goal of step five is to identify actions to enhance economic resilience and pursue opportunities. This process enables the transition from planning to actions that will pay off in case of a climate-related disaster. Efforts to help businesses take advantage of climate-related opportunities can pay off as national and global economies change in response to climate change as adverse events don’t have to hit locally for climate readiness to improve competitive position.

Most of the options to identify actions can be placed into seven categories:

- Facilitating the physical movement of businesses, public facilities, and residences to more resilient and safer locations,

- Floodproofing and stormwater management,

- Using renewable energy and resilient energy equipment,

- Ensuring and improving supply chains to eliminate or minimize disruption in the case of disaster,

- Developing multimodal transportation options to enhance resilience for commuters and emergency response,

- Projects for energy and water utilities to improve their ability to respond to adverse events, such as drought for water utilities and a variety of supply disruptions for energy utilities, and

- Creating task forces and coalitions to prioritize, coordinate and broker resources for resilience projects and programs.

The sub-section provides numerous real-world examples of public and private organizations improving resilience in their communities. The example of North Kingstown involves including hazard assessment in the town’s Comprehensive Plan and a small project to reduce potential flood damage.

One of the most notable cases involves Bennington, Vermont, where a decision was made to allow the local river to expand into a flood plain rather than risk flooding the downtown. A few years later, Tropical Storm Irene (originally Hurricane Irene) caused the river to flood, and the flood plain restoration averted an estimated $93 million in damages.

In 2007, a tornado destroyed 90% of the buildings in the small town of Greensburg, Kansas. The town was rebuilt as a green, resilient community, adopting Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) standards for new buildings, burying power lines, and requiring backup generators for critical facilities. These and other changes led to Greensburg being labeled “the greenest town in America.”

Critical Assessment of Success or Challenges of Approach

The EPA report, “Planning Framework for a Climate-Resilient Economy,” highlights the urgency for communities all over the U.S. to develop their own frameworks to increase resilience to climate-related threats. The primary reasons for undertaking a structured effort are:

- The potentially devastating effects of many disasters require preparations put in place often years in advance.

- A high degree of public/private communication and coordination is needed.

- Assistance from federal and state agencies can be valuable and takes time to arrange.

By breaking the process into five specific steps and delineating objectives for each step, the report enables each community to assess the envisioned framework and apply it to their physical environment and other attributes. Step three, which entails identifying community assets and specifying each asset’s vulnerability to various threats, is the cornerstone of the process. Some communities may be able to focus on more assets and perform a more comprehensive, quantitative analysis. Others may limit their efforts to evaluating the most essential assets and using existing data and knowledge.

The potential flexibilities in using technical expertise and quantitative analysis are a strength of this framework. Localities vary widely in technical resources. A more prescriptive program would dictate which experts to bring in and what modules to run on specific software. These requirements might work for some localities but be daunting or prohibitive for others. As the framework is further developed and applied, it should be possible to establish various technical options. More information concerning appropriate experts and available data and software products could help localities not know how ambitious to be concerning data and analysis.

The report is advisory; therefore, the development of the proposed framework is limited in certain respects. The EPA cannot require any community to develop this framework nor mandate a schedule for development or updating, and few localities have dedicated funding sources for resilience projects and programs. Some private businesses may be willing and able to make significant investments, but this is at the discretion of each firm. However, the framework can be a tool to emphasize the importance of securing funding and all stakeholders pulling together for the benefit of their community.

Replicability of the Approach for Other Agencies

The “Planning Framework for a Climate-Resilient Economy” presents a detailed program for developing and applying a planning framework and details the application of this framework to North Kingstown, RI. The example of the North Kingstown application provides good reason to believe that the approach is replicable and practical. There are two primary issues of concern. The first is resources at the municipal, state, federal, and private sector levels to develop this framework. The second is the will to do so, given competing priorities, political controversy, and inevitable tensions among various stakeholders.

The planned implementation in North Kingstown was sidelined by the election of a new Town Council while the report was being completed. In hindsight, it also appears that implementation in certain areas might have been promoted by more attention to equity issues and structural racism. Funding is generally seen as the most critical issue for implementation, and there has been little progress toward funding solutions in most states. However, research on this case suggests increasing optimism regarding implementation as the effects of climate change become more pronounced.

