Chemical Terrorism: Assessment of U.S. Strategies in the Era of Great Power Competition (2024)

Chapter: Summary

Summary

Chemical threat agents are highly hazardous or toxic chemicals that can be acquired or used as weapons by states or nonstate actors. The widespread availability of starting materials and instructional materials for producing chemical weapons of mass destruction (WMD) have reduced barriers to entry for the nefarious use of chemicals. Domestic and foreign violent extremist organizations (VEOs), or terrorist groups, have caused a greater amount of harm with chemical agents than with biological or radiological weapons.

The United States’ capacity and capability to identify, prevent, counter, and respond adequately to chemical threats is established by the strategies, policies, and laws enacted across multiple levels of government. Many U.S. counter-WMD terrorism policies, strategies, and programs were enacted in the wake of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the United States. Shortly after, the subsequent mailing of envelopes containing spores of B. anthracis also propelled a number of WMD-related counterterrorism and nonproliferation programs across different agencies. In addition, steady progress has been made over that same time in eliminating declared chemical weapons stockpiles under the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), which went into effect in 1997 and has more than 190 states/parties.

While the number of chemical terrorism incidents has risen and fallen over time, there is no empirical or analytical indication that the threat is disappearing, especially with several incidents within the past three decades of terrorists using or pursuing nerve agents or chemical agents. Factors that could potentially increase this threat include the large and growing number of chemicals that could be used in chemical weapons, perceived changes in the tactical and/or strategic benefits of using them compared to other types of weapons, emerging technologies, and a rise in foreign or domestic terrorism. It is in this context that the 2021 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) directed the Secretary of Defense to request that the National Academies of Sciences,

Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) conduct an independent review of the adequacy of U.S. strategies to prevent, counter, and respond to chemical terrorism.

STUDY TASK, SCOPE, AND METHOD

Given the breadth of the study’s task, the committee took a high-level view and focused on identifying the most important technical, policy, and resource gaps with respect to strategies for identifying, preventing, countering, and responding to chemical threats, and budgeting to address these needs. While acknowledging the potential rise of terrorist threats from state actors over the past decade, the report focuses on chemical threats originating from nonstate actors with or without state involvement (e.g., knowledge or the capability to share and other forms of support to enable chemical terrorism). The committee decided to combine preventing and countering in their strategy assessment. Considerations of long-term health and environmental effects were beyond the scope of the charge. To carry out its work, the committee systematically evaluated key strategic documents listed in chapter 3, that range from national-level to agency-level strategies.

In the United States, there has not been a chemical terrorist event that has had consequences approaching those observed outside of the country. Generally, U.S. response organizations have been effective in identifying and thwarting chemical threats, although, there have been a few notable cases where law enforcement did not identify a threat before an attack was executed. Additionally, the 2018 Skripal poisonings in the United Kingdom illustrate a new turning point in actors, intent, and methods in the chemical threat: from that of terrorist-initiated to use by a combination of a state actor, targeted assassination, and nontraditional agent.

COMPLEX CHEMICAL THREAT LANDSCAPE

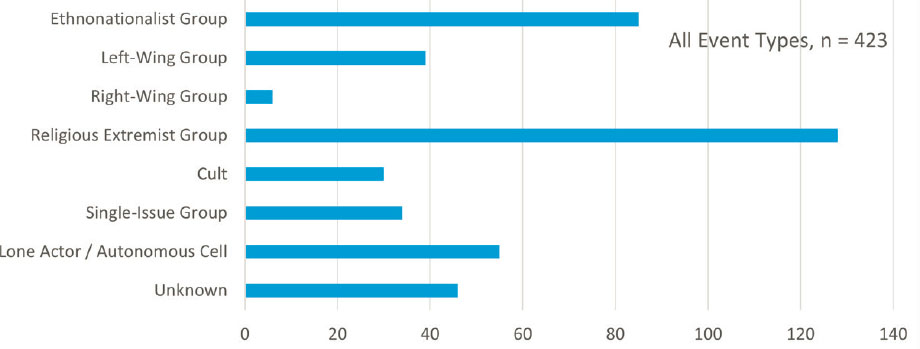

Incidents of chemical terrorism and attempted terrorism have involved one hundred different perpetrators motivated by different ideologies (see Figure S-1). For the period between 1990–2017, the geographic distribution of countries where chemical terrorism

SOURCE: Binder and Ackerman, 2020.

