The Current Status and Future Direction of High-Magnetic-Field Science and Technology in the United States (2024)

Chapter: 2 Magnetic Resonance Imaging

2

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

INTRODUCTION

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) at ultrahigh magnetic fields in humans and animals is a uniquely important tool to advance the understanding of function and physiology throughout the body in a noninvasive manner. This understanding has and continues to play fundamental roles in biology and medicine, including brain sciences, cancer, and others, and would not have happened without concomitant advances in magnet technologies. Future advances will not be possible without higher magnetic fields.

There are tens of thousands MRI systems approved for clinical use at fields strengths of 1.5 T, and 3.0 T, with a growing number of 7 T systems coming into the market. These systems are used routinely for evaluation detection of various injuries and diseases throughout the body, including cancer. The highest-field, whole-body research system available today is 11.7 T, limited by the wire and magnet technology at the scale size for human imaging, typically requiring a 900 mm bore diameter magnet. Preclinical animal systems are available commercially up to 18 T at smaller-bore diameters, while the U.S. National High Magnetic Field Laboratory (NHMFL) provides user access to rodent MRI on a custom-built 21.1 T, 105 mm bore system. Experience in these systems, as well as in commercially

available preclinical systems operating throughout the world in the 11.7–16.4 T range, have demonstrated the enormous potential that high fields can bring to a plethora of disciplines, ranging from cancer diagnosis to the understanding of neurodegenerative diseases. The advent of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) magnets operating at 28 T also predicts that preclinical systems operating in the 21–28 T range are only a matter of time and so are the unprecedented contributions that these systems could make.

Imaging human subjects at or above 11.7 T field strengths, however, requires not only advances in magnet technology, but also in radio frequency (RF) coil and in gradient coil designs. The increased field strength itself and the associated RF power deposition and acoustic noise all need to be factored into the design to ensure safety of the human subject. The imaging sequences and reconstruction methods need to be tailored to the higher frequencies arising with increasing fields for reasons of image quality and safety of the subject. But the basic underpinning of the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and the contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) arising in MRI and MRS with increasing fields is well understood and documented from the preclinical literature.

Finding: The availability of ultrahigh-field magnets leading to the design of suitable accompanying gradients and RF coils is considered a critical factor preventing more widespread exploitation of the potential that in vivo MR can deliver in biology and medicine.

IN VIVO MAGNETIC RESONANCE: SCIENCE DRIVERS

While increasing the field used in human MRI exams brings complications in terms of RF penetration and power deposition, there are several key developments that could revolutionize medical research and enlighten clinical aspects upon crossing the 10 T barrier. This follows from the extensive experience that has been gained on preclinical platforms operating in the 9.4–21 T range, as well as from the growing experience that is being gathered as the cohort of installed 7 T human MRI scanners expands worldwide. The following paragraphs briefly summarize scientific frontiers that could expand by higher fields.

MRI and Spectroscopic Imaging of Low-Gamma Nuclei

Much metabolic insight remains to be gained from magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (MRSI) use of low-gamma nuclei.1,2,3,4 Having a much lower frequency than protons, they are essentially unaffected by complications of RF penetration or RF deposition, while enjoying the improvements in sensitivity from higher-fields. In fact, expanding the use of nuclei such as 31P, 13C, 17O, and 2H to interrogate the metabolic status of tissues using intrinsic and external agents, could revolutionize molecular imaging. These probes could lead to complements to positron emission tomography (PET), which are badly needed by neurological and oncological analyses. Other critically important and relatively abundant species—including ions that like 35Cl, 39K, and 23Na—are in control of numerous homeostatic processes and would also greatly benefit from increases in magnetic field. Also, for these cases, the lower gyromagnetic ratio of the nuclei in question would result in RF irradiation at lower frequencies, providing both a safety margin and a technology used to transmit and receive signals that is well established.

Tissue-Derived Susceptibility Effects

Tissue-derived susceptibility effects can scale faster than linear with increased field strength.5 As clinical scanners transition from 3 T to 7 T, this has been shown to be highly beneficial for evidencing brain lesions such as those associated with epilepsy and neurodegeneration.6 The future of personalized medicine may well depend on porting this kind of analysis and advantages to higher fields. Indeed, the

___________________

1 T.F. Budinger, M.D. Bird, L. Frydman, et al., 2016, “Toward 20 T Magnetic Resonance for Human Brain Studies: Opportunities for Discovery and Neuroscience Rationale,” Magnetic Resonance Materials in Physics, Biology and Medicine 29:617–639.

2 M.E. Ladd, P. Bachert, M. Meyerspeer, et al., 2018, “Pros and Cons of Ultra-High-Field MRI/MRS for Human Application,” Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy 109:1–50.

3 H.M. De Feyter and R.A. de Graaf, 2021, “Deuterium Metabolic Imaging—Back to the Future,” Journal of Magnetic Resonance 326:106932, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmr.2021.106932.

4 L.V. Gast, T. Platt, A.M. Nagel, and T. Gerhalter, 2023, “Recent Technical Developments and Clinical Research-Applications of Sodium (23Na) MRI,” Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy 138–139:1–51.

5 B.V. Ineichen, E.S. Beck, M. Piccirelli, and D.S. Reich, 2021, “New Prospects for Ultra-High-Field Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Multiple Sclerosis,” Investigative Radiology 56(11):773–784; K.M. Bloch and B.A. Poser, 2021, “Benefits, Challenges, and Applications of Ultra-High Field Magnetic Resonance,” Advances in Magnetic Resonance Technology and Applications 4:553–571.

