Developing a Research Agenda on Contrails and Their Climate Impacts (2025)

Chapter: 2 Aircraft Engine Emissions

2

Aircraft Engine Emissions

Chapter 1 noted that aircraft particulate emissions initiate formation of aviation-induced cloudiness. The purpose of this chapter is to explain the factors that influence these aircraft engine emissions, as well as the broader safety and operational factors that aircraft engines must be designed to address that interact with factors that influence emissions. It is organized by first introducing high-level issues, then addresses influences of combustor technology, ambient and engine operating conditions, and sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs). It then discusses effects of lubrication oil venting and how the temporal evolution of engine emissions influence contrail formation.

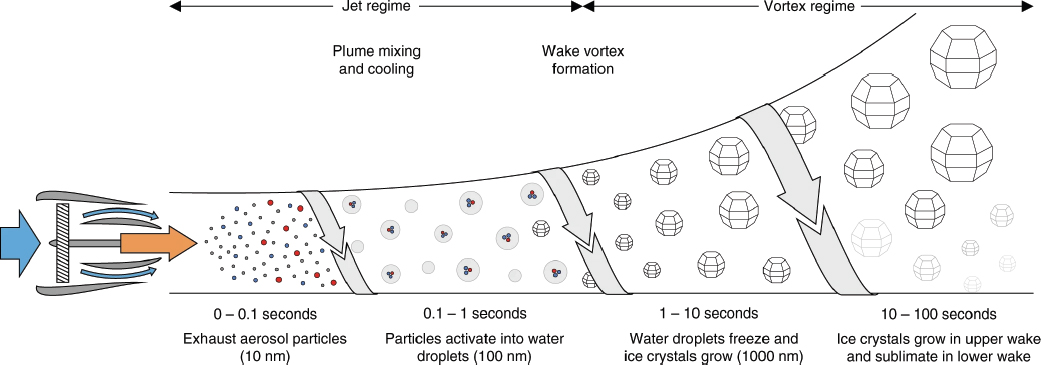

Combustion of hydrocarbon fuels leads to emissions of particulates and other precursors that serve as condensation nuclei for contrails (Figure 2-1). Combustor technology has a significant influence on these emissions and, hence, on contrail-forming tendencies. It is possible to significantly reduce these emissions with advanced combustion technologies and, in turn, decrease but not eliminate contrail-forming tendencies. The reason they do not eliminate contrail formation is that, even if combustion particulate emissions could be eliminated (such as with hydrogen as a fuel), ambient atmospheric particles, as well as trace amounts of oil vapor and aerosols vented from the engine lubrication systems, also may serve as condensation nucleation for contrail formation. In addition, the chemical composition of the fuel has a significant influence on contrail-forming tendencies. Conventional jet fuels contain sulfur and aromatic hydrocarbons, both of which are important sources of particulates relevant for contrail formation. Some SAFs contain fewer or no sulfur and/or aromatic compounds than conventional jet fuels and accordingly yield significantly decreased particulate emissions and contrail-forming tendencies, while other SAFs have sulfur and/or aromatic compounds at levels consistent with the current Jet A specification (so called drop-in fuels). Each of these items is further detailed in the rest of this chapter.

GENERAL COMBUSTOR EMISSIONS

Aircraft Engines

Aircraft engine combustors enable the conversion of chemical energy stored in jet fuels to thermal energy via exothermic chemical reactions. Jet fuels are a combination of hydrocarbons that meet the technical and certification requirements for aviation. Key performance metrics of the combustor are to fully burn the fuel (“combustion efficiency”), operate stably over the entire operational range of the engine power (“operability”), have a reason-

SOURCE: B. Kärcher, 2018, “Formation and Radiative Forcing of Contrail Cirrus,” Nature Communications 9:1824, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04068-0. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

ably uniform exit temperature profile (i.e., mild temperature gradients in the radial and azimuthal directions), and have low pollutant emissions.

The combustion process yields the main product species of gaseous CO2 and H2O, which are greenhouse gases. Long-lived CO2 is of primary importance for climate, while the impact of water vapor depends on whether it is emitted in the troposphere, where it precipitates relatively quickly from the atmosphere, or the stratosphere, where its longer lifetime can be climate relevant. This process also produces primary pollutants, such as soot or non-volatile particulate matter (nvPM) and sulfur dioxide (SO2). Soot particles are generated during the combustion process due to imperfect local mixing of available jet fuel droplets and available air. If the fuel contains sulfur, SO2 is produced during the combustion process and then is further oxidized to form sulfuric acid, which, along with unburned semi-volatile organic compounds, contributes to the formation of volatile particulate matter (vPM) downstream of the engine nozzle exit. The combustion process also produces nitrogen oxides (NOx), which arise due to chemical reactions of nitrogen and oxygen in the air across the flame. Combustor designs that decrease the residence time of fluid particles after the flame, or that minimize local hot spots due to imperfect mixing, lead to decreased NOx emissions. Additional potential combustor emissions that influence combustor design include carbon monoxide (CO) and unburned hydrocarbons (UHCs).

Aircraft emissions, specifically nvPM emissions and NOx, are regulated via the Environmental Protection Agency Integrated Pollution Parameter metric standards. These standards are set by the Committee on Aviation Environmental Protection of the United Nations’ International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) for the landing/take-off cycle conditions, versus in-flight or cruise conditions. As a result, aircraft combustor systems are optimized to meet these emissions regulations, while balancing other critical design criteria, such as efficiency, operability, heat release, exit temperature uniformity, and durability. The combustor design optimization process considers the air flow around and through the combustion system, the turbulent mixing effectiveness of fuel and air to reduce soot emissions, the mixing of air downstream of the flame to meet exit temperature quality requirements, and the use of cooling air to maintain combustor liner wall temperatures to ensure component life requirements. Modern engines have dramatically reduced the soot particle emissions over the past half century, as evidenced by ever lower smoke numbers being reported in the ICAO Aircraft Engine Emissions Databank.1 Mass and number emissions indices for nvPM have also been included in the Databank since 2020, which will allow for a more quantitative assessment of engine particle emissions improvements in the future; however,

