Measuring Meaningful Outcomes for Adult Hearing Health Interventions (2025)

Chapter: 7 Dissemination and Implementation

7

Dissemination and Implementation

As noted in Chapter 3, core outcome sets (COS) can enhance standardization and in turn help improve the usefulness of findings in health care research and clinical assessments to ultimately improve patient outcomes. However, these benefits are only realized if a COS is used. COS uptake in clinical research using randomized controlled trials varies substantially depending on the condition, and uptake has been found to be low in the development of practice guidelines (Hughes et al., 2021; Rhodes et al., 2024). While studies describing protocols used to develop, disseminate, and implement COSs are readily identified in the literature, analyses of the effectiveness of the dissemination and implementation protocols of those COSs are more limited (Bellucci et al., 2021; South et al., 2024). As noted in Chapter 3, one often cited strategy for increasing uptake of a COS is developing consensus during the process of creating the COS by engaging with those who will use it. An examination of the available literature related to barriers and facilitators for COS uptake, as well as dissemination and implementation in other areas such as evidence-based practice, can provide useful insights.

DISSEMINATION AND IMPLEMENTATION BASICS

Dissemination and implementation are often discussed collectively. However, dissemination and implementation are two separate but related areas. Dissemination refers to active efforts to spread information, typically research findings, to targeted audiences using planned strategies (Rabin et al., 2008).

Implementation refers to the process of translating that knowledge into action, typically in the form of adoption and integration of a given evidence-based practice, using planned strategies (Baumann et al., 2023; Rabin et al., 2008). Dissemination and implementation science is a growing field of research that investigates and develops approaches to increase uptake of research innovations and the resulting evidence-based interventions (Rabin et al., 2008; Yi et al., 2022). Both dissemination and implementation strategies seek to create a change in behavior that leads to uptake of a new practice, in this case use of the COS.

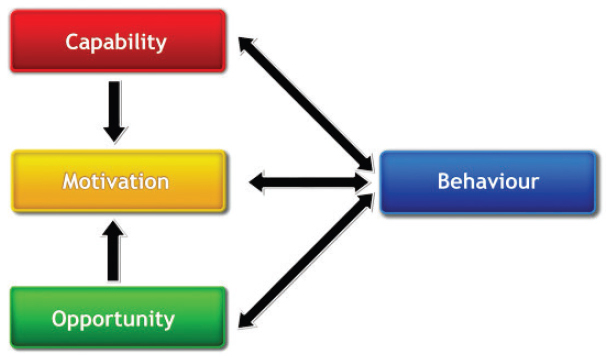

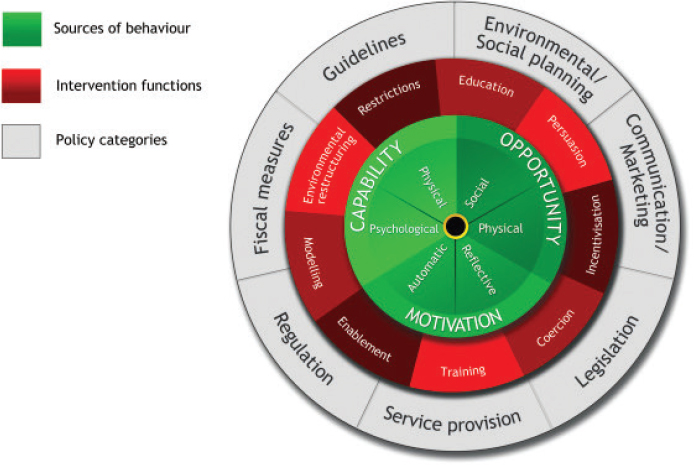

Dissemination strategies lay the foundation for, and contribute to, implementation strategies to support COS uptake. Therefore, dissemination and implementation processes are often guided by behavior science theory, such as the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation-Behavior (COM-B) model (see Figure 7-1) and the Behavior Change Wheel (see Figure 7-2) (Matvienko-Sikar et al., 2024; Michie et al., 2011).

The COM-B model posits that for a behavior to occur, an individual must have the capability, opportunity, and motivation to carry out that behavior (Matvienko-Sikar et al., 2024). Dissemination and implementation programs usually engage one or a combination of commonly used staged models, such as the reach, adoption, implementation, and maintenance (RE-AIM) framework to inform the selection of, and organize deployment of, strategies (Glasgow et al., 2019). A staged approach highlights the importance of dissemination and implementation activities beyond the point of initial uptake to support sustainable adoption (Proctor et al., 2013; Rabin et al., 2008).

NOTE: COM-B = Capability, Opportunity, Motivation-Behavior.

SOURCE: Michie et al., 2011. CC BY 2.0.

SOURCE: Michie et al., 2011. CC BY 2.0.

