Progress and Priorities in Ocean Drilling: In Search of Earth's Past and Future (2024)

Chapter: 2 A Primer on Scientific Ocean Drilling

2

A Primer on Scientific Ocean Drilling

This chapter provides background on the scientific ocean drilling program important for understanding the research priorities and infrastructure needs described for a future program. First, key terms used throughout the report are defined, particularly those important for understanding the difference between platforms and/or mechanisms through which scientific ocean drilling has been conducted over the past decades and may be conducted in the future. This is followed by an overview of the scientific drilling management structure and process for planning and conducting expeditions. The chapter then presents a brief history of ocean drilling, including major accomplishments.

TERMINOLOGY AND KEY CONCEPTS

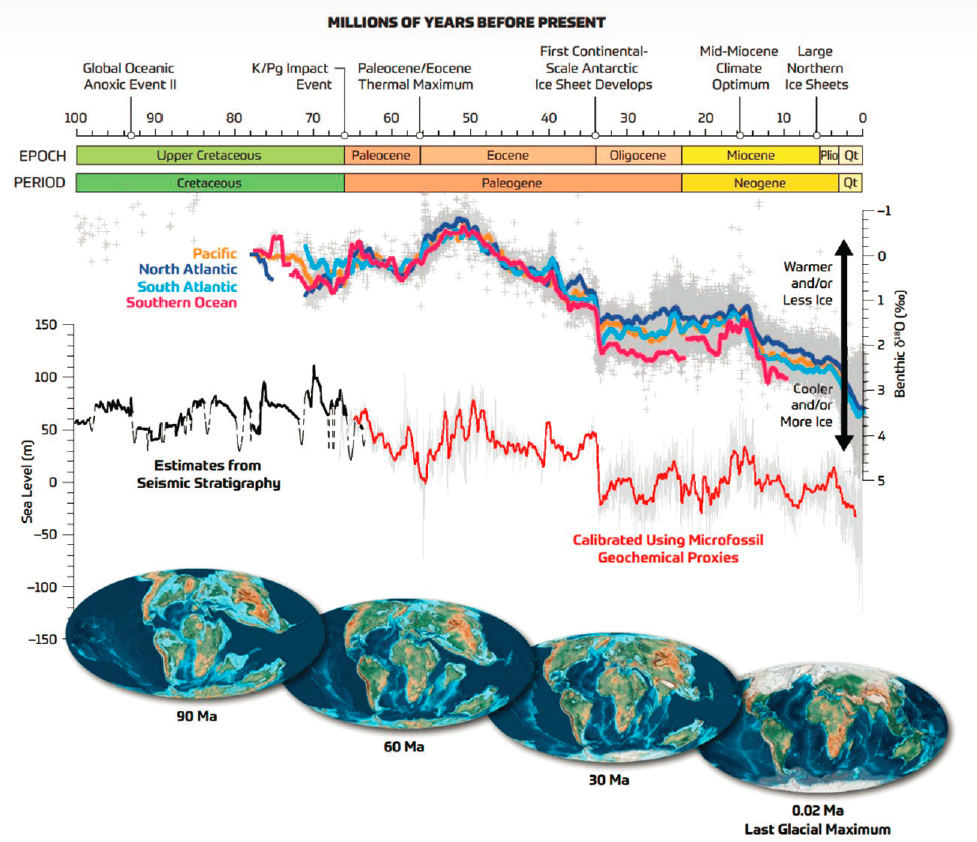

For decades, scientific ocean drilling pioneered global-scale interdisciplinary research below the seafloor of the world’s ocean. As distinctions between shallow subseafloor coring and deeper drilling-enabled core recovery are important to the capabilities and accomplishments of scientific ocean drilling, definitions and other report-relevant terms are provided in Box 2.1. A geological timeline that spans most of the time periods accessible via scientific ocean drilling is provided (Figure 2.1), along with fundamental data derived from scientific ocean drilling on past global temperatures, sea levels, and global tectonic configurations.

Eight unifying, guiding principles have emerged from the scientific philosophies and practices over the history of the scientific ocean drilling program and has been identified by the U.S. and international scientific ocean drilling program communities (Koppers and Coggon, 2020) as important for any and all drilling programs:

- Open access to samples and data. Free and open access to samples in core repositories and data in online repositories has been a hallmark of the program. Open access ensures that scientists of all career stages can participate in the program. In practice, samples and data are subject to a 1-year moratorium postexpedition, during which time samples and data are available only to the expedition team, including shore-based participants. After 1 year, all the data are made publicly accessible by the scientists who collected them, and others from around the world can submit requests for core samples to any of the three scientific ocean drilling core repositories (located in Texas, Germany, and Japan) for use in research and teaching and training (IODP, n.d.e).1

___________________

1 See https://www.iodp.org/resources/core-repositories. Also, samples from a collaborative sea-to-land coring project are stored in a repository in New Jersey.

SOURCE: Koppers and Coggon, 2020. Illustration by Geo Prose based on Cramer et al., 2009.

BOX 2.1

Definitions

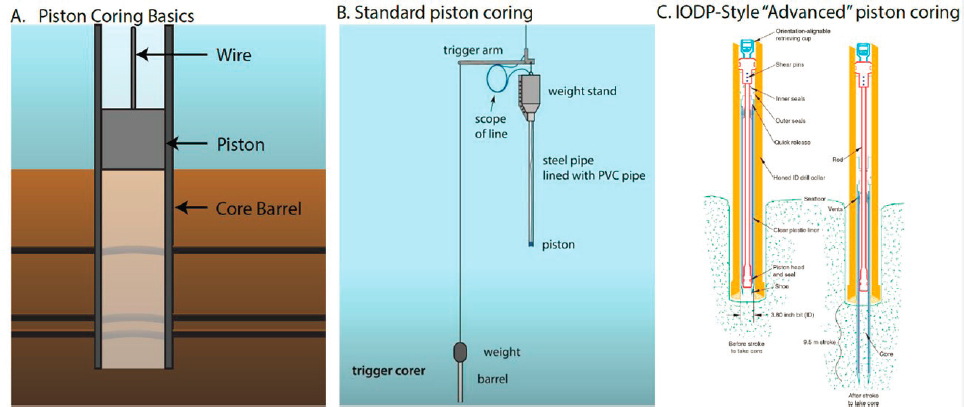

(B) Standard piston corer design representing those used in the academic research fleet. SOURCE: David Reinert, CEOAS Communications.

