Progress and Priorities in Ocean Drilling: In Search of Earth's Past and Future (2024)

Chapter: 3 High-Priority Science Areas: Progress and Future Needs

3

High-Priority Science Areas: Progress and Future Needs

Identifying and prioritizing critical research in ocean sciences that can be advanced only with scientific ocean drilling was an extensive process. The committee gathered community input on priorities, reviewed relevant reports that identify past priorities for scientific ocean drilling, examined progress made thus far, and identified unanswered questions that remain a priority. This chapter begins by evaluating progress made in scientific ocean drilling over the last decade with respect to priorities laid out in previous reports. It then presents the committee’s framing of research priorities, and within that framing, examines progress made over the last decade specific to advancing each of the priority areas and identifies future research needs. The chapter ends by classifying scientific ocean drilling research priorities in terms of vital and urgent research and discussing how those needs fall within the national agenda.

EVALUATING PROGRESS MADE OVER THE LAST DECADE

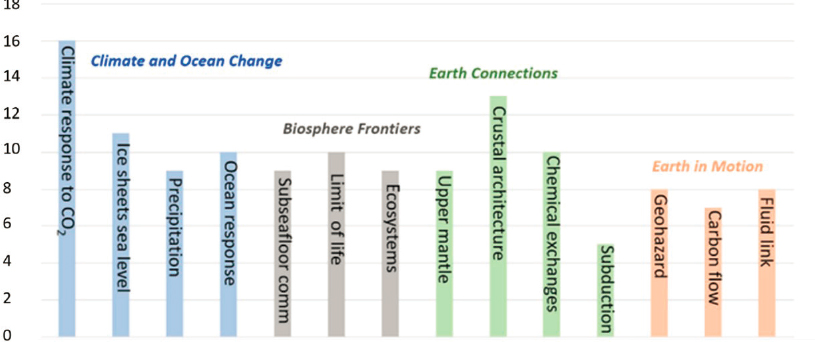

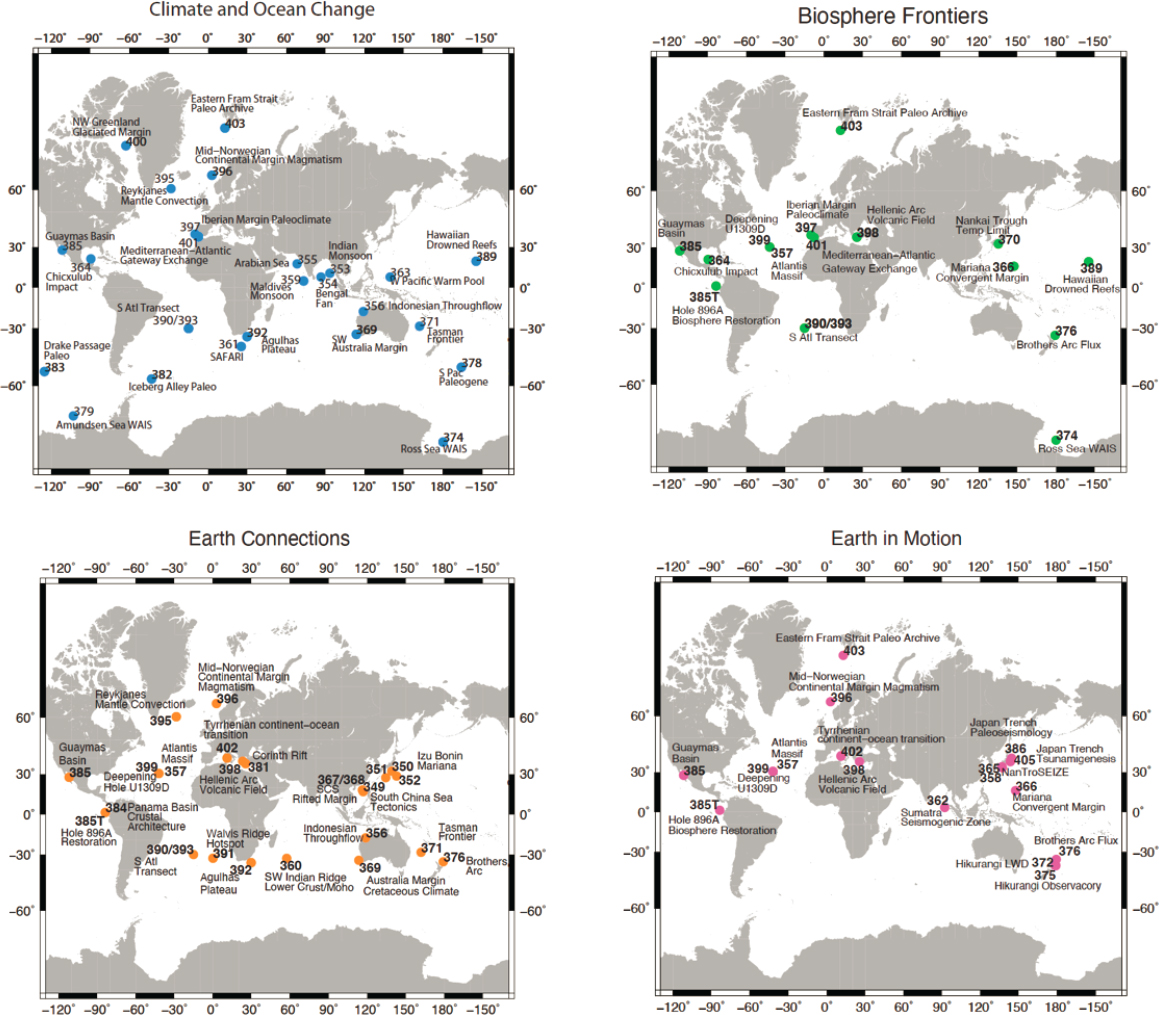

The committee focused on the progress made during the current funding phase of the drilling program, the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP-2), the research of which is guided by the community-developed 2013–2023 IODP Science Plan (IODP, 2011), organized around four science themes. From 2014 to 2023, the IODP-2 completed 57 expeditions: 46 with the JOIDES Resolution, 5 with the Chikyu, and 6 with mission-specific platforms (MSPs) (see Table 1.1 in Chapter 1). This high use of the JOIDES Resolution, compared with the other IODP-2 components, reflects the scientific interest and impact of the U.S.-sponsored program and the capabilities of its staff and assets.1 IODP-2 expeditions have aimed to address each of the four science themes through their project goals (Figure 3.1), with the greatest number of expeditions addressing challenges related to climate and ocean change, followed by Earth connections. Addressing these objectives required globally ranging scientific ocean drilling capabilities, as well as specialized platforms. Drilling during IODP-2 expeditions occurred in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian oceans, addressing all four themes, and in the Southern Ocean, addressing the themes of climate and ocean change and biosphere frontiers (Figure 3.2).2

___________________

1 While no IODP-2 expeditions were canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic, 14 occurred after its onset, several of which were delayed and thus lost days or weeks of operations, impacting the ability to achieve all objectives.

2 For an example of the type of reports produced by IODP expeditions, see http://publications.iodp.org/proceedings/385/385title.html. One Arctic MSP expedition was planned (Expedition 377) but had to be canceled due to Russia’s attack on Ukraine.

SOURCE: Michiko Yamamoto, IODP Science Support Office (Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, San Diego).

SOURCE: Michiko Yamamoto, IODP Science Support Office (Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California San Diego).

In addition to the scientific themes and challenges posed in the 2013–2023 IODP Science Plan, five high-priority science questions that depend on scientific ocean drilling were identified in Sea Change: 2015-2025 Decadal Survey of Ocean Sciences (DSOS-1) (NRC, 2015). Furthermore, the 2050 Science Framework (Koppers and Coggon, 2020) documents the international scientific ocean drilling community’s consensus on priority science areas (i.e., flagship initiatives) over the next 25 years. These flagship initiatives (see Box 2.1 in Chapter 2) are broadly similar to the 2013–2023 IODP Science Plan, but the 2050 Science Framework was written to address more intentionally the interconnectedness of Earth system processes in both curiosity-driven research to explore and understand and use-inspired basic research to inform and address challenges. The evolution in this framing reflects the growing interest and need in science to work more collaboratively across disciplines toward solving the complex, pressing issues facing society.

Table 3.1 provides an organizing framework to view the progress made on priorities laid out in DSOS-1 and the 2013–2023 IODP Science Plan, aligning the DSOS-1 priorities for which scientific ocean drilling was identified as either critical or important with the 2013–2023 IODP Science Plan challenges and themes. It lists completed IODP-2 expeditions that contributed (and continue to contribute) research outcomes addressing the prioritized science objectives and includes selected examples of key contributions toward IODP-2 Science Plan challenges and DSOS-1 priorities. A full review of the contributions of each expedition is not the intent of the table and is beyond the scope of this report.

Table 3.1 and this report overall are informed by expedition reports and publications of high scholarly impact. Presentations made at the DSOS-2 August 2023 meeting and the 2019 PROCEED workshop (IODP, n.d.j) hosted by the European Consortium for Ocean Research Drilling were also informative, as was Oceanography Magazine’s Special Issue on Scientific Ocean Drilling (Kappel, 2019), which acknowledges the scientific accomplishments and evolution of the drilling program over its 50-year history. However, it is also worth noting what is not informing this synthesis: to the knowledge of the committee, the scientific ocean drilling program has not conducted a formal evaluation of progress made toward the identified Science Plan challenges during the current funding phase. The lack of documented assessment—by the IODP Forum, IODP science facility boards or committees, and/or IODP science operators—on how the program is progressing toward addressing its specific priorities is a weakness in the program and contrasts with its pattern of regular operational assessments.

CONCLUSION 3.1 The scientific ocean drilling program would benefit from developing and executing a formal evaluation for assessing progress made toward achieving scientific priorities and for communicating and sharing the program’s achievements and value.

While much of the research from the current phase of the program is still in progress, the findings from several expeditions have already yielded significant contributions. Highlights of some of the scientific accomplishments identified in Table 3.1, as well as other key accomplishments, are described further in the sections that follow, organized within five high-priority research areas identified by the committee. This is not an all-encompassing review of the full scope of contributions, nor does it include unexpected discoveries that occurred outside of the prescribed boundaries of the Science Plan challenges or DSOS-1 priorities. Notably, accomplishments in science do not occur in isolation. They are often enhanced by connections to other fields of study (see Box 1.1 in Chapter 1), advances in tools and technologies (Box 3.1), development of new analytical methods and proxies (Box 3.2), and support provided by a diverse workforce (see Box 2.2 in Chapter 2).

TABLE 3.1 Progress Made Toward Past Research Priorities

| Completed IODP-2 Expeditions That Contributed or Are Contributing to Priority Areas | Selected Examples of Key Contributions | |

| IODP-2 Theme: Climate and Ocean Change: Reading the Past, Informing the Future | ||

| DSOS-1 What are the rates, mechanisms, impacts, and geographic variability of sea level change? |

Exp 359 Maldives Monsoon and Sea Level Exp 369 Australia Cretaceous Climate and Tectonics Exp 374 Ross Sea West Antarctic Ice Sheet Exp 379 Amundsen Sea West Antarctic Ice Sheet Exp 382 Iceberg Alley and Subantarctic Ice and Ocean Dynamics Exp 383 Dynamics of Pacific Antarctic Circumpolar Current Exp 389* Hawaiian Drowned Reefs Exp 390/393 South Atlantic Transect Exp 400 NW Greenland Glaciated Margin |

Documented influence of ice sheet dynamics on the magnitude of sea level change.

|

| IODP-2: How do ice sheets and sea level respond to a warming climate? | ||

| DSOS-1: How have ocean biogeochemical and physical processes contributed to today’s climate and its variability, and how will this system change over the next century? |

Exp 361 South African Climates Exp 363 Western Pacific Warm Pool Exp 369 Australia Cretaceous Climate and Tectonics Exp 371 Tasman Frontier Subduction Initiation & Paleogene Climate Exp 378 South Pacific Paleogene Climate Exp 382 Iceberg Alley and Subantarctic Ice and Ocean Dynamics Exp 383 Dynamics of Pacific Antarctic Circumpolar Current Exp 392 Agulhas Plateau Cretaceous Climate Exp 390/393 South Atlantic Transect Exp 395 Reykjanes Mantle Convection Exp 396 Mid-Norwegian Continental Margin Magmatism Exp 397 Iberian Margin Paleoclimate |

Gathered data on ocean circulation and climate sensitivity to changing greenhouse gas levels.

