Constructing Valid Geospatial Tools for Environmental Justice (2024)

Chapter: 5 Selecting and Analyzing Indicators and Datasets and CEJST Indicators

5

Selecting and Analyzing Indicators and Datasets and CEJST Indicators

Determining how to represent the concept to be measured—either quantitatively or qualitatively—is critical in developing any mapping or screening tool. Three decision points are relevant to this chapter: (1) which burden categories to include, (2) which indicators to represent those burdens, and (3) which individual dataset to represent each of those indicators. Chapter 3 described this process to include defining the concept to be measured, selecting a group of indicators and datasets to represent those indicators, and analyzing the indicators and datasets, all within an iterative process for constant refinement and improvement. This chapter begins with a description of useful practices for quantitatively representing the concept to be measured for individual indicators that contribute to disadvantage (e.g., selecting and analyzing indicators; qualitative representation is described in Chapter 7). It then more specifically considers the burden categories and indicators used in the White House Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool (CEJST).1 The text is intended to provide criteria, parameters, and important considerations for making often difficult choices as to which indicators and datasets are selected.

The committee’s statement of task (see Box 1.1) calls on the committee to identify key data gaps that CEQ could address in future iterations of its EJ tool(s). However, without comprehensive documentation of the problem being addressed by their tools, clear definitions of concepts being measured, and descriptions of decision-making rationale, the identification of specific data gaps could be based on erroneous assumptions. Instead, the committee describes several indicators that could be included in a tool such as CEJST based on the committee’s understanding of the CEJST objectives, community feedback received at the committee’s workshop, and expert judgment. The committee provides examples of datasets and sources in Appendix D that could be considered when

___________________

1 See https://screeningtool.geoplatform.gov/en/#3/33.47/-97.5 (accessed March 3, 2024).

identifying future datasets for tools such as CEJST. New data may become available and incorporated into the tool in the future. CEQ could facilitate the development of new, fit-for-purpose datasets through collaborations with federal agencies, nonprofit research organizations, university-based research groups, and private firms who may have proprietary data sources that fill gaps in publicly available datasets.

An exhaustive list of individual indicators and datasets that could be used in an EJ tool such as CEJST is not provided because these, too, need to be determined by the tool developer through a structured indicator development process as described in this report. Identifying appropriate indicators and datasets through an inclusive, community-informed process could lead to improved and more informed identification of representative data, and scientific and technical advances may drive improvements in data quality and completeness. The structured tool development process recommended in this report could minimize the potential for data gaps in future iterations of the tool.2

INDICATOR SELECTION

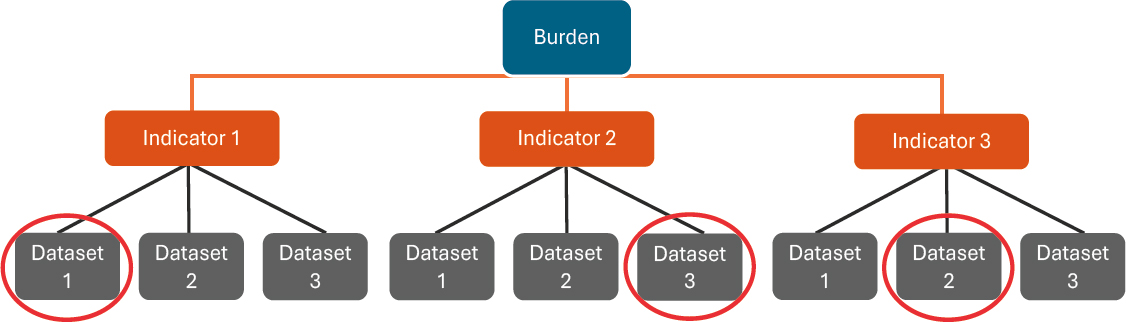

An indicator is a quantitative proxy for an abstract concept, such as “exposure,” “access,” or “disadvantage.” To select appropriate indicators, it is necessary to understand the relationships between burden, indicator, and dataset (see Figure 5.1). These relationships are also described in Chapter 3 as part of the discussion on the conceptual foundation for constructing composite indicators. Creating a compelling rationale for why different indicators should be included is fundamental to creating composite indicators that are interpretable and useful. For example, various environmental exposures such as particulate matter and heat exposures can interact to affect health. A conceptual model could help frame and explain the complex interrelationships (including potential causal relationships) between the indicators and their impacts on the concept being measured. The model will be dependent on the goal of the tool, the structural approach used to develop the tool (including community input) the data available, and the state of the science that allows understanding of interrelationships, causality, and cumulative impacts related to the problem at hand. A model that hypothesizes the interrelationships of the indicators can help the developer (1) select which domains to be included and why and (2) determine if and how cumulative impacts could be captured.

CEJST includes eight categories of what CEQ labels “burdens”—climate change, energy, health, housing, legacy pollution, transportation, water and wastewater, and workforce development. Each of these categories contains a set of indicators that are intended to represent the burden category. For example, the energy category includes two indicators: energy cost and fine particulate matter (PM2.5). The number of indicators differs between burden categories (currently between two and five indicators per category), but each indicator is represented in the tool by one dataset. In general, these datasets are files of numerical quantities that vary in magnitude and in space, intended

___________________

2 Executive Order 14096 authorizes the director of the Office of Science and Technology in conjunction with the Chair of CEQ to “address the need for a coordinated Federal strategy to identify and address gaps in science, data, and research related to environmental justice.”

to align with real-world variation in the property being measured. Although multiple datasets are often available for the same indicator, only one dataset is selected and used in CEJST. For example, many annual average ambient particulate matter (PM2.5) concentration datasets are used across the federal government and scientific community, and each was developed using different methods and data inputs (e.g., statistical modeling, geophysical modeling, satellite remote sensing); the dataset used in CEJST was developed by Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) using a model-monitor fusion approach.

Criteria

The structured process for indicator construction outlined in Chapter 3 includes a systematic approach to indicator and data selection. Table 5.1 outlines technical and practical indicator characteristics to consider when selecting specific measures, with the aim of optimizing quality and validity. A set of practical questions that tool developers could ask is provided. The criteria are not unique to indicator construction and have been used in other contexts (e.g., comparing federal tools for ranking hazardous waste sites for remedial action; NRC, 1994). Technical characteristics emphasize representational, statistical, and geospatial aspects of indicator data and are typically the focus of analysts and modelers. Practical characteristics, such as data availability and cost, are generally of greater interest to indicator program managers and end users. An important technical criterion is validity—how well the indicator reflects the lived experience. Validity will also be discussed in Chapter 7, particularly as it pertains to community involvement. Whether or not the data are findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (FAIR;

TABLE 5.1 Indicator Selection Criteria

| Type | Criterion | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Technical | Validity | How well does the indicator measure the characteristic it represents? |

| Sensitivity | Is the indicator sensitive to changes in the underlying phenomenon? | |

| Robustness | Is the indicator analytically and statistically sound? | |

| Reproducibility | Can the data be independently verified and reproduced? | |

| Scale | Do the geographic and temporal scales of the indicator match those of the characteristic it represents? | |

| Practical | Measurability | How easily can the data be measured quantitatively? |

| Availability | How easily can the data be obtained? | |

| Simplicity | Is the indicator intuitive and easy to interpret? | |

| Affordability | How reasonable are the data collection costs? | |

| Credibility | How acceptable is the indicator to the intended audience? | |

| Relevance | Does the indicator align with the intended goals of the tool? |

SOURCE: Adapted from: Tate, 2011.

Wilkinson et al., 2016) may also be part of the data selection criteria, as might whether the data are consistent with CARE principles (collective benefit, authority to control, responsibility, and ethics)3 and support Indigenous self-determination and innovation (see Box 5.1). Use of FAIR data and CARE principles may serve to enhance the transparency and acceptance of the data as representative of community lived experience. If Indigenous data are used, CARE principles need to be applied so that data are used in a manner in accordance with the rights, knowledge, and values of Indigenous peoples (Carroll et al., 2020).

