Preventing and Addressing Retaliation Resulting from Sexual Harassment in Academia (2023)

Chapter: How Does the Law Address Retaliation?

How Does the Law Address Retaliation?

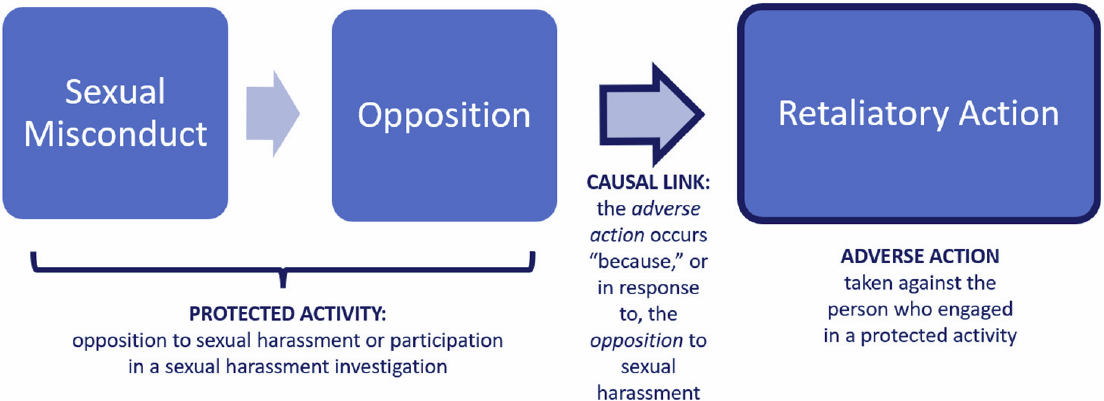

Retaliation, including retaliatory conduct that results because an individual complains of or participates in the investigation of sex-based or sexual misconduct, harassment, or discrimination, is prohibited by numerous federal and state laws and regulations. While it is beyond the scope of this paper to describe all such laws and their many nuances and distinctions, the general legal framework for understanding retaliation typically involves three components: (1) an adverse action taken against a person (2) because (or “as a direct consequence of”) (3) that person engaged in a protected activity8 by opposing sexual harassment or participating in an investigation of sexual harassment. In other words, for the purposes of this paper, retaliation occurs when an individual opposes sexual harassment by a harasser (i.e., reporting, objecting) or participates in an investigation of sexual harassment, and the harasser (or another person who was aware of the protected activity) responds by taking an adverse action against the individual (i.e., termination, failing grade) (see Figure 1).

The legal analysis of retaliation requires taking a step back in the timeline of events to consider whether there was (1) opposition to sexual misconduct (or participation in an investigation of sexual misconduct); (2) an adverse action that followed that opposition or participation; and (3) a causal link between the adverse action and that opposition or participation. In the sections below we show how this framework can be challenged in a claim of retaliation.

__________________

8 Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) laws aim to protect job applicants and employees from punishment as a consequence of asserting their rights to “be free from employment discrimination including harassment.” The assertion of such rights is referred to as engaging in “protected activities” and includes refusing to follow orders that could result in discrimination, intervening to protect others from sexual harassment, and reporting an incident of sexual harassment (see U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission web page at https://www.eeoc.gov/retaliation).

The three components of retaliation are further discussed by considering the following three questions commonly asked in legal proceedings:9,10

- Did the person reporting retaliation engage in protected activity?

The most obvious and easily recognized form of protected activity is the filing of a formal complaint regarding sex-based or sexual misconduct, harassment, or discrimination with one’s employer/institution, an external agency, or a court. However, protected activity can also include informally raising such complaints to one’s employer/institution (including verbally rather than in writing), threatening to file a complaint or bring a lawsuit, refusing to engage in activities reasonably believed to be discriminatory or harassing, resisting sexual advances, participating in an investigation of sexual misconduct, and other forms of opposition to conduct that is prohibited by anti-discrimination and anti-harassment laws. Complaints of sexual harassment expressed (formally or informally) by third-party witnesses/observers also constitute protected activity, as does a bystander’s intervention in ongoing sexual harassment experienced by another. - Did the person reporting retaliation experience an adverse action after engaging in protected activity?

While the various federal and state laws may differ to some extent, and case law is ever evolving, an adverse action will generally involve a significant negative consequence for the reporter and would not include an action that has minimal negative impact.11 - Was the adverse action taken because of the protected activity of the person reporting retaliation?