|

| IODP-2: How does Earth’s climate system respond to elevated levels of atmospheric CO2? | ||

| Completed IODP-2 Expeditions That Contributed or Are Contributing to Priority Areas | Selected Examples of Key Contributions | |

| IODP-2: What controls regional patterns of precipitation, such as those associated with monsoons or El Niño? |

Exp 353 Indian Monsoon Rainfall Exp 354 Bengal Fan Exp 355 Arabian Sea Monsoon Exp 356 Indonesian Throughflow Exp 359 Maldives Monsoon and Sea Level Exp 361 South African Climates Exp 363 Western Pacific Warm Pool Exp 389* Hawaiian Drowned Reefs |

Made major progress in understanding regional monsoon precipitation.

|

| IODP-2: How resilient is the ocean to chemical perturbations? |

Exp 364* Chicxulub K-T Impact Crater Exp 369 Australia Cretaceous Climate and Tectonics Exp 378 South Pacific Paleogene Climate Exp 392 Agulhas Plateau Cretaceous Climate Exp 390/393 South Atlantic Transect Exp 396 Mid-Norwegian Continental Margin Magmatism |

Identified physical and biogeochemical changes that affect ecosystems and climate.

|

| IODP-2 Theme: Earth Connections: Deep Processes and Their Impact on Earth’s Surface Environment | ||

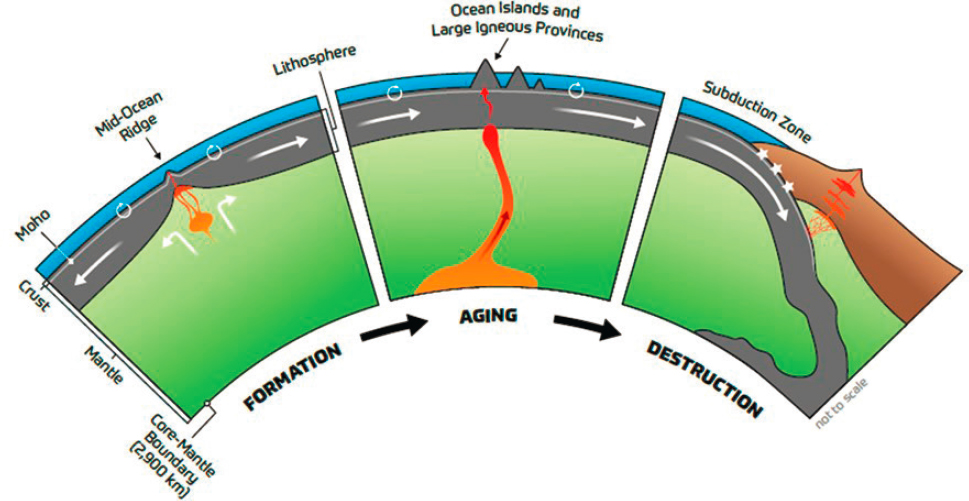

| DSOS-1: What are the processes that control the formation and evolution of ocean basins? |

Exp 356 Indonesian Throughflow Exp 357* Atlantis Massif Seafloor Processes: Serpentinization and Life Exp 360 SW Indian Ridge Lower Crust and Moho Exp 384 JOIDES Resolution Engineering Testing Exp 391 Walvis Ridge Hotspot Exp 392 Agulhas Plateau Cretaceous Climate Exp 395/395C Reykjanes Mantle Convection and Climate Exp 396 Mid-Norwegian Margin Magmatism Exp 398 Hellenic Arc Volcanic Field Exp 399 Building Blocks of Life, Atlantis Massif |

Fulfilled a 60-year goal of scientific ocean drilling by drilling into upper mantle rock.

|

| IODP-2: What are the composition, structure, and dynamics of Earth’s upper mantle? | ||

| Completed IODP-2 Expeditions That Contributed or Are Contributing to Priority Areas | Selected Examples of Key Contributions | |

| IODP-2 Theme: Earth Connections: Deep Processes and Their Impact on Earth’s Surface Environment | ||

| IODP-2: How are seafloor spreading and mantle melting linked to ocean crustal architecture? |

Exp 349 South China Sea Tectonics Exp 360 SW Indian Ridge Lower Crust and Moho Exp 366 Mariana Convergent Margin Exp 367/368 South China Sea Rifted Margin Exp 381* Corinth Active Rift Development Exp 384 JOIDES Resolution Engineering Testing Exp 385 Guaymas Basin Tectonics and Biosphere Exp 385T Panama Basin Crustal Architecture and Deep Biosphere Exp 390/393 South Atlantic Transect Exp 391 Walvis Ridge Hotspot Exp 392 Agulhas Plateau Cretaceous Climate Exp 395/395C Reykjanes Mantle Convection and Climate Exp 396 Mid-Norwegian Margin Magmatism |

Elucidated the processes by which ocean crustal architecture is created and modified, from rifting to seafloor spreading.

|

| IODP-2: How do subduction zones initiate, cycle volatiles, and generate continental crust? |

Exp 350 Izu-Bonin-Mariana Rear Arc Exp 351 Izu-Bonin-Mariana Arc Origins Exp 352 Izu-Bonin-Mariana Forearc Exp 358** NanTroSEIZE: Plate Boundary Deep Riser Exp 365** NanTroSEIZE: Shallow Megasplay Long-Term Borehole Exp 366 Mariana Convergent Margin Exp 371 Tasman Frontier Subduction Initiation and Paleogene Climate Exp 375 Hikurangi Subduction Margin Exp 380** NanTroSEIZE: Frontal Thrust Borehole Monitoring System Exp 398 Hellenic Arc Volcanic Field |

Used drilling results to understand how mantle melting processes evolve during and after subduction initiation.

|

| Completed IODP-2 Expeditions That Contributed or Are Contributing to Priority Areas | Selected Examples of Key Contributions | |

| DSOS-1: What is the geophysical, chemical, and biological character of the subseafloor environment |

Exp 357* Atlantis Massif Seafloor Processes: Serpentinization and Life Exp 366 Mariana Convergent Margin Exp 376 Brothers Arc Flux Exp 385 Guaymas Basin Tectonics and Biosphere Exp 385T Panama Basin Crustal Architecture and Deep Biosphere Exp 390/393 South Atlantic Transect Exp 392 Agulhas Plateau Cretaceous Climate Exp 395/395C Reykjanes Mantle Convection and Climate |

Developed new insights and models for chemical and fluid exchanges between ocean crust and seawater.

|

| IODP-2: What are the mechanisms, magnitude, and history of chemical exchanges between the oceanic crust and seawater? | ||

| IODP-2 Theme: Biosphere Frontiers: Deep Life and Environmental Forcing of Evolution | ||

| DSOS-1: What is the geophysical, chemical, and biological character of the subseafloor environment and how does it affect global elemental cycles and understanding of the origin and evolution of life? |

Exp 357* Atlantis Massif Seafloor Processes: Serpentinization and Life Exp 366 Mariana Convergent Margin Exp 376 Brothers Arc Flux Exp 385 Guaymas Basin Tectonics and Biosphere Exp 385T Panama Basin Crustal Architecture and Deep Biosphere Exp 390/393 South Atlantic Transect Exp 398 Hellenic Arc Volcanic Field |

Revealed global diversity of microbial communities in subseafloor environments.

|

| IODP-2: What are the origin, composition, and global significance of deep subseafloor communities? | ||

| IODP-2: What are the limits of life in the subseafloor realm? |

Exp 360 Indian Ridge Lower Crust and Moho Exp 370** Temperature Limit of the Deep Biosphere off Muroto Exp 375 Hikurangi Subduction Margin Observatory Exp 376 Brothers Arc Flux Exp 385 Guaymas Basin Tectonics and Biosphere Exp 385T Panama Basin Crustal Architecture and Deep Biosphere Exp 390/393 South Atlantic Transect Exp 398 Hellenic Arc Volcanic Field |

Made pioneering observations about microbial life in extreme environments.

|

| Completed IODP-2 Expeditions That Contributed or Are Contributing to Priority Areas | Selected Examples of Key Contributions | |

| IODP-2: How sensitive are ecosystems and biodiversity to environmental change? |

Exp 363 Western Pacific Warm Pool Exp 364* Chicxulub K-T Impact Crater Exp 382 Iceberg Alley and Subantarctic Ice and Ocean Dynamics Exp 383 Dynamics of Pacific Antarctic Circumpolar Current Exp 385 Guaymas Basin Tectonics and Biosphere Exp 389* Hawaiian Drowned Reefs Exp 390/393 South Atlantic Transect Exp 397 Iberian Margin Paleoclimate Exp 398 Hellenic Arc Volcanic Field |

Documented environmental changes and their ecosystem responses on a range of timescales and oceanic settings.

|

| IODP-2 Theme: Earth in Motion: Processes and Hazards on Human Timescales | ||

| DSOS-1: What is the geophysical, chemical, and biological character of the subseafloor environment and how does it affect global elemental cycles? |

Exp 357* Atlantis Massif Seafloor Processes: Serpentinization and Life Exp 372 Creeping Gas Hydrate Slides and Hikurangi LWD (logging-while-drilling) Exp 375 Hikurangi Subduction Margin Observatory Exp 381* Corinth Active Rift Development Exp 385 Guaymas Basin Tectonics and Biosphere Exp 386* Japan Trench Paleoseismology |

Documented new carbon-cycling links between the Earth’s surface and its deeper interior along plate boundaries.

|

| IODP-2: What properties and processes govern the flow and storage of carbon in the subseafloor? | ||

| IODP-2: How do fluids link subseafloor tectonic, thermal, and biogeochemical processes? |

Exp 357* Atlantis Massif Seafloor Processes: Serpentinization and Life Exp 365 **NanTroSEIZE: Shallow Megasplay Long-Term Borehole Exp 366 Mariana Convergent Margin Exp 370** Temperature Limit of the Deep Biosphere off Muroto Exp 375 Hikurangi Subduction Margin Observatory Exp 376 Brothers Arc Flux Exp 380** NanTroSEIZE: Frontal Thrust Borehole Monitoring System Exp 385 Guaymas Basin Tectonics and Biosphere Exp 385T Panama Basin Crustal Architecture and Deep Biosphere Exp 396 Mid-Norwegian Margin Magmatism |

Core records and borehole instruments advanced characterization of fluid flow in a range of environmental settings and made connections to climate change.

|

| Completed IODP-2 Expeditions That Contributed or Are Contributing to Priority Areas | Selected Examples of Key Contributions | |

| DSOS-1: How can risk be better characterized and the ability to forecast geohazards such as mega-earthquakes, tsunamis, undersea landslides, and volcanic eruptions be improved? |

Exp 358** NanTroSEIZE: Plate Boundary Deep Riser 4 Exp 362 Sumatra Seismogenic Zone Exp 365** NanTroSEIZE: Shallow Megasplay Long-Term Borehole Exp 372 Creeping Gas Hydrate Slides and Hikurangi LWD Exp 374 Ross Sea West Antarctic Ice Sheet Exp 375 Hikurangi Subduction Margin Observatory Exp 380** NanTroSEIZE: Frontal Thrust Borehole Monitoring System Exp 381* Corinth Active Rift Development Exp 386* Japan Trench Paleoseismology Exp 398 Hellenic Arc Volcanic Field |

Made major progress in deep drilling of plate boundaries and understanding a range of fault types, geologic properties, and motions leading to earthquakes; and new recognition of climatically linked submarine landslides.

|

| IODP-2: What mechanisms control the occurrence of destructive earthquakes, landslides, and tsunami? |

*Conducted on a mission-specific platform.

**Conducted aboard the Chikyu.

NOTES: Examples of progress made during the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP-2) are mapped against research priorities included in Sea Change: 2015–2015 Decadal Survey of Ocean Sciences (DSOS-1) (NRC, 2015) that require or include ocean drilling and challenges, and themes from the 2013–2023 IODP Science Plan (IODP, 2011). Expeditions with no asterisks were conducted aboard the JOIDES Resolution. Scheduled_expeditions for the remainder of the current phase of the IODP program: Exp 401 Mediterranean-Atlantic Gateway Exchange; Exp 402 Tyrrhenian Continent-Ocean Transition; Exp 403 Eastern Fram Strait Paleo-archive; and Exp 405** Japan Trench_Tsunamigenesis. Exp = expedition; kyr = thousand years; Ma = million years ago; myr = million years.

SOURCE: List of categorized expeditions informed by Brinkhuis, 2023.