(C) Advanced piston corer design representing those used in scientific ocean drilling.

SOURCE: Baldauf et al., 2002.

Standard piston corer: A long, heavy tube with a piston inside that is lowered over the side of a vessel and uses gravity to drive a corer into the seafloor to extract samples of soft (i.e., unlithified) sediment and mud (Figure 2.2A, B). It is unsuitable for recovering hard sediment or rock. The standard piston corer is 3–18 m in length, which is therefore the maximum subseafloor depth for core recovery. In theory, there is no water depth limit for any piston corer.a The U.S. Academic Research Fleet (ARF), coordinated by the U.S. University-National Oceanographic Laboratory System (UNOLS), uses this type of coring tool on board its vessels. The JOIDES Resolution and other International Ocean Discovery Program platforms are not configured to use this corer.

Giant piston corers: Longer and heavier than standard piston corers; also used to core soft sediment and mud and unsuitable for recovering hard sediment or rock. The giant piston corer is 18–60 m in length, with the maximum length only available through a commercial purveyor (e.g., Ocean Scientific International Ltd [OSIL]). Currently, no vessels in the ARF can handle systems of this size.b The maximum subseafloor depth for giant piston coring with the current ARF is 40 m; however this limit is approachable only in a few environments based on UNOLS Safety Committee guidelines and cores up to 30-m subseafloor depth is more the norm. A long core system designed for deployment on R/V Knorr in the early 2000s had an effective maximum length of 50 m, but this vessel (and coring system) is no longer available in the ARF. Giant piston corers are also known as jumbo piston corers.

Drilling-enabled advanced piston corers: Part of a combined drilling–coring system that enables much deeper (Figure 2.2C) and more continuous core recovery than standard or giant piston corers. This apparatus requires using a drillship, and, given current ARF capabilities, is the only means of coring deeper than 30-m subseafloor. In drilling-enabled coring, sections of pipe are connected, extending from a hole (the moonpool) in the drilling vessel down into the seafloor. At the base of the pipe is a drilling bit (drilling

tool). An advanced piston corer (APC) core barrel is lowered by a wire inside the drill pipe to the bottom of the pipe. Pump pressure is applied to the drill pipe, which hydraulically advances the inner core barrel 9.5 m into soft sediment and mud. The core barrel, containing the core, is retrieved back to the vessel by the wire. After core retrieval, more pipe is added, the drilling bit and bottom-hole assembly are advanced another 9.5 m, and the process is repeated downward continuously until the sediment becomes too hard (or rock is encountered), at which point other drilling bits and coring tools are used (e.g., rotary coring) (IODP, n.d.a). Significant engineering and technological advances have improved the rate of coring, the fraction of mud recovered per 9.5-m advance (see Box 3.1 in Chapter 3), and the fidelity of the recovered material. Commonly, multiple holes are drilled from a single site, allowing for offset coring to recover the disturbed strata at core breaks, and in some cases allowing for a stratigraphic splice of piston-cored material extending many tens of meters into the seafloor. The maximum depth of drilling-enabled coring from the coring tools (e.g., APC, extended core barrel, rotary core barrel) used in scientific ocean drilling is 1,807-m subseafloor depth (IODP, n.d.d). Drilling-enabled coring can occur at a range of water depths. For example, the maximum water depth of drilling-enabled coring in scientific ocean drilling thus far is 5.7 km for the JOIDES Resolution, 8.0 km for mission-specific platforms, and 6.9 km for the Chikyu (IODP, n.d.d).

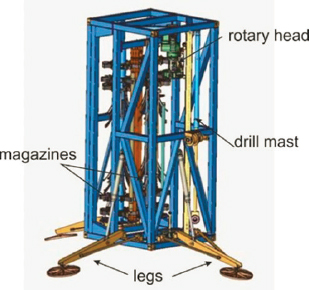

Seabed lander–based drilling systems: A robotic drilling rig that is deployed to the seafloor and operated remotely from a research vessel. Seabed corers (also called seabed landers or seafloor drilling rigs) can recover up to 260 m of subseafloor sediment and mud using a multihole operational approach to acquire a single representative sedimentary record. This involves drilling through shallower seafloor strata and shifting core operations to deeper seafloor strata to develop a composite section of 260 m over several holes. The diameter of the recovered core is significantly smaller than drilling from a drillship, and real-time monitoring of core recovery cannot occur. The functional water depth limit for seabed corers is approximately 4 km. An example of a seabed corer is the MeBo200 system developed by the Center for Marine Environmental Sciences (MARUM) at the University of Bremen, Germany (MARUM, n.d.b) (Figure 2.3). Currently there are no seabed corers in the ARF, and using them from the ARF will be possible only with some combination of significant financial investment in the infrastructure and capabilities of the vessels themselves; none could be deployed from any vessel in the fleet as it currently exists.

SOURCE: BAUER/MARUM, University of Bremen.

