Chemical Terrorism: Assessment of U.S. Strategies in the Era of Great Power Competition (2024)

Chapter: 6 Adequacy of Strategies to Respond to Chemical Terrorism

6

Adequacy of Strategies to Respond to Chemical Terrorism

Summary of Key Findings, Conclusions, and Recommendations

FINDING 6-1: The current compilation of U.S. strategies, operational plans, resources, and interagency agreements has yielded a network of first responder communities capable of robust response to most industrial and transportation chemical incidents regardless of their cause. Existing chemical accident first responder capabilities (e.g., for industry and transportation) are also useful for chemical terrorism scenarios.

FINDING 6-2: Tools (e.g., Wireless Information System for Emergency Responders (WISER, ACTKNOWLEDGE) that seek to bridge and enable better chemical, biological, radiation, and nuclear (CBRN) response communication across federal, state, local, territorial, and tribal (SLTT) organizations have been discontinued.

FINDING 6-3: The U.S. Global Deterrence Framework and other strategies involving the whole of government sharing often include representatives from the first responder and export control communities. This inclusion ensures that the USG will receive timely, up-to-date threat assessments and can make changes to their tactics, techniques, and protocols.

CONCLUSION 6-4: The National Response Framework (NRF) has adequately addressed chemical terrorism categorically under the Emergency Support Function #10: Oil and Hazardous Materials Response.

FINDING 6-5: With respect to responding to chemical terrorism, the hierarchy of U.S. strategies, frameworks, and other guidance is complex; accordingly, their translation into operational practice may be challenging.

FINDING 6-6: With respect to the NRF, the first response communities, civil defense organizations, Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Department of Defense (DoD), and medical communities are continuing to exercise communication channels and are bringing awareness of such channels to relevant users. The number of potential venue targets is vast and response exercises simulating chemical attacks are being integrated into doctrine to provide experience and information to as many SLTT responders as possible.

RECOMMENDATION 6-6: Considering the complexity of the chemical threat space and U.S. government (USG) coordination required for an effective response to a chemical event, the committee recommends continuing a robust program of interagency exercises and trainings that practice communication and resource sharing.

The United States has well-defined authority and organizational constructs for emergency response, including large-scale and chemical terrorism response. The extensive multi-agency response capabilities of the United States are complexly governed, coordinated in policy, sufficiently connected to intelligence activities, and sufficiently capitalized; however, a mass casualty, multipoint, or cross-jurisdiction incident could have an impact beyond the SLTT capabilities. The committee has identified opportunities for improvements, but in the context of a great power competition (GPC)-focused national strategy, the committee found it difficult to recommend dramatic investments or changes. Maintenance, exercise, and integration of modernized response capabilities remain essential.

6.1 ANALYSIS OF STRATEGIES FOR “RESPONDING” TO WMDT CHEMICAL THREATS

Using our robust methodology (described in Chapter 3) the committee reviewed the strategy documents listed in Box 6-1 focusing on response to chemical terrorism. These documents contained highly variable content relating to the response aspects of combating chemical terrorism. The DHS and DoD documents were most useful for response. Most of the strategy documents espoused a coherent strategy or set of strategy elements (i.e., comprising a combination of a well-defined goal with a corresponding definition of success, as well as at least one policy, plan, and/or resource allocation designed to meet the goal(s)). The exception to this was DoD Directive 2060.02, which

BOX 6-1

Strategy Documents Reviewed by Committee for “Response” Analysis

- The National Strategy for Countering WMD Terrorism

- The DHS Chemical Defense Strategy

- Chemical and Biological Defense Program (CBDP) Enterprise Strategy

- DoD Strategy for Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction (2014)

- JP 3-40: Joint Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction

did not provide clear definitions of success for its goals of “Dissuade, deter, and defeat actors concern and their network[…]. Manage [weapons of mass destruction] WMD terrorism risks from hostile, fragile or failed states and safe havens.[… Or] [l]imit the availability of WMD-related capabilities.”

With respect to whether the existing strategies, as encompassed by the above-mentioned strategic documents, are adequate to address both the current and emerging threat of chemical terrorism, most of the elements that we believe are essential to accomplish this task are reflected in the strategies. The matrix described in Chapter 3 (page 62) indicates these elements and whether or not each is addressed by the strategies.

6.1.1 Committee Definition of Adequacy: Response

For this study, response is defined as, “in countering weapons of mass destruction, the activities to attribute responsibility for an event: minimize effects, sustain operations, and support follow-on actions.”

In the opinion of the committee, the concept of adequacy for strategies for responding to chemical terrorism will include elements that sufficiently address the following questions:

- Does the U.S. strategy adequately enable response capabilities (e.g., operations coordination, information-sharing, medical support, and others) that minimize potential impact on life, property, and the environment?

- Is the strategy for responding to chemical terrorism and are the resources devoted to implementing the strategy aligned with the priorities of the United States (e.g., protecting the homeland, ensuring economic security, maintaining military strength) and aligned with the nation’s risk posture?

- Does the strategy anticipate emerging threats by suggesting the scientific research and interagency relationships necessary to respond to future threats?

Overall, the committee found the strategies to be at least adequate, specifically, DHS Chemical Defense Strategy, CBDP Enterprise Strategy, and JP 3-40: Joint Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction.

6.1.2 Response Capabilities: Known vs. Unknown Threats

The committee believes that key elements to a prompt, effective first response are rapid availability of situational awareness, technical information, and physical assets. Hence, the focus is on the adequacy and timeliness of the communication chain as well as the adequacy of the content of the information conveyed by federal agencies to the first responders during a chemical event. After reviewing multiple briefings and evaluating the U.S. strategy documents, the committee observed that several federal agencies could be involved with information flow to first responders before, during, and after a chemical event, either accidental or terrorist. These agencies include DHS/Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA), DHS/Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), International Association of Fire Chiefs (IAFC), Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) NRP, local authorities, and others.

The challenges and adequacy of response to a chemical weapon of mass destruction (CWMD) incident vary greatly depending on whether the incident involves known or unknown threats.

Known, Existing Threats

It should be noted that the adequacy of a successful response that minimizes the effects of such an event is a function of the adequacy of Emergency Preparedness. To that extent, response to a chemical event at an existing threat location is more manageable as the nature of the threats (chemicals) are known, risks have been clearly identified and mitigated as much as possible, and the response teams are known (appropriate SLTT responders). Often the response teams also have experience in addressing these threats through regular training, tabletop drills, and exercises. Further, since the requisite response resources are well known to the responders, staging of response, countering resources, and equipment can be preplanned and made readily available during the event.

Unknown Threats

However, a chemical event anywhere else in the homeland, and without prior notice, presents challenges as the chemical nature and the amounts are unknown and therefore the risks to life are unknown at the outset. The immediate success of response in this case depends primarily on the first responders at the SLTT levels and their ability to rapidly reach out for appropriate additional resources when necessary. It should be noted that the U.S. Military response is not automatically triggered by a chemical incident (see Appendix A, USG Strategy Documents Provided to the Committee). Further,

the USG response would only be required when SLTT authorities are overwhelmed or require specialized expertise (see page 111, USG Strategy Documents).

