Constructing Valid Geospatial Tools for Environmental Justice (2024)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

1

Introduction

President Biden’s Executive Order (E.O.) 14008 (Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad) established the Justice40 Initiative and directed the White House Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) to develop a whole-of-government approach to environmental justice (EJ) (EOP, 2021). Justice40 sets a goal that disadvantaged communities reap 40 percent of federal investment benefits in specific sectors: energy, housing, health and resilient communities and infrastructure, economic and workforce development, transportation, and water. To advance this initiative, E.O. 14008 charged CEQ with creating a geospatial tool, the Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool (CEJST),1 that will be used to identify the communities across the United States and its territories eligible for Justice40 investment benefits.

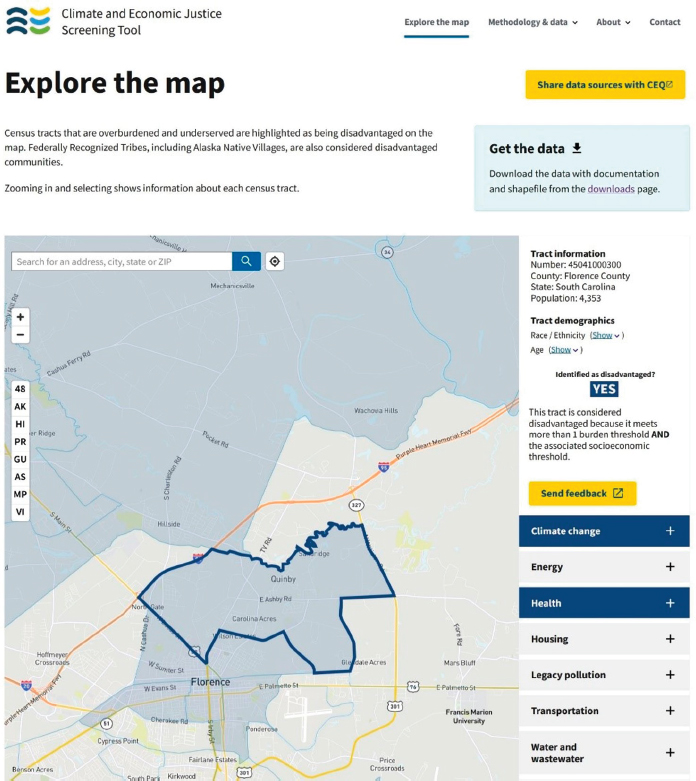

CEJST represents the first time a tool of this kind has been developed at the federal level to identify the disadvantaged communities in terms of climate, energy, sustainable housing, employment, and pollution burden for the purpose of federal investment. As with any novel initiative, it requires breaking new ground in terms of research methodologies and data use. It calls for data of sufficient granularity and scientific validity to compare communities across states and regions, and in terms of their rural and urban context. Figure 1.1 illustrates an example of CEJST output, identifying a specific census tract in South Carolina as disadvantaged. CEJST highlights this tract based on meeting criteria for its climate change and health indicators, and socioeconomic status. These criteria are discussed in more detail throughout the report.

This report summarizes the conclusions and recommendations of a National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (National Academies) committee regarding the directions of a future data strategy for CEQ tools. This chapter describes the statement of task provided to the committee, and a brief history of the use of geospatial

___________________

1 See https://screeningtool.geoplatform.gov/ (accessed October 3, 2023).

tools for addressing EJ issues. The committee and committee processes are described below, as is the report organization. Whereas the committee was explicitly asked to provide recommendations regarding CEQ tools, the good practices described in this report are applicable to the developers of other geospatial tools.

STATEMENT OF TASK

Under the sponsorship of the Bezos Earth Fund, the National Academies convened an ad hoc multidisciplinary committee of 11 experts to consider how environmental

health and geospatial data and approaches were built into various environmental screening tools to identify disadvantaged communities. The committee was asked to consider how data at a variety of scales and resolution may be integrated and analyzed and to make recommendations for an overall data strategy for CEQ in the development of future versions of CEJST or other tools. The statement of task provided to the committee is found in Box 1.1.

