Developing a Research Agenda on Contrails and Their Climate Impacts (2025)

Chapter: 1 Overview

1

Overview

The cumulative emissions of the air transportation sector, while generating significant societal benefits, currently contribute approximately 2.5 percent of the overall global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions (and about 1 percent of total radiative forcing) from human (anthropogenic) activity. Even with advancements in airplane and engine technologies that have reduced the CO2 intensity of aviation, overall emissions continue to rise as the growth in air traffic outpaces efficiency gains. Over the past decades with significant investment in technologies, annual aviation fuel burn efficiency improvements have averaged 1–2 percent; however, fuel burn and emissions have grown by 4–5 percent annually, leading to a net increase in total CO2 emissions (Lee et al. 2021 and references therein). The increases in the aviation sector stand out compared to decreasing emissions from other sectors due to phasing out of fossil fuels. The radiative forcing effects on climate of aviation-related CO2 emissions is well understood with a high degree of confidence. A critical characteristic of anthropogenic CO2 emissions is their long atmospheric lifetime, persisting for about a century before being reabsorbed through oceanic and atmospheric processes.

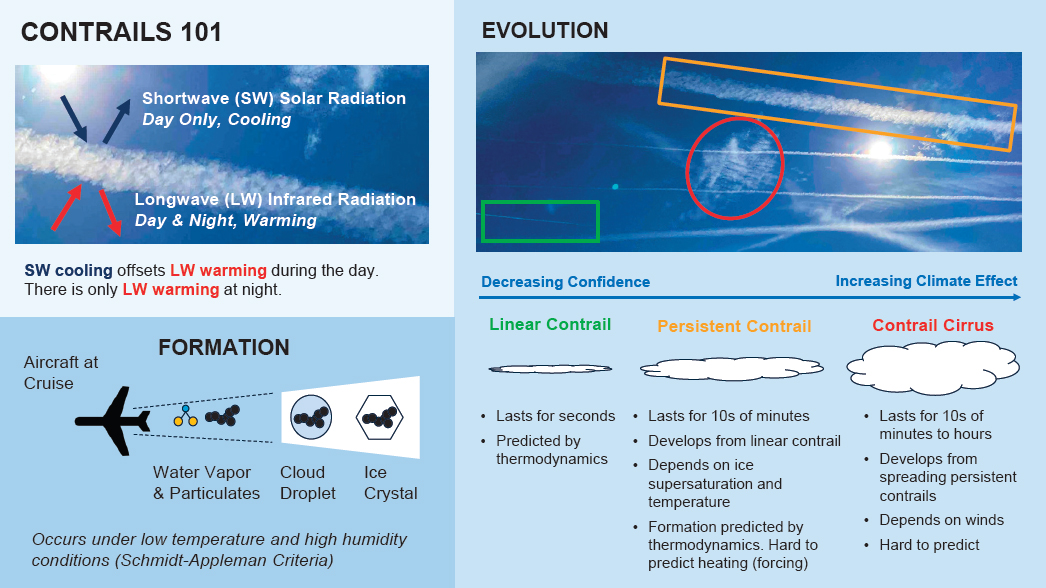

Aviation condensation trails (contrails) and their associated aviation-induced cloudiness are, in addition to CO2, another significant source of aviation climate impact and are assessed to contribute another ~1.5 percent of total anthropogenic radiative forcing of climate (IPCC 1999; Lee et al. 2021). Contrails (Figure 1-1) are created when warm aircraft engine exhaust, laden with water vapor and particulates, interacts with a cold ambient atmosphere with humidity higher than the saturation vapor pressure over ice (“supersaturated” with respect to ice). Under conditions defined by the Schmidt–Appleman criterion (Appleman 1953; Schumann 1996), which describes mixing of warm and humid jet exhaust with surrounding ambient air, the water vapor in engine exhaust will condense on the particulates in the exhaust plume and freeze to form a contrail (Figure 1-1, lower left). If the temperature is cold enough and the atmosphere is supersaturated with respect to ice (which can be frequent in clear skies in the upper troposphere), then a contrail can form and persist, beyond 10 minutes. These persistent contrails are of concern for climate impact.