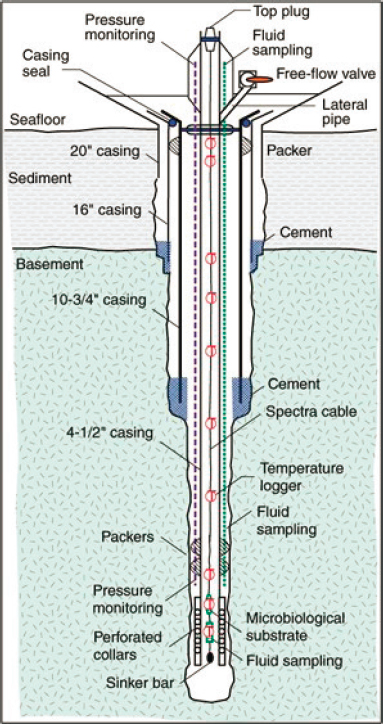

Borehole observatories: Sensors placed in an open borehole (a drilled hole, such as those drilled to recover subseafloor cores) for long-term monitoring of subseafloor temperature, pressure, strain, tilt, and seismicity, and for collecting borehole fluid samples. A seal is required to isolate the sensors from ocean bottom water; this seal is referred to as a Circulation Obviation Retrofit Kit (CORK) (Figure 2.4). Data collected through these observatories can be transmitted in real time using a subsea cable, or data can be retrieved via remotely operated vehicle from the top of the CORK. Because drilling is required to create the borehole, establishing new CORKs is not possible with the current ARF; they are installed using the JOIDES Resolution and other scientific ocean drilling vessels. Borehole observatories have also been installed using the MARUM MeBo seabed coring system for approximately 10 years (Kopf et al., 2015); however, these installations are limited to shallow subseafloor depths (~100 m).

SOURCE: U.S. Science Support Program, IODP, Fisher et al., 2011, fig. F2..

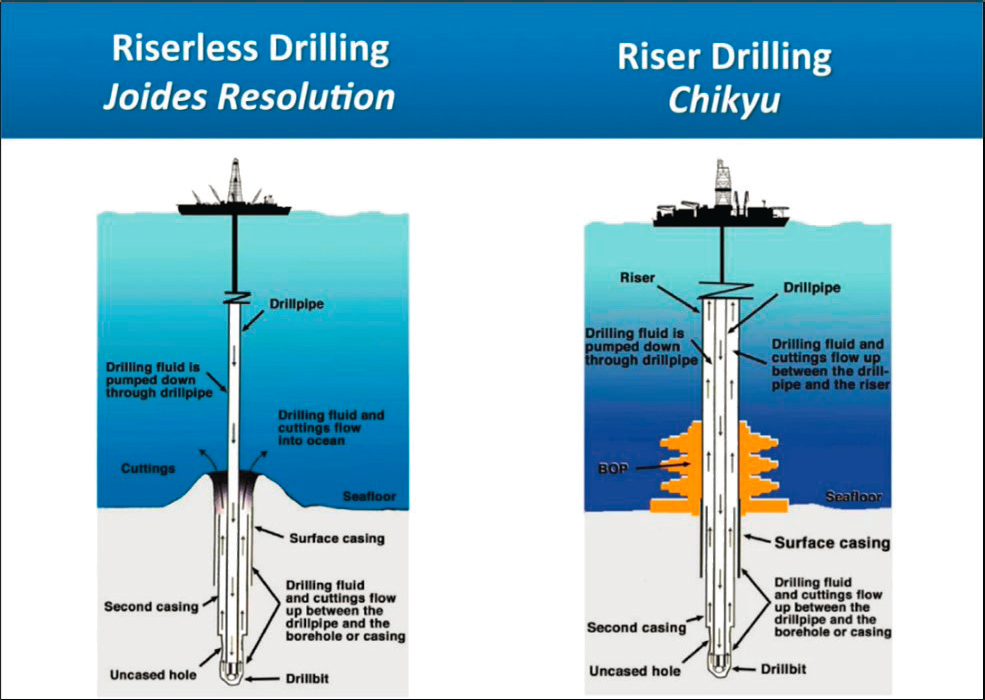

Riserless versus riser drilling: The JOIDES Resolution and its U.S. predecessor, the Glomar Challenger, are riserless drillships (Figure 2.5). In short, this means that the hole conditions are stabilized only by drilling mud that is open to the seafloor, and there are no “blowout preventers” or other means of preventing gaseous overpressure. It is the simplest system of drilling yet requires extensive safety planning to avoid hitting hydrocarbon reservoirs or other hazards. The Japanese drilling vessel Chikyu deploys riser drilling (Figure 2.5), in which the hole conditions are controlled by drilling mud within a wider pipe outside the drilling pipe, and thus the mud pressure can be controlled, stabilizing the borehole wall. A seafloor blowout preventer controls gas pressure and thus protects the drillship and the environment from gaseous overpressure. Typically, riser drillships can drill deeper than riserless drillships.

SOURCE: Modified from Taira et al., 2014. © JAMSTEC (Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology).

Sedimentation rates: The rate at which sediment is deposited onto the seafloor, typically in units of centimeters per thousand years (cm/kyr) or kilometers per million years (km/myr). Recovering sediments in an area with low sedimentation rates facilitates recovery of older sediment over a given depth, but with lower age resolution, compared with recovering sediments in an area with high sedimentation, which facilitates higher (i.e., more detailed) age resolution. For example, sediments in the anoxic Cariaco Basin accumulate as fast as 30 cm/kyr; therefore, sediment at 170 m beneath the seafloor is 700,000 years old. In contrast, sediment in the middle of the North Pacific Gyre accumulates at a rate of 1–3 mm/myr, so sediment ~25 m beneath the seafloor is 66 million years old. Paleoceanographers very carefully select the optimal region for addressing past variations in climate in terms of age recovered and resolution of the sedimentary layers. Thick, continuous sequences of sediment layers resulting from high sedimentation

rates over long time periods are ideal for palaeoceanographic investigations that require detailed sampling and analyses. Because of the relationship between sedimentation rates, subseafloor depth, and age, this often requires collecting sediment cores deep below the seafloor, and benefits from collecting sediment cores from multiple holes to ensure enough material is available for a wide range of analyses.

