Developing a Research Agenda on Contrails and Their Climate Impacts (2025)

Chapter: 5 Contrail Forecast and Verification

5

Contrail Forecast and Verification

Modeling systems described in Chapter 4 can and have been used to assess the overall climate impact of contrails (e.g., Lee et al. 2021), as described in Chapter 1. These modeling systems can also be used to forecast contrails. For either use, models require verification against observations at many levels. This chapter will outline the purpose of contrail forecasting systems, a description of current efforts, verification methods using observations, the elements of what a complete forecast system might look like, and the challenges and opportunities involved in building and operationalizing a contrail forecast system.

THE PURPOSE OF A CONTRAIL FORECAST SYSTEM

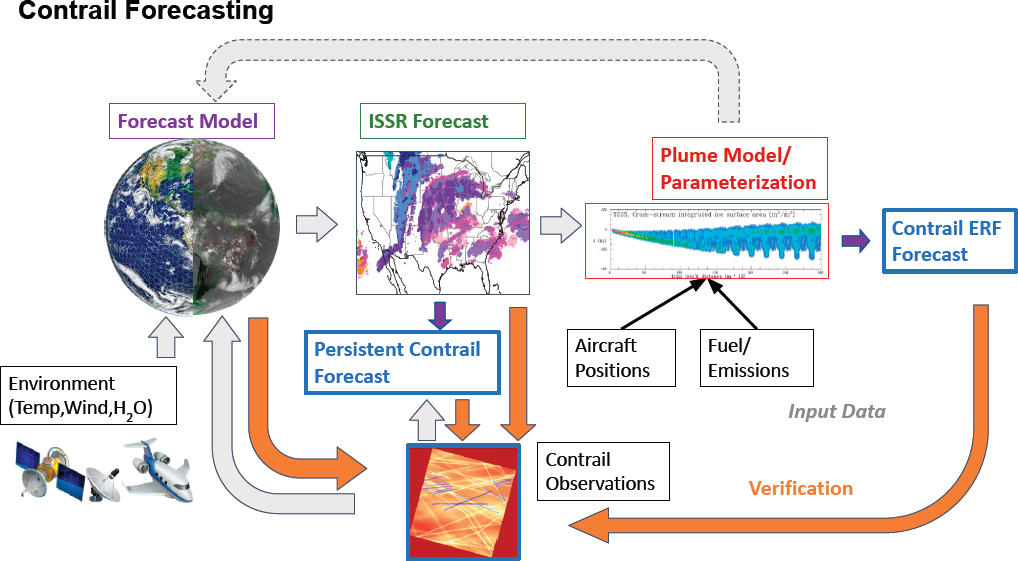

As previously discussed, the purpose of modeling contrails can be to assess the overall impact of contrails or to forecast specific contrails (or groups of contrails), which may be used in operational contrail avoidance. This involves several steps and inputs, as indicated in Figure 5-1. The structure of the system also depends on the outputs. The output could simply be whether a contrail forms at all (the military has an interest in this). The purpose could be to determine where contrails form and persist in ice-supersaturated regions (ISSRs). It could also include a representation of aviation locations and emissions to estimate the radiative forcing from an individual or set of contrails.

Regardless of the intent, a forecast system requires a series of computational elements described in detail in Chapter 4. First is a model of the atmosphere. To produce a forecast, the model must be initialized to the current state of the atmosphere, bringing in observations to the model with a data assimilation system. The purpose is to use all available observations (e.g., those described in Chapter 3) to describe the current state of the system. This essentially is a weather forecast system, or if run for a long time when the initial conditions do not matter, a climate model and climate projection. Such a model would produce locations of ISSRs at a given future time. This could be used directly, or with aircraft position and emission data, a representation of contrails in another model or a parameterization within the forecast model used. Note that if the plume/contrail representation is embedded in the forecast system, then the contrail would evolve with the model over time. The result of such a plume model or contrail parameterization would be an estimate of contrail lifetime, size (dispersion), and hence, the radiative forcing impact. Density of multiple or overlapping layers of contrails is also important (although it may be rare to fly exactly through the same plume). It may be possible to use data-driven methods trained on observations, models, aircraft positions, and contrail observations to directly calculate contrail effects from the environmental

SOURCES: (Earth and ISSR Forecast) Courtesy of NASA; (Plume Model/Parameterization) Used with permission of D.C. Lewellen, O. Meza, and W.W. Huebsch, 2014, “Persistent Contrails and Contrail Cirrus. Part I: Large-Eddy Simulations from Inception to Demise,” Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 71(12):4399–4419; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

properties. There are some efforts in this regard, but they also require use of similar observations (Chapter 3) and models (Chapter 4) for training.