There are multiple forms of validity, three of which are particularly important for environmental indicators:

- Construct validity: how well an indicator measures what it is supposed to. For example, a composite indicator of cumulative disadvantage with high construct validity embodies the principal dimensions and interactions that govern how disadvantage functions.

- Concurrent validity: the degree of alignment between two measures that should be related. It is typically evaluated using correlation analysis, for example, testing the statistical association between alternative measures of socioeconomic status.

- Content validity: representativeness, essentially the extent to which an indicator includes all principal dimensions of the underlying concept.

Other leading technical criteria include sensitivity, robustness, reproducibility, and spatial or temporal scale. A sensitive indicator will change in direction and magnitude with a change in its real-world proxy. Robustness is a statistical measure of the stability of an indicator to changes in its construction: the indicator should not change substantially with small changes in how it is measured. This is typically assessed using sensitivity analysis. Reproducibility is the ease with which the indicator can be constructed by others independent of the current indicator construction project. The scale criterion is the degree to which the spatial units and time periods of the indicator data align with those of the process or phenomenon being measured. A scalar mismatch can occur when practical considerations of availability, cost, or administrative structures constrain the selection of geographic and temporal scales.

The practical considerations in indicator selection, described in Table 5.1, are often more ambiguous to assess but are no less important. Measurability is the ease of quantitatively manifesting the underlying concept or process. In practice, physical and economic characteristics are easier to measure than more intangible processes, such as marginalization and compounding effects. Failure to incorporate difficult-to-measure concepts can negatively affect the content validity of a single or composite indicator. Availability is the ease of obtaining indicator data for the dimensions, geography, and time frame of interest. Widely available and standardized secondary data are often chosen for indicators used to compare places at the national level, yet they can conflict

___________________

3 See https://www.gida-global.org/care (accessed May 14, 2024).

BOX 5.1

FAIR Data and CARE Principles

To improve infrastructure that supports research data, academics, funding entities, industry, and scholarly publishers have developed a set of principles known as the FAIR (findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable) Data Principles. Specific guidelines have been established and adopted that are intended to increase data sharing and aid science discovery through guidelines for data and metadata design that enhance the reusability of data by computers and humans (Wilkinson et al., 2016).

The CARE (collective benefit, authority to control, responsibility, and ethics) Principles for Indigenous Data Governancea recognize that FAIR data principles ignore the historical contexts of data and power differentials in advancing Indigenous innovation and self-determination. The data of Indigenous Peoples’ comprise:

“(1) information and knowledge about the environment, lands, skies, resources, and non-humans with which they have relations; (2) information about Indigenous persons such as administrative, census, health, social, commercial, and corporate and, (3) information and knowledge about Indigenous Peoples as collectives, including traditional and cultural information, oral histories, ancestral and clan knowledge, cultural sites, and stories, belongings (Carroll et al., 2020)”

The CARE Principles consider self-determination by Native Americans and other Indigenous groups through standards to be applied in conjunction with FAIR data guidelines (e.g., Jennings et al., 2023). The principles are established on the rights of Indigenous Peoples to create value from data related to them in ways that are based on their own world views.

__________________

a See https://www.gida-global.org/careaSee https://www.gida-global.org/care (accessed May 14, 2024).

with construct and content validity. Simplicity and affordability are perhaps the most straightforward criteria: how understandable is the indicator, and how reasonable are the data acquisition costs in money and time? Credibility is the believability and salience of the indicator for scientific and technical applications, as well as for the public. This is also referred to as community validation and buy-in. Involving community members and other interested and affected parties throughout the indicator selection process can be crucial for building credibility, not only to ensure that it represents people’s lived experiences but also to engender trust. This is discussed in more detail in Chapter 7.

Relevance is determined based on alignment between potential indicators and the tool’s objectives. As with all other factors of tool development, indicator relevance needs to be determined through a community partnership and transparent process.

With many potential indicators that meet the criteria described above, relevance can also reflect prioritization among the indicators to ensure that each indicator efficiently achieves its objective without accruing unnecessary costs from data identification, storage, and computation. California’s CalEnviroScreen4 is an example of a tool for which indicator relevance is based on community input. Chapter 7 contains information on including community input while also utilizing tools with scientific rigor.

According to the Technical Support Document for CEJST 1.0 (CEQ, 2022a, p. 17), the indicators and data included in CEJST were selected based on the following parameters:

- The indicator is “[relevant] to the goals of Executive Order 14008 and the Justice40 Initiative”; datasets are “related to climate, environmental, energy, and economic justice”;

- The indicator data are publicly available (not private or proprietary);

- The indicator data cover all 50 states and the District of Columbia at a minimum, and where possible, the five U.S. territories of Puerto Rico, American Samoa, the Northern Mariana Islands, Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands; and

- The indicator data are available at the census-tract scale or finer.

CEJST utilizes 30 indicators across eight categories of burden that meet the above criteria. However, there are many other existing potential indicators that meet their criteria that are not included in the tool. For example, the Environmental Defense Fund’s Climate Vulnerability Index includes 184 indicators (Tee Lewis et al., 2023), most of which also meet CEJST criteria for inclusion. In addition, EPA’s EJScreen5 tool uses similar criteria for indicator selection. CEJST documentation (CEQ, 2022a) does not include a rationale for why some EJScreen indicators are included in CEJST, and some are not. That said, more indicators do not indicate a better tool if indicator quality is questionable or if indicators are repetitive or contradictory. At a public workshop organized by the study committee as part of its information gathering for this report (see Appendix B for the workshop agenda), workshop participants commented that using a national scale could be a limitation and that regional, state, municipal, or otherwise non-national data could provide valuable additional information (NASEM, 2023a).

Temporal Changes in Data

Current geospatial screening tools such as CEJST provide only a static or snapshot-in-time approach for exploring the environmental and social characteristics of neighborhoods and evaluating related burdens. There are two limitations of a snapshot approach that do not allow the incorporation of temporal effects in the tool. First, how long vulnerable communities have been exposed to polluted water, air, or other environmental hazards is important and is not considered in estimating risk burdens. Time

___________________

4 See https://oehha.ca.gov/calenviroscreen (accessed March 4, 2024).

5 See https://www.epa.gov/ejscreen (accessed March 4, 2024).

can be used as a weighting variable for an indicator whose value would be greater, for example, if a pollution source has existed in its present location longer, thus enabling the tool to capture more severe impacts of legacy pollution.

A second limitation of this approach is that it does not allow exploration of how a designation of disadvantage changes over time, for example, whether a tract currently categorized as disadvantaged (or not disadvantaged) was classified similarly in the past. Adding this capability of tracking changes over time could be useful in determining whether investments in disadvantaged communities (DACs) resulted in a reduction of specific climate or socioeconomic burdens or a change in the designation of disadvantage. It may also be useful to examine how spatial patterns and geographic locations of DACs are changing over time in a specific urban area, state, region, or nationwide. Assessing changes over time for specific burdens and overall designation of disadvantage, however, could be problematic and challenging because indicator datasets come from many different time frames and years and are not updated at the same time. If the tool is updated annually, an option could be added for the user to explore whether a particular tract was designated as DAC in previous years or previous versions of the tool. This may require thorough documentation of the updated processes and datasets as well as the resulting changes in the tool output and interpretation. A change in designation can occur for a variety of reasons and may not reflect a change in lived experience in a community. In some cases, a change in designation might be the result of updated data. However, if the data in the previous tool version were old and outdated, then it might not be obvious when changes in the community occurred. In other cases, an update in status might be the result of a change in the data integration approach rather than a change in data.

