Assessing the 2020 Census: Final Report (2023)

Chapter: 2 Overview of the 2020 Census

– 2 –

Overview of the 2020 Census

In this chapter, to set the context for the rest of the report, we describe the evolution of the design of the 2020 Census and how its procedures were planned to occur, as well as a synopsis of the operational changes made before and during the census process. We intend this chapter as an orientation to the terms and procedures described in the detailed content chapters of this report, and it is complemented by Appendix C in which we delve into some details of the operational background.

2.1 FOUR KEY INNOVATION AREAS, AND INITIAL VISION FOR THE 2020 CENSUS

The 2020 Census was designed around four “key innovation areas” that were recommended in 2011 by our predecessor Panel to Review the 2010 Census as priority topic areas in which to focus research and development. These topic areas were: (1) field reengineering, “applying modern operations engineering to census field data collection operations;” (2) self-response options, notably including provision for response via the internet; (3) administrative records, using these third-party data “to supplement and improve a wide variety of census operations;” and (4) continuously improved geographic resources, reducing the need for “once-a-decade overhauls” of the geographic databases (National Research Council, 2011:Rec. 1). The U.S. Census Bureau began work in each of these areas, in an alternating series of national content tests (mail/Self-Response only, without a field component), smaller census tests (with field Nonresponse Followup [NRFU] work), and focused testing activities (e.g., a test of partial block canvassing methods, in which listers performed address

list verification activities on just targeted pieces of a block rather than a complete walk of every street). Importantly, the prototype systems developed for these tests—including MOJO for operational monitoring and enumerator route optimization and COMPASS for field data collection, as well as the existing Centurion and emerging Primus platforms for internet response—were developed in-house by Census Bureau staff, under the general heading of the Reorganized Census with Integrated Technology (ROCkIT) Working Group, and their success provided important proofs of concept. In parallel, the Census Bureau also launched a Geographic Support Systems Initiative to better harness information from local-area geographic files.

The four key innovation areas formed the centerpiece of the first version of the Census Bureau’s Operational Plan for the 2020 Census (U.S. Census Bureau, 2015), released in November 2015, and that plan signaled some very marked changes from traditional Census Bureau practice. Indeed, in the geographic resources area, the first operational plan clarified that the 2020 Census was already underway as of early 2015, in the form of In-Office Address Canvassing (IOAC) to identify issues with the Master Address File (MAF) without a field visit; the in-office work would permit In-Field Address Canvassing (IFAC) in 2019 to focus on a much smaller number of cases than the complete block canvassing (field staff walking every street in every block) in 2010. In the self-response area, the first operational plan signaled a commitment not only to internet response but to “Non-ID” response—permitting respondents to answer the census anywhere, from any device, without strictly requiring the respondent to enter an ID number sent by physical mail or left at the respondent’s home. In terms of field reengineering and administrative records, the original operational plan noted many key decisions yet to be made but underscored the desire to reduce the number of enumerator contact attempts during the NRFU operation, including the possibility of using administrative records to enumerate households in some instances when response was not possible but sufficiently high-quality records were available. The plan also foretold a smaller field infrastructure for the 2020 Census relative to 2010, calling for 250 Area Census Offices (a halving of the number of Local Census Offices established for the 2010 Census, and consistent with the halving from 12 to 6 permanent Regional Offices that had already been implemented). A critical starting point for census operations is the delineation of type of enumeration areas (TEAs), governing the approach used for questionnaire delivery and data collection in each census Basic Collection Unit (BCU).1 The first version of the 2020 Census operational plan called for an important simplification: the 2010 Census Update/Leave TEA (in which census enumerators would update the address list

___________________

1 The 2020 Census adopted the new BCU nomenclature, in place of the “collection block” (as distinct from final “tabulation blocks”) label used in previous censuses. Aggregated to the census tract level, the 2020 Census BCUs roughly tracked the existing census block/tract geography developed for tabulating the 2010 Census and updated over the next several years.

and drop off a questionnaire package at the same time, in areas without mail delivery) and Update/Enumerate TEA (in which enumerators would update the address list and conduct the household interview at the same time) were to be consolidated into a single Update Enumerate operation and TEA.

