Toward a Common Research Agenda in Infection-Associated Chronic Illnesses: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 7 Considering Challenges and Opportunities in a Shared Research Agenda

7

Considering Challenges and Opportunities in a Shared Research Agenda

This chapter features reflections and remarks from panelists summarizing lessons and themes from the workshop. Speakers highlighted remaining challenges and future directions, as well as potential steps toward progress for the many patients suffering from infection-associated chronic illnesses. It concludes with speaker suggestions made throughout the workshop on promising strategies for patients, potential research, treatment and diagnostic approaches, and future areas for improvement.

REMAINING CHALLENGES AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

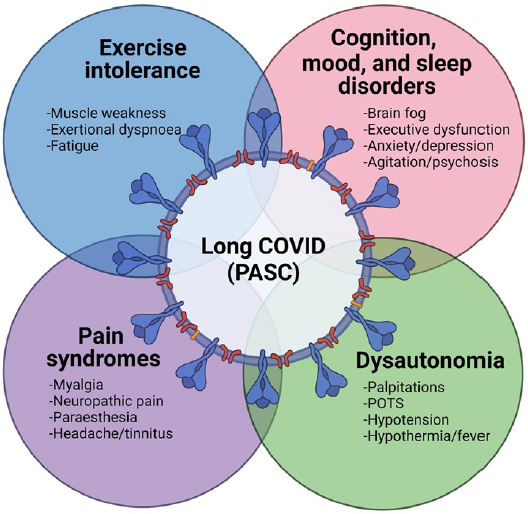

Avindra Nath, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, highlighted a central challenge: that experts in different disciplines and across sectors tend to work in silos. In the federal government, agencies that work in the chronic illness space are housed under the executive branch and are separate from the legislative branch of government, which is the branch that makes decisions on funding. In academia, Nath pointed out that while experts across disciplines are working toward similar goals, most do not collaborate in meaningful ways. Collaboration is critical to addressing the breadth of these chronic conditions, which according to Nath are the “biggest mysteries in medicine.” A key challenge in the biology of these infection-associated chronic illnesses is the heterogeneity of symptoms, he added. Individual patients express different symptoms and pathophysiology, despite significant overlap between conditions and symptoms. For long COVID, the numerous potential symptoms can be grouped into four general categories, which may have common pathophysiological mechanisms (see Figure 7-1).

NOTES: Figure 7-1 was originally published in Brain in 2022. A modified version was included in Nath’s presentation.

SOURCE: Avindra Nath presentation, June 30, 2023; Balcom et al., 2021 (by permission of Oxford University Press).

Nath said that the epidemiology of long COVID is still unclear because the disease is not well defined. Although research is advancing, there are currently no good diagnostic tests for long COVID, and no established, effective treatments. Gaps in the understanding of the pathogenesis also remain, he said. Lacking resources is a persistent issue, but Nath expressed optimism at the range of philanthropic, federal, and nonprofit entities that are contributing funds into relevant research and development activities.

Several presentations from this workshop pointed to the possibility of viral persistence in the body as a driver of chronic illness, Nath stated. Viral persistence may be linked to lingering remnants of defective virus, remaining viral products that have not been cleared, or reactivation of other latent viruses. There has also been sufficient evidence that innate immune activation, autoimmune antibodies, immune exhaustion, and genetic factors may predispose some to developing these chronic conditions.

Nath concluded with a list of potential priority areas for future progress:

- Agreeing on a common term, such as infection-associated chronic illnesses, to serve as an umbrella for uniting research endeavors.

- Prioritizing patient engagement at every step of the research process.

- Developing diagnostics and biomarkers and improved models to study diseases.

- Replicating and scaling multidisciplinary clinics.

- Studying pathogenesis within the context of clinical trials.

- Designing clinical trials in innovative ways.

Ensuring Comprehensive Advances in Science

Amy Proal, PolyBio Research Foundation, stated that her organization has created a research infrastructure that supports the study of various infection-associated chronic illness such as long COVID, ME/CFS, Lyme disease, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and others. Proal noted that PolyBio built the long COVID research consortium, which combined teams that were conducting innovative research, in order to form a dynamic group of collaborators. One of the key facets of this group is embracing open science, where members of interdisciplinary teams regularly share data, hypotheses, and ideas, Proal said, which is necessary to move studies forward and advance the science as quickly as possible. Proal also underscored the importance of studying tissue samples in addition to body fluids, saying that this is essential for understanding viral persistence and identifying reservoir sites in patients of various conditions. Imaging studies are another innovative method for identifying potential mechanisms of chronic illnesses in patients.

Moving beyond the collections of biological samples, Proal said, it will be important to understand the activity of pathogens and the immune response in those samples. To do this, sequencing technologies will be critical to get a detailed understanding of the immune and host genome expression near an identified pathogen or protein. This might include spatial transcriptomics, single nuclei RNA sequencing, microbiome-based approaches, and technologies that capture the activity of immune cells. Proal also supported performing similar forms of analysis on patients with different infection-associated chronic illnesses to obtain comparable datasets, she said. Lastly, Proal called for conducting multiple analyses on the same well-characterized study participants to maximize valuable data collection. This is at the core of the research at PolyBio, where researchers collect many different samples and types of data, and then use machine learning to look for trends that correlate in patients to identify overlapping symptoms and trends. This approach allows for defining endotypes of conditions, which is needed for identifying biomarkers, she explained. Proal concluded that defined biomarkers will encourage industry to invest in clinical trials to further advance the development of novel treatments and therapeutics.

Patients Cannot Wait

Lorraine Johnson, MyLymeData, began her closing remarks with a sense of urgency, noting that patients cannot wait for years while the ideal

diagnostics and treatments are developed. The pace of traditional research is extremely slow, and previous reasons for this slow progress, such as the lack of definitive biomarkers or murky endpoints are no longer acceptable, she stated. Johnson quoted a 2017 article by Tom Frieden, saying,

There will always be an argument for more research and for better data. But waiting for more data is often an implicit decision not to act, or to act on the basis of past practice rather than on the best available evidence. (Frieden, 2017)

It is critical for clinicians to be given clinical discretion to try different interventions that are safe and could help patients who are suffering in the present, she said, noting that patients are willing to try nearly anything. While applying different treatments, it is also necessary to capture those data and learn from them. She called for combining and capturing data wherever they are available, whether from patient registry data, biorepositories, or clinical trial results, and considering everything together in parallel.

Peter Rowe, Johns Hopkins University, followed by stating the need for support of clinical care for those who are desperate to feel better. There is a need for more clinical capacity, he said, but there is also a need for financial support for clinics, as many patients are unable to afford services in the traditional fee-for-service model. Financial support services that have been provided for HIV care or pediatric cancer could serve as a model for making treatment more accessible at clinics that specialize in chronic illnesses. Rowe noted the importance of studying clinical observations in addition to laboratory observations, as much has been learned about conditions such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome by examining cascading symptoms expressed in patients. Rowe said that while mast cell activation syndrome was not described in detail at this workshop, allergic phenomena are typically overrepresented in patients with ME/CFS. There are some treatments effective for these symptoms, but they should be studied in clinical trials with the antiviral therapeutics to examine drug interactions. He suggested merging the study of clinical observations and laboratory research.

DISCUSSION

A participant asked about the importance of incorporating systems biology and centralizing data into a common platform. Nath noted that systems biology is important for any disease but acknowledged a continuing struggle regarding how to truly share data when massive amounts are being collected, and stated that the research community should be actively pursuing this goal. Proal added that this is central to her group’s collaboration framework, and they are exploring the use of a data integration platform like LabKey. This

allows for multiple sites to participate and store data in a single open access location. She highlighted the Center Grant Mechanism (U54 grants) through NIH, which contain a clinical core and an administrative core that enable open communication, and noted the NIH requirement that data are uploaded into a central data integration platform. She encouraged NIH to continue to offer those types of grants for infection-associated chronic illnesses and added that many researchers are looking for more high-risk/high-reward, faster turnaround funding mechanisms to help them be more responsive to identified problems and needs.

Speakers also highlighted barriers that need to be proactively addressed to advance progress. Nath noted that regulations, laws, and policies can be challenging, but that they are also necessary for ensuring safety. At the clinical level, Rowe said that taking care of people with chronic illnesses has its own challenges. For example, nearly every treatment prescribed for ME/CFS patients is off-label, and then insurance companies require a prior authorization, which creates administrative burden. There are numerous barriers when it comes to insurance, he said, which can significantly slow patient care.

Tim Coetzee, National Multiple Sclerosis Society, said the invisibility that people with infection-associated chronic illness experience has begun to decrease. He noted that much more work remains to be done, but progress is being made. MS was believed to be an infection-associated chronic illness in the 1980s, but that vocabulary and terminology did not exist at the time. There was not much in the way of treatment back then either, but researchers tested the use of interferons as therapeutics with small numbers of patients. This resulted in some positive response that led to a series of trials and then led to the current standard of care, he said. Coetzee provided three lessons for the work that is still needed today:

- Doctors need to listen to patients and create space for the community that is affected in all stages of research and treatment.

- “Start where we are with what we have.” Take action with currently available tools and information in order to best care for patients who are suffering.

- Persistence is key. Collaboration, coordination, and allyship can be exerted to find ways to lower barriers.

Millions of people live with these infection-associated chronic illnesses. They are counting on researchers and clinicians who can take collective action to dramatically change their world, Coetzee concluded. Additional suggestions from speakers throughout the workshop on promising strategies for learning across diseases, potential research, treatment, diagnostic approaches, critical gaps, and next steps are outlined in Box 7-1.

BOX 7-1

Suggestions from Individual Speakersa

Promising Strategies for Learning Across Conditions

- Standardizing the evaluation of microbes in tissue so researchers can continue to learn from other disease areas and incorporate lessons from overlapping disease areas. (Horn)

- Establishing an office of infection-associated chronic illness at the National Institutes of Health to advance and coordinate critical research efforts. (Fallon, McCorkell)

- Setting up registry-style clinics around the country to collect detailed, well-classified data to understand similarities and differences between conditions and facilitate data collection. (Putrino, Johnson)

- Examining the possibility of persistent infection throughout the body, whether defective virus, reactivation of latent virus, or viral products not being cleared. (Nath, Peluso)

- Determining common behaviors and common central nervous system circuits affected by infection-associated chronic illnesses. (Miller)

- Establishing education for medical providers, the media, and the general population to understand these conditions and that complaints are legitimate and people suffering should have their experiences supported. (Fallon, Geng, Davis, O’Rourke)

- Encouraging the creation of infection-associated multisystem chronic illness clinics in major medical centers that include clinicians from multiple disciplines. (Fallon)

Potential Research, Treatment, and Diagnostic Approaches

- Following patients longitudinally throughout studies. (Komaroff)

- Ensuring meaningful engagement of patients and caregivers in all stages of the research process. (Krumholz, McCorkell, Nath)

- Enabling a virtual, decentralized clinical trial platform. Use technologies to collect samples from home, centralize tools, and remove barriers preventing people from participating. (Amitay, Marston, Putrino)

- Looking at protein–protein interactions when considering new methodologies for diagnosis. (Pretorius)

- Accelerating clinical trials of therapeutics that are most important to the patient community. (McCorkell)

- Considering implications of inclusion/exclusion criteria to ensure final factors are necessary for the trade-off in generalizability and sample attrition to determine cause and effect. (Johnson)

__________________

a This list is the rapporteurs’ summary of points made by the individual speakers identified, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. They are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

Critical Gaps

- There is a lack of animal model studies given the heterogeneity of symptoms. (Oh)

- More study is needed about mechanisms of viral persistence and immune evasion (Chertow, Deeks) and understanding the pathogenesis of these types of illnesses. (Nath)

- Comparable data on cellular immunity is lacking to pair with existing knowledge on humoral immunity, which could help study the immune response against Epstein-Barr virus before the onset of multiple sclerosis. (Ascherio)

- The lack of mechanistic understanding challenges providers in legitimizing conditions. (Geng)

- Established biomarkers are needed for long COVID and other diseases. (Cherry, Deeks, Fallon)

- A coalescing of methods is needed on how best to study pediatric long COVID compared to adult populations. (Marston)

- There is a need for more psychiatrists and funding in mental health/psychology research to support the potential treatment of the brain given downstream consequences. (Miller)

Potential Next Steps

- Pair human clinical studies with high-resolution omics study, such as immunotherapy studies, to identify causal links. (Oh)

- Build the knowledge base of potential mechanisms across conditions through engaging patients, building multidisciplinary teams, considering equity, and synergizing knowledge across syndromes. (Geng)

- Centralize collections for samples to add efficiencies, have multiple projects for blood draw, lower costs, and design to share and bring new people into the field. (Horn)

- Educate physicians and researchers to integrate fields of psychiatry with infectious disease and associated chronic illnesses. (Miller)

- Collect and study tissue samples in addition to other bodily fluids to understand the full picture of how the body is affected and potential viral reservoirs. (Horn, Proal)

- Engage industry through identifying potential pathways affected and defining endotypes and biomarkers of conditions. (Deeks, Proal)

This page intentionally left blank.