The Current Status and Future Direction of High-Magnetic-Field Science and Technology in the United States (2024)

Chapter: 4 Condensed Matter Physics

4

Condensed Matter Physics

INTRODUCTION

Magnetic fields and materials have been linked since the discovery of the lodestone in the ancient world. The need for ever larger magnetic fields is propelled by discovery science, and the provisioning of the national user facilities that make them, especially at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory (NHMFL), pervades this report. The world that surrounds us is realized by our intimate interface with materials. The condensed state of matter and its field of study is responsible for the technological advancements of solid-state devices beginning with what has been called the most important discovery of the 20th century, the transistor. The discovery of superconductivity has also propelled advances in high-energy physics (HEP), metrology and precision measurements, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in biomedical imaging, and fusion research. The role of materials is deeply intertwined with humanity, the Greek legend1 defines the “ages” of mankind by key materials “Gold, Silver, Bronze, and Iron.” This description by the Greek philosopher Hesiod serves as a point of reflection of our progression as a species. In the 21st century, we are largely defined by the computational miracles formed from silicon, germanium, copper, and now carbon. The realization that artificial intelligence born from the advancement of functional electronic materials provides us with a juxtaposition of both burgeoning power and potential rapid and thorough demise.

___________________

1 N.S. Gill, 2019, “Hesiod’s Five Ages of Man,” Thought Co, https://www.thoughtco.com/the-five-ages-of-man-111776.

It is a fact that high magnetic fields provided advancement of our understanding of functional electronic materials (e.g., transistors to integrated circuits) by allowing tuning of the band structures of the basic constituents of what are now modern electronic materials. The physical connection of electrons in matter to magnetic fields is governed by the intrinsic spin of an electron which electromagnetically couples to an external magnetic field. The so-called spin-orbit coupling governs a fundamental connection of magnetic fields to the mobile electrons in materials that often provide functionality to electrical conductors as well as complex devices. There also exists a tremendous relevance of magnetic fields in nature when we look far beyond the boundaries of Earth. Extremely intense magnetic fields exist in deep space in proximity to certain types of stellar objects. These cosmological magneto dynamos (neutron stars) boast magnetic field intensities ranging from an incredible 10,000 to 100 billion Tesla (T). Magnetic field intensities of a modest 10 T have a profound impact on the ground state of most high conductivity matter in its condensed state. Like many aspects of the cosmological realm, our limitations as humans are realized while the unlimited and unquantifiable capacity of our imaginations are humbled by the possibilities of nature. Utilization of external magnetic fields in laboratory settings continues to allow us to manipulate and control the state of matter in a deeply quantifiable manner. It is because of this coupling and quantifiable manipulation that high magnetic fields are key tools in the fundamental understanding of electronically and magnetically active materials that continue to have a profound impact on human progression.

In condensed matter physics, the state of a material is often governed by an order parameter. The order parameter is a simple state relation between two thermodynamic variables; for example, the state of a material plotted as a function temperature versus magnetic field. Below a phase transition temperature governed by a specific order parameter, the system orders into a symmetry breaking state such as the superconducting state or a magnetically ordered state. As either the temperature or magnetic field is increased, the material changes its state from a superconductor to a normal metal; or in the case of a magnetically ordered material, an antiferromagnetic state to a paramagnetic state. In both examples, an applied magnetic field increases the entropy of the system and suppresses the ground state. In this way the magnetic field has an effect on the material proportional to temperature. As temperature is increased away from absolute zero, lattice vibrations increase. Eventually the lattice vibrations increase to the point that the thermal energy is greater than the ordering energy (the depth of the potential well) and the order parameter vanishes.

The applied magnetic field in the example above has a similar effect on the state of the material as does the temperature. Relative to these specific materials, the applied magnetic field is described as a thermodynamically relevant parameter. In most technologically relevant materials, the underlying quantum mechanical

ground states are only observable at temperatures significantly lower than 300 Kelvin (K). In fact, most fundamental studies of materials that reveal the quantum mechanical ground state are conducted a few degrees above absolute zero. At these low temperatures, the applied magnetic field of perhaps 10 T is a significant polarization of the electronic carriers and a macroscopic perturbation to quantum states near the Fermi energy. When condensed matter phase transitions occur at high temperatures, such as in the case of the optimally doped cuprate superconductor YBa2Cu3O7–x (YBCO) with a superconducting transition temperature at ~92 K, a very large magnetic field of order ~130 T2 is required to suppress the superconductivity at liquid helium temperatures for magnetic fields perpendicular to c-axis orientation. This example indicates that applied magnetic fields are a rather weak perturbation to thermodynamic order parameters, with a rough ratio of 1 T being equal to ~1.3 degree K of thermodynamic order. This comparison of the energy scales of temperatures and magnetic fields drives the need for ever higher magnetic fields as functional material properties are designed to operate at or above room temperature.

Another frontier of condensed matter physics, topological matter and topological physics, is also intimately tied to the availability of high magnetic fields. The first realization of novel topological states of matter was related to the discoveries of quantum Hall effects (QHE)3 and fractional quantum Hall effects (FQHE)4 in two-dimensional electron gas (2DEG) at low temperatures and high magnetic fields. In such extreme conditions, strong electronic correlations associated with the formation of flat bands result in new quantum states of abelian and nonabelian quasiparticles (known as “anyons”)5 that do not exist in natural materials and obey new statistics differing from those of standard fermions or bosons. To date, high magnetic fields continue to be a critically important platform for new discoveries of quantum and topological states in condensed matter systems. Additionally, high magnetic fields coupled with solid-state and molecular spin qubits can provide a

___________________

2 T. Sekitani, N. Miura, S. Ikeda, Y.H. Matsuda, and Y. Shiohara, 2004, “Upper Critical Field for Optimally-Doped YBa2Cu3O7−δ,” Physica B: Condensed Matter 346–347:319–324, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physb.2004.01.098.

3 K. van Klitzing, G. Dorda, and M. Pepper, 1980, “New Method for High-Accuracy Determination of the Fine-Structure Constant Based on Quantized Hall Resistance,” Physical Review Letters 45(6):494.

4 D.C. Tsui, H.L. Stormer, and A.C. Gossard, 1982, “Two-Dimensional Magnetotransport in the Extreme Quantum Limit,” Physical Review Letters 48(22):1559.

5 B.I. Halperin, 1984, “Statistics of Quasiparticles and the Hierarchy of Fractional Quantized Hall States,” Physical Review Letters 52(18):1583; D. Arovas, J.R. Schrieffer, and F. Wilczek, 1984, “Fractional Statistics and the Quantum Hall Effect,” Physical Review Letters 53(7):722; A. Khurana, 1989, “Bosons Condense and Fermions ‘Exclude’, But Anyons…?” Physics Today 42(11):17–21, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2811205; H. Bartolomei, M. Kumar, R. Bisognin, A. Marguerite, et al., 2020, “Fractional Statistics in Anyon Collisions,” Science 368(6487):173–177.

testbed for quantum information science, which is of great current technological interest and will be further elaborated in a later section of this chapter.

Generally speaking, the advances of condensed matter physics have been driven by the development of new materials (including new states of matter created by means other than chemical synthesis), new theories, and new instrumentations. In this context, high magnetic fields can play a critical role in creating new states of matter and orders in materials by breaking symmetries, lifting degeneracies, generating new energy scales, and enhancing electronic correlation. While it is impossible to forecast future breakthroughs to be enabled by high magnetic fields on the rapidly and dynamically evolving research field of condensed matter physics, great opportunities of high magnetic fields on exploring some of the recent exciting research frontiers may be expected. For instance, a new classification of magnetism, dubbed “altermagnetism,” which refers to magnetic systems with broken parity-time-reversal (PT) symmetry that exhibit staggered magnetic order both in the coordinate space and momentum space and may reveal ferromagnetic behaviors without external perturbations (type-I) or no ferromagnetic behaviors unless under external PT-symmetry preserving perturbations such as electrical current and stress (type-II and type-III),6,7,8 has stimulated much research interest owing to its richness in combining the crystallographic and spin alternations as well as its potential for spintronic applications that can leverage complementary advantages of both ferromagnetism and antiferromagnetism. The interplay of high magnetic fields and the spin and crystallographic configurations of altermagnets is expected to yield interesting new phenomena, which has yet to be explored in depth. On the other hand, there has been a plethora of research activities and exciting new findings in two-dimensional (2D) quantum materials (including 2D van der Waals materials and their heterostructures and Morie superlattices) that have benefited from high magnetic fields,9 where electronic interactions modulated by magnetic fields have led to many interesting quantum and topological states that are also promising for spintronic and optoelectronic applications.

___________________

6 I. Mazin and The PRX Editors, 2022, “Editorial: Altermagnetism—A New Punch Line of Fundamental Magnetism,” Physical Review X 12(4):040002, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevX.12.040002.

7 L. Šmejkal, J. Sinova, and T. Jungwirth, 2022, “Emerging Research Landscape of Altermagnetism,” Physical Review X 12(4):040501, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevX.12.040501.

8 S.-W. Cheong and F.-T. Huang, 2024, “Altermagnetism with Non Collinear Spins,” npj Quantum Materials 9(1):13, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-024-00626-6.

9 Q.H. Wang, A. Bedoya-Pinto, M. Blei, et al., 2022, “The Magnetic Genome of Two-Dimensional van der Waals Materials,” ACS Nano 16(5):6960–7079; P. Liu, Y. Zhang, K. Li, Y. Li, and Y. Pu, 2023, “Recent Advances in 2D van der Waals Magnets: Detection, Modulation, and Applications,” Iscience 26:107584; S. Wang, J. Song, M. Sun, and S. Cao, 2023, “Emerging Characteristics and Properties of Moiré Materials,” Nanomaterials 13(21):2881.