BOX 3.1

Advances in Tools and Technologies

Scientific progress can be advanced by developing and diversifying tools and technologies, as exemplified by scientific ocean drilling. Operational enhancements in response to requests by the scientific community during the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP-2) include:

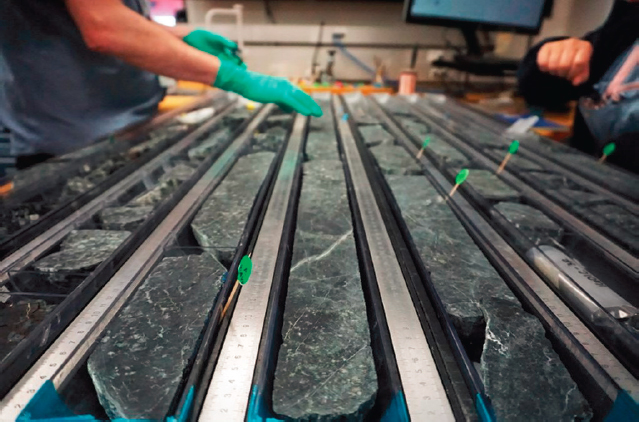

- New options for core recovery in special settings. Giant piston coring (see Box 2.1 in Chapter 2) is a suitable coring approach for achieving scientific objectives that require high-resolution records of the very recent past (late Pleistocene to Holocene). Giant piston coring was used for the first time on mission-specific platform (MSP) Expedition 386 (Strasser et al., 2019), which aimed to recover a continuous record of prehistoric (preinstrumental) earthquake events in the Japan Trench at over 8,000-m water depth.

- Use of seabed drilling systems. Seabed drilling systems (Box 2.1) were used for the first time for the microbiology- and tectonics-focused MSP Expedition 357 (Früh-Green, 2015), in order to recover a complex, shallow mantle sequence on the flank of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. The expedition successfully utilized other new technologies, including an in situ sensor package and water-sampling system placed on the seabed drills to evaluate physical and chemical properties (e.g., dissolved oxygen, methane, pH, temperature, and conductivity) during drilling. Additionally, a borehole plug system was installed at the drill site, allowing reaccess for future sampling, which then demonstrated that contamination tracers can be delivered into drilling fluids when using seabed drills.

- Piston coring tools to improve core recovery in challenging lithologies. The advanced piston corer (APC) (Box 2.1) used on the JOIDES Resolution is the primary coring tool used to obtain the highest-quality cores for high-resolution climate and paleoceanographic studies. However, it does not work well when the subseafloor layers are too firm or when hard and soft layers alternate. To address these operational challenges, a new, shorter (4.7-m) version of the APC, called the half-length APC (HLAPC) (IODP, n.d.k) was developed. Since 2013, the HLAPC as been useful in extending the depth (i.e., age) range for recovering undisturbed sediment suitable for high-resolution research (IODP, n.d.l). The HLAPC has also been useful in recovering difficult-to-core lithologies. For example, it recovered critical intervals of sands in the Bengal and Nicobar fans (Expeditions 354 and 362), at depths up to 800 m below the seafloor, and in the Mariana serpentinite mud volcanoes (Expedition 366). The HLAPC has been used extensively during IODP-2, accounting for about 21 percent of all piston coring.

- New drill-in-casing system and hydrologic release tool to save operational time and cost. Deep sediment holes, including those that penetrate basement rock below sediments, traditionally require a deep hole to be predrilled and double- and triple-casing walls (referred to as casing strings) to be installed to stabilize the upper hole. These are time-consuming efforts, often requiring 7–10 days of ship time. A drill-in-casing system was developed for the JOIDES Resolution to save time and hardware costs when scientific objectives require deep sediment penetration or when starting holes in bare rock. The concept was demonstrated in 2014 as a more time-efficient approach to drilling in a single casing string with a special reentry system and without predrilling a hole, allowing a greater number of deep-penetration holes to be attempted and at a lower cost. In addition, a hydraulic release tool (HRT) (IODP, n.d.g) was adapted to drill in a reentry system with a short casing string to start a hole in bare-rock seafloor at Southwest Indian Ridge (Expedition 360). The HRT reentry system has continued to be simplified and is now being used as the standard drill-in-casing system to establish a single-casing string for deep sediment penetration. As of September 2023, 23 holes have been cased using this approach, collectively saving ~90–140 days of operational time and leaving time to achieve other science objectives.

BOX 3.2

Analytical Chemistry and Proxies of Past Ocean Conditions

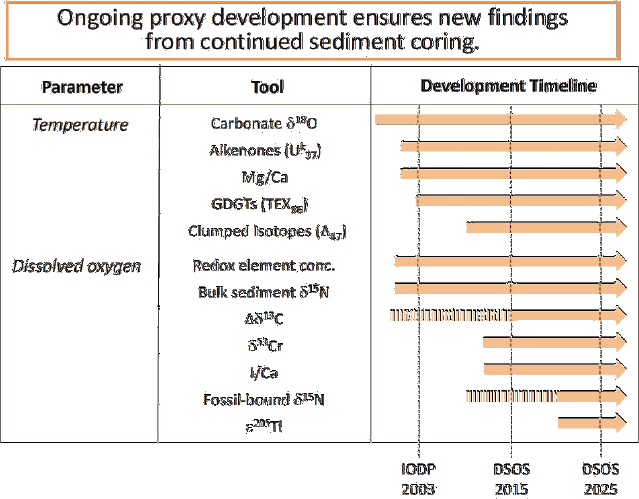

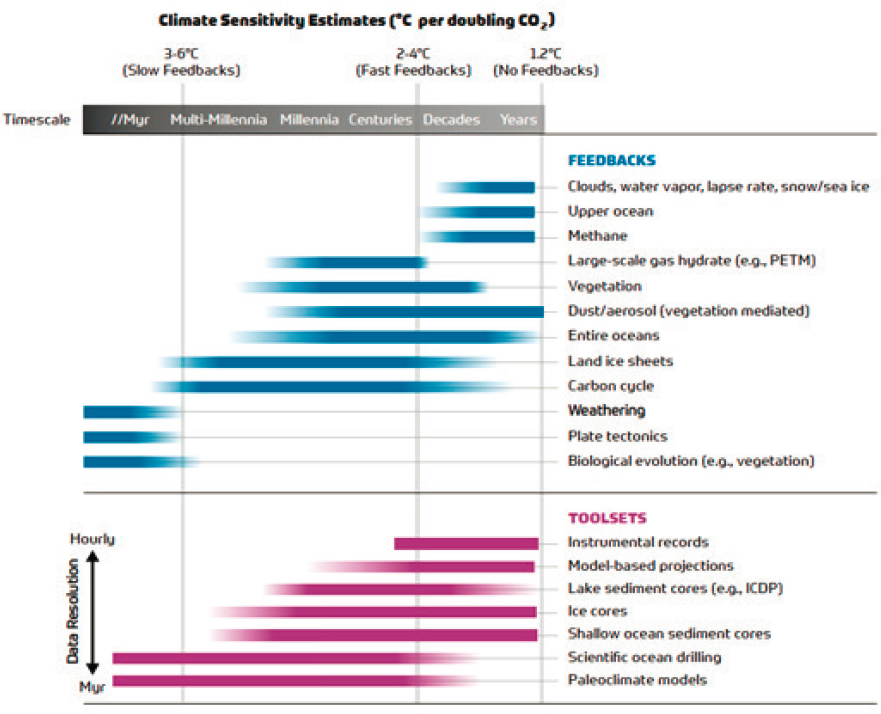

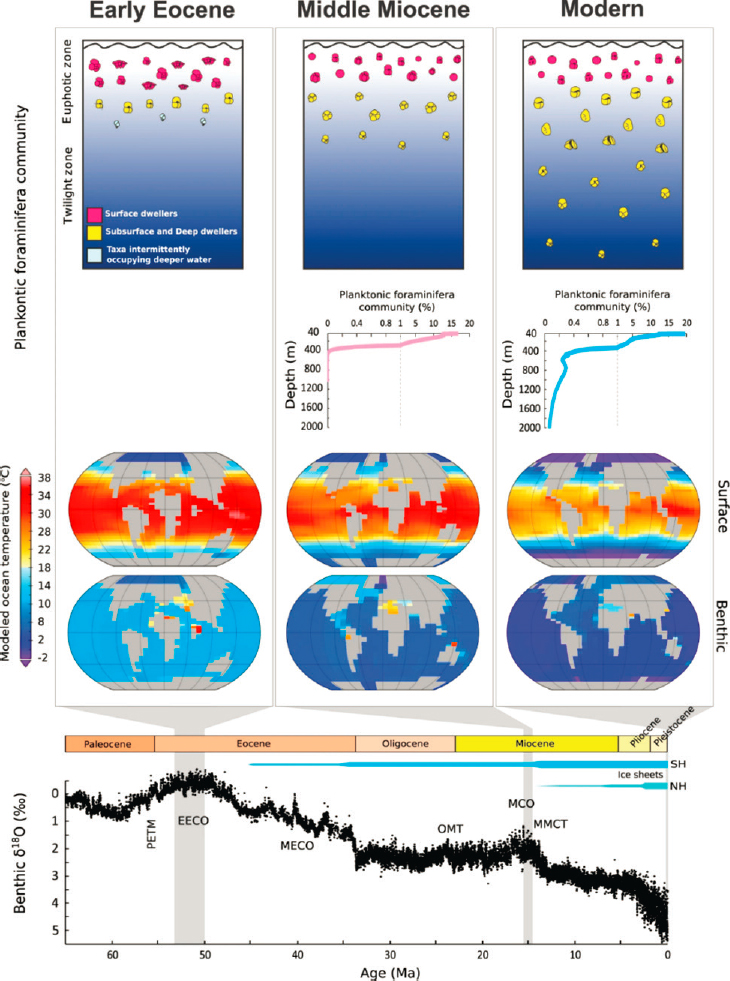

Understanding Earth’s evolution, from the genesis of ocean crust to changes in climate to the diversity of the subseafloor microbial communities, is based largely on biogeochemical evidence extracted from rocks and fossils recovered by scientific ocean drilling. The process of extracting this information, however, is challenging, hinging on the ability to analyze a wide range of materials, often on the micro scale, with high precision. As such, technological advances in analytical chemistry, from sample extraction and processing to instrumentation, have played a critical role in addressing a range of scientific questions. This critical role is particularly evident in efforts to reconstruct changes in ocean temperatures and chemistry by proxy (i.e., based on the chemical/isotopic composition of planktonic and benthic microfossils). Much of the pioneering work on reconstructing variations in ocean temperature, based on the oxygen isotope ratios (18O/16O) of calcite shells of plankton, was facilitated by the development of mass spectrometers. Further advances in mass spectrometry then allowed for the separation and analysis of carbon isotopic ratios (13C/12C) of algal organic compounds, a proxy for seawater carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations. In combination, these advances enabled the first assessment of past climate sensitivity to greenhouse gas forcing, albeit with large uncertainties. The mass spectrometer, related technologies, and analytical techniques, have continued to advance further (Figure 3.3), allowing for reduced uncertainties and the continued development of new proxies of a wide range of seawater parameters, such as temperature, salinity, dissolved O2, and nutrient concentrations and pH (e.g., boron isotopes), leading to the reconciliation of past changes in climate, ocean dynamics, and biogeochemical cycling. While the new proxies are being applied to legacy materials, most critical intervals have been depleted to the point where additional cores are required to take advantage of these recent technological developments.

SOURCE: From Jesse R. Farmer, University of Massachusetts Boston, and Daniel M. Sigman, Princeton University.