Critical to such a system is evaluation or verification. Verification is a way of assessing and continuously refining forecasts checking against observations. This means that atmospheric and contrail observations need to be used a posteriori to evaluate forecast accuracy. Models are typically “evaluated” for their performance, while specific predictions are “verified” with trusted observations. In the case of a contrail forecasting system (also for a climate model with contrails), the forecasts can be evaluated in key ways.

First, observations of the atmosphere at the forecast time can be evaluated to see if ice supersaturation was predicted. Second, observations of contrails (e.g., from satellite or ground-based systems) can also be used to evaluate the forecast. This information ideally would feed back to improve the model, and/or determine where data gaps are most important. Currently, individual tracks are difficult to verify, due to a dearth of observations. Observations of temperature and humidity (Chapter 3) will be used for designing contrail forecast systems (Chapter 4) and verifying them. The observations from commercial aircraft of temperature, humidity, and any visible contrails are the ultimate evaluation of model skill. These are described in more detail in Chapter 3 and later in this chapter.

Note that the same methodology could be used to describe and evaluate a system to estimate the aggregate radiative effect of contrails. Detailed verification/evaluation of a forecast system could enable “hindcasts” to estimate aggregate effective radiative forcing (ERF), and has been used for such evaluations (e.g., Teoh et al. 2024).

The system could use a climate model with a contrail parameterization (e.g., Bock and Burkhardt 2016; Gettelman et al. 2021), or a plume model run offline (e.g., Teoh et al. 2024). Such estimates also can be “verified” against observations, often statistically (do they produce the right statistics of ISSRs, for example). The main challenge is having confidence in representing contrail cirrus clouds, which are harder to evaluate.

EXISTING CONTRAIL FORECAST SYSTEMS

Forecasting, nowcasting, and hindcasting of contrails and contrail-forming regions (ISSRs) has been undertaken for decades. The original motivation of such systems was related to military purposes to predict any contrail (not just persistent contrails) that might aid ground-based location of aircraft. Over the past two decades, research has used hindcast meteorological products that include parameters necessary to estimate ice supersaturation. More recently, observationally based nowcasting has been attempted using numerical weather prediction models. These efforts have revealed the difficulty of obtaining reliable ISSR nowcasts/forecasts from current systems discussed in Chapter 4.

ICE-SUPERSATURATED REGION NOWCASTING/FORECASTING

The U.S. Air Force and other armed forces around the world have long practiced contrail management. This has been motivated by the need to reduce detection or, in some cases, the objective of contrail avoidance. The U.S. Air Force produces contrail forecasts for its own use (AWS 1981; Peters 1993). However, where national security is not compromised, there may be the opportunity for the defense community to share learning with the climate science and aviation communities.

Recently, machine learning–based approaches to identifying contrails visible from geostationary satellites have been developed. There are now several research groups (including in the private sector) that are producing automated contrail identification from satellite imagery. This typically entails the development of a deep learning convolutional neural network architecture suitable for the task, combined with the creation of training and verification data sets. Training data sets are based on human-labeled contrails. Furthermore, methods of inferring the current ISSRs from observations of contrails, non-observation of contrails where there are known flights, and length-scale characteristics of ISSRs have been performed. This “estimation kernel” approach has the benefit of being based on observations, but forecasts are limited to extrapolations on the order of 30 minutes or less. Such approaches may be useful for tactical contrail avoidance, or adjusting flight plans that have been filed based on numerical weather prediction systems.

There are nascent ISSR-prediction systems based on numerical weather prediction models as well. The private-sector research company SATAVIA developed a numerical weather prediction tool for ISSR prediction based on a modified version of a numerical weather prediction model (Thompson et al. 2024). Meteo-France has an ISSR prediction model in development, and DWD (German meteorological service) is improving their forecast model to permit and predict ISSRs.

