Breastfeeding in the United States: Strategies to Support Families and Achieve National Goals (2025)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

1

Introduction

Breastfeeding and human milk feeding are the physiological norm for humans and the reference standard for infant feeding and nutrition (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2022a; Meek et al., 2022; Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2023). Pérez-Escamilla et al. (2023) concluded that human infants and young children are most likely to survive and develop to their full potential when fed human milk from their mothers, in part “due to the dynamic and interactional nature of breastfeeding and the unique living properties of breastmilk” (p. 1). The U.S. Surgeon General, as well as prominent organizations of health professionals, concluded that the short- and long-term health and psychosocial benefits associated with breastfeeding make it a public health imperative in the United States (e.g., the American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP; Meek et al., 2022]; American College of Nurse-Midwives, 2022; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], 2023; American Public Health Association, 1981, 2000, 2007, 2011, 2013, 2014; Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses, 2021; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2011).

These organizations, along with scientific experts, have concluded that for almost all infants, breastfeeding remains the best source of early nutrition and immunological protection (CDC, 2022a; Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2023), reduces the odds of infant deaths (Li et al., 2022; Ware et al., 2023), and is associated with lifesaving protection for preterm infants at risk of

developing necrotizing enterocolitis1 (Lucas & Cole, 1990; Miller et al., 2018; Quigley et al., 2024; Sami et al., 2023). For example, infants who are breastfed “more” versus “less” may have a reduced risk of developing noncommunicable diseases such as asthma, otitis media, obesity in childhood, and childhood leukemia (Patnode et al., 2025). In addition, a protective association of breastfeeding has been found for infant mortality, including sudden infant death, rapid weight gain and growth, systolic blood pressure, severe respiratory and gastrointestinal infections in younger children, allergic rhinitis, malocclusion, inflammatory bowel disease, and type 1 diabetes (Patnode et al., 2025). There are also maternal health benefits associated with breastfeeding, including a reduced risk of developing certain chronic diseases such as breast and ovarian cancer, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension (Feltner et al., 2018), as well as important psychosocial benefits, such as opportunities for emotional bonding (HHS, 2011).

Previous research has identified that the health benefits of breastfeeding for mothers, infants, and children can be sustained across the life course and conferred to society at large by avoiding the negative economic cost consequences of suboptimal2 breastfeeding rates (Bartick et al., 2017; Jegier et al., 2024). Published models currently estimate the total costs of suboptimal breastfeeding rates in the United States to range from $17.2 billion to over $100 billion annually (Jegier et al., 2024; see Chapter 2).

CURRENT BREASTFEEDING RATES AND NATIONAL GOALS

In the United States, more than 3.5 million women give birth each year, and approximately 84% initiate breastfeeding (CDC, 2024a; Martin et al., 2024). Most mothers want to breastfeed, as evidenced by high initiation rates, and the intention3 to breastfeed is a strong predictor of breastfeeding initiation at birth (Borger et al., 2021; Odom et al., 2013). However, over half of mothers stop breastfeeding earlier than they desire (Díaz et al., 2023; Odom et al., 2013).

___________________

1 Necrotizing enterocolitis is the most common serious gastrointestinal disease affecting newborn infants, and it typically occurs in the second or third week of life in premature, infant formula-fed infants. It is characterized by inflammation or death of the tissue of the intestinal lining.

2 To avoid stigmatizing infant feeding decisions or outcomes, the committee employs the terms optimal and suboptimal, when possible, to describe breastfeeding rates and highlight that the locus of control extends beyond the breastfeeding dyad or family unit and is impacted by systems-level factors.

3 Breastfeeding intention, as measured in two dimensions by the Infant Feeding Intention scale, qualitatively measures a mother’s intended method of feeding her infant over time (i.e., duration of breastfeeding), as well as the exclusivity of that feeding (e.g., “only breastmilk”; Nommsen-Rivers & Dewey, 2009).