SCIENTIFIC OCEAN DRILLING RESEARCH PRIORITIES

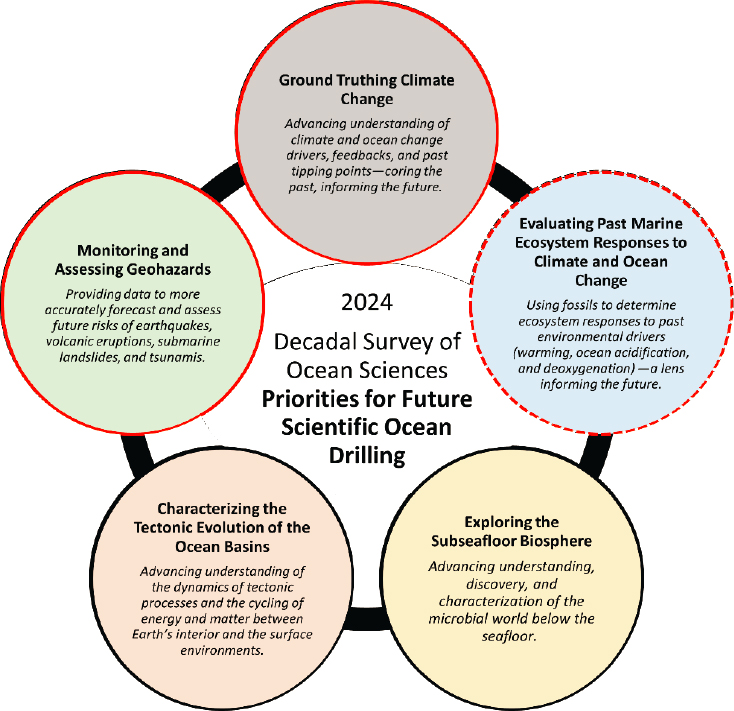

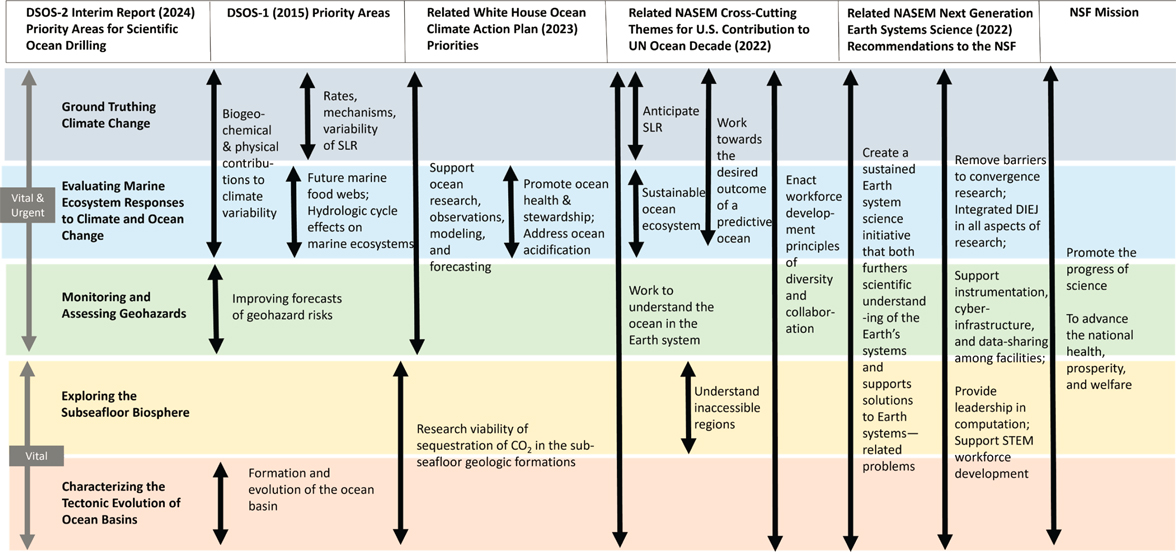

The remainder of this chapter is organized under the five research areas (Figure 3.4) that the committee identified as high priority and that continue to require scientific ocean drilling to be understood:

- ground truthing climate change

- evaluating marine ecosystem responses to climate and ocean change

- monitoring and assessing geohazards

- exploring the subseafloor biosphere

- characterizing the tectonic evolution of the ocean basins

The committee’s five high-priority areas are informed by, but independent of, previous scientific ocean drilling planning efforts. Although details and nuances vary, these priorities are consistent with the 2050 Science Framework flagship initiatives and priorities laid out in preceding science plans. The five high-priority areas have broad topical relationships to the scientific questions that emerged during the first DSOS-1 review and to the current IODP-2 Science Plan (Table 3.1), and they incorporate aspects of the 2050 Science Framework’s strategic objectives, which highlight the research needed to understand the interconnected processes in the Earth system (Figure 1.4).

CONCLUSION 3.2 The committee identified five (unranked) high-priority research areas that require future scientific ocean drilling: (a) ground truthing climate change, (b) evaluating past marine ecosystem responses to climate and ocean change, (c) monitoring and assessing geohazards, (d) exploring the subseafloor biosphere, and (e) characterizing the tectonic evolution of ocean basins. Though differing in detail and nuance, the priority areas align with the initiatives identified by the scientific ocean drilling community.

Ground Truthing Climate Change

Advancing understanding of climate and ocean change drivers, feedbacks, and past tipping points—coring the past, informing the future.

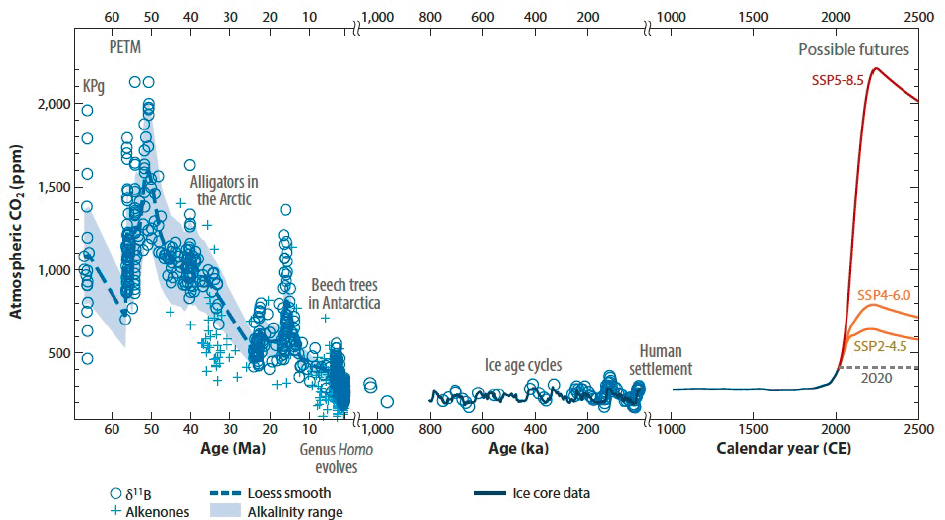

Earth’s climate is currently in a transient (nonequilibrium) state because of the unprecedented rate of greenhouse gas emissions in the past 100+ years. Earth’s climate system has not fully responded to the dramatic increase in greenhouse gases; changes are still occurring in response to the forcing (i.e., drivers). Additionally, different parts of the climate system (e.g., ice sheets vs. sea ice, surface ocean vs. deep ocean, polar regions vs. temperate regions) are responding at different rates. As such, direct observations of the global climate from less than a century ago provide too little data to adequately assess the ability of advanced models to accurately simulate Earth’s climate at greenhouse gas levels significantly higher (or lower) than present (Figure 3.5).

Primary sources of model uncertainty include feedbacks, both physical (ocean circulation, heat storage and transport, clouds) and biogeochemical (carbon cycle), that can potentially amplify (or dampen) the response to forcing. That the response of both physical and biogeochemical feedbacks is nonlinear poses a significant challenge for modeling. As such, testing the skill of models, reducing uncertainties, and learning more about the Earth system’s response to changes in forcing (i.e., greenhouse gases), requires an examination of past changes in climate as case studies.

SOURCE: Used with permission of Rae et al., 2021.

Determining how much the global average temperature is expected to change in response to a given change in the amount of atmospheric greenhouse gases is challenging but essential to refining model forecasts of future climate scenarios. Scientific ocean drilling plays an important role in achieving this objective. Earth’s equilibrium climate sensitivity to greenhouse gas (e.g., carbon dioxide [CO2]) forcing has long been unresolved in climate models, exhibiting a wide range of sensitivities, from ~2.0 to 5.0°C per doubling of CO2 (see Sherwood et al., 2020). Observations of past climates, particularly over long periods of time with extremes in CO2 (e.g., early Eocene climatic optimum, 53 Ma), can provide insight into equilibrium climate states under a wide range of atmospheric CO2 concentrations (~180–2,000 ppm) (Rohling et al., 2018) and into transient climate states when the rate of rise in greenhouse gas was on the scale of modern rates (>1 petagrams [Pg] of carbon per year; 1 Pg = 1015 grams).

Furthermore, with the rapid rate of Arctic warming and reduced seasonal and permanent sea ice today, the modern ocean may be approaching a tipping point in which the sinking of water in the North Atlantic, an important driver of the Atlantic meridional ocean circulation (AMOC; see Figure 1.2 in Chapter 1), may cease. Present model forecasts offer different perspectives on potential future changes (Ditlevsen and Ditlevsen, 2023). Forecast differences are perhaps due to limited direct observations (F. Li et al., 2021) and minimal understanding of tipping points in global ocean circulation and their broader consequences.

Given the importance of the ocean to meridional heat transport (Trenberth and Caron, 2001) and carbon cycling (Sigman and Boyle, 2000; Toggweiler, 1999), climate and Earth system models that investigate these interrelated processes, and changes that may occur, require validation based on known past scenarios, knowledge that can be gained only by scientific ocean drilling. This is perhaps the most urgent goal of ocean drilling today.

Progress Made During IODP-2

Several expeditions have provided key contributions to understanding past climate and ocean change, with implications for understanding future ocean change. Collectively, these results have fundamentally improved understanding of the linkages between the ocean, climate, and rates of climate change relevant to the challenges facing society today and in the near future. Such work was possible in large part because of research involving paleoclimate proxies of climate and ocean variables. The proxy data collected and measured essentially serve as surrogates, or indirect indicators, of past changes in temperature, ice volume, and ocean chemistry, among others.