___________________

1 See European Union Aviation Safety Agency, “ICAO Aircraft Engine Emissions Databank,” https://www.easa.europa.eu/en/domains/environment/icao-aircraft-engine-emissions-databank, accessed December 1, 2024.

these emissions indices are reported at sea-level static thrust conditions that may not be representative of cruise conditions. Recent research has attempted to extrapolate on-wing non-volatile particle emissions measurements made on the ground to cruise altitude measurements with some success for older technology engines burning conventional petroleum-based fuels (e.g., Ahrens et al. 2023; Durdina et al. 2017; Peck et al. 2013; Petzold et al. 1999; Stettler et al. 2013). It remains to be shown whether these ground-to-cruise correlation methods are applicable to more modern engine combustor technologies as well as sustainable or non-drop-in fuels. Similarly, it is also known that engine particle emissions are impacted by the maintenance history of a specific engine. Certification data in the ICAO Databank are for new engines and may not reflect the emissions of in-service engines across the fleet.

Aircraft nvPM and vPM, as well as ambient aerosol particles, provide the nuclei that enable water condensation and ice crystal growth under water-supersaturated conditions at cruise altitudes and, as such, are critical parts of the overall persistent contrail issue.

Finding: Contrail ice crystals form on volatile and non-volatile particles emitted from the aircraft engines as well as ambient particles in the upper troposphere.

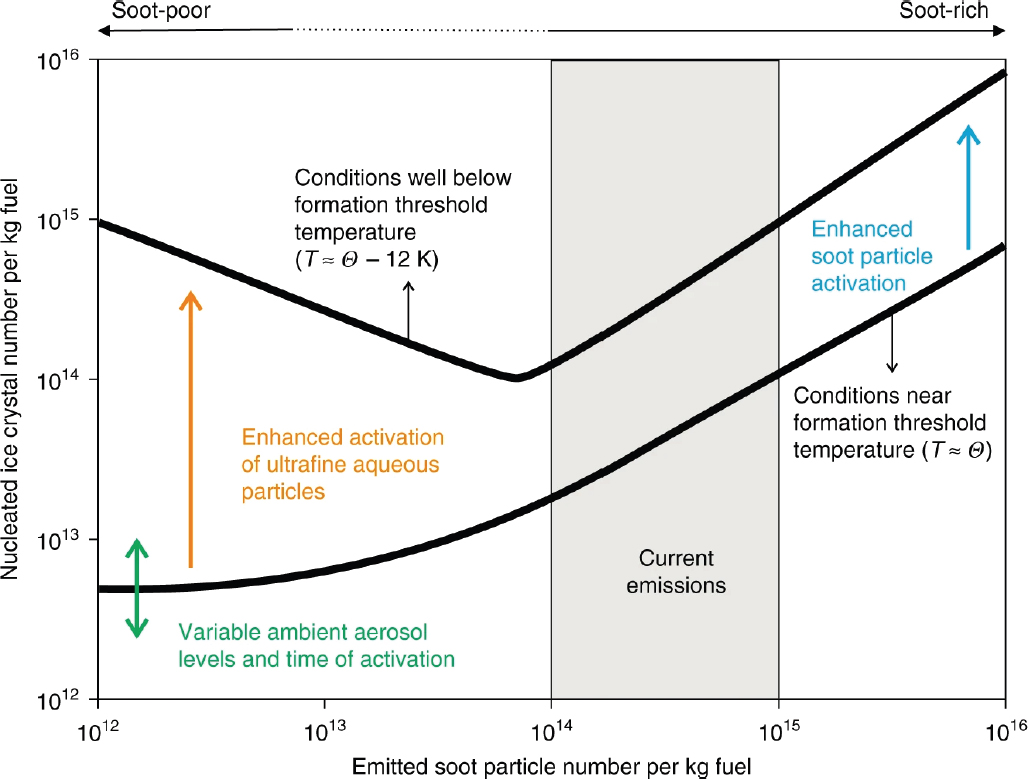

The number of ice crystals and their optical properties influence the optical depth, persistence, radiative forcing, and subsequent climate impacts of the contrail. These contrail microphysical properties are determined, in part, by the aircraft engine particulate size distribution, which often comprises two size modes: a smaller nucleation size mode dominated by numerous volatile particles (number mode diameter ~1–20 nm) and a slightly larger soot mode dominated by nvPM (number mode diameter ~20–40 nm). For aircraft engines with rich-burn, quick-quench, lean-burn (RQL) combustors, the number of emitted soot particles (>~1014 kg-fuel–1) thermodynamically determines the number of contrail ice crystals formed. Meanwhile, the more numerous, but smaller, nucleation-mode particles do not significantly impact the contrail microphysical properties due to the Kelvin effect. This “soot-rich regime” is shown in Figure 2-2 as a proportional scaling between ice crystal number and soot particle number. For these combustion systems, novel component design choices that yield lower nvPM emissions are expected to yield fewer contrail ice particles, lower optical depth, and reduced radiative forcing to first order.

Finding: Aircraft engine particulate emissions influence contrail properties and resultant radiative forcing.

Some modern aircraft engines include combustion systems that yield jet exhaust conditions in the “soot-poor regime,” with soot emissions up to three orders of magnitude lower than combustion systems that operate in the soot-rich regime. The lean-burn combustion technology in some current engines yields emissions in the soot-poor regime, while some RQL combustion technologies in other aircraft engines yield jet exhaust conditions in the transition region between soot-rich and soot-poor regimes. In the soot-poor regime, the number of emitted soot particles (<~1013–1014 kg-fuel–1) is insufficient to quickly uptake the condensing water vapor from the engine exhaust, and the plume water supersaturation may cause ambient aerosols and the smaller, nucleation-mode particle emissions to grow to become contrail particles. For atmospheric temperatures well below the contrail formation threshold, this means that further reductions in soot particle emissions (assuming constant emissions of nucleation mode or ultrafine particles from sulfur compounds or engine oil) might increase the number of contrail ice crystals formed (left side of Figure 2-2). However, the current number of observations within the soot-poor regime is very limited and other engine design and fuel considerations beyond the combustor (e.g., lubrication oil venting, fuel sulfur content) will be important in this regime.