2.2 EMERGENCE OF EXTERNAL PRESSURES

Most of the major external pressures that would shape the 2020 Census took hold in the middle to late years of the decade, but one was present from the outset. The need for continuing resolutions to fund government operations became commonplace, continuing funding at the previous fiscal year’s level because a new appropriations bill was not yet enacted, and doing so for ever-longer periods of time. Table 2.1 illustrates the requested and final enacted appropriations for the 2020 Census; for fiscal years 2012–2021, the length of time in which 2020 Census (and parent U.S. Department of Commerce) funding was governed by continuing resolution ranged from 48–216 days. Though Congress would exceed 2020 Census budget requests late in the decade, the opposite was true earlier in the decade. Hence, “funding uncertainty” became a familiar concern in the middle years of the decade, at the same time that the Census Bureau was working to sustain a program of 2020 Census planning and testing. This funding uncertainty would prompt the Census Bureau to scale back field testing of census operations in 2017 and 2018, and would be the cited reason for several other operational decisions, as we discuss below. Funding-related cutbacks might not be directly traceable to ultimate data quality, but they did limit the extent to which census processes and systems could be tested in advance.

The content, and not just the budgetary process of the census, came under pressure in the late stages of the decade in two important respects—both of which first came to particular prominence in December 2017 and both of which were grounded in the same provision of census law—namely the requirement that the U.S. Congress be notified of the specific questions to be asked in the census two years before the target date (13 U.S.C. § 141(f)). The first affected the race and ethnicity questions for 2020; the second reflected the presidential administration’s objective to collect information on citizenship status, which drew the 2020 Census into advanced litigation.

On the first point, with the March 31, 2018, deadline looming for specifying the 2020 Census questions, the Census Bureau concluded that it needed to make a decision on the structure of the census questions on race and ethnicity (Hispanic origin) by December 31, 2017. The early- and mid-decade census content tests contemplated combining the race and ethnicity questions into a single question, as well as potentially adding a category for Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) to the classification. The Census Bureau’s policy in

Table 2.1 Requested and Enacted Budget for the 2020 Census, by Fiscal Year, and Date of Enactment

| Fiscal Year | 2020 Census (Dollars in Millions) | Date of Enactment | Days Since Start of Fiscal Year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Budget Request | Enacted Budget | |||

| FY 2012 | 67 | 67 | 11/18/11 | 48 |

| FY 2013 | 131 | 94 | 3/26/13 | 176 |

| FY 2014 | 245 | 233 | 1/17/14 | 108 |

| FY 2015 | 443 | 345 | 12/16/14 | 76 |

| FY 2016 | 663 | 625 | 12/18/15 | 88 |

| FY 2017 | 778 | 767 | 5/5/17 | 216 |

| FY 2018 | 957 | 2,095 | 3/23/18 | 173 |

| FY 2019 | 3,015 | 3,015 | 2/15/19 | 137 |

| FY 2020 | 5,297 | 6,696 | 12/20/19 | 80 |

| FY 2021 | 812 | 238* | 12/27/20 | 87 |

* FY 2021 was fully funded through utilization of prior year balances rather than new appropriations.

SOURCE: Fontenot and Taylor (2021), adding in calculation of days elapsed between October 1 start of fiscal year and date of enactment of appropriations act.

the 2000 and 2010 Censuses was to conform to the U.S. Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) Statistical Policy Directive No. 15 on the collection of federal data on race and ethnicity, last revised in 1997. Because OMB did not act on proposals dating to the mid-2010s to revise the directive, the Census Bureau decided in December 2017 (and announced on January 26, 2018) that it would retain the two-question format for race and ethnicity in the 2020 Census and also exclude a new MENA category (Fontenot, 2018c). As discussed in detail in Chapter 10, this nonaction by OMB and subsequent design decision by the Census Bureau would prove consequential, particularly because the Census Bureau continued with other changes to the postcollection processing and coding of race/ethnicity data.

The second proposed content change for 2020 was more controversial, and ultimately was not implemented, though the controversy reverberated through a great deal of the media coverage of the upcoming census. In December 2017, a letter from U.S. Department of Justice officials requesting the addition of a question to the 2020 Census was circulated, and the request was said (in a January 10, 2018, press release2) to be under evaluation. On March 26, 2018, Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross issued a decision memorandum

___________________

2 Press Release Number CB18-RTQ.01; https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2018/citizenship-question.html.