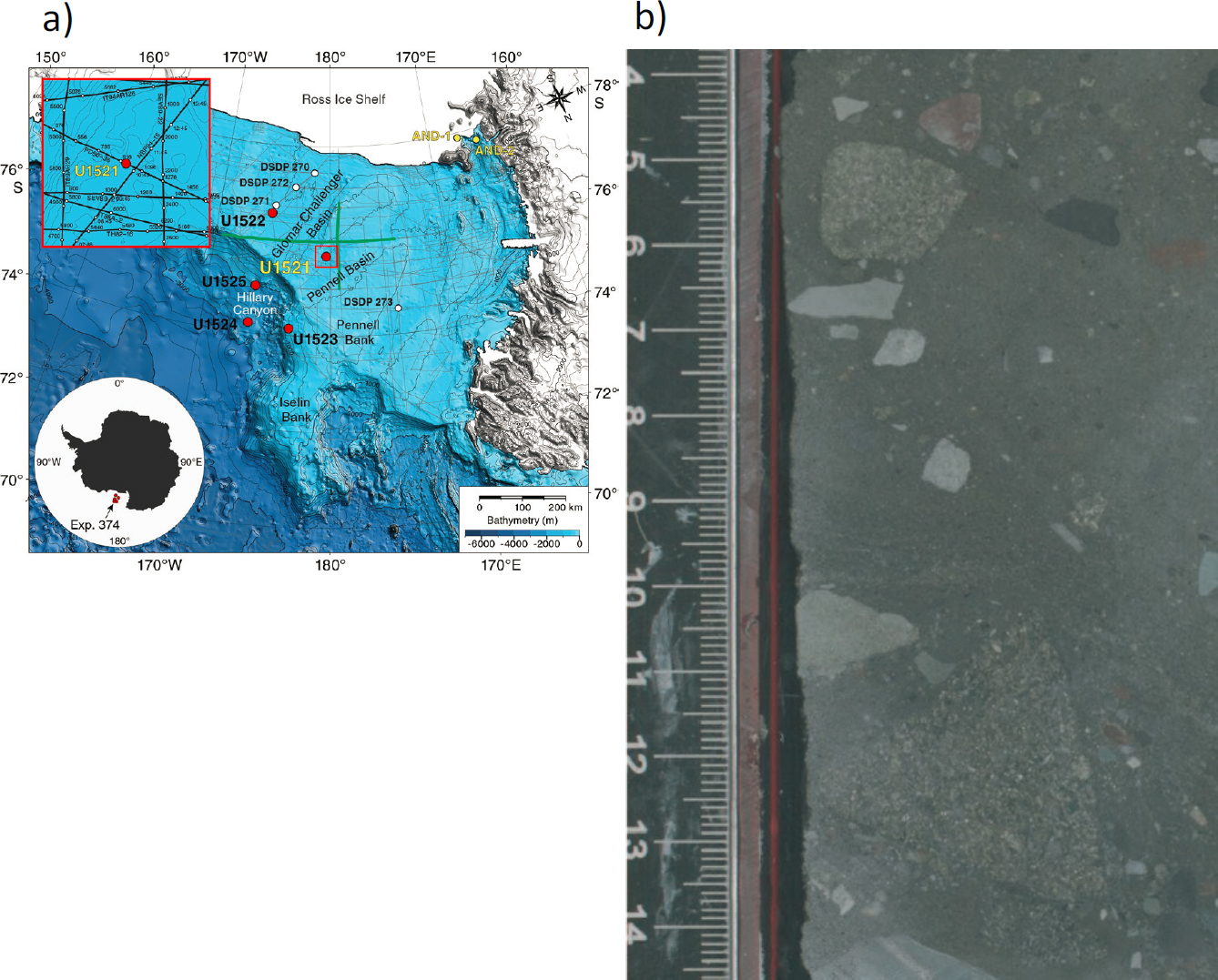

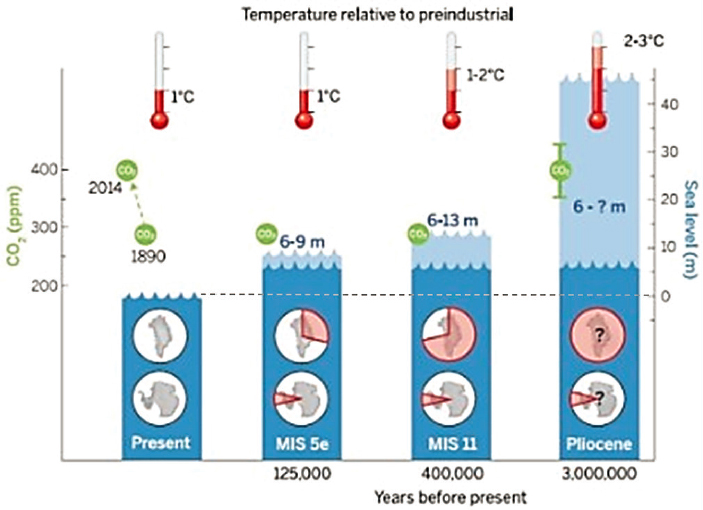

Expeditions to the Southern Ocean directly addressed the past dynamics of ice sheets and sea levels. These included expeditions to the Ross, Amundsen, and Weddell seas, which yielded several key advances. Cores from the Ross Sea were used to reveal the previous presence of a large West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) during the middle Miocene (18–14 Ma; Figure 3.6), which could account for the 40- to 60-meter sea level variations previously documented from both pelagic and continental margin records. In the absence of a WAIS, such large-amplitude sea level changes would require complete loss of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet, something that could not be achieved in models, even under high levels of CO2 (Marschalek et al., 2021). Furthermore, analysis of cores from the Amundsen Sea revealed significant retreat of the WAIS during the middle Pliocene warm period, 3.3–3.0 Ma (Gohl et al., 2021).

Expeditions designed to assess the sensitivity of the climate system to higher greenhouse gas levels in the past (i.e., 60–3 Ma) included coring of the western equatorial Pacific and South Pacific, and along the South Africa margin. Analysis of the sediment cores collected in the Pacific addressed several questions related to the role and response of the western Pacific warm pool (i.e., especially warm surface waters in the western equatorial Pacific Ocean) to variations in greenhouse gases, on millennial and longer timescales. Reconstructions showed that regional sea surface temperature varied in sync with greenhouse gas levels over the last 12 myr, including during the Holocene. This finding helped resolve a critical discrepancy between models and previous reconstructions of Holocene global temperatures. Cores recovered along the South Africa margin supported models that attributed redistribution of salinity differences between the ocean basins as a primary factor in driving changes in global ocean circulation patterns during glacial periods.

Changes in precipitation patterns (i.e., hydroclimates) associated with climate change will have profound impacts on society, particularly at the regional scale. Such systems include seasonal monsoons and atmospheric

SOURCE: McKay et al., 2019.

rivers that impact billions of people. Informing models on the evolution of regional monsoons over glacial–interglacial cycles in response to the warming caused by the increase of greenhouse gases was the goal of expeditions to the Indian Ocean, Arabian Sea, and Maldives. Major scientific contributions from these expeditions include establishing the timing and origin of the onset of the modern South Asian monsoon. This work provided new understanding of the evolution of Plio-Pleistocene summer monsoon rainfall, leading to better model-predicted increases in monsoon precipitation and variability due to greenhouse gas forcing. Furthermore, data from these cores were used to demonstrate how high-latitude cooling around Antarctica from 12 to 8 Ma initiated major changes in precipitation patterns in Australia and Southeast Asia.

Despite an increase in the atmosphere’s vapor-holding capacity with increasing temperature, the hydrologic cycle is expected to amplify meridional vapor transport and precipitation cycles while shifting major rain patterns (Held and Soden, 2006; Trenberth, 2011). Although all models show hydrologic intensification, the exact patterns

and magnitudes of change vary from model to model. Verification of the sensitivity of the hydroclimate to global warming has come mainly from paleo observations of the recent and more distant past. The paleo observations are largely preserved in ocean basins where wind and runoff deposit the signals of the local hydroclimate. Evidence for larger-scale changes in the hydrologic cycle are best preserved in deep-sea archives, particularly during extreme warm periods. Model simulations of these extremes show that increased meridional vapor transport resulted in significantly steeper meridional sea surface salinity gradients, with higher salinities in the tropics and lower salinity at high latitudes (Carmichael et al., 2016, 2017), not unlike forecasts for the future.

To address additional model uncertainties, the international climate modeling community initiated a coordinated effort to compare all major models using select reconstructions of past climates. This effort, designated the Paleoclimate Model Intercomparison Project (PMIP), was established to evaluate the models; understand the model–model and model–data differences; and, where possible, provide suggestions for model improvements. Following protocol, PMIP focused initially on the last glacial–interglacial transition, but it eventually extended its work to focus on the extreme greenhouse intervals (e.g., middle Miocene, Eocene, and Paleocene–Eocene thermal maximum [PETM]), periods when CO2 levels were in the range expected by the year 2100 (600–1,000 ppm; Figure 3.5). This effort, called the Deep-Time Model Intercomparison Project, has contributed to a better understanding of the mechanisms of climate change and the role of climate feedbacks (Hollis et al., 2019; Lunt et al., 2017). It has provided the first robust paleo-based estimates of Earth climate sensitivity (Lunt et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2021). The most recent studies utilizing reconstructions of sea surface temperatures and CO2 are derived largely from sediment samples recovered by scientific ocean drilling (Hollis et al., 2019) and suggest an Earth climate sensitivity closer to the high end of 3.5–4.0°C per doubling of CO2.

Finally, observations of the last several hundred thousand years collected by scientific ocean drilling reveal millennial-scale ocean circulation changes with far-reaching impacts. For example, changes in heat transport potentially impact ice sheets in the opposing hemisphere, as well as global atmospheric circulation and hydroclimate in general (e.g., Brahim et al., 2022).

High-Priority Future Research

Additional proxy-based observations obtainable only by scientific ocean drilling are required to assess the accuracy of climate models in replicating greenhouse gas–forced changes, including tipping points in ice sheet dynamics and sea level change, ocean circulation, and global temperatures (Figure 3.5; Box 3.2). In fact, the tipping points in Earth’s interconnected climate system require greater understanding (McKay et al., 2022). Responses to climate forcings can be nonlinear; what may be gradual change initially can shift to rapid change if a critical threshold, or tipping point, is reached. Furthermore, observational gaps remain for the past extreme greenhouse gas periods in two climatically sensitive regions: the Arctic, where long cores that span the necessary time periods are from a single subseafloor site, and the equatorial ocean, where a single record from the Indian Ocean suggests that coastal ocean sea surface temperatures might have exceeded 40°C during the PETM.

Previous reconstructions of ocean circulation of the last glacial maximum established the presence of stable modes of the AMOC with weaker deep-water production in the North Atlantic (Böhm et al., 2015). However, the climatic conditions (e.g., temperature, sea surface salinity) that define the bounds of tipping points (i.e., mode switches) for the hydrographic parameters in areas of deep-water formation remain poorly understood. Such an abrupt rearrangement of large-scale circulation has the potential to impact climate regionally and globally; thus, understanding these parameters is important. In addition, structural changes in the deep circulation may significantly impact the accumulation and return of nutrients and oxygen and carbon dioxide to the surface ocean and thus influence marine biological productivity and carbon fluxes. A greater understanding of the past major circulation regimes would provide insight into the potential modes of circulation possible in the future. For example, recent simulations of the early Eocene circulation using an advanced Earth system model (Zhang et al., 2020) show enhanced ocean heat transport and Southern Ocean warming due to a more vigorous rate of overturning compared with simulations using other models (e.g., Winguth et al., 2012).

Accurate predictions of how much global mean sea level (GMSL) could rise in the near future are not possible based only on modern observations. While thermal expansion of seawater and melting of glaciers have dominated

SOURCE: Modified from Rohling et al., 2012.

GMSL rise over the last century, mass loss from the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets is expected to exceed other contributions to GMSL rise under future warming scenarios (Dutton et al., 2015). Therefore, forecasting the response of these ice sheets and GMSL to warming remains an important, yet challenging, task. The challenges stem partly from an incomplete understanding of ice sheet and ice stream internal dynamics, as well as the role of heating from above and below. Moreover, recent advances in representing the dynamics of ice loss at shelf edges suggest a much higher sensitivity in sea level response to small changes in temperature at the regional scale (DeConto and Pollard, 2016; DeConto et al., 2021). As such, a better understanding of how the lost mass of ice sheets contributed to sea level rise during past warm periods can constrain the process-based models used to project ice sheet response and sensitivity to future climate change (Figure 3.8). Scientific ocean drilling is the only means of reconstructing ice sheet changes during analogous times of warming in the deeper past. While efforts thus far have focused largely on recent interglacials (with emphasis on 200,000–100,000 years ago), when sea level was higher despite similar levels of preindustrial CO2 (280–300 ppm), more recent studies have focused on times when ice sheets existed, and CO2 levels were in the range projected for the present or near future

SOURCE: Dutton et al., 2015.

(400–800 ppm; Figure 3.5). Crucially, the latest reconstructions of the Antarctic landmass extent and elevation during these warm periods have been key to reconciling the changing sensitivity to greenhouse gas forcing with the present (Marschalek et al., 2021). Incorporating constraints on ice sheet extent and estimates of regional sea level to constrain and test models of these warm periods will require future scientific ocean drilling.

Reconstructing sea surface salinity gradients during periods of elevated greenhouse warming would be a key test of first-order predictions of how hydroclimates change under greenhouse climate states. A minor misrepresentation of the dynamics of vapor transport could seriously bias climate models in multiple ways. In this regard, efforts to establish past changes in vapor transport would benefit from more detailed spatial (meridional) sediment cores spanning the geography of net evaporation and precipitation during the extremes. In yet another observations gap, core records of monsoon systems have been obtained mainly from the Northern Hemisphere (primarily from ocean basins in South Asia). Collection must be expanded to the Southern Hemisphere, and the cores must be deep enough to sample further back in time to periods of extreme warmth in both hemispheres.

CONCLUSION 3.3a Additional observations obtainable only by scientific ocean drilling are required to assess the skill of climate models to replicate greenhouse gas–forced switches (i.e., tipping points) over geological timescales in temperatures, ice sheet dynamics, sea level, and ocean circulation and to constrain the role of feedbacks (physical or biogeochemical responses that amplify or dampen perturbations). To constrain Earth climate sensitivity to high greenhouse gas levels, additional scientific drilling is required to fill data gaps for extreme warm intervals in climatically sensitive regions (e.g., the Arctic and equatorial oceans, and in a few cases, the midlatitudes). Similarly, to fully characterize the sensitivity of hydroclimates (including regional monsoons) to greenhouse gas forcing, records obtained for the Northern Hemisphere need to be complemented with records from the Southern Hemisphere.

Evaluating Past Marine Ecosystem Responses to Climate and Ocean Change

Using fossils to determine ecosystem responses to past environmental drivers (warming, ocean acidification, and deoxygenation)—a lens informing the future.

Seafloor sediment microfossils (i.e., small, mineralized fossils) and molecular fossils preserve a history of marine biodiversity, including the origin and extinction of species. They are used to better understand how climate and ocean changes affect the evolution of life and ecosystems, and of marine biodiversity and distributions through long periods of time. Determining the timing of extinction and speciation events through microfossils is essential for further developing regional age-depth models (allowing paleoceanographers to convert subseafloor depth to age and determine sedimentation rates), as well as to tracking ecosystem evolution and reconstructing past ocean conditions.