Finding: High magnetic fields are an important tool and platform for condensed matter physics research, providing insights into properties of materials and creating novel states of matter that cannot be obtained in any other way and serving as a testbed for quantum information technologies.

MEASUREMENTS IN DIRECT CURRENT AND PULSED MAGNETIC FIELD

Condensed matter physics research in high magnetic fields is carried out under either DC field or pulsed field environment. A wide variety of experimental techniques have been employed to investigate different properties of materials (e.g., electronic, magnetic, structural, thermodynamic, optical, transport, superconducting, and topological). Additionally, solid-state and molecular spin qubits in high magnetic fields can provide a platform for the exploration of quantum information science. Here the committee describes some of the representative high-magnetic-field measurement principles and examples of recent research developments to highlight the importance of high magnetic fields to the advances of condensed matter physics.

Magnetic Quantum Oscillations in Matter

The measurement of the phenomena of “magneto quantum oscillations” (MQOs) in matter under high magnetic fields is an extremely powerful method for determining fundamental quantum mechanical underpinnings of materials that can enable complete design of electronic materials from first principles. This bulk phenomenon was first discovered in 1930 by De Haas and Van Alphen.10 In 1984, David Shoenberg published a comprehensive text11 in which he explains not only the origins of the quantization of bulk observable signals such as magnetic susceptibility but also the practical implementation of the measurement technique in bulk matter. The manifestation of MQO in materials provides scientists a direct measurement of extremal cross-sectional area of the Fermi surface and as the magnetic field intensity is increased the MQO effects exponentially grow in amplitude. Additionally, the MQO phenomena can be used to map out in three dimensions the “shape” (in energy space) of the electronic structure (Fermi surface) which is of particular importance in low dimensional metals in which the inter-layer coupling can be better understood and tuned to a desirable behavior. This powerful method

___________________

10 W.J. De Haas and P.M. Van Alphen, 1930, “The Dependence of the Susceptibility of Diamagnetic Metals Upon the Field,” Proceedings of the Netherlands Royal Academy of Sciences.

11 D. Shoenberg, 1984, Magnetic Oscillations in Metals. Cambridge Monographs on Physics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

has been a key in understanding interlayer coupling and the very nature of the metallic state of superconducting metals and allowed physicists and engineers in the 1960s through the 1980s to tune bandgaps of semiconductors via related methods like utilization of cyclotron resonance.

High magnetic fields are essential in being able to reveal the basic properties of the electronic structure of electronically functional matter. The search for MQO response in matter itself is often a driving force in the quest for higher-applied magnetic fields as well as a driver for an increase in solenoid bore and pulse duration in pulsed magnets or low noise and low vibration in DC (or steady state) research magnets. Precision techniques are needed to observe these remarkable phenomena. The highest-field techniques (such as the Single-Turn method or Electromagnetic Implosion method) have not yet been able to consistently provide the research platform for MQO measurement. That fact is an indication that more work is needed in the development of instrumentation and sample preparation methods to fully exploit the ultrahigh-magnetic field generation systems.

Pulsed Field

The capabilities of pulsed fields to achieve ultrahigh-magnetic fields over a limited time window and ultrahigh-magnetic field sweep rates (dB/dt) and gradients (dB/dx) have been instrumental for scientific discoveries of novel quantum phases and transient states in condensed matter physics. Here the committee showcases four recent exemplifying highlights in condensed matter physics research that were enabled by various available measurement techniques at pulsed field facilities.

Pulsed Field Example 1

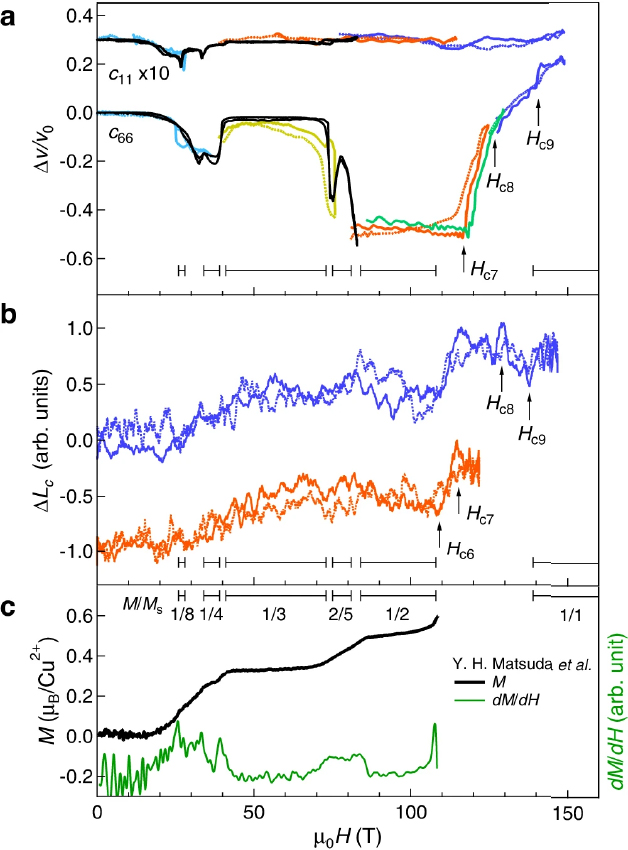

A frustrated quantum magnet system, the Shastry-Sutherland compound SrCu2(BO3)2,12 is shown to reveal several spin-supersolid phases in ultrahigh fields above one-half of the saturation magnetic field of 140 T to 150 T by using ultrasound and magnetostriction measurement techniques. The research team utilized an ultrahigh-field single turn system to reveal quantum phenomena of SrCu2(BO3)2 with H//c axis.

___________________

12 B.S. Shastry and B. Sutherland, 1981, “Exact Ground State of a Quantum Mechanical Anti-ferromagnet,” Physica B+C 108(1–3):1069–1070; S. Miyahara and K. Ueda, 1999, “Exact Dimer Ground State of the Two Dimensional Heisenberg Spin System SrCu2(BO3)2,” Physical Review Letters 82(18):3701.

In this example,13 the research team successfully revealed the physical phenomena in this novel material by making use of a well-established magnetic field generation system (a single turn magnet) and utilization of the magnetic susceptibility method and sound speed transmission at low cryogenic temperatures to measure the quantum magnetism that develops in this material, as shown in Figure 4-1. This example is an excellent demonstration of application of state-of the-art magnets and diagnostics to reveal a very subtle physical phenomenon. This effort was successful in part owing to the low electrical conductivity of the material under study, as high conductivity materials have the significant additional challenge of deleterious eddy current heating owing to the high degree of dB/dt magnetic field change in time and dB/dx magnetic field gradient associated with the single turn magnet technique.

Pulsed Field Example 2

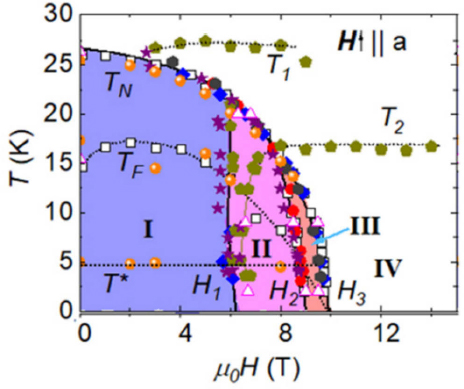

Electronic and magnetic phase diagrams of the Kitaev quantum spin liquid candidate Na2Co2TeO6 mapped out by pulsed magnetic fields.14

The Kitaev quantum spin liquids (KQSLs) host nonAbelian anyonic excitations in applied magnetic fields, which are of particular interest to the quantum computation community.15 In this example, the research team utilized pulsed fields to perform the magnetocaloric measurements of the Kitaev quantum spin liquid candidate Na2Co2TeO6 to map out the temperature (T) versus magnetic field (H) phase diagram shown in Figure 4-2 because the high dB/dt (~10,000 T/s) increases the sensitivity for detecting the spin phase transitions.

Pulsed Field Example 3

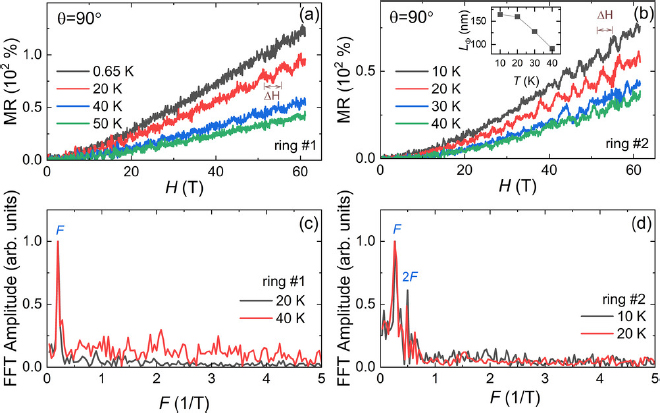

Tuning topological quantum properties of TaSe3 with strain in pulsed magnetic fields. Quantum interference explained by the Altshuler-Aronov-Spivak effect in devices measured in 60 Tesla pulsed magnetic fields.16

___________________

13 T. Nomura, P. Corboz, A. Miyata, et al., 2023, “Unveiling New Quantum Phases in the Shastry-Sutherland Compound SrCu2(BO3)2 Up to the Saturation Magnetic Field,” Nature Communications 14(1):3769, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-39502-5.

14 S. Zhang, S. Lee, A.J. Woods, et al., 2023, “Electronic and Magnetic Phase Diagrams of the Kitaev Quantum Spin Liquid Candidate Na2Co2TeO6,” Physical Review B 108(6):064421.

