Breastfeeding in the United States: Strategies to Support Families and Achieve National Goals (2025)

Chapter: 3 Breastfeeding in the Community Context

3

Breastfeeding in the Community Context

Infant feeding trajectories are complex and shaped by a range of structural, social, and cultural factors. From maternity care practices and workplace protections to social norms and historical narratives and shifts, a layered ecosystem of influences shapes how, when, and whether breastfeeding occurs. As such, the current landscape of breastfeeding in the United States reflects both progress and persistent challenges shaped by a variety of influences.

This chapter first situates breastfeeding within a broader social ecological framework to illuminate the many systems and forces that affect infant feeding decisions and practices. Next, it turns to a brief history of breastfeeding in the United States, tracing how shifting cultural perceptions and institutional policies have impacted breastfeeding outcomes over time. Then, the committee explores how interpersonal relationships within communities of support, especially those provided by fathers or partners, family members, peers, and lactation support providers, play a critical role in shaping breastfeeding experiences and outcomes.

Understanding these influences is key to designing policy and programmatic interventions that address the cultural, structural, and relational factors that shape breastfeeding. This chapter lays the groundwork for identifying levers of change and building systems that center the needs and realities of families. Subsequent chapters will take a setting-by-setting approach to highlight best practices, evidence-based interventions, and future research needs to improve current suboptimal breastfeeding rates.

THE SOCIAL ECOLOGY OF BREASTFEEDING

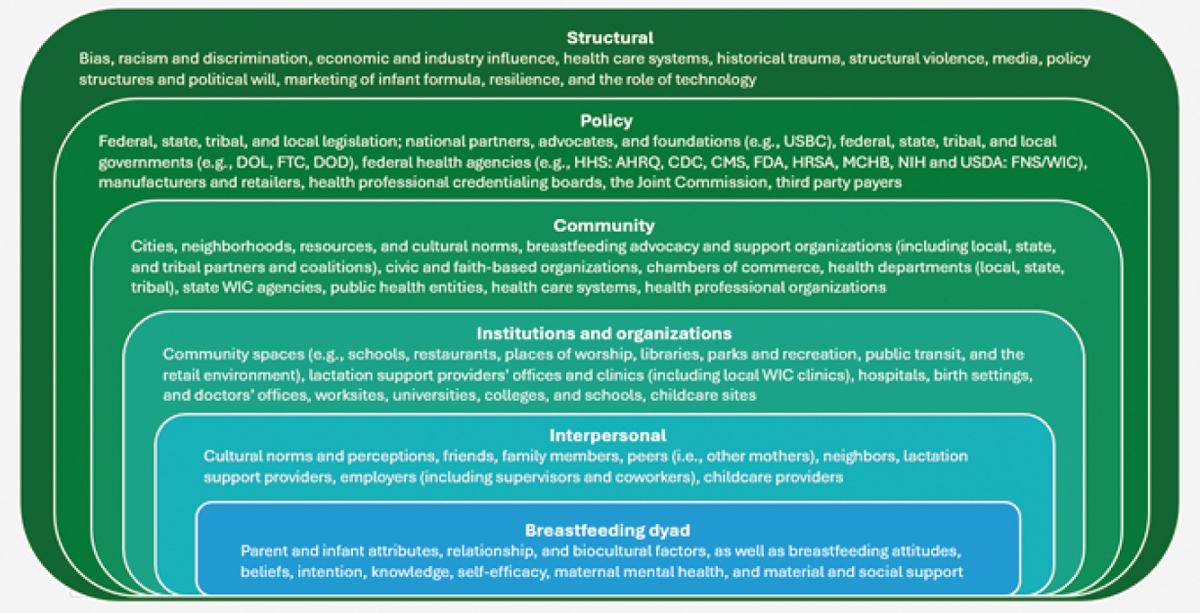

The committee took a social ecological approach in developing this report, recognizing intersecting influences across levels to identify levers for change and opportunities for action (Figure 3-1). This approach centers the breastfeeding dyad in the current landscape of intersecting structural and political influences on breastfeeding and identifies key actors who can work together to enable more families to sustain breastfeeding and reduce or eliminate variances in breastfeeding indicators and rates. Within the context of the life course (see Chapter 2), the social ecological framework illustrates the complex sociocultural environment that influences breastfeeding and the opportunities for interventions that protect, promote, and support breastfeeding mothers and families and thus address overall rates of breastfeeding and differences in breastfeeding outcomes among populations. The committee’s goal in using this framework was to highlight the complex intersection of broad social and structural factors in shaping breastfeeding outcomes.

Structural

Structural influences operate at the outer level of the model and influence all parts of the lactation journey (Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2023). Structural influences and resulting variances are deeply embedded in policies, laws, governance, and media and culture; they organize the distribution of power and resources differentially across individual and group characteristics (race, ethnicity, sex, gender identity, class, sexual orientation, gender expression, and others). These influences range from broader structural conditions, including socioeconomic variances and exposure to protective and risk factors, that shape foundational aspects of life, from housing to access to food, employment, childcare, and other resources, as well as daily experiences. These conditions may also contribute to, or exacerbate, maternal mental health and the overall well-being of families and communities (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [National Academies], 2024). For instance, a mother may face challenges responding to infant feeding cues when she is attempting to address housing challenges or facing food insecurity for her family (Dinour et al., 2020; Gross et al., 2012, 2019; Orozco et al., 2020; Reno et al., 2022). These conditions influence the trajectory of pregnancy and birth outcomes. Additionally, Krieger et al. (2020), Braveman et al. (2021), and Crear-Perry et al. (2021) identified structural racism as a key underlying driver of preterm births and other poor birth outcomes.

Policy

The next level of the model represents the policies that influence the subsequent levels of the model in descending order. The overarching policy

NOTES: In the case of multiples, the dyad might be referred to as a “triad” or other terminology may be used. AHRQ = Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; CDC = U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CMS = Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; DOD = U.S. Department of Defense; DOL = U.S. Department of Labor; FDA = Food and Drug Administration; FTC = Federal Trade Commission; FNS = Food and Nutrition Service; HHS = U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; HRSA = Health Resources and Services Administration; MCHB = Maternal and Child Health Bureau; NIH = National Institutes of Health; USBC = U.S. Breastfeeding Committee; USDA = U.S. Department of Agriculture; WIC = Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

SOURCE: Committee generated, adapted from National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (National Academies), 2017b.

environment includes the role of advocacy groups and coalitions; the impact of legislation at federal, state, tribal, and local levels; and the influence of financing, monitoring, and regulation. These policies, their impacts, and levers for change are discussed throughout the report in the context of various settings, institutions, and organizations.

Communities, Institutions, and Organizations

Figure 3-1 showcases the model in such a way that displays the inter-level relationships that exist, such as within the community level, where relationships between both the institution and organization level can be found. Beyond the different inter-level relationships, the figure showcases different factors that can contribute to the breastfeeding dyad’s health and well-being. A community is a place where individuals and families can live, work, thrive, and engage in play (National Academies, 2017a). As such, communities are shaped by larger structural and political forces and can bidirectionally build power and capacity to create change (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2025). In this report, institutions and organizations include agencies, businesses, childcare settings, community spaces, health care systems, public health systems and settings (e.g., WIC clinics), universities, colleges, schools, tribal networks, and the workplace. These settings are complex and interdependent, as detailed in Chapters 4–8.

Although additional drivers may influence the breastfeeding dyad, the identified systems, settings, and policies in this model are those most relevant to the committee’s charge. For instance, the dynamics of the dyad are shaped not only by experiences with the public health and health care system throughout pregnancy, birth, and during the postpartum period, but also by education, employment, and labor conditions (Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2023). Women may experience necessary and unnecessary mother–infant separation (e.g., health care facility does not practice “rooming in”), delayed breastfeeding initiation, early supplementation with commercial milk formula, or lack of lactation support providers. They may also experience mistreatment and discrimination at prenatal care and birth facilities, which disrupts the coordination between the dyad and therefore makes breastfeeding more difficult (Liu et al., 2024; Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2023; Vedam et al., 2019). Alternatively, they may receive support from peer counselors or early and frequent prenatal education, which may improve their breastfeeding experience and duration. Work conditions may also influence the experience of the postpartum period (Tomori et al., 2022a; Vilar-Compte et al., 2021). Extended periods of separation soon after birth and unsupportive workplace policies further disrupt the coordination between the dyad that is needed to establish and maintain lactation (Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2023).