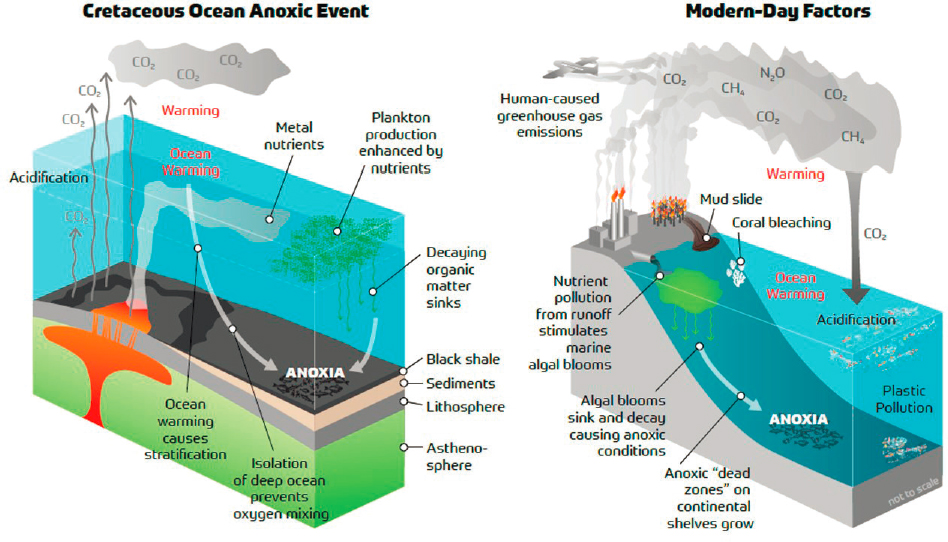

The future impacts of rapid global change on marine ecosystems are unknown, but some insights can be gained from studying past long-term environmental perturbations, which have influenced the evolution of marine organisms and ecosystems. Understanding the details of ecosystem response to these past events also provides opportunities to test advanced Earth system and ecosystem models designed to simulate the impacts of continued anthropogenic carbon emissions and global warming on marine ecosystems. Indeed, the closest analogs to Earth’s likely future are the transient climate events known as hyperthermals, lasting 10,000 –20,000 years, that occurred during the early Cenozoic interval of elevated warmth (~60–40 Ma) (Norris et al., 2013).

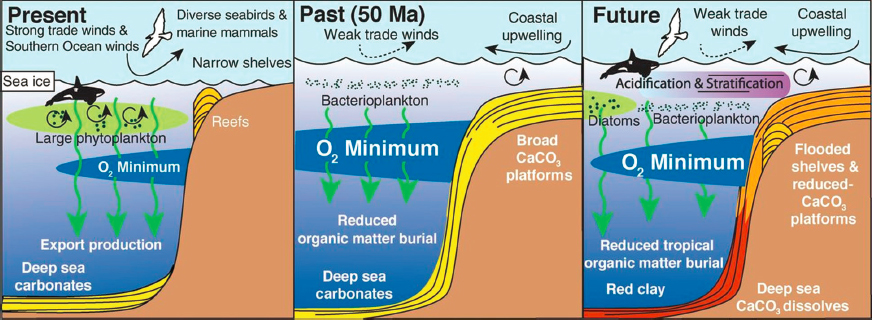

Looking forward, the combination of warming-induced changes in ocean circulation and stratification coupled with acidification and deoxygenation has the potential to significantly modify ocean ecosystem structures across the planet. The most severe impacts might result from cascading effects on large-scale biogeochemical processes—such as microbial respiration, particle remineralization and O2 consumption, denitrification and nitrogen fixation—and hence, biological export production (Henson et al., 2022; Hutchins and Capone, 2022; Thomalla et al., 2023). These changes would be in addition to the more predictable first-order poleward shifts in biogeographic ranges of most species. Furthermore, the ecological impacts will be significantly compounded at the coasts by changes in regional precipitation, runoff, and nutrient supply. All these changes have the potential to constrict habitability for most marine taxa.

Past perspectives derived from scientific ocean drilling improve understanding of the potential range of ocean states, providing insights into the historical range of ecosystem responses to changes in ocean and climate conditions (Halpern et al., 2015), and informing ecosystem models. Dozens of metrics, indicators, and even thresholds delineate ocean ecosystem conditions in modern times (Rice and Rochet, 2005), including the presence of common chemicals, abundance of key biota, rates of key ecological processes, and emergent properties of marine ecosystems (e.g., biodiversity); but it is only from past records of ocean conditions analogous to those predicted that paleobiologists can gain direct evidence of what the future may hold for marine ecosystems.

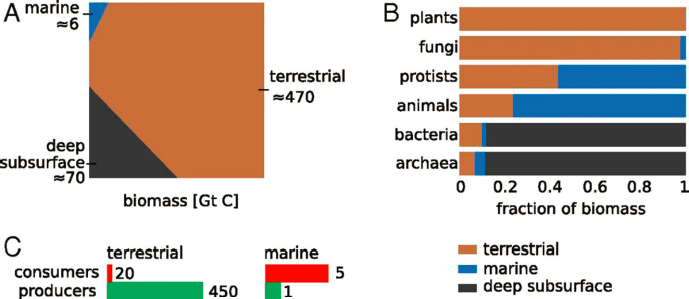

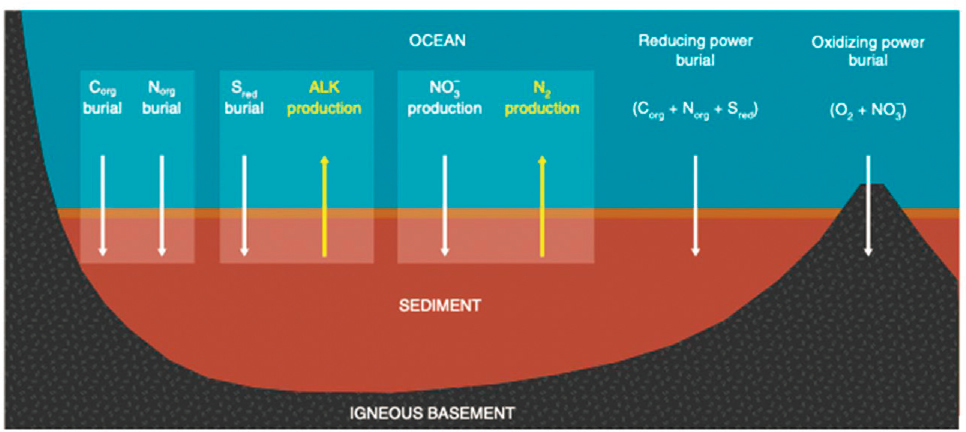

Global warming will likely lead to vertical compression of upper-ocean ecosystems via a weakened biological pump3 (Figure 3.9). Under normal conditions, with a thermally stratified water column, a substantial fraction of

___________________

3 The biological pump is a set of processes by which the ocean biologically sequesters atmospheric carbon from surface waters into the ocean’s interior.

SOURCE: Figure and modified caption from Norris et al., 2013.

sinking particle fluxes escapes remineralization in the surface ocean mixed layer, enabling various plankton (and benthic) species to survive at depths well below the photic zone, or in what is commonly referred to as the twilight zone. This is also the depth at which the level of dissolved oxygen is reduced via respiration, creating an oxygen minimum zone (OMZ) and oxygen deficient zones (ODZs). In theory, with warming of the surface ocean, nutrient delivery from upwelling will decrease and the rate of remineralization of organic detritus in the upper ocean will increase, thus reducing the sinking particle flux and forcing deep-dwelling plankton closer to the surface (vertical compression). In addition to the impact on species distribution and ecosystem structure, a weakened biological pump will reduce the extraction of CO2 from the surface ocean, a potential positive (i.e., reinforcing) feedback on global warming. This state, with decreased consumption of oxygen by respiration in the dark ocean, could potentially represent the equilibrium state for a warmer ocean, at least as simulated by Earth system models, whereas the nonequilibrium transient state might be characterized by deoxygenation due to enhanced stratification.

Progress Made During IODP-2

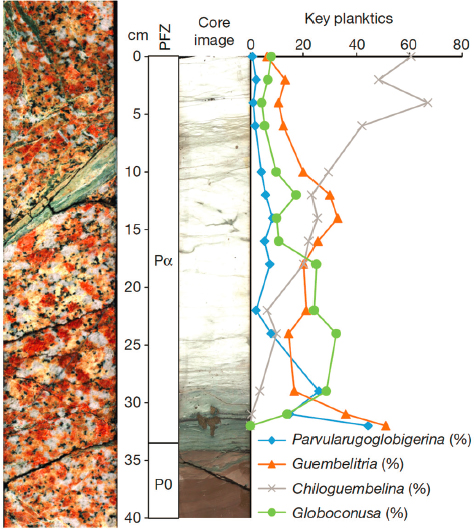

Microfossil studies during IODP-2 that utilized newly recovered marine sediment archives and those already stored in core repositories documented environmental changes and their ecosystem responses on a range of timescales and oceanic settings. Perhaps more dramatic, scientific ocean drilling has uniquely documented extinction and the rapid recovery of marine benthic and planktic life at the Chicxulub impact crater (Lowery et al., 2018) (Box 3.3). Other work on microfossils from globally distributed sites has demonstrated that the efficacy of the biological pump and carbon cycling in the upper ocean was strongly controlled by temperature in the late Neogene (past 15 myr) (Boscolo-Galazzo et al., 2022). Globally distributed marine microfossil records have also revealed

BOX 3.3

Drilling the Cretaceous–Paleogene Impact Crater and Documenting the Demise and the Recovery of Life

The dinosaurs were not the only forms of life that went extinct 66 million years ago when a 10-km asteroid struck what is now the Yucatan Peninsula and continental shelf waters; 76 percent of all species on Earth were eradicated during the end-Cretaceous mass extinction. Dramatic details of the widespread catastrophic event were documented pristinely during Ocean Drilling Program Expedition 171 from sediment cores in the western North Atlantic Ocean—at a site that was ~1,500 km away from point of impact (Norris et al., 1998). A replica of the famous Expedition 171 core section is on display in the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History Ocean Hall. Eighteen years later, another major accomplishment took place: International Ocean Discovery Program Expedition 364 (Morgan et al., 2016) used a unique mission-specific “lift boat” to drill into the exceptionally preserved Chicxulub impact crater. The cores recovered from this site are astonishing. Expedition drilling evidence shows that when the Chicxulub asteroid hit, the Earth rebounded, bringing up pink granite (Figure 3.10, left core photo) from 10 km below the surface, which collapsed around the center of the crater to form concentric rings. Computed tomography scans showed that the fractured and porous rock had many pathways for fluids, making it an intriguing place to look for the recovery of life, in the form of microbes in the peak ring. Paleontological and geochemical studies of cores several hundred meters above these basement impact structures documented how this large impact affected ecosystems and biodiversity at ground zero. Microfossils in the impact site sediment layers (Figure 3.10, right core photo) provided strong evidence for rapid recovery of life at ground zero: benthic and planktonic life reappeared in the basin just years after the impact, and a high-productivity ecosystem was established within 30,000 years (Lowery et al., 2018). Such findings demonstrated that proximity to the impact was not a control on biological recovery. Instead, natural ecological processes probably controlled the recovery of productivity after the Cretaceous–Paleogene mass extinction and are therefore likely to be important for the response of the ocean ecosystem to other rapid extinction events, such as climate-related changes in ocean chemistry that are impacting modern ocean health.

SOURCE: University of Texas Jackson School of Geosciences. (Right) Paleontological evidence of the recovery of planktic life at the impact site during the earliest Paleogene. Percent abundance of key planktic foraminifera groups are shown. Darker rock is a transitional unit, and the white rock is a pelagic limestone. P0 and Pα are tropical planktic foraminiferal biostratigraphic zones (PFZ) (Wade et al., 2011). Because many planktic foraminifera species originate at or near the base of Pα, it was concluded that the base of the limestone lies very near the base of this zone.

SOURCE: Lowery et al., 2018. Reproduced with permission from Springer Nature.

that plankton evolution and diversity have been paced by orbitally forced changes in climate and the carbon cycle over the last several million years (Woodhouse et al., 2023). Recent work on cores from the Southern Ocean has identified antiphased dust deposition and biological productivity over 1.5 myr (Weber et al., 2022).

Biogeochemical cycling can be tracked through time with sediment samples and data procured from scientific ocean drilling, as microfossils can indicate how past conditions impacted ocean conditions. For instance, investigations of changes in plankton community structure between warm and cold periods over the last 66 myr reveals that plankton were less abundant and diverse and lived much closer to the surface during warm periods (Crichton et al., 2023) (Figure 3.11). In contrast, during the long-term cooling trend of the Cenozoic, fossil evidence indicates increased plankton species diversity and greater export of detrital organic carbon to the deep ocean. These results are consistent with models on the vertical compression of habitats as the ocean warms and their expansion as the ocean cools (e.g., Crichton et al., 2023). This paleo-reconstructed relationship is significant because the biodiversity of plankton in the modern ocean is correlated to tuna, billfish, krill, squid, and other key fauna (Yasuhara et al., 2017), suggesting food web implications as the modern ocean continues to warm.

