The Current Status and Future Direction of High-Magnetic-Field Science and Technology in the United States (2024)

Chapter: 10 Multimodal Capabilities: Combining High Magnetic Fields with Neutron, Synchrotron Radiation, and Free Electron Laser Facilities

10

Multimodal Capabilities: Combining High Magnetic Fields with Neutron, Synchrotron Radiation, and Free Electron Laser Facilities

INTRODUCTION

The development of new technologies drives scientific discoveries, the development of new materials and their applications and is thereby essential to the U.S. leadership in the global competitive economy. This chapter provides a forward look at the exciting capabilities and novel science that is enabled by combination of neutron and X-ray scattering methods with high-magnetic-field capabilities. The United States has been leading the development of novel technology worldwide in the field of X-ray technology, where the world’s first X-ray free electron laser (XFEL) was built and started operating in 2009 at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC). The Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) II broke new grounds this year with first user operation at megahertz repetition rates. Equally exciting technology developments have taken place in neutron studies with the Spallation Neutron Source (SNS), at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), which began operation in 2006 and since then has been providing continuously increasing power for a broad user community. In 2023, SNS set a world record when its operating power reached 1.7 MW, significantly improving the originally designed capability. Currently, ORNL has moved forward achieving 2 MW of power and the construction of

a Third Target Station (in addition to the First Target Station [FTS] at the SNS and the Second Target Station [STS] at the High Flux Isotope Reactor [HFIR] neutron source) to address scientific challenges.1 The United States also supports third- and fourth-generation synchrotron light sources at Argonne, Berkeley, Brookhaven, and Cornell that support a community of tens of thousands of researchers.2 However, as we will see in this chapter, the United States will need to establish its leading role in the combination of high-magnetic-field studies with instruments like X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs), synchrotrons, and neutron sources.

This chapter will explore the huge scientific advances that can be made by combining the neutron, synchrotron, and XFEL facilities with high-magnetic-field research in the United States and compare it with the development of a combination of these techniques worldwide.

INTRODUCTION TO NEUTRON FACILITIES

Neutron scattering is an essential technique for advancing scientific achievements and materials research that provides considerable contribution the U.S. economy and offers solutions to challenges in energy, security, and transportation. It provides information that cannot be obtained using any other research method. Neutron scattering is an essential probe in the studying of solids and biological materials and soft materials such as polymers. Neutron scattering experiments with a high magnetic field enable new discoveries not possible with other techniques. Magnetic fields provide a critical tuning parameter that naturally couples with neutron scattering to determine structure and dynamics in field-induced phases, suppressing superconductivity and magnetic order, suppressing quantum fluctuations and quantifying interactions near saturation, depth profiling of magnetism at buried interfaces using polarized neutrons, and amplifying hydrogen scattering in biological materials using dynamic nuclear polarization.

High Magnetic Fields with Neutron Science

Here the committee provides a few examples of important experiments performed in combination of neutron scattering and high magnetic fields, which indicate new opportunities in science.

___________________

1 Oak Ridge National Laboratory, 2020, “Second Target Station: Additional Neutron Source Will Meet Emerging Science Challenges,” https://neutrons.ornl.gov/sts.

2 A complete list of neutron and synchrotron facilities can be found through the International Union of Crystallography at https://www.iucr.org/resources/other-directories/facilities.

Example 1

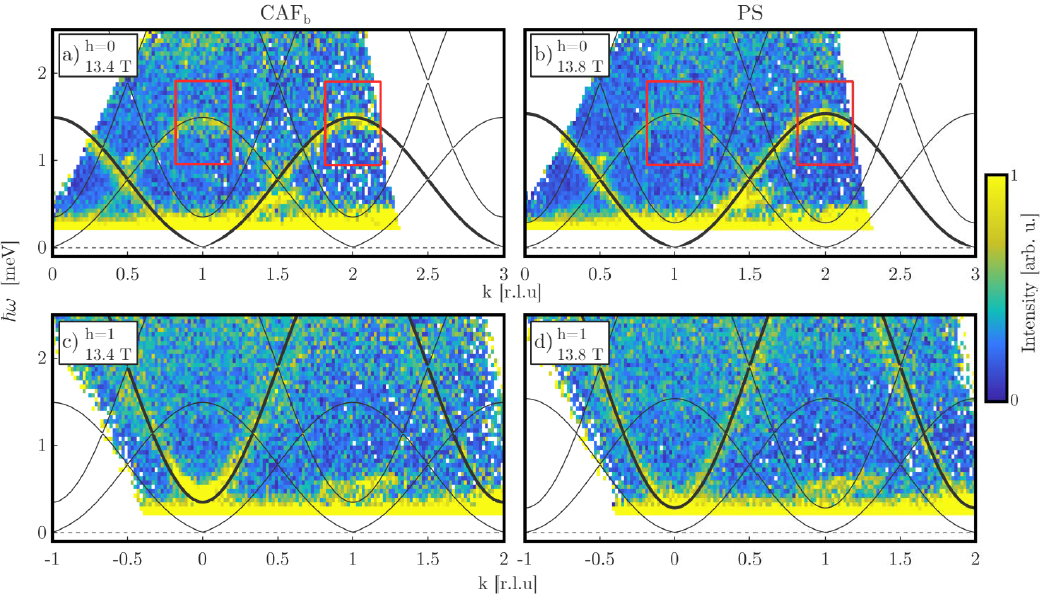

Experiments on single-crystal elastic and inelastic neutron scattering are carried out in strong magnetic fields on various topical systems, such as frustrated magnets, Kagome metals, high-temperature superconductors, and many others. Combining neutron diffraction and inelastic-neutron-scattering studies in high magnetic fields, a peculiar type of spin reorientation in the ferro-antiferromagnet SrZnVO(PO4)2 near saturation has been measured and allowed to address a lingering mystery observed in the layered vanadyl phosphates ABVO(PO4)2 (A, B = Sr, Zn, Pb, Ba, and Cd), which were showing unusual presaturation behavior, as seen in Figure 10-1, but the nature and origin of this presaturation phase remained unresolved. The results indicate that the transition at Hc involves a peculiar type of spin reorientation that is of purely classical origin and is caused by Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interactions.

Example 2

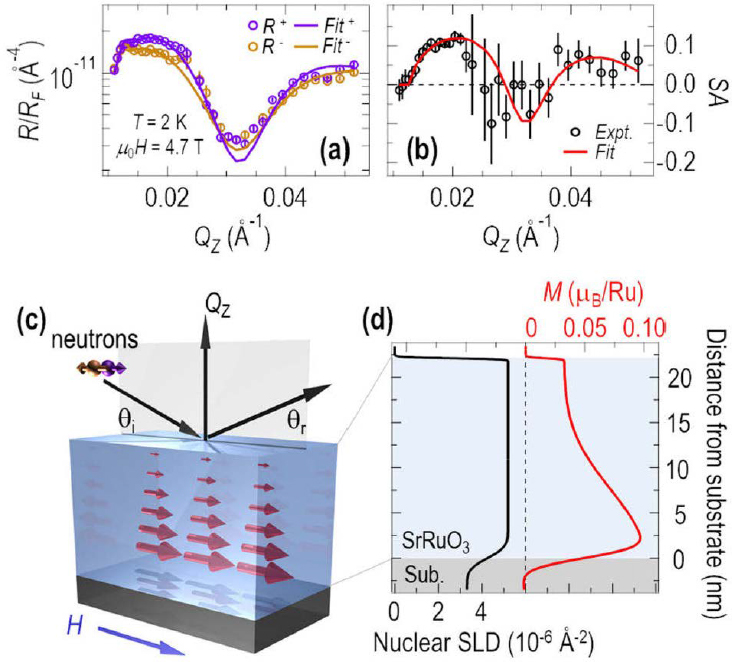

Controlling electronic band structure is an important step toward harnessing quantum materials for practical uses. This is exemplified in the spin-polarized bands near the Fermi level of a ferromagnet where small variation to the Berry curvature can be used to control the intrinsic anomalous Hall effect (AHE).3 In this work, depth-dependent magnetic inhomogeneity in a 4d itinerant ferromagnet SrRuO3 film is controlled by applying low energy He ion irradiation. As shown in Figure 10-2, Polarized Neutron Reflectometry measurements at 4.7 T show a reduced magnetization near the surface of at the He ion irradiated SrRuO3 demonstrating that small variations of the crystal lattice modify the Berry curvature altering the spin-polarized bands near the fermi level.

