Chemical Terrorism: Assessment of U.S. Strategies in the Era of Great Power Competition (2024)

Chapter: 4 Adequacy of Strategies to Identify Chemical Threats

4

Adequacy of Strategies to Identify Chemical Threats

Summary of Key Findings, Conclusions, and Recommendations

FINDING 4-1: Most federal agencies surveyed by the committee acknowledge that overall terrorists seeking to perpetrate chemical attacks tend to opportunistically misuse traditional classes of chemicals, primarily toxic industrial chemicals and toxic industrial materials.

FINDING 4-2: The federal agencies that briefed the committee indicated that the total number of potential chemical threats—whether existing, emerging, or yet to be designed—that can or could be used for weapons of mass destruction is vast and expanding.

FINDING 4-3: The agencies surveyed are broadly aware of each other’s efforts to identify, prevent, counter, and respond to chemical threats, but express concern that information-sharing and coordination across relevant agencies is incomplete.

CONCLUSION 4-4a: It is impossible to identify, prevent, or counter every threat. Overall, the majority of publicly reported domestic plots did not come to fruition between the 1970s through the mid-2010s for a number of reasons.

CONCLUSION 4-4b: The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and partner law enforcement and intelligence communities (IC) have been effective in identifying and interdicting the majority of domestic terrorist attacks involving chemical materials, which have typically employed conventional toxic industrial chemicals rather than traditional chemical warfare agents, such as sarin. While the FBI has been effective, approaches to identifying chemical threats could be strengthened

using a multilens approach from several different agencies that emphasizes augmented communication and coordination between local and state enforcement and IC. In addition, this area would greatly benefit from increased coordination between the IC and technical experts (particularly those with specific expertise in the areas of terrorist motivation and psychology). For example, FBI antichemical terrorism resources focused on identification could be evaluated in the context of current identification strategies employed by other agencies.

RECOMMENDATION 4-4: Existing intelligence community programs should actively seek and incorporate new approaches to identify existing chemical threats (traditional and improvised) and potential emerging threats by terrorist groups. In developing new approaches, program managers should develop strategies that look beyond the traditional terrorism suspects and that augment and leverage skill sets of the U.S. Government agencies. For example, scholars of political psychology could work with chemical terrorism experts to create a holistic approach of identifying chemical terrorist groups or similar violent actors outside the traditional suspects. The threat assessments should be improved by reflecting the current times and demographics.

FINDING 4-5: The shift to great power competition may change the nature of the threat for new chemical attacks, in that chemical agents, other materials, technology, and expertise may migrate from state actors that engage in either defensive or offensive activities to violent extremist organizations (VEOs). These events could enable VEOs to conduct more sophisticated attacks, with agents and/or with means of delivery not otherwise accessible to them.

RECOMMENDATION 4-5: The National Counter Terrorism Center (NCTC), Department of Defense (DoD), Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and State Department should review current identification approaches to determine whether shifts in emphasis are required as a result of expanded and augmented VEOs and terrorist capability resulting from the potential migration of chemical agents, other materials, technology, and expertise from state actors to VEOs.

CONCLUSION 4-6: It is unclear if the tactical readiness to implement the reviewed strategies is occurring at the necessary pace to respond to an act of chemical terrorism. Additionally, the shift in strategic focus to great power competition (GPC) may lead to reduced resources for countering acts of terrorism employing weapons of mass destruction that are perpetrated by VEOs, and may impede tactical readiness against chemical terrorist threats, leading to increased risk.

RECOMMENDATION 4-6: The United States Government (USG) should ensure that the identification of chemical terrorism threats is explicitly included in ongoing and future strategies. Chemical terrorism threats should be considered distinct from nuclear nonproliferation, identification of state-based offensive chemical programs, and traditional (non-nuclear-biological-chemical) terrorism.

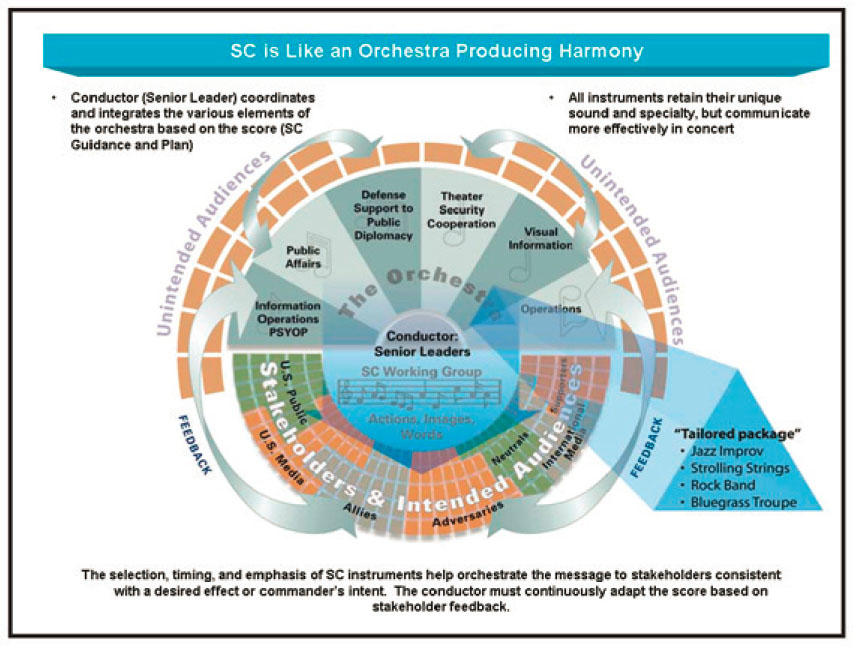

Effective strategic communications can be compared to an orchestra producing harmony (see Figure 4-1). Best practices include the empowerment of a single individual—the conductor, who coordinates and integrates the various instruments—all of which retain their unique sound and specialty while communicating more effectively in concert. Further, the conductor must continuously adapt their interpretation of the score based on stakeholder feedback:

The panoply of U.S. force actions must be synchronized across the operational battlespace to the extent possible so as not to conflict with statements made in communications at every level from President to the soldier, sailor, marine, or airman on the street (Rand Corporation 2007).

