Personal Protective Equipment and Personal Protective Technology Product Standardization for a Resilient Public Health Supply Chain: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 2 The Role of Standards in a Resilient PPE/PPT Supply Chain

2

The Role of Standards in a Resilient PPE/PPT Supply Chain

Key Messages from Individual Speakers1

- A standard is essential to a high-performing supply chain because the manufacturer, distributor, specifier, end user, and regulator are all using the same language. (Shipp)

- It is important to enhance the engagement of diverse partners when developing standards. (Gillerman, Shipp)

- Standards can enable supply chain data to be interoperable and can be useful for the entire enterprise of users seeking to understand the applicability and accessibility of PPE. (Gillerman)

- Medical product supply chains are complex, multistage, global systems that involve people, processes, technologies, and policies, and as a result, there is no one-size-fits-all strategy for building resilience into medical product supply chains. (Ergun)

- Standards could be written in terms of performance, without material specifications that are unnecessary for the performance of a product. (Shipp)

- There are no standards for public use of PPE along the entire supply chain. (Veenema)

___________________

1 This following list of key messages is the rapporteurs’ summary of points made by the individual speakers identified, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. They are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

The second session laid the foundation for the remainder of the workshop by discussing the observations made in the draft annual report from the Product Standardization Task Force2 that was established as part of the National Strategy for a Resilient Public Health Supply Chain.3 This session’s speakers walked through the process of setting standards along the personal protective equipment (PPE)/personal protective technology (PPT) supply chain, from raw materials to design and manufacturing through to transportation and storage and distribution to users. To introduce the session, Tener Veenema, senior scientist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, discussed some of findings in the Product Standardization Task Force’s draft report, which she said was expected to be released in the next few weeks.