DISSEMINATION AND IMPLEMENTATION FOR CORE OUTCOME SET UPTAKE

Matvienko and colleagues (2024) applied the COM-B model and concepts from the Behavior Change Wheel to barriers and facilitators to the use of COSs commonly cited in studies, examining uptake by researchers to identify potential strategies for facilitating the uptake of COSs (Matvienko-Sikar et al., 2024). Table 7-1 highlights several facilitators and barriers specific to the uptake of a COS.

Improving Awareness of the COS

Several studies investigating the uptake of COSs have noted that researchers who were knowledgeable about COSs in general or for a specific condition were more likely to use a COS in their studies (Bellucci et al., 2021; Hughes et al., 2022). Additionally, those studies found that lack of awareness of the COS for a specific condition and lack of knowledge in general about COSs, as well as about the rigorous methodology involved in their development, were frequently cited as a reason for not using a COS (Bellucci et al., 2021; Hughes et al., 2021, 2022; Kirkham and Williamson, 2022; Saldanha et al., 2024). This highlights the importance

| Barriers | Facilitators |

|---|---|

|

|

NOTE: COS = Core Outcome Set.

SOURCE: Modified from Matvienko-Sikar et al., 2024. CC BY 4.0.

of first engaging in a robust dissemination strategy to ensure researchers, hearing health professionals, clinicians of first contact (e.g., primary care physicians, advanced practice registered nurses), and patients have the necessary knowledge of this COS for adult hearing health.

In 2013, a large systematic review by McCormack and colleagues (2013) sought to identify the most effective approaches to dissemination of research findings to inform evidence-based practice. That review, as well as a more recent large systematic review from South and colleagues (2024), found that multicomponent approaches that included some combination of strategies to improve the reach of information to multiple audiences and settings, strategies to increase motivation to use the information,

or strategies to improve the ability to use the information were generally most effective (McCormack et al., 2013; South et al., 2024).

Systematic reviews have found that while the effect size was small, multicomponent approaches that include academic detailing (also referred to as educational outreach) were most often identified in the literature as having a positive effect on changing clinical practice (McCormack et al., 2013; O’Brien et al., 2007; South et al., 2024; Tomasone et al., 2020). Academic detailing is derived from the detailing approach used by pharmaceutical sales representatives in which they engaged in face-to-face engagement with physicians to promote prescription of certain drugs (Fischer, 2016). It uses principles of various models of behavior change in direct outreach and engagement with health care professionals to deliver evidence-based information to promote the adoption of a recommended change in clinical practice (Fischer, 2016; O’Brien et al., 2007). Key components of effective academic detailing (in general) include (Soumerai and Avorn, 1990):

- Conducting interviews with clinicians to determine their baseline knowledge and motivations for using their existing practice patterns (in this case outcome measurements);

- Defining specific educational and behavioral objectives for the academic detailing program;

- Focusing outreach efforts on specific categories of clinicians and relevant opinion leaders;

- Establishing credibility by referencing information from unbiased and authoritative sources, collaborating with respected organizations, and presenting diverse perspectives on any directly relevant controversial issues;

- Creating succinct educational materials that include graphics;

- Emphasizing and repeating the key messages during outreach interactions; and

- Using positive reinforcement during follow-up interactions.

Studies of academic detailing programs found the strategy effectively increased uptake of recommendations for changes in practice such as appropriate prescribing of opioids and naloxone, use of prescription monitoring programs, diabetes care in the primary care setting, managing behavioral symptoms of dementia, and others (Fischer, 2016; Kulbokas et al., 2021; Walaszek et al., 2023).

Conclusion 7-1: A robust multicomponent dissemination strategy that includes educational outreach can help ensure all key partners have the necessary knowledge of the COS (and corresponding measures).

Examples of Successful Strategies to Enhance Uptake of a COS

In terms of specific examples of successful dissemination and implementation strategies to enhance COS uptake in other fields, examinations of data from ClinicalTrials.gov and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform found that the COS for rheumatoid arthritis has had particularly high uptake (Kirkham et al., 2017). Given the historically high uptake of the rheumatoid arthritis COS developed by the organization Outcome Measures in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trials, now referred to as Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT), it is reasonable to consider their strategies for insight into applicable best practices.

The OMERACT organization itself is likely an important tool to support COS uptake. It serves as a central entity that has taken responsibility for developing and updating COSs, as well as their dissemination and implementation. Many of those strategies echo the components of effective academic detailing. The rheumatoid arthritis COS dissemination has been supported by key strategies to establish its credibility. One key strategy is the establishment of the OMERACT organization itself, which at its inception was affiliated with the International League of Associations of Rheumatology, a well-known and respected organization in the field (Tugwell et al., 2007). Additionally, the organization’s first several conferences were hosted by the World Health Organization at its headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland (Tugwell et al., 2007). OMERACT’s founders and current committees and working groups consist of highly regarded thought leaders and experts in rheumatology.