__________________

a For example, the Oregon State University Marine Rock and Sediment Sampling (MARSSAM) Group cored to 7+ km in a Puerto Rico trench using a standard piston core system from a synthetic line on the research vessel Neil Armstrong in early 2022, and the Japanese used a commercial (OSIL) system to core in the Challenger Deep the same year. The use of a synthetic/neutrally buoyant line is essential to avoid wire weight, or to have a sufficiently robust handling system to accommodate the weight of steel. Piston cores are fully mechanical systems, and if used with a trigger arm, there are no depth limitations in theory outside of weight on wire.

b Following the 2016 retirement of R/V Knorr, the handling systems (wire, winches, cranes, and A-frames) of even the largest vessels in the current ARF are not rated for the working loads associated with 60-m piston coring (e.g., OSIL Giant Piston Corer, see https://osil.com/product/jumbo-giant-piston-corer-18m-60m) and as such, unless existing vessels are modified and/or until new vessels come online, researchers are limited functionally to giant piston coring operations with at most 30- to 40-m recovery.

- Standardized measurements. The fidelity of scientific research and integrative data analytics depends on high-quality observations and comparable datasets. Standardized measurements and analytical techniques are long-standing practices among the drilling program’s technicians and scientists, whether data collection and analysis occur in the floating laboratories onboard the JOIDES Resolution or in specialized container laboratories on mission-specific platforms. Measurements and observations are also standardized in the laboratories that host the core repositories. International intercomparability demonstrated by the scientific ocean drilling program has been a model for other ocean science programs.

- Bottom-up proposal submissions and peer review. Science that is prioritized and ultimately accomplished emerges from visioning, multidisciplinary expertise, and collaboration of scientists from around the world. The bottom-up input occurs at multiple stages and levels in the program. Each phase of the program is guided by an overarching, framing document that describes long-term scientific priorities (e.g., currently this is the 2013–2023 IODP Science Plan), written and vetted by the scientific community (IODP, 2011). At the expedition level, science objectives result from a proposal process and are subject to multiple stages of peer review for scientific, environmental, and safety considerations. The structure is managed through U.S. and international scientific community panels and boards.

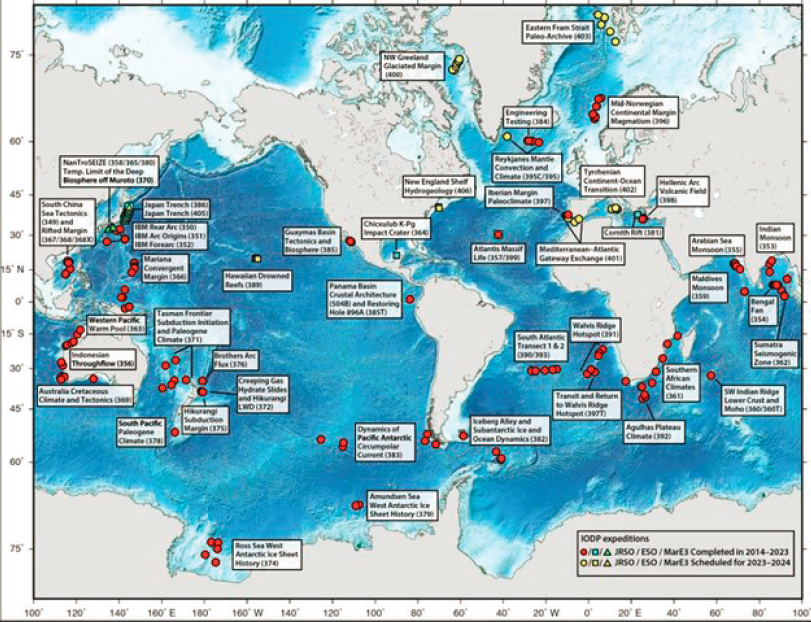

- Transparent regional planning. For cost and time efficiency, JOIDES Resolution expedition scheduling employs a regional planning approach, reducing transits between sequential expeditions (thus maximizing time for conducting research) (IODP, n.d.c). Transparent regional planning by facility boards allows proponent teams to develop proposals in support of strategically timed scientific ocean drilling in a particular area of the global ocean. For example, during the current phase of the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP-2), the JOIDES Resolution maximized time in the Indian Ocean, moved to the western Pacific, then to the South Atlantic, and is now operating in the North Atlantic (Figure 2.6).

SOURCE: JOIDES Resolution Science Operator.

- Safety and success through location characterization. Characterization and evaluation of the drilling location is essential for safety and scientific success prior to the approval of any subseafloor drilling expedition. Site surveys and examination of data collected by other oceanographic research vessels (e.g., the ARF) are fundamental steps of preexpedition planning; these include using seismic reflection and bathymetry data to characterize the seafloor and often gathering shallowly penetrating cores to test penetration. Site surveys ensure that subseafloor drilling data are interpreted in the appropriate scientific context. Careful site selection is critical because the sediments, rock, and other materials in the subseafloor vary from location to location, and achieving the scientific objectives of a given expedition often requires knowledge of site-specific characteristics. For example, seafloor sites with high sedimentation rates and long, continuous (undisturbed) records are essential to long-term, high-resolution analyses of past climate, ocean circulation, and ecosystems changes, and are therefore often targeted when drilling for cores and collecting samples.

- Regular assessments. Assessment of scientific progress and operational implementation is fundamental for any scientific program to adjust and advance as the goals of science and needs of society evolve. In scientific ocean drilling, regular operational assessments occur at multiple junctures and scales: the National Science Foundation (NSF) conducts annual site visits to the JOIDES Resolution Science Operator facility and receives annual evaluation reports completed by co-chief scientists (IODP, n.d.f). Additionally, postexpedition evaluations are completed on the scientific operations by science party members.