The skill of existing numerical weather prediction systems in predicting space-time-paired ISSRs has not been proven sufficient for operational implementation of navigational contrail avoidance, but may be sufficient for trials. Observational approaches using satellites are currently limited by the relatively low resolution of geostationary satellites. Weather model forecasts of ISSR regions are limited by (1) lack of flight-level in situ humidity data for constraining ISSR locations at flight altitudes, (2) poor parameterizations of cloud physics in weather models that do not permit ice supersaturation or represent ice nucleation, and (3) low vertical resolution of the models in the upper troposphere that cannot reproduce thin layered structures of ISSRs. Progress will depend on advancing weather forecasting codes for this purpose (e.g., using methods developed for global climate models, which do allow ice supersaturation and treat aerosol effects, with high vertical resolution in the upper troposphere), improvement in observations, and assimilation of those observations into forecast systems.

Finding: Current weather forecast systems are not sufficient for operational prediction of ISSRs.

CONTRAIL FORECASTING

Contrail forecasting is strongly contingent on the ability to forecast ISSRs, both in their existence and the extent of ice supersaturation. Forecasts currently have been based on contrail plume models coupled to weather forecast models, or simple heuristics with the Schmidt–Appleman criterion indicating regions of potential persistent contrail formation from weather forecast models. Several examples include the following:

- The U.S. Air Force produces an internal contrail formation product for its own internal use based on weather forecasts and a simple algorithm based on the Schmidt–Appleman criterion.

- The NASA SatCORPS group (NASA Langley) produces a persistent contrail-formation potential product based on geostationary satellite imagery, as well as contrail forecasts based on operational weather model forecast output (the Rapid Refresh and North American Mesoscale models from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration [NOAA]).1

- The German Aerospace Center (DLR) produces internal use forecasts of Schmidt–Appleman criterion temperature difference (like a dew point) and ice supersaturation computed from European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) Integrated Forecasting System (IFS) in support of operational flight campaigns. Information from contrail cirrus prediction model (CoCiP) simulations also provides forecasted contrail formation altitudes and contrail optical depth.

- Breakthrough Energy has created an organization, called Contrails.org, which publishes “real time” contrail coverage estimates2). These are based on using weather forecasts to initialize the CoCiP contrail plume model discussed in Chapter 4.

Contrail forecasting accuracy is most strongly affected by the ISSR forecasts—both existence and extent of ice supersaturation. To date, models for contrail forecasting have been repurposed models intended for retroactive analyses. At this stage, it is unlikely that individual ERF estimates made in forecast are accurate, whereas averages over large numbers of contrails have lower uncertainty because averages are better constrained by sampling across weather and aircraft variability from the microscale (contrail ice particle number) to the global scale (average frequency of ISSRs).

Since these methods are dependent on ISSR forecasts, they suffer from the same problems as current predictions of ISSRs—lack of in situ humidity data and the inability of forecast model resolution and cloud parameterizations to represent ISSRs. Furthermore, because ambient aerosols become more important with reduced soot, to estimate the potential future impact of contrail evolution and contrail cirrus, models would need to represent ambient aerosol and ice nucleation. This is done with much uncertainty in one of the general circulation models (Gettelman and Chen 2013) but is not present in any weather forecast system.

Finding: Current forecasts of ISSRs and persistent contrails are limited by (1) lack of flight-level in situ humidity data for constraining ISSR locations at flight altitudes, (2) poor parameterizations of cloud physics in weather forecast models that do not permit ice supersaturation, (3) low vertical resolution in the upper troposphere, and (4) no representation of ice nucleation linked to particulates (aerosols).

NASA already has a modeling system (the Goddard Earth Observing System [GEOS]) that has a comprehensive data assimilation system that can ingest humidity and temperature data from aircraft if available, along with current satellite observations, and has a good representation of ice supersaturation and ice nucleation. Furthermore, the Global Modeling and Assimilation Office has expertise in ice nucleation and the physics of the upper troposphere. This system could be used as a prototype for a contrail evaluation and forecast system. In addition, NASA has an observation system simulation experiment (OSSE) framework available to assess the utility of new observations on producing forecasts to determine if and where new observations could improve forecasts.

___________________

1 NASA, “Contrails,” Satellite Cloud and Radiation Property Retrieval System (SatCORPS) Group, https://www-pm.larc.nasa.gov/cgi-bin/site/showdoc?mnemonic=CONTRAIL_FORECAST.

2 Contrails.org, “Experience How Contrails Impact the Climate,” https://map.contrails.org, accessed December 1, 2024.

Finding: Reliable prediction of ISSRs is likely possible and feasible with evolution of current models and sufficient humidity and temperature data at flight level.