directing both that a citizenship question be added to the form and that the Census Bureau develop its capacity to derive citizenship information from administrative records sources. The decision was immediately challenged as an unprecedented and unjustified late addition to the census, and it touched off a first wave of litigation around the 2020 Census (see Box 2.1). In January 2019, the addition of the citizenship question was ruled a violation of the Administrative Procedures Act by a federal district court in the Southern District of New York, and the court enjoined the Census Bureau from asking the question. Under pressure for a decision on when to initiate printing of 2020 Census forms, the case was expedited to the U.S. Supreme Court, which upheld the injunction in June 2019 (Department of Commerce v. New York, 2019). In response, the administration issued Executive Order No. 13880 (2019), directing the work on deriving citizenship information from administrative records to continue. The entire episode generated fears that damage might have already been done and resulting public mistrust might suppress 2020 Census response by immigrants and vulnerable populations.

2.3 EVOLUTION OF THE 2020 CENSUS DESIGN

2.3.1 Progression of 2020 Census Operational Plans

Development and testing continued during the mid-decade, and Versions 2.0, 3.0, and 4.0 of the 2020 Census Operational Plan were issued in 2016, 2017, and 2018, respectively, on the heels of 2015’s Version 1.1. Critically, each new version retained the broad-strokes design and four targeted areas of innovation and added new decisions on specific design parameters. But each new version also made some consequential alterations to parts of the design, mainly in the vein of tempering some of the major innovations.

By Version 2.0 of the operational plan (U.S. Census Bureau, 2016a), in line with the broader Census Enterprise Data Collection and Processing (CEDCaP) initiative, the Census Bureau decided to largely supplant the in-house software systems that had supported the early-decade census tests with outsourcing and recoding in a commercial programming environment. Specifically, citing perceived benefits in systems security and scalability, the Census Bureau contracted with Pegasystems Inc. in May 2016 to develop a commercial off-the-shelf software base for many of its technical systems (U.S. Census Bureau, 2016b). In the process, the Census Bureau necessarily incurred loss of time and effort in recoding extant systems.

Version 3.0 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017) formalized a particularly acute operational casualty of the prevailing funding uncertainty surrounding the 2020 Census. As originally specified, the IOAC operation for updating the Census Bureau’s MAF had two major components. Blocks would first go through Interactive Review, a quick operation in which the total number of living

quarters in the MAF is reconciled with the count of units visible in available aerial imagery. Blocks with discrepant counts would then go into Active Block Review, in which census workers at the National Processing Center in Jeffersonville, Indiana, could use multiple imagery and data sources (e.g., local area plat maps) to actively add, delete, or alter MAF entries. Funding uncertainty prompted the Census Bureau to halt Active Block Resolution in 2017; IOAC would continue with the Interactive Review segment, at the expense of adding to the eventual IFAC workload in 2019.

With Version 3.0 of the operational plan, the Census Bureau would also take a step back from a primary distinction between Self-Response areas (with initial contact by mail) and Update Enumerate areas (with address list updating and in-person enumeration done on the same personal visit by an enumerator). In the plan, the Census Bureau reinstated an Update Leave operation and TEA, in which enumerators update the address list and leave a questionnaire package (with, for 2020, instructions to return via the internet) at households but do not conduct interviews. Most of the previously delineated Update Enumerate territory would instead be covered in Update Leave; the Census Bureau would also specify that the smaller Update Enumerate operation revert to paper questionnaires rather than electronic collection on a smartphone (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017). As discussed in Section 2.3.2, a final revision to the planned TEA structures would yield the final enumeration strategies described in Box 2.2 and Figure 2.1.

By the end of 2018, other elements of the 2020 Census design had fallen into place—among them, the February 2018 finalization of residence criteria for the 2020 Census,3 making a change in the way “temporarily deployed” military personnel (relative to “stationed” personnel) would be counted but repeating past decades’ handling of groups such as adult correctional facility inmates and college students. The final 2020 Census design (preceding the count itself) was embodied in the December 2018 release of Version 4.0 of the operational plan (U.S. Census Bureau, 2018), which made two especially profound changes to proposed operations. The first tempered the pure vision of the reengineered field operations innovation area of the 2020 Census design, restructuring the resource-intensive NRFU operation to include three distinct phases. Phase 1 would include the full optimization of enumerator workload assignments as envisioned in the previous versions of the plan, but Phase 2 would cull the temporary enumerator workforce to include only those who had been most productive in obtaining interviews in Phase 1, distributing the remaining cases among those high-yield enumerators. Phase 3, dubbed Closeout, would use the same reduced set of enumerators but focus on collecting at least some information (even if population count only) for remaining households. The

___________________

3 The “Final 2020 Census Residence Criteria and Residence Situations” were printed in the Federal Register on February 8, 2018 (83 FR 5525).