The 2018 National Strategy for Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Terrorism (White House, 2018) updated several approaches including strengthening outreach to responders by establishing lines of communication with federal agencies that greatly improve coordination before, during, and after an event. It also stated that providing training and equipment to SLTT entities will be continued with the aim of “creating self-sustaining capabilities that are not continually dependent on Federal assistance.” (White House 2018). This places a burden on the first responders who have varying degrees of skills and resources and elevates the importance of training, education, availability of response resources, and a well-rehearsed and thoroughly familiar chain of communication and command.

6.1.3 Accidental or Intentional Chemical Incidents

In addition to understanding types of threats (unknown or known), whether an event is accidental or intentional factors into an adequate response. Approximately 800,000 hazardous shipments move every day in the United States, which equates to more than 3 billion tons of hazardous materials transported every year. During these material movements, more than 25,000 hazardous materials (hazmat) incidents occurred, which in the period of 2012–2022, caused less than 100 recorded fatalities and less than 2000 injuries (DOT, 2023). When accidents occur, first responders have tools, training, and interagency agreements generally adequate for protecting the U.S. population, themselves, and the environment. Specifically, the EPA’s Emergency Support Function (ESF) #10-Oil and Hazardous Materials Response states that the EPA will provide: federal support in response to an actual or potential discharge and/or uncontrolled release of oil or hazardous materials when [ESF is] activated. (p 1)

The EPA is the primary agency that coordinates support from several other agencies including the Department of Agriculture, Department of Commerce (DOC), DoD, Department of Energy (DOE), Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), DHS, Digital Object Identifier (DOI), Department of Justice (DOJ), State Department, Department of Transportation (DOT), General Services Administration, and Nuclear Regulatory Commission (EPA, 2008). The thirteen support agencies should contain the expertise necessary for the breadth of chemical incidents and the ability to reach out when additional resources or knowledge is needed.

The DHS 2019 Chemical Defense Strategy treats response to chemical terrorism and accidental release equivocally. The document states: The Nation faces a complex threat landscape, especially from the evolving nature of the chemical threat, whether from accidental release or terrorist attack.

A chemical terrorism event involving chemical weapons could pose challenges beyond the technical capabilities of first responders to promptly recognize or mitigate. The Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Publication 3-41 Published September 9, 2016, “provides joint doctrine for military, domestic, or international response to minimize the effects of a CBRN incident.” (Pg. 3). The fundamentals of the military’s role in response to

WMD are covered in Joint Chiefs of Staff Joint Publication 3-40. The specific definitions and counts of chemical terrorism events vary. Per guidance from the study sponsor to the committee and the Statement of Task (SOT), the chemical terrorism incidents for the committee’s focus are those directed at U.S. assets, continental U.S. (CONUS) or outside the contiguous U.S. (OCONUS) excluding those that are state-sponsored. None of the databases mentioned below categorize incidents in ways that are exactly aligned with committee’s tasking, making meaningful comparisons among data sets difficult. The University of Maryland Global Terrorism Database (START, 2022) describes about 30 acts of terrorism in the United States involving chemicals over the 50-year period 1970–2020. Using different inclusion criteria, the profiles of incidents involving chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear and nonstate actors (POICN) Database describes 68 chemical terrorism cases (and 36 uses) from 1990–2020. Despite difficulty comparing incident counts, and timeframes, chemical terrorism is historically a miniscule portion of chemical release events that require first responders.

In sum, the vast majority of chemical incidents in the United States are not terrorism; thus, the vast majority of first responder actions associated with chemical releases are from accidents, transportation incidents, or the results of natural phenomena—not responses to terrorist events. Thus, local first responders would respond to a chemical terrorism event even if the origin or motivation of the chemical release were unclear: accidental, sabotage, or terrorist. When necessary, intelligence assets are engaged.

FINDING 6-1: The current compilation of U.S. strategies, operational plans, resources, and interagency agreements has yielded a network of first responder communities capable of robust response to most industrial and transportation chemical incidents regardless of their cause. Existing chemical accident first responder capabilities (e.g., for industry and transportation) are also useful for chemical terrorism scenarios.

6.1.4 Advance Detection Capabilities

DHS has recognized that to assess the impact of a chemical event in real-time, the agency would need chemical modeling programs, which would also provide valuable information to first responders—a key aspect to improving situational awareness and understanding physical assets. CISA created Jack Rabbit (DHS, 2021), which is a multiagency initiative (DHS, EPA, DoD) aimed at providing data and information related to chemical threats through field studies and experiments (e.g. laboratory experiments, wind tunnel experiments, and urban dispersion modeling). Jack Rabbit III, in particular, focuses on modeling tools and detection technologies to better understand and monitor chemical threats such as a large-scale ammonia release via dispersion (plume size, dispersion rate, ammonia concentration). Furthermore, the modeling is expected to improve the following:

- planning for release incidents;

- emergency response;

- mitigation measures to reduce the impact on affected populations and infrastructure;

- guidance and data for emergency response procedures; and

- validation of protective action distances.

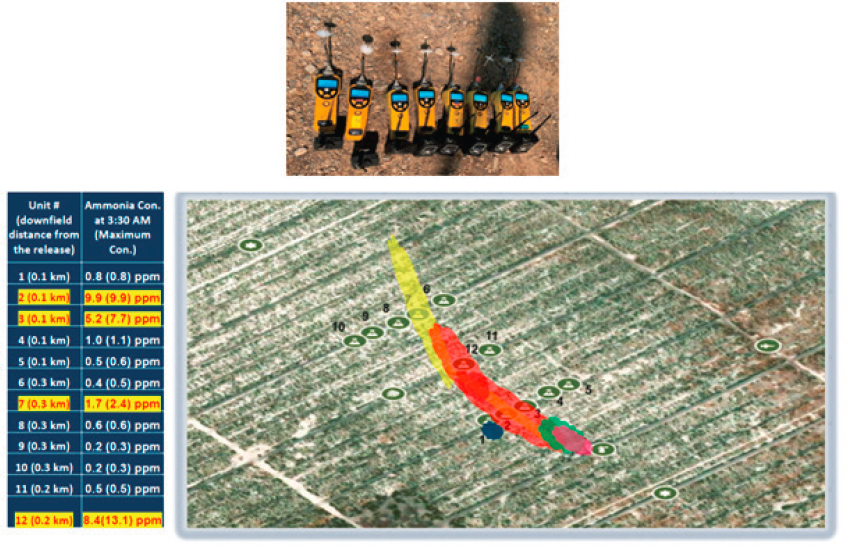

Figure 6-1 is an example of using a portable gas detector, miniRAE, to measure and map the concentration levels of ammonia at varying distances from the chemical’s point of release in real time. Coupling this capability with a communications network for first responders, such as FEMA’s ChemResponders (ChemResponder Steering Committee, 2020), will support emergency response decision-making. Other advanced technologies—high-definition video recording equipment, drones, hyperspectral imaging technologies, and others—are being explored for real-time applications as a way to provide adequate information to increase first responder’s safety on-site (e.g., using the appropriate protective equipment).

The committee also recognizes that information from chemical release modeling, such as Jack Rabbit, and the subsequent information flow to first responders is agnostic to the motivation behind the chemical release: terror, sabotage, or accident. If the chemical(s) released have known physical properties, such modeling information is likely to be more accurate than with an unknown.

SOURCE: Fox and McMasters, 2021.

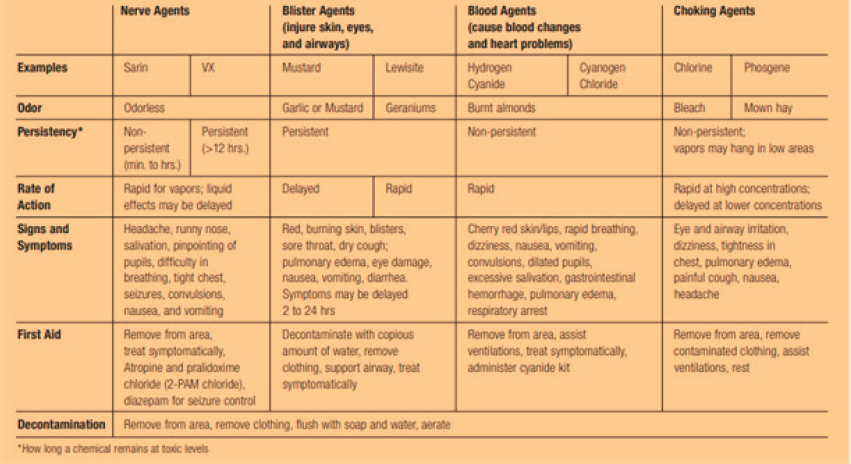

6.1.4a Military Preparedness: Identification or Recognition of a Chemical Weapons Event

For many chemical terrorism events, identification of the chemical(s) involved is straightforward as readily available documentation such as site chemical inventories or shipping manifests can be used to identify the potential chemicals involved. Figure 6-2 shows the different types of chemical agents developed for military use, their chemical properties, and the signs and symptoms of a person who is exposed. Should a terrorist bring a chemical to the location of an attack, characterization of the threat could take longer and would be based on physical observations, observed symptoms, and monitoring technologies. While the committee believes chemical weapon use to be unlikely for a terrorism event, there is a history of chemical agent attacks (discussed below), and the consequences could involve significant loss of life in the first responder community.

The initial recognition or identification of chemical weapons in a terrorist attack may be slower than desired as first responders may not be trained in recognizing symptoms of chemical agent exposure. Without prior indication, the mindset of the first responders will not be focused on a potential chemical weapon attack. For example, the symptoms of a chemical attack may be similar to those of other medical conditions or chemical exposures. Exposure to a nerve agent can produce a seizure response, followed by cardiac arrest, as can multiple medical conditions. First responders commonly encounter such symptoms among the general population, but only extremely rarely if ever are those symptoms caused by nerve agent exposure.

This situation is in marked contrast to battlefield scenarios that are considered by the U.S. Army, where the use of chemical weapons is possible and may have a reasonable likelihood of occurring. Accordingly, the Army is well equipped to identify

SOURCE: DHS, 2006.

the presence of a chemical warfare agent in the environment. Near real-time detectors have matured and are common on military equipment. For example, the MINICAMS gas chromatograph system has been in use for more than a decade and is deployed on Army platforms. However, civilian first responders may be unlikely to have access to this type of measurement equipment, and even if it was accessible, would not likely have the budget to procure devices, or the personnel bandwidth to accommodate training to enable operation.

First responders will be unable to understand the extent of contamination, a situation that will be exacerbated by the inability to conduct any meaningful surface characterization. This situation affects first responders’ decision-making regarding appropriate personal protective equipment. Semivolatile or low-volatile agents will largely partition to surfaces in the exposed environment, which means that inhalation risks from these agents are decreased and that the risk of toxic exposure by dermal contact is elevated.

The experience of the first responders in the Skripal poisoning incident illustrates this point. The risks that are illustrated include likely dermal contact with A234 or something like it, producing extremely toxic responses in the Skripal case. First responder Nick Bailey was exposed, reportedly when wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) (see Appendix E for “Skripal Poisoning” case study).

The Army at the Chemical Biological Center (CBC) is currently engaged in developing spray reagents that can identify agent contamination on skin surfaces, which would likely work on other surfaces as well. However, the spray reagents may not be applicable to large areas, and furthermore are relatively early on in the research and development pipeline; i.e., it may be years before these technologies are available for characterizing contamination on skin in military environments, and even longer for civilian use.

6.1.5 First Responder Input

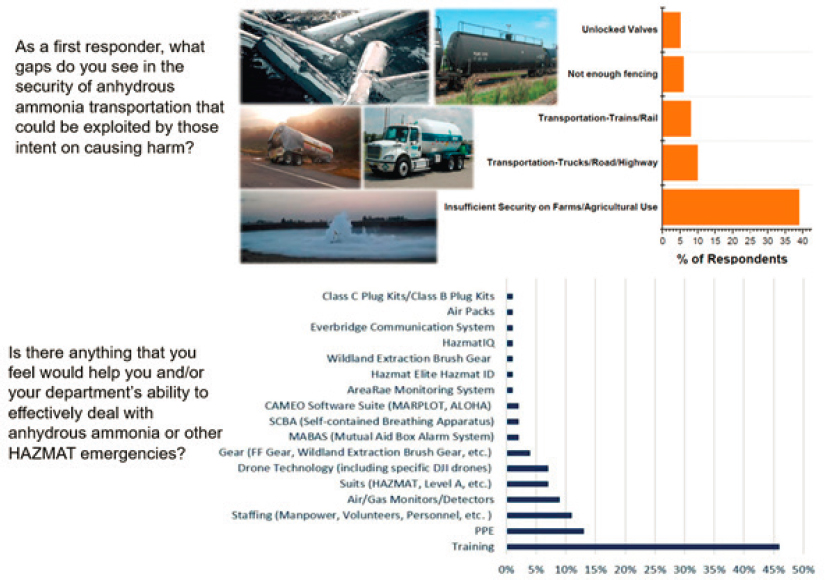

A major component for creating a robust strategy is to ensure critical information is collected and included from the first responder community. The committee recognizes that some initiatives, like Jack Rabbit, have included first responder input in their study of safety risks of transporting ammonia—an essential chemical as a fertilizer and in fertilizer production. The transportation sector faces a large safety risk in its role of shipping ammonia across the country: chemical hazard spills or attacks at handoff points. In these incidents, first responders are at the highest risk. For example, police may lack training and enter a scene of an accidental release, or responders may not have the correct PPE. To ensure that the safety needs of this community are met, Jack Rabbit’s questionnaire asked for input on where first responders see security gaps around anhydrous ammonia (Figure 6-3, top) as well as what equipment their department would need to effectively respond to an ammonia emergency (Figure 6-3, bottom).

CISA also recently released the SAFECOM Nationwide Survey (SNS), as a way to collect data from target participants, to identify gaps, and inform the program’s strategic priorities for improving the nation’s emergency communication systems (CISA.gov, 2018). SNS is most interested in gathering information from emergency communication

SOURCE: Fox and McMasters, 2022.

centers, emergency management, law enforcement (LE), emergency medical personnel, fire and rescue professionals, and other organizations that use emergency communications technology to ensure public safety. In summary, these types of input from relevant stakeholders in the response community will also eventually shape the direction of risk assessments (e.g., type of chemical threat characterized, experimental setup, types of tools to develop) as will be described in Section 6.1.6.

6.1.5a Access to Intelligence

During briefings, the committee learned that it is possible that there is information available that would be most beneficial to the first responders and reduce causalities; however, it cannot be transmitted due to the classification status of the information (see Appendix A). It is recognized that the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC) created a mobile app, ACTknowledge, that shares unclassified counterterrorism reports, analysis, training resources, and alerts to users. This app was created based on the recommendation of the 9/11 Commission as a way to integrate and share information

related to strategic planning and government analysis across SLTT and federal partners.1 However, as of January 2023, ACTknowledge was discontinued. The Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) also created a First Responder Toolbox, which is an ad hoc, unclassified, and For Official Use Only(FOUO) reference aid intended to promote counterterrorism coordination among federal, SLTT government authorities, and private sector officials to coordinate in deterring, preventing, disrupting, and responding to terrorist attacks. First Responder Toolbox could serve as a potential indicator of a chemical or biological attack (Joint Counterterrorism Assessment Team (n.d.).

Under the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the National Library of Medicine hosted the mobile app and web-based platform: Wireless Information System for Emergency Responders (WISER). This was designed to provide first responders with quick access to critical information during hazardous material incidents and other emergencies. The app included physical properties of the chemical, health effects, safety protocol, and other protective measures. It had emergency step-by-step response guides published by various agencies such as DOT. WISER was discontinued in February 2023, although NLM listed alternative publicly available sources on its website (NIH/NLM, 2023).

The committee also recognizes that the FBI is actively engaged in fostering communication with state and local first responders, including the National Guard, and industry (Savage, 2022); however, it is not clear whether the outreach is comprehensive or systematic. The risk is that an event could occur in an area where first responders would not be aware of, or in communication with, FBI personnel or capability.

Overall, the committee assesses that there is not an obvious systematic means of communicating information to responders. Getting information to this community can be a significant challenge and represents a vulnerability.

FINDING 6-2: Tools (e.g., WISER, ACTknowledge) that seek to bridge and enable better chemical, biological, radiation, and nuclear response communication across federal and SLTT organizations have been discontinued.

FINDING 6-3: The U.S. Global Deterrence Framework, and other strategies involving whole-of-government sharing, often include representatives from the first responder and export control communities. This inclusion ensures that the USG will receive timely, up-to-date threat assessments and can make changes to their tactics, techniques, and protocols.

6.1.6 Risk Assessments

Risk assessments are important for steering the direction of strategies aimed at enhancing response to chemical terrorism. The EPA’s Risk Management Program (RMP) was established to prevent and mitigate the consequences of chemical accidents. Critical facilities are required to periodically submit information to EPA that includes

___________________

1 NOTE: ACTknowledge was discontinued in January 2023.

the facility’s hazard assessment, accident prevention mechanisms, and emergency response measures. This plan provides local fire, police, and emergency response personnel with valuable information to prepare for and respond to chemical emergencies in their community.

Several programs within DHS develop different types of assessments at the local, state, and national levels. Every three to five years, FEMA releases the Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment (HIRA) and Threat and Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment (THIRA); both guidance documents address issues at the state and local levels, respectively.

Developments of THIRA, particularly in urban areas, effectively ask local communities to characterize risks and then use core capabilities to translate risks to required levels of capability. Planning committees, including firefighters, police, and paramedics, are asked to look across specific threats and decide on threat-agnostic capability and performance requirements. They are designed to drive a collaborative local planning process. Furthermore, when a jurisdiction assesses risks, they are explicitly considering the chemical terrorism risks, thus as THIRA evolves, appropriate attention to chemical terrorism would be given, especially in the context of chemical precursors.

Response communities are less engaged with the HIRA because these documents focus more on program development and evaluation at the state level. Additionally, the Probabilistic Analysis of National Threats and Risk Program (PANTHER) under CISA develops risk assessments often at the request of the FBI and other agencies. Within PANTHER, there is an emphasis on chemical risk assessment, much of which is at the FOUO level or higher.

At the national level, DHS and the intelligence community (IC) have developed the Strategic National Risk Assessment (SNRA). National-level risk assessments inform national strategies, just as THIRA would inform strategies at the state level. The linkages exist, but strategy ultimately comes from policy directions and prioritizations.

Our risk assessments consistently show that even though nuclear and biological agent threats have the ability for catastrophic effects, the chemical threat has a much higher probability of occurring. So the chemical threat consistently shows up at or above the risk levels of the other threats but is consistently underfunded compared to the other threats. The chemical threat is not recognized for the risk that it poses (Fox, 2022).

6.1.7 Top-Down and Bottom-Up Information Flow

All of the briefings received by the committee from various agencies responsible for some part of antichemical terrorism activities (see list of briefers, Appendix A) demonstrated a clear understanding looking upstream to current authorities, strategies, policies, and laws governing internal agency responsibilities. Agencies understood their charter, authority, and responsibilities. However, less clear to the committee is how the requirements systematically flow downstream from higher-level policy to subsidiary organizations and finally to first responders.

For example, the committee identified that the roles and responsibilities of EPA and DHS/FEMA officials as well as their chains of communication are convoluted, which

could lead to confusion at the local level. This lack of clarity could result in a slower response to a chemical incident or attack. The description in Box 6-2 highlights the complexity of understanding how strategies are deployed from a high-level (National Incident Management System [NIMS]) to the practitioner level: first responders.

The NRF prioritizes collaboration with the private sector and nongovernment organizations (NGOs), locally driven incident management, and active readiness to stabilize community lifelines and enable rapid and safe restoration of services in severe incidents.

The 4th edition of the NRF describes new initiatives that leverage existing networks and integrate business interests and infrastructure owners and operators into emergency management.

FEMA’s approach has focused on training State and local responders by granting awards to enhance the capability of local response entities and issuing guidance to the local officials and first responders. FEMA notes that

elected and appointed leaders in each jurisdiction are responsible for ensuring that necessary and appropriate actions are taken to protect people and property from any threat or hazard. When threatened by any hazard, citizens expect elected or appointed leaders to take immediate action to help them resolve the problem. Citizens expect the government to marshal its resources, channel the efforts of the whole community—including voluntary organizations and the private sector—and, if necessary, solicit assistance from outside the jurisdiction (FEMA, 2010, Pg. 13).

The NRF identifies various elected officers like governors, state emergency officers, and other agencies with various capabilities but does not define clear roles and responsibilities.

NRF also provides that in the event the state and local LE capabilities are overwhelmed by an attack incident, the DOJ is to assume the responsibility for coordinating federal LE activities to ensure public safety and security.

It is worth emphasizing that the NRF does not present any component of the Federal government—DHS, DoD, DOJ, or otherwise—as the prescribed owner or ‘lead response agency’ for any type of incident by default. ESF Annexes of the NRF lay out support functions that a federal agency may be called upon to assist (such as transportation, fire suppression, or energy). Similarly, the Incident Annexes of the NRF specify coordinating and cooperating federal agency roles within a narrow set of specific incidents. Neither Annex, however, supersedes the key principles of the NRF itself, which spell out a flexible, locally driven response concept, whose expansion to the federal “tier” occurs at the prompting of overwhelmed local and state officials.

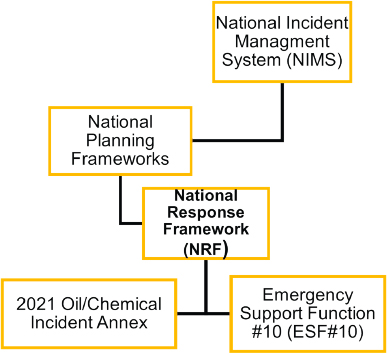

CONCLUSION 6-4: The NRF has adequately addressed chemical terrorism categorically under the ESF #10: Oil and Hazardous Materials Response.

While biological and nuclear/radiological incidents have dedicated NRF Incident Annexes, incidents involving the release of a toxic chemical would ostensibly be captured by some combination of ESF#10 “Oil and hazardous materials response” (coordinated by the EPA), and the Terrorism Incident Law Enforcement and Investigation Annex (coordinated by the DOJ/FBI). Because of this ambiguity, of all potential

BOX 6-2

Relationship of Response and Preparedness Documents

The main framework employed by DHS/FEMA to coordinate and respond to emergencies, natural disasters, or terrorist events is the National Incident Management System (NIMS), which provides a common set of principles, practices, and procedures to facilitate incident management and response while maintaining the flexibility to address a breadth of incidents. It is designed to ensure interoperability and compatibility among different organizations involved in the emergency response; however, it is written at a high level. Within this framework, shown in Figure 6-1-1, are the National Planning Frameworks, where the NRF is located. Two documents related specifically to responding to chemical incidents are included under the NRF: ESF#10 and the Oil/Chemical Incident Annex.

SOURCE: FEMA, 2021.

ESF #10, as described in Section 6.1.3, details federal support for an uncontrolled release of hazardous material. FEMA works in conjunction with other federal agencies, like EPA, and partners to coordinate ESF #10 activities during a chemical incident. Additionally, the ESF applies whether a presidential emergency has been declared under the Stafford Act (see Box 6-3), or not. Furthermore, the 2021 Oil/Chemical Incident Annex details important oversight, resourcing, laws, regulations, presidential directives, and federal response coordination. Although the word “chemical” is included in the title, sections of the Annex cover topics specific to oil spills, but it does not have sections specific to chemical spills or releases.

In summary, NIMS provides the overarching framework for incident management and coordination, while ESF #10 and the Annex operate within the NIMS structure to address specific hazardous materials incidents, including chemical incidents. The mechanisms employed are coordination, technical expertise, and support in collaboration with other response entities (i.e., first responders).

SOURCE: FEMA, 2021.

BOX 6-3

Stafford Act

The Stafford Act, officially known as the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act, is a United States federal law that was enacted in 1988. This statute provides the legal framework for the response to, and recovery from, natural disasters, acts of terrorism, and other catastrophic events.

This law authorizes the President of the United States to issue a declaration of a major disaster or emergency, which then enables the federal government to coordinate and provide assistance to SLTT governments, as well as certain private nonprofit organizations and individuals affected by the disaster or emergency. The assistance provided under the Stafford Act can include financial aid, grants, loans, and other forms of support to help with response, recovery, and rebuilding efforts.

FEMA plays a central role in implementing the provisions of the Stafford Act. FEMA works in collaboration with various federal, and SLTT agencies to coordinate disaster response and recovery operations, provide technical assistance, and administer financial assistance programs.

SOURCE: Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act, PL 100-707 (November 23, 1988). see https://www.fema.gov/robert-t-stafford-disaster-relief-and-emergency-assistance-act-public-law-93-288-amended.

WMD terrorism scenarios, chemical incidents appear to have the greatest potential for interagency confusion, particularly in the early response stages wherein an accidental hazmat release may be indistinguishable from an act of chemical terrorism.

The Chemical Security Analysis Center (CSAC) generates a wealth of information on chemical threats, however vertical communication downward to the first responders currently occurs on an ad hoc basis. Relationships have been developed with entities like the Center for Domestic Preparedness (part of FEMA), the National Association of Fire Chiefs, the Ammonia Production Association, the Railroad Transportation Association, and other organizations. The purpose of these relationships is to transmit information that first responders would need, to enable them to recognize a chemical terrorist event. An example of successful communication stems from the results of the Jack Rabbit exercises, which are widely communicated. However, there does not appear to be a systematic approach for communication with the broad spectrum of first responders. Consequently, if there is an incident, it can be well after the fact that CSAC is involved. This situation is exacerbated by the fact that it is difficult to transmit timely information to responders if the information is classified or sensitive (see section 6.1.5 for more details).

Overall, chemical terrorism events (and any CBRN event) involve authority flowing among agencies and complex incident characterization. Impediments to this flow could slow response, delay event characterization, increase casualties, and confuse crime scene preservation.

FINDING 6-5: With respect to responding to chemical terrorism, the hierarchy of U.S. strategies, frameworks, and other guidance is complex; accordingly, their translation into operational practice may be challenging.

6.1.8 Emergency Response Coordination

The committee learned from briefings that while information does flow down to first responders from individual federal agencies; coordination among the different organizations can be improved to ensure first responders receive the needed information. Table 6-1 describes several federal agencies and their respective programs that would benefit from more coordination.

In 2006, Congress too acknowledged that there was a need for stronger coordination and national leadership to address gaps in emergency responders’ abilities to communicate across jurisdictions and functions. During that time, Congress authorized the establishment of the Emergency Communication Preparedness Center (ECPC) (Section 671, Pub. Law No. 109-295), also known as the “Post-Katrina Emergency Management Reform Act.” ECPC is a federal interagency within CISA. Its strategic priorities include increasing efficiencies at the federal level through joint investment and resource sharing and improvements in alignment of strategic and operational emergency communications planning across levels of government. In reality, there appears to be a patchwork of multiple agencies involved in providing training and resources in an uncoordinated manner to local first responders thereby enhancing the risk of critical gaps.

Further, there is the Nationwide Communications Baseline Assessment (NCBA) to evaluate the nation’s ability to communicate during a variety of response operations; there seems to be a lack of a clear and timely transmission pathway for critical information that needs to be provided to first responder during a CWMD event. In an exploration of the reasons for this, it was clear that there are too many bureaucratic barriers that block the transmission of much-needed information in a timely manner.

ECPC considers various public communications technologies such as Next Generation 9-1-1, land mobile radio, long-term evolution, and others as a way to align strategic and operational emergency communications (interoperable and operable) across the levels of government. As stated in its 2019 Annual Strategic Assessment (ECPC, 2021. Pg. 2),

The ECPC works to address gaps in emergency communications and enables emergency response providers and relevant government officials to continue to communicate in the event of natural disasters, public health emergencies, acts of terrorism, other man-made incidents, and planned events.

CISA also developed the National Emergency Communications Plan (NECP), which is a strategic plan to strengthen and enhance emergency communications capabilities in the United States. NECP aims to maintain and improve emergency communications capabilities for emergency responders and serves as the nation’s roadmap for ensuring emergency communications interoperability at all levels of government. This plan establishes a shared vision for emergency communications and assists those who plan for, coordinate, invest in, and use operable and interoperable communications for response and recovery operations. This includes traditional emergency responder disciplines and other partners from the whole community that share information during incidents and planned events.

With respect to addressing chemical attacks specifically, the WMD Strategic Group Consequence Management Coordination Unit (WMDSG’s CMCU) coordinates with FEMA through its office CBRN office. Recently, this office was replaced by the Office of Emerging Threats (OET) (FEMA, n.d.), where CBRN responsibilities are still retained. This type of collaboration provides strategic advice and recommended courses of action for ongoing LE and counterterrorism operations. The FBI has designated WMD coordinators in its 56 field offices with the idea that building strong working relationships in place makes for a smoother response to a chemical incident. They routinely host WMD workshops to train first responders in recognizing the use of WMD during the initial stages of an incident. During these exercises, trained agents and biowarfare scholars share lessons learned from past events. These activities provide an advanced, hands-on understanding of the hazards posed by WMD and increase first-response preparations to handle a WMD incident. The WMDSG’s CMCU serves as a link between FBI-led crisis response and FEMA-led consequence management (CM) operations. Interagency coordination is exemplified through this initiative. In sum, the establishment of the WMDSG leads to improved federal interagency coordination for WMD-related terrorist threats and incidents.

After a chemical terrorism event, the FBI plays a significant role in response since they are the lead organization for WMD investigation. Addressing the language in this

committee’s SOT, “responding to chemical terrorism incidents to attribute their origin” the FBI is well positioned organizationally to attribute origin through its Criminal Investigation Division, Directorate of Intelligence, Weapons of Mass Destruction Directorate (WMDD), Counterterrorism Division, and Counterintelligence Division (FBI.gov; U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2023).

As shown above, the FBI appears to have a strong response system and DHS also has a robust training program for responding to chemical attacks. These agencies make clear efforts to have resources and programs available for on-the-ground responders. Response exercises that are integrated into the overall exercise programs are one way to ensure robust capability. Continuing chemical exercises will strengthen hazards preparedness routine. Lastly, in a resource constrained environment, response exercises will remain a necessity because they frequently test the response-coordinated groups’ ability to pivot and operate in a dynamic environment.

FINDING 6-6: With respect to the NRF, the first response communities, civil defense organizations, DHS, DoD, and medical communities are continuing to exercise communication channels and are bringing awareness of such channels to relevant users. The number of potential venue targets is vast and response exercises simulating chemical attacks are being integrated into doctrine to provide experience and information to as many SLTT responders as possible.

RECOMMENDATION 6-6: Considering the complexity of the chemical threat space and USG coordination required for an effective response to a chemical event, the committee recommends continuing a robust program of interagency exercises and training that practice communication and resource sharing.

6.1.9 Medical Counter Measures (MCM)

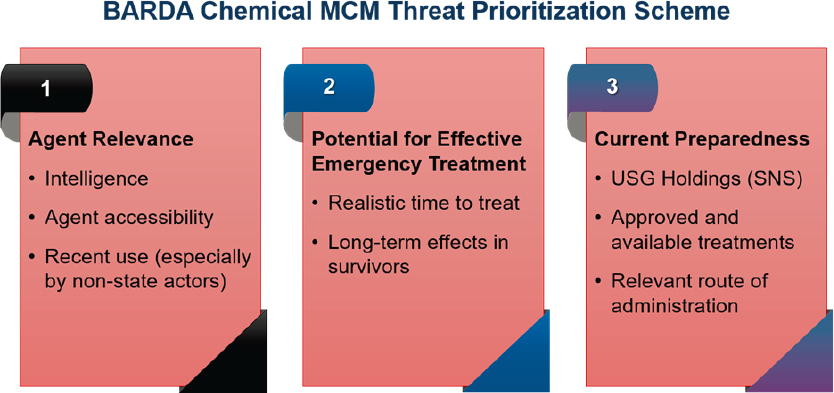

Initiatives for collaboration across federal agencies exist to address issues around medical countermeasures (MCMs). Figure 6-4 illustrates how Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) prioritizes chemical agents for which MCMs are needed and made available. First, the relevant agent is identified based on intelligence, level of accessibility, and information related to the agent’s previous use by nonstate actors. Second, a judgment will be made on how to respond to the chemical incident. Factors such as realistic time to treat and long-term effects on survivors are considered. Third, BARDA will assess its current level of preparedness given current USG holdings, approved and available medical treatments, and available routes of administration. The results of these assessments are used to identify and address gaps in current preparedness.

The assessment of the military/USAMRICD and the NIH MCM development is reviewed, and a critical assessment of their goals, priorities, implementation plans, and progress with findings and gaps is presented. In 2006, the Chemical Countermeasures Research Program (CCRP) under NIH-NIAID established the Medical Chemical Countermeasures Against Chemical Threats (CounterACT) Program. Although MCMs

TABLE 6-1 Federal Agencies and Programs Involved in Response

| Federal Agency | Program | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Department of Homeland Security (DHS) | Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) Office of Health Affairs (OHA) Science and Technology Directorate (S&T) Chemical Security Analysis Center (CSAC) |

FEMA coordinates and supports emergency response efforts, including those related to chemical terrorism incidents. CISA provides expertise and support for protecting critical infrastructure, including chemical facilities. OHA works to ensure preparedness and response capabilities for public health emergencies, including chemical incidents. S&T conducts research and develops technologies to enhance the response and recovery from chemical terrorism incidents. CSAC provides chemical threat information, design and execution of laboratory and field tests, and a science-based threat and risk analysis capability to create best response to chemical hazards. |

| Department of Justice (DOJ), and Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) | Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) Weapons of Mass Destruction Strategic Group Consequence Management Coordination Unit (WMDSG CMCU) Directorate of Intelligence Critical Investigative Division |

FBI investigates and responds to chemical terrorism threats and attacks, working in coordination with other agencies. ATF addresses the illegal use, acquisition, and trafficking of chemicals, including those used for terrorism. WMDSG CMCU develops response plans, shares intelligence, and coordinates efforts to address WMD, including chemical terrorism threats and incidents through external partnerships. Directorate of Intelligence gathers, analyzes, and disseminates intelligence related to chemical terrorism threats to members of the IC, LE, and private sector. Critical Investigative Division conducts investigations into domestic terrorism, including chemical terrorism incidents and related activities. |

| Department of Defense (DoD) | U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Chemical Defense (USAMRICD) | USAMRICD develops medical countermeasures to chemical threats; and trains and educates medical personnel for the management of chemical causalities. |

| Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) | Criminal Investigation Division Emergency Response Program (ERP) | Criminal Investigation Division investigates violations of environmental laws related to chemicals, including those with potential terrorism connections. ERP provides technical expertise and resources to respond to chemical incidents, including those involving terrorism. |

| Federal Agency | Program | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Department of Health and Human Services (HHS); National Institute of Health (NIH) | U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Chemical Defense (USAMRICD) Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) Biomedical Advanced R&D Authority (BARDA) National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID) |

USAMRICD conducts research on chemical defense and provides medical support in response to chemical incidents, including those involving terrorism. DTRA develops and deploys advanced detection and response capabilities to counter chemical threats, including terrorism. BARDA develops and procures MCM that address the public health and medical consequences of CBRNincidents. NIAID develops medical countermeasures against infectious agents that could be used in chemical attacks. |

| Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) | The National Counter Terrorism Center (NCTC) | NCTC produces threat analysis, maintains the authoritative database of known and suspected terrorists, shares intelligence, and conducts strategic operational planning. |

| Department of Agriculture (USDA) | Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) | APHIS works to prevent and respond to chemical threats, including agroterrorism incidents that may involve chemical agents. |

SOURCE: BARDA briefing to the committee.

have been developed by USAMRICD for a select number of chemicals, USG supports research to develop, improve, and optimize treatments for many as yet unaddressed chemical threats (Jett & Laney, 2001). CounterACT was created in addition to USAMRICD due to significant differences between military and civilian scenarios including the demographics of the at-risk population. The U.S. Congress appropriated funds to the NIH to implement the National Strategic Plan and Research Agenda focused on understanding chemical toxicities and to use that knowledge to identify novel targets and develop promising candidate therapeutics.

CounterACT involves partnerships with other federal agencies, academia, and industry (see Table 6-2); its mission is to integrate cutting edge scientific research with the latest technological advances and medicine that could facilitate a rapid response during a chemical emergency. NIAID’s current research priorities are based on DHS list of chemical agents (classified) and the Chemical and Biological Defense Program. NIAID is currently engaging with the broader academic research community to evaluate these priorities as a means to strengthen response based on identified toxidromes. The recommendations on the research priorities and the collaborations can be found in the 2003 NIAID Summary of the NIAID Expert Panel Review on Medical Chemical Defense Research (NIAID, 2003).

In the NIAID summary, the participants provided recommendations in the area of medical research for chemical defense that drove to the research objectives for this research program. CounterACT has provided outcomes that fulfill its objectives of stimulating and facilitating the development of a collaborative research community. These efforts include connecting research communities within academia, government (e.g., DoD and HHS), and industry partners.

In an information-gathering meeting with the committee, Dr. Yeung reported that with these collaborative research efforts, the NIH CCRP program has developed a pipeline of several MCMs (see Table 6-2).

TABLE 6-2 Drugs or Therapeutics Under the NIH CCRP Program and Collaborators

| Name of Drug or Therapeutic | Function | Collaborator |

|---|---|---|

| Galantamine | neuroprotectant for organophosphate (OP) intoxication | Countervail Corporation |

| Midazolam tPA | anti-seizure drug for OP intoxication treatment for airway cast obstruction induced by inhalation of sulfur mustard | Pfizer Genentech |

| R-107 | treat inhalation chlorine injuries | Radical Therapeutics, Inc |

| TRPV4 Channel Blocker | treatment for inhalation chlorine injuries | GSK |

| Tezampanel | anti-seizure for benzodiazepines-resistant OP intoxication | PRONIRAS |

| Ganaxolone | anti-seizure/neuroprotectant for OP intoxication | Marinus Pharmaceuticals |

| INV-102 | treats sulfur mustard-induced ocular injury | Invirsa and USAMRICD |

The CounterACT program has further transitioned promising MCM candidates to BARDA. The CounterACT-BARDA facilitates partnerships with the pharmaceutical industry, which is essential for providing an integrated, systematic approach to the development of the necessary vaccines, drugs, therapies, and diagnostic tools for public health medical emergencies including chemical accidents, incidents, and attacks. Thus far, BARDA has obtained FDA approval for Argentum’s Silverlon for sulfur mustard burns, Meridian’s Seizalam for status epilepticus, and Primary Response Incident Scene Management (PRISM) Guidance for Mass Decontamination (U.S. DHHS, n.d.).

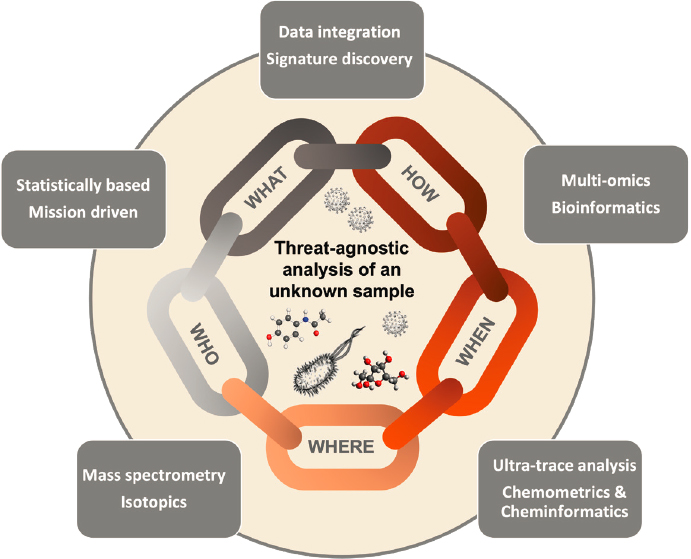

BARDA funds companies to drive innovation in using existing pharmaceutical products for new use in medical countermeasures (repurposing drugs) as well as developing broad-spectrum treatment measures (threat agnostic countermeasures). Figure 6-5 illustrates an integrated approach of coupling spectroscopy and computation to analyze unknown samples that could be chemical threats. For example, BARDA, in partnership with Johnson & Johnson, created an initiative called Blue Knight (Johnson and Johnson, 2022) which is dedicated to

anticipating potential health security threats, activating the global innovation community, and amplifying scientific and technological advancements with the aim to prepare for and respond to our rapidly evolving global health environment.

Public Health Emergency Medical Countermeasures Multiyear Budget (PHEMCE MYB) for MCM development and stockpiling for HHS agencies; NIH, Assistant Sec-

SOURCE: Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL).

retary for Preparedness Response (ASPR)-BARDA-, and ASPR-SNS, and FDA for the period between 2022–2026 (see Table 6-3). The PHEMCE MYB funding will be used to develop and support the transition of ten MCM candidates from BARDA’s Project BioShield (PBS) to stockpiling by the SNS by fiscal year (FY) 2026. The chemical portfolio is allotted $1.5 billion over five years and its portfolio includes six NIH institutes and BARDA. The portfolio also includes funding to support the sustainment of SNS’s current level of preparedness through replacement of expiring anticonvulsants, nerve agent antidotes, and other supportive medical materials (BARDA, 2023).

There are several challenges faced by researchers and drug companies in developing MCMs for use in a chemical emergency or terrorist attack since their characteristics, route, and time of administration have to be relevant for use in mass casualty scenarios (Jett and Laney, 2021).

Another challenge that BARDA faces is obtaining rapid availability of MCM supplies should there be a terrorist attack. Access to key components of the pharmaceutical industrial base and supply chain, which are currently manufactured outside the United States, is an issue. A majority of the Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) and their chemical compounds needed for critical medicines are also manufactured abroad. BARDA has created strategic partnerships with industry to expand pharmaceutical manufacturing in America with the aim to increase the domestic industrial base to allow for the additional raw material and consumables production necessary to support the manufacturing of therapeutics and vaccines during an emergency (BARDA, 2023).

The NIH, DTRA, and BARDA programs are using basic and translational research for MCM development and have broadened the base of collaborations among academic researchers and laboratories across the nation. Due to the ease of availability or access to toxic industrial chemicals/toxic industrial materials (TICs/TIMs), their use in terrorist activities has been enhanced. Therefore, the development of MCMs for next-generation chemical threats is needed (Casillas et al., 2021). Although NIH and BARDA have been successful in leveraging innovation and partnerships to accelerate the development of MCMs and obtain FDA licensure and clinical application for many, there is limited availability of FDA-approved MCMs for chemical threat exposures.

TABLE 6-3 Estimated Total PHEMCE Spending by HHS Division and Fiscal Year (dollar in millions)

| Division | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | FY 2025 | FY 2026 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIH | $2,835 | $2,825 | $3,065 | $3,131 | $3,199 | $15,055 |

| ASPR BARDA | $1,818 | $1,973 | $13,192 | $12,394 | $10,928 | $40,305 |

| ASPR SNS | $845 | $975 | $1,963 | $1,588 | $1,439 | $6,809 |

| FDA | $216 | $224 | $371 | $519 | $527 | $1,857 |

| TOTAL | $5,714 | $5,997 | $18,590 | $17,632 | $16,093 | $64,025 |

SOURCE: DHHS: Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response, 2023.

6.2 SUMMARY

The current set of U.S. strategies, operational plans, and other resources has helped establish a network of capable first responder communities prepared for various chemical incidents, regardless of their cause. Tools aimed at improving communication for CBRN response have been discontinued, which could impede robust coordination across federal and SLTT organizations. Including input from first responders and export control communities will ensure timely threat assessments and protocol adjustments. This inclusion is especially important for strategies that involve whole of government sharing: U.S. Global Deterrence Framework. The committee found that the NRF adequately addressed chemical terrorism categorically under ESF #10 and Oil and Hazardous Materials Response. Nonetheless, translating U.S. strategies and frameworks into operational practice for chemical terrorism response remains a challenge. Given the complexity of the chemical threat landscape and the need for effective response coordination within the USG, the committee suggested current counterterrorism and emergency preparedness programs maintain a strong initiative of interagency exercises and trainings that focus on enhancing communication and resource sharing.

REFERENCES

BARDA. 2023. Medical Countermeasures Capacity Partnerships. https://www.medicalcountermeasures.gov/barda/influenza-and-emerging-infectious-diseases/coronavirus/pharmaceutical-manufacturing-in-america.

Casillas, R., N. T-Singh, J. Gray. 2021. “Special Issue: Emerging Chemical Terrorism Threats.” Toxicology Mechanisms and Methods 31(4): 239–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/15376516.2021.1904472.

ChemResponder Steering Committee. 2020. “ChemResponder Network Who We Serve.” https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-07/fema_cbrn_chemresponder_fact-sheet.pdf.

CISA. 2018. SAFECOM Nationwide Survey, 2018. https://www.cisa.gov/safecom/safecom-nationwide-survey.

DHHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). n.d. https://aspr.hhs.gov/AboutASPR/ProgramOffices/BARDA/Pages/default.aspx.

DHHS, Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response. 2023. Public Health Emergency Medical Countermeasures Enterprise: Multiyear Budget: Fiscal Years 2022—2026.

DHS (U.S. Department of Homeland Security). 2021. Chemical Security Analysis Center, Jack Rabbit II. https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/2021_0205_csac-jack_rabbit_ii_factsheet_2-5-2021_pr_508.pdf.

DHS. 2006. Communicating in a Crisis: Chemical Attack. https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/prep_chemical_fact_sheet.pdf.

DOT (U.S. Department of Transportation). 2023. Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, Office of Hazardous Material Safety, 10 Year Incident Summary Reports. https://www.phmsa.dot.gov/hazmat-program-management-data-and-statistics/data-operations/incident-statistics.

ECPC (Emergency Communications Preparedness Center). 2021. Annual Strategic Assessment. https://www.cisa.gov/sites/default/files/cisa/21_0702_2019%20Emergency%20Communications%20Preparedness%20Center%20(ECPC)%20Annual%20Strategic%20Assessment%20Report_508c.pdf.

EPA (Environmental Protection Agency). 2008. ESF #10—Oil and Hazardous Materials Response Annex. https://www.fema.gov/pdf/emergency/nrf/nrf-esf-10.pdf.

FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency). n.d. ChemResponder Network. https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-07/fema_cbrn_chemresponder_fact-sheet.pdf.

FEMA. n.d. Office of Emerging Threats. https://www.fema.gov/about/offices/response-recovery/emerging-threats.

FEMA. 2010. Developing and Maintaining Emergency Operations Plans, Comprehensive Preparedness Guide (CPG) 101 Version 2.0. November 2010.

FEMA. 2021. Oil and Chemical Incident Annex. (http://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_incident-annex-oil-chemical.pdf.

Fox, S., and S. McMasters. 2022. Jack Rabbit III Initiatives: Chemical Threat Characterization through Experimentation for Strengthening Safety and Security of Critical Infrastructure. https://www.cisa.gov/sites/default/files/publications/2020-seminars-jack-rabbit-III-508.pdf.

Jett, D., and J. Laney. 2021. “Civilian Research on Chemical Medical Countermeasures.,” Toxicology Mechanisms, and Methods 31(4): 242–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/15376516.2019.1669250.

Joint Counterterrorism Assessment Team. n.d. “First Responder Toolbox.” Www.dni.gov. https://www.dni.gov/index.php/nctc-how-we-work/joint-ct-assessment-team/first-responder-toolbox.

Johnson and Johnson. 2022. Blue Knight. https://jnjinnovation.com/jlabs/blue-knight.

NIAID (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases). 2003. Summary of the NIAID Expert Panel Review on Medical Chemical Defense Research. https://www.niaid.nih.gov/sites/default/files/chem_report.pdf.

NIH/NLM (National Institutes of Health/National Library of Medicine. 2023. Wireless Information System for Emergency Responders (WISER). https://www.nlm.nih.gov/wiser/index.html.

Savage, T. 2022. FBI, National Security Branch, briefing to the Chem Threats Committee. August 11, 2022.

START (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism). 2022. Global Terrorism Database 1970-2020 [data file]. https://www.start.umd.edu/gtd.

U.S. Government Accountability Office. 2023. Chemical Weapons: Status of Forensic Technologies and Challenges to Source Attribution (GAO-23-105439). https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-23-105439.

White House. 2018. National Strategy for Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Terrorism. https://www.hsdl.org/?view&did=819382.

This page intentionally left blank.