Example 3

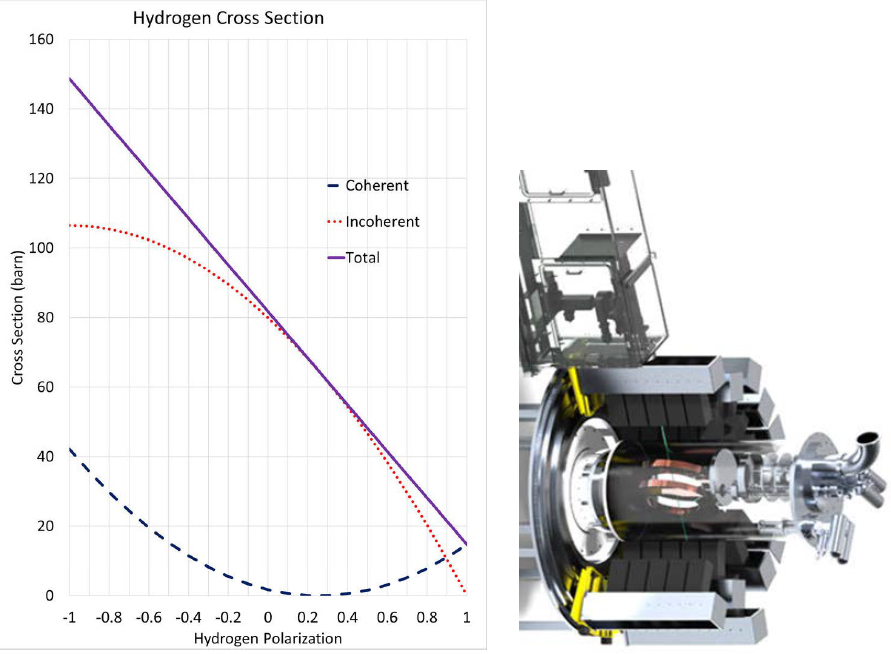

Dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) is a uniquely powerful technique for neutron diffraction measurements of biological materials, providing tunable control of hydrogen neutron scattering cross sections in situ within biological crystals during an experiment and enabling 10–100-fold enhancements in neutron diffraction data and order of magnitude enhancements in the visibility of hydrogen atoms in the resulting protein structures. Neutron macromolecular crystallography is uniquely sensitive to the location of hydrogen (H) atoms in biological structures, but diffraction is limited by the large hydrogen incoherent scattering background (noise)

___________________

3 E. Skoropata, A.R. Mazza, A. Herklotz, et al., 2021, “Post-Synthesis Control of Berry Phase Driven Magnetotransport in SrRuO3 Films,” Physical Review B 103(8):085121, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.103.085121.

SOURCE: Reprinted figure with permission from F. Landolt, K. Povarov, Z. Yan, et al., 2022, “Spin Correlations in the Frustrated Ferro-Antiferromagnet SrZnVO(P)4)2 Near Saturation,” Physical Review B 106(5):054410, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.106.054410. Copyright 2022 by the American Physical Society.

SOURCE: E. Skoropata, A.R. Mazza, A. Herklotz, et al., 2021, “Post-Synthesis Control of Berry Phase Driven Magnetotransport in SrRuO3 Films,” Physical Review B 103(8):085121, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.103.085121. CC BY 4.0.

that can rapidly overwhelm the coherent elastic signal. For nuclei with nonzero spin, such as hydrogen, the magnitude of the coherent (signal) and incoherent (background) parts of the scattering cross section is dependent on the relative spin orientations of the neutron and the nucleus.4 Polarizing the neutron beam and aligning the proton spins in a polarized sample modulates and tunes the coherent and incoherent neutron scattering cross-sections of hydrogen, in ideal cases maximizing the scattering from and visibility of hydrogen atoms in the sample while simultaneously minimizing the incoherent background to zero (see Figure 10-3).

The DNP technique5 offers an effective way to achieve a high degree (up to ~99 percent) of nuclear polarization in nonmetallic samples. A dedicated project on the application of DNP techniques is being constructed at the High Flux Isotope Reactor (HFIR) at ORNL (funded by the Department of Energy, National Biopreparedness and Response program). It is equipped with versatile capabilities of high magnetic fields (2.5–5.0 T with field homogeneity of 10–4 T/cm), low temperature (<1 K), and 70–140 GHz microwave irradiation to transfer electron spin polarization from paramagnetic centers to the surrounding protons. Harnessing DNP for neutron protein crystallography requires addition of electron spin ½ labels to the sample (e.g., stable organic radicals), spin polarization of the unpaired electrons, and then transfer of polarization from the paramagnetic center into the 1H nuclei of the protein. This is achieved by soaking paramagnetic centers directly into single crystal protein samples, flash-cooling the samples in liquid nitrogen and transferring to a pre-cooled (at 1 K) low-temperature cryostat that is inserted into a 5 T magnet. “Polarizations” are then pumped from easily polarized electron spins to nuclear ones using microwaves. At temperatures of <100 mK, the nuclear spins are then “frozen” in place for extended periods of time (hours or days), enabling spin polarized neutron diffraction data to be collected.6

Despite significant achievements in increasing neutron source power since the 2013 NRC report, the maximum magnetic fields available for neutron scattering experiments in United States are still fixed at 15–16 T. The typical example of the current status of the available magnets for neutron experiments is represented in Table 10-1. Similar sample environment equipment superconducting magnets (7 T–15 T) are available at NCNR/NIST.7

___________________

4 A. Abragam and M. Goldman, 1978, “Principles of Dynamic Nuclear Polarisation,” Reports on Progress in Physics 41(3):395, https://doi.org/10.1088/0034-4885/41/3/002.

5 A. Abragam, 1961, The Principles of Nuclear Magnetism, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

6 J. Pierce, M.J. Cuneo, A. Jennings, et al., 2020, “Chapter Eight - Dynamic Nuclear Polarization Enhanced Neutron Crystallography: Amplifying Hydrogen in Biological Crystals,” pp. 153–175 in Methods in Enzymology, P.C.E. Moody, ed., Cambridge, MA: Academic Press.

7 See National Institute of Standards and Technology Center for Neutron Research, “15T VF,” https://www.nist.gov/ncnr/sample-environment/equipment/superconducting-magnet-systems/15t-vf, accessed July 1, 2024.

SOURCE: Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

TABLE 10-1 Current Suite of Superconducting Magnets at SNS/HFIR

| Vertical Field Split Pair Magnets | |

|---|---|

| SNS magnets with cryogenic bore | HFIR magnets with cryogenic bore |

|

|

SNS magnets with warm bore

|

|

| Horizontal Field Magnets | |

SNS magnets with warm bore

|

HFIR magnets with cryogenic bore

HFIR magnets with cryogenic bore

|

| Need for more horizontal field magnets which can be beneficial for both spectroscopy and diffraction | |

SOURCE: Data from Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

At the same time, new facilities that combine at FELBE two mid and infrared (5–250 μm) Free Electron Lasers with a pulsed magnetic field of 85 T at the Forschungszentrum Dresden-Rossendorf and the Dresden High Magnetic Field Laboratory became operational more than a decade ago and were mentioned in the NRC 2013 report. At the neutron scattering facility Institute Laue Langevin in Grenoble, France, a 40 T pulsed magnetic field is available for experiments.