Contrails influence climate by altering Earth’s energy balance, contributing both warming and cooling effects. Their overall effects are assessed through the concept of radiative forcing, which measures the change in energy flux at the top of the atmosphere caused by contrails. This includes both the heat trapped (longwave effect) and the sunlight reflected back into space (shortwave effect).

Contrails reflect daytime incoming solar radiation and also absorb and re-radiate outgoing infrared radiation to Earth and space (Figure 1-1, upper left). Since clouds are white, and generally brighter than the surface below, they will generally cool the surface in the solar or “shortwave” bands. Their maximum cooling effect is

SOURCE: Airplane icon courtesy of iconsDB.com.

over a dark surface (ocean), with almost no cooling effect over snow, ice, other clouds, or at night. In the infrared (“longwave” bands), contrails are colder than the underlying surface (or clouds) below, and they trap energy and re-radiate or scatter it at a colder temperature to space (and back down to Earth), warming the surface. The effect is largest over warmer surfaces and occurs day or night.

The net warming versus cooling effect of contrails depends on many factors, including ambient temperature, ice mass, crystal size and shape (determining the optical thickness), as well as the location of the Sun and the underlying Earth surface or cloud brightness and temperature. Another key attribute of contrails is that, if they form, they can have a persistence on the order of minutes to hours (Figure 1-1, right). The integrated effect of an individual contrail depends on its lifetime and the factors above. On balance, the net effect of all contrails (as in general with natural cirrus ice clouds) is to warm the planet, although some individual contrails can locally cool the planet.

The key for predicting where a persistent contrail will form that is significant for climate is the ability to predict where the atmosphere is supersaturated with respect to ice, known as ice-supersaturated regions (ISSRs). ISSRs occur frequently in the upper troposphere at commercial transport airplane cruising altitudes (Gettelman et al. 2006). If a flight occurs through an ISSR and the Schmidt–Appleman criterion is met (cold enough temperature and high enough humidity), then a contrail will form and may persist. Persistent contrails in an ISSR take up water from the ambient atmosphere, so that most of the ice mass in a contrail comes not from the aircraft exhaust, but from ambient water vapor. Persistent contrails can last from tens of minutes to hours, and longer-lived contrails can further evolve from linear features into “contrail cirrus” (Figure 1-1, right). To determine the aggregate radiative effect of many contrails from operation of the entire aviation fleet, individual contrails are aggregated across

global flights and applied over the area of the planet. Individual contrails last only a short time; however, the global aircraft fleet flies continuously and creates contrails continuously, thus overall creating a warming effect, which is usually assessed on an annual basis, with variations due to the seasonal evolution of the ambient atmosphere and seasonal changes to aircraft routing.

The climate impact of contrails, other aerosols, and greenhouse gases was first estimated through instantaneous radiative forcing (RFinst or RF), which is calculated as the net change in radiative balance (solar heating minus thermal cooling) in watts per meter squared (W/m2) at the top of the atmosphere caused by an instantaneous change in atmospheric composition (e.g., occurrence of a contrail, or increase in mean CO2 abundance). The assumption in the early generations of Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) climate assessments was that the global mean warming was linearly proportional to the persistent RF change, and thus RF became the metric to compare climate change across greenhouse gases and aerosols. As climate science evolved, it became clear that for some types of perturbants, the RF did not accurately predict warming because the atmosphere develops short-term responses to the RFinst. Current IPCC climate assessments use effective radiative forcing (ERF), which accounts for the RF change after the atmosphere has adjusted to the perturbation (e.g., via altered temperatures and/or clouds). The difference between RF and ERF varies by forcing agent (see Figure 1-3 later in this section and discussion in Lee et al. [2021]).