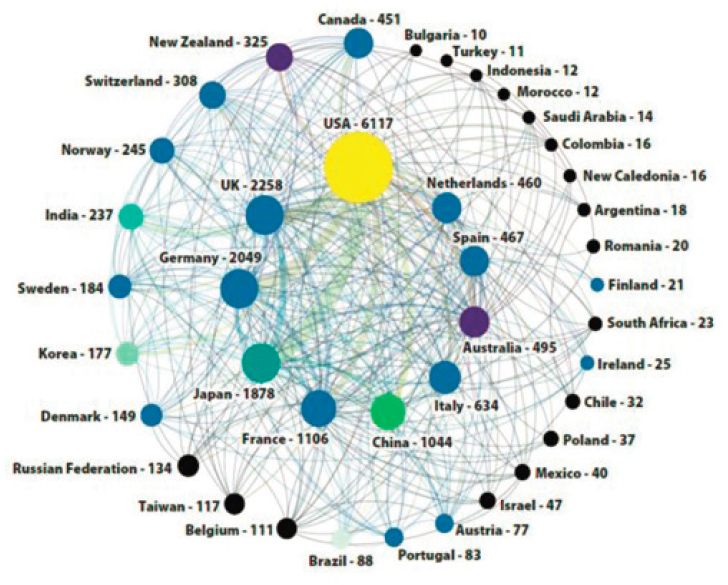

- International collaboration. The scientific ocean drilling community is internationally integrated (Figure 2.7), featuring 21 member countries in the current phase of the scientific ocean drilling program and collaborators in many other countries. Expeditions are always made up of international science teams, with the number of berths allotted dependent on each country’s financial contributions to the program. Scientists are often eager to continue the international collaborations that took place onboard once onshore and when analyzing samples.

- Workforce diversity and inclusion. The scientific ocean drilling community values a diverse and inclusive scientific and technological workforce. With time, the program and the workforce culture has evolved to be more inclusive (Box 2.2). At present, there is typically equity in the number of women and men in expedition science teams. On average, early-career scientists and graduate students comprise two-thirds of expedition science team members and are mentored by senior scientists. Cultural and multinational diversity exists throughout, as a direct result of the scientific ocean drilling program (and each expedition) being structured as an international program. Removing barriers and promoting opportunities to further broaden participation is an ongoing effort and varies by country.

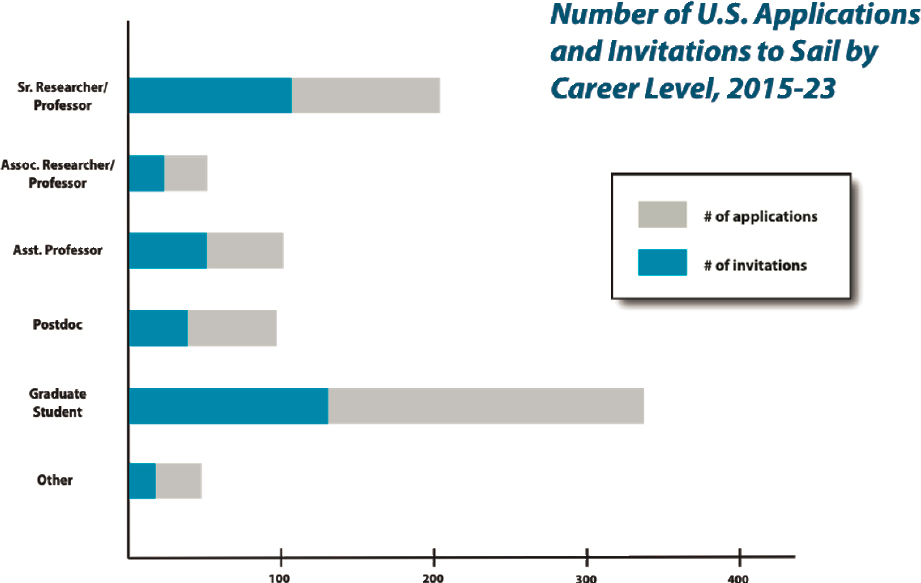

SOURCE: U.S. Science Support Program, 2022.

BOX 2.2

Science Supported by a Diverse Workforce

During the current phase of scientific ocean drilling, the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP-2), U.S. staffing demonstrates some progress in broadening of participation. Importantly, the program has not tracked key metrics and dimensions of diversity, and additional work is clearly warranted in the future. Nevertheless, the program made impactful strides toward gender balance and in promoting opportunities for students and early-career researchers. By 2020, 34 percent of the science parties were women, compared with only 12 percent in the earliest days of scientific ocean drilling.a And since 2020, there are more U.S. women sailing on expeditions than men (Table 2.1), with one-half of the expeditions having women chief scientists. Additionally, opportunities for students and early-career scientists on expeditions have expanded during IODP-2 (Table 2.2). As shown in Figure 2.8, U.S.-operated expeditions include as many graduate students as senior researchers. Approximately one-third of all U.S. expedition science party (i.e., team) participants are graduate students, and mentoring is an integral, highly valued aspect of the program. These demographics speak to the critical importance of a U.S.-led scientific ocean drilling program in creating, training, and sustaining a diverse and inclusive oceanographic workforce.

| Gender | Number (%) of Applications | Number (%) of Participants (Final Science Party) |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 401 (47.7) | 165 (45.4) |

| Female | 434 (51.7) | 197 (54.3) |

| Nonbinary | 5 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) |

NOTE: IODP-2 = International Ocean Discovery Program.

SOURCE: U.S. Science Support Program, IODP.

TABLE 2.2 U.S. IODP Science Parties by Career Level, 2015–2023

| Career Level | Number of Participants | % of Participants |

|---|---|---|

| Senior Researcher or Professor | 115 | 31.5 |

| Early- or Mid-Career | 129 | 35.3 |

| Graduate Student | 121 | 33.2 |

NOTE: IODP-2 = International Ocean Discovery Program.