6 B. Vachha and S.Y. Huang, 2021, “MRI with Ultrahigh Field Strength and High-Performance Gradients: Challenges and Opportunities for Clinical Neuroimaging at 7 T and Beyond,” European Radiology Experimental 5:1–18; C. Rondinoni, C. Magnun, A. Vallota da Silva, H.M. Heinsen, and E. Amaro, Jr., 2021, “Epilepsy Under the Scope of Ultra-High Field MRI,” Epilepsy & Behavior 121:106366.

latter benefits susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) measurements by providing both a higher overall SNR, as well as providing larger and easier to observe susceptibility distortions for increasingly smaller brain lesions. Also related to these effects are the responses observed in functional MRI (fMRI), which research has also shown increases nearly quadratically with field strength.7

Proton Spectroscopic Imaging

Less affected by power deposition effects and still benefiting supra-linearly from increased magnetic fields are applications of 1H spectroscopic imaging. Growing 7 T experience has shown, also mostly in the brain, that multiple sclerosis and cancer genetic markers can become available from higher field 1H spectral measurements.8 The reasons for these benefits are numerous, including a simplification of J-coupled structures, easier achievement of water suppression, a lengthening in T1 and decrease in T2 that affects the water but not metabolic reporters and hence facilitates the latter observation, and an overall improvement in sensitivity. All these synergistic effects greatly facilitate spectroscopic experiments, which could thus become decisive factors in guiding the best possible treatment for a variety of diseases.

Understanding the Structure and Function of the Human Brain

Ultrahigh-field MRI is a critical tool for advancing our understanding of the structure and function of the human brain. National and international research activities outlined by the NIH Brain Initiative9,10 bear witness to this relevance. Ultrahigh-field MRI has been identified as fulfilling critical needs for understanding the networks, architectures, and functions of the brain at the mesoscopic scale.

The mesoscopic scale refers to neuronal ensembles consisting of several hundreds or thousands of neurons with similar functional properties, which constitute a minimal cortical unit of operation and are repeated multiple times in each cortical

___________________

7 K. Uğurbil, 2021, “Ultrahigh Field and Ultrahigh Resolution fMRI,” Current Opinion in Biomedical Engineering 18:100288; J. Yang, L. Huber, Y. Yu, and P.A. Bandettini, 2021, “Linking Cortical Circuit Models to Human Cognition with Laminar fMRI,” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 128:467–478.

8 A. Shaffer, S.S. Kwok, A. Naik, et al., 2022, “Ultra-High-Field MRI in the Diagnosis and Management of Gliomas: A Systematic Review,” Frontiers in Neurology 13:857825.

9 National Institutes of Health (NIH), 2024a, “NIH BRAIN Initiative Reports,” https://braininitiative.nih.gov/vision/nih-brain-initiative-reports.

10 NIH, 2024b, “BRAIN 2025: A Scientific Vision,” https://braininitiative.nih.gov/vision/nih-brain-initiative-reports/brain-2025-scientific-vision.

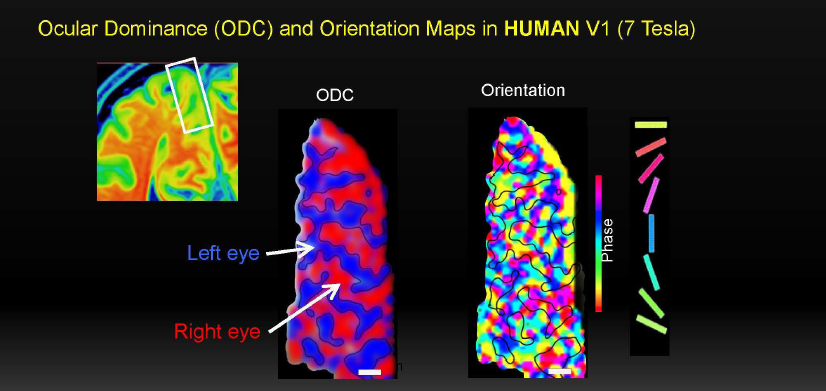

area.11 Cortical columns, such as the ocular dominance (ODC) and orientation columns of the primary visual cortex,12,13 are examples of such organizations (Figure 2-1). The ability to interrogate neuronal activity of such elementary neuronal organizations noninvasively by fMRI, and to scale up such information to whole brain networks, is essential for understanding neurobiology in any species, but particularly in the study of the human brain in health and disease.

The NIH Brain 2.014 initiative set an aggressive goal of improving fMRI resolution to 0.01 μL (~0.2 mm isotropic resolution). The sensitivity at clinical MRI systems field strengths of 1.5 T and 3.0 T is insufficient to visualize the structure and fMRI activity at the necessary spatial resolution. With the introduction of 7 T field strengths, resolution is improved and there are numerous and ever-increasing numbers of submillimeter-resolution human neuroscience applications,15,16,17,18 but the results still fall well short of the resolution and sensitivity targeted by the Brain 2.0 initiative.