OMERACT uses a multicomponent education approach that supports dissemination of COSs. Working groups, which analyze evidence from research and conduct reviews that often lead to an updated or new COS, publish their work in respected professional journals well known to the professionals engaged in rheumatoid arthritis research and care. OMERACT maintains a website that includes a handbook that uses text and infographics to explain its COSs and the methodology used to develop them, a structured education program targeted at COS users, and information about past and upcoming events (OMERACT, 2024). In addition to OMERACT’s biannual conferences, committee leaders present at professional meetings for experts in related fields, such as neurology and radiology (Tugwell et al., 2007).

Because of the vast nature of implementation and dissemination science surrounding COSs, there is a need for continued research to further identify additional key facilitators and barriers to increasing the uptake of COSs in research and practice (Bellucci et al., 2021; South et al., 2024). A strong understanding of what makes an implementation framework successful allows for reproducible research and a clearer understanding of the findings

and lends itself to recommendations for practice and guideline development (Smith et al., 2020). Further research in this area will continue to guide researchers and practitioners in effective dissemination and implementation practices, which is necessary for the uptake of COSs.

Conclusion 7-2: More research is needed to better understand the key facilitators, barriers, and approaches to the uptake of a COS (and corresponding measures) in research and practice, both for uptake of COSs in general as well as specific strategies in hearing health.

Conclusion 7-3: Having a centralized entity take responsibility for developing and updating the core outcome set is a highly effective strategy to encourage uptake.

STRATEGIES TO INCREASING THE UPTAKE OF A CORE OUTCOME SET FOR HEARING HEALTH OUTCOMES

Several strategies based on dissemination and implementation science, findings from research into barriers and facilitators to COS uptake, and examples from other successful endeavors can be applied to support the uptake of a hearing health COS.

The committee hosted a public webinar to hear directly from representatives of professional organizations including the American Academy of Audiology (AAA), the Academy of Doctors of Audiology (ADA), the American Speech-Language Hearing Society (ASHA), and the International Hearing Society (IHS).1 The webinar focused on these organizations’ experiences with disseminating new information to their constituencies to learn about which approaches have worked best to improve awareness and encourage the implementation of new practices as well as to learn about the challenges that these organizations face, particularly as they relate to outcome measurement (see Box 7-1).

Education

Dissemination and implementation strategies that target training and education are important for addressing many of the barriers to using COSs that have been identified in the literature. As previously noted, a multicomponent approach that includes academic detailing has been found beneficial. One-on-one outreach is inefficient and not cost-effective. Alternatively, group educational events such as conferences and workshops have been

___________________

1 The webinar recording can be accessed at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/43762_10-2024_meaningful-outcome-measures-in-adult-hearing-health-care-webinar-3.

BOX 7-1

Approaches to Dissemination and Implementation of New Information in Hearing Health

“We’re instructing on [outcome measurement] in both our entry level and our advanced education that’s available to our membership and to our customers at large [. . .] We produce what’s called our distance learning course for hearing health care professionals, which is the book work that an apprenticeship will do in conjunction with their hands-on training. It guides their trainer as to what they should be teaching them and trying to help make sure that the trainer and the trainee are both up to date on best practices. What we have found is that given that the vast majority of new hearing aid specialists are using the IHS materials, we have a huge opportunity there to be disseminating information.”

—Sierra Sharpe, IHS

“We try to focus very heavily on making sure our members can have both some form of written material that they can reference at any time, day or night . . . but we also know that having that interaction with live webinars and live presentations can be helpful as well.”

—Alicia Spoor, ADA

“The implementation piece . . . is hard to know. It’s hard to measure, so we do ask our membership to give us some information when we do surveys about the practices that they use. If we ask something about how many of you use real-ear verification, we’re depending on them to tell us that back. And we’re also depending upon the sampling, and so depending on what that sample is and depending on who answers it. It’s hard to know about the implementation piece, to really have a good grasp on how many of our members are implementing a practice that the community feels is evidence-based and needs to be happening.”

—Donna Smiley, ASHA

“So how do we get that in front of people’s faces? Presentations at conferences, particularly our annual conference, has been a big point, especially in some of the more highlighted, featured session talks where they have a large attendance, and people can pick up those new concepts or new guidelines. Other things like publications, whether it’s our journal or our magazine, Audiology Today, helping to get it in front of people. Also targeting specific stakeholders. [. . .] as well as working with other audiology organizations, particularly state organizations to help keep them involved and keep them aware of what’s going on at the national level.”

—Patricia Gaffney, AAA

__________________

These quotes were collected from the committee’s webinars.

identified as a beneficial approach (Forsetlund et al., 2021). These convenings may be led by the institution responsible for developing a COS measurement instrument, such as the PROMIS Health Organization, which holds events to train health care professionals in use of its Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS) for measurement of person-centered outcomes (PROMIS Health Organization, 2024).

As noted in Chapter 3, patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) gather data directly from patients about their health status and outcomes. These measures seek feedback on general outcomes, meaning “examine aspects that fit a variety of different conditions and allow comparison across these various medical conditions,” or disease-specific outcomes, meaning measures that are “designed to identify specific symptoms and their impact on the function of those specific conditions” (Weldring and Smith, 2013, p. 63). PROMs have not only helped shape clinical decision making and contributed to patient-centered care, but they also offer valuable insight into symptoms and functioning that may have been missed by traditional clinical measures, allowing for a more holistic view (Adeghe et al., 2024). Presentations and workshops can also be embedded in relevant professional organizations’ scientific meetings.

Webinars and other virtual learning options can be used to deliver education about COSs and their use in a convenient manner. OMERACT has an educational initiative referred to as OMER-ED that includes courses about the different rheumatoid arthritis COSs, the development process for its COS, and how to select the correct rheumatoid arthritis COS instrument (OMERACT, 2025). A similar virtual educational platform could be developed for the hearing health COS, with modules tailored to relevant audiences and accessibility needs.

Conclusion 7-4: Conferences, workshops, and webinars (and other virtual learning options) are effective strategies for enhancing education about COSs (and corresponding measures).

Regulation and Incentives

Institutions engaged in funding and regulating research can support the uptake of COSs. The International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number Registry website, which includes studies beyond randomized controlled trials (RCTs), advises researchers to identify outcome measures in their applications and refers them to the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) Initiative (BMC, 2025). Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) guidelines encourage researchers to identify relevant COSs by consulting COMET (Chan et al., 2013). Cochrane’s author guidelines encourage review authors to use

OMERACT COSs (Tugwell et al., 2007). The Health Research Authority of the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) includes information about the use of COSs in the best practices section of their website and provides a link to the COMET Initiative for additional education and support (NHS, 2019).

Research funding sources may create an incentive to use COSs. A study of OMERACT COS uptake in clinical trials registered on ClinicalTrials.gov and the World Health Organization-International Clinical Trials Registry Platform found that industry-funded trials were more likely to use a COS (Kirkham et al., 2019). This also suggests commercial research funders are an important group to include in educational outreach efforts to increase uptake of COSs. Notably, that study also found that registered clinical trials that were not commercially funded were less likely to plan to measure those COSs. OMERACT is currently seeking to increase collaboration with regulatory bodies, such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to ensure its methodologies are consistent with FDA regulations (OMERACT, 2023). Academic detailing efforts that extend to regulators and funding agencies can increase awareness of the hearing health COS, which is an important first step toward a regulatory or funding requirement. There is precedent for agencies requiring the use of COSs in studies they support. The National Institutes of Health Helping to End Addiction Long-term (HEAL) Initiative developed a set of patient-reported core outcomes related to pain and requires clinical trials that are part of that initiative to use those COSs.2

One additional driver for increasing uptake of COSs in the clinical setting could be the growing interest in value-based care. Value-based care emphasizes measuring patient-reported outcomes, which share similarities with COSs (Kearney et al., 2023). Because of the overlap in patient-centered outcome measures (the measures developed and used for value-based health care) and COSs, requiring the use of COSs for value-based health care practices could be an avenue for consistent use of COSs.

Also, the implementation of COSs into patient portals integrated with electronic health records (EHR) systems could allow for a streamlined approach to incorporate the Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit (APHAB) and the Revised Hearing Handicap Inventory (RHHI) into the health record system. Integrating COSs into EHR systems could allow for COSs to become routine data collection and in turn inform future research and guideline development (Dodd et al., 2020). EHR systems have been widely implemented into the health care system to increase the ease of

___________________

2 For more information, see https://rethinkingclinicaltrials.org/chapters/conduct/real-world-evidence-patient-reported-outcomes-pros/nih-heal-fda-and-other-core-outcome-sets (accessed October 9, 2024).

patient data collection and transfer (CMS, 2024). Using the systems already in practice could lead to the uptake of COSs.

Conclusion 7-5: Required use of COSs (and corresponding measures) by funders of research and insurers (when measures are required), as well as integration of the COSs into EHRs, can create effective incentives for the use of the COSs.

Data Repositories

At the 2024 Midwinter Meeting of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology, the topic of “big data” was discussed in an organized symposium. “Good Data in, Big Data out” presentations included:

- Standardization of Threshold and Supra-Threshold Measures in Clinical Trials Assessing Investigational Inner Ear Medicines (Le Prell, 2024).

- The Role of Consistent Clinical Practice Approaches for Data-Informed Hearing Care (Poling, 2024).

- Here Hear Share (Hertzano, 2024).

- From Club Good to Pure Public Good: Some Barriers and Solutions to Sharing Health-Related Data (Cummings, 2024).

- Big Data, Big Possibilities (Reavis, 2024).

Of particular relevance to the topic of databases, Poling noted that standardizing data collection and integration practices can improve clinical processes and improve patient care delivery. In addition, she highlighted the need for consistency in clinical practices to allow for data harmonization and the ability to use the full potential of big data from clinical audiology. Hertzano followed, noting that audiology has yet to establish a unified approach for harmonizing, sharing, analyzing, and visualizing data, with no large audiometric databases. To address this unmet need, Hertzano presented her team’s efforts to develop a secure cloud-based platform, built upon the Probing Outcomes Data with Visual Analytics (POD-Vis) software, that can host hearing data. As noted in her meeting abstract, the development of this tool is led by the HearShare consortium, which includes Duke University, the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Mayo Clinic, Medical University of South Carolina, University of Maryland College Park, and the University of Maryland Baltimore. Collectively, these institutions have amassed a vast dataset that includes hearing thresholds, tympanometry, acoustic reflex thresholds, and speech audiometry (recognition scores in quiet and noise) from over 500,000 unique adult patients aged 18 years and above.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) broadly supports the sharing of data in an appropriate repository.3 NIDCD is highly supportive of data repositories (Tucci, 2023) and maintains a list of publicly available databases that NIDCD-funded scientists can access.4 Of note, NIH currently hosts a pediatric hearing database.5 Also worth noting is the NIH-supported gene Expression Analysis Resource (gEAR)6 database, which provides an example of a data repository that supports not only data submission but also display, analysis, and interrogation, with users able to customize their own data displays and compare their data to other uploaded datasets (Orvis et al., 2021). The gEAR database is highly relevant to hearing loss (Hertzano and Mahurkar, 2022; Taiber et al., 2022). Tools within gEAR have been used to investigate genes associated with adult onset hearing loss (Lewis et al., 2023) and age-related hearing loss (Schubert et al., 2022). There are a host of issues related to database development and data sharing (Eckert et al., 2023). Thus, centralized support from government and other organizations is essential to the success of data harmonization and data-sharing repositories

Conclusion 7-6: Centralized data repositories can help researchers and clinicians benchmark their use of the COS and corresponding measures, compare results, and allow for pooling of data.

FINDINGS

Finding 7-1: Dissemination refers to the active efforts taken to spread information; implementation refers to translating that information into action.

Finding 7-2: A combination of strategies is typically needed to encourage the uptake and use of new information.

Finding 7-3: Multicomponent approaches that include some combination of strategies to improve the reach of information to multiple audiences and settings, strategies to increase motivation to use the information, or strategies to improve the ability to use the information are generally most effective.

___________________

3 For more information see https://sharing.nih.gov/data-management-and-sharing-policy/sharing-scientific-data/repositories-for-sharing-scientific-data (accessed January 13, 2025).

4 For more information see https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/research/population-clinical-database-resources-nidcd-mission-areas#hearing (accessed January 13, 2025).

5 For more information see https://audgendb.github.io/ (accessed January 13, 2025).

6 For more information see https://umgear.org/ (accessed January 13, 2025).

Finding 7-4: Known facilitators to uptake of COSs include:

- Knowledge of the COS (including its purpose),

- Understanding how to use the COS and recognizing that its use does not preclude the use of other outcomes,

- Understanding that the COS addresses inconsistencies in outcomes measured in trials, and

- Understanding the rigor of the development of the COS.

Finding 7-5: Known barriers for uptake of COSs include:

- Lack of awareness,

- Costs,

- Measurement burden,

- Perception that the COS may not match the scope and specificity for planned trials,

- Perception that the COS limits opportunities for innovation of new outcomes, and

- Preference for continuing current practices.

Finding 7-6: Researchers who know about COSs are more likely to use them in their studies.

Finding 7-7: Successful mechanisms to encourage the uptake of a COS include having a central entity responsible for developing and updating the COS and hosting conferences on the topic. Key dissemination and implementation strategies include education, typically through educational outreach; conferences and training events; and regulation and funding incentives, such as required use by research funders or registries

RECOMMENDATIONS

The first step in encouraging adoption of the COS and corresponding measures includes engaging in a robust dissemination strategy to ensure that researchers, health care professionals, and adults with hearing difficulties have the necessary knowledge of the COS and its measures.

Recommendation 7-1: Health academic organizations and programs, professional organizations, researchers, and consumer groups should disseminate information about the importance of the core outcome set to clinicians of first contact (e.g., primary care clinicians), hearing health clinicians (e.g., students, audiologists, otolaryngologists), and adults with hearing difficulties.

Strategies for dissemination include providing information and training on the COS and corresponding measures through formal educational, clinical, and research-focused training programs, websites, meetings, continuing education, and webinars. The committee notes that disseminating this information to different partners will likely require a multipronged approach. The committee purposefully includes primary care and other clinicians of first contact among the targets of dissemination because these partners will often be the first to evaluate the concerns of patients reporting hearing difficulty and patients may ask questions regarding the COS. Furthermore, adults with hearing difficulties themselves need to be included in the dissemination efforts to encourage a whole health approach to care.

Dissemination of information alone, however, is insufficient to ensure the uptake of a COS. It will be important to develop strategies for creating incentives to use the COS and corresponding measures as well as strategies for alleviating burdens to its use. Such strategies can come from a variety of sources, including requirements for use in research, incorporation of the outcome measures into electronic health records, and use in value-based care.

Recommendation 7-2: To create incentives for the use of the core outcome set and corresponding measures the following should occur:

- Sponsors of research on hearing health interventions should require the use of the core outcome set and corresponding measures (at a minimum), unless scientifically justified for exclusion.

- Electronic health record (EHR) vendors should incorporate the Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit and Revised Hearing Handicap Inventory into EHRs.

- Insurers who require outcome measures should require the use of the recommended measures.

In particular, the committee notes that the recommended Words-in-Noise test (WIN) (see Chapter 6) is conducted through an audiometer and its results can be recorded in the EHR. The committee recommends the inclusion of the recommended self-report questionnaires (APHAB-Global and the RHHI) in the EHR both to allow for ease of use by the clinician and to enable patients to answer these questionnaires in advance of a clinical visit.

One of the main purposes of developing and using a COS and corresponding measures is to allow for the pooling of data, in part to compare the effectiveness of interventions, as well as develop a more robust evidence base that helps improve clinical care. The committee recognizes that NIH already has existing platforms for the centralized sharing of data.

Recommendation 7-3: To facilitate big data meta-analyses, the National Institutes of Health should develop a national database to allow

clinicians and researchers to benchmark the use of the core outcome set and corresponding measures, as well as their results.

One highly effective strategy for encouraging the uptake of COSs in other fields is having a central entity take responsibility for developing and updating the COS. The committee recognizes the importance of ensuring the consistency of what is measured and how it is measured over time. However, as new evidence emerges, the COS will need to be revisited. The purpose will not be to just add more core outcomes, but to consider which ones should remain part of the core, or which ones should be considered for supplemental measurement as appropriate. As noted in Chapters 4 and 5, several outcomes (e.g., quality of life, cognition, listening fatigue) are widely meaningful, but the evidence bases for the ability of hearing interventions to affect the outcomes are mixed and evolving. The committee notes that several federal agencies provide substantial funding and work in hearing health research and hearing health care delivery and therefore are well positioned to collaborate to support ongoing evaluation and support for a COS.

Recommendation 7-4: After an adequate level of new research has been gathered, the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Defense, and the Veterans Administration should collaborate to revisit the core outcome set.

Finally, while following the recommendations for dissemination and implementation of the COS and corresponding measures can help encourage uptake, there will still likely be gaps in understanding for which approaches work best for specific target audiences in the hearing health field. For example, tailoring the dissemination of information to various audiences will likely require research on specific strategies for each target population.

Recommendation 7-5: Sponsors of hearing health research should fund research on comprehensive implementation science approaches to identify additional key facilitators for and barriers to the uptake and use of the core outcome set and corresponding measures.

REFERENCES

Adeghe, E. P., C. A. Okolo, and O. T. Ojeyinka. 2024. The influence of patient-reported outcome measures on healthcare delivery: A review of methodologies and applications. OARJ of Biology and Pharmacy 10(02):013–021.

Baumann, A. A., R. C. Shelton, S. Kumanyika, and D. Haire-Joshu. 2023. Advancing healthcare equity through dissemination and implementation science. Health Services Research 58(Suppl 3):327–344.

Bellucci, C., K. Hughes, E. Toomey, P. R. Williamson, and K. Matvienko-Sikar. 2021. A survey of knowledge, perceptions and use of core outcome sets among clinical trialists. Trials 22(1):937.

BMC (BioMedCentral). 2025. ISRCTN Registry - The UK’s clinical study registry. https://www.isrctn.com/page/definitions#primaryOutcomeMeasures (accessed January 7, 2025).

Chan, A. W., J. M. Tetzlaff, P. C. Gøtzsche, D. G. Altman, H. Mann, J. A. Berlin, K. Dickersin, A. Hróbjartsson, K. F. Schulz, W. R. Parulekar, K. Krleza-Jeric, A. Laupacis, and D. Moher. 2013. Spirit 2013 explanation and elaboration: Guidance for protocols of clinical trials. British Medical Journal 346:e7586.

CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services). 2024. Electronic health records. https://www.cms.gov/priorities/key-initiatives/e-health/records (accessed December 19, 2024).

Cummings, M. 2024. From club good to pure public good: Some barriers and solutions to sharing health-related data. Paper presented at the 2024 Association for Research in Otolaryngology MidWinter Meeting, Orlando, FL.

Dodd, S., N. Harman, N. Taske, M. Minchin, T. Tan, and P. R. Williamson. 2020. Core outcome sets through the healthcare ecosystem: The case of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Trials 21(1): 570.

Eckert, M. A., F. T. Husain, D. M. P. Jayakody, W. Schlee, and C. R. Cederroth. 2023. An opportunity for constructing the future of data sharing in otolaryngology. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology 24(4):397–399.

Fischer, M. A. 2016. Academic detailing in diabetes: Using outreach education to improve the quality of care. Current Diabetes Reports 16(10):98.

Forsetlund, L., M. A. O’Brien, L. Forsén, L. M. Reinar, M. P. Okwen, T. Horsley, and C. J. Rose. 2021. Continuing education meetings and workshops: Effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 9(9):Cd003030.

Glasgow, R. E., S. M. Harden, B. Gaglio, B. Rabin, M. L. Smith, G. C. Porter, M. G. Ory, and P. A. Estabrooks. 2019. RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: Adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Frontiers in Public Health 7(64). https://doi.org/10.2289/fpubh.

Hertzano, R. 2024. Here Hear Share! Paper presented at the 2024 Association for Research in Otolaryngology MidWinter Meeting, Orlando, FL.

Hertzano, R., and A. Mahurkar. 2022. Advancing discovery in hearing research via biologist-friendly access to multi-omic data. Human Genetics 141(3):319–322.

Hughes, K. L., M. Clarke, and P. R. Williamson. 2021. A systematic review finds core outcome set uptake varies widely across different areas of health. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 129:114–123.

Hughes, K. L., P. R. Williamson, and B. Young. 2022. In-depth qualitative interviews identified barriers and facilitators that influenced chief investigators’ use of core outcome sets in randomised controlled trials. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 144:111–120.

Kearney, A., E. Gargon, J. W. Mitchell, S. Callaghan, F. Yameen, P. R. Williamson, and S. Dodd. 2023. A systematic review of studies reporting the development of core outcome sets for use in routine care. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 158:34–43.

Kirkham, J. J., and P. Williamson. 2022. Core outcome sets in medical research. BMJ Medicine 1(1):e000284.

Kirkham, J. J., M. Clarke, and P. R. Williamson. 2017. A methodological approach for assessing the uptake of core outcome sets using ClinicalTrials.gov: Findings from a review of randomised controlled trials of rheumatoid arthritis. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j2262.

Kirkham, J. J., M. Bracken, L. Hind, K. Pennington, M. Clarke, and P. R. Williamson. 2019. Industry funding was associated with increased use of core outcome sets. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 115:90–97.

Kulbokas, V., K. A. Hanson, M. H. Smart, M. R. Mandava, T. A. Lee, and A. S. Pickard. 2021. Academic detailing interventions for opioid-related outcomes: A scoping review. Drugs Context 10:2021-7-7.

Le Prell, C. 2024. Standardization of threshold and supra-threshold measures in clinical trials assessing investigational inner ear medicines. Paper presented at the 2024 Association for Research in Otolaryngology MidWinter Meeting, Orlando, FL.

Lewis, M. A., J. Schulte, L. Matthews, K. I. Vaden Jr., C. J. Steves, F. M. Williams, B. A. Schulte, J. R. Dubno, and K. P. Steel. 2023. Accurate phenotypic classification and exome sequencing allow identification of novel genes and variants associated with adult-onset hearing loss. PLoS Genetics 19(11):e1011058.

Matvienko-Sikar, K., S. Hussey, K. Mellor, M. Byrne, M. Clarke, J. J. Kirkham, J. Kottner, F. Quirke, I. J. Saldanha, V. Smith, E. Toomey, and P. R. Williamson. 2024. Using behavioral science to increase core outcome set use in trials. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 168:111285.

McCormack, L., S. Sheridan, M. Lewis, V. Boudewyns, C. L. Melvin, C. Kistler, L. J. Lux, K. Cullen, and K. N. Lohr. 2013. Communication and dissemination strategies to facilitate the use of health-related evidence. Evidence Report Technology Assessment 213:1–520.

Michie, S., M. M. van Stralen, and R. West. 2011. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science 6(52). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-42.

NHS (National Health Service). 2019. Outcome measures. https://www.hra.nhs.uk/planning-and-improving-research/best-practice/outcome-measures/ (accessed October 9, 2024).

O’Brien, M. A., S. Rogers, G. Jamtvedt, A. D. Oxman, J. Odgaard-Jensen, D. T. Kristoffersen, L. Forsetlund, D. Bainbridge, N. Freemantle, D. A. Davis, R. B. Haynes, and E. L. Harvey. 2007. Educational outreach visits: Effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007(4):Cd000409.

OMERACT (Outcome Measures in Rheumatology). 2023. 2023 year end report. Ottawa, Canada: OMERACT.

OMERACT. 2024. OMERACT: Outcome measures in rheumatology. https://omeract.org (accessed June 25, 2024).

OMERACT. 2025. OMER-ED. https://omeract.org/elearning/ (accessed January 7, 2025).

Orvis, J., B. Gottfried, J. Kancherla, R. S. Adkins, Y. Song, A. A. Dror, D. Olley, K. Rose, E. Chrysostomou, and M. C. Kelly. 2021. gEAR: gene Expression Analysis Resource portal for community-driven, multi-omic data exploration. Nature Methods 18(8):843–844.

Poling, G. 2024. The role of consistent clinical practice approaches for data-informed hearing care. Paper presented at the 2024 Association for Research in Otolaryngology MidWinter Meeting, Orlando, FL.

Proctor, E. K., B. J. Powell, and J. C. McMillen. 2013. Implementation strategies: Recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implementation Science 8(139). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-139.

PROMIS (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System) Health Organization. 2024. What is PROMIS. https://www.promishealth.org/57461-2 (accessed September 30, 2024).

Rabin, B. A., R. C. Brownson, D. Haire-Joshu, M. W. Kreuter, and N. L. Weaver. 2008. A glossary for dissemination and implementation research in health. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 14(2):117–123.

Reavis, K. 2024. Big data, big possibilities. Paper presented at the 2024 Association for Research in Otolaryngology MidWinter Meeting, Orlando, FL.

Rhodes, S., S. Dodd, S. Deckert, L. Vasanthan, R. Qiu, J. F. Rohde, I. D. Florez, J. Schmitt, R. Nieuwlaat, J. Kirkham, and P. R. Williamson. 2024. Representation of published core outcome sets in practice guidelines. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 169:111311.

Saldanha, I. J., K. L. Hughes, S. Dodd, T. Lasserson, J. J. Kirkham, Y. Wu, S. W. Lucas, and P. R. Williamson. 2024. Study found increasing use of core outcome sets in Cochrane Systematic Reviews and identified facilitators and barriers. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 169:111277.

Schubert, N. M., M. van Tuinen, and S. J. Pyott. 2022. Transcriptome-guided identification of drugs for repurposing to treat age-related hearing loss. Biomolecules 12(4):498.

Smith, J. D., D. H. Li, and M. R. Rafferty. 2020. The implementation research logic model: A method for planning, executing, reporting, and synthesizing implementation projects. Implementation Science 15(1):84.

Soumerai, S. B., and J. Avorn. 1990. Principles of educational outreach (‘academic detailing’) to improve clinical decision making. Journal of the American Medical Association 263(4):549–556.

South, A., J. V. Bailey, M. K. B. Parmar, and C. L. Vale. 2024. The effectiveness of interventions to disseminate the results of non-commercial randomised clinical trials to healthcare professionals: A systematic review. Implementation Science 19(1):8.

Taiber, S., K. Gwilliam, R. Hertzano, and K. B. Avraham. 2022. The genomics of auditory function and disease. Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics 23(1):275–299.

Tomasone, J. R., K. D. Kauffeldt, R. Chaudhary, and M. C. Brouwers. 2020. Effectiveness of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies on health care professionals’ behaviour and patient outcomes in the cancer care context: A systematic review. Implementation Science 15(1):41.

Tucci, D. L. 2023. NIDCD’s 5-year strategic plan describes scientific priorities and commitment to basic science. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology 24(3):265–268.

Tugwell, P., M. Boers, P. Brooks, L. Simon, V. Strand, and L. Idzerda. 2007. OMERACT: An international initiative to improve outcome measurement in rheumatology. Trials 8:38.

Walaszek, A., T. Albrecht, M. Schroeder, T. J. LeCaire, S. Houston, M. Recinos, and C. M. Carlsson. 2023. Using academic detailing to enhance the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of clinicians caring for persons with behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 24(12):1981–1983.

Weldring, T., and S. M. S. Smith. 2013. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). Health Services Insights 6:61–68.

Yi, J. A., A. Hakimi, and A. K. Vavra. 2022. Application of dissemination and implementation science frameworks to surgical research. Seminars in Vascular Surgery 35(4):456–463.