Measuring Meaningful Outcomes for Adult Hearing Health Interventions (2025)

Chapter: 2 Contextual Background of Adult Hearing Health Care

2

Contextual Background of Adult Hearing Health Care

As noted in Chapter 1, hearing loss is “the most prevalent sensory disorder in the United States” (Haile et al., 2024, p. 261). Many adults remain unaware of mild hearing loss because it occurs slowly over the course of years and it often remains unnoticed by the individual and undiagnosed (Contrera et al., 2016). Another reason for delays in hearing health care is the psychological resistance to admitting difficulty with hearing (Gates and Mills, 2005). Family members and friends often are the first to notice a hearing loss. Alternatively, older adults may view hearing difficulties as an inevitable rite of passage associated with aging, which deemphasizes the importance of seeking care. On the other hand, adults who seek interventions may have challenges accessing care (e.g., physical health, cost, access) (NASEM, 2016). Today, hearing cannot be fully restored, but a variety of interventions can improve communication, social engagement, and the ability to carry out daily activities. This chapter provides an overview of the prevalence and severity of hearing loss and hearing difficulties, the different etiologies of hearing loss, a variety of disparities in both the prevalence and severity of hearing loss, the different types of interventions, and the settings for evaluating the effectiveness of these interventions.

PREVALENCE AND SEVERITY OF HEARING LOSS AND HEARING DIFFICULTIES

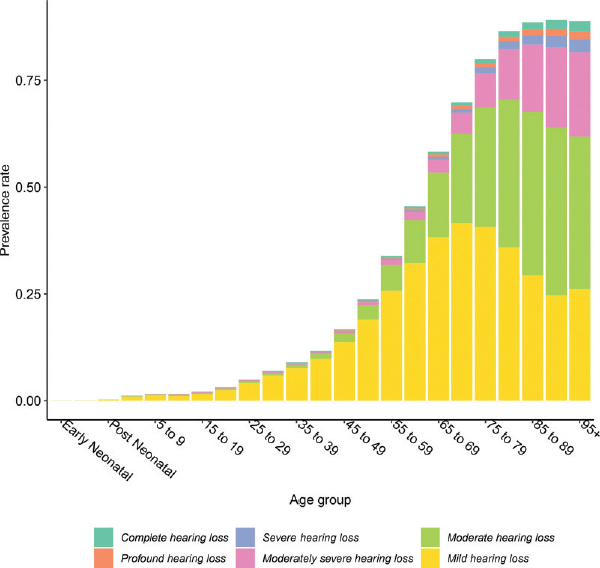

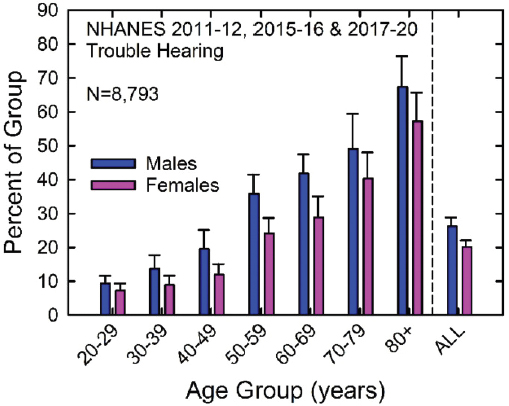

As shown in Figure 2-1, both the prevalence and severity of hearing loss increase with age (Haile et al., 2024). Similarly, as shown in Figure 2-2, the prevalence of self-reported trouble hearing also increases with age (Dillard et al., 2024; Humes, 2023a,b, 2024).

SOURCE: Haile et al., 2024. CC BY.

NOTE: NHANES = National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

SOURCE: Humes, 2023a. CC-BY-NC.

While approximately 22 percent of the U.S. population overall has hearing loss (Haile et al., 2024), 83 percent of individuals with hearing loss are over age 50 (Haile et al., 2024), and about 65 percent of adults over age 70 experience hearing loss (Reed et al., 2023). About one-quarter of adults report trouble hearing (Humes, 2023a). Additionally, some adults experiencing hearing difficulties do not demonstrate measurable hearing loss when tested. For example, as noted by Grant and colleagues (2021) in their examination of functional hearing and communication deficits, “recent studies suggest that some blast-exposed patients with normal to near-normal-hearing thresholds not only have an awareness of increased hearing difficulties, but also poor performance on various auditory tasks (sound source localization, speech recognition in noise, binaural integration, gap detection in noise, etc.)” (p. 1615). Estimates of the number of individuals who experience hearing difficulties in the absence of measurable hearing loss vary widely in the literature, in part due to differences in the definition of “normal audiometric threshold” as well as differences in the study population (Grant et al., 2021; Parthasarathy et al., 2020; Spankovich, et al., 2018; Tremblay et al., 2015).

ETIOLOGY OF HEARING LOSS

Hearing loss can be classified as mild, moderate, severe, profound, or complete (Haile et al., 2024). Approximately 64 percent of all cases of hearing loss are mild (where one has difficulty understanding speech in noise), and about 25 percent are moderate (where one has difficulty hearing and understanding in noise and sometimes in quiet or on the phone) (Haile et al., 2024). Furthermore, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey asks adults (aged 20 and older) about their perceived hearing condition; data from recent surveys show that about 76 percent of respondents described their hearing as excellent or good, and 21 percent said they had “a little” to “moderate” trouble (Humes, 2024).

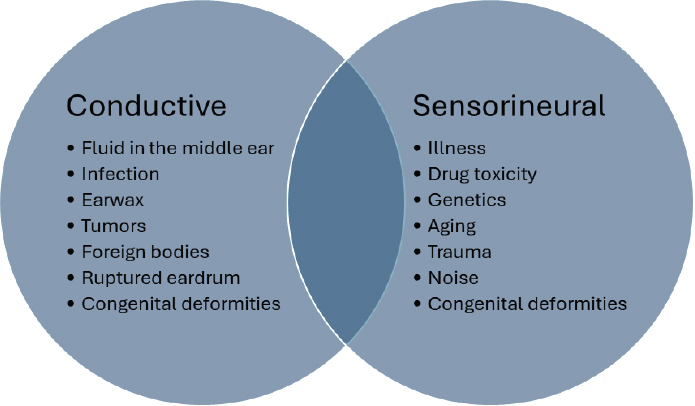

The three basic types of hearing loss are conductive, sensorineural, and mixed hearing loss, a combination of conductive and sensorineural hearing loss in the same ear (see Figure 2-3; ASHA, n.d. a,b,c; CDC, 2024). Conductive hearing loss is when sound energy is decreased when passing through the outer and/or middle ear on its way to the inner ear (Anastasiadou and Al Khalili, 2023; CDC, 2024). Causes of conductive hearing loss include fluid in the middle ear (due to colds or allergies), infection, earwax, tumors, foreign bodies, or congenital deformities (ASHA, n.d. a). Sensorineural hearing loss, the most prevalent type of permanent hearing loss, reflects difficulty in transforming the sound energy into neural electrical energy at the cochlea or cochlear nerve, owing to deterioration of the cochlear hair cells or nerve. Sensorineural hearing loss both diminishes and distorts the

SOURCES: ASHA, n.d. a,b,c; Cleveland Clinic, 2023.

sensory encoding of sound (Anastasiadou and Al Khalili, 2023). Causes of sensorineural hearing loss include illness (e.g., viral infections, high blood pressure, stroke, diabetes), drug toxicity, genetics, aging, trauma, noise, and congenital deformities (ASHA, n.d. c; Cleveland Clinic, 2023). Mixed hearing loss is a combination of both conductive and sensorineural hearing loss occurring simultaneously in the same ear (ASHA, n.d. b). Hearing loss can occur unilaterally, meaning it is only in one ear, or bilaterally (i.e., in both ears) (CDC, 2024). Hearing loss can also be symmetrical (same degree and configuration of hearing loss in both ears), or asymmetrical (the amount of loss is different between ears).

The most common causes of hearing loss are age; exposures to noise, ototoxic drugs, or chemicals; and genetics (Cunningham and Tucci, 2017, p. 3). The etiologies of hearing loss are explained in more detail below.