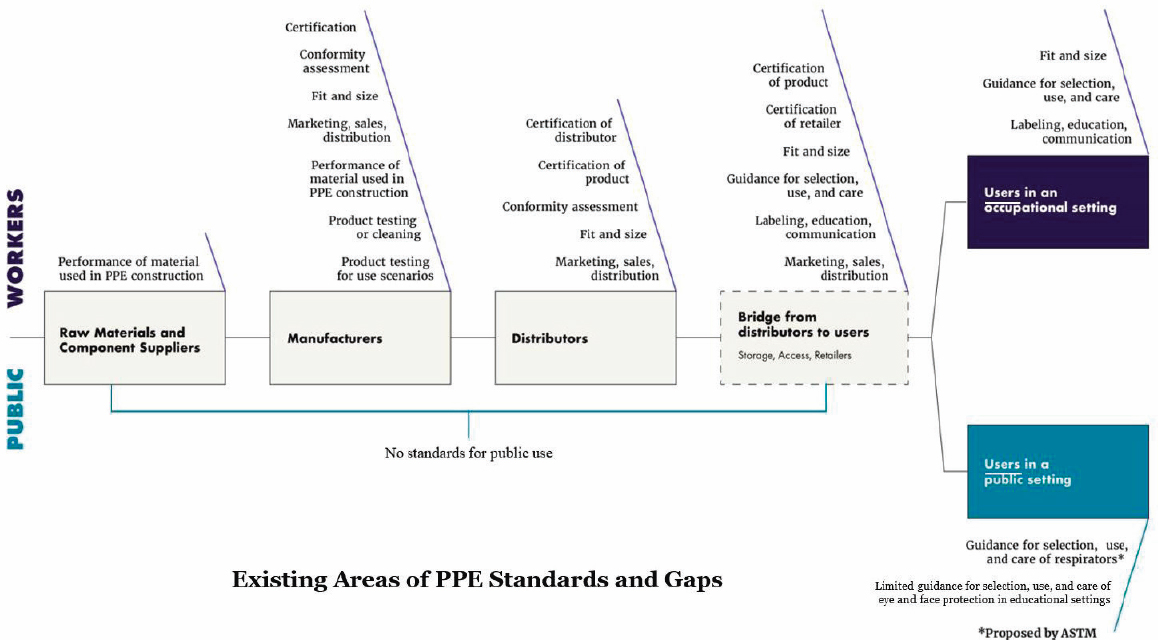

The task force’s findings, said Veenema, highlighted several types of gaps that exist in PPE and PPT standards, including gaps related to the level and type of protection the product offers, those associated with the technology applied to the product, and those relevant to product testing capabilities. Other standards gaps were identified in the areas of education and information sharing with end users about how to select, use, and care for PPE, as well as about a product’s life span and the impact storage has on the product. The task force report suggested that the low confidence among end users in how PPE adheres to standards may also be a gap. “When we look at relating the gaps identified by the task force to the [PPE] supply chain, we can see that there are gaps along the entire process, right from the beginning of raw materials through to end use,” Veenema said. Figure 2-1 illustrates some of the high-level gaps the task force identified that sit along the PPE supply chain.

The task force’s draft report indicates that the standards gaps begin with the performance of raw materials used to construct PPE. In the manufacturing phase, there are standards gaps pertaining to certification; conformity assessment; fit and size; marketing, sales, and distribution; the performance of the raw materials; and product testing for cleaning and various use scenarios. In the distribution stage of the supply chain, there are gaps in standards relating to certification of the distributor; certification of the product; conformity assessment; fit and size; and marketing, sales, and distribution. The same gaps exist when bridging distribution to end users, said Veenema, and there are additional gaps regarding

___________________

2 This Task Force is part of the Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Joint Supply Chain Resiliency Workgroup (Joint SCRWG) that was established as part of the National Strategy for a Resilient Public Health Supply Chain. Additional information is available at https://aspr.hhs.gov/newsroom/Pages/SupplyChain-9Mar2022.aspx (accessed May 2, 2023).

3 Available at https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/legal/Documents/National-Strategy-for-Resilient-Public-Health-Supply-Chain.pdf (accessed May 2, 2023).

SOURCE: Presented by Tener Veenema on March 1, 2023, at the PPE/PPT Standardization for a Resilient Public Health Supply Chain Workshop. Figure created based on data provided in Joint Supply Chain Resilience Working Group, 2022 (unpublished).

certification of the retailer; PPE selection guidance; guidance on use and care of the products; and PPE labeling, education, and communication.

The task force’s gap assessment considered two types of end users. For users in an occupational setting, standards gaps exist around fit and size; guidance for PPE selection, use, and care; and product labeling, education, and communication. For users in a public setting, Veenema said there is a notable gap in terms of a lack of standards for PPE selection, use, and care of respirators. “There are [almost] no standards for public use along the entire supply chain, something that must be addressed,” she said. The standards for public use that do exist focus on limited types of PPE used in educational settings, such as in chemistry or biology classroom laboratories (ANSI and ISEA, 2020). While ASTM has proposed guidance for the selection, use, and care of respirators by the public, no standards are yet in place. Moreover, ASTM’s guidance is limited to respirators and does not include other types of PPE.

INDUSTRY PERSPECTIVE ON THE ROLE OF STANDARDS

Dan Shipp, a consultant in standards, conformity assessment, and regulation of PPE and PPT, opened his comments by defining a standard as a document, established by consensus and approved by a recognized body, that provides rules, guidelines, or characteristics for a product or process for common or repeated use. This definition, he said, embraces all of the key elements of standardization, which he listed as consensus, recognition, contents, and applicability. PPE standards specifically set minimum performance requirements; contain guidelines for proper use; establish classifications based on characteristics such as size, fit, and level of protection; and contain test methods to determine whether a product meets these performance requirements.

For example, said Shipp, the classification standard for an N95®4 respirator (e.g., a disposable filtering facepiece respirator [FFR] or reusable elastomeric respirator with N95 filter cartridges) states it must filter out 95 percent of particles of a certain size in an oil-free atmosphere. Other standards focus on sizing, selection, use, care, cleaning, maintenance, storage, and disposal of the PPE product, as well as measuring contaminants in the air, calculating fall distance, and determining other characteristics that are important for ensuring the product delivers on its promise of protection.