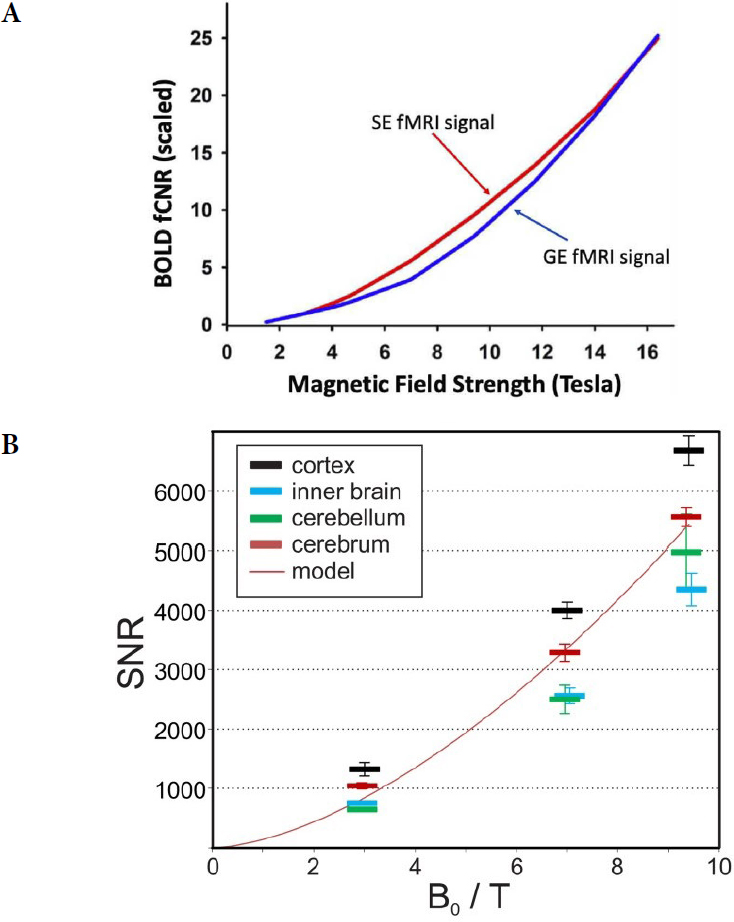

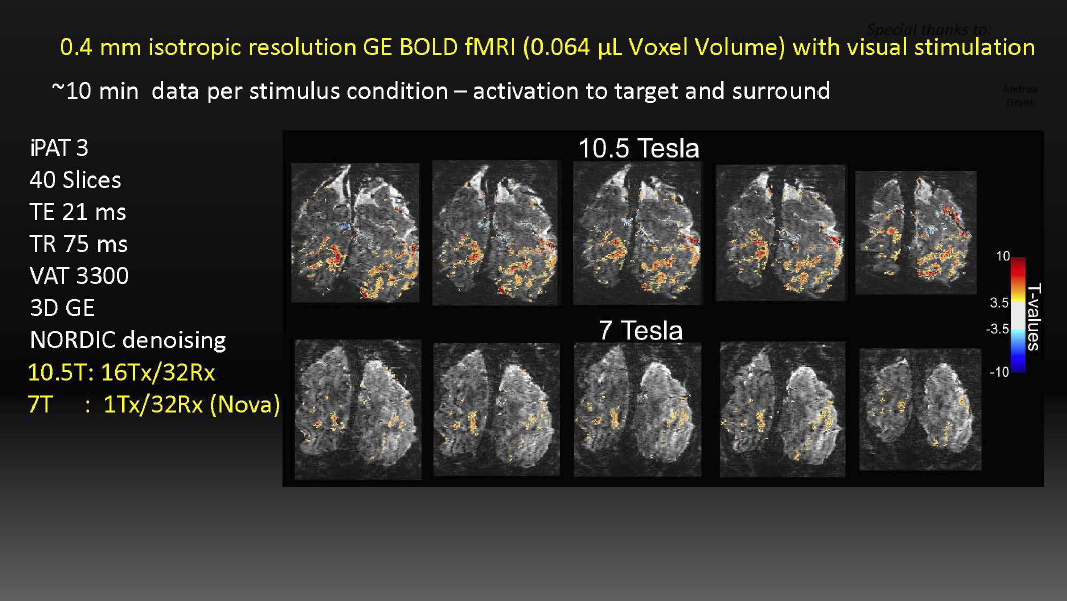

In fMRI images, SNR and contrast in fMRI signals have been demonstrated to increase with field strength more rapidly than a linear increase (Figure 2-2)—demonstrating the importance of increasing the field strength. The Center for Magnetic Resonance Research (CMRR) group at the University of Minnesota19 compared fMRI at 10.5 T and 7 T using identical hardware (except for the magnetic field), as well as acquisition methods, spatial resolution, and data acquisition time, thus demonstrating that functional signals are detected at 10.5 T, but not at 7 T, at high

___________________

11 R. Lorente de Nó, 1938, “Architectonics and Structure of the Cerebral Cortex,” In Physiology of the Nervous System, edited by J.F. Fulton, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 291–330.

12 D.H. Hubel, T.N. Wiesel, and M.P. Stryker, 1977, “Orientation Columns in Macaque Monkey Visual Cortex Demonstrated by the 2-Deoxyglucose Autoradiographic Technique,” Nature 269(5626):328–330.

13 D.H. Hubel, T.N. Wiesel, and M.P. Stryker, 1978, “Anatomical Demonstration of Orientation Columns in Macaque Monkey,” Journal of Comparative Neurology 177(3):361–379.

14 NIH, 2024a, “BRAIN 2.0: From Cells to Circuits, Toward Cures,” https://braininitiative.nih.gov/vision/nih-brain-initiative-reports/brain-20-report-cells-circuits-toward-cures.

15 K. Uğurbil, 2018, “Imaging at Ultrahigh Magnetic Fields: History, Challenges, and Solutions,” Neuroimage 168:7–32.

16 S.O. Dumoulin, A. Fracasso, W. van der Zwaag, J.C.W. Siero, and N. Petridou, 2018, “Ultra-High Field MRI: Advancing Systems Neuroscience Towards Mesoscopic Human Brain Function,” Neuroimage 168:345–357.

17 F. De Martino, E. Yacoub, V. Kemper, et al., 2018, “The Impact of Ultra-High Field MRI on Cognitive and Computational Neuroimaging,” Neuroimage 168:366–382.

18 L. Huber, E.S. Finn, Y. Chai, et al., 2021, “Layer-Dependent Functional Connectivity Methods,” Progress in Neurobiology 207:101835.

19 N. Tavaf, R.L. Lagore, S. Jungst, et al., 2021, “A Self-Decoupled 32-Channel Receive Array for Human-Brain MRI at 10.5 T,” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 86(3):1759–1772, https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.28788.

SOURCES: Courtesy of Kamil Uğurbil, University of Minnesota, presentation to the committee, September 1, 2023. ODC and Orientation images from E. Yacoub, N. Harel, and K. Uğurbil, 2008, “High-Field fMRI Unveils Orientation Columns in Humans,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105(30):10607–10612.

resolution levels (0.4 mm isotropic, 0.06 μL voxel volume, see Figure 2-3) and at the statistical significance threshold employed.