Recommendation: NASA should apply its current Earth system modeling efforts in support of simulating ice-supersaturated regions and contrails as a pathway to demonstrate the use of observations and advanced modeling tools for developing a contrail forecast and prediction system and estimating contrail radiative forcing.

EVALUATION METHODS

Evaluation of ISSR reanalyses/forecasts/nowcasts and contrail forecasts is necessary to quantify the data that may be used for contrail avoidance or any other approaches to contrail mitigation.

Much of the direct evaluation of ISSRs has focused on reanalyses. Gierens et al. (2020) first highlighted challenges in accurately estimating ISSRs using existing numerical weather prediction models with reference to airborne measurements from MOZAIC flights. This was followed up by Hofer et al. (2024), who used ERA5 predictions, finding that ISSR prediction is “very difficult.” Agarwal et al. (2022) evaluated reanalysis products ERA5 and MERRA-2 from almost 800,000 radiosondes. Results were interpreted as showing that persistent contrail formation at cruise altitudes is overestimated by a factor of 2–3.5 when using these products, and that a contrail lifetime metric is overestimated by 17–45 percent. They also estimate that the existing products incorrectly identify the regions of contrail formation and persistence 52–87 percent of the time. Thompson et al. (2024) also evaluated two operational forecasts (ECMWF IFS and NOAA Global Forecast System [GFS]) with their specialized model and found no skill in the GFS for predicting contrail formation, and only moderate skill for IFS or the specialized SATAVIA version of the weather research and forecasting model. Overall, the evaluations suggest that weather models alone in their current state of development are unlikely to be able to support operational contrail avoidance due to inaccuracies (operational aspects are discussed in Chapter 6).

Finding: Current attempts at operational forecasting of contrail locations and their radiative effects have low predictive skill, making their use in climate mitigation metrics questionable.

Additional scope for evaluation and potentially operation or real-time forecasting lies in satellite-based contrail observations. Furthermore, observations of contrails are critical for validation and verification of avoidance. This work was largely pioneered by Minnis et al. (2003). Systems such as GOES in mesoscale mode provide 500-m resolution with several minutes time resolution, sufficient for tracking individual contrails. NASA SatCORPs has also been archiving satellite data over North America from which to do contrail detection. New machine learning methods can automate detection of contrails as developed by Meijer et al. (2022), and attribution of contrail evolution to images over time (Hoffman et al. 2023), and data sets (e.g., OpenContrail; Ng et al. 2024) now exist to facilitate this work.

Finding: New machine learning methods for contrail identification from satellite imagery are showing great promise, but databases are currently fragmented, use different methods, and are not global.

Specialized research satellites with multi-spectral observations, such as NASA’s MODIS satellites, now transitioned to operational systems in low Earth orbit (LEO) (such as VIIRS), as well as new multi-spectral imagery from geostationary orbits (GEOs) soon to be available (see Chapter 3), can provide not just contrail locations (including some vertical information from brightness temperature), but some information on contrail microphysics (optical depth, and even some information on particle size). Furthermore, broadband radiation sensors (e.g., CERES and follow-ons) can provide direct measurements of individual and multiple contrail (scene-level) radiative forcing.

Finding: LEO and geostationary satellite data can be used with aviation location data and machine learning to improve model accuracy and is vital for model validation and testing.

As discussed in Chapter 3, the use of ground-based cameras has been proposed and early work has been done by DLR, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge University, Imperial College, and other research organizations. This may be useful for flights over land where camera networks could be created to supplement satellite or other observations. However, the utility of ground-based cameras is limited by the need for clear skies. Cameras are also useful for validating satellite-based instruments and can provide vertical information if matched to flight data. A consistent approach to evaluation and standard metrics for contrail observation and identification has not been developed.

Finding: Verification of contrail predictions requires good observations of contrails globally. This requires use of multiple satellites and ground-based cameras, in an open-source setting.

Recommendation: NASA should support development of a global contrail-observing system as a foundation for research, analysis, and future verification.

There has been discussion by private actors about building a specialized satellite or constellation of satellites for global observations of contrails. A purpose-built system could take the best aspects of low Earth orbit sensors for imaging and radiation with some humidity estimation, and advance contrail identification and potentially prediction (see below). NASA has valuable expertise in Earth observations for instruments and data processing algorithms (retrievals) that could assist with optimal development of such a system, and ensure public use of any data. This could massively advance evaluation (and possible prediction) of contrails. Should an international mitigation plan for contrails be put in place for verification, or should others decide to build a dedicated satellite system for contrail observation and prediction, NASA can collaborate to ensure quality science and open data access for any contrail observations.