In terms of where standards come from, Shipp said the government can set standards, such as the 42 CFR Part 84 standard for respiratory protection devices.5 Such standards are developed through notice and

___________________

4 N95 is a certification mark of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and is registered in the United States and several international jurisdictions.

5 Approval of Respiratory Protective Devices, 42 CFR § 84 (June 8, 1995).

comment rulemaking and are a part of the federal regulatory structure. In the United States, voluntary consensus bodies such as ASTM or the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) develop most standards related to PPE. Other sources of standards include trade associations, professional societies, and consortia assembled to develop specific standards. The common characteristic of these organizations is that they have rules guiding the way they operate based on broadly accepted principles of consensus, including balance of interests, transparency, openness, impartiality, effectiveness, relevance, timeliness, and coherence. Such standards, said Shipp, are voluntary in that a voluntary process develops them and manufacturers, users, and regulators adopt them voluntarily. However, when regulatory agencies adopt voluntary standards, they can have the force of law similar to a government-originated standard.

Developing a PPE standard, said Shipp, starts with identifying a need in terms of a potential hazard, exposure, or injury if the PPE fails, as well as the nature of the activity being done when individuals encounter a hazard. For example, workers face hazards that can cause injuries from impacts, cuts, burns, falls, and electric shock and from exposure to extreme heat or cold, flames and smoke, noise, chemicals, biohazards, and radiation. Workers need PPE to protect their heads, their eyes and face, their hearing, lungs, hands, feet, skin, and bones, said Shipp, and they need PPT to prevent fall injuries and to make potential hazards visible by day and night. “Whatever the need, there are processes in place for getting the standard from concept to completion,” said Shipp. He noted that anyone with knowledge of the product, process, or service; an understanding of how to establish common performance characteristics and guidelines; and a willingness to devote time, energy, and expertise to the process can participate in formal efforts to establish common performance characteristics and guidelines.

The end product of the standards-generating process, he explained, is a document that is essential to a high-performing supply chain because it helps ensure that the manufacturer, distributor, specifier, end user, and regulator are all using the same language. “Standards are the shorthand of commerce,” said Shipp. He suggested thinking of gaps identified during the course of the workshop’s discussions as opportunities to improve standards or develop new standards where they are needed. “You and your organizations need to be part of the process.” he said. “Encourage knowledgeable people in your organizations to participate in standard development.” On a final note, Shipp referred the workshop participants to online resources on the standards development processes for organizations such as the American National Standards Institute (ANSI), ASTM, and the International Safety Equipment Association (ISEA).

FEDERAL GOVERNMENT PERSPECTIVE ON THE ROLE OF STANDARDS

Gordon Gillerman, director of the Standards Coordination Office at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), explained that the National Technology Transfer and Advancement Act of 19966 instructs federal agencies to participate in developing voluntary consensus standards and to use those cooperatively developed standards when the standards meet agency needs rather than developing government-unique standards. Office of Management and Budget document A1197 provides the implementation guide for federal agencies. This is an important document, said Gillerman, because it provides the government’s perspective on standards as informed by technical developments and efficiency, and by international trade obligations outlined in the World Trade Organization Technical Barrier to Trade Agreement8 and other trade agreements. These agreements view standards as one of the primary vehicles that governments can use to satisfy regulatory needs while minimizing barriers to trade for industry.

Gillerman agreed with Shipp on enhancing the engagement of diverse partners when developing standards. “That always yields better standards,” said Gillerman. Industry, he noted, is generally an engaged participant in the standards processes because those standards have a direct material effect on their businesses. However, barriers for researchers, test laboratories, academia, practitioners, and small- and medium-sized enterprises could be reduced to enable their participation in the standards process to ensure that the best technical ideas are included in the consensus process.

Standards are not just relevant for product performance. “We tend to think about PPE and PPT standards as the standards for the mask, the hard hat, and the respirator,” said Gillerman, “but there are also standards for fit, application, care, and maintenance that are very important.” Standards are also applicable to and beneficial for the supply chain, he added. Standards can enable supply chain data to be interoperable and be useful for the entire enterprise of users that seek to understand information about the applicability and accessibility of PPE.