The main sources of volatile particulate matter are sulfur oxides (SOx), condensable organics from incomplete combustion, and vented oil vapor and aerosols. The location of the oil vapor exhaust vent (e.g., near the core flow, bypass flow, or outside the nacelle) as well as the concentration of soot particles impact how the emitted semi-volatile oil vapor and aerosol contributes to vPM. If the oil emissions are in a cold flow (bypass duct or outside the nacelle), a distinct larger oil particle size distribution mode will be present and contribute (relatively) few condensation nuclei for contrail ice crystal formation. If the oil vents into the hot core flow, the oil will be vaporized and recondense onto existing soot particles or nucleate new particles.

SOURCE: B. Kärcher, 2018, “Formation and Radiative Forcing of Contrail Cirrus,” Nature Communications 9:1824, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04068-0. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Advanced aircraft engine technologies and changes in fuel composition (i.e., SAF or alternative fuels) could reduce the concentrations of nvPM and vPM and the resulting climate impact of persistent contrails and contrail cirrus.

Combustion Technology Effects

Assuming that all of the fuel is completely combusted, the major products of combustion—H2O, CO2, O2, and N2—are controlled by overall fuel chemistry and fuel-to-air ratio. In other words, the specific combustion technology does not significantly influence these major products. In contrast, minor combustion species, such as CO, NOx, particulates, and volatile organic compounds, are strongly influenced by combustion system architectures. This section provides an overview of these combustion system architectures and their influences on trace species emissions. Further details on these can be found in the references at the end of this chapter.

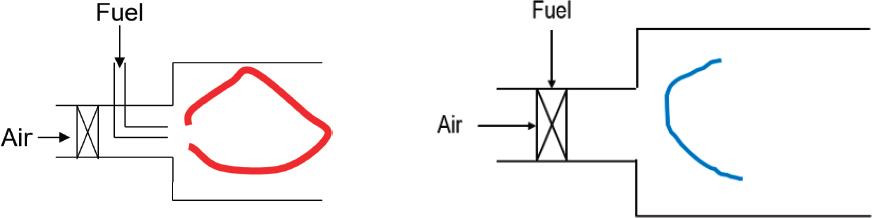

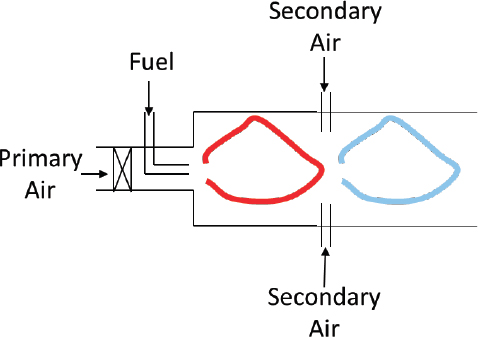

First, combustion systems can operate in premixed or nonpremixed mode. Notional sketches of each are provided in Figures 2-3 and 2-4.

In a premixed system, the fuel and air are premixed ahead of the combustor. For liquid-fueled combustors encountered in aviation systems, complete premixing requires pre-vaporization of the fuel, which introduces additional operational challenges associated with fuel coking and autoignition. For this reason, aviation combustors typically use architectures where the fuel is introduced at numerous injection points into the combustor, where the large mixing surface area promotes mixing of the fuel and air before combustion. Premixing provides two significant benefits—first, it avoids high-temperature overshoots in regions of stoichiometric combustion and, thus, minimizes NOx emissions. Second, hot fuel is always in the presence of oxidizer and so preferentially reacts to H2O and CO2 and produces relatively low soot emissions. As discussed later, in nonpremixed systems, hot fuel in the absence of oxidizer can pyrolize, starting the pathway toward solid, carbonaceous particulate emissions. Premixed systems are the de facto standard in low-NOx, ground-based systems using gaseous fuel. Their use in liquid-fueled systems is more limited, due to operational challenges described above.

Finding: Advanced engine technologies that reduce particulate emissions may play a role in mitigating contrail radiative forcing due to the influence of particulate emissions on contrail dynamics. These technology levers include advanced combustor designs and vent oil management.

The second major combustor classification is the manner of fuel staging—how the fuel is introduced and controlled (in terms of fuel flow rates and injection locations) versus the engine operating condition. While the overall

fuel-to-air ratio is set by the engine cycle (i.e., the desired turbine inlet temperature), the fuel and air introduction into the combustor is managed to enable cooling and emissions control.

A common historical combustor design approach is the RQL combustor technology. An RQL combustor is divided into two main zones. In the primary zone, the combustor is operated fuel rich, with a fraction of the overall air entering the front end of the combustor. The remaining air enters the combustor in the “quench zone” and reacts with the unburned fuel (which, due to its being at a very high temperature, is no longer jet fuel but has decomposed to a synthesis gas blend of H2 and CO). This fuel-rich zone leads to significant soot production. The majority, but not all, of this soot then reacts with air and is oxidized to CO2 in the lean zone. The part that does not react results in engine exhaust particulate emissions.

Many aircraft engines in service utilize lean-burn, premixed fuel systems where the primary zone is also operated in fuel-lean combustion. These strategies have demonstrated significantly reduced NOx and soot emissions.

Operating Conditions Effects

Engine emissions vary significantly across the range of engine operating conditions, as power is managed throughout the flight cycle. Lower power (idle and descent) conditions are associated with lower compressor pressure ratio; accordingly, combustion occurs at lower pressure and temperature conditions. Take-off conditions occur on the ground, where the ambient pressure is ~101 kPa; however, most aviation fuel is burned at cruise conditions, which occurs at an altitude where the ambient pressure is ~80 percent lower.

The design of the engine thermodynamic cycle also influences emissions. In a drive for improved thermal efficiency, design trends have increased engine overall compression pressure ratios and turbine inlet temperatures. This results in increased combustor flame temperatures, which is adverse for NOx emissions. Particulate emissions generally increase under conditions where nonpremixed and/or fuel-rich combustion occurs, where atomization and vaporization rates are lower. Both are influenced by pressure, temperature, and fuel composition. In RQL combustion systems, the primary combustion-zone fuel-to-air ratio peaks in rich, high-power conditions, which are also adverse for particulate emissions.