HISTORY

Since the emergence of a national EJ movement in the 1980s, mapping and the use of GIS (geographic information systems) have been important for analyzing and communicating unequal and disproportionate environmental burdens for communities of color and other historically marginalized communities (Commission for Racial Justice, 1987; GAO, 1983; Kumar, 2002). Following issuance in 1994 of E.O. 12898 “Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations” (EOP, 1994), federal agencies, especially the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), state governments, and nongovernmental institutions sought to define “environmental justice” and “disproportionate burden” and to explore ways to map

BOX 1.1

Statement of Task

A committee of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine will analyze how environmental health and geospatial data and environmental screening tools can inform CEQ’s Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool by conducting a data assessment to assist CEQ in considering the disparities it has prioritized. The committee’s assessment will build on the following tasks:

- Scan of existing screening tools for types of data and approaches used to identify disadvantaged communities (e.g., CEQ-funded Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool, Environmental Protection Agency Environmental Justice Screen)

- Identification of the types of data (e.g., environmental, socioeconomic, energy, transportation) needed for CEQ’s screening tool(s)

- Evaluation of current data availability, quality, and spatial and temporal resolutions, as well as key data gaps

- Discussion of approaches to process, integrate, and analyze these data (e.g., weighting, consideration of additive effects)

The committee will provide recommendations to be incorporated in an overall data strategy for CEQ’s tool(s).

and identify both (University of California Hastings College of Law, 2010). By 2001, each of the 10 EPA regional offices used some form of EJ survey tool internally to map potential EJ communities for enforcement prioritization of environmental regulations or enhanced scrutiny, based primarily on demographic indicators for the likelihood of experiencing environmental injustices (e.g., the number or percentage of racial minority residents, indicators of income or poverty, and population density) (Kumar, 2002). In 2015, EPA released EJScreen, the first publicly available interactive mapping tool that used a nationally consistent dataset and approach for combining environmental and demographic socioeconomic indicators at the Census Block Group level.2 EJScreen did not provide thresholds for identifying or prioritizing communities for action, but it did become one of a few examples or templates for the development of EJ mapping and screening tools for other federal agencies, states, and local communities.

Publicly accessible state-level EJ mapping or screening tools were developed in parallel with those of the federal government but took diverging paths on how to define and map EJ or disadvantaged communities (Payne-Sturges et al., 2012). In 2008, Massachusetts released its Environmental Justice Viewer,3 an interactive, online map that displayed “environmental justice populations” defined by demographic criteria thresholds by Census Block Group—percent minority, percent lower income, percent limited English speaking, or percent foreign born—reflecting the EJ policy issued by the state’s Office of Environmental Affairs in 2002. Some states followed the Massachusetts model, defining and mapping “environmental justice” or “overburdened” communities primarily based on demographic thresholds (e.g., Connecticut [2022]4, Illinois [2018],5 Maryland [2017],6 Pennsylvania [2022],7 and Rhode Island [2022]).8 A different model was released as California’s CalEnviroScreen in 2013 after more than a decade of development (Lee, 2021). The latter defined and mapped “cumulative impact” scores for every ZIP code in the state (later changed to census tracts)—a cumulative summary of environmental burdens, exposures, health status, and social vulnerabilities. CalEnviroScreen’s approach, and specifically its mapping of cumulative impacts, has been influential for community and academic researchers, state governments (Michigan, New Jersey, New York, and Washington State), and the federal government (Centers

___________________

2 See U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA)’s website for “How Was EJScreen Developed?” https://www.epa.gov/ejscreen/how-was-ejscreen-developed (accessed December 22, 2023).

3 See updated Environmental Justice Map, https://www.mass.gov/info-details/massgis-data-2020-environmental-justice-populations (accessed December 22, 2023).

4 See Connecticut’s definition of EJ communities at https://portal.ct.gov/DEEP/Environmental-Justice/05-Learn-More-About-Environmental-Justice-Communities (accessed February 9, 2024).

5 See Illinois’s definition of EJ at https://epa.illinois.gov/topics/environmental-justice/ej-policy.html (accessed February 9, 2024).

6 See Maryland’s EJ definition at https://mde.maryland.gov/Environmental_Justice/Pages/Landing%20Page.aspx (accessed February 9, 2024).

7 Pennsylvania’s Office of Environmental Justice includes their definition of EJ at https://www.dep.pa.gov/publicparticipation/officeofenvironmentaljustice/Pages/default.aspx (accessed February 9, 2024).