Another area for consideration, said Gillerman, relates to how U.S. standards interface with the standards of other countries. There are several international standards-setting processes, including those established

___________________

6 National Technology Transfer and Advancement Act, 15 CFR § 3701 (March 7, 1996).

7 Available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Circular119-1.pdf (accessed May 2, 2023).

8 Additional information is available at https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/tbt_e/tbt_e.htm (accessed May 2, 2023).

by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and ANSI. “As we look at the value of consulting with the international standards system in this particular area, we can think about whether we should draw upon those standards for our requirements and whether we should look to align the technical requirements of standards used for PPT and PPE in the United States with those standards,” said Gillerman. “At a minimum, we should be keeping an eye on those standards to avoid developing mutually exclusive requirements.”

Industry, Gillerman noted, benefits from a low barrier to the global marketplace. However, creating standards with technical requirements that force industry to produce products for the U.S. marketplace that differ from products they want to sell in other markets can hamper supply and create supply chain issues. In that respect, he said that mapping the technical requirements in U.S. standards to those in international standards for PPE and PPT would be valuable. He suggested that a thoughtful regulatory assessment of the nation’s capability to minimize barriers to using PPE and PPT that have been demonstrated to meet the requirements of other countries’ regulatory systems could be beneficial in surge moments during emergencies, when PPE supplies may be strained.

Next, Stuart Evenhaugen, acting strategy branch chief at the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR) within Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), spoke about Executive Order 14001 on a sustainable public health supply chain, which President Joe Biden issued on January 21, 2021 (The White House, 2021). This executive order called for creating a National Strategy for a Resilient Public Health Supply Chain. This decade-long strategy contains three main sections. The first defines a public health supply chain and supply chain agility and resilience. The second section presents goals and recommendations for specific actions the federal government could take in partnership with the private sector. The third section looks at lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic and acknowledges that the executive order calls for resilience against future pandemics.

There can be many ways to measure or define resilience, said Evenhaugen. For the National Strategy, the three pillars of resilience were taken to be robustness, visibility, and agility. Robustness, he explained, concerns the diversity and redundancy of sourcing materials and bolstering the diversity of those sources through onshoring, nearshoring, and offshoring. Visibility refers to transparency, supply chain illumination, and a better ability to see problems in the supply chain. Agility, he said, is where reactive capacities come into play. He noted that each element

depends on how behavior affects resilience in that resilience depends on decisions, networks, and the experience of the people involved.

Evenhaugen also highlighted that standards can support innovation within supply chains from both a product and process perspective. One example of process innovation is the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) owning the trademark to N95 respirators, which has allowed for more enforcement discretion for counterfeit products. Another process innovation, he pointed out, would be to better understand the intersection of the different elements of a supply chain (e.g., transportation, storage, distribution) to enhance the allocation of goods. For example, during the pandemic, the PPE supply chain experienced demand shocks as a result of surges in demand. This meant that although some PPE products were moving through the supply chain, they were not always evenly distributed to those in need. As a final comment, Evenhaugen noted that the 2022 update of the National Biodefense Strategy included an action item calling for an assessment of the public health and health care workforce, other critical infrastructure workers, and essential workers to better outline the potential demand for N95 respirators and other PPE in the event of another pandemic (ASPR, 2022a; The White House, 2022).

PPE SUPPLY CHAIN AND THE ROLE OF STANDARDS

The final speaker for this session, Özlem Ergun, College of Engineering distinguished professor and associate chair for graduate affairs in mechanical and industrial engineering at Northeastern University, reviewed some findings and recommendations from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s consensus report Building Resilience into the Nation’s Medical Product Supply Chains (NASEM, 2022a). One insight the report emphasized was that medical product supply chains are complex, multistage, global systems that involve people, processes, technologies, and policies. Furthermore, medical products themselves fall into many categories and subcategories. As a result, there is no one-size-fits-all strategy for building resilience into medical product supply chains. “All of these types of products come with different supply chains, different market structures, and different risk profiles,” said Ergun. “Given these differences, there is a challenge to match resilience measures to products in a cost-effective manner.”