Fuel Composition Effects

Jet fuel composition has a significant influence on particulate emissions from the engine. Jet fuels consist of a range of hydrocarbons that meet the technical and certification requirements for aviation per ASTM standards D1655 and D4054. These requirements on jet fuels are due to their origins from fossil fuels and include a range of specifications around heating value, density, viscosity, and other properties. There is significant interest in synthesizing hydrocarbon jet fuels, known as SAFs, using renewable feedstocks (biomass, etc.). Since the source of SAF feedstocks is from the biosphere, vs petroleum-based conventional jet fuel, they are an attractive approach to reducing the CO2 impact of aviation.

For SAFs, it is common to differentiate between “drop-in fuels” and “non-drop-in” fuels. A drop-in fuel meets all of the ASTM specifications and certification requirements for commercial jet fuel (Jet A) and does not require the modification of current aircraft, engines, or fueling infrastructure for commercial use. However, non-drop-in fuels do not meet the fuel specifications for commercial use. Accordingly, a non-drop-in fuel formulation would need to be certified to ensure that there is no adverse impact to safety, performance, operability, or durability. Each type of aircraft and engine model would need to be certified for each non-drop-in fuel prior to commercial use. Moreover, separate fueling infrastructure at airports would need to be established to permit the segregation and safe handling, storage, and transportation of these non-drop-in fuels. Conventional jet fuels consist of a wide range of organic compounds. See Box 2-1.

Although aromatics, and particularly polycyclic aromatics, in jet fuel are significant sources of non-volatile particulate matter emissions, there are a number of practical reasons that make it difficult to simply remove them. Aromatic hydrocarbons exhibit bulk properties that enable jet fuels to meet ASTM specifications, where the primary focus is maintaining safety standards. Jet fuels are also used to cool critical hardware components, such as fuel nozzles, so their thermal properties must be sufficient for this purpose. Aromatic compounds have higher density

BOX 2-1

Conventional Jet Fuel Chemistry

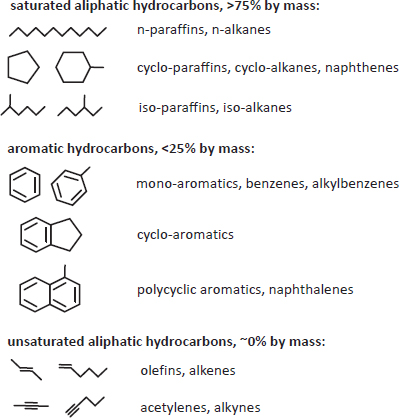

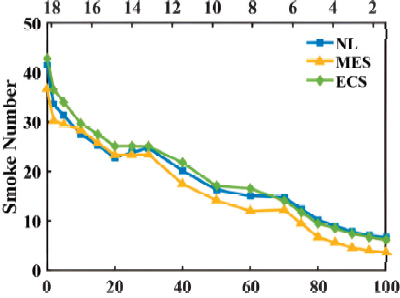

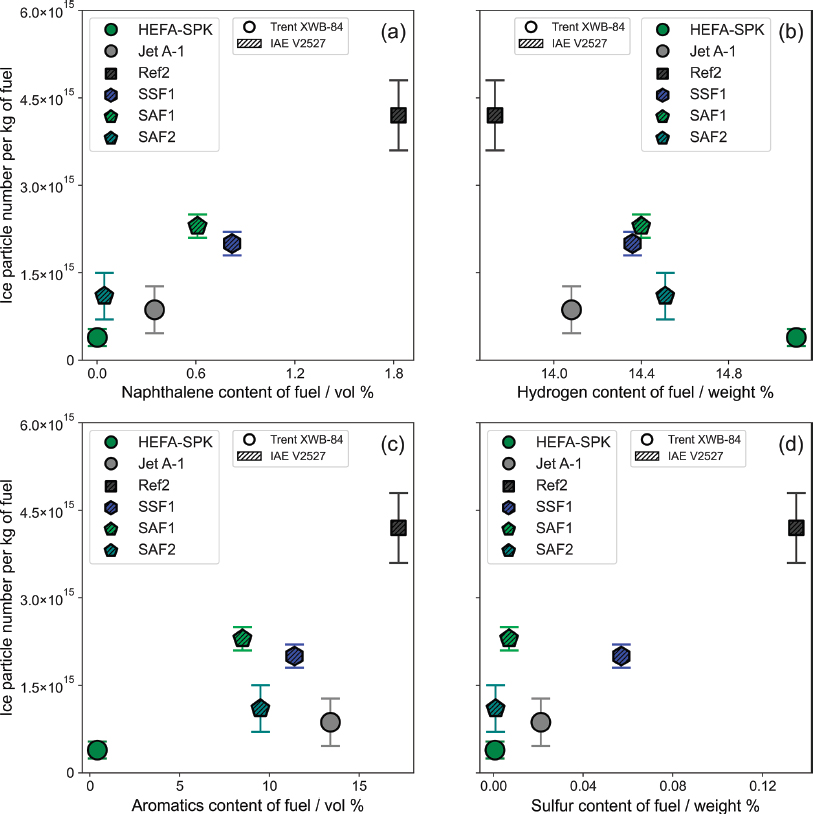

Conventional jet fuels consist of a range of hydrocarbons, as shown in Figure 2-1-1. The combustion of aromatic hydrocarbons generates soot particles that permit the formation of ice nuclei in aircraft exhaust plumes. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (e.g., naphthalenes) are known to be particularly important soot precursors. See Figures 2-1-2 and 2-1-3.

SOURCE: Produced by T. Lieuwen, I. Gupta, and B. Emerson, based on data from V. Undavalli, J. Hamilton, E. Ubogu, I. Ahmed, and B. Khandelwal, 2022, “Impact of HEFA Fuel Properties on Gaseous Emissions and Smoke Number in a Gas Turbine Engine,” Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2022: Turbomachinery Technical Conference and Exposition. Volume 3B: Combustion, Fuels, and Emissions, https://doi.org/10.1115/GT2022-82201.