15 Kitaev, A., 2006, “Anyons in an Exactly Solved Model and Beyond,” Annals of Physics 321(1):2–111, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aop.2005.10.005

16 J. Xing, J. Blawat, S. Speer, et al., 2023, “Tuning Topological Properties of TaSe3 Using Strain,” https://nationalmaglab.org/media/ojdn2zn2/june2023-pulsed-field-facility-topological-properties.pdf.

SOURCE: T. Nomura, P. Corboz, A. Miyata, S. Zherlitsyn, Y. Ishii, Y. Kohama, Y.H. Matsuda, et al., 2023, “Unveiling New Quantum Phases in the Shastry-Sutherland Compound SrCu2(BO3)2 up to the Saturation Magnetic Field,” Nature Communications 14(1):3769, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467023-39502-5. CC BY 4.0.

NOTE: Here the committee notes that the magnetocaloric effect (sample temperature change versus magnetic field) measurement was performed in pulsed magnetic fields, where a nearly adiabatic condition was realized, owing to the ultrafast field sweeping rate of ~10,000 T/s.

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from S. Zhang, S. Lee, A.J. Woods, W.K. Peria, et al., 2023, “Electronic and Magnetic Phase Diagrams of the Kitaev Quantum Spin Liquid Candidate Na2Co2TeO6,” Physical Review B 108(6):064421, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.108.064421. Copyright 2023 by the American Physical Society.

First-principles calculations suggest the nontrivial topological phases caused by the distorted type-II chain can exist in quasi-one-dimensional TaSe3.17,18 Ribbon-shaped TaSe3 single crystals can be easily bended along its b-axis, forming rings. In this example, the research team investigated the magnetoresistance (MR) of TaSe3 up to 60 T pulsed fields in both unbended (ribbon shape) and ring-shaped (bended ribbon) samples. The study reveals quantum oscillations as a function of the magnetic field when the magnetic field is applied parallel to the TaSe3 rings, as exemplified in Figure 4-3. The authors attributed this phenomenon to either the Altshuler–Aronov–Spivak effect or the inversion of the lowest Landau level beyond the quantum limit. These results are related to strain-induced electronic structure

___________________

17 S. Nie, L. Xing, R. Jin, W. Xie, Z. Wang, and F.B. Prinz, 2018, “Topological Phases in the TaSe3 Compound,” Physical Review B 98(12):125143, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.98.125143.

18 A. Bansil, H. Lin, and T. Das, 2016, “Colloquium: Topological Band Theory,” Reviews of Modern Physics 88(2):021004, https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.88.021004.

SOURCE: J. Xing, J. Blawat, S. Speer, A.I.U. Saleheen, J. Singleton, and R. Jin, 2022, “Manipulation of the Magnetoresistance by Strain in Topological TaSe3,” Advanced Quantum Technologies 5(12):2200094, https://doi.org/10.1002/qute.202200094, © 2022 The Authors. Advanced Quantum Technologies published by Wiley-VCH GmbH.

change in TaSe3, suggesting strain being an effective way to tune physical properties of low-dimensional materials.19

Pulsed Field Example 4

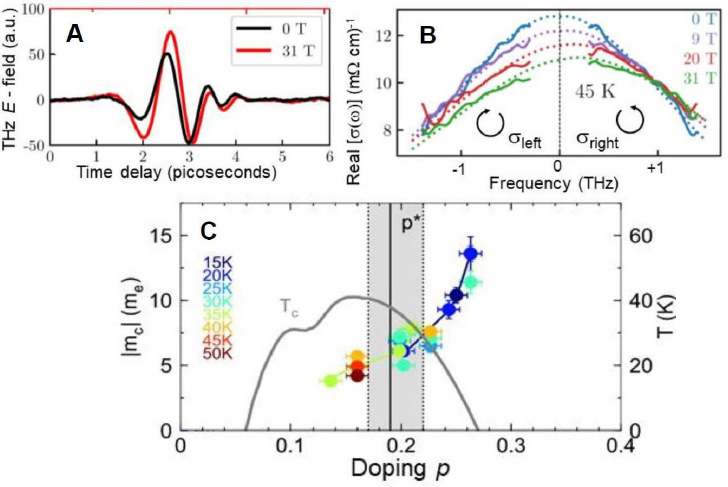

Direct measurement of cyclotron resonance in high-temperature superconductors by ultrafast THz spectroscopy in pulsed magnetic fields.20 A pulsed field capability of free space optics, THz spectroscopy has been applied to a high-temperature superconducting family of La2–xSrxCuO4 (LSCO) thin films to determine the carrier effective mass for a series of dopant levels (p) from slightly underdoped to highly overdoped (p = 0.13 ~ 0.26).

___________________

19 J. Xing, J. Blawat, S. Speer, A.I.U. Saleheen, J. Singleton, and R. Jin, 2022, “Manipulation of the Magnetoresistance by Strain in Topological TaSe3,” Advanced Quantum Technologies 5(12):2200094, https://doi.org/10.1002/qute.202200094.

20 K. Post, A. Legros, P. Chauhan, et al., 2023, “Direct Measurement of Cyclotron Resonance in a High-Temperature Superconductor: Ultrafast THz Spectroscopy in Pulsed Magnetic Fields,” https://nationalmaglab.org/media/ebzng4tl/february2023-pulsed-field-direct-measurement-ccyclotron-resonance.pdf.

SOURCE: Reprinted figure with permission from K.W. Post, A. Legros, D.G. Rickel, et al., 2021, “Observation of Cyclotron Resonance and Measurement of the Hole Mass in Optimally Doped La2−xSrxCuO4,” Physical Review B 103(13):134515, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.103.134515. Copyright 2021 by the American Physical Society.

Cyclotron resonance provides a direct measure of the carrier effective mass (mc) via the relation mc = Be/ωc, where ωc denotes the cyclotron frequency of the charge carriers, and the magnitude of mc in materials is well established to be related to the electron–electron and electron–lattice interactions. In this example, the research team performed direct measurements of cyclotron resonance on a family of high-temperature superconductors, La2−xSrxCuO4 (LSCO) thin films. Owing to the large masses and scattering rates in high-temperature superconductors, very high B and broad (THz) bandwidth is needed. The research team at the NHMFL Pulsed Field Facility in Los Alamos, New Mexico, coupled a time-domain THz spectrometer to a purpose-built 31 Tesla pulsed magnet to measure the broadband THz optical conductivity of LSCO thin films with hole doping levels (p) ranging from slightly underdoped to highly overdoped (p = 0.13 ~ 0.26), and found that the effective masses of the hole carriers ranged from 4 to 14 times of free electron mass, as shown in Figure 4-4.21 The simplicity of a relatively small pulsed-field magnet coupled with free-space optics exemplifies the potential to democratize intense magnetic fields with a relatively inexpensive system such as the system employed in this example and described in.22

Finding: The ultrahigh magnitude and sweeping rate of magnetic fields provided by pulsed field magnets enable unique scientific opportunities for condensed matter physics research.

Finding: Currently, pulsed fields above 100 T have mostly been provided by single-turn magnets. There is scientific need for developing long-pulse magnets with maximum fields beyond 100 T.

DC Field

In comparison to pulsed field measurements, DC fields offer long-term stability in the magnetic field strength for experiments that require long measurement time, which is particularly important for studies under extreme conditions such as ultralow temperature and high-pressure measurements, and for spatially resolved imaging and spectroscopic studies using scanning probe microscopy. Therefore, most condensed matter physics research in high magnetic fields has been conducted in DC fields, including the landmark discoveries of QHE and FQHE discussed

___________________

21 A. Legros, K.W. Post, P. Chauhan, et al., 2022, “Evolution of the Cyclotron Mass with Doping in La2−xSrxCuO4,” Physical Review B 106(19):195110, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.106.195110.

22 K.W. Post, A. Legros, D.G. Rickel, et al., 2021, “Observation of Cyclotron Resonance and Measurement of the Hole Mass in Optimally Doped La2−xSrxCuO4,” Physical Review B 103(13):134515, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.103.134515.

earlier in this chapter. Here the committee shows two representative examples of the enabling power of high DC fields together with unique instrumentations for advancing scientific understanding of frontier research in condensed matter physics, which also demonstrate the continuing need for higher DC fields, new instrumentation, and incorporation of high magnetic fields with major facilities like neutron scattering and synchrotron accelerator light sources.

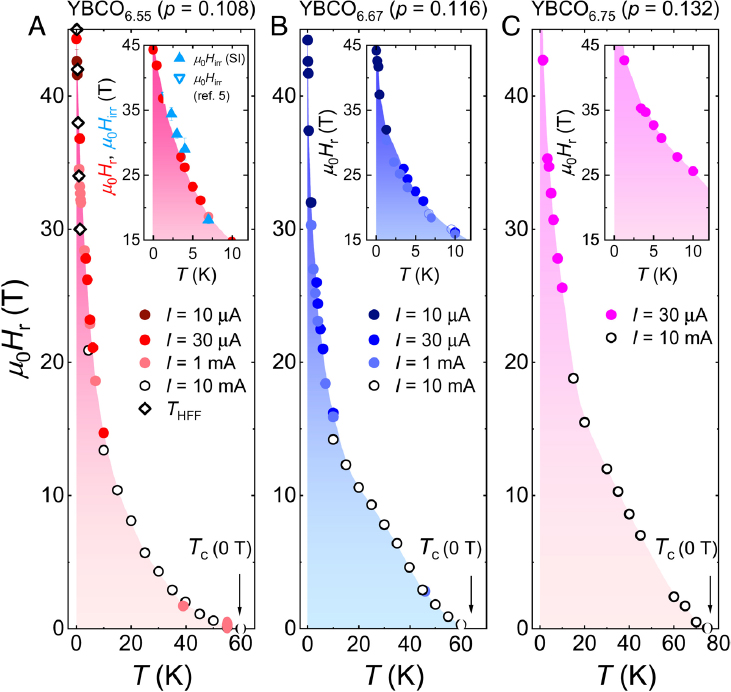

The first example is a recent study of ultrapure single crystals of underdoped high-temperature superconductors YBa2Cu3O6+x that employed the extreme conditions of ultrahigh DC magnetic fields (up to 45 T) and ultralow temperatures (down to 40 mK) at the NHMFL DC field facilities. As shown in Figure 4-5 and Figure 4-6, the research team discovered an unconventional quantum vortex matter ground state in these underdoped superconductors under the extreme conditions. The quantum vortex matter ground state was characterized by vanishing electrical resistivity, magnetic hysteresis, nonohmic electrical transport characteristics, and magnetic quantum oscillations.23 This unusual finding, made possible only by the extreme high field and low temperature conditions, called for theoretical modeling of the novel pseudogap ground state to explain the quantum oscillations hosted by the bulk quantum vortex matter state in the presence of a large superconducting gap.24 A feasible scenario that may account for the novel quantum vortex matter is the coexistence of finite gapless excitations, such as the pair density wave (PDW),25,26 with a large superconducting gap, which is also consistent with direct observation of density waves using spatially resolved scanning tunneling spectroscopy (STS) in the vortex state of hole-doped cuprate superconductors,27,28 although these earlier STS studies were only carried out at lower magnetic fields (<10 T) owing to the absence of scanning probe capabilities in high DC field facilities at

___________________

23 Y.T. Hsu, M. Hartstein, A.J. Davies, et al., 2021, “Unconventional Quantum Vortex Matter State Hosts Quantum Oscillations in the Underdoped High-Temperature Cuprate Superconductors,” Proceedings of the Natitonal Academy of Sciences 118(7), https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2021216118.

24 P.A. Lee, 2014, “Amperean Pairing and the Pseudogap Phase of Cuprate Superconductors,” Physical Review X 4(3):031017, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevX.4.031017.

25 Z. Dai, Y.-H. Zhang, T. Senthil, and P.A. Lee, 2018, “Pair-Density Waves, Charge-Density Waves, and Vortices in High-Tc Cuprates,” Physical Review B 97(17):174511, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.97.174511.

26 Z. Dai, T. Senthil, and P.A. Lee, 2020, “Modeling the Pseudogap Metallic State in Cuprates: Quantum Disordered Pair Density Wave,” Physical Review B 101(6):064502, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.101.064502.

27 J.E. Hoffman, E.W. Hudson, K.M. Lang, et al., 2002, “A Four Unit Cell Periodic Pattern of Quasi-Particle States Surrounding Vortex Cores in Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+d,” Science 295(5554):466–469, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1066974.

28 A.D. Beyer, M.S. Grinolds, M.L. Teague, S. Tajima, and N.-C. Yeh, 2009, “Scanning Tunneling Spectroscopic Evidence for Magnetic-Field–Induced Microscopic Orders in the High-Tc Superconductor YBa2Cu3O7−δ,” Europhysics Letters 87(3):37005, https://doi.org/10.1209/0295-5075/87/37005.

SOURCE: Y.-T. Hsu, M. Hartstein, A.J. Davies, et al., 2021, “Unconventional Quantum Vortex Matter State Hosts Quantum Oscillations in the Underdoped High-Temperature Cuprate Superconductors,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118(7):e2021216118, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2021216118. Copyright 2021 National Academy of Sciences, U.S.A.

NHMFL. Moreover, this investigation of the novel quantum vortex matter could only be carried out in sufficiently underdoped YBa2Cu3O6+x superconductors because of the limitation of available DC field (45 T), whereas a complete understanding of the coexistence of a novel pseudogap ground state (e.g., PDW) and superconductivity in the cuprates requires comprehensive studies from underdoped to optimally doped and overdoped materials, which necessitate much higher DC fields beyond the currently available maximum DC field of 45 T in the case of YBa2Cu3O6+x superconductors near the optimal doping level.

SOURCE: Y.-T. Hsu, M. Hartstein, A.J. Davies, et al., 2021, “Unconventional Quantum Vortex Matter State Hosts Quantum Oscillations in the Underdoped High-Temperature Cuprate Superconductors,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118(7):e2021216118, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2021216118. Copyright 2021 National Academy of Sciences, U.S.A.

Additional limitations on pulsed field techniques further drive the need for high steady-state (DC) research magnetic fields. The practical limitation of low temperature apparatus—such as dilution refrigerators, specific heat probes, surface scanning probes, as well as some spectroscopy apparatus—are very difficult to even impractical to implement in pulsed magnets. There are examples of most of the above being successfully utilized in long pulse duration magnets where a very high degree of technical expertise is required and the pulsed field methods are successful in a subset of materials with favorable properties. Generally speaking, for most users the experiments in DC fields are significantly more straightforward, and often an extension of methods and apparatus being utilized at their home institution’s

superconducting magnets, than those in pulsed fields. Hence, users can bring a well-developed method and sample set to a national facility and simply extend the magnetic measurement range. Such an approach then reserves the pulsed magnetic field efforts to the subset of material exploration first established in lower DC fields.

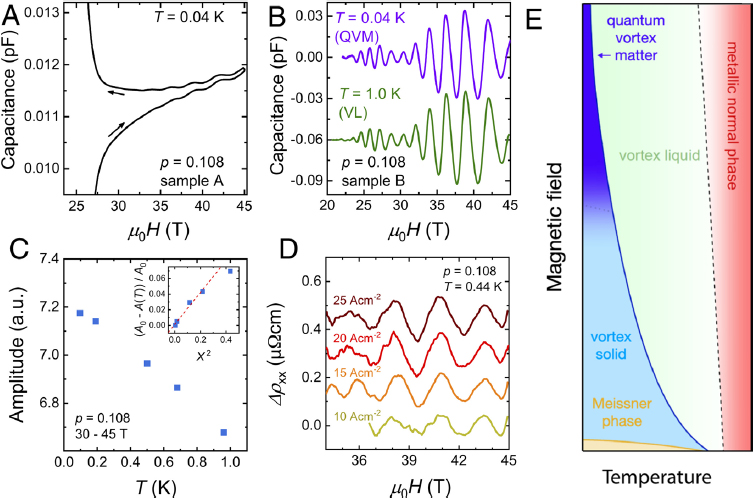

The second example involves recent high DC field (up to 25.9 T) inelastic neutron scattering (INS) studies of the frustrated quantum magnet system SrCu2(BO3)2 at 200 mK.29 The experiments were carried out at unique facilities in Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin (HZB) with capabilities currently not available in the United States. The experimental results were further compared with quantitatively accurate spectral functions calculated by advanced numerical methods based on matrix-product states (MPS), which provide compelling evidence for field-induced Bose Einstein condensation (BEC) of bound-state magnons and the formation of a spin nematic state in SrCu2(BO3)2.

As illustrated previously under Pulsed Field Example 1, a model system of the Shastry-Sutherland lattice, SrCu2(BO3)2, reveals a sequence of magnetization plateau phases at fractional magnetization under an external magnetic field, which is a paradigm for studying ideal frustration in a two-dimensional (2D) spin system. The SrCu2(BO3)2 system consists of S = 1/2 dimer units of copper spins arranged orthogonally on a square lattice, and its properties are governed by the ratio between the intra-dimer interaction, J, and inter-dimer one, J'. For instance, in the case of (J'/J) <0.675, the ground state of the system is an exact dimer-product singlet state, and the ideally frustrated geometry leads to many unconventional effects, including nearly dispersionless one-magnonexcitations (i.e., triplons) and very strongly bound multi-triplon states. In analogy with charge-density-wave (CDW) order in electronic systems, the magnetization plateau phases in SrCu2(BO3)2 can be viewed as bosonic CDW phases of magnetic entities. Among them, the theoretically predicted spin superstructure on the lowest 1/8 plateau is a crystal of S = 2 two-triplon bound states, as opposed to a crystal of unbound S = 1 triplons.30 However, the exact magnetic structures of this phase could not be verified until recent INS measurements carried out at HZB. As summarized in Figure 4-7, the unique experimental capabilities of the facilities at HZB were able to resolve very small energy excitations at 200 mK and had sufficient momentum resolution in finite DC field up to 25.9 T. Combining these experimental results with advanced MPS numerical calculations, the research led to convincing manifestation of BEC of S = 2 bound triplons. Considering the interesting magnetic phases associated with various fractional magnetizations at higher magnetic fields (anomalies at 27

___________________

29 E. Fogh, M. Nayak, O. Prokhnenko, et al., 2024, “Field-Induced Bound-State Condensation and Spin-Nematic Phase in SrCu2(BO3)2 Revealed by Neutron Scattering Up to 25.9 T,” Nature Communications 15(1):442, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44115-z.

30 P. Corboz and F. Mila, 2014, “Crystals of Bound States in the Magnetization Plateaus of the Shastry-Sutherland Model,” Physical Review Letters 112(14):147203.

T, 33 T, 40 T, and 74 T that correspond to the onsets of the 1/8, 1/4, 1/3, and 2/5 plateau phases) in this system, and more generally in other frustrated quantum magnet systems, it is clear from this example that a higher DC field equipped with experimental capabilities that can resolve spin configurations in both momentum and spatial dimensions (e.g., neutron scattering, NMR, and Raman spectroscopy) will be critically important to advance the frontiers of research in condensed matter physics. Unfortunately, the United States is currently behind Europe, Japan, and China in some of these critical developments.

