Measuring Meaningful Outcomes for Adult Hearing Health Interventions (2025)

Chapter: 4 Meaningfulness and Importance to Measure

4

Meaningfulness and Importance to Measure

As noted in Chapter 3, the initial steps of determining a core outcome set include identifying all potential core outcomes and then narrowing to a subset of outcomes that are significant in all contexts. The committee considered two main criteria for the first step in both identifying and narrowing these outcomes: meaningfulness of the outcome (with an emphasis on meaningfulness to adults with hearing difficulties and clinicians) and importance to measure (the ability of an intervention to affect the measured outcome). To achieve whole health, care systems must first understand what matters to people and then build around this to help achieve those goals (NASEM, 2023). This chapter gives an overview of the evidence on the meaningfulness of various outcomes and outcome domains in hearing health and introduces the concept of importance to measure. While all outcomes are meaningful for specific populations or purposes, the committee sought to understand which outcomes are most meaningful across contexts. Chapter 5 presents evidence on the connection between hearing health interventions and various outcomes, and Chapter 6 discusses the ability of individual measures to detect the changes in outcomes.

OVERVIEW OF MEANINGFULNESS

Traditionally, the hearing health field has relied on behavioral assessments of performance in unaided and aided conditions to evaluate success of the intervention (Moberly et al., 2023). Although measuring thresholds and word or sentence recognition is critical, these measures alone do not tell the whole story of an individual’s real world communication abilities

(Moberly et al., 2023). There are serious concerns that these behavioral audiologic measurements do not accurately reflect everyday communication abilities because they are performed in highly constrained conditions in a lab or clinic and do not fully reflect the challenges of everyday listening environments (Moberly et al., 2023). Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) are standardized,1 psychometrically valid questionnaires that collect data directly from patients about their health outcomes (Churruca et al., 2021). PROMs often ask patients about their “symptoms, health-related quality of life, and functional status” (Churruca et al., 2021, p. 1016). A breadth of research shows that objective audiologic measures poorly predict self-report measures (Cox et al., 2003; Dornhoffer et al., 2020; Fitzgerald, et al., 2024; Hoff et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2022).

At a public webinar of this committee, Russell Misheloff, an individual with hearing difficulties, shared:

It would be useful to measure better speech perception in noise. I mean, typically, we know audiologists will do it in very quiet settings, and most of us do pretty well in very quiet settings, but that’s not the real world and doesn’t really have much sense of your quality of life living in the real world.

Similarly, as noted in Tysome and colleagues:

Psychoacoustic measures of hearing such as pure-tone audiometry are most commonly used, as they are both objective and repeatable. They are of great importance in evaluating whether or not an intervention is successful from a technical point of view, and thus whether the goal of the intervention was met (e.g., closed air-bone gap or sufficient gain and output of hearing devices according to established targets). However, the ability to hear pure tones in quiet or speech in noise seldom reflects the overall effect of that hearing loss on the life of a patient, . . . nor does it act as a comprehensive measure of the therapeutic effect of any intervention to rehabilitate their hearing loss. (Tysome et al., 2015, p. 512)

As described in Chapter 3, an Australian initiative sought to identify outcomes for a self-report core outcome set for hearing rehabilitation (Allen et al., 2022). The primary outcome domains identified, in rank order from the consensus process, were:

- communication ability: 10 of 11 ranked as first in importance;

- personal relationships: 9 of 11 ranked as second or third in importance;

___________________

1 The word standardized is used here in a broad sense to indicate that the same measures are being used for specific outcomes, and that there are prescribed materials and procedures for the use of these measures. The committee does not imply that the measures are part of national or international standards.

- well-being: 5 ranked as second and 3 ranked as fourth in importance; and

- participation restrictions: 5 ranked as fourth and 3 ranked as fifth in importance.

These results indicate that there are important consequences of hearing difficulties on speech communication, but that these consequences present only part of the picture regarding potential outcomes to assess. The remaining outcomes identified can all be described generally as assessing the social, emotional, and psychological consequences of hearing difficulties.

The committee identified three main questions to assess the meaningfulness of each outcome. First, is the outcome perceived as important by adults with hearing difficulties and clinicians to their hearing health? Next, is the prevalence of the difficulty in that outcome high? In other words, are many people experiencing this difficulty? And lastly, how severe is the difficulty? The following sections outline the evidence on the meaningfulness of various outcomes based on evidence from peer-reviewed literature, industry and consumer group surveys, testimony during committee webinars, and online platform submissions for this project.

PEER-REVIEWED LITERATURE ON MEANINGFULNESS

The Partnership for Quality Measurement identifies the meaningfulness of the outcome to the target population as the starting point in the development of outcome measures (PQM, 2024). Until recently, there have been few attempts to establish the meaningfulness of various outcomes to adults with hearing difficulties. However, researchers typically predetermine which outcomes they believe would be important to adults with hearing difficulties and then ask these individuals to respond to this limited list. In a recent review of the literature on how adults self-describe and communicate about the listening difficulties they experience, McNeice and colleagues concluded:

Importantly, no study included in this review asked participants to describe their listening difficulties in their own words, nor did any study explore how participants choose to describe and communicate about their listening difficulties. (McNeice et al., 2024, p. 168)

Two older studies in the United Kingdom obtained responses to mailed questionnaires which instructed clinic patients to: “Please make a list of the difficulties you have as a result of your hearing loss. List them in order of importance, starting with the biggest difficulties. Write down as many as you can” (Tyler et al.,1983, p. 191; see also Barcham and Stephens, 1980). Questionnaires were completed at home and either mailed back or brought back to the clinic at the hearing-aid evaluation appointment. None of the

respondents considered for analyses here had worn hearing aids previously and most were estimated to have at least moderate audiometric hearing loss (Tyler et al., 1983). Each team of investigators used slightly different categories to group the self-reported hearing difficulties listed by the participants. Despite this, there was generally good agreement between these two independent surveys. In both reports, difficulties in “general conversation” and in “group conservation” were among the four most prevalent and the four most important hearing difficulties reported.

Another way studies have examined meaningfulness for individuals with hearing difficulties is through the examination of patient satisfaction with specific hearing health interventions. For example, Manchaiah and colleagues surveyed hearing aid wearers about which functional aspects of hearing aids they prioritized when choosing a hearing aid (Manchaiah et al., 2021). In that survey, the top attributes deemed very or extremely important by at least 75 percent of respondents were “improved ability to hear friends and family in quiet and in noisy settings, physical comfort, and reliability” (Manchaiah et al., 2021, p. 540). (See later in this chapter for more evidence on patient satisfaction with specific hearing interventions as gathered from industry and consumer group surveys.)

Given the sparse evidence documenting directly reported meaningfulness of outcomes, the committee turned to indirect evidence on the meaningful outcomes. The committee identified studies with reasonably large samples of adults with hearing difficulties in which the prevalence and severity of various hearing difficulties had been reported. The committee used these studies to establish meaningfulness by addressing the following questions: (1) what are the hearing difficulties reported by adults; (2) how severe do they report these difficulties to be; (3) how prevalent are these difficulties; and (4) are there emotional, social, or psychological consequences of these difficulties? The committee identified two types of datasets identified in its review that addressed these questions: (1) clinical convenience samples and (2) population studies.

Conclusion 4-1: More direct evidence, including the use of open-ended questions asked of adults with hearing difficulties, is needed to build a more robust evidence base for the nature of hearing difficulties and which outcomes are most meaningful to adults with hearing difficulties.

Clinical Convenience Samples

Clinical convenience samples come from groups that are easy to access, such as patients who attend a clinic. These data are detailed, and the sample sizes can be large, but the population segment is biased because it is not a representative sample of the entire population. Examples of outcome measures

evaluated using clinical convenience samples include the Communication Profile for the Hearing Impaired (CPHI), the Client-Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI), the Glasglow Hearing-Aid Benefit Profile (GHABP), and the Profile of Hearing Aid Performance (PHAP). These questionnaires can provide insights into outcomes that are meaningful to adults with hearing difficulties.

Communication Profile for the Hearing Impaired

Perhaps the most comprehensive assessment of the communication difficulties experienced by adults with hearing difficulties is the CPHI (Demorest and Erdman, 1986, 1987; Erdman and Demorest, 1998a,b). The CPHI consists of 145 items that are reduced to 25 scale scores, 6 of which pertain directly to communication importance or performance. The psychometrics of the CPHI have undergone rigorous evaluation; both its validity and reliability have been well established.

Of the 25 scales of the CPHI, there are nine Personal Adjustment scales that address these consequences. The bulk of the CPHI assesses the personal adjustment to hearing difficulties, including scales assessing anger, discouragement, self-acceptance, stress, withdrawal, and denial, among others. Although the CPHI is comprehensive in its assessment of the problems experienced by those with hearing difficulties, it is not typically used as an outcome measure owing, in large part, to the length of the measure. Administration of the CPHI pre- and postintervention would be burdensome, although some researchers have done so (e.g., Chisolm et al., 2004). In addition, because of copyright protections and the requirements of special software for the scoring and generation of scale scores, its feasibility as a broadly used outcome measure is further reduced.

Client-Oriented Scale of Improvement

Rather than prescribe the communication scenarios and rate their importance, the COSI asks prospective hearing-aid wearers to identify the top five listening situations they would like to improve following hearing aid use (Dillon et al., 1997). Responses from 1,770 adults seen at various clinics across Australia were placed into one of 16 categories by Dillon and colleagues (1999). The five most frequently listed listening situations identified by these adults as in need of improvement were:

- listening to television/radio at normal volume (74.8 percent),

- conversation with one or two people in quiet (47.4 percent),

- conversation with group in quiet (31.9 percent),

- conversation with one or two people in noise (24.1 percent), and

- conversation with a group of people in noise (23.5 percent).

Conversation with others in quiet and in noise represents four of the top five goals desired among these adults and can be considered meaningful to adults with hearing difficulties. The COSI also can be used for interventions beyond hearing aids (e.g., cochlear implants) (Warren et al., 2019).

Glasgow Hearing-Aid Benefit Profile

The GHABP questionnaire was developed from a large regional United Kingdom dataset (Gatehouse, 1999). Four listening situations were identified by the respondents in Gatehouse (1999) as both frequently occurring and difficult when unaided (without hearing aids):

- listening to television when volume set by others;

- conversing with one person in quiet;

- conversing on a busy street or in a shop; and

- group conversation.

These four prespecified listening situations were considered to be representative prototypes for outcome evaluation. Respondents can also identify up to four additional listening situations of importance representing patient-nominated goals.

Whitmer et al. (2014) reported results from 577 adults (with pure-tone average thresholds of 0 to 50 decibels hearing level for the frequencies of 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kilohertz) who were not using hearing aids about their difficulty in each of the four GHABP prototypical listening situations. They were separately asked to indicate how much the difficulty in that situation worries, annoys, or upsets them. Respondents indicated either “no” or “slight” difficulty when conversing with one person in quiet, but this increased to “slight” or “moderate” difficulty for the other three listening situations. Difficulties increased as a function of hearing loss. In addition, frustration with those difficulties ranged from “little” to “moderate” for the three more difficult situations but from “none” to “little” for conversing with one person in quiet. Statistically significant main effects of hearing loss were observed in addition to statistically significant main effects of conversing with one person in quiet.

Profile of Hearing Aid Performance (and Benefit)

The PHAP is a 66-item survey assessing the frequency of difficulty in a variety of listening conditions (Cox and Gilmore, 1990; Cox, 1996). Of the 66 items, 48 focus on speech communication and the remainder focus on the loudness or aversiveness of environmental sounds. Cox and Gilmore (1990) reported results from 225 experienced hearing aid wearers with mild to moderate losses seen in the clinic. Among the 48 speech-communication

items, the five with the highest frequency of difficulty (mean percentage) were as follows:

- When I am in a room with the door closed and I want to overhear a conversation going on outside the door, I have to strain to listen (84.1 percent).

- When I am listening to a speaker who is talking to a large group, and I am seated toward the rear of the room, I must make an effort to listen (78.1 percent).

- When I am at a large, noisy party, conversation is very confusing (76.5 percent).

- When I am in a crowd with a friend who does not want others to overhear our conversation, I have trouble hearing as well (72.9 percent).

- When I am listening to the news on the car radio, and family members are talking, I have trouble hearing the news (71.8 percent).

Several of the situations in which respondents most frequently had difficulty involved listening to speech when others are talking in the background. Interestingly, the phrasing of the top two items of the PHAP listed above appears to tap listening effort rather than performance. Further, of these top five most-frequently difficult listening situations, only one, the last item shown above, is included in the 24-item abbreviated PHAP (APHAP) (Cox and Alexander, 1995; Cox, 1996). The PHAP and shortened APHAP focus on aided conditions (e.g., the perspective of the person wearing hearing aids). To assess the individual’s perceived differences (i.e., with a hearing aid versus without a hearing aid) and compare differences over time, an expanded questionnaire was developed—the Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit (PHAB), which has the same items and subscales as the PHAP (Cox and Alexander, 1995; Cox, 1996). An abbreviated PHAB (APHAB) is commonly used as a self-report outcome today and is further discussed in Chapter 6.

Conclusion 4-2: Studies of clinical convenience samples of adults converged on similar conclusions. Specifically, adults with hearing difficulties have problems with communication, especially in groups, and these problems often lead to frustration. Frustration with hearing difficulties is considered a negative emotional reaction to those difficulties. Emotional and social difficulties are commonplace among those who have trouble hearing.

Population Studies

As compared to clinical convenience samples, population studies are conducted on a larger scale (capturing a community, region, or nation), making the data more representative. However, there is a limitation on how

many questions can be asked and the level of detail of these surveys because of the burden on respondents. The following sections highlight population studies both within the United States, primarily the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), as well as from other countries.

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

NHANES is a national survey that collects data on a wide range of health concerns for different age distributions.2 The 2017 to 2020 NHANES survey (NHANES, 2021) included three main items regarding perceived hearing difficulties for adults (age 20 and older): (1) the general condition of one’s hearing with responses ranging from “excellent” to “deaf;” (2) the frequency of difficulties conversing in noise with responses ranging from “never” to “always;” and (3) the frequency of frustration when talking with friends and family, with responses again ranging from “never” to “always.”

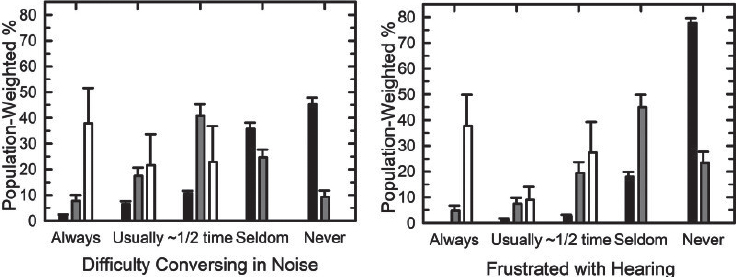

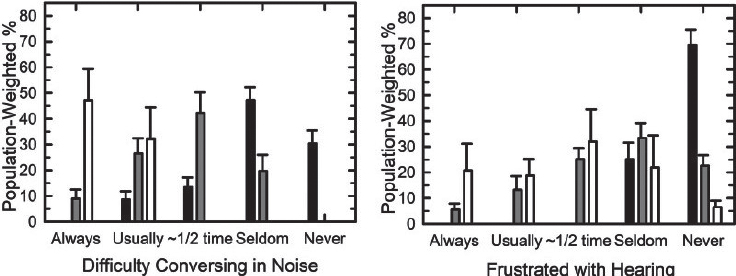

For the question on the general condition of one’s hearing, 76.2 percent respondents rated their hearing as excellent or good, 21.2 percent rated it as having “a little trouble” or “moderate trouble,” and 2.4 percent said they had “a lot of trouble” or were deaf (Humes, 2024). Humes (2024) analyzed data for the second two questions by large age groups (20–69 and over age 70) and by self-reported hearing difficulty. Figure 4-1 and Figure 4-2 show the population-weighted self-reported responses for the items related

NOTE: Black bars are for those with self-reported hearing difficulties rated as “excellent” or “good,” gray bars are for those with self-reported hearing difficulties rated as “a little” or “moderate” trouble, and white bars are for those reporting “a lot” of hearing difficulties or deaf. NHANES = National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

SOURCE: Humes, 2024. CC BY-NC-ND.

___________________

2 For more information, see https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.html (accessed January 13, 2024).

NOTE: Black bars are for those with self-reported hearing difficulties rated as “excellent” or “good,” gray bars are for those with self-reported hearing difficulties rated as “a little” or “moderate” trouble, and white bars are for those reporting “a lot” of hearing difficulties or deaf. NHANES = National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

SOURCE: Humes, 2024. CC BY-NC-ND.

to hearing difficulties in noise and frustration with hearing. Humes analysis revealed that overall, the prevalence of self-reported difficulty conversing in noise increased with the severity of the hearing condition; 19 to 22 percent of those with self-reported excellent or good hearing said they had difficulty conversing in noise at least half the time, while the percentage was 66 to 78 for those with a little or moderate trouble hearing, and 82 to 94 percent for those with more severe hearing difficulties (Humes, 2024).

Regarding the question of frustration when talking with friends and family, most (70 to 80 percent) adults with self-reported excellent or good hearing indicate they never feel frustrated. In comparison, 32 to 44 percent of those with a little or moderate trouble reported feeling frustrated at least half of the time (Humes, 2024). As noted by Humes,

Frustration is an emotional reaction to the hearing difficulty and represents a more significant concern regarding negative impact of this difficulty on the individual’s emotional wellness and overall well-being.

Overall, these analyses show difficulty conversing in noise and frustration with hearing as prevalent concerns among adults with hearing difficulties.

International Population Studies

Lutman and colleagues (1987) reported the results from 1,691 individuals who completed the second in-clinic stage of a two-stage random sampling process for the United Kingdom adult population (Davis, 1983; Lutman et al., 1987). A series of nine questions was asked of all in-clinic

participants, who ranged in age from 17 to 89 years. Principal-components analysis by Lutman et al. (1987) of the response to these nine questions identified four components:

- everyday speech;

- speech in quiet;

- sound localization; and

- handicap.

“Everyday speech” represents speech communication in a background of competing sounds. The “handicap” outcome domain was based on the frequency with which hearing problems “restrict enjoyment of social and personal life,” create “a feeling of being cut off from things,” and “lead to embarrassment.” Handicap captures social, emotional, and psychological consequences of hearing difficulties. Of these four principal components, approximately two-thirds of the variance was accounted for by “everyday speech communication” and “handicap” combined.

In the 1980s, the United Kingdom’s (UK’s) Medical Research Council National Study of Hearing was conducted to identify the prevalence and distribution of hearing loss in the UK (Akeroyd et al., 2019). The sample size and quality of the design made it particularly notable for the time, and since it was never repeated, it remains the “primary U.K. source for prevalence of auditory problems” (Akeroyd et al., 2019, p. 1). After an initial broad postal survey sent to 48,313 adults selected at random from the electoral registers, a representative sample of adults was selected for in-clinic follow-up using a custom set of survey questions. Some survey items inquired about the degree of difficulty experienced (e.g., a little, moderate, a lot) whereas others inquired about the frequency of occurrence of such difficulties (e.g., never, sometimes, always). The final in-person test sample included 2,578 adults. The study also collected data on “the prevalence and characteristics of both measured hearing impairment and self-reported hearing disability in adults (18–80 years) as a function of severity, age, gender, occupational group, and occupational noise exposure” (Akeroyd et al., 2019, p. 2).

Uchida and colleagues reported results from a population study in Japan of 2,150 adults 40 to 79 years of age; a total of 994 (45 percent) perceived that they had hearing loss (Uchida et al., 2003). Among these 994 adults, 83 percent responded “yes” or “occasionally” when asked whether their hearing difficulties resulted in speech-communication problems and 42 percent responded the same way when asked whether they had difficulty following conversations that included 4–5 people in a quiet room. Twenty-two percent responded similarly regarding experiencing restrictions to their daily life activities, and 20 percent indicated that their hearing difficulties led to a loss of self-confidence.

In an online survey of 2,352 Dutch volunteers, Boeschen-Hospers and colleagues (2016), using the Amsterdam Inventory for Auditory Disability and Handicap, asked how often the respondent could hear effectively in 29 different listening situations. Response options were: “almost always,” “frequently,” “occasionally,” and “almost never.” The top five listening situations with the highest response percentages of either “occasionally” or “almost never” hearing effectively were as follows:

- follow the conversation among a few adults at dinner;

- carry on a conversation with someone in a crowded meeting;

- carry on a conversation with someone on a busy street;

- carry on a conversation with someone in a bus or car; and

- hear from what direction a question is asked during a meeting.

Of the next five listening situations, two had to do with difficulty understanding speech and the other three involved difficulties in localizing sound. Kramer and colleagues (1998) had previously used the same measure in a smaller convenience sample (239 people with hearing difficulties) and showed that “handicap resulting from the inability to understand speech in noise is most strongly felt” (p. 302).

A population study of 1,711 unaided adults 18 to 97 years of age by von Goblenz et al. made use of stratified random samples of residents in northwest Germany (von Gablenz et al., 2018). A brief 17-item version of the 49-item Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing (SSQ) scale was used (Gatehouse and Noble, 2004). The SSQ provides a detailed description of a specific scenario and then asks a question such as “Can you follow the conversation?” or “Can you tell how far away a sound is?” An 11-point response scale ranging from 0 (“not at all”) to 10 (“perfectly”) is used. Results for the SSQ-17 were presented stratified by average pure-tone hearing loss but, regardless of hearing loss severity, the most commonly identified listening situations that were difficult were tasks that involved following conversations in noise including competing speech, discerning the distance and movement of sound sources, and listening effort required during conversations.

Conclusion 4-3: Population studies support the identification of several outcomes as being meaningful to adults with hearing difficulties: (1) communication performance, especially in groups, in background noise, and on the telephone; (2) sound localization; (3) identification or awareness of important environmental sounds (e.g., vehicles, warnings); and (4) psychosocial consequences of hearing difficulties. Listening effort emerged in one population study (von Gablenz et al., 2018) as well as in the Profile of Hearing Aid Performance (Cox and Gilmore, 1990) but this represents limited evidence regarding its importance at present.

OTHER SOURCES OF EVIDENCE ON MEANINGFULNESS

Apart from the peer-reviewed published literature, a variety of resources provide insights on outcomes that are meaningful to adults with hearing difficulties and clinicians. These sources include industry and consumer group surveys, testimony from this committee’s public webinars, and comments received by this committee through its online platform.

Industry and Consumer Group Surveys

Some of the most direct evidence of the meaningfulness of specific outcomes and outcome domains is from surveys by industry and consumer groups that directly ask individuals with hearing difficulties about what matters the most to them regarding their hearing health. However, these types of surveys tend to ask about the effect of hearing loss itself or satisfaction with specific interventions rather than the meaningfulness of specific improvements to their hearing health.

MarkeTrak

MarkeTrak is a series of surveys conducted by the Hearing Industries Association to collect data on industry trends.3 MarkeTrak 10 (completed in 2019) surveyed 3,132 individuals with hearing difficulties (Powers, 2020). The 969 hearing aid wearers within this group were directly asked about the factors that drove satisfaction with their hearing aids. The most highly ranked factors were hearing aid performance in quiet and noise, sound quality, and effectiveness of health care professionals (Appleton-Huber, 2022). When compared with other people with hearing difficulties in the survey, hearing aid wearers’ satisfaction with their hearing in all listening situations was higher than those who did not wear hearing aids.

EuroTrak

In 2009, the European Hearing Instrument Manufacturers Association (EHIMA) created the EuroTrak (Hougaard and Ruf, 2011). This study was modeled after the MarkeTrak as a comprehensive study on hearing loss and hearing aids in Germany, France, and the UK. The EuroTrak has since been implemented in many countries across Europe and the Asia-Pacific region (EHIMA, n.d.). The survey is now the “largest comparative multicountry study on hearing loss and hearing aid usage” (EHIMA, n.d.). Both the MarkeTrak and the EuroTrak include common questions that make comparison across countries possible despite varying delivery systems for hearing aids (Powers and Bisgaard, 2022). A comparison between the 2022 MarkeTrak (MT2022),

___________________

3 For more information see https://betterhearing.org/policy-research/marketrak/ (accessed May 13, 2024).

the 2022 EuroTrak in France (ET-F) and the 2022 EuroTrak in Germany (ET-G) found that all three countries have similar rates of self-reported hearing loss ranging from 10 to 13 percent (Powers and Bisgaard, 2022). Over 60 percent of the respondents in all three countries reported that they felt like they should have obtained hearing devices sooner because of the improvement of social interactions and the reduction of fatigue (Powers and Bisgaard, 2022). The EuroTrak not only collects valuable data about hearing impairment and the use of hearing aids in over a dozen countries but it also creates comparable data that show trends across countries.

In addition to the demographic data, the EuroTrak also collects information on patient satisfaction with hearing aids across a range of listening situations, as well as satisfaction with the dispenser, the sound quality and signal processing, and the product features (Hougaard and Ruf, 2011). Lastly, the EuroTrak asks, “Since you started using your hearing aid(s), please rate the changes you have experienced in each of the following areas, which you believe are due to your hearing aid(s)” (Hougaard and Ruf, 2011). When Germany, the United Kingdom, and France were compared, by percentage of people who noted improvement with hearing aids, the most common responses were effective communication (Germany 67 percent, United Kingdom 68 percent, France 79 percent), social life (Germany 53 percent, United Kingdom 57 percent, France 74 percent), relationships at home (Germany 47 percent, United Kingdom 53 percent, France 71 percent), and the ability to participate in group activities (Germany 58 percent, United Kingdom 60 percent, France 68 percent) (Hougaard and Ruf, 2011).

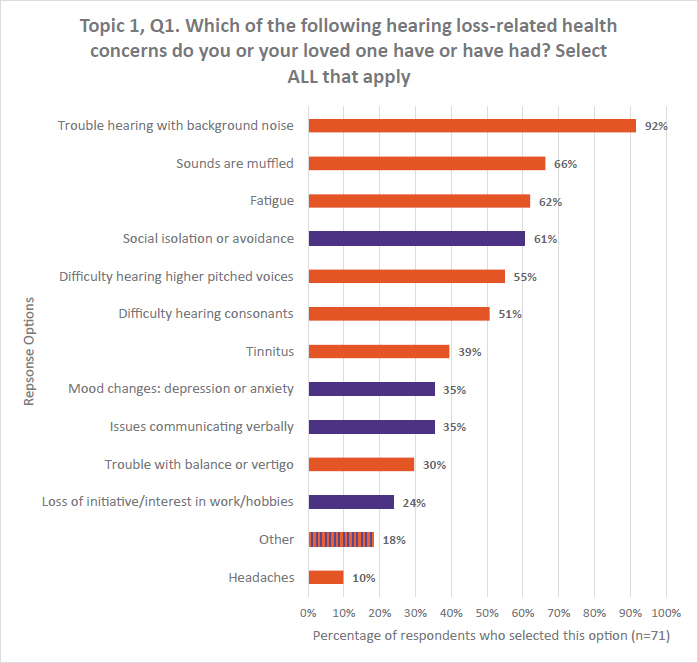

HLAA Voice of the Patient Report

In 2021, the Hearing Loss Association of America (HLAA) held an externally led patient-focused meeting on drug development for people living with sensorineural hearing loss and their families (HLAA, 2021). Subsequently, HLAA published a Voice of the Patient report with the findings from this meeting. As shown in Figure 4-3, when asked about hearing loss–related health concerns, meeting participants reported challenges hearing with background noise (92 percent), muffled sounds (66 percent), fatigue (62 percent), difficulty hearing consonants (51 percent), tinnitus (39 percent), trouble with balance or vertigo (30 percent), difficulty hearing higher-pitched voices (26 percent), headaches (10 percent), and other physical concerns (18 percent) (HLAA, 2021). The report also listed psychosocial health concerns with social isolation or avoidance (61 percent), depression or anxiety (35 percent), issues with verbal communication (35 percent), and loss of initiative in work and hobbies (24 percent) (HLAA, 2021).

Respondents identified difficulty hearing in background noise, social isolation or avoidance, and fatigue as the most troublesome hearing-related health concerns (HLAA, 2021). Eighty-eight percent of respondents reported

NOTE: orange bars = physical health concerns; purple bars = psychosocial health concerns.

SOURCE: HLAA, 2021. Reprinted with permission from HLAA, hearingloss.org.

that because of their hearing loss it is a struggle, or they are unable, to participate in social events (HLAA, 2021). Fifty-seven percent of respondents reported that their hearing loss made communication with family members difficult (HLAA, 2021). When it came to specific challenging listening environments the survey reflected that 43 percent of respondents felt there were barriers to attending concerts and events and 29 percent found school or work challenging (HLAA, 2021). Additional effects of hearing loss were difficulties accessing health care, safety, challenges running errands, and not being able to watch television. People with hearing loss reported worrying about future effects such as an increased risk of dementia (67 percent) and losing social connection with a spouse or child (60 percent) (HLAA, 2021).

Conclusion 4-4: Themes of meaningful outcomes among industry and consumer group surveys include speech communication (particularly speech in noise and other complex listening situations), social connection, psychological health, and listening fatigue.

Testimony from Public Webinars

The committee hosted two public webinars to hear directly from adults with hearing difficulties and clinicians about what outcomes are the most meaningful and therefore should be considered for a core set.4 The quotes provided in this section were chosen to represent the range of individuals who testified to the committee and to highlight the most relevant issues raised during the webinars in response to the committee’s questions and the statement of task.

The committee asked adults with hearing difficulties to share their goals for their hearing health (see Box 4-1). The most common goal noted by the panelists was that they wanted to improve their speech communication. In many cases, their personal challenges communicating with family

BOX 4-1

Hearing Health Goals

On a personal level I have a 3-year-old, almost 3-year-old, grandson and [I can maybe] understand half the time or a third of the time what he is saying because his voice is soft and the pitch . . . So that’s what drives me to a more dramatic solution in my personal life.

—Kerry Sullivan

My goal is to be able to have the capacity to engage and actively participate one on one. And to attend performances and programs in public venues, including in environments that are less than ideal from a hearing perspective, and to do so without undue stress, inconvenience, fatigue, and embarrassment.

—Russell Misheloff

I think it would be useful to measure a better speech perception and in noise. I mean, typically, we know audiologists will do it in very quiet settings, and most of us do pretty well in very quiet settings, but that’s not the real world and doesn’t really have much sense of your quality of life living in the real world.

—Russell Misheloff

These quotes were collected from the committee’s webinars.

___________________

4 The webinar recordings can be accessed at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/41996_02-2024_meaningful-outcome-measures-in-adult-hearing-health-care-webinar-1 and https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/42414_04-2024_meaningful-outcome-measures-in-adult-hearing-health-care-webinar-2.

members inspired them to seek out hearing health care. In particular, multiple panelists voiced that they were unable to understand young children and grandchildren because of the speed and high frequency of their speech, which was a major motivator toward getting hearing aids. Being able to hear with background noise was another significant challenge noted by participants. They noted that larger social gatherings usually take place in noisy environments making it very difficult for people with hearing loss to engage in conversation.

Several panelists shared how challenging their hearing loss made it for them to keep up in the workplace environment and the relief they experienced with hearing interventions. As shown in Box 4-2, multiple panelists

BOX 4-2

Effects of Hearing Loss in the Workplace

My ability to focus and concentrate in a business setting is so much greater now, and I just feel like I can process things so much more quickly and really follow what is going on. I had no idea that the hearing loss was holding me back from a professional standpoint.

—Chris Greame

I’m happy though to speak to some of those aspects of hearing loss that I think have not been addressed for me . . . which is the bigger picture of how it affects our work. In my case, I’ve had to change what I do because of my hearing loss. There are certain patients that it is very difficult for me to work with.

—Suzanne Johnston

I worked and still am working with executive leadership development. I made a conscious decision that I never talked about it. I can’t be a trainer because I’m going to miss the jokes in the classroom to be able to interact and to work deeply with them and so that was a conscious choice because there is no solution for that. Instead, I went into curriculum development.

—Wynne Whyman

In my 60s working in nursing homes, in meetings I would remind people that I had hearing aids and I had difficulty hearing, but nobody paid attention. It didn’t affect how anybody behaved in terms of making themselves accessible to me.

—Elizabeth Pentin

These quotes were collected from the committee’s webinars.

BOX 4-3

Listening Effort and Listening Fatigue

Over the years what I found, and I didn’t even realize this was going on, the amount of energy it takes in a social setting or in a business setting professionally to really communicate and process [. . . .] Because my energy levels were higher my productivity levels were higher, my ability to respond and think and process improved.

—Chris Greame

The thing I noticed when I put in these new hearing aids was that internally, I wasn’t straining and putting my inner self out there to hear what people are saying. I didn’t have to work so hard.

—Elizabeth Pentin

These quotes were collected from the committee’s webinars.

said they had to shift their career paths because they could only perform specific roles with their hearing loss.

Multiple panelists expressed their struggles with listening fatigue as a consequence of their hearing loss. As shown in Box 4-3, the stress and exhaustion caused by hearing loss had a detrimental effect on their ability to fully participate and be productive in their daily lives.

During the second webinar, the committee also heard from hearing health professionals about their impressions of their patients’ goals (see Box 4-4).

Online Platform Submissions

The committee invited members of the public to submit written comments answering a series of questions through an open platform. The following sections present samples from the 47 comments submitted to this committee by adults with hearing loss, their care partners, and hearing health professionals. Box 4-5 shows the range of concerns shared with the committee by adults with hearing difficulties.

Through the open platform, the committee asked clinicians about what they hear frequently from their patients as the most meaningful outcomes related to their hearing loss. Box 4-6 displays some of the responses. The overwhelming response was that their patients want to be able to understand speech in noisy environments.

BOX 4-4

Clinician Perspectives on Patient Goals

The common goals are understanding conversations, especially in background noise. Hearing grandkids, hearing soft speech, hearing at church.

—Lee Cottrell, Balance and Hearing Institute at Farragut ENT & Allergy

There’s a difference between a new hearing aid user and an existing hearing aid user, and I think often that new users [don’t] quite know what to expect. So, I think they have some shifting goals as their experience changes.

—Tim Steele, Associated Audiologists, Inc.

[Goals] change over time, but it is unbelievably critical to try to unearth those goals in the beginning because I may pick a different product or treatment option if it’s a musician versus a car mechanic versus somebody else.

—Erika Person, Flex Audiology

These quotes were collected from the committee’s webinars.

BOX 4-5

What Matters to Adults with Hearing Difficulties

My personal goal is to stay as fit, as active, and as engaged as I possibly can for the remainder of my life. This means physical health, mental health, and especially hearing health.

—Adult with hearing difficulties in Salem, OR

My goal: to fully participate in all aspects of life. That’s more than just communication.

—Adult with hearing difficulties in Aurora, CO

Most important to me [. . .]: to again one day really hear without even thinking about it in all types of environments. This includes: one-on-one in restaurants; small groups of friends in restaurants; more than one other person in someone’s home with typical noisy HVAC; meetings around a conference table with no hearing loop; lecture room with no hearing loop; theater with no hearing loop; movie theater with no technology or less than adequate technology and no open captioning.

—Adult with hearing difficulties in New York, NY

These quotes were collected from the committee’s open platform.

BOX 4-6

What Clinicians Hear from Their Patients About What Is Most Meaningful

Their stated primary desires are usually the benefit of speech in noise understanding, help with concentration, and better interactions with family/friends on a daily basis.

—Hearing Health Professional in Argyle, TX

The primary goal for most hearing aid wearers is improved speech perception, and while measures of audibility and subjective benefit are important, these measures fail to ascertain whether amplification has truly improved a patient’s speech recognition ability.

—Hearing Health Professional in Tucson, AZ

Patients’ primary concerns include speech intelligibility in noise.

—Hearing Health Professional in Cleveland, OH

Their main concerns have a lot to do with being able to hear in conversations, especially in background noise situations.

—Hearing Health Professional in Tucson, AZ

As a clinician in an ENT clinic, my patients often complained about their inability to understand speech in noise and quality-of-life issues due to hearing loss.

—Hearing Health Professional in Dorchester, MA

Quality of life; hearing/understanding speech better, especially in noisy environments; being able to effectively communicate while participating in social activities; cognitive decline.

—Hearing Health Professional in Orlando, FL

The most important outcome for people who need assistance is the ability to follow conversations in normal (noisy) environments. The resulting social connections are important for overall health. Audibility (and even words-in-noise recognition) are important, but follow a noisy conversation? How much listening effort does it take? How often does the patient have to ask for content to be repeated?

—Hearing Health Professional in Oakland, CA

These quotes were collected from the committee’s open platform.

Conclusion 4-5: Themes of meaningful outcomes among the committee’s public webinars and online platform submissions include speech communication (particularly speech in noise and other complex listening situations), social connection, participation, and listening fatigue.

IMPORTANCE TO MEASURE

The committee considered “importance to measure” as another factor in determining a core outcome set. First, importance to measure includes the extent to which the outcome is controllable, meaning that an intervention can change the outcome (Velentgas et al., 2013). This type of “importance” is distinct from the listening experiences considered by adults with hearing difficulties to be “important” to them. The concept is often associated with minimally clinically important differences (Velentgas et al., 2013). (See Chapter 6 for more on minimal clinically important differences.) Whereas an outcome may be very meaningful to adults with hearing difficulties and clinicians, a measure used for evaluating the core outcome set needs to be able to detect the smallest change deemed important to adults with hearing difficulties. Importance to measure also may be considered by whether the information gained by measurement helps inform treatment decisions (Velentgas et al., 2013).

The Partnership for Quality Measurement includes importance to measure as a criterion in their measurement endorsement process (PQM, 2023). It is outside of this committee’s scope to conduct a full measure review, but the Partnership for Quality Measurement’s comprehensive instructions on conducting measure evaluation greatly informed the committee’s process. The rubric asks specific questions including whether use of the measure will lead to improved outcomes and whether there is credible evidence linking the intervention to improved outcomes. Importance to measure is further discussed in Chapters 5 and 6.

FINDINGS

Finding 4-1: Measurement of hearing ability in ideal listening conditions does not necessarily reflect real-world communication abilities or the outcomes that are most meaningful to adults with hearing difficulties.

Finding 4-2: The committee used three main questions to determine meaningfulness of outcomes:

- Is the outcome perceived as essential by adults with hearing difficulties or clinicians?

- Is the prevalence of the difficulty high?

- How severe is the difficulty?

Finding 4-3: There is a significant lack of research that directly asks adults with hearing difficulties about what outcomes are most meaningful to them. Researchers tend to predetermine which outcomes they ask about rather than asking open-ended questions.

Finding 4-4: Surveys of adults with hearing loss tend to ask more about the effect of the hearing loss itself or their satisfaction with specific interventions rather than the meaningfulness of specific improvements (outcomes) of their hearing health.

Finding 4-5: Studies of clinical convenience samples show adults report problems with communication, especially in groups, and that these problems often lead to frustration. Hearing-related difficulties are common among those who have trouble hearing.

Finding 4-6: Population studies identify several outcome domains as being meaningful to adults with hearing difficulties: (1) communication performance, especially in groups, in background noise, and on the telephone; (2) sound localization; (3) identification or awareness of important environmental sounds (vehicles, warnings); and (4) the emotional and social consequence of hearing difficulties. Listening effort emerged as a meaningful outcome in one recent population study.

Finding 4-7: MarkeTrak 10 revealed that the most highly ranked factors for satisfaction among hearing aid wearers were hearing aid performance in quiet and noise, sound quality, and effectiveness of health care professionals. Hearing aid wearers had the least satisfaction with conversations in noise, talking on the phone, hearing over distance, and large group conversations.

Finding 4-8: A 2021 HLAA meeting of people living with sensorineural hearing loss found that their most troublesome concerns were hearing with background noise, social isolation or avoidance, and fatigue.

Finding 4-9: During public testimony to this committee, participants primarily noted challenges with speech communication (particularly understanding speech in a noisy environment and soft sounds). Other concerns were communicating with family, listening effort and fatigue, and having the ability to participate in their personal and professional lives.

Finding 4-10: Comments submitted on the committee’s online platform by adults with hearing difficulties and clinicians primarily focused on the ability to understand speech in noise, as well as full participation in their desired activities.

Importance to Measure

Finding 4-11: Importance to measure is the extent to which the outcome is controllable, meaning that the intervention can change the outcome, or whether the information gained helps inform treatment decisions.

Finding 4-12: While an outcome may be very meaningful to adults with hearing difficulties and clinicians, if the intervention cannot significantly change the outcome, that outcome should not be included in a core set.

RECOMMENDATION

Limited direct research has been performed to determine which outcomes are most meaningful for adults with hearing difficulties and for clinicians. Existing evidence is mostly indirect, as it is usually derived from surveys of satisfaction with interventions or studies of the prevalence and severity of hearing difficulties that are typically based on (1) constrained surveys wherein the choices are developed by others (e.g., researchers and clinicians) and (2) varying degrees of direct input from those with hearing difficulties. More direct evidence, including answers to open-ended questions asked of adults with hearing difficulties, is needed to build a more robust evidence base concerning the nature of hearing difficulties and which outcomes are most meaningful to adults with hearing difficulties.

Recommendation 4-1: Sponsors of hearing health research should fund additional research to engage adults with hearing difficulties, their communication partners, and clinicians to determine the most meaningful outcomes based on direct evidence from adults with hearing difficulties.

Sponsors of hearing health research may include a wide variety of partners including federal agencies (e.g. the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Department of Defense, the National Institutes of Health, the Veterans Administration), foundations, professional organizations, and industry.

REFERENCES

Akeroyd, M. A., G. G. Browning, A. C. Davis, and M. P. Haggard. 2019. Hearing in adults: A digital reprint of the main report from the MRC National Study of Hearing. Trends in Hearing 23:2331216519887614.

Allen, D., L. Hickson, and M. Ferguson. 2022. Defining a patient-centred core outcome domain set for the assessment of hearing rehabilitation with clients and professionals. Frontiers in Neuroscience 16:787607.

Appleton-Huber, J. 2022. What is important to your hearing aid client...And are they satisfied? https://hearingreview.com/hearing-loss/patient-care/counseling-education/what-important-to-your-hearing-aid-clients-are-they-satisfied (accessed May 22, 2024).

Barcham, L. J., and S. D. Stephens. 1980. The use of an open-ended problems questionnaire in auditory rehabilitation. British Journal of Audiology 14(2):49–54.

Boeschen-Hospers, J. M., N. Smits, C. Smits, M. Stam, C. B. Terwee, and S. E. Kramer. 2016. Reevaluation of the Amsterdam Inventory for Auditory Disability and Handicap using item response theory. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 59(2):373–383.

Chisolm, T. H., H. B. Abrams, and R. McArdle. 2004. Short- and long-term outcomes of adult audiological rehabilitation. Ear and Hearing 25(5).

Churruca, K., C. Pomare, L. A. Ellis, J. C. Long, S. B. Henderson, L. E. D. Murphy, C. J. Leahy, and J. Braithwaite. 2021. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs): A review of generic and condition-specific measures and a discussion of trends and issues. Health Expectations 24(4):1015–1024.

Cox, R. M. 1996. Phonak Focus 21: The Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit (APHAB)—Administration and application. Stafa, Switzerland: Phonak AG.

Cox, R. M., and G. C. Alexander. 1995. The Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit. Ear and Hearing 16(2):176–186.

Cox, R. M., and C. Gilmore. 1990. Development of the Profile of Hearing Aid Performance (PHAP). Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 33(2):343–357.

Cox, R. M., G. C. Alexander, and C. M. Beyer. 2003. Norms for the International Outcome Inventory for Hearing Aids. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 14(08):403–413.

Davis, A. C. 1983. 2 - Hearing disorders in the population: First phase findings of the MRC National Study of Hearing. In Hearing science and hearing disorders, edited by M. E. Lutman and M. P. Haggard. London, UK: Academic Press. Pp. 35–60.

Demorest, M. E., and S. A. Erdman. 1986. Scale composition and item analysis of the Communication Profile for the Hearing Impaired. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 29(4):515–535.

Demorest, M. E., and S. A. Erdman. 1987. Development of the Communication Profile for the Hearing Impaired. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders 52(2):129–143.

Dillon, H., A. James, and J. Ginis. 1997. Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI) and its relationship to several other measures of benefit and satisfaction provided by hearing aids. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 8(1):27–43.

Dillon, H., G. Birtles, and R. Lovegrove. 1999. Measuring the outcomes of a national rehabilitation program: Normative data for the Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI) and the Hearing Aid User’s Questionnaire (HAUQ). Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 10(2):67–79.

Dornhoffer, J. R., T. A. Meyer, J. R. Dubno, and T. R. McRackan. 2020. Assessment of hearing aid benefit using patient-reported outcomes and audiologic measures. Audiology and Neurotology 25(4):215–223.

EHIMA (European Hearing Instrument Manufacturers Association). n.d. Surveys. https://www.ehima.com/surveys/ (accessed September 24, 2024).

Erdman, S. A., and M. E. Demorest. 1998a. Adjustment to hearing impairment I: Description of a heterogeneous clinical population. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 41(1):107–122.

Erdman, S. A., and M. E. Demorest. 1998b. Adjustment to hearing impairment II: Audiological and demographic correlates. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 41(1):123–136.

Fitzgerald, M. B., K. M. Ward, S. P. Gianakas, M. L. Smith, N. H. Blevins, and A. P. Swanson. 2024. Speech-in-noise assessment in the routine audiologic test battery: Relationship to perceived auditory disability. Ear and Hearing 45(4):816–826.

Gatehouse, S. 1999. Glasgow Hearing Aid Benefit Profile: Derivation and validation of a client-centered outcome measure for hearing aid services. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 10(2):80–103.

Gatehouse, S., and W. Noble. 2004. The Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing Scale (SSQ). International Journal of Audiology 43(2):85–99.

HLAA (Hearing Loss Association of America). 2021. Voice of the patient report: HLAA’s externally led patient-focused drug development (PFDD) meeting for people and families living with sensorineural hearing loss. Rockville, MD: Hearing Loss Association of America.

Hoff, M., J. Skoog, T. H. Bodin, T. Tengstrand, U. Rosenhall, I. Skoog, and A. Sadeghi. 2023. Hearing loss and cognitive function in early old age: Comparing subjective and objective hearing measures. Gerontology 69(6):694–705.

Hougaard, S., and S. Ruf. 2011. EuroTrak. https://hearingreview.com/hearing-products/amplification/assistive-devices/eurotrak (accessed September 24, 2024).

Humes, L. E. 2024. Demographic and audiological characteristics of candidates for over-the-counter hearing aids in the United States. Ear and Hearing 45(5):1296–1312.

Kramer, S. E., T. S. Kapteyn, and J. M. Festen. 1998. The self-reported handicapping effect of hearing disabilities. Audiology 37:302–312.

Lutman, M. E., E. J. Brown, and R. R. A. Coles. 1987. Self-reported disability and handicap in the population in relation to pure-tone threshold, age, sex and type of hearing loss. British Journal of Audiology 21(1):45–58.

Manchaiah, V., E. M. Picou, A. Bailey, and H. Rodrigo. 2021. Consumer ratings of the most desirable hearing aid attributes. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 32(08):537–546.

McNeice, Z., D. Tomlin, B. Timmer, C. E. Short, G. Nixon, and K. Galvin. 2024. A scoping review exploring how adults self-describe and communicate about the listening difficulties they experience. International Journal of Audiology 63(3):163–170.

Moberly, A. C., T. McRackan, and T. N. Tatami. 2023. Expanding real-world outcomes in adults with hearing loss. https://bulletin.entnet.org/clinical-patient-care/article/22873582/expanding-realworld-outcomes-in-adults-with-hearing-loss (accessed December 19, 2024).

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2023. Achieving whole health: A new approach for veterans and the nation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey). 2021. 2017-March 2020 data documentation, codebook, and frequencies. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2017-2018/P_AUQ.htm (accessed June 16, 2024).

Powers, T. A. 2020. MarkeTrak 10: Patients, providers, products, and possibilities. Guest editor Thomas A Powers, Ph.D. Seminars in Hearing 41(1).

Powers, T. A., and N. Bisgaard. 2022. MarkeTrak and EuroTrak: What we can learn by looking beyond the U.S. market. Seminars in Hearing 43(4):348–356.

PQM (Partnership for Quality Measurement). 2023. Endorsement and maintenance (E&M) guidebook. https://p4qm.org/sites/default/files/2023-10/Del-3-6-Endorsement-and-MaintenanceGuidebook-Final_0.pdf#page=40 (accessed June 26, 2024).

PQM. 2024. Endorsement & maintenance (E&M). https://p4qm.org/EM (accessed June 26, 2024).

Tyler, R. S., L. J. Baker, and G. Armstrong-Bednall. 1983. Difficulties experienced by hearing-aid candidates and hearing-aid users. British Journal of Audiology 17(3):191–201.

Tysome, J. R., P. Hill-Feltham, W. E. Hodgetts, B. J. McKinnon, P. Monksfield, R. Sockalingham, M. L. Johansson, and A. F. Snik. 2015. The Auditory Rehabilitation Outcomes Network: An international initiative to develop core sets of patient-centred outcome measures to assess interventions for hearing loss. Clinical Otolaryngology 40(6):512–515.

Uchida, Y., T. Nakashima, F. Ando, N. Niino, and H. Shimokata. 2003. Prevalence of self-perceived auditory problems and their relation to audiometric thresholds in a middle-aged to elderly population. Acta Oto-Laryngologica 123(5):618–626.

Velentgas, P., N. A. Dreyer, and A. W. Wu. 2013. Outcome definition and measurement. In Developing a protocol for observational comparative effectiveness research: A user’s guide. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

von Gablenz, P., F. Otto-Sobotka, and I. Holube. 2018. Adjusting expectations: Hearing abilities in a population-based sample using an SSQ short form. Trends in Hearing 22:2331216518784837.

Wang, X., Y. Zheng, G. Li, J. Lu, and Y. Yin. 2022. Objective and subjective outcomes in patients with hearing aids: A cross-sectional, comparative, associational study. Audiology and Neurotology 27(2):166–174.

Warren, C. D., E. Nel, and P. J. Boyd. 2019. Controlled comparative clinical trial of hearing benefit outcomes for users of the Cochlear Nucleus 7 Sound Processor with mobile connectivity. Cochlear Implants International 20(3):116–126.

Whitmer, W. M., P. Howell, and M. A. Akeroyd. 2014. Proposed norms for the Glasgow Hearing-Aid Benefit Profile (GHABP) questionnaire. International Journal of Audiology 53(5):345–351.

This page intentionally left blank.