SOURCE: R.S. Märkl, C. Voigt, D. Sauer, et al., 2024, “Powering Aircraft with 100% Sustainable Aviation Fuel Reduces Ice Crystals in Contrails,” Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 24(6):3813–3837, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-24-3813-2024. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

and higher energy per unit volume than paraffinic compounds, whereas paraffinic compounds have higher energy per unit mass than aromatic compounds. As a result, fuels that lack aromatic compounds will have considerable challenges meeting the density requirement of ASTM D1655. Highly paraffinic fuels may also have kinematic viscosity and coefficients of specific heat that are outside of the range of historical experience in aviation. Highly paraffinic jet fuels with no aromatics may also exhibit distillation temperature ranges that fall outside of the historical experience in aviation of jet fuels, which would impact aircraft engine operability. The absence of aromatic hydrocarbons in jet fuels also impacts elastomeric seal swelling characteristics and fuel gauging characteristics.

Fuel-bound sulfur molecules chemically react with available oxygen to produce SO2. A minor fraction of SO2 will rapidly oxidize into sulfuric acid, which can quickly condense to form sulfur-containing aerosols in the exhaust. These aerosols may serve as nuclei for water condensation and ice crystal growth in linear contrails in ice-supersaturated regions. However, removing sulfur from jet fuels by hydrotreatment also removes oxygenated organics that provide fuel lubricity. Thus, sulfur reduction in fossil jet fuel may lead to lower lubricity, adversely impacting the performance and durability of fuel pumps and valves, requiring fuel additives to mitigate.

SAFs manufactured using the Fischer–Tropsch, hydroprocessed esters and fatty acids (HEFA), and alcohol-to-jet pathways are synthetic paraffinic kerosenes and do not contain aromatic hydrocarbons or sulfur. As a result, the combustion of these synthetic fuels yields lower soot emissions than the combustion of conventional jet fuel, as well as zero SO2 emissions, substantially reducing the number of cloud condensation nuclei that permit ice crystal and contrail formation. These fuels are classified as non-drop-in fuels, and their commercial use would require modifications to existing aircraft and fueling infrastructure. The current ASTM specifications permit the blending (up to 50 percent for most pathways) of these synthetic paraffinic kerosenes with conventional, fossil-derived jet fuels, such that blended fuel properties satisfy the conventional fuel specifications. SAF blends that meet these ASTM D7566 fuel specifications and historical ranges for the fit-for-purpose properties (such as volumetric energy density, lubricity, kinematic viscosity, surface tension, the coefficient of specific heat, and electrical conductivity) are drop-in compatible with existing aircraft and fueling infrastructure. The ASTM D7566 requirements also include a minimum limit on the aromatic hydrocarbon concentration by volume of 8 percent, whereas conventional jet fuels do not have a minimum limit on aromatic hydrocarbon concentration.

There are several federally supported programs in place to both develop SAF, as well as to evaluate influences on engine emissions, operability, and stability. These include programs in the Department of Energy (DOE), the Department of Defense, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), and NASA (Colket et al. 2017; DOE 2024). Moreover, FAA supports the Commercial Alternative Aviation Fuels Initiative (CAAFI), which promotes alternative fuels that meet equivalent safety requirements of conventional jet fuels.2 Additionally, CAAFI’s Fuels Certification and Qualification and Research and Development teams are tasked with evaluating new sustainable aviation fuels per a standard approval process developed by ASTM and evaluating novel sustainable aviation fuel production pathways, respectively. NASA partners with FAA, universities, airframers, engine manufacturers, and fuel companies to evaluate the impact of alternative jet fuels on aircraft emissions and contrail properties.

Finally, there is a broader palate of potential future fuels that are not drop-in and are not currently used in aviation. Hydrogen combustion leads to only three major combustion products—H2O, O2, and nitrogen oxides. Hydrogen combustion does produce elevated water vapor emissions, but no direct particulate production from the fuel. However, contrails can still form due to nucleation of ambient environmental particulate matter. Particulates can also be produced from venting of the lubrication oil.

Also being considered as future fuels are other hydrocarbons, such as methane. There is significant experience in the ground power community with methane-air combustion. In this case, the lower carbon-to-hydrogen ratio and easier ability to premix both lead to reduced particulates. It is uncertain whether the contrail formation will be dominated by ambient particulate matter or engine-generated particulate matter for such.

___________________

2 See the Commercial Aviation Alternative Fuels Initiative website at https://www.caafi.org/about, accessed December 1, 2024.

LUBRICATION OIL VENT EFFECTS

Aircraft gas turbines require specially formulated oil to lubricate, cool, and provide corrosion resistance to the compressors, bearings, gears, and other turbomachinery components. The oil is recirculated through the engine systems, including a recycling loop that is designed to minimize oil consumption. During typical engine operation, the action of the rotating machinery in the lubrication system environment causes some small amount of oil to be mixed with air to form a mist. Typically, air/oil separator components recover the majority of the misted oil, but some small amount of the air/oil mixture is vented overboard to the atmosphere. This vented oil mist can have significant impacts on contrail formation, depending on the location of the breather vent, which impacts the number and size distribution of the emitted semi-volatile oil particles. Common design choices include a vent on the outside of the engine nacelle (e.g., as in Figure 2-5), into the bypass air, or at the tail cone of the engine core. Given the close proximity of the tail cone vent to the hot core exhaust flow, any condensed oil droplets likely evaporate as they mix with the hot combustion products—either recondensing on co-emitted soot (thermodynamically preferable) or forming new nucleation-mode particles via gas-to-particle conversion (less thermodynamically preferable). In this case, the amount of soot emissions may have a significant impact on the resulting distribution of aerosol-size oil droplets. Gas turbines operating in the soot-poor or no-soot (e.g., hydrogen) regimes are more likely to experience elevated oil-based new particle formation compared to gas turbines that operate in the soot-rich regime with ample soot surface area to act as a condensation sink. For breather vent locations in the engine bypass flow and outside of the nacelle, some or all of the vented, condensed oil droplets may survive as a larger, externally mixed, aerosol-size distribution mode, while the oil vapor condenses onto the oil particles, as well as onto the pre-existing soot and nucleation mode particles. However, the number of droplets in such a larger, externally mixed-size mode is unlikely to be significant for contrail formation, compared to typically much larger numbers of co-emitted nucleation-mode and soot-mode particles.