The committee’s discussions with agency representatives (see Appendix A) highlighted important gaps in the area of identifying, communicating, and responding to chemical threats that should be addressed to enable timely response to real-world weapons of mass destruction terrorism (WMDT) incidents involving chemical threats.

One of the most significant challenges associated with a successful implementation of strategies to counter WMDT chemical threats is a smooth coordination of the various activities to ensure actionable threat awareness. Using the orchestration analogy described earlier to actionably identify WMDT chemical threats, the National Security Council (NSC) composes the score—specifically, the Global Chemical Deterrence Framework and NCTC plays the role of conductor, convening representatives from across the IC as well as other stakeholder agencies responsible for preventing, countering, and responding to carry out lines of effort outlined in the score (the Global Chemical Deterrence Framework).1 As the composer, the NSC plays a significant role in leading planning, and documenting specific actions to be taken by each stakeholder agency, promulgating the guidance, and integrating mature capabilities into strategic guidance to enable chemical threat recognition and response at timescales of relevance. As the conductor, NCTC then interprets the NSC’s guidance (the Global Deterrence Framework and other strategic guidance) and uses it to convene other IC agencies to assess threats and communicate findings to other stakeholder agencies responsible for preventing, countering, and responding in a timely enough manner to enable their mission success. The various IC agencies and other stakeholders, as fellow members of the orchestra, invest in needed research and integrate mature research into operational use to enhance their abilities to play their parts (e.g., conduct their respective missions). If the strategic guidance is implemented effectively, the IC’s synchronized activities will enable the USG to be nimbler in the face of evolving threats, in turn facilitating more accurate and actionable identification. Therefore, it is important that the NSC institutionalizes the information-sharing efforts being conducted by NCTC and that lines of effort be adjusted as threats evolve.

Prioritization of whether a chemical should be considered a threat largely occurs through coordination within interagency working groups. These activities have grown into robust avenues for information exchange that may yield benefits for successfully identifying and countering WMDT chemical threats as well as collaboratively adjusting lines of effort as threats develop. The committee’s discussions with the agencies involved with

___________________

1 DoD JP-40, Appendix A.

SOURCE: Commander’s Handbook for SC and Communication Strategy (Ver2.0 U.S. Joint Forces Command, 2009).

research, development, testing, and evaluation (RDT&E) focused on activities to recognize and respond to chemical threats. Box 4-1 outlines three major themes that were heard.

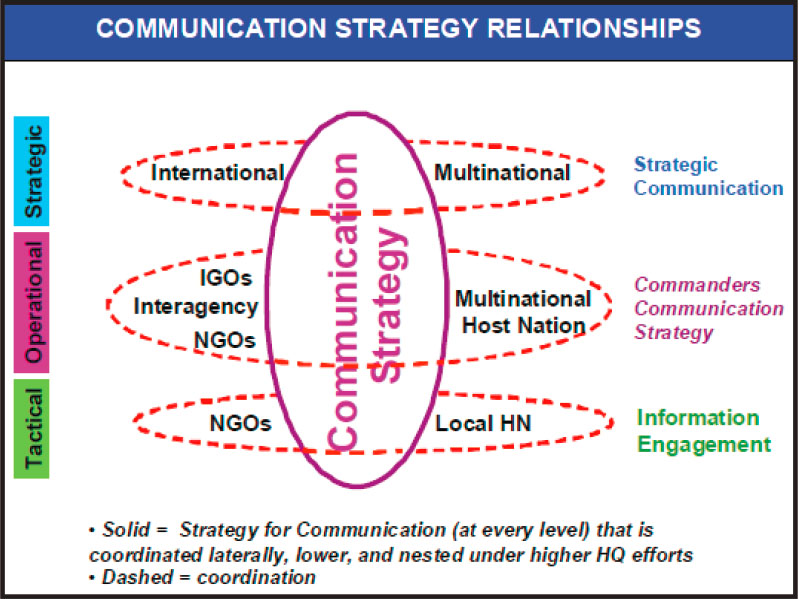

Based on briefings and follow-on discussions conducted by the committee, opportunities for improvement in communications at the tactical, operational, and strategic levels are needed for establishing, or updating, and carrying out strategies assessed in support of this study (see Figure 4-2). In terms of strategic communication, the tactical level focuses on direct information engagement between agencies and other entities; the operational level deals with commanders’ and agency directors’ communications strategies both for staff in their organizations and with external stakeholders; and the strategic level deals with national-level strategic communications. While the committee was made aware of some best practices, these appeared to be conducted on an as needed basis and were largely driven by individual personalities or relationships within or between agencies.

Tactical: Briefings provided by a few of the IC agencies highlighted the need to engage more stakeholders in relevant communication mechanisms, such as working groups and issues-focused events. In addition, the committee believes that the benefit of including more technical experts—from Department of Energy (DOE) laboratories, private laboratories, and universities—in interagency discussions beyond those person-

BOX 4-1

Three Themes Committee Heard from Information-Gathering Meetings

- Important work is being undertaken to identify chemical terrorism threats and to develop capabilities to respond.

- The successes communicated to the committee are at the basic research level and require further optimization before these approaches can be integrated into strategy and tactical operations.