Temporal Coverage and Frequency of Data

An important consideration when selecting datasets is their temporal coverage and frequency of updating. Datasets are typically available for specific years or sets of years. Datasets are updated at different intervals (e.g., annually), whereas others are updated less frequently (e.g., every 3 years) or have no process for being updated. Additionally, for indicators with high interannual variability (e.g., wildfires and other climate-sensitive indicators), datasets that average over a multiyear period (e.g., 5 years, 10 years) can provide more stable and interpretable estimates. Temporal coverage and updating frequency can, therefore, be driving factors when selecting datasets. Selecting datasets that represent the most recent years, that account for interannual variability (for indicators where interannual variability is high), and are updated frequently can ensure that the screening tool is as current as possible, although some temporal misalignment between indicators is inevitable. Box 5.2 provides a practical example of the potential affects of the frequency of dataset updating on data uncertainty.

IDENTIFYING AND ANALYZING THE DATASETS TO BE USED

Different datasets available for measuring a particular indicator may use different methodological approaches in their development. In some cases, there may be a

BOX 5.2

U.S. Census and American Community Survey Data in CEJST

Socioeconomic data used as burden indicators in CEJST are based on 5-year estimates derived from the American Community Survey (ACS). These estimates include uncertainties that the tool quantifies through margins of error (MOE). Previous sociodemographic research on the ACS illustrates how the 5-year average estimates can have substantial MOEs at subcounty scales (e.g., census tracts) when compared to the decennial U.S. Census data (Bazuin and Fraser, 2013; Folch et al., 2016). To mitigate such measurement errors, researchers have suggested the removal of all census units with small population counts or the use of census units where MOEs of the point estimate are less than half of the point-estimate value (Folch et al., 2016). Since CEJST uses census tracts as the basic analytical unit, it is important to keep in mind that the MOE magnitude generally is considerable for tract-level ACS estimates, particularly in rural areas with lower populations. If the percentage of people living at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty line (i.e., the definition of “low income” in CEJST) in two tracts are compared, the differences between the two may be similar but smaller than the corresponding MOEs. This would seem to indicate no significant difference in the percentage of low-income people in the two tracts, suggesting that the percentiles for the two tracts should be identical and not different. This would be the conclusion if only the ACS point estimates of the percentages of people in the tract at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty line were utilized and the MOE values were not considered. This could result in potentially erroneous estimation of low-income burdens and, consequently, misclassification of community disadvantage. In the case of CEJST, burden calculations rely on data from the ACS 5-year estimates that do not acknowledge or account for uncertainty in the ACS variables. Other national public health and environmental health data products (e.g., National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [NHANES]) add 95th confidence intervals to the percentiles, an approach that allows incorporation of uncertainty in the raw data and communicates the uncertainty in the percentile values themselves that are linked to the raw data.

“gold standard” methodological approach, but in other cases, multiple approaches may be used and accepted by researchers and practitioners without one approach standing out as most closely representing truth. Many of the same principles for selecting and evaluating indicators also apply to selecting and evaluating datasets used to represent those indicators. Often, datasets that are based on observations are considered of higher quality when compared with estimation approaches. However, when observations are sparse in space or time, combining observations with estimation techniques (e.g., statistical models, process-based models) can provide spatially complete datasets that are informed by observations. Another important consideration is how well the dataset performs upon evaluation against observed quantities (statistical evaluation metrics

such as correlation coefficients, bias, and uncertainty). However, multiple datasets can have similar performance against observations while differing in magnitude and spatial distribution of the estimated quantities. The degree to which the dataset is adopted and used by federal agencies or the scientific community, or accepted by communities, can provide additional confidence in the dataset’s validity.

Analyzing and comparing different available datasets can reveal insights as to the limitations and implications of the use of the datasets—for example, determining if certain communities are more likely to be missed when using one dataset over another (see Box 5.3). Analyzing indicators and datasets can also ensure that, barring specific stakeholder concerns about representation, the indicators and datasets selected for inclusion are independent of each other, reflect the state of the science, and are trusted by technical experts and validated by lived-experience data of community members. See Chapter 6 for details on integrating multiple indicators and possible correlation between indicators.

Rigorously documenting the process for selecting and analyzing datasets can enhance transparency and highlight areas for further research. Results such as spatial maps, tracts in the top percentile, correlations with other relevant indicators and datasets, and evaluation statistics are important information for agencies, community groups, researchers, and other users with which to understand the rationale and implications of each indicator and dataset selection. The process for obtaining those results, including community engagement, is also relevant for enhancing transparency.

BOX 5.3

Selecting Datasets to Represent Indicators: PM2.5 Example

The PM2.5 indicator illustrates the challenge of selecting among multiple high-quality datasets that could be used to define the indicator. CEJST currently uses a 12-km gridded annual average PM2.5 concentration dataset that was developed by EPA and is also used within EJScreen. A recent comparison of the CEJST dataset with two more highly spatially resolved datasets from the scientific community found that the three datasets differ substantially regarding which tracts are most overburdened within individual urban areas (Carter et al., 2023). As a result, the study identified 335 tracts (representing ~1.5 million people) as disadvantaged (>65th percentile for poverty and >90th percentile PM2.5) using both high-resolution datasets but not the 12-km dataset used by CEJST, and 695 tracts (representing ~2.7 million people) as disadvantaged in the 12-km dataset but not the high-resolution datasets. This analysis underscores the challenge of identifying and selecting a single dataset to represent the indicators in the tool. Each dataset also carries uncertainties, which are discussed in Chapter 6 of this report.

CATEGORIES OF BURDEN IN CEJST

CEJST includes eight categories of what CEQ labels burdens—climate change, energy, health, housing, legacy pollution, transportation, water and wastewater, and workforce development. These categories align and expand on the priorities in President Biden’s Executive Order (E.O.) 14008 (although E.O. 14008 does not include health in its list of priorities; EOP, 2021). The categories are used in combination with relevant socioeconomic burdens (low income and high school education) to identify DACs. Although the rationale for the E.O. 14008 categories is unstated, the committee did not identify any obvious omissions, given the committee’s understanding of the objectives of the tool. The rationale for the inclusion or exclusion of specific indicators within each burden category in CEJST is not provided in the CEJST technical documentation, either in terms of why certain indicators but not others were included or in terms of the categorization of individual indicators in specific burden categories (e.g., the inclusion of PM2.5, which has many emission sources, in the energy burden category).

Each of the eight burden categories includes multiple indicators—a different number of indicators for each category—as outlined in Table 5.2. The tool identifies a community as disadvantaged if it is in a census tract that is (1) at or above the threshold for one or more indicators in any burden category and (2) at or above the threshold for an associated socioeconomic burden. For example, the climate change burden category includes five indicators. If a tract meets a threshold for one or more of these indicators, as well as the threshold for the low-income indicator, it is identified as disadvantaged. Census tracts that do not meet any burden thresholds but are at or above the 50th percentile for low income and surrounded by other census tracts that do meet the thresholds for disadvantage are also designated as DACs. Finally, all land within the boundaries of federally recognized Tribes is designated as disadvantaged.

Using this formulation, neither the number of burden categories nor the groupings of indicators within them affect the tool’s binary identification of disadvantaged status. However, the tool does have some implicit weighting reflected in the number of indicators included in each burden category. Burden categories with more indicators (e.g., climate, housing, and legacy pollution, each with five indicators) have more chances of triggering the disadvantage identification compared with burden categories with fewer indicators (e.g., energy and water and wastewater, each with only two indicators). Burden categories with more indicators are thus implicitly weighted more heavily than burden categories with fewer indicators. As a result, some categories could be overrepresented and others underrepresented in the tool. In addition, indicator groupings could become important in future iterations of the tool, especially if integration approaches for assessing cumulative impacts are implemented (discussed further in Chapter 6). In addition, community engagement, validation, and transparency in selecting and including burden categories and indicators can help evaluate how well the tool captures burdens that align with the lived experience of communities (discussed further in Chapter 7; Larsen, Gunnarsson-Östling, and Westholm, 2011).