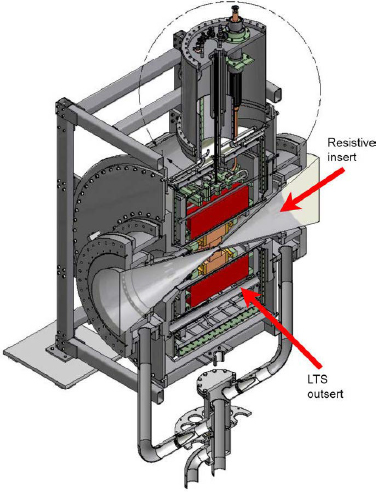

A Helmholtz Zentrum Berlin (HZB) magnet achieved 26 T for neutron scattering in 2014. The HZB reactor was closed in 2019 and there is an effort to transfer this magnet to SNS. It needs a dedicated instrument to enable diffraction, SANS, and spectroscopy. Conical geometry of the magnet is restrictive but allows highest fields to be reached.

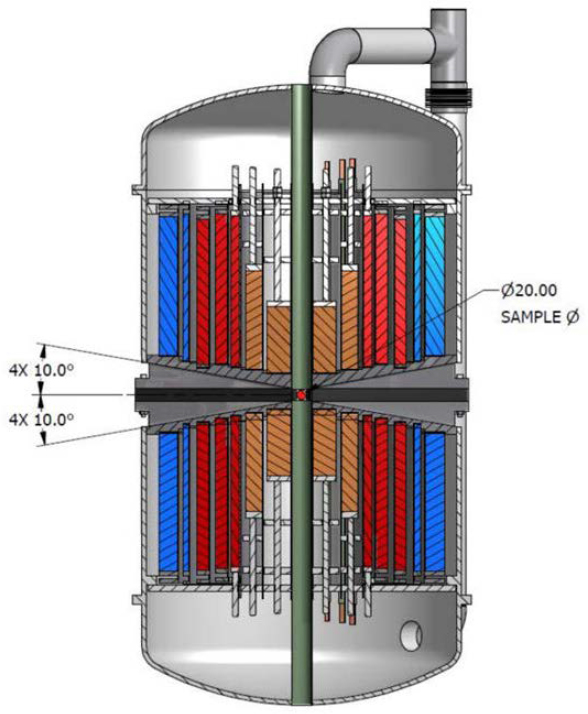

The magnet at SNS will not use the resistive insert; the concept is to replace the insert with a high-Tc insert, as shown in Figure 10-4. This effort required considerable research and development to develop these plans and to exceed 30 T. Such a magnet will require a dedicated instrument at SNS (likely at the Second Target Station, SNS) in the future and requires funding.

SOURCE: P. Smeibidl, A. Tennant, H. Ehmler, and M. Bird, 2010, “Neutron Scattering at Highest Magnetic Fields at the Helmholtz Centre Berlin,” Journal of Low Temperature Physics 159:402, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10909-009-0062-1, Springer Nature.

Comparison with International Neutron Facilities

The European leading neutron facilities, Institut Laue-Langevin (ILL), Grenoble, France, and Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in Oxfordshire, United Kingdom, have a well-developed park of various magnets, considerably exceeding the equipment of SNS and HFIR (see Tables 10-2, 10-3, and 10-4).

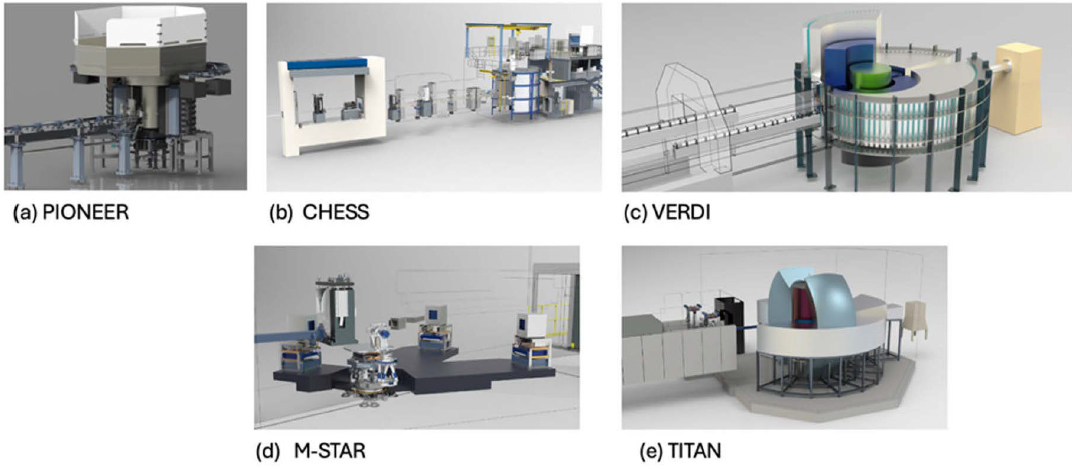

The concepts for future SNS instruments for the Second Target Station place additional demand on magnets. These are new generation instruments with advanced and unprecedented capabilities that empower new cutting-edge physics. Some of the new-generation neutron scattering instruments at the Second Target Station (STS) at Oak Ridge National Laboratory are shown in Figure 10-5.

Finding: Neutron scattering facilities need to increase magnet capacity and operational efficiency to meet the requirements of the scientific user community.

TABLE 10-2 Institut Laue-Langevin Grenoble France Vertical Field Magnets

| Magnetic Field (T)(T) | Gap (mm) | Sample dim. Ø × Height (mm) | Temperature Range | Dimensions (mm) | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 40 | Ø49 | 1.5–300 | — | 2006 |

| 6 asymmetric |

40 |

Ø49 × 130* Ø35 with dilution |

40 mK–300 K | Ø388 in scat. plane | 1994 |

| 7 asymmetric |

30 | Ø20 × 20 | 1.5–300 | 390 in scat. plane | 2011 |

| 10 asymmetric |

10 | Ø10 × 10 or Ø38 × 20 Ø32 with dilution |

40 mK–650 K | Ø512 in scat. plane | 1999 |

| 10 asymmetric |

40 | Ø39 × 318* | 40 mK–300 K | Ø598 in scat. plane | 2010 |

| 10 | 40 | Ø39 × 30 | 40 mK–300 K | ≈Ø540 in scat. plane | 2017 |

| 12 asymmetric |

22 | Ø30 × 20 | 40 mK–300 K | Ø560 in scat. plane | 1994 |

| 15 | 20 |

Ø25 × 285* 140 from M8 Ø18 × 64 with dilution |

35 mK–300 K | Ø598 in scat. plane | 2004 |

NOTES: * total available height in the calorimeter. The height of the neutron beam is necessarily less than the gap of the split-pair coil.

SOURCE: Data from Institut Laue-Langevin, “Vertical Field Magnets,” https://www.ill.eu/fr/users/support-labs-infrastructure/sample-environment/equipment/high-magnetic-field/vertical-field-magnets, accessed July 24, 2024.

Conclusion: Neutron scattering facilities require an increase in magnet inventory, and instruments need magnets with various maximum field strengths. These would be a mix of vertical field split pair, horizontal field solenoids, vector magnets, and horizontal field 4-pole magnets.

Finding: Consumption of liquid helium is a significant cost at SNS/HFIR and supply is a concern. Compact, cryogen-free, high-Tc neutron scattering magnets would be beneficial.

Conclusion: Neutron scattering magnet designs need to be compatible with complementary sample conditions: low temperature: liquid He: 1.5–300 K, 3He: 0.3–2 K, dilution refrigerator: 0.05–1 K; high temperature up to 1000 K; high pressure: <~3 GPa; sample positioning; rotating single crystals to map reciprocal space; compact goniometer for adjusting orientation; compact sample changers; and applied current or electric fields.

TABLE 10-3 Institut Laue-Langevin Grenoble France Horizontal Field Magnets

| Magnetic Field (T)(T) | Gap (mm) | Sample dim. Ø × Height (mm) | Temperature Range | Dimensions (mm) | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5 | — | Ø24 Ø18 with dilution |

40 mK–300 K | — | — |

| 3 | — | Ø80 × 50 Ø42 × 50 with cryostat Ø36 with dilution |

40 mK–300 K | 425 × 366 in scat. plane | 2021 |

| 3.8 | 40 | Ø38 × 140 Ø30 with dilution |

40 mK–300 K | Ø600 in scat. plane | 1999 |

| 6 | — | Ø49 Ø36 with dilution |

40 mK–300 K | Ø657 in scat. plane | 2007 (HM-3) |

| 7 | — | Ø15 | 1.5–300 K | — | refurbished in 2005 |

| 8 | — | Ø21 × 20 Ø16 with dilution |

70 mK–300 K | — | refurbished in 2016 |

| 17 | — | Ø10 | 60 mK–300 K | 523 (// beam) × 480 in scat. plane | 2010 |

| 40 pulsed | — | Ø8 | 2–300 K | — | 2014 |

SOURCE: Data from Institut Laue-Langevin, “Horizontal Field Magnets,” https://www.ill.eu/fr/users/support-labs-infrastructure/sample-environment/equipment/high-magnetic-field/horizontal-field-magnets, accessed July 24, 2024.

TABLE 10-4 ISIS Neutron and Muon Source at Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in Oxfordshire Superconducting Magnets

| 2 T (3d magnet) | 3D Reflectometery Magnet | 70 mm | ||

| 4 T E18 Magnet | 4 T split pair vertical magnet | 30 mK–300 K | 200 mm dia. × 250 mm long | |

| 7.5 T | Split-pair 7.5 T Cryomagnet | 2–300 K | 48 mm dia. × 40 mm high | 45 |

| 9 T | 9 T Chopper Magnet | 4.2–300 K | 50 mm | |

| 10 T | Split-pair 10 T Cryomagnet | 2–300 K | 5 0mm dia. × 15 mm high | |

| 14 T | 13.6 T recondensing superconducting vertical magnet | 340 degrees in-plane opening and –5/+10 degrees opening. |

SOURCE: Data from UK Research and Innovation, “High Magnetic Field,” https://www.isis.stfc.ac.uk/Pages/High-Magnetic-Field.aspx, accessed July 24, 2024.

NOTES: For details on the instruments, see Coates, L. 2023. “Special Topic on “Initial instruments at the Second Target Station of the Spallation Neutron Source,” Review of Scientific Instruments 94(4), https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0141985.

SOURCE: Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

Current Status and Needs for Pulsed Magnets for Customized Studies of Magnetic Materials

Previous pulsed field measurements up to 30 T enable studies not possible with steady-state magnets. Ongoing developments at J-PARC (Japan) and ILL (France) can now exceed 40 T. Existing pulsed magnets do not efficiently use the neutron beam at Spallation Neutron Source as it takes minutes to cool the magnet between pulses (SNS is a 60 Hz source).

Introduction to Large Facilities in X-Ray Science, Including XFELs

The most advanced current X-ray technologies include fourth-generation synchrotron radiation sources and XFELs. The fourth-generation synchrotron sources offer enormous increases in brightness and coherence and will enable entire new classes of spectroscopic and imaging experiments, many of which will be enhanced by the provision of high magnetic fields. The Advanced Photon Source (APS) has established a pulsed field facility offering a 500 kJ capacitor-bank driven magnet with a maximum field of 21 T and a pulse length of 7 msec. As noted elsewhere, CHESS is planning a 20 T continuous field on a high-energy beamline.

XFELs are unique as they provide exceptionally high X-ray photon flux of up to 1016 photons/second within ultrashort X-ray pulses. These femtosecond (1 femtosecond = 10−15 seconds) pulses are shorter than the time duration associated with the damage of molecules and materials. Outrunning the X-ray damage enables damage-free investigations of the dynamics of electrons, molecules, crystals, and materials under conditions that range from investigation of biomolecules at native conditions at room temperature and ambient pressure all the way to extreme pressure and temperatures that can mimic the inside of Earth. The first hard XFEL in the world was LCLS in Stanford with currently five hard XFELs operating in the world. The XFEL technology has made a huge impact in all areas of research ranging from biology, chemistry, and physics to material and quantum science.

Impact of the Combination of High-Magnetic-Field Science with X-Ray Techniques

The combination of high magnetic field and XFEL science enables new kinds of magnetism experiments.

XFELs IN THE UNITED STATES

The United States has one XFEL facility, LCLS, that operates two XFELs. One of them started operation in 2009 and provides hard X rays (5 to 20 keV) at 1–50 fs pulse duration and 120 Hz repetition rate. Another one, LCLS II, provides X

rays in soft to tender X rays (100 eV to 4 keV) with anticipated megahertz repetition rate. The United States has been leading in the field in the past, when the first high-impact experiments at the LCLS XCS endstation utilized uniquely high peak brightness X rays in combination with a high-magnetic-field instrument. The development of the instrumentation at the LCLS XCS endstation was a co-development of LCLS and SSRL—Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory. The development was user-driven, and by a huge effort of the users and the scientists the first breakthrough experiments were conducted in the United States at LCLS leading to four high-impact publications.

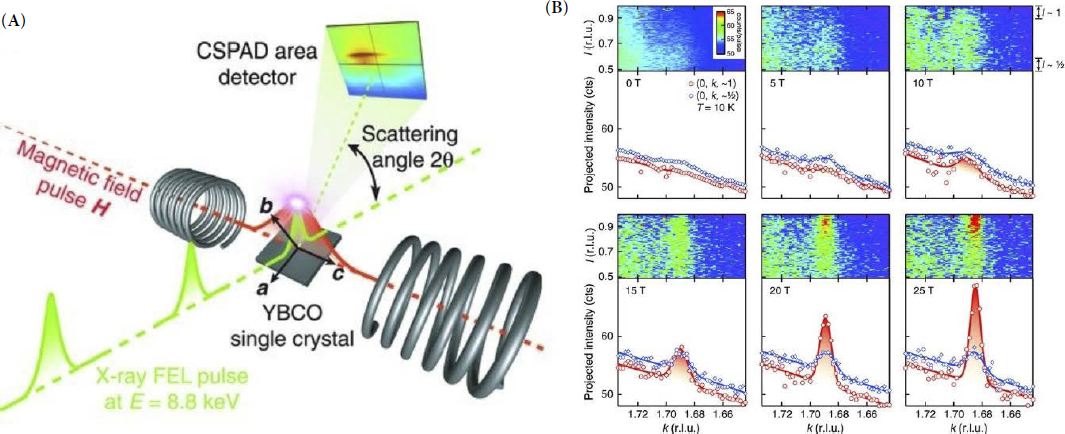

Science Case

The first paper was published in the high-impact journal Science.8 It was focused on the investigation of three-dimensional charge density wave order in YBa2Cu3O6.67 at high magnetic fields. In this breakthrough study, they investigated the charge density wave (CDW) correlations in cuprate superconductors by combining a pulsed magnet with an XFEL to characterize the CDW in a cuprate superconductor via X-ray scattering in fields of up to 28 T. The experimental setup at the XCS endstation at LCLS is shown in Figure 10-6. Figure 10-6 also shows the field dependence of the charge density wave order at T = 10 K. The results of this study were so exciting as they showed that two distinct forms of CDWs exist and that they are directly linked to high-temperature superconductivity.

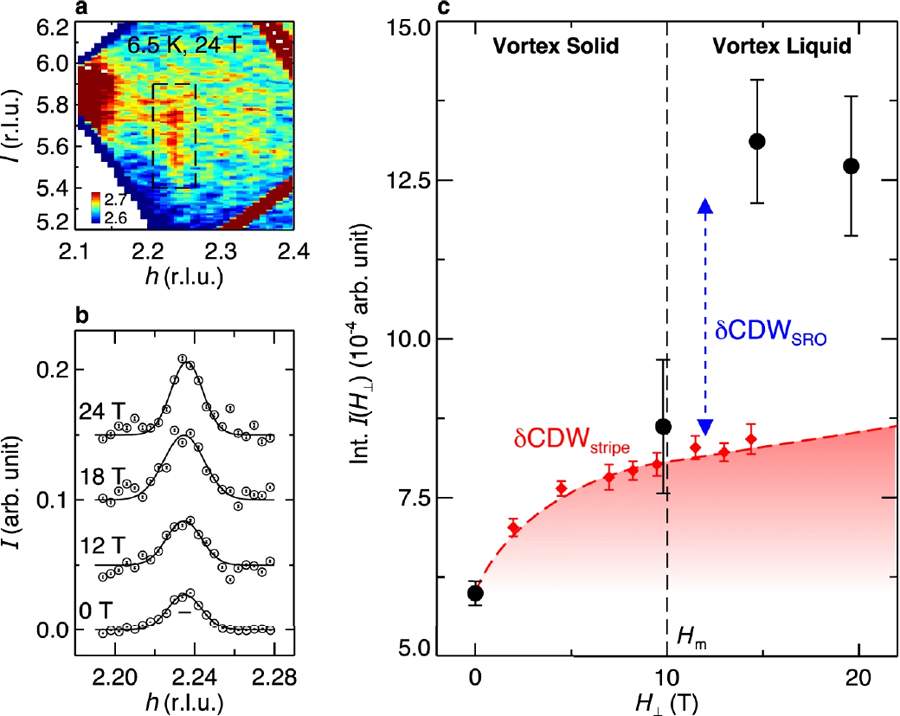

Three further exciting publications followed this first publication. The second high-impact publication was published a year later in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), where they discovered ideal charge-density-wave order in the high-field state of superconducting,9 and where they discovered the largest CDW correlation volume ever observed in any cuprate crystal, which is the representative of the high-field ground state of an “ideal” disorder-free cuprate. In 2018, results from a third study were published where they reached magnetic fields up to 33 T to investigate the onset of CDW order in YBa2Cu3Ox at low temperatures near a putative quantum critical point.10 A fourth publication in a high-impact journal Nature Communication was published in 2023 on enhanced charge density wave with mobile superconducting vortices. This paper is so exciting because they discovered at high fields a sudden increase in the CDW amplitude upon entering the vortex liquid state (Figure 10-7). These results show the strong

___________________

8 S. Gerber, H. Jang, H. Nojiri, et al., 2015, “Three-Dimensional Charge Density Wave Order in YBa2Cu3O6.67 at High Magnetic Fields,” Science 350(6263):949–952.

9 H. Jang, W.-S. Lee, H. Nojiri, et al., 2016, “Ideal Charge-Density-Wave Order in the High-Field State of Superconducting YBCO,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113(51):14645–14650.

10 H. Jang, W.-S. Lee, S. Song, et al., 2018, “Coincident Onset of Charge-Density-Wave Order at a Quantum Critical Point in Underdoped YBa2Cu3Ox,” Physical Review B 97(22):224513.

SOURCE: From S. Gerber, H. Jang, H. Nojiri, et al., 2015, “Three-Dimensional Charge Density Wave Order in YBa2Cu3O6.67 at High Magnetic Fields,” Science 350(6263). Reprinted with permission from AAAS.

SOURCE: J.J. Wen, W. He, H. Jang, H. Nojiri, S. Matsuzawa, S. Song, M. Chollet, et al., 2023, “Enhanced Charge Density Wave with Mobile Superconducting Vortices in La1.885Sr0.115CuO4,” Nature Communications 14(1):733, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-36203-x. CC BY 4.0.

coupling of the CDW to mobile superconducting vortices and link enhanced CDW amplitude with local superconducting pairing across the H—T phase diagram.

Prospectus of Future High-Magnetic-Field Studies at XFELs in the United States

The committee was very excited about the work of combined high-magnetic-field studies at the hard XFEL LCLS at SLAC. However, all the experiments were done before 2019 when LCLS started building LCLS II, the soft/tender X-ray superconducting XFEL that will reach 1 MHz repetition rate. When the committee

reached out to LCLS, it learned that they own the IP for the experimental setup at the XCS beamline; however, they currently do not plan to revive this capability and make it available to general users, nor are there any plans for implementing any high-magnetic-field research plans with LCLS II. The committee was told that the reason is that the initial breakthrough experiments are user-driven and were co-developed by the research group of Dr. Lee from SSRL with the staff scientists at LCLS. The experiments are conducted at low repetition rates where they are executed in a single shot mode where a single high-flux fs X-ray pulse “hits the sample” at the peak of the short pulsed magnetic field. As these experiments are not feasible at the megahertz repetition rate of LCLS II, LCLS is currently not planning to conduct further experiments that combine high magnetic fields with the XFEL X-ray scattering. LCLS I and II will operate in parallel so the question was raised if the experimental setup at the XCS endstation at LCLS I (that operates at 120 Hz) could be again established and made available to the broader scientific community. This would be feasible but would require strong support and demand from the scientific community.

STATUS OF HIGH-MAGNETIC-FIELD RESEARCH AT XFELS WORLDWIDE

Outside the United States, there are four hard XFELs operating worldwide: the European X-ray Free Electron Laser (EuXFEL) in Germany, the Pohang Accelerator Laboratory X-ray Free Electron Laser (PAL-XFEL) in South Korea, the Spring-8 Angstrom Compact Free Electron Laser (SACLA) in Japan, and the Swiss X-ray Free Electron Laser (SwissFEL) in Switzerland.

EuXFEL

Megahertz time resolution (in 10 pulse trains per second) and near “matching” coil-pulser LRC times are for the moment being a unique feature of EuXFEL in Germany. At the EuXFEL, researchers are planning to target and influence material properties. Research combining high magnetic fields with femtosecond X-ray pulses will be applied in many fields from studying and influencing the magnetic properties of quantum materials to development of novel electronics. The EuXFEL has developed at two end stations: the HED end station and the MID end station. The development of these end stations has been initiated in 2014 by the funding by the Helmholtz Foundation and now includes a large consortium of scientists from all over Europe. The experimental setup is currently in the commissioning phase and will start user operation soon, where scientists can then apply for experimental time at both end stations.

The HED end station was established in the framework of the HIBEF consortium the HZDR - High Field Magnetic Laboratory Dresden (HLD). It aims to provide pulsed high-field magnets at the HED instrument of EuXFEL in two geometries:

- Bi-conical horizontal solenoid magnets reaching up to 60 T (B||k)

- Vertical bore split pair with wide access in the equatorial plane reaching up to 40 T

The defining feature of these coils is an integrated eddy current shield to minimize the stray field and consequent interaction with the diffractometer and interference with detectors and electronics. The magnets are driven with a maximum current of up to 100 kA by a thyristor switched capacitive discharge power supply storing up to 750 kJ at a maximum charge voltage of 24 kV. The resulting field pulses have a duration of several milliseconds. The field direction can be reversed. The magnets are integrated on a conventional five-circle diffractometer.

For X-ray detection, users will be able to use the Sparta detector (commercially available AGIPD single module) for intra-train megahertz X-ray pulse resolved experiments with a pixel resolution down to 0.008 deg and Jungfrau detector for single pulse acquisition with a pixel resolution down to 0.003 deg. In addition, the detector arm is equipped with a three-circle polarization analyzer for the detection of pi-sigma and sigma-pi scattering.

The sample cryostat for the solenoid covers from 4.2 K to ambient temperatures. A vertical bore split coil would in principle allow the use of ultralow-temperature inserts. First experiments will take place in 2024 and aim to detect magneto-structural transitions and charge order. For the future we expect to study magnetic order and possibly the development of other resonant, nonresonant, and coherent techniques.

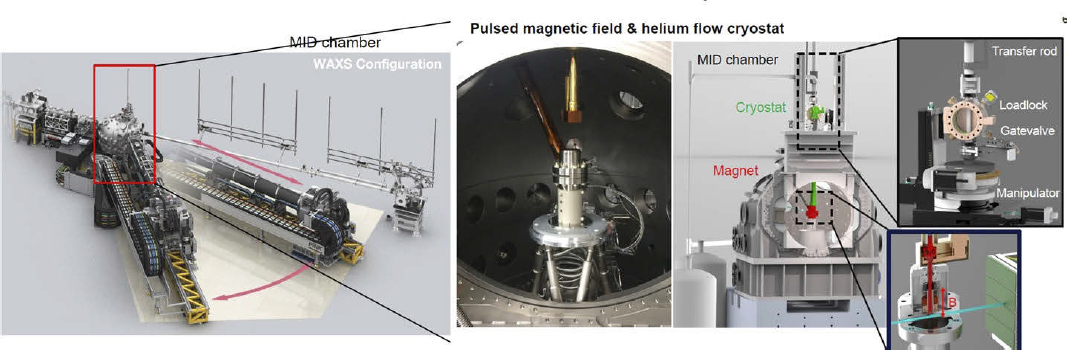

The MID end station at the EuXFEL has developed a Compact Pulsed Magnet (PuMa), as seen in Figure 10-8. The PuMa Project provides a maximum of 15 T with a rise time adapted to the pulse train width (~1 ms).

PAL-XFEL

The PAL-XFEL in South Korea started user operation in June 2017. According to their website,11 it consists of a hard X-ray (HX) and a soft X-ray (SX) FEL line. The HX line includes a 780 m long accelerator line, a 250 m long undulator line, and 80 m long experimental hall. The SX line is branched at the 260 m point from

___________________

11 Pohang Accelerator Laboratory, “PAL-XFEL: Facility,” https://pal.postech.ac.kr/paleng/Menu.pal?method=menuView&pageMode=paleng&top=7&sub=6&sub2=1&sub3=0, accessed June 13, 2024.

SOURCE: European XFEL, 2022, “Pulsed Magnetic Field (PUMA) Project,” January 24, https://www.xfel.eu/sites/sites_custom/site_xfel/content/e35165/e46561/e46883/e59447/e154136/e154138/xfel_file154216/PUMA_UM22_eng.pdf. Courtesy of Anders Madsen (European XFEL), James Moore (European XFEL), and Karina Kazarian (European XFEL).

the beginning. It includes a 170 m long accelerator line, a 130 m long undulator line, and a 30 m long experimental hall. The HX line generates 2–15 keV FEL with over 1 mJ pulse energy, 10–35 fs pulse duration, and under 20 fs arrival time jitter from 4–11 GeV electron beams. The SX line generates 0.25–1.25 keV FEL with over 1012 photons from 3 GeV e-beams. The XFEL pulses are generated at a repetition rate of 60 Hz.

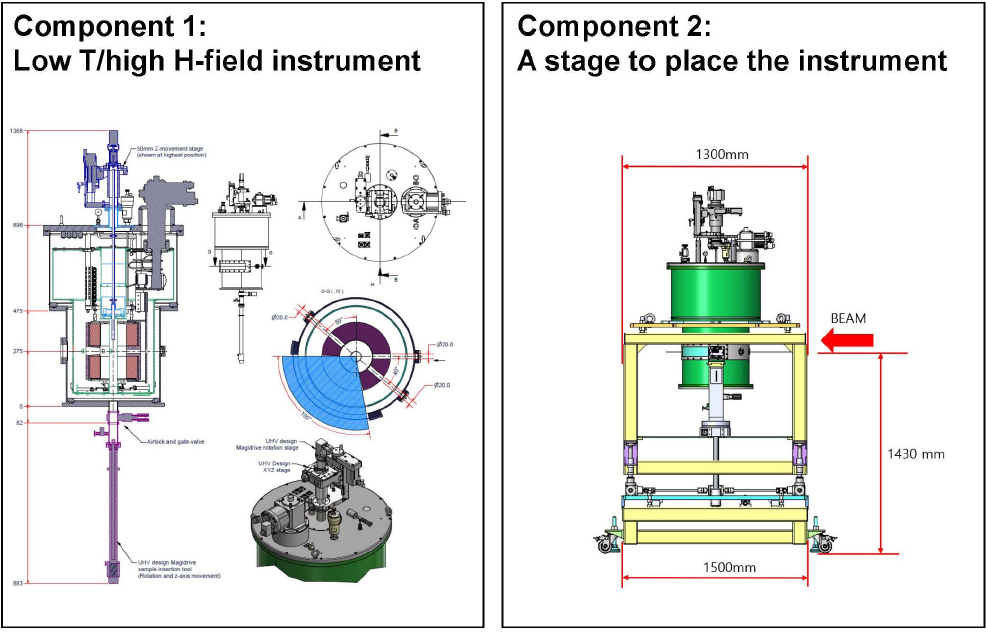

The scientists at the PAL-XFEL are currently building and commissioning a low-temperature high-magnetic-field instrument at the FXS endstation. The leading beamline scientists Dr. SaeHwan Chun is currently establishing a high-magnetic-field instrument at the hard X-ray beamline FES for research on quantum materials. The setup is shown in Figure 10-9. It will enable study of quantum materials at pulse fields of up to 9 T at 4 K. A unique feature of this experimental setup is that it also enables simultaneous laser excitation of the sample with a pump laser during collection of single-shot X-ray diffraction data as a function of the magnetic field.

SACLA

SACLA in Japan was the second hard X-ray XFEL; it started user operation in March 2012. It operates over a wide photon energy range from 4–15 keV and routinely provides ultrafast pulse duration below 10 fs at 30–60 Hz repetition rates. The short pulse duration is a unique feature of SACLA as the routine pulse duration of the other XFELs is 30–40 fs. It operates three beamlines: BL1 for soft/tender X-ray science with one endstation, and two beamlines in the hard X-ray regime where BL2 has two endstations and BL3 features three endstations. SACLA’s endstation setup is quite flexible therefore new experimental capabilities can be implemented fast.

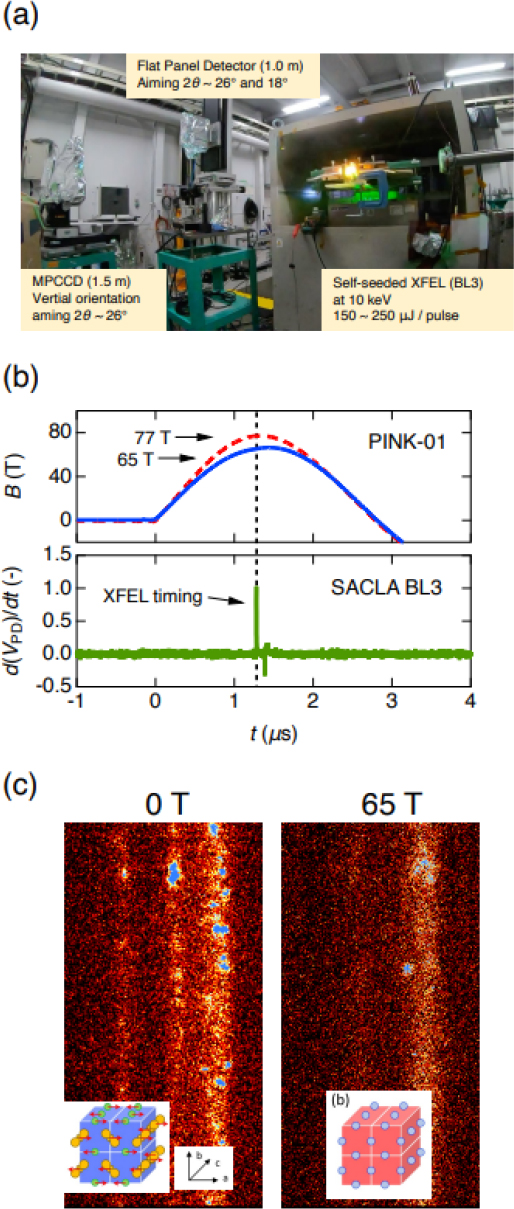

Recently, the first very exciting results were published12 from a new technological development that was established at BL3 at SACLA, where they generated 77 T using a portable pulse magnet for single-shot quantum beam experiments.

Their technology is very novel, as unique as the system that employs the single turn coil method, which is a destructive way of field generation. The system consists of a capacitor of 10.4 F, a 30 kV charger, a mono air-gap switch, a triggering system, and a magnet clamp.12 The system offers opportunities for single-shot experiments at ultrahigh magnetic fields in combinations with novel quantum beams. In their publication they report on the results of first experiments at BL3 (PINK-01) at SACLA, where they present results from a single-shot X-ray diffraction experiment at 65 T is presented (see Figure 10-10). This technology development is very

___________________

12 A. Ikeda, Y.H. Matsuda, X. Zhou, et al., 2022, “Generating 77 T Using a Portable Pulse Magnet for Single-Shot Quantum Beam Experiments,” Applied Physics Letters 120(14):142403, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0088134.

SOURCE: Courtesy of SaeHwan Chun.

SOURCE: Reprinted from A. Ikeda, Y.H. Matsuda, X. Zhou, et al., 2022, “Generating 77 T Using a Portable Pulse Magnet for Single-Shot Quantum Beam Experiments,” Applied Physics Letters 120(14), with the permissions of AIP Publishing.

exciting as it can reach extremely high magnetic fields for a short duration of microseconds that can be synchronized with the XFEL beam.

SwissFEL

SwissFEL in Switzerland is a compact 5.8 GeV machine where two electron bunches are accelerated in tandem at a 100 Hz repetition rate: the first bunch is sent to the hard X-ray Aramis beamline and the second to the soft X-ray Athos beamline. The two beamlines are operated simultaneously and can be tuned independently to optimally serve the needs of the respective experiments. Since first light in 2017, low-temperature and high-magnetic-field sample environments have been a development focus for hard condensed matter experiments. For example, transient electrical and magnetic fields are widely used in low-temperature (down to 5 K) THz pump—X-ray probe experiments at the Bernina and Furka end stations. Synchronization of high, millisecond-long magnetic field and femtosecond X-ray pulses—spear-headed at LCLS almost a decade ago13—is optimally matched to the repetition rate of SwissFEL and allows for scattering and spectroscopy experiments in distant regions of phase diagrams. At SwissFEL this approach is implemented at the hard X-ray Cristallina end station with target fields of above 50 T using solenoid “mini-coil” magnets in forward- and back-scattering geometry, as well as up to 40 T in a conventional diffraction geometry using a split-pair magnet design. These high-field capabilities are complemented by static field magnets, namely a 5 T vector magnet at Cristallina and a 1 T setup at the soft X-ray Maloja end station. Future plans also include integrating small, 5–10 T high-temperature superconducting coils into soft and hard X-ray sample manipulators.

STATUS AND CRITICAL NEEDS FOR HIGH-MAGNETIC-FIELD STUDIES AT U.S. LIGHT SOURCES

This section was based on information provided from Argonne National Laboratory.14

Unlike emerging FEL light sources, synchrotron radiation facilities around the world have decades-long history of well-established programs of utilizing high-field magnets for user’s experiments. In the United States, magnets available to users include a 3.8 T superconducting vector magnet at the 4.0.2 beamline of the

___________________

13 S. Gerber, H. Jang, H. Nojiri, et al., 2015, “Three-Dimensional Charge Density Wave Order in YBa2Cu3O6.67 at High Magnetic Fields,” Science 350(6263):949–952, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac6257.

14 Daniel Haskel, Argonne National Laboratory, email to the committee, March 29, 2024.

Advanced Light Source (ALS) for soft X-ray magnetic spectroscopy with magnetic field applied in any direction, a 6.5 T split-coil, horizontal-field magnet at the 4-ID-D beamline of the APS for hard X-ray magnetic spectroscopy, and a 2.5 T split coil HTS magnet at the 4-ID ISR beamline of the National Synchrotron Light Source-II (NSLS-II). These types of high-field magnets are commercially available, and they use NbTi, Nb3Sn, and HTS coils.

Specifics of X-ray experiments, which require large scattering angles, impose constraints on magnet design that currently limits commercial options for split coil magnets to about 14 T, and solenoid magnets to about 17 T. Despite the existence of commercial magnets providing fields significantly above 10 T, almost none of the magnets offered to users at U.S. light sources reach those fields. But in contrast, European synchrotron radiation facilities are equipped with such magnets. The European Synchrotron Radiation Facility has a 17 T solenoid magnet at one of their beamlines, and the PETRA III SR facility in Germany has a 14 T split coil vertical magnet at one of their beamlines. Furthermore, the advanced, specially designed for use at SR facilities beamline magnets are a rare sight at U.S. light sources. There are only two examples of such magnets: a ~30 T pulsed magnet (500 kJ capacitor bank) used in X-ray scattering experiments at beamline 6-ID-C of the APS,15 and the forthcoming installation of a 20 T, hour glass LTS magnet with 50 degree conical aperture developed by the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory for magnetic scattering and spectroscopy studies at the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS) High Magnetic Field X-ray beamline.16

There are several critical needs in advancing the use of and breakthrough experiments with high-field magnets at SR and FEL facilities. At least three of them are identified in this report.

The first one is the same as the need for future NMR, MRI, fusion, and accelerator magnets presented in Chapters 1, 2, 3, and 5. Advances in HTS technology would allow fabrication of compact X-ray magnets with peak fields above 20 T. The reduction in magnet size and concomitant scaling of required power and cooling infrastructure makes installation of such magnets not only more affordable but tractable in light of the limited real estate and resources available at light source beamlines. For example, the HTS split-coil vertical field magnet with very large optical access in the horizontal plane shown in Figure 10-11 would be a game-changer for studies of correlated electron and frustrated systems where field tuning can drive emergence of exotic magnetic states such as the topologically protected Kitaev Spin Liquid state.

___________________

15 Z. Islam, et al., 2009, “A Portable High-Field Pulsed Magnet System for Single-Crystal X-Ray Scattering Studies,” Review of Scientific Instruments 80:113902.

16 See Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source, “HMF—A First-of-Its-Kind X-Ray Facility,” https://www.chess.cornell.edu/hmf-first-its-kind-X-ray-facility, accessed July 1, 2024.

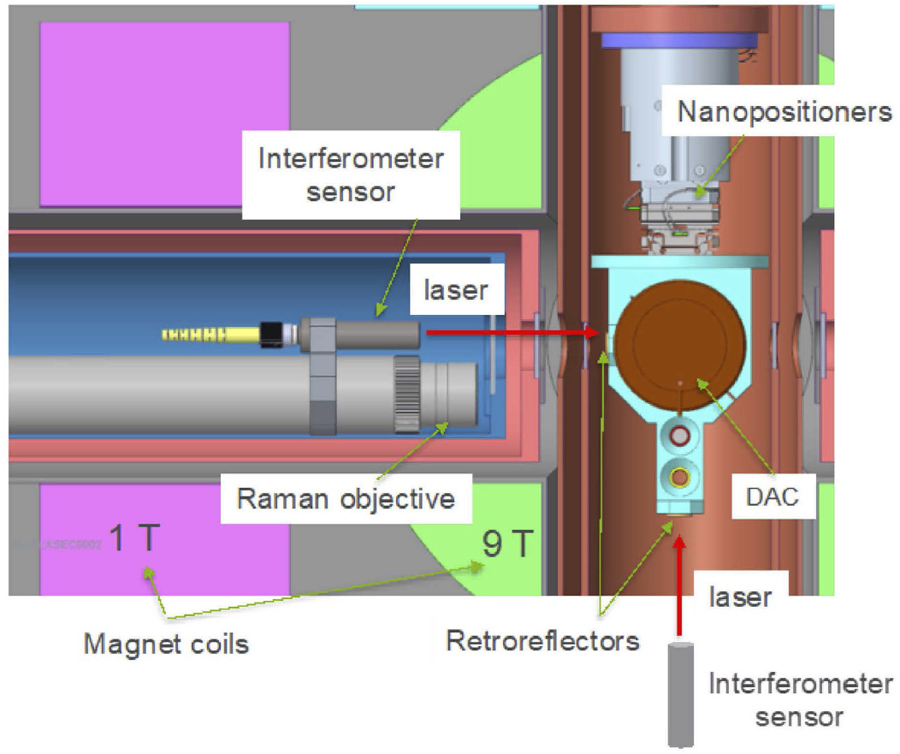

SOURCE: Courtesy of M. Bird, National High Magnetic Field Laboratory.

Another critical need is the development and construction of high field magnets with the peak field of 15 T or larger and large, ~> 3 inches. Such a magnet would accommodate a large diamond anvil cell and would enable studies of phase diagrams at simultaneously applied extremely high magnetic fields and ultra-high pressures up to several millibars. The powerful combination of ultra-high pressure, that drives new regimes of chemical bonding and high magnetic fields, which directly couple to spin degrees of freedom, would drive novel phases with implications in geosciences and planetary science, materials science, and condensed matter physics. Currently, the peak field of large bore LTS magnets with large diamond anvil cell fitted with compression and decompression He gas membranes for in-situ pressure control at low temperatures is limited by ~9 T (Figure 10-12). Providing larger magnetic fields in the 15 T or higher range while preserving a large bore size of ~3 inches will allow exploration of pressure-field phase diagrams in quantum materials with great potential for discovery of emergent phases and phenomena.

NOTE: The system allows for Raman measurements and features interferometry for nanopositioning in sub-micron X-ray beams.

SOURCE: Argonne National Laboratory, managed and operated by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

The third critical need is the design and fabrication of high field magnets with much more efficient compact closed cycle refrigeration (CCR) systems than are currently available. The motivation to develop such a system is two-fold: first, effectiveness, that is, a sufficiently powerful CCR system would provide enough cooling power for high rate of field ramp. When extremely precious beamtime at light source facilities is wasted on changing the polarity of high-field magnets, and data-taken time amounts to only a small portion of total allocated beamtime, a significant portion of potentially breakthrough experiments become inviable.

Advanced CCR systems should cut down the magnet ramping time from a few hours to tens of minutes and open the door for a new class of SR and FEL experiments with high field magnets. The second strong motivation is to convert the operation of high-field magnets to a liquid helium-free environment. As discussed in Chapter 7 of the report, the disruption in the supply and consequent cost increase of liquid helium makes such conversion not only extremely desirable but environmentally and economically sound.

One critical issue that has to be addressed while implementing CCR systems is the control of vibration. Fourth generation light sources and low emittance storage rings or FELs now deliver X-ray sources sized in the tens of microns range, which when properly demagnified with focusing optics leads to typical X-ray beams in the sub-micron to tens of nanometers range. Such small beams now enable studies of structural and electronic and magnetic inhomogeneity at near nanoscale dimensions, critical for understanding macroscopic responses and seeding new technological applications in microelectronics and quantum information sciences. It is therefore required that X-ray compatible CCR magnet systems be fabricated with vibration levels that are at least in the sub-micron range. Currently, none of the commercially available CCR magnets meet this requirement.17 Unlike other probes where sample and magnet can vibrate “in unison” without affecting the measurement (e.g., transport, magnetometry, or calorimetry measurements), X-ray measurements require sample positional stability relative to X-ray beam position. This imposes strong restrictions on vibrations during steady state operation and sample drifts during field ramping. It is therefore critical to develop CCR technologies that can both provide higher cooling power to enable ramp rates that get closer to those achieved with wet systems, while at the same time delivering a level of vibration and sample drifts relative to the laboratory reference frame in the sub-micron to tens of nanometers range, compatible with the small beam sizes available at 4th generation light sources.

FINDINGS, CONCLUSIONS, AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Finding: The development of high-magnetic-field research in combination with neutron, synchrotron radiation, and XFEL facilities is extremely important.

Finding: The United States has the world’s most powerful neutron sources; however, equipment with high magnetic fields has not changed since the NRC 2013 report.

___________________

17 Recently although new cryocoolers with vibration-free heads become commercially available. See, for example: J. Proftenhauer and X. Zhi, 2022, Handbook of Superconductivity, 2nd ed., CRC Press. Such coolers opens options for new designs of vibration-free CCR systems.

Finding: Currently there is no dedicated program on equipping the beam lines of the SNS with high magnetic fields, neither the First Target Station (FTS) nor the Second Target Station (STS), which is under construction.

Conclusion: The United States was leading the field with the first worldwide experiments conducted at LCLS; however, while the XFELs in Europe, Japan, and South Korea actively work on building new endstations to further develop these new exciting scientific capabilities, the United States has “dropped the ball” and thereby lost its leading role.

The impact that an STC can have on the development of novel technology is the BioXFEL STC, which was established in 2013 and has driven novel technology developments and breakthrough discoveries in the field of biology with XFELs, essentially establishing a new era in structural biology from static pictures to molecular movies. Driven by this STC, which includes more than 20 institutions in the United States, novel technology was developed from sample preparation, to sample delivery, beamline technology and development of novel data evaluation algorithms, leading to more than 1,100 structures determined and 960 publications in the last 10 years. The committee encourages NSF to issue a call and fund 1–2 STCs focused on technology development that combine high magnetic field with XFELs and neutron sources.

Key Recommendation 7: End stations dedicated to high-magnetic-field research at light sources (from terahertz to X rays, including the Linear Coherent Light Source at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Stanford Linear Accelerator Center) and neutron sources in the United States should be co-funded by the National Science Foundation, National Institutes of Health, and Department of Energy.

The combination of high-field magnetic science with XFELs has a huge potential but is still at the exploratory stage. The committee sees here a huge potential for future development where high magnetic fields in combination with X-ray studies with ultrashort pulse durations at XFEL could open a completely new era of scientific discoveries in a broad range of fields from the study of the influence of magnetic fields on organisms, cells, and biomolecules to the study of magnetic materials and the influence of magnetic fields on quantum materials.

Key Recommendation 6: The United States must establish its leading role in the combination of high-magnetic-field studies with X-ray free lasers (XFELs), synchrotron radiation, and neutron sources. This could be best accomplished by a National Science Foundation–supported science and technology center focused on the development of novel technology and cutting-edge science applications for quantum and atomic, molecular, and optical high-magnetic-field studies at XFELs, synchrotron accelerators, and neutron sources.

This page intentionally left blank.