- It is not clear that the briefers were fully cognizant of efforts and key capabilities resident in other agencies, or of the need to ensure that the capabilities being developed in one agency are broadly available to other agencies.

nel from DoD laboratories far outweighs the potential security concerns. The negative strategic impact of an undetected Skripal poisoning-like scenario (see Appendix E) on the homeland is an example of why it is important to include all relevant experts surrounding the issue at hand. Certain ad hoc interagency working groups have done this successfully and could serve as a standard for routine engagement.

Operational: The committee heard several briefings that show excellent coordination between DoD’s research arms (Defense Threat Reduction Agency [DTRA], The Joint Program Executive Office [JPEO], U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command [CCBC], Chemical Biological Center [CBC]) when it comes to preparing and equipping the warfighter to identify, prevent, counter, or respond to WMDT chemical threats. However, it is not clear that this level of coordination exists between these DoD entities and other research institutions (e.g., DOE laboratories, private institutions, or universities, where their expertise is relevant) or for preparing and equipping warfighters’ civilian counterparts to identify, prevent, counter, or respond to WMDT attacks on the homeland involving chemicals.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) has strong functioning relationships with the DHS and maintains personnel within the DHS WMD organizations, which serves as an example of an organization that has strong operational communications (Savage, 2022). The FBI also maintains relationships with the National Laboratory community to anticipate future chemical threats. Communications between the FBI and state and local authorities is achieved through the Threat Credibility Office which is staffed 24/7; this office functions to convene experts throughout the duration of an event. The WMD coordinators are also on call, and they have relationships with first responders and the National Guard. Interaction of these entities with the National Guard is exercised frequently through the Threat Credibility Evaluation (TCE) process, which includes the Livewire program. Annual exercises involving full-field response to a simulated WMD incident are conducted. The FBI maintains robust online surveillance, the details of which are at a higher level of classification (Rotolo, 2022).

SOURCE: Ver2.0 (U.S. Joint Forces Command, 2009).

Strategic: A renewed focus on strategic communication is needed—either to counter the narratives put forward by adversaries or to deter attacks by communicating capabilities that lead adversaries to conclude that WMDT involving chemicals is unlikely to yield the desired success. Efforts in 2022 undertaken by the DTRA-Cooperative Threat Reduction (DTRA-CTR) program illustrated a successful example of strategic communication. DTRA-CTR identified a potential biological threat imposed through disinformation;2 specifically, the organization proactively communicated the goals and successes of its partnerships with public health laboratories in Ukraine to counter the narrative put forth by popular media personalities and others, where the disinformation suggested nefarious USG involvement to produce biological weapons-related laboratories (NPR, 2022). The level of proactive communication recently demonstrated by the DTRA-CTR program and its leadership in countering disinformation could be emulated and adopted into more routine practice by other relevant agencies and programs.

Like conducting an orchestra, successful communication across relevant agencies is essential for identifying chemical threats. All stakeholders involved should receive the intended message clearly and be able to cohesively relay the information to others.

___________________

2 Disinformation is deliberately crafted to mislead, harm, or manipulate a person, social group, organization, or country (CIS, n.d.).

Nested within this paradigm are tactical, operational, and strategic communications; all functions necessary to manage, implement, and communicate the directions for identifying, preventing, and responding to immediate and potential chemical threats. The following discussion considers these aspects with respect to “identify” within the Committee’s evaluation of the strategy documents.

4.1 ANALYSIS OF STRATEGIES TO “IDENTIFY” WMDT CHEMICAL THREATS

As outlined in the description and analysis of the Baseline Threat in Chapter 2, while the number of terrorist incidents involving the use of WMD over the last two decades is low in comparison to terror attacks using conventional weapons, WMD-involved terror attacks that employed chemicals make up the largest percentage of such attacks. Therefore, in assessing existing strategies’ sufficiency to actionably identify chemical terrorism threats, it is important to consider the following two points:

- The occurrence or nonoccurrence of terror attacks involving chemicals is not a direct indication that the United States was or was not successful in identifying a particular threat.

- The existence or absence of these chemical terror attacks does not imply a strategy’s sufficiency, or that the strategy has been successfully or properly implemented.

Significantly more detailed analysis beyond the scope of this study would be required in order to make such an assessment that adequately evaluates these two parameters. The committee recognizes their assessment is necessarily based on the information available to the committee and within the constraint of the time and resources allotted for the study; thus, it is also important to recognize it is impossible to know beforehand every possible chemical threat. This level of information is not a criterion for success in this analysis.

Box 4-2 lists the documents that were analyzed for “identify” against the methodology described in Chapter 3. The committee recognizes that this subset of documents, while selected to be inclusive and representative of major programs across the USG, may have limitations; however, they serve as an appropriate representation of strategies put forth by key agencies that are able to implement actions for successfully identifying chemical terrorism threats.

4.1.1 Committee Definition of Adequacy: Identify

The committee views that a successful strategy to identify chemical terrorism threats focuses on robust information-sharing regarding the following:

- Chemicals that may be used in an attack—both known chemical weapon agents, toxic industrial chemicals/toxic industrial materials (TICs/TIMs), and lesser known emerging agents;

BOX 4-2

Strategy Documents Reviewed by Committee for “Identify” Analysis

- White House. (2018). National Strategy for Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Terrorism.

- Department of Homeland Security. (2019). Department of Homeland Chemical Defense Strategy.

- Office of the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Chemical and Biological Defense. (2020). Enterprise Strategy.

- Department of Defense. (2017). National Security Strategy of the United States of America, National Strategy for Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Terrorism.

- Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Publication 3-40. (2019, validated 2021). Joint Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction.

- Threat actors who may use or pursue chemicals for use in WMDT attacks; and

- Entities that may support or sponsor chemical attacks or terrorism.

The committee’s analysis considered all three of these aspects. Successful “identify” strategies focus on developing actionable information to facilitate preventing, countering, and responding to the identified threats. A strategy had to be determined to adequately address each (prevent, counter, respond) to be judged “adequate” in the area of identify.