TABLE 5.2 CEJST Burden Categories and Indicators

| Burden Categories | Indicators | Socioeconomic Indicator |

|---|---|---|

| Climate change |

1. Expected agriculture loss rate ≥ 90th percentile OR |

Low income* |

|

2. Expected building loss rate ≥ 90th percentile OR |

||

|

3. Expected population loss rate ≥ 90th percentile OR |

||

|

4. Projected flood risk ≥ 90th percentile (NEW) OR |

||

|

5. Projected wildfire risk ≥ 90th percentile (NEW) |

||

| Energy |

1. Energy cost ≥ 90th percentile OR |

Low income* |

|

2. PM2.5 in the air ≥ 90th percentile |

||

| Health |

1. Asthma ≥ 90th percentile OR |

Low income* |

|

2. Diabetes ≥ 90th percentile OR |

||

|

3. Heart disease ≥ 90th percentile OR |

||

|

4. Low life expectancy ≥ 90th percentile |

||

| Housing |

1. Historic underinvestment = Yes (NEW) |

Low income* |

|

2. Housing cost ≥ 90th percentile OR |

||

|

3. Lack of green space ≥ 90th percentile (NEW) OR |

||

|

4. Lack of indoor plumbing ≥ 90th percentile (NEW) OR |

||

|

5. Lead paint ≥ 90th percentile |

||

| Legacy pollution |

1. Abandoned mine land present = Yes (NEW) OR |

Low income* |

|

2. Formerly used defense site present = Yes (NEW) OR |

||

|

3. Proximity to hazardous waste facilities ≥ 90th percentile OR |

||

|

4. Proximity to Superfund or National Priorities List (NPL) sites ≥ 90th percentile OR |

||

|

5. Proximity to Risk Management Plan sites ≥ 90th percentile |

||

| Transportation |

1. Diesel particulate matter ≥ 90th percentile OR |

Low income* |

|

2. Transportation barriers ≥ 90th percentile (NEW) OR |

||

|

3. Traffic proximity and volume ≥ 90th percentile |

||

| Water and wastewater |

1. Underground storage tanks and releases ≥ 90th percentile (NEW) OR |

Low income* |

|

2. Wastewater discharge ≥ 90th percentile |

||

| Workforce development |

1. Linguistic isolation ≥ 90th percentile OR 2. Low median income ≥ 90th percentile OR 3. Poverty ≥ 90th percentile OR 4. Unemployment ≥ 90th percentile |

Less than high school education > 10% |

NOTE: * = percent of a census tract’s population in households where household income is at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty level, not including students enrolled in higher education.

SOURCE: Adapted from CEQ, 2022a.

The ensuing subsections expound upon each of the CEJST burden categories with a description of the indicators included in each burden;6 additional indicators that could be incorporated to meet CEJST’s objectives; current data availability, quality, and spatial and temporal resolutions for those indicators; and key data gaps. The text is intended to provide a realistic and practical description of data that could be included in the tool in consideration of those data that meet CEJST’s criteria described above. It is not intended to be a comprehensive review of all available indicators and datasets but rather highlights those that the committee considered to be a high priority for relevance based on subject-matter expertise, information gathering (including a public workshop; NASEM, 2023a), and which datasets meet all technical and practical characteristics for inclusion. Potential changes to the burden categories themselves are not addressed; as previously mentioned, categorizations of the indicators only affect the identification of disadvantage to the extent that the number of indicators in each burden category differs, although these categorizations could become important in future iterations of the tool, particularly if an integration approach such as a composite indicator is used.

Climate Change

CEJST includes five indicators in the climate change burden category: expected agriculture loss rate, expected building loss rate, expected population loss rate, projected flood risk, and projected wildfire risk. Agricultural and building loss rate from those natural hazards are economic terms (agricultural value at risk and building value at risk), while population loss rate reports the number of fatalities and injuries caused by the hazard. Flood and wildfire risks are considered within these agricultural, building, and population loss indicators, and are also considered as individual indicators.

Expected agricultural, building, and population loss rates come from FEMA’s National Risk Index (NRI)7 and cover all U.S. states, the District of Columbia, and the five U.S. territories (American Samoa, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands). The NRI includes 18 different natural hazards. CEJST considers 14 of those 18 hazards to be climate-related: avalanche, coastal flooding, cold wave, drought, hail, heat wave, hurricane, ice storm, landslide, riverine flooding, strong wind, tornado, wildfire, and winter weather. A limitation of these composite indicators is that the risk of specific natural hazards varies from location to location. Thus, even when a census tract is identified as being disadvantaged based on a high agricultural, building, or population loss rate due to natural hazards, it is not clear which natural hazard(s) is driving the risk to be high in a specific location.

Projected flood and wildfire risk data originate from the nonprofit First Street Foundation.8 The flood risk dataset (at the census-tract level) represents how many properties are at risk of floods occurring in the next 30 years from tides, rain, and riverine and

___________________

6 Information about which datasets were used for the CEJST indicators can be found in the CEJST Technical Support Documentation (CEQ, 2022a).

7 See https://hazards.fema.gov/nri/ (accessed February 12, 2024).

8 See https://firststreet.org/ (accessed February 15, 2024).

storm surges, without considering property values. The wildfire risk dataset (with a 30-meter resolution) represents the chance over 30 years of property in the area burning, considering factors such as fire fuels, weather, human influence, and fire movement. Both indicators are specific to property damage and are insufficient to capture broader impacts on health and livelihoods. For example, floods are associated with population displacement and mental health impacts, disruption in access to medication and health care, water quality issues, and other impacts. Wildfires are similarly associated with population displacement, mental health impacts, and disruption in access to medication and health care, and can cause deterioration of air quality at regional and continental scales, with respiratory, cardiovascular, and other health impacts.

The indicators used within CEJST to address climate change cover multiple relevant community hazards, but they provide a limited view of which communities are most vulnerable to the many impacts of climate change and through which pathways. Community resilience to climate change includes, for example, the impacts of increased heat, disease vectors, mental health, air pollution from sources other than wildfires, water quality, extreme weather events, and drought (USGCRP, 2023). Each of these can have serious downstream consequences for human health and livelihoods. For example, extreme weather events can lead to coastal inundation and inland flooding, leading to contamination of waterways with sewage, animal waste, and chemicals (Cushing et al., 2023b; Erickson et al., 2019), as well as the risk of chemical disasters at industrial facilities (Anenberg and Kalman, 2019). Many climate damage pathways have not yet been well quantified or detailed through qualitative data, and inclusion within CEJST is challenged by the lack of availability of nationwide, high-resolution datasets for each pathway.

Heat, however, is a climate damage pathway for which datasets appropriate for CEJST already exist. Heat is the leading cause of weather-related mortality in the United States over the last several decades (Luber and McGeehin, 2008) and may be under-reported (Weinberger et al., 2020). Unless additional measures to protect public health are taken, the frequency and intensity of extreme heat events will increase mortality and morbidity in the future (Shindell et al., 2020). Studies using surface temperature and other heat-related measures have found that heat is inequitably distributed within U.S. urban areas (Mitchell and Chakraborty, 2019; Renteria et al., 2022) and is related to historical redlining and marginalization (Hoffman Shandas, and Pendleton, 2020; Hsu et al., 2021). While surface temperature studies often do not account for humidity, which can modulate the heterogeneity of heat exposure within cities (Chakraborty, T. C., et al., 2022; Keith, Meerow, and Wagner, 2019), communities of color and with lower income levels disproportionately experience moist heat (Chakraborty et al., 2023) as well as heat vulnerability (Manware et al., 2022). Residential air-conditioning prevalence, which can mitigate the health effects of heat exposure, is also inequitable across 115 metropolitan areas (Romitti et al., 2022). Additionally, outdoor workers in many industries across the country, such as agriculture and construction, will still be exposed to extreme heat, even in areas with a high prevalence of residential air-conditioning (Licker, Dahl, and Abatzoglou, 2022).

