Mental Health, Wellness, and Resilience for Transit System Workers (2024)

Chapter: 3 Frontline Worker Experiences

CHAPTER 3

Frontline Worker Experiences

Introduction

Although agency leadership provided valuable feedback, there have been few efforts to directly engage with operators and frontline workers to understand their views, challenges, and solutions for improving their mental health, well-being, and resiliency. The aim was to gain a comprehensive understanding of their experiences and identify their specific needs within the transit industry. Two focus group sessions exclusively for frontline transit workers and a national survey encompassing a wide range of frontline transportation workers were conducted to gather information directly from workers on their mental health and well-being. These initiatives provided firsthand insights and perspectives from those directly involved in the field.

Frontline Worker Survey Findings

The frontline worker survey was conducted from February 9 through March 6, 2023. The goal of the survey was to better understand factors that affect the mental health and wellness of frontline transit workers and gather workers’ feedback on possible solutions to improve workplace mental health and resilience. The consent form and survey questions can be found in the survey questionnaire section of the Appendix. Eligibility for the survey included (1) being a frontline transportation worker (i.e., those who interact directly with the public as part of their job) and (2) working at a transportation agency located in the United States. Recruitment materials (i.e., email announcement and a flier with the survey link and QR code) were disseminated primarily through (1) transit agency management staff who participated in the interview portion of the study, (2) union representatives from various regions and states, and (3) other transit agencies’ management staff who expressed an interest and willingness to disseminate the survey to their frontline workers.

Through March 6, 2023, 1,139 survey responses were initiated. Of those, 84 were invalid responses, spam/bot responses (n = 26) and duplicate responses (n = 58), leaving 1,055 valid responses. Of those, 1,031 provided consent for survey completion. And of the consenting individuals, 155 did not qualify for the survey because either they were not a frontline worker (n = 129) or they discontinued the survey prior to answering any questions (n = 26). Additionally, 96 individuals were excluded due to missing over 90% of the survey responses (n = 96), and 3 individuals were excluded due to working outside of the United States. This yielded 777 survey responses with usable data.

Although this survey provides valuable information from hundreds of transit workers throughout the country, a healthy worker bias might be at play. This survey was aimed at workers who are actively on the job, so it may not provide sentiments from workers who have left the industry or the reasons they did so.

Data Analysis

All data cleaning and analyses were conducted in survey software. Embedded metrics were used to identify duplicate responses and “spam” or bot entries, which were removed from the dataset such that only valid cases were retained. All variables were reviewed for completeness of response, illogical consistencies, and outliers. There were no identified outliers. Cases with excessive incomplete answers (>90% of data missing) were excluded. Response patterns on a single survey item (i.e., total years of education completed) evidenced illogical inconsistencies and thus were not included in analyses. All dichotomous variables were dummy coded (0 = no, 1 = yes). The survey data were synthesized using descriptive analyses (means and frequencies) and inferential statistics (e.g., t-tests, chi-square tests, linear regression).

Due to the large sample size and number of exploratory analyses conducted, an ultra-conservative alpha was used in interpreting statistical significance (p ≤ .001). When a large number of analyses are conducted, the risk of a statistical significance being found due to chance and not because of an actual effect (i.e., false-positive findings) increases. An ultra-conservative p value was selected because it increases the confidence that the findings are true and not simply the result of chance.

Statistical Analysis Methods

Data and statistical tests are presented with the results, along with any correlations. Correlations examine how related two variables are to one another. An r value ranges from −1.0 to +1.0, where a negative value reflects an inverse association between the two variables (i.e., higher values in one variable are associated with lower values in the other variable) and a positive value reflects that higher values of one variable are associated with higher values of the other variable. R values of 0 reflect an absence of association between the variables. The strength of the association between two variables is generally considered small when the r value is 0.1–0.3, medium when the r value is 0.4–0.6, and larger when the r value is 0.7 or higher.

A t-test is a statistical test used to determine whether two groups differ in their average scores on a measure. The t-test statistic reflects the size of the difference between the two groups. A larger t value reflects that the difference between group means is greater than the pooled standard error, indicating a more significant difference between the groups.

A p value is a number calculated from a statistical test that describes the likelihood of a particular set of observations if there is no association or difference between variables (the null hypothesis). The smaller the p value, the more likely it is that the null hypothesis can be rejected. The p value is a proportion: If the p value is .05, then there is a 5% probability that the observed effect is attributable to chance. In the study, a p value of .001 was used, indicating a high level of certainty (99.9%) required to reject the null hypothesis and determine significance.

Workplace Conditions and Safety

Workplace Stress

When asked about the level of workplace stress on a 0–10 scale, with 10 representing the highest stress level, the average rating reported by frontline workers was a 7.0±2.3 (N = 777), which reflects elevated stress. Independent samples t-tests were conducted to examine whether there were group differences in the level of workplace stress by occupation (operator vs. other), race (Black vs. other), ethnicity (Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic), or gender (female vs. other); the results were nonsignificant.