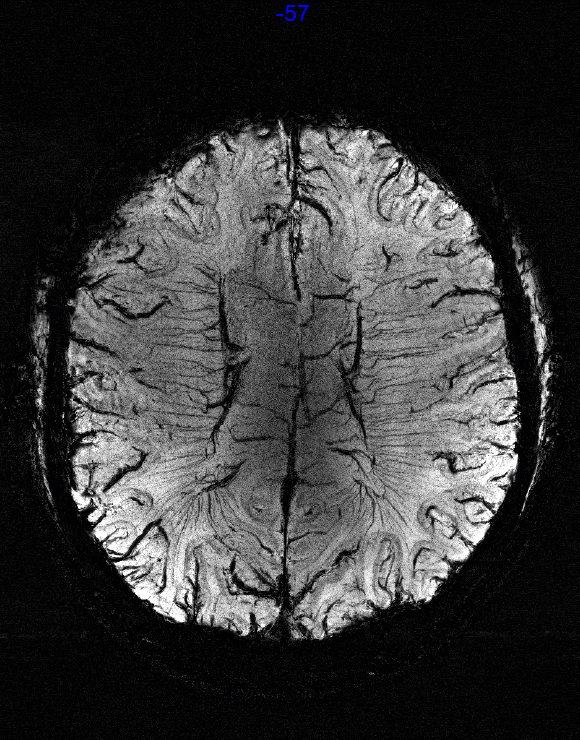

Structural susceptibility weighted images at 10.5 T shown in Figure 2-4 depicts venous blood vessels at unprecedented resolution of 0.2 × 0.2 × 1.3 mm3.20 In addition, the CMRR research group21 has demonstrated functional imaging of brain activity at 0.35 mm isotropic resolution.

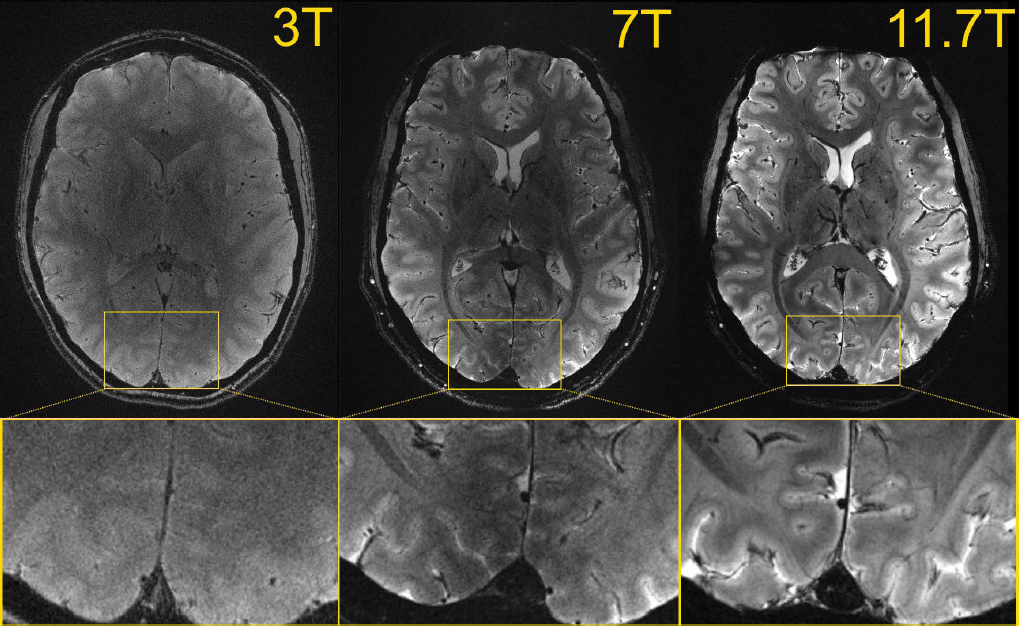

Recent imaging results from the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA) Iseult 11.7 T MRI shows impressive contrast and detail using a variety of MRI techniques.22 Figure 2-5 shows the gains in spatial resolution and unprecedented contrast that can be obtained at these ultrahigh magnetic fields.

The image results at 10.5 T and 11.7 T by the CMRR and CEA groups show that the technical aspects of human imaging at these very high magnet fields have solutions, and the prospects for human imaging at even higher fields is promising. Imaging at 14 T or above may make it possible to image at or below the desired

___________________

20 R. LaGore, 2023, 2023 ISMRM & ISMRT Annual Meeting & Exhibition, June 3–8. (LaGore et al., SMRM 2023, #1059).

21 K. Uğurbil, presentation to the committee.

22 N. Boulant, F. Mauconduit, V. Gras, et al., 2024, “First In Vivo Images of the Human Brain Revealed with the Iseult 11.7T MRI Scanner,” PREPRINT (Version 1) available at Research Square, https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3931535/v1.

NOTE: GE, gradient echo; SE, spin echo.

SOURCES: (A) Reprinted from K. Uğurbil, 2021, “Ultrahigh Field and Ultrahigh Resolution fMRI,” Current Opinion in Biomedical Engineering 18:100288, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobme.2021.100288, with permission from Elsevier. (B) R. Pohmann, O. Speck, and K. Scheffler, 2016, “Signal-to-Noise Ratio and MR Tissue Parameters in Human Brain Imaging at 3, 7, and 9.4 Tesla Using Current Receive Coil Arrays,” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 75(2):801–809, https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.25677, © 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

NOTES: BOLD, blood oxygen level dependent. The neuronal activity is depicted in color superimposed on the anatomical image of the brain slices (in gray scale) where the activity was detected.

SOURCE: Courtesy of Kamil Uğurbil, University of Minnesota, presentation to the committee, September 1, 2023.

SOURCE: Courtesy of Russell Lagore, 2023, presentation #1059 to the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine Annual Meeting, June.

~0.2 mm isotropic resolutions. MRI is a very diverse technology with a variety of methods to produce structural, physiological, and functional contrast. Combination with advanced sampling and motion-correcting techniques with MRI at higher fields projected to increase SNR more rapidly than linear with field,23 as shown in Figure 2-1. The CNR of fMRI and the blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) effect increases more rapidly than linear with field strength as in Figure 2-2, enabling the detection of laminar structures in the mesoscopic scale to whole brain networks.24,25

___________________

23 R. Pohmann, O. Speck, and K. Scheffler, 2016, “Signal-to-Noise Ratio and MR Tissue Parameters in Human Brain Imaging at 3, 7, and 9.4 Tesla Using Current Receive Coil Arrays,” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 75(2):801–809, https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.25677.

24 K. Uğurbil, 2021, “Ultrahigh Field and Ultrahigh Resolution fMRI,” Current Opinion in Biomedical Engineering 18:100288; J. Yang, L. Huber, Y. Yu, and P.A. Bandettini, 2021, “Linking Cortical Circuit Models to Human Cognition with Laminar fMRI,” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 128:467–478.

25 D.A. Feinberg, A.J.S. Beckett, A.T. Vu, et al., 2023, “Next-Generation MRI Scanner Designed for Ultra-High-Resolution Human Brain Imaging at 7 Tesla,” Nature Methods 20(12):2048–2057.

NOTE: Details within the cortical ribbon become clearly visible at 11.7 T and not at lower field strength, owing to poorer signal and contrast to noise ratios.

SOURCE: N. Boulant, F. Mauconduit, V. Gras, et al., 2024, “First In Vivo Images of the Human Brain Revealed with the Iseult 11.7T MRI Scanner,” Preprint (Version 1) available at Research Square, https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3931535/v1. Courtesy of NeuroSpin, CEA, University of Paris-Saclay.

HUMAN MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING FIELD STRENGTHS: AVAILABLE AND PLANNED

Most superconducting MRI systems approved for clinical use are at fields strengths of 1.5 T and 3.0 T, with a growing number of 7 T systems coming into the market. The 1.5 T and 3.0 T systems are typically referred to as high field by the MRI community, and 7 T and above is considered ultrahigh field. However, because MRI at 7 T is used clinically and approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Union (EU) for imaging the head, arms, and legs, the term “ultrahigh field” in this report is reserved for human MRI systems above the 8 T value.26 These ultrahigh field systems are limited to research use only owing to the safety concerns. These concerns include effects of the static magnetic

___________________

26 “Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff – Criteria for Significant Risk Investigations of Magnetic Resonance Diagnostic Devices” issued on July 14, 2003.

field itself27 and the higher frequency of 1H operation, creating risks for high-local power deposition of the transmitted fields into tissue. It should be noted however, that imaging portions of the torso at 7 T is limited to research only because of the larger anatomy of the body and its interaction with the transmit and receive fields at the higher frequencies, resulting in associated safety and image quality issues. There are eight human-capable ultrahigh-field MRI systems worldwide that are active, in the process, or planned with funding (Table 2-128). Two such systems are in the United States, with the University of Minnesota 10.5 T magnet currently active and having a significant publication record. The NIH 11.7 T29 system delivered in 2019 experienced a failure during initial testing, but after repair, it is expected to be operational and become an important resource. This demonstrates the tremendous engineering challenges and the lost opportunity to science when such a failure occurs. There is also a 9.4 T whole body magnet at Maastricht University, with dedicated head gradient coil for imaging the brain.30

Although research in the brain is a key driver of systems at 10.5 T or greater, some of the current and proposed systems at these ultra-high fields are sized to support research in all parts of the human body, offering the greatest potential for research given the limited number of systems. Indeed, much of the research involving MRI and MRSI is outside the brain, and therefore research leaders31 recommend ultrahigh-field research magnets to be of a size that allows for studies of all parts of the anatomy with the necessary space for gradient coils, RF coil arrays, shim coils, and other potential ancillary equipment important for the research. A recent article describes the rationale and plans for a German 14 T high-temperature superconducting (HTS)-based MRI magnet,32 stating “a clear commitment to pursue a whole-body design to permit the investigation of scientific questions in the brain, trunk, and limbs.”

Numerous magnets at 11.7 T and higher are planned for Europe and Asia. In addition to the Iseult magnet, there is funding for an 11.7 T system in the University

___________________

27 A. Grant, G.J. Metzger, P.-F. Van de Moortele, et al., 2020, “10.5 T MRI Static Field Effects on Human Cognitive, Vestibular, and Physiological Function,” Magnetic Resonance Imaging 73:163–176, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mri.2020.08.004.

28 Four of the systems in Table 2-1 share common design elements/technology. MAGNEX was purchased by Agilent and the ASG design are copies of an Agilent design.

29 NIH Record, 2019, “Another Huge MRI Magnet Delivered to NIH,” https://nihrecord.nih.gov/2019/04/19/another-huge-mri-magnet-delivered-nih.

30 D. Ivanov, F. De Martino, E. Formisano, et al., 2023, “Magnetic Resonance Imaging at 9.4 T: The Maastricht Journey,” Magnetic Resonance Materials in Physics, Biology and Medicine 36(2):159–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10334-023-01080-z.

31 Uğurbil and Rosen presentation to the committee.

32 Y. Li and S. Roell, 2021, “Key Designs of a Short-Bore and Cryogen-Free High Temperature Superconducting Magnet System for 14 T Whole-Body MRI,” Superconductor Science and Technology 34(12):125005.

of Nottingham,33 and the 14 T in the Netherlands.34 The publication record indicates Germany35 and China36 will likely follow with their own 14 T national efforts; no such new systems are planned for the United States. Pushing to even higher fields will require new design methodologies and wire technology.

Regardless of their location, facilities conducting human-oriented research at these ultrahigh magnetic fields require a multi-disciplinary staff of medical physicists, engineers, support staff, and medical professionals. These are usually embedded within the frameworks of larger medical centers, research institutions, or university complexes, requiring significant and sustained funding over many years.

PRECLINICAL MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING

Preclinical animal MRI systems are more prevalent at field strengths greater than 7 T in large part owing to their smaller physical size simplifying the magnet engineering and construction. Systems at 11.7 T and below are widely available commercially with bore sizes up to 200 mm. There are more than a dozen preclinical systems in operation at or above 11.7 T at smaller bore sizes, including 11.7, 15.2, and 16.4 T preclinical systems operating in the United States. A similar bore instrument is slated to be installed in Portugal, operating at 18 T.37 This widespread availability reflects the much smaller bore required for performing MRI research on animal systems; in fact, several vertical wide bore ultrahigh-field systems operating at or above 14.1 T have been instrumental in mouse-based physiological research. NHMFL in Tallahassee provides user access to one such system, with a custom-designed 21.1 T 105 mm bore magnet serving the national and international scientific communities.