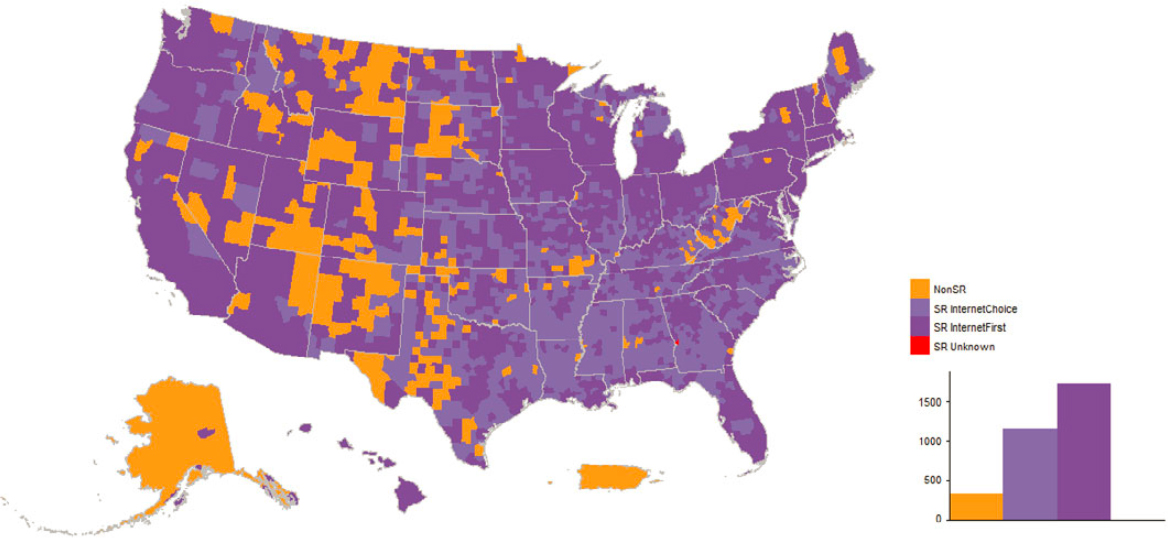

NOTE: SR, Self-Response, corresponds to type of enumeration area (TEA) 1. NonSR, Non-Self-Response, consolidates TEAs 2 (Update Enumerate), 4 (Remote Alaska), and 6 (Update Leave).

SOURCE: Modal TEA by tract (as embedded in Basic Collection Unit code) derived from MAF-unit level TEA designations in MAF Development Dataset; matched to publicly available dataset of mailing strategies (https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/newsroom/releases/2019/2020-mail-strategies-bytract.xlsx); aggregated to county. See Disclosure Review Statement; CBDRB-FY23-0197.

second change signaled by Version 4.0 was subtly worded but was arguably the most consequential of all the precensus design changes: the new plan declared that the 2020 Census would implement a new strategy for disclosure avoidance and protecting the confidentiality of respondent information, based on the concept of differential privacy which the plan described simply as the addition of statistical noise to published tables.

2.3.2 Immediate Precensus Challenges and Operational Revisions

With Census Day 2020 fast approaching, the 2020 Census weathered additional preliminary challenges. Among these challenges, the Census Bureau raced to finalize work on the information technology support systems for the 2020 Census and to test core functionality in the 2018 End-to-End Census Test—a test that had already been heavily scaled back (from three planned sites to the single site of Providence, Rhode Island) due to funding uncertainty.

One late change, in 2019, altered a planned use of third-party, administrative records data in the 2020 Census. Prior to 2019, the Census Bureau’s planned TEAs included a separate Military category, in which administrative data would play a much stronger role; “the Census Bureau had adopted the recommendation from the Defense Manpower Data Center that they could provide administrative records for the Census Bureau to use to enumerate military personnel” (Fontenot, 2021g). However, “after review of administrative records provided by the military,”4 the Census Bureau concluded that it could not rely on the records data. Accordingly, the Military TEA covering areas with military installations was dissolved, with the previous TEA 5 being divided into TEAs 1 and 6 (Self-Response or Update Leave; Fontenot, 2022c). Similarly, military group quarters (GQs)—“barracks/dorms, treatment facilities, and military correctional barracks”—were designated for enumeration “using the methodology defined for the 2020 Group Quarters Enumeration” (Fontenot, 2021g).