Anxiety and Depression

The presence and severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms were assessed in question 8 with the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4), a well-validated, four-item self-report brief

screener. Items are rated on a 0–3 scale based on the frequency of occurrence in the past two weeks (0 = “not at all” to 3 = “nearly every day”). Two items assess anxiety symptoms (e.g., “feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge”) and two items assess depressive symptoms (e.g., “feeling down, depressed, or hopeless”), with a possible severity score ranging from 0–6 for anxiety and depression, where higher scores reflect more severe symptoms. A total summed subscale score greater than 3 suggests probable anxiety or depressive disorder. Based on the PHQ-4, 35.8% of the sample met the criteria for probable anxiety (mean severity score, M = 2.2±2.0; n = 756), and 27.2% of the sample met the criteria for probable depression (M = 1.8±1.9; n = 756). Independent samples t-tests were conducted to examine whether there were group differences in the level of anxiety and depression by occupation (operator vs. other), race (Black vs. other), ethnicity (Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic), or gender (female vs. other); the results were nonsignificant.

Workplace Stressors and Experiences

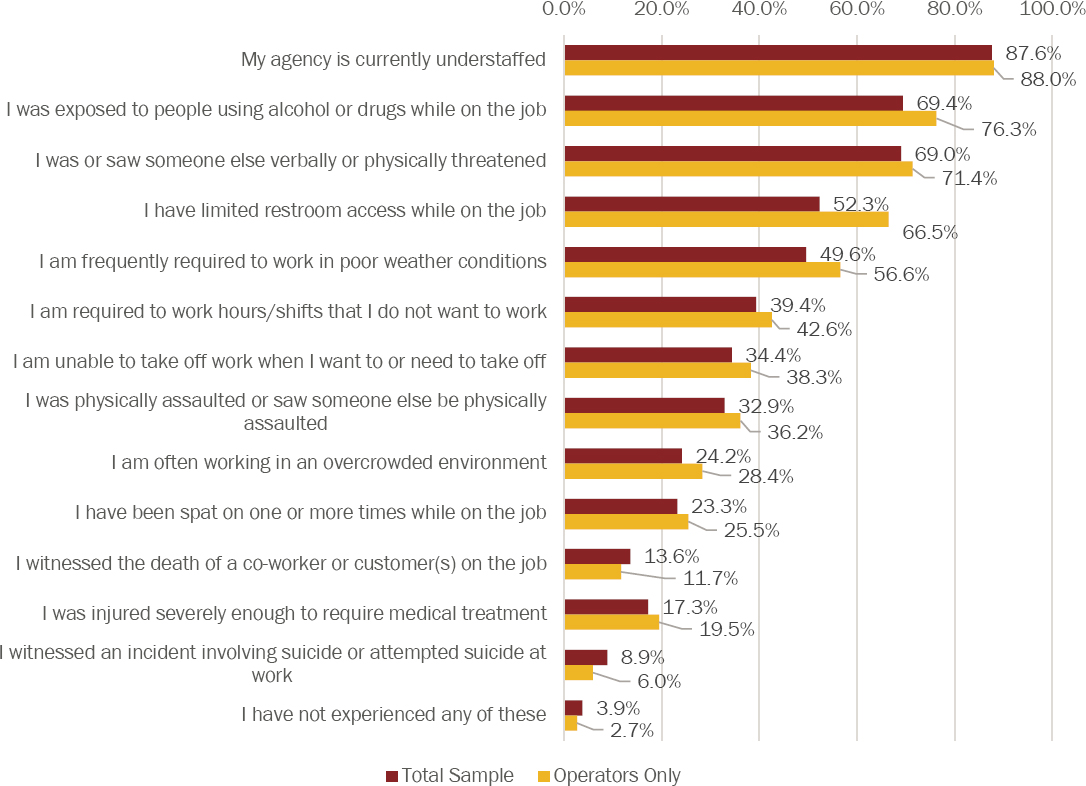

A list of various workplace stressors and experiences was developed based on the published literature in addition to worker and stakeholder input (Table A.10 and Figure 3.1). Respondents were instructed to indicate what stressors they had experienced while at work (“select all that apply”), with the option to select “none” if they had not experienced any of the events. On average, respondents experienced 5.2±3.0 of the 13 listed stressors (range = 0–13; n = 774). The number of workplace stressors reported was moderately correlated with the level of workplace stress, anxiety, and depression (r = .46–.47; p < .001). There was a small negative correlation between age and

anxiety severity (r = −.14; p < .001) and between age and depression severity (r = −.18; p < .001), which means as age goes up, anxiety and depression scores go down. While overall age was correlated with anxiety and depression levels, number of years working in the transit industry was not associated with workplace stress, anxiety, or depression severity.

Nearly all respondents (87.6%) reported that their agency was currently understaffed. In addition, more than two-thirds of respondents reported working in conditions where they (a) were exposed to people using alcohol or drugs (69.4%) and (b) were verbally or physically threatened or witnessed someone else being verbally or physically threatened (69.0%). A series of chi-square analyses were conducted to examine differences in endorsement of each workplace stressor by occupation (operator vs. other), race (Black vs. other), ethnicity (Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic), and gender (female vs. other). Compared to other genders, men were significantly more likely to report being physically assaulted/witnessing someone else be physically assaulted (40.2% vs. 25.0%, x2 = 16.50, p < .001). In addition, operators were significantly more likely than other transit occupations to report

- Having limited restroom access on the job (66.8% vs. 17.6%, x2 = 155.79, p < .001);

- Exposure to people using alcohol/drugs at work (76.7% vs. 52.0%, x2 = 46.34, p < .001);

- Working in poor weather conditions (57.0% vs. 32.2%, x2 = 39.45, p < .001);

- Working in an overcrowded environment (28.6% vs. 13.7%, x2 = 19.45, p < .001); and

- Being unable to take off when they need/want to (38.5% vs. 24.7%, x2 = 13.51, p < .001).