Finding: Non-governmental and private-sector parties are exploring the deployment of a specific constellation of satellites to observe contrails. NASA is in a unique position to advise these efforts to ensure that they are best architected and that resulting data are accessible to maximize utility for the broader community.

WHAT WOULD A FORECAST SYSTEM LOOK LIKE?

Existing systems do not have all the elements of a forecast system illustrated in Figure 5-1, but systems could be of different types.

Perhaps the most obvious system uses a weather forecast approach, where a physical model produces a forecast of the state of the atmosphere, and then that state can be used to calculate ice supersaturation and further used as input to a model of aircraft contrails. Note that a weather prediction model and a climate model often contain the same physical representations, but a climate model is integrated sufficiently far from the initial conditions and with random variability introduced that it no longer is intended to reproduce the exact same final state from a set of initial conditions on each run. Weather models are also used as hindcasts in “analysis” mode: the data assimilation system uses observations to generate the most consistent possible state of the atmosphere, and this is saved for each time, generating a “re-analysis” that can be used as a uniform set of atmospheric conditions in the past (our “best estimate” of the system based on all available observations). Weather forecast models can be both regional and global. A typical global weather forecast model has horizontal resolution on the order of 10–20 km, while regional models are nearly an order of magnitude finer (1–5 km).

Current operational weather forecasting systems are not specifically designed to forecast ice supersaturation or contrails. They are designed for surface weather (temperature, precipitation) and many processes in the upper troposphere are not sufficiently represented in most weather models. This is also true of re-analysis systems used as “hindcasts” for assessing the overall contrail ERF. In addition, sufficient observations at flight level, particularly of humidity, are needed to be able to assimilate into weather models to get more accurate initial states. Very few models have representations of ice supersaturation; rather they assume ice clouds form at 100 percent relative humidity over ice (or slightly earlier to account for sub-grid variability). This makes it difficult to use current

forecast or reanalysis systems for ISSR and contrail forecasting. Climate models used for contrail estimates (e.g., Bock and Burkhardt 2019; Chen and Gettelman 2013) have more advanced representations of clouds and humidity that do represent ISSRs (e.g., Gettelman et al. 2010). There are now some advancements putting such representations into weather models, such as efforts in Germany to add ice supersaturation to their global weather model. A forecast of ice supersaturation with the Schmidt–Appleman criterion (sufficiently cold to form a contrail) would then indicate where persistent contrails would form (as is being attempted now by the U.S. Air Force, NASA SatCORPS, and DLR), or enable use of a plume parameterization/model (such as CoCiP used by pycontrails3).

In addition to a lack of representation of ice supersaturation, the lack of resolution in a forecast model is also a substantial problem. The horizontal resolution is not the major factor: most models have the ability to represent partial cloudiness generated by contrails, and the atmosphere in the upper troposphere tends to be well mixed in the horizontal on scales of several to tens of kilometers. However, the upper troposphere is very stratified in the vertical, and observations indicate ice supersaturation layers are several hundred meters thick (Spichtinger et al. [2003] found over Germany the average layer was 560 m with a standard deviation of 610 m), while a typical horizontal extent is 150 km (Gierens and Spichtinger 2000). Most weather and climate models have vertical resolution of 1 km or larger in the upper troposphere. An ideal contrail forecasting system should also have high vertical resolution (200–300 m or less) to resolve thin ISSRs.

Finding: A contrail prediction system requires a forecast model with representation of ice supersaturation, which necessitates accounting for ice supersaturation and higher vertical resolution.

Another approach to estimating ice supersaturation and related to verification is a “nowcast” approach: using satellite and ground-based observations of current contrails along with known aircraft altitudes to determine where ice-supersaturation regions are in flight lanes at the current time. It can also tell where there is subsaturation if aircraft are not forming contrails. This information can be propagated forward in time with forecasts of wind from weather models, or used directly. For example, contrail observations have been used to trial operational avoidance in experiments done by MIT and Delta Air Lines, where observations of contrails and known aircraft locations without contrails are being used to infer contrail-forming regions. Such an approach could not eliminate 100 percent of contrails as some fraction are needed as “tracer aircraft.” Observations of persistent contrails as noted above are needed for forecast verification in any event. New satellite products coming online with machine learning methods for automated detection of contrails (discussed in Chapter 3) would be useful in this regard.

As described in Chapter 4, the next step in such a system to estimate contrail radiative effects (either globally for climate estimates or for an individual contrail) would be to have a representation of contrails in the modeling system or to use a forecast (or analysis) to drive a contrail model. This requires knowledge of aircraft locations and an estimate of aircraft emissions (usually based on aircraft and engine type). The representation could be a simplified plume model—for example, CoCiP or APCEM (see Chapter 4), a simplified representation of ice cloud formation from aircraft (e.g., Bock and Burkhardt 2019; Chen and Gettelman 2013), or even just a rough estimate or assumption of the radiative effect of a cloud given the environmental conditions. On an aircraft-by-aircraft basis, contrails can be “nowcast” from the aircraft, with temperature and humidity sensors to measure the relative humidity and temperature in situ and/or with a camera to try to visualize behind the aircraft, or following other aircraft.

What input data would be needed for such systems? Currently weather forecast information comes from a wealth of sensors such as ground-based data, satellite observations, and profiles from weather balloons. In addition, as described in Chapter 3, wind and temperature data from aircraft are assimilated into forecast systems to improve the winds at flight level. This has been successful and valuable for aviation. Limited water vapor sensors currently on aircraft are also assimilated now, mostly on a profile basis (at climb and descent) to improve the profiling of water vapor in the atmosphere. These profiles have been shown to improve icing forecasts at lower altitudes. It is straightforward to assimilate aircraft flight-level data if new systems are added as discussed in Chapter 3. As with improvements in flight-level wind due to in situ observations, the addition of water vapor data to assimilation systems used in forecasting would dramatically improve ISSR forecasts, at least in the short term of 24 hours

___________________

3 See the pycontrails website at https://py.contrails.org, accessed December 1, 2024.

or so. Note that a simple analysis of the Schmidt–Appleman criterion and temperatures at aircraft flight altitudes indicates that at typical flight levels (30,000–45,000 feet), any water vapor concentration below about 20 ppmv is too dry to support contrail formation or ice supersaturation. This is much higher than the values of water vapor in the stratosphere, but it is simply sufficient to know that water vapor is less than 20 ppmv (see Chapter 3).

In addition, satellite information on contrail locations from current or future sensors could be used to locate persistent contrails. If the information were available in near real time, this is an indication of ice supersaturation (qualitatively) that could be used in modeling. It is also vital for verification of contrail forecasts. Ground-based cameras could be used in a similar manner, but would only be able to sense in clear sky conditions, while space-based systems could use infrared bands to discriminate between high and cold contrails, and lower, warmer clouds. Space- or ground-based “cameras” would ideally need information on aircraft altitudes to be able to locate ISSRs. Cameras on planes could also indicate contrail formation (or lack thereof) but not persistence. It is clear that a rear-facing camera on a wing or the tail would not be able to see a persistent contrail behind an aircraft, given aircraft speed. If an aircraft is traveling 900 km/hr, then it travels 15 km a minute and would not be able to see a persistent contrail behind it.

Finding: New observations for humidity and even contrail imagery would improve forecasting ISSRs and contrails.

An “ideal” contrail forecasting system structure would depend on the desired goal of the system. Most goals require forecasting ISSR locations. This is sufficient to determine regions of avoidance at the regional or individual flight level. The uncertainty on ISSR forecasting for larger regions, especially with the right input data and model, is tractable and reducible. The most critical elements noted above are probably in situ humidity data from aircraft assimilated into models that permit ice supersaturation and have relatively fine vertical resolution at flight altitudes. Persistent contrail observations with a consistent global system would also be useful for assimilating the current locations of ISSRs in flight regions and are vital for verification.

This is a prerequisite for forecasts of individual contrails. However, individual contrails and their radiative forcing are subject to a high degree of uncertainty due to smaller scale variations in the atmosphere, and the details of fuel and engine emissions characteristics (see Chapter 2). Estimating ice mass, optical depth, and radiative forcing are highly uncertain and would require more information (like the quantitative level of ISSR). Much less uncertainty would be attached to predictions of large ISSRs that intersect flight locations.

Note that predicting the evolution and fate of aviation-induced cloudiness (clouds affected by aviation particulate emissions not directly behind an aircraft) is even more difficult, and probably only tractable to do in a statistical or hindcast sense. These models must include detailed ice-nucleation and aerosol representations (e.g., Chen and Gettelman 2013). There are still large uncertainties in aviation-induced cloudiness (not even assessed in Lee et al. 2021), which need to be addressed with continued development and research using observations and models (likely a side effect of developing an observational and verification system for contrails). There are also important uncertainties in how alternative fuels that create different populations of particulate matter (discussed in Chapter 2) will alter the climate impact of contrails.

Finding: Understanding and predicting aviation-induced cloudiness requires global models designed to simulate aerosol evolution and ice nucleation, evaluated with measurements of aerosols.

CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES

This chapter has illustrated a roadmap for taking the observations described in Chapter 3 and models described in Chapter 4 and building a system designed to simulate where contrails will form, and their radiative effect. The systems would have two purposes: predicting contrails for mitigation purposes (and verification), as well as continued research into the fundamental physics of contrail effects to reduce uncertainties particularly in aviation-induced cloudiness and particulate effects that are relevant to future aviation engine emissions from new technologies and alternative fuels. This roadmap is still rough since the final objectives of a system need to be defined.

Forecasting of ISSRs and contrails with current weather forecast and contrail models is feasible and shows promise (e.g., Thompson et al. 2024). However, quantitative skill scores (mostly of ISSR predictions) are not high enough to reduce uncertainty in contrail impacts or to do reliable contrail avoidance. Furthermore, observations of contrails are not sufficient to verify contrail formation regions or to further constrain uncertainties in models, particularly in contrail plume models.

One need is to improve models, particularly for simulating ISSRs and the representation of particulate matter effects on clouds. Improvement of ice supersaturation and ice nucleation is needed. Models will also need higher vertical resolution in the upper troposphere than current global forecast systems. Note that this either requires engagement with weather forecast services, or duplicating their work in a specific system for forecasting contrails in the upper troposphere.

A second need is to improve observations used for (1) forecasting and (2) verification. For forecasting, there are good flight-level temperature data, but not sufficient flight-level humidity data, which likely will have to come from in situ sensors to get the vertically resolved information necessary. Satellite-based information on environmental state (temperature and humidity) is expected to improve over time but will not be sufficient on its own, because the vertical resolution of satellite instruments will never be able to sufficiently resolve the vertical gradient in water vapor.

Verification of contrails or avoidance requires observations of contrails. This is most usefully done by satellites and ground-based cameras. New machine learning algorithms are showing great promise in automated detection of contrails. Current satellite systems are useful for this, and future systems will be better. Ground-based imagery may be able to supplement and help evaluate/verify such estimates. Cameras on aircraft may also provide some information on instantaneous (but not persistent) contrails. This work may be advanced with a specialized constellation of small satellites to observe contrails, and some efforts are being discussed in this area. In any case, better coordination across current activities is needed to provide an open and evaluated global database of contrails (presence, and even optical and radiative properties). This is possible but would require focused investment and attention.

There are many uncertainties in contrail prediction, but forecasting of large ISSRs and prediction of the radiative impact of aviation emissions in those regions is likely possible to enable effective contrail avoidance. Verification of such predictions is also possible with appropriate observations. Uncertainty of contrail predictions for individual flights is very large, and verification of individual flight radiative effects is extremely difficult, and to some extent irreducible. Verification is critical for any individual flight mitigation and has a higher bar than verification of ISSR predictions in large regions with contrails. Uncertainty should not prevent the development of observations and forecast systems for contrail prediction.

There are several critical priorities to enable contrail mitigation in the near term with higher certainty. First are high-vertical-resolution forecasts, which require improving weather forecast models. Second is estimating high-RHi regions and ISSRs, which requires better in situ humidity observation, probably from commercial aircraft.

Finding: Highest priorities for enabling contrail mitigation systems are high-vertical-resolution forecasts of high RHi and ISSRs, which would likely require better forecast models that permit ice supersaturation and better in situ humidity observations.

To operationalize a contrail mitigation system, it would be best to focus on more certain contrails with known high impact. High-impact contrails have large positive radio frequency, which comes from long lifetime, high RHi, and certain conditions, like nighttime over warm surfaces. Development of contrail prediction systems could help refine high-impact contrail locations. For impact before the end of this decade, activities should focus on what can be done in the current air traffic control system, which likely means moderate vertical rerouting.

Chapter 6 will focus on operational concepts that can enable contrail mitigation within the aviation system.