While the growing threat of massive or irreparable damage from a climate-related event provides an incentive to secure resources for this effort, every locality is different regarding its level of engagement and fiscal situation. Some localities have Local Hazard Mitigation Plans, which are required for certain FEMA grants. However, these plans are often prepared to meet minimum FEMA requirements, with little provision for mitigation or capital resilience projects. All three levels of government can work together to expand current hazard mitigation plans to implement the EPA framework.

State and federal agencies may be able to assist localities with implementation at relatively little cost. This assistance could include tracking local efforts, documenting plans and projects in numerous jurisdictions, and assessing long-term payoffs. If these results were made available in a database, that would help other localities to benefit from the experience of others. Finally, most states may have the practical ability to assist local governments with GIS functionality and data from climate models.

One participant recommended that transportation agencies, including state departments of transportation (DOTs) and metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs), play a significant role in implementation for multiple local areas. Transportation agencies frequently bring major private and public stakeholders together, and they could do so to develop resilience plans.

The report cites several examples of turning goodwill into detailed planning and follow-up action. Although not in response to a climate-related event, Clinton County, Ohio, presents an excellent example of different levels of government working to bring stakeholders together to offer assistance and effect change. After the departure of the leading employer, the state, the county, and a new non-profit put together a task force and held public meetings. The task force developed a strategy to help local businesses retain young people and improve energy efficiency. Its work enabled Clinton to remain economically in the middle tier of Ohio counties despite the initial blow to its economy.

Another example is the CLEAN Business Program of Chula Vista, California. This program provides a free energy audit and recognition for businesses that meet its sustainability standards. The CLEAN Business List provides contact information for over 150 establishments (Chula Vista,2020).

Key Takeaways

- Many local leaders are interested in planning for climate resilience to reduce economic losses from climate-related disasters. However, they lack a clear framework and process for identifying their community’s most significant vulnerabilities and the most desirable actions to increase resilience.

- The EPA’s “Planning Framework for a Climate-Resilient Economy,” prepared with input from the state of Rhode Island, provides a practical framework and numerous examples of how planning has helped communities all over the U.S. The framework is built around five specific steps detailed in this case study.

- Continuing greenhouse gas emissions and the prospect of increasing climate change lend an increased urgency to this effort. Each community needs to identify its most salient threats, such as flooding and related phenomena, wind damage, drought, blizzards, and wildfires.

- Climate resilience includes actively pursuing new opportunities and handling climate-related threats. The framework encourages businesses and governments to take advantage of market changes and needs. Several examples are provided in the report.

- Each community can customize the framework to meet its needs best. Some communities can marshal more resources and apply more sophisticated analysis, while others may consider fewer assets and rely upon available data. But numerous communities can profit from using the framework.

- Since the report was posted in 2016, implementation has not been as extensive as was hoped. In the case of North Kingstown, RI, newly elected council members deemphasized implementation. The case of North Kingstown provides a lesson that planners and private stakeholders interested in developing a resilience planning framework must be sensitive to local political conditions and developments.

3A.5: Florida Resilience Planning at Metropolitan Planning Organizations

Summary

This case study explores efforts within Florida to incorporate resilience into the transportation planning process. The Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) has undertaken efforts and developed guidance to assist the state’s 27 MPOs in incorporating resilience into their efforts. Florida’s efforts have been guided and assisted by FHWA’s Vulnerability Assessment and Adaptation Framework. The case also highlights data-driven planning efforts undertaken by Resilient Tampa Bay, a coalition of regional groups that include the region’s MPOs.