Additional Workplace Factors

Additional feedback reflected wider issues with workplace culture, such as the level of respect and empathy shown to colleagues and the ways in which colleagues communicate with each other. For example, one respondent wrote: “The biggest toll on my mental health is from dispatch and road supervisors. They bully the new drivers, dismiss our concerns with abusive passengers, yell at us, talk to us over the airwaves with hostile and demeaning tones, make negative personal comments when requiring a van with operational safety features (lights, turn signals, mirrors, etc.).” Additional emergent themes involved poor communication. For instance, one respondent raised concerns about lack of transparency about policies, as well as the need for “clear written policies and procedures that are consistently followed by management and that can be easily referenced.” Another respondent raised concerns about infrequent communication and lack of connection with the team and the need for more check-ins or meetings. This was highlighted through comments: “More communication and transparency lets the employee know what [sic] going on without hearing it from outside sources. . . . The biggest gap I feel within the transit agency is the lack of daily team/peer staff communication to debrief.”

Predictor Analyses

A series of multiple linear regression models were constructed to explore the association between workplace stressors with three outcomes: workplace stress, anxiety severity, and depression severity. Results are presented in Table A.11. The regression model results were significant, accounting for 25.8% of variance in workplace stress (F(13, 753) = 20.16, p < .001); 24.6% of variance in anxiety severity (F(13, 734) = 18.42, p < .001); and 24.1% of variance in depression severity (F(13, 734) = 17.91, p < .001). The workplace factors consistently and significantly associated with workplace stress, anxiety, and depression were

- Being verbally/physically threatened or seeing someone be verbally/physically threatened,

- Being often required to work hours/shifts that I do not want to work,

- Being unable to take off work when wanting/needing to, and

- Often working in an overcrowded environment.

Mental Health Resources

Access to Mental Health Resources

The extent to which frontline workers had access to mental health resources in their workplace was evaluated (Table A.12). More than half (59.3%, n = 461) of respondents reported that their agency offered mental health resources or programs to employees. Roughly one-third (31.3%) of frontline workers reported being unsure whether their agency offered mental health resources.

Utilization of Resources

Among respondents who reported having access to mental health resources at their agency, 20.6% (n = 95) reported utilizing the mental health resources available to them, which is 12.2% of the overall sample (Table A.13). An additional 11.9% of workers reported that they tried to utilize mental health resources at their agency but were unable to do so successfully. Among respondents who reported having no access or being unsure about access to mental health resources at their agency (n = 312), the majority (70.5%) indicated that they would consider using mental health resources if made available to them at their agency (Table A.14).

Satisfaction with Resources

All respondents were asked to rate their level of satisfaction with mental health resources available at their agency. On a 0–10 scale, with 10 representing the highest level of satisfaction, the average rating reported by frontline workers was a 4.50±3.0 (N = 735), which reflects moderate satisfaction. Satisfaction was lowest among frontline workers who reported no access to resources at their agency (M = 1.7±2.3, n = 69) and among those who were unsure about access (M = 3.0±2.64, n = 222), in addition to those who tried to use available resources but were unable to do so (M = 3.4±2.5, n = 54). Independent samples t-tests were conducted to examine whether there were group differences in levels of satisfaction with current resources by occupation (operator vs. other), race (Black vs. other), ethnicity (Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic), or gender (female vs. other). The only group difference observed was in terms of transit occupation: Operators reported significantly lower levels of satisfaction with mental health resources compared to other occupations (M = 4.2±2.9 vs. M = 5.2±3.0; t(732) = 4.08, p < .001).

Reasons for Not Using Mental Health Services Provided by Employer

A list of 13 barriers to using mental health resources was developed based on the published literature in addition to worker and stakeholder input (Table A.15). Respondents were instructed to indicate any reasons that would influence their decision to seek mental health support through their employer (“select all that apply”), with the option to write in “other” or select “none” if they did not believe any of the reasons would influence their decision or be a barrier to seeking services. Respondents reported an average of 2.9±2.7 reasons/barriers (range 0–13, n = 738). Independent samples t-tests were conducted to examine whether there were group differences in the number of reasons/barriers for using agency services by occupation (operator vs. other), race (Black vs. other), ethnicity (Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic), or gender (female vs. other); there were no significant group differences. The most commonly cited reasons affecting the decision to seek services through an employer were lack of time (35.9%), concern about missed pay (33.2%), privacy concerns (32.6%), and being too tired/exhausted (31.5%). Write-in feedback also reflected the need for increased access to community resources, such as “I think that more should be done to get health insurance [to] cover more” and “Recruit more counselors to take our agency’s medical insurance because we live in a small community, and we have limited choices.” A series of chi-square analyses were conducted to examine how reasons for not seeking services differed by occupational role (operator vs. other), race (Black vs. other), ethnicity (Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic), or gender (female vs. other). Operators were significantly more likely to endorse

concern about missed pay compared to other roles (40.5% vs. 22.3%, x2 = 22.14, p < .001). Men were significantly more likely to say they were unsure whether they needed mental health help compared to other genders (27.7% vs. 16.3%, x2 = 11.77, p < .001).

Predictor Analyses

A multiple linear regression model was constructed to examine which barriers to using agency services were the strongest predictors of satisfaction with available mental health resources. The results indicated that barriers accounted for 33.1% of the variance in satisfaction ratings (F(13, 695) = 26.43, p < .001). Four specific barriers were significantly associated with lower ratings of satisfaction:

- Unsure about how to access services or if they are available (β = −.27, t = −8.05, p < .001);

- Unsatisfied with resources available through employer (β = −.24, t = −6.68, p < .001);

- Limited availability of insurance coverage/cost (β = −.13, t = −3.70, p < .001); and

- Lack of compassion from manager (β = −.12, t = −3.29, p = .001).