REFERENCES

Agarwal, A., V.R. Meijer, S.D. Eastham, R.L. Speth, and S.R.H. Barrett. 2022. “Reanalysis-Driven Simulations May Overestimate Persistent Contrail Formation by 100%–250%.” Environmental Research Letters 17:14–45.

AWS (Air Weather Service). 1981. Forecasting Aircraft Condensation Trails. Technical Report AWS/TR-81/001. U.S. Air Force.

Bock, L., and U. Burkhardt. 2016. “The Temporal Evolution of a Long-Lived Contrail Cirrus Cluster: Simulations with a Global Climate Model.” Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 121(7):3548–3565.

Bock, L., and U. Burkhardt. 2019. “Contrail Cirrus Radiative Forcing for Future Air Traffic.” Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 19(12):8163–8174.

Chen, C.-C., and A. Gettelman. 2013. “Simulated Radiative Forcing from Contrails and Contrail Cirrus.” Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 13(24):12525–12536.

Gettelman, A., and C-C. Chen. 2013. “The Climate Impact of Aviation Aerosols.” Geophysical Research Letters 40(11):2785–2789. https://doi.org/10.1002/grl.50520.

Gettelman, A., X. Liu, S.J. Ghan, H. Morrison, S. Park, A.J. Conley, S.A. Klein, J. Boyle, D.L. Mitchell, and J.-L.F. Li. 2010. “Global Simulations of Ice Nucleation and Ice Supersaturation with an Improved Cloud Scheme in the Community Atmosphere Model.” Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 115(D18).

Gettelman, A., C.-C. Chen, and C.G. Bardeen. 2021. “The Climate Impact of COVID-19-Induced Contrail Changes.” Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 21(12):9405–9416.

Gierens, K., and P. Spichtinger. 2000. “On the Size Distribution of Ice Supersaturation Regions in the Upper Troposphere and Lowermost Stratosphere.” Annales Geophysicae 18:499–504.

Gierens, K., S. Matthes, and S. Rohs. 2020. “How Well Can Persistent Contrails Be Predicted?” Aerospace 7(12):169.

Hofer, S., K. Gierens, and S. Rohs. 2024. “How Well Can Persistent Contrails Be Predicted? An Update.” Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 24(13):7911–7925.

Hoffman, J.P., T.F. Rahmes, A.J. Wimmers, and W.F. Feltz. 2023. “The Application of a Convolutional Neural Network for the Detection of Contrails in Satellite Imagery.” Remote Sensing 15(11):2854. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15112854.

Lee, D.S., D.W. Fahey, A. Skowron, M.R. Allen, U. Burkhardt, Q. Chen, S.J. Doherty, et al. 2021. “The Contribution of Global Aviation to Anthropogenic Climate Forcing for 2000 to 2018.” Atmospheric Environment 244:117834.

Meijer, V.R., L. Kulik, S.D. Eastham, F. Allroggen, R.L. Speth, S. Karaman, and S.R.H. Barrett. 2022. “Contrail Coverage Over the United States Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Environmental Research Letters 17(3):034039. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac26f0.

Minnis, P. 2003. “Contrails.” Pp. 509–520 in Encyclopedia of Atmospheric Sciences (J. Holton, J. Pyle, and J. Curry, eds.). Academic Press.

Ng, J.Y.H., K. McCloskey, J. Cui, V.R. Meijer, E. Brand, A. Sarna, N. Goyal, C. Van Arsdale, and S. Geraedts. 2024. “Contrail Detection on GOES-16 ABI with the Opencontrails Dataset.” IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 62:1–14.

Peters, J.L. 1993. New Techniques for Contrail Forecasting. Technical Report AWS/TR-93/001. U.S. Air Force Weather Service.

Spichtinger, P., K. Gierens, U. Leiterer, and H. Dier. 2003. “Ice Supersaturation in the Tropopause Region Over Lindenberg, Germany.” Meteorologische Zeitschrift 12(3):143–156.

Teoh, R., Z. Engberg, U. Schumann, C. Voigt, M. Shapiro, S. Rohs, and M.E.J. Stettler. 2024. “Global Aviation Contrail Climate Effects from 2019 to 2021.” Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 24(10):6071–6093.

Thompson, G., C. Scholzen, S. O’Donoghue, M. Haughton, R.L. Jones, A. Durant, and C. Farrington. 2024. “On the Fidelity of High-Resolution Numerical Weather Forecasts of Contrail-Favorable Conditions.” Atmospheric Research 311:107663.