The oil contributions to particles larger than ~50 nm in diameter are readily apparent from aerosol mass spectrometer (AMS) measurements during emissions ground tests conducted over the past two decades (Timko et al. 2010; Yu et al. 2010, 2012, 2019). These studies, and also more recent thermal desorption–gas chromatography–mass spectrometry work, show substantial aerosol mass contributions from nearly intact forms of lubrication oil, indicating no apparent thermal degradation or chemical transformation of the oil (Fushimi et al. 2019; Yu et al.

SOURCE: Copyright © Boeing.

2010). Generally, a larger oil contribution to the particulate mass is observed at high engine thrust than at idle. An important limitation of these studies is the inability of current online and filter-based offline measurements to isolate and quantify the chemical composition of the smaller nucleation-particle-size mode. This is because the AMS is unable to transmit these particles through its inlet and because mass compositional techniques measuring the total aerosol mass will be weighted toward the largest, most massive, particles. While the nucleation-size mode contributes large numbers of particles (hence the potential importance of this mode for contrails in the soot-poor regime), the mass contribution from the nucleation-size mode is negligible. Previous ground test measurements of the vented oil contribution to engine particle emissions are limited and non-existent at cruise conditions relevant for contrail formation. More measurements are needed with particular emphasis on soot-poor engines.

Finding: Aircraft engine particulate emissions are strongly influenced by fuel composition, engine operating conditions, lubrication oil venting, and combustion system technology. Measuring the size-resolved chemical composition of these nucleation-mode particles is a major challenge, with gaps in predictive capabilities.

Finding: The largest impact of alternative fuels on contrails is likely to be through changes in the particulate content of aircraft exhaust.

Finding: For no- or low-soot-emitting engine technologies, and for fuel compositions with inherently low particulate formation tendencies (including SAFs), lubrication oil systems play an important role in the engine particulate emissions, which can serve as condensation nuclei for contrail ice crystals formed behind soot-poor and non-soot-emitting engines.

Finding: There are a number of emission sources that contribute to nucleation-mode particles, including fuel sulfur, unburned hydrocarbons, and lubrication oil. Developing the ability to identify the composition and roles of these contributors is needed to predict how changes in fuel composition and engine technology will influence engine particle emissions relevant for contrail formation. More measurements of the ice-nucleating properties of contrail-processed soot, and of ice nucleation concentrations in the upper troposphere, are needed to better constrain this issue.

Recommendation: NASA, in coordination with the Federal Aviation Administration, the Department of Energy, the Department of Defense, other relevant federal agencies, and the private sector, should support development of low-particle-emitting combustion technologies, as well as sustainable aviation fuels with inherently low particulate-formation tendencies.

Recommendation: NASA, in coordination with the Federal Aviation Administration, the Department of Energy, and the Department of Defense, should support laboratory and engine research studies to improve the understanding of how fuel composition, combustor technology, and engine operating conditions impact particulate emissions (volatile and non-volatile) and contrail properties.

PARTICLE IMPACTS ON CONTRAIL FORMATION AND DOWNSTREAM AEROSOL-CLOUD INTERACTIONS

Aircraft particle emissions are thought to impact clouds and climate via two pathways: first, through the formation and persistence of line-shape contrails and diffuse contrail cirrus (together referred to as “aviation-induced cloudiness”), and second, through contributing cloud condensation nuclei and ice nucleating particles to naturally occurring clouds (referred to as “aerosol-cloud interactions”).

First, particulates can nucleate water droplets that homogeneously freeze into contrail ice crystals if the conditions satisfy the Schmidt–Appleman criterion. These contrail ice crystals will persist if the ambient atmosphere is supersaturated with respect to ice, as discussed in Chapter 1. Given the high-water-vapor supersaturation with respect to liquid in the initial contrail-forming plume, it is expected that almost all the particles will uptake water if they

are above a certain critical size (somewhere in the range 10–40 nm depending on the local supersaturation in the highly heterogeneous plume), which is largely independent of particle composition. This has been verified with in situ observations of contrail ice crystal numbers compared to particulates; however, the flight studies to date have exclusively considered emissions from jet fuels with non-negligible amounts of fuel sulfur (either by burning sulfur-containing Jet A or nominally zero-sulfur alternative fuels with trace amounts of sulfur contamination introduced during post-refinery fuel transport and handling). Open research questions remain about contrail ice formation for a truly zero-sulfur fuel for aircraft engines operating in both the soot-rich and soot-poor contrail regimes.

Second, if contrails do not form immediately behind an aircraft, or once the contrail ice crystals sublimate, the soot particles have been hypothesized to act as ice nuclei for subsequent naturally occurring cirrus clouds that might form, although one recent laboratory experiment with aircraft soot does not support this (Testa et al. 2024). The properties of the emitted particles evolve in the atmosphere as the result of different processes. For example, particles that become part of a contrail may be changed (due to condensation and freezing) and redistributed in the atmosphere (due to sedimentation). Particulates also “age” in the atmosphere due to heterogeneous chemistry with reactive gases (e.g., NOx, ozone) and condensation and coagulation with both sulfate particles and organics. In addition to the formation of ice-nucleating particles, secondary gas-to-particle formation of hygroscopic sulfate and nitrate aerosols may contribute cloud-condensation nuclei to warm clouds; however, the contribution of aviation particles is likely to be much smaller than that from terrestrial sources. More measurements of the ice-nucleating properties of contrail processed soot and of ice-nucleating particle concentrations in the upper troposphere are needed to better constrain this issue.