Solutions

Preferences for Mental Health Services

There are many ways in which mental health services could be provided to frontline transportation workers. Several survey questions were used to assess preferences for communication about available mental health services (e.g., via email, website, flier), in addition to preferences for various aspects of mental health services. These aspects included the format of services (e.g., delivered one-on-one vs. in a group), the mode of accessing services (e.g., online vs. in person), and the timing of when services are provided (e.g., during work hours vs. outside of work hours). In response to each question, respondents were instructed to indicate their preferences (yes/no) with the option to indicate “no preference.” Regarding the format of mental health services (Table A.16), most frontline workers (63.6%) reported a preference for participating in mental health services one-on-one with a mental health professional. Those who reported privacy concerns as a reason for not seeking services from their agency were significantly more likely to prefer one-on-one services with a mental health professional (80.9%, x2 = 31.78, p < .001). Group-based and peer-led services were the least-preferred formats. In addition, more workers preferred to have in-person services accessed off-site (away from the workplace) (55.2%) compared to in-person services accessed on-site at the workplace (23.2%) (Table A.17). Workers were almost equally split in terms of preferences for having access to resources during work hours (38.6%), outside of work hours (36.8%), or no preference (33.1%) (Table A.18).

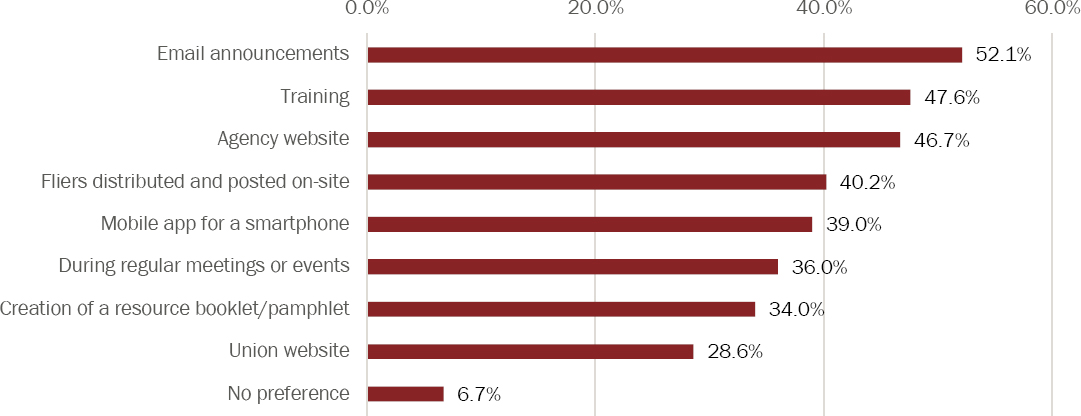

Most respondents preferred to be informed about available mental health services (Table A.19 and Figure 3.2) via email communication (52.1%), in training (47.6%), or via agency website (46.7%). Respondents endorsed an average of 3.2±2.4 different preferred communication approaches. One respondent emphasized: “Do more than just send out emails saying, ‘We have this EAP available for all employees.’ Have someone that administers the EAP/UAP [union assistance program] to actually visit onsite or even multiple online meetings to educate and share what realistically available resources are and answer any questions [like about privacy concerns].”

Ideas for Programs and Training

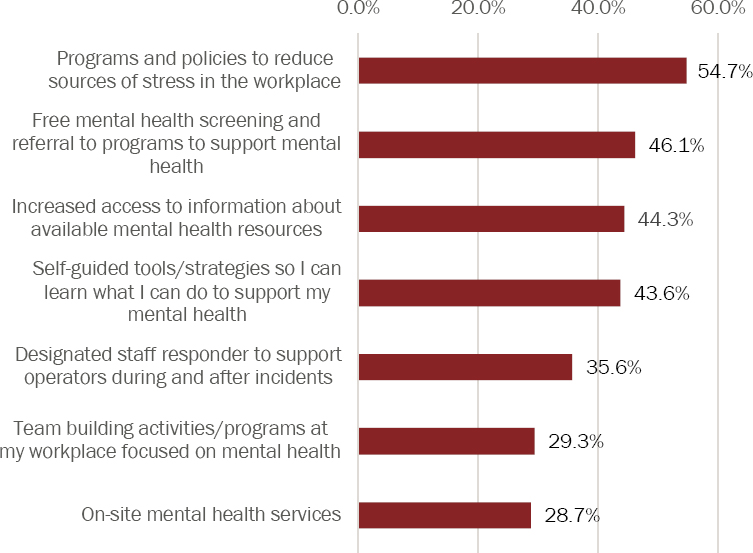

The survey included two questions designed to gauge respondents’ perception of how helpful various mental health programs and training programs would be if they were offered in the workplace. Respondents could indicate any programs or training that they thought would be most helpful (“select all that apply”), with the option to write in “other” or select “none” if they did not believe any programs/training listed would be helpful. Based on survey data, the top programs that participants felt would be helpful (Table A.20 and Figure 3.3) were programs and policies

to reduce sources of stress in the workplace (54.7%), free mental health screening and referral (46.1%), and increased access to information about available mental health resources (44.3%).