8 See Rhode Island’s definition of EJ at https://dem.ri.gov/environmental-protection-bureau/initiatives/environmental-justice (accessed February 9, 2024).

for Disease Control/Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry [CDC/ATSDR], Department of Energy, and Department of Transportation). Some have described “cumulative impact” mapping as the “next generation” of EJ mapping (Lee, 2020). Cumulative impacts will be discussed in further detail in Chapter 3 of this report.

In response to Section 223 of E.O. 14008 “Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad” (EOP, 2021), CEQ and a variety of covered federal agencies began the process of developing or launching publicly accessible mapping or screening tools that could be used to identify “disadvantaged communities” to meet the Justice40 Initiative goal that “40 percent of the overall benefits of certain Federal investments flow to disadvantaged communities that are marginalized, underserved, and overburdened by pollution.”9 In July 2023, the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) released guidance to federal agencies on community engagement practices for regularity purposes.10 While CEJST is not a regulatory tool, the OIRA guidance provides support for the federal government utilizing community engagement. CEQ launched a beta version of CEJST in February 2022 (Chemnick, 2022), identifying “disadvantaged communities” (DACs) as census tracts in which higher percentiles of environmental or health criteria are paired with markers of economic vulnerability (described in more detail in this chapter). The White House subsequently issued guidance in January 2023 directing covered federal programs to use CEJST as “the primary tool” to geographically identify DACs for the purposes of initiating implementation of the Justice40 Initiative by October 2023 (EOP, 2023).

However, the White House guidance also acknowledged and allowed that some federal agencies already use other tools and methodologies to identify DACs that predate CEJST. In addition to EPA’s EJScreen (2015),11 these earlier tools included the CDC/ATSDR Social Vulnerability Index (2016),12 the Census Bureau’s Community Resilience Estimates (2020),13 and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) National Risk Index (2020).14 Other federal tools were launched at about the same time as CEJST, including CDC/ATSDR’s Environmental Justice Index (2022),15 the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Climate Mapping for Resilience and Adaptation (2022),16 the Department of Energy’s Energy Justice Mapping Tool—

___________________

9 See the White House’s web page for “Justice40: A Whole-of-Government Initiative” https://www.white-house.gov/environmentaljustice/justice40/ (accessed October 4, 2023).

10 See the White House’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA), “Broadening Public Engagement in the Federal Regulatory Process,” https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Broadening-Public-Participation-and-Community-Engagement-in-the-Regulatory-Process.pdf (accessed December 15, 2023).

11 See https://www.epa.gov/ejscreen (accessed September 18, 2023).

12 See https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/index.html (accessed September 18, 2023).

13 See https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/community-resilience-estimates.html (accessed February 9, 2024).

14 See https://hazards.fema.gov/nri/ (accessed February 9, 2024).

15 See https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/eji/index.html (accessed February 9, 2024).

16 See https://resilience.climate.gov/ (accessed February 9, 2024).

Disadvantaged Communities Reporter (2022),17 and the Department of Transportation’s Equitable Transportation Community Explorer (2022).18 All these federal mapping tools focus on identifying socially vulnerable or environmentally burdened communities, and all employ cumulative burden measures or composite indexes of social and environmental risk or burden. None of these tools or metrics share the same methodology. More information on each of these tools can be found in Chapter 4 of this report.

COMMITTEE COMPOSITION

An interdisciplinary group of experts was convened specifically to deliberate on the task to inform the future data strategies for CEQ’s tool(s), as described in Box 1.1. Expertise on the committee included data and geographical sciences, geospatial analysis, environmental economics, environmental health, public health, EJ, and environmental science. Those with experience using or creating relevant geospatial tools at the federal and state levels were specifically sought for committee membership, as well as those with experience applying information derived from such tools in research or decisions regarding public health, water, energy, the environment, or infrastructure. Members of the committee have experience addressing EJ issues from the research, decision-making, and advocacy points of view. A range of perspectives and diversity were intentionally considered in committee composition, including diversity in where members live and work, race/ethnicity, age, and gender. Appendix A provides biographies of committee members.