Future climate risks are another set of potential indicators for which there are datasets appropriate for CEJST. As the geographic area and population affected by climate

change are expected to grow, the communities most affected by climate change in the future may be different than those most affected today. Two indicators used within CEJST consider future changes: flood risk and wildfire risk. However, as mentioned above, they capture a limited portion of human health damages. Potentially important indicators to represent community risks from climate change include future changes in extreme temperature, future changes in climate-sensitive natural disasters (only present-day natural disasters are currently included), and wildfire smoke. Further, the future projections for the datasets currently used within CEJST are limited to 30-year time horizons, though projections are available through 2100 from federal agencies. Rather than taking a deterministic approach for projecting future climate changes, which are inherently unknown and therefore uncertain, CEJST could consider a range of possible climate futures. Examples of other federal efforts that use a probabilistic approach considering multiple climate change scenarios include the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Climate Mapping for Resilience & Adaptation (CMRA) tool9 and its Fifth National Climate Assessment (USGCRP, 2023), and other efforts across the federal government, such as the U.S. EPA’s Climate Change Impacts and Risk Analysis (CIRA) project.10

The U.S. government provides a wealth of high-quality national data on climatic conditions, both historical data and future predictions and models. CEJST could take advantage of these extensive resources to provide a more comprehensive set of climate-relevant indicators that are also more transparent and consistent with datasets, tools, and reports from other parts of the federal government. For example, the USGCRP’s CMRA tool includes several future climate burden categories that are not included in CEJST: extreme heat, drought, and coastal inundation. The Localized Construct Analogs (LOCA) version 2 dataset,11 downscaled from the CMIP6 dataset, is available at a 6-km grid resolution and is used in the Fifth National Climate Assessment (USGCRP, 2023). CDC’s Environmental Public Health Tracking Network uses two different datasets. The North American Land Data Assimilation System (NLDAS-2)12 is available at approximately 14-km grid resolution, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) NCLIMGRID dataset13 has a 5-km grid resolution. Additional datasets available within the research community have higher spatial resolutions and could be more appropriate for this application (e.g., Funk et al., 2015, 2019, Verdin et al., 2020). The First Street Foundation, which produced the datasets used for the projected flood risk and projected wildfire risk datasets used in CEJST, also provides national-scale data for extreme heat in their Climate Risk dataset. The dataset is at 4-km spatial resolution and covers 2023 to 2053 using the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change CMIP5 RCP4.5 greenhouse gas scenario. Available climate datasets are continually advancing

___________________

9 See https://resilience.climate.gov/ (accessed January 29, 2024).

10 See https://www.epa.gov/cira (accessed January 29, 2024).

11 See LOCA’s website to view details on the dataset: https://loca.ucsd.edu/. (accessed February 15, 2024).

12 See https://ldas.gsfc.nasa.gov/nldas/v2/forcing (accessed February 15, 2024).

13 See https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/metadata/landing-page/bin/iso?id=gov.noaa.ncdc:C00332 (accessed February 25, 2024).

to higher spatial resolutions and improved accuracy, and reviewing the available datasets regularly would ensure that the datasets used reflect the state of the science.

In the coming years, the USGCRP is expected to develop a new program to provide climate services, including to the rest of the federal government and to the public. Climate services are defined by the Office of Science and Technology Policy as “scientifically-based, usable information and products that enhance knowledge and understanding about the impacts of climate change on potential decisions and actions” (Fast Track Action Committee on Climate Services, 2023). As USGCRP develops its approach for providing climate services, CEQ could be a client for these data, and CEQ and USGCRP could work together to ensure that the climate services data are responsive to the needs of CEJST for future incorporation into the tool.

Potentially important indicators and datasets that could be considered for inclusion in future versions of CEJST are heat and future climate risks. Compared with CEJST’s current approach, which uses datasets that assume a single climate projection and 30-year time horizon, using a probabilistic approach and longer time horizons can provide a more holistic view of potential future climate risks. Working with other federal agencies, such as NOAA and USGCRP, to produce and access relevant climate data can ensure that the datasets used in the tool are robust and consistent with other federal efforts.

Energy

The energy burden category includes two indicators: energy cost and PM2.5. Energy cost is measured as the average proportion of annual household income spent on energy. Energy cost data come from the Department of Energy’s Low-Income Energy Affordability Data (LEAD) Tool14 and is provided at the census-tract level for all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico (excluding Pacific Island territories). LEAD Tool estimates of energy cost are modeled from the U.S. Census Bureau’s ACS 2020 Public Use Microdata Samples and U.S. Census housing data from the 2016 5-year ACS.15

PM2.5 is a commonly used metric for air pollution. The PM2.5 data are represented as annual average concentrations for 2019, derived from a model-monitor fusion approach implemented by EPA. The data are also used in the EPA’s EJScreen tool and are available for all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico, but not other island territories. PM2.5 is a criterion air pollutant that is regulated by the EPA through annual average and 24-hour average National Ambient Air Quality Standards.16 PM2.5 itself is a mixture of chemical components that exist in both solid and liquid form. A small fraction of PM2.5 is emitted directly (“primary PM2.5“), and a larger fraction is formed in the atmosphere through chemical interactions (“secondary PM2.5“), although the specific sources, chemical composition, and fraction that is primary versus secondary

___________________

14 See https://www.energy.gov/scep/slsc/low-income-energy-affordability-data-lead-tool (accessed February 15, 2024).

15 See https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs (accessed February 15, 2024).

16 For more on National Ambient Air Quality Standards, see https://www.epa.gov/criteria-air-pollutants/naaqs-table (accessed February 15, 2024).

depend on geographic location, nearby and upwind emissions, and atmospheric conditions. CEJST documentation does not explain why PM2.5 is listed under the Energy burden category, given that PM2.5 originates from a variety of sources beyond energy generation. Other major emission source sectors for PM2.5 and precursor emissions include transportation, agriculture, industry, wildfires, and dust. A portion of PM2.5, diesel PM, is included in the Transportation burden category in CEJST. As stated previously, the committee does not focus on indicator placement under specific burden categories because the indicator groupings are irrelevant to the identification of DACs in the CEJST’s current formulation.

The rationale for including PM2.5 but not other major air pollutants (e.g., ozone, nitrogen dioxide) is not discussed in CEJST technical support documentation (CEQ, 2022a), therefore preventing the committee from understanding this decision and underscoring the need for clear and thorough documentation. While PM2.5 is the largest contributor to the burden of disease from ambient air pollution, ambient ozone is another criterion air pollutant linked with premature mortality that is of interest to community members (NASEM, 2023a). National-scale, spatially complete datasets on ozone concentrations are available. For example, EPA’s EJScreen tool includes ozone, using the “peak concentration metric” of the annual mean of the 10 highest maximum daily 8-hour concentrations. The ozone concentration data are from the same model-monitor fusion approach used for the PM2.5 dataset that is currently included in CEJST. Nitrogen dioxide (NO2) is another important air pollutant that contributes to ozone formation and is associated with poor health outcomes. As NO2 is often considered a marker of traffic-related air pollution, this pollutant is discussed in the Transportation burden category section below.