SOURCE: U.S. Science Support Program, IODP.

__________________

a Original data from Koppers and Coggon, 2020; updated data obtained from a presentation to the committee on August 2, 2023.

SOURCE: U.S. Science Support Program, IODP.

IODP-2 MANAGEMENT STRUCTURE

The current phase of the drilling program (IODP-2) depends on facilities funded by three vessel (i.e., platform) providers: NSF, the European Consortium for Ocean Research Drilling (ECORD), and Japan, with financial contributions from additional partner agencies (Australia-New Zealand Consortium, China, and India). Each platform (JOIDES Resolution, mission-specific platforms [MSPs], and Chikyu; see Table 1.1 in Chapter 1) is operated independently by the respective country or consortia, and operational decisions are guided by facility boards. The IODP-2 platforms are operated by science operators under a contract or other agreement with platform providers.2 Science operators plan expedition logistics and manage all science and vessel operations. High-level, annual meetings serve as a venue for international discussions among funders, vessel operators, facility boards, and program member nations. Scientific activities are managed by IODP-2 program member offices.

Overview of Expedition Science Operations

The number of expeditions per year varies among the three scientific ocean drilling platform providers and depends largely on operational costs, available funding, and time requirements for vessel mobilization and demobilization. The U.S.-operated JOIDES Resolution, which is dedicated entirely to scientific ocean drilling, typically operates four to five 2-month IODP expeditions per year. Consequently, the number of subseafloor holes drilled, and cores recovered, to support scientific research is much greater for the JOIDES Resolution than the other platforms (see Table 1.1 in Chapter 1). The drilling vessel has been the major factor in enabling U.S. leadership in the program. Although MSP expeditions provide versatile options for achieving science objectives, they do not occur as frequently as the scientific community has requested; typically, less than one expedition per year occurs (see Table 1.1 in Chapter 1). Prior to the 2023 MSP expedition (Exp 389 Hawaiian Drowned Reefs, August–October 2023), the most recent MSP expedition was in 2021. The Japan-owned and -operated Chikyu depends on commercial use to secure the operational funds to support scientific ocean drilling expeditions. Chikyu is also used for other drilling work as designated by the Japanese government and is not available to scientists during these times. The most recent IODP-2 expedition on Chikyu was in 2018. Chikyu has never conducted scientific ocean drilling outside of Japanese waters and is not expected to in the future.

Regardless of which platform is used for a scientific ocean drilling program expedition, and regardless of the specific science objectives of an expedition, there is a generalized workflow for preexpedition planning, the at-sea expedition, and postexpedition activities (Table 2.3). This workflow, based on decades of experience, is enabled by global science support offices that include operational, technical, curatorial, and publications staff.

Science conducted at sea depends on laboratories available on the vessel. Onboard JOIDES Resolution and Chikyu, highly instrumented shipboard laboratories exist for analysis of physical properties, downhole logging (i.e., petrophysics), micropaleontology, sediment description, petrology/structural geology, paleomagnetism, organic and inorganic geochemistry, and microbiology. Scientists conducting projects on an MSP may utilize container laboratories onboard the vessel and/or conduct only limited at-sea measurements of ephemeral properties, waiting to conduct the primary analysis of core descriptions and measurements at shore-based laboratories associated with a repository. The Bremen Core Repository (MARUM, n.d.a) and associated laboratories at the Center for Marine Environmental Sciences (i.e., MARUM)3 at the University of Bremen in Germany meet this purpose for many MSP expeditions. In contrast, the U.S.-based Gulf Coast Repository in College Station, Texas, has limited shore-based laboratory infrastructure (e.g., XRF core scanner), as most U.S.-based laboratories are shipboard (i.e., on the JOIDES Resolution).4

___________________

2 Through funding from NSF, the JOIDES Resolution Science Operator (JRSO) at Texas A&M University manages science operations of the JOIDES Resolution. The vessel is operated by Siem Offshore AS and is owned by Overseas Drilling Ltd. The JOIDES Resolution Facility Board provides guidance to JRSO.

3 See https://www.marum.de/en/Infrastructure/Lab-infrastructure-at-MARUM.html.

TABLE 2.3 Generalized Pre- Through Postexpedition Time Frames and Activities

| Preexpedition (3–10 years) | Expedition at Sea (~2 months) | Postexpedition (1–5 years) |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

HISTORY OF OCEAN DRILLING

Inspired by Project Mohole in the 1950s–1960s, scientific ocean drilling commenced operations in 1968, utilizing a dedicated drillship, the Glomar Challenger, as the Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP) (see Figure 1.1 in Chapter 1). The DSDP was a U.S.-only program during its earliest phases, with international collaborations and partnerships evolving so that it became truly global in scope—in the science conducted, the science teams involved, and the operational and management structures. With the capability to core and recover sediments and basalts at abyssal water depths (>6 km), the Glomar Challenger provided key data for constraining the age of the seafloor, which was primary evidence of plate tectonic theory. In addition, the recovery of overlying sediments, and subsequent analyses, yielded critical insight into Earth’s history, including past changes in climate and the ocean environment over the last 150 million years. These early scientific milestones were facilitated in large part by the development of innovative drilling technologies, such as reentry cones (to replace worn core bits) and hydraulic piston coring (to recover undisturbed sequences of unconsolidated seafloor sediments that were required for constructing high-fidelity records of the past; Box 2.1). Recognizing the unique potential of the Challenger, in 1975, five additional nations partnered with the United States to support DSDP operations through 1983, when the Challenger was officially retired. By that time, the DSDP had completed 96 expeditions, having visited 624 drill sites, the findings from which revolutionized the field of Earth sciences by (1) resolving questions on the formation of Earth’s continents and ocean, (2) characterizing the general composition and distribution of marine sediments globally, and (3) providing the first detailed records of ocean history (climate, circulation, chemistry, and biota) that would serve as a foundation for all future research. Textbooks in all the fundamental STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) fields had to be rewritten because of groundbreaking discoveries enabled by scientific ocean drilling.