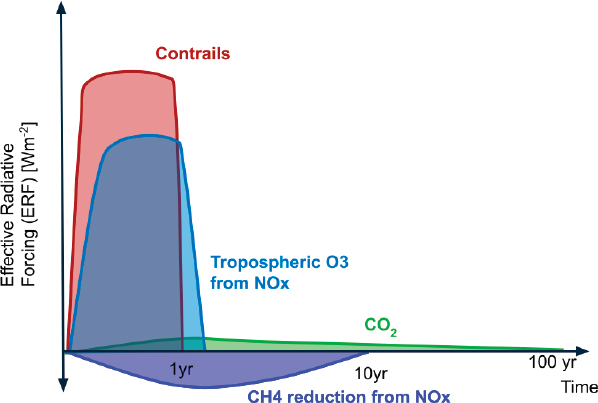

The radiative forcing effects of contrails versus other aviation emissions spans orders of magnitudes relative to their persistence. Contrails create a very-short-lived radiative forcing (hours or days); nitrogen oxides (NOx) emissions perturb the greenhouse gases CH4 and O3 for months to decades; while CO2 emissions decay on timescales of decades to centuries or longer. The impact of these differences in persistence on climate change metrics is discussed in Box 1-1.

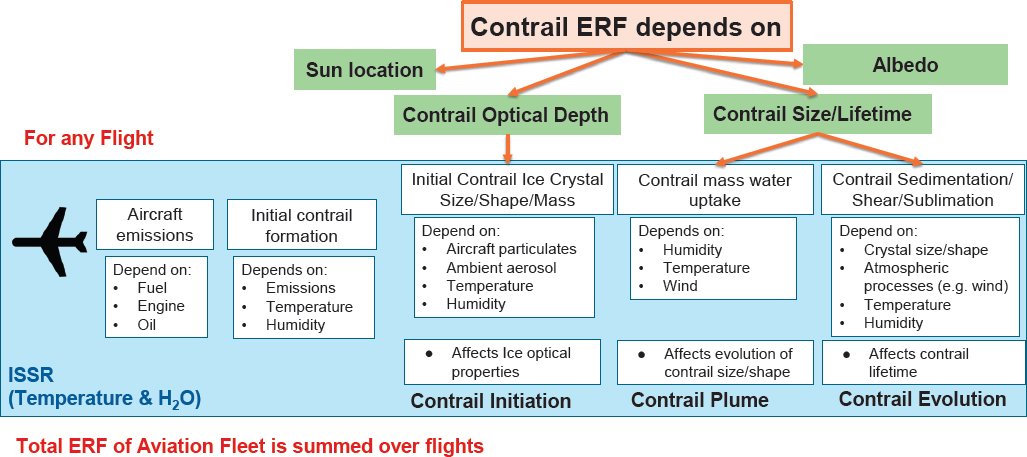

ISSRs are the primary condition for the creation and persistence of contrails. Due to the uncertainties in forecasting ISSRs, there is significant uncertainty in developing effective mitigation strategies based on contrail avoidance. The sources of uncertainty in estimating contrail formation and corresponding contrail radiative effects are illustrated in Figure 1-2.

The observation and prediction of ISSRs is challenging, but given a flight through an ISSR, it is typically well determined that a persistent contrail will form. The resulting initial ice crystal size distribution formed after a few aircraft lengths of wake affects the ultimate contrail optical properties (Figure 1-2) and depends on the total particulates emitted from the engine (both engine produced and the ambient particulates that pass through the engine or mix with the contrail plume). The concentration of particles varies significantly by aircraft engine type, engine power setting, and jet fuel chemical composition. Particulates are generally soot and other non-volatile particulate matter, as well as some condensed volatiles (such as sulfates or organics). Because of the high degree of water supersaturation that occurs initially in the plume, almost all particulates above a certain size nucleate water droplets that subsequently freeze. Observations exist for both aircraft particulate emissions and of initial contrail ice particle size distributions, which are used for calibrating model simulations of contrails.

