Chemical Terrorism: Assessment of U.S. Strategies in the Era of Great Power Competition (2024)

Chapter: 2 Chemical Threats and U.S. Governmental and Nongovernmental Institutions That Play a Role (The Threat and the Who's Who)

2

Chemical Threats and U.S. Governmental and Nongovernmental Institutions That Play a Role

(The Threat and the Who’s Who)

The following sections provide a broad overview of the chemical threat landscape, including social considerations, range of baseline threats, and their characterizations. Brief descriptions of chemical agent delivery methods are also provided. Later, a discussion around emerging technologies and their role in the threat landscape as well as key actors involved in this space is presented. The intent of chapter 2 is to lay out the different considerations involved in assessing this complex setting. If the reader prefers to omit this preliminary information, they should proceed directly to chapter 3, to learn about the assessment methodology applied in this study.

2.1 COMPLEX CHEMICAL THREAT LANDSCAPE

Terrorism involving chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear (CBRN) agents has been extremely rare within the annals of nonstate terrorism overall (START, 2022). However, chemical terrorism has been the most common—and successful in terms of casualties caused—form of CBRN terrorism to date. According to the Profiles of Incidents involving CBRN and Nonstate Actors (POICN) Database (Binder and Ackerman, 2019), terrorist interest in, pursuit, and use of chemical weapons constitutes ~ 76 percent of all CBRN terrorism, with ~ 400 incidents of ideologically motivated actors (Binder et al., 2017)1 pursuing chemical weapons (agent + delivery system) recorded between 1990–2020.2 Approximately 50 percent of these incidents have resulted in the actual use of an agent (Binder and Ackerman, 2020) and at least half of the 400 incidents involv-

___________________

1 POICN does not capture purely criminal uses with no ideological component, but there are estimated to be even more of these, such as poisonings of business rivals.

2 There were 11 additional cases of adversary interest in CW that did not reach the level of a defined plot, but indicated actions that might lay the groundwork for an actual plot. Examples of such “protoplots” include discovery of a chemical weapons manual or hiring a scientist with a weapons’ specialty (definition of a protoplot in Binder et. al. (2017) POICN Database Codebook Version 8.71 [National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism: College Park, Maryland]).

ing chemical agents have been assessed as being of interest to those concerned about mass-casualty terrorism.3 An analysis of the Global Terrorism Database, which covers a longer timespan than POICN (1970–2015) but only includes actual uses of chemical agents, counts 292 chemical terrorism incidents (Santos et. al., 2019).

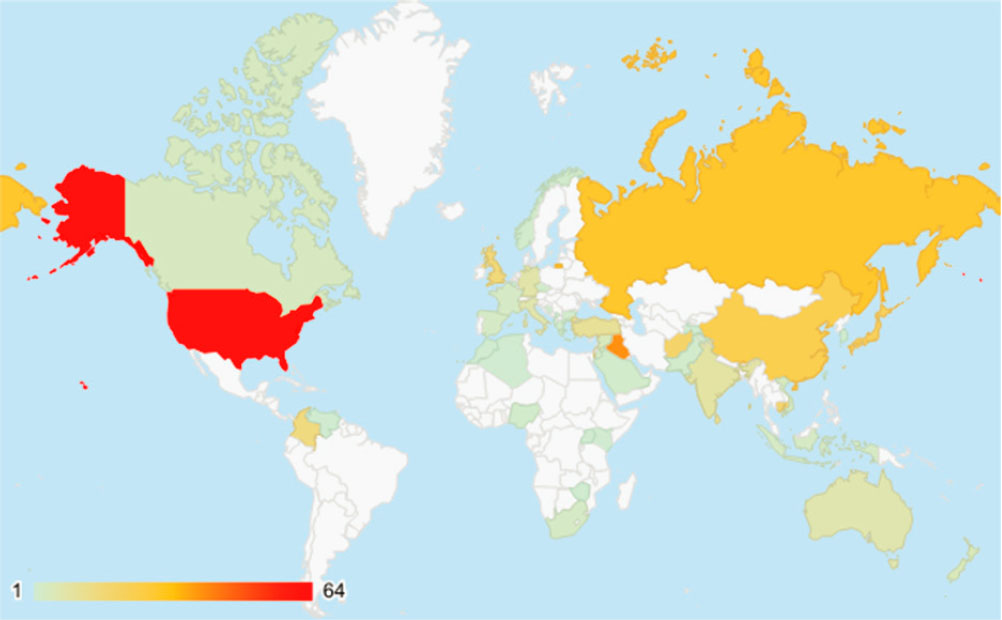

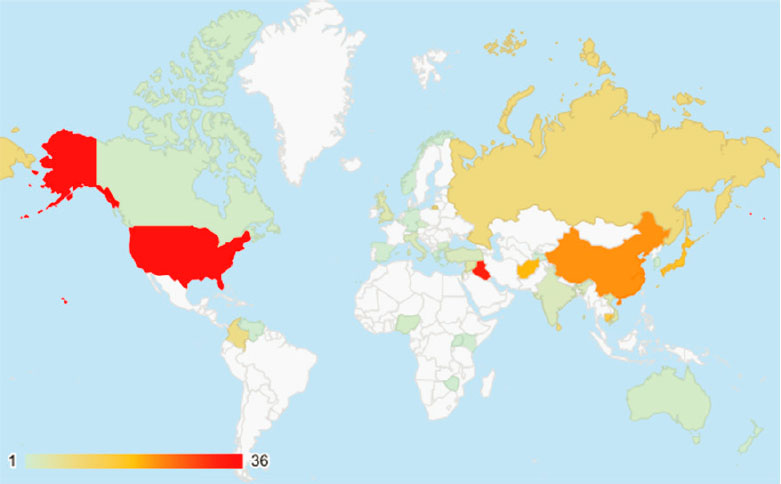

These incidents of chemical terrorism and attempted terrorism have involved 100 different perpetrators motivated by different ideologies. For the period between 1990 and 2020, the geographic distribution of countries where chemical terrorism incidents have occurred is extensive (see Figure 2-1). This includes 68 cases in the United States, with 36 uses of a chemical agent by perpetrators in the United States. Chemical terrorism has also utilized an array of chemical agents, encompassing many commonly available (often referred to as “low-end”) agents and several toxic industrial chemicals (TICs) and toxic industrial materials (TIMs), but also including some chemical agents that have traditionally been developed in the military context (see Table 2-1).

Specific mention of the threat from TICs and TIMs is warranted, since these agents have historically accounted for a large fraction of terrorist incidents that involve chemicals. According to the POICN Database (see Table 2-1), at least 90 of the roughly 200 uses of chemical agents by terrorists involved TICs or TIMS, whereas in the data-

SOURCE: POICN Database (Binder and Ackerman, 2020).

___________________

3 These are events which the POICN Database coded as “Heightened Interest,” which denotes involvement of at least five total casualties, a CBRN agent classed as a warfare agent, fissile materials, or having at least moderately sophisticated agent weaponization (Binder et. al., 2017).

set developed by Santos and colleagues (2019), the category of “corrosives,” which includes chlorine, was listed as the most commonly used chemical agent in an attack, and cyanide compounds were also used frequently. They also found that the lethality of chemical attacks using TICs was significantly lower compared to the lethality of attacks using nerve agents. However, the ubiquity and large volumes of TICs/TIMs mean that the scope for possible harm is substantial. It has been estimated that in the United States, there were 123 facilities that possessed sufficient quantities of TICs/TIMs capable of killing one million or more people (Kosal, 2006).

Additionally, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) reported that facilities storing or manufacturing hazardous chemicals could be targeted by terrorists; the salient example cited is the use of chlorine in Syria in 2018 (GAO, 2020). This warning was reiterated by scholars from the Center for the Study of Weapons of Mass Destruction at National Intelligence University (NIU) who noted that over 90 percent of the chemical weapon attacks in the Syrian civil war involved TICs, principally chlorine (Caves and Carus, 2021). Historically, other works have substantiated the risk. A 2006 Congressio-

TABLE 2-1 Agents Involved in Chemical Terrorism Incidentsa

| Chemical | Primary Use | # of Incidents of Interest, Pursuit or Use | # of Incidents of Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Cyanide | TIC | 47 | 14 |

| Chlorine | Military / TIC | 41 | 27 |

| Butyric Acid | IC | 24 | 24 |

| Sodium Cyanide | TIC | 23 | 2 |

| Sarin | Military | 20 | 4 |

| Mustard Agent | Military | 15 | 6 |

| Potassium Cyanide | TIC | 14 | 2 |

| VX | Military | 14 | 9 |

| Ammonia Compounds | TIC | 10 | 7 |

| Unspecified Cyanide Salt | TIC | 10 | 1 |

| Arsenic | TIC | 8 | 3 |

| Hydrochloric Acid | TIC | 6 | 1 |

| Lachrymatory Acid/Pepper Spray/Mace | LE | 6 | 5 |

| CS Gas | LE | 5 | 4 |

| Nitric Acid | TIC | 5 | 0 |

| Sulfuric Acid | TIC | 5 | 1 |

a Primary use listed include toxic industrial chemicals (TIC), military, law enforcement (LE), and industrial chemical (IC).

NOTES: Others (Use Cases Bolded): mercury, strychnine, mercuric chloride, nicotine sulfate, sodium hydroxide, acetone, benzene, dimethyl sulfoxide, halothane, hydrogen fluoride, malathion, methanol, phosgene, sodium hypochlorite, sodium monofluoroacetate, phosphine (PH3), aldrin, atropine, brodifacoum, BZ, carbofuran, chloroform, chlorophenyl silatrane, chloropicrin, digoxin, diisopropyl fluorophosphate, Drano, endrin, hydrazine, ketamine, lewisite, methomyl, methylene blue, paraquat, pheniprazine chloride, phenol, sodium chlorate, sulfur, tabun, tellurium, tetraethylammonium bromide (TEAB), vinegar, warfarin, cyanic acid, vinyl trichlorosilane, hydrogen sulfide, sodium chlorate.

SOURCE: POICN Database (Binder and Ackerman, 2020).

nal Research Service report presented on the threat posed by terrorists opportunistically employing TICs and TIMs in a chemical attack (CRS, 2006), noting specifically that chemical facilities might be targets of opportunity for terrorists to release chemicals into communities. The report also suggested that this risk was increasing, with the possibility of severe consequences on human health and the environment. Casillas and colleagues assessed that the availability or access to TICs/TIMs makes their use in terrorist activities more likely because they are not tightly controlled like chemical warfare agents (Casillas et al., 2021). The 2018 National Strategy for Countering WMD and Terrorism (GovInfo, 2018) also mentions the use of TICs as an active threat, and it recommends tightened security practices for academic and industrial sectors.

For the past forty years, 21 reported attacks directed toward chemical facilities have been identified with seven incidents of terrorism directed at individuals. (Kosal, 2007). While this is a small number compared to general attacks, a large magnitude of casualties could occur following a well-organized attack on chemical-based facilities.

While the number of chemical terrorism incidents has risen and fallen over time, there is no empirical or analytical indication that the threat is disappearing (see Figure 2-2), especially with several incidents within the past two decades of terrorists using or pursuing various chemical agents, including those classed as warfare agents.

To obtain a better understanding of the baseline chemical terrorism threat presented above, it is necessary to parse the threat into the two basic components of motivation (incentives and disincentives) and capability.

2.1.1 Incentives and Disincentives for Using a Chemical Agent or Weapon

While a complete treatment of terrorist CBRN motivations is beyond the scope of this assessment, the reasons why some terrorists and not others pursue chemical weapons are essential to explore in at least some depth. At the outset, it is worth noting that to arrive at the decision to pursue a chemical weapon, in most cases a terrorist needs to make several specific choices (even if these are done implicitly). Taking a terrorist actor’s general desire to employ some weapon or violent tactic to achieve its goals as a starting point, the first

SOURCE: POICN Database (Binder and Ackerman, 2020).

choice is whether to use “conventional” terrorist modalities like guns and explosives or to innovate by using a novel or unconventional attack method. In only a relatively small proportion of circumstances will a terrorist actor seek to innovate in any way (Cameron, 1999; Dolnik, 2007; Hoffman, 1992; Jenkins, 1986), in which case they may decide to pursue a novel tactic combined with a conventional weapon (such as flying an airplane into a building as on September 11, 2001), new organizational approaches, or to pursue an unconventional weapon. For the subset of actors seeking to pursue an unconventional weapon, the choice is often between a chemical weapon and other types of unconventional weapon (e.g., biological, electromagnetic, or radiological). It is important to recognize that at each of these stages incentives and disincentives, opportunities, and obstacles exist. These factors are considered by the terrorist decision-maker, with only a relatively limited subset of pathways leading to the final decision to pursue a chemical weapon.

Incentives that may attract terrorists to unconventional weapons in general, including chemical weapons, followed by examples:

- Strategic or Operational Advantages—causing massive numbers of casualties through punishment or revenge; exerting a disproportionate psychological impact on the target society; gaining extensive publicity; deterrence; provoking government backlash; or forcing increased spending on defenses.

- Tactical Advantages—conducting a covert attack and achieving area contamination.

- Organizational Benefits—building status to assist in leadership struggles or intergroup rivalries and diversifying the weapons portfolio.

- Ideology—emulating sacred texts or myths; “techno-fetishism”; apocalyptic purification through sacrificial acts (Lifton, 2007).

Disincentives that could explain the relative rarity of unconventional weapon attacks by terrorists include the following with examples:

- Status quo inertia—unconventional weapons are usually neither necessary nor appropriate for achieving the terrorist’s goals; risk aversion and lack of innovativeness; perception that developing a CBRN capability is too difficult or creates too much of an opportunity cost; the terrorist’s operational tempo, strategic time horizon, and sense of urgency preclude the development of a complex weapons capability.

- Negative consequences—fear of reprisal by the targeted parties or the international community from the use of a banned weapon; concern about the loss of constituency support from the use of “morally illegitimate” weapons.

- Ideological proscription—where the effects of the unconventional weapon are anathema to the actor’s ideology for a variety of reasons.

- Fear of self-harm—concern regarding the safety hazards of working with many unconventional weapons agents and precursors.

Terrorist actors for whom one or more of the above incentives operate strongly and for whom the disincentives are less salient are most likely to select unconventional over

conventional weapons. Within this relatively small subset of actors, there are a few factors that would push a terrorist particularly toward chemical weapons as opposed to other unconventional weapons. Chief among these is the perception that chemical weapons are easier to acquire and deploy than other weapon types, while still satisfying the terrorist’s strategic, operational, tactical, or organizational objectives. Two attributes that are often associated with a greater likelihood of unconventional weapon selection are a) having a religious ideology, since a “divine imprimatur” provides a basis for overcoming the ethical and social barriers to using these weapons, and b) cult-like organizations with charismatic leaders (see Bale, 2017; Bale and Ackerman, 2009). While quantitative studies have yielded mixed results for the relevance of these factors, they do appear to feature prominently in the chemical weapons attacks with the highest numbers of casualties.

Beyond general CBRN selection, other factors that could influence the pursuit of chemical weapons are shown in Table 2-2. The information in the table draws primarily from a previous study on the psychology of chemical and biological nonstate adversaries. (Ackerman et. al. 2017a; Binder et. al. 2017).

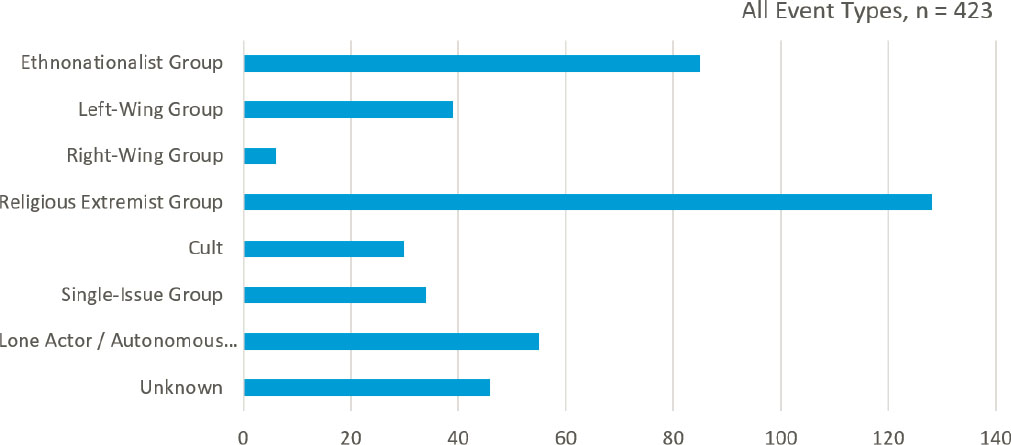

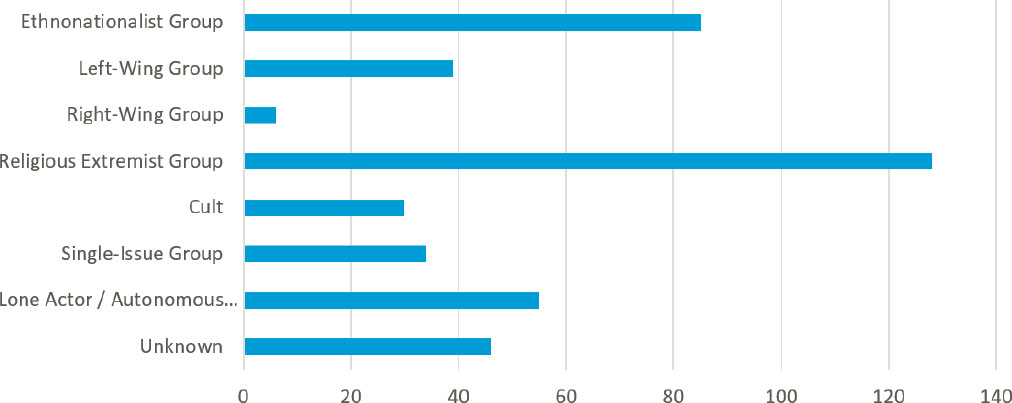

The above discussion provides context for understanding the empirical record of those who have pursued or used chemical weapons. Figures 2-3 and 2-4 show, respectively, the perpetrator type (e.g., religious extremist groups, ethnonationalist groups, political groups, and others) and the general motivations behind recorded cases of chemical weapons pursuit by terrorists. Additionally, Table 2-3 enumerates the types of entities involved. Furthermore, Tables 2-4, 2-5, and 2-6 provide lists of formal terrorist groups who have pursued a chemical weapons capability most prolifically.

TABLE 2-2 Factors Influencing Chemicals Relative to Other Unconventional Weapons

| Factor | Influence on Chemical Weapons Selection |

|---|---|

| Perceived availability of chemical agents or precursors (including stored chemicals) relative to other weapon types | + + |

| Leadership or operational cadre have a background in chemistry or the chemical industry | + |

| Proclivities (e.g., fetish) by leaders or operational commanders specifically toward chemicals | +++ |

| Ideological drivers specifically involving CW | +++ |

| Perceived prior use of CW against actors or constituents (revenge motive) | +++ |

| Ideological proscription of chemical weapons or the effects thereof | - |

| Constituency intolerance of chemical weapons or the effects thereofa | - - |

| Rejection of modern technology | - |

| Leadership aversion to chemicals or safety concerns | - |

a Merely having a constituency is not sufficient to dissuade a terrorist from selecting chemical weapons, as seen by the many ethnonationalists and other secular groups with constituencies who have pursued chemical weapons (see Figure 2-3).

NOTES: The symbols reflect a rough order-of-magnitude estimate of the degree to which each factor influences chemical weapons selection, with a (+) indicating a positive influence on the decision to select chemical weapons out of CBRN, a (-) indicating a negative influence and the number of symbols indicating the relative magnitude of the influence (low, moderate, or strong)

SOURCE: POICN Database (Binder and Ackerman, 2020).

SOURCE: POICN Database (Binder and Ackerman, 2020).

TABLE 2-3 Number of Different Perpetrator Entities

| Entity Type | All Incidents [% of Known Perpetrators] | Heightened Interest Incidents Only [% of Known Perpetrators] | Use Cases Only [% of Known Perpetrators] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formal / Identified Organizations | 78 [58%] | 38 [59%] | 28 [67%] |

| Unnamed / Unaffiliated Cells | 18 [13%] | 10 [16%] | 6 [19%] |

| Individuals | 38 [28%] | 16 [25%] | 8 [14%] |

| Incidents Where Perpetrator(s) Were | 76 | 29 | 58 |

| Unknown |

SOURCE: POICN Database (Binder and Ackerman, 2020).

TABLE 2-4 Most Prolific Formal Terrorist Organization Perpetrators (All Chemical Incidents)

| Group Name | Number of Incidents |

|---|---|

| ISIS | 43 |

| Aum Shinrikyo | 28 |

| Chechen Rebels | 28 |

| East Turkistan Liberation Organization (ETLO) | 21 |

| Khmer Rouge | 18 |

| Taliban | 18 |

| al-Qa’ida | 16 |

| Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) | 11 |

| Hamas | 9 |

| Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) | 9 |

| Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK) | 6 |

| Animal Liberation Front (ALF) | 5 |

SOURCE: POICN Database (Binder and Ackerman, 2020).

TABLE 2-5 Most Prolific Formal Terrorist Organization Perpetrators: Heightened Interest Chemical Incidents Only

| Group Name | Number of Incidents |

|---|---|

| ISIS | 38 |

| Aum Shinrikyo | 21 |

| Chechen Rebels | 16 |

| Taliban | 16 |

| al-Qa’ida | 13 |

| East Turkistan Liberation Organization (ETLO) | 5 |

| Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) | 5 |

| Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) | 4 |

| al-Qa’ida Organization in the Islamic Maghreb | 3 |

| Khmer Rouge | 3 |

| National Liberation Army (Colombia) (ELN) | 3 |

SOURCE: POICN Database (Binder and Ackerman, 2020).

TABLE 2-6 Most Prolific Formal Terrorist Organization Perpetrators: Uses

| Group Name | Number of Incidents |

|---|---|

| ISIS | 31 |

| East Turkistan Liberation Organization (ETLO) | 21 |

| Taliban | 17 |

| Aum Shinrikyo | 16 |

| Khmer Rouge | 15 |

| Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) | 8 |

| Chechen Rebels | 7 |

| Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) | 6 |

| Animal Liberation Front (ALF) | 2 |

SOURCE: POICN Database (Binder and Ackerman, 2020).

Many of the same incentives or disincentives for selecting chemical weapons may apply to nonideological violent nonstate actors (e.g., not strictly terrorists) who are not reflected in the above data. However, external belief systems that can either prompt or constrain weapon selection do not exist for these groups. The goals of nonideological violent nonstate actors are likely to be more personal (Ackerman et. al., 2017a), such as holding a grudge against a particular individual, seeking financial gain, or having psychotic delusions directing them to cause harm. In many of these idiosyncratic cases, understanding and detecting these behaviors, including weapon selection, will be more challenging. It is interesting to note that, unlike ideologically driven nonstate actors, when both terrorist and nonterrorist perpetrators are taken into account ~ 55 percent were lone actors (Ackerman and Binder, 2017b).

2.1.2 Demographic of Perpetrator and Capability

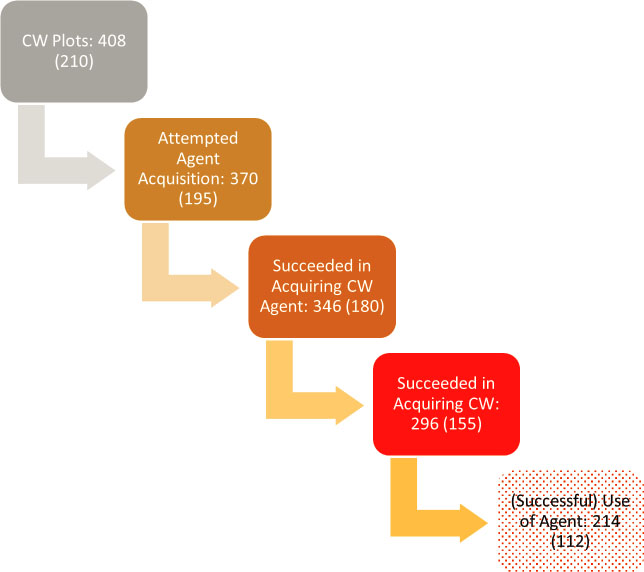

While motivation can be a powerful driving force that can in turn spur the development of a chemical weapon capability, it does not guarantee the acquisition of a viable chemical weapon. Figure 2-5 below depicts the filtering process between an intent to utilize CW and the actual capability to do so, including for heightened interest events. Protoplots (see footnote 2) are excluded, as they do not represent a clear intent to acquire a CW. It is salient to note that the majority of perpetrators, whether working singly or as part of a team, were able to acquire a chemical agent and create a weapon of some sort.

It is essential to understand the spectrum of means that may be employed by terrorists to deliver the chemical agent where it would result in maximum harm so that it can be incorporated into the strategy for prevention and deterrence.

SOURCE: POICN Database (Binder and Ackerman, 2020).

A large-scale delivery of a chemical agent, in terms of quantity, is a much greater challenge for a terrorist organization in comparison to the delivery of a smaller quantity. Although it is easier to execute, the smaller-scale delivery may have a smaller impact in terms of creating harm or yielding limited results. Factors such as weather patterns, chemical stability and volatility, and unintentional poisonings influence the success of the delivery.

Aum Shinrikyo (see Appendix E for case study) provides an illustration of the difficulty that a terrorist organization would encounter in attempting to deliver toxic agents on a large scale. Their primary sarin attack on the Tokyo subway utilized the vapor pressure of sarin and nothing else (Tucker, 2006). The terrorists’ perforated polyethylene bags containing sarin in the Tokyo subway, exited the subway and relied on the sarin to volatilize on its own. The dispersal method was crude and was not particularly efficient; nevertheless, the release caused 12 fatalities, 54 victims in serious or critical condition, and more than a thousand victims with mild symptoms. If a more sophisticated dispersal method had been used, a significantly larger number of casualties could have resulted. The Aum sarin attack showed that even a well-funded organization that had acquired significant synthetic ability capable of producing sophisticated nerve agents may not necessarily possess sophisticated dispersal technology.

Furthermore, volatile—or to a lesser degree semi-volatile TICs—are a means for an opportunistic chemical warfare agent (CWA) attack by a terrorist organization. Initial utilization of CWA involved the release of chlorine from pressurized steel cylinders during WWI. The approach had the drawback of relying on wind direction and speed to transport the chlorine to enemy lines. However, a terrorist organization might not be as concerned about wind direction since there is less discrimination about who would be exposed. The disaster at Bhopal is an example of the casualties and damage that could be caused by this type of terrorist attack (see Chapter 5 for further details). The release of methyl isocyanate caused >3,700 deaths and injured perhaps another 20,000.

To examine capability factors a little more closely, we can draw on the Chemical and Biological Weapons NonState Adversary Database (CABNSAD, Ackerman and Binder, 2017b), which focuses on the perpetrators themselves and includes both terrorist and nonterrorist violent nonstate actors.4 The database contains information on 398 individuals involved with chemical weapons incidents of one type or another, with at least 110 incidents perpetrated by non-terrorist actors beyond the 423 incidents recorded in the POICN Database.

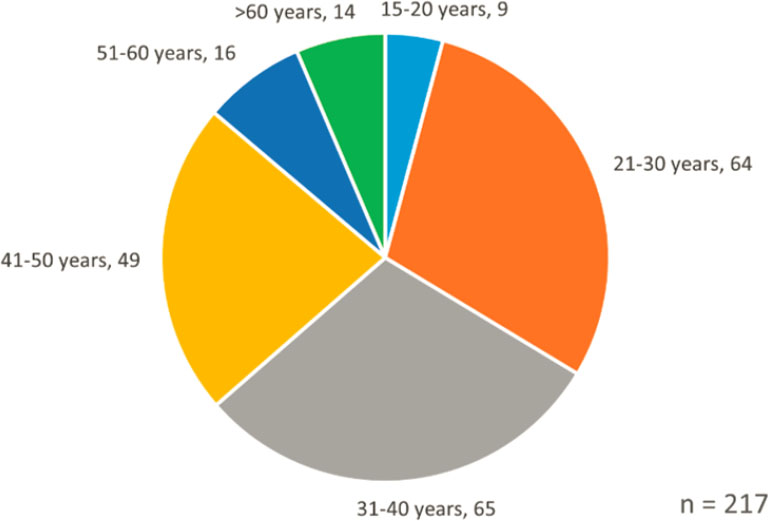

With respect to age, the range is 15–70 years old, with a mean age of ~ 37 years and a median age of 34 years. Figure 2-6 breaks down the 217 perpetrators for whom age data is available.

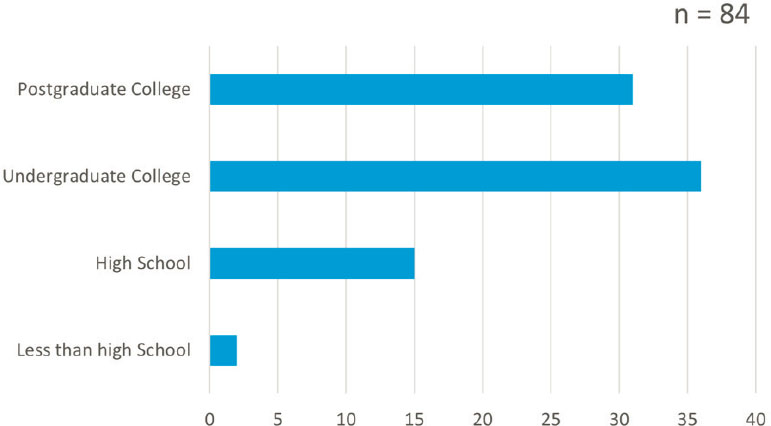

With respect to the highest level of education reached—this information was only available for 84 perpetrators (see Figure 2-7 and Table 2-7). The known disciplinary background of the perpetrators is also shown.

___________________

4 The CABNSAD Database comes in two forms, one in which each perpetrator is analyzed individually (even if they were in the same group or cell), and one in which perpetrators within the same organization are aggregated. For the purposes of this section, the nonaggregate version is utilized, since individual-level demographics are presented.

SOURCE: CABNSAD Database (Ackerman and Binder 2017b).

SOURCE: CABNSAD Database (Ackerman and Binder 2017b).

TABLE 2-7 Educational Discipline of Perpetrators

| Discipline | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Chemistry and Related Disciplines (incl. Pharmacology) | 9 |

| Other Natural Sciences | 10 |

| Other STEM (including Engineering) | 10 |

| Social Sciences and Humanities | 11 |

| Business/Economics | 4 |

| Medicine and Related Disciplines | 14 |

NOTE: Where known; n = 58.

SOURCE: CABNSAD Database (Ackerman and Binder, 2017b).

The perpetrator study cited above (Ackerman and Binder, 2017b) derived several quantitative results from the CABNSAD database. While the CABNSAD Database includes perpetrators of both chemical and biological events, the majority of perpetrators in the database pursued chemical weapons. (Only 87 of 486, or ~ 18 percent solely pursued biological weapons.) Additional analyses would need to be conducted to confirm that the following findings apply to chemical perpetrators in particular; it is suspected that many of them will hold for the more limited dataset of chemical perpetrators. The following observations were made based on the combined chemical and biological perpetrator data:

- The majority of individual perpetrators (e.g., not part of a group or cell) reached at least an undergraduate level of education.

- Far more (nonfatal) injuries occurred when the perpetrator had a college education.

- The higher the level of education of the perpetrator, the more likely the perpetrator would successfully use chemical and/or biological agents.

- Successful perpetrators were more likely to be older and involved with chemical and/or biological agents for a longer period of time in comparison to the younger perpetrators.

- Unlike the case with terrorist groups, the majority of perpetrators, overall, targeted food or drink with their chemical and/or biological agents.

2.1.3 Wide-Ranging Baseline Threat

Terrorists employing chemical agents have caused a greater amount of harm than those using any other type of unconventional weapon. They have killed at least 150 people (and possibly over 900) and injured at least 2,400 (up to approximately 6,600) between 1990 and 2020 (POICN Database, Binder and Ackerman, 2020).5 Nonideologi-

___________________

5 There are several attacks, such as one by the Khmer Rouge in 1996 that reportedly killed 200 and wounded 300, which carry some doubt as to their veracity, whereas several other attacks might be viewed more as

cal perpetrators have also killed at least 230 people and injured at least 1,840 over the same period (CABNSAD Ackerman and Binder, 2017b).

Yet, most incidents have resulted in no casualties: ~ 80 percent of chemical perpetrators did not cause any fatalities and ~ 70 percent did not cause any nonfatal injuries. Indeed, the POICN Database could only confirm that attacks with chemical agents were responsible for any fatalities in ~ 12 percent of all terrorist use events and for injuries in only ~ 40 percent of terrorist use events. A handful of perpetrators (fewer than a dozen) have thus been responsible for the majority of casualties and fatalities.

With respect to terrorism, the sarin nerve agent attacks carried out by the Japanese Aum Shinrikyo cult in the mid-1990s (14 dead, 1,050 injured in total, see Gupta, 2015; Smithson and Levy, 2000) have been the most consequential in terms of casualties, and because they occurred almost without warning in the context of a peaceful civil society. More recently, the repeated use by the Islamic State (and its predecessors) of chlorine and mustard gas in Iraq has broadened the ambit of how terrorists might deploy chemical weapons. Aside from possibly the Islamic State (IS), the nonstate actors who have inflicted the greatest amount of lethal harm using chemical agents have been apocalyptic millenarian cults, in particular, the People’s Temple of Jim Jones which killed over 900 people (see BBC News) and the Movement for the Restoration of the Ten Commandments which killed over 20 (see Borzello, 2000). However, in these cases, the deployment took the form of poisoning their own members.

Thus, while jihadist groups like IS have recently demonstrated the highest threat potential for chemical terrorism, historically apocalyptic cults have caused the most casualties (usually to their own members). Moreover, there has been a wide range of ideologies and actors that have pursued attacks with chemical agents. Formal organizations may dominate the chemical terrorism landscape, but overall individuals are playing a larger role in this space. Chemical terrorism, at least at a nominal level, appears to be achievable by many violent actors, with over half of these plots having proceeded all the way to the use stage. Although the vast majority of attacks have involved lower-toxicity agents and crude delivery methods; both warfare agents and other high-toxicity chemicals, and sophisticated delivery mechanisms have been pursued and employed.

FINDING 2-1: The current threat landscape consists of multiple lower-consequence attacks, punctuated by the possibility of occasional large-scale, potentially mass-casualty events.

2.2 CHARACTERIZATION OF BROAD CHEMICAL THREATS

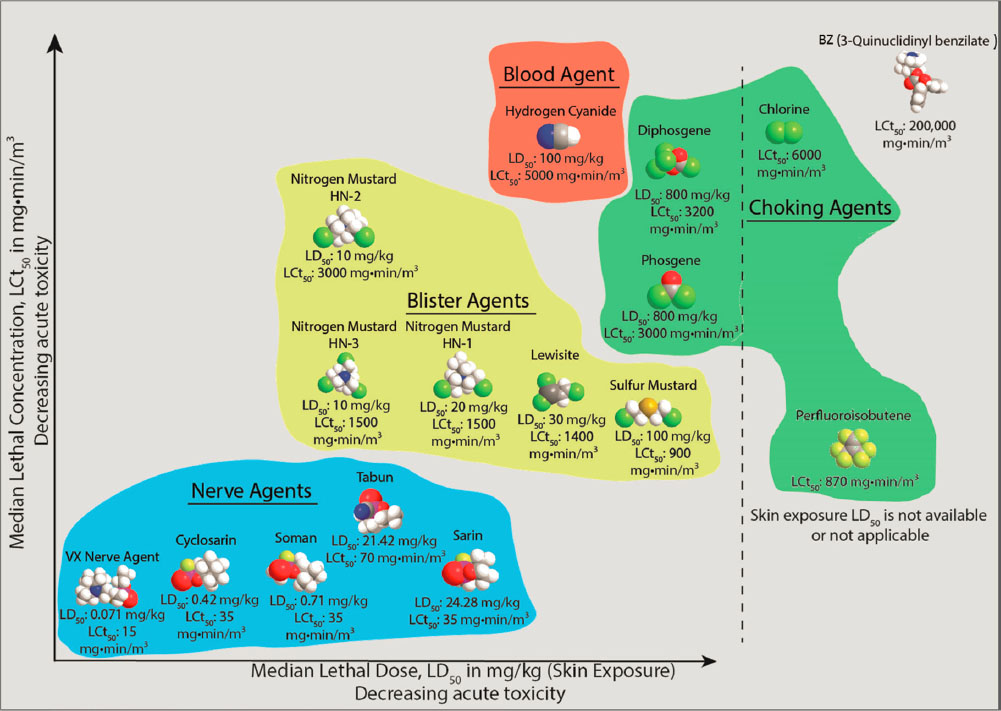

Chemical threat agents are highly hazardous or toxic chemicals that can be acquired or developed as weapons of mass destruction to promptly cause casualties.

___________________

insurgent attacks rather than terrorism proper. We have provided the most conservative estimate above as a lower bound, but these might significantly undercount the true number of casualties. These figures also do not include injuries from several more recent attacks which are still being assessed by POICN coders, so the true figures might be considerably higher.

The widespread availability of starting materials for millions of highly toxic compounds and instructional materials outlining how to produce them have reduced barriers to entry for the nefarious use of chemicals. Furthermore, with increased industrialization, other commercially available chemicals and materials with the potential to be used as weapons could be acquired and accessed by terrorist individuals and organizations to be used as improvised weapons. The list of known and potential chemical threat agents is vast and expanding (Figure 2-8).

To increase the likelihood of success in countering the continually expanding list of potential chemical threat agents, federal agencies are increasingly turning toward broadly extensible strategies and agent-agnostic approaches (further discussion can be found in section 7.6).

Over 100 billion chemicals exist in the theoretical “molecular universe” (Reymond, 2015). Over 200 million chemicals have been synthesized or isolated,6 and another is identified every 3–4 seconds (CAS, n.d.; Mulvaney, 2017). Technological advances such as synthetic biology and cheminformatics, additive manufacturing, nanotechnology, and microscale chemical reactors further facilitate the discovery of new and novel chemical threat agents7 available for potential beneficial or nefarious use.

Against this backdrop, one should consider the state of chemical weapons in context. In this regard, steady progress toward the elimination of declared chemical weapons stockpiles has also driven the research, development, and deployment of new capabilities to detect and respond to a broad range of classes of chemicals with known potential to be used as weapons. However, the norms against weaponizing chemicals enshrined within the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) are challenged through suspected states not abiding by their treaty commitments or remaining outside the treaty and uses of chemicals as weapons in ways not broadly anticipated at the time of treaty negotiation. In a globally connected world, the varying robustness and effectiveness of regulation is also a challenge. The U. S. Government (USG) faces a challenge to ensure readiness to prevent, counter, and respond to chemical threats, as the number and complexity of such threats are continually evolving and expanding. Meanwhile, regulatory agencies such as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), or the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) can take years to review the safety and toxicity profiles of a new chemical within the United States. Existing strategies and associated capabilities and infrastructure must be reexamined and potentially retooled to stay ahead of the threat.

___________________

6 Compendium of WHO and Other UN Guidance on Health and Environment. https://www.who.int/tools/compendium-on-health-and-environment/chemicals.

7 As stated in Chapter 1, chemical terrorism threats considered include agents identified as chemical weapons as well as existing, emerging, and potential agents of concern. Threat actors’ patterns of use were considered to identify trends and to understand the degree to which different methods impacted successful implementation of a given strategy.

SOURCE: Fischer et al., 2017.

2.3 DELIVERY METHODS OF CHEMICAL AGENTS

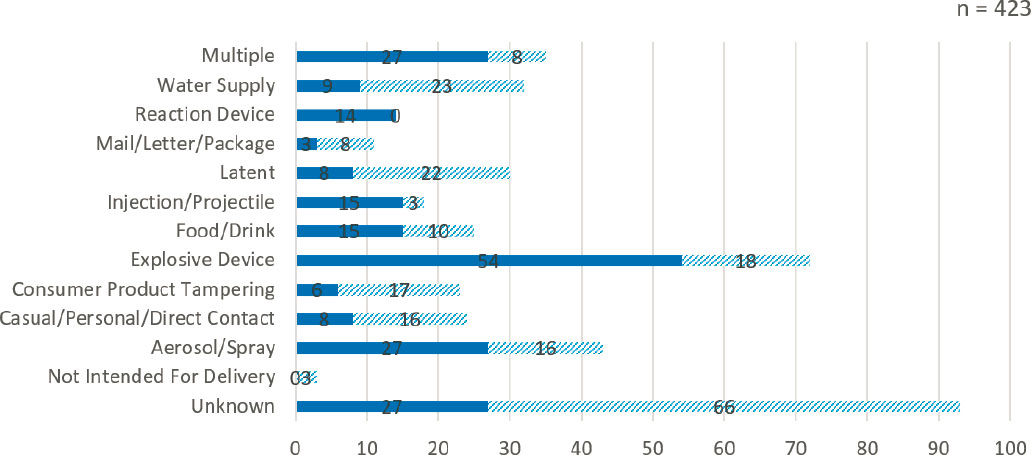

Between the period of 1990 and 2020, the incidents of chemical terrorism have included a variety of delivery methods, such as explosive devices, aerosol, and other methods (see Figure 2-9). This section describes the delivery methods that most concern chemical terrorism: passive release, aerosolizing devices, and contamination of food or water.

2.3.1 Aerosolizing Devices and Passive Release

If in the future aerosolization of acute stable toxic substances (chemical or biological) is deemed to be possible, then there is a cause for concern if large quantities can be rapidly dispersed. If the CWA has ideal physical and toxic properties (e.g., surfactant, acutely toxic, stability) to be aerosolized, and can be spread aerially in a manner similar to the application of forest fire suppressing foams over dense urban population centers, the impact could be catastrophic. The Tokyo subway release falls in the category of passive (see Aum Shinrikyo in Appendix E).

2.3.2 Contamination of Food or Water

The nature of this threat depends on the properties of the CWA to cause an immediate and widespread impact. A previous analysis of an accidental poisoning of livestock

SOURCE: POICN Database (Binder and Ackerman, 2020).

feed considered the food safety and security implications in the context of chemical terrorism (Kosal and Anderson, 2004). An example of a historical incident of intentional contamination of food comes from post-WWII Germany. In 1946, a group of Jewish Holocaust survivors poisoned the bread of Nazi S.S. officers in an American Prisoner of War (POW) camp (Tucker, 2006; The Guardian, 2016). An arsenic-containing material was used to poison black rye bread that was to be served to the detainees. More recent domestic cases include contamination of ground beef with a nicotine-based pesticide in a Southwest Michigan supermarket in December 2002 (Dasenbrock et al., 2005) and intentional contamination of coffee with arsenic after a church service in Maine (Dasenbrock et al., 2005).

Contamination of water, especially large municipal supplies (e.g., reservoirs) is beyond the capabilities of most terrorist groups due to dilution factors. The potential challenges at the point of distribution were illustrated by the widely reported cyber hacking incident of a water treatment facility in Florida. After investigating, the FBI “was not able to confirm that this incident was initiated by a targeted cyber intrusion” (Vasquez, 2023). It appears more likely that it was an employee error (Cohen, 2021; Teal, 2023).

2.4 EMERGING CHEMICAL THREAT TECHNOLOGIES

2.4.1 Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning (AI/ML) and Quantum Computing

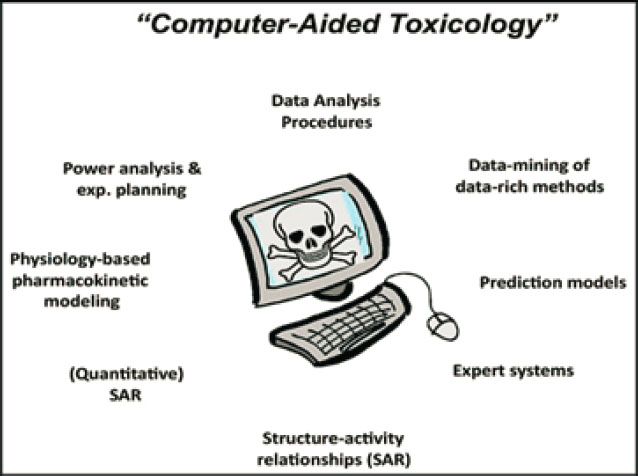

Computational chemistry is a combination of chemometrics, cheminformatics, and modeling. Chemical properties and features that affect the physiological activity of a compound can be predicted by combining chemometrics, cheminformatics, and quantum-structure activity relationship (QSAR)-based ML models (Figure 2-10).

Against this backdrop, a number of researchers have demonstrated the use of such capabilities to predict novel VX-related nerve agents (Urbina et al., 2022), vapor pressure for unascertained Novichoks (Jeong et al., 2022), and novel protein structures (Anishchenko et al., 2021). However, while such tools significantly lower barriers to entry for a motivated actor to design highly toxic compounds in silico, their use to actually enable a terror attack involving chemicals would still also require sophisticated chemistry, engineering expertise, materials to synthesize the candidate compounds, and to handle them safely until deployed—a difficult task for known chemicals, but which becomes more difficult for novel chemicals whose properties have not yet been studied (Nasser et al., 2022; Urbina et al. 2022). A number of factors combine to minimize the likelihood of terrorist use of such tools, such as (1) low incentive because other highly toxic chemicals that can be used in chemical attacks are more readily available, (2) limited access to specialized AI/ML capabilities, and (3) limited access to chemical precursors needed for synthesis. Additionally, large language models have modest safeguards against creating recipes for chemical weapons, and if those are circumvented, the poor quality of information on the web makes it unclear that these models will increase the risks of effective chemical terrorism. It is imperative that assessments on emerging technologies and their roles in chemical terrorism are grounded in both technical and operational rigor.

SOURCE: Hartung and Hoffman, 2009.

Advances in AI/ML are also being pursued to attempt to model and predict terrorist behavior and tactics (Uddin et al., 2020). Many of these attempts leverage social media (Al-Shaibani and Al-Augby, 2022), satellite imagery (Buffa et al., 2022), and other larger data sets (Krieg et al., 2022).

CONCLUSION 2-2: While AI and ML can be used to predict new chemical structures, the feasibility of converting predicted structures to weaponized chemicals is not straightforward and is thus unlikely in the near term (~ 5 years).

2.4.2 Synthetic Biology and the Chem-Bio Interface

For the potential applications of synthetic biology (i.e. “SynBio”) to chemical terrorism threats, three important concepts must be acknowledged (Kosal, 2021). First, SynBio is not a discrete homogenous thing. One of the most well-known tools of SynBio is the advanced gene editing technique known as CRISPR, which is a bacteria-derived system that uses specific proteins, such as Cas9, to “cut and paste” selectively into a genome. Applications of this technique include, for example, crop pesticide resistance, disease treatments, and biofuels. SynBio is a concern for chemical terrorism because if a toxic genetic material is coupled with an efficient delivery method then the outcome could potentially be lethal, although currently SynBio’s implications on security and safety remain largely uncertain.

First, Cas9 is not the only protein (e.g., Cas12 and Cas13), and CRISPR is not the only advanced gene editing system available. There is no single SynBio system to target when trying to assess potential threats. Even the “easiest” CRISPR synthesis is harder and requires more tacit knowledge and specialized equipment than the construction of an improvised explosive device (IED). The knowledge and skill required are well

within the capacity of most states and large transnational corporations; it is unlikely in the case of terrorists (Kosal, 2021).

Another example of a SynBio technique or process (that gets less popular attention) is cell-free synthesis (CFS) (Vilkhovoy et al., 2020). It is a method or platform to produce something, mostly small molecules like chemicals and proteins. CFS can serve as a replacement platform or alternative production means for something when cell-based systems are problematic (Lu, 2017; Vilkhovoy et al, 2020). Metabolic engineering and microbial cell factories (MCF) are another aspect of SynBio that bridges technique, process, and products. Microbial cell factories are means to produce materials, such as on-site synthesis of fuels, specialty chemicals, or other commodities that are not dependent on petrochemicals (Amer et al., 2020; Jiang et al., 2020; Linger et al., 2020; Nawab et al., 2020; Yan and Pfleger, 2020). In the committee’s judgment, terrorists are unlikely to pursue CFS or MCFs as a means to synthesize chemicals due to the sensitive and controlled conditions (temperature, media, enzymes) that are required for high-yielding growth.

Second, breakthroughs and discoveries in SynBio come from molecular biology, chemistry, physics, and multiple engineering fields; thus there is no single scientific discipline on which to focus security attention when considering the implications of this area.

Finally, and perhaps adding the greatest amount of complexity, synthetic biology is fundamentally “dual-use” in its nature. It is a dual-use technology, by both meanings of the term. Historically and in the nuclear policy world, dual-use means a demarcation between civilian and military uses. In the life sciences and much of cutting-edge scientific and engineering research, dual-use refers to the concept that the same or similar techniques, manufacturing elements, and processes used for beneficial purposes could also be misused for deleterious purposes. Almost all the equipment and materials needed to develop dangerous or offensive agents, particularly biological and chemical agents, have legitimate uses in a wide range of scientific research and industrial activity, including defensive military uses. Advances in synthetic biology and gene editing not only potentially pose security and proliferation concerns, but they also may enable new capabilities for defense, detection, and verification of chemical and biological agents. These advancements are, in addition to their important role in enhancing diagnostic capabilities for emerging infectious diseases, like COVID-19, have multiple other beneficial outcomes beyond therapeutic gene editing (Kosal, 2021). The dual-use nature of SynBio—and much of modern science and technology (S&T)—adds further complications to identification, countering, and response.

2.4.3 Advanced Materials Science

Advances in materials science have enabled the production of tailored materials where specific particle size, surface chemistry, porosity, and other properties can be purposefully produced. The interaction of particles with chemicals can repress (e.g., permeation barrier/timed release) or enhance (e.g., aerosolization aid) dispersal. Advanced materials for drug delivery are designed to move therapeutics across bar-

riers such as the mucosal barrier (Bandi et. al., 2021; Dong, 2018; Kosal, 2009). The same advanced materials and their underlying mechanisms that can be used to deliver beneficial therapeutics could be used for nefarious purposes to deliver toxic entities. The use of advanced materials represents a significant technological, financial, and personnel investment and thus has many barriers to deployment.

CONCLUSION 2-3: Advanced material science could enhance an attack but is much more of a concern with respect to significant large and well-resourced state-based programs than for terrorism in the near to medium term.

2.4.4 Small-Scale Reactors

Microfluidics or microreactors or “labs on a chip” involve chemical reactions taking place in very small, enclosed spaces. Picture a computer chip, but instead of wires, it has tiny channels, roughly the size of a human hair, where liquids flow and mix, though devices can also take other forms. Similarly, nanofluidics, or nanoreactors, involve channels an order of magnitude smaller, which potentially enables very precise control of reactions and their thermal output.

These advances have implications for both the chemical weapons threat and responses to it. For example, on the offensive side, it might enable the rapid synthesis and testing of novel chemical weapons agents or covert, on-demand production of threat agents. Defensively, it is already enabling more effective sensing devices and so-called organ-on-a-chip devices that facilitate research and development of new medical therapeutics.

In very different ways, advances in microfluidics may have implications for biological terrorism and, in more limited ways, nuclear terrorism, both of which are beyond the scope of this study. The term “microreactor” is also used to describe small nuclear power reactors (DOE, 2021), which have nothing to do with micron-level chemistry or biology.

Today, utilizing microfluidic devices requires more sophistication than utilizing traditional laboratory processes, and thus these techniques are mostly the domain of states or advanced corporations. In the future, as with many other advanced technologies, the dynamic is likely to invert, and the technology will likely become more turnkey, i.e., could be used with little or no understanding of what processes were actually occurring inside a device (just as someone needs no understanding of how the computer chips and other components in a smartphone operate to use one). Of course, even if in the future the technology supports such turnkey applications, this does not mean the market will provide them, or states will be powerless to regulate them. One application that has had limited investigation in the context of possible diversion from humanitarian or international development programs for misuse is the specialized field of frugal science, which often incorporates microfluidic elements (Tennenbaum and Kosal, 2021).

These advances constitute a powerful set of tools, but they also have limitations. One major limitation is corrosion, which is a challenge due to extensive surface area contact, often high chemical throughput, and delicate structures, mediated both by the chemicals being used and the materials out of which the structures are composed. Another challenge

is that precipitation reactions are unsuitable for microchemistry since solid precipitates can clog small channels (Zong and Yue, 2022). Among present-day chemical agents, microfluidics could be employed to produce some agents but not others.

In the chemical terrorism context, today microfluidic devices may bolster state efforts to respond to the threat, especially at the basic and applied research level. One could imagine extremely sophisticated nonstate actors, perhaps with relevant government or private sector experience, employing the technology offensively, but that seems relatively unlikely in the near future. The one potential caveat here is that state-supported terrorists might benefit from offensive applications of the technology. Down the road, it is at least conceivable that such advances might be employed by terrorists without state support, depending on how the technology and its accessibility evolve.

RECOMMENDATION 2-4: The intelligence community (IC) should continue to monitor interest in emerging technologies and delivery systems, such as drug delivery systems, and trends by terrorist groups to innovate and improvise. This is likely to look significantly different than the applications of advanced materials chemistry by GPS.

2.5 EMERGING ACTORS

Some terrorists, especially those of the mid-twentieth century, have used violence to seek political change and wanted to take control of political processes through violence, often in the context of anti-colonial or separatist efforts (Rapoport, 2004). Others, such as many early twenty-first-century terrorist groups, “don’t want a seat at the table, they want to destroy the table and everyone sitting at it.”8 In either case, the political element of terrorism remains. The nature of terrorism, evolution and dynamics of terrorist groups, geopolitics of responses, and broader study of topics related to terrorism are vibrant areas of scholarly work (Schuurman, 2020). In assessing the adequacy of current strategies to counter chemical terrorism, a brief overview of major trends of would-be perpetrators of chemical terrorism and some of the thinking on the future of chemical terrorism is warranted.

For the foreseeable future, the character of chemical terrorism-related threat actors seems likely to remain relatively constant or to evolve slowly. Yet, sharp discontinuities cannot be ruled out and are difficult to predict. If threat actors evolve significantly, this is likely to occur because of perceived changes in the perceived tactical and/or strategic benefits of using chemical agents, changes in ideology, or changes in various idiosyncratic factors related to motivation. Changes in the perceived benefits of chemical agents might also be related to the perceived lack of efficacy of other attack modes; in other words, chemical weapons might be so-called “weapons of the weak” to which actors who lack other alternatives turn. Certain types of terrorist groups—highly religiously identifying, apocalyptic, and right-wing, anti-government groups—have been shown to

___________________

8 Former CIA Director James Woolsey quoted in https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2001/10/29/what-terrorists-want.

have a greater propensity to use chemical (and biological) agents (section 2.1; Tucker, 2000). Understanding which types of groups and motives might be associated with future pursuit or use of chemical agents is important.

Potential changes in technology and their effects on the capabilities required to conduct chemical terrorism threats are dealt with above in section 2.4. However, it is worth noting that changes in technology might also spur changes in motivation. For example, if technological change makes certain forms of chemical terrorism more feasible, or, conversely, if technological change makes certain forms of nonchemical terrorism less feasible, that might lead previously less motivated actors to revisit their stances.

To date, there has often been an inverse relationship between various nonstate actors/terrorists’ motivations and capabilities to conduct CBRN terrorism, including chemical terrorism. Actors who are more capable are often less motivated to pursue CBRN terrorism. One reason for this is that more capable terrorists often fall into this category because they benefit from state sponsorship. They might thus be constrained by their state patrons. Conversely, actors who are more motivated to pursue unconventional weapons like chemical agents, are often less capable. One potential source of discontinuity in the future is a change in this dynamic, for example, more capable actors developing greater motivation or a more motivated actor developing greater capability.

Another potential source of discontinuity lies in the nexus between terrorism and crime. Terrorist groups often engage in crime to support their activities.9 Criminal groups sometimes morph into terrorist groups.10 And, of course, terrorists and criminals sometimes collaborate.11 The potential effects of chemical terrorism risk are various

___________________

9 There are many examples. On the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), see Hutchinson, Steven, and Pat O’Malley. 2007. “A Crime–Terror Nexus? Thinking on Some of the Links between Terrorism and Criminality.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 30(12): 1095–1107. doi: 10.1080/10576100701670870). LTTE happens to be the first confirmed case of nonstate actors using chemical weapons in warfare; see “The First NonState Use of a Chemical Weapon in Warfare: The Tamil Tigers’ Assault on East Kiran.” Small Wars & Insurgencies: (20)3–4. Another example is Al Shabaab; see Petrich, Katharine. 2022. “Cows, Charcoal, and Cocaine: Al-Shabaab’s Criminal Activities in the Horn of Africa.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 45(5–6): 479–500. doi: 10.1080/1057610X.2019.1678873).

10 On criminals morphing into terrorist groups, examples include D Company; see Clarke, Ryan and Stuart Lee.2008. “The PIRA, D-Company, and the Crime-Terror Nexus.” Terrorism and Political Violence (20)3: 376–395. doi: 10.1080/09546550802073334. al-Qa’ida in the Lands of the Islamic Maghreb’s (AQIM) offshoot Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) has recruited criminals into its organization; see Beevor, Eleanor. 2022. “JNIM IN BURKINA FASO: A Strategic Criminal Actor.” Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Burkina-Faso-JNIM-29-Aug-web.pdf). Mexican drug trafficking organizations have engaged in what is commonly labeled narcoterrorism; see Phillips, Brian J. 2018. “Terrorist Tactics by Criminal Organizations: The Mexican Case in Context.” Perspectives on Terrorism 12(1): 46–63. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26343745.

11 On cooperation between criminal organizations and terrorist groups, examples include Ndrangheta and al-Qa’ida; see Makarenko, Tamara and Michael Mesquita. 2014. “Categorizing the Crime–Terror Nexus in the European Union.” Global Crime. 15(3-4): 259–274. doi: 10.1080/17440572.2014.931227. Other examples include Basque Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA) and Italian criminal organizations or the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia–People’s Army (FARC) and Colombian drug cartels; on both, see Hutchinson, Steven, and Pat O’Malley. 2007. “A Crime–Terror Nexus? Thinking on Some of the Links between Terrorism and Criminality.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 30(12): 1095–1107. doi: 10.1080/10576100701670870.

and nuanced, given that transnational criminal groups are heavily involved in the drug trade, including the smuggling and production of synthetic narcotics.

An important dynamic, which could have either modest or more significant impacts, is demonstration effects. Terrorism tactics sometimes exhibit copycat dynamics or go “viral,” the classic example being suicide bombing. A chemical terrorist attack that is perceived as successful might motivate others to try to do likewise (see Dugan, LaFree, and Piquero, 2005; Guelke, 2017; Horowitz, 2010). Of course, the opposite is possible, too, i.e., observing a failed or ineffective chemical terrorism attack (and government or public responses to it) might motivate others to not pursue chemical terrorism.

The Islamic State’s recent use of crude chemical agents, to little effect, seems unlikely to motivate others to try to do likewise, nor are most other extant terrorist actors likely to achieve even the limited successes IS did. It is also striking that IS mostly used chemical agents in combat operations, rather than against civilian targets. Further, while IS publicly celebrated various forms of hyperviolence—like the burning to death of a captured Jordanian pilot—it continued to deny its own possession and use of chemical weapons.

On the other hand, the Syrian, Russian, and North Korean uses of chemical agents in recent years, in both indiscriminate and targeted ways, could perhaps inspire others (including nonstate actors) to try to do likewise. Indeed, another potential source of chemical terrorism-related discontinuities is state behavior. Whether any state behavior, even directly attacking civilians, is appropriately labeled terrorism is contested, though some would make the case that the label applies. And even if we limit terrorism to violence perpetrated by nonstate actors, states can be sources of both witting and unwitting aid to nonstate actors. With respect to the future threat of chemical terrorism in the near term:

- The most significant international chemical terrorism threats are likely to continue to be from jihadists, while the most significant domestic chemical terrorism threats facing the United States are likely to continue to be from far-right extremists.

- Cults are a potential source of threats, too, and given their insular nature and potential for rapid and extreme radicalization, the threat they pose is both difficult to predict and difficult to detect if it manifests.

- Lone actors appear likely to continue to be responsible for a large number of incidents but only modest consequences, with motivations including political/ideological, criminal, and mental health related.

- Whether and how certain emerging ideological milieus will interact with chemical terrorism remains unclear. This includes incels (men who identify as involuntary celibates and blame both women and certain other men), accelerationist12 dynamics that cut across various right-wing extremist milieus (with bolder goals and an associated willingness to take bolder action in service

___________________

12 See https://www.middlebury.edu/institute/academics/centers-initiatives/ctec/news/ctec-expert-philipp-bleek-recently-presented-threat-far.

of them), and anti-technology/industrialization extremists (including, but not limited to, certain environmental extremists).13

REFERENCES

Ackerman, G., C. Davenport, M. Binder, H. Tinsley, R. Earnhardt, C. Watson, M. Watson, and T. K. Sell. 2017a. Profiling the CB Adversary: Motivation, Psychology, and Decision. College Park, MD: START.

Ackerman, G., and M. Binder. 2017b. Chemical and Biological Non-State Adversaries Database (CABNSAD). College Park, MD: START.

Al-Shaibani, H. A. A., and S. Al-Augby. 2022. “Terrorist Tweets Detection using Sentiment Analysis: Techniques and Approaches.” In 2022 5th International Conference on Engineering Technology and its Applications (IICETA), 585–590. Al-Najaf, Iraq. https://doi.org/10.1109/IICETA54559.2022.9888461.

Amer, M., H. Toogood, and N. S. Scrutton. 2020. “Engineering Nature for Gaseous Hydrocarbon Production.” Microbial Cell Factories 19(1): 209.

Anishchenko, I., S. J. Pellock, and T. M. Chidyausiku. 2021. “De Novo Protein Design by Deep Network Hallucination.” Nature 600(7889): 547–552. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04184-w.

Bale, J. M. 2017. The Darkest Sides of Politics, II: State Terrorism, “Weapons of Mass Destruction,” Religious Extremism, and Organized Crime. Routledge.

Bale, J. M., and Ackerman G. A. 2009. “Profiling the WMD Terrorist Threat.” In WMD Terrorism: Science and Policy Choices, edited by Stephen M. Maurer, 11–46. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bandi, S. P., S. Bhatnagar, and V. V. K., Venuganti. 2021. “Advanced Materials for Drug Delivery across Mucosal Barriers.” Acta Biomaterialia, 119: 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2020.10.031.

BBC News. 1978. “Mass Suicide Leaves 900 Dead.”

Binder, M., and G. Ackerman. 2020. Profiles of Incidents Involving CBRN and Non-State Actors (POICN) Database. National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism. College Park, MD.

Binder, M., Gary Ackerman, Cory Davenport, Herbert Tinsley, Rebecca Earnhardt, Crystal Watson, Matt Watson, and Tara Kirk Sell. 2017. “Profiling the CB Adversary: Motivation, Psychology and Decision.” START College Park, MD. September.

Binder, M. K. and G. A. Ackerman. 2019. “Pick Your POICN: Introducing the Profiles of Incidents involving CBRN and Non-State Actors (POICN) Database.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism (March). https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1057610X.2019.15/77541.

Borzello, Anna. 2000. “Mass Graves Found in Sect House.” Guardian, March 25, 2000.

Buffa, C. V. Sagan, G. Brunner, and Z. Phillips. 2022. “Predicting Terrorism in Europe with Remote Sensing, Spatial Statistics, and Machine Learning.” ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 11(4): 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi11040211.

Cameron, G. 1999. Nuclear Terrorism: A Threat Assessment for the twenty-first century. New York: Macmillan Palgrave.

CAS. (n.d.). CAS Registry. https://www.cas.org/cas-data/cas-registry.

___________________

13 See https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1057610X.2018.1471972.

Casillas RP, Tewari-Singh N, Gray JP. “Special Issue: Emerging Chemical Terrorism Threats.” Toxicol Mech Methods. 2021 May;31(4):239-241. doi: 10.1080/15376516.2021.1904472. PMID: 33730980; PMCID: PMC10728888.

Caves, J. Jr., and W. S. Carus. 2021. “The Future of Weapons of Mass Destruction. An Update.” A National Intelligence University Presidential Scholar’s Paper. National Intelligence University. February.

Cohen, G. 2021. “Throwback Attack: An Insider Releases 265,000 Gallons of Sewage on the Maroochy Shire.” Industrial Cybersecurity Pulse. https://www.industrialcybersecuritypulse.com/facilities/throwback-attack-an-insider-releases-265000-gallons-of-sewage-on-the-maroochy-shire.

CRS (Congressional Research Service). 2006. CRS Report for Congress, Chemical Facility Security. August 2, 2006.

Dasenbrock, C.O., L. A. Ciolino, C. L. Hatfield, and D. S. Jackson. 2005. “The Determination of Nicotine and Sulfate in Supermarket Ground Beef Adulterated with Black Leaf 40.” Journal of Forensic Sciences 50(5) (September): 1134–1140. PMID:16225221.

DoD/CBDP (Department of Defense/Chemical and Biological Defense Program). 2023. Approach for Research, Development, and Acquisition of Medical Countermeasure and Test Products. https://media.defense.gov/2023/Jan/10/2003142624/-1/-1/0/approach-rda-mcm-test-products.pdf.

DOE (U.S. Department of Energy). 2021. What is a Nuclear Microreactor? Office of Nuclear Energy. February 26, 2021. https://www.energy.gov/ne/articles/what-nuclear-microreactor.

DOJ (U.S. Department of Justice). 2010. Amerithrax Investigative Summary. February 19, 2010, https://www.justice.gov/archive/amerithrax/docs/amx-investigative-summary.pdf; Bunn and Sagan (eds) Insider Threats (book), chapter on Amerithrax.

Dolnik, A. 2007. Understanding Terrorist Innovation: Technology, Tactics and Global Trends. New York: Routledge.

Dong, X. 2018. “Current Strategies for Brain Drug Delivery.” Theranostics 8(6): 1481–1493. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.21254.

Fischer, E., M.-M. Blum, W. S. Alwan, and J. E. Forman. 2017. “Sampling and Analysis of Organophosphorus Nerve Agents: Analytical Chemistry in International Chemical Disarmament.” Pure and Applied Chemistry 89(2): 249–258. https://doi.org/10.1515/pac-2016-0902.

The Guardian. 2016. “Failed Jewish Holocaust Survivor Plot to Kill Nazis Still a Mystery after 70 Years.” www.theguardian.com/world/2016/aug/31/jewish-holocaust-survivor-killnazis-poison-arsenic-nuremburg.

GAO (United States Government Accounting Office). 2020. Report to Congressional Requestors, Chemical Security. DHS Could Use Available Data to Better Plan Outreach to Facilities Excluded from Anti-Terrorism Standards. September 2020.

Gupta, R. C. 2015. Handbook of Toxicology of Chemical Warfare Agents. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-800494-4.

Hartung, T., and S. Hoffmann. 2009. “Food for Thought on in Silico Methods in Toxicology.” ALTEX—Alternatives to Animal Experimentation 26(3):155–166. https://doi.org/10.14573/altex.2009.3.155.

Hoffman, B. 1992. Terrorist Targeting: Tactics, Trends, and Potentialities. Santa Monica, CA: RAND.

Jenkins, B. 1986. “Defense Against Terrorism.” Political Science Quarterly 101, Reflections on Providing for “The Common Good” 101(5): 777–778.

Jeong, K., J. Y. Lee, S. Woo, D. Kim, Y. Jeon, T. I. Ryu, S. R. Hwang, and W. H. Jeong. 2022. “Vapor Pressure and Toxicity Prediction for Novichok Agent Candidates Using Machine Learning Model: Preparation for Unascertained Nerve Agents after Chemical Weapons Convention Schedule 1 Update.” Chemical Research in Toxicology 35(5): 774–781. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrestox.1c00410.

Jiang, T., C. Li, Y. Teng, R. Zhang, and Y. Yan. 2020. “Recent Advances in Improving Metabolic Robustness of Microbial Cell Factories.” Current Opinion in Biotechnology 66: 69–77.

Kosal, M. E. 2006. “Terrorism Targeting Industrial Chemical Facilities: Strategic Motivations and the Implications for U.S. Security.” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 30(1): 41–73.

Kosal, M. E. 2009. Nanotechnology for Chemical and Biological Defense. New York: Springer Academic Publishers. http://www.springer.com/us/book/9781441900616.

Kosal, M. E. 2021. “CRISPR & New Genetic Engineering Techniques: Emerging Challenges to Nonproliferation.,” Nonproliferation Review. 27(4–6), 389–408. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10736700.2020.1879464.

Kosal, M. E. 2021. “Assessing Threats of SynBio–Three Challenges.” NCT Magazine, July 2021. https://nct-magazine.com/nct-magazine-july/assessing-threats-of-synbio-three-challenges.

Kosal, M. E, and D. E. Anderson. 2004. “An Unaddressed Issue of Agricultural Terrorism: A Case Study on Feed Security.” Journal of Animal Science 82(11): 3394–3400. https://doi.org/10.2527/2004.82113394.

Krieg, S. J., C. W. Smith, R. Chatterjee, and N.V. Chawla. 2022. “Predicting Terrorist Attacks in the United States Using Localized News Data.” PLoS ONE 17(6): e0270681. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270681.

Lifton, R. J. 2007. “Destroying the World to Save It.” In Voices of Trauma, edited by B. Drožđek and J. P. Wilson. Boston, MA: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-69797-0_3.

Linger, J. G., L. R. Ford, K. Ramnath, and M. T. Guarnieri. 2020. “Development of Clostridium Tyrobutyricum as a Microbial Cell Factory for the Production of Fuel and Chemical Intermediates From Lignocellulosic Feedstocks.” Frontiers in Energy Research 8: 183. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2020.00183.

Lu, Y. 2017. “Cell-Free Synthetic Biology: Engineering in an Open World.” Synthetic and Systems Biotechnology 2(1) (March): 23–27.

Mulvaney, K. “Chemical Pollution is Soaring Faster than we can Measure it.” Seeker. Published February 1, 2017. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://www.seeker.com/chemicalpollution-is-soaring-faster-than-we-can-measure-it-2231114982.htm

Nasser, L. 2022. “40,000 Recipes for Murder.” Radiolab. https://radiolab.org/episodes/40000recipes-murder.

Nawab, S., N. Wang, X. Ma, and Y-X. Huo. 2020. “Genetic Engineering of Non-Native Hosts for 1-Butanol Production and Its Challenges: A Review.” Microbial Cell Factories 19(1): 79.

Rapoport, D. C. 2004. “The Four Waves of Modern Terrorism.” In Attacking Terrorism, Elements of a Grand Strategy, edited by Audrey Kurth Cronin and James M. Ludes, 46–73. https://press.georgetown.edu/Book/Attacking-Terrorism.

Reymond, J. -L. 2015. “The Chemical Space Project.” Accounts of Chemical Research 48(3): 722–730. https://doi.org/10.1021/ar500432k.

Santos, C, et al. 2019. “Characterizing Chemical Terrorism Incidents Collected by the Global Terrorism Database, 1970–2015.” https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/prehospital-and-disaster-medicine/article/abs/characterizing-chemical-terrorism-incidents-collected-by-the-global-terrorism-database-19702015/DDC014FA265072B42234F86C4D337262.

Schuurman, B. 2020. “Research on Terrorism, 2007–2016: A Review of Data, Methods, and Authorship.,” Terrorism and Political Violence 32(5): 1011–1026. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2018.1439023.

Smithson, A. E., and L.-A. Levy. 2000. “Chapter 3—Rethinking the Lessons of Tokyo” (pdf). Ataxia: The Chemical and Biological Terrorism Threat and the U.S. Response (Report). Henry L. Stimson Centre. 91–95, 100. Report No. 35. Archived from the original on December 25, 2014.

START (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism). 2022. Global Terrorism Database 1970–2020 [Data File]. https://www.start.umd.edu/gtd.

Teal, C. 2023. “Florida City Water Cyber Incident Allegedly Caused by Employee Error.” Route Fifty, March 21, 2023. https://gcn.com/cybersecurity/2023/03/florida-city-water-cyber-incident-allegedly-caused-employee-error/384267.

Tennenbaum, M., and M. E. Kosal. 2021. “The Interplay Between Frugal Science and Chemical and Biological Weapons: Investigating the Proliferation Risks of Technology Intended for Humanitarian, Disaster Response, and International Development Efforts.,” In Weapons Technology Proliferation: Diplomatic, Information, Military, Economic Approaches to Proliferation, edited by M. E. Kosal, 153–204. Springer Academic Publishers, August 2021. https://www.springer.com/us/book/9783030736545.

Tucker, J. B. ed. 2000. Toxic Terror: Assessing Terrorist Use of Chemical and Biological Weapons. MIT Press.

Tucker, J. B. 2006. War of Nerves: Chemical Warfare from World War I to Al-Qaeda. Anchor.

Uddin, M. I., N. Zada, F. Aziz, Y. Saeed, A. Zeb, S. A. A. Shah, M. A. Al-Khasawneh, and M. Mahmoud. 2015. “Prediction of Future Terrorist Activities Using Deep Neural Networks.” Complexity 2020(1): 16, Article ID 1373087. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/1373087.

Urbina, F., F. Lentzos, C. Invernizzi, and S. Ekins. 2022. “Dual Use of Artificial-Intelligence-Powered Drug Discovery.” Nature Machine Intelligence 4(3): 189–191. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-022-00465-9.

Vasquez, C. 2023. “Did Someone Really Hack into the Oldsmar, Florida, Water Treatment Plant? New Details Suggest Maybe Not.” CyberScoop, April 10, 2023. cyberscoop.com/water-oldsmar-incident-cyberattack.

Vilkhovoy, M., A. Adhikari, S. Vadhin, and J. D. Varner. 2020. “The Evolution of Cell Free Biomanufacturing,” Processes 8(6): 675–694.

Yan, Q., and B. F. Pfleger. 2020. “Revisiting Metabolic Engineering Strategies for Microbial Synthesis of Oleochemicals.,” Metabolic Engineering 58: 35–46.

Zong, J., and J. Yue. 2022. “Continuous Solid Particle Flow in Microreactors for Efficient Chemical Conversion.” Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 61(19): 6269–6291. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.2c00473.

This page intentionally left blank.