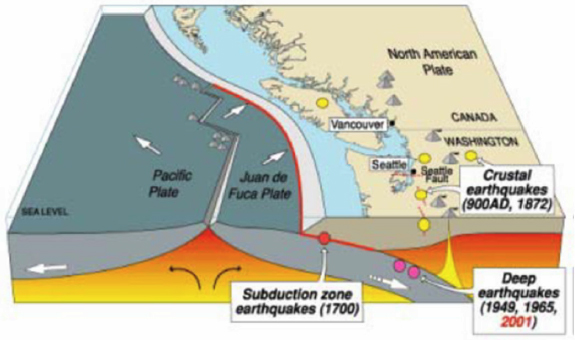

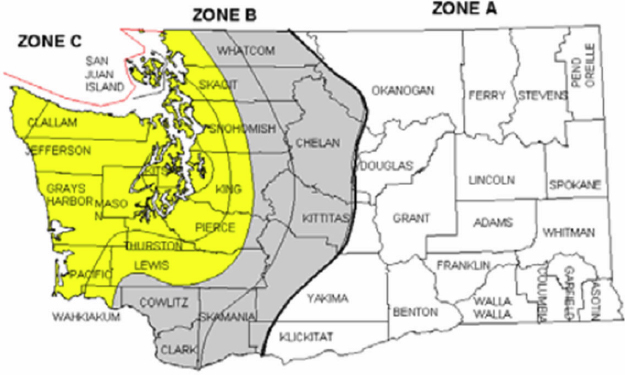

The fact that Florida’s effort falls within the “Preparedness” phase of the resilience cycle points to its appropriateness for any transportation planning efforts in regions with recurring disruptive events like hurricanes, flooding, forest fires, and landslides, or those reasonably expecting a disruptive event may occur, such as an earthquake.

Resilience planning is an ongoing process for FDOT and the state. Florida is home to 27 MPOs with various levels of sophistication, which adds complexity to an already complex undertaking. Resilience is a broad issue with efforts underway by multiple jurisdictions, agencies, and actors. Often, these Florida-based resilience coalitions work together. Up to this point, FDOT has received positive feedback related to its Resilience Quick Guide. The Quick Guide has also been used to educate local politicians and communities about the ongoing efforts at the state and local levels to plan for future disruptive events.

There is a lot of enthusiasm and support for the resiliency effort. However, it was acknowledged that coordination among the many players, and even within FDOT, is a work in progress. For instance, it has not been clearly established how incorporating resilience in the planning process translates into projects developed in the long-range plans, which are then carried through to the project development process and implementation.

The ability of the MPO to frame resiliency in a way that is not fiscally constrained, provides an opportunity to show how projects will strengthen and create a more adaptable transportation network and offer valuable comparisons to use when selecting the best projects, programs, policies, and planning efforts.

-FDOT, Resilience Quick Guide

Finally, there is an opportunity to use a needs plan to identify the transportation infrastructure essential to accommodate future travel demand and assess how projects would strengthen the network’s resilience. A needs plan, or needs assessment, is an element of the LRTP that does not consider financial constraints when inventorying transportation investment projects to improve efficiency and meet future needs. Maps resulting from vulnerability assessments also help communicate the need for resilience planning to the general public and legislative representatives.

Keywords: vulnerability assessment, resilience, resiliency, adaptation framework

Description of Resilience Approach Taken

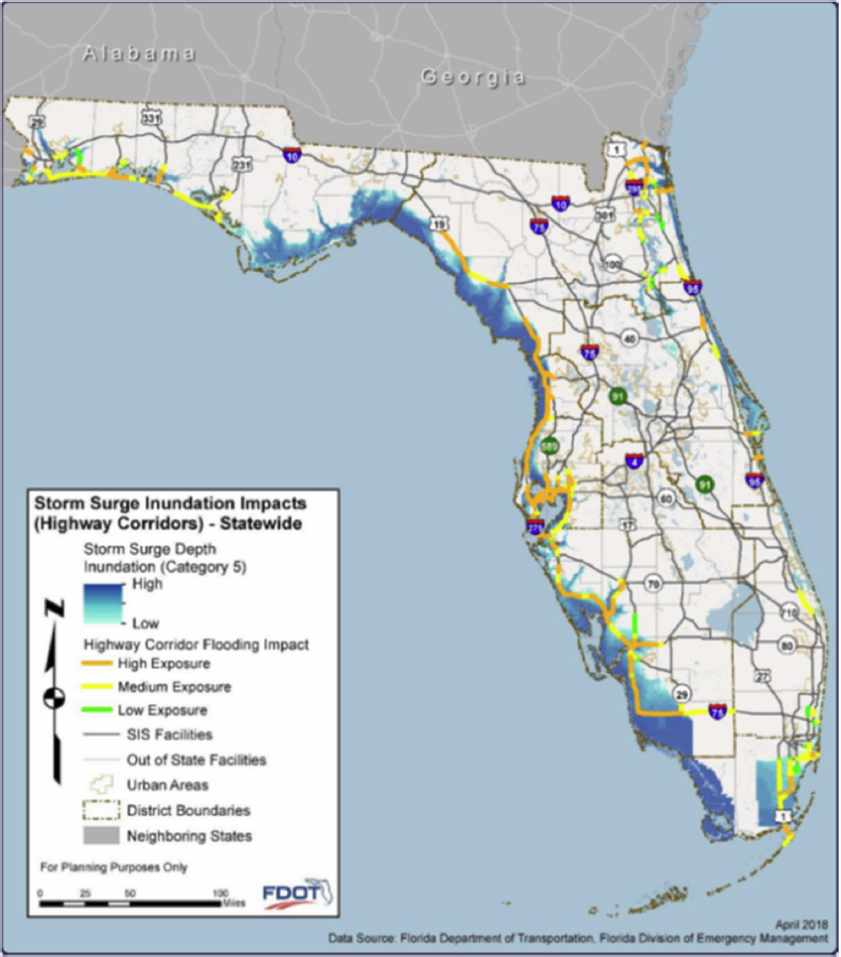

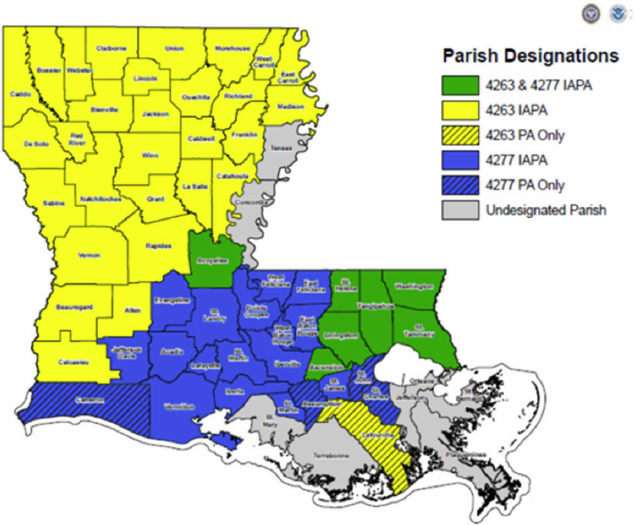

Florida Department of Transportation’s (FDOT) incorporation of resilience into its planning efforts and those of the state’s MPOs was not the result of a single incident or event. It was a response to the growing threat of various types of disruption events, such as hurricanes, flooding, wildfires, and cyberattacks, that can negatively affect its residents and businesses. Forecasted population growth of 30% to 27 million people by 2045, rising sea levels, and shifts in global economic trade partnerships are trends expected to increase the complexity of improving the resilience of a statewide multimodal transportation system. Florida’s effort falls within the “Preparedness” phase of the Resilience Timeline, shown in Figure 21.

Federal Regulation 23 CFR 450.306(b)(9)

requires Metropolitan Planning Organizations, in cooperation with the State and public transportation operators to improve the resiliency and reliability of the transportation system and reduce or mitigate stormwater impacts of surface transportation.

In its most recent Florida Transportation Plan (FTP), FDOT identified resilience as one of its long-range goals and cross-cutting topics with a focus on how extreme weather events affect the transportation system, emergency evacuations and responses, rising sea levels, and economic and societal changes. In January 2020, it released its Resilience Quick Guide: Incorporating Resilience in the MPO Long Range Transportation Plan. The guide is meant to assist transportation agencies across the state plan, design, build, and operate transportation facilities that can quickly recover from the various disruption incidents the state commonly faces. It discusses the sections of an LRTP as it relates to resilience, such as goals and objectives, performance measures and targets, a risk and vulnerabilities assessment, a needs plan development, and investment and project prioritizations. The guide provides each section’s noteworthy practices from MPOs in Florida and nationwide.