4.1.2 Clearly Defined Ends Are Adequate, but Ways and Means Are Not Apparent

The strategy documents reviewed by the committee all have clearly stated goals that include an explicit definition of success. In particular, the Chemical and Biological Defense Program (CBDP) Enterprise Strategy provides an explanatory paragraph describing what the organization views as success. Using a standard description of ways to assess strategy (Deibel, 2007), we found that in the CBDP strategy, a “desired end” was applied to each stated goal, along with detailed descriptions of “ways” (e.g., how) the goals were to be achieved. However, explicit descriptions of available resources to implement the strategies, “means,” were absent from the documents’ discussion.

The committee was able to glean some information regarding “means” during briefings with representatives from DTRA, DHS, Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command Chemical Biological Center (DevCom CBC), and the State Department (see Table A2 in Appendix A). However, DoD CBDP’s ability to orchestrate other agencies’ use of the means available to them remains unclear. Specifically, under the CBDP enterprise

strategy cross-cutting goal, “Drive Innovation,” stated objectives include broadening and strengthening relationships within DoD and the Enterprise and building internal and external partnerships with the IC to ensure intelligence support to Enterprise research. To accomplish these objectives, CBDP will increase the frequency and quality of engagements with partners seeking complementary solutions, such as Public Health agencies while leveraging the best practices in the biopharmaceutical industry to speed RDA and regulatory approval of vital MCMs and focus partnerships with American industry to help align private sector research, development, and acquisition (RDA) to national security priorities. However, CBDP cannot achieve the intended increased engagement on its own; it must be met by corresponding prioritization and enablement of engagement on the part of other agencies. In the committee’s discussion with DHS Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Office (DHS CWMD). The speakers observed that stakeholders responsible for addressing known or emerging chemical threats lack both the authority and sufficient “means” in the form of personnel resources or funding to act with an adequate level of completeness or timeliness. This insufficiency creates a challenge for DHS CWMD to effectively deploy their charge of coordinating and ensuring information-sharing across the whole of government, private, industry, and state, local, tribal, and territorial (SLTT). The DHS CWMD strategy document demonstrated similar observations. The fourth goal in the strategy related to threat identification stated, “collaborate with SLTT governments, private sector partners and other key stakeholders to prioritize and share timely, accurate and actionable information,” (DHS, 2019, Pg. ii) however, the goal did not specify available resources (“means”) or levers available to encourage the occurrence (“ways”) of this type of collaboration. The fact that both the CBDP Enterprise Strategy and the DHS CWMD Strategy include goals associated with improving collaboration and coordination may indicate that CBDP and DHS CWMD are working at cross-purposes.

Based on these observations, the committee judges the strategies to be partially adequate. In the committee’s review of the strategy documents and through briefings and discussions with representatives from DHS, DTRA, DevCom CBC, State Department, NCTC, and BARDA, clearly defined lines of effort were evident, and the representatives were able to describe both ways in which they are implementing the strategies and means being used to do so. The committee judged that the specific goals and supporting lines of effort outlined in the strategy documents are both appropriate for accomplishing the desired ends and are coherent overall. Although, briefers repeatedly acknowledged the reality that it is impossible to identify every single threat and further, that the level of resourcing is insufficient to be fully successful. Additionally, none of the strategies addressed how it is intended for them individually or collectively to sustain enduring success over time, given the reality of shifting political priorities and the ebbs and flows of funding that inevitably result from such shifts.

4.1.3 Roles of TICs TIMs in Increasing Risk of Chemical Terror Attacks

The threat of terrorism involving TICs/TIMs has been detailed in chapter 2. The committee reviewed how the strategy documents addressed the identification of threats associated with TICs/TIMs, in order to test the soundness of the “identify” analysis.

DHS Defense Strategy emphasizes the identification and mitigation of threats originating from TICs and TIMs opportunistically used in a chemical attack by VEOs. The DHS Strategic Plan (DHS, 2022) states that “chemical materials and technologies with dual-use capabilities are more accessible throughout the global market,” (Pg. 15) and that the proliferation of information and technologies provides augmented opportunities for rogue nations and nonstate actors to develop, acquire, and use WMD.

DHS Chemical Defense Strategy (DHS, 2019) notes that state and nonstate actors have deployed TICs and TIMs in a variety of offensive uses. DHS acknowledges that manufacturing, storage, and transportation infrastructure pose a danger as sources of a release. The DHS Chemical Defense Strategy acknowledges that identification of these threats is complicated by the reality that the TICs have legitimate industrial, agricultural, or pharmaceutical applications and that production may be concealed “within industrial or agricultural production facilities, and academic or pharmaceutical labs” (DHS, 2019, Pg. 5). A specific DHS objective focuses on both state and nonstate actors plotting or perpetrating incidents involving the chemical industry so that chemical incident risks and adversary capabilities that might employ TICs and TIMs are understood. Further, DHS is engaged with characterizing and forecasting chemical risks specific to geographic and economic sectors as potential terrorism targets, which clearly indicates TICs and TIMs as a major source of concern.

DHS’s concern regarding TICs and TIMs is further substantiated by the National Infrastructure Protection Plan (NIPP) (DHS, 2013), which emphasizes the assessment and analysis of risks derived from storage, manufacture, and transportation of chemicals. Concern over the use of TICs and TIMs is also reflected in Chemical Facility Anti-Terrorism Standards (CFATS), which developed standards for chemical safety and security at facilities where chemicals are stored and manufactured. The CFATS program included a standard focused on sabotage, which would include attacks by VEOs. These observations indicate that DHS considered incidents where TICs and TIMs would be employed to be significant threats.

In contrast, the DoD strategy does not emphasize threats involving VEOs utilizing TICs and TIMs. DoD strategy notes that response to domestic events is to be led by the FBI for all terrorist-related incidents and threats (JCS, 2019); however, with regard to chemical threats, the DoD strategy acknowledges that the Department may play a supporting role in response (DoD, 2014). Furthermore, the DoD Task Force on Deterring, Preventing, and Responding to the Threat or Use of Weapons of Mass Destruction noted that the threat from adversaries, both military and civilian, was growing and that it was difficult to detect before the event (DSB, 2018). The DoD report specifically noted that new experimentation in the uses of TICs was on the rise and that there was reasonable willingness of organizations to use these.

FINDING 4-1: Most federal agencies surveyed by the committee acknowledge that overall, terrorists seeking to perpetrate chemical attacks tend to opportunistically misuse traditional classes of chemicals, primarily toxic industrial chemicals and toxic industrial materials.

4.1.4 Increasing Diversity of Chemical Threats

The identification of chemical threats has become more challenging, and the difficulty in chemical threat identification is expected to increase. The array of chemical substances and materials that have been employed as chemical agents has increased, a reality that is acknowledged by the DoD strategy documents (JCS, 2019; The White House, 2018). Furthermore, the number of chemicals with potential for use as agents will certainly continue to grow. In addition, the identification of threats is exacerbated by an increased diversity of actors and the dual-use nature of related technology and expertise (Trump, 2017). Further complications are anticipated because of breakthroughs in chemistry resulting in the generation of deadlier chemical agents, such as fourth-generation agents (JCS, 2019). Nontraditional agents, such as pharmaceutical-based agents (PBAs) (DOS, 2022), and nerve agents expand the range of substances that could be considered as potential threats (Hersman et al., 2019). The likelihood of these threats materializing or being identified could be augmented by increasing availabilities of emerging science and technologies (e.g., advanced material science, AI/ML, small-scale reactors) as discussed in Chapter 2.

FINDING 4-2: The federal agencies that briefed the committee indicated that the total number of potential chemical threats—whether existing, emerging, or yet to be designed—that can or could be used for weapons of mass destruction is vast and expanding.

4.1.5 Cross-Agency Communication

The “identify” function is potentially problematic to the countering of weapons of mass destruction and terrorism (CWMDT) endeavor because there are multiple agencies involved, in terms of chemicals that could be used as agents (whether current or emerging chemical weapons agents (CWAs), or TICs and TIMs), targets, and prospective perpetrators. Agencies conducting identification activities may not be those who would be involved with deterrence or interdiction. Therefore, interagency communication is of paramount importance. JP 3-40 states:

CWMD requires unity of effort, which results in a coordinated response of combined capabilities of the USG. Coordination between DoD and other USG departments and agencies is critical to the success of CWMD operations against the global WMD threat (JCS, 2019, A-6).

As mentioned earlier, the NSC Staff has the responsibility of overseeing lines of communications between USG departments and agencies involved in CWMDT activities with the objective being to leverage all instruments of national power—the orchestrator (JCS, 2019).

The subsequent sections (4.2.5a and 4.2.5b) discuss two major challenges observed by the committee in their analysis of the strategies. The first challenge involves dis-

closing pertinent information and balancing the risks involved in identifying and communicating the chemical threat. Second, understanding the different coordination roles and responsibilities of each agency remains a challenge between relevant entities. The analysis of the strategy documents allowed the committee to unpack specific details underpinning these issues.

4.1.5a Protecting Sensitive Information and Ensuring Adequate Identification of Chemical Terror Threats

DHS strategy clearly emphasizes communication, stating that the agency will collaborate with SLTT, the private sector, and others for prioritizing and sharing timely accurate and actionable information (DHS, 2019). Information-sharing with federal agencies and first responders is important, however, a challenge is to “closely scrutinize classification levels to achieve the broadest distribution of information, while protecting sensitive information.” (DHS, 2019, Pg. 7). Information-sharing is also emphasized in the National Infrastructure Protection Plan (NIPP, a DHS document) (DHS, 2013a). Specifically, the NIPP includes a detailed section specifying the establishment of Sector Coordinating Councils, which are to enable strategic communication and coordination between the private sector and government in response to emerging threats, or response and recovery operations. In parallel, the NIPP includes government coordinating councils to ensure cross-jurisdictional coordination. This is to ensure information-sharing across sectors and to promote public-private information-sharing. The NIPP establishes four cross-sector councils for the purpose of planning: these address (1) critical infrastructure, (2) Federal Senior Leadership, (3) SLTT government, and (4) the regional consortium Coordinating Council. A key concept in the NIPP is that the document “integrates efforts by all levels of government, private, and non-profit sectors by providing an inclusive partnership framework and recognizing unique expertise and capabilities each participant brings to the national effort.” (DHS, 2013b) The NIPP also establishes the National Infrastructure Coordinating Center (NICC) and the National Operations Center, which are focused on cross-agency and public/private sector communication and coordination.

4.1.5b Recognizing Roles and Responsibilities of Agencies and Programs

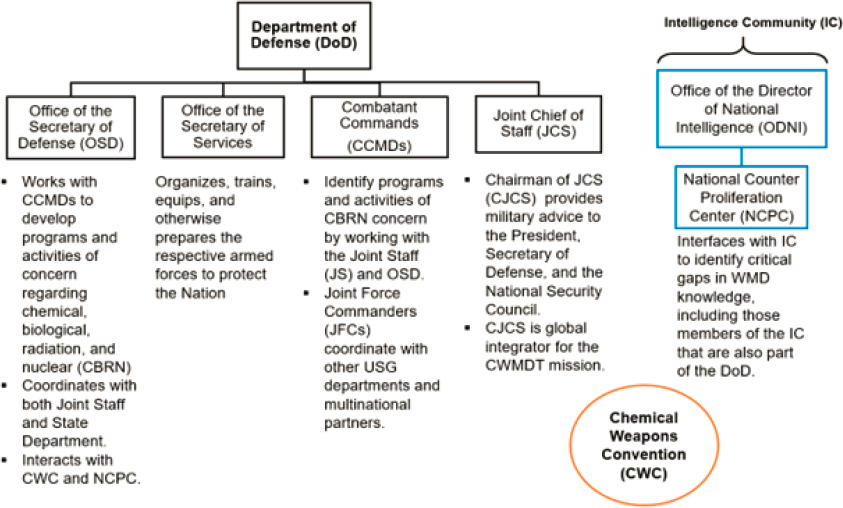

DoD strategy acknowledges that the State Department is the “USG lead agency for CWMD operations abroad” and that DoD has a supporting role (JCS, 2019, A-1). Figure 4-3 illustrates the coordination roles among the different offices with the DoD and their responsibilities with respect to chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN). Within the DoD, it is the responsibility of the combatant commands (CCMDs) to identify programs and activities of concern by coordinating with the Joint Staff (JS) and Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD). Joint Force Commanders (JFCs) are tasked with coordinating and cooperating with other USG departments and multinational partners. Communication with the President, NSC, and OSD falls under the responsibility of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS), which is also designated as the

global integrator for the CWMDT mission. The OSD coordinates with both JS and the State Department. Further, OSD interactions with the international Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), and the National Counter Proliferation and Biosecurity Center (NCBC) are specifically noted as part of their responsibilities.

The NCBC, under the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI), is charged with coordinating the IC to identify critical gaps in WMD knowledge, including those members of the IC that are also part of the DoD (JCS, 2019). The emphasis within NCBC appears to be in the area of nuclear counter-proliferation.

Since 2018, the United States Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) has led the mission to counter-proliferation of WMD within the DoD. It took over the lead role from U.S. Strategic Command (USSTRATCOM), which retains the lead in strategic deterrence, nuclear operations, and other missions related to nuclear weapons capabilities. USSOCOM is responsible for CCMDs, JS, other DoD agencies, other USG departments and agencies, and partner nations for CWMDT assessment and “transregional synchronization” (JCS, 2019). USSOCOM established the CWMD Fusion Cell, which coordinates planning across organizations (USSOC, 2020). USSOCOM’s J10 directorate, based both in the National Capital Region and at USSOCOM Headquarters conducts strategic planning, assesses the department’s execution of the CWMD campaign, and makes recommendations to the CJCS and the Secretary of Defense (HASC, 2021). Table 4-1 lists and describes other agencies and programs outside of DoD that have key roles in addressing chemical terrorism.

TABLE 4-1 Key Players Involved in “Identify”

| Federal Agency | Programs | Description |

|---|---|---|

| National Intelligence Council—Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) | National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC) |

NCTC

|

| Department of Justice (DOJ) and Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) | Weapons of Mass Destruction Directorate (WMDD) | WMDD provides intelligence support for the FBI field divisions and the rest of the IC on domestic cases. Each field division has a special agent who is the WMD coordinator. |

| Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) | Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ASTDR) | ASTDR works with communities at the local level that are responding to disasters, including those involving hazardous substances |

Section 5 of Appendix A of Joint Publication 3-40 explicitly discusses Interagency Coordination and Interorganizational Cooperation (JCS, 2019). For domestic operations, as described earlier, DoD will operate in a supporting role to another USG department or agency. This supporting role is detailed in JP 3-28, Defense Support of Civil Authorities. Interorganizational cooperation is stipulated at the strategic, operational, and tactical levels; the importance of these interactions “cannot be overstated” (JCS, 2019, A-15). When state and local coordination is required, the Chief of the National Guard Bureau (CNGB) will transition to federalized status according to Title 10, U.S. Code,3 for the CBRN response. Coordination is detailed in JP 3-08, Interorganizational Cooperation, and JP 3-41, Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear Response. Appendix A of JP 3-40 states that “these processes should be practiced during training events and exercises” (JCS, 2019, A-16).

The discussion above highlights the complexity of information-sharing within and across various agencies involved in identifying chemical terrorism threats. Part of the challenge in the communication network lies in understanding each government agency’s roles and responsibilities in CWMDT, which will affect the level and speed of communication. Finding 4-3 underscores the committee’s evaluation regarding information-sharing and coordination based on the documents reviewed and briefing presentations.

FINDING 4-3: The agencies surveyed are broadly aware of each other’s efforts to identify, prevent, counter, and respond to chemical threats, but express

___________________

3 Title 10 of the United States Code specifically pertains to the role and organization of the armed forces, including the Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard. It outlines various aspects of military law, regulations, organization, and responsibilities.

concern that information-sharing and coordination across relevant agencies is incomplete.

4.2 “IDENTIFY” STRATEGY EFFICACY

Reviewing historical chemical threats and attacks provides insight into the effectiveness of the IC, LE, and responding organizations in identifying threats. In the United States, there has not been a chemical terrorist event that has had consequences approaching those observed outside of the United States, like the Aum Shinrikyo nerve agent attacks or the Skripal poisonings. (See Appendix E for a description of international case studies.) A review of more recent examples of domestic chemical threats and attacks provides insight into the threat identification challenges for law enforcement. Generally, U.S. response organizations have been effective in identifying chemical threats, in many cases before plans involving the threats have been discovered or the threats themselves have materialized. However, there have been a few notable cases where LE did not identify a threat before an attack was executed, and the 2018 Skripal poisonings in the UK illustrate a new turn in the actors presenting the chemical threat: from that of terrorist-initiated to use by a great power for targeted assassination. A review of selected events (see Appendices F and G for “Threats Interdicted” and “Threats Manifested” case studies) provides a picture of the IC and LE communities’ level of success in identifying chemical threats.

The proliferation of information, the ease with which it can be accessed—often anonymously—and the high number of potential perpetrators complicates the task of identifying chemical threats (DSB, 2018). In the case of VEOs, the number of individuals involved makes this task more conspicuous. However, in cases of domestic chemical terror, perpetrators often work alone and do not have a significant footprint either in their communities or online. The availability of information online pertinent to synthesizing and dispersing chemical agents makes exhaustive tracking of all potential perpetrators unlikely. These realities are reflected in the DHS Chemical Defense Strategy, which states: “Detection of chemical threats early in the pathway is very difficult since the pathway steps may be concealed within industrial or agricultural production in dual-use facilities, academic or pharmaceutical labs, dark websites, or private homes or warehouses” (DHS, 2019, Pg. 5). Adding to the complexity of before-the-attack identification is the reality that “industrial chemicals and pesticides are readily available for purchase, and are stored in large quantities in thousands of locations, near population centers” (CRS, 2006, Pg. 10).

Further complicating the identification of chemical threats is the emergence of new chemical agents. These are most likely to emerge from state actors engaging in developing new agents, but the intersection of state and nonstate perpetrators makes the utilization of new agents by VEOs conceivable. DoD is actively engaged in identifying new chemical agents, (DASD(CBD), 2020) but communication of this research (which may be classified) to other agencies may be incomplete.

These realities are overtly stated in the National Strategy for countering WMD, viz., (White House, 2018).

CONCLUSION 4-4a: It is impossible to identify and prevent or counter every threat. Overall, the majority of publicly reported domestic plots did not come to fruition between the 1970s through the mid-2010s for a number of reasons.

CONCLUSION 4-4b: FBI, partner LE, and ICs have been effective in identifying and interdicting the majority of domestic terrorist attacks involving chemical materials, which have typically employed conventional toxic industrial chemicals rather than traditional chemical warfare agents, such as sarin. While the FBI has been effective, approaches to identifying chemical threats could be strengthened using a multilens approach from several different agencies that emphasizes augmented communication and coordination between local and state enforcement and IC. In addition, this area would greatly benefit from increased coordination between the IC and technical experts (particularly those with specific expertise in the areas of terrorist motivation and psychology). For example, FBI antichemical terrorism resources focused on identification could be evaluated in the context of current identification strategies employed by other agencies.

RECOMMENDATION 4-4: Existing intelligence community programs should actively seek and incorporate new approaches to identify existing chemical threats (traditional and improvised) and potential emerging threats by terrorist groups. In developing new approaches, program managers should develop strategies that look beyond the traditional terrorism suspects and that augment and leverage skill sets of the USG agencies. For example, scholars of political psychology could work with chemical terrorism experts to create a holistic approach to identifying chemical terrorist groups or similar violent actors outside the traditional suspects. The threat assessments should be improved by reflecting the current times and demographics.

4.3 IMPLICATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGIC SHIFT FROM VEO TO GPC FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF “IDENTIFY”

The shift in emphasis from threats posed by VEOs to state-sponsored threats arising from GPC (DoD, 2018; Caves and Carus, 2021) further complicates the identification task. For example, it is likely that resources for identifying VEO terrorism threats may be shifted toward GPC threats. An intensification of GPC has many potential implications for chemical terrorist threats beyond a possible reduction of resources available to address them. Even if states simply maintain defensive programs against chemical threats, as many do today, those programs have dual-use implications for offensive threats. Therefore, expertise, technology, and materials, including chemical agents, might be illicitly transferred from defensive programs to nonstate actors, as apparently occurred in the biological weapons domain with the so-called Amerithrax case (DOJ, 2010). States might also choose to engage in offensive chemical warfare agent production—as some states, notably Russia, appear to be doing today—and technology, materials, expertise, and/or chemical agents might be illicitly transferred from those programs

to nonstate actors. Further, states, including great powers, might use or support nonstate actors in conducting chemical terrorism. Witting or unwitting involvement of states in nonstate chemical terrorism could dramatically increase the sophistication of such attacks, including the agent employed or the means by which it is delivered. Finally, states, including great powers, might engage in the use of chemical agents in ways that might be categorized as “state terrorism”—both Russia and North Korea have done with targeted attacks in recent years—though the committee recognizes that concept is controversial and difficult to clearly define.

FINDING 4-5: The shift to GPC may change the nature of the threat for new chemical attacks, in that chemical agents, other materials, technology, and expertise may migrate from state actors that engage in either defensive or offensive activities to VEOs. These events could enable VEOs to conduct more sophisticated attacks, with agents and/or with means of delivery not otherwise accessible to them.

RECOMMENDATION 4-5: The NCTC, DoD, DHS, and State Department should review current identification approaches to determine whether shifts in emphasis are required as a result of expanded and augmented VEOs and terrorist capability resulting from the potential migration of chemical agents, other materials, technology, and expertise from state actors to VEOs.

One of the biggest risks from the shift to GPC is compromising the USG’s ability to adequately identify chemical threats. Attacks stemming from terrorists may look, and may be, substantively and substantially different from an attack caused by a state-based program. Therefore, it is important to make clear distinctions on ways to differentiate state-based and terrorist-based chemical threats within the national strategies.

CONCLUSION 4-6: It is unclear if the tactical readiness to implement the reviewed strategies is occurring at the necessary pace to respond to an act of chemical terrorism. Additionally, the shift in strategic focus to GPC may lead to reduced resources for countering acts of terrorism employing WMDs that are perpetrated by VEOs and may impede tactical readiness against chemical terrorist threats, leading to increased risk.

RECOMMENDATION 4-6: The USG should ensure that the identification of chemical terrorism threats is explicitly included in ongoing and future strategies. Chemical terrorism threats should be considered distinct from nuclear nonproliferation, identification of state-based offensive chemical programs, and traditional (non-nuclear-biological-chemical) terrorism.

4.4 SUMMARY

Federal agencies that briefed the committee acknowledged that the number of potential chemical threats that could be used for WMD is large and increasing. While the FBI, in partnership with LE and the IC, has been effective in identifying and interdicting

domestic terrorist attacks involving chemical agents, approaches to identifying these threats could be strengthened. One way to increase capabilities is by using a multilens approach—understanding emerging threats, looking beyond traditional suspects—and increasing coordination and information-sharing between the IC and technical and chemical terrorism experts. Furthermore, the transition toward GPC could alter the risk of new chemical attacks as resources (e.g. chemical agents, technology, and expertise) may transition from state actors to VEOs. As a result, VEOs could potentially carry out more sophisticated attacks using materials and methods that were previously unavailable to them. The committee advised specific programs (NCTC) and departments (DHS, DoD) to review current identification approaches to respond to this potential migration (state actors to VEOs). Because of the shift toward GPC, resources for countering terrorism with WMD may also decrease. Constrained budgetary resources would hinder tactical readiness for implementing the reviewed strategies in response to chemical terrorism. The committee concluded that the USG should include the identification of chemical terrorism threats in ongoing and future strategies, considering them distinct from other nonNBC terrorism threats.

REFERENCES

Casillas, R. P., N. Tewari-Singh, and J. P. Gray. 2023. “Special Issue: Emerging Chemical Terrorism Threats.” Toxicology Mechanisms and Methods 31(4): 239–241.

Caves, Jr., J. P., and W. S. Carus. 2021. The Future of Weapons of Mass Destruction: An Update. National Intelligence University. February, 2021.

Chemical and Biological Defense Program. 2022. Approach for Research, Development, and Acquisition of Medical Countermeasure and Test Products. 2023. https://media.defense.gov/2023/Jan/10/2003142624/-1/-1/0/APPROACH-RDA-MCM-TEST-PRODUCTS.PDF

CRS (Congressional Research Service). 2006. CRS Report for Congress, Chemical Facility Security. August 2, 2006.

DASD (CBD) (Office of the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Chemical and Biological Defense). 2020. Enterprise Strategy. August, 2020.

Deibel, T. L. 2007. Foreign Affairs Strategy: Logic for American Statecraft. New York: Cambridge University Press.

DHS (Department of Homeland Security). 2019. Chemical Defense Strategy. December 20, 2019.

DHS. 2013a. National Infrastructure Protection Plan (NIPP) 2013 Partnering for Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience.

DHS. 2013b. National Infrastructure Protection Plan (NIPP) Fact Sheet 2013: Partnering for Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience. https://www.cisa.gov/sites/default/files/2022-11/NIPP-Fact-Sheet-508.pdf

DHS. 2022. The DHS Strategic Plan. Fiscal Years 2020–2024. https://www.dhs.gov/publication/department-homeland-securitys-strategic-plan-fiscal-years-2020-2024.

DoD (Department of Defense). 2014. Department of Defense Strategy for Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction. June 2014.

DoD. 2018. National Defense Strategy of the United States of America: Sharpening the American Military’s Competitive Edge.

DoD. 2018. National Strategy for Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction and Terrorism. Presidential Directive, December, 2018. https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/DCPD-201800841.

DOJ. 2010. “Amerithrax Investigative Summary.” https://www.justice.gov/archive/amerithrax/docs/amx-investigative-summary.pdf; Bunn and Sagan (eds) Insider Threats (book), chapter on Amerithrax.

DOS (U.S. Department of State). 2022. Compliance with the Convention on the Development, Production, Stockpiling, and Use of Chemical Weapons and on Their Destruction Condition (10)(C) Report. April 2022.

DSB (Department of Defense Science Board). 2018. Task Force on Deterring, Preventing, and Responding to the Threat or Use of Weapons of Mass Destruction. May 2018.

HASC (House Armed Services Committee). 2021. Statement of Vice Admiral Timothy G. Szymanski, U.S. Navy Deputy Commander United States Special Operations Command Before the House Armed Services Committee Subcommittee on Intelligence and Special Operations. May 04, 2021. https://www.congress.gov/117/meeting/house/112537/witnesses/HHRG-117-AS26-Wstate-SzymanskiT-20210504.pdf.

Hersman, R. K. C., S. Claeys, and C. A. Jabbari. 2019. “Rigid Structures, Evolving Threat, Preventing the Proliferation and Use of Chemical Weapons, Center for Strategic and International Studies.” December 2019.

JCS (Joint Chiefs of Staff). 2019. Joint Publication 3-40. Joint Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction. November 27, 2019.

NPR (National Public Radio). 2022. “Why Did Tucker Carlson Echo Russian Bioweapons Propaganda on His Top-Rated Show?” https://www.npr.org/transcripts/1089530038.

RAND Corporation. 2007. Enlisting Madison Avenue: The Marketing Approach to Earning Popular Support in Theaters of Operation. RAND.

Rotolo, Jason. 2022. FBI, Briefing to the Chem Threats Committee. August 11, 2022. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 34(4) (August): 385–393.

Savage, T. 2022. FBI Policy Program, Briefing to the Chem Threats Committee. August 11, 2022.

Trump, D. 2017. National Security Strategy of the United States of America, National Strategy for Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Terrorism.

U.S. Joint Forces Command. 2009. Commander’s Handbook for Strategic Communication and Communication Strategy. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA544861.pdf.

USSOC (United States Special Operations Command). Tip of the Spear. June, 2021. https://www.socom.mil/TipOfTheSpear/USSOCOM%20Tip%20of%20the%20Spear%20June%202021(Web).pdf.

White House. 2018. National Strategy for Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Terrorism. https://www.hsdl.org/?view&did=819382.

This page intentionally left blank.