In summer 2019, as census data users and stakeholders started to become aware of the sweep of the Census Bureau’s new Disclosure Avoidance System, the Census Bureau committed to producing 2010 Demonstration Data Products—versions of previously published 2010 Census tabulations that subjected the 2010 data to the new differential privacy-based system slated for use in 2020. The first generation of these products was made available for rapid analysis and discussion in a December 2019 National Academies workshop (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2020); the anomalies and unusual features of the demonstration data sparked debate over the utility of the privacy-protected data—a debate that continues into 2023 and beyond.

___________________

4 This is described by the Census Bureau as an “enumeration test file” by Fontenot (2022c).

In the immediate build-up to the 2020 Census, all three of the planned major response modes to the census—internet, paper, and telephone—experienced some form of challenge:

- As described in Box 6.2, late concerns over the Pega-based internet data-collection instrument’s ability to handle a massive volume of concurrent users prompted the Census Bureau to promote its in-house-developed Primus system from backup system to primary system—a decision announced on February 7, 2020. This decision was not without risk given that 2020 Census Internet Self-Response was scheduled to go live on March 12.

- In November 2017, the U.S. Government Publishing Office announced the award of the 2020 Census Printing and Mailing Contract to Cenveo, Inc.; on February 2, 2018, Cenveo filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, resulting in another several-months battle to sever the contract early. It took several more months to secure a new vendor, with R.R. Donnelley and Sons Company being awarded the new contract in late January 2019.

- Some ambitious, originally planned telephone-based operations of the 2020 Census—under the umbrella of the Census Questionnaire Assistance (CQA) operation—were considerably scaled back in 2018 and 2019. Plans for conducting some NRFU Reinterview (reinterviews for quality-assurance purposes) cases by telephone were scrapped after the 2018 End-to-End Census Test yielded fewer case completions than expected. Likewise, the plans for CQA to include a Webchat communication channel as well as a Questionnaire Status option through which CQA callers could learn “if their questionnaire had been formally received by the Census Bureau” were stricken in 2018 on cost-benefit and feasibility grounds (Fontenot, 2021j).5

The February 2019 omnibus appropriations act that ultimately funded most federal government operations for fiscal year 2019 included explanatory statement text that directed the Census Bureau to “devote funding to expand targeted communications activities as well as to open local questionnaire assistance centers in hard-to-count communities” for the 2020 Census.6 In response, the Census Bureau stood up the Mobile Questionnaire Assistance (MQA) suboperation within the Internet Self-Response operation, with the intent of deploying staff equipped with mobile devices to “key locations with prominent visibility in areas with low self-response rates” (Fontenot, 2021e). In a sense, this initiative revived the partially-staffed Questionnaire Assistance Centers of the 2010 Census but without anchor to predefined physical locations;

___________________

5 In lieu of the Questionnaire Status option, CQA phone callers were advised “to disregard mailed materials if they had already responded” to the census by other means (Fontenot, 2021j).

6 See H.Rept. 116-9, p. 611.

for example, a MQA site could open at a local festival or a library for a period of time, but driven by either projected low self-response rates or actual real-time response rates in an area rather than a fixed commitment. MQA staff were to be equipped with “Census Bureau-issued mobile devices” to complete interviews via the Internet Self-Response channel or to provide questionnaire or language guide assistance (Fontenot, 2021e).

2.4 THE 2020 CENSUS, PLANNED AND UNPLANNED

2.4.1 The COVID-19 Pandemic and Resulting Schedule Changes

Then, of course, the great disruptive force arrived just as 2020 Census operations were ramping up. The start of the Self-Response phase of the 2020 Census on March 12, 2020, was overshadowed by the declaration of a national emergency due to the COVID-19 pandemic on March 13. The range of state and local stay-at-home orders following the emergency declaration caused the Census Bureau to comprehensively halt all field activities on March 18—initially for two weeks, and subsequently extended—and scramble to adapt to the unprecedented change in circumstances.

On April 13, as the Census Bureau worked to gradually resume operations, Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross and Census Bureau Director Steven Dillingham issued a joint statement that, “in order to ensure the completeness and accuracy of the 2020 Census, the Census Bureau is seeking statutory relief from Congress of 120 additional calendar days” to deliver apportionment and redistricting data.7 Under this proposed schedule, field offices would be “reactivated” on June 1, 2020, and census data collection would extend to October 31; apportionment totals would be delivered by April 30, 2021, and redistricting data delivered by July 31, 2021. However, in the weeks that followed, Congress did not pass any bill providing the requested statutory relief.

2.4.2 Presidential Memorandum on Undocumented Immigrant Counts, Schedule “Replan,” and End of Data Collection

Before delving into the details of some of the numerous operational changes made in the 2020 Census due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we continue with a further outline of the overall chronology of events.

In this mix, a Presidential Memorandum for the Secretary of Commerce (2020) indicated the presidential administration’s policy to subtract unlawful immigrants from the population base for congressional apportionment, directing that the Secretary of Commerce (via the Census Bureau) provide those state--

___________________

7 See Census Bureau Press Release No. CB20-RTQ.16, https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2020/statement-covid-19-2020.html.

level estimates at the same time as the 2020 Census apportionment counts—the statutory deadline for which had not been changed.

Under normal circumstances, the progress of a census might be marked by operational briefings and congressional oversight hearings; in 2020, it would come to be documented in court filings, discovery documents, and affidavits. Accordingly, the next steps in the chronology of events are most succinctly described in a court declaration by Census Bureau associate director Albert Fontenot, Jr.:8

Once it became apparent that Congress was not likely to grant the requested statutory relief, in late July the career professional staff of the Census Bureau began to replan the Census operations to enable Census to deliver the apportionment counts by the Statutory deadline of December 31, 2020. On July 29, the Deputy Director informed us that the Secretary had directed us, in light of the absence of an extension to the statutory deadline, to present a plan at our next weekly meeting on Monday, August 3, 2020 to accelerate the remaining operations in order to meet the statutory apportionment deadline. I gathered all the senior career Census Bureau managers responsible for the 2020 Census at 8:00 a.m. on Thursday, July 30 and instructed them to begin to formalize a plan to meet the statutory deadline. . . . We divided into various teams to brainstorm how we might assemble the elements of this plan, and held a series of meetings from Thursday to Sunday. We developed a proposed replan that I presented to the Secretary on Monday August 3.

Secretary Ross approved and announced this “Replan” schedule that same day, under which September 30—one month earlier than the target four-month extension date previously requested by the Census Bureau—became the new target end date for data collection. This schedule prompted a new wave of litigation in several jurisdictions, arguing that the census was being unduly rushed (see Box 2.1). The case related to the speed of 2020 Census operations that progressed the furthest was National Urban League v. Ross (2020). Ultimately, the target end date of 2020 operations would fluctuate several times based on new plans and court injunctions, until an unsigned order of the U.S. Supreme Court related to the National Urban League case permitted data collection to end on October 15.

2.4.3 Changes in 2020 Census Operations Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic

The amount of disruption in census work caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated field delays are difficult to overstate, and it is testament to the strength and efficiencies of the underlying census design

___________________

8 Declaration of Albert E. Fontenot, Jr., in National Urban League v. Ross (2020), Document 81-1, September 4, 2020.

that the census could function at all. Specific changes occasioned due to the pandemic, which could ultimately affect census data quality, are peppered among publicly released operational memoranda that provided updates to the Detailed Operational Plans for individual census operations. Particularly salient examples include the following:

- Early NRFU and some administrative records enumeration for off-campus college and university students were canceled. Building off improvements realized in the 2010 Census, the Census Bureau planned to conduct Early NRFU (beginning in April rather than May) in areas in the vicinity of colleges and universities, to attempt to count students living in off-campus housing (i.e., their usual residence for census purposes). However, the pandemic-induced shutdown of operations—and the general dispersal of the college student population—led to Early NRFU being descoped (Fontenot, 2021d). In late summer of 2020, the Census Bureau mounted a contact effort to colleges and universities specifically to try to account for students living off campus who might not have been otherwise counted. “This unplanned operation resulted in the creation of additional AdRec [administrative records-based] enumeration data that was generated outside of the planned AdRec process and incorporated into the final processing” (Fontenot, 2022b).

- The original plans for enumerating specific places and facilities, which had been brokered in the Advance Visit operations for GQs and transitory locations, were scuttled by the field shutdown and scheduling delays. In the case of transitory locations, a second round of Advance Visit was scheduled but with some differences; notably, local Area Census Offices were made responsible for determining whether carnivals, circuses, or fairs would be operational during Enumeration at Transitory Locations fieldwork in September 2020, rather than contacts being brokered by calls from the Census Bureau National Processing Center’s call center as done in the initial Advance Visit (Fontenot, 2021b).

- The training for NRFU enumerators was restructured and rescaled to minimize in-person contact. Plans had already called for use of online training modules between the initial orientation day (meant to be in-person/classroom) and a capstone training day (meant to include in-person trial interviewing), and this continued. But both endpoints in the training program were restructured. “The orientation classroom training day was reduced from a full day to a 2-hour appointment. The remainder of the orientation day and the capstone training day were conducted through self-study reading, a podcast, and conference calls. . . . Interactive scenarios for learning how to handle difficult and unusual situations that are a major component of the capstone did not happen in-class, [but instead] as part of the telephone capstone day” (Fontenot, 2021d).

- COVID-19 pandemic operations had major implications for the Update Leave and Update Enumerate types of enumeration prevalent in rural areas without mail delivery, over and above the basic difficulties of access (e.g., to American Indian lands) created by pandemic-related health orders. For instance, the address list “update” part of Update Leave was converted to a no-contact, limited practice. As planned, Update Leave enumerators were expected to make a contact attempt at housing units to ascertain address/housing unit information, in addition to dropping off a questionnaire package. As a result of the pandemic, the contact attempt was eliminated and “any updates to an address were conducted by observation only,” so enumerators could identify hidden or unseen housing units in plain sight (Fontenot, 2021f). This is consequential because both Update Leave and Update Enumerate areas were excluded from IFAC eligibility, making the contact attempt a key MAF-record update activity. In the even more rural Update Enumerate and Remote Alaska operations, 2020 plans eschewed a reinterview-based quality-assurance operation in favor what was perceived as a simpler fix—deploying enumerators to work in pairs, partially as a check on each other. However, due to the pandemic, it became optional rather than mandatory for Update Enumerate staff to work in pairs—while also requiring at-least-six-feet social distancing during interviews (Fontenot, 2021i).9

- Pandemic-era procedures called for added functionality in the 2020 Census’ telephone-based operations. As an “unplanned contingency,” the Census Bureau permitted that “enumerators in areas with high COVID rates, impacted by natural disasters, or with low completion rates were allowed to use telephone follow-up” to make some of their contacts with NRFU cases by telephone, using phone numbers extracted from the Census Bureau’s Contact Frame. These phone contacts would count towards determining eligibility for proxy or administrative records enumeration availability (Fontenot, 2021d). Similarly, the functionality of the CQA operation was expanded to give callers to CQA phone lines (in all languages) the option to request a callback if staff could not immediately answer; CQA representatives could return calls and either provide assistance or complete an interview, “using government furnished

___________________

9 In changes described as unrelated to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Enumeration at Transitory Locations (ETL) operation was twice reworked to replace a field-based ETL Reinterview for quality control purposes. Original plans called for ETL Reinterview to be done by phone, but projected response rates were deemed too low. Instead, 2020 ETL interviewing was done (using paper questionnaires) by small groups of enumerators, just as was the original plan for Update Enumerate and Remote Alaska—the theory being that “the use of multiple staff for enumeration largely prevents the opportunity for the data falsification that reinterview is intended to identify” (Fontenot, 2021b).

- equipment at home” if necessary. CQA support was also added to field calls from administrators of GQs to help them complete questionnaires, given the delay-induced need to broker new agreements for acquiring GQ information (Fontenot, 2021j). Curiously, though, phone contact was eliminated as an option in the Office-Based Address Verification and manual/clerical processing of Non-ID census returns, as part of reconfiguring operations and ensuring that resources were available for manual matching and geocoding when needed (Fontenot, 2021c).

- A subtle innovation was initially planned for the 2020 Census, in which NRFU cases in large, multiunit structures would be grouped in assignments. In these “Manager Visit” cases, enumerators would contact property and building managers first, to assess general housing unit status (and hence potentially reduce workload). However, while trying to stand up NRFU operations amidst the work-delay difficulties, it was found that “multiunit cases were not grouped correctly” in the technical systems and that, in particular, NRFU “cases that had administrative records [available] were placed in a separate workload” and thus excluded from the multiunit groupings. Hence, Manager Visits were descoped and the individual housing units within the structures released into the general NRFU workload (Fontenot, 2021d).

- The MQA program established in response to Congressional interest was premised on deployment at large public events—which were now ruled out by pandemic-era restrictions on gathering. Hence, MQA was revised in scope to focus on “sites in places where people visit when leaving home” as opposed to larger public gatherings (Fontenot, 2021e).

- Under the broader Count Review operation, which garners inputs from state demographer participants in the Federal-State Cooperative for Population Estimates (FSCPE) program, the 2020 Census was planned to involve a Post-Enumeration Group Quarters Review session in the very late stages of Group Quarters Enumeration in the field. This session, also dubbed Review Event 2, was to include both remote-access and on-site components, permitting FSCPE participants to review initial results for GQs in their states and suggest last-minute additions. Originally canceled and ultimately rescheduled as a remote-only event on September 23–28, 2020, Review Event 2 was also greatly reduced in scale; “the opportunity to add new GQs” and access to control systems and geographic databases were not provided “because once the initial review was canceled, access to the census network was removed and couldn’t be reinstated in time for the modified review.” Moreover, review access (in Excel spreadsheet extracts) was limited solely to the subset of “noneumerated GQs that had an enumeration disposition reason of ‘Cannot Locate in Block’” (Fontenot, 2021a). Had the GQ review event been conducted as planned, it is quite possible that some major problems that affected measurement

- of the GQ population might have been detected in time for corrective action.

- Internal Census Bureau subject-matter expert review of incoming 2020 Census data was only slated to begin with Decennial Response File 2, after some amount of processing; however, the operational fieldwork delays and resulting compressed timeline prompted the Census Bureau to start the internal review with the basic-compilation Decennial Response File 1 (Fontenot, 2021a). The COVID-19 pandemic was also said to be the cause of the cancellation of one planned study—Evaluating the Effect of the Decennial Census on Self Response to the American Community Survey (ACS)—in the 2020 Census program of evaluations and experiments (Fontenot, 2021k).

- On August 12, 2020, use of Best Time to Contact probabilities—estimated from administrative records and input into the optimizer for determining NRFU enumerator assignments—was discontinued because “using that parameter slowed the assignment of cases to field staff” (Fontenot, 2021d), and time was at a premium due to the compressed schedule.

2.4.4 2020 Census Data Products

After resolving the question of when 2020 Census field and Self-Response operations would end, the Census Bureau turned its attention to the processing of results and to conducting the even-more-delayed Post-Enumeration Survey—both of which proved more problematic and time consuming than expected. In particular, the processing encountered numerous anomalies—not unlike snags encountered by previous censuses but difficult to handle in a high-pressure environment. Meanwhile, during fall 2020, pressure to produce the estimated counts of undocumented immigrants called for by the Presidential Memorandum of July 2020 continued to bubble, and would do so until a January 2021 U.S. Department of Commerce Office of Inspector General memorandum shone light on those pressures.10 On December 30, the Census Bureau formally acknowledged that it would be unable to satisfactorily produce apportionment totals by the year-end deadline but that it would work to do so as soon as possible. The Presidential Memorandum of July 2020 and the predecessor Executive Order No. 13880 were both formally rescinded by executive order on January 20, 2021, and the Census Bureau ultimately released 2020 Census apportionment counts and redistricting data on April 26 and August 12, 2021, respectively.

___________________

10 See the January 12, 2021, memorandum at https://www.oig.doc.gov/OIGPublications/OIG-21-019-M.pdf. The memorandum acknowledged whistleblower reports from within the Census Bureau stating that the undocumented immigrant estimates had been cast as “a number one priority,” to be complete on January 15, 2021, ahead of the change in presidential administrations.

2.5 CONCLUSION

This brief synopsis of just some of the challenges involved in conducting the 2020 Census is important for understanding the analyses of specific operations and concepts that we pursue in the rest of this report. But it is a powerful story in its own right, one that deserves to be told in even fuller detail. While it is true that the details can be gleaned from examination of dozens of individual memoranda, we think it important to the Census Bureau’s own institutional memory that these details be documented and preserved, to facilitate the derivation of lessons learned for the 2030 Census and beyond. Accordingly, we recommend:

Recommendation 2.1: In addition to completing its own program of evaluation and assessment reports, the U.S. Census Bureau should complete and publish a comprehensive procedural history of the 2020 Census.