In a separate effort, the Hillsborough, Pinellas, and Pasco County MPOs, the Tampa Bay Regional Planning Commission, and FDOT participated in the Federal Highway Administration’s (FHWA) Resilience and Durability to Extreme Weather Pilot Program. The 11 pilot projects sought to incorporate resilience into transportation agencies’ practices, tools, resources, performance management, and decision-making. The Resilient Tampa Bay (RTB) project noted that with 1,000 plus miles of shoreline and 39% of its 2.8 million residents located within flood zones, the Third National Climate Assessment (2014) identified its region as one of three areas in Florida especially susceptible to rising sea levels. This region’s potential losses from storm surges are estimated at $175 billion. The pilot study focused on assessing the vulnerability of the region’s surface transportation assets and integrating hazard mitigation, emergency management, and post-disaster redevelopment plans into their LRTPs. It was conducted with two goals in mind:

- Address the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act requirement for MPOs to incorporate and improve the resilience and reliability of the transportation system into their long-range planning.

- Inform decision-making and ensure the region’s transportation system meets functional, economic, and quality of life goals for its users (residents, businesses, and tourists).

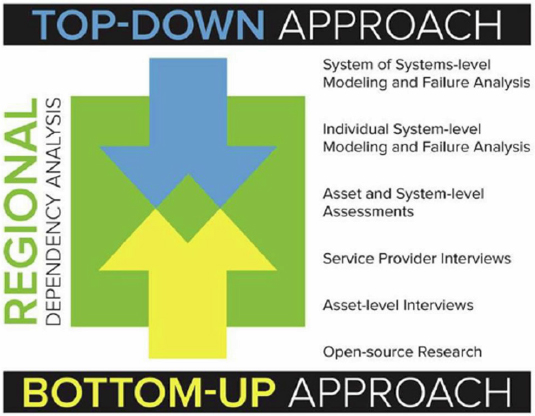

At the core of the 11 FHWA Resilience and Durability to Extreme Weather Pilot Projects was its Vulnerability Assessment and Adaptation Framework. This framework was developed to help state, regional, and local transportation agencies assess the vulnerability of their transportation systems and underlying assets to the effects of extreme weather. The framework provides national examples of previously conducted assessments between 2010 and 2017, links to more information and related resources, and a step-by-step process for conducting a vulnerability assessment including:

- Defining objectives and scope,

- Obtaining asset and climate data,

- Assessing vulnerability,

- Identifying, analyzing, and prioritizing adaptation options, and

- Incorporating results into decision-making.

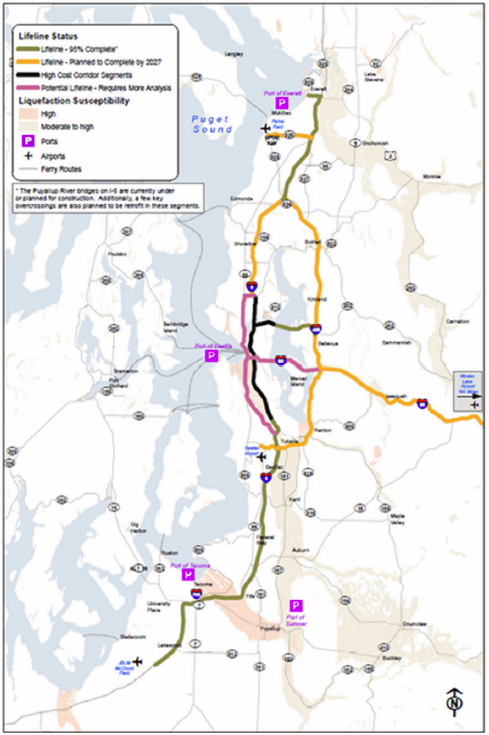

As one of the 11 pilot projects, Resilient Tampa Bay utilized FHWA’s Vulnerability Assessment and Adaptation Framework to design its work plan. FDOT referenced the framework in its Resilience Quick Guide section, “Risks and Vulnerabilities Assessment,” and reviewed it before establishing its own framework used to conduct its risk assessment on the state’s Strategic Intermodal System (SIS), shown in Figure 22. FDOT developed its framework to be a tool used to support and strengthen its decision-making by incorporating weather-related risks as they relate to the sustainability of the SIS network and FDOT’s role in improving mobility and economic competitiveness for the state’s residents and businesses. The study identified critical infrastructure and network risks/vulnerabilities stemming from floods and pre-disaster mitigation strategies such as retrofitting and adapting existing assets, pre-disaster emergency response planning, and emergency response operations, among others.