The major sources of PM2.5 and the spatial distribution of PM2.5 are in a period of flux due to a variety of factors. Stringent emission standards are bringing emissions down within the energy generation (Henneman et al., 2023) and transportation sectors (Anenberg and Kalman, 2019), while climate change is fueling longer, more intense wildfire smoke seasons (Burke et al., 2021; O’Dell et al., 2019) and more airborne soil dust (Achakulwisut, Mickley, and Anenberg, 2018), leading to high interannual variability and, potentially, stagnation of PM2.5 declines (Wei et al., 2023). The high interannual variability in PM2.5 driven by wildfire severity can change spatial and demographic patterns of exposure. It may be important to use multiyear average PM2.5 concentrations to account for this interannual variability. In addition to annual (or multiyear) averages, including an indicator for poor air quality days can capture wildfire smoke episodes.

The dataset used for PM2.5 in CEJST has approximately 12-km grid resolution and is too coarse to capture intraurban concentration gradients that might lead to exposure disparities. In addition, newer datasets from the scientific community have advanced beyond the approach used to develop the CEJST dataset by incorporating satellite measurements of aerosol optical depth (e.g., van Donkelaar et al., 2021) and, in some cases, many other data types in a machine learning process (e.g., Amini et al., 2023). These more advanced and higher-resolution exposure assessment approaches (~1-km grid resolution) are increasingly used within the scientific community, including for air pollution epidemiology (Di et al., 2019). As previously mentioned in Box

5.3, a comparison of the CEJST dataset with two higher-resolution datasets from the scientific community found that the three datasets differ substantially regarding which tracts are most overburdened within individual urban areas, though nationwide PM2.5 disparities were more consistent between the datasets (Carter et al., 2023). This analysis underscores the importance of analyzing datasets and evaluating them both technically and with community partners to identify the most appropriate dataset to represent the indicator. As satellite-based and community-collected datasets will improve over time with hourly atmospheric composition data from geostationary satellites, such as the TEMPO instrument launched by NASA in April 2023, PM2.5 concentrations derived using satellite data as an input are likely to play an increasingly important role in tracking air pollution and associated disparities across federal governmental activities.

Considering other indicators of air pollution beyond annual average PM2.5—including ozone and poor air quality days—would capture additional spatial and temporal patterns of exposure to health-harmful air pollution, especially as these pollutants worsen under climate change. The energy burden index used within the DOE’s Energy Justice Mapping Tool provides an opportunity to include additional aspects of disadvantage, including the percent of households not connected to gas or electric grids and the number and average duration of power outages.

Other indicators that could be considered in the Energy burden category include those used by the Department of Energy (DOE) in its own Energy Justice Mapping Tool—Disadvantaged Communities Reporter.17 These include indicators for the percentage of households that use a fuel other than grid-connected gas or electricity, or solar energy as their main heat source (data from DOE LEAD); average duration of power outage events (in minutes) that occurred for all census tracts in each county from 2017 to 2020 (data from DOE Office of Electricity); number of power outage events that occurred for all census tracts in each county from 2017 to 2020 (data from DOE Office of Electricity); and transportation costs as percentage of income for a typical household in the region (data from Center for Neighborhood Technology).

Health

The health burden category currently includes four indicators: asthma, diabetes, heart disease, and life expectancy at birth. Asthma, diabetes (among people ages 18 years and older), and heart disease (among people ages 18 years and older) data come from the CDC’s PLACES: Local Data for Better Health project (PLACES) data18 for 2016–2019. PLACES provides model-based, population-level analysis and community estimates of health measures down to the census tract across all 50 states and the District of Columbia (but not U.S. territories, i.e., American Samoa, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands). Life expectancy data come from the CDC’s U.S. Small-Area Life Expectancy Estimates Project

___________________

17 See https://energyjustice.egs.anl.gov/ (accessed January 10, 2024).

18 See https://www.cdc.gov/places/index.html (accessed February 15, 2024).

(USALEEP)19 from 2010 to 2015. The USALEEP project produced estimates for most U.S. census tracts. The rationale for selecting the four measures currently included in the tool is not reflected in the CEJST Technical Documentation (CEQ, 2022a).

E.O. 14008 did not specifically include health burden as a driving factor for focused investments under the Justice40 Initiative. However, poor health makes communities more vulnerable to the health outcomes associated with climate change, pollution, and other CEJST burden categories. Currently, health data and exposure data are separate burden categories in CEJST and are not integrated. Burden disparities can be amplified when considering health risks associated with exposures (as opposed to considering only the exposure itself) since exposure data alone do not adequately indicate who is adversely affected by that exposure and to what degree. For example, many studies have found that air pollution is inequitably distributed, with communities of color experiencing higher exposure levels compared with the national average or the white population. When these higher exposures for communities of color are combined with information on vulnerability to those exposures—driven by higher rates of preexisting disease, lack of access to high-quality health care, and less ability to take action to reduce exposure—disparities are further amplified (e.g., Kerr et al., 2023; Southerland et al., 2021). The converse of adverse effects from simultaneous disproportionate exposure and vulnerability is that the communities with both high exposure and vulnerability are those who benefit most from reducing exposure and vulnerability—the goal of the Justice40 program. While this report does not address methods for determining which communities will benefit from government programs under the Justice40 Initiative and by how much, the report does discuss how consideration of cumulative impacts could be incorporated into CEJST in Chapter 6.

As of December 2023, PLACES has estimates of 36 health measures—13 for health outcomes, 9 for preventive services use, 4 for chronic disease–related health risk behaviors, 7 for disabilities, and 3 for health status.20 Among those 36, two stand out for their potential to provide unique information compared with the other health outcomes currently included in CEJST. These are cancer among adults 18 years and older and access to health insurance among those 18–64 years. Other health outcomes from PLACES may be less relevant (e.g., all teeth lost, arthritis) or overlap with those currently included in CEJST in terms of biological systems (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke, coronary heart disease) and spatial patterns. Cancer is both relevant—it is affected by climate change, legacy pollution, and other indicators in CEJST (Winstead, 2023)—and is unlikely to be spatially aligned with the other CEJST indicators. The lack of health insurance among adults ages 18–64 years is a measure within the PLACES Prevention category. According to the latest PLACES data based on 2020 and 2021 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data,21 approximately 11.7 percent of U.S. residents did not have health insurance. However, since lack of health

___________________

19 See USALEEP data at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/usaleep/usaleep.html (accessed February 15, 2024).

20 See the full list of PLACES health measures at https://www.cdc.gov/places/measure-definitions/health-outcomes/index.html (accessed February 15, 2024).

21 See https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/index.html (accessed February 15, 2024).

insurance varies substantially with citizenship status, ethnicity, income, geography, age, and race (Keisler-Starkey, Bunch, and Lindstrom, 2023), analyzing and understanding spatial correlations with other CEJST socioeconomic indicators would be informative.

It is not clear from technical documentation whether the asthma prevalence dataset used in CEJST includes data on individuals of all ages or only adults. The CEJST Technical Support Document (CEQ, 2022a) does not mention age for the asthma indicator, but the PLACES documentation indicates that the asthma prevalence data is for 18 years of age and older. Pediatric asthma prevalence has been shown to be inequitably distributed in major cities across the United States (Kane, 2022; Roberts et al., 2006). In addition, while some of the indicators in CEJST raise the risk of asthma onset, asthma exacerbation may be more greatly affected by differences in the degree of asthma management in different neighborhoods. To date, data on pediatric asthma prevalence and asthma exacerbation are not available at the tract level nationally, but such datasets may be developed in the coming years.