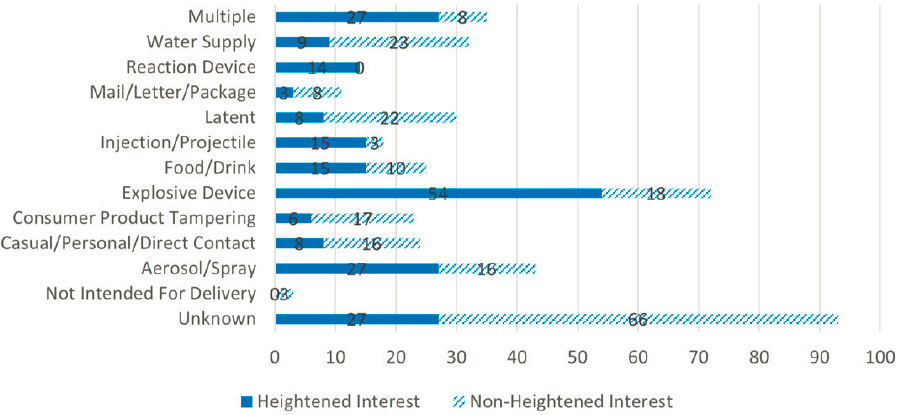

SOURCE: Binder and Ackerman, 2020.

incidents have occurred is extensive, with 47 countries involved over this period and actual uses of chemical agents as weapons occurring in 34 of these cases. They have also utilized an array of chemical agents encompassing many commonly available (often referred to as “low-end”) agents and several toxic industrial chemicals (TICs), as well as toxic industrial materials (TIMs). They have also used some chemical agents that have traditionally been developed in the military context (e.g., the nerve agent, sarin) and have included a variety of delivery methods, such as explosive devices, aerosol, and other methods (see Figure S-2).

ASSESSING STRATEGIES FOR IDENTIFYING CHEMICAL THREATS

The total number of chemicals that constitute or could constitute WMD terrorism threats is vast and continually expanding. Over two hundred million chemicals have been synthesized or isolated, and another is identified every 3–4 seconds (CAS, n.d.). Technological advances such as cheminformatics, artificial intelligence, machine learning, additive manufacturing, nanotechnology, and microscale chemical reactors further facilitate the discovery of new and novel chemical threat agents available for potential beneficial or nefarious use. Thus, it is impossible to identify and prevent or counter every threat.

Federal agencies that spoke with the committee acknowledged that, overall, terrorists seeking to perpetrate chemical attacks tend to opportunistically misuse traditional classes of chemicals, primarily TICs and TIMs. The majority of publicly reported domestic plots did not come to fruition between the 1970s and mid-2010s for several reasons. However, the occurrence or nonoccurrence of terror attacks involving chemicals is not a direct indication that the United States, in particular, the intelligence community (IC), was or was not successful in identifying a threat.

RECOMMENDATION 2-3: The intelligence community (IC) should continue to monitor interest in emerging technologies and delivery systems, such as drug

delivery systems, and trends by terrorist groups to innovate and improvise using chemical agents. This may look significantly different than the applications of advanced materials chemistry by great power states.

To assess the United States’ capability to identify chemical threats, the committee reviewed recent strategies. The committee considered that a successful strategy to identify chemical terrorism threats is one that focuses on robust information-sharing regarding the following:

- Chemicals that may be used in an attack—both known chemical weapon agents and lesser-known emerging agents;

- Threat actors who may use or pursue chemicals for use in weapons of mass destruction terrorism (WMDT) attacks; and

- Entities that may support or sponsor chemical attacks or terrorism.

This report concludes that the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), partner law enforcement, and IC have been effective in identifying and interdicting the majority of domestic terrorist attacks involving chemical materials, which have typically employed conventional TICS rather than traditional chemical warfare agents. While the FBI has been effective, approaches to identifying chemical threats could be strengthened by using a multi-lens approach from several different agencies that emphasizes augmented communication and coordination between local and state enforcement and the IC. In addition, this area would greatly benefit from increased coordination between the IC and technical experts—particularly those with specific knowledge of terrorist motivation and psychology. Finally, it is unclear if the tactical readiness to implement the reviewed strategies is occurring at the necessary pace to respond to an act of chemical terrorism.

RECOMMENDATION 4-3 (Abbreviated): Existing IC programs should actively seek and incorporate new approaches to identify existing chemical threats (traditional and improvised) and potential emerging threats by terrorist groups. In developing new approaches, program managers should develop strategies that look beyond the traditional terrorism suspects and that augment and leverage skill sets of the U.S. Government (USG) agencies. The threat assessments should be updated reflecting the current times and demographics.

RECOMMENDATION 4-4: The National Counter Terrorism Center (NCTC), Department of Defense (DoD), and Department of Homeland Security (DHS) should review current identification approaches to determine whether shifts in emphasis are required as a result of expanded and augmented VEOs and terrorist capability resulting from the potential migration of chemical agents, other materials, technology, and expertise from state actors to VEOs.

RECOMMENDATION 4-5: The USG should ensure that the identification of chemical terrorism threats is explicitly included in ongoing and future strategies. Chemical terrorism threats should be considered distinct from nuclear nonproliferation, identification of state-based offensive chemical programs, and traditional (non-nuclear-biological-chemical) terrorism.

STRATEGIES TO PREVENT AND COUNTER CHEMICAL WMD

“Prevent/counter” strategies focus on plans to prevent and counter specific adversaries from committing acts of chemical terrorism. The committee surveyed the strategy documents listed in chapter 5, all of which contained useful information related to aspects of preventing and countering chemical terrorism. A successful strategy to prevent or counter chemical terrorism focuses on the following elements:

- Incorporates developments in the “Identify” area into practice for “Prevent and Counter.”

- Dissuades terrorists through deterrence by denial, deterrence by punishment, or through normative means.

- Impedes acquisition of raw materials, production technology, delivery technology, or information for production or delivery. Strategy also demonstrates having mechanisms (e.g., insider threat programs, strategic trade controls, international efforts, collaboration with other counterterrorism programs) to ensure those items are not acquired.

- Interdicts active plots through military, law enforcement, or intelligence capabilities.

- Ensures collaboration at various levels—international, federal, state, local, tribal, and territorial.

- Addresses new chemical terrorism threats: new chemical agents, new production or delivery methods and technologies, new actors, forming collaboration with non-terrorist focused agencies, like the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA).

The report concludes that most of the prevent/counter strategy documents espoused a coherent action plan or set of strategy elements comprising a combination of a well-defined goal with a corresponding definition of success, as well as at least one policy, plan, and/or resource allocation designed to meet the goal.

Deterrence

Deterrence is an influence strategy that tries to dissuade the adversary from undertaking some action through the use of negative incentives. Deterrence most commonly refers to the use of conditional threats, where the costs threatened are intended to outweigh the benefits from the action being considered. The committee found multiple existing policies and programs that contribute to a strategy of deterrence by denial,

which involves denying attainment of benefits so that the actor is dissuaded from attempting the action in the first place. These include facility security improvements under the Chemical Facility Anti-Terrorism Standards (CFATS)1 program and a variety of response capabilities that would mitigate the harm caused by a chemical attack.

Upon reviewing existing strategy documents, the committee found references to deterrence by punishment in a nonspecific context. For example, the 2002 National Strategy to Combat Weapons of Mass Destruction (p.3) reiterates the declaratory policy that

the United States will continue to make clear that it reserves the right to respond with overwhelming force—including through resort to all of our options—to the use of WMD against the United States, our forces abroad, and friends and allies… posing the prospect of an overwhelming response to any use of such weapons.(Executive Office of the President, 2002)

The overall document explicitly cites terrorists as a source of potential risk in context of acquisition and use of WMD, but they are not explicitly called out in context of deterrence.

Strategies addressing nonstate actors appear to be focused predominantly on other forms of deterrence, which could involve threatening to punish potential states, nonstate institutions, and even individuals who might support terrorists acquiring WMD (including chemical weapons). The committee found no explicit declaratory statement of direct deterrence by punishment directed toward terrorists who used chemical weapons, in contrast to both the nuclear and biological domains.

There are substantial advantages to an explicit communication of the direct deterrence proposition (e.g., that the United States will take certain measures if terrorists utilize chemical weapons that would not otherwise be taken). Careful consideration should be given to incorporating direct deterrence of chemical terrorism into existing counter-WMD terrorism strategies.

RECOMMENDATION 5-1: The National Security Council should give careful consideration to incorporating direct deterrence of chemical terrorism into existing Chemical WMDT strategies.

Reducing Material Availability and Chemical Substitution

Chemicals are on a spectrum from extremely accessible (e.g., commercially available household chemicals), relatively accessible (e.g., many so-called TICs present in chemical plants and manufacturing facilities), to extremely inaccessible (e.g. organophosphate nerve agents and many of their key precursor chemicals). In theory, any chemical can be produced from readily available precursor chemicals. However, in practice, the technical barriers to producing certain chemicals are high. In some cases, for example nerve agent synthesis, the technical barriers are extremely high. Regu-

___________________

1 At the time of writing this report, the statutory authority for the CFATS program (6 CFR Part 27) expired and has yet to be reauthorized.

latory efforts to reduce material availability include the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Management Program Regulation, which aims to “reduce the likelihood of accidental releases at chemical facilities, and to improve emergency response activities when those releases occur.” (Final Amendments to the Risk Management Program (RMP) Rule, 2018). DHS’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency’s (CISA) established CFATS, which once played an important role in regulating material availability.

Another key avenue by which the risk of chemical terrorism can be reduced is to replace existing processes and materials with less toxic alternatives, often referred to as inherently safer technology. This obviously reduces the potential consequences of a chemical terrorist attack by making toxic materials less prevalent or by eliminating their use entirely. Overall, theft and use of the materials in commerce will become more difficult and less attractive. The likelihood of a chemical facility becoming a target for sabotage will also decrease. Occupational and environmental safety concerns have long driven industry to seek substitution as a strategy to mitigate hazards, and both Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and EPA have for decades encouraged and recognized innovative approaches for substitution. However, despite ongoing industry practice and some initiatives that previously operated under DHS’s CFATS program, the strategy documents reviewed by the committee do not cite chemical substitution as a key part of an overall chemical security strategy.

RECOMMENDATION 5-3: Substitution of safer alternative chemicals for hazardous chemicals in industrial and academic settings should be included as part of the overall strategy to impede acquisition of raw materials for chemical terrorism. The planning and development of these strategies should be spearheaded by DHS’s Chemical Information Sharing and Analysis Center under a reauthorized CFATS program and should continue to be conducted in conjunction with regulatory agencies, specifically, the EPA, OSHA, and representatives from industry and academic research environments.

Addressing Insider Threats

In certain sectors—often related to the materials consumed or produced therein—the threat lies not only in the theft of information and the disruption of an organization’s functions, but also in the possibility that sabotage by insiders could have extremely detrimental consequences for broader public health and safety. The accidental release of more than 40 tons of highly toxic methyl isocyanate from the Union Carbide insecticide plant in Bhopal, India in 1984 is an example of the scale of harm that could result from an accident occurring at a chemical facility (Broughton, 2005, Eckerman, 2005).

Despite this significance, strategic documents surveyed did not explicitly mention insider threat in the chemical terrorism context. While CFATS included some practical efforts to counter insider threats within the chemical industry, the scope of these efforts appears to be limited. The committee did not find evidence of a similar program at the level of CFATS, either directed towards government facilities or

within academic research institutions. Nonetheless, government and academic institutions are subject to research security requirements, including reliability programs or controlled access to chemicals via security clearances, which do have an active insider threat identification scope. The severe consequence of an insider at a chemical facility conducting or assisting an attack warrants explicit inclusion in existing strategies and comprehensive policies as a way to counter insider threats at any facility containing significant quantities of toxic chemicals.

RECOMMENDATION 5-4: Counter-insider threat activities should be incorporated explicitly into broader counter WMD strategy. The DHS should develop a strategy to ameliorate insider threats explicitly for the chemical domain.

Other Prevent and Counter Activities

Some activities the USG is undertaking are not mentioned in the strategy documents reviewed, including: military capabilities to provide early warning of chemical terrorism plots; law enforcement capabilities to counter chemical threats tactically; integration with broader counterterrorism and counter-smuggling efforts; and involvement with other multilateral activities beyond the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW). The absence of such activities from the strategies could impact policy implementation, such as budgeting, program prioritization, and other consequences. Including these activities in existing strategies would bolster their effectiveness.

RECOMMENDATION 5-5: Agencies should work to reconcile operational practice with policy by supplementing extant strategies to include current omitted effective activities and programs for countering chemical terrorism. This would ensure that effective practices are maintained, properly resourced, and reflected in comprehensive strategies.

Adequacy of Strategies to Respond to Chemical Terrorism

The vast majority of chemical incidents in the United States are not from terrorism, but are instead chemical releases from accidents, transportation incidents, or the results of natural phenomena, which over the period of 2012–2022 caused nearly one hundred recorded fatalities and almost two thousand injuries. When accidents occur, first responders have tools, training, and interagency agreements generally adequate for protecting the U.S. population, themselves, and the environment. The EPA is the primary agency coordinating response to such incidents, with support from several other agencies.

In this study, response to a chemical terrorism event is defined as the ability to minimize effects, sustain operations, and support follow-on actions. To assess the nation’s ability to respond to chemical terrorism, the committee reviewed the documents shown in chapter 6 and assessed response strategies for their ability to address the following questions:

- Does the U.S. strategy adequately enable response capabilities (e.g., operations coordination, information-sharing, medical support, and others) that minimize potential impact to life, property, and the environment?

- Is the strategy for responding to chemical terrorism, and the resources devoted to implement the strategy, aligned with the priorities of the United States (e.g., protecting the homeland, ensuring economic security, maintaining military strength) and aligned with the nation’s risk posture?

- Does the strategy anticipate emerging threats by suggesting the scientific research and interagency relationships necessary to respond to future threats?

The committee concluded that the current set of U.S. strategies, operational plans, and other resources has helped establish a network of capable first responder communities prepared for various chemical incidents regardless of their cause. However, improvements are needed in the following areas: need for first responder input, access to intelligence, information flow, and interagency coordination.

Need for First Responder Input

A major component for creating a robust strategy is to ensure critical information is collected and included from the first responder community. CISA released the Aviation Safety Communique (SAFECOM) Nationwide Survey to collect data from organizations that use technology for public safety, including emergency communication centers, emergency management, law enforcement, emergency medical personnel, and fire and rescue professionals. These types of input from relevant stakeholders in the response community will also eventually shape the direction of risk assessments.

Access to Intelligence

One concern raised in agency briefings is that information that would be most beneficial to first responders sometimes cannot be transmitted due to classification status of the information. At the recommendation of the 9/11 Commission, NCTC created a mobile app ACTknowledge, that shares unclassified counterterrorism reports, analysis, training resources, and alerts to users, however, as of January 2023 ACTknowledge was discontinued. Under National Institutes of Health (NIH), the National Library of Medicine hosts the mobile app and web-based platform Wireless Information System for Emergency Responders (WISER), which is designed to provide first responders with quick access to critical information during hazardous material incidents and other emergencies, but WISER was also discontinued in February 2023. Other emergency management tools are still operational, like Computer-Aided Management of Emergency Operations (CAMEO) and Chemical Hazards Emergency Medical Management (CHEMM) (EPA, n.d.; U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, n.d.). While the FBI is actively engaged in fostering communication with state and local first responders, including the National Guard, and industry, it is not clear that the outreach is comprehen-

sive or systematic. The risk is that an event could occur in an area where first responders would not be aware of, or in communication with FBI personnel or capability.

Top-Down and Bottom-Up Information Flow

All of the briefings received by the committee from various agencies demonstrated a clear understanding of looking upstream to current authorities, strategies, policies, and laws governing internal agency responsibilities. Less clear to the committee is how the requirements systematically flow downstream from higher-level policy to subsidiary organizations and finally to first responders. For example, roles and responsibilities of EPA and DHS/Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA) officials as well as their chain of communication could lead to confusion at the local level; the result, a potentially slower response to a chemical incident or attack.

The main framework employed by DHS FEMA to coordinate and respond to emergency, natural disasters, or terrorist events is the National Incident Management System (NIMS), within which is the National Response Framework (NRF) with two documents related specifically to responding to chemical incidents: ESF#10 and the Oil/Chemical Incident Annex. The committee found that the NRF adequately addressed chemical terrorism, but that translating U.S. strategies and frameworks into operational practice for chemical terrorism response remains a challenge.

Enhancing Interagency Coordination

Coordination among the different organizations can be improved to ensure first responders receive the needed information.

With respect to addressing chemical attacks specifically, FEMA’s WMD Strategic Group Consequence Management Coordination Unit coordinates with other parts of FEMA through its Chemical Biological Radiation and Nuclear (CBRN) Office. The FBI has designated WMD coordinators in its fifty-six field offices with the idea that building strong working relationships in place encourages a smoother response to a chemical incident. They routinely host WMD workshops to train first responders in recognizing the use of WMD during the initial stages of an incident.

RECOMMENDATION 6-6: Considering the complexity of the chemical threat space and USG coordination required for an effective response to a chemical event, the committee recommends continuing a robust program of interagency exercises and trainings that practice communication and resource sharing.

Priorities in a Shifting Threat Landscape

This report evaluating U.S. strategies to address chemical terrorism comes at a time when the nation’s highest-level strategies have shifted from focusing primarily on VEOs to focusing more on the Great Power Competition (GPC). In the words of President Biden,

The most pressing strategic challenge facing our vision is from powers that layer authoritarian governance with a revisionist foreign policy […] a challenge to international peace and stability. (NSS, Pg. 8)

This change indicates a shift in relative perceived threat and consequent prioritization, which will impact efforts against chemical terrorism. Changes in strategy will lead to changes in funding priorities.

While changes in funding priorities and operational adjustments are anticipated, the specific mechanism, magnitude, and timing are currently less understood. If federal agencies prioritize broadly applicable approaches to all areas of the Chemical WMDT enterprise, it will maximize the USG capacity for appropriate response.

RECOMMENDATION 7-1: The shift in the global threat landscape has led to a corresponding shift in countering WMD to a focus on GPC, but care should be taken to ensure that existing capabilities focused on countering terrorism are maintained. Recommendations based on revised risk assessments that are aligned with new national-level priorities should be developed.

DHS Security Strategies

How the strategic shift from VEOs to GPC will impact DHS’s strategic posture, programs, human resources, and missions is yet to be fully understood. The department has not yet published a strategy that both acknowledges the shift to the GPC and addresses chemical terrorism. Their 2020–2024 Strategic Plan does not specifically acknowledge GPC as a top national threat; in contrast, the 2021 China Strategic Action Plan (SAP) acknowledges the shift to the GPC but does not discuss chemical terrorism.

RECOMMENDATION 7-2 (Abbreviated): DHS should develop strategies, including an updated chemical defense strategy that consider the implications of the strategic shift to great power competition, including potential resourcing shifts, on reducing the risk of chemical threats and chemical terrorism.

DoD Strategies

The shift to GPC also impacts the DoD, though differently than the domestically focused DHS. DoD’s intersection with chemical terrorism is part of a broader concern about terrorism threats against the United States’ assets—and those of our allies—overseas and about terrorist assets that might mature into a threat against the homeland. In the National Defense Strategy (NDS), DoD embraces the shift to prioritizing GPC and will likely lead to a reallocation of resources supporting the new prioritization.

RECOMMENDATION 7-3: DoD should monitor risks associated with the shift in strategic focus and adapt if evidence of terrorist activities ramps back up.

Despite the changes in DoD and national strategy, it is not apparent how operations have adjusted to the new strategies nor is it clear how the IC will address information gaps.

RECOMMENDATION 7-4 (Abbreviated): The IC and its offices throughout the departments with significant chemical terrorism roles and responsibilities (DoD, DHS, Department of Justice (DOJ)) should take steps to ensure that counter chemical weapons programs, whether state-based or by nonstate actors, are not technologically deterministic.

Chemical Terrorism Risks

If GPC intensifies, there are potential implications for chemical terrorism threats beyond a possible reduction of resources available to address the threats. The decisions that states make may wittingly or unwittingly lead to a dramatic increase in the sophistication of chemical terrorism, in terms of both the agent employed and/or the means by which it is delivered (see data from Figure S-2). States might also choose to engage in offensive chemical weapons activities (as some, notably Russia, are suspected to be doing today) and technology, materials, expertise, and/or chemical agents might be illicitly transferred or diverted to nonstate actors. In addition, there is the potential for what might be categorized as “state terrorism”—as some have alleged both Russia and North Korea have done with targeted attacks in recent years. In the opinion of the committee, these factors could lead to reduced resources for countering weapons of mass destruction terrorism (CWMDT) broadly, although the mechanisms, magnitude, and timing are currently poorly understood.

RECOMMENDATION 7-5: DoD should conduct risk and threat assessments to understand how best to direct resources to address risks of chemical terrorism events in an era of GPC-focused strategies.

At the time of writing this report, the committee learned that CFATS’s statutory authorization was allowed to expire. Therefore, the CISA cannot enforce compliance with the CFATS regulations at this time.

RECOMMENDATION 7-6: Congress should immediately reauthorize the CFATS program and consider long-term reauthorization.

Threat-Agnostic Approaches to Medical Countermeasures

If resources for counterterrorism decrease due to the shift towards GPC, then a burden will be placed on existing programs to use their resources more efficiently in countering chemical threats. Despite the potential loss of focus on chemical terrorism,

the growing trend toward more broadly extensible strategies being implemented by many agencies may help reduce risk. DoD’s Chemical and Biological Defense Program (CBDP) and Biomedical Advanced R&D Authority (BARDA) have prioritized five diagnostic toxidromes for chemical exposures (neurologic, pulmonary, respiratory, metabolic, vesicating), which bypasses the need to identify the specific agent. This has positioned BARDA to more readily develop and deploy effective chemical medical countermeasures across multiple sectors to “treat the injury, not the agent.” (Chemical Medical Countermeasure Overview, 2024)

RECOMMENDATION 7-7: Federal agencies should prioritize broadly applicable approaches beyond the specific mission sets represented by the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command Chemical Biological Center (DEVCOM CBC), BARDA, and CISA, to all areas of the CWMDT enterprise to maximize the United States’ government capacity for appropriate response on time scales of relevance.

BUDGET RECOMMENDATIONS

The committee heard from several briefers that budgets are inadequate to address the breadth of possible chemical threats, even for agencies for which WMD is the highest priority. The material reviewed by the committee showed insufficient detail to allow a robust assessment of budgets likely to be required to implement strategies effectively, particularly for offices whose missions cover both chemical and biological threats. Revised risk assessments are needed to reprioritize risks guided by new strategies, so that strategy-aligned budgets can be created. To ensure a balance between different efforts as a result of risk assessments, as alluded to in section 1.1.2, a distinction between countering chemical and countering biological efforts is needed.

RECOMMENDATION 7-8: WMD budgets should be aligned with evolving strategic priorities.

RECOMMENDATION 7-9: Chemical WMDT budgets should incentivize activities that transition promising research to operations.

The committee recommends that chemical terrorism risk assessments (e.g., full risks, threats only, national-level, state-level, and others) be performed in the context of the latest strategies to align budget priorities with strategic priorities, and most clearly understand where and why the United States is accepting risk. Table S-1 shows the budget functions and resources the committee believes should be considered under budgetary constraints that may result from the national strategic shift to GPC. These factors include risk priorities that are expressed in budget requests.

TABLE S-1 Recommended Budget Priorities Based on National Strategic Shift to GPC

| Budget Function or Resource | Benefit of Retention |

|---|---|

| Fund comprehensive risk assessments based on the priorities set forth in recent national security strategies. | Allows forward-thinking strategic planning and preparedness. Enables agility to focus on new priorities when national strategy evolves. Identifies alignment between funding emphasis and strategy. Identifies where risk is being accepted when alternate, more strategy-aligned, investments are made. |

| Maintain the intelligence community’s capabilities and expertise specific to terrorist groups (VEOs & Racially, Ethnically, and Motivated Violent Extremists (REMVEs) and to understanding their motivations. | Ensures subject matter expertise in the terrorism threat space is retained. Allows for rapid identification of and adaptation to emerging threats. |

| Support basic scientific and social science research specifically related to countering chemical terrorism, e.g., understanding social behavior related to emerging threats. | Retains a strong talent base to address future, perhaps unanticipated, chemical threats/substances and the motivations to use them. Threats change and without natural and social scientific research, it will be difficult to adapt to changes, or in some cases, even understand that and/or why they have occurred. |

| Strengthen insider threat programs related to physical, cyberphysical, and cybersecurity across the chemical industry. | Secures physical facilities from being subverted to cause toxic releases or the theft of precursor chemicals. Protects vulnerable information systems from being used in espionage and for chemical attacks. |

| Support training and exercises to advance international chemical security priorities through continued initiatives with, for example, the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI) partners, North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) allies, nongovernmental organizations, and other international stakeholders. | Increases capacity and tactical readiness internationally, thereby decreasing global threat and decreasing reliance on U.S. assets to respond. |

| Fund initiatives that work with international partners to enhance chemical security, identify, prevent/counter, and respond to chemical threats worldwide. | Strengthens alliance and builds stronger communication networks among relevant international agencies. |

| Continue emphasizing programs employing threat-agnostic approaches to identify and respond to chemical attacks. | Enables more economical, efficient, and effective responses, especially in times when chemical terrorism, or other national security concerns, may be deemphasized. |

| Encourage more flexible capability portfolio management models and processes that reduce bureaucratic constraints to accelerate adoption of emerging technologies. Utilize innovation like the cross-functional team program management approaches model. | Enables the flexibility to most promptly address evolving threats and to more effectively facilitate innovation adoption and integration. (Esper and Lee James, 2023) |

REFERENCES

Binder, M., and G. Ackerman. 2020. “Profiles of Incidents Involving CBRN and Non-State Actors (POICN) Database. National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism: College Park, MD.

Broughton, Edward. 2005. “The Bhopal Disaster and Its Aftermath: A Review.” Environmental Health 4: 6.

CAS. (n.d.). CAS registry. https://www.cas.org/cas-data/cas-registry.

Eckerman, Ingrid. 2005. The Bhopal Saga—Causes and Consequences of the World’s Largest Industrial Disaster. India: Universities Press.

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). (n.d.). CAMEO Chemicals. https://www.epa.gov/cameo.

Executive Office of the President. 2002. National Strategy to Combat Weapons of Mass Destruction.

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (n.d.). 2002. CHEMM. https://chemm.hhs.gov.

This page intentionally left blank.