Geospatial data, tools, and models played a central role in FDOT’s and Resilient Tampa Bay’s assessments. Data related to the climate and weather were paired with topographic characteristics and transportation assets to conduct the vulnerability assessments. The University of Florida’s GeoPlan Center’s Sea Level Rise Inundation Surface Calculation Tool and the Sea, Lake, and Overland Surges from Hurricanes (SLOSH) model from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) were combined with the geospatial data to understand the geographic extent of future sea levels and storm surges. GeoPlan’s sketch planning tool is a publicly available ArcGIS add-in that helps to identify and visualize transportation assets at risk from sea-level rise, storm surge, and inland flooding. Resilient Tampa Bay has created an ArcGIS tool suite with built-in storm surge, rain event, demographic, and damage models for MPO and county use. Figure 22 shows the SIS facilities’ assessment of a Category 5 storm surge.

Resilient Tampa Bay’s vulnerability assessment used NOAA’s 2045 High Sea Level Rise Projection and Category 3 Storm Surge estimation to identify areas vulnerable to flooding and associated transportation infrastructure. Links in the region’s transportation network were categorized based on criticality by combining qualitative information via stakeholder engagement with quantitative GIS-based analysis. The critical linkages were classified as either low, medium, or high using 11 weighted factors:

- Evacuation Route (3 pts.)

- Projected 2040 Traffic volume (3 pts.)

- Proximity or primary route to major economic and social activity centers (3 pts.)

- Projected Population Density (3 pts.)

- Transit Corridor (2 pts.)

- Part of adopted land use and transportation plans (LRTP, TIP, SIS, NHFN) (2 pts.)

- Projected Employment Density (2 pts.)

- Percentage of zero-car households (2 pts.)

- Intermodal Connectivity (1 pts.)

- Projected Truck Traffic or Freight Corridor (1 pt.)

- Equity Areas- Environmental Justice (disadvantaged populations) (1 pt.)

After Resilient Tampa Bay conducted the criticality assessment, it considered adaptation strategies using scenario planning with the help of econometric modeling via REMI’s TranSight model. The scenarios looked at the benefits and costs of various investment levels. Scenario 1 included an investment level 1 ($31 million per year) to continue today’s stormwater drainage improvement program and a Category 3 storm. Scenario 8b paired a Category 3 storm with a level 3 investment ($39 million per year) to continue today’s stormwater drainage improvement programs, raise road profiles, enhance base, and protect shorelines from wave damage. Scenario 1 resulted in eight weeks of major roads being unusable and $266 million in economic losses. Scenario 8b resulted in losing major roads for three weeks and $119 million in financial losses, more than half of Scenario 1’s losses. Several representative projects were selected and evaluated to identify appropriate mitigation strategies and associated costs to be included in the LRTP.

A Critical Assessment of the Success or Challenges of the Approach

Resilience planning is an ongoing process for FDOT. Florida is home to 27 MPOs with various levels of sophistication, which adds complexity to an already complex undertaking. Some MPOs in the state are progressive when it comes to resilience planning, while some are just getting started. The process is constantly ongoing, with updates to LRTPs required every four or five years. For example, eight MPOs’ LRTPs were updated in the fall of 2019, 15 were updated for the fall of 2020, and four were scheduled for the fall of 2021. As of this study, FDOT has received positive feedback about its Resilience Quick Guide and has encountered no resistance from MPOs when it was introduced. While the guide may not present any new information for some of the more progressive Florida MPOs, it has effectively been used to educate local politicians and communities about the ongoing efforts at the state and local levels to plan for future disruptive events.