Access to healthcare would be another appropriate indicator since rural communities tend to have far fewer doctors, specialists, and hospitals in their neighborhoods than urban communities. Systemic discrimination within the healthcare system also leads to disparities in healthcare and health outcomes (Williams and Rucker, 2000). The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) produces nationally available data on the geography of hospital and nonhospital healthcare facilities,22 as well as clinicians, down to individual street addresses.23

In terms of data quality, it is important to note that the PLACES data are modeled using small-area estimation, a multilevel statistical modeling technique, and do not represent observational data. As such, these data are subject to uncertainties but are not restricted for privacy protections as administrative data often are. PLACES provides 95 percent confidence intervals of modeled estimates generated using a Monte Carlo simulation. In addition, the CDC cautions users against using these estimates for program or policy evaluations because the small-area model cannot detect the effects of local interventions.24 The annual estimates provide a sufficient temporal resolution, and higher-temporal-resolution (e.g., daily, monthly, seasonal) data are not necessary for CEJST’s purposes.

Documentation of the rationale for including the four indicators included in CEJST would provide useful information for end users of the tool and other tool developers and enhance tool transparency. Including additional indicators, such as cancer and lack of health insurance, that are distinct from the four already included can capture additional communities who are experiencing disproportionate health burdens. Although no such data currently exist to the committee’s knowledge, considering pediatric asthma onset

___________________

22 See CMS’s Provider of Services File—Hospital & Non-Hospital Facilities at https://data.cms.gov/provider-characteristics/hospitals-and-other-facilities/provider-of-services-file-hospital-non-hospital-facilities (accessed February 15, 2024).

23 See CMS’s National Downloadable File at https://data.cms.gov/provider-data/dataset/mj5m-pzi6 (accessed February 15, 2024).

24 Read CDC’s full description of its PLACES 2023 data release at https://data.cdc.gov/500-Cities-Places/PLACES-Local-Data-for-Better-Health-County-Data-20/swc5-untb/about_data (accessed February 16, 2024).

and asthma exacerbation, two outcomes that are highly heterogeneous between neighborhoods and broader geographic areas, would complement the adult asthma prevalence indicator that is currently used in CEJST. Integrating health burdens with other burden categories and indicators to identify DACs could more closely align with the goal of the Justice40 program to benefit underserved communities.

Housing

The housing burden category includes five indicators: experienced historic underinvestment, housing cost, lack of green space, lack of indoor plumbing, and lead paint. Historic underinvestment is represented by redlining maps created by the federal government’s Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) between 1935 and 1940.25 The boundaries in the HOLC maps were converted to census tracts by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition. Within CEJST, census tracts that have National Community Reinvestment Coalition scores of 3.25 or more out of 4 are considered to have experienced historic underinvestment. This indicator is only available for tracts that were included in the original HOLC maps in certain metro areas across the United States. Housing cost is represented by the share of households that are earning less than 80 percent of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD’s) Area Median Family Income and are spending more than 30 percent of their income on housing costs. Data are from the Comprehensive Housing Affordability Strategy dataset from 2014 to 2018 and are available for all U.S. states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. This dataset is also used for the lack of indoor plumbing indicator. Lack of green space is represented by the share of land with developed surfaces covered with artificial materials such as concrete or pavement, excluding cropland used for agricultural purposes. Data are from the Multi-Resolution Land Characteristics Consortium’s Percent Developed Imperviousness dataset for 201926 and are available for all contiguous U.S. states and the District of Columbia. The lead paint indicator is represented by the share of homes built before 1960, which, according to the CEJST documentation, indicates potential lead paint exposures (CEQ, 2022a). Tracts with median home values above the 90th percentile are excluded as they are considered less likely to face health risks from lead paint exposure. Data on lead paint are from the ACS for 2015 to 2019 and cover all U.S. states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. The tool does not currently include other important exposures to lead, including lead in drinking water (see Box 5.4) and childhood exposure to contaminated soil, which remains a legacy pollutant due to historic use of leaded gasoline and industrial activity, such as battery incineration (Laidlaw et al., 2017; Laidlaw, Mielke, and Filippelli, 2023; Zartarian et al., 2023).

___________________

25 See Chapter 2, Box 2.1 for more on redlining.

26 See https://www.mrlc.gov/data/nlcd-2019-percent-developed-imperviousness-conus (accessed February 15, 2024).

BOX 5.4

Lead in Drinking Water

An infamous recent drinking water emergency was the result of a poorly maintained drinking water infrastructure—the lead-contaminated public drinking water in Flint, Michigan. Water was contaminated as a result of a change in the source water, increased corrosion of leaded pipes, and chronic inadequacies in maintenance, monitoring, and reporting (Denchak, 2018; MCRC, 2017; Mohai, 2018). Residents had adverse health effects and were advised not to drink the water. Flint is not alone. Other studies show that chronic lead exposure from old, leaded water service lines across the country (Olson and Stubblefield, 2021), as well as breakdowns in urban public water systems resulting in chronic boil water alerts, have disproportionate impacts on lower-income children and communities of color (Greenfield, 2023; Kim, M. et al., 2023). For at least the last decade, researchers have found that poor and, more often, minority communities were more consistently and disproportionately exposed to drinking water contamination (Balazs and Ray, 2014; Balazs et al., 2011; Berberian et al., 2023; Konisky, Reenock, and Conley, 2021; Martinez-Morata et al., 2022; Pullen Fedinick, Taylor, and Roberts, 2019; Ravalli et al., 2022; Schaider et al., 2019; Stillo and MacDonald Gibson, 2017).

Although lead drinking water pipes in community water systems are the primary source of lead in drinking water (EPA, 2016b), there is relatively little data on leaded pipes at a national scale. EPA was mandated by America’s Water Infrastructure Act of 2018 to evaluate and report on the cost of replacing lead service lines in its quadrennial Drinking Water Infrastructure Needs Survey and Assessment (DWINSA). In 2021, EPA collected service-line-material information for the seventh DWINSA. That report estimated that there were 9.2 million lead service lines across the country, primarily concentrated in the eastern half of the country, and especially in states in the South, Midwest, and Northeast. However, these data are only available at the state level.a EPA is implementing the Lead and Copper Rule Improvements (LCRI), which require water systems to identify and make public the locations of lead service lines,b and issued Guidance for Developing and Maintaining a Service Line Inventory in 2022. The number of lead water lines will remain until there are complete inventories of service lines (EPA, 2023c).

__________________

a See EPA’s 7th Drinking Water Infrastructure Needs Survey and Assessment dashboard at https://www.epa.gov/dwsrf/epas-7th-drinking-water-infrastructure-needs-survey-and-assessment.

b See proposed Lead and Copper Rule Improvements (LCRI) at https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/proposed-lead-and-copper-rule-improvements (accessed February 26, 2024).

Legacy Pollution

The Legacy Pollution burden category includes five indicators: abandoned mine land, formerly used defense sites, proximity to hazardous waste facilities, proximity to Superfund sites (National Priorities List),27 and proximity to Risk Management Plan (RMP) facilities. The abandoned mine land indicator is represented by the presence of an abandoned mine left by legacy coal mining operations, identified using data from the Abandoned Mine Land Inventory System (e-AMLIS) from the Department of the Interior for 2017. The data cover all U.S. states and the District of Columbia. Formerly used defense sites are from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for 2019 and cover all U.S. states and the District of Columbia. Proximity to hazardous waste facilities, Superfund sites, and RMP facilities use data from various EPA databases (as compiled by EPA’s EJScreen) for 2020 for all U.S. states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico, and all datasets use a 5-km boundary around facility sites as a measure of proximity. These three proximity indicators consider the number of facilities in each indicator category within 5 km divided by the distance in kilometers.

The EPA released a memorandum, “Strengthening Environmental Justice Through Criminal Enforcement” (EPA, 2021), on the need to strengthen tools for detecting environmental crimes28 in overburdened communities. Information from the EPA’s criminal enforcement program might be useful in strengthening EJ tools, including CEQ tools. EPA’s ECHO (Enforcement and Compliance History Online)29 database provides data on enforcement actions for all EPA-regulated facilities, including permit data, inspection/compliance evaluation dates and findings, violations of environmental regulations, enforcement actions, and penalties assessed. However, these data are not easily accessible or interpretable because the violation codes are unclear and often nonspecific, and the specific circumstances underpinning the rationale for violations are often not made public. Other information may be needed to represent the pollution activities.