Much of the uncertainty in the effects of aircraft emissions on ice particle concentrations for natural cirrus clouds stems from uncertainty in the ice-nucleating particles and their properties in the background atmosphere. Liquid aerosol particles (sulfate or liquid organic particles) typically require very high supersaturations to form ice via homogeneous freezing, whereas many solid or semi-solid particles can form ice at lower ice supersaturation but have very low number concentrations. The presence, or lack thereof, of background heterogeneous ice nucleation in the upper troposphere has a major control over contrail ice crystal concentration and, therefore, presents a major uncertainty in contrail radiative forcing, especially in the low-soot regime. There is low confidence in the calculation of the effect of aircraft soot on naturally occurring cirrus. It has only been assessed in a few studies (summarized in Lee et al. 2021). Moreover, it is difficult to attribute observed atmospheric soot in the upper troposphere directly to aviation operations, due to the significant amount of other non-volatile particles that may be found at flight levels due to convective transport of terrestrial and volcanic dust, as well as soot from other sources.

These aerosol effects are noted as “Aerosol Cloud Interactions” in Figure 1-3 in Chapter 1. Lee et al. (2021) did not put an estimate or an error range on these effects due to the diversity of approaches taken in the few studies that have investigated aerosol-cloud interactions from aviation particulates. Most estimates indicate a moderate cooling from sulfate and/or soot, with one sensitivity study (Zhou and Penner 2014) indicating a large warming or cooling depending on the treatment of background aerosols. Another study (Gettelman and Chen 2013) noted that aviation sulfate aerosols could alter liquid clouds and create a significant cooling effect if aerosols get to lower altitudes. Further work is needed to constrain and evaluate these model estimates.

Finding: Aviation-induced cloudiness from aviation particulates outside of a contrail is highly uncertain and needs to be better constrained with further development of modeling studies tied to more observations of aviation and background aerosols, in particular, heterogeneous ice nuclei at flight level.

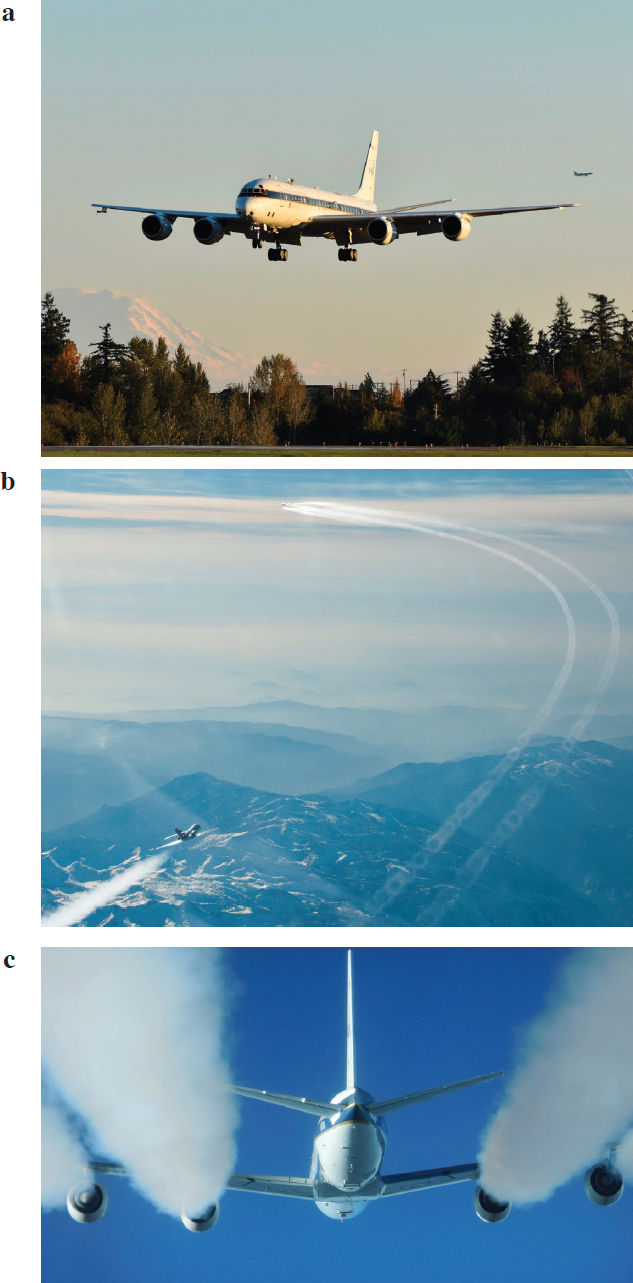

NASA has a long history of collecting airborne aerosol information in the upper troposphere, including from contrails specifically. Airborne science campaigns are exploring the impacts of alternative fuels and new combustor technology on aviation particulate emissions (Figure 2-6). For example, the NASA-led ACCESS flight test series in 2013–2014 demonstrated cruise altitude particle emissions reductions from burning a 50 percent SAF blend in the CFM56-2C engines of the NASA DC-8 (Moore et al. 2017). The ECLIF-2/ND-MAX flight test in 2018 that examined the soot-particle emissions from specially sourced SAF blends with varying levels of fuel aromatic and naphthalenic contents showed similar reductions in cruise soot-particle emissions for IAE V2500 series engines and linked these soot-particle reductions to contrail ice crystal reductions (Voigt et al. 2021). More recent tests

SOURCES: (a) Courtesy of NASA/Andy Barry; (b) Courtesy of NASA/Lori Losey; (c) Courtesy of NASA/Eddie Winstead.

have focused on contrails and cruise emissions for 100 percent SAF in RQL engines (e.g., DLR ECLIF-3; Märkl et al. 2024) and lean-burn engines (e.g., NASA Boeing ecoDemonstrator, DLR Airbus VOLCAN experiments). Large databases3 and statistics from many flights are needed due to the large variability of observed aviation particulates and contrail microphysics. Despite this track record, many of the current contrail and aerosol particle sensors being deployed by NASA and other research institutions for contrail studies are decades old, which places these capabilities at risk for future flight test projects. There is a need to update and maintain these aging sensor capabilities as well as to stimulate a robust commercial and academic pipeline of sensor development targeting high-altitude aerosol and contrail (i.e., small ice) measurements.

Recommendation: NASA should continue to collect in-flight observational data of contrails and cruise emissions (CO2, NOx, and ice-nucleating particles) from aviation that advance the understanding of the factors that influence contrail properties.

Chapter 3 discusses methods of gathering the necessary data to inform the models.

REFERENCES

Ahrens, D., Y. Méry, A. Guénard, and R.C. Miake-Lye. 2023. “A New Approach to Estimate Particulate Matter Emissions from Ground Certification Data: The nvPM Mission Emissions Estimation Methodology.” ASME Journal of Engineering for Gas Turbines and Power 145(3):031019. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4055477.

Colket, M., J. Heyne, M. Rumizen, M. Gupta, T. Edwards, W.M. Roquemore, G. Andac, et al. 2017. “Overview of the National Jet Fuels Combustion Program.” AIAA Journal 55(4):1087–1104.

DOE (Department of Energy). 2024. Pathways to Commercial Liftoff: Sustainable Aviation Fuel. https://liftoff.energy.gov/sustainable-aviation-fuel-2.

Durdina, L., B.T. Brem, A. Setyan, F. Siegerist, T. Rindlisbacher, and J. Wang. 2017. “Assessment of Particle Pollution from Jetliners: From Smoke Visibility to Nanoparticle Counting.” Environmental Science & Technology 51(6):3534–3541. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b05801.

Fushimi, A., K. Saitoh, Y. Fujitani, and N. Takegawa. 2019. “Identification of Jet Lubrication Oil as a Major Component of Aircraft Exhaust Nanoparticles.” Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 19(9):6389–6399.

Gettelman, A., and C-C. Chen. 2013. “The Climate Impact of Aviation Aerosols.” Geophysical Research Letters 40(11):2785–2789. https://doi.org/10.1002/grl.50520.

Kärcher, B. 2018. “Formation and Radiative Forcing of Contrail Cirrus.” Nature Communications 9(1):1824.

Lee, D.S., D.W. Fahey, A. Skowron, M.R. Allen, U. Burkhardt, Q. Chen, S.J. Doherty, et al. 2021. “The Contribution of Global Aviation to Anthropogenic Climate Forcing for 2000 to 2018.” Atmospheric Environment 244:117834.

Märkl, R.S., C. Voigt, D. Sauer, R.K. Disch1, S. Kaufmann, T. Harlaß, V. Hahn, et al. 2024. “Powering Aircraft with 100% Sustainable Aviation Fuel Reduces Ice Crystals in Contrails.” Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 24:3813–3837.

Moore, R.H., K.L. Thornhill, B. Weinzierl, D. Sauer, E. D’Ascoli, J. Kim, M. Lichtenstern, et al. 2017. “Biofuel Blending Reduces Particle Emissions from Aircraft Engines at Cruise Conditions.” Nature 543:411–415. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21420.

Peck, J., O.O. Oluwole, H.W. Wong, and R.C. Miake-Lye. 2013. “An Algorithm to Estimate Aircraft Cruise Black Carbon Emissions for Use in Developing a Cruise Emissions Inventory.” Journal of the Air Waste and Management Association 63(3):367–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/10962247.2012.751467.

Petzold, A., A. Döpelheuer, C.A. Brock, and F. Schröder. 1999. “In Situ Observations and Model Calculations of Black Carbon Emission by Aircraft at Cruise Altitude.” Journal of Geophysical Research 104(D18):22171–22181. https://doi.org/10.1029/1999JD900460.

Stettler, M., A.M. Boies, A. Petzold, and S. Barrett. 2013. “Global Civil Aviation Black Carbon Emissions.” Environmental Science & Technology 47(18):10397–10404. https://doi.org/10.1021/es401356.

Testa, B., L. Durdina, J. Edebeli, C. Spirig, and Z..A. Kanji. 2024. “Contrail Processed Aviation Soot Aerosol Are Poor Ice Nucleating Particles at Cirrus Temperatures.” Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 24(18):10409–10424. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-24-10409-2024.

___________________

3 See, for example, NASA, “Aeronautics Field Projects,” Aeronautics Research Mission Directorate, last modified April 5, 2022, https://science.larc.nasa.gov/aero-fp.

Timko, M.T., T.B. Onasch, M.J. Northway, J.T. Jayne, M.R. Canagaratna, S.C. Herndon, E.C. Wood, R.C. Miake-Lye, and W.B. Knighton. 2010. “Gas Turbine Engine Emissions—Part II: Chemical Properties of Particulate Matter.” Journal of Engineering for Gas Turbines and Power 132(6):061505.

Voigt, C., J. Kleine, D. Sauer, R.H. Moore, T. Bräuer, P. Le Clercq, S. Kaufmann, et al. 2021. “Cleaner Burning Aviation Fuels Can Reduce Contrail Cloudiness.” Communications Earth and Environment 2(114).

Yu, Z., D.S. Liscinsky, E.L. Winstead, B.S. True, M.T. Timko, A. Bhargava, S.C. Herndon, R.C. Miake-Lye, and B.E. Anderson. 2010. “Characterization of Lubrication Oil Emissions from Aircraft Engines.” Environmental Science & Technology 44(24):9530–9534.

Yu, Z., S.C. Herndon, L.D. Ziemba, M.T. Timko, D.S. Liscinsky, B.E. Anderson, and R.C. Miake-Lye. 2012. “Identification of Lubrication Oil in the Particulate Matter Emissions from Engine Exhaust of In-Service Commercial Aircraft.” Environmental Science & Technology 46(17):9630–9637.

Yu, Z., M.T. Timko, S.C. Herndon, R.C. Miake-Lye, A.J. Beyersdorf, L.D. Ziemba, E.L. Winstead, and B.E. Anderson. 2019. “Mode-Specific, Semi-Volatile Chemical Composition of Particulate Matter Emissions from a Commercial Gas Turbine Aircraft Engine.” Atmospheric Environment 218:116974.

Zhou, C., and J.E. Penner. 2014. “Aircraft Soot Indirect Effect on Large-Scale Cirrus Clouds: Is the Indirect Forcing by Aircraft Soot Positive or Negative?” Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 119(19):11303–11320. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JD021914.