The ERF of a contrail depends on the distribution of ice crystal size, mass density, and particle shape. These properties determine the optical depth of the contrail over time (Figure 1-2). The initial ice crystal size distribution evolves as the contrail takes up ambient water. The speed and amount of water vapor uptake depends on the degree of supersaturation: an ISSR with a relative humidity (RH) of 120 percent over ice will result in more water vapor uptake (and more ice mass) than an ISSR with 105 percent RH over ice. Over time, the contrail evolves in the atmosphere, undergoing shearing due to atmospheric processes and with its ice crystals sedimenting out as they grow. If the ambient atmosphere then becomes subsaturated with respect to ice, the contrail will begin to sublimate, diminish, and disappear.

Observations of contrails exist from various observational platforms and instrument types: ground based, airborne in situ, airborne remote sensing, and space-based remote sensing. The evolution of a contrail (horizontal and vertical extent) is determined by atmospheric conditions, including winds, and wind gradients that can shear out a contrail. Observations and data sets from satellites and the ground exist for contrails for age, extent (size), and lifetime. The total radiative effect of a contrail is determined by the following: its optical depth over space and time, its location relative to the Sun, surface albedo, or reflectance (to determine net shortwave reflection), and the underlying surface temperature (to determine the net longwave absorption). The radiative effect of a contrail also

BOX 1-1

A Temporal View of Climate Impact Metrics

From the scale of shifting an individual flight to rerouting the entire aviation fleet, reducing contrail impacts requires a trade-off between eliminating contrails and burning slightly more fuel, thereby emitting more CO2 and NOx on the modified route. In terms of climate impact trade-offs, there are effective radiative forcing (ERF) estimates of the different emissions/impacts (contrails, CO2 and NOx) from models. As ERF is expressed as a rate (radiative effect per unit area and unit time, W/m2), it is necessary to understand the timescales over which effects occur to compare impacts. The persistence of ERFs from aviation span a large range of timescales, as illustrated in Figure 1-1-1, where 1 year of aviation emissions is illustrated schematically. The ERF persistence varies as follows: a century or more for CO2; 1 month and 10 years for NOx (two different effects); and hours for contrails. Consequently, the total effect of contrails or NOx emissions from an activity (a flight, or a year of flights, also called an “impulse”) tends to be immediate, while aviation CO2 and the 10-year NOx effects on methane act over a much longer period of time than just the year of activity. These ERF curves must be integrated over time to calculate the total climate impact. Note that Figure 1-3 from Lee et al. (2021) represents cumulative emissions to date, so is different than Figure 1-1-1.

depends on other clouds (including contrails) below or above it. Two similar contrails with a different position relative to the Sun and with a different albedo below will have different radiative effects.

Several studies have addressed quantifying the overall radiative effect of contrails and understanding their uncertainties. The studies took various approaches and utilized different methodologies. However, they were all constrained by observations and theory and considered the chain of processes in Figure 1-2, to estimate the contrail optical depth and lifetime to determine the radiative forcing of resulting contrail cirrus, and to

Many climate change metrics have been defined for comparing disparate sources of climate forcing, and each has a different purpose depending on the policy goals (e.g., Forster et al. [2021]; Myhre et al. [2013]). The Global Warming Potential (GWP) was the original metric for comparing emissions of different greenhouse gases (GHGs): carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and chlorofluorocarbons. GWP has been adopted as the standard by the governments under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. For long-lived, well-mixed GHGs, their ERF does not depend on where they were emitted in the lower atmosphere. GWP for a GHG is the ratio of the warming to that caused by the same mass emission (kg) of CO2.

The timescale selected for climate metrics is a decision based on policy choices, not just the physics of the atmosphere. When defined in the late 20th century, climate change research was concerned with 100-year timelines, so GWP-100 (100-year time integration) was used. The 2015 Paris Accord shifted the focus to the 2050 time frame, and thus there is more focus now on 20-year timescales.

In addition, new metrics, such as the Global Temperature Potential (GTP), are being used. GTP integrates the ERF effects of emissions over time to calculate the change in temperature at the end of the GTP time frame. Like GWP, GTP is a ratio of the effect relative to the CO2 impact on a kilogram-per-kilogram emission basis. GWP and related metrics like GTP are based on ratios of 1 kg emissions and thus cannot directly apply to contrails, or indirect GHGs like NOx that act by altering other species, particularly ozone and methane.

For contrails, the climate effect is the annual mean over time of the ERF from an “activity” (either an individual flight, or 1 year of operations of the civil fleet).a Because the contrail effects do not last much beyond the time of the flight (or the year of operations), the integrated ERF remains constant over 20- or 100-year time horizons. For CO2 emitted from aircraft (one or a year of operations), the instantaneous ERF largely continues out to 100 years or beyond (Figure 1-1-1), and so the integrated ERF increases as the time window is longer. Thus, contrail mitigation is relatively more important with respect to CO2 emissions when using a shorter time horizon. The comparison is not readily available from the ERF bar chart of Lee et al. (2021) because the CO2 ERF includes past accumulation but not future effects.

A common desire among users of climate change metrics is to declare a Social Cost of Carbon (SCC) that measures in dollars long-term damage caused by emissions of 1 ton of CO2. Federal agencies often use the SCC estimates to place a value on the climate impacts of rulemakings. The economic costs (e.g., added energy use) can be evaluated and there are many SCC values, especially in the economics literature. Because “cost-benefit analysis remains limited in its ability to represent all avoided damages from climate change” (IPCC 2023), estimates of the SCC are highly uncertain and almost certainly biased low.

__________________

a The “civil fleet” includes commercial, non-military government aircraft, and business aircraft, and the latter two categories are a small percentage of the civil fleet. Most aviation climate studies discuss the civil fleet.

estimate the ERF of the overall aviation fleet. Conceptually, when an ISSR is present at given temperatures, contrails will form and persist, but forecasting and simulating these regions is challenging. Particulate emissions can vary widely, as determined by measurements from different aircraft engine types and fuels, as well as the resulting near-field ice crystal sizes (ice number reflects engine particle emissions). Observations of contrail extent and lifetime from the ground and satellites provide distributions for comparison. All these observations are used to constrain model estimates: some are bottom-up models that track each individual

NOTE: ERF, effective radiative forcing; ISSR, ice-supersaturated region.

SOURCE: Airplane icon courtesy of iconsDB.com.

contrail using a static historical atmosphere, and some are climate models that initiate contrails that evolve in a simulated atmosphere.

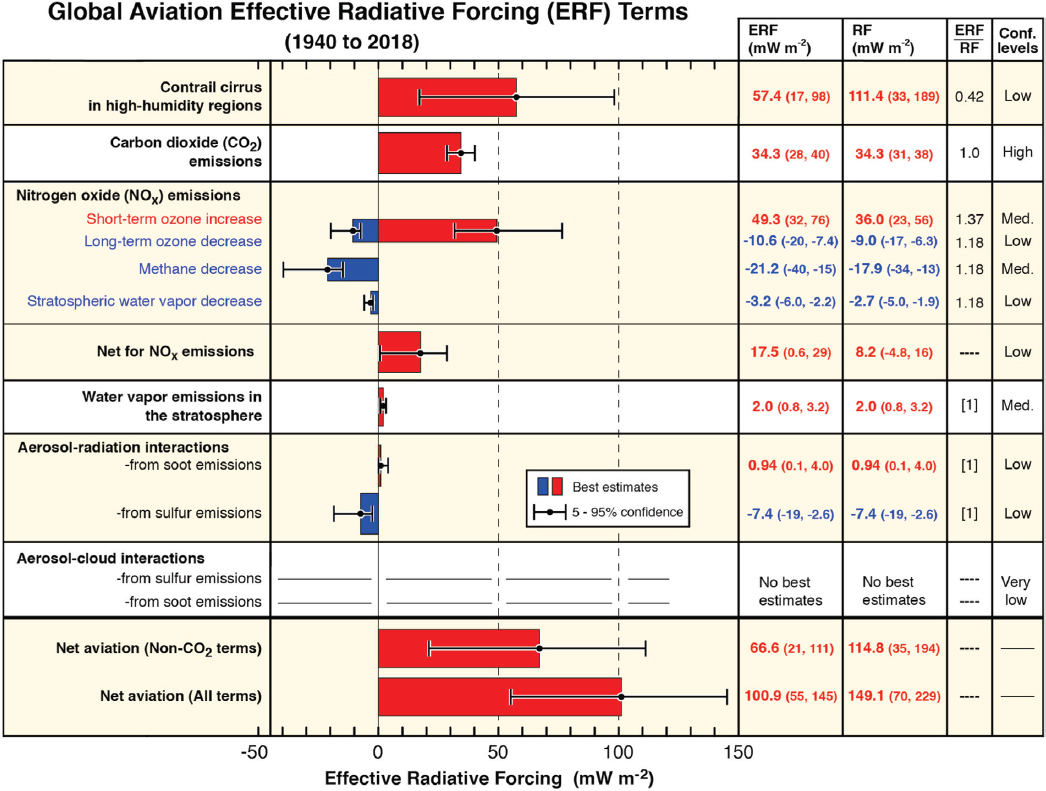

Each methodology has its own uncertainties and sensitivities, which are assessed in various publications. Recent assessments (Lee et al. 2021) have tried to harmonize these studies to have the same assumptions and provide a best global contrail ERF estimate of about 0.06 W/m2, with large uncertainties of about ±70 percent (Figure 1-3). The uncertainty range for the total fleet is limited because there are observational constraints on contrails (lifetime, geometric extent, crystal size, optical depth) and some contrasting effects (big particles have more mass but sediment faster). The ERF from cumulative aviation CO2 emissions is 0.03 W/m2 (and growing slightly) with uncertainties of about 17–19 percent.

Aviation emissions of nitrogen oxides (NOx) are another important non-CO2 source of climate forcing (Figure 1-3), and these impacts are also relatively short lived compared to CO2. NOx is generated internally to the engine where the high temperatures of combustion cause reactions of atmospheric nitrogen and oxygen. Driven by atmospheric chemistry, these NOx emissions lead to short-term increases in tropospheric ozone (O3), which is itself a greenhouse gas. The NOx-related perturbation of O3 has a nominal ERF impact on the same order as that of CO2. However, other atmospheric chemistry processes involving NOx lead to reductions in atmospheric methane, another major greenhouse gas, which offsets some of the impact of ozone. Overall, these opposing effects lead to a current net ERF impact of NOx with a best estimate that is 50 percent lower than that of CO2 and 70 percent lower than that of contrails (Figure 1-3). However, these offsetting effects also result in a relatively large uncertainty range for net NOx ERF; that is, from −97 to +66 percent of the central estimate. Therefore, the net ERF effects of NOx are correspondingly assessed with a low confidence level.

Quantifying the climate impact of aviation emissions, particularly for contrails and NOx emissions, has been the focus of many researchers, with several recent assessments of this work (Lee et al. 2021, Figure 1-3, 2023). The assessment of aviation CO2 ERF in Figure 1-3 was performed over the period of 1940 (when aviation contrails were first observed) through 2018 by normalizing the methodologies and results across many different studies such that they could be used to develop consensus results. Short-term (NOx and contrail) effects represent a steady state from the 2018 fleet. The results show that the largest non-CO2 warming effect of aviation is due to contrails and their associated aviation-induced cloudiness (which is discussed further in Chapter 2). The climate

SOURCE: Reprinted from D.S. Lee, D.W. Fahey, A. Skowron, et al., 2021, “The Contribution of Global Aviation to Anthropogenic Climate Forcing for 2000 to 2018,” Atmospheric Environment 244:117834, with permission from Elsevier, © 2020 Elsevier.

warming impact of contrails, measured as ERF, has been estimated to be 67 percent greater than that of CO2 in 2018. However, the ERF impact of contrails has significant uncertainty, that is, ±70 percent, due to uncertainties in underlying processes and methods, and therefore their impact has been assessed with a low confidence level. Validation of models and the diversity of approaches provides some robustness to the sign of the contrail impact: the effects are on aggregate a warming effect. Combining the CO2 and non-CO2 effects from contrails and NOx yields an overall ERF from aviation of about 0.1 W/m2, or about 4 percent of total anthropogenic forcing.

The assessment of the ERF warming impact of contrails by Lee et al. (2021) has been estimated based on several studies, employing a range of methodologies, and with efforts to harmonize the results. Typically, these studies use a combination of contrail observations as well as weather data and/or model simulations. Model studies of contrail climate effects are typically calibrated by observations (e.g., observed contrail ice crystal sizes, contrail sizes) and use uncertainty (sensitivity) analysis to quantify the possible range of estimates. The individual studies were then harmonized based on their assumptions, and the uncertainty was determined from the statistical combination of the reported uncertainty from each study.

Finding: The current overall aviation impact on climate, comprises ~4 percent of all anthropogenic climate forcing.

Finding: The effect of aviation due to contrails and aviation-induced cloudiness is comparable to aviation CO2 with the timescale of impact determining which is larger. Aviation NOx emissions cause two separate impacts, each of which is comparable to aviation CO2 in the absolute sense, but they have opposite signs and thus the net positive forcing is about half that of aviation CO2.

Finding: In aggregate, there is confidence that contrails create a net warming effect. The uncertainty in this climate forcing is large but does not include net cooling.

Strongly warming contrails occur in a relatively small percentage of all flights (Teoh et al. 2024). It is estimated that most (~80 percent) flights have negligible or no impact on climate forcing. Only a small percentage of flights and flight distances result in the majority of overall warming impact of contrails, and thus contrail avoidance must include the skill in predicting the few flights that will have the largest contrail warming effect.

Finding: A relatively small percentage of flights account for the majority of the contrail warming effect.

REPORT OUTLINE

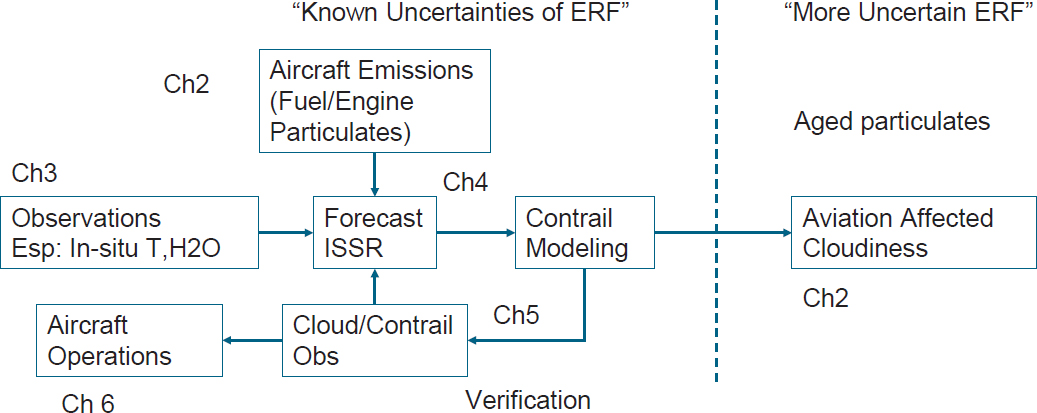

This report will discuss the chain of contrail effects from aircraft to contrail evolution and provide recommendations on where NASA can focus on research to accelerate understanding of the contrail formation, life cycle, and options for mitigation of contrail climate effects. Figure 1-4 illustrates this schematically.

Contrail evolution and radiative forcing (as well as aviation-induced cloudiness) are affected by the emissions of aircraft engine particulate matter (Chapter 2). The engine combustion characteristics and the fuel composition strongly influence the particulate concentrations and size distributions. More observations are necessary to assess the impact of the chemical composition of alternative jet fuels on total engine particulate emissions. Understanding contrail effects first requires good measurements of the atmosphere (Chapter 3). Ambient temperature and humidity control the formation and persistence of contrails, and higher-quality observations are necessary to

improve ISSR forecasting. These measurements need to be accurate and with high vertical resolution regarding altitudes and flight levels, which could be achieved via increased deployment of sensors on board commercial aircraft. The most important part of predicting warming contrails for a specific set of aircraft is predicting ISSRs with models (Chapter 4) and then also simulating contrail initiation and evolution. Verification of forecasts and observing contrails in real time is also critical for assessing any changes to aircraft routings, and this can be done with constrained and data-driven models, as well as satellite observations of contrails in forecast systems (Chapter 5). Finally, to try to mitigate the effects of contrails, aircraft operations (discussed in Chapter 6) will have to incorporate validated contrail predictions based on observations (discussed in Chapter 3), aircraft engine type and fuel (discussed in Chapter 2), and ISSR and contrail evolution forecasts (Chapter 4) that are suitably verified (Chapter 5). This comprehensive research plan has a few places where NASA has unique capabilities to advance science and operations. Additional findings and recommendations are in the following chapters (Figure 1-5).

Mitigating contrail effects on climate requires the engagement of many stakeholders, including scientists, regulators, airframers, engine manufacturers, and operators. NASA is in a unique position as a non-regulator that touches a number of parts of the aviation-climate space. The agency has both resources and a reputation that positions it to take a leading role in this research to attain U.S. international leadership and competitiveness.

REFERENCES

Appleman, H.S. 1953. “The Formation of Exhaust Condensation Trails by Jet Aircraft.” Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 34(1):14–20. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0477-34.1.14.

Forster, P., T. Storelvmo, K. Armour, W. Collins, J.-L. Dufresne, D. Frame, D.J. Lunt, et al. 2021. “The Earth’s Energy Budget, Climate Feedbacks, and Climate Sensitivity.” Pp. 923–1054 in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, et al., eds. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.009.

Gettelman, A., E.J. Fetzer, F.W. Irion, and A. Eldering. 2006. “The Global Distribution of Supersaturation in the Upper Troposphere from the Atmospheric Infrared Sounder.” Journal of Climate 19:6089–6103.

IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). 2023. “Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report Summary for Policymakers.” Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report. https://doi.org/10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647.

Lee, D.S., D.W. Fahey, A. Skowron, M.R. Allen, U. Burkhardt, Q. Chen, S.J. Doherty, et al. 2021. “The Contribution of Global Aviation to Anthropogenic Climate Forcing for 2000 to 2018.” Atmospheric Environment 244:117834.

Lee, D.S., M.R. Allen, N. Cumpsty, B. Owen, K.P. Shine, and A. Skowron. 2023. “Uncertainties in Mitigating Aviation Non-CO2 Emissions for Climate and Air Quality Using Hydrocarbon Fuels.” Environmental Science: Atmospheres 12(3):1693–1740.

Myhre, G., D. Shindell, F.-M. Bréon, W. Collins, J. Fuglestvedt, J. Huang, D. Koch, et al. 2013. “Anthropogenic and Natural Radiative Forcing.” Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Schumann, U. 1996. “On Conditions for Contrail Formation from Aircraft Exhausts.” Meteorologische Zeitschrift 5(1):4–23. https://doi.org/10.1127/metz/5/1996/4.

Teoh, R., Z. Engberg, U. Schumann, C. Voigt, M. Shapiro, S. Rohs, and M.E.J. Stettler. 2024. “Global Aviation Contrail Climate Effects from 2019 to 2021.” Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 24(10):6071–6093.