Ocean Drilling Program

Motivated by the outcomes of the DSDP, the international Earth sciences community embarked on a new venture, the Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) (18 partners initially), which began operations in 1985 with the drillship JOIDES Resolution. A larger vessel equipped with advanced dynamic positioning and coring capabilities, including active/passive heave compensation, the JOIDES Resolution could operate over a greater expanse of the ocean, including both shallow coastal zones and subpolar seas. Moreover, the JOIDES Resolution was capable of reentering previously drilled holes and installing the first subseafloor monitoring systems. Perhaps most important, with a more powerful drive system and advanced coring capabilities, core recovery rates and percentages of success in both hard and soft rock formations were significantly improved. With the insight into Earth processes gained from the DSDP, objectives of the new program were wider ranging, spanning issues from the evolution of the crust to climate to biogeochemical cycles. Although the scientific programming was initially guided by selected proposals, in order to address new initiatives and coordinate drilling expeditions, several program planning groups were created based on specific, high-priority, emerging themes (e.g., gas hydrates, extreme climates, the Arctic’s role in global change, hydrogeology, seismogenic zones, deep biosphere). With guidance from the program planning groups and the JOIDES Resolution’s expanded coring capabilities, 110 expeditions were completed across much of the ocean through 2004, the findings of which transformed understanding of key aspects of Earth’s dynamics and evolution.

Integrated Ocean Drilling Program

In 2003, the ODP transitioned to the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program (IODP-1), which—in addition to a refurbished JOIDES Resolution—would begin to conduct scientific ocean drilling on other platforms. This program initially included partners Japan and ECORD, yet would eventually grow to include 17 European nations, Canada, and eventually China and South Korea as associate members. ECORD would fund and manage the MSPs, while Japan would eventually build and manage the Chikyu, a riser-equipped platform (see Box 2.1) with ultradeep drilling capability. The IODP-1 was a 10-year program guided by an initial science plan (IODP, 2001) that defined a set of primary objectives grouped under the broad themes of climate change, geodynamics and deep Earth cycles, and the deep biosphere. With the flexibility of multiple platforms, coring operations were extended to regions inaccessible by the JOIDES Resolution, such as the Arctic or western Pacific subduction zones.

International Ocean Discovery Program

The current phase of scientific ocean drilling, the IODP-2, was launched in 2013, with the JOIDES Resolution as the primary platform, along with the Chikyu and MSPs. The program was initially supported by 21 nations, including the three major platform providers (United States, Japan, and ECORD), with additional financial contributions from five other partner agencies. The primary objectives of IODP-2 were organized into 14 “challenges” within four general themes: climate and ocean change, biosphere frontiers (i.e., subseafloor life), Earth connections and deep processes (i.e., ocean basin tectonics), and Earth in motion (i.e., geohazards) (IODP, 2011). While much of the research from this phase is still in progress, the findings of several early expeditions have already yielded significant contributions. Highlights of major accomplishments in the early years of scientific ocean drilling (DSDP and IODP-1) are described below; Chapter 3 provides an overview of accomplishments during the current phase of the program (IODP-2).

Major Accomplishments (~1969–2013)

Since the inception of DSDP, scientific ocean drilling expeditions and research have fundamentally transformed the understanding of the planet by revealing the critical features of Earth’s dynamic history, processes, and structure, including the solid Earth (i.e., upper mantle/crust), ocean, atmosphere, and ecosystems. The list of scientific ocean drilling–related achievements is extensive, represented in large part not only by the number

of publications, but also, until recently, by the sustained support for drilling by the international Earth sciences community. While summarizing the full list of achievements here is impossible, notable achievements have been grouped by themes.

Plate Tectonics and Mantle and Crustal Dynamics

Scientific ocean drilling first tested and confirmed the theory of plate tectonics, which revolutionized geological sciences in the late 20th century. This became the basis for a new generation of models on the evolution and dynamics of Earth’s crust and for understanding the origin of seismic activity and associated hazards along plate boundaries.

Notable advances resulting from scientific ocean drilling on crustal evolution and dynamics have been wide ranging. For example, the first samples of intact volcanic crust below thick layers of marine sediment were collected, revealing the complexity of crustal construction processes. Shallow sampling of large igneous provinces, which are vast outpourings of lava that have had a catastrophic influence on Earth’s climate and serve as windows into deeper Earth processes (e.g., mantle convection and hot spots), took place. The scientific understanding of continental breakup, faulting, rifting, and associated magmatism was revolutionized. Additionally, the first subseafloor borehole observatory systems were installed, generating long-term data records to further understand remote environments and processes. This advancement allowed for assessments of the types of materials that are recycled by subducting plates at convergent margins. Such data illuminated fault zone behavior and related tectonic processes at active plate boundaries where Earth’s largest earthquakes and tsunamis are generated. Data also revealed a subseafloor component to the ocean: large flows of fluids through virtually all parts of the seafloor, from midocean ridges to deep-sea trenches.

Climate Evolution and Forcing

Scientific ocean drilling extended the marine sedimentary record from the present day back to nearly 200 million years ago, allowing for reconstruction of long-term changes in global climate, including over the last 53 million years, when the planet transitioned from being hot and ice free (a greenhouse climate state) to cold and glaciated at both poles (an icehouse climate state; Figure 2.1). With advances in coring technology and strategies, much of this transition has been detailed at orbital-scale resolution (i.e., on the 10,000- to 100,000-year timescales for which changes in Earth’s tilt and orbit around the sun vary significantly), which is key to assessing rates of change, as well as the presence of the climate’s transient extremes. These core archives have also provided the basis for reconstructing the long-term evolution of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2). Together with advances in numerical models, these climatic reconstructions have provided the basis for testing climate theory and establishing the sensitivity of Earth’s climate (i.e., how Earth’s temperature responds) to changing greenhouse gas levels, including the nature and strength of climate feedbacks. All these findings have been vital to confirming the tipping points that triggered rapid climate change in the past.