One respondent suggested offering trauma-specific programs: “I think we should offer counseling for people going through trauma at work and stress in the workplace.” Another respondent wrote, “When you are in a mental health crisis, it’s difficult to advocate for yourself. Sometimes you can’t do anything but survive. People need to have good connections and a mentor who can be of support. Possibly creating some sort of mental health buddy or sponsor relationship.” In support of mental health programs, one respondent emphasized, “I am glad my employer offers 8 sessions per incident. . . . I am willing to pay my $35 co-pay to be able to see my counselor once

a week. It makes me a better person which makes me a better employee to have a counselor to talk to about the stress of my job.” Other respondents said, “Mental health is just as important as physical health,” and programs “to support physical health and on-site fitness would be beneficial for relieving stress before and after work and this could help improve mental health overall as well.”

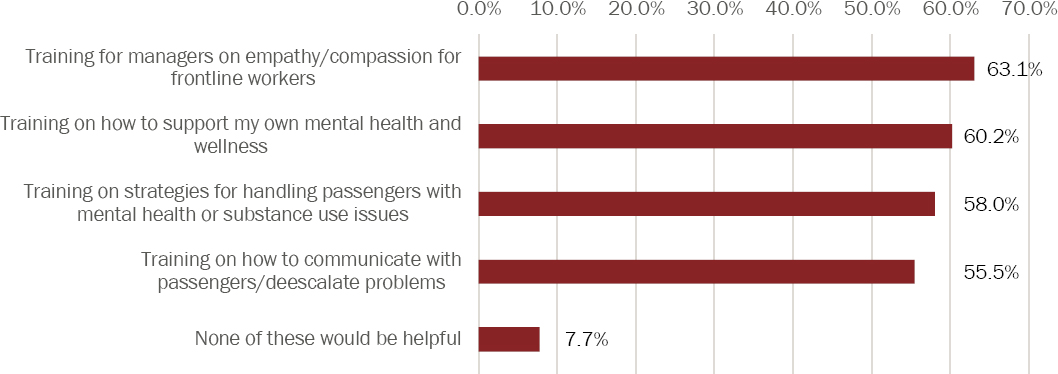

All four training program ideas that were presented were rated as “would be helpful” by more than half of the respondents (Table A.21 and Figure 3.4), with training for managers on empathy/compassion (63.1%) most frequently endorsed. Many respondents noted that everyone in the workforce, not just managers, would benefit from empathy/compassion training to ensure the whole agency is communicating with respect and compassion. An additional training idea suggested as a write-in option was training on naloxone delivery (administering naloxone to rapidly and temporarily reverse an opioid overdose). Respondents provided additional feedback on training, suggesting that mental health training be mandatory, offered during the workday (i.e., when workers are paid to attend), and presented in an interactive format (instead of a passive video format). These recommendations were emphasized as ways for leadership to demonstrate that they are prioritizing mental health and wellness. In addition, one respondent emphasized the importance of receiving training from someone who has firsthand experience in the transit industry: “I believe training is the best tool available to provide us with information to help deal with issues in our industry. To have someone from our industry who has done our work and has experienced some of these issues would be the ideal person to train us. We would be more apt to relate to someone who has been there, done that so to speak.”

Ideas for Policy Changes

The survey included one additional question in which respondents were asked to review 14 different policy changes and indicate which policies would support their mental health and wellness if implemented in the workplace. Respondents were able to “select all that apply,” with the option to write in “other” or select “none.” Three of the most frequently supported policy changes to support mental health were related to modifying the in-field experience by building more recovery or break time into transit timetables and improving access to restrooms and healthy foods during field work. A series of chi-square analyses were conducted to examine how policy changes differed by transit occupation (operator vs. other). Compared to other roles, operators were significantly more likely to endorse the helpfulness of policies related to scheduling and field work:

- Access to restrooms during field work (61.2% vs. 22.4%, x2 = 85.89, p < .001);

- More recovery/break time built into timetables (65.4% vs. 28.4%, x2 = 79.22, p < .001);

- Access to healthy foods during field work (55.3% vs. 38.8%, x2 = 15.51, p < .001);

- More in-field support (49.0% vs. 20.3%, x2 = 20.16, p < .001);

- Having a less variable work schedule (36.0% vs. 21.4%, x2 = 14.01, p < .001); and

- Time off on weekends/evenings (38.6% vs. 24.4%, x2 = 12.81, p < .001).

In addition, policies that provide more time off for mental health and wellness and provide free physical health and well-being check-ups were widely endorsed as helpful by respondents. Write-in responses frequently emphasized the importance of time off for mental health, such as having “a number of paid mental health days that we can take throughout the year” or “a once-a-year mental health offsite retreat staggered in assigned small groups with a qualified counselor or facilitator, teambuilding week, etc.” Workers’ responses reflected the importance of implementing paid time-off policies for mental health, as well as assurances that workers will be supported for taking this time and protected from retaliation if they choose to take it.

Additional Solutions Suggested by Survey Respondents

Respondents were provided the opportunity to write in any additional ideas for solutions to improve workplace mental health. There was an overwhelming emphasis on the need for enforceable policies for handling inappropriate passenger behavior and ensuring operator safety. Respondents noted that they are often “blam[ed] for the actions of others (i.e., we are blamed and disciplined for being assaulted) rather than the passengers being held responsible for their actions on the bus.” The need for clear and enforceable rules, which would make things less stressful for operators, was emphasized. For example, “If the rules state you can’t bring a shopping cart full of junk on the bus, then you don’t get to ride.” One respondent noted, “Operators should have the right to keep their passengers safe as well as themselves and not be faulted for passing up [patrons] who cause problems on the bus or who have threatened or assaulted themselves, other operators, and/or passengers.”

Finally, workers requested more focus on protection from harm (safety and security), especially as it relates to rider behavior. One respondent also suggested, “We need another trained individual to monitor and help with customer anger or mental health. This monitor should have the same schedule and have a radio to communicate with the police.” Others noted structural changes that involve having a protected area for operators. For example, “Enclosing the driver’s area [and] giving the driver a sense of security would go a really long way” or “installation of the protective doors to act as a layer of protection between the driver and the general public.”

Frontline Worker Focus Group Findings

Frontline transit workers were engaged through two focus group sessions to assess their experiences, challenges, stressors, and potential solutions to improve their mental health, wellness, and resiliency in the workplace. A total of seven people participated in each focus group session. Sessions were convened online and lasted 80 minutes and 60 minutes, respectively. The first focus group was held in October 2022 to gather information regarding the difficulties workers are facing. Session participants from this focus group were primarily frontline transit workers from three agencies, with two participants identifying as managers working with frontline workers. The second focus group was conducted in May 2023 to collect feedback on strategies to improve mental health and wellness and potential components of this report’s toolkit for transit agencies. This group was composed of seven frontline transit workers, each from a different transit agency. Focus group participants were recruited through the transit agencies interviewed for this report and through the frontline worker survey.

Quotes from Frontline Workers: Impacts of Personnel Shortages

“Our main objective is, you know, to try and keep everyone safe, but it’s kind of hard to do that when you don’t have too much [sic] people showing up at work or have enough units at work.”

Quotes from Frontline Workers: Lack of Breaks

“Oftentimes we have to make a choice whether we are going to drink some water real quick to keep hydrated and there’s not time to really eat.”

Quotes from Frontline Workers: Personal Safety

“It happens all the time. There are assaults and there are threats, many assaults, many threats. People have quit because of those things. And you really can’t blame them.”

Causes of Mental Health Stressors for Frontline Transit Workers

When asked about factors contributing to or causing stress or mental health problems for frontline workers, the following factors were mentioned:

- Operator shortages and other agency personnel shortages impact their work.

- There is a lack of agency focus in promoting work–life balance for frontline workers (e.g., mandatory shifts).

- The frequency of long runs makes it difficult to accommodate basic needs (e.g., restroom and food breaks) or to take calls during the workday to address personal and family needs.

- Frontline workers are concerned about personal safety and the unpredictability of threats (e.g., passenger assaults and how to handle passengers exhibiting mental health issues or unhoused passengers).

- There is constant pressure to maintain an on-time schedule while handling unexpected events and issues.

- The cost of living and inflation mean that workers are working more overtime to keep up.

- There is still concern about COVID-19, and it is difficult to take time off for any sickness due to staff shortages.

Participants shared their thoughts on the lack of work–life balance for operators. As one participant stated, an eight-hour off-shift begins when the operator pulls the bus into the garage, not when they arrive home. This means that once the operator arrives home, they have less than eight hours to sleep or rest before returning to work for their next shift. Others discussed difficulties associated with balancing work–life needs when forced to accept mandatory shifts with little or no notice. More consideration of frontline workers is needed from agency management regarding mandatory shifts since this practice causes great stress for workers, who often must struggle to arrange childcare or care for older family members on short notice. Some participants also shared that taking on a mandatory shift can necessitate canceling plans, including medical appointments scheduled months in advance, which often result in cancellation fees or other charges.

Lack of time to address personal matters or check in on family and young children during the workday was also discussed as a stressor. One participant explained that due to her agency’s no-distraction policy, her cellphone must be turned off during work hours. Thus, if she has a 15-minute break during a shift, she must check on her family during that brief time and try to complete any other personal business, such as scheduling doctor appointments. Participants were unanimous in their reporting of agencies infringing on personal vacation time. Many participants noted how although they receive dedicated sick time and vacation time, they are often not able to utilize those protected days since they must remain on call. The inability to take vacation or sick days without rest from work can have detrimental effects on the mental health of transit workers. As one participant noted, “My peace of mind is more important than a paycheck.” Participants recommended that transit agencies implement policy changes to ensure workers can take full advantage of protected days of rest.

Another participant explained that work stress could begin at the start of their shift when they realize they are departing the garage with a “faulty bus,” such as a vehicle with heating or air-conditioning problems. Their stress escalates as the shift progresses because they must handle difficult passengers and sometimes wait for supervisor assistance. Overall, they feel a lack of control at work due to these stressful factors and feel that “nobody takes accountability for it.”

One participant reported that their agency used to utilize standby or report operators to help cover shifts and assist with customer service issues during operator shortages. This policy contributes to better workflow and less “exhaustion” among operators in the field. However, this practice is no longer utilized due to staff shortages and agency reluctance to pay overtime salaries. The participant added that the proactive management approach of employing standby operators would help a transit agency function in a “proactive instead of a reactive” manner.

Another participant working in law enforcement for their agency added that understaffing makes it difficult to respond quickly to emergency situations. They explained that their agency’s practice is for officers to take passengers exhibiting mental health problems on board vehicles to a local hospital. They noted that the time the responding officer takes to travel to and from the hospital contributes to further staff shortages during a given shift.

Passenger behavior is a common contributing factor to poor mental health among operators. There was also much discussion of the stress caused by interacting with passengers exhibiting mental health issues and unhoused passengers. Several participants shared that passengers with mental health issues exhibiting problem behaviors are often not taking their medications. Some commented that many of their peer operators have quit from having to address issues with challenging, and sometimes dangerous, passengers.

Several participants observed that many unhoused passengers seek to travel by bus or rail throughout the day and evening to avoid inclement weather conditions. As a result, operators can have difficulty asking these individuals to disembark at the end of a run. Participants added that they sometimes must wait for supervisor assistance in dealing with difficult passengers.

Another source of stress for frontline workers is interacting with people under the influence of drugs or alcohol. As one participant shared, sometimes they must deal with passengers smoking drugs on the bus. The resulting smoke causes the operator and fellow passengers to exhibit signs of physical illness, so they must stop the bus when this occurs to open windows and doors to air the vehicle out.

Participants were asked how facing these diverse workplace stressors impacts their mental health, well-being, and ability to perform their job. Comments focused on feelings of fear, anger, and sadness, and sometimes symptoms of physical illness. In discussing feelings about passengers experiencing mental health disorders, homelessness, or drug addiction, one participant noted frequently feeling compassion for such passengers, as well as anger and sadness for the lack of societal support these individuals receive. Simultaneously, they recognize these passengers are often “the ones that assault us, you know, they cause all the problems on our buses, not only us but assault other passengers, the elderly, young girls.”

Trying to determine how to best address difficult passenger behaviors makes their job complicated and stressful. Participants explained that the job of a frontline worker is all-encompassing, requiring them to react to and handle internal factors onboard—as well as challenges in the external environment, including pedestrian and bicycle traffic and jaywalkers—all while arriving at their destination safely and on time. As they reported, “We are also babysitters, day care providers, and you know, we’re everything, we do everything on the bus to make sure everybody’s safe.”

Finally, ongoing stressors related to the COVID-19 pandemic contribute to poor mental health and wellness. Participants shared that the transit sector was “hit hard” by COVID-19 initially, with many workers passing from the illness over the first two years of the pandemic. While the pandemic has ebbed and vaccinations are available, COVID-19 remains a concern among participants in terms of sick time, personal wellness, and the wellness of their families.

Workplace Culture, Personal Safety, Resource Availability, and Other Barriers Related to Frontline Worker Mental Health

Workplace culture and messaging surrounding frontline worker mental health were also discussed at both focus group sessions. As one participant stated, “They tell us to stay safe, and my job, I’m on the train, but there is no part of it where you can because there have been times when you have someone causing altercations and issues on the train and they [management] want you to go see about them.” The participant explained that the message from agency management is that operators should seek to resolve onboard issues independently, if possible, but they do not feel safe doing so. They offered the example of needing to have all passengers disembark when their train goes out of service. Some unhoused or other passengers do not want to disembark, and while there is sometimes a police officer available to help secure compliance, this is not always the case. One participant noted, and several agreed, that agencies “care more about hiring than the mental health of their drivers.”

Most participants perceived a general lack of understanding from agency leadership about the difficulties that frontline workers face. This lack of understanding can result in policy decisions that ignore the stressors that frontline workers face and can ultimately be detrimental. To address the gap in understanding and to foster empathy among management, many focus group participants suggested implementing a program where senior management shadows an operator for a full shift. This exposure to the daily life of a frontline worker can help build empathy, understanding, and relationships between frontline workers and management. It can also create an opportunity for frontline workers to describe the stressors they face in real time to provide management with a much deeper understanding. A ride-along program would allow management to listen and learn directly from their frontline staff so they can actively seek to remediate challenges.

Others said that while COVID-19 remains a concern, their agencies are no longer offering COVID-19-specific time off, which poses a problem of spreading the virus if the employee has no additional sick days remaining. Participants explained that issues related to sick time for COVID-19 cause them stress, and senior management does not seem to recognize or understand that concern. And as one participant explained their feelings about COVID-19 transmission, “If you work in transportation, nine times out of ten that is where you caught it from.”

Regarding workplace mental health resources, several participants shared that EAPs are available. As one expressed, “it can be helpful,” but she added that many do not have time to seek out those services due to the daily stressors of their job. Also regarding EAPs, another shared that “they [management] talked about EAPs during orientation, but you don’t hear anything else about it after that.” In discussing how employees are made aware of mental health resources or programs, several shared they are informed by internal work emails, fliers or bulletins posted around the agency, correspondence from the HR department, and word of mouth from peers.

Participants discussed whether awareness of their agency’s mental health resources or programs was widespread among their peer frontline workers and if lack of awareness was a barrier to accessing support and services. One participant noted that their coworkers should be aware of these offerings, since the information is shared during the job orientation and via internal emails. Another responded that some of their peers only become aware of these resources if they need to seek them out. The group also briefly touched on the stigma surrounding mental health issues, with some noting that it can be difficult to bring up these topics. However, this can sometimes be made easier when workers can discuss one-on-one with another employee or in a small-group setting.

Another barrier mentioned relates to the continuity of mental healthcare and support. For example, a participant explained that following their involvement in a workplace accident that included death, they went through their agency’s EAP for counseling sessions. However, the counselor did not have expertise in the treatment of PTSD. After the allocated maximum number

of sessions, they needed more therapy but had difficulty identifying a mental health professional who (1) had flexible hours to accommodate their shift work schedule and (2) had expertise in treating PTSD. The participant acknowledged that the shortages in mental health resources are a problem nationally, in part due to the COVID-19 pandemic; while this is not specific to transit workers, it is an additional issue the workforce faces.

Strategies to Improve Frontline Workers’ Mental Health

Participants also discussed strategies to improve frontline transit workers’ mental health and well-being. While focus group facilitators shifted the conversation to identifying strategies to better support frontline workers, participants continued to share the stressors they face daily. Several specified that female frontline workers often face more distressing workplace situations compared to their male counterparts. Overall, the group participants were extremely frustrated and discouraged by the challenging workplace conditions they face daily, especially those that affect their personal safety in interacting with customers and other members of the public.

As mentioned previously, several participants shared that programs offering one-on-one or small-group support can be particularly beneficial and may help reduce the stigma related to seeking assistance. One participant, a manager, shared an experience in which they convened a small group of operators for a post-incident discussion following a colleague’s death by suicide. The purpose of the meeting was to check in on a personal or more “human” level beyond procedural or work-related regulations. They were surprised when two other participants in the session openly shared that they had experienced suicidal feelings due to work stress. The participant explained that the comradery engendered by discussing this topic in a trusted, small-group environment was helpful to these frontline workers, and it gave them an opportunity to raise their own mental health issues and learn about available resources.

Another participant shared that everyone needs someone to listen to their concerns and issues at work. They tried to help meet that need at their agency through their mentorship initiative and noted the importance of regularly “checking in on people.” They added that “there’s a lot of people that come in smiling that are really crying on the inside.”

Other strategies, ideas, or initiatives recommended by the group to support frontline worker mental health are included in the following list.

- Offer topical training during operator orientation. This training should be provided by a mental health professional and designed to assist operators in learning how to best handle passengers with mental illnesses exhibiting problematic behavior onboard.

- Offer training for supervisors focused on empathy and sensitivity. This training should focus on educating frontline supervisors on how to support the mental health and well-being of frontline workers and how to exhibit more empathetic, compassionate, and supportive leadership.

- Offer mentorship opportunities for both operators and supervisors. Mentoring opportunities can contribute to the overall wellness and mental health resiliency of the transit workforce and can also help supervisors become more sensitive to operators’ needs. One participant shared that their agency is considering implementing a supervisor mentorship program.

- Develop a professional operator peer-support team. In this initiative, mental health professionals would provide specific training to designated agency personnel so that the personnel could provide critical incident support to operators following accidents or other work-related incidents. A participant noted that their city’s police department has successfully implemented this type of program, and they have been seeking to establish a similar program at their transit agency. They emphasized that the program would focus on trained personnel functioning as the first line of support to an operator who experiences an incident—a team member would

- Offer and promote operator counseling. Participants in the focus groups agreed that counseling can be very helpful to frontline workers. One participant shared that their agency offers eight free sessions to operators alone or with their family members. The group noted the importance of health insurance at least partially covering these services. Several participants noted the benefit of offering these services off-site to promote confidentiality.

- Include a staff counselor on-site. An on-site mental health professional, whether part-time or full-time, would provide frontline workers with more access to services.

- Develop an engagement committee to promote camaraderie. Participants cited camaraderie among workers as an important means to support each other. An engagement committee can provide an outlet for workers to celebrate each other and to voice the difficulties they face with others who may understand and can provide guidance or comfort. One participant reported that her agency will often hold potluck meals to “celebrate anything that we can,” such as birthdays and other employee life events. She noted these efforts offer a low-cost strategy to help build camaraderie among workers.

help the operator get home post-incident and assist with completing paperwork and other requirements related to the incident, such as blood and urinalysis testing. The team member would also inform the operator of EAP services and other initiatives that may be helpful. Overall, they explained that this type of program “shows support, shows we care.”

Empathy training for supervisors, as described previously, was a suggestion the group strongly supported. Several participants shared personal stories and examples of instances when supervisors did not exhibit appropriate empathetic behavior toward a frontline worker. For example, when a driver is notified during a shift that someone close to them has passed away, some supervisors suggest the operator continue working their shift.

In contrast, another participant gave an example of how an empathetic supervisor can help a frontline worker recover after an incident. They shared their experience of going on-site as a supervisor to assist an operator who had just experienced a passenger harassment encounter. The operator was crying, and the participant explained how they acknowledged the operator’s feelings, showing compassion as the two of them discussed the incident. Following their conversation, the operator felt comfortable to “continue on” and decided to complete their shift, even though they were given a choice to stop working. The participant emphasized that sometimes operators feel they cannot continue their shift following an incident, and supervisors need to be supportive of those decisions.

Another key takeaway was the need for and value of increased agency support to help frontline transit workers navigate accident and assault incidents, with both on-site and post-event support and guidance. Regarding post-event support, one participant shared how they suffered mental health issues following an accident on board their vehicle that resulted in a death. They discussed the difficulty in returning to work post-event: “That’s also another part of our job that we have to deal with, because then we have to come back to work like nothing happened, you know?”

Those offering post-incident support to frontline workers should be aware of available mental health resources so that they can communicate those options to workers in need. When asked if volunteers could fill these post-incident support roles, the group responded strongly in the negative—paid professional support should be utilized, as even workers interested in serving as volunteers would not have adequate time to offer the needed support. One participant shared that there could be a role for peer volunteers to offer fellow operators support in times of need; however, the time demands would have to be very limited to successfully recruit and retain a volunteer base. For example, structuring the program with volunteer shifts, such as one day a month, might work. In addