Chemical Terrorism: Assessment of U.S. Strategies in the Era of Great Power Competition (2024)

Chapter: 7 Chemical Terrorism in the Era of Great Power Competition: Cross-Cutting Findings, Conclusions, Recommendations

7

Chemical Terrorism in the Era of Great Power Competition: Cross-Cutting Findings, Conclusions, Recommendations

Summary of Key Findings, Conclusions, and Recommendations

FINDING 7-1: The highest-level strategies of the United States, the National Security Strategy (NSC) and National Defense Strategy (NDS), have overtly shifted away from focusing on the threats from violent extremist organizations to great power competition (GPC) in recent years. This change indicates a shift in relative perceived threat and consequent prioritization and will impact efforts against chemical terrorism. Changes in strategy lead to changes in funding priorities, and while operational changes are anticipated from this major strategic shift, neither the mechanism, magnitude, nor timing are currently understood.

RECOMMENDATION 7-1:The shift in the global threat landscape has led to a corresponding shift in countering weapons of mass destruction (WMD) to a focus on GPC, but care should be taken to ensure existing capabilities focused on countering terrorism are maintained. Recommendations based on revised risk assessments that are aligned with new national-level priorities should be developed.

FINDING 7-2: The Department of Homeland Security (DHS), while acknowledging the national strategic shift to great power competition in the 2021 China Strategic Action Plan, has not published a strategy that both acknowledges the shift and also addresses chemical terrorism.

RECOMMENDATION 7-2: The DHS should develop strategies, including an updated chemical defense strategy, that consider the implications of the strategic shift to GPC, including potential resourcing shifts, on reduc-

ing the risk of chemical threats and chemical terrorism. Such strategies, whether public or not, should lead to specific, actionable plans and detail expected outcomes for counterterrorism activities in the context of current national strategic priorities. The committee acknowledges that such documents may be in progress.

FINDING 7-3: The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) NDS acknowledges that terrorism risks may rise as program priorities shift to other priorities and other circumstances evolve.

RECOMMENDATION 7-3: The DoD should monitor risks associated with the shift in strategic focus and adapt if evidence of terrorist activities ramps back up.

RECOMMENDATION 7-4: The intelligence community and its offices throughout the departments with significant chemical terrorism roles and responsibilities (DoD, DHS, DOJ) should take steps to ensure that counter chemical weapons programs, whether state-based or by nonstate actors, are not technologically deterministic. This will require efforts to address gaps in knowledge or approaches which may arise as new personnel are hired as well as other transitions. The best way to do this needs to be determined by individual offices and agencies in consultation with the wider homeland security or defense community.

CONCLUSION 7-5: The shift in strategic focus to GPC will likely lead to reduced resources for countering weapons of mass destruction terrorism broadly, although the mechanisms, magnitude, and timing of those changes are currently poorly understood. How these changes are made is important; sudden changes without thoughtful preservation of functions could impede tactical readiness against chemical terrorist threats and increase risk in unforeseen or undesirable ways.

RECOMMENDATION 7-5: The DoD should conduct risk and threat assessments to understand how best to direct resources to address risks of chemical terrorism events in an era of GPC-focused strategies.

FINDING 7-6: The legislation establishing the Chemical Facility Anti-Terrorism Standards (CFATS) program (6 CFR Part 27) expired at the end of July 2023. Reauthorization will provide regulatory certainty for one of America’s critical infrastructures in support of reducing the threat of chemical terrorism.

RECOMMENDATION 7-6: Congress should immediately reauthorize the CFATS program and consider long-term reauthorization.

FINDING 7-7: Current broadly extensible strategies could support effective identification, prevention, and response to the widest range of anticipated and yet-to-be-recognized chemical agents.

CONCLUSION 7-7: Further adoption of approaches with broad extensibility can partially mitigate loss of focus on chemical terrorism due to the shift to GPC.

RECOMMENDATION 7-7: Federal agencies should prioritize broadly applicable approaches beyond the specific mission sets represented by the U.S. Army Research and Development Center for Chemical and Biologic Defense Technology (DEVCOM CBC), Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), and Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), to all areas of the Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction and Terrorism (CWMDT) enterprise to maximize the United States’ government capacity for appropriate response on time scales of relevance.

CONCLUSION 7-8: Strategy documents that include implementation plans with descriptions of current levels of inter- and intra-agencies coordination will significantly enhance communications across relevant entities. The areas of identify, prevent, counter, and response to chemical threats and chemical terrorism will especially benefit from this improvement. With respect to chemical terrorism events, communication between state and local law enforcement (LE) during an emergency could be impeded by classification issues.

RECOMMENDATION 7-9: WMD budgets should be aligned with evolving strategic priorities.

RECOMMENDATION 7-10: CWMDT budgets should incentivize activities to transition from promising research to operations.

FINDING 7-11: The material reviewed by the committee showed insufficient detail to allow a robust assessment of budgets likely to be required to implement strategies effectively, particularly for offices whose missions cover both chemical and biological threats.

CONCLUSION 7-11: Revised risk assessments are needed to reprioritize risks guided by recently issued strategies, so that strategy-aligned budgets can be created. To ensure a balance among efforts initiated by revised assessments, a distinction between countering chemical and countering biological efforts is needed.

The committee was tasked with evaluating strategies against chemical terrorism at a time of evolving national strategy. The United States’ highest-level strategies recently explicitly shifted away from focusing primarily on violent extremist organizations (VEOs) to focusing on GPC,1 which is indicative of a shift in perceived threat prioriti-

___________________

1 Beginning with the 2018 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America: Sharpening the American Military’s Competitive Edge, December, 2017, and continuing and increasing in the current administration’s strategies.

zation. This shift in strategy does not mean terrorism is now regarded as unimportant; rather, it simply means that other issues have risen in importance, a fact which is most apparent in the National Security Strategy (NSS, 2022) and the 2022 National Defense Strategy (NDS, 2022). The Biden Administration NSS states:

The most pressing strategic challenge facing our vision is from powers that layer authoritarian governance with a revisionist foreign policy… a challenge to international peace and stability. (Pg. 8)

The document does not ignore terrorism completely. The NSS also states:

America remains steadfast in protecting our country and our people and facilities overseas from the full spectrum of terrorism threats that we face in the twenty-first century. (Pg. 30)

The NDS delineates four top-level defense priorities—none of which directly mention terrorism of any kind. Although terrorism, including chemical attacks and VEOs, are mentioned in the document, they are implicitly subordinated in the 2022 NDS by neither including them in the top-level priorities, nor mentioning them in the executive summary or the conclusion of the strategy.

Both of the above strategies portray a similar theme: While the threat of terrorism remains real, our nation is shifting its focus to prioritize different strategic threats, namely GPC over VEOs. With the apparent shift of strategic focus to GPC comes a shift in risk perception, risk assessment, and risk acceptance. Eventually, new strategies and risk assessments generate new mitigation strategies; new guidance, policies, and laws; and ultimately, new tactics, techniques, and protocols (TTPs) on the ground. The full ramifications of recent strategic shifts have not yet been realized at all levels of the government, nor at all agencies.

FINDING 7-1: The highest-level strategies of the United States, the NSS and NDS, have overtly shifted away from focusing on the threats from VEOs to GPC in recent years. This change indicates a shift in relative perceived threat and consequent prioritization and will impact efforts against chemical terrorism. Changes in strategy lead to changes in funding priorities, and while operational changes are anticipated from this major strategic shift, neither their mechanism, magnitude, nor timing is currently understood.

RECOMMENDATION 7-1: The shift in the global threat landscape has led to a corresponding shift in countering WMD to a focus on GPC, but care should be taken to ensure that existing capabilities focused on countering terrorism are maintained. Recommendations based on revised risk assessments that are aligned with new national-level priorities should be developed.

7.1 DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY (DHS) STRATEGY

DHS was created in response to the most significant international terrorism attack perpetrated against the United States. Because DHS has a primarily domestic

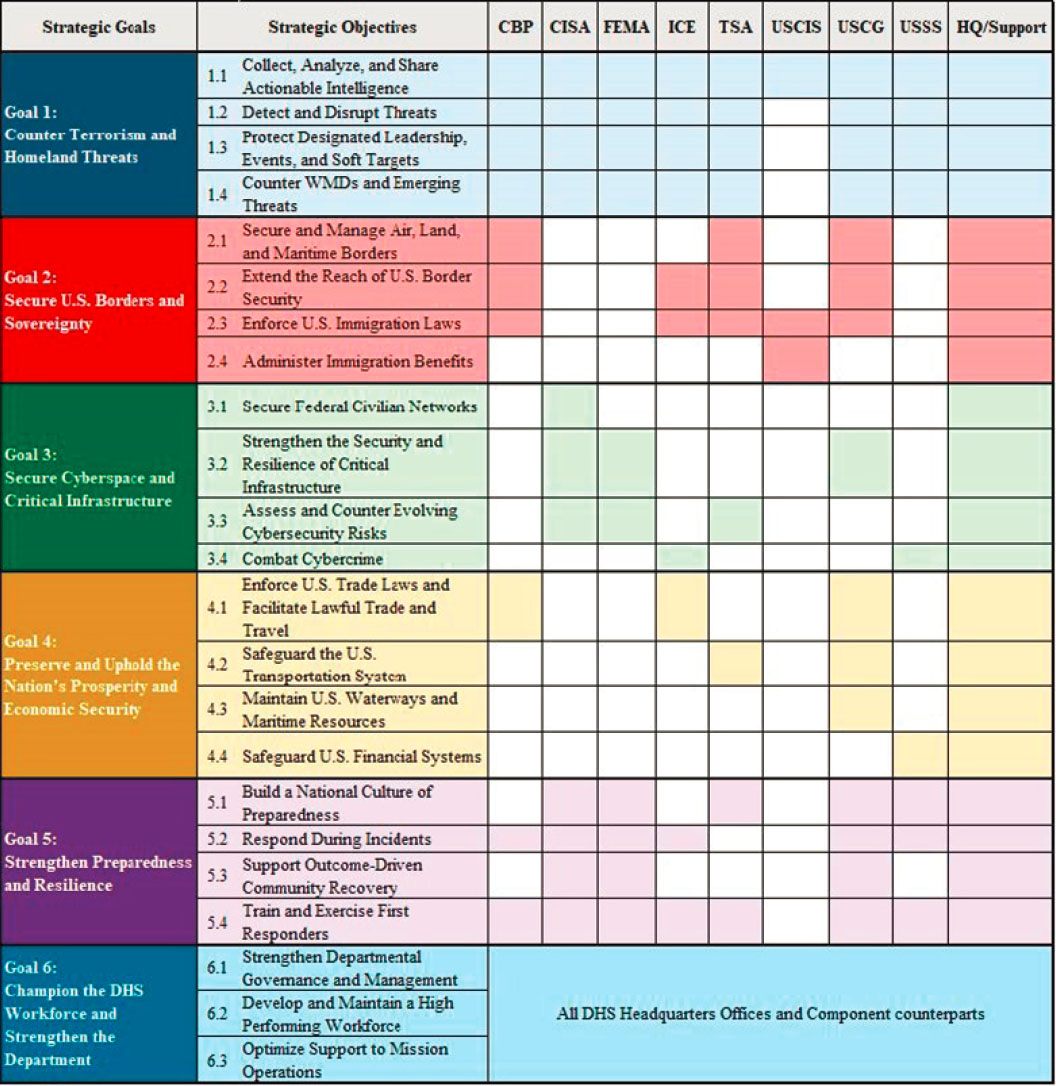

security function, its risk and threat assessments will not necessarily follow the same pattern as DoD or the intelligence community IC. Furthermore, how the strategic shift from VEOs to GPC will impact DHS’ strategic posture, programs, human resources, and missions is yet to be fully understood. Reducing the terrorism threat, including chemical terrorism, will continue to remain at the organization’s core, as articulated in the overview of the DHS document, Preventing Terrorism, “Protecting the American people from terrorist threats is the reason DHS was created, and remains our highest priority” (DHS, n.d.). Preventing terrorism is one of 13 issues (with some overlapping scope) handled by DHS. Furthermore, DHS’s 2020–2024 Strategic Plan outlines six strategic goals that align with general national prosperity under VEO-focused or GPC-focused strategies, but they do not specifically acknowledge GPC as a top national threat (see Figure 7-1).

DHS overtly acknowledges the shift to GPC in its 2021 China Strategic Action Plan (SAP)—which predates the most recent NSS—and which asserts that its fundamental mission of safeguarding the homeland, upholding DHS’s values, and preserving the American way of life remains, even in the evolving geopolitical environment (DHS, 2021). The SAP addresses the following areas: maritime security, cybersecurity and critical infrastructure, trade and economic security, and border security and immigration. Aspects of terrorism including chemical terrorism are absent from the discussion. The only chemical threat specifically mentioned was China’s direct and indirect involvement in supplying fentanyl and its precursors to drug cartels and transnational criminal organizations, contributing to more than 70,000 deaths in the United States in 2019 (DHS, 2021, 6, 9).

More recently, in April 2023, DHS published the Third Quadrennial Homeland Security Review (QHSR) (DHS, 2023). While recognizing the NSS, the QHSR only implicitly emphasizes the shift in national strategy to GPC by highlighting issues facing the United States as a result of GPC. The QHSR does not explicitly discuss China’s role in the Strategic Competition section of the document but does detail actions to address issues facing the U.S. because of strategic competition with China specifically. The document embraces the role of increased partnerships in DHS’s strategy, a theme found in the NSS and NDS. With respect to terrorism, the opening letter from Secretary Mayorkas states,

Today, the most significant terrorist threat stems from lone offenders and small groups of individuals, especially domestic violent extremists, while the threat of international terrorism remains as foreign terrorist organizations have proven adaptable and resilient over the past two decades and individuals inspired by their ideologies have continued to launch attacks in their names.

More specific to chemical terrorism is the DHS Chemical Defense Strategy of December 2019, which the committee evaluated in detail. As of June 2023, the DHS Chemical Defense strategy has not been updated after the release of the DHS 20–24 strategic plan nor since national strategies have shifted their focus to GPC (DHS, 2022). QHSR does not specifically address chemical terrorism apart from other types of terrorism.

SOURCE: DHS, 2020.

In sum, DHS has released several documents outlining the organization’s plans to address aspects of the shift to GPC or chemical terrorism. However, a key question remains: With a shift to GPC-focused strategies by the nation, are DHS strategies against chemical terrorism threats (and terrorism threats more broadly) appropriately prioritized and resourced?

FINDING 7-2: The DHS, while acknowledging the national strategic shift to great power competition in the 2021 China SAP, has not published a strategy that both acknowledges the shift and also addresses chemical terrorism.

RECOMMENDATION 7-2: The DHS should develop strategies, including an updated chemical defense strategy, that consider the implications of the strategic shift to GPC—including potential resourcing shifts—on reducing the risk of chemical threats and chemical terrorism. Such strategies, whether public or not, should lead to specific, actionable plans and detail expected outcomes for counterterrorism activities, in the context of current national strategic priorities. The committee acknowledges that such documents may be in progress.

7.2 DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE STRATEGY

The shift to GPC also impacts the DoD, though differently than the domestically focused DHS. DoD’s intersection with chemical terrorism is part of a broader concern about terrorism threats against U.S. assets—and those of our allies—overseas and about terrorist assets that might mature into a threat against the homeland. In the NDS, DoD embraces the shift to prioritizing GPC, which will likely lead to a reallocation of resources supporting the new prioritization. The NDS (2022) states:

This strategy will not be successful if we fail to resource its major initiatives or fail to make the hard choices to align available resources with the strategy’s level of ambition.” The NDS also states “No strategy will perfectly anticipate the threats we may face, and we will doubtless confront challenges in execution.

As noted at the beginning of this chapter, the shift in focus will likely lead to shifts in resources, which will inevitably affect risk profiles in other areas. The NDS is clear-eyed about this reality, which likely will help ensure that the department effectively implements the strategy and assesses its impact over time (DoD, 2022).

FINDING 7-3: The U.S. DoD NDS acknowledges that terrorism risks may rise as program priorities shift to other priorities and other circumstances evolve.

RECOMMENDATION 7-3: The U.S. DoD should monitor risks associated with the shift in strategic focus and adapt if evidence of terrorist activities ramps back up.

Although the NSS and NDS have been updated to a GPC focus, as of June 2023, joint doctrine reflected in Joint Publications (JP 3-11, JP 3-40, JP 3-41) has not been updated to reflect this shift since the release of the most recent NDS.2

___________________

2 NOTE: The committee recognizes that at the time of producing the report, the newest NDS for CWMD may not be publicly released.

.. states that the:

Department of Defense derives its national strategic direction primarily from the President’s guidance in the NSS, presidential directives, and other national strategic documents… (Pg. viii)

However, as doctrinal documents, the Joint Publications describe principles as to how the Joint Force fights wars that do not change with changes in strategy. As such, Joint Publications do not generally undergo revision and updating when shifts in strategy occur, unless the principles described in doctrine no longer apply or have changed in some way. Therefore, it remains to be seen if the Joint Publications will need to be revised specifically in response to the strategic shift to GPC.

7.3 INTELLIGENCE COMMUNITY STRATEGY

The committee also heard from key counterterrorism program managers from the IC in a public information-gathering meeting. One example of attitudes regarding counterterrorism during the shift to GPC was presented by Tom Breske, Senior Advisor for the Weapons of Mass Destruction Counterterrorism Team under the Directorate of Strategic Operational Planning at the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC). Breske was posed the question:

What is the most under-recognized or un-recognized threat or problem (current or future) related to responding to and reducing chemical terrorism threats?

Breske responded,

As our Nation’s focus shifts to the threat posed by nation-state near-peer competitors such as China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea, we [the United States] must maintain a watchful eye on nonstate actors and violent extremist organizations for indications and warnings of interest in accessing, procuring, manufacturing, training, and potential use of WMD, both at home and abroad. Understanding that an effective Counter WMD-Terrorism strategy depends upon an effective Counterterrorism capability, shifts in resources and priorities away from counterterrorism will likely have downstream impacts on our ability to counter chemical terrorism.

Breske’s answer above speaks to the balancing act of changing strategic priorities when the United States does not (publicly) know the origin of the next WMD threat. This comment was similar to the responses of other U.S. officials briefing the committee. The shift to GPC is recognized and prioritized in strategy in the IC, but how it is operationalized with respect to chemical terrorism across the IC as a whole is not readily apparent.

RECOMMENDATION 7-4: The IC and its offices throughout the departments with significant chemical terrorism roles and responsibilities (DoD, DHS, DOJ) should take steps to ensure that counterchemical weapons programs, whether

state-based or by nonstate actors, are not technologically deterministic. This will require efforts to ensure as gaps in knowledge, approaches that may arise as new personnel are hired, and others transition. The best way to do this needs to be determined by individual offices and agencies in consultation with the wider homeland security or defense community.

7.4 CHEMICAL TERRORISM RISKS

In addition to the strategic shift to GPC, the NSS speaks with a sense of urgency in implementation. Without recapitulating the entire strategy, the urgency is best summarized in the final words of the NSS, “There is no time to waste” (NSS, 2022, Pg. 48).

With respect to chemical terrorism, none of the briefings to the committee (see List of Briefers in Appendix A) fully acknowledged the GPC as the top strategic priority of the United States nor the urgency desired in the most recent national strategies. To be fair, often the briefers focused on more operational aspects related directly to chemical defense and this was not in the original set of questions put forward by the committee. The committee acknowledges that the nation is in a dynamic state of developing new strategies.

If GPC intensifies, there are potential implications for chemical terrorism threats, beyond a possible reduction of resources available to address the threats. As discussed in Chapter 4, decisions states make may wittingly or unwittingly lead to a dramatic increase in the sophistication of chemical terrorism, in terms of both the agent employed and/or the means by which it is delivered. Another increased risk of the shift to GPC is that assumptions about what chemical terrorism will look like will increasingly be influenced and modeled on state-based programs, motivations, and thinking. While there certainly are lessons to be learned, the capacity, capability, and willingness to innovate—as well as network structures—differs significantly between states and nonstate actors. As attention on nonstate actors and threats decrease, the tendency to treat terrorism as a “lesser included” case or type of chemical weapons use may increase given constraints on budgets and time. Terrorism is different—a fact that is particularly important in the context of strategies to identify and counter, including deterrence.

CONCLUSION 7-5: The shift in strategic focus to GPC will likely lead to reduced resources for CWMDT broadly, although the mechanisms, magnitude, and timing are currently poorly understood. How these changes are made is important; sudden changes without thoughtful preservation of functions could impede tactical readiness against chemical terrorist threats and increase risk in unforeseen or undesirable ways.

RECOMMENDATION 7-5: The DoD should conduct risk and threat assessments to understand how best to direct resources to address risks of chemical terrorism events in an era of GPC-focused strategies.

7.5 APPROACHES TO IDENTIFY, PREVENT, COUNTER, AND RESPOND WITH BROAD APPLICABILITY

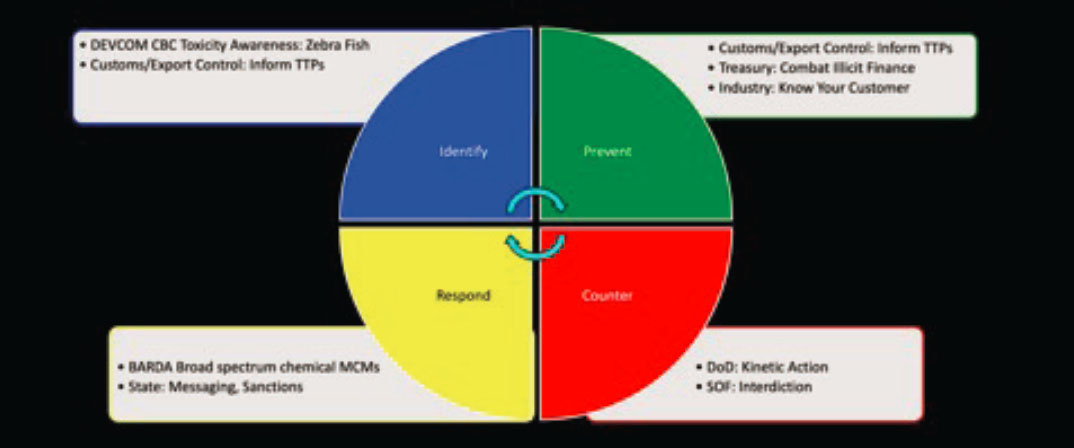

The following section describes key themes related to the use of broadly extensible strategies to identify, prevent, and respond as discussed across the previous chapters. For example, the surveillance-like use of zebra fish by DEVCOM CBC could also be applied to screening for toxicity when identifying chemical agents. Some agencies already perform counterterrorism activities and strategies that are similarly broad in their applicability, and which will be important to retain. A selection of these broad approaches is summarized and depicted in Figure 7-2.

Identify

“Identify” strategies must facilitate the discovery of the actor, intended agent(s), and delivery mechanisms and tactics. In terms of identifying an actor and intended delivery mechanisms and tactics, the FBI’s current practice of informing export control and transportation security officials of new Tactics, Techniques, and Protocols (TTPs) utilized by specific VEOs facilitates more timely identification of VEO activities (FEMA, 2016). Meanwhile, in terms of identifying the agent being pursued by a VEO, being able to detect the fact that a chemical or class of chemicals that is somehow associated with a VEO is linked to a particular toxidrome can help identify which chemicals should be considered threats (e.g., surveillance-like application of DEVCOM CBC’s work with zebra fish).

Prevent

As with “identify,” making export control and transportation security officials aware of new TTPs utilized by a specific VEO can empower them to also effectively

SOURCE: Kabrena Rodda, 2023.

prevent a planned attack. Similarly, efforts undertaken to implement the 2022 National Strategy for Combatting Terrorist and Other Illicit Financing help to identify VEO activities which could in turn help prevent a planned attack (Treasury, 2023). Information derived from lines of effort in this strategy can support and inform Know Your Customer (KYC) initiatives undertaken by chemical producers and equipment manufacturers (SWIFT, n.d.).

At the time of writing this report, the committee learned that CFATS’s statutory authorization was allowed to expire. Therefore, CISA

cannot enforce compliance with the CFATS regulations at this time. This means that CISA will not require facilities to report their chemicals of interest or submit any information in the Chemical Security Assessment Tool (CSAT, perform inspections, or provide CFATS compliance assistance, amongst other activities. CISA can no longer require facilities to implement their CFATS Site Security Plan or CFATS Alternative Security Program” (CISA, 2023).

FINDING 7-6: The legislation establishing the CFATS program (6 CFR Part 27) expired at the end of July 2023. Reauthorization would provide regulatory certainty for one of America’s critical infrastructures in support of reducing the threat of chemical terrorism.

Given the role CFATS played in preventing and countering chemical terrorism (see Chapter 5 full discussion), the committee directs the following recommendation to Congress. The American Chemistry Council (ACC) also supports the reauthorization of the CFATS program (ACC, 2023).

RECOMMENDATION 7-6: Congress should immediately reauthorize the CFATS program and consider long-term reauthorization.

Counter

Activities undertaken under “counter” largely fall under DoD or Special Operations Forces (SOF) and FBI and are perhaps the most broadly applicable to each CWMDT focus area. In the case of DoD, direct kinetic action against a VEO may be the most effective at countering a WMDT attack that is already underway. SOF could be made aware of specific supply nodes to facilitate such activities.

Respond

BARDA’s practices of using existing chemical medical countermeasures (MCMs) for prioritized toxidromes and to promote decontamination as a first step whenever possible are likely to facilitate time-relevant response in the aftermath of an attack and to make sure first responders are aware of, and equipped to treat, the most likely toxidromes. More broadly, diplomatic efforts and messaging directed toward attributing attacks to specific VEOs and entities who support them can be highly effective without

having to identify the specific chemical used in an attack (2018 National Strategy for Countering WMDT Terrorism; Joint Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction).

7.6 THREAT-AGNOSTIC APPROACHES TO MCMS AGAINST CHEMICAL THREATS

If resources for counterterrorism decrease due to the shift toward GPC, then a burden will be placed on existing programs to use their resources more efficiently in countering chemical threats. Despite the potential loss of focus on chemical terrorism, the growing trend toward more broadly extensible strategies being implemented by many agencies (see Chapter 2) may help reduce risk. By focusing response, particularly MCM, on the main physical and symptomatic effects of a chemical rather than the particular chemical or how and why it was used, responders may address the impact of chemical events more quickly.

Explicit adoption of a threat agnostic, or agent agnostic, approach in the context of response, (e.g., MCM development, and the explanation of the reasoning behind that change in approach) can also be found in the DoD’s CBDP Approach for Research, Development, and Acquisition of Medical Countermeasure and Test Products (CBDP, 2022).

To better prepare the Joint Force against future and unknown threats, including naturally occurring emerging pathogens, the Chemical and Biological Defense Program (CBDP) will pivot away from viewing the threat landscape as a defined list of known biological and chemical agents toward removing or reducing the impact of agents’ effects. This shift demonstrates how the CBDP will view medical countermeasure (MCM) response as a spectrum that requires investing in the development of broad-spectrum (or nonspecific) MCM and test products and establishing capabilities to rapidly develop narrow spectrum (or specific) MCM and test products. (Pg. 1)

Notably, a broad spectrum, rather than specific one-bug(agent)-one-drug, approach has been a goal in the realm of biological threats for many years. In 2007, the CBDP initiated an effort that became known as the Transformational Medical Technologies Initiative (TMTI) to “develop broad-spectrum medical countermeasures against advanced bio-terror threats, including genetically engineered, intracellular bacterial pathogens and hemorrhagic fevers.” (TMTI, 2007, Pg. 3)

TMTI identified: “the possibility that future state or nonstate adversaries could develop and deploy new genetically engineered biological threats for which current countermeasures would be ineffective and the time needed to develop defense would be insufficient” (TMTI, 2007, Pg. 3) as a driver for the major policy endeavor as part of science and technology efforts to respond to national security threats that the military might have to face in future years. In so doing, even as the threat evolves (e.g., use of different chemical agents or different types or sources of attack), a given MCM should continue to be effective.

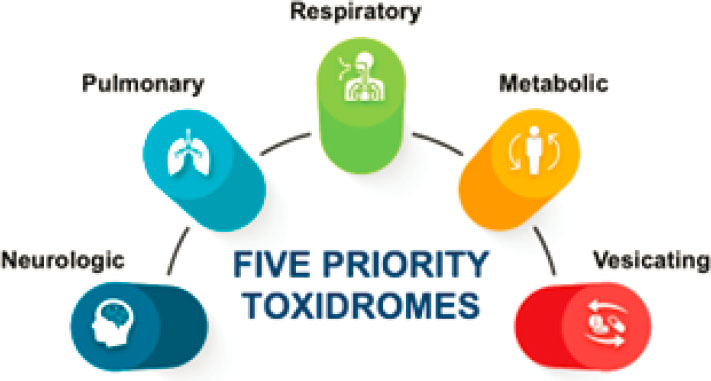

Building on earlier work from the DoD’s CBDP, Figure 7-3 shows BARDA’s prioritization of five diagnostic toxidromes for chemical exposures (neurologic, pulmonary, respiratory, metabolic, vesicating) bypasses the need to identify the specific agent that

SOURCE: BARDA Chemical MCMs Program.

caused the injury and allows for “broad spectrum therapeutic utility” (BARDA) using FDA approved drugs for treatment. The adoption of a toxidrome-based approach can be observed in BARDA’s CBRN MCM chemical threat portfolio, which as of June 2023, lists 16 drugs undergoing different phases of development whose purpose is to treat both chemical-specific injury and non-agent-specific symptoms (BARDA, n.d.). Alteplase, for example, is a therapeutic that, if approved, will be the first drug to treat sulfur mustard inhalation or pulmonary exposure. RWJ-800088 thrombopoietin mimetic is another drug that aims to address both the radiation/nuclear and chemical threat areas by protecting vulnerable human cells from radiation and chemical exposures. It also accelerates recovery in the lungs and thrombocytopenia (low platelet counts in the blood). BARDA’s toxidrome adoption and growing CBRN MCM portfolio have positioned the agency to more readily develop and deploy effective chemical medical countermeasures across multiple sectors to “treat the injury, not the agent” (BARDA, n.d.).

The committee endorses this approach to MCMs and notes that the same kind of conceptual approach may apply to identifying and preventing threats. Many counterterrorism programs have long taken this kind of approach. For example, major terrorist plots require financing, secrecy, and communications. As mentioned earlier, several intelligence, LE, and threat reduction programs seek to track and disrupt illicit financing, make it harder to operate without observation, and monitor or disrupt communications among threat actors. In an environment of increasingly constrained resources, extending this conceptual approach could be an efficient strategy.

FINDING 7-7: Current broadly extensible strategies could support effective identification, prevention, and response to the widest range of anticipated and yet-to-be-recognized chemical agents.

CONCLUSION 7-7: Further adoption of approaches with broad extensibility can partially mitigate the loss of focus on chemical terrorism due to the shift to GPC.

RECOMMENDATION 7-7: Federal agencies should prioritize broadly applicable approaches beyond the specific mission sets represented by the U.S. Army DEVCOM CBC, BARDA, and CISA, to all areas of the CWMDT enterprise to maximize the United States’ government capacity for appropriate response on time scales of relevance.

CONCLUSION 7-8: Strategy documents that include implementation plans with descriptions of current levels of inter- and intra-agencies coordination will significantly enhance communications across relevant entities. The areas of identify, prevent, counter, and response to chemical threats and chemical terrorism will especially benefit from this improvement. With respect to chemical terrorism events, communication between state and local law enforcement during an emergency could be impeded by classification issues.

7.7 SIMILARITIES AND CROSSOVER IN EFFORTS TO COUNTER THREATS FROM BIOTERRORISM AND CHEMICAL TERRORISM

Addressing biological and chemical threats requires inter- and multidisciplinary approaches that bridge the life, data, medical, physical, and social sciences, along with engineering, skill sets, and expertise. This includes the importance of data integration when information is coming in from different areas. Historically, much analysis has been technologically deterministic and/or based on limited empirical case studies and often limited analysis. While the United States tends to focus on technological solutions to both chemical terrorism and bioterrorism threats, there is less policy focus on motivation for both forms of terrorism.

A number of important and effective programs were developed after 9/11 to enhance the capabilities of the United States to prevent, prepare for, detect, respond, mitigate, and recover from terrorism events. Over time, many programs have been hampered by the gradual erosion of federal support and competing challenges. These include critical diagnostic networks and resources, surveillance efforts (national and international), and exercise programs to integrate cross-sector emergency personnel groups together.

Coordination across and inside government agencies is important. While there is a good deal of coordination—some very effective—within the chemical terrorism defense communities and within the bioterrorism defense communities, crossover between the two communities is often lacking. The United States government (USG) would benefit from increased sustained interaction. Coordination across and among federal, county, state, local, territorial, and tribal (SLTT) governments is critical and often a challenge. Training and exercises are critical for planning, preparedness, response, and remediation.

Mis- and disinformation represent an expanding challenge for chemical and biological threats and require additional study to identify mechanisms to effectively counter their influence. These studies should inform U.S. policies to counter mis- and disinformation. The critical need for clear consistent information is recognized at the federal level in responding to chemical and bioterrorism incidents; how to deal with

mis- and/or disinformation is often not included. (Perhaps a consequence of broader USG challenges of dealing with mis/disinformation rather than unique to any WMD). Uncertain information exists regarding interactions between the federal and state levels or at state levels.

- The approach to assessing and addressing biological and chemical threats should take human, plant, animal, and ecosystem health into account.

- In terms of attribution, reference collections and databases have been significantly improved or outright created for both chemical and biological threats. In the case of databases relating to bioterrorism threats, the level of curation (i.e., how good is the data), has not been pursued/validated as well as with chemical terrorism threats. Much of this may be due to the newness of the underlying technology (e.g., genetic and microbiome databases). This is a potential vulnerability that may not be well recognized (i.e., are we fooling ourselves into believing we have greater capabilities than we do?).

- New technologies are neither panaceas nor inherently threats. The underlying drivers and manner in which people may choose to use/misuse them are understudied/under-recognized in U.S. policies.

- Experts do not agree on the nature, scope, or scale of biological and chemical terrorism threats. Lots of uncertainty surrounds this area.

7.8 BUDGET RECOMMENDATIONS

Through a series of information-gathering meetings, several briefers noted to the committee that budgets were inadequate to address the breadth of possible chemical threats. (See list of briefings in Appendix A.) Presenters also indicated concern that constrained budgets may make it difficult to invest sufficiently in promising low technology readiness level (TRL) concepts to enable them to mature sufficiently for transition into operational use. Even when countering WMD terrorism was among the highest priorities, some federal agencies had tightly constrained budgets to counter chemical terrorism. For example, in an information-gathering meeting, the committee was informed that the FBI’s WMD directorate has had static staffing levels for the past 17 years. Aligning to the national strategic shift to GPC may compromise efforts to counter chemical terrorism in this agency. Regardless, the national strategies have evolved significantly; new budgets should follow suit.

RECOMMENDATION 7-9: WMD budgets should be aligned with evolving strategic priorities.

Strategies employing flexible funding, such as the State Department’s Nonproliferation and Disarmament Fund (NDF), enable prompt, effective responses that build on activities across the USG and in cooperation with the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) and allies.

NDF was created to enable the USG to respond quickly to “high-priority nonproliferation and disarmament opportunities.” Many USG programs have geographic, budgetary, or political restrictions on their authorities. As explained on the NDF website:

NDF funds are “no-year” (funds need not be expended in the fiscal year in which they are appropriated) to permit maximum flexibility in project execution and may be made available “notwithstanding any other provision of law.”

NDF is a relatively small program (approximately $20 million per year vs. several hundred million dollars per year for cooperative threat reduction programs at the Departments of Defense and State) that has, because of its notwithstanding authority, supported an array of efforts from removal and destruction of the last of Libya’s legacy chemical weapons program to removal of highly enriched uranium from a civilian facility in Serbia. Starting around 2017, there was an interagency agreement to apply these funds more flexibly to fill gaps where other programs lacked authority or funds to address threats before they became acute.

Despite the fact that many of the recommendations made in this report would not require a significant increase to the budget appropriation or authorization, the federal budget process presents significant barriers to effective transitioning of promising research and development (R&D). According to “U.S. Federal Scientific Research and Development: Budget Overview and Outlook,” Federal funding for science and technology (S&T) is complicated by the U.S. budget process and the highly decentralized organization of federal R&D activities. The lack of a central mechanism to coordinate federal R&D programs leads to lengthy negotiations and decision-making among agencies, congressional committees (oversight and appropriation committees), and the White House. Beyond these challenges, various developments impacting the overall domestic and international strategic environment—such as the shift to GPC—can further complicate the effective transitioning of promising R&D. In this regard, the report states:

Shifting priorities between presidential administrations, changes to the makeup and ideologies of Congress, and broader economic conditions in the United States at large have resulted in the inconsistent funding for R&D, especially for basic research, despite strong and consistent support from the American public (Evans et al., 2021).

The article also discusses the impact on S&T as a result of delayed approvals as well as abrupt changes in the budget. Delayed budget approvals severely disrupt agency operations as they must work under previous budget guidelines without knowing when or what the new fiscal budget will be. This uncertainty and possible budget disruption impacts the continuity of data collection, staffing, and the ability to start new projects and maintain large-scale facilities. An example of these challenges is evident in the Trump administration’s de-emphasis of basic R&D in favor of development (efforts to take very mature R&D and transition it to operations) and then the Biden administration’s reversal which proposed increases in all areas of R&D (basic, industrial, and development) as shown in Figure 7-4.

There are two high-level budget gaps among the strategies the committee evaluated. (1) Some of the newer U.S. strategies have shifted to a GPC-focus (NSS, NDS) and others have to a lesser extent (DHS). Resourcing differently focused strategies in a

SOURCE: AAAS, 2021.

hierarchy must be rationalized. (2) Detailed resourcing of new GPC-focused strategies has not yet occurred. The importance of aligning resourcing with strategy has been declared (NDS, 2022), but the rebalancing has not appeared in public budgets to date. As stated throughout this report, robust anti-terrorism efforts are still important but other efforts associated with GPC now have higher strategic priority.

RECOMMENDATION 7-10: Counter weapons of mass destruction (CWMDT) budgets should incentivize activities to transition promising research to operations.

As stated earlier in this chapter, chemical terrorism and broader terrorism are deemphasized but not ignored in the shift to GPC. The highest-level strategies (NSS, NDS) speak to both an urgency to adopt GPC as a priority and a willingness to accept risk from other threats when doing so. In this dynamic context of a strategic shift with at present undefined budgetary implications, it is difficult for the committee to make specific budget recommendations in dollar amounts. Instead, the committee recommends that chemical terrorism risk assessments (e.g., full risks, threats only, national-level, state-level, and others) be performed in the context of the latest strategies to align budget priorities with strategic priorities and most clearly understand where and why the United States is accepting risk. Table 7-1 shows the budget functions and resources the committee believes should be considered under budgetary constraints that may result from the national strategic shift to GPC. These factors include risk priorities that are expressed in budget requests.

TABLE 7-1 Recommended Budget Priorities Based on National Strategic Shift to Great Power Competition

| Budget Function or Resource | Benefit of Retention |

|---|---|

| Fund comprehensive risk assessments based on the priorities set forth in recent national security strategies. | Allows forward-thinking strategic planning and preparedness. Enables agility to focus on new priorities when national strategy evolves. Identifies alignment between funding emphasis and strategy. Identifies where risk is being accepted when alternate, more strategy-aligned, investments are made. |

| Maintain the IC capabilities and expertise specific to terrorist groups (VEOs and racially, ethically, and motivated violent extremists) and understand their motivations. | Ensures subject matter expertise in the terrorism threat space is retained. Allows for rapid identification of and adaptation to emerging threats. |

| Support basic scientific and social science research specifically related to countering chemical terrorism, (e.g., understanding social behavior related to emerging threats). | Retains a strong talent base to address future, perhaps unanticipated, chemical threats/substances and the motivations to use them. Threats change and without natural and social scientific research, it will be difficult to adapt to changes, or in some cases even understand that and/or why they have occurred. |

| Strengthen insider threat programs related to physical, cyberphysical, and cybersecurity across the chemical industry. | Secures physical facilities from being subverted to cause toxic releases or the theft of precursor chemicals. Protects vulnerable information systems from being used in espionage and chemical attacks. |

| Support training and exercises to advance international chemical security priorities through continued initiatives with, for example, the OPCW, Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI) partners, North Atlantic Treaty Association (NATO) allies, nongovernmental organizations, and other international stakeholders. | Increases capacity and tactical readiness internationally thereby decreasing global threat and decreasing reliance on U.S. assets to respond. |

| Fund initiatives that work with international partners to enhance chemical security and identify, prevent/counter, and respond to chemical threats worldwide. | Strengthens alliances and builds stronger communication networks among relevant international agencies. |

| Continue emphasizing programs employing threat-agnostic approaches to identify and respond to chemical attacks. | Enables more economical, efficient, and effective responses, especially in times when chemical terrorism, or other national security concerns, may be deemphasized. |

| Encourage more flexible capability portfolio management models and processes that reduce bureaucratic constraints to accelerate the adoption of emerging technologies. Utilize innovation like the cross-functional team program management approaches model. | Enables the flexibility to most promptly address evolving threats and to more effectively facilitate innovation adoption and integration. (Esper and Lee James, 2023) |

FINDING 7-11: The material reviewed by the committee showed insufficient detail to allow a robust assessment of budgets likely to be required to implement strategies effectively, particularly for offices whose missions cover both chemical and biological threats.

CONCLUSION 7-11: Revised risk assessments are needed to reprioritize risks guided by recently issued strategies so that strategy-aligned budgets can be created. To ensure a balance among efforts initiated by revised assessments, a distinction between countering-chemical and countering-biological efforts is needed.

7.9 SUMMARY

The shift in the highest-level strategies of the United States from focusing on VEOs to GPC will impact efforts against chemical terrorism. While changes in funding priorities and operational adjustments are anticipated, the specific mechanism, magnitude, and timing are currently less understood. For example, sudden changes without thoughtful preservation of functions may hinder tactical readiness against chemical terrorist threats. Federal agencies should prioritize broadly applicable approaches to all areas of the CWMDT enterprise to maximize the USG capacity for appropriate response. Strategy documents that included detailed implementation plans for inter- and intra-agency coordination enhanced communication across relevant areas of identification, prevention, countering, and responding to chemical threats. However, communication challenges may still arise between state and local LE during emergencies due to classification issues related to chemical terrorism events.

The committee also cautioned the IC and relevant departments (DHS, DoD, DOJ) to avoid supporting counterchemical weapons programs that are technologically deterministic. Instead, the committee highlighted the need to address gaps in knowledge and approaches, such as involving social scientists with regional perspectives. A recommendation that DHS develop an updated chemical defense strategy that considers the implications of the GPC shift on reducing the risk of chemical threats and terrorism was made. Similarly, the committee observed that DoD’s counterterrorism programs would adapt better to the shifting national-level priorities if the department closely monitors terrorism risks. In practice, DoD would conduct risk and threat assessments to understand how best to direct the limited resources. Through their assessment, the committee emphasized that the revised risk assessments are needed to reprioritize risks and create CWMDT strategy-aligned budgets. These budgets should incentivize activities to transition promising research to operations. A distinction between countering-chemical and countering-biological efforts is necessary to balance different efforts resulting from risk assessments. Regardless of any agency defining toxins as falling under chemical or biological, toxins should be included as a threat. Finally, the committee emphasizes the importance of ensuring the continuity of authorization, in particular CFATS, abilities of critical programs, which are essential in safeguarding the nation from chemical terrorism activities.

REFERENCES

AAAS (American Association for the Advancement of Sciences). 2021. Interactive Dashboards. https://www.aaas.org/programs/r-d-budget-and-policy/interactive-dashboards-0.

ACC (American Chemistry Council). 2023. ACC Statement Regarding Expiration of Essential Chemical Security Program Key to Combating Terrorism. https://www.americanchemistry.com/chemistry-in-america/news-trends/press-release/2023/acc-statement-regarding-expiration-of-essential-chemical-security-program-key-to-combating-terrorism

BARDA (Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority). n.d. Medical Countermeasures Count —They Work to Safeguard Us. https://medicalcountermeasures.gov/barda/cbrn#portfolio.

CBDP (Chemical and Biological Defense Program). 2022. Approach for Research, Development, and Acquisition of Medical Countermeasures and Test Products. https://media.defense.gov/2023/Jan/10/2003142624/-1/-1/0/approach-rda-mcm-test-products.pdf.

CISA (Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency). 2023. Chemical Facility Anti-Terrorism Standards. https://www.cisa.gov/resources-tools/programs/chemical-facility-anti-terrorism-standards-cfats.

Department of State. Office of the Nonproliferation and Disarmament Fund. N.d. https://www.state.gov/bureaus-offices/under-secretary-for-arms-control-and-international-security-affairs/bureau-of-international-security-and-nonproliferation/office-of-the-nonproliferation-and-disarmament-fund/

DHS (Department of Homeland Security). n.d. Preventing Terrorism Overview. https://www.dhs.gov/preventing-terrorism-overview.

DHS. 2021. The DHS Strategic Plan to Counter the Threat Posed by The People’s Republic of China. https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/21_0112_plcy_dhs-china-sap.pdf.

DHS. 2022. Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear Defense Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation Strategy: Fiscal Years 2021-2025. https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/2022-03/22_0316_st_cbrn_rdt%26e_strategy_fy21-25.pdf.

DHS. 2023. The Third Quadrennial Homeland Security Review. https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/2023-04/23_0420_plcy_2023-qhsr.pdf.

DOD. 2022. National Defense Strategy. https://www.defense.gov/National-Defense-Strategy/ Risk Management Section.

DOD. 2007, Transformational Medical Technologies Initiative (TMTI). Fiscal Year 2007 (FY 2007) Congressional Report. https://biosecurity.fas.org/resource/documents/dod_2007_transformational_medical_technologies_initiative.pdf

Esper, M., and D. Lee J. 2023. Want More Pentagon Innovation? Try This Experiment.

Evans, K. M., K. R. W. Matthews, G. Hazan, and S. Kamepalli. 2021. U.S. Federal Scientific Research and Development: Budget Overview and Outlook. Rice University Baker Institute for Public Policy. https://www.bakerinstitute.org/research/us-federal-scientific-research-and-development-budget-overview-and-outlook.

FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency). 2016. National Prevention Framework. Retrieved from https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-04/National_Prevention_Framework2nd-june2016.pdf.

SWIFT (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication). n.d. Know Your Customer. https://www.swift.com/your-needs/financial-crime-cyber-security/know-your-customer-kyc.

Treasury (U.S. Department of Treasury). 2022. National Strategy for Combating Terrorist and Other Illicit Financing. https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/2022-National-Strategy-for-Combating-Terrorist-and-Other-Illicit-Financing.pdf.

This page intentionally left blank.