Interpersonal and Individual-Level Influences

The next two levels represent factors that most directly and proximally shape the dyad’s daily experiences and routine patterns: interpersonal relationships (e.g., peer support, family influences) and individual-level influences (e.g., attitudes, beliefs, and norms about breastfeeding). Breastfeeding initiation, exclusivity, and duration are heavily influenced by access to social support, culturally informed resources, community advocacy, and attitudes and beliefs (Asiodu et al., 2021; Houghtaling et al., 2018; Monteith et al., 2024; Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2023; Tomori et al., 2022a). The model emphasizes that these interrelated factors and influences can determine the ability of the breastfeeding dyad to achieve the mother’s breastfeeding goals.

Social Media Influences

Social media use intersects across the community and interpersonal levels. While direct interactions and communication between individuals and peers are facilitated at the interpersonal level, social media platforms also enable the creation and continuation of larger breastfeeding support groups and infant feeding communities (Morse & Brown, 2022). Concerns and challenges regarding misinformation, unrealistic expectations, and judgment experienced across social media platforms have been raised (Morse & Brown, 2022; Regan & Brown, 2019). However, social media support has been shown to positively influence breastfeeding attitudes, self-efficacy, and perceived social support (Sanchez et al., 2023; Wolynn, 2012). This support is especially critical for mothers and families with limited access to lactation support providers, culturally responsive social support, or previous experience with breastfeeding (Asiodu et al., 2015; Haley et al., 2023). The role and impact of traditional and digital media is further discussed in Chapter 5.

HISTORY OF BREASTFEEDING IN THE UNITED STATES

Breastfeeding practices in the United States have undergone significant shifts over time. This section explores the history of breastfeeding in the United States, highlighting the interplay of sociohistorical dynamics, changing sociocultural norms, medical practices, and policy interventions that have influenced breastfeeding practices over time. This historical perspective sheds light on how social and policy choices influence breastfeeding rates in the United States.

As described in Chapter 2, breastfeeding is a biocultural process—connecting biological processes and sociocultural practices simultaneously. Lactation’s physiological roots reflect evolutionary strategies critical to

human survival. The intensive care that human infants require to survive indicates that cultural adaptations maintaining close contact and frequent feeding have been important for support of breastfeeding around the world. Breastfeeding practices are also shaped by societal values, norms, and structures (Quinn et al., 2023; Tomori et al., 2022b).

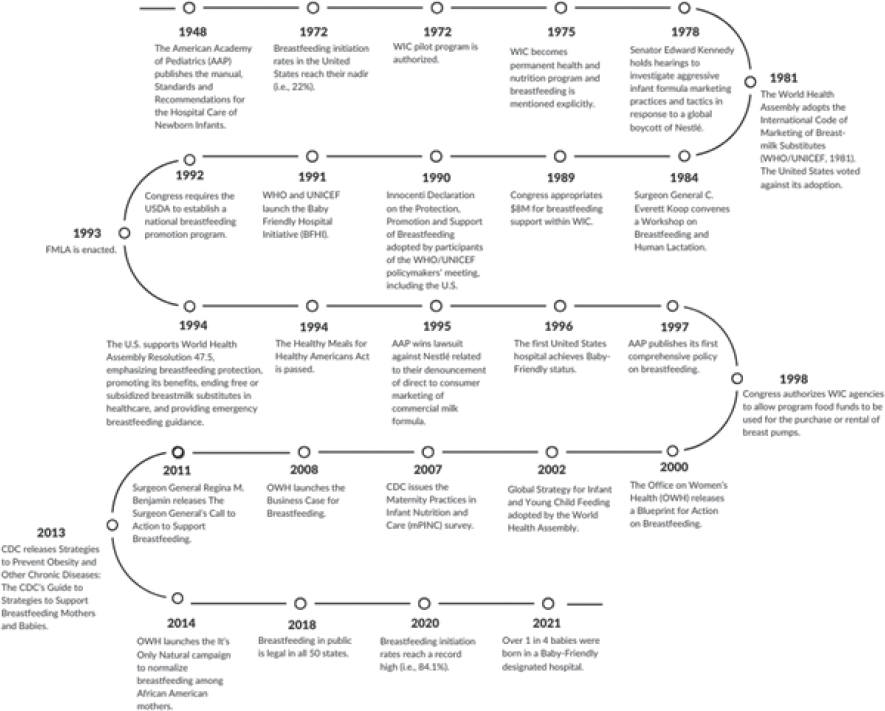

Across centuries, breastfeeding practices and trends in the United States have changed, influenced by social, cultural, and economic shifts; the growing influence of medicine; and policy interventions (Figure 3-2). These influences led to extremely low rates of breastfeeding by the middle of the 20th century, but additional social, cultural, and economic shifts drove a rebounding of breastfeeding rates in later decades, though variances persist across sociodemographic groups.

19th- to Mid-20th Centuries

Historically, the people and cultures of the United States have had strong traditions of breastfeeding (Theobald, 2019). However, these traditions were disrupted by large-scale historical and social changes that date back to the founding of the nation, with different impacts for various communities. For example, Native American communities experienced forced displacement, dispossession, forced removal of children, and systematic undermining of breastfeeding and other traditional childbearing practices (Theobald, 2019).

Historical scholars have also documented how enslaved Africans were brought to the United States forcibly via the transatlantic slave trade and subjected to violence and forced reproduction under enslavement (Morgan, 2004; Roberts, 1997). Moreover, enslaved women were often required to serve as wet nurses for enslavers’ children and forced to prioritize feeding the enslavers’ infants over their own (Bugg et al., 2024; Schwartz, 2006; West & Knight, 2017). Even after slavery ended, exploitive wet nursing practices persisted, continuing well into the 20th century (West & Knight, 2017; Wolf, 1999). West and Knight (2017) reported that this practice contributed to higher infant mortality rates and disrupted breastfeeding traditions in African American communities descended from enslaved Africans in the United States. In a history of midwifery in the South, Fraser (1998) documented how breastfeeding in Black communities was undermined by systematic efforts that destabilized midwifery in these communities in the early 20th century, leading to a loss of cultural knowledge with far-reaching impacts for health and well-being. Collectively, these studies show the influence of system-level factors, including violence and exploitation, that have left a profound mark on these communities and reverberate in contemporary maternal–infant health variances seen today (Asiodu et al., 2021; DeVane-Johnson et al., 2018; Green et al., 2021; Monteith et al., 2024; Tomori et al., 2022b; Warne & Wescott, 2019).

NOTE: CDC = U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; FMLA = Family and Medical Leave Act; USDA = U.S. Department of Agriculture; WHO = World Health Organization; WIC = Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Leavitt’s (2016) history of childbearing in the United States documents that the medicalization of birth, initially led by wealthy, White women in the late 19th century, had unequal impacts on breastfeeding (Leavitt, 2016). A growing number of interventions, particularly the introduction of anesthesia, led to the movement of births into the hospital. With the consolidation of physician professionalization, midwifery was undermined, particularly in racial/ethnic minority communities (Fraser, 1998). Fraser (1998) recounted how midwifery was depicted as unsafe and midwives as backwards and ignorant, and births were moved under the supervision of White physicians and nurses. By the mid-20th century most births took place at the hospital (Leavitt, 2016). This disrupted birth and breastfeeding traditions, and hospital practices in birth and postpartum undermined breastfeeding (Apple, 1987; Millard, 1990). In particular, heavy sedation, mother–infant separation, and scheduled feedings with formula led to only about a quarter of infants being put to breast by 1970 (Apple, 1987; Millard, 1990; Wolf, 2006).

Apple’s (1987) history of infant feeding in the United States describes how the introduction of commercial milk formula in the late 19th century and its industrial production further accelerated this shift. Initially marketed to wealthier families, formula was advertised as a “scientific” alternative to breastfeeding, appealing to mothers seeking convenience or social status (Apple, 1987). Formula promotion was heavily intertwined with the professionalization of pediatrics, with pediatricians often pioneering their own formulas prior to the manufacturing of formulas on a large scale (Apple, 1987). Physicians often undermined breastfeeding in practice with advice that contradicted the physiology of breastfeeding, including limiting the frequency of feedings, early introduction of formula and other foods, and limiting skin-to-skin contact (Tomori, 2025). Of note, the earliest infant feeding recommendation issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics was in 1948: Standards and Recommendations for the Hospital Care of Newborn Infants. This manual included a recommendation to make every effort to have every mother nurse her full-term infant; however, few mothers at the time were provided with the support to do so.

Wolf (2001), in a history of breastfeeding and the public health system, described how other societal changes in the 19th century also began to change traditional breastfeeding practices. Industrialization, urbanization, and large-scale migration restructured family life, pulling families into urban settings and leading many women to work in settings, such as factories, that did not accommodate young children (Wolf, 2001). This often led to decreases in the duration of breastfeeding and earlier introduction of other foods, contributing to high rates of infectious disease and infant mortality (Wolf, 2001). Early public health attempts to address these problems often focused on “clean milk campaigns” that distributed clean

(i.e., unadulterated and pasteurized) cow’s milk while failing to adequately promote, protect, and support breastfeeding; often, they inadvertently further undermined breastfeeding (Wolf, 2001).

As industrial production of commercial infant formula scaled up, physicians and nurses promoted its products both at the hospital and in other settings (Apple, 1987; Wolf, 2006). The infant formula industry undermined breastfeeding by increasingly promoting solid foods to infants as early as a few weeks old (Bentley, 2014).

The combination of these influences led to the dramatic decline of breastfeeding rates in the United States by the mid-20th century, especially among middle- and upper-class families. By this time, most births took place at the hospital (Apple, 1987, Leavitt, 2016). Within the hospital, breastfeeding initiation was greatly diminished through the practices of separating mothers from their newborns immediately after birth, routinely feeding infants commercial milk formula, administering medication to dry up a mothers’ milk supply, and feeding infants on a schedule (Apple, 1987; Millard, 1990). Among the increasingly fewer mothers who initiated breastfeeding, new cultural narratives further undermined breastfeeding duration. These narratives, driven by the rising importance of science and technology, associated formula with modernity and portrayed breastfeeding as outdated and unnecessary (Apple, 1987).

1970s–1980s

Breastfeeding started to receive more public, biomedical, and public health support in the latter part of the 20th century, bolstered by a number of social movements and the growing body of global scientific literature (Weiner, 1994; Wolf, 2001, 2006). White middle-class women led some of these movements, particularly the rise of the La Leche League, which arose from the Catholic Family Movement in 1956 (Ward, 2000; Weiner, 1994). The same social group of women who led the movement away from breastfeeding were now leading its return (Ward, 2000; Weiner, 1994).

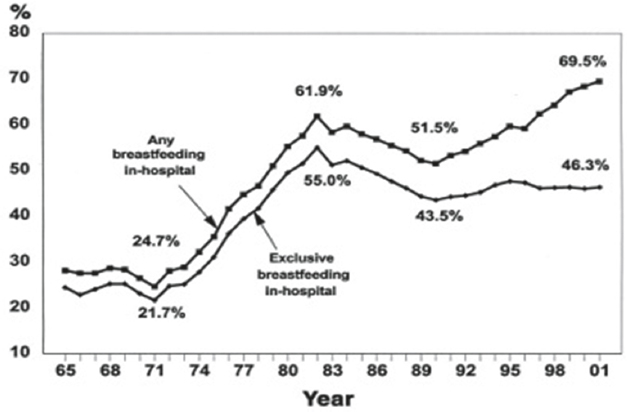

Significant gains were made, particularly in breastfeeding initiation, from the 1970s onward (see Figure 3-3), but these gains have not been distributed equally. Racial/ethnic variances have remained a prominent feature of breastfeeding in the United States. Unequal conditions in the labor market played a significant role in these variances, with Black mothers disproportionately working in jobs with lower wages, fewer opportunities for paid leave, and limited protections for breastfeeding (Whitley et al., 2021).

In 1972, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) was authorized as a two-year pilot program under the Child Nutrition Act of 1966. Its goal was to improve the health of pregnant mothers, infants, and children by providing nutritious foods to

low-income families. The program demonstrated its effectiveness, and in 1975, it became a permanent legislative program (National WIC Association, n.d.). While nutritional support for breastfeeding women was part of WIC from the program’s inception, breastfeeding support and nutrition education were not part of this initial legislation. The history of the WIC program and the importance of the additions of breastfeeding support and nutrition education in the current program are explored in Chapter 5.

In 1974, a global boycott of Nestlé began in response to the company’s marketing practices promoting commercial milk formula in developing nations, which included marketing tactics such as using health care personnel and salespeople dressed as nurses to promote formula; distributing free formula samples to mothers in hospitals, clinics, and homes; and suggesting that formula was superior or equivalent to breastfeeding (Post, 1985; Sasson, 2016). Consequently, infants faced significant health risks from the dilution of infant formula to mitigate costs, as well as lack of safe water and the lack of immunological protection provided by breastfeeding (Boyd, 2012; Post, 1985; Sasson, 2016). A number of scholars have documented how substantial increases in malnutrition, illness, and infant mortality resulted from these marketing strategies (Anttila-Hughes et al., 2018; Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2023; Sasson, 2016).

These concerns culminated in the 1978 Kennedy hearings, led by Senator Edward Kennedy, which investigated the marketing practices of Nestlé and other formula manufacturers (Post, 1985). The hearings laid the groundwork for The International Code of Marketing of Breast-Milk Substitutes (the Code) in 1981. The Code aimed to regulate the promotion of commercial milk formula and related products to protect breastfeeding practices and ensure that caregivers could make informed feeding decisions for their infants and young children. It included provisions to prohibit direct marketing to mothers, restrict free formula samples, and ban promotional activities within health care settings (World Health Organization [WHO], 1981). In addition, it required accurate formula labeling to inform consumers about the benefits of breastfeeding and the potential risks of formula use (WHO, 1981; see Chapters 4 and 6).

The Code received widespread international support, which led to its adoption by the World Health Assembly and many subsequent resolutions. The United States was the only country to vote against its adoption in 1981. Boyd (2012) documented how the U.S. vote was driven by concerns for the potential impact on free trade and by the interests of the commercial milk formula industry (Boyd, 2012).

In the 1980s, the gap between in-hospital exclusive breastfeeding and any breastfeeding rates began to widen significantly in the United States (see Figure 3-3). This shift coincided with the increased marketing of commercial infant formula within hospitals, as documented by the Ross Mother’s Survey, initiated in 1965 (Institute of Medicine [IOM], 1991).

SOURCE: IOM, 1991.

U.S. public health campaigns and advocacy efforts began to shift cultural perceptions of breastfeeding, despite limited action on marketing regulations. By 1989, Congress allocated $8 million for breastfeeding support through WIC (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016). In addition, Surgeon General C. Everett Koop convened the Workshop on Breastfeeding and Human Lactation in 1984 to identify strategies for reducing barriers to breastfeeding in populations with low prevalence and to highlight the state of scientific research, training, and service delivery (Koop & Brannon, 1984). The workshop report later became a national statement published by the Office of the Surgeon General; it reviewed previous federal activities to support breastfeeding and recommended actions to move the field forward (Koop & Brannon, 1984).

1990s–2000s

The 1990s and early 2000s marked a significant period of policy-driven change in breastfeeding support in the United States. The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI), launched by the WHO and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) in 1991, encouraged hospitals to adopt evidence-based practices that promoted breastfeeding, based on the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding (see Chapter 6). These practices included immediate skin-to-skin contact after birth and rooming-in, where mothers and babies stay together

in the same room to facilitate breastfeeding, as well as the provision of breastfeeding education and support and the elimination of commercial milk formula promotion at birth facilities (United Nations Children’s Fund, n.d.).

In 1992, Congress required the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA, 2024) to establish a national breastfeeding promotion program and provided various funding mechanisms. The following year, the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 was enacted, offering eligible employees up to 12 weeks of unpaid, job-protected leave for specified family and medical reasons, including the birth and care of a newborn child (U.S. Department of Labor, 1993). This allowed parents who met these requirements and who had the financial resources up to three months of time to establish breastfeeding practices without the immediate pressure of returning to work. However, these benefits were not available to workers who were not employed in eligible settings and were inaccessible for many without adequate financial resources.

Two years later, the Healthy Meals for Healthy Americans Act of 1994 mandated that state WIC agencies allocate $21 per pregnant and breastfeeding participant for breastfeeding promotion and required the collection and biennial reporting of breastfeeding incidence and duration data among WIC participants (Tomori et al., 2022a). In 1998, Congress authorized WIC agencies to use food funds for the purchase or rental of breast pumps, enhancing access to breastfeeding support tools for low-income families (Public Law 105-336, 1998). That year, California passed Assembly Concurrent Resolution No. 155, encouraging employers to accommodate breastfeeding employees by providing adequate facilities for breastfeeding or expressing milk (Assembly Concurrent Resolution No. 155, 1998).

By 1996, the first U.S. hospital achieved the Baby-Friendly® designation, reflecting progress in both institutional and policy-level support for breastfeeding (Baby-Friendly USA, 2019). However, despite widespread global adoption of the BFHI, the United States was slow to adopt it (Grummer-Strawn et al., 2013, see Chapter 6). In addition, in 2007, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) began to monitor Baby-Friendly practices by developing and implementing the Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care national survey, and the country began to see a rise in Baby-Friendly hospitals over the decade (Feldman-Winter et al., 2017; Grummer-Strawn et al., 2013).

While these initiatives marked significant progress in addressing barriers to breastfeeding, in 2000, the publication of Surgeon General’s Blueprint for Action on Breastfeeding drew critical attention to variances in breastfeeding rates in the United States and the importance of breastfeeding for maternal and child health (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2000). HHS (2000) highlighted differences in breastfeeding rates by race and ethnicity, noting that while 75% of all U.S. mothers initiated

breastfeeding, only 58% of non-Hispanic Black mothers, 68% of WIC participants, and 67% of mothers with less than high school education initiated breastfeeding (see also HHS, 2011). HHS (2000) argued that this gap underscored the need for targeted interventions, including revisions to WIC food packages to further incentivize breastfeeding and increased funding for lactation support programs.

2010s to Today

In the past two decades, breastfeeding indicators have consistently improved, though differences across population groups persist. In addition, the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010 contributed to the first national-level approach to provide workplace protections for breastfeeding mothers as well as insurance payment for breastfeeding supplies and support services (see Chapter 6). The Surgeon General’s Call to Action outlined strategies for addressing barriers, such as workplace policies and healthcare access (HHS, 2011). Public campaigns such as “It’s Only Natural” launched in 2014, aiming to normalize breastfeeding among African American mothers, addressed cultural and structural obstacles by fostering positive perceptions and community support for breastfeeding (Office on Women’s Health, 2022). In 2018, with the enactment of legislation in Idaho and Utah, breastfeeding in public became legal in all 50 U.S. states (Idaho Legislature, 2018; Utah Legislature, 2018), marking a key step toward reducing stigma and creating a supportive environment for breastfeeding mothers. By 2020, breastfeeding initiation rates reached a record high of 84.1%, reflecting ongoing efforts to promote and support breastfeeding across diverse communities (e.g., including the BFHI in the Healthy People 2020 goals; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021).

In 2022, the infant formula shortage underscored the critical role of breastfeeding in food security (Asiodu, 2022; National Academies, 2024; Tomori, 2023; Tomori & Palmquist, 2022). The same year, the Providing Urgent Maternal Protections (PUMP) for Nursing Mothers Act (2022) expanded workplace protections for lactating mothers, ensuring that more employees have access to time and private spaces for expressing milk (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021). In addition, the Pregnant Workers Fairness Act (2022) took effect in 2023 (U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 2023), mandating reasonable accommodations to workers experiencing limitations related to pregnancy, childbirth, or associated medical conditions. (For information on these and other relevant laws, see Box 4-1 in Chapter 4).

Another recent milestone in the history of breastfeeding and lactation support was the update in clinical guidelines related to HIV and breastfeeding. HHS (2023) revised its guidance to emphasize a shared

decision-making model in relation to infant feeding options for mothers and people living with HIV. Prior to the updated guidelines, breastfeeding had been contraindicated for mothers and people living with HIV in the United States for nearly 40 years (Abuogi et al., 2024). However, current recommendations support breastfeeding for women and individuals on effective antiretroviral therapy with sustained undetectable viral loads (Abuogi et al., 2024). This has been a recent and notable change in clinical practice (Gross et al., 2019).

In summary, the history of breastfeeding in the United States reflects a complex interplay of sociocultural, medical, economic, and policy-driven forces. From community roots to large-scale disruption driven by exploitation, industrialization, medicalization, and marketing, and its eventual revival through advocacy and institutional support, breastfeeding practices have been shaped by broader sociohistorical transformations (Tomori et al., 2022a). While progress has been made to reestablish breastfeeding, persistent differences by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status highlight the need for continued attention to address barriers, facilitators, and variances in access, especially for groups with low rates of breastfeeding. Understanding this historical trajectory offers necessary insights into the sociocultural and structural factors that continue to influence breastfeeding today.

Conclusion 3-1: While overall breastfeeding rates in the United States have improved since their nadir in the 1970s, they remain below recommended levels and Healthy People 2030 goals. Significant differences persist across racial/ethnic, geographic, and socioeconomic lines. The current rates reflect both gains and persistent challenges shaped by historical, cultural, and policy influences. Addressing these differences requires a multifaceted approach that includes coordinated surveillance of breastfeeding outcomes and expansion of current data collection systems. Also required is leadership of a national breastfeeding strategy that coordinates federal, state, tribal, and local partners, as well as community groups, health care systems, insurers, workplaces, and academic institutions.

CONFLICTING CULTURAL PERCEPTIONS OF BREASTFEEDING

As the historical discussion above suggests, a lack of comprehensive, structural support available to all families so that they may meet their personal and/or national breastfeeding goals has meant that, though the biological norm for humans, in many U.S. communities, breastfeeding is no longer the cultural norm. In addition, Tomori (2025) and Wolf (2001) have described how evolving cultural perceptions and attitudes in the United States about breastfeeding have created an environment in which community support and knowledge about breastfeeding are no longer

ubiquitous and universally passed down or diffused across generations. Freeman (2018) attributed this gap in generational knowledge and support to the influence of commercial milk formula marketing and messaging, as well as historical oppression and racism, which have created variances that have persisted over decades in national breastfeeding rates.

As discussed in Chapter 1, many women in the United States want to breastfeed and believe it is the best way to feed their babies. At the same time, they may feel conflicted by public health recommendations and the realities of breastfeeding in the absence of adequate support. Popular narratives identified in the scientific literature about breastfeeding highlight that it is a healthy and recommended practice but frame it as an individual “choice” and a moral responsibility, devoid of context (see Reyes-Foster & Carter, 2018; Tomori, 2025).

Earlier public health messaging using the language of breastfeeding as “best” has been pervasively critiqued for these moralized narratives (Hausman, 2013; Knaak, 2006; Wolf, 2010). Positioning breastfeeding as “best” can also lead women to view it as extraordinary, a practice that requires perfection and is unattainable—and a marker of privilege and social class (Carter & Anthony, 2015; Tomori, 2025; Wilson, 2018). Such moralized narratives link breastfeeding to “good motherhood,” which may lead women to internalize structural failures. Bresnahan et al. (2020a) suggested that this can lead to stigmatization of formula feeding and can be harmful for maternal mental health, especially for those who intended to breastfeed but were unable to do so. Tomori (2025) and Tomori et al. (2018) describe how moralized narratives can also create negative perceptions of breastfeeding advocacy, associating it with moral judgment and thereby undermining public health efforts.

Importantly, there is also a gap between the cultural ideal of breastfeeding and the perception of its actual practice. For instance, Bresnahan et al. (2020) and Grant et al. (2022) have stated that despite its protected status, breastfeeding in public remains stigmatized. Tomori et al. (2016) pointed out that breastfeeding women regularly report discomfort, judgment, and even harassment because of their breastfeeding. In addition, Owens et al. (2018) and Villabolos et al. (2021) noted that racialized attitudes and beliefs can amplify scrutiny and perceptions of stigmatization. Asiodu (2022) and Davis (2023) also noted that false and race- or class-based assumptions about mothers can directly undermine breastfeeding, such as in the case of undesired and unnecessary supplementation with formula. Moreover, breastfeeding that does not adhere to a narrow set of cultural expectations can also be stigmatized (Tomori et al., 2016; Walks, 2018; Wilson, 2018).

Even as breastfeeding has become more common, formula feeding remains a cultural norm against which breastfeeding is often measured (Hausman, 2013, 2014; Tomori, 2025; Tomori et al., 2018). Some

modern examples include bottle emojis and symbols that are widely used to signify infants, or the language of breastfeeding “benefits,” with formula feeding as the baseline comparator. In addition, Pérez-Escamilla et al. (2023) find that parents as well as health professionals may remain unfamiliar with the typical human behavior of a breastfed infant. Tomori (2015) describes how typical behaviors of frequent breastfeeding, for instance, violate social expectations in multiple ways, because of the sexualization of breasts and because frequent feeding can also be misinterpreted as signs of excessive “dependence” or a starving baby. The simultaneous stigmatization of both formula feeding and breastfeeding coexist, reflecting a fragmented cultural landscape of infant feeding in the United States.

Those seeking to care for their babies do not benefit from these discourses. Hastings et al. (2020) found that moralization of infant feeding has been used as a key theme by the commercial milk formula industry in its marketing efforts, seeking to heighten tensions by depicting breastfeeding mothers as judgmental. Simultaneously, the authors find that the use of individualistic framing in marketing shifts attention away from the structural drivers of breastfeeding challenges (Hastings et al., 2020). It may also build on critiques of breastfeeding and associated infant formula feeding with “choice,” and “freedom” (Hastings et al., 2020; Hausman, 2008). Given this cultural landscape, community supports for breastfeeding may be particularly important.

COMMUNITY SUPPORTS FOR BREASTFEEDING FAMILIES

Rollins et al. (2016) conducted a meta-analysis of international interventions to improve breastfeeding practices; they reported that community-based interventions, including group counseling or education and social mobilization, increased breastfeeding initiation by 86% (95% CI: 33%–159%) and exclusive breastfeeding by 20% at six months (95% CI: 3%–39%). Although they did not identify studies on the effect of community-led interventions on breastfeeding rates over time, their publication presents evidence on the importance of breastfeeding promotion as a societal responsibility—not the sole responsibility of the mother or family (Rollins et al., 2016). Consistent with these findings, Pérez-Escamilla et al. (2023) identified evidence-based interventions across all levels of the social ecological model (see Figure 3-1). Especially important were supportive workplace policies, implementation of the BFHI, skin-to-skin care, kangaroo mother care, and cup feeding in health care settings. The study also emphasized the importance of continuity of care and support in community and family settings via home visits delivered by community health workers or peer counselors (Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2023). It also explained the importance of support from fathers, grandmothers, and the

community at large (Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2023; Tomori et al., 2022a). Segura-Pérez et al. (2021) reached similar conclusions in their systematic review of breastfeeding interventions among underserved communities in the United States.

Community members, institutions, and organizations can provide social support and encouragement, education about breastfeeding, and advocacy for policies that protect the rights of breastfeeding mothers. They can also bridge resource gaps to ensure that families have the supplies and services they need. In addition, community attitudes, norms, and traditions can influence breastfeeding knowledge and practices. Public health programs and investments (see Chapter 5); media, messaging, and marketing campaigns (see Chapter 5); health care services, insurance, and payment for support services (see Chapters 6 and 7); and employers and schools (see Chapter 8) all operate within and interact with various community contexts.

Thus, communities have multiple opportunities to engage in breastfeeding support, including creating breastfeeding-friendly environments in public spaces and the built environment of health care settings, workplaces, schools, and even transit systems. Structural influences, such as community safety, accessible lactation spaces, and safe housing, can impact breastfeeding outcomes. Community identities vary; they can encompass geographic contexts, shared cultural or ethnic identities, or virtual communities with shared goals or beliefs. Importantly, communities are resilient, and members of a community will creatively access the resources and supports they need. If those supports are not available, they may seek out alternatives, lead initiatives to meet those needs, or seek out alternatives to breastfeeding (e.g., commercial milk formula).

National and State Organizations

In 1995, the U.S. Breastfeeding Committee (USBC; n.d.) was formed as an independent nonprofit organization that aims to “to drive collaborative efforts for policy and practices that create a landscape of breastfeeding support across the United States” (para. 2). The USBC is a critical convener for national breastfeeding advocacy, ensuring that policy, funding, and community-driven initiatives are aligned to create a more breastfeeding-friendly society. USBC advocates for federal policies that support mothers, families, and communities in reaching their breastfeeding goals. It also monitors legislation and funding decisions at the national and state levels and serves as an umbrella organization uniting over 100 national, state, territorial, and tribal organizations. The USBC provides technical assistance to breastfeeding coalitions and disseminates scientific research and best practices across its network. By uniting professionals and practitioners, pushing

for legislative changes, and expanding access to support, the USBC (n.d.) plays a fundamental role in breastfeeding support in the United States.

All 50 states have established breastfeeding coalitions, many of which receive technical assistance, web-based communication support, and participation opportunities in a biannual conference facilitated by the USBC. Additionally, numerous local, tribal, and territorial coalitions contribute to breastfeeding advocacy and support at the community level. These coalitions serve as critical drivers of state and local initiatives aimed at promoting and sustaining breastfeeding practices.

Interpersonal Support

Lactation support providers offer proactive breastfeeding education and support, engage mothers within their communities to share evidence-based guidance, and are often integrated into various community and health care settings to enhance access to their services. In addition, fathers, partners, family members, friends, and peers play a crucial role in influencing a mother’s decision to initiate and sustain breastfeeding (Pérez-Escamilla, 2022).

Lactation Support Providers

Breastfeeding mothers and families may receive assistance from a variety of lactation support providers, each with different levels of training, expertise, and roles in the community. These providers range from credentialed medical professionals to trained peer counselors—their education, training, and certification may vary, as well as where they provide support (see Table 3-1).

In a call for standardization of terminology, Strong et al. (2023) suggested three categories for lactation personnel: (a) providers with the International Board Certified Lactation Consultant® (IBCLCs) designation are qualified to provide clinical lactation care; (b) counselor/educators (e.g., certified lactation counselors, certified lactation educators, others) provide education and counseling; and (c) peer supporters are required to have had personal breastfeeding experience. Strong et al. (2023) also suggested different training and certification requirements for each level.

Chapter 6 examines the role of lactation support providers within the health care system, including their interactions and overlap with medical professionals. This section will further explore their role within the community context. Table 3-1 outlines the various training, credentials, and programs undertaken by lactation consultants, breastfeeding counselors, peer counselors, and lactation educators for supporting mothers and families. For example, while IBCLCs offer specialized clinical expertise,

TABLE 3-1 Lactation Support Provider Descriptors

| Category | Descriptions | Training | Credentials and Programs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lactation Consultants | Referral to these health professionals is appropriate for the full range of breastfeeding care, particularly involving high acuity breastfeeding situations. Often work clinically as part of the healthcare team in both inpatient and outpatient settings; may also work in private practice |

90–95 didactic hours, and additional training requirements and exam for each title. |

International Board Certified Lactation Consultant® (IBCLC) Program accreditation by Nat’l Commission for Certifying Agencies (NCCA)

Advanced Lactation Consultants® (ALC)

Advanced Nurse Lactation Consultants® (ANLC)

|

| Breastfeeding Counselors | Individuals who hold these certifications or similar have the skills to provide breastfeeding counseling, address normal breastfeeding in healthy term infants, and to conduct maternal and infant assessments of anatomy, latch, and positioning, while providing support. Often provide support to families in the hospital and community settings. Counselors may have additional competencies to assist families with breastfeeding difficulties. |

45–95 hours of classroom training and exam. The Indigenous Lactation Counselor and Military Lactation Counselor do not have exams. |

Certified Breastfeeding Specialists® (CBS)

Certified Lactation Counselors® (CLC)

Indigenous Lactation Counselor

Military Lactation Counselor® (MLC)

|

| Category | Descriptions | Training | Credentials and Programs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breastfeeding Peer Counselors | Breastfeeding peer support organizations equip these LSPs to meet the needs of the families they serve, focusing primarily on individual and community support | Personal breastfeeding experience and approximately 20 hours of training through various community models, except for the La Leche League Leader program, which has 90 hours of training. | Peer support organizations equip these LSPs to meet the needs of the families they serve, focusing primarily on individual and community support. Examples of national breastfeeding peer counselor organizations in the U.S. include: Breastfeeding USA CAPPA HealthConnect One La Leche League USA Reaching Our Sisters Everywhere Women, Infants, and Children |

| Lactation Educators | Qualified to support and educate on breastfeeding and related issues. Does not perform clinical care. | 45 hours for CLE of training, and exam. 20 hours LE of training, and exam. |

Certified Lactation Educators® (CLE)

Community Lactation Educator (LE)

|

NOTE: This resource is supported by Cooperative Agreement Number, 6NU39OT000167-05-03, funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the CDC or the Department of Health and Human Services. The American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Obstetrician and Gynecologists, American Academy of Family Physicians, and the U.S. Breastfeeding Committee – affiliated Lactation Support Provider (LSP) Constellation, support this document as an educational tool.

SOURCE: USBC, 2021.

peer counselors and community groups offer practical guidance and emotional support, helping to bridge the gap between clinical and community-based breastfeeding support.

International Board Certified Lactation Consultants® (IBCLCs)

Over 20,000 IBCLCs are certified in the United States (International Board of Lactation Consultant Examiners, 2025). IBCLCs primarily work in clinical settings, where they support breastfeeding during the prenatal, postpartum, and neonatal periods. They may also receive specialized training to assist with preterm, critically ill, or medically vulnerable infants, particularly in neonatal intensive care units and other hospital environments. Some IBCLCs work in private practice, where their services may be paid under the ACA. Others are employed in public health and community settings, providing in-home counseling and personalized breastfeeding support through existing maternal and child health programs. IBCLCs have been shown to positively impact breastfeeding outcomes (Chetwynd et al., 2019; Haase et al., 2019; Patel & Patel, 2016; Thurman & Allen, 2008).

Breastfeeding Peer Counseling

Breastfeeding peer counselors also play a crucial role in helping breastfeeding dyads initiate and sustain breastfeeding. However, determining the exact number of breastfeeding peer counselors in the United States is challenging because of variations in program implementation and reporting across states and localities. Precise data on the number of peer counselors are not readily available, but these professionals serve as key support providers, helping to promote, encourage, and sustain breastfeeding practices nationwide. WIC plays a particularly important role as the largest provider of breastfeeding peer counseling services.

Breastfeeding peer counseling has consistently been shown to be an effective intervention for improving breastfeeding outcomes in the United States and abroad (Chapman et al., 2010; Kaunonen et al., 2012; Patnode et al., 2016; Shakya et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2024; see Annex Table 3-2). For instance, peer support is key to the WIC breastfeeding support services found to be positively associated with breastfeeding outcomes in New York (Assibey-Mensah et al., 2019) and Minnesota (Interrante et al., 2024; see also Chapter 5). Mothers are reported to value breastfeeding peer counseling highly (Rhodes et al., 2024; Yang et al., 2024). Based on the extensive evidence available, the WHO’s (2018) breastfeeding counseling guideline and corresponding implementation recommendations (United Nations Children’s Fund & World Health Organization, 2021) highlight the key role of peer counselors in providing adequate breastfeeding care in communities.

In the United States, breastfeeding counselors have been trained with diverse evidence-based curriculums but are not certified. They are usually supervised by lactation support providers, including IBCLCs.

The Community Impact of Lactation Support Providers

In their review, Patel and Patel (2016) found that breastfeeding interventions using breastfeeding peer counselors and lactation consultants increase the likelihood of initiating breastfeeding, any breastfeeding rates, and exclusive breastfeeding rates. Likewise, Chetwynd et al. (2019) found that interventions with lactation consultants improved any breastfeeding at six months; the pooled difference was an 8% higher absolute breastfeeding rate compared with standard of care. This finding translates into one additional case of any breastfeeding at six months postpartum for every 12 women who received an IBCLC intervention (Chetwynd et al., 2019). A scoping review by Haase et al. (2019) is consistent with the conclusion that IBCLCs are likely to have a positive impact on breastfeeding outcomes. These findings combined agree with the recommendation made by Thurman and Allen (2008), based on their integrative review, to integrate IBCLCs into both primary care and clinical lactation management services. These findings point to the value of incorporating peer counselors and IBCLCs into clinical and primary care settings.

D’Hollander et al. (2025) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of breastfeeding support provided by lactation consultants in high-income countries, distinguishing lactation consultants from all professional and peer breastfeeding supports (who were found to have beneficial effects on breastfeeding in previous reviews [e.g., Patnode et al., 2016]). The authors noted that breastfeeding interventions provided by lactation consultants reduced the relative risk of stopping exclusive breastfeeding by 4%, stopping any breastfeeding by 8%, and extending breastfeeding duration by approximately 3.6 weeks, compared with a usual standard of care (D’Hollander et al., 2025). As such, lactation consultants play an important, supportive role in interventions to improve exclusive and any breastfeeding. D’Hollander et al. (2025) highlighted the potential applicability of their results, noting previous randomized controlled trials that demonstrated positive effects of lactation consultation and support on breastfeeding rates in communities in the United States that experience unequal access to support and services (i.e., low-income Black and Hispanic families; Bonuck et al., 2005).

Conclusion 3-2: Breastfeeding mothers and families may receive assistance from a variety of lactation support providers, including peer counselors, each with different levels of training, expertise, and roles in the community. Across various specialties and scopes of practice, breastfeeding peer

counseling by lactation support providers is an effective intervention for promoting breastfeeding outcomes in the United States.

The Role of Family Members

Family members pass down generational beliefs, practices, and cultural norms, which can shape or reinforce attitudes related to breastfeeding (e.g., Woods Barr et al., 2021). These influences can either reinforce or conflict with public health or professional society recommendations.

For example, Johnson et al. (2015) conducted a systematic review of psychosocial interventions aimed at improving breastfeeding initiation and duration rates among African American mothers. The authors included three studies (i.e., two randomized controlled trials and one mixed-method design) assessing interpersonal factors that may enhance breastfeeding, including the impact of (a) peer support for mothers during the prenatal period, (b) peer-led education provided to expectant fathers, and (c) the influence of previous family breastfeeding experience. The study results consistently showed that informal supports (e.g., a mother’s partner and family) are important for promoting breastfeeding in predominately African American communities (Johnson et al., 2015).

In a meta-analysis, Rollins et al. (2016) identified that home- and family-based interventions focused on mothers, fathers, and other family members at home were effective at improving exclusive breastfeeding, continued breastfeeding, and any breastfeeding. In addition, they tended to show improvements in early breastfeeding initiation (Rollins et al., 2016).

Breastfeeding support must be adaptable to meet the diverse needs of American families, who bring varied cultural backgrounds, experiences, and social contexts to their breastfeeding practices (USDA, n.d.). Family structures have evolved over time, reflecting shifts such as delayed childbearing, increasing racial/ethnic diversity, and changing household compositions (Aragão et al., 2023; U.S. Census Bureau, 2023). Today, more than half of all children in the United States are children of color, and a quarter have an immigrant parent (Children’s Defense Fund, 2023; U.S. Census Bureau, 2023). Additionally, economic variances remain a significant factor, with one in six children living in poverty and nearly half of all infants qualifying for WIC (U.S. Census Bureau, 2023). Given this diversity, breastfeeding support programs may be tailored to the unique needs of different communities.

Fathers and Partners

Fathers and partners have a critical role in supporting breastfeeding, including providing emotional and practical support, as well as advocating and solving problems for the breastfeeding dyad. Research has shown that

partner support plays a crucial role in breastfeeding outcomes, influencing initiation, exclusivity, and duration (Mörelius et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2024). Studies suggest that when partners are actively involved—providing encouragement, assisting with infant care, and supporting breastfeeding decisions—mothers are more likely to start and sustain breastfeeding (e.g., Hunter & Cattelona, 2014). Understanding the impact of partner involvement can help shape effective interventions that enhance breastfeeding success and promote shared family support in infant feeding (Rios et al., 2024).

The Surgeon General’s Call to Action highlights the importance of educating fathers and grandmothers about breastfeeding as a key action step to support breastfeeding (HHS, 2011). And the Continuity of Care Breastfeeding Blueprint highlights the importance of including family members that have a direct influence on parents’ feeding decisions and actions (National Association of County and City Health Officials, 2021).

For example, a meta-analytic review conducted by Zhou et al. (2024) reviewed the existing international evidence related to the impact of paternal support interventions on breastfeeding. Interventions focused on fathers during the first three months postpartum were found to strengthen a mothers’ intention to breastfeed exclusively. In addition, paternal attitudes have been shown to have a significant and positive effect on maternal exclusive breastfeeding for six months (Zhou et al., 2024). Additional evidence from a randomized controlled trial in Sweden suggests that involving fathers in skin-to-skin contact and early breastfeeding initiation can positively influence breastfeeding outcomes as well as maternal recovery postpartum (Mörelius et al., 2015).

Fathers and partners experience many of the constraints that mothers do, including challenges balancing professional and familial responsibilities, a lack of paid family leave, and limited knowledge that may be further exacerbated by insufficient education and guidance from health care providers, family members, or societal norms (Zhou et al., 2024). Currently, no large-scale public health surveillance system exists to better understand the health and behaviors of men who become fathers (Garfield et al., 2022). Emerging efforts, such as adapting the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) to include fathers (i.e., “PRAMS for Dads”), are underway to better understand survey and sampling methodology, father health and health care characteristics and behaviors, and the public health implications and importance of fathers’ involvement in their family’s lives (Garfield et al., 2022).

Special Considerations

The United States has the highest rate of incarcerated women in the world; this includes a significant number of women of childbearing age (Carson, 2020). Breastfeeding while incarcerated poses unique challenges

and can impact maternal and infant health (Asiodu et al., 2021). However, there have been community-led efforts to support lactating mothers in jail and prison settings. Policies and community programs are evolving to address the needs of incarcerated pregnant and postpartum women and individuals (Asiodu et al., 2021). These policies and programs include state legislation, birth doulas, pump and pick up programs, prison nursery programs, and community-based alternatives to incarceration; these may help to facilitate breastfeeding and/or access to human milk during separation due to incarceration (Wilson et al., 2022).

Conclusion 3-3: Community supports, peer networks, and family members play a critical role in protecting, supporting, and sustaining breastfeeding. Through culturally tailored interventions, policy advocacy, and integrated models of care, these community-based efforts provide essential infrastructure for meeting the diverse needs of families and advancing breastfeeding outcomes across populations.

Recommendation 3-1: Given evidence from burgeoning literature on community-led breastfeeding efforts, Congress; federal, state, and tribal governments; health systems; insurance companies; and philanthropic organizations should fund and establish cross-sector, coordinated investment strategies for supporting community-led breastfeeding programs and coalitions across all local jurisdictions, states, territories, and tribes.

The committee recommends a cross-sector approach for funding community-led breastfeeding efforts (e.g., programs and coalitions) to ensure that they continue. Evidence from previous multisector approaches shows that coordinated investment strategies for supporting community-led breastfeeding programs and coalitions can work may require complex, adaptive systems using implementation science1 (e.g., Cresswell et al., 2019; Pérez-Escamilla & Hall Moran, 2016; Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2012; Rollins et al., 2016).

Community-led programs and coalitions play a critical role in breastfeeding support, particularly in historically underserved communities (Asiodu et al., 2021; Burnham et al., 2022; Merewood et al., 2019; Rollins et al., 2016; Ware et al., 2021). These programs are often developed in response to cultural, social, and structural barriers that may prevent mothers from initiating or sustaining breastfeeding (Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2023;

___________________

1 Implementation science is “an interdisciplinary body of theory, knowledge, frameworks, tools and approaches whose purpose is to strengthen implementation quality and impact” (Tumilowicz et al., 2018, p. 1).

Rollins et al., 2016). Many mothers may feel more comfortable receiving breastfeeding guidance from community members who share their background, life experiences, or language. Moreover, community-led initiatives are often embedded within the places where families live, making support accessible and building trust among neighbors. These programs can also empower families with resources, education, and support to sustain breastfeeding and support others who encounter similar barriers and challenges. Overall, community-led breastfeeding programs and coalitions can bridge gaps in breastfeeding services and supplies, offer culturally congruent support, and provide guidance to families so that they may make informed infant feeding decisions. These programs play a key role in reducing breastfeeding variances and catalyzing community-level change.

Investing in community-led breastfeeding programs and coalitions can build on and amplify the efforts of the USBC by enhancing coordination, stimulation, and sustained support for these initiatives. To ensure continuity of care, the USBC could also seek funding from a range of sources, including the Title V Maternal and Child Health Services Block Grant (distributed by states), the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Healthy Start Initiative, CDC’s State Physical Activity and Nutrition Program, the Indian Health Service, and private foundations or philanthropic organizations (National Association of County & City Health Officials, 2021).

PROMISING COMMUNITY APPROACHES

Throughout its deliberations, the committee identified promising approaches and programs, including the development of breastfeeding-friendly criteria. In addition, it highlighted community-driven solutions for reducing breastfeeding variances through peer and professional support.

There are multiple definitions, domestically and internationally, of breastfeeding friendly in the community setting (Tan et al., 2024). However, scientists have sought to identify a common set of criteria or indicators of a breastfeeding-friendly city, using an approach like that used to establish the BFHI’s Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding in the health care setting (Tan et al., 2024; see also Chapter 6). Tan et al. (2024) led a scoping review to identify published descriptions of breastfeeding-friendly settings in the existing literature. They identified two country-level indicators, the World Breastfeeding Trend Initiative (a reporting tool) and the Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly Index, a self-assessment tool for countries to use to assess their readiness to scale-up breastfeeding initiatives (Gupta et al., 2019; Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2018). In addition to the two country-level indicators, Tan et al. (2024) identified 24 sets of breastfeeding-friendly criteria across seven community entities: airports, businesses, childcare, education, public space, places of workshop, and homeless shelters.

Domestically, there have been efforts to pilot multilevel interventions to strengthen breastfeeding support during critical transitions. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action in 2011 identified a clear need for action at the level of the community because of a variety of practical and structural factors in the United States (HHS, 2011). To address this need, in 2015, the Breastfeeding Family Friendly Community (BFFC) designation was piloted to bring together academic institutions, interfaith organizations, community breastfeeding groups, and local policymakers and decision-makers with the shared goal of expanding breastfeeding-friendly practices in Chapel Hill and Carrboro, North Carolina (The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, n.d.). The BFFC offered an expansion of the WHO and UNICEF Ten Steps for Successful Breastfeeding and provided a complementary set of the Ten Steps (Breastfeeding Family Friendly Community Designation, 2022) To date, communities from the states of Indiana, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Wisconsin have committed to implementing Ten Steps to a Breastfeeding Family Friendly Community and used the provided framework, approaches, and measures to self-designate as Breastfeeding Friendly (Breastfeeding Family Friendly Community Designation, 2022). These ten steps identify as key actors the community’s elected or appointed leadership, community members, health systems and health care leadership, community-led breastfeeding support groups, local businesses and organizations, and the education system.

Additional research is needed to identify and agree on a set of criteria for determining “breastfeeding-friendly” community actions. However, there is a growing evidence base that can be leveraged by public health leaders, community coalitions, and other key actors to create more supportive communities and environments for mothers and their infants.

REFERENCES

Abuogi, L., Noble, L., Smith, C., & Committee on Pediatric and Adolescent HIV Section on Breastfeeding (2024). Infant feeding for persons living with and at risk for HIV in the United States: Clinical report. Pediatrics, 153(6), e2024066843. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2024-066843

Anttila-Hughes, J. K., Fernald, L. C. H., Gertler, P. J., Krause, P., Tsai, E., & Wydick, B. (2018). Mortality from Nestlé’s marketing of infant formula in low and middle-income countries (NBER Working Paper No. 24452). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w24452

Apple, R. D. (1987). Mothers and medicine: A social history of infant feeding, 1890–1950 (1st ed., Vol. 7). University of Wisconsin Press.

Asiodu, I. V. (2022). Infant formula shortage: This should not be our reality. The Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing, 36(4), 340–343. https://doi.org/10.1097/JPN.0000000000000690

Asiodu, I. V., Bugg, K., & Palmquist, A. E. L. (2021). Achieving breastfeeding equity and justice in black communities: Past, present, and future. Breastfeeding Medicine, 16(6), 447–451. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2020.0314

Asiodu, I. V., Waters, C. M., Dailey, D. E., Lee, K. A., & Lyndon, A. (2015). Breastfeeding and use of social media among first-time African American mothers. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 44(2), 268–278. https://doi.org/10.1111/1552-6909.12552

Aragão, C., Parker, K., Greenwood, S., Baronavski, C., & Mandapat. (2023, September 14). The modern American family. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2023/09/14/the-modern-american-family/

Assibey-Mensah, V., Suter, B., Thevenet-Morrison, K., Widanka, H., Edmunds, L., Sekhobo, J., & Dozier, A. (2019). Effectiveness of peer counselor support on breastfeeding outcomes in WIC-enrolled women. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 51(6), 650–657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2019.03.005

Bentley, A. (2014). Inventing baby food: Taste, health, and the industrialization of the American diet. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/287064191_Inventing_baby_food_Taste_health_and_the_industrialization_of_the_American_diet

Bonuck, K. A., Trombley, M., Freeman, K., & McKee, D. (2005). Randomized, controlled trial of a prenatal and postnatal lactation consultant intervention on duration and intensity of breastfeeding up to 12 months. Pediatrics, 116(6), 1413–1426. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-0435

Boyd, K. (2012). (R)evolutionary health care. Infant, Child, & Adolescent Nutrition, 4(6), 332–333. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941406412466837

Braveman, P., Dominguez, T. P., Burke, W., Dolan, S. M., Stevenson, D. K., Jackson, F. M., Collins, J. W., Driscoll, D. A., Haley, T., Acker, J., Shaw, G. M., McCabe, E. R. B., Hay, W. W., Thorn-burg, K., Acevedo-Garcia, D., Cordero, J. F., Wise, P. H., Legaz, G., Rashied-Henry, K., . . . Waddell, L. (2021). Explaining the Black-White disparity in preterm birth: A consensus statement from a multi-disciplinary scientific work group convened by the March of Dimes. Frontiers in Reproductive Health, 3, 684207. https://doi.org/10.3389/frph.2021.684207

Breastfeeding Family Friendly Community Designation. (2022). Breastfeeding family friendly community designation. https://breastfeedingcommunities.org/wp-content/up-loads/2022/04/Global-Criteria_2022March.pdf

Bresnahan, M., Zhuang, J., Goldbort, J., Bogdan-Lovis, E., Park, S.-Y., & Hitt, R. (2020). Made to feel like less of a woman: The experience of stigma for mothers who do not breastfeed. Breastfeeding Medicine: The Official Journal of the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine, 15(1), 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2019.0171

Bugg, K., Asiodu, I. V., & Serano, A. (2024). Reckoning with resilience. Black Women and Resilience, 171–184.

Carson, E. A. (2020). Prisoners in 2018 (NCJ No. 253516). U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/p18.pdf

Carter, S. K., & Anthony, A. K. (2015). Good, bad, and extraordinary mothers: Infant feeding and mothering in African American Mothers’ breastfeeding narratives. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 1(4), 517–531. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332649215581664

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Breastfeeding Initiation—United States, 2019. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 70(21), 769–774. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7021a1

Chapman, D. J., Morel, K., Anderson, A. K., Damio, G., & Pérez-Escamilla, R. (2010). Breastfeeding peer counseling: From efficacy through scale-up. Journal of Human Lactation: Official Journal of International Lactation Consultant Association, 26(3), 314–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334410369481

Chetwynd, E. M., Wasser, H. M., & Poole, C. (2019). Breastfeeding support interventions by International Board Certified Lactation Consultants: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Human Lactation, 35(3), 424–440. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334419851482

Children’s Defense Fund. (2023). Child population. https://www.childrensdefense.org/tools-and-resources/the-state-of-americas-children/soac-child-population/

Crear-Perry, J., Correa-de-Araujo, R., Lewis Johnson, T., McLemore, M. R., Neilson, E., & Wallace, M. (2021). Social and structural determinants of health inequities in maternal health. Journal of Women’s Health, 30(2), 230–235. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2020.8882

Cresswell, J. A., Ganaba, R., Sarrassat, S., Somé, H., Diallo, A. H., Cousens, S., & Filippi, V. (2019). The effect of the Alive & Thrive initiative on exclusive breastfeeding in rural Burkina Faso: A repeated cross-sectional cluster randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Global Health, 7(3), e357–e365. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30494-7

D’Hollander, C. J., McCredie, V. A., Uleryk, E. M., Kucab, M., Le, R. M., Hayosh, O., Keown-Stoneman, C. D. G., Birken, C. S., & Maguire, J. L. (2025). Breastfeeding support provided by lactation consultants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 179(5), 508–520. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2024.6810

Davis, D. (2023). Uneven reproduction: Gender, race, class, and birth outcomes. Feminist Anthropology, 4(2), 152–170. https://doi.org/10.1002/fea2.12129

DeVane-Johnson, S., Giscombe, C. W., Williams, R., Fogel, C., & Thoyre, S. (2018). A Qualitative Study of Social, Cultural, and Historical Influences on African American Women’s Infant-Feeding Practices. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 27(2), 71–85. https://doi.org/10.1891/1058-1243.27.2.71

Dinour, L. M., Rivera Rodas, E. I., Amutah-Onukagha, N. N., & Doamekpor, L. A. (2020). The role of prenatal food insecurity on breastfeeding behaviors: Findings from the United States pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system. International Breastfeeding Journal, 15(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-020-00276-x

Feldman-Winter, L., Ustianov, J., Anastasio, J., Butts-Dion, S., Heinrich, P., Merewood, A., Bugg, K., Donohue-Rolfe, S., & Homer, C. J. (2017). Best fed beginnings: A nationwide quality improvement initiative to increase breastfeeding. Pediatrics, 140(1), e20163121. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-3121

Fraser, G. J. (1998). African American midwifery in the South: Dialogues of birth, race, and memory. Harvard University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv1rr6csx

Freeman, A. (2018). Unmothering Black women: Formula feeding as an incident of slavery. Hastings Law Journal, 69(1545), 1545–1606.

Garfield, C. F., Simon, C. D., Stephens, F., Castro Román, P., Bryan, M., Smith, R. A., Kortsmit, K., Salvesen von Essen, B., Williams, L., Kapaya, M., Dieke, A., Barfield, W., & Warner, L. (2022). Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System for Dads: A piloted randomized trial of public health surveillance of recent fathers’ behaviors before and after infant birth. PLoS One, 17(1), e0262366. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0262366

Grant, A., Pell, B., Copeland, L., Brown, A., Ellis, R., Morris, D., Williams, D., & Phillips, R. (2022). Views and experience of breastfeeding in public: A qualitative systematic review. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 18(4), e13407. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.13407

Green, V. L., Killings, N. L., & Clare, C. A. (2021). The historical, psychosocial, and cultural context of breastfeeding in the African American community. Breastfeeding Medicine: The Official Journal of the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine, 16(2), 116–120. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2020.0316

Gross, R. S., Mendelsohn, A. L., Fierman, A. H., Racine, A. D., & Messito, M. J. (2012). Food insecurity and obesogenic maternal infant feeding styles and practices in low-income families. Pediatrics, 130(2), 254–261. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-3588

Gross, R. S., Mendelsohn, A. L., Arana, M. M., & Messito, M. J. (2019). Food insecurity during pregnancy and breastfeeding by low-income Hispanic mothers. Pediatrics, 143(6), e20184113. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-4113

Grummer-Strawn, L. M., Shealy, K. R., Perrine, C. G., MacGowan, C., Grossniklaus, D. A., Scanlon, K. S., & Murphy, P. E. (2013). Maternity care practices that support breastfeeding: CDC efforts to encourage quality improvement. Journal of Women’s Health, 22(2), 107–112. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2012.4158

Gupta, A., Suri, S., Dadhich, J. P., Trejos, M., & Nalubanga, B. (2019). The World Breastfeeding Trends Initiative: Implementation of the global strategy for infant and young child feeding in 84 countries. Journal of Public Health Policy, 40(1), 35–65. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41271-018-0153-9

Haase, B., Brennan, E., & Wagner, C. L. (2019). Effectiveness of the IBCLC: Have we made an impact on the care of breastfeeding families over the past decade? Journal of Human Lactation, 35(3), 441–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334419851805

Haley, C. O., Gross, T. T., Story, C. R., McElderry, C. G., & Stone, K. W. (2023). Social media usage as a form of breastfeeding support among Black mothers: A scoping review of the literature. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 68(4), 442–448. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmwh.13503

Hastings, G., Angus, K., Eadie, D., & Hunt, K. (2020). Selling second best: How infant formula marketing works. Globalization and Health, 16, Article 77. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00597-w

Hausman, B. L. (2008). Women’s liberation and the rhetoric of “choice” in infant feeding debates. International Breastfeeding Journal, 3, 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4358-3-10

———. (2013). Breastfeeding, rhetoric, and the politics of feminism. Journal of Women, Politics & Policy, 34(4), 330–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/1554477X.2013.835673

———. (2014). Mother’s milk: Breastfeeding controversies in American culture (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Houghtaling, B., Byker Shanks, C., Ahmed, S., & Rink, E. (2018). Grandmother and health care professional breastfeeding perspectives provide opportunities for health promotion in an American Indian community. Social Science & Medicine, 208, 80–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.05.017

Hunter, T., & Cattelona, G. (2014). Breastfeeding initiation and duration in first-time mothers: Exploring the impact of father involvement in the early post-partum period. Health Promotion Perspectives, 4(2), 132–136. https://doi.org/10.5681/hpp.2014.017

Idaho Legislature. (2018). House Bill 448: Public indecency exemptions for breastfeeding (Chapter 19, 2018 Idaho Session Laws). https://legislature.idaho.gov/sessioninfo/2018/legislation/H0448

International Board of Lactation Consultant Examiners. (2025, March 25). IBCLCs in the USA & territories: Statistical report (Data as of March 25, 2025). IBLCE.

Institute of Medicine. (1991). Nutrition during lactation. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/1577.

Interrante, J. D., Fritz, A. H., McCoy, M. B., & Kozhimannil, K. B. (2024). Effects of breastfeeding peer counseling on county-level breastfeeding rates among WIC participants in Greater Minnesota. Women’s Health Issues: Official Publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women’s Health, 34(3), 232–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2023.12.001

Johnson, A., Kirk, R., Rosenblum, K. L., & Muzik, M. (2015). Enhancing breastfeeding rates among African American women: A systematic review of current psychosocial interventions. Breastfeeding Medicine, 10(1), 45–62. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2014.0023