___________________

33 ByWire, 2022, “University of Nottingham Awarded £29 Million for UK’s Most Powerful MRI Scanner,” West Bridgford Wire, https://westbridgfordwire.com/university-of-nottingham-awarded-29-million-for-uks-most-powerful-mri-scanner.

34 Y. Li and S. Roell, 2021, “Key Designs of a Short-Bore and Cryogen-Free High Temperature Superconducting Magnet System for 14 T Whole-Body MRI,” Superconductor Science and Technology 34(12):125005.

35 M.E. Ladd, H.H. Quick, O. Speck, et al., 2023, “Germany’s Journey Toward 14 Tesla Human Magnetic Resonance,” Magnetic Resonance Materials in Physics, Biology and Medicine 36:191–210, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10334-023-01085-z.

36 Y. Wang, Q. Wang, H. Wang, et al., 2022, “Actively-Shielded Ultrahigh Field MRI/NMR Superconducting Magnet Design,” Superconductor Science and Technology 35:014001, https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6668/ac370e.

37 Bruker, 2024, “Bruker and Champalimaud Foundation Announce Collaboration to Develop Novel Ultra-High Field 18 Tesla Preclinical MRI System and Applications,” https://www.bruker.com/en/news-and-events/news/2019/bruker-and-champalimaud-foundation-announce-collaboration-to-develop-novel-ultra-high-field-18-tesla-preclinical-mri-system-and-application.html.

TABLE 2-1 Human-Capable Magnetic Resonance Imaging Systems Active Worldwide, in Process, or Planned with Funding at 10.5 T or Greater

| Systema | Magnet | Bore | Wire Type | Active Research | Magnet Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of Minnesota, United Statesb | 10.5 T | 88 cm | NiTI | Operational, Human imaging active | Agilent/Magnex |

| NIH Intramural Researchc System, United States | 11.7 T | 68 cm | NiTI | Magnet damaged, rebuilt | ASG |

| Neurospin, Franced,e | 11.7 T | 90 cm | NiTI | Operational. Human imaging active | CEA France, installed July 18, 2019 |

| Gachon University, South Koreaf | 11.7 T | 68 cm | NiTI | Magnet at Field, no published results | ASG |

| University of Nottingham, United Kingdomg | 11.7 T | 83 cm | NiTI | Funding announced UK June 2022 | Tesla Engineering, UK |

| University of Science and Technology, Hefei, China | 10.5 T | 88 cm | NiTI | Planned, under development | ASG |

| Nijmegen, Netherlands | 14 T | 82 cm | HTS | Funding Announced Netherlands Feb 2023 | Neoscan received order in Sept 2023 |

| Maastricht University, Netherlandsh | 9.4 T | NiTi | Operational, body size with head gradient | Magnex |

a Li, Y., and S. Roell, 2021, “Key Designs of a Short-Bore and Cryogen-Free High Temperature Superconducting Magnet System for 14 T Whole-Body MRI,” Superconductor Science and Technology 34(12):125005, https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6668/ac2ec8.

b Uğurbil, K., P.-F. Van de Moortele, A. Grant, E.J. Auerbach, A. Ertürk, R. Lagore, J.M. Ellermann, X. He, G. Adriany, and G.J. Metzger, 2021, “Progress in Imaging the Human Torso at the Ultrahigh Fields of 7 and 10.5 T,” Magnetic Resonance Imaging Clinics 29(1):e1–e19.

c National Institutes of Health, 2024, “Laboratory of Functional and Molecular Imaging (LFMI),” https://research.ninds.nih.gov/laboratory-functional-and-molecular-imaging-lfmi.

d Boulant, N., and L. Quettier, 2023, “Commissioning of the Iseult CEA 11.7 T Whole-Body MRI: Current Status, Gradient–Magnet Interaction Tests and First Imaging Experience,” Magnetic Resonance Materials in Physics, Biology and Medicine 36(2):175–189, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10334-023-01063-5.

e Boulant, N., F. Mauconduit, V. Gras, et al., 2024, “First In Vivo Images of the Human Brain Revealed with the Iseult 11.7T MRI Scanner,” PREPRINT (Version 1) available at Research Square, https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3931535/v1.

f Gachon University, 2024, “3 Research Institutes Equipped with World Class Research Capacity,” https://www.gachon.ac.kr/eng/7498/subview.do.

g University of Nottingham, 2024, “Sir Peter Mansfield Imaging Centre,” https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/research/groups/spmic/research/national-facility-for-ultra-high-field-11.7t-human-mri-scanning/index.aspx.

h Ivanov, D., F. De Martino, E. Formisano, F.J. Fritz, R. Goebel, L. Huber, S. Kashyap, V.G. Kemper, D. Kurban, and A. Roebroeck, 2023, “Magnetic Resonance Imaging at 9.4 T: The Maastricht Journey,” Magnetic Resonance Materials in Physics, Biology and Medicine 36(2):159–173, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10334-023-01080-4.

MAGENTIC RESONANCE IMAGING MAGNET FIELD STRENGTH LIMITS

Clinical MRI systems at 1.5 T, 3.0 T, and 7.0 T, as well as the ultrahigh-field research systems identified in Table 2-1 at 10.5 T (University of Minnesota) and 11.7 T (NIH and NeuroSpin), use NbTi38 wire. The MRI industry is the largest consumer of NbTi superconducting wire. The wire’s much lower cost and availability, along with its mechanical properties, result in simpler manufacturing processes for fabrication. The DOE-sponsored effort to build accelerator magnets in the 1970s for the tevatron accelerator39,40,41 resulted in advances in the wire technology and sources of production that enabled the clinical MRI industry that we all benefit from today. Development of accelerator and fusion magnets utilizing HTS wire could serve as the medical technology for preclinical and clinical MRI systems of the future.

Beyond 11.7 T for Whole-Body Magnets

Pushing field strengths above 11.7 T at whole-body scale with bore sizes ~900 mm, requires use of alternative wire technology and advances in engineering design. Nb3Sn42 wire technology is relatively mature and used in the manufacture of preclinical animal MRI magnets at smaller bore sizes, but there is no planned use of the wire to design magnets of whole-body scale. Preclinical magnet design above 11.7 T is a combination of a smaller inner coil using Nb3Sn wire and an outer larger coil of NbTi wire, the sum of which produces the desired field. Unlike NbTi wire that is flexible and can be wound after formation into a superconducting wire, Nb3Sn technology typically requires a wind first and then reaction at higher temperature to become a superconductor. This adds significant equipment investment and engineering effort that is especially challenging at the larger magnet bore sizes of ~900 mm. The design of whole-body MRI magnets above 11.7 T using Nb3Sn should be possible as outlined in a design study from the Chinese National

___________________

38 P.J. Lee and B. Strauss, 2011, 100 Years of Superconductivity, H. Rogalla, and P.H. Kes, eds., Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, https://fs.magnet.fsu.edu/~lee/superconductor-history_files/Centennial_Supplemental/11_2_Nb-Ti_from_beginnings_to_perfection-fullreferences.pdf.

39 Ibid.

40 Imperial College of London, 2024, “Professor David Larbalestier,” https://www.imperial.ac.uk/stories/alumni-awards-2024-david.

41 Fermi Laboratory, 2024, “Tevatron,” https://www.fnal.gov/pub/tevatron/tevatron-accelerator.html.

42 E. Barzi and A.V. Zlobin, 2019, “Nb3Sn Wires and Cables for High-Field Accelerator Magnets,” Pp. 23–51 in Nb3Sn Accelerator Magnets. Particle Acceleration and Detection, D. Schoerling and A. Zlobin, eds., Cham, Switzerland: Springer, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-16118-7_2.

Academy,43 although none is planned currently, and the cost and engineering effort is unknown.

HTS materials may be an important alternative to allow for design of systems above 11.7 T, but the technology is less mature. One MRI system at 14 T has been funded by a Dutch consortium utilizing HTS conductor,44 the design of which has yet to be demonstrated. A recent article describes the rationale and plans for a German 14 T HTS-based MRI magnet.45 According to an industry representative from one of the major MRI manufactures, there are no near-term plans to adopt HTS for use in clinical MRI systems.46 Assuming availability, a factor of more than 10 in cost reductions would be required for the industry to consider its use. A further barrier to adoption, assuming wire availability, is the investments in plant and equipment that has been optimized for different wire technology over the past 40 years.

Any new ultrahigh-field whole-body magnet above 11.7 T is likely to be designed and built by private industry under contract and as a one-of-a-kind or low-volume product. The amount of wire required would be insufficient to support and maintain the research and development investments necessary by third-party wire manufacturers. Other potential industrial or research applications with sustained volume, such as wind power,47 fusion, and accelerators, could be the drivers of the wire technology that might be adaptable for MRI. Certain types of HTS wire technology, for example rare-earth barium copper oxide (REBCO), are being scaled in manufacture for multiple planned fusion devices with the potential to be adapted for use in MRI. Wire made of REBCO allows for winding after reacting, which could greatly simplify design when compared with Nb3Sn that use react-after-wind technology. But REBCO or other HTS materials may require adaptation for use in design of MRI systems which have additional requirements of field stability, persistent operation, and field uniformity.

___________________

43 Y. Wang, Q. Wang, H. Wang, et al., 2021, “Actively-Shielded Ultrahigh Field MRI/NMR Superconducting Magnet Design,” Superconductor Science and Technology 35(1):014001, https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6668/ac370e.

44 Y. Li and S. Roell, 2021, “Key Designs of a Short-Bore and Cryogen-Free High Temperature Superconducting Magnet System for 14 T Whole-Body MRI,” Superconductor Science and Technology 34(12):125005, https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6668/ac2ec8.

45 M.E. Ladd, H.H. Quick, O. Speck, et al., 2023, “Germany’s Journey Toward 14 Tesla Human Magnetic Resonance,” Magnetic Resonance Materials in Physics, Biology and Medicine 36(2):191–210, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10334-023-01085-z.

46 GE Healthcare Stuart Feltham presentation to the committee.

47 I. Kolchanova and V. Poltavets, 2021, “Superconducting Generators for Wind Turbines,” International Conference on Electrotechnical Complexes and Systems (ICOECS), Ufa, Russian Federation, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICOECS52783.2021.9657294, pp. 529–533.

Helium Consumption

The cooldown of a clinical MRI magnet and initial filling of the reservoir can require thousands of liters of liquid helium. The manufacturers of clinical MRI systems have installed helium liquefaction capability with recovery systems at their magnet factory. The magnets are shipped cold and prefilled with about 1,500 L of helium, requiring a small top off at installation. Once installed at the customer site, the helium is reliquefied by a cryo-cooler mounted on the magnet operating just above atmospheric pressure at ~4.2 K, achieving a zero loss of helium during normal operation.

In contrast to clinical MRI up to 7 T, the pressure in the helium vessel of ultrahigh-field magnets operating at 10.5 T and 11.7 T is lowered via pumping to decrease the magnet temperature and thermal margin for operating the NbTi conductor at these fields. This results in continuous loss of helium, requiring replenishment or onsite helium recovery and reliquefication. In addition, the large mass of these ultrahigh-field magnets requires mechanical support and shipment at room temperature, resulting in consumption of large quantities of helium for initial cooldown.

Finding: HTS conductor-based MRI systems operating at ultrahigh field at 10.5 T and above may have lower thermal mass and potentially allow operation at 4.2 K or higher temperature with simpler cooling systems and zero boiloff.

SUMMARY

Status of Whole-Body Ultrahigh-Field MRI Magnets

MRI and MRS at high magnetic fields in humans and animals are important, irreplaceable tools to advance both the understanding of tissue structure and physiology, as well as of health and treatment of disease in humans. Helped by recently received European Union and FDA approvals for clinical use for brain and extremity, 7 T human MRI systems are becoming increasingly available worldwide.

Finding: Two out of the eight ultrahigh-field (>7 T) human systems are based in the United States, with a 10.5 T system at the University of Minnesota and the 11.7 T MRI at NIH. There are six additional human magnets, noted in Table 2-1, in operation or planned for operation outside the United States.

Finding: Apart from the one 14 T48 magnet (see Table 2-1), with plans to design the magnet using HTS materials, the remaining ultrahigh-field human MRI systems at 11.7 T above have relied on NbTi wire technology. None of the magnets were designed or manufactured in the United States, even although much of NbTi wire technology derived from superconducting wire research performed in the United States for accelerators science.49

Finding: MRI facilities conducting research at ultrahigh magnetic fields require a multi-disciplinary staff of medical physicists, engineers, support staff, and medical professionals. The ability to maintain stable funding for such MRI facilities over many years, whether they are for humans or animals, is very challenging with the current funding mechanisms in the United States.

Ultrahigh-Field Magnetic Resonance Imaging: The Path Forward

The path forward for human ultrahigh-field MRI requires the development of wire and magnet technology capable of operating at large bore sizes above 11.7 T. To allow for imaging and spectroscopy in all parts of the anatomy requires these magnet bore sizes to be ~900 mm. Preclinical ultrahigh-field animal systems require strengths above 21 T, and accommodating animals requires ~110 mm bores for inserting the gradients and the RF components. The recent availability of commercial narrow-bore (54 mm) 28 T NMR systems by Bruker50 and the 2017 commissioning of the all-superconducting 32 T magnet at NHMFL51—both incorporating HTS REBCO-based technologies bode well for the realization of such MRI systems.

Conclusion: Although many of the research goals for MRI systems above the 11.7 T focus on the brain, using protons, the increased field benefits in vivo studies of numerous nuclear species such as 31P, 13C, or 23Na. Although less abundant and less sensitive than protons, these and other species can provide unique probes into

___________________

48 Y. Li and S. Roell, 2021, “Key Designs of a Short-Bore and Cryogen-Free High Temperature Superconducting Magnet System for 14 T Whole-Body MRI,” Superconductor Science and Technology 34(12):125005, https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6668/ac2ec8.

49 P.J. Lee and B. Strauss, 2011, 100 Years of Superconductivity, H. Rogalla, and P.H. Kes, eds., Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, https://fs.magnet.fsu.edu/~lee/superconductor-history_files/Centennial_Supplemental/11_2_Nb-Ti_from_beginnings_to_perfection-fullreferences.pdf.

50 Bruker, 2024, “Differentiated High Value Life Science Research and Diagnostics Solutions,” https://www.bruker.com/en.html.

51 H.W. Weijers, W.D. Markiewicz, A.V. Gavrilin, et al., 2017, “The 32 T Superconducting Magnet Achieves Full Field,” National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, 2017 Annual Research Report, https://nationalmaglab.org/media/mtwcgu4w/2017-nhmfl-report399.pdf.

metabolic and transport functions throughout the organism, including all parts of the human body.

Conclusion: Breaking through the 11.7 T field strength barrier for human-size systems or the 21 T field for preclinical systems requires advances in wire technology and engineering design. Although Nb3Sn wire technology could potentially be used to design these larger preclinical and body MRI magnets above 11.7 T, none is currently planned. The HTS wire technology is advancing quickly, with one 14 T magnet planned at whole-body scale. There are multiple planned fusion devices with scale size equal or greater than whole-body MRI showing the potential, but they will require further development for use in design of MRI systems, which have different requirements, such as field stability, persistent operation, and field uniformity.

Conclusion: The design and manufacture of new preclinical, large-bore animal or whole-body MRI systems will be conducted by industry with private or public funding. The magnet companies rely on third parties and adapt their designs to currently available wire technology. The amazing success of the MRI superconducting magnet industry using NbTi can trace its foundation to the wire development for accelerators.52,53 HTS materials, tapes, and wires are developing rapidly, driven by the fusion energy industry; progress in this area could help adapt HTS wire development suitable for use in MRI systems enabling higher-field whole-body MRI/MRS systems and larger-bore animal systems. Advancing the technology of manufacturing methods that allow for design of large-scale magnets, and sufficient production volume, would quickly be adopted by industry for design of magnets.

Key Recommendation 2: The National Science Foundation, Department of Energy, and National Institutes of Health should develop collaborative programs to accelerate the development of high-temperature superconductor (HTS) magnet technology to support development in high-field magnetic resonance imaging, nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, fusion, and accelerator magnets. For example, a large-bore solenoid (900 mm+), high-field (14 T+) magnet demonstrator employing HTS technologies, ideally with ramp capability (5–10 T/s), should be commissioned to develop the

___________________

52 P.J. Lee and B. Strauss, 2011, 100 Years of Superconductivity, H. Rogalla, and P.H. Kes, eds., Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, https://fs.magnet.fsu.edu/~lee/superconductor-history_files/Centennial_Supplemental/11_2_Nb-Ti_from_beginnings_to_perfection-fullreferences.pdf.

53 Imperial College of London, 2024, “Professor David Larbalestier,” https://ow.ly/2NUU50Qs3j2.

foundational design method and wire technology that has potential applications across high-magnetic-field science.

Key Recommendation 11: Funding agencies supporting basic biological and medical research—such as the National Science Foundation, National Institutes of Health (NIH), and Department of Defense—whose constituencies are interested in ultrahigh-field magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), should consider a joint funding avenue for enabling the United States to implement human MRI at 14 T+, with NIH taking the lead. In addition to the 14 T+ funded by the Dutch consortium, Germany and China will likely follow with their own national efforts, leaving the United States behind if no action is taken.

The resulting demonstrator magnet, when complete, will serve as a valuable facility for testing HTS components of various shapes and sizes not possible today.

Key Recommendation 10: The National Institutes of Health and National Science Foundation should also launch the development of a ≥28 T small animal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) system based on combined low-temperature superconductor/high-temperature superconductor inserts which, in addition to opening new scientific frontiers, would serve as the future human-size, ultrahigh-field MRI platforms. Notice that as similar platforms that serve small rodent MRI and Fourier transform-ion cyclotron resonance experiments in both homogeneity and bore demands, this system would simultaneously push the frontiers of this important analytical technique.