Transportation

The transportation burden category includes three indicators: diesel particulate matter (PM) exposure, transportation barriers, and traffic proximity and volume. The dataset used for the diesel PM indicator comes from the EPA EJScreen tool and, according to the CEJST documentation (CEQ, 2022a), is originally sourced from the National Air Toxics Assessment from 2014 (EJScreen documentation indicates the source as the 2017 Air Toxics Update).30 It is available for all 50 states, the District of Columbia,

___________________

27 Learn more about the National Priorities List (NPL) on EPA’s website at https://www.epa.gov/superfund/superfund-national-priorities-list-npl (accessed February 16, 2024).

28 Environmental crimes are carried out by “individuals and corporations that have violated laws designed to protect the environment, worker safety, and animal welfare,” according to the Environmental Crimes Section of the U.S. Department of Justice: https://www.justice.gov/enrd/environmental-crimes-section/ (accessed February 26, 2024).

29 See https://echo.epa.gov/ (accessed February 16, 2024).

30 See EPA Air Toxics Screening Assessment, 2017 Results: https://www.epa.gov/AirToxScreen/2017-airtoxscreen-assessment-results (accessed February 16, 2024).

and Puerto Rico. Transportation barriers represent the average relative cost and time spent on transportation relative to all other tracts and only applies to census tracts with populations greater than 20 people. The source of the transportation barriers dataset is the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) Transportation Access Disadvantage category utilized in the DOT Equitable Transportation Community Explorer (ETCE).31 Traffic proximity and volume are defined as the number of vehicles (average annual daily traffic) at major roads within 500 meters, divided by distance in meters. The data are sourced from EPA’s EJScreen tool and are for the year 2017 and all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico.

While the committee was not tasked with evaluating the DOT ETCE, participants of the committee’s public workshop did suggest that transportation metrics be considered for use in CEJST (NASEM, 2023a). The DOT ETCE User Guide suggests that CEJST be used to identify DACs and then the DOT tool be used to better understand the transportation disadvantage component of CEJST and the ETCE’s Transportation Insecurity component—which could ensure that DOT’s investments address transportation-related causes of disadvantage.32 Since DOT is using additional indicators beyond those included in CEJST, the committee does not suggest additional transportation access and volume indicators. However, there are two areas that might be considered by CEQ: (1) a closer proxy for transportation-related air pollution than diesel PM, and (2) noise pollution.

There are several limitations with the diesel PM metric when characterizing the impact of transportation on air quality, including that vehicles using other fuels besides diesel are also polluting and diesel PM is difficult to observe on a nationwide basis, requiring reliance on estimation approaches. Compared with diesel PM, NO2 may be a more appropriate indicator of traffic-related air pollution and is more directly observable using space-based Earth-observing satellites. NO2 is linked with respiratory effects, asthma development, and premature mortality (HEI, 2022) and reacts with other chemicals in the atmosphere to form both PM2.5 and ozone, the two largest contributors to the burden of disease from air pollution in the United States. NO2 is more spatially heterogeneous and inequitably distributed than PM2.5 (Kerr, Goldberg, and Anenberg, 2021; Kerr et al., 2023) since NO2 has a shorter atmospheric lifetime (i.e., hours compared with days) and more limited influence from regional pollution sources (e.g., agriculture, wildfire smoke, dust). Heavy-duty vehicles are a leading source of NO2 in urban areas of the United States and contribute to disproportionate NO2 exposure among communities of color and with lower income and educational attainment levels (Demetillo et al., 2021; Kerr, Goldberg, and Anenberg, 2021).

Since the diesel PM dataset used in CEJST is derived through modeling rather than observation, the time needed to update these datasets introduces a time lag of several years. Furthermore, the spatial pattern of truck traffic and resulting diesel PM2.5

___________________

31 See DOT’s ETCE and its user guide at https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/0920984aa80a4362b8778d779b090723 (accessed February 12, 2024).

32 See DOT’s webpage on the Justice40 Initiative at https://www.transportation.gov/equity-Justice40 (accessed February 16, 2024).

emissions and concentrations are changing rapidly: warehousing associated with the booming e-commerce industry is increasing truck trips, truck idling, noise, and traffic-related air pollution in some places, which are increasingly nearer to population centers (e.g., Jaller and Pahwa, 2020). Additionally, oil and gas development results in heavy truck traffic (e.g., Adgate, Goldstein, and McKenzie, 2014) in new locations, such as the Permian Basin in Western Texas and the Bakken field in North Dakota. Neither of these rapidly evolving industries would show up in a diesel PM2.5 dataset that is several years old. However, these changes are captured by satellite-based NO2 datasets. A more observational dataset, such as satellite NO2, could be a valuable metric for CEQ to consider in future CEJST versions, especially as new geostationary satellites, such as TEMPO launched by NASA in 2023,33 will produce hourly measurements over the United States in the coming years.

It may also be useful to have an indicator for assessing transportation-related noise pollution, which is associated with cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (Münzel, Sørensen, and Daiber, 2021), mental health outcomes (Gong et al., 2022), and other health effects. Transportation-related noise data are available from the DOT Bureau of Transportation Statistics’ National Transportation Noise Map and are available for the United States at the tract level (Seto and Huang, 2023). The estimates include noise levels related to aviation, roadway, and rail traffic. These data may meet the criteria for inclusion in CEJST if CEQ and community partners consider them to be relevant for the purposes of CEJST.

Water and Wastewater

The water and wastewater burden category includes two indicators: underground storage tanks (USTs) and releases and wastewater discharge. Both USTs and releases and wastewater discharge indicators use datasets compiled by EPA’s EJScreen tool and are available for all U.S. states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. The UST indicator is drawn from the EPA’s UST Finder for 2021,34 which includes any UST and “any underground piping connected to the tank that has at least 10 percent of its combined volume underground” (EPA, 2024). Federal UST regulations apply only to UST systems above specific thresholds storing either petroleum (e.g., gasoline, diesel, fuel oil) or certain hazardous substances (e.g., ammonia, asbestos, benzene, chromium). More than 99 percent of federally regulated USTs contain petroleum, and most of those are owned or managed by service stations and convenience stores, or by vehicle fleet service operators and local governments. The greatest potential hazard from USTs is the leakage of hazardous substances into the surrounding soil and contamination of groundwater. UST releases are the most common source of groundwater contamination; petroleum is the most common contaminant (EPA, 2023a). This is notable given that nearly one-half of all Americans get their drinking water from groundwater (EPA, 2024). Underground storage tanks and releases are represented by a weighted formula of the

___________________

33 See https://science.nasa.gov/mission/tempo/ (accessed March 8, 2024).

34 See https://www.epa.gov/ust/ust-finder (accessed February 26, 2024).

density of leaking underground storage tanks and the number of all active underground storage tanks within 1,500 feet of the census tract boundaries.

The wastewater discharge indicator utilizes information from the EPA’s Discharge Monitoring Report (DMR) Loading Tool35 along with the EPA’s Risk-Screening Environmental Indicators (RSEI) model36 to estimate the relative risk to a census-block group from exposure to pollutants in downstream water bodies (EPA, 2023b). The DMR Loading Tool includes data on industrial and municipal point-source wastewater dischargers that are subject to a subset of permits under the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES),37 as well as wastewater pollutant discharge data from EPA’s Toxic Release Inventory (TRI). Wastewater discharge is represented by the RSEI-modeled toxic concentrations at stream segments within 500 meters, divided by the distance in kilometers. The data are for 2020. Both USTs and releases and wastewater discharge indicators use datasets compiled by EPA’s EJScreen tool and are available for all U.S. states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico.