Measuring Meaningful Outcomes for Adult Hearing Health Interventions (2025)

Chapter: 5 Outcomes for Hearing Health Interventions

5

Outcomes for Hearing Health Interventions

While researchers and clinicians have examined a variety of outcomes for specific etiologies or interventions for hearing loss, no standardized set of outcomes has been defined or assessed consistently across the hearing health field. Over time there has been an evolution in which outcomes have been measured, based in part on what has been meaningful to individuals with hearing loss. (See Chapter 6 for a brief history of assessing hearing health outcomes.) This chapter describes the broad outcomes for the domain of hearing and communication as well as the relevant outcomes for domains beyond hearing and communication that were considered by the committee for inclusion in a core set. Several of the outcomes are overlapping and interdependent. For example, difficulties understanding speech in noise and decreased social activity can lead to mental health conditions such as depression; varying concepts of psychological health, social connection, and physical health contribute to quality of life. For each outcome the committee considered the evidence regarding the connection between hearing loss and the outcome as well as evidence for the ability of various interventions to affect the outcome at the individual level. The committee combined this evidence with evidence from Chapter 4 (for which outcomes are most meaningful to adults with hearing difficulties) to determine a final core outcome set. A high-level view of the ability to measure the outcome also was considered. Chapter 6 provides further detail on specific measures to assess the core outcome set.

PROXIMAL OUTCOMES OF HEARING HEALTH INTERVENTIONS

As a first step to determining a core outcome set, the committee needed to identify which outcomes to consider. The committee examined an extensive list of potential outcomes based on literature reviews of outcomes typically reported in studies of hearing interventions. The committee also hosted public webinars to hear directly from clinicians, professional groups, and adults with hearing difficulties. An online platform was established to invite members of the public to submit their comments as well. Based on this collective evidence, the committee conducted multiple iterative discussions to create a comprehensive set of outcomes to be considered for a core outcome set.

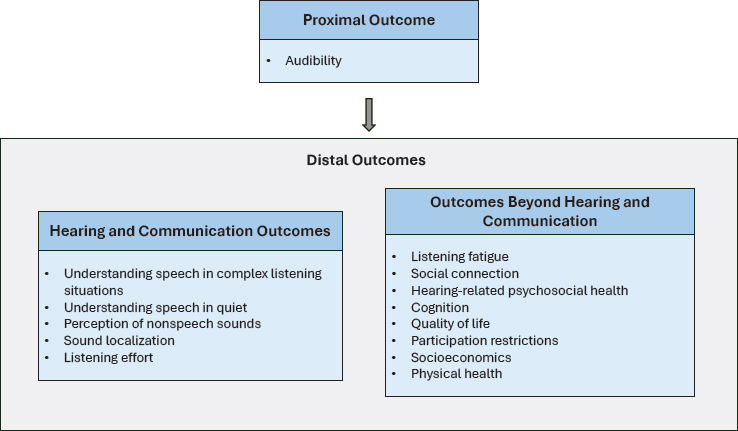

As shown in Figure 5-1, the committee considered both proximal and distal outcomes. Ultimately, the committee concluded that proximal outcomes are necessary precursors to outcomes of interest to individuals with hearing difficulties. Proximal outcomes are evaluated at the time of intervention. Distal outcomes are the outcomes that are typically most meaningful to adults with hearing difficulties. An overview of the key proximal outcome, audibility, is presented below.

Audibility

Audibility is defined as the ability to detect sound across a broad frequency range and across a range of input levels. Figure 5-2 illustrates the

approaches where maintenance or improvement of hearing, and therefore audibility, is the proximal outcome of the intervention. These approaches include interventions that use hearing aids (and other amplification devices), communication strategies that include environmental manipulation that improves signal-to-noise ratio, and biologic and pharmaceutical treatments. The proximal outcome is audibility, and an approach to improving audibility will be chosen depending on the individual’s type, configuration, and degree of hearing loss and the target of the treatment. Improvement of audibility, which would be expected to be accomplished at the time of the intervention, is fundamental to the success of the intervention. However, given that the approach for improving audibility varies, the measurement of this proximal outcome cannot be achieved with a single approach for all contexts.

Restoring audibility through amplification has been the primary treatment for sensorineural hearing loss for decades (Ricketts, et. al., 2017). Although biologic, pharmaceutical, and genetic treatments of sensorineural hearing loss are being actively explored as investigational treatments, hearing aids remain the most widely available treatment (Isherwood et al., 2022; Le Prell, 2023). Audibility in the context of a hearing aid fitting requires frequency-specific manipulation of the incoming signal differentially as a function of input level (i.e., selective amplification). In this context, audibility is defined as the ability to detect sound across a defined frequency range (typically the range where speech sounds are expected to be prominent) and across a range of input levels (i.e., soft, moderate, and loud) while maintaining comfort related to the loudness of the amplified sounds. That is, the audibility of important sounds, such as speech over a wide range of

levels, must be restored while also assuring that the sounds are not uncomfortably loud.

Otoprotective drugs have been assessed for threshold protection (i.e., prevention of the loss of audibility) (Brock et al., 2018; Kil et al., 2017; Kopke et al., 2015). In addition, in the case of biologics, improvement in threshold sensitivity has been a primary outcome of interest. In both cases, audibility continues to be the proximal outcome, but in these cases hearing sensitivity is being manipulated (i.e., the maintenance of current hearing or the restoration of hearing ability) rather than the incoming signal being manipulated, as is the case with hearing aid (amplification) interventions.

Approaches to the Measurement of Audibility

The difference among these interventions is not the proximal outcome (audibility) but the measurements used to verify that the intervention has been applied successfully (i.e., that audibility has been improved or maintained). The most common treatment for sensorineural hearing loss involves amplifying the incoming signal to improve hearing function. This is accomplished most often with an appropriate hearing aid fitting, but other devices such as assistive listening devices (including FM, infrared, and loop systems) also can amplify sounds of interest with or without the use of hearing aids. For hearing aids, the amplification is set in a manner that makes an incoming signal (e.g., speech) audible for quiet, moderate, and loud inputs across frequencies without being uncomfortable while realistically accounting for hearing thresholds (e.g., considering the level of gain needed or the expected distortion).

There are two evidence-based fitting formulas that provide targets to achieve this goal: the National Acoustic Laboratories Non-Linear 2 (NAL-NL2) and the Desired Sensation Level Version 5 (DSL v.5) (Keidser et al., 2012; Scollie et al., 2005). These targets are derived from the decibels hearing level (dB HL) pure-tone hearing thresholds of the individual. The output of the hearing aid as measured by a microphone in the ear canal is manipulated until the output matches the targets. Given that hearing threshold is displayed in dB HL, the transformation to decibels sound pressure level (dB SPL) required to derive targets will typically be obtained by measuring the individual’s real-ear-to-coupler difference (Munro and Buttfield, 2005; Scollie et al., 2011; Vaisberg et al., 2018);1 this supports transformation

___________________

1 The real-ear-to-coupler difference is a real-ear measurement that is used as a part of hearing aid fittings. It measures the “difference in [decibels] across frequencies, between the SPL measured in the real-ear and in a 2cc coupler, produced by a transducer generating the same input signal” (Pumford and Sinclair, 2001).

from dB HL to dB SPL. The real-ear aided response measures output from the hearing aid in the individual’s ear canal;2 it is measured to verify that the incoming signal is matching targets and therefore audibility has been improved as much as possible given hearing loss constraints (Baker, 2017). This verification process (that the desired amplification has been achieved) is described in all available clinical practice guidelines from the audiology professional associations.

Rather than manipulating the incoming signal, the goal may be to maintain (e.g., with protective agents) or alter an individual’s hearing (e.g., with pharmaceutical or gene therapy). In this case the signal is not being manipulated, rather the change is targeted at the individual’s hearing function. This change will be measured either in terms of behavioral thresholds (e.g., measured with an audiogram) returning to the normal range of hearing (e.g., 0–20 dB HL across frequency) or as a decrease in the intensity level required for detection (across frequencies) (Carhart and Jerger, 1959). An audiogram is obtained in a soundproof booth with signals across frequencies being delivered to the individual through earphones in order to obtain ear-specific data. The individual responds whenever he or she hears a sound, with the clinician recording the lowest intensity level at each frequency where the signal is detected 50 percent of the time. The audiogram has been the clinical gold standard since the 1940s (Le Prell et al., 2022) and has served as the primary outcome measure in most investigations of possible otoprotective therapies (Le Prell, 2021).

In addition, when hearing sensitivity is the proximal outcome of interest, peripheral physiologic responses of auditory function that predict hearing thresholds may be applied. This may include the auditory brainstem response (ABR), among other peripheral physiologic measures. The ABR, along with similar peripheral electrophysiological measures, can be used to estimate thresholds and therefore verify the audibility of a signal. To perform these tests, clinicians place electrodes on the skin (e.g., forehead, earlobe, ear canal) that record brain wave activity in response to sound. This technique to verify audibility would most typically be applied to an individual who cannot voluntarily respond to a signal (e.g., young children, nonresponsive patients).

Of note, there are a variety of physiological measures that can be used in diagnosing hearing loss, assessing neural integrity, and evaluating more central auditory processing. In the case of this report, the committee is only

___________________

2 The real-ear aided response is a real-ear measurement that is used as a part of hearing aid fittings. It measures the “frequency response of a hearing aid that is turned on, measured in the ear canal, for a particular input signal” (Pumford and Sinclair, 2001).

describing peripheral physiological measures as they relate to verification of audibility (threshold estimation). In emerging therapies, the restoration of hearing may be the initial (proximal) outcome that is targeted to prove that the treatment can work prior to addressing distal outcomes. However, the committee emphasizes the relevance of distal outcomes in the evaluation of pharmaceuticals and biologics, given that audibility (as a proximal outcome) is necessary but not sufficient to assure positive results with distal outcomes.

Although not the focus of this study, a third treatment strategy is to reroute the signal to achieve audibility. This is the case in treatments involving cochlear implants, auditory brainstem implants, midbrain implants, and bone-conducted signals. The treatment is verified by detecting a change in behavioral thresholds either with documented thresholds at lower levels or within the normal range of hearing.

Although it is a necessary precursor for desired outcomes of treatment, ensuring audibility alone does not guarantee desired distal outcomes. More distal outcomes would be measured as appropriate to the overarching goals of the treatment, regardless of the treatment modality. Whether a patient completes auditory training, receives hearing aids, or is treated with a pharmaceutical or biologic agent, distal outcomes are what patients identify as meaningful.

Conclusion 5-1: The improvement of audibility is a critical proximal outcome and requires verification. The methods for verification of audibility, however, vary depending on the intervention (e.g., changing hearing versus changing the incoming signal through amplification). As a result, the approach to measurement depends on the context, which does not align with the committee’s approach to create a universally applicable core outcome set with consistent measures for all circumstances. Therefore, the verification of audibility is not included in the core set.

Conclusion 5-2: Improvement in more distal outcomes may rely on improved audibility, but improved audibility does not guarantee desired distal outcomes. Therefore, improved audibility is a necessary precursor to attaining successful outcomes, but in most cases it is insufficient as a meaningful outcome for hearing health interventions.

Conclusion 5-3: Use of improved audibility as the outcome of interest may be appropriate at early stages in the evaluation of novel interventions such as biologics, pharmaceuticals, and gene therapy. Even here, however, it is desirable that the evaluation of outcomes

eventually progress to the inclusion of distal outcomes assessing everyday function.

HEARING AND COMMUNICATION OUTCOMES

As noted earlier, there is no consensus on core outcomes for hearing health interventions. As a result, a variety of outcome domains and individual outcomes have been defined in the literature to capture aspects of hearing and communication. Recent examples include:

- Speech in noise, speech in quiet, hearing thresholds, spatial hearing (localization), quality of hearing, hearing in reverberant conditions, binaural hearing and sound segregation, psychoacoustic performance, motion perception, hyperacusis, middle-ear function, softness of sound, and tinnitus perception, among others (Katiri et al., 2021).

- Communication ability (Allen et al., 2022).

- Clarity, sound distance, being aware of a sound, listening in complex situations, listening in reverberant conditions, group conversation in quiet, one-to-one conversation in general noise, group conversation in noisy social situations, sound localization, adverse listening environments, spatial orientation, one-to-one conversation in quiet, aversion to loud sounds (Katiri et al., 2022).

- Daily hours of hearing aid use, hearing handicap, hearing aid benefit, and communication and psychological outcome (Barker et al., 2015).

In its review of the literature and information gathered in public webinars and the committee’s public platform, the committee considered the extensive list of potential outcomes and identified the following key outcomes for hearing and communication that are potentially meaningful to individuals with hearing difficulties:

- Understanding speech in complex listening situations;

- Understanding speech in quiet;

- Perception of nonspeech sounds;

- Sound localization; and

- Listening effort.

While the committee’s overall conclusions regarding individual outcomes for hearing and communication are summarized in Table 5-1, the following sections elaborate on each of these outcomes and present evidence for inclusion of the outcome in the core set.

TABLE 5-1 Outcomes in Hearing and Communication Considered for Core Set

| Outcome | Conclusion |

|---|---|

| Understanding speech in complex listening situations | Meaningful and a key complaint. Important to measure (intervention can impact outcome), and existing measures have a sufficient amount of psychometric data supporting the quality of the measures. |

| Perception of nonspeech sounds (e.g., music, nature) | Meaningful to specific subpopulations but not a key complaint. Psychometric data for existing measures are limited. Interventions meeting needs for speech in complex listening situations often meet needs for this outcome. |

| Understanding speech in quiet | Meaningful, but not a key complaint. Interventions meeting needs for speech in complex listening situations typically meet needs for this outcome. |

| Sound localization | Meaningful, but less frequently raised as a significant difficulty compared to other outcomes. Lack of feasible measures with a sufficient amount of psychometric data supporting the quality of the measures for sound localization specifically. Measurement development and refinement needed. |

| Listening effort | Meaningful, but outcome is not consistently defined. Measure development and refinement needed. |

Understanding Speech in Complex Listening Situations3

Speech communication is defined as an exchange of information through the use of spoken words (Oxford Reference, n.d.). The ability to detect, discriminate, recognize, and identify speech is essential for effective spoken verbal communication (ASHA, n.d.). Impairments in speech communication, in turn, can cause a range of difficulties, from problems maintaining personal relationships and being able to participate in the workplace to navigating the health care system (Cunningham and Tucci, 2017). Individuals with hearing difficulties frequently need to ask people to repeat themselves or enunciate more clearly, and even then they may not be able to fully comprehend a conversation (Arlinger, 2003).

Everyday settings provide speech-communication challenges for many adults owing to the presence of competing sounds. Settings with background noise or reverberant acoustics degrade sound, making it very challenging for adults with hearing difficulties to understand speech (Contrera et al., 2016; Humes and Dubno, 2010; Mattys et al., 2012; Neal et al., 2022).

___________________

3 While the term speech in noise is typically used, the committee prefers the use of speech in complex listening situations, which includes understanding speech in a variety of contexts including noisy environments, accented language, multiple speakers, with music playing, and other situations that complicate an individual’s ability to understand speech.

Additional contextual obstacles to effective communication include distance from the sound source, intensity level of the speech, fast speech, shouting, unfamiliar accents, having the speaker’s mouth covered, energy levels of the listener, and lack of awareness by a speaker of the listener’s hearing loss (Hines, 2000; Mattys et al., 2012). Speech communication in these types of complex listening situations is particularly challenging because so many social interactions occur in adverse listening environments such as restaurants, parties, and noisy office settings (Bottalico et al., 2022; Bronkhorst, 2015; NASEM, 2016). People with hearing difficulties often avoid adverse or difficult listening environments because of the stress of not being able to communicate effectively and a fear of embarrassing oneself (Bennett et al., 2022). As a result, many people with hearing difficulties face activity limitations and participation restrictions and can become isolated and or lonely.

As noted in Chapter 4, multiple sources from the published literature, industry and consumer surveys, as well as evidence gathered by this committee indicate that many adults with hearing difficulties identify speech communication in noise as one of their most frequent and most severe hearing-related difficulties.

Conclusion 5-4: Evidence across the literature, in webinars, and from other sources shows that the ability to communicate in complex listening situations is the primary concern of most adults with hearing difficulties. Furthermore, the ability to understand speech in complex listening situations is an underlying factor for other outcomes, including psychological health, listening effort, and listening fatigue, since most social interactions occur in environments with competing background noise. Evidence also shows that the outcome is important to measure (i.e., intervention can significantly affect the outcome) and that existing measures have a sufficient amount of psychometric data supporting their quality.

Conclusion 5-5: Understanding speech in complex listening situations should be included in a core outcome set, meaning that it should be universally measured across settings and intervention types.

Understanding Speech in Quiet

Individuals with more severe hearing loss may have difficulties comprehending speech even in quiet settings (WHO, 2021). This outcome may be especially meaningful for these populations, as they may require the use of assistive devices to understand speech in quiet as well as noisy settings. Furthermore, understanding speech in quiet is essential for virtually all adults with hearing difficulties because if an individual cannot

hear in a quiet environment, he or she will be even more challenged with background noise. However, examining the ability to detect and recognize speech in quiet alone is insufficient to evaluate the effect of hearing difficulties on everyday function. Data from a clinical convenience sample of 5,808 patients at Stanford Ear Institute revealed that many patients have significant challenges on the Quick Speech-in-Noise (QuickSIN) test despite normal word recognition in quiet (Fitzgerald et al., 2023). Effects of hearing loss on word recognition in quiet and in noise vary with hearing loss etiology, with sensorineural hearing loss and mixed hearing loss having greater effects on word recognition than conductive hearing loss, as shown in a second large convenience sample (5,593 patients at Stanford Ear Institute) (Smith, et al., 2024). More recent data from a smaller sample (1,633 patients at Stanford Ear Institute) revealed that word-in-quiet scores were not associated with disability measured using the 12-item Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing Scale, but QuickSIN scores were associated with disability (Fitzgerald, et al., 2024). Data from a second clinical convenience sample of 3,400 patients seen in the audiology clinic at the Mountain Home, Tennessee, VA Medical Center similarly revealed many patients to have significant challenges on the Words-in-Noise (WIN) test despite normal word recognition in quiet (Wilson, 2011).

Conclusion 5-6: While understanding speech in quiet may be very meaningful to specific subpopulations (e.g., adults with more severe hearing loss), this outcome does not rise to the level of a core outcome because it is not identified by most adults with hearing difficulties as a frequently occurring or important difficulty. Furthermore, treatments meeting the needs for understanding speech in complex listening situations also typically meet the needs for this outcome.

Perception of Nonspeech Sounds

Individuals with hearing difficulties may not be able to detect, identify, locate, or appreciate nonspeech sounds, including alarms, sirens, traffic, music, and birds and other nature sounds (Arlinger, 2003; Bainbridge and Wallhagen, 2014). Many contextual factors make nonspeech sounds harder to identify and locate. In everyday listening, environmental sounds occur within the context of other sounds, and missing some auditory cues will make it more difficult to identify sounds of interest (Pichora-Fuller et al., 2016). The inability to identify and localize environmental sounds and safety signals is a safety concern and puts people with hearing loss at risk of physical injury (Dixon et al., 2020). For example, a dangerous situation may arise when a person is walking through a busy parking lot without the ability to hear a car approaching nearby.

The inability to perceive nonspeech sounds can have a range of consequences on one’s everyday life and well-being. For example, many people with hearing difficulties cannot enjoy music like they did before their hearing loss (Dixon et al., 2020), as it may sound distorted and the chords and pitch may be indistinguishable (Leek et al., 2008). Music can even sound unpleasant, which can significantly impair quality of life for people who place a high value on listening to music. The committee recognizes that for subpopulations such as musicians, deficits related to perception of nonspeech sounds such as music can be career limiting, and supplemental measures for this outcome may need to be considered in such cases (Wartinger et al., 2019).

Conclusion 5-7: While the perception of nonspeech sounds (e.g., alerting signals, music, nature) may be very meaningful to specific subpopulations, this outcome does not rise to the level of a core outcome because it is not consistently identified by most adults with hearing difficulties as a frequently occurring or important difficulty, and few measures are available that have a sufficient amount of psychometric data supporting their quality. In addition, nonspeech sounds include a large range of signals making this difficult to apply across individuals with various listening needs. Furthermore, treatments meeting the needs for understanding speech in complex listening situations often meet the needs for this outcome in many contexts. Although not part of the core set, clinicians can target assessment of perception of specific nonspeech sounds depending on the needs and goals of an individual.

Sound Localization

The auditory system detects the location of sounds by analyzing spatial cues that are processed in the auditory portions of the central nervous system from the brainstem through the cortex (Middlebrooks, 2015). Sound localization involves the identification of the origin of sounds emanating from various locations in space and may include horizontal (left/right), vertical (up/down) and front/back locations as well as the perception of distance and motion of sound. Interaural timing differences and interaural level differences perceived by the auditory system are used to identify the location of sounds. Interaural timing difference (ITD) is the difference in the time it takes sound to reach one ear versus the other. Similarly, interaural level difference (ILD) is the difference in sound levels that reach the two ears. ITDs and ILDs are the primary cues for the localization of sounds in the horizontal plane.

As with most aspects of hearing, these cues become less salient for those with hearing loss and when background noise is present. High-frequency

spectral energy provides key cues for the localization of sound in the horizontal (ILD) and vertical planes as well as for front/back distinctions. The latter two involve the shaping of sounds by the outer ear, primarily the pinna. Hearing loss, especially in higher frequencies (above about 1,500 Hz), and devices worn in the outer ear, such as hearing aids, can negatively affect the ability to localize sound.

People with untreated hearing loss have worse localization performance in both the horizontal and vertical planes than people with normal hearing (Noble and Byrne, 1990; Noble et al., 1994). Sound localization tests in hearing aid wearers have shown mixed results, with some studies showing poorer performance among hearing aid wearers than among individuals with hearing loss who are not hearing aid wearers, depending on the type of hearing aid and signal processing employed (Noble and Byrne, 1990; Zheng et al., 2022). Because sound localization relies on reliable and specific timing and intensity cues across the frequency domain (i.e., ITD, ILD, and spectral cues), these cues must be processed and reproduced accurately for hearing aid wearers to be able to correctly localize sounds.

The testing of sound localization by hearing health professionals may require equipment that is expensive and may not reflect real-world situations (Almeida et al., 2019). Given that sound localization ability is essential for the situational awareness and safety of military, law enforcement, and industrial workers, there have been some efforts to develop portable and affordable test systems (Thompson et al., 2024). In addition to the objective measurement of sound localization, several self-report measures seek to capture an individual’s ability to localize sound (see Appendix B). Notably, the Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing Scale includes items related to sound localization (i.e., directional and distance judgments) among many other items related to various outcomes (Gatehouse and Noble, 2004). However, current measures have not been validated specifically for sound localization, especially regarding sensitivity to change.

Conclusion 5-8: Sound localization, although an important ability, does not rise to the level of a core outcome. While difficulties with sound localization are a common complaint, they are raised less frequently than other outcomes.

Conclusion 5-9: There is a lack of feasible measures validated for sound localization specifically. Current measures require the use of advanced equipment unavailable to many clinicians. Some self-report measures attempt to assess localization, but they have not been adequately validated for this outcome, especially regarding sensitivity to change following intervention.

Listening Effort and Listening Fatigue4

People with hearing difficulties often report that they have to try harder to follow conversations, particularly when in complex listening situations; this can be taxing over time (McGarrigle et al., 2014). The phenomena of trying harder and being taxed by the effort are referred to as listening effort and listening fatigue, respectively. Listening effort has been defined as “a specific form of mental effort that occurs when a task involves listening,” and listening fatigue has been defined as “simply fatigue resulting from the continued application of effort during difficult listening tasks” (Hornsby and Kipp, 2016; Pichora-Fuller et al., 2016). A significant amount of research has been conducted on listening effort and listening fatigue. However, inconsistencies in the definitions, populations, and methodologies have led to a lack of consensus on the best way to study and measure these constructs. The consensus-based, theoretical Framework for Understanding Effortful Listening (FUEL) was developed in 2015, and while it is complex and comprehensive, it has not been widely adopted in hearing health.

Listening Effort

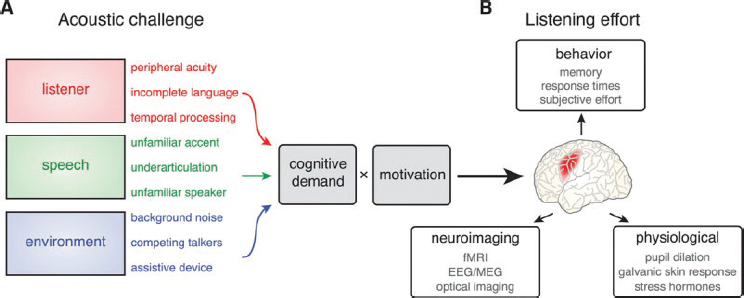

Listening demand (also called cognitive demand) reflects the mental resources required to understand speech in acoustically challenging environments (Peelle, 2018). Factors such as background noise, reverberations, competing speakers, intensity, frequency, speed of speech, and accents or other speech differences all affect the quality of speech and can make it more challenging for people with hearing difficulties to comprehend that speech (Davis et al., 2021). Listening effort is a product of cognitive demand and the intensity level of motivation (see Figure 5-3). The motivational intensity theory acknowledges that listening effort is influenced by how important it is to the listener to comprehend the speech and how realistically the individual can understand it (Richter, 2016). If the listener does not deem the conversation important or possible to comprehend, then the individual may not be motivated to expend as much effort trying to understand it, thereby conserving cognitive energy but missing information. Adults with hearing difficulties, even when motivation is high, may encounter misperceptions that can lead to miscommunications and inaccuracies.

A 2017 systematic review demonstrated that while there was some evidence that listening effort increased more during speech tasks for listeners with hearing loss (as compared with listeners with normal hearing), there was insufficient evidence to conclude that amplification decreased listening

___________________

4 While the committee discusses listening fatigue together with listening effort, the committee considers listening fatigue to be a downstream effect of hearing and communication difficulties, and therefore fatigue is designated as an outcome “beyond hearing and communication.”

NOTE: fMRI = functional magnetic resonance imaging; EEG/MEG = electroencephalography/magnetoencephalography.

SOURCE: Peelle, 2018. CC BY-NC-ND.

effort (Ohlenforst et al., 2017). Furthermore, the studies lacked consistency and standardization in measures and approach and lacked statistical power.

Conclusion 5-10: While listening effort is meaningful to adults with hearing difficulties, it does not rise to the level of a core outcome at this time because of inconsistencies with its definition.

Listening Fatigue

Listening fatigue is thought to be a cumulative consequence of repeated encounters with effortful listening situations. Listening fatigue manifests as multiple types of symptoms, including headaches, increased need for sleep, and general low energy levels (Davis et al., 2021). Feeling mentally drained after a period of effortful listening is a common experience for many adults with hearing difficulties. Chronic listening fatigue has numerous consequences for an individual’s quality of life, including lower productivity, mistakes in the workplace, social isolation, less physical activity, and depression (Davis et al., 2021). A theoretical framework developed by Davis and colleagues (2021) demonstrates the dynamic relationship between situational determinants of listening–related fatigue and experiences of fatigue, resulting in coping strategies to minimize the adverse effects of fatigue. Situational determinants include external factors (e.g., noisy conditions, listening in large groups or for a long period of time) and internal factors (e.g., relationship to the talker, importance of the listening situation). Experiences of fatigue include physical experiences (e.g., exhaustion, low energy), cognitive/mental experiences (e.g., difficulty thinking, inability to concentrate), social experiences (e.g., isolation), and emotional experiences (e.g., frustration, sadness, stress). Coping strategies can

be behavioral (e.g., resting, use of hearing devices), social (e.g., avoidance of listening situations), or acceptance (e.g., “pushing through” fatigue).

More research is needed to determine if the use of hearing aids reduces listening fatigue, as current evidence shows there are large inconsistencies in both the types of populations that are studied and the self-reported measures used (Holman et al., 2021).

Conclusion 5-11: While listening fatigue is meaningful to adults with hearing difficulties, it does not rise to the level of a core outcome at this time because of inconsistencies with its definition.

Conclusion 5-12: Listening effort and listening fatigue are separate, yet potentially related, constructs. However, current definitions and theoretical approaches are not consistent. Future research is needed on the separate constructs of listening effort and listening fatigue themselves that incorporate a robust theoretical framework, a clear study population of adults with hearing loss (and a control group), and adequate statistical power.

Conclusion 5-13: More research is needed regarding if and how hearing health interventions reduce listening effort and/or listening fatigue in real-world conditions, in the short and long term.

The Current State of Measurement for Listening Effort and Listening Fatigue

Three main methods have been used for capturing listening effort: (1) physiological measures, (2) behavioral measures, and (3) self-report measures. Listening fatigue is most commonly captured via self-report measures (McGarrigle et al., 2014; Shields et al., 2023).

Physiological measures capture autonomic responses from the body in situ (reactive) under various listening tasks and conditions; examples include pupillometry, skin conductance, heart rate, encephalography, and functional imaging. Behavioral measures or performance-based measures require patients to participate in a task; this commonly includes a dual-task paradigm with speech recognition as a primary task and a secondary task that results in a memory recall score or reaction time. Finally, self-report measures are often used and come in the form of a questionnaire with a set of items inquiring about effortful listening or fatigue or through the use of various visual analog scales administered in conjunction with a listening task (Alhanbali et al., 2017; Keur-Huizinga et al., 2024; McGarrigle et al., 2014; Shields et al., 2023).

A multitude of individual measures of listening effort exist. (See Appendix B for examples of each method.) Many measures are study specific, and currently there is no gold-standard measure. Most measures of listening effort, regardless of their method, have no or weak correlations, indicating

that listening effort is a multidimensional construct (Keur-Huizinga et al., 2024; Shields et al., 2023).

Conclusion 5-14: Currently, there is not a single broadly accepted measure of listening effort or listening fatigue, yet some measures show promise. More research is needed to develop and refine measures in order to promote a standard way to measure listening effort and listening fatigue in clinical and research settings.

OUTCOMES BEYOND HEARING AND COMMUNICATION

Examining outcomes beyond hearing and communication can help capture additional aspects of hearing health that are meaningful to adults with hearing difficulties. When considering a whole health approach, the person’s needs are put at the center, shifting the focus from exclusively treating symptoms and disease-oriented medicine to recentering what matters to the individual (NASEM, 2023). Whole health takes into consideration “physical, behavioral, spiritual, and socioeconomic well-being as defined by individuals, families, and communities” (NASEM, 2023, p. 4). Improving hearing and communication is strongly correlated with improvement in outcomes beyond hearing and communication, such as social connection, education, quality of life, and occupational opportunities (Borre et al., 2023). Hearing-related social and emotional difficulties often are reduced following intervention with hearing aids (e.g., Chisolm et al., 2007). Therefore, measuring outcomes of hearing and communication alone may not fully capture an individual’s hearing difficulties or the effect of hearing health intervention on those difficulties.

Similar to outcomes of hearing and communication, a variety of outcome domains and individual outcomes have been defined in the literature to capture outcomes of hearing health interventions beyond hearing and communication. Outcomes reported in the literature include:

- Personal relationships, well-being, and participation restrictions (Allen et al., 2022).

- Effects on individual activities, discomfort in listening situations, effect on learning, treatment satisfaction, device usage and malfunction, vulnerability, avoiding social situations, motivation, emotional distress, personal safety, self-stigma, dissatisfaction with life, balance problems, manual dexterity (Katiri et al., 2022).

- Global cognitive function, executive function, processing speed, and auditory and visual working memory (Glick and Sharma, 2020).

- Emotional/psychological impact, lifestyle impact, sleep, auditory perception, general health impact (Langguth and De Ridder, 2023).

In its review of the literature and information gathered in public webinars and the committee’s public platform, the committee considered an extensive list of potential outcomes and identified the following key outcomes beyond hearing and communication:

- Listening fatigue,5

- Social connection,

- Hearing-related psychosocial health,

- Cognition,

- Quality of life,

- Socioeconomic effects;

- Participation restrictions; and

- Physical health.

The committee’s overall conclusions regarding outcomes beyond hearing and communication are summarized in Table 5-2, while the following sections define each of these outcomes and present evidence for inclusion of the outcome in the core set.

Social Connection

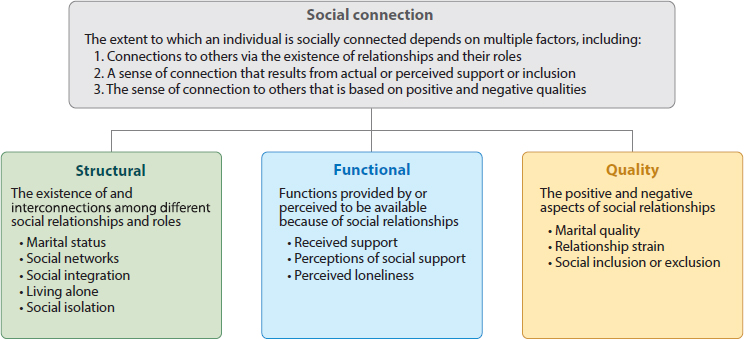

Hearing loss among older adults affects speech communication and, as a result, alters social interactions (Shukla et al., 2020). As noted in the 2020 National Academies study Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults:

The broad, interdisciplinary scientific fields that together form the modern science of social relationships have used a variety of terms (e.g., social isolation, social connection, social networks, social integration, social support, social exclusion, social deprivation, social relationships, loneliness) to refer to empirical phenomena related to social relationships. Although there are important distinctions among these terms concerning what they describe or measure, they are often, incorrectly, used interchangeably. (NASEM, 2020, p. 28)

Some of the key terms include:

- Social support—the actual or perceived availability of resources (e.g., informational, tangible, emotional) from others, typically one’s social network

- Social isolation—the objective lack of (or limited) social contact with others

___________________

5 Listening fatigue is discussed in conjunction with listening effort in the previous section on hearing and communication outcomes.

TABLE 5-2 Outcomes Beyond Hearing and Communication Considered for Core Set

| Outcome | Conclusion |

|---|---|

| Listening fatigue | Meaningful, but outcome is not consistently defined and measured. Measure development and refinement needed. |

| Social connection | Meaningful, but insufficient evidence that the intervention has a significant clinical effect on the outcome at the individual level. |

| Hearing-related psychosocial health | Meaningful, important to measure, existing measures have a sufficient amount of psychometric data supporting the quality of the measures. |

| Cognition | Meaningful, but there is inconsistency in the cognitive construct being measured. Insufficient evidence that the intervention has a significant clinical effect on the outcome at the individual level. |

| Quality of life | Meaningful, but there is inconsistency in the definition of the outcome and in the underlying constructs being measured. Many contributing factors to quality of life make measuring the direct effect of hearing intervention on the outcome difficult. Key constructs of psychological, social, and emotional health are covered by hearing-related psychosocial health. |

| Socioeconomic effects | Might be meaningful to specific subpopulations and types of research, but not a key complaint. |

| Participation restrictions | Outcome is inconsistently defined and measured. |

| Physical health | Not a key complaint. Insufficient evidence on the direct connection between hearing health interventions and physical health outcomes. |

- Loneliness—the perception of social isolation or the subjective feeling of being lonely

- Social connection—an umbrella term that encompasses the structural, functional, and quality aspects of how individuals connect to each other (NASEM, 2020)

As illustrated in Figure 5-4, social connection consists of three components: structure, function, and quality.

Structure includes objective measures of connection, including the size and variety of one’s social network and the frequency of interaction with others. An estimated 24 percent of older adults are socially isolated (Shukla et al., 2020). Rates of social isolation are consistently higher in adults with untreated hearing loss than in adults with normal hearing (Shukla et al., 2020). As noted earlier, a significant challenge with hearing loss is comprehending auditory information in real-world settings, which makes communication very difficult. Consequently, many individuals are less likely

SOURCE: Holt-Lunstad, 2018. © Annual Reviews, used with permission.

to participate in social activities because of the fear of embarrassing themselves or not being able to fully engage with others (WHO, 2021).

Adults with hearing difficulties who participated in the committee’s public webinars noted their inability to enjoy experiences like music, live performances, and movies.6 Hearing loss contributes to challenges in communicating effectively with loved ones, which can cause frustration or resentment for both the individual with hearing difficulties and their family and friends. These factors shrink one’s social network and can lead to social isolation, which in turn can contribute to a wide variety of negative health effects (NASEM, 2020).

The functional component of social connection reflects whether these relationships meet an individual’s emotional support needs (Holt-Lunstad, 2018). This component encompasses loneliness and subjective satisfaction with one’s social connections. Untreated hearing loss may make it more challenging to retain close relationships and build new ones; as such, it is plausible that people with hearing difficulties, especially and specifically late-onset hearing difficulties in adults without alternative language modes such as signed languages, may be less satisfied with their social networks than those with normal hearing ability.

One person may have a very small social network and be content and not feel lonely, while another person may have a large social network and still feel lonely. Social isolation can lead to loneliness either because

___________________

6 The webinar recordings can be accessed at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/41996_02-2024_meaningful-outcome-measures-in-adult-hearing-health-care-webinar-1 and https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/42414_04-2024_meaningful-outcome-measures-in-adult-hearing-health-care-webinar-2

someone’s social network shrinks or because the hearing loss is infringing on the person’s ability to engage (Jayakody et al., 2022). Loneliness is associated with depression, reduced physical activity, decreased satisfaction with life, and poor self-perceived well-being. Like social isolation, loneliness can contribute to a wide variety of negative health outcomes (NASEM, 2020).

The final component of social connection is quality, which involves satisfaction with existing relationships (Holt-Lunstad, 2018). Since effective communication is essential for all types of healthy relationships, untreated hearing loss can make it challenging to retain strong connections (Victory, 2021).

Recent systematic reviews suggest that hearing loss among older adults is consistently associated with loneliness and social isolation (Mick et al., 2014; Shukla et al., 2020). However, there is a paucity of longitudinal studies, and a major concern, especially with the social isolation measures, was a lack of consistency in the outcome measure used (Shukla et al., 2020). Indeed, some studies found positive associations but were limited to unvalidated questions and constructs of social isolation (Mick et al., 2014). When people with hearing difficulties do not seek treatment or develop coping mechanisms, they will likely avoid social situations and let relationships deteriorate, leading to more isolation and loneliness, which then causes poorer outcomes in other areas of health (Bennett et al., 2022). Social isolation and loneliness are both associated with a range of other health outcomes, including cognitive decline, depression, mortality, and coronary heart disease (NASEM, 2020; Shukla et al., 2020; Valtorta et al., 2016). Currently, the research is inconclusive about the degree to which interventions such as hearing aids can mitigate social isolation and loneliness (Ellis et al., 2021). Future research needs to be longitudinal, include a large sample size, and account for confounding variables to better understand this relationship.

Conclusion 5-15: While social connection is meaningful to virtually all adults with hearing difficulties, it does not rise to the level of a core outcome at this time because there is a lack of evidence that the intervention has a significant clinical effect on the outcome at the individual level. One reason for this is that many factors can influence social connection.

Conclusion 5-16: There are issues with the inconsistent use of measures for different aspects of social connection and a lack of validation of the measures specific to hearing.

Hearing-Related Psychological Health

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines mental/psychological health as “a state of mental well-being that enables people to cope with the

stresses of life, realize their abilities, learn well and work well, and contribute to their community” (WHO, 2022b). Extensive research exists on the relationships between untreated hearing loss and psychological health, including depression, anxiety, and other aspects of mental, psychological, and emotional health (Laird et al., 2020). Adults report that the adverse effects of their untreated hearing loss on their psychological health include worsening depression, anxiety, paranoia, and suicidal ideation (Laird et al., 2020). Each of these domains of psychological health, with evidence on the impact of chronic hearing loss, is reviewed below.

Depression

A broad range of research shows an association between depression and hearing loss (Amieva et al., 2018; Armstrong et al., 2016; Brewster et al., 2018; Gosselin et al., 2023; Jayakody et al., 2018; Lawrence et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2010; Strawbridge et al., 2000).

Symptoms of depression include feeling sad, irritable, hopeless, having low self-worth and low energy, and thoughts about dying or suicide (WHO, 2022a). Hearing loss is associated with many depressive symptoms, including sadness, guilt, low self-worth, loss of interest in daily activities, change in appetite, and disturbed sleep (Lawrence et al., 2020). Some adults with hearing difficulties experience severe depression and suicidal ideation (Cosh et al., 2019). Untreated hearing loss is known to reduce social participation (in part because of the inability to participate in activities that were previously enjoyed) and increase loneliness, putting older adults with hearing difficulties at an increased risk of developing depression (Lawrence et al., 2020). This may be compounded by the individual’s struggle to cope with the fact that hearing health interventions likely will not fully restore their hearing capacity (Laird et al., 2020). (See the previous section for more on social connection.)

However, whereas the majority of research finds an association between hearing loss and depression, several studies have not reached that same conclusion (Gopinath et al., 2009; Lawrence et al., 2020; Li et al., 2014; Mener et al., 2013). Comparison among studies is difficult because of the lack of standardized outcome measures for hearing loss or depression (Laird et al., 2020). For example, Armstrong and colleagues used both the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale 5 (CESD-5) and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), which showed differences in the strength of the association depending on the measure (Armstrong et al., 2016). The types of depression examined also vary across studies. Cosh and colleagues, for example, found an association between hearing loss and depressive symptoms but not between hearing loss and major depressive disorder (Cosh et al., 2018).

Anxiety

Anxiety disorder is a highly prevalent chronic condition and is associated with untreated hearing loss (Cetin et al., 2010). However, as with the research on depression, because various definitions and outcome measures have been used in research on anxiety disorder it becomes difficult to form simple conclusions. One study demonstrated a statistically significant association between the prevalence of anxiety measured by the Hopkins Symptom Checklist and mild untreated hearing loss (Contrera et al., 2017). With more severe hearing loss, researchers found that hearing aids were not statistically significantly associated with lower odds of anxiety.

The relationship between anxiety and hearing loss may be bidirectional (NCOA, 2023). Untreated hearing loss can cause or worsen symptoms of anxiety. First, hearing loss strains communication and can cause anxiety around social interactions and the ability to carry out everyday life activities. Anxiety also can be triggered by “feelings of worry and unease around uncertain outcomes related to hearing loss that might creep into all areas of life: social, professional, physical, financial, and emotional” (NCOA, 2023).

Psychosis

There is a growing literature supporting a connection between hearing loss and psychosis disorders. A meta-analysis found increased risk of hearing impairment for a range of psychosis outcomes including hallucination, delusions, psychotic symptoms, and delirium (Linszen, 2016). Currently, there is insufficient evidence of a causal relationship between hearing loss and psychiatric disorders, but it is recommended that psychiatrists and mental health professionals look for signs of hearing loss and refer patients to hearing health care (or over-the-counter devices, if suitable) (Blazer, 2020).

Hearing-Related Psychosocial Health

The preceding paragraphs demonstrate associations between hearing difficulties and a variety of mental, psychological, and emotional health issues, although the inconsistent findings across studies for each health issue reflects the complex nature of these health conditions. The committee collectively refers to this group of health issues as psychological health issues. As noted in the earlier section on social connection, hearing difficulties also negatively affect social wellness. Psychological health and social wellness are often intertwined such that psychological difficulties, such as depression or anxiety, may negatively impact social wellness. The committee collectively refers to this combination as psychosocial health. Some available outcome measures, such as the longstanding Hearing

Handicap Inventory for the Elderly (HHIE) (see Chapter 6), measure the effect of hearing difficulties on psychosocial health. The HHIE includes items addressing the effect of hearing difficulties on feelings of embarrassment, irritability, frustration, nervousness, anger, and depression, among other outcomes. The HHIE also has several items addressing the social consequences of hearing difficulties. Although the committee noted that psychological and social wellness are separate dimensions of wellness, the prevailing audiological measure capturing these dimensions (the HHIE) has been found to be unidimensional in recent psychometric analyses (Cassarly et al., 2020; Heffernan et al., 2020). The HHIE shows sensitivity to change, implying that hearing-related psychosocial health has improved following the intervention. After considerable discussion, the committee opted to refer to this combination of psychological and social challenges experienced by those with hearing difficulties collectively as hearing-related psychosocial health.

Conclusion 5-17: Evidence across the literature, in webinars, and from other sources shows that hearing-related psychosocial health is meaningful to virtually all adults with hearing difficulties, and it is a key element of the concepts of overall quality of life and health-related quality of life. Evidence also shows that the outcome is important to measure (i.e., intervention can significantly affect the outcome) and that existing measures have a sufficient amount of psychometric data supporting their quality.

Conclusion 5-18: Hearing-related psychosocial should be included in a core outcome set, meaning that it should be universally measured across settings and intervention types.

Cognition

Researchers have proposed that hearing loss may be mechanistically associated with cognitive decline via several mediating pathways, including cognitive load, structural changes in the brain, and social isolation. One of the first studies of the association between peripheral measures of hearing loss (e.g., pure-tone audiometry) and cognitive dysfunction in older adults was a case–control study in 1989 that found a strong relationship between a hearing loss of 30 dB or greater and the risk of developing dementia (Uhlmann et al., 1989). Nearly two decades later, researchers began to revisit and more closely examine the association between hearing loss and cognitive outcomes (including dementia as well as cognitive function), which has culminated in a body of work that suggests a possible association between hearing loss in older adults and a decline in cognitive function.

The earliest studies of the recent wave of work verified an association between hearing loss and cognitive decline in cross-sectional datasets (Lin, 2011). Later, longitudinal studies found that hearing loss was associated with cognitive decline over multiple years and suggested a temporal effect that hearing loss preceded cognitive decline (Lin et al., 2013; Maharani et al., 2018). Two meta-analyses have concluded that the overall body of research to date suggests an association between hearing loss and performance on cognitive measures in older adults (Loughrey et al., 2018; Yeo et al., 2023). Various professional groups also have concluded that such a relationship exists (Lazar et al., 2021; Livingston et al., 2020). Research has culminated in the inclusion of hearing loss in the 2020 and 2024 Lancet Global Commission on Dementia reports (Livingston et al., 2020, 2024). Using meta-analyses and population attributable fraction models, the 2024 report suggests that 7 percent of all dementia cases are attributable to hearing loss. However, caution is needed when interpreting the figure as it assumes no unmeasured confounding. Moreover, the model highlights the importance of considering population- versus individual-level risk as hearing loss is extremely prevalent among older adults, so the effects may appear large at the population level but relatively smaller at the individual level. More work is needed to better understand individual-level risk for consideration in proposing a core set of outcome measures.

Another limitation of the research relevant to proposing a core set of outcome measures is that the studies use different measures of cognition and a large percentage of them are memory based, so it is difficult to definitively determine which cognitive functions are affected by hearing loss and whether others remain unaffected. A general concern in the cognition literature is that, beyond screening measures such as the Mini Mental State Examination and Montreal Cognitive Assessment, few tests are standardized or normed to the population and none are diagnostic, which limits external inferences beyond specific study populations.

Several studies suggest that the use of hearing aids may provide a certain amount of protection against cognitive losses in older adults whose hearing has gotten significantly worse. For instance, while the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing found poorer cognition among older adults with hearing loss relative to those with no hearing loss, the association was found only in those who did not use hearing aids; those with hearing loss who used hearing aids did not have significantly poorer cognition than those with no hearing loss (Ray et al., 2018). An analysis of data from the Health and Retirement Study, which has tracked a group aged 50 and older since 1992, found that the decline in episodic memory scores slowed significantly after people with hearing problems began using hearing aids (Maharani et al., 2018).

A large meta-analysis calculated that the use of hearing aids by individuals with hearing loss decreased the risks of long-term cognitive decline by 19 percent (Yeo et al., 2023). Furthermore, this same study noted that using hearing aids to restore hearing in those with hearing loss was associated in the short term with a 3 percent improvement in scores on tests assessing general cognition (Yeo et al., 2023). However, there are inherent limitations to using observational literature to explore the impact of hearing intervention on modifying the association between hearing loss and cognitive decline (Pichora-Fuller, 2023; Reuben et al., 2024). Hearing intervention is non-pharmacologic and requires counseling, consistent maintenance, and persistent use, which is difficult to capture in epidemiologic observational studies. More importantly, hearing aid ownership and use, even in countries that cover hearing care, is strongly associated with socioeconomic factors that are also protective from cognitive decline, including income, education level, and race/ethnicity (Bessen et al., 2024; Reed et al., 2021). Prospective intervention studies are required to balance confounding. A pilot study of adults randomized to either a best practices hearing intervention group, which received hearing aids and associated services, or an active-control aging intervention group found that there was not clear efficacy after 6 months and hypothesized that longer hearing treatment would be needed to see the full effects (Deal et al., 2017). The full-trial follow-on to that pilot, a large randomized controlled trial (n=977) of adults aged 70–84 with untreated hearing loss, found no difference in cognitive decline over a 3-year period between those given hearing aids and associative services compared with an active control group given health education (Lin et al., 2023). More trials are needed to understand if hearing intervention delays cognitive decline and in which populations it is most effective.

Despite the body of evidence suggesting a possible connection between hearing loss and cognitive decline, the potential mechanisms for mediating that connection have not been well studied (Lazar et al., 2021). One proposed model suggests a role for both social and physiological factors (Rutherford et al., 2018). At the social level, hearing loss could lead adults to avoid situations where they have difficulty hearing or communicating, and the resulting social isolation and loneliness could lead to cognitive decline (Rutherford et al., 2018). At the physiological level, the reduced neural activation in auditory pathways caused by hearing loss could lead to dysfunction in auditory–limbic connections and atrophy in certain frontal brain regions, which in turn could reduce cognitive reserve and increase executive dysfunction, resulting in cognitive decline (Rutherford et al., 2018). One group that carried out a meta-analysis of the connection between hearing loss and cognitive impairment pointed to impaired verbal communication and vascular dysfunction as potential contributing factors (Loughrey et al., 2018).

An analysis of data from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing offered some support for the role of social effects (Maharani et al., 2019). Using episodic memory as a measure of cognitive function, the researchers found that hearing impairment had a significant effect on episodic memory and that this effect was partly mediated by loneliness and social isolation. However, further research will be required before it is clear how hearing loss in older adults may lead to cognitive decline, which older adults with hearing loss are most at risk, and whether hearing interventions can slow cognitive decline or reduce cognitive impairment. The connections among cognition, hearing loss, and hearing treatment are currently garnering a significant amount of attention by researchers, which may lead to more robust evidence for future consideration.

Conclusion 5-19: While recent literature suggests an association between hearing loss and cognition, cognition does not rise to the level of a core outcome at this time for several reasons. First, there is inconsistency in the cognitive construct being measured and the measures used in research. Second, potential concerns on the significance of risk and intervention effects at the individual versus population level exist. Third, cognitive decline is a distal outcome to hearing care, associated via proposed mediators that also could be measured (e.g., social connections, participation in activities), but there is a lack of key supporting data from mediation analyses and treatment effects on mediators. Fourth, questions remain on the effect of hearing intervention on cognitive decline, given the deep limitations of observational literature in this space and the null overall finding in the only powered randomized clinical trial.

Conclusion 5-20: Evidence on the connection between cognition and hearing intervention is evolving. While hearing care may cause minimal harm and could potentially benefit cognition, more research is needed to justify cognition as a core outcome. This includes studies with consistent definitions and measures, studies to determine the mechanism of impact, and studies that more consistently demonstrate the ability of interventions to reduce cognitive decline.

Quality of Life7

Quality of life (QoL) and health-related QoL are important to patients and individuals. QoL is a broad term that refers to an individual’s subjective

___________________

7 The committee emphasizes that this outcome is primarily focused on overall QoL and not the narrower health-related QoL, though both overlap with many other outcomes defined in this chapter.

well-being and ability to lead a fulfilling life. Teoli and Bhardwaj (2023) define it as “a concept which aims to capture the well-being, whether of a population or individual, regarding both positive and negative elements within the entirety of their existence at a specific point in time” and they note that common facets of QoL include such things as physical and mental health, relationships, work environment, social status, wealth, a sense of security and safety, freedom, social belonging, and physical surroundings. Their definition is just one among many that have been offered by various individuals and organizations (Barofsky, 2012; Boggatz, 2016; WHO, 2012). Health-related QoL refers to the aspects of QoL that relate only to health (Yin et al., 2016), and researchers have also developed various measures of QoL related to specific diseases or disorders, such as hearing-related QoL. This section focuses mainly on the overarching concept of QoL, with some additional consideration of health-related QoL and, specifically, hearing-related QoL.

For several decades researchers have studied the relationship between hearing loss and QoL and have generally found that hearing loss is associated with a decrease in QoL, while improved hearing through hearing aids and other hearing health interventions is associated with improved QoL (Borre et al., 2023; Brodie et al., 2018; Choi et al., 2024; Ciorba et al., 2012; Humes, 2021; Manrique-Huarte et al., 2016; Mulrow et al., 1990; Nordvik et al., 2018; Tseng et al., 2018). Intuitively that makes good sense, given the many important roles that hearing plays—in conversations with other people; in awareness of one’s environment; in the enjoyment of music, movies, television shows, and other forms of entertainment; and so on. But on closer inspection, and for a number of reasons, the connection between hearing and QoL is not as clear as it would seem.

To begin with, there is no agreement on just what QoL means (Barofsky, 2012). It is an inherently subjective property, and two people in exactly the same circumstances may judge their QoL very differently, just as an individual’s perception of his or her QoL may change over time as perceptions of what is important change. As Teoli and Bhardwaj (2023) commented, “While there is no shortage of textbook definitions, perhaps the most accurate meaning of QoL is the definition the patient provides when sitting across from their clinician.”

A closely related issue—and one that is more relevant to this report—is that there is no agreement on the best way to measure QoL (Kaplan and Hays, 2022; Pequeno et al., 2020). Some of the earliest measures focused on generic QoL, asking individuals to rate their satisfaction with such things as marriage and family, work, housing, and leisure activities (Bunge, 1975; Gillingham and Reece, 1979; Liu, 1975). Over time, broader measures of QoL were developed that included such factors as economic, political, and social well-being (IOM, 1989). And by the 1980s medical and public health researchers were using

more focused measures to study how overall health or issues related to specific diseases affected a patient’s QoL (Guyatt et al., 1993).

General health-related QoL measures, which focus on the physical and mental health aspects of QoL, are frequently used in epidemiological studies, population studies, health services research, and randomized clinical trials as well as for economic analyses and calculation of quality-adjusted life years (Kaplan and Hays, 2022). Many measures of health-related QoL have been developed. However, unlike in Europe and Canada, researchers in the United States have not settled on a single measure of health-related QoL, so U.S. datasets often have different measures, making the data difficult to compare or combine (Kaplan and Hays, 2022).

QoL measures also have been developed specifically to focus on particular diseases or functional areas. In the case of hearing loss, three of the most common are the HHIE, the Hearing Handicap Inventory for Adults (HHIA), and International Outcomes Inventory—Hearing Aids (IOI-HA), which is used to measure improvement in QoL factors resulting from the use of hearing aids (Ciorba et al., 2012). Additionally, WHO’s Disability Assessment Scale II (WHODAS II) assesses functioning across the following domains: communication, mobility, self-care, interpersonal, life activities, and participation (Chisolm et al., 2005). Convergent validity analysis found that WHODAS II was moderately correlated with the Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit, significantly correlated with the HHIE, and significantly correlated with the Short Form-36 for Veterans (SF-36 V). However, again, there is no agreed-upon standard. Two measures specific to hearing loss in adults include the Subjective Well-Being of Older Adults with Hearing Loss (SWB-HL) (Humes, 2021) and the Impact of Hearing Loss Inventory Tool (IHEAR-IT) (Stika and Hays, 2016). However, there has only been limited evaluation of these measures to date.

A major issue for hearing researchers is that different QoL measures vary in their ability to capture changes related to hearing interventions. A systematic review of research studying the effects of the treatment (i.e., hearing aids and cochlear implants) for hearing loss on health-related QoL showed that studies using certain measures—Health Utilities Index 2 and 3 (HUI2, HUI3), the Visual Analog Scale, and Time Trade-Off—generally found that treatment of hearing loss led to improvements in health-related QoL, while those using other measures, such as the European Quality of Life 5 Dimension (EQ-5D) and Short Form 6 Dimension (SF-6D), found little to no benefit (Borre et al., 2023). Borre and colleagues (2023) concluded,

This suggests that the EQ-5D and SF-6D do not adequately detect benefits related to hearing and communication, especially considering several studies used multiple measures in the same patients and found disparate results between measures. (p. 477)

A key to this difference may be found in the domains covered by the different measures. For example, the HUI2 and HUI3 include elements of cognition and emotion (along with some other general measures). The self-administered Quality of Well-Being Scale (QWB-SA) includes social activity. Chisolm and colleagues (2007) found that “hearing aids improve health-related QoL by reducing psychological, social, and emotional effects of hearing loss” (p. 151). They conclude that more research is needed.

One thing that the research has made clear is that it is not possible to understand the effects of hearing loss on an individual’s QoL without context; it is not enough to just know the details about the person’s hearing. While measurement of QoL requires a clear definition and the development of measures that can achieve adequate psychometric properties for their intended purpose, understanding a person’s level of QoL requires taking a number of factors into account whose importance will vary with the individual and with circumstances. One could list hundreds of these factors, but the following list assembled by WHO includes many, if not all, of the major ones, divided into six domains (WHO, 2012):

- Physical: pain and discomfort, energy and fatigue, sexual activity, sleep and rest, sensory functions

- Psychological: positive feelings; thinking, learning, memory, and concentration; self-esteem; bodily image and appearance; negative feelings

- Level of independence: mobility, activities of daily living, dependence on medical substances and medical aids, dependence on nonmedicinal substances such as alcohol or tobacco or drugs, communication capacity, work capacity

- Social relationships: personal relationships, social support, activities as provider or supporter

- Environment: freedom, physical safety, and security; home environment; work satisfaction; financial resources; accessibility and quality of health and social care; opportunities for acquiring new abilities and skills; participation in and opportunities for recreation and leisure activities; the physical environment, including such things as climate, pollution, noise, and traffic; transport

- Spirituality, religion, and personal beliefs

Conclusion 5-21: While QoL is meaningful for adults with hearing difficulties in both clinical and research settings, it is a complex outcome that is inconsistently defined and measured and therefore does not rise to the level of a core outcome at this time. Health-related QoL, a subset of QoL, is better defined and has been measured in many studies of

hearing intervention, but the results of these studies are inconsistent. Therefore, health-related QoL does not rise to the level of a core outcome at this time. However, as noted earlier, the committee selected hearing-related psychosocial health, a key element of QoL and health-related QOL, as a core outcome.

Socioeconomic Effects

A small literature examines the socioeconomic effects of untreated hearing loss (beyond the cost of health care). The first area of research focuses on the effect on income. Socioeconomic factors in this context do not include the cost of treatment, but rather the socioeconomic status of the individual with hearing loss and those factors specifically related to the experience of hearing loss. The committee recognizes the many access issues related to the cost of hearing health interventions, but these concerns are beyond the scope of this report.

One nationally representative study including adults ages 20 to 69 found after controlling for education, age, sex, and race, individuals with hearing loss were 1.58 times more likely to have low income and 1.98 times more likely to be unemployed or underemployed than normal-hearing individuals (Emmett and Francis, 2015). The authors noted that these are cross-sectional data that cannot be used to establish causation and pointed to the need for longitudinal studies. This same study further found that individuals with hearing loss were 3.21 times as likely to have low educational attainment than those without hearing loss (Emmett and Francis, 2015). Adults with hearing loss retire earlier than adults without hearing loss, which can cause financial stress (Malcolm et al., 2022).

A second area of study focuses on direct and indirect health care costs. Wells and colleagues (2019) concluded that individuals with untreated severe hearing loss had higher annual medical costs ($14,349) than those without hearing loss ($12,118). These are medical costs separate from the cost associated with the treatment of hearing loss. Reed and colleagues found an association between untreated hearing loss and increased health care expenses at 2, 5, and 10 years after diagnosis (Reed et al., 2019). A longitudinal study that included individuals on private U.S. health insurance plans or Medicaid Advantage plans who had filed administrative claims found that at 10 years people with untreated hearing loss had 50 percent more hospital stays, 44 percent higher readmission rates (within 30 days), and attended on average 52 more outpatient visits over a 10-year period (Reed et al., 2019). Overall, individuals with hearing loss spent an average $22,434 more on health care than individuals without hearing loss over that 10-year period (Reed et al., 2019).

As noted in the 2016 National Academies study Hearing Health Care for Adults:

Mohr and colleagues (2000) focused on severe to profound hearing loss and estimated the costs over a lifetime to an individual to be $297,000 (averaged across age at onset), with most of the losses (67 percent) due to reduced work productivity. . . . Ruben (2000) used several sources of labor and disability data to look at the economic effects of communications disorders, with some data focused on hearing loss, and found negative impacts of hearing loss on individual income and significant underemployment of individuals with hearing loss. Stucky and colleagues (2010) used a simulation model based on national estimates of the prevalence of hearing loss in individuals age 65 years and older across the range of hearing loss, as well as several sources of economic data, and estimated that the total costs of first-year treatment of hearing loss in 2002 were approximately $1,292 per person, or $8.2 billion nationally, and projected that by 2030 these costs would increase to approximately $51.4 billion nationally. They also estimated the 2002 lost productivity costs attributable to hearing loss in this age group to be approximately $1.4 billion nationally. Simpson and colleagues (2016) examined health care cost data from privately insured adults age 55 to 64 years and found higher health care costs for a number of chronic health conditions for individuals with a diagnostic code for hearing loss as compared with a matched group without that diagnostic code. (NASEM, 2016, p. 62–63)