INTERPRETATION OF THE STATEMENT OF TASK AND STUDY BOUNDARIES

The task given to the committee (Box 1.1) included many nuances. The sponsor of the study (Bezos Earth Fund) asked the committee to develop recommendations “to be incorporated in an overall data strategy for CEQ’s tool(s).” The committee was directed by the sponsor that this study was not a review or evaluation of CEJST (thus the use of “scan” in the statement of task). Instead, the committee would consider approaches used in several geospatial EJ tools and how those approaches may inform CEJST and potential future CEQ tools. CEJST is CEQ’s only tool at present, but the language in the task implies interest in strategies applicable to future tools. Based on language in the statement of task and discussions with the study sponsor, the committee established some boundaries of what would and would not be addressed in its report:

- The committee would focus on geospatial EJ tool development and the selection and integration of the information used as input for such tools;

___________________

17 See https://curie.pnnl.gov/document/energy-justice-mapping-tool-disadvantaged-communities-reporter (accessed February 9, 2024).

18 See https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/0920984aa80a4362b8778d779b090723 (accessed February 9, 2024).

- The committee would not comment on policy or political decisions informing any approaches taken in the development of any EJ tool; and

- The committee would not comment on any resource allocation decisions made based on the results (i.e., outputs) of any tool.

COMMITTEE INFORMATION GATHERING

The extensive collective expertise and experience in several disciplines and practices relevant to the statement of task was a major source of internal information for the committee. That expertise was augmented by research of the published scientific literature and of technical documentation from several geospatial tools, and from input from a variety of sources including invited speakers, panel discussions, and guests to multiple public meetings, webinars, and a public workshop. Many of the experts consulted were intimately familiar with EJ tools developed at different scales (e.g., state, national) or with tools developed internationally. Appendix B provides the agendas for the committee’s public events.

An especially important and influential part of the committee’s information gathering was its public workshop, summarized in a proceedings-in-brief (NASEM, 2023a). The committee invited speakers and participants representing community organizations, government entities, academe, and Tribal nations (a participant list is included in Appendix B), and the agenda was divided into presentations, panel discussions, a hands-on exercise in which participants could explore CEJST, and plenary discussion. Participants shared their lived experiences and observations and how those compared with results generated by CEJST. They provided input on the types of indicators (i.e., the individual concepts being measured) and datasets for inclusion that could be useful in the tool, how data might be analyzed, the visual presentation and the way tool results were communicated, on aggregating indicators and determining thresholds of disadvantage, on analyzing the data against localized tools, investment tracking, the importance of community involvement, and other topics.

The committee’s workshop emphasized the importance of incorporating community voices in an EJ tool’s data strategy—one that integrates community input with quantitative data, that uses community input to validate choices regarding how community and disadvantage are defined and how disadvantage could be measured, and that uses community input to validate tool results against the lived experience of the community. These concepts formed the foundation of the committee’s conceptual framework—its vision—for a data strategy and approach to EJ tool development (see Chapter 3).

REPORT ORGANIZATION

The committee developed an approach to its work based on some early conclusions: (1) a valid and useful geospatial EJ tool development requires a transparent structured process; (2) community voices are integral to valid EJ tool construction; and (3) a data strategy appropriate for CEQ and CEJST would also be appropriate for other EJ tool developers and tools. To increase the usefulness of this report to CEQ—and to expand

the utility of the report recommendations to others—the concepts and recommendations in this report are generalized and applicable to the development or management of any EJ tool. Although there are many sections in the report that describe specific CEJST processes (as appropriate given the statement of task), the committee attempts to highlight many of those as examples for all tool developers.

The committee organized its report to first provide some background and definitions of important concepts in Chapter 2. These include the concepts of community and community disadvantage, burdens, stressors, and impacts, and cumulative impacts. Chapter 2 also explains some reasons behind disproportionate exposure to different hazards. Chapter 3 then describes different approaches and components for building geospatial tools that compile multiple individual indicators into a single tool to represent the complex multidimensional concept being measured (such as community disadvantage, as CEJST attempts to measure). The committee then offers a conceptual framework for tool development and information about community engagement as an elemental part of the framework. In Chapter 4, the committee provides information about previous surveys of EJ tools, and an overview of the approaches employed in 12 different EJ tools. The committee then describes the selection and analysis of indicators and datasets in Chapter 5, including more detail on the categories of burden used to define a disadvantaged community by CEJST. Chapter 6 describes different approaches for integrating indicators (e.g., combining multiple datasets collected for different purposes and scales) and treating the data. Chapter 7 discusses different methods to validate quantitative and qualitative data. Finally, the committee synthesizes its recommendations for a data strategy in Chapter 8.