Beyond equilibrium phases of matter, an exciting research frontier associated with light-induced dynamics and control of correlated quantum systems has led to some striking findings in optically driven quantum solids,31 including light-induced superconductivity;32,33 novel Floquet-engineered topological phases;34,35,36 and light-induced anomalous Hall effect in graphene.37 New research opportunities for investigating optically driven nonequilibrium phases in condensed matter systems may be enabled by combining ultrafast optics and electrical transport measurement techniques with DC fields, which are promising for exciting scientific discoveries.

Finding: The maximum DC field of 45 T currently available at NHMFL is not sufficient for certain frontier research topics in condensed matter physics. The existing instrumentation capabilities for DC fields are also limited for comparative studies of the same material in high DC fields using different experimental probes.

Conclusion: Maximum DC fields beyond 45 T are required for frontier condensed matter physics research. Additionally, efforts in high-field instrumentation development are as important as increasing the maximum available field for advancing the scientific outcome in condensed matter physics research.

___________________

31 D.N. Basov, R.D. Averitt, and D. Hsieh, 2017, “Towards Properties on Demand in Quantum Materials,” Nature Materials 16(11):1077–1088.

32 D. Fausti, R.I. Tobey, N. Dean, et al., 2011, “Light-Induced Superconductivity in a Stripe-Ordered Cuprate,” Science 331(6014):189–191.

33 M. Mitrano, A. Cantaluppi, D. Nicoletti, et al., 2016, “Possible Light-Induced Superconductivity in K3C60 at High Temperature,” Nature 530(7591):461–464.

34 N.H. Lindner, G. Refael, and V. Galitski, 2011, “Floquet Topological Insulator in Semiconductor Quantum Wells,” Nature Physics 7(6):490–495.

35 E.J. Sie, J.W. McIver, Y.H. Lee, L. Fu, J. Kong, and N. Gedik, 2015, “Valley-Selective Optical Stark Effect in Monolayer WS2,” Nature Materials 14(3):290–294, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat4156.

36 M. Bukov, L. D’Alessio, and A. Polkovnikov, 2015, “Universal High-Frequency Behavior of Periodically Driven Systems: From Dynamical Stabilization to Floquet Engineering,” Advances in Physics 64(2):139–226.

37 J.W. McIver, B. Schulte, F.-U. Stein, et al., 2020, “Light-Induced Anomalous Hall Effect in Graphene,” Nature Physics 16(1):38–41.

SOURCE: E. Fogh, M. Nayak, O. Prokhnenko, et al., 2024, “Field-Induced Bound-State Condensation and Spin-Nematic Phase in SrCu2(BO3)2 Revealed by Neutron Scattering Up to 25.9 T,” Nature Communications 15(1):442, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44115-z. CC BY.

QUANTUM INFORMATION SCIENCE

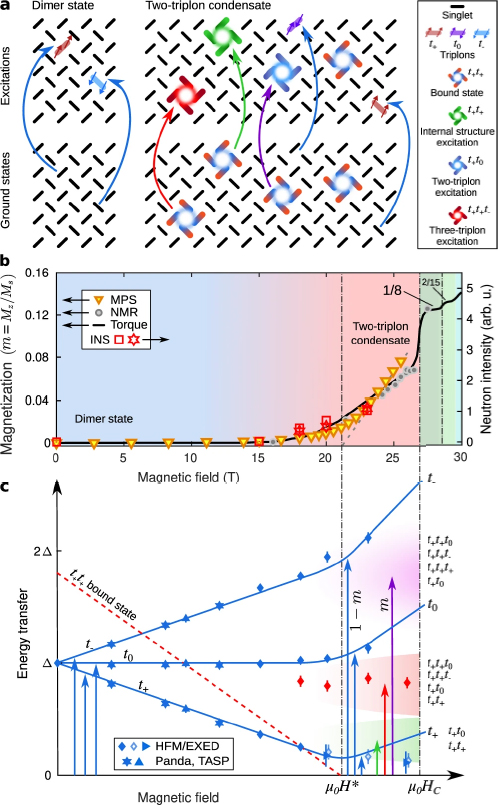

Spin-based qubits and quantum gates in both solid-state systems (such as nitrogen-vacancy [NV] centers in diamond and color centers in semiconductors) and synthetic molecular qubits38 are valuable testbeds for the development of quantum information science (QIS), including in the areas of quantum computation, quantum sensing, and quantum communications and networking. These systems are typically studied in magnetic fields by means of static, time-resolved, and pulsed electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) techniques. Generally, higher magnetic fields enable better spectral resolution and orientation selectivity as well as higher-frequency spectral measurements of spin qubits (see Figure 4-8A), which promotes the detection frequency range from radio frequency (RF) or microwave to infrared (IR) frequencies so that laser technologies can be incorporated. Higher-frequency measurements together with a low-temperature environment have the advantage of better spatial resolution and sensitivities for the detection and manipulation of more coherent spin qubits, which may be further coupled with spatially resolved scanning probe microscopy (SPM) to achieve local manipulation and measurements of spin qubits. In this context, improvements in the measurement and control techniques in spectroscopy and microscopy are equally important to increasing the magnetic fields in advancing the field of QIS based on spin qubits. Optical techniques—such as quantum lights of entangled photons and squeezed states of light (see Figure 4-8B, C), time-resolved pulsed signals, nonlinear spectroscopy, and cavity-enhanced and modified light-matter interaction—are important instrumentation developments to fully realize the potential of using the spin-based qubit systems as simulators for advancing QIS, particularly for quantum sensing, quantum memories, and quantum repeaters in quantum communications. For instance, entangled photons generated by spontaneous parametric down conversion (SPDC) can enable the use of visible light “pump” to detect IR or THz signals.39 Additionally, entangled photons allow for measurements of one photon using another wavelength or imaging an object without spatially detecting the photons hitting the target. Such “ghost” measurement techniques rely on the quantum correlations between the two photons in an entangled pair so that the property of one photon can be determined by its

___________________

38 For comprehensive studies of the status of molecular qubits in quantum information science, see National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), 2023, Advancing Chemistry and Quantum Information Science: An Assessment of Research Opportunities at the Interface of Chemistry and Quantum Information Science in the United States, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, https://doi.org/10.17226/26850.

39 S. Mukamel, M. Freyberger, W. Schleich, et al., 2020, “Roadmap on Quantum Light Spectroscopy,” Journal of Physics B: Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics 53(7):072002, https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6455/ab69a8.

significantly higher sensitivity. (b) Two photons with entangled polarization states can be generated through spontaneous parametric down conversion. Here, a nonlinear χ(2) crystal is exposed to a pump beam. The example depicted in this schematic diagram specifically employs a type-2 SPDC scenario, in which there is an angle between the vertically (V)-polarized output idler (i) beam (|V〉i) and the horizontally (H)-polarized signal (s) beam (|H〉s), both emitted in a cone-shape distribution, thus forming a double-cone emission pattern. At the intersection of the cones, photons have an entangled polarization state, |H〉i |V〉s + e iφ |V〉i |H〉s, where φ is the phase difference between the entangled photons. (c) While a coherent photon mode has the same uncertainty in the position and momentum, a squeezed photon has an asymmetric distribution in the position-momentum uncertainty. Squeezed photons can be generated through parametric amplification of a coherent photon source. Specifically, a coherent photon is placed into a resonator with a second order nonlinear χ (2) crystal, which is mathematically equivalent of performing a squeeze operation, S = exp [r (a†2 – a2)/2], which is a Bogoliubov transformation on a coherent state S |n〉. In the specific example above, the momentum-component is squeezed by 3 dB, such that there is half the momentum uncertainty. In general, any arbitrary conjugate quadrature component can be squeezed, not just limited to momentum-position.

SOURCE: Courtesy of Nai-Chang Yeh.

entangled counterpart, which can substantially compensate for the limitation of available magnetic fields or experimental setups.40 Recently, photoelectronic quantum gate operations and readouts of nuclear spins in NV centers of diamond have been demonstrated in a microelectronic quantum device,41 which allows for the spatial resolution of a readout area only limited by the inter-electrode distance defined by lithography rather than by the diffraction limit in typical optical techniques based on classical light. These examples clearly highlight the necessity of combining advanced instrumentation developments with high magnetic fields for the research of QIS.

Finding: There is a strong user community accessing both the steady and pulsed field facilities, which are being used to capacity. There is a strong need for advanced instrumentation developments associated with all high-field facilities to optimize the scientific and technological output from these facilities.

___________________

40 NASEM, 2023, Advancing Chemistry and Quantum Information Science: An Assessment of Research Opportunities at the Interface of Chemistry and Quantum Information Science in the United States, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, https://doi.org/10.17226/26850, p. 83.

41 M. Gulka, D. Wirtitsch, V. Ivády, et al., 2021, “Room-Temperature Control and Electrical Readout of Individual Nitrogen-Vacancy Nuclear Spins,” Nature Communications 12(1):4421, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24494-x.

CURRENT STATUS OF AVAILABLE MAGNETIC FIELDS WORLDWIDE

Multiple attempts to reach above 100 T in the field have been made by the Pulsed Field programs in Dresden, Germany, and in Wuhan, China. As of this writing (2024) all efforts to surpass 100 T (in nondestructive multi-pulse magnets) have failed at fields below 100 T (except in the one case at NHMFL, Los Alamos, New Mexico, March 2012). The NHMFL effort was somewhat distinct from the other efforts in that the energy density of the magnet system was significantly lower, hence the complex stress orientations on the wire and reinforcement are generally lower in the NHMFL effort when compared to the German and Chinese efforts (for nondestructive multi-pulse magnets). The total energy consumed in the NHMFL version of the 100 T magnet is significantly higher than in the other attempts with the same peak field target. The distinction of “nondestructive multi-pulse magnet” is very important with regard to the ease of use and implementation toward high-sensitivity condensed matter physics research. There is a significant technical diagnostic capability available to scientists (high-magnetic-field users) already in use for these nondestructive pulsed magnets. Currently the greatest distinction is an available bore diameter of at least ~10 mm, a dB/dt of ~200–1000 T/s and a field homogeneity (dB/dx) of at least ~0.1 T/mm. Single Turn magnets routinely have similar bore diameters and exceed 100 T but have a dB/dt of ~10^8 T/s and dB/dx ~1–10 T/mm making them much more limited in implementation of available condensed matter diagnostic methods.

Finding: The highest accessible (nondestructive) pulsed field has exceeded 100 T only once and the steady field at 45 T; no progress over at least a decade worldwide.

The Institute of Solid State Physics (ISSP) in Kashiwa, Japan, leads the world in ultrahigh-magnetic-field capability as applied to condensed matter physics. The ISSP has pioneered many ultrahigh-magnetic-field measurement methods as well. The most utilized research diagnostic continues to be optical spectroscopy methods for these extreme magnetic fields owing to the inherent decoupling of the measurement from the voltage inducing transient fields. At ISSP, the pursuit of magnetotransport measurement methods is still very active. The only (previously user accessible) single-turn magnet system located within the United States is at the NHMFL Pulsed Field Facility (PFF) in Los Alamos, New Mexico. The NHMFL system was fully funded by Los Alamos National Laboratory with stewardship left in the hands of NHMFL. NHMFL and NSF have failed to provide the leadership and funding streams to hire personnel to develop diagnostics to make the system a resource for users. Currently (as of January 2024) the United States has no means

to provide magnetic fields for condensed matter research in magnetic fields exceeding approximately 80 T. The 100 T nondestructive magnet system has been offline in the United States since 2019, and NSF and NHMFL have chosen to not utilize the Single Turn Magnet System that was funded by internal sources of Los Alamos National Laboratory. Recently NHMFL has decided to not support further Single Turn system development. This capability is in jeopardy of being lost to qualified users. In the meantime, significant progress has been demonstrated by other high-field facilities around the world to further develop techniques and hence bear the scientific fruit.42

Finding: Progress in ultrahigh fields using single turn magnets has been largely in Japan.

Conclusion: More investment in single-turn measurement technique development and personnel is needed to overcome this roadblock in the United States.

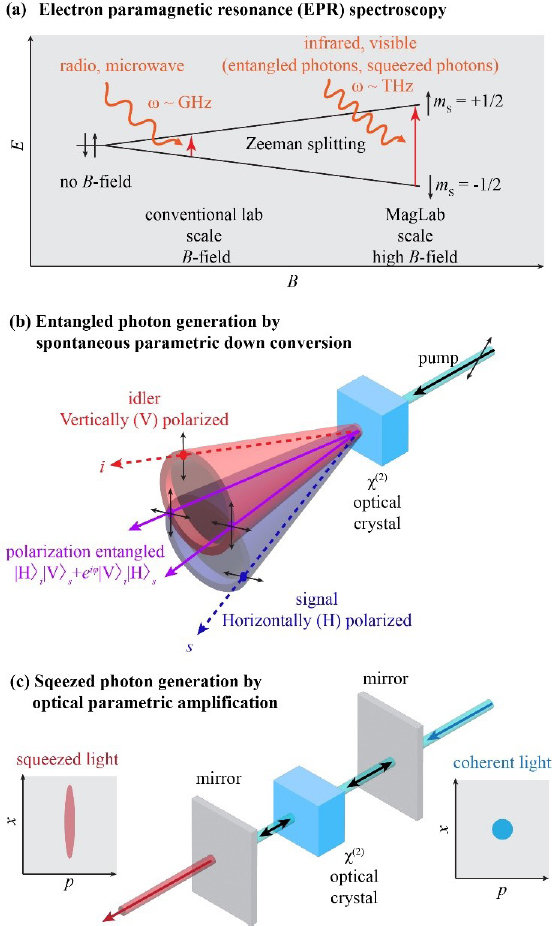

INSTRUMENTATION DEVELOPMENT FOR HIGH-FIELD MEASUREMENTS

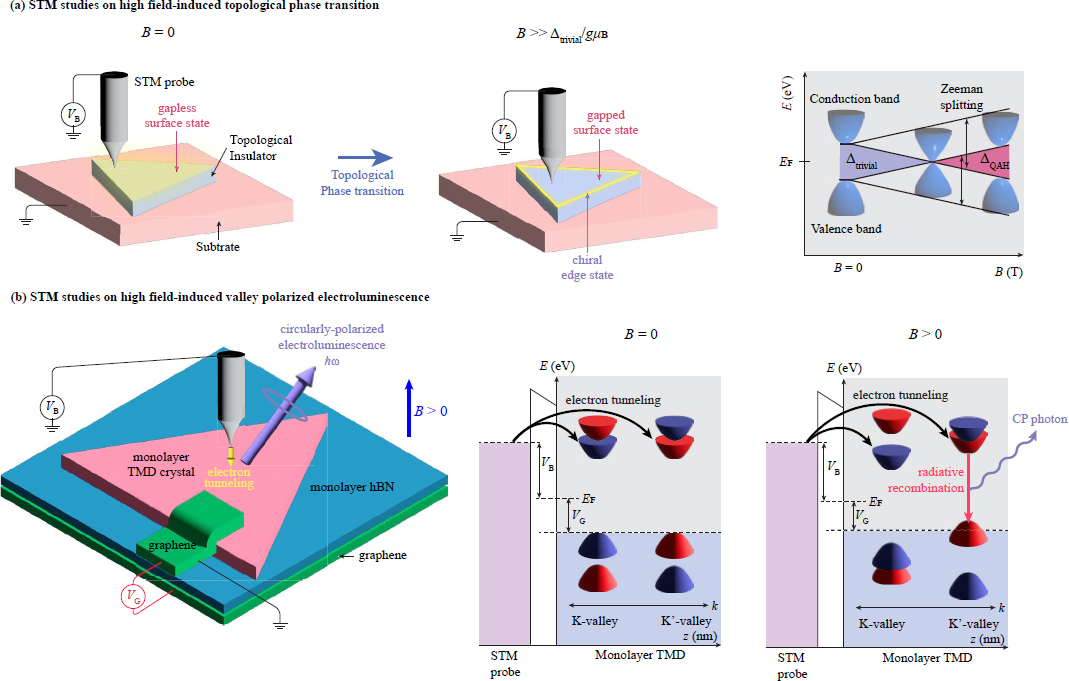

Currently none of the NHMFL facilities are equipped with any high-field compatible scanning probe microscopy (SPM) important for both condensed matter physics and QIS research, such as the scanning tunneling microscopy/spectroscopy (STM/STS) for atomically resolved imaging and spectroscopic studies of conducting and semiconducting materials; variations of the atomic force microscopy (AFM) for measurements of conductance (c-AFM) and work functions (Kelvin probe force microscopy, KPFM), magnetic force microscopy (MFM) for spatially resolved magnetization detection, and near-field scanning optical microscopy (NSOM) for subwavelength local detections of optical properties of materials. To better illustrate the research opportunities offered by SPM in high magnetic fields, the committee shows two examples in Figure 4-9 on how studies of (A) the edge states of topological insulators, and (B) the optoelectronic responses in monolayer semiconducting transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) may be enabled by SPM in high magnetic fields. Additionally, broadband optical measurement capabilities, such as Raman and photoluminescence spectroscopy, pump-probe spectroscopy, linear and nonlinear spectroscopy, and quantum light spectroscopy using entangled photons or squeezed light, which are highly desirable for condensed matter physics and QIS research, are either limited or not available in most NHMFL facilities.

___________________

42 As an example, see T. Nomura, P. Corboz, A. Miyata, et al., 2023, “Unveiling New Quantum Phases in the Shastry-Sutherland Compound SrCu2(BO3)2 Up to the Saturation Magnetic Field,” Nature Communications 14(1):3769, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-39502-5.

Examples of condensed matter experiments that may be enabled by scanning probe microscopy in high magnetic fields. (a) Topological insulators, such as Sb2Te3 thin films, when doped with sufficient densities of magnetic elements, can result in long range ferromagnetic order and exhibit the quantum anomalous Hall (QAH) effect at low temperatures. However, magnetic dopant atoms create disorder in the sample, which limits the temperature at which quantized conductance can be observed to extremely low temperatures (Park et al. 2024). To solve this issue, rather than inducing the QAH-state through magnetization, a strong magnetic field of tens of tesla may be used. Without the application of a magnetic field, the top and bottom surface states of a thin topological insulator would hybridize to create a topologically trivial gap (Δtrivial). Owing to Zeeman splitting, there are shifts in the energy levels of the surface states once an out-of-plane magnetic field is turned on, which results in a band-crossing for sufficiently large magnetic fields to open a nontrivial gap (ΔQAH). In this case, the bands attain a Chern number of 1, thereby exhibiting the QAH effect. Scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) can be used to trace the opening of ΔQAH with the evolution of the applied magnetic field and observe the chiral edge states. (b) Monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) are direct bandgap semiconductors with well-defined spin-polarized valence and conduction bands as well as spin-valley coupling as shown in the upper right panel for the energy bands in the first Brillouin zone. Hence, they can emit circularly polarized (CP) light through photoluminescence excited by CP light or electroluminescence induced by spin-polarized electronic excitations. A feasible approach to demonstrating CP electroluminescence is through applying a high magnetic field. Without the presence of an external magnetic field, if the sample is gated such that the chemical potential is just above the valence band maxima, electrons that tunnel from the STM probe into the empty conduction band cannot relax into the occupied valence band owing to Pauli exclusion principle. However, by turning on an external magnetic field, the spin-up polarized bands will shift upward while the spin-down polarized bands will shift downward, creating an asymmetry in the −K and +K valleys. With a large enough magnetic field, at the −K valley, the spin-up valence band will rise above the chemical potential, providing empty states for electrons tunneling from the STM probe to the conduction band to relax into and simultaneously emitting CP photons.

NOTE: See A. Park, A. Llanos, C.-I. Lu, et al., 2024, “Phonon and Defect Mediated Quantum Anomalous Hall Insulator to Metal Transition in Magnetically Doped Topological Insulators,” Physical Review B 109(7):075125, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.109.075125.SOURCE: Courtesy of Nai-Chang Yeh.

In pulsed magnetic fields, an analysis of the NHMFL PFF (significant) publications (from 2023) indicate less than half of the published works actually utilized the pulsed magnets and there were a very limited number of new (developed within the last 10 years) pulsed magnetic field methods employed. This indicates that efforts are placed on staff to publish high impact science while less effort is evident on developing new methods for pulsed magnetic fields. Conversely it could also mean that the new methods that are developed for pulsed magnetic fields are less likely to yield high impact publications hence the tendency to focus research on established methods.

Finding: Most condensed matter experiments that can be carried out in high-magnetic-field facilities to date have been limited to a few experimental probes

Conclusion: The U.S. high-field leadership (NSF and NHMFL) has not made sufficient efforts in the development of cutting-edge capabilities and techniques in the micro-second pulsed field regime as this is an actively accessible region of phase space, and technologies have developed that enhance the measurement potential of materials.

Conclusion: Unfortunately, this conservative behavior is resulting in the U.S. capabilities lagging behind efforts abroad.

Conclusion: There are opportunities for increasing the science output by better instrumentation of existing magnet facilities.

Conclusion: Among these opportunities is the integration of nanostructured samples and nano-probes for measurements.

In addition to developing cutting-edge instrumentation at existing high-field facilities, there is considerable value in providing high fields at other facilities (X ray, neutron, FEL) or indeed the reverse (e.g., high pressure or optics at NHMFL).

In comparison with the European Union labs where technological development in instrumentation is seen as a value in its own right so that research staff members can focus on developing state-of-the-art instruments for high-magnetic-field measurements, NHMFL research staff members are often under pressure to provide support primarily for rapid scientific publications, instead of instrument development. In the case of the Chinese High Magnetic Field Laboratory (CHMFL), there are a large number of supporting staff members (105) working with 80 researchers on developing the necessary research tools for high-magnetic-field measurements. For instance, in contrast to the absence of scanning probe microscopy in NHMFL high-field facilities, CHMFL has already developed STM, AFM, and MFM capabilities in magnetic fields up to 35 T and 45 T and for measurement temperatures ranging from 4.2 K to 300 K. Additionally, CHMFL has developed chemical reaction and materials growth facilities for reaction temperatures from 300 K up to 1200°C in high magnetic fields up to 10 and 20 T. Advanced magneto-optical measurement capabilities—such as systems for studying ultrafast and micro magneto-optical Kerr effect (MOKE)—are also available at CHMFL and NHMFL. These examples clearly illustrate the shortcomings of the current U.S. system in maintaining global leadership in high-magnetic-field science and technology.

Finding: The strong science focus at U.S. user facilities inhibits careful methods and instrumentation development that does not immediately turn into a science publication.

Conclusion: There is a need to provide a supporting environment to nurture long-term advanced technical development.

Magnitude of Investment in High-Magnetic-Field Research

The United States is investing ~$50 million per year in NHMFL, as evidenced by the annual NSF budget. For comparison, China is investing in a RMB ¥2.1 billion (~USD $300 million) upgrade and RMB $30 million (~USD $4.3 million) for annual operation of CHMFL. It should be noted that the personnel costs in China are much less than those in the United States so that the annual operation spending at CHMFL must be properly rescaled for a meaningful comparison with that at NHMFL. As noted earlier, there are up to 105 supporting staff members at CHMFL to work with 80 researchers, which is a scope well beyond the level of staff support at NHMFL. Additionally, China is coupling its pulsed field capabilities to industrial sectors, including efforts in magneto-forming and wind turbine magnet charging.

The European Magnetic Field Laboratory (EMFL) consists of three labs at four sites (HFML at Nijmegen, Netherlands; HLD at Dresden, Germany; LNCMI at Toulouse and Grenoble, France). EMFL acts as a single laboratory to represent Europe in high-magnetic-field science and technology by coordinating magnet technologies and new experiments with common committees and networking, with the mission of developing and operating world class high-magnetic-field facilities for excellent research by in-house and external users. The substantial support has enabled impressive instrumentation developments in high-resolution NMR and X-ray measurement capabilities in pulsed magnetic fields.

Finding: There are global challenges from China, the European Union, and Japan. The United States is no longer in a clear lead.

Finding: There is a strong need for advanced instrumentation developments associated with all high-field facilities to optimize the scientific and technological output from these facilities.

It is worth noting that the incorporation of scanning probe microscopy as a tool in high-magnetic-field instruments would affect many scientific research frontiers. Some of the areas were mentioned previously, such as quantum lights, entangled photons, and squeezed states of light that can enable new high-magnetic-field

measurement capabilities, not only in condensed matter physics and quantum information science but also in molecular and biological systems.

Conclusion: The impact of research such as quantum lights, entangled photons, and squeezed states of light should be increased by investment in experimental methods to make precise measurements at high fields.

Key Recommendation 5: U.S. government agencies—including the National Science Foundation, National Institutes of Health, Department of Energy, and Department of Defense—should jointly provide proper resources that are designated to support a team of talents nationally and at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory to develop state-of-the-art instruments and methods for high-magnetic-field science and technology.

As discussed in a subsequent chapter, there is an existing mechanism for this kind of investment.

Key Recommendation 6: The United States must establish its leading role in the combination of high-magnetic-field studies with X-ray free lasers (XFELs), synchrotron radiation source, and neutron sources. This could be best accomplished by a National Science Foundation–supported science and technology center focused on the development of novel technology and cutting-edge science applications for quantum and atomic, molecular, and optical high-magnetic-field studies at XFELs, synchrotron radiation sources, and neutron sources.

Finding: The highest accessible pulsed field at NHMFL has exceeded 100 T only once and the highest steady field remains 45 T; there has been no progress over at least a decade worldwide. There are substantial scientific advantages to push beyond these boundaries. Higher fields are attainable by developing existing technology.

Key Recommendation 8: The National Science Foundation should fund the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory to construct a successor to its 45 T hybrid magnet with the construction of a direct current magnet to reach 60 T and, with the Department of Energy, a pulsed magnet to a field of 120 T.

NATIONAL SECURITY IMPLICATIONS

Technology Transfer from Science to Defense (and Vice Versa)

National security challenges often garner the attention and budgets of significant global military and government powers. Some of the best and brightest scientists and engineers will work diligently to solve very difficult problems to ensure peace and provide deterrence to prevent technological surprise by potential or active hostile states. A good example of a technological effort that transitioned from national security technological development to condensed matter physics diagnostic development is the case of the “Chirped Fiber Bragg Grating Diagnostic.”43 In this case, a high explosives detonation wave diagnostic, which was born from an optical strain gauge device used in bolt dilation sensing technology, was subsequently adapted to sense the detonation velocity (of order 9 km/sec) in modern high explosives. This key diagnostic deployed to national security tests was later adapted and exploited to sense tiny dilations indicative of magnetic-field driven structural phase transitions in quantum matter in extremely high and rapidly increasing (micro-second duration) ultrahigh magnetic fields. The optical nature and sub-micro-second response times of the technique were a near perfect match between the high-field science and national security applications. This is not a unique circumstance, as many high-magnetic-field devices and diagnostic developments have gone hand in hand with unrelated but technologically overlapping applications.

High Magnetic Fields for Research

In 1995 and 1996, the Los Alamos National Laboratory hosted a group of about 20 international scientists from Russia, Japan, Australia, Switzerland, and Germany to participate in a series of experiments utilizing explosively driven flux compression generators. The DIRAC series of experiments44 is a notable example of international collaboration to endeavor to solve a difficult scientific challenge with modern tools related to national security competencies. Since those experiments, advancements of magnetic flux compression generators and very high current generators have progressed in both the United States and Russia. In 1998 scientists from Arzamas-16 reported on a successful generation of a record setting high magnetic field of approximately 2800 Tesla using Russian DISK generators (reported at

___________________

43 G. Rodriguez, R.L. Sandberg, Q. McCulloch, S.I. Jackson, S.W. Vincent, and E. Udd, 2013, “Chirped Fiber Bragg Grating Detonation Velocity Sensing,” Review of Scientific Instruments 84(1), https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4774112.

44 Los Alamos National Laboratory, 1996, “The Dirac Series,” Los Alamos Science 24, https://sgp.fas.org/othergov/doe/lanl/pubs/00326621.pdf.

the 1998 Megagauss Conference). In 2018 at the ISSP in Kashiwa, Japan, a record indoor ultrahigh magnetic field (destructive to probes and samples) of 1200 Tesla45 was reported using the Electromagnetic Flux Compression method. While these peak field intensities are impressive, there remains a significant opportunity to develop measurement techniques that are impactful to condensed matter physics experimentation. The loss of a precious sample and the difficulties of reproducing the experiment on the same sample make this method more applicable to bulk synthesized samples and optical methods as dB/dt is typically of order 108 T/sec or more. Such large dB/dt rates induce significant electrical currents (known as “eddy currents”) into metallic samples or anything else conducting near the magnet system. Induced eddy currents can be so large that vaporization of samples or conductors occurs for conductive cross sections approaching 1mm2. However, nano-structured samples as well as the vast menagerie of low conductivity materials can provide amazing opportunities for the bold and imaginative research that is willing to take a path less traveled. Such research endeavors are typically not for the masses but for the true explorers that have become far too infrequent in the United States over the past 10 years.

Kinetic Energy Delivery Platforms

The U.S. Naval Surface Warfare Center Dahlgren has developed a significant kinetic energy delivery platform that uses the concept of a “rail gun” to generate a pure kinetic energy projectile with a muzzle energy more than 10 MJ and projectile velocities exceeding 2.5 km/sec. In 2021, the project was placed on “pause” according to a news article from “Task & Purpose.”46 It is unclear at this time what the future holds for such weapon platforms and the research and development that is intertwined to some degree with pure science efforts on magnet and high-strength and high-conductivity wire development, high-voltage and high-current switch technology, as well as advancements in energy storage systems capable of prompt discharge. These technologies are mutually beneficial to pulsed magnetic field technology development, including the magnet systems and supporting diagnostic capabilities. The United States should continue to invest in, and advance capabilities related to this topic.

___________________

45 D. Nakamura, A. Ikeda, H. Sawabe, Y.H. Matsuda, and S. Takeyama, 2018, “Record Indoor Magnetic Field of 1200 T Generated by Electromagnetic Flux-Compression,” Review of Scientific Instruments 89(9), https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5044557.

46 J. Keller, 2021, “The Navy’s Electromagnetic Railgun Is Officially Dead,” Task & Purpose, https://taskandpurpose.com/news/navy-electromagnetic-railgun-dead.

Very High Electromagnetic Field Pulse

On September 1, 1859, a natural phenomenon of the Sun occurred that is known as a coronal mass ejection (CME). Sunspots and sunspot activities are connected to plasma ejection and magnetic field disturbances observable at the surface of the sun and result in an increase in auroral activity observable on Earth. Days before the September 1, 1859, event, a prior CME occurred that amplified the effect (paved the way) of what is referred to as the “Carrington Event.”47 The significance of this event is documented by individuals around the globe with multiple reports of damages to telegraph equipment and the electrical infrastructure, destroying equipment and even causing fires at some telegraph stations. The early electrical systems of the time were primitive by today’s standards, but consequences of the event provide us with some insight into the vulnerability of our electrical infrastructure should such a circumstance occur today. Additionally, there are human caused events such as the “Starfish Prime” nuclear test in July 196248 that allegedly impacted civilian infrastructure in Hawaii some 900 miles away from the high-altitude event. Induction of transient voltages and currents into large circuits (utility scale) as well as devices can be driven by manmade sources as well as natural events. The magnitude of manmade events pale in comparison to a large CME like the Carrington event but can have detrimental impacts on a more local scale.49 Condensed matter physics research often immerses a submillimeter-sized sample in the very center of the highest field region of ultrahigh-magnetic-field pulsed magnets. This situation results in an incredibly difficult to mitigate problem for high-magnetic-field researchers. With a dB/dt of ~108 T/s the induced eddy currents into the sample and in some cases electrical circuits attached to the sample causes intense electromagnetic interference. Research of intense magnetic field generators and sensitive diagnostics that are directly immersed around and within the transient fields provide us with remarkable potential to reject such unwanted electromagnetic interference. Development of high-magnetic-field measurement techniques must operate within these electromagnetic harsh environments and provide us with the ability to measure small changes in matter subject to very high transient magnetic fields.

Recommendation 4-1: It is recommended that efforts continue to develop techniques that can reject such intense electric field inductions sourced by

___________________

47 D.S. Kimball, 1960, A Study of the Aurora of 1859, Geophysical Institute at the University of Alaska.

48 F. Narin, 1962, “A ‘Quick Look’ at the Technical Results of Starfish Prime. Sanitized Version,” Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory, https://doi.org/10.21236/ADA955411.

49 C. Kopp, 1996, “The Electromagnetic Bomb - A Weapon of Electrical Mass Destruction,” https://www.academia.edu/65643445; M. Abrams, 2003, “The Dawn of the E-Bomb,” IEEE Spectrum https://spectrum.ieee.org/the-dawn-of-the-ebomb.

transient magnetic fields like the single-turn systems and the electromagnetic or explosively driven magnetic field implosion systems.

Research on Materials Processing in Magnetic Fields and Industrial Applications of High Magnetic Fields

Pulsed magnetic fields have been used for electromagnetic forming of metallic sheets into specialty shapes for decades.50 More recently, the automobile industry has developed methods that use pulsed electromagnets to drive sheets of conductive metals into forms. The velocities used (15–300 m/s)51 are controlled by the magnitude of the impulse field which is governed by the charge voltage on the capacitor bank. Pulsed magnetic fields can also be used for welding and joining of dissimilar metals by similar methods.52 The methods above, all utilize a basic combination of three elements, a pulsed magnetic field, a conductive sheet of metal to be formed, and a receiving die. Unlike conventional die casting methods that rely on high pressure hydraulics or related (slow) large forces to stretch and strain the sheet into a form, the Electromagnetic Forming (EMF) process simply uses the principle of the Faraday effect to accelerate a metallic sheet into a receiving die. If the velocity is of the correct magnitude and the material characteristics are correct the sheet will hydro-dynamically flow into the receiving mold without many of the challenges that conventional punch and die forming are limited by. Thinning at high gradient regions can be reduced if the parameters are chosen correctly. There are challenges of course as bounce back and wrinkling can occur if the correct parameters are not met. This EMF technology has the potential to change with the advances in computational power which in turn can potentially improve metal manufacturing in industries like the automotive and aerospace industries that rely on lightweight metals and the need to join dissimilar metals.

Thermomagnetic Processing

“Processing materials under magnetic fields is an underexplored technique to improve structure and mechanical properties in metals and alloys. Magnetic fields

___________________

50 G.K. Fenton and G.S. Daehn, 1998, “Modeling of Electromagnetically Formed Sheet Metal,” Journal of Materials Processing Technology 75(1):6–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-0136(97)00287-2.

51 M. Lim, H. Byun, Y. Song, J. Park, and J. Kim, 2022, “Numerical Investigation on Comparison of Electromagnetic Forming and Drawing for Electromagnetic Forming Characterization,” Metals 12(8), https://doi.org/10.3390/met12081248.

52 Y. Zhang, P. L’Eplattenier, G. Taber, A. Vivek, G. Daehn, and S. Babu, 2008, “Numerical Simulation and Experimental Study for Magnetic Pulse Welding Process on AA 6061-T6 and Cu101 Sheet,” Dearborn, MI: 10th International LS-DYNA Users Conference, https://www.dynalook.com/conferences/international-conf-2008/SimulationTechnology2-2.pdf.

can alter phase stability, modify diffusion characteristics, and alter material flow substantially.”53 In castings, magnetic fields can be used during melting of the alloy, during solidification, or during postprocessing operations such as heat treatment to achieve structural changes.

Thermomagnetic processing is a potential transformational technology for U.S. manufacturing that enables microstructures and material properties unattainable by other industrial processing methods. A key benefit of superconducting magnet technologies is the minimal amount of energy needed to adapt to an industrial process, because once at field (regardless of how high), the magnet goes into ‘persistent mode’ and requires no energy to maintain field other than recondensing the cryogens. The current state of superconducting magnet technology allows for a tradeoff between field strength and bore size. For example, Cryomagnetics (Oak Ridge, Tennessee) recently built a shielded 20-inch bore, 2 T magnet with an 18-inch axially uniform static field. This magnet is large enough to house an induction heating insert for processing industrially relevant steel and aluminum components. This is the largest magnet Cryomagnetics has fabricated. Similarly, ORNL houses three large bore (2 × 5 inch, 8 inch) superconducting magnets, all capable of 9 T and housing induction furnaces capable of reaching temperatures up to 2000°C in various environments, including air, Ar, N2, H2, He, ammonia, and vacuum. The 8-inch bore magnet is the first of its kind industrial prototype which can process small steel components. It’s an excellent demonstration but limited on the size of component that can be processed. Much larger bores are needed to expand significantly into the steel and aluminum sectors where thermomagnetic processing could have a significant impact on part throughput and GHG emissions.

If larger bores can be achieved, that will expand the potential experimentation and application spaces in which high-magnetic-field processing can be used. Likewise, in some cases, the applied fields have a linearly increasing effect on or a threshold for affecting material properties and, hence, higher applied fields are enabling. For industry, larger bore sizes in excess of 30 inches with fields between 2 T to 9 T would increase scalability of the technology. From a science perspective, larger bores with increasingly higher fields would allow for generating extreme high-static fields (>50 T) by incorporating nested superconducting inserts. This would enable exploration into areas of physics that currently elude researchers. Perhaps most significantly, confirmation of the Axion particle could be attempted in the search for dark matter. Only China and Japan have large enough magnets to facilitate these future experiments.

___________________

53 D. Weiss, B. Murphy, M.J. Thompson, et al., 2021, “Thermomagnetic Processing of Aluminum Alloys During Heat Treatment,” International Journal of Metalcasting 15(1):49–59, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40962-020-00460-z.