Notable contributions from scientific ocean drilling pertaining to climate evolution include both regional and global insights. For example, extensive layers of salt deposits collected deep below the seafloor verified that the Mediterranean Sea dried out repeatedly in the past, and Cretaceous black shales recovered in all ocean basins provided direct evidence of ocean-wide anoxic episodes. Collected cores have also captured the variability of key components of the global hydroclimate, including the Indian and Southeast Asian monsoons and the north–south migration of the intertropical convergence zone over the last 20,000 years and beyond. Scientific ocean drilling cores have also revealed the increased strength and permanency of El Niño–Southern Oscillation conditions during warmer global climate intervals, such as during the early Pliocene (~3–5 million years ago [Ma]).

The combined use of paleomagnetic records, radiometric dating, and the layering of marine microfossils from scientific ocean drilling expeditions from around the world were used to refine the geological timescale. Most recently, the development of astrochronology based on Earth’s orbital rhythms as represented by sedimentary lithologic and geochemical cycles—documented with cores recovered by scientific ocean drilling combined with methods of absolute dating—have revolutionized paleoclimatology and paleoceanography. Moreover, these high-

fidelity records were also utilized by astronomers to test and refine their models of planetary motions over tens of millions of years (e.g., Varadi et al., 2003).

Scientific ocean drilling has contributed greatly to understanding the dynamics and interconnected nature of the cryosphere, atmosphere, biosphere, and ocean in Earth’s climate system. Cores from the high latitudes established the timing of the initiation of both Antarctic and Northern Hemisphere glaciations, the appearance of Arctic sea ice, and the role of greenhouse gas forcing. In particular, analyses of oxygen isotopes from microfossils in recovered cores demonstrated that the abrupt appearance of a massive ice sheet on East Antarctica approximately 34 Ma occurred after a long-term decline in atmospheric CO2. Similarly, scientific ocean drilling established major changes in the character of meridional overturning circulation during the recent glacial and interglacial cycles, which were linked in part to major discharges of glacial ice. Data from ocean drilling also provided evidence of large-scale reversals of deep circulation during extreme warming events (i.e., hyperthermals) in the Eocene and evidence of a poleward shift in the westerlies during the Pliocene warm period, thus supporting forecasts for similar shifts with future global warming.

Scientific ocean drilling allowed the construction of a 100-million-year (myr) history of global sea level change, which unveiled how quickly ice sheets can melt. Data from marine sediments, in combination with geophysical models, demonstrated how sea level rise (and fall) varied from region to region. Marine sediments have also provided the basis for reconstructing the pre–ice core history5 of atmospheric CO2 extending back into the Cretaceous (>100 Ma) and testing theories on the controlling mechanisms of climate change, including feedbacks. In particular, the discovery of short-lived carbon emission events verified a theory on the role of rock weathering as a major but slow process for sequestering CO2.

Life Evolution (Marine and Continental)

Sedimentary sample archives have been used to establish the long-term evolution and diversification of major marine zoo- and phytoplankton groups, and the influence of major climatic and environmental perturbations on marine ecosystems in extreme detail, including periods of volcanic outgassing and extreme warming, ocean acidification, and meteorite impacts.

Scientific ocean drilling has made several notable contributions on the study of life evolution. For example, work on sediment records provided the data necessary to document global patterns of plankton extinction and recovery from the Cretaceous–Paleogene impact 66 Ma, along with restoration of the marine biological pump revealed from marine sediment cores. The role of extreme warming on the rapid diversification of land mammals 56 Ma was revealed through the climate records found in cores from the deep sea. Moreover, records spanning the last 55 myr demonstrate how the efficacy of the ocean biological pump strengthened and diversity of plankton increased with long-term global cooling. In addition, scientific ocean drilling research documented the transition in the African climate relative to global cooling and the onset of Northern Hemisphere glaciation over the last 7.5 myr; the transition’s influence on the evolution of mammals—including hominids—was more tightly coupled to climate change (e.g., increasing aridity) based on the study of marine sediment records.

The Subseafloor Biosphere

Coring of the ocean crust enabled access to some of Earth’s most challenging and extreme environments, collecting data and samples of sediment, rock, fluids, and living organisms below the seafloor. A previously unknown microbial biome existing within the ocean sediments, as deep as 1.6 km below the seafloor, and within the volcanic carapace of the oceanic crust was discovered. This biome is surprisingly large and diverse, harboring new varieties of archaea, bacteria, eukarya, and viruses and varying in lithology, temperature, and redox conditions, and is likely contributing to geochemical reactions within the ocean crust, thus influencing ocean chemistry. Focus on the subseafloor, or deep biosphere, as a research theme of IODP has led to major understandings of the energetics of life, with particular emphasis on “extreme environments” (e.g., high and low temperatures, salinity

___________________

5 Ice cores can provide detailed records of climate change ~800,000 years ago.

extremes, extremely low energy levels). As such, significant portions of the postexpedition analysis in this field were supported by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, as the work correlates to astrobiology and the potential for non-Earth-based life.

CONCLUSION 2.1 Research supported by ocean drilling has fundamentally transformed the understanding of the planet, making key scientific contributions to knowledge of plate tectonics, the formation and destruction of ocean crust and how these processes generate geohazards, extreme greenhouse and icehouse climates ranging across 100 myr, and the response and recovery of the biosphere to major environmental perturbations. Additionally, such research has led to the discovery of a microbial ecosystem in the environment of ocean sediments, rocks, and fluids deep below the seafloor.

This page intentionally left blank.