Age-Related Hearing Loss

Adult-onset hearing loss is primarily attributable to “the effects of aging on the auditory system,” which include “not only the degenerative effects of aging on the cochlea but also by the accumulated effects of exposure to noise and ototoxic drugs” (Cunningham and Tucci, 2017, p. 3). Age-related hearing loss begins in early adulthood and progresses gradually (Gates and Mills, 2005). A range of risk factors exacerbate age-related hearing loss including “biological age, gender, ethnicity, environment, lifestyle health comorbidities, and genetic predisposition” (Bowl and Dawson, 2019, p. 2).

The effects of aging (and other exposures) affect the cochlea, particularly the hair cells and the stria vascularis, and frequently result in significant and irreversible hearing loss (Cunningham and Tucci, 2017).

Some common characteristics of age-related hearing loss include progressive bilateral hearing loss, inability to hear sounds at high frequencies, and challenges understanding speech, especially in noise (Cunningham and Tucci, 2017). In addition to hair cell pathology resulting in sensorineural hearing loss, age-related pathology of synapses and the ascending neural pathway has been shown in mouse models (Sergeyenko et al., 2013) and human temporal bones (Viana et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2021). While synaptic and afferent loss are difficult to distinguish in humans, some evidence suggests potential associations between age-related damage to the afferent neural pathway and speech-in-noise declines (Johannesen et al., 2019). Listening difficulties in complex listening situations (particularly in a noisy environment) are a common patient complaint and can occur with or without audiometric hearing loss.

Noise-Induced Hearing Loss

Medicine has long been aware of noise-induced hearing loss (Hawkins and Schacht, 2005). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that the prevalence of noise-induced hearing loss among adults in the United States is 24 percent (Carroll et al., 2017). Noise-induced hearing loss can be unilateral or bilateral (Natarajan et al., 2023). Transient or moderate exposure can cause temporary hearing loss that will return to baseline thresholds in hours or several days at most (Ding et al., 2019). Long-term and or high-dose noise exposure causes permanent irreparable hearing loss (Ding et al., 2019). Continual exposure to intense noise destroys the hair cells in the inner ear, which detect vibrations and amplify sounds (Ding et al., 2019). Hair cells are not able to regenerate; this damage is permanent. Noise exposure occurs in everyday life such as loud music, movie theaters, vehicles, and power tools and in occupational environments such as factories, utilities (e.g., power generation, natural gas distribution, sewer treatment systems), forestry, bars and nightclubs, and sporting events (Cunningham and Tucci, 2017; Masterson and Themann, 2024; NIOSH, 2024; Themann and Masterson, 2019).

In addition to hair cell pathology resulting in sensorineural hearing loss, noise-induced pathology of synapses and the ascending neural pathway has been shown in mouse models (Kujawa and Liberman, 2009). There is significant interest in where the risk of noise-induced synaptic pathology begins in humans (Bramhall et al., 2019; Dobie and Humes, 2017) and the National Occupational Research Agenda (NORA) for Hearing Loss Prevention includes a call for research investigating suprathreshold deficits

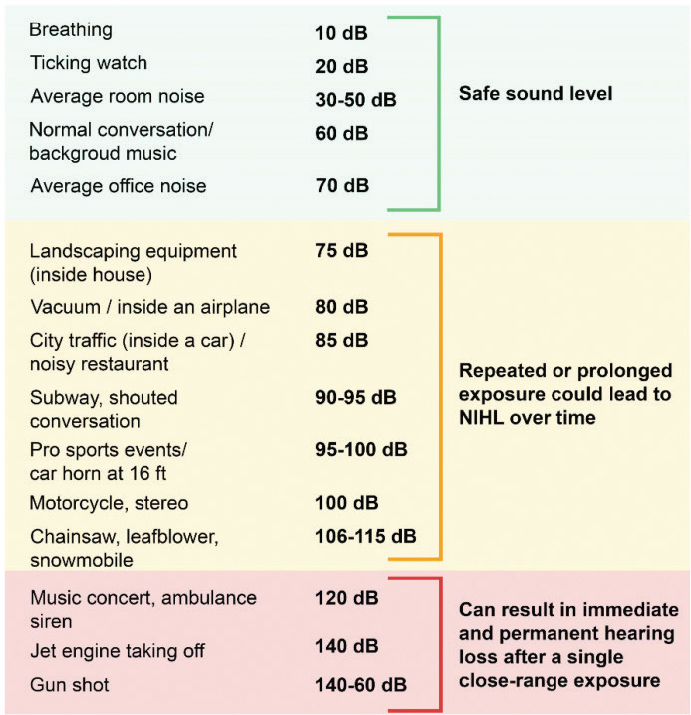

as a consequence of noise exposure and possible noise-induced pathology including both noise-induced synaptic pathology and outer hair cell loss (NORA, 2019). Recent noise exposure can cause deficits in the understanding of speech in noise in the absence of changes in the audiogram (Grinn et al., 2017), and a history of noise exposure is associated with poorer performance on speech-in-noise tests (for review see Le Prell and Clavier, 2017). Figure 2-4 demonstrates examples of safe and unsafe levels of noise in occupational and nonoccupational settings (Natarajan et al., 2023).

Drug-Induced Hearing Loss

Ototoxic medications that treat cancer, serious infections, and heart disease can damage the ear and cause hearing loss (Campo et al., 2013; Cone

NOTE: NIHL = noise-induced hearing loss.

SOURCE: Natarajan et al., 2023. CC BY 4.0.

et al., n.d.; Schacht et al., 2012). Approximately one million individuals are exposed to platinum-based cancer treatments annually resulting in a global burden of about 500,000 cases of hearing loss every year (Dillard et al., 2022). For example, cisplatin, which is used commonly to treat many types of cancer, is held in the inner ear for months to years after administration where it kills certain types of cells essential for hearing (Lee et al., 2024). Another class of ototoxic drugs are aminoglycoside antibiotics used for the treatment of gram-negative bacterial infections killing cochlear hair cells impairing high-frequency hearing (Lee et al., 2024). Loop diuretics used to treat high blood pressure and congestive heart failure (e.g., ethacrynic acid, furosemide, and bumetanide) can cause temporary hearing loss during treatment (Ding et al., 2002; Forge, 1982; Martínez-Rodríguez et al., 2007). When diuretics are prescribed with other ototoxic drugs, the damage to the ear is multiplied and results in worsening the degree of hearing loss (Ding et al., 2002; Komune and Snow, 1981; Li et al., 2011).

Hearing Loss Attributable to Chemical Exposures

In addition to noise exposure, workers in some industries also are exposed to ototoxic chemicals that can cause hearing loss (Campo et al., 2013). Industries that may have workers at risk of environmental exposure to such chemicals include “printing, painting, boat building, construction, glue manufacturing, metal products, chemicals, petroleum, leather products, furniture making, agriculture, and mining” (Campo et al., 2013, p. 5). The risk for workers in these industries comes primarily from exposure to aromatic solvents, which are vital ingredients in “adhesives, paints, lacquers, varnishes, printing inks, degreasers, fuel additives, glues, and thinners. . .plastics, rubber articles, and glass fibers” (Campo et al., 2013, p. 5). Firefighters also are at high risk of exposure because of the inhalation of smoke from burning toxic items like lead paint, batteries, and pressure-treated wood (Campo et al., 2013). Ototoxic chemicals primarily poison the hair cells or may damage other elements of the organ of Corti, which is essential for transmitting auditory signals (Campo et al., 2013). Growing evidence suggests that noise exposure compounds these chemicals’ toxic effects, furthering the damage, which is a significant concern since both exposures are often present in the same environment.

Genetic Hearing Loss

In addition to age and environmental exposures, genetics also influence age-related hearing loss (WHO, 2021). About half of the cases of early-onset hearing loss have a genetic etiology, but the extent to which genetics influence adult hearing loss is under researched (Penn Medicine, n.d.). Current research estimates that adult-onset hearing loss is 25 to 55 percent

hereditary resulting from mutation of genes that are required for hearing (Cunningham and Tucci, 2017). Preliminary research has been done on what genes may predispose someone to noise-induced or age-related hearing loss, but additional research is needed to fully understand to what extent one’s genetics predisposes hearing loss (Penn Medicine, n.d.).

Idiopathic Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss

Idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss is typically a unilateral, sensorineural hearing loss that occurs within a 72-hour period (Rauch, 2008). Recovery correlates to the severity of the hearing loss. People with mild hearing loss are likely to recover fully. People with moderate hearing loss often recover some but will not fully recover. People with severe hearing loss rarely recover fully (Rauch, 2008). Sudden sensorineural hearing loss may be attributable to an array of causes including Meniere’s disease, trauma, autoimmune disease, syphilis, Lyme disease, and perilymphatic fistula (Rauch, 2008). It also can occur because of a spinal tap or an intracranial surgery. In most cases, the sudden sensorineural hearing loss is termed idiopathic as the cause is not known. Steroid treatment is generally considered to be the standard of care even though the scientific evidence for its efficacy is insufficient (Chandrasekhar et al., 2019; Marx et al., 2018).

DISPARITIES IN HEARING LOSS

A variety of factors contribute to disparities in hearing loss demographics as well as access to hearing health care. Several of these factors are described below.

Demographics

The prevalence of age-related hearing loss varies by race and sex. After adjusting for all demographic variables, White individuals report the highest rates of hearing loss (Lin et al., 2012; Humes 2023a, 2024). Generally, the factors identified for hearing loss also have emerged from analyses of national data on perceived hearing difficulties (Humes, 2023a,b). One explanation for the racial disparity in hearing loss is that higher levels of melanin may exist in the cochlea of Black individuals and melanin may decrease the risk of hearing loss (Lin et al., 2012). Both the rates of self-reported hearing difficulties (see Figure 2-2) and prevalence of hearing impairment are higher for men than women (Hoffman et al., 2017; Humes, 2023a,b, 2024). This is likely at least partially because of differences in

noise exposure (Daniel, 2007; Helzner et al., 2005). Additionally, the hormone estrogen is protective against hearing loss, reducing risk, which can be a protective factor for women (Delhez et al., 2020; Reavis et al., 2023).

Access to Hearing Health Care

In addition to disparities in the prevalence of hearing loss itself, access to diagnostics and treatment for hearing loss is unequal among older adults in the United States. Disparities exist in both cost and insurance coverage. Prescription hearing aids cost about $2,700 per ear (Currie, 2025). Standard Medicaid programs are not required to cover hearing aids; therefore, coverage varies by state. In 2017, 28 states offered Medicaid coverage for “hearing aid assessment and associated services for adult beneficiaries meeting the inclusion criteria” (Arnold et al., 2017, p. 1479). The inclusion criteria also vary by state. Medicare Part B covers diagnostic evaluations only if the assessment is ordered by a physician and will not cover “hearing aids or examination for the purpose of prescribing, fitting, or changing hearing aids” (Center for Medicare Advocacy, 2024). If coverage is offered, it will be through Medicare Part C (also referred to as Medicare Advantage); this coverage is optional supplementary insurance that comes at additional costs (Malcolm et al., 2022). Hearing aids may be covered to some extent by a Medicare Advantage plan, but again this is not a requirement (Currie, 2025). In 2024, the European Federation of Hard of Hearing People (EFHOH), the European Association of Hearing Aid Professionals (AEA), and the European Hearing Instrument Manufacturers Association (EHIMA) collaborated publishing Getting the Numbers Right on Hearing Loss Hearing Care and Hearing Aid Use in Europe (Laureyns et al., 2024). The report found that “in countries where reimbursement is around 20 percent of the total cost, the uptake is 19 percent, but when reimbursement is around 50 percent, the uptake is 27 percent. When reimbursement is around 80 percent, the uptake increases to 41 percent, and when hearing aids are free of charge, uptake is 49 percent” (p. 8). These data show that when hearing aids are partially or even fully covered by insurance the uptake is still low.

As noted in the 2014 Institute of Medicine (IOM) and National Research Council (NRC) workshop summary Hearing Loss and Healthy Aging:

Among nonadopters, cost is cited as the primary reason for not getting a hearing aid. Two-thirds of these people said that they would get a hearing aid if insurance or other programs provided 100 percent coverage, and 47 percent said they were likely to get a hearing aid if the price did not exceed $500. “Beyond the purchase of a home or a car, hearing aids and services can be the third most expensive purchase for many Americans with hearing loss over time.” (pp. 78–79)

Beyond expenses, adults living in rural areas are more likely to experience delays in accessing hearing care (including hearing aids) because of the distance and availability of specialists (Chan et al., 2017). Chan and colleagues (2017) found that rural residents reported an average of 10.9 years between hearing loss onset and receiving a hearing aid compared to urban/suburban residents who reported an average of 7.9 years. A qualitative study of adults ages 50 to 78 living in Appalachian Kentucky reported that participants were frequently exposed to loud sounds like lawn mowers, hunting guns, and heavy power tools putting them at high risk of developing hearing difficulties (Powell et al., 2019). The participants in this study voiced concerns about the consequences of hearing loss like not being able to hear a fire alarm, not being able to speak on the phone, not hearing grandchildren, and impaired job performance (Powell et al., 2019).

Not only is the access to both primary care and hearing health care services more limited in remote settings, but more people in rural communities rely on Medicaid coverage making the cost of hearing aids unaffordable (Powell et al., 2019). One of the challenges for hearing health care access is awareness of hearing health and hearing health literacy among primary care providers who are often the first point of contact and source of referrals for hearing health care (Sydlowski et al., 2022).

CLASSES OF NONSURGICAL INTERVENTIONS

Several approaches to treating hearing loss exist, and the choice of intervention may depend on the etiology of the individual’s hearing loss and their goals. The main categories of interventions include devices, rehabilitation and training strategies, and investigative pharmaceuticals and biological therapies. As delineated in the statement of task for this study, surgically implanted devices (e.g., cochlear implants, bone-anchored hearing aids) are not considered here.

Devices

Several devices have been developed for adults with hearing difficulties including assistive listening devices, prescription hearing aids, and over-the-counter hearing aids.

Assistive Listening Devices

Assistive listening devices are electroacoustic devices that are alternative or supplemental to the use of hearing aids. These devices may be used at the level of the individual (e.g., personal sound amplification devices

and software) or at the systems level (e.g., hearing loops).1 A systematic review of the effectiveness of these devices in adults identified 11 studies, but the overall conclusion was that high-quality evidence regarding the effectiveness of assistive listening devices was not available (Maidment et al., 2018). None of these studies included any of the outcome measures recommended in this study (see Chapter 6).

Prescription Hearing Aids

Prescription hearing aids are small electronic devices worn in or behind the ear that deliver amplified sound, tailored to the level of severity of the hearing loss (NIH, 2022). Although hearing aids cannot restore hearing fully, they improve hearing and speech comprehension for individuals with hearing loss. An audiologist or hearing instrument specialist fits and programs the device for the individual with hearing difficulties. They can program the hearing aid to provide amplification differentially based on frequency and input level to customize the device to an individual’s hearing profile. The hearing aid wearer may be able to switch between different settings set by the provider for different listening environments.

Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids

In addition to prescription hearing aids, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a new category for over-the-counter hearing aids (NIDCD, 2022). The passage of the Over-the-Counter Hearing Aid Act of 2017 sought to improve access to hearing aids for individuals with perceived mild to moderate hearing loss.2 Over-the-counter hearing aids are not suitable for individuals with severe hearing loss or for children (NIDCD, 2022). Although over-the-counter hearing aids may offer a more affordable intervention for treating hearing difficulties in adults who perceive mild to moderate challenges, these hearing aids still may remain unaffordable for many individuals with low socioeconomic status (Malcolm et al., 2022). Notably, as of 2024, software that renders existing amplification hardware (e.g., earbuds) as meeting the criteria for over-the-counter hearing aids has been approved by the FDA (FDA, 2024).

___________________

1 A hearing loop is an assistive listening system placed in a public setting that helps transmit sound directly from a microphone into hearing aids (equipped with telecoils) and cochlear implants. This system “can make speech and music in public places more understandable” (HLAA, 2025).

2 Congress.gov. Over-the-Counter Hearing Aid Act of 2017, S. 670, 115th Cong., 1st sess., https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/670.

Perceived Benefit and Potential Adverse Effects of Hearing Aids

Research on hearing interventions typically focuses on their efficacy (measured in carefully controlled conditions) or effectiveness (measured in real-world settings). While most hearing aid wearers receive some benefit from hearing aids, the nonuse of hearing aids (among those with hearing aids) is primarily attributable to limited perceived benefit or dissatisfaction with the device (such as discomfort) (Franks and Timmer, 2023; Kochkin, 2000; McCormack and Fortnum, 2013). There is some limited evidence that the use of hearing aids that fit poorly may have adverse effects such as blisters, headaches, dizziness, and problems with chewing and swallowing (Kochkin, 2000; Manchaiah et al., 2019; McCormack and Fortnum, 2013).

Rehabilitation and Education

Other forms of hearing intervention may not involve a device. Specifically, aural rehabilitation is a common intervention that is most often used in addition to fitted devices to help individuals explore treatment options and learn how to communicate better and supports them through the adjustment to their device (Boothroyd, 2007; Pratt, 2005). Boothroyd (2007) defined aural rehabilitation as “the reduction of hearing-loss-induced deficits of function, activity, participation, and quality of life through sensory management, instruction, perceptual training, and counseling” (p. 63). Aural rehabilitation includes a wide range of activities including auditory training, assistive listening devices, communication strategies, relaxation techniques, and support groups (Hearing Speech + Deaf Center, n.d.). A systematic review of auditory training found a general lack of strong evidence supporting its effectiveness in adults with mild to moderate hearing loss (Henshaw and Ferguson, 2013). Three active-control randomized controlled trials conducted since that systematic review also failed to establish the effectiveness of this intervention, especially in the context of generalizing task-specific learning to improvements in everyday hearing function (Henshaw et al., 2022; Humes et al., 2019; Saunders et al., 2016).

Interventions based on education involving information about their hearing aids and the use of communication strategies, as well as general hearing-related counseling, have also been studied frequently. However, these studies typically involve instructional intervention included as a supplement to hearing aid use (i.e., not as a stand-alone intervention). Some studies show statistically significant benefits of the instructional intervention, but the effects are generally small compared to the effects of hearing-aids alone (Abrams et al., 1992; Brännström et al., 2016; Kricos and Holmes,

1996; Malmberg et al., 2017, 2023; Molander et al., 2018; Preminger, 2003; Preminger and Ziegler, 2008; Preminger and Yoo, 2010; Sweetow and Sabes, 2006; Thorén et al., 2014). Other studies have not demonstrated statistically significant effects of the instructional intervention (Ferguson et al., 2016; Kricos et al., 1992 Saunders et al., 2016).

Pharmaceutical and Biological Therapies

Currently the FDA has not approved any pharmaceutical or biological therapies to treat hearing loss, but regenerative strategies for improving hearing loss are being investigated (Ajay et al., 2022; Lewis, 2021). In addition to treatment of hearing loss, there is significant interest in therapies for hearing loss prevention, tinnitus, and balance disorders. As of 2019, there were 43 biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies working on therapeutics for inner ear and central ear disorders including drug, cell, and gene-based treatments (Schilder et al., 2019). As of 2021, there were 23 assets in clinical trials and 56 in preclinical development (Isherwood et al., 2022). One of the major challenges is that preclinical study designs lack standardization, which limits the ability to assess the comparative efficacy of potential treatments (Le Prell, 2023). Clinical trials evaluating pharmaceutical interventions in human participants similarly lack standardization (Le Prell, 2021). In 2022, the FDA approved a proprietary sodium thiosulfate formulation (Pedmark) administered intravenously to reduce the risk of cisplatin ototoxicity in pediatric patients with localized non-metastatic solid tumors (Dhillon, 2023). As the first approved medicine for hearing loss prevention, it is a promising step forward.

Only three peer-reviewed papers from two companies are available on gene therapy for hereditary hearing loss in human patients (Lv et al., 2024; Qi et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2024). So far, all participants have been children with otoferlin (OTOF) mutations. At present, they all reported proximal outcomes like pure-tone audiograms, otoacoustic emissions, and auditory brainstem responses of various types in assessing the degree of restoration of hearing in these patients. Another report evaluating small-molecule therapy (CHIR99021+valproic acid) described improved speech intelligibility in a subset of the participants receiving the investigational agents with no improvements in any participants who received placebo (McLean et al., 2021). Like hearing aids and cochlear implants, gene-therapy approaches to treating hearing loss will and should follow a similar progression from proximal outcomes demonstrating the restoration of audibility to more distal outcome measures like speech understanding in quiet and in complex listening situations (see Chapter 5).

SETTINGS FOR OUTCOME MEASUREMENT

Evaluation of the effectiveness of hearing health interventions is done for various purposes and can take place in multiple settings including research and clinical care.

Research Settings

In addition to studies of the effect of interventions at the level of the individual, two specific settings for research include establishing efficacy and effectiveness in clinical trials and population-based research.

Establishing Efficacy and Effectiveness in Clinical Trials

A major research context for outcome measurement is in the establishment of efficacy and effectiveness of the intervention in clinical trials (Munro et al., 2021). Phase I trials are exploratory and aim to assess the safety and dosage of an intervention, including only a small number of healthy participants. Phase II trials estimate the efficacy of an intervention, including a small number of participants with the relevant health condition preliminarily. Efficacy is how well an intervention works in the ideal and controlled environment (Singal et al., 2014). Phase III trials measure efficacy with a larger study population (Munro et al., 2021). Study designs vary, but these trials compare people who receive the intervention to a control group who receive the current standard of care, or placebo when there is no standard of care. Then, Phase IV trials, which occur after drug approval, monitor for effectiveness and side effects in a large population over a long period.

Population Health Research

Outcome measurement for population-level research reflects “a population’s dynamic state of physical, mental, and social well-being” (Parrish, 2010, p. 1). Outcome measures in population health can be used to create summary statistics, assess the distribution of an outcome in a population, and measure a population’s overall health or well-being (Parrish, 2010). Summary statistics of health outcomes on a population level inform where additional research or policy changes may be necessary (Murray et al., 2002). Outcome measures in population health are also used to understand the distribution of health issues and shed light on health disparities (Murray et al., 2002). Understanding which subgroups are most affected by a particular health condition is necessary to appropriately target resources, interventions, and the potential harms and consequences of untreated hearing loss.

Population-level research is essential for suggesting a possible causal relationship (Cox and Wermuth, 2004; Hays and Peipert, 2021; Ling et al., 2023) and finding disease risk factors or predictors of treatment response. However, an inherent limitation of population-level research is transporting observational study risk estimates and clinical trial intervention effects to the individual level. Moreover, limited research exists on significant individual-level change associated with intervention in the hearing science and broader academic literature. An essential consideration in making recommendations for outcome measurement in clinical settings will be balancing the potential for individual-level change based off population-level evidence with other variables (e.g., patient-reported areas of concern, concordance of literature, proximal/distal outcome, characteristics of the intervention).

Clinical Settings

Clinical settings for outcome assessment include assessing patient response (in person), via telemedicine, and self-care.

Assessing Patient Response in Person

In the clinical setting, outcome measurement helps to assess the effect of an intervention on health and functioning and thereby inform the treatment plan. Behavioral measures may be used to objectively assess improvement in hearing difficulties, such as through various tests that assess an individual’s ability to understand speech in a noisy environment (Billings et al., 2023). Additionally, the effects of an intervention may be assessed through the perspective of patient experience (i.e., through the use of patient-reported measures). Technological advancements have made the implementation of patient-reported outcome measures efficient by administering the measure (typically a questionnaire) online in advance of an appointment or on tablets in the clinician’s office (Dobrozsi and Panepinto, 2015). By incorporating the patient’s perspective into clinical care, clinicians can better understand what is meaningful to the patient and tailor interventions and treatment plans (Dobrozsi and Panepinto, 2015).

Telemedicine

Telemedicine, the delivery of health care services from a distance, has been used for decades but drastically increased in popularity during and after the COVID-19 pandemic (Hyder and Razzak, 2020). One of the main benefits of telemedicine is that it increases access and reduces the cost of traveling to a clinic, particularly for individuals in rural areas (D’Onofrio and Zeng, 2022). There is growing interest in tablet, computer,

and smartphone-based audiometry, but the results may be compromised by the lack of a soundproof booth, which has been used to control background noise. Recent advances in both passive attenuation and active cancellation of noise as well as machine learning have alleviated this background noise issue to make tele-audiometry a reliable and accurate alternative to traditional audiometry for “air conduction, bone conduction, and contralateral masking” (D’Onofrio and Zeng, 2022, p. 4). Additionally, satisfaction with hearing aids with remote fitting and verification is comparable to traditional practices. Alternatives to remote or in-situ pure-tone audiometry include such tests as the digits-in-noise test (De Sousa et al., 2020; Smits et al., 2004) that use stimuli less vulnerable to the presence of background noise during testing yet are strongly correlated to the pure-tone test results. Patient-reported outcome measures are essential for measuring the effects of an intervention in the telemedicine setting (Mercadal-Orfila et al., 2024).

The availability of electronic versions of self-report outcome measurements means that patients can complete the questionnaire at home or anywhere with internet (Gibson and Pincus, 2021). A noninferiority trial of Veterans Administration patients evaluating hearing health outcomes (measured by the International Outcome Inventory for Hearing Aids) found that both teleaudiology and in-person audiology care were highly effective and found no clinically meaningful difference between the care delivery models (Pross et al., 2016). A single-blinded randomized controlled trial of 56 adults found that teleaudiology follow-up appointments “were of similar effectiveness” to in-person appointments (Teleaudiology Today, 2021). Telehealth has significant usefulness in a variety of hearing health care contexts, including not only use in noise and ototoxic exposure monitoring, but also expansion of access for patients and participants in rural and low-resource settings, and facilitating the evaluation of auditory outcomes in large-scale clinical trials (Robler et al., 2022). Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) is an alternative measurement technique that samples “subjects’ current behaviors and experiences in real time, in subjects’ natural environments” (Shiffman et al., 2008, p.1). EMA reduces recall bias and improves ecological validity, but they are time intensive for clinicians, researchers, and patients.

Self-Care

Over-the-counter hearing aids created a new setting in the hearing health world, which is self-care. The World Health Organization defines self-care as “the ability of individuals, families, and communities to promote and maintain their health, prevent disease, and cope with illness with or without the support of a health or care worker” (WHO, 2024). For hearing, this has been framed recently in the concept of “auditory wellness” (Humes, 2021; Humes et al., 2024). This care can range from administering medicines and

diagnostics to intervening with devices and using digital tools. Consumers who purchase hearing aids over the counter will typically fit the devices themselves without the assistance of a hearing health professional. Instead of audiologists or hearing aid specialists, some consumers will rely on support and information from primary care clinicians and pharmacists (Berenbrok et al., 2021; Davis et al., 2025).

Adults with hearing difficulties who pursue over-the-counter hearing aids will usually not receive a traditional audiogram and will also not likely undergo formal outcome assessment. However, adults with hearing loss may be able to accurately administer some self-report outcome measures themselves. A framework for self-assessment of hearing difficulties, self-assessment of outcomes, and self-management of auditory wellness has been described recently (Humes et al., 2024). Such self-management has the potential to broaden the accessibility to hearing health care considerably.

FINDINGS

Finding 2-1: The prevalence and severity of both audiometric hearing loss and self-reported hearing difficulties increase with age.

Finding 2-2: Hearing loss and self-reported hearing difficulties affect approximately 1 in every 5 adults and about two-thirds of adults aged 70 and older.

Finding 2-3: Two-thirds of hearing loss cases are in adults over the age of 50.

Finding 2-4: The most common etiology of hearing loss is from the degenerative effects of aging, followed by noise exposure.

Finding 2-5: Currently, there are no cures for age-related or noise-induced hearing loss, but there are treatments that improve communication and mitigate many of the social and emotional consequences of hearing difficulties. Few people experience adverse side effects of treatment.

Finding 2-6: Outcomes of hearing health interventions may be assessed in a variety of settings and for a range of purposes.

REFERENCES

Abrams, H. B., T. Hnath-Chisolm, S. M. Guerreiro, and S. I. Ritterman. 1992. The effects of intervention strategy on self-perception of hearing handicap. Ear and Hearing 13(5):371–377.

Ajay, E., N. Gunewardene, and R. Richardson. 2022. Emerging therapies for human hearing loss. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy 22(6):689–705.

Anastasiadou, S., and Y. Al Khalili. 2023. Hearing loss. In Statpearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing

Arnold, M. L., K. Hyer, and T. Chisolm. 2017. Medicaid hearing aid coverage for older adult beneficiaries: A state-by-state comparison. Health Affairs 36(8):1476–1484.

ASHA (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association). n.d., a. Conductive hearing loss. https://www.asha.org/public/hearing/conductive-hearing-loss (accessed November 26, 2024).

ASHA. n.d., b. Mixed hearing loss. https://www.asha.org/public/hearing/mixed-hearing-loss (accessed November 26, 2024).

ASHA. n.d., c. Sensorineural hearing loss. https://www.asha.org/public/hearing/sensorineural-hearing-loss (accessed November 26, 2024).

Berenbrok, L. A., L. Ciemniecki, A. A. Cremeans, R. Albright, and E. Mormer. 2021. Pharmacist competencies for over-the-counter hearing aids: A Delphi study. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association 61(4):e255–e262.

Billings, C. J., T. M. Olsen, L. Charney, B. M. Madsen, and C. E. Holmes. 2023. Speech-in-noise testing: An introduction for audiologists. Seminars in Hearing 45(1). https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-1770155.

Boothroyd, A. 2007. Adult aural rehabilitation: What is it and does it work? Trends in Amplification 11(2):63–71.

Bowl, M. R., and S. J. Dawson. 2019. Age-related hearing loss. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 9(8):1–14.

Bramhall, N., E. F. Beach, B. Epp, C. G. Le Prell, E. A. Lopez-Poveda, C. J. Plack, R. Schaette, S. Verhulst, and B. Canlon. 2019. The search for noise-induced cochlear synaptopathy in humans: Mission impossible? Hearing Research 377:88–103.

Brännström, K. J., M. Öberg, E. Ingo, K. N. T. Månsson, G. Andersson, T. Lunner, and A. Laplante-Lévesque. 2016. The initial evaluation of an internet-based support system for audiologists and first-time hearing aid clients. Internet Interventions 4:82–91.

Campo, P., T. C. Morata, and O. Hong. 2013. Chemical exposure and hearing loss. Disease-a-Month 59(4):119–138.

Carroll, Y. I., J. Eichwald, F. Scinicariello, H. J. Hoffman, S. Deitchman, M. S. Radke, C. L. Themann, and P. Breysse. 2017. Vital signs: Noise-induced hearing loss among adults—United States 2011–2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 66(5):139–144.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2024. Types of hearing loss. https://www.cdc.gov/hearing-loss-children/about/types-of-hearing-loss.html (accessed September 18, 2024).

Center for Medicare Advocacy. 2024. Medicare coverage of hearing care and audiology services. https://medicareadvocacy.org/medicare-info/medicare-coverage-of-hearing-care-and-audiology-services (accessed October 4, 2024).

Chan, S., B. Hixon, M. Adkins, J. B. Shinn, and M. L. Bush. 2017. Rurality and determinants of hearing healthcare in adult hearing aid recipients. Laryngoscope 127(10):2362–2367.

Chandrasekhar, S. S., B. S. Tsai Do, S. R. Schwartz, L. J. Bontempo, E. A. Faucett, S. A. Fine-stone, D. B. Hollingsworth, D. M. Kelley, S. T. Kmucha, G. Moonis, G. L. Poling, J. K. Roberts, R. J. Stachler, D. M. Zeitler, M. D. Corrigan, L. C. Nnacheta, and L. Satterfield. 2019. Clinical practice guideline: Sudden hearing loss (update). Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 161(1_suppl):S1–S45.

Cleveland Clinic. 2023. Hearing loss. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/17673-hearing-loss (accessed January 3, 2025).

Cone, B., P. Dorn, D. Konrad-Martin, J. Lister, C. Ortiz, and K. Schairer. n.d. Ototoxic medications (medication effects). https://www.asha.org/public/hearing/ototoxic-medications (accessed November 16, 2023).

Contrera, K. J., M. I. Wallhagen, S. K. Mamo, E. S. Oh, and F. R. Lin. 2016. Hearing loss health care for older adults. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 29(3):394–403.

Cox, D. R., and N. Wermuth. 2004. Causality: A statistical view. International Statistical Review 72(3):285–305.

Cunningham, L. L., and D. L. Tucci. 2017. Hearing loss in adults. New England Journal of Medicine 377(25):2465–2473.

Currie, D. 2025. Does Medicare & insurance cover hearing aids in 2025? https://www.ncoa.org/adviser/hearing-aids/does-medicare-cover-hearing-aids (accessed January 11, 2025).

D’Onofrio, K. L., and F.-G. Zeng. 2022. Tele-audiology: Current state and future directions. Frontiers in Digital Health 3:788103.

Daniel, E. 2007. Noise and hearing loss: A review. Journal of School Health 77(5):225–231.

Davis, R. J., M. Lin, O. Ayo-Ajibola, D. D. Ahn, P. A. Brown, J. Parsons, T. F. Ho, and J. S. Choi. 2025. Over-the-counter hearing aids: A nationwide survey study to understand perspectives in primary care. Laryngoscope 135(1):299–307.

Delhez, A., P. Lefebvre, C. Péqueux, B. Malgrange, and L. Delacroix. 2020. Auditory function and dysfunction: Estrogen makes a difference. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 77(4):619–635.

De Sousa, K. C., D. W. Swanepoel, D. R. Moore, H. C. Myburgh, and C. Smits. 2020. Improving sensitivity of the digits-in-noise test using antiphasic stimuli. Ear and Hearing 41(2):442–450.

Dhillon, S. 2023. Sodium thiosulfate: Pediatric first approval. Paediatric Drugs 25(2):239–244.

Dillard, L. K., L. Lopez-Perez, R. X. Martinez, A. M. Fullerton, S. Chadha, and C. M. McMahon. 2022. Global burden of ototoxic hearing loss associated with platinum-based cancer treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiology 79:102203.

Dillard, L. K., L. J. Matthews, and J. R. Dubno. 2024. Prevalence of self-reported hearing difficulty on the Revised Hearing Handicap Inventory and associated factors. BMC Geriatrics 24(510). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-04901-w.

Ding, D., S. L. McFadden, J. M. Woo, and R. J. Salvi. 2002. Ethacrynic acid rapidly and selectively abolishes blood flow in vessels supplying the lateral wall of the cochlea. Hearing Research 173(1–2):1–9.

Ding, T., A. Yan, and K. Liu. 2019. What is noise-induced hearing loss? British Journal of Hospital Medicine 80(9):525–529.

Dobie, R. A., and L. E. Humes. 2017. Commentary on the regulatory implications of noise-induced cochlear neuropathy. International Journal of Audiology 56(Supl 1):74–78.

Dobrozsi, S., and J. Panepinto. 2015. Patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice. Hematology 2015(1):501–506.

Ferguson, M., M. Brandreth, W. Brassington, P. Leighton, and H. Wharrad. 2016. A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the benefits of a multimedia educational program for first-time hearing aid users. Ear and Hearing 37(2):123–136.

FDA (Food and Drug Administration). 2024. FDA authorizes first over-the-counter hearing aid software. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-authorizes-first-over-counter-hearing-aid-software (accessed Febuary 18, 2025).

Forge, A. 1982. A tubulo-cisternal endoplasmic reticulum system in the potassium transporting marginal cells of the stria vascularis and effects of the ototoxic diuretic ethacrynic acid. Cell and Tissue Research 226(2):375–387.

Franks, I., and B. H. B. Timmer. 2023. Reasons for the non-use of hearing aids: Perspectives of nonusers, past users, and family members. International Journal of Audiology 63(10):794–801.

Gates, G. A., and J. H. Mills. 2005. Presbycusis. Lancet 366(9491):1111–1120.

Gibson, K. A., and T. Pincus. 2021. A self-report multidimensional health assessment questionnaire (MDHAQ) for face-to-face or telemedicine encounters to assess clinical severity (RAPID3) and screen for fibromyalgia (FAST) and depression (DEP). Current Treatment Options in Rheumatology 7(3):161–181.

Grinn, S. K., K. B. Wiseman, J. A. Baker, and C. G. Le Prell. 2017. Hidden hearing loss? No effect of common recreational noise exposure on cochlear nerve response amplitude in humans. Frontiers in Neuroscience 11:465.

Grant, K. W., L. R., Kubli, S. A. Phatak, H. Galloza, and D. S. Brungart. 2021. Estimated prevalence of functional hearing difficulties in blast-exposed service members with normal to near-normal-hearing thresholds. Ear and Hearing 42(6):1615–1626.

Haile, L. M., A. U. Orji, K. M. Reavis, P. S. Briant, K. M. Lucas, F. Alahdab, T. W. Bärnighausen, A. W. Bell, C. Cao, X. Dai, S. I. Hay, G. Heidari, I. M. Karaye, T. R. Miller, A. H. Mokdad, E. Mostafavi, Z. S. Natto, S. Pawar, J. Rana, A. Seylani, J. A. Singh, J. Wei, L. Yang, K. L. Ong, and J. D. Steinmetz. 2024. Hearing loss prevalence, years lived with disability, and hearing aid use in the United States from 1990 to 2019: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease study. Ear and Hearing 45(1):257–267.

Hawkins, J. E., and J. Schacht. 2005. Sketches of otohistory part 10: Noise-induced hearing loss. Audiology and Neurotology 10(6):305–309.

Hays, R. D., and J. D. Peipert. 2021. Between-group minimally important change versus individual treatment responders. Quality of Life Research 30(10):2765–2772.

Hearing Speech + Deaf Center. n.d. What is aural rehabiliation. https://hearingspeechdeaf.org/what-is-aural-rehabilitation/#:~:text=How%20Does%20Aural%20Rehabilitation%20Work,can%20reduce%20feelings%20of%20isolation (accessed January 5, 2025).

Helzner, E. P., J. A. Cauley, S. R. Pratt, S. R. Wisniewski, J. M. Zmuda, E. O. Talbott, N. De Rekeneire, T. B. Harris, S. M. Rubin, and E. M. Simonsick. 2005. Race and sex differences in age-related hearing loss: The health, aging and body composition study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 53(12):2119–2127.

Henshaw, H., and M. A. Ferguson. 2013. Efficacy of individual computer-based auditory training for people with hearing loss: A systematic review of the evidence. PLoS One 8(5):e62836.

Henshaw, H., A. Heinrich, A. Tittle, and M. Ferguson. 2022. Cogmed training does not generalize to real-world benefits for adult hearing aid users: Results of a blinded, active-controlled randomized trial. Ear and Hearing 43(3):741–763.

HLAA (Hearing Loss Association of America). 2025. Hearing loop technology https://www.hearingloss.org/find-help/hearing-assistive-technology/hearing-loop-technology (accessed March 11, 2025).

Hoffman, H. J., R. A. Dobie, K. G. Losonczy, C. L. Themann, and G. A. Flamme. 2017. Declining prevalence of hearing loss in US adults aged 20 to 69 years. JAMA Otolaryngology – Head & Neck Surgery 143(3):274–285.

Humes, L. E. 2021. An approach to self-assessed auditory wellness in older adults. Ear and Hearing 42(4):745–761.

Humes, L. E. 2023a. U.S. population data on hearing loss, trouble hearing, and hearing-device use in adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-12, 2015-16, and 2017-20. Trends in Hearing 27. https://doi.org/10.1177/23312165231160978.

Humes, L. E. 2023b. U.S. population data on self-reported trouble hearing and hearing-aid use in adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2017-2018. Trends in Hearing 27. https://doi.org/10.1177/23312165231160967.

Humes, L. E. 2024. Demographic and audiological characteristics of candidates for over-the-counter hearing aids in the United States. Ear and Hearing 45(5):1296–1312.

Humes, L. E., K. G. Skinner, D. L. Kinney, S. E. Rogers, A. K. Main, and T. M. Quigley. 2019. Clinical effectiveness of an at-home auditory training program: A randomized controlled trial. Ear and Hearing 40(5):1043–1060.

Humes L. E., S. Dhar, V. Manchaiah, A. Sharma, T. H. Chisolm, M. L. Arnold, and V. A. Sanchez. 2024. A perspective on auditory wellness: What it is, why it is important, and how it can be managed. Trends in Hearing 28. https://doi.org/10.1177/23312165241273342.

Hyder, M. A., and J. Razzak. 2020. Telemedicine in the United States: An introduction for students and residents. Journal of Medical Internet Research 22(11):e20839.

IOM (Institute of Medicine) and NRC (National Research Council). 2014. Hearing loss and healthy aging: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Isherwood, B., A. C. Gonçalves, R. Cousins, and R. Holme. 2022. The global hearing therapeutic pipeline: 2021. Drug Discovery Today 27(3):912–922.

Johannesen, P. T., B. C. Buzo, and E. A. Lopez-Poveda. 2019. Evidence for age-related cochlear synaptopathy in humans unconnected to speech-in-noise intelligibility deficits. Hearing Research 374:35–48.

Kochkin, S. 2000. MarkeTrakV: “Why my hearing aids are in the drawer”: The consumers’ perspective. Hearing Journal 53(2):34–41.

Komune, S., and J. B. Snow, Jr. 1981. Potentiating effects of cisplatin and ethacrynic acid in ototoxicity. Archives of Otolaryngology 107(10):594–597.

Kricos, P. B., and A. E. Holmes. 1996. Efficacy of audiologic rehabilitation for older adults. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 7(4):219–229.

Kricos, P. B., A. E. Holmes, and D. A. Doyle. 1992. Efficacy of a communication training program for hearing-impaired elderly adults. Journal of the Aural Rehabilitation Association 24:69–80.

Kujawa, S. G., and M. C. Liberman. 2009. Adding insult to injury: Cochlear nerve degeneration after “temporary” noise-induced hearing loss. Journal of Neuroscience 29(45):14077–14085.

Laureyns, M., N. Bisgaard, L. Best, and S. Zimmer. 2024. Getting the numbers right on hearing loss hearing care and hearing aid use in Europe. https://www.ehima.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Getting-the-numbers-right-on-Hearing-Loss-Hearing-Care-and-Hearing-Aid-Use-in-Europe-2024.pdf (accessed March 11, 2025).

Lee, J., K. Fernandez, and L. L. Cunningham. 2024. Hear and now: Ongoing clinical trials to prevent drug-induced hearing loss. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology 64(1):211–230.

Le Prell, C. G. 2023. Preclinical prospects of investigational agents for hearing loss treatment. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs 32(8):685–692.

Le Prell, C. G. 2021. Investigational medicinal products for the inner ear: Review of clinical trial characteristics in clinicaltrials.gov. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 32(10):670–694.

Le Prell, C. G., and O. H. Clavier. 2017. Effects of noise on speech recognition: Challenges for communication by service members. Hearing Research 349:76–89.

Lewis, R. M. 2021. From bench to booth: Examining hair cell regeneration through an audiologist’s scope. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 32(10):654–660.

Li, Y., D. Ding, H. Jiang, Y. Fu, and R. Salvi. 2011. Co-administration of cisplatin and furosemide causes rapid and massive loss of cochlear hair cells in mice. Neurotoxicity Research 20:307–319.

Lin, F. R., P. Maas, W. Chien, J. P. Carey, L. Ferrucci, and R. Thorpe. 2012. Association of skin color, race/ethnicity, and hearing loss among adults in the USA. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology 13(1):109–117.

Ling, A. Y., M. E. Montez-Rath, P. Carita, K. J. Chandross, L. Lucats, Z. Meng, B. Sebastien, K. Kapphahn, and M. Desai. 2023. An overview of current methods for real-world applications to generalize or transport clinical trial findings to target populations of interest. Epidemiology 34(5):627–636.

Lv, J. H., X. Wang, Y. Cheng, D. Chen, L. Wang, Q. Zhang, Q. Cao, H. Tang, S. Hu, K. Gao, M. Xun, J. Wang, Z. Wang, B. Zhu, C. Cui, Z. Gao, L. Guo, S. Yu, L. Jiang, Y. Yin, J. Zhang, B. Chen, W. Wang, R. Chai, Z. Chen, H. Li, and Y. Shu. 2024. AAV1-hOTOF gene therapy for autosomal recessive deafness 9: A single-arm trial. Lancet 403(10441):2317–2325.

Maidment, D. W., A. B. Barker, J. Xia, and M. A. Ferguson. 2018. A systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the effectiveness of alternative listening devices to conventional hearing aids in adults with hearing loss. International Journal of Audiology 57(10):721–729.

Malcolm, K. A., J. J. Suen, and C. L. Nieman. 2022. Socioeconomic position and hearing loss: Current understanding and recent advances. Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery 30(5):351–357.

Malmberg, M., T. Lunner, K. Kähäri, and G. Andersson. 2017. Evaluating the short-term and long-term effects of an internet-based aural rehabilitation programme for hearing aid users in general clinical practice: A randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 7(5):e013047.

Malmberg, M., K. Anióse, J. Skans, and M. Öberg. 2023. A randomised, controlled trial of clinically implementing online hearing support. International Journal of Audiology 62(5):472–480.

Manchaiah, V., H. Abrams, A. Bailey, and G. Andersson. 2019. Negative side effects associated with hearing aid use in adults with hearing loss. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 30(6):472–481.

Martínez-Rodríguez, R., J. García Lorenzo, J. Bellido Peti, J. Palou Redorta, J. J. Gómez Ruiz, and H. Villavicencio Mavrich. 2007. [loop diuretics and ototoxicity]. Actas Urologicas Espanolas 31(10):1189–1192.

Marx, M., E. Younes, S. S. Chandrasekhar, J. Ito, S. Plontke, S. O’Leary, and O. Sterkers. 2018. International consensus (icon) on treatment of sudden sensorineural hearing loss. European Annals of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Diseases 135(1s):S23–S28.

Masterson, E. A., and C. L. Themann. 2024. Prevalence of hearing loss among noise-exposed US workers within the utilities sector, 2010-2019. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 66(8):648–653.

McCormack, A., and H. Fortnum. 2013. Why do people fitted with hearing aids not wear them? International Journal of Audiology 52(5):360–368.

McLean, W. J., A. S. Hinton, J. T. J. Herby, A. N. Salt, J. J. Hartsock, S. Wilson, D. L. Lucchino, T. Lenarz, A. Warnecke, N. Prenzler, H. Schmitt, S. King, L. E. Jackson, J. Rosenbloom, G. Atiee, M. Bear, C. L. Runge, R. H. Gifford, S. D. Rauch, D. J. Lee, R. Langer, J. M. Karp, C. Loose, and C. LeBel. 2021. Improved speech intelligibility in subjects with stable sensorineural hearing loss following intratympanic dosing of FX-322 in a phase 1b study. Otology and Neurotology 42(7):e849–e857.

Mercadal-Orfila, G., S. Herrera-Pérez, N. Piqué, F. Mateu-Amengual, P. Ventayol-Bosch, M. A. Maestre-Fullana, F. Fernández-Cortés, F. Barceló-Sansó, and S. Rios. 2024. Implementing systematic patient-reported measures for chronic conditions through the Naveta value-based telemedicine initiative: Observational retrospective multicenter study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth 12(1):e56196.

Molander, P., H. Hesser, S. Weineland, K. Bergwall, S. Buck, J. Jäder Malmlöf, H. Lantz, T. Lunner, and G. Andersson. 2018. Internet-based acceptance and commitment therapy for psychological distress experienced by people with hearing problems: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy 47(2):169–184.

Munro, K. J., W. M. Whitmer, and A. Heinrich. 2021. Clinical trials and outcome measures in adults with hearing loss. Frontiers in Psychology 12:733060.

Murray, C. J., J. A. Salomon, C. D. Mathers, and A. D. Lopez. 2002. Summary measures of population health: Concepts, ethics, measurement and applications. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2016. Hearing health care for adults: Priorities for improving access and affordability. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Natarajan, N., S. Batts, and K. M. Stankovic. 2023. Noise-induced hearing loss. Journal of Clinical Medicine 12(6):2347.

NIDCD (National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders). 2022. Over-the-counter hearing aids. https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/sites/default/files/Documents/order/over-the-counter-hearing-aids-2024.pdf (accessed September 18, 2024).

NIH (National Institutes of Health). 2022. Hearing aids. https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/hearing-aids#hearingaid_01 (accessed November 16, 2023).

NIOSH (National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health). 2024. Noise and hearing loss. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/noise/about/noise.html (accessed September 18, 2024).

NORA (National Occupational Research Agenda) Hearing Loss Prevention Cross-Sector Council. 2019. National Occupational Research Agenda for hearing loss prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nora/councils/hlp/pdfs/National_Occupational_Research_Agenda_for_HLP_July_2019-508.pdf (accessed January 8, 2025).

Parthasarathy, A., K. E. Hancock, K. Bennett, V. DeGruttola, and D. B. Polley. 2020. Bottom-up and top-down neural signatures of disordered multi-talker speech perception in adults with normal hearing. eLife 9. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.51419.

Parrish, R. G. 2010. Measuring population health outcomes. Preventing Chronic Disease 7(4):A71.

Penn Medicine. n.d. Genetic analysis at the new Penn Center for Adult-Onset Hearing Loss. https://www.pennmedicine.org/departments-and-centers/otorhinolaryngology/about-us/newsletters/archive/2020-newsletters/genetic-analysis-for-adult-onset-hearing-loss#:~:text=In%20early%2Donset%20hearing%20loss,is%20the%20only%20diagnostic%20feature (accessed November 16, 2023).

Powell, W., J. A. Jacobs, W. Noble, M. L. Bush, and C. Snell-Rood. 2019. Rural adult perspectives on impact of hearing loss and barriers to care. Journal of Community Health 44(4):668–674.

Pratt, S. 2005. Adult audiologic rehabilitation. https://www.asha.org/articles/adult-audiologic-rehabilitation/#:~:text=According%20to%20Raymond%20Hull%2C%20aural,include%20a%20program%20of%20auditory (accessed May 22, 2024).

Preminger, J. E. 2003. Should significant others be encouraged to join adult group audiologic rehabilitation classes? Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 14(10):545–555.

Preminger, J. E., and J. K. Yoo. 2010. Do group audiologic rehabilitation activities influence psychosocial outcomes? American Journal of Audiology 19(2):109–125.

Preminger, J. E., and C. H. Ziegler. 2008. Can auditory and visual speech perception be trained within a group setting? American Journal of Audiology 17(1):80–97.

Pross, S. E., A. L. Bourne, and S. W. Cheung. 2016. Teleaudiology in the Veterans Health Administration. Otology & Neurotology 37(7):847–850.

Qi, J., F. Tan, L. Zhang, L. Lu, S. Zhang, Y. Zhai, Y. Lu, X. Qian, W. Dong, Y. Zhou, Z. Zhang, X. Yang, L. Jiang, C. Yu, J. Liu, T. Chen, L. Qu, C. Tan, S. Sun, H. Song, Y. Shu, L. Xu, X. Gao, H. Li, and R. Chai. 2024. AAV-mediated gene therapy restores hearing in patients with DFNB9 deafness. Advanced Science 11(11):2306788.

Rauch, S. D. 2008. Idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. New England Journal of Medicine 359(8):833–840.

Reavis, K. M., N. Bisgaard, B. Canlon, J. R. Dubno, R. D. Frisina, R. Hertzano, L. E. Humes, P. Mick, N. A. Phillips, M. K. Pichora-Fuller, B. Shuster, and G. Singh. 2023. Sex-linked biology and gender-related research is essential to advancing hearing health. Ear and Hearing 44(1):10–27.

Reed, N. S., E. E. Garcia-Morales, C. Myers, A. R. Huang, J. R. Ehrlich, O. J. Killeen, J. E. Hoover-Fong, F. R. Lin, M. L. Arnold, E. S. Oh, J. A. Schrack, and J. A. Deal. 2023. Prevalence of hearing loss and hearing aid use among US Medicare beneficiaries aged 71 years and older. JAMA Network Open 6(7):e2326320–e2326320.

Robler, S. K., L. Coco, and M. Krumm. 2022. Telehealth solutions for assessing auditory outcomes related to noise and ototoxic exposures in clinic and research. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 152(3):1737–1754.

Saunders, G. H., S. L Smith, T. H. Chisolm, M. T. Frederick, R. A. McArdle, and R. H. Wilson. 2016. A randomized control trial: Supplementing hearing aid use with Listening and Communication Enhancement (LACE) auditory training. Ear and Hearing 37(4):381–396.

Schacht, J., A. E. Talaska, and L. P. Rybak. 2012. Cisplatin and aminoglycoside antibiotics: Hearing loss and its prevention. Anatomical Record 295:1837–1850.

Schilder, A. G. M., M. P. Su, H. Blackshaw, L. Lustig, H. Staecker, T. Lenarz, S. Safieddine, C. S. Gomes-Santos, R. Holme, and A. Warnecke. 2019. Hearing protection, restoration, and regeneration: An overview of emerging therapeutics for inner ear and central hearing disorders. Otology and Neurotology 40(5):559–570.

Sergeyenko, Y., K. Lall, M. C. Liberman, and S. G. Kujawa. 2013. Age-related cochlear synaptopathy: An early-onset contributor to auditory functional decline. Journal of Neuroscience 33(34):13686–13694.

Shiffman, S., A. A. Stone, and M. R. Hufford. 2008. Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 4(1):1–32.

Singal, A. G., P. D. Higgins, and A. K. Waljee. 2014. A primer on effectiveness and efficacy trials. Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology 5(1):e45.

Smits, C., T. S. Kapteyn, and T. Houtgast. 2004. Development and validation of an automatic speech-in-noise screening test by telephone. International Journal of Audiology 43(1):15–28.

Spankovich, C., V. B. Gonzalez, D. Su, and C. E. Bishop. 2018. Self reported hearing difficulty, tinnitus, and normal audiometric thresholds, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2002. Hearing Research 358:30–36.

Sweetow, R. W., and J. H. Sabes. 2006. The need for and development of an adaptive Listening and Communication Enhancement (LACE) program. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 17(8):538–558.

Sydlowski, S. A., J. P. Marinelli, C. M. Lohse, and M. L. Carlson. 2022. Hearing health perceptions and literacy among primary healthcare providers in the United States: A national cross-sectional survey. Otology and Neurotology 43(8):894–899.

Teleaudiology Today. 2021. Measuring teleaudiology quality, effectiveness for hearing aid follow-ups. Hearing Journal 74(1):22.

Themann, C. L., and E. A Masterson. 2019. Occupational noise exposure: A review of its effects, epidemiology, and impact with recommendations for reducing its burden. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 146(5):3879.

Thorén, E. S., M. Oberg, G. Wänström, G. Andersson, and T. Lunner. 2014. A randomized controlled trial evaluating the effects of online rehabilitative intervention for adult hearing-aid users. International Journal of Audiology 53(7):452–461.

Tremblay, K. L., A. Pinto, M. E. Fischer, B. E. Klein, R. Klein, S. Levy, T. S. Tweed, and K. J. Cruickshanks. 2015. Self-reported hearing difficulties among adults with normal audiograms: The Beaver Dam Offspring Study. Ear and Hearing 36(6):e290–e299.

Viana, L. M., J. T. O’Malley, B. J. Burgess, D. D. Jones, C. A. Oliveira, F. Santos, S. N. Merchant, L. D. Liberman, and M. C. Liberman. 2015. Cochlear neuropathy in human presbycusis: Confocal analysis of hidden hearing loss in post-mortem tissue. Hearing Research 327:78–88.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2021. World report on hearing. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

WHO. 2024. Self-care for health and well-being. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/self-care-health-interventions#:~:text=Self%2Dcare%20is%20the%20ability,devices%2C%20diagnostics%20and%20digital%20tools (accessed December 3, 2024).

Wang, H., Y. Chen, J. Lv, X. Cheng, Q. Cao, D. Wang, L. Zhang, B. Zhu, M. Shen, C. Xu, M. Xun, Z. Wang, H. Tang, S. Hu, C. Cui, L. Jiang, Y. Yin, L. Guo, Y. Zhou, L. Han, Z. Gao, J. Zhang, S. Yu, K. Gao, J. Wang, B. Chen, W. Wang, Z. Chen, H. Li, and Y. Shu. 2024. Bilateral gene therapy in children with autosomal recessive deafness 9: Single-arm trial results. Nature Medicine 30:1898–1904.

Wu, P. Z., J. T. O’Malley, V. de Gruttola, and M. C. Liberman. 2021. Primary neural degeneration in noise-exposed human cochleas: Correlations with outer hair cell loss and word-discrimination scores. Journal of Neuroscience 41(20):4439–4447.