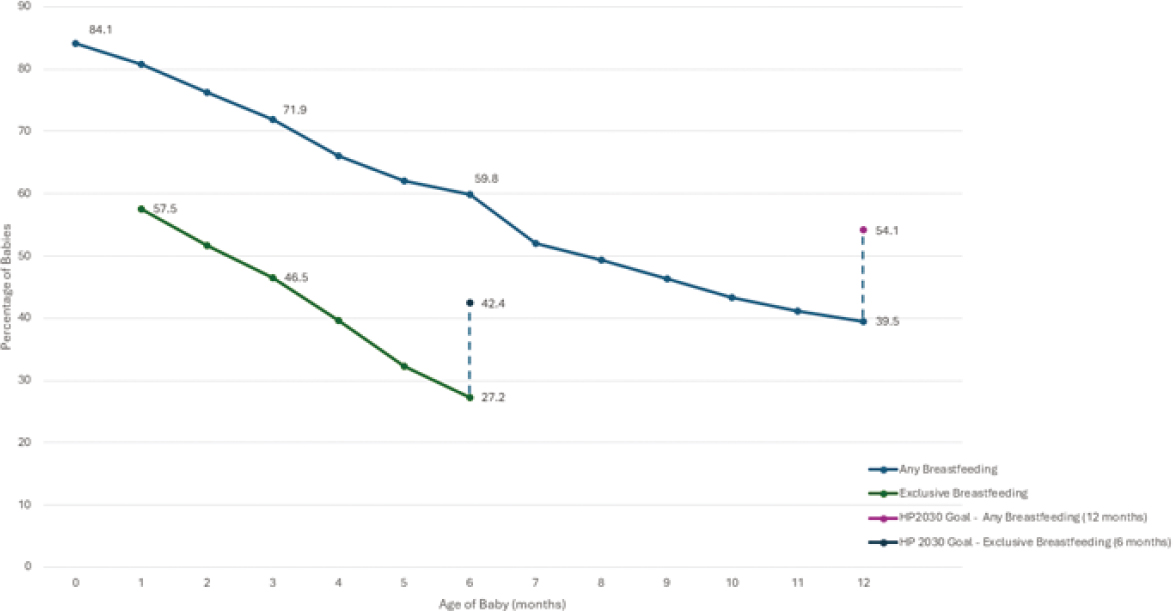

Despite high rates of intention and initiation, many mothers and families are unable to meet either their own goals or national breastfeeding recommendations4 for exclusivity and duration because of structural barriers. As shown in Figure 1-1, breastfeeding rates decline rapidly between three- and 12-months postpartum. For example, only 27% of babies are exclusively breastfed for the first six months of life, a percentage far below the recommendation of the U.S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) (CDC, 2022b). The DGA further recommends continuing breastfeeding and introducing appropriate complementary foods through at least 12 months of age (U.S. Department of Agriculture & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020). However, fewer than 40% of infants in the United States are still receiving human milk at 12 months (CDC, 2022b).

In alignment with the DGA recommendations, professional and public health organizations recommend that, when possible, breastfeeding be continued with appropriate complementary food for two years or as long as mutually desired (AAP [Meek et al., 2022]; ACOG, 2021, 2023; World Health Organization, 2023).

As noted in Figure 1-1, these national rates fall short of the Healthy People 2030 goals, which aim for 42.4% of infants to be exclusively breastfed through six months and 54.1% to receive any breastfeeding through 12 months (HHS, n.d.). The sharp decline in breastfeeding after birth reflects persistent challenges for families in meeting their breastfeeding goals, particularly around exclusivity and duration.

Breastfeeding rates are notably lower among certain groups, including Black women, American Indian/Alaska Native women, women with lower socioeconomic status, unmarried women, those living in rural areas, and younger mothers (Anstey et al., 2017; CDC, 2022b; Chiang et al., 2021). Many of these communities of mothers face disproportionate barriers to breastfeeding, such as the need to return to work early, inflexible job conditions, limited access to breastfeeding support services, and broader cultural and historical challenges (Asiodu et al., 2021; Griswold et al., 2018; Gyamfi et al., 2021; Kirksey, 2021; Lind et al., 2014; Louis-Jacques et al., 2017; Robinson et al., 2019; Segura-Pérez et al., 2021). These factors contribute to persistent variances in breastfeeding initiation, duration, and exclusivity.

In 2011, HHS released The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding. This document, building on the Blueprint for Action on Breastfeeding (HHS, 2000) and the Surgeon General’s Workshop on Breastfeeding and Human Lactation (HHS, 1984), highlighted key actions

___________________

4 The committee acknowledges that individual breastfeeding goals may differ from national recommendations and that not all mothers choose to, or are able to, breastfeed exclusively or for extended durations. Many factors may influence infant feeding goals or decisions. National guidelines exist to improve health outcomes over time, not to impose a singular standard of behavior. The committee emphasizes the importance of supporting all families in meeting their own infant feeding goals with dignity and respect.

NOTE: The committee chose to use the term human milk throughout the report; however, references to data reflect the terminology used in the original source material.

SOURCE: Data from CDC, 2022b.

for mothers and their families, communities, health care systems, and employers that would better support breastfeeding and eliminate existing barriers to sustaining breastfeeding.

Despite these efforts, the United States has been unable to meet Healthy People 2030’s modest breastfeeding targets. Raju (2023) notes that for infants born in 2019, 34 states continue to fall short of the Healthy People 2030 goals (see Chapter 3 for additional discussion). Gaps are greatest for subgroups facing structural barriers, including non-Hispanic Black families; participants in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); low-income households; unmarried parents; mothers under age 30; and those without any college education, according to an analysis of 2020 data (Noiman et al., 2024). Thus, the recommendations from The Surgeon General’s Call to Action continue to be relevant and timely. Substantial work remains to protect, promote, and support breastfeeding in the United States. These recommendations are particularly relevant in the context of high maternal and infant mortality and morbidity rates in the United States (Gunja et al., 2024).

PURPOSE AND SCOPE OF THIS STUDY

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (National Academies), through congressional mandate and sponsored by the HHS Office on Women’s Health, was asked to conduct a consensus study on policies, programs, and investments to better understand the landscape of breastfeeding promotion, initiation, and support across the United States; to provide an evidence-based analysis of the macroeconomic, social, and health costs and benefits of the current U.S. breastfeeding rates and goals; and to explore what is known about inequalities in breastfeeding rates and reducing racial, geographic, and income-related breastfeeding variances. Congresswoman Lucille Roybal-Allard (D-CA) and Congresswoman Jaime Herrera Beutler (R-WA) led the development of the committee’s charge in partnership with members of the Congressional Caucus on Maternity Care, who recognized the need for additional efforts to ensure that all families can access and receive comprehensive lactation support services in order to successfully initiate and maintain breastfeeding.

The committee’s statement of task was outlined by the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023 (Public Law 117-328) and Senate Report 118-84 accompanying the Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, and Related Agencies Appropriations Bill of 2024 to provide an “an evidence-based, non-partisan analysis of the macroeconomic, health, and social costs of U.S. breastfeeding rates and national breastfeeding goals” (Senate Report 118-84, accompanying the FY 2024 Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education Appropriations Bill, p. 238; see Box 1-1 for the committee’s full statement of task).

BOX 1-1

Statement of Task

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine will convene an ad hoc committee of experts to leverage available data and literature to conduct a consensus study on policies, programs, and investments to better understand the landscape of breastfeeding promotion, initiation, and support across the United States. The study will provide an evidence-based analysis of the macroeconomic, social, and health costs and benefits of the United States’ current breastfeeding rates and goals. The study will build on what is known about variances in breastfeeding rates and reducing differences in initiation and continuation. The committee will identify existing gaps in knowledge, areas for needed research, and will discuss challenges in data collection to address said gaps.

Based on available evidence, the committee will address the following issues and offer conclusions and recommendations:

- Best practices for clinicians, healthcare systems, insurers, and employers to encourage breastfeeding by new mothers and to support mothers who are currently breastfeeding, including mothers from populations and those experiencing poverty

- Macroeconomic, health, and social costs of current U.S. breastfeeding rates

- Funding mechanisms, state and federal policies, interventions, and systemic, cross-sector, or field innovations that can support exclusive breastfeeding through the first six months of life

- How insurers implement comprehensive lactation services, set standards to determine reimbursement rates for breastfeeding supplies and services, and provide coverage to help women breastfeed

- Contributing factors that impact breastfeeding rates and access to postpartum maternal care and supportive services (e.g., lactation consultant, doula support, registered dietitians)

- Leverage of available evidence to meet the Healthy People Maternal, Infant, and Child Health breastfeeding goals by 2030.

This report presents a road map for policy and practice changes necessary to ensure that all women have equal access to the knowledge, resources, and support to set and achieve their breastfeeding goals, with the aim of improving long-term health outcomes for the nation. The chapters that follow review proposed breastfeeding national strategies, setting by setting, and highlight promising policy and practice opportunities and future research priorities related to achieving this vision. In addition, the text highlights opportunities to address barriers and opportunities to scale up promising approaches. A variety of systems-level leaders and actors are identified throughout the report and in the recommendations. The committee’s overarching goal in this report is to provide accessible strategies for actionable change.

Report Terminology

The statement of task uses the term breastfeeding, which is most often used in scientific and practice-based literature. In this report, it refers to the dynamic physiological process and interactions that occur between a mother and infant, including (a) feeding at the breast as well as (b) expressed human milk feeding (e.g., the mother’s own milk, donor human milk, shared human milk, and purchased human milk; Rasmussen et al., 2017). Feeding at the breast and expressed human milk feeding may be exclusive or be in combination with alternatives such as commercial milk formula (e.g., infant formula).

The committee grappled with defining the terminology to be used throughout the report given the need for precision in response to the changing landscape of infant feeding. Box 1-2 defines this report’s key terms.

BOX 1-2

Report Definitions and Terminology

During its deliberations, the committee dedicated attention to the evolution of terms used to describe infant feeding. For clarity, these terms are defined and described below.

Breastfeeding is the process of feeding an infant or young child human milk directly from the breast or expressed or pumped milk from a bottle or other feeding device.

Colostrum is excreted from mammary glands in the breast during pregnancy and after childbirth until production of voluminous human milk begins, typically within three days after birth.

Direct breastfeeding is feeding human milk directly from the breast, typically from a mother to her child, which has demonstrated species and individual properties, such as microbiota and immunological development, that augment optimal health outcomes. These immunological benefits have not been established for direct breastfeeding via a “wet nurse,” or a lactating individual who is not the mother.

Exclusive breastfeeding is when an infant receives only breastmilk. Also called exclusive human milk feeding, it refers to when an infant consumes only human milk, not in combination with commercial milk formula or other foods or beverages (including water), except for medications or vitamin and mineral supplementation (Dewey et al., 2020).

Human milk is produced by the human mammary glands to feed infants and young children. It contains immune factors (e.g., IgA, lactoferrin, oligosaccharides), hormones, and other essential nutrients, and is sometimes referred to as breastmilk (Palmquist et al., 2019). This may be mother’s own or donor human milk.

Human milk expression or pumping is the practice, using hand or pump, to express human milk from the breast or chest (Labiner-Wolfe et al., 2008).

Breast pumps are a technology used to extract milk from the breast by creating a seal around the nipple and areolar complex and alternately applying and releasing suction, which expresses milk. One cycle is one round of combined suction and release. Types of pumps include manual, battery-powered, and electric pumps (U.S. Food and Drug Administration [FDA], 2018).

Human milk exchange includes human milk banking, human milk sharing, and markets in which human milk may be purchased or sold by individuals or commercial entities (Palmquist et al., 2019).

Pasteurized donor human milk is human milk that has been donated to a milk bank that is screened, tested, pooled, and pasteurized, and then dispensed to infants in need (Human Milk Banking Association of North America, 2024).

Combination feeding, otherwise known as mixed feeding, is feeding both human milk and commercial milk formula, but not other foods or beverages (i.e., complementary foods), such as cow’s milk or fruit juice (U.S. Department of Agriculture & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020).

The term commercial milk formula has been used primarily in the global research context as an umbrella term to describe infant formula, toddler milks, and related products (Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2023). The term emphasizes that these are commercially produced and marketed products. In the United States, the terms infant formula and toddler milk are most often used to refer to commercially available products.

Infant formula is defined by the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (201[z]) as “a food which purports to be or is represented for special dietary use solely as a food for infants by reason of its simulation of human milk or its suitability as a complete or partial substitute for human milk” (FDA, 2023).

Follow-up formula and milk are commercial products marketed to replace human milk and are labeled as a food intended for use in infants from 6 months onward as part of a weaning diet (Lutter et al., 2022).

Toddler milk is a nutrient-fortified beverage that often contains added sugars. These products are often marketed towards children aged 9–36 months as a transition milk or formula or weaning formula (Lott et al., 2019).

Prelacteal feeds are foods other than breastmilk offered during the first three days after delivery, encompassing a range of substances including water; milk; and milk-based substances, which may include commercial milk formula products (Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2023).

Complementary feedings are foods or beverages that are recommended to be introduced to infants at approximately age six months that are not human milk or infant formula (e.g., vegetables, fruits, cereals, meats) but may “complement” human milk or formula provided to the baby (CDC, 2024b). They may also be referred to as solid foods.

The committee also discussed how to clearly define the various types of lactation support providers, including the role and scope of community members and peer counselors who support lactation. Definitions and descriptions of these various terms are explored in Chapter 3, and education, training, and certification for providers in the health care setting are addressed in Chapter 6.

Study Scope

In accordance with the committee’s charge, this report provides an overview and description of previous research that identifies and quantifies the macroeconomic, social, and health costs and benefits of breastfeeding rates and goals. It reviews the evidence related to best practices for communities, clinicians or lactation support providers,5 health care systems, insurers, and employers, as well as policies, funding mechanisms, and innovations in the field that support breastfeeding. Moreover, as directed by the charge, it pays particular attention to variances in breastfeeding rates, as well as other contributing factors that influence breastfeeding rates among different populations. The report also notes limitations in the available evidence base resulting from the exclusion of different communities and population groups from scientific research.

Because enabling breastfeeding is a key strategy for improving public and population health in the United States, this report identifies opportunities for federal, tribal, state, and local agencies, as well as health care systems, public health departments, health insurers, employers, schools, community-based organizations, and regulators, to enable policies and services that support breastfeeding dyads6 and the communities in which they live, noting where such supports may be particularly effective for historically underserved populations.

The committee was not asked to conduct a novel review of the health effects of breastfeeding. Any new or additional analyses were not feasible within the time and resource constraints of the study. However, the committee reviewed the available literature and referred to pertinent reviews throughout the report. Recent systematic reviews assess this literature (e.g., Feltner et al., 2018; Patnode et al., 2025; Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2023). In addition, the committee was not charged with conducting cost calculations for implementation of new or expanded programs to support breastfeeding. The committee did review the existing cost calculations of suboptimal

___________________

5 The term lactation support provider includes both clinicians and nonclinical members of the current workforce.

6 The term breastfeeding dyad describes the biological and psychosocial relationship between the mother and infant or child.

breastfeeding (i.e., the macroeconomic, health, and social costs of current U.S. breastfeeding rates; see Chapter 2).

The committee also notes that the infant formula crisis of 2022 prompted important discussions about breastfeeding in the United States. In late 2021 and early 2022, a recall of specific infant formula products—followed by a pause in production—resulted in a widespread, national shortage of infant formula. The commercial milk formula industry is discussed throughout this report as an actor in the broader public health and marketing setting that influences the breastfeeding dyad. A previous National Academies report, Challenges in Supply, Market Competition, and Regulation of Infant Formula in the United States (2024), discusses the commercial milk formula industry in depth and recommends actions for reducing the risk and lessening the effect of any future disruption to the commercial milk formula supply chain. Importantly, that report makes clear that scaling up support for breastfeeding is key to protecting infant health during such supply disruptions (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2024).

STUDY METHODS

The committee assembled to conduct this study consisted of 15 expert scholars and practitioners who represented a broad range of disciplines, including lactation and breastfeeding promotion and support, public health, public policy, nursing, nutrition, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, economics, social marketing and public information campaigns related to nutrition, and WIC and other public health programs; committee members included parents and women with breastfeeding lived experience. The committee held four in-person meetings and one virtual committee meeting and conducted additional discussions by videoconference and digital platforms. The first, second, and third committee meetings included public information-gathering sessions, during which the committee heard from invited participants, including the study sponsors and former congressional representatives, as well as individuals and researchers from academia, advocacy organizations, and public policy research institutions. In addition, the committee held six virtual public information-gathering sessions throughout the study. The fourth and fifth committee meetings were closed to the public to allow the committee to further deliberate and finalize its report.

Public Information-Gathering Sessions

The public information-gathering sessions served to augment the committee members’ expertise, solicit opinions from community representatives and key actors, and facilitate exchanges among parties that might

not have the opportunity to disseminate information and ideas otherwise. They were open to the public and live streamed. Invited guests were asked to share their lived experiences and expertise as it related to the foci of the information-gathering session. Public attendees were able to provide questions during and after the sessions, when appropriate.

Serious consideration was given to including practice-based and community-engaged evidence during the information-gathering sessions to ensure that the lived experience of those closest to the study topic would be reflected in the report (Farrell et al., 2021). To this end, six listening sessions were held virtually for further discussion on breastfeeding and (a) the role of community coalitions, (b) the experiences of fathers and partners, (c) individual experiences in hospitals or other birth settings, (d) considerations for families, (e) perspectives from lactation support providers, and (f) return to work postpartum. While the committee attempted to ensure that a wide range of perspectives were shared during the public information-gathering sessions, they were not representative samples. Therefore, while they highlight topics and areas as points requiring further inquiry and deliberation, they do not serve as the basis for the committee’s recommendations. Rather, the public sessions revealed embedded values in the provided testimony and shared literature (see Box 1-3 for a summary of common themes across perspectives). These values helped provide additional depth and nuance to the committee’s deliberations and, where appropriate, are reflected throughout the narrative of the report.

Strength of Evidence

The committee weighed the strength of the evidence throughout the report, as well as the assumptions embedded within various theoretical models. Most of the available evidence on the importance of breastfeeding is observational in design. The limited availability of randomized controlled trials in breastfeeding research is due to the ethical restrictions of randomly assigning a control to not breastfeed or provide human milk, as well as considerations related to informed consent (e.g., providing adequate and accurate information about the benefits of breastfeeding, protecting the right of the parent to breastfeed or of an infant to be breastfed), beneficence, and appropriate outcome measures (Binns et al., 2017). Other ethical issues identified in a review of lactation interventions by Subramani et al. (2023) include the normative assumptions of motherhood and autonomy, disclosure of relevant information, the role of stigma and the social context, and ethical considerations related to health communication campaigns and financial incentives.

The committee acknowledges that observational studies assessing the associations between breastfeeding and morbidity are influenced by

potential sources of biases, including measurement, selection, confounding, and reverse causality. Observational study designs are unable to determine causality, and there are limits to existing study measurements, definitions of the “exposed population,” and incidence ratios. Although carefully designed natural experiments aimed at identifying causal effects have the potential to get around many of these problems, they are not a panacea, as clean treatment and control groups may be difficult to find and some confounders may still be present. Moreover, their generalizability may be limited. As such, the committee assessed various types of available evidence and described key considerations related to study design and results when describing reported outcomes.

BOX 1-3

Common Themes Across Listening Session Perspectives

Gaps in Lactation Support. There is a shortage of accessible breastfeeding support services that meet the full range of family needs. Community coalitions help fill these gaps by offering care that reflects local values and practices.

Role of Community Coalitions. Coalitions use local expertise, train trusted individuals, and offer practical, personalized support. However, many operate with limited and inflexible funding sources, making sustainability a challenge.

Need for Improved Data. Grouping distinct populations into broad categories can result in data that fail to reflect actual experiences. Participants stressed the value of having a standardized yet flexible tool to collect more accurate breastfeeding data.

Lactation Support Provider Workforce. Becoming a lactation support provider often requires navigating high costs and limited training access. Supportive training environments and financial assistance help people enter and stay in the field. Daily work includes consultations, education, and coordination with care teams.

Support in Health Care Settings. Participants described challenges receiving breastfeeding support in medical settings. Improving provider training in lactation care and communication could help families have more consistent and helpful experiences.

Involvement of Fathers and Partners. Fathers and partners play an important role in supporting breastfeeding. Involving them early, offering educational resources, and adjusting care models to include them can improve outcomes for the whole family.

Workplace and Policy Considerations. Gaps in workplace accommodations and paid leave create barriers to continuing breastfeeding after returning to work. Participants recommended clear policies, paid breaks, and flexibility to help parents manage both work and infant care.

The current evidence base continues to grow. Epidemiological models can provide risk ratios for a variety of maternal, infant, and child health and development outcomes associated with infant feeding exposure.

To complement this work, cost models and calculators provide a range of economic estimates to policymakers and the public (see Chapter 2).

Given these research and methodological considerations, multiple research designs and methods may be used to inform considerations for implementation, policy, and practice. To this end, the committee offers a comprehensive presentation of available evidence, including experimental and observational studies using quantitative and/or qualitative data, across a range of outcomes. It presents the evidence with intentional language on evidence generation, application, and outcomes of interest. And recommendations for future research are identified in Chapter 9.

Finally, the committee acknowledges that the scope of federal recommendations and the roles of identified actors may shift significantly in response to federal reorganization efforts, potentially altering agency responsibilities, streamlining decision-making processes, and redistributing authority among existing or newly created entities.

REPORT ORGANIZATION

Following this introduction, Chapter 2 details the importance of breastfeeding, including health benefits for infants and mothers, as well as the physiology of lactation. It then presents a life course perspective to demonstrate how these benefits may be conferred over time and includes a discussion of the costs of current suboptimal breastfeeding rates. Chapter 3 describes breastfeeding in the community context and explores the social ecology of breastfeeding, the history of breastfeeding in the United States, cultural perceptions, interpersonal influences, and promising approaches for communities.

The following chapters of the report use the leverage points and opportunities for action identified in the social ecological framework to review the institutions, organizations, and settings that influence breastfeeding. Chapter 4 describes federal and state public health policies, programs, and investments that support and promote breastfeeding. It also provides an overview of the current public health surveillance system, the role of the WIC program in breastfeeding support, and public health approaches that support breastfeeding in emergencies and disasters. Chapter 5 identifies the media, marketing, and messaging environment for breastfeeding, human milk supplies, and commercial milk formula. Chapter 6 articulates the role that health care systems and settings play in breastfeeding and lactation support and describes the current lactation provider workforce in the medical setting. Chapter 7 delves into the financing, payment, and insurance coverage of lactation services and supplies. Chapter 8 explores family leave, as well as the role of employers, school systems, and childcare providers in supporting breastfeeding during the return to work or school

postpartum. Finally, Chapter 9 describes future research needs and implementation considerations.

A guiding assumption driving the committee’s recommendations is that families and communities will make the best possible decisions for themselves given present constraints and available resources. Therefore, it is important to implement structures, policies, and practices to support and enable families to initiate and sustain breastfeeding; these need to be accompanied by clear evidence-based guidance for families and communities about the options and supports available. Taken together, the recommendations presented in Chapters 3–8 provide a comprehensive set of strategies for supporting all families in their breastfeeding journeys. These strategies aim to foster the conditions and systems needed to achieve national goals to increase breastfeeding rates. These opportunities for investment can improve health and well-being across future generations and prevent excess costs related to suboptimal breastfeeding rates.

This report’s recommendations present proven overall strategies across multiple settings for supporting all families on their lactation journeys. They outline approaches that will foster the conditions and systems needed to achieve national goals to increase overall breastfeeding rates and address variances in these rates and health outcomes across populations.

REFERENCES

American College of Nurse-Midwives. (2022). Position statement: Breastfeeding/chestfeeding. https://midwife.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Breastfeeding-Chestfeeding.pdf

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). (2021). Barriers to breastfeeding: Supporting initiation and continuation of breastfeeding: ACOG committee opinion summary, Number 821. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 137(2), 396–397. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000004250

———. (2023). Duration of breastfeeding update. Practice Advisory. ACOG Clinical. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory/articles/2023/02/duration-of-breastfeeding-update

American Public Health Association. (1981, December 31). Breastfeeding [Policy brief]. https://www.apha.org/policy-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-briefs/policy-database/2014/07/10/08/37/breastfeeding

———. (2000, December 3). APHA supports the Health and Human Services blueprint for action on breastfeeding [Policy brief]. https://www.apha.org/policy-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-briefs/policy-database/2014/07/15/13/12/apha-supports-the-health-and-human-services-blueprint-for-action-on-breastfeeding

———. (2007, November 6). A call to action on breastfeeding: A fundamental public health issue [Policy Statement 2007-14]. https://www.apha.org/policy-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-briefs/policy-database/2014/07/29/13/23/a-call-to-action-on-breastfeeding-a-fundamental-public-health-issue

———. (2011, November 1). APHA endorses the Surgeon General’s Call to Action to support breastfeeding. https://www.apha.org/policy-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-briefs/policy-database/2014/07/07/10/42/apha-endorses-the-surgeon-generals-call-to-action-to-support-breastfeeding

———. (2013, November 5). An update to a call to action to support breastfeeding: A fundamental public health issue. https://www.apha.org/policy-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-briefs/policy-database/2014/07/09/15/26/an-update-to-a-call-to-action-to-support-breastfeeding-a-fundamental-public-health-issue

Anstey, E. H., Chen, J., Elam-Evans, L. D., & Perrine, C. G. (2017). Racial and geographic differences in breastfeeding—United States, 2011–2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66(27), 723–727. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6627a3

Asiodu, I. V., Bugg, K., & Palmquist, A. E. L. (2021). Achieving breastfeeding equity and justice in Black communities: Past, present, and future. Breastfeeding Medicine, 16(6), 447–451. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2020.0314

Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses. (2021). Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 50(5), e1–e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogn.2021.06.006

Bartick, M. C., Schwarz, E. B., Green, B. D., Jegier, B. J., Reinhold, A. G., Colaizy, T. T., Bogen, D. L., Schaefer, A. J., & Stuebe, A. M. (2017). Suboptimal breastfeeding in the United States: Maternal and pediatric health outcomes and costs. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13(1), e12366. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12366

Binns, C., Lee, M. K., & Kagawa, M. (2017). Ethical challenges in infant feeding research. Nutrients, 9(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9010059

Borger, C., Weinfield, N. S., Paolicelli, C., Sun, B., & May, L. (2021). Prenatal and postnatal experiences predict breastfeeding patterns in the WIC infant and toddler feeding practices study-2. Breastfeeding Medicine, 16(11), 869–877. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2021.0054

Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2022a). Recommendations and benefits. https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/infantandtoddlernutrition/breastfeeding/recommendations-benefits.html

———. (2022b). Breastfeeding report card. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding-data/breastfeeding-report-card/index.html

———. (2024a). QuickStats: Percentage of newborns breastfed between birth and discharge from hospital, by maternal age—National vital statistics system, 49 states and the District of Columbia, 2021 and 2022. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 73. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7304a6

———. (2024b). Definitions. https://www.cdc.gov/infant-toddler-nutrition/resources/definitions.html#cdc_generic_section_3-complementary-foods

Chiang, K. V., Li, R., Anstey, E. H., & Perrine, C. G. (2021). Racial and ethnic disparities in breastfeeding initiation—United States, 2019. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 70(21), 769–774. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7021a1

Dewey, K., Bazzano, L., Davis, T., Donovan, S., Taveras, E., Kleinman, R., Güngör, D., Madan, E., Venkatramanan, S., Terry, N., Butera, G., & Obbagy, J. (2020). The duration, frequency, and volume of exclusive human milk and/or infant formula consumption and overweight and obesity: A systematic review. USDA Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review. https://doi.org/10.52570/NESR.DGAC2020.SR0301

Díaz, L. E., Yee, L. M., & Feinglass, J. (2023). Rates of breastfeeding initiation and duration in the United States: Data insights from the 2016–2019 Pregnancy Risk-Assessment Monitoring System. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1256432. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1256432

Farrell, L., Langness, M., & Falkenburger, E. (2021, February 19). Community voice is expertise. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/community-voice-expertise

Feltner, C., Weber, R. P., Stuebe, A., Grodensky, C. A., Orr, C., & Viswanathan, M. (2018). Breastfeeding programs and policies, breastfeeding uptake, and maternal health outcomes in developed countries. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. https://doi.org/10.23970/AHRQEPCCER210

Griswold, M. K., Crawford, S. L., Perry, D. J., Person, S. D., Rosenberg, L., Cozier, Y. C., & Palmer, J. R. (2018). Experiences of racism and breastfeeding initiation and duration among first-time mothers of the Black Women’s Health Study. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 5(6), 1180–1191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-018-0465-2

Gunja, M. Z., Gumas, E. D., Masitha, R., & Zephyrin, L. C. (2024). Insights in the U.S. maternal mortality crisis: An international comparison [Issue brief]. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2024/jun/insights-us-maternal-mortality-crisis-international-comparison

Gyamfi, A., O’Neill, B., Henderson, W. A., & Lucas, R. (2021). Black/African American breastfeeding experience: Cultural, sociological, and health dimensions through an equity lens. Breastfeeding Medicine, 16(2), 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2020.0312

Human Milk Banking Association of North America. (2024). Milk banking frequent questions. https://www.hmbana.org/about-us/frequent-questions.html

Jegier, B. J., Smith, J. P., & Bartick, M. C. (2024). The economic cost consequences of suboptimal infant and young child feeding practices: A scoping review. Health Policy and Planning, 39(9), 916–945. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czae069

Kirksey, K. (2021). A social history of racial disparities in breastfeeding in the United States. Social Science & Medicine, 289, 114365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114365

Labiner-Wolfe, J., Fein, S. B., Shealy, K. R., & Wang, C. (2008). Prevalence of breast milk expression and associated factors. Pediatrics, 122(Suppl 2), S63–S68. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-1315h

Li, R., Ware, J., Chen, A., Nelson, J. M., Kmet, J. M., Parks, S. E., Morrow, A. L., Chen, J., & Perrine, C. G. (2022). Breastfeeding and post-perinatal infant deaths in the United States, A national prospective cohort analysis. The Lancet Regional Health—Americas, 5, 100094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2021.100094

Lind, J. N., Perrine, C. G., Li, R., Scanlon, K. S., & Grummer-Strawn, L. M. (2014). Racial disparities in access to maternity care practices that support breastfeeding—United States, 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 63(33), 725–728.

Lott, M., Callahan, E., Welker Duffy, M., & Daniels, S. (2019). Consensus statement. Healthy beverage consumption in early childhood: Recommendations from key national health and nutrition organizations. Healthy Eating Research. https://healthyeatingresearch.org/research/consensus-statement-healthy-beverage-consumption-in-early-childhood-recommendations-from-key-national-health-and-nutrition-organizations/

Louis-Jacques, A., Deubel, T. F., Taylor, M., & Stuebe, A. M. (2017). Racial and ethnic disparities in U.S. breastfeeding and implications for maternal and child health outcomes. Seminars in Perinatology, 41(5), 299–307. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2017.04.007

Lucas, A., & Cole, T. J. (1990). Breast milk and neonatal necrotising enterocolitis. The Lancet, 336(8730), 1519–1523. https://doi.org/10.1016/0140-6736(90)93304-8

Lutter, C. K., Hernández-Cordero, S., Grummer-Strawn, L., Lara-Mejía, V., & Lozada-Tequeanes, A. L. (2022). Violations of the International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes: A multi-country analysis. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 2336. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14503-z

Martin, J. A., Hamilton, B. E., & Osterman, M. J. K. (2024). Births in the United States, 2023. National Center for Health Statistics Data Briefs. https://doi.org/10.15620/cdc/158789

Meek, J. Y., Noble, L., & Section on Breastfeeding. (2022). Policy statement: Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics, 150(1), e2022057988. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2022-057988

Miller, J., Tonkin, E., Damarell, R. A., McPhee, A. J., Suganuma, M., Suganuma, H., Middleton, P. F., Makrides, M., & Collins, C. T. (2018). A systematic review and meta-analysis of human milk feeding and morbidity in very low birth weight infants. Nutrients, 10(6), 707. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10060707

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2024). Challenges in supply, market competition, and regulation of infant formula in the United States. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/27765

Noiman, A., Kim, C., Chen, J., Elam-Evans, L. D., Hamner, H. C., & Li, R. (2024). Gains needed to achieve healthy people 2030 breastfeeding targets. Pediatrics, 154(3), e2024066219. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2024-066219

Nommsen-Rivers, L. A., & Dewey, K. G. (2009). Development and validation of the infant feeding intentions scale. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 13(3), 334–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-008-0356-y

Odom, E. C., Li, R., Scanlon, K. S., Perrine, C. G., & Grummer-Strawn, L. (2013). Reasons for earlier than desired cessation of breastfeeding. Pediatrics, 131(3), e726–732. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-1295

Palmquist, A. E. L., Perrin, M. T., Cassar-Uhl, D., Gribble, K. D., Bond, A. B., & Cassidy, T. (2019). Current trends in research on human milk exchange for infant feeding. Journal of Human Lactation, 35(3), 453–477. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334419850820

Patnode, C. D., Senger, C. A., Coppola, E. L., & Iacocca, M. O. (2025). Interventions to support breastfeeding: Updated evidence report and systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (Evidence Synthesis No. 242). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK615503/

Pérez-Escamilla, R., Tomori, C., Hernández-Cordero, S., Baker, P., Barros, A. J. D., Bégin, F., Chapman, D. J., Grummer-Strawn, L. M., McCoy, D., Menon, P., Ribeiro Neves, P. A., Piwoz, E., Rollins, N., Victora, C. G., & Richter, L. (2023). Breastfeeding: Crucially important, but increasingly challenged in a market-driven world. The Lancet, 401(10375), 472–485. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01932-8

Quigley, M., Embleton, N. D., Meader, N., & McGuire, W. (2024). Donor human milk for preventing necrotising enterocolitis in very preterm or very low-birthweight infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2024(9), CD002971. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002971.pub6

Raju, T. N. K. (2023). Achieving healthy people 2030 breastfeeding targets in the United States: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of perinatology: Official Journal of the California Perinatal Association, 43(1), 74–80. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-022-01535-x

Rasmussen, K. M., Felice, J. P., O’Sullivan, E. J., Garner, C. D., & Geraghty, S. R. (2017). The meaning of “breastfeeding” is changing and so must our language about it. Breastfeeding Medicine, 12(9), 510–514. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2017.0073

Robinson, K., Fial, A., & Hanson, L. (2019). Racism, bias, and discrimination as modifiable barriers to breastfeeding for African American women: A scoping review of the literature. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 64(6), 734–742. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmwh.13058

Sami, A. S., Frazer, L. C., Miller, C. M., Singh, D. K., Clodfelter, L. G., Orgel, K. A., & Good, M. (2023). The role of human milk nutrients in preventing necrotizing enterocolitis. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 11, 1188050. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2023.1188050

Segura-Pérez, S., Hromi-Fiedler, A., Adnew, M., Nyhan, K., & Pérez-Escamilla, R. (2021). Impact of breastfeeding interventions among United States minority women on breastfeeding outcomes: A systematic review. International Journal for Equity in Health, 20(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-021-01388-4

Subramani, S., Vinay, R., März, J. W., Hefti, M., & Biller-Andorno, N. (2023). Ethical issues in breastfeeding and lactation interventions: A scoping review. Journal of Human Lactation, 40(1), 150–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/08903344231215073

U.S. Department of Agriculture, & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025 (9th ed.). DietaryGuidelines.gov

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). (n.d.). Increase proportion infants who are breastfed 1 year (MICH-16). https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/infants/increase-proportion-infants-who-are-breastfed-1-year-mich-16

———. (1984). Surgeon general’s workshop on breastfeeding and human lactation. https://rmp.nlm.nih.gov/spotlight/nn/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-101584932X528-doc

———. (2000). HHS blueprint for action on breastfeeding. Office of the Surgeon General.

———. (2011). The Surgeon General’s call to action to support breastfeeding. Office of the Surgeon General.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (2018). Types of breast pumps. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/breast-pumps/types-breast-pumps

———. (2023). Labeling of infant formula: Guidance for industry. https://www.fda.gov/media/99701/download

Ware, J. L., Li, R., Chen, A., Nelson, J. M., Kmet, J. M., Parks, S. E., Morrow, A. L., Chen, J., & Perrine, C. G. (2023). Associations between breastfeeding and post-perinatal infant deaths in the U.S. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 65(5), 763–774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2023.05.015

World Health Organization. (2023). Infant and young child feeding. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infant-and-young-child-feeding