Breastfeeding in the United States: Strategies to Support Families and Achieve National Goals (2025)

Chapter: 4 Federal and State Policies and Programs: Coordinating Public Health Approaches and WIC

4

Federal and State Policies and Programs: Coordinating Public Health Approaches and WIC

Breastfeeding rates in the United States are shaped by policy environments, resource allocation, and the design and implementation of federal and state-level public health infrastructure. These decisions influence not only the material and informational support available to mothers and families but also the broader sociopolitical context in which infant feeding decisions are made.

This chapter examines the interplay between federal and state policies and programs, public health surveillance systems, and programmatic investments as determinants of infant feeding environments. In particular, it describes the separation that exists between the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), two federal departments that administer programs and policies to serve mothers and infants. The chapter also considers the central role of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), including the history of the program and current breastfeeding-related supports. Finally, it explores how the public health system can build and support community resilience in the face of disasters, emergencies, and supply chain disruptions that affect infant feeding.

FEDERAL AND STATE PROGRAMS THAT PROMOTE BREASTFEEDING

Federal programs that support low-income mothers and infants are administered across multiple agencies, reflecting a division of responsibilities that has evolved over time, with distinct legislative histories and administrative

structures. In particular, HHS and USDA have distinct but interrelated roles in promoting maternal and infant nutrition and supporting breastfeeding.

HHS

The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), part of HHS, integrates breastfeeding supports into several of its programs:

- Through the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting program, home visitors provide information on topics including breastfeeding and connect families to services and resources in their community, such as providers with International Board Certified Lactation Consultant® (IBCLC) and Certified Lactation Counselor designations. Data indicate that the percentage of infants receiving any breastmilk at age six months increased from an average of 41% in fiscal year (FY) 2021 to 44% in FY 2022 (Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau, 2023).

- The Title V Maternal and Child Health Services Block Grant program includes breastfeeding as one of its national performance measures and implements strategies for addressing breastfeeding initiation and duration.

- The Women’s Preventive Service Guidelines recommend comprehensive lactation support services, including counseling before and after pregnancy, to optimize the successful initiation and maintenance of breastfeeding, as well as access to breastfeeding equipment and supplies (Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau, 2023).

- The Healthy People 2030 goals include increasing the proportion of infants who are breastfed exclusively through age six months, from the baseline of 24.9% in 2015 to 42.4% by 2030 (Maternal Infant and Child Health [MICH]-15) and increasing the proportion of infants who are breastfed at 1 year from the baseline of 35.9% in 2015 to 54.1% by 2030 (MICH-16). There have been modest improvements in both measures since the Healthy People 2030 initiative began; as of 2021, the proportion of infants who were breastfed exclusively through age six months was 27.2%, and the proportion of infants who were breastfed at one year was 39.5%.

- The Healthy Start Program requires grant recipients to report on progress toward achieving the 10 Healthy Start benchmark goals, which include breastfeeding. The program also provides doula services at the community level, including lactation education and counseling to help with breastfeeding initiation and duration. Healthy Start also provides a Technical Assistance & Support Center; breastfeeding was one of the most commonly selected priorities

- by participants in 2022 (Amaka Consulting and Evaluation Services, LLC, 2024).

- The Children’s Healthy Weight State Capacity Building Program helps state Title V programs improve their knowledge, skills, and tools to successfully integrate public health nutrition. For example, the plan in Oregon includes culturally specific approaches to breastfeeding promotion and support for those partnering with tribal members or African American/Black and other communities of color (e.g., antiracism resources addressing breastfeeding), as well as promotion and support for laws and policies for pregnant and breastfeeding people in the workforce, with a focus on those facing additional barriers (Community Evaluation Solutions, 2022).

Also, within HHS, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provides breastfeeding recommendations and guidance for families, health care providers, and people in early care and education settings:

- The Enhancing Maternity Practices (EMPower) breastfeeding initiative (in partnership with Abt Associates, Baby-Friendly USA, the Carolina Global Breastfeeding Institute, and Population Health Improvement Partners) was a hospital-based quality improvement initiative to help hospitals improve breastfeeding-supportive maternity care and achieve the Baby-Friendly designation. It was the successor to Best Fed Beginnings, described below.

- CDC also provides strategies for continuity of care in breastfeeding and an aggregated list of toolkits from state breastfeeding programs. Previously, CDC funded Best Fed Beginnings (2011–2015), a nationwide quality improvement initiative led by the National Institute for Children’s Health Quality in partnership with Baby-Friendly USA and the U.S. Breastfeeding Committee (USBC). The goal was to help hospitals improve breastfeeding-supportive maternity care practices and increase the number of Baby-Friendly hospitals in the United States.

- The Communities and Hospitals Advancing Maternity Practices (CHAMPS) initiative helps hospitals increase exclusive breastfeeding rates, improve maternity care, and decrease racial variances.

Additionally, the National Institutes of Health provides consumer-facing information about the benefits of breastfeeding and the importance of breastfeeding to reduce sudden infant death syndrome. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA), in collaboration with CDC, provides tips on how to safely use, pump, and store human milk.

Finally, the HHS Office on Women’s Health (OWH) provides resources for employers about breastfeeding as well as the business case for breastfeeding.

The Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health, including OWH, recently supported the Reducing Disparities in Breastfeeding Innovation Challenge, a national competition to identify effective, preexisting programs that increase breastfeeding initiation and continuation rates and decrease variances in breastfeeding outcomes in the United States, and that demonstrate sustainability and the ability to replicate and/or expand.

USDA

In addition to WIC, which will be discussed later in this chapter, USDA supports the Child and Adult Care Feeding Program (CACFP), which provides monetary reimbursement to childcare providers for supporting breastfeeding. Specifically, CACFP providers receive reimbursement for meals and snacks when the mother has provided pumped human milk or has breastfed her baby at the childcare site, continuing beyond the child’s first birthday. CACFP also provides a training tool for CACFP operators with infants enrolled in their childcare site and covers topics such as handling and storing.

DOD

The U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) has standards and policies for accommodating breastfeeding among military personnel (Mayo, 2024). For example, in June 2024, DOD issued a new policy to cover costs associated with the shipment of human milk during a permanent change of station. Additionally, TRICARE Resources for Military Families include breastfeeding counseling at no cost through the Childbirth and Breastfeeding Support Demonstration (see Chapter 7).

State-Level Programs

In addition to these federal programs, numerous state-level programs aim to create supportive environments for breastfeeding. Examples include:

- Minnesota Breastfeeding-Friendly Health Departments Program1: This program provides a ten-step process and toolkit for supporting breastfeeding practices at local public health agencies and tribal health boards.

- North Carolina’s Maternity Center Breastfeeding-Friendly Designation: This program utilizes a five-star system, awarding a star for every two steps achieved within the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding (see Chapter 6 for discussion of the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative).

___________________

1 https://www.health.state.mn.us/people/breastfeeding/healthdpts.html

- Texas Mother-Friendly Worksite Program2: This program recognizes worksites that comply with “Mother-Friendly” criteria, including having a written and communicated policy. The criteria include space for human milk expression in the worksite, flexible work schedules for breastfeeding mothers, access to clean running water to wash hands and clean equipment, and access to hygienic human milk storage options.

- California’s 9 Steps to Breastfeeding Friendly: Guidelines for Community Health Centers and Outpatient Care Settings: This program supports community health centers and outpatient care settings to successfully implement practices and policies that protect, promote, and support breastfeeding. The guidelines provide a framework for creating and sustaining a community-based, universally accessible, quality care and support system for breastfeeding mothers and their families (California WIC Association, n.d.).

- Wisconsin’s Ten Steps to Breastfeeding Friendly Childcare Centers: These centers provide resources to help community partners assist childcare center employees and owners with providing accurate and consistent lactation support to breastfeeding families whose babies are in their care (Wisconsin Department of Health Services, 2023).

While the following programs are administered at the state level, many receive partial funding or technical assistance from federal sources. These initiatives often align with national priorities to promote and support breastfeeding, drawing on resources from agencies such as CDC, HRSA, and Title V Maternal and Child Health Block Grants. As such, they represent a collaboration between state public health systems and federal maternal and child health efforts to create supportive environments for breastfeeding families across diverse settings.

Opportunities for Coordination

As highlighted throughout this report, HHS leads a wide range of policies and programs that support breastfeeding families and has played a pivotal role in advancing breastfeeding and lactation support, as evidenced by the Surgeon General’s Workshop on Breastfeeding and Human Lactation (HHS, 1984), the HHS (2000) Blueprint for Action on Breastfeeding, and the Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding (HHS, 2011). The department sponsors a range of public health activities that address breastfeeding through (a) data collection and analysis (i.e., public

___________________

2 https://www.dshs.texas.gov/maternal-child-health/programs-activities-maternal-child-health/texas-mother-friendly-worksite

health surveillance, described below), (b) workforce development (e.g., provides funds for training and professional development for lactation support providers), and (c) insurance coverage of breastfeeding-related services and supplies (e.g., through Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program; see Chapter 7).

In addition, USDA, through WIC, provides direct nutritional support to eligible participants and serves nearly half of all infants born in the United States (Kessler et al., 2023). WIC offers a tailored food package, breastfeeding education, and referrals to health and social services (see later in this chapter). While the program is federally administered by USDA, it is typically implemented by state or local health agencies, many of which also receive HHS funding for related public health activities. Later sections situate WIC within this broader policy and programmatic context, highlighting how public health and nutrition programs intersect in their support for low-income families.

Importantly, the HHS and USDA programs have evolved over time in response to distinct legislative authorities, policy mandates, and administrative structures. This historical development occurred without a coordinated, comprehensive national strategy for breastfeeding support. While some shared objectives exist, such as promoting maternal and infant health, differences in program design, funding mechanisms, and eligibility criteria can contribute to challenges in service coordination.

The committee recognizes that this fragmentation may limit the efficiency and accessibility of services for families and communities. A key opportunity exists to strengthen collaboration and foster alignment across federal, state, and local efforts. Strategic coordination could enhance the reach and impact of breastfeeding-related programs, maximize use of existing resources, and improve continuity of care. Such alignment is central to the committee’s charge and underscores the importance of developing an overarching framework to guide future efforts (see Conclusion 4-1 and Recommendation 4-1).

LEGISLATION AND POLICIES THAT SUPPORT BREASTFEEDING

The federal government, territories, tribes, and states have all passed legal protections for breastfeeding. At the time of this report, the USBC (2025) tracks federal and state proposed bills by issue topic using OpenStreetMap software. In addition to tracking policy proposals, the USBC provides information on enacted federal policies (Box 4-1). There is no single federal law in the United States about breastfeeding in public, though the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978 prohibits discrimination based on pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions, which can include breastfeeding. Breastfeeding in public spaces is regulated by a

BOX 4-1

An Overview of Federal Breastfeeding Laws

Providing Urgent Maternal Protections for Nursing Mothers Act (2022)

- Makes changes to the Break Time for Nursing Mothers law and provides the right to break time and space to pump at work to millions of additional workers, including nurses and teachers.

- Allows workers to file a lawsuit to seek monetary remediation if an employer fails to comply with the law.

- Further clarifies that time spent pumping or expressing human milk must be paid if an employee is not relieved from their duty.

Pregnant Workers Fairness Act (2022)

- Provides reasonable accommodations for pregnancy, recovery from childbirth, and related medical conditions, including lactation, unless it presents undue hardship to employers.

- Protects employees from employer retaliation.

Friendly Airports for Mothers (FAM) Improvement Act (2020)

- Extends FAM Act provisions to small hub airports.

Fairness for Breastfeeding Mothers Act (2019)

- Requires certain public buildings with a public restroom to provide a lactation room, other than a bathroom, that is hygienic and available for use by members of the public.

- Extends the requirement that federal agencies provide a designated lactation space that is not a bathroom for employees to include visitors to federal buildings.

FAM Act (2018)

- Requires medium- and large-sized airports to provide a clean, private, nonbathroom space in each terminal for human milk expression or pumping.

- Includes requirements that the lactation space be accessible to individuals with disabilities; be available after each terminal’s security checkpoint; and provide seating, a flat surface, and an electrical outlet.

- Also requires airports to provide baby changing tables in each passenger terminal building in one men’s and one women’s restroom.

Bottles and Breastfeeding Equipment Screening Act (2016)

- Requires the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) to provide training to ensure officers consistently enforce TSA Special Procedures related to human milk, infant formula, and infant feeding equipment.

Safe Medications for Moms and Babies Act (2016)

- Established the Task Force on Research Specific to Pregnant Women and Lactating Women.

TRICARE Moms Improvement Act (2015)

- Remedied a gap in coverage for military families under TRICARE to provide payment for breastfeeding support, supplies, and counseling as a preventive service for women.

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (2010)

- Three provisions from this sweeping legislation directly impact breastfeeding supports, including changes to preventive services, workplace support, and funding for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s breastfeeding programs. See Chapters 6–8 for additional detail.

SOURCE: U.S. Breastfeeding Committee, 2023; see Table B-1 for more information.

series of policies addressing federal facilities and other public spaces and includes a mix of federal and state policies. At the federal level, the Fairness for Breastfeeding Mothers Act, signed in 2019, requires that certain public, federal buildings that contain a public restroom also provide a lactation room, other than a bathroom, that is hygienic and available for use by a member of the public. This law extended the requirement already in place for employees of federal agencies to include visitors to federal facilities.

State and Territory Breastfeeding Laws

Last updated in 2021, the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) provided an overview of laws enacted in states and U.S. territories related to breastfeeding. All states—alongside the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands—have passed laws that allow breastfeeding in public or private space (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2021). In addition, 31 states, Puerto Rico, the District of Columbia, and the Virgin Islands exempt breastfeeding from public indecency laws (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2021). Thirty states, Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbia have workplace-related breastfeeding laws in place, and 22 states and Puerto Rico either postpone or provide

exemptions to mothers from jury duty service (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2021). Additional statutes specific to individual states and territories dictate protections for supporting breastfeeding, including requirements for lactation spaces in public areas, schools, and childcare facilities; exemptions from state sales taxes on breastfeeding supplies; reimbursement for procuring human milk; provisions for midwifery and doula services for incarcerated women; required health insurance coverage for breastfeeding assistance and training; and the addition of warnings on marijuana and related products (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2021).

Tribal Policies for Supporting Breastfeeding

Native American women face multilevel barriers for breastfeeding, including shifting generational practices, lack of institutional resources, inadequate support from health care providers, and lack of institutional and community supports for breastfeeding (Doria & Liddell, 2024). Federal policies could address these barriers. These policies, including those related to protecting and promoting breastfeeding, could build from the strengths of Native American cultures (i.e., employ an assets-based perspective); this perspective would help address the enduring effects of historical disadvantage surrounding breastfeeding and build community and family resilience to that trauma (Monteith et al., 2024). These policies need to reflect traditional knowledge developed over millennia, recognizing their cultural beliefs and preferences. For policies to be effective they also need to be culturally sensitive and respectful. Breastfeeding protection, promotion, and support policies focusing on Native American communities could be developed or improved in the following domains: enculturation and Native American identity formation; traditional activities and games; relationships with land and Mother Earth; family social structures and the role of elders; languages; as well as spirituality and ceremonies (Aoki & Porter, 2021).

Tribal nations consider human milk to be a traditional first food that promotes health and prevents chronic disease among infants and mothers. Therefore it is important to empower them to exercise their sovereignty to support breastfeeding through policy. The goal of the First Food Policy and Law Scan study was to identify breastfeeding policies adopted by federally recognized tribes in the Bemidji Area of the Indian Health Service (IHS) in Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin. The researchers obtained information from 31 of 34 federally recognized tribes and identified 61 breastfeeding support policies, including 31 formal policies and 30 informal policies. The most common policies supported on-site milk expression or breastfeeding followed by human milk storage and use; only four policies identified breastfeeding as a right. Furthermore, regarding cultural sensitivity, only eight policies addressed Native American cultural norms and languages (Aoki & Porter, 2021).

The policies identified addressed supports for employees in gaming facilities; staff members, and to some extent, students and visitors in education settings; and patients, staff members, and to some extent community members (e.g., breast pump loan policy) in health settings. Policies on early childcare and education settings addressed supports for parents and providing human milk to babies in the program. Government policies included employee support policies, right-to-breastfeed resolutions, laws prohibiting discrimination against pregnant and nursing mothers, and a law clarifying that breastfeeding did not violate indecent exposure laws (Aoki & Porter, 2021).

Informal policies typically focused on providing private lactation spaces and related facilities (e.g., refrigerators for milk storage). Some informal policies reflected a community-wide approach, with contacts describing multiple lactation rooms available in several settings or multiple activities to support breastfeeding (e.g., educational campaigns, providing comfortable/private spaces at powwows and other community events; Aoki & Porter, 2021).

The IHS provides health services to approximately 2.2 million members of 567 federally recognized American Indian/Alaska Native tribes. The agency includes lactation support policies in its Health Manual (Indian Health Service, 2017). In addition to breastfeeding policies for health care systems, it includes a policy that “all managers and supervisors shall provide the support needed to allow time for nursing mother employees to pump and store human milk while on duty” under the authority of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (§ 4207; see Table B-1). The policy specifically calls for nursing women to have (a) reasonable break time to express milk for one year after her child’s birth each time such employee has need to express human milk, and (b) a clean private space, other than a bathroom, that is shielded from view and free from intrusion of others, to express human milk.

Conclusion 4-1: Multiple government agencies have initiatives and programs to support the breastfeeding dyad, but currently no single entity coordinates the patchwork of government programs into a cohesive road map of investments for the breastfeeding dyad to navigate easily. Coordination and funding across the public health system are limited and insufficient to ensure adequate and culturally competent support for all breastfeeding families.

Recommendation 4-1: Congress should charge and fund the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to lead a national breastfeeding strategy, coordinating with federal, state, tribal, and local partners, as well as community groups, health care and public health systems,

insurers, workplaces, and academic institutions to ensure that all mothers and families have access to effective and culturally centered breastfeeding support and resources to meet their breastfeeding goals.

At the time of this writing, HHS has the authority to lead a national breastfeeding strategy and the infrastructure to coordinate efforts among federal, state, tribal, and local partners, as well as the capacity to engage with a diverse range of stakeholders outside of government, including advocacy groups, community organizations, health care systems and providers, employers, and childcare providers. In addition, HHS can allocate federal funding to breastfeeding support programs and establish future breastfeeding-friendly policies and initiatives.

In addition, HHS can coordinate with other agencies and departments in the federal government that support relevant policies and programs, including USDA (e.g., WIC), the U.S. Department of Labor (e.g., workplace policies and protections), the FDA (e.g., labeling of commercial milk formula) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC; e.g., prohibiting deceptive advertising of commercial milk formula). A national strategy could better ensure coordination and integration of breastfeeding protection, promotion, and support across federally funded public health programs that engage women of childbearing age, infants, young children, and their families.

PUBLIC HEALTH SURVEILLANCE OF BREASTFEEDING INDICATORS

Currently, the public health surveillance of breastfeeding practices and support systems is conducted through several CDC programs:

- The National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Disease conducts annually the National Immunization Survey (NIS), which monitors breastfeeding rates by birth year at national and state levels.

- The National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) also maintains county-level data on breastfeeding at hospital discharge.

- The National Breastfeeding Report Card (conducted biannually) provides data on breastfeeding behaviors and environmental or policy support.

- The Pregnancy Risk Assessment and Monitoring System (PRAMS) is an ongoing, site-specific, population-based surveillance system, designed to identify infants at high risk for health problems and to measure progress toward goals in improving the health of mothers and infants.

- The Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care (mPINC) survey (conducted biannually) assesses maternity care practices across the United States and provides hospitals with feedback to improve breastfeeding support.

- The Infant Feeding Practices Study I, II, and III are currently underway, as is the 6-Year Infant Feeding Practices Follow-up Study (CDC, 2024).

- The Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report covers breastfeeding, donor human milk, and other related topics.

In addition, WIC measures breastfeeding rates of enrolled participants, primarily using administrative data collected from participants (e.g., Whaley et al., 2012).

Breastfeeding Data Collection Systems

The committee focused on four primary data collection systems and instruments for this report: CDC’s NIS-Child, NVSS, mPINC, and PRAMS.

The NIS-Child is an annual, randomly administered survey of parents and caregivers of children between ages 19 and 35 months (CDC, n.d.). Since 2006, the survey has asked questions that provide insight into breastfeeding initiation, duration, and exclusivity rates at the national level (CDC, 2025):

- Was [child] ever breastfed or fed breast milk?

- How old was [child’s name] when [child’s name] completely stopped breastfeeding or being fed breast milk?

- How old was [child’s name] when [he/she] was first fed formula?

- This next question is about the first thing that [child] was given other than breast milk or formula. Please include juice, cow’s milk, sugar water, baby food, or anything else that [child] may have been given, even water. How old was [child’s name] when [he/she] was first fed anything other than breast milk or formula?

In addition to the NIS-Child, county-level data on breastfeeding at hospital discharge are available through birth certificate records maintained by the NVSS. These birth certificate data allow for localized analyses of breastfeeding behaviors and trends but are limited to initiation rates and do not capture duration or exclusivity (CDC, n.d.). Differences between the data sources reflect their distinct methodologies: while the NIS-Child provides a robust national snapshot of breastfeeding practices, birth certificate data offer granular geographic insights but lack longitudinal depth (CDC, n.d.; Chapman et al., 2008; Chapman & Pérez-Escamilla, 2009).

The mPINC survey evaluates hospital policies and practices that impact breastfeeding outcomes. Administered biennially by CDC, the survey tracks institutional factors such as skin-to-skin contact, rooming in, and formula supplementation practices in hospitals. These factors influence breastfeeding initiation and exclusivity rates. For example, hospitals that adhere to Baby-Friendly guidelines, which emphasize evidence-based maternity care practices, consistently report higher breastfeeding rates (CDC, 2022a).

Finally, the PRAMS can be used to provide data on vulnerable infants and mothers and “every” breastfed infant and “any” breastfeeding at age 8 weeks (CDC, n.d.).

Together, these data collection systems—NIS-Child, NVSS, mPINC, and PRAMS—provide complementary perspectives on breastfeeding practices, enabling policymakers to identify trends, variances, and areas for intervention.

CDC’s (2022b) Breastfeeding Report Cards provide a federal surveillance resource describing breastfeeding rates and supports in all states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico, as well as supportive policies and programs. The report cards typically include breastfeeding initiation rates (the percentage of infants who start breastfeeding), duration rates (how long infants are breastfed, both exclusively and/or with the introduction of complementary foods after six months), and support indicators (i.e., mPINC total score, percentage of live births occurring at Baby-Friendly facilities, state enactment of paid family and medical leave legislation, number of weeks of paid family and medical leave available for the care of a new child, and early care and education licensing breastfeeding support scores; CDC, 2022b). The Breastfeeding Report Card has historically been released every two years; however, a report card was not published in 2024. These report cards are an important example of a promising approach to communicating changes in breastfeeding rates and supports over time.

Future Public Health Surveillance Needs

Comprehensive and accurate public health surveillance of breastfeeding indicators is essential to guide policymaking and ensure the appropriate allocation of federal, state, tribal, and local resources. This report highlights multiple data collection programs and best practices, such as CDC’s Breastfeeding Report Cards and their periodic updates. The collection and analysis of this data over time helps identify trends, address differences, and improve and understanding the impact of breastfeeding resources and support.

However, some surveillance efforts and important data points are outdated. For example, CDC last collected breastfeeding initiation rates in 2018–2019. Continued research and disaggregated data analysis can serve

as the foundation for developing targeted strategies to reduce breastfeeding variances and improve maternal and infant health outcomes for all populations.

To this end, additional data collection to capture the wide variety of public health supports for breastfeeding would be useful for identifying gaps and opportunities. For example, it is important that surveillance systems not only capture rates of breastfeeding initiation, duration, and exclusivity, but also help decision-makers at various levels identify barriers to breastfeeding among populations with low rates, particularly those who are historically underserved. Additional attention to real-time changes in rates among communities with suboptimal breastfeeding rates and agility to address challenges as they arise would help reduce differences in current rates. Existing strategies or promising programs could be adjusted or scaled up to ensure that all mothers and infants receive the support they need to reach their breastfeeding goals.

Conclusion 4-2: Current public health surveillance of breastfeeding indicators provide complementary perspectives on breastfeeding practices, enabling policymakers to identify trends, variances, and areas for intervention. These data collection and analytical efforts identify significant trends, address variances across populations, and improve understanding the impact of breastfeeding resources and support. However, current efforts do not adequately capture the wide variety of public health supports for breastfeeding, disaggregated across different demographic groups, that could help identify facilitators and barriers to breastfeeding. Real-time monitoring of breastfeeding trends is also limited; additional attention to real-time changes in breastfeeding rates could help inform the allocation of public health resources and services to communities with the greatest need and further understanding of the effectiveness of existing interventions.

Recommendation 4-2: The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention should continue to coordinate the surveillance of breastfeeding outcomes and expand the current data collection systems to ensure continuity, coordination, and collaboration across federal, state, tribal, territory, and local programs.

Expanding the scope of public health data collection would help identify gaps and opportunities for improving breastfeeding support and continue to build evidence about outcomes related to breastfeeding investments. While numerous public health initiatives exist to promote breastfeeding, challenges regarding lack of coordination, limited resources, and insufficient

surveillance remain. Specifically, additional data collection and monitoring are needed to better capture:

- Potential barriers to breastfeeding across systems and settings

- Variances across all sociodemographic groups in breastfeeding and related health outcomes

- The availability of breastfeeding support, including access to lactation support providers (e.g., IBCLCs and community breastfeeding peer counselors; see also Chapter 6), and paid family and medical leave, as well as workplace and school accommodations (see Chapter 8).

- The impact of further scaling up health care initiatives (see Chapter 6), as well as public health programs and WIC breastfeeding peer counselors and other community-based breastfeeding support efforts (discussed further in this chapter).

Integrating existing federal data collection tools and improving data-sharing across agencies would provide a more comprehensive and timely understanding of breastfeeding trends in response to policy and programmatic changes. In addition, more community-level data are needed to identify local variances that may be masked by national or state-level statistics (Marks et al., 2023). For example, increased funding for assessing breastfeeding support in historically and currently underserved communities would allow community-based organizations and local public health departments to evaluate the effectiveness of their programs and share key insights (Keitt et al., 2018). This would enable scaling successful models to other communities and informing future public health interventions.

Most current breastfeeding data are captured retrospectively through surveys, which may limit responsiveness to real-time challenges (Chapman & Pérez-Escamilla, 2009). The committee identified innovative data collection methods that could improve surveillance: (a) mobile health applications for tracking breastfeeding behaviors; (b) standardized, discrete documentation of infant feeding in electronic health records to track outcomes at the health care level; (c) qualitative data collection to capture deep understanding of community needs and diverse lived experiences; and (d) longitudinal studies that quantify the impact of breastfeeding on long-term measures of maternal and child health and associated noncommunicable diseases. Ultimately, improving breastfeeding surveillance is an important element of advancing national breastfeeding initiatives (Chapman & Pérez-Escamilla, 2009). By expanding the scope of data collection, strengthening current systems, and enhancing community-level data-gathering, public health agencies can improve breastfeeding support

services, address variances, and strengthen the current landscape of support for breastfeeding mothers and families.

THE WIC PROGRAM

The beginning of this chapter identified government supports for breastfeeding across multiple entities and describes the public health surveillance of breastfeeding rates. Of the various government approaches, WIC, which is federally funded and state administered, is widely recognized as a highly successful public health nutrition program, serving nearly half of all infants born in the United States (Kessler et al., 2023). Given the broad reach of the WIC program to both mothers and infants, this chapter spends considerable time outlining how WIC promotes breastfeeding as the optimal source of nutrition for infants. (WIC provides iron-fortified infant formula for babies who are not fully breastfed).

WIC was established by USDA in 1972 (see Chapter 3). Today, WIC provides supplemental foods (known as food packages), nutrition education, breastfeeding support, and health care referrals for income-eligible pregnant, breastfeeding, and nonbreastfeeding postpartum women, and to infants and children up to age five years who are found to be at nutritional risk. Assessment of program eligibility, including an assessment of nutritional risk, is required at enrollment into the program and annually thereafter. Individuals with incomes below 185% of the federal poverty level are eligible for WIC, and adjunctive (i.e., automatic) eligibility is conferred through participation in Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and/or the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program (adjunctive eligibility may vary by state; USDA, 2024e). The assessment of nutrition risk enables staff to tailor food packages to address nutritional needs, design appropriate nutrition education and breastfeeding support, and connect to appropriate referrals. Currently, WIC serves over 6.7 million participants monthly and reaches over half of eligible individuals (Kessler et al., 2023; USDA, n.d.c). The highest level of WIC participation is among infants under age 12 months (78% of those eligible); the lowest level of participation is among four-year-olds (24.7% of those eligible) and postpartum women who are not breastfeeding (25.4%; Kessler et al., 2023).

WIC services have evolved over the past five decades (see Box 4-2). For example, the original program offered just two food packages, one for infants from birth to 12 months and one for children ages 1–3 years and pregnant and breastfeeding women. It now offers seven food packages designed to meet the nutritional needs of each participant. Similarly, breastfeeding promotion and support were not offered when WIC was founded. At the time, U.S. breastfeeding rates were at an all-time low of 25% (see Chapter 3). Low levels of breastfeeding, combined with very limited

BOX 4-2

The Evolution of WIC Breastfeeding Services

Beginning in 1989, the Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act required that the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA, 2024a) establish a national breastfeeding promotion program and foster wider public acceptance of breastfeeding in the United States. U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA’s) Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) state agencies were required to spend funds earmarked specifically for breastfeeding promotion and support and were authorized to spend WIC administrative funds on breastfeeding aids (e.g., breast pumps) that directly support breastfeeding initiation and duration.

In 1992, an enhanced WIC food package was established for women who exclusively breastfeed their infants to encourage breastfeeding among WIC mothers (Federal Register, 1992, pp. 56, 231–256).

In 1997, USDA kicked off a National Breastfeeding Promotion Campaign to encourage WIC participants to begin and continue breastfeeding.

In 2007, an interim rule revised regulations governing the WIC food packages and aimed to promote breastfeeding by establishing three feeding options within each of the infant food packages (fully breastfeeding, partially breastfeeding, fully formula feeding) by reducing the amount of formula provided to partially breastfed infants and increasing the amounts of foods provided to fully breastfeeding mothers. All states were required to implement this rule in 2009.

Separate from WIC funding, in 2004, Congress passed legislation that set aside funds exclusively for breastfeeding peer counseling (BFPC) support in the WIC program. The annual WIC BFPC set-aside has grown from $20 million initially to $90 million in fiscal year 2024, the highest level authorized by the 2010 Healthy, Hunger Free Kids Act.

information and resources, led WIC leaders to create a nutrition program designed to meet the high need for access to commercial milk formula, as will be discussed further in this chapter.

With respect to breastfeeding, WIC’s goal is to encourage mothers to breastfeed exclusively without supplementation and to ensure that every dyad receives the support it needs for healthy growth and development (USDA, 2016). As a public health nutrition program, WIC must ensure that every baby has access to nutrition support. Thus, in addition to providing breastfeeding support and enhanced benefits to breastfeeding women, WIC provides commercial milk formula to dyads who need it. The following three sections outline the three main components of infant feeding support in the WIC program relevant to this report: (a) WIC breastfeeding education and support, including the provision of breastfeeding supplies and peer counseling; (b) the WIC food packages for breastfeeding and nonbreastfeeding individuals; and (c) the provision of commercial milk formula through WIC.

WIC Breastfeeding Education and Support

Breastfeeding education for WIC participants starts during the prenatal period, often at the time of enrollment into WIC, with a focus on breastfeeding basics, the benefits of breastfeeding, barriers to breastfeeding, intention to breastfeed, and what to expect at the hospital. In 2022, of women enrolled in WIC prenatally, almost half (48.3%) enrolled in the first trimester, 40.2% in the second trimester, and 11.4% in the third (USDA, 2024f). While early prenatal enrollment is most common, some women enroll during the postpartum period, thereby missing an important window for prenatal breastfeeding education and support.

In support of breastfeeding, WIC regulations require state agencies to track breastfeeding rates every two years and to dedicate funding toward breastfeeding education and support. A thorough breastfeeding assessment is a requirement of providing WIC nutrition services and issuing a food package to postpartum mothers and their infants. In addition to assessing beliefs or knowledge about breastfeeding, potential complications, and the mother’s network for successful breastfeeding, the breastfeeding assessment identifies prenatal decision-making; growth, feeding, or other concerns expressed or identified by staff, the participant, or a provider; food package assignment and changes; breastfeeding aids, including breast pump issuance; and the return to work or school.

Breastfeeding education and support, which are core pillars of WIC service delivery, may come through any or all the following four channels: (a) program-wide staff breastfeeding training and education, (b) the provision of breastfeeding aids and accessories such as breast pumps, (c) case-management support from breastfeeding peer counselors, and/or

TABLE 4-1 WIC Breastfeeding Curriculum

| Level | Who Is Trained | Training Content |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | All WIC staff serving participants | Basic breastfeeding promotion; importance of breastfeeding. |

| 2 | Peer counselors and other WIC staff who support new mothers with breastfeeding | Supporting normal breastfeeding, common experiences of a breastfeeding parent, what support most parents need to breastfeed. |

| 3 | WIC competent professional authorities and breastfeeding coordinators | Assisting mothers with breastfeeding concerns, clinic practices that support breastfeeding. |

| 4 | WIC designated breastfeeding experts | Helping mothers with complex breastfeeding challenges that are beyond the scope of practice for Level 2 and 3 staff. |

NOTE: WIC = Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

SOURCE: Committee generated, based on USDA, 2025.

(d) support for women experiencing breastfeeding challenges. These services are provided by state and local agency WIC programs, and all WIC staff who counsel participants are required to receive breastfeeding training and education on an annual basis. However, there is considerable variation from state to state—and within states—in how this breastfeeding education and support is provided based on resource availability.

Staff Breastfeeding Training and Education

The Code of Federal Regulations for WIC (2024) establishes standards for breastfeeding promotion and support that include, at a minimum, the following: (a) a policy that creates a positive clinic environment that endorses breastfeeding as the preferred method of infant feeding, (b) a requirement that each local agency designate a staff person to coordinate breastfeeding promotion and support activities, (c) a requirement that each local agency incorporate task-appropriate breastfeeding promotion and support training into orientation programs for new staff involved in direct contact with WIC clients, and (d) a plan to ensure that women have access to breastfeeding promotion and support activities during the prenatal and postpartum periods. The WIC Breastfeeding Curriculum (USDA, n.d.a)—developed by USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service (FNS), which administers WIC—was established for state and local agency staff training and is updated regularly. FNS strongly encourages, but does not require, state and local WIC agencies to use all levels of this curriculum (see Table 4-1). While all staff are encouraged to receive Level 1 training around promotion and support of breastfeeding, fewer staff complete the higher Level 3 and 4 trainings that focus on breastfeeding concerns and problems.

Evidence from the WIC Breastfeeding Policy Inventory (BPI) II (USDA, 2024b), using information from state plans in 2022, found that all state agencies used the FNS curriculum to train state and local agency staff (Esposito et al., 2024). Of the 1,527 local agencies that responded to the WIC BPI II Local Agency Survey (250 did not respond), 77.8% reported using the FNS curriculum to provide breastfeeding training and education to at least one type of staff. It was used most often to train breastfeeding coordinators (62.5%) and competent professional authorities (56.8%) and least often with clerical or support staff (44.5%). Local agencies reported they commonly used other FNS resources, such as the WIC breastfeeding website (63.9%), or other breastfeeding resources (62%) to train staff (Esposito et al., 2024). As is evident from these data, how state and local agencies implement breastfeeding training and education varies.

Notably, the COVID-19 pandemic increased the need for virtual breastfeeding support, which provides an opportunity to reach participants without requiring travel to a WIC site or other health care facility. While many

WIC local agencies (62.4%) offered telephone counseling prior to the pandemic, this number increased to 83.2% by late 2022. At the same time, only about half (50.3%) of local agencies reported their staff had access to training on how to provide breastfeeding counseling in a virtual setting (Esposito et al., 2024).

Breastfeeding Aids and Accessories

WIC programs may provide breast pumps and other breastfeeding supplies to the breastfeeding dyad, but Medicaid and/or private health insurance is the first payer on record (see Chapter 7). Availability and provision of breastfeeding supplies from WIC varies widely from agency to agency, largely because breastfeeding aids and accessories are not WIC program benefits (USDA, 2016). State agencies must provide WIC participants with supplemental foods; nutrition education, including breastfeeding education and support; and referrals to health and social service programs. Additionally, program regulations specify that “the cost of breastfeeding aids which directly support the initiation and continuation of breastfeeding” are allowable costs (7 C.F.R. § 246.14(c)(10), 2024). Thus, state agencies may choose to provide breast pumps and other aids and accessories and can offer them for free, at a reduced cost, or at cost to WIC participants. According to the WIC BPI II, 78.2% of states have manual breast pumps, 62.1% have single-user electric breast pumps, 58.6% have multiuser electric breast pumps, and 23% have an unspecified type of electric pump available to participants (Gleason et al., 2024). Eight percent (8%) of state agencies do not specify availability of any breast pumps (Gleason et al., 2024).

The primary avenue for states to provide breast pumps and supplies is through annual funding allocations from USDA to states, which are provided quarterly in the form of food grants (~70% of funding) and Nutrition Services and Administration (NSA) grants (~30% of funding). Each state receives a specified amount for food spending and NSA spending, determined by USDA’s funding formula. In FY 2024, the total national WIC food grant allocated was about $5.6 billion; the total national NSA grant was about $2.37 billion (USDA, 2024g). States are authorized to use NSA funds (since 1989) and/or food funds (since 1998) to purchase or rent breast pumps and supplies. Therefore, WIC state agencies have the authority to decide how to spend WIC funds on breastfeeding aids and accessories; their decision is often based on available funding once NSA and food funds are allocated to meet all other food and nutrition needs. State agencies that choose to purchase breastfeeding aids and accessories must develop specific policies that ensure the most efficient use of WIC funding. Thus, provision of and availability of breast pumps and supplies for WIC caregivers can vary considerably from state to state, as well as within states.

Breast pumps can be offered to breastfeeding women based on how a state determines need and may not be offered solely to encourage breastfeeding. In general, breast pumps may be provided to mothers having difficulty establishing or maintaining milk supply because of maternal or infant illness, during mother–infant separation (e.g., infant in neonatal intensive care unit, mother returning to work), and to mothers having temporary breastfeeding problems. State agencies must determine the circumstances under which pumps will be provided and must determine the type(s) of pumps to be offered. USDA’s Breastfeeding Policy and Guidance document provides detail to WIC agencies for implementing breast pump programs (see USDA, 2016, Appendix E).

WIC Breastfeeding Peer Counselor Program

Distinct from USDA WIC funding for food and NSA costs, the BFPC is funded through a separate set-aside from Congress and provides an evidence-based model of breastfeeding support that connects pregnant and postpartum WIC participants with peers from their community. The amount for BFPC funding was $90 million for FY 2024 and, like WIC funding, must be allocated by Congress every fiscal year.

Substantial evidence demonstrates that peer counselors improve rates of breastfeeding initiation, duration, and exclusivity (see, e.g., Chapman et al., 2010; Interrante et al., 2024; see also Chapter 3). FNS defines a WIC breastfeeding peer counselor as a paraprofessional from the community WIC serves who has previous experience with breastfeeding. Peer counselors are recruited and hired from WIC’s target population of low-income women, and the BFPC program trains them to provide breastfeeding support in WIC clinics, homes, and/or other settings (USDA, n.d.b). FNS’s goal is “to integrate breastfeeding peer counseling as a core WIC service and assure that breastfeeding peer counselors are available in as many WIC clinics as possible”

TABLE 4-2 Current Schedule of Minimum Required Contacts from Breastfeeding Peer Counselors

| Time Period | Minimum Required Contacts |

|---|---|

| Prenatally | Monthly, then weekly two weeks prior to expected delivery date |

| 1st week postpartum | Every 2–3 days, and within 24 hours if problems reported |

| 1st month postpartum | Weekly |

| 1–6 months postpartum | Monthly, as long as things are going well, and 1–2 weeks before return to work, and 1–2 days after return to work |

SOURCE: Committee generated. USDA, 2016.

(USDA, 2016, p. 19). The current funding level is not sufficient to ensure every breastfeeding dyad has access to a WIC breastfeeding peer counselor.

WIC peer counselors have a defined scope of practice that is limited to basic breastfeeding support and education. States must have a written defined scope of practice for peer counselors that (a) describes the peer counselor’s role as providing basic breastfeeding education and support and (b) lists breastfeeding conditions and concerns that are outside the scope of practice and should be referred to a designated breastfeeding expert. Training of state and local peer counseling management and clinic staff uses the FNS-developed training curricula, and state agency nutrition education plans must establish the set of standardized breastfeeding peer counseling policies and procedures for the state and local levels. WIC agencies must conduct an annual assessment of the breastfeeding needs of the target population, have a protocol that describes how peer counselors address concerns and needs outside of clinic hours, have opportunities for peer counselors to observe experienced lactation experts and peer counselors, as well as monitor and observe peer counselors. Agencies must have a process in place for WIC staff to refer WIC participants to peer counselors as part of the usual WIC certification, assessment, and nutrition education process. Agencies with a peer counseling program must have at least 0.25 full-time equivalents (FTEs) dedicated to a supervisor for every 3–5 peer counselors. Peer counselors are expected to adhere to a general schedule of contacts with the mother, from the prenatal period through six months postpartum, but total doses of peer counseling support a caregiver receives can vary from agency to agency and from caregiver to caregiver (Table 4-2).

Based on survey data collected in 2022, 71.4% of local agencies had a peer counseling program (Wroblewska et al., 2024). This does not, however, mean that 71.4% of WIC mothers have access to a peer counselor. As reported by Wroblewska et al. (2024), the average ratio of breastfeeding women to peer counselor FTE varied substantially between small local agencies serving fewer than 1,000 participants (69:1), medium local agencies serving 1,000–4,999 participants (187:1), and large local agencies serving more than 5,000 participants (393:1). One peer counselor FTE cannot serve 187 or 393 participants; these ratios indicate that there is a substantial unmet need. When asked about the number needed to serve all breastfeeding clients who want to receive peer counseling support, local agency staff reported an average ratio of 88:1 would be required (USDA, 2024c).

Support for Mothers with Breastfeeding Challenges

As noted above, WIC peer counselors have a defined scope of practice that is limited to focusing on supporting breastfeeding without need for formula supplementation. For mothers experiencing challenges with

breastfeeding, support is needed from staff with additional training, which may include an IBCLC or other lactation support provider. The Level 3 and 4 trainings available in the WIC Breastfeeding Curriculum support the training of breastfeeding experts to provide additional hands-on support (USDA, n.d.a). However, as mentioned above, fewer staff complete the higher Level 3 and 4 trainings, which focus on breastfeeding concerns and problems. As of this writing, local WIC agencies continue to work toward an FNS goal that every WIC local agency has designated breastfeeding experts on staff.

Breastfeeding Counseling in Tribal Communities

Tribal organizations manage WIC programs on tribal lands. While these programs are funded by federal WIC dollars, tribes often contribute significant additional resources of their own in the form of office and clinic space, and some cover additional costs such as salaries for breastfeeding coordinators (Henchy et al., 2000). Evidence suggests that breastfeeding counseling programs improve breastfeeding outcomes among Native American women (Long et al., 1995; Wright et al., 1997). Unfortunately, participation in tribally administered WIC programs has declined more than the national average. Estradé et al. (2023) conducted a study to document barriers for WIC participation in two tribal communities. They found three interconnected barriers: (a) reservation and food store infrastructure, (b) WIC staff interactions, and (c) integration between the community and state-level administration and bureaucracy. Their findings also emphasized the need to use systems approaches to understand how to improve access to and quality of WIC breastfeeding education using an information technology–facilitated approach to breastfeeding support (Estradé et al., 2023; see also Martinez-Brockman et al., 2025). See Box 4-3 for other promising approaches to WIC breastfeeding support.

In summary, breastfeeding education and support are important components of WIC program services, supporting staff through required breastfeeding training and education and impacting participants through support, education, aids, and accessories. Funded separately, the evidence-based WIC breastfeeding peer counseling program successfully supports many WIC participants in achieving their breastfeeding goals, but funding is not currently adequate such that every mother has access to peer counseling support. Though breastfeeding education and support are mandated in the WIC federal guidelines and available across the United States, the level of support available to mothers can vary substantially. Core breastfeeding education and support are required, but access to breastfeeding aids, accessories, and peer counselors depends on funding decisions at the national, state, and local levels.

BOX 4-3

Other Promising Approaches to WIC Breastfeeding Support

Regional Breastfeeding Liaisons (RBLs): The California Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program adopted a model that directs a portion of its funds to support local WIC agencies that would like to hire/promote an RBL. The role of the RBL is to strengthen coordination of breastfeeding services for WIC participants in the region. RBL activities are based upon required statewide goal areas and regional goals. Promoting the use of consistent evidence-based breastfeeding messages in the community and coordinating and delivering breastfeeding training for health care providers, staff, and community groups, as appropriate, is part of the individual RBL’s annual action plan goals. RBLs facilitate seamless breastfeeding support by collaborating with health care providers, hospitals, employers, and the community. RBLs are located regionally throughout the state and work in four goal areas (California Department of Public Health, 2021):

- Lactation accommodation: RBLs support and assist employers and community organizations in providing lactation accommodation and breastfeeding support to WIC participants.

- Community-building: RBLs coordinate with community programs and coalitions to develop consistent breastfeeding messages, access to appropriate breastfeeding support services in the community, and continuity of care.

- Hospitals: RBLs coordinate breastfeeding services between WIC and hospitals that serve WIC participants. Additionally, RBLs help hospitals attain Baby-Friendly status.

- Health care providers: RBLs facilitate progress towards breastfeeding-friendly clinic practices for health care providers, community clinics, and public health programs.

Baby Behavior: Education for WIC Staff and Participants

When parents understand their infants’ cues, they can meet their needs appropriately, resulting in an increase in exclusive breastfeeding and a decrease in formula feeding and overfeeding. Dr. Jane Heinig from the University of California, Davis Human Lactation Center, in partnership with the California WIC Program, documented that a primary reason new parents reported that they stopped breastfeeding was their perception of insufficient milk supply due to a crying infant (Heinig et al., 2009). The Baby Behavior education modules were developed to teach parents about typical baby behavior and include written materials and videos for staff and participants (e.g., the Getting to Know Your Baby: Birth to 6 Months brochure [California WIC Program, 2018]). These modules are now embedded in all staff and participant education materials throughout California WIC and at least six other state WIC programs (Arizona, [WIC Arizona, n.d.], Connecticut [Connecticut WIC Program, 2015], Minnesota [Minnesota Department of Health, 2023], Nebraska [Family Health Services, Inc., 2024], Nevada [Nevada WIC, n.d.], and Washington [Washington State Department of Health, 2013]).

The WIC Food Package

Intersections with Breastfeeding

As mentioned, WIC regulations require the provision of food packages designed to meet the unique supplemental nutritional needs of each program participant. These regulations stipulate the minimum requirements for all food packages that states must adhere to, but there can be state-level variations in the specific products available (e.g., brands) or product form (e.g., canned, frozen, and/or fresh fruits and vegetables). The food packages for breastfeeding mothers are designed to provide incentives for breastfeeding initiation by offering additional foods to meet the higher caloric needs of the breastfeeding mother and to support continuation of breastfeeding by providing food benefits to breastfeeding mothers for 12 months rather than six months postpartum. Breastfeeding mothers whose infant receives commercial milk formula from WIC are to be supported to breastfeed to the maximum extent possible through staff support and by tailoring formula amounts to meet but not exceed the infant’s nutritional needs (e.g., issue 1–2 cans vs. 7–9 cans of formula, based on the amount of breastfeeding). Since the program’s inception, breastfeeding women have received food benefits for themselves (12 months) for longer than women who were not breastfeeding (0–6 months; National School Lunch and Child Nutrition Act Amendments, 1975).

To ensure maximum support of the newborn dyad, it is required that each caregiver receive a complete breastfeeding assessment (described above). This enables WIC staff to assign the appropriate food packages to the breastfeeding dyad. WIC regulations define three infant feeding variations with accompanying food packages for caregivers and infants, one of which is issued to the dyad based on the breastfeeding assessment: Fully breastfeeding (the infant does not receive any formula from WIC; mother receives the maximum amount of food to support her nutrient needs while breastfeeding), partially (mostly) breastfeeding (the infant is breastfed and receives some formula from WIC; mother receives less food than the fully breastfeeding mother and more food than the fully formula feeding mother), or fully formula feeding (infant receives the maximum amount of formula, mother receives less food than breastfeeding mothers). If feeding decisions change as the infant ages, the food package assignment can be changed. Training for all staff enrolling newborns in WIC is key to ensuring that participants are issued appropriate food packages and receive adequate breastfeeding support and counseling.

Key Changes to the WIC Food Package

Since WIC was created, its food packages have been reviewed twice to align with nutrition science. The first scientific review of the WIC food

packages by the National Academies was released in 2006 (Institute of Medicine, 2006); it provided recommendations that led USDA to make the first substantial changes to the WIC food package since the program’s inception. By October 2009, all states had implemented the changes, which included the addition of fruits and vegetables in the form of a cash-value benefit (at that time, $6/month for children and $8/month for women), whole grains were added, and juice and full-fat dairy were reduced. The 2009 food package change also required states to implement only two food package choices in the first month postpartum—fully breastfed and fully formula fed—to reduce the chance of formula interfering with the mother’s milk production so that breastfeeding could be firmly established. State agencies have the option, however, to make available a third package in the first month that contains not more than one can of powder infant formula (containing up to 104 reconstituted fluid ounces) on a case-by-case basis. The goal is to provide the minimal amount of supplemental formula needed, while offering counseling and support to breastfeeding mothers.

Studies of the impact of having only two packages available in the birth month have been mixed. The largest study evaluating the impact of this rule on breastfeeding outcomes across multiple states was funded by USDA FNS and found that while issuance of the fully breastfeeding food package increased in the birth month, so did issuance of the full formula package (Abt Associates, 2011). No change in initiation or intensity of breastfeeding was observed, and a small increase in duration was noted. Thus, while no adverse impacts on breastfeeding were observed, withholding formula in the birth month did not have the intended impact of jumpstarting exclusive breastfeeding. Withholding formula in the first month was associated with many women taking the full formula offered (their only option if they felt they needed some formula), even if they were doing some breastfeeding. As documented in other studies, this may largely be because breastfeeding requires intensive education and support, with particularly intensive focus in the weeks immediately before and after delivery.

Another study examined the impact of the breastfeeding changes in the birth month in one state (Whaley et al., 2012). California embarked on an intensive WIC staff and participant breastfeeding education campaign starting six months prior to the 2009 food package change and implementation of the birth month rule. Breastfeeding rates increased substantially following implementation of the birth month rule, while issuance of the full formula package did not increase. Thus, when pregnant participants were well educated about the benefits of initiating breastfeeding, were aware that breastfeeding support would be available from WIC throughout the perinatal period, and knew that the options for accessing formula from

WIC in the month following the infant’s birth would be very limited, they exhibited higher rates of breastfeeding initiation and duration (Whaley et al., 2012).

Together, these studies highlight the importance of pairing policy change with intensive education and support to increase rates of initiation and duration of breastfeeding. Abt Associates (2011) also recommended further increases to the economic value of the full and partial breastfeeding packages relative to the full formula package.

In 2014, the National Academies convened a second scientific committee to examine the WIC food packages and make recommendations to ensure alignment of the WIC food packages with advances in dietary science. Recommendations from the committee’s 2017 report included further changes to the WIC food package to optimize balance and choice of foods for the WIC participant (National Academies, 2017). The recommendations, which were required to be cost neutral, sought to achieve better alignment in the provision of WIC supplemental foods. In light of the studies related to formula issuance and breastfeeding support, the committee also recommended further increasing the economic value of the full and partial breastfeeding packages relative to the full formula package. Recommendations included fruit and vegetable benefits for fully breastfeeding mothers at $35/month for 12 months, for partially breastfeeding mothers at $25/month for 12 months, and for fully formula feeding mothers at $15/month for six months. The committee also recommended expanding the options available to families in the birth month, such that formula amounts could be calibrated to meet mothers’ needs starting in the birth month (National Academies, 2017).

USDA included almost all the National Academies’ recommendations in the final WIC food package rule, released in April 2024. States are required to implement all changes by April 2026. In the period between 2017 and 2024, the American Rescue Plan Act enabled USDA to increase the cash value benefit for fruits and vegetables for all WIC participants, releasing the cost-neutral requirement that constrained the 2017 recommendations. Amounts for fruits and vegetables increased to $52/month for fully and partially breastfeeding women, through 12 months postpartum. Women receiving the full formula package receive $47/month for fruits and vegetables, through six months postpartum. Thus, while the amounts received by women receiving the breastfeeding packages differ from the amount received by women who are fully formula feeding, the magnitude of difference ($52 vs. $47 rather than $35 vs. $15) is a substantial departure from the 2017 recommendations and does not set up a notably strong immediate incentive within the food benefits received by breastfeeding versus nonbreastfeeding women in the first six months postpartum.

In summary, the WIC food packages, which include only specific healthy foods known to be deficient in the average diets of American women and young children, are an important component of the WIC program. Given the greater energy needs to support successful breastfeeding, the food package for breastfeeding women provides more food, for a longer duration, than the food package for postpartum nonbreastfeeding women. While the food package for breastfeeding women may help support a woman’s decision to initiate and maintain breastfeeding, and food package policy reflects an effort to support breastfeeding through larger benefits for the breastfeeding dyad, it is clear from the literature that food alone is not sufficient to support breastfeeding. The provision of healthy food paired with intensive education and support for breastfeeding provides optimal support for women to achieve their breastfeeding goals.

Commercial Milk Formula and WIC

WIC provides iron-fortified commercial milk formula (i.e., infant formula) for babies who are not fully breastfed at no cost to families. In June 2024, 857,174 infants ages 0–12 months received the fully formula feeding package; 390,012 infants received the partially breastfeeding package; and 239,897 infants received the fully breastfeeding package (USDA, 2024d). This means that 58% of infants currently receive the full amount of formula available from WIC, 26% receive some formula, and 16% receive no formula. About half of the commercial milk formula purchased each year in the United States is provided to WIC participants.

The provision of commercial milk formula in WIC has been a controversial topic, particularly as it relates to breastfeeding. On one hand, making formula available through WIC is seen as conflicting with breastfeeding support; some studies have shown that breastfeeding rates of WIC participating families lag behind those of income-eligible nonparticipants, though the gap has been narrowing in recent years, particularly among non-Hispanic Asian and Pacific Islander and American Indian/Alaska Native mothers (Thoma et al., 2023). On the other hand, access to formula from WIC is seen as a lifeline, based on evidence that lack of access may force families to turn to unhealthy practices (e.g., diluting formula with extra water or cereal, preparing smaller bottles, saving leftover mixed bottles for later, substituting with homemade formulas) that could confer significant risk to the health and growth of the infant. Because of the severity of outcomes that can result from insufficient access to appropriate nutrition, particularly before complementary foods can begin to be introduced at six months of age, WIC infants who are not breastfed from birth through age five months receive the quantity of formula needed to meet 100% of their caloric needs. That said, the overreliance on commercial milk formula in the United States (as noted in Chapters 2, 4, and 6) is structural and systemic.

Commercial Milk Formula Recall of 2022 and Associations with WIC Breastfeeding

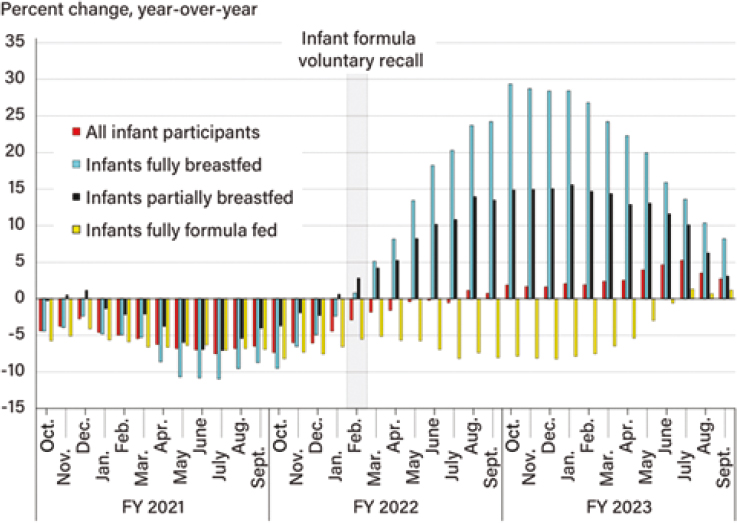

In 2022, several brands of commercial milk formula were recalled because of potential contamination with dangerous bacteria (see later section of this chapter). This resulted in major shortages with dire impacts on many families who depended on commercial milk formula, particularly those with sick babies requiring specialized formulas. The recall provided a window into the fragility of the commercial milk formula manufacturing system in the United States, as well as into infant feeding patterns when access to formula is limited. Notably, evidence suggests that the uncertainty around access to formula due to the recall was associated with increased breastfeeding among WIC participating infants. According to national monthly WIC participation data, in the month following the shortage (March 2022), the number of fully formula feeding infants decreased 5%, the number of partially breastfed infants increased 4%, and the number of fully breastfed infants increased 5%, compared with the same month in the previous year. By October 2022, the number of fully formula feeding infants decreased 8%, the number of partially breastfed infants increased 15%, and the number of fully breastfed infants increased 29% from one year before (Figure 4-1; Hodges et al., 2024).

Formula Contracts and Costs Associated with Formula and Breastfeeding Food Packages

WIC agencies have been required to use competitive bidding to procure commercial milk formula since 1989 (under the Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act) unless another cost-containment approach yielded equal or greater savings. This competitive bidding process was created in response to increasing commercial milk formula prices in the 1980s. Unlike other food assistance entitlement programs—such as SNAP and the National School Lunch Program, in which anyone who meets eligibility criteria can receive the food assistance—WIC is a discretionary program. This means funding is determined by Congress annually, and eligible individuals may not be served once annual funding appropriations are exhausted. Thus, as WIC program costs increased in the 1980s because of increases in the cost of commercial milk formula, fewer participants could be served by the program. As of this writing, no other cost-containment approach has been identified, so all states require commercial milk formula companies to bid on WIC contracts by offering rebates on the lowest national wholesale price for a standard amount of formula redeemed by WIC participants in that state. The WIC state agency then awards a single-supplier contract to the manufacturer offering the highest discount. The formula rebates effectively contribute to additional food funds that allow WIC to serve more participants.

NOTES: Fully breastfed infants are certified to receive WIC benefits but are not issued food benefits through the first five months because the infants are assumed to be breastfed exclusively. Partially breastfed infants receive some formula from WIC. FY = fiscal year; WIC = Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

SOURCE: Hodges et al. (2024).

Infant formula rebates in FY 2023 generated $1.58 billion in food funds, allowing WIC to serve around two million more participants annually (USDA, 2024d). A deeper analysis of WIC’s economic role in the formula market is outside the scope of the committee’s charge, which did not include examination of economic or market dynamics.

The 2024 National Academies report resulting from the commercial milk formula recall and shortage, titled Challenges in Supply, Market Competition, and Regulation of Infant Formula in the United States, outlined key implications for WIC-related formula contracts. The study committee concluded that “the infant formula brand issued by state WIC agencies has resulted in significant price discounts for WIC, in the form of rebates, enabling WIC to serve more participants” (National Academies, 2024, p. 7). The winning bidder also has marketing advantages in the non-WIC market

(e.g., shelf space, use by hospitals). The report also concluded that WIC’s competitive bidding process