Another insight from the consensus report that Ergun shared was that current medical product classification schemes are based on clinical importance, but such schemes should also include short-term risk in these classification models. To address this problem, the consensus committee recommended that the term “supply chain critical medical products” should apply to those products that are both medically essential and

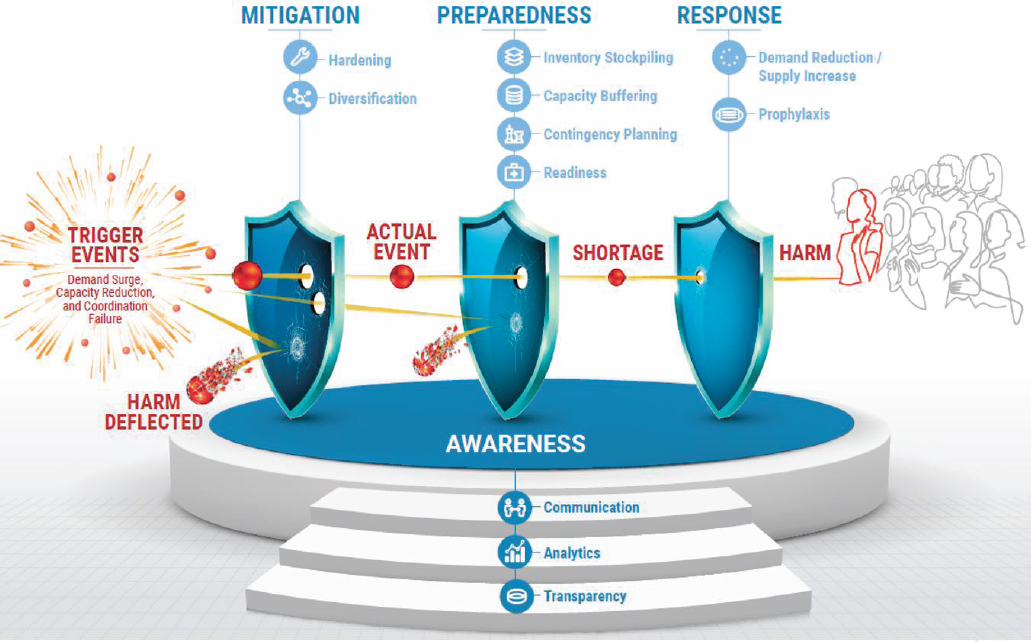

SOURCE: Presented by Özlem Ergun on March 1, 2023, at the PPE/PPT Standardization for a Resilient Public Health Supply Chain Workshop (NASEM, 2022a).

vulnerable to shortages. Figure 2-2 presents the framework for resilient medical supply chains that the consensus committee developed based on these insights. This framework divides resilience measures into four categories, starting with an awareness measure that serves as a precursor to all the other resilience measures. Awareness measures, Ergun explained, require data sharing, data availability, and visibility in the supply chain to enable better decisions and help convert data into actionable information that can be communicated at the right time with the right partners.

The framework depicts the path from a trigger event to public harm, with successive layers of protection, represented as shields, between. For example, when an event occurs that could disrupt the supply chain (i.e., the trigger event), the right set of mitigation strategies, such as hardening the production process or diversifying the supply chain, can act as shields and offer protection by reducing some of the potential harm to the public that can result from a supply chain disruption (i.e., the actual event). However, said Ergun, there are no shields (i.e., measures) without holes. Some impacts to the supply chain will bypass the mitigation measures, resulting in a supply chain disruption. The subsequent preparedness measures to manage this disruption include stockpiling, capacity buffering, contingency planning, and readiness. Despite best attempts, some events will still bypass the preparedness measures and create shortages. The final measure, the response to an event, will help reduce the harm to individuals and society even in the event of a shortage.

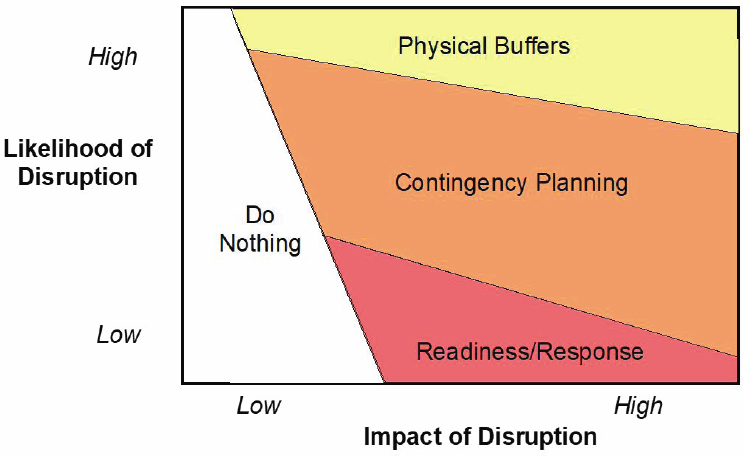

In her final comment, Ergun noted that the consensus committee emphasized the need to map resiliency measures to a supply chain’s risk profile according to two dimensions: the likelihood of disruption and the impact of disruption (Figure 2-3). “What this means is that if we have a product and a supply chain that have a low likelihood of disruption and a low impact of disruption, the resiliency measures required would be different [than] if the likelihood of disruption is medium with a high impact,” said Ergun.

DISCUSSION

Session moderator Veenema opened the discussion by asking the panelists to talk about how better and more clearly defined PPE and PPT standards and guidance can advance supply chain resilience in a way that anticipates trigger events before they occur. Shipp replied that it is important to ensure that standards are written in terms of performance, rather than including material specifications that are unnecessary for the performance of a product. “If you make your standards performance based, then new technologies that offer the same or better protection can be covered by that standard,” said Shipp.

SOURCE: Presented by Özlem Ergun on March 1, 2023, at the PPE/PPT Standardization for a Resilient Public Health Supply Chain Workshop (NASEM, 2022a).

Veenema then asked the panelists to elaborate on ways to reduce barriers to participate in developing standards and how that would contribute to building resilience. Gillerman said that barriers to participation come in different forms for different partners. Small- and medium-sized companies, for example, may not have enough personnel to make the time commitment to participate effectively or contribute to and influence the outcome of standards. For those in academia, participating in the development of international standards does not count toward their institutions’ metrics for tenure and promotion decisions. He noted that the National Science Foundation (NSF) is addressing this last issue by including participation in international standards development as a selection factor for research project acceptance and by allowing grantees to use NSF funds to participate in international standards development.

Gillerman said it is also important to involve laboratory staff in standards development because the evaluation and assessment of product performance will happen in laboratories, and laboratory staff members have a keen understanding of what it means to translate performance objectives into laboratory test methods and measurements. These individuals can provide important input that ensures that standards are clear and that testing in a laboratory in one country will yield the same answer as testing in another country’s laboratories. He noted that the possibility of leveraging common sets of technical requirements to improve supply

chain diversity could have a tremendous impact on the nation’s ability to respond in areas where diversification of the supply chain has value.

Responding to a question about how ASPR is approaching the issue of addressing gaps in standards for the public use of PPE, Evenhaugen said that ASPR has several efforts under way investigating the use of innovative products that meet current standards. For example, a partnership with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), NIOSH, and the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) Division of Research, Innovation, and Ventures (DRIVe) on a mask innovation challenge is providing an opportunity to look at different product types for different users, such as the general public or individuals in occupational settings (BARDA DRIVe, n.d.). He noted that HHS’ February 2022 Public Health Supply Chain and Industrial Base One-Year Report includes uses for public health and points out that there is quite a bit ASPR can do with the Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) and stockpiling PPE (ASPR, 2022b).

On the product innovation side, Evenhaugen said that ASPR is looking at new types of PPE suitable for multiple users. He added that if there are more products available for certain types of users, that would have the effect of relieving pressure from the PPE supply chain and improving product allocation.

Gillerman pointed out that National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory (NPPTL) staff served in a leadership role on the ASTM committee that developed ASTM standard F3502 for barrier face coverings, which he called a source control standard. “It is the kind of mask performance standard that we would expect for people who are going to the grocery stores and may want to use source control during pandemics or other events,” he said. This new standard was developed in only 9 months, and it can serve as an example of how to bridge between a standard suitable for an occupational setting to one suitable for an ordinary citizen’s everyday use. This would have a couple of benefits, said Gillerman. For example, it would enable manufacturers to bring a product to market that is more usable in a public setting and relieve some of the pressure on the PPE supply chain so those products developed for the health care sector and other occupational settings do not get diverted away from the populations that need them the most.

Several members of the public attending the workshop commented that consumers want more than source control. One participant offered the opinion that consumers want a standard such as those associated with KN95 FFRs respirators9 with two-way, 95 percent filtration, while another

___________________

9 For more details on KN95 respirators and how they differ from other forms of respiratory PPE, see Box 1-2.

remarked that the public wants the same standards applied to their PPE that are used for PPE that is approved for use in occupational settings. A third participant commented that a large percentage of the public wants ear loop respirators such as KN95 respirators with a better tradeoff in terms of fit, filtration, fashion, comfort, and ease of use.

A workshop participant asked the panelists if it would be better to have frequent periodic review and updates of standards by standards development organizations so they could accommodate new technologies and needs. Shipp replied that most standards development organizations do not have a set lifetime or time limit for their standards, so if a standard has gone years without revision, it is possible that the organizing body reviewed the standard and deemed it was still good enough. “The general principle is that standards do not last forever,” said Shipp, “and the process of developing standards is a continuous process. Once you publish a standard, you are generally starting work on the next edition the next day.”

There were several questions from workshop participants about how to get more information about the public’s needs and how to get the public more involved in standards setting. Shipp, addressing the question about need, said it involves research into the hazards that the public faces. A recent National Academies report (NASEM, 2022b) addressed this issue in some depth, he said, and identified hazards such as infectious agents, wildfire smoke, and environmental pollution. He noted there is PPE available to the public, such as safety glasses and ear plugs, that is the same as PPE used in occupational settings. The difference, he explained, is that for the occupational setting, someone has done the hazard analysis, decided what the hazard is, and provided the appropriate PPE. “That kind of guidance is what the public needs more than anything else,” said Shipp. In the same vein, a workshop participant noted the need for a take-home guide to promote proper mask and respirator usage.

As for public engagement, Gillerman said that NIST has a long history of engaging partners in its research and framework development, but NIST’s work in standards generally involves manufacturers, academia, and others. Many standards organizations, he said, have programs to enable people who represent user and consumer communities to participate in the standards development process. Effective programs, he noted, help new entrants into the standards development process understand how the process works, what various relevant technical terms mean, and how they can contribute and be influential. Evenhaugen pointed out how important it is to have two-way communication with partners to better understand their needs and so they can better understand the process.

ASPR, he said, uses social media platforms and websites as part of its communication efforts.

A workshop participant noted that identifying legally marketed and approved PPE or PPT with the right fit, the right protection, and the right components, can be challenging, and Veenema asked the panelists if they had thoughts on how to address this challenge for the public and for federal purchasing programs. Gillerman replied that it is important to consider the reasonable levels of use, misuse, and wear and tear relative to an intended use when developing a standard.

Turning to the subject of stockpiling, which several workshop participants commented on, Evenhaugen said that stockpiling is useful for some products to relieve pressure on the supply chain resulting from a sharp increase in demand, but then there is the issue of shelf life, having the right amount of a product when needed, and allocating the product and ensuring it gets distributed throughout the system. He noted there can be sharing agreements, reciprocity, inventory bubbles, and vendor-managed inventory that producers and distributors can supply. As for shelf life, one workshop participant called for developing shelf-life standards, while another pointed out that shelf-life validation is challenging since the method used is required to match the degradation or failure mode of the materials and design of each product. That participant suggested that mandating the identification of potential failures in a system and analyzing their causes and effects as part of a certification process might address this issue.