Planktic foraminifera are a major constituent of ocean floor sediments and thus provide one of the most complete fossil records of any organism. IODP-2 expeditions to sample these sediments have produced large amounts of spatiotemporal occurrence records throughout the Cenozoic. These scientific ocean drilling program data are the primary source of the newly established Triton database, which has been populated with more than 50,000 records of species-level occurrences of planktic foraminifera. The database can now be used to study how species responded to past climatic changes.

Relevant to the question of deoxygenation, over several decades scientific ocean drilling has recovered evidence of expansive ocean anoxia during the Cretaceous (80–120 Ma) when layers of the upper ocean lacked sufficient oxygen to support respiration or to remineralize detrital organic matter, which accumulated in thick layers known as black shales. More recently, biomarkers (molecular fossils) extracted from these shales demonstrate how organic carbon burial drivers, such as enhanced productivity and/or preservation, operated along a continuum in concert with microbial ecological changes. Localized increases in primary production can trigger marine microbial reorganization from the surface waters to the seafloor, and can destabilize carbon cycling, promoting progressive marine deoxygenation and ocean anoxia events (Connock et al., 2022). These Cretaceous ocean anoxia events lasted for hundreds of thousands of years and were likely triggered by excessive emissions of CO2 and nutrients (e.g., iron) associated with volcanism and massive extrusion of basalts (Figure 3.12). In contrast, during other warm periods, such as the Eocene or PETM for example, the OMZ appears to have been relatively well oxygenated with less denitrification (Kast et al., 2019). The reason for the contrasting conditions remains enigmatic but likely involves a combination of factors, including differences in the ocean circulation and mixing and overall nutrient inventory (Auderset et al., 2022).

Additionally, microfossil records documenting past ocean ecosystems and marine communities have been used to reconstruct ancient ocean structures and circulation in a range of settings and timescales, thus demonstrating how research on paleobiological components and research on paleoclimatic and paleoceanographic systems are interdependent. For example, during IODP-2, a 1.5-million-year-old northern Indian Ocean drilling core record, containing summer and winter planktic foraminifera microfossil assemblages, documented a climatically triggered large-scale reorganization of the Indian monsoon system at the time of the middle Pleistocene transition (i.e., the time when glacial–interglacial cycles became both more extreme and paced with a longer periodicity; Bhadra and Saraswat, 2022). On a deeper timescale, foraminifera depth habitat ecologies in an IODP-2 southern Indian Ocean drilling core record documented differential effects of a late Cretaceous CO2-driven global cooling transition on surface versus deeper water in the southern high latitudes, consistent with enhanced meridional circulation (Petrizzo et al., 2022). A final example draws on planktic foraminiferal assemblage data collected from legacy cores during IODP-2. Data from sites that transect the modern-day Kuroshio Current and Extension were used to reconstruct diversity curves within the regional western boundary current through the last 12 myr. Results point to potential causal links between diversity gradients and variations in the regional western boundary current associated with tectonically driven ocean gateway closure and paleoclimatic events affecting ocean thermal gradients (Lam and Leckie, 2020). Because “multidecadal variability of the strength and position of western boundary currents and short records from direct observations obscure the detection of any long-term trends” (Gulev et al., 2021,

SOURCE: Crichton et al., 2023.

SOURCE: Koppers and Coggon, 2020. Illustration by Rosalind Coggon and Geo Prose.

p. 357), scientific ocean drilling paleobiological work helps fill a gap in research on the marine ecosystem responses to climate and ocean change.

High-Priority Future Research

Ocean drilling has provided key insights into marine ecosystem responses to changes in past ocean and climate conditions, with potential implications for the future of ocean health in a rapidly warming world. However, a number of issues regarding the impacts of environmental extremes on past ocean ecology remain unresolved. Some can potentially be addressed with existing archives, but others require new data. One issue in particular is the question of habitability of the tropics, and threshold temperatures for phyto- and zooplankton. To address this, additional drilling is required to target the short-lived extremes in equatorial oceans, particularly along the continental margins, where (e.g., during the PETM) various groups of plankton (foraminifera and dinoflagellates) appear to have abandoned the surface ocean, reappearing only after temperatures cooled. Identifying an upper thermal limit or range for habitability of the tropical ocean during the past remains a high-priority challenge.

Similarly, there is still a need for additional examples in the paleo record to be uncovered that display how past plankton communities shifted poleward during times of past warming. The recent geographic ranges of marine organisms, including planktic foraminifera, diatoms, dinoflagellates, copepods, and fish, have been seen to shift poleward because of climate change. However, it remains unclear the extent to which the poleward move represents precursor signals that may lead to extinction. Additionally, some of these shifts are taking place in midlatitude ecotones, places where warm subtropical and cool subpolar waters meet, areas that also have some of the highest biodiversity in the world today (Tittensor et al., 2010). Therefore, subtropical to subpolar paleocommunities overlap

in need of investigation. A more in-depth understanding of the development of marine biodiversity patterns over time and space, and the influencing factors, is needed (Woodhouse et al., 2023).

CONCLUSION 3.3b Additional scientific ocean drilling that prioritizes locations with limited records, such as the equatorial, midlatitude, and polar oceans and open ocean environments during past periods of extreme warmth, will allow paleobiologists to inform models of plankton ecosystem dynamics during past analog climate states (e.g., rapid warming). In addition, existing long-term paleo records can be further exploited for studies, capitalizing on the development of new databases and existing core samples to assess global marine ecosystem responses to climatic and oceanic shifts more fully.

Monitoring and Assessing Geohazards

Providing data to more accurately forecast and assess future risks of earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, submarine landslides, and tsunamis.

Geohazards, including earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, landslides, and tsunamis, are a direct threat to human populations, with a record of harming people and damaging infrastructure, both in today’s world and throughout human history. Thus, better understanding geohazards benefited society fundamentally by enabling more accurate and timely forecasting and assessment of future risks.

Tsunamis, landslides, earthquakes, and volcanic eruptions all create signatures in ocean sediments that can be sampled by ocean drilling. Through scientific ocean drilling, long-term instruments have been installed and deployed in the subseafloor, and fluids, sediment, and rock cores have been collected to study geohazards.

Among Earth’s most hazardous tectonic environments are subduction zones, where one tectonic plate slides beneath another. These plate boundaries typically occur within or at the margin of ocean basins and are host to Earth’s largest-magnitude earthquakes and most explosive volcanic eruptions. Seafloor motion associated with these events can also generate devastating tsunamis that impact both local and distant communities. Not only do these hazards pose significant danger to human life, but individual events also cause monetary damage, often exceeding $100 billion (e.g., the 2011 Mw [moment magnitude] 9.1 Tōhoku-oki [Japan] earthquake and subsequent tsunami killed 20,000 people and caused $210 billion in damages [Ranghieri and Ishiwatari, 2014]). Quantifying the risks associated with these hazards and developing better metrics for predicting when they may occur are of key societal importance as coastal populations continue to grow throughout the 21st century (Reimann et al., 2023).

Improving understanding of geohazards requires data from both the past and present. Scientific ocean drilling can provide these data through (1) sedimentary records that provide constraints on the frequency and magnitude of past events, (2) direct sampling of rocks from fault zones or the slip plane of major landslides to determine the material properties of these features, and (3) real-time monitoring using borehole observatories. These datasets complement other ongoing National Science Foundation (NSF) initiatives studying geohazards, including the Ocean Observatories Initiative’s (OOI’s) Regional Cabled Array, offshore Washington and Oregon; the Subduction Zones in Four Dimensions (SZ4D) initiative to study subduction systems in Chile, Cascadia, and Alaska; and several recently funded Centers for Innovation and Community Engagement in Solid Earth Geohazards (e.g., Cascadia Region Earthquake Science Center, Center for Land Surface Hazards, Collaborative Center for Landslide Geohazards).

Seafloor records are often more complete than onshore sediment sequences, as they are not exposed to subaerial erosion processes. Importantly, these signatures can be used to infer the magnitude of past events. For example, ground shaking generated by large earthquakes can cause slope failures that produce sediment turbidite deposits. Sampling the spatial distribution of these turbidites can provide an estimate of the magnitude of the earthquake. This approach has been used to constrain the recurrence interval of very-large-magnitude (M8 and M9) earthquakes off the coast of Cascadia (e.g., Goldfinger et al., 2012). Similarly, the magnitude of volcanic eruptions can be inferred from the thickness and distribution of ash records (Kennett et al., 1977). Deep cores recovered through ocean drilling can provide an important record of the size and frequency of past geohazards, allowing local communities to prepare for future events.

Direct sampling of fault zone rocks allows these rocks to be probed experimentally in the laboratory to determine their material properties. The IODP Nankai Trough Seismogenic Zone Experiment (NanTroSEIZE) used this approach to constrain the conditions that lead to a transition between stable fault creep at low strain rates to dynamic weakening at high strain rates. Results from the NanTroSEIZE project showed that once a rupture initiates, dynamic weakening mechanisms can drive rupture propagation to very shallow depths, thereby enhancing the likelihood of tsunami generation (e.g., Ujiie and Kimura, 2014). Future studies at other subduction systems will allow scientists to probe the different conditions (e.g., fault zone composition, fluid pressure) that promote seismogenic versus stable aseismic creep. These data can in turn be used to constrain numerical models of dynamic fault ruptures, earthquake cycles, and tsunami genesis.

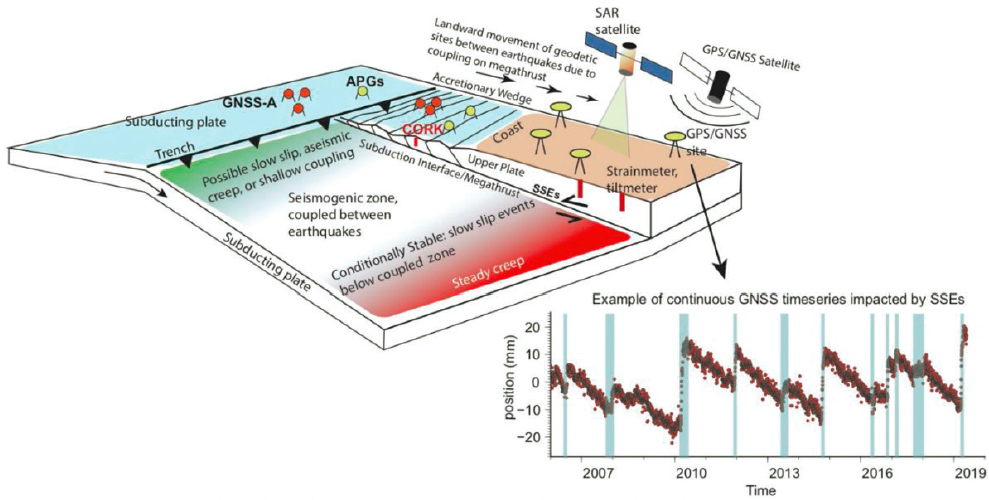

Scientific ocean drilling also enables the installation of borehole observatories, which measure in situ subsurface conditions. Physical properties such as crustal stress and strain, temperature, pore pressure, and fluid chemistry have been observed to vary throughout a hazard cycle; in certain cases, they have been linked to precursory activity prior to a major event. For example, periods of “slow” or aseismic slip and/or enhanced subsurface fluid flow have been observed to occur before some large (≥ M8) earthquakes. These transients are difficult to resolve using instruments deployed on land, often far from the feature of interest, or directly on the seafloor where bottom currents generate noise that obscures the signal. By contrast, borehole observatories installed at depth, near fault zones or on the flanks of seafloor volcanoes, have significantly higher sensitivity; for example, borehole sensors in the seafloor have an order of magnitude greater sensitivity than the pressure gauge sensors on the seafloor (Box 3.4). While it remains unclear under what conditions precursory events occur, the ability to predict hazards requires future studies to better understand these signals in diverse geologic settings. Borehole observatories are thus critical to advance basic research into hazard cycles. Moreover, connecting observatories to cabled arrays can provide real-time monitoring of subsurface conditions with the prospect of developing future early warning systems. As such, borehole observatories complement OOI’s Regional Cable Array off Cascadia and the aspirations of SZ4D to install similar infrastructure offshore of central Chile (Figure 3.13), which cannot be installed without scientific ocean drilling.

Progress Made During IODP-2

The IODP NanTroSEIZE project constrained the conditions that lead to a transition from stable fault creep at low strain rates to dynamic weakening at high strain rates (Box 3.5). Results from the NanTroSEIZE project showed that once a rupture initiates, dynamic weakening mechanisms can drive rupture propagation to very shallow depths, thereby enhancing the likelihood of tsunami generation (e.g., Ujiie and Kimura, 2014).

In the context of determining the controls on geologic hazards, a strategic objective of the IODP 2050 Science Framework was to better understand the nature of slip processes. Faults can slip gradually or catastrophically or exhibit unstable (time and magnitude) behaviors. In the last 10 years, major progress has been made in understanding slow-slip and tsunamigenic earthquakes, as a result of the NanTroSEIZE project and the installation of borehole observatories, highlighted in Box 3.5. The NanTroSEIZE project, and related studies in the Nankai accretionary prism and shallow subduction interface, have taken place over multiple IODP expeditions.

Other expeditions to active subduction zones included one to the Sumatra subduction zone system, where an M9.2 tsunamigenic earthquake in 2004 destroyed many coastal communities. The properties of the materials being subducted at plate boundaries can determine where and when megathrust earthquakes occur and influence earthquake magnitude and tsunami hazard. Some of the most devastating recent earthquakes have not been found to conform to expectations with respect to their magnitude and tsunamigenic properties. For example, the thickness of the sediments that are being subducted between the Indo-Australian plate around Sumatra were not expected to result in large-magnitude earthquakes or tsunamis during a megathrust event. Yet, in 2004, the massive Sumatra-Andaman earthquake and tsunami killed 250,000 people. IODP-2 drilling in this area recovered two cores (extending down to 1,500 m below the seafloor) to characterize the sediment and rock properties of the material that is being subducted by the Indo-Australian plate. Geochemical analyses of the cores revealed that freshwater release from the dehydration of biogenic silica and silicate minerals during heating of subducting sediments may be influencing the strength of the fault. Such a process may have driven shallow slip offshore of Sumatra and

SOURCE: Bartlow et al., 2021.

resulted in an increase in earthquake and tsunami size. These findings may be relevant for other subduction zones that exhibit similar sediment properties, such as Cascadia and the Eastern Aleutians.

Other IODP-2 contributions have focused on mechanisms that control the occurrence of submarine mass failures (landslides), which can trigger tsunamis, destroy marine infrastructure, and alter carbon cycling in marine sediments. Slope failure can be triggered by a variety of processes, including mechanical forcing (volcanic eruption, earthquakes, glacial-isostatic rebound), sea level change, rapid sedimentation, and fluid flow (e.g., gas hydrate dissociation). Uncovering the history of past regional submarine slides can aid in reconstructing the mechanisms of landslide initiation. Even submarine landslides around Antarctica could pose a tsunami risk to coastal communities in the Global South. It has been proposed that glacial–interglacial variations in sediment composition and sedimentation rates around the Antarctic continent could result in weak sediment layers that are more susceptible to landslides. The Iselin Bank, located in the eastern Ross Sea, sits on a passive margin (i.e., not near an active plate boundary). Seismic and chronological data obtained from IODP-2 drilling in this area showed that slope failure has occurred multiple times since at least ~15 Ma, and that weak sediment layers appear to be associated with three separate landslide events. The observed lithological contrast of distinctly sourced sediment layers (weak diatom-derived sediments with high compressibility versus high-density glacial deposits) is proposed to have been driven by climatic events, namely changes in the extent of ice cover in the Ross Sea. Although the climate-linked layering of sediments is thought to have decreased slope stability, the trigger for landslides at this location is linked to a possible increase in the frequency of earthquakes due to rapid local uplift associated with retreating glaciers. Future warming could recreate the conditions that resulted in slope failures in the past.

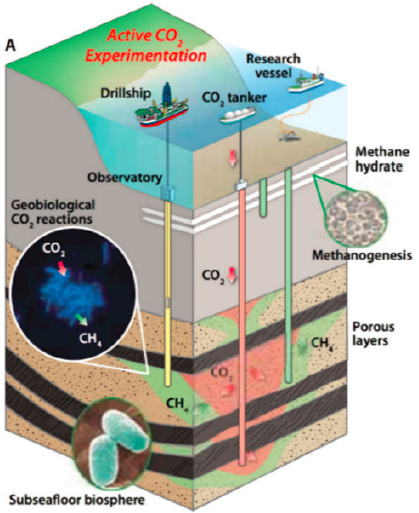

Scientific ocean drilling has also investigated the burial, storage, and cycling of carbon in ocean sediments, which has implications for understanding sources and sinks of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. Guaymas Basin is a young ocean spreading system in the Gulf of California that experiences very high sedimentation rates, which leads to a volcanically active rift basin blanketed by thick, organic-rich sediment layers. This unique combination results in magma-filled sills intruding into thick sediment sequences. These intrusions act as

BOX 3.4

Sensitivity of Earthquake Detection Using Borehole Observatories

Borehole instrument sensors, which can be installed only with scientific ocean drilling, are significantly more sensitive to subsurface fault slip movements compared with seafloor instrumentation, thus providing a higher resolution of data.

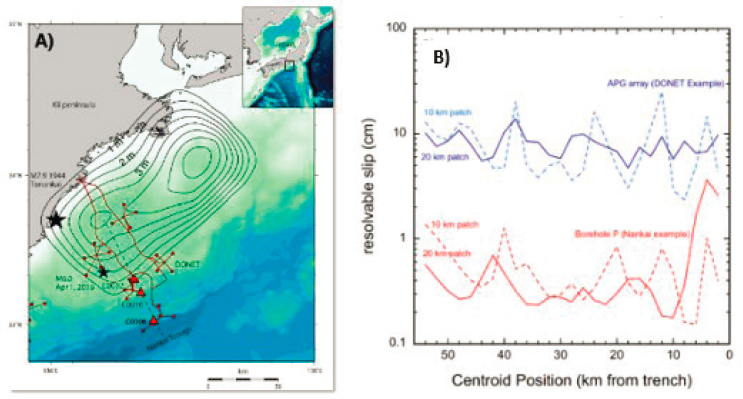

To evaluate the minimum amount of slip that can be resolved using seafloor instrumentation versus subsurface borehole instrumentation, this box includes a sensitivity test performed using a numerical model courtesy of Demian Saffer. This test compared the sensitivity of an array of eight absolute pressure gauges (APGs) to three borehole sensors. The configuration of the APGs was deployed on the seafloor at distances of 2–80 km from the trench, based on the Dense Ocean floor Network system for Earthquakes and Tsunamis (DONET) (Figure 3.14A). The three installed boreholes were within a similar distance from the trench but located much deeper under the seafloor (located 2 [C0006], 24 [C0010], and 35 [C0002] km from the trench at depths of 453, 409, and 980 m, respectively).

The numerical model (PyLITH) (Aagaard et al., 2022) incorporated realistic fault geometry, bathymetry, and variations in elastic moduli as determined by active source seismic and borehole data to simulate the response to an assumed amount of fault slip. The model simulation showed that given the noise levels associated with borehole versus seafloor sensors, the borehole sensors have the ability to resolve the fault slip <1 cm (red curve), while APGs were only capable of detecting the fault slip ≤10 cm, as shown in Figure 3.14B. When coupled with cabled observatories, borehole sensors can therefore provide significant improvement to real-time hazard assessments, including identification of slip transients leading up to major earthquakes and a more complete picture of strain accumulation and release through the earthquake cycle.

SOURCE: Figure adapted from Demian Saffer, University of Texas at Austin; map is from Araki et al., 2017. Reprinted with permission from the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

BOX 3.5

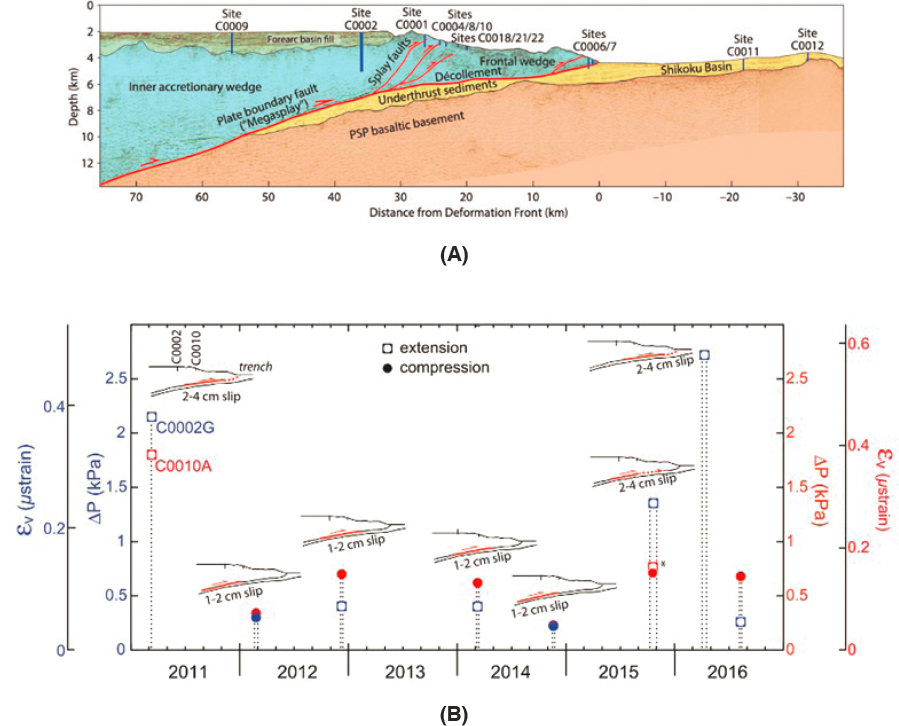

NanTroSEIZE: A Success Story

The Nankai Trough Seismogenic Zone Experiment (NanTroSEIZE) is a multiexpedition project by the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP-2) to investigate fault mechanics and seismogenesis (i.e., earthquake genesis) at a subduction megathrust fault zone in the Pacific Ocean near Japan. The Nankai Trough is formed as the Philippine Sea plate subducts beneath the Eurasian plate. The megathrust fault accommodates the differential motion between the two plates and has been the site of multiple earthquakes at magnitudes of 8 or more. Systematic drilling associated with 13 IODP expeditions has resulted in direct sampling of the fault zone, as well as in situ monitoring of this megathrust fault and of overlying splay faults in the accretionary wedge of sediments (Figure 3.15A).

Through this coordinated effort, NanTroSEIZE has led to several key advances in understanding subduction zone fault systems. Prior to the NanTroSEIZE program, it was generally thought that seismogenic fault slip rarely extended up to the seafloor (Tobin et al., 2019). However, recovered fault gouge showed a highly localized fault zone that preserves evidence of thermal anomalies associated with frictional heating. These observations indicated that the fault slip extended all the way to the seafloor near the trench, significantly increasing the potential for the generation of tsunamis.

Second, borehole observatories provided new insights into the accommodation of strain on the megathrust fault. These borehole sensors provide continuous records of strain, seismicity, pore fluid pressure, and temperature. By comparing transient strain events recorded at two observatories (Araki et al., 2017), researchers were able to identify slow-slip events between 2011 and 2016, each accommodating several centimeters of slip on the plate boundary (Figure 3.15B). Collectively, these events represent 30–50 percent of the total fault slip based on the far-field plate convergence rate. Thus, the NanTroSEIZE program has elucidated that the subduction megathrust behaves in a multimode fashion, hosting both seismogenic ruptures and slow slip at different times during an earthquake cycle.

(B) Summary of changes in pressure (ΔP) and strain (εv) measured at two boreholes (red and blue) near the Nankai trench off the coast of Japan. NOTES: Some motion was compressional (solid circles), while other motion was extensional (open squares). Dashed vertical lines indicate duration of each event. kPa = kilopascal. SOURCE: Araki et al., 2017. Reprinted with permission from the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

transient heat sources that drive off-axis hydrothermal circulation with the potential to release sedimentary carbon as methane. IODP-2 drilling in the Guaymas Basin investigated these processes and found that the sills not only provide the heat necessary to release hydrocarbons, but also act as chemical reaction zones sequestering some carbon into the sill matrix (IODP, 2019). Furthermore, the structure of young rift basins (i.e., individual rift segments with different elevation depocenters) controls the distribution of sediment deposition relative to variations in sea level. Additionally, drilling results from scientific ocean drilling in the Gulf of Corinth suggest greater carbon burial during interglacial periods, when deposition occurred under marine conditions, compared with glacial periods, when the basin was closed off from ocean. The mechanism relates to local controls of sea level on the carbon cycle: during warm interglacial periods, this location was below sea level and a better place for depositing and burying carbon. But during glacial periods, the sea level was lower, and it was a less productive, closed-off setting, which resulted in less carbon burial.

High-Priority Future Research