The causal link is often the key piece in determining whether retaliation occurred. Frequently, the protected activity and adverse action are not disputed, but the accused denies a connection between the two. While many factors can be weighed to assess a causal link, key considerations often include whether the accused had knowledge of the reporter’s protected activity at the time the adverse action was taken;12 the temporal proximity between the protected activity and the adverse action; whether the person accused of retaliation had taken or started to take similar adverse actions against the reporter prior to the protected activity; and whether the person accused of retaliation had taken similar adverse actions against individuals who had not engaged in the protected activity. Assuming the person accused of retaliation provides a nonretaliatory reason for the adverse action, the veracity of that reason will be scrutinized based on the relevant circumstances.

__________________

9 There is an extensive body of case law interpreting retaliation under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, a federal statute that protects employees from discrimination and harassment on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, and sex (42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq., 1964). Courts interpreting Title IX of the Education Amendments Act and various state laws prohibiting retaliation have often referred to and/or relied upon Title VII case law.

10 The legal framework holds institutions—not individuals—accountable for retaliation. To comply, colleges and universities generally have translated these legal prohibitions that hold their institution accountable into institutional policies that apply to the institution’s individual community members.

11 For example, Title VII case law requires a “materially adverse action,” a phrase that has been interpreted broadly and is not limited solely to discriminatory actions that affect the terms and conditions of employment, as in, for example, Burlington N. & Santa Fe Railway Co. v. White, 126 S. Ct. 2405, 2414-15, 2006, p. 16. While many laws do not provide examples of adverse actions, the 2020 amendments to Title IX’s regulations describe a specific type of prohibited retaliatory conduct in which—for the purpose of interfering with a right or privilege secured by Title IX—an individual is charged with misconduct arising out of the same facts or circumstances as a report or complaint of sexual harassment or sex discrimination, but which does not involve sexual harassment or sex discrimination.

12 Some courts have considered this its own required factor, rather than a consideration when assessing a causal link.

While it is common to envision the accused individual retaliating against the person who accused them, this is not always the case. Any person who takes an adverse action against an individual because that individual engaged in protected activity may be found to have engaged in retaliation. For example, consider a dean who resents a student for publicly accusing their faculty member of sexual harassment—if the dean limits the student’s academic opportunities because of the student’s protected activity, the dean has engaged in retaliation even if the accused faculty member is completely uninvolved.

How Do Legal Protections and Institutional Policies Fall Short in Addressing Retaliation in Academia?

Despite the federal and state protections that make retaliation unlawful, it can be hard to address for a variety of reasons. The frequent lack of conclusive evidence, or “smoking guns,” and the various forms of retaliation make it hard to prove that an adverse action was triggered by someone opposing sexual harassment, reporting sexual harassment, or participating in an investigation of sexual harassment (Wendt and Slonaker, 2002). For example, the 2002 study by Wendt and Slonaker showed that 50 percent of 129 retaliation claims filed with a state agency resulted in a decision of “no probable cause,” meaning there was not enough evidence to prove the claims. Only 4 percent of the claims led to a finding of “probable cause,” meaning there was sufficient evidence of retaliation.13

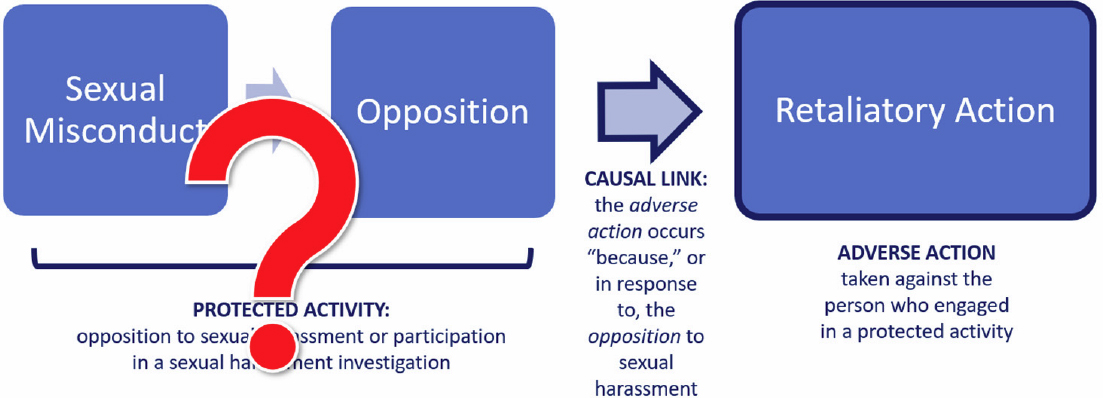

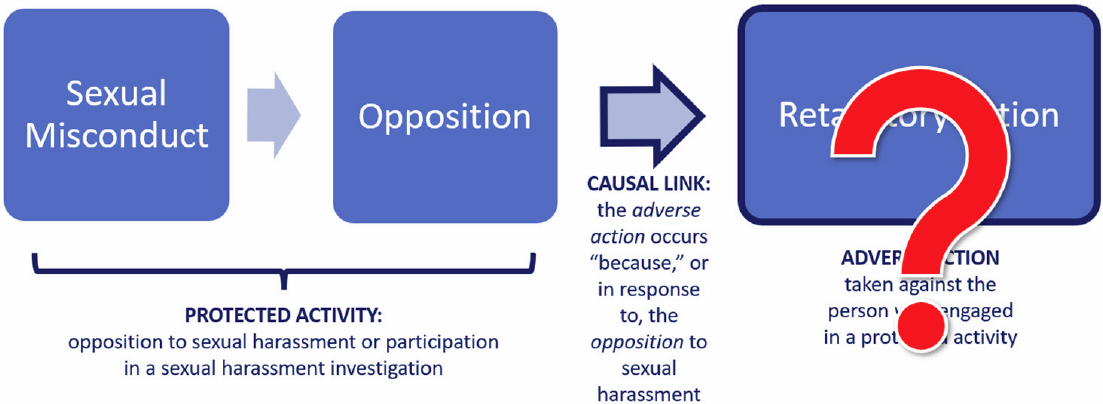

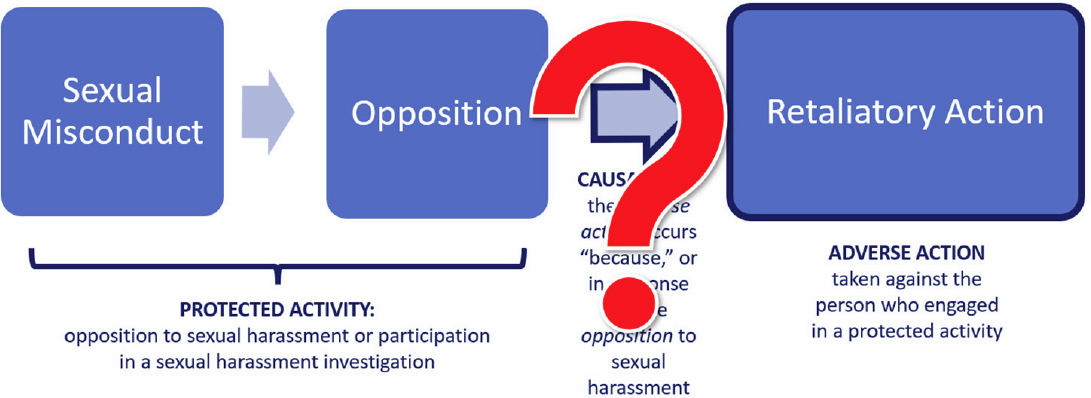

Below are three examples of specific challenges in supporting a claim of retaliation. Each example includes a discussion of the challenge and illustrates that challenge’s place in the sequence of events that make up retaliation (see Figures 2, 3, and 4).

- Challenge #1: When there is insufficient evidence to show that the person reporting retaliation engaged in protected activity (see Figure 2). Retaliation prohibitions were created to encourage individuals to report concerns of sexual harassment without fear of retribution, thereby enabling institutions to learn of and address such unlawful behavior. In order to garner this protection from retaliation, however, courts have held that the reporting individual must have a “reasonable belief” that the complained-of conduct is, in fact, unlawful. While the individual does not need to prove that the conduct they have opposed is actually unlawful, the required reasonable belief of unlawfulness can be problematic because legal definitions of sexual harassment vary, may differ substantially from common understanding, and case law is always evolving. For example, under Title VII, a complainant must show that sexual harassment was sufficiently “severe or pervasive” in order to make it actionable (Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson, 477 U.S. 57, 67 (1986)), but under Title IX, the 2020 regulations require evidence that the harassment is sufficiently “severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive” in order to be actionable (34 C.F.R. § 106.30(a) (2)). So, if an individual reports a colleague who gave them an uncomfortable “compliment” about their physical appearance, such conduct (on its own) might not satisfy the requirement because it would not reasonably meet the high legal standard for sexual harassment to be “severe or pervasive,” let alone “severe and pervasive and objectively offensive.” This means that if the offending colleague began treating the individual poorly following a stern warning from the human resources department, such

__________________

13 For the remaining claims, 27 percent resulted in a settlement, 17 percent were withdrawn by the reporter prior to any outcome (likely to proceed to litigation), and 2 percent were closed due to lack of jurisdiction (Wendt and Slonaker, 2002).

conduct likely would not be considered retaliation under the law, even if it was a direct result of the individual’s reporting of inappropriate sex-based conduct. Moreover, even though legal standards and institutional policies often set a high bar for sexual harassment, institutions often train and encourage students and employees to report any concerning sexual or sex-based conduct, with the hope of intervening to prevent recurrence of behavior that, while inappropriate, may not meet the legal definition of harassment. This effort, however well-intentioned, encourages individuals to report behavior that is unlikely to be sanctioned, which in turn leaves the reporting individual unprotected from retaliation. For instance, if a bystander observes the uncomfortable compliment described above and implements intervention tactics trained and encouraged by the institution, that bystander could experience retaliation, yet may not have legal protection from retaliatory actions.

- Challenge #2: When the adverse action is subject to debate (see Figure 3). As an added complication, in some situations, even the adverse action could be disputed. For instance, a supervisor who retaliates by denying his employee’s promotion might claim that the employee never experienced an adverse action because the employee remained in their same position with the same pay, benefits, and responsibilities. If the anticipated promotion was solely a verbal understanding, successfully arguing that the employee experienced any concrete negative consequence could be particularly difficult. Similarly, if an employee or trainee is subject to an annual contract, it could be much harder for them to prove that the decision not to renew (which was never guaranteed in the first place) was retaliatory rather than for a business reason corresponding to the agreed-upon contract. Finally, given the highly specialized work and academic environments often found in higher education institutions, it may be particularly difficult to explain to a court or agency why a seemingly minor decision to non-academics (such as a move from first author to second author of a journal article) constitutes an adverse action, as well as to refute misleading counterarguments raised to oppose the retaliation claim.

- Challenge #3: When there is insufficient evidence to prove the causal link between an adverse action and a protected activity (see Figure 4). The fact that a person engages in a protected activity and subsequently experiences an adverse action is not enough to show that retaliation occurred. Rather, the reporter must establish that the adverse action happened because of the protected activity, rather than for some other, legitimate reason. Not surprisingly, however, a person (or employer) who engages in a retaliatory act typically will not advertise, let alone document, their retaliatory motive. This means that the person claiming retaliation rarely will have direct evidence, such as a supervisor’s e-mail stating, “I heard you complained about me to the Title IX Office, so I’ll be rescinding your promotion.” Instead, as mentioned in Challenge #2, above, the retaliating individual may provide a nonretaliatory explanation for the adverse action that sounds fully plausible in the circumstances: “Unfortunately, due to unexpected budget demands, your promotion is going to be put on hold for now.” In this situation, even if it is undisputed that an individual engaged in protected activity (complaining to the Title IX office about the supervisor), experienced an adverse action (withdrawal of a promised promotion), and identified a possible causal link between the two (the supervisor’s knowledge of the complaint), the individual still must refute any nonretaliatory explanation offered to deny the claim. This burden can be doubly challenging when the power dynamic favors the alleged retaliator, as it often does (Kleinman and Thomas, 2023). In this example, the subordinate employee may not have access to budget information or the perspective to understand whether there were unexpected demands on the budget. In short, the difficulty is in proving that an action was done in response to a protected activity rather than for a legitimate managerial, business, or academic reason that just happened to coincide temporally with the protected activity.14

__________________

14 On the other hand, managers and supervisors may believe themselves to be in a difficult position if an employee or student they oversee has raised a harassment or discrimination complaint against them. Even if the accused individual has a legitimate reason to discipline the employee who complained about them, they may hesitate to do so for fear of facing additional claims of retaliation.

While the legal framework for analyzing retaliation can be effective in straightforward circumstances, its nuances and shortcomings (discussed below) may effectively deny protection to those who have raised concerns in good faith, thereby discouraging, rather than encouraging, opposition to and or reporting of sexual harassment. With this in mind, institutional policies that are merely compliant with the law—and are subsequently subjected to the same limitations of the legal framework—may not adequately address the lived experiences and fears of retaliation in academic institutions.

Examples of Retaliation in Higher Education

To better address retaliation (and fear of retaliation) in academia, institutional administrators usually have striven to understand how it manifests in an environment (Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 2015) and how it fits into the three-component sequence—protected activity, causal link, retaliatory action. This paper presents six hypothetical scenarios illustrating retaliation in academia and the challenges and obstacles that are a consequence of the narrow legal framework. These examples not only illustrate some of the many forms of retaliation in higher education, but also highlight gaps where the legal framework falls short in addressing them.

NO OPPOSITION

Hypothetical Scenario #1: Graduate Student A works in the same lab as Research Fellow B. Fellow B is the de facto supervisor when the principal investigator (PI) is traveling, which is frequent. Fellow B repeatedly makes sexual comments and jokes to Student A as well as other students in the lab. While other students laugh or respond in kind, Student A finds this conduct too childish to even acknowledge and opts to completely ignore all of it while focusing on the research. Student A never considers filing a complaint against Fellow B, in part due to Fellow B’s key role in the lab, but primarily due to Student A’s fear of a time-consuming distraction from the work. Unfortunately, Fellow B reacts to Student A’s indifferent attitude by suddenly leaving Student A off of online team chat channel discussions, group texts, and e-mail

announcements, as well as subtly implying to others that Student A is struggling in the lab. These actions create distance between Student A and the other lab members; without a support network or an involved PI, Student A begins to fall behind. Although Student A recognizes that Fellow B is favoring the students who “play along” with the sexual banter in the lab, Student A continues to withdraw and eventually leaves the lab with a master’s degree instead of a Ph.D.

Hypothetical Scenario #1: Discussion: In this scenario, the graduate student neither filed a complaint about the fellow’s sexual conduct nor explicitly opposed the conduct, instead carrying on with the work at hand. However, when Fellow B escalated the situation by isolating Student A for not “playing along,” Student A’s work environment was significantly impacted. If Student A then decided to consult the institution’s retaliation definition in its sexual misconduct policy, a typical compliance-based definition would provide no assurance of a solution under the policy. As Student A did not file a complaint, participate in the investigation of a complaint, or oppose sexual misconduct, there would be no “protected activity” to causally connect to subsequent adverse actions. Moreover, a typical anti-retaliation provision likely would not identify the isolating actions of the fellow as adverse actions.

NON-PROTECTED ACTIVITIES

Hypothetical Scenario #2: Principal Investigator (PI) C is notorious for making all graduate students work excessive hours, screaming at them for any perceived mistake, throwing pens and beakers, and making junior graduate students run personal errands. While most lab members agree that women sometimes get worse treatment than men, nobody in the lab avoids the demeaning and unhealthy conditions. A few students have discussed reporting this behavior, but they are hesitant to further upset PI C because the completion of their doctoral work requires the PI’s guidance and assistance. They also think that any investigation could fail because other lab members would be too fearful to tell the truth.

Hypothetical Scenario #2: Discussion: While suspicion of gender discrepancy in the hypothetical scenario is valid, the bulk of the problematic conduct falls into the category of the “equal opportunity harasser”—someone who subjects various people to inappropriate conduct without regard to their protected identities. Federal and state laws prohibit retaliation against individuals who engage in protected activities related to sexual misconduct and discrimination/harassment based on protected identities (sex, race, religion, etc.), but these laws typically do not address more general bullying behavior. As a result, institutions may locate their retaliation prohibitions within policies that specifically prohibit sexual misconduct and discrimination and harassment. While this placement is logical for compliance purposes, such retaliation prohibitions generally do not provide protections for people who report or object to unacceptable or problematic conduct that falls outside the scope of sexual misconduct, discrimination, and harassment, because such reports/objections are not considered protected activity and therefore do not meet the threshold requirement for retaliation protection.

In situations where the same powerful person engages in both general bullying behavior and discriminatory/harassing conduct, however, the individuals subjected to this conduct may be discouraged from complaining if they believe that only part of the complaint would have retaliation protection.15 Moreover, research suggests

__________________

15 Some institutions have policies that prohibit bullying or unprofessional behavior and contain their own anti-retaliation provisions.

these circumstances are not uncommon, because of the overlap between environments that tolerate uncivil behavior and those that tolerate sexual harassment (Lim and Cortina, 2005; NASEM, 2018). Nevertheless, gender harassment is shown to also occur in environments that endorse inappropriate conduct, bullying, disrespect, aggressive behavior, uncivil behavior,16 and so forth (NASEM, 2018).

ADVERSE ACTION – PEER RETALIATION

Hypothetical Scenario #3: After months of trying to ignore the sexist comments and sexual “jokes” loudly exchanged between two lab members, Graduate Student D reports the conduct and an investigation ensues. During the investigation, lab work schedules are changed to prevent Student D and two lab members from being in the lab at the same time. The PI says nothing overt about the investigation, but regularly laments “disruptions” that are causing their work to fall behind. The other members of the lab become aware of the investigation because they have all been interviewed. They likewise express pointed frustration and actively avoid Student D, finding excuses to deny help that was previously common. Student D hears from friends in another lab that a peer wishes Student D would just leave because of having ruined the fun “vibe” in the lab.

Hypothetical Scenario #3: Discussion: Research has shown that certain members of university communities, particularly graduate students and some faculty working in smaller disciplines and/or departments, can experience retaliation from peers who may depend on collaborative research or future professional support (Flaherty, 2019). A single perpetrator of sexual misconduct, whether faculty or student peer, is frequently enabled by the shared values and like conduct of a larger group, be it a lab, program, or classroom (Cunningham et al., 2019). This enabling behavior can manifest in the members of the larger group expressing frustration at the perceived or actual effect of a complaint of sexual misconduct on their own work or environment, even if the complaint was not against them. While retaliatory conduct is often anticipated as an angry response from the accused person, the accused person is not the only one who can engage in retaliatory behavior, under both policy and law. If someone takes an adverse action against another person because that person engaged in protected activity, they can be found responsible for retaliation under an institution’s policy even if they were not the subject of the accusation. The person subjected to this conduct, however, may not recognize the behavior of their disgruntled peers as retaliation, particularly if their institution defines retaliation narrowly in its policies. Likewise, the individuals engaging in the adverse conduct may not view their own conduct as retaliation.

ADVERSE ACTION – THROUGH PROFESSIONAL EVALUATION

Hypothetical Scenario #4: Graduate Student E, who has repeatedly experienced sexual harassment from Advisor F, turns to a Junior Faculty Member, G, in the same department, disclosing the harassment and asking for advice. Because this university requires all employees to report sexual misconduct, junior faculty member G dutifully conveys a detailed report of the alleged harassment to the Title IX coordinator, and subsequently is interviewed by an investigator. Fearful of Advisor F’s response, as F is also Faculty Member G’s senior colleague, Faculty Member G never discusses the case with colleagues and is never certain whether Advisor F is aware that Faculty Member G made the initial report. When Advisor F begins to openly undermine

__________________

16 In the NASEM 2018 report (p. 29), uncivil behavior, or incivility, is defined as “rude and insensitive behavior that shows a lack of regard for others (not necessarily related to sex or gender).”

Faculty Member G’s contributions in department meetings and in private (by opposing Faculty Member G’s application for a research leave the following semester), Faculty Member G suspects this is a form of punishment for speaking to the Title IX office but has no way to be sure. Faculty Member G, lacking evidence of the motivation behind Advisor F’s negative actions, does not file a complaint of retaliation but rather starts looking for a new position elsewhere.

Hypothetical Scenario #4: Discussion: Adverse actions against faculty and graduate students take a variety of forms, including negative assessments and denial of informal privileges. The higher education environment, which includes training and mentorship of both undergraduate and graduate students, as well as near-constant academic and/or professional evaluation, provides many opportunities for adverse actions that are directly punitive (bad grades or evaluations) as well as effective by omission (refusal of letters of recommendation, mediocre letters of recommendation, exclusion from formal and/or informal educational and professional activities). Retaliation against university faculty and graduate students can also include small but significant adverse actions, such as difficult teaching schedules, extra committee work, or exclusion from key committees or decisions. In an environment where status and advancement are frequently assessed through non- or low-monetary rewards (such as tenure and promotion, in-house awards and recognitions) and where career advancement depends heavily on support from individual faculty and/or administrators, the opportunities for retaliation are extremely varied and can be subtle.

ADVERSE ACTION – RETALIATION THROUGH COUNTERCLAIMS

Hypothetical Scenario #5: Researcher H is on a continuing faculty appointment and faces increasing gender harassment in work meetings from Co-PI I, particularly when they are alone in field research settings. When Researcher H brings this conduct to the attention of the department chair, the concerns are reported up to the equal opportunity office. However, the next day, Co-PI I files a complaint of discriminatory conduct with the equal opportunity office against Researcher H because of Co-PI I’s status as a racial minority facing discriminatory conduct. The university is obligated to respond to claims of both race-based discrimination and sexual harassment; thus, the resulting investigation will include both Researcher H’s allegations against the Co-PI I and Co-PI I’s subsequent claims against Researcher H. Rather than endure being investigated, Researcher H withdraws the complaint of sexual harassment against Co-PI I in hopes of salvaging a long-term position at the institution.

Hypothetical Scenario #5: Discussion: Retaliation may also take the form of counterclaims, such as investigations for research misconduct (Brown, 2018) or retaliation complaints (Bikales, 2020). Even counterclaims that are ultimately dismissed may have the intended effect, damaging the credibility of the original complaint, extending the procedural timeline for the original complaint, and/or tarnishing the reporter’s professional reputation. Title IX and Title VII grant individuals the right to file good-faith complaints of sexual misconduct and other forms of discrimination and harassment, and require their institutions/employers to respond promptly to assess such claims. The fact that someone has been accused of misconduct does not eliminate or reduce their right to file a complaint, even against a person who has already accused them, nor does it eliminate the institution’s/employer’s obligation to respond. While counterclaims may be filed in bad faith as a form of retaliation, without clear evidence at the outset, a retaliatory motive may not be certain.

As a result, even if the timing raises suspicions, the reality is that some level of inquiry, and perhaps a full-blown investigation, may be needed to sort through the allegations, no matter who first raised a complaint.

ADVERSE ACTION – EXTRA-INSTITUTIONAL RETALIATION

Hypothetical Scenario #6: A tenured Researcher, J, from an R1 university attends a social function sponsored by their professional association and becomes subject to unwanted touching by a Senior Colleague, K, from another institution at the event. Researcher J promptly reported the incident to the association, which quietly banned Colleague K from attending association events for 1 year. Several years later, tenured Researcher J notes a pattern of unexplained negative events occurring beyond Researcher J’s university, including being removed from prestigious editorial boards, unexpected denials of grant opportunities, and at least one failed job application. Researcher J and others suspect that the highly respected Senior Colleague, K, is utilizing their many connections to cause these negative occurrences, but Researcher J sees no pathway to contest these activities. Inquiries with the Title IX office at both Researcher J’s university and Senior Colleague K’s university yield no results because the challenged actions are not within the control or investigative scope of either school. Ultimately, Researcher J leaves academia for a government research position.

Hypothetical Scenario #6: Discussion: Academia can be a small world within different fields, specialties, and academic/professional networks. Individuals understandably can be reluctant to report misconduct by someone at their institution because, notwithstanding anti-retaliation protections at their institution, they recognize that the potential for retaliatory action can occur beyond the institution and can have long-lasting professional and academic ramifications. A complaint of sexual harassment made in any venue can provoke retaliation through a different, separate venue, effectively disrupting an institution or organization’s jurisdiction to address the conduct. Moreover, this retaliation can be extremely hard to pinpoint if it is enacted through informal networks or is shielded by peer review protections. First, reporters may fail to recognize that they have experienced extra-institutional retaliation because the absence of opportunities and connections may be less visible than more traditional (overt) retaliation. Second, a significant amount of time may have passed between the reporter’s protected activity and the adverse action, which often decreases the likelihood that a causal connection between the two can be found. Third, the adverse action could occur after the reporter and/or the accused have moved on from the institution they were associated with when the misconduct was reported, potentially limiting an institution’s ability to address reported retaliation under its own policy. Even if the institutional policy applies, misconduct that occurred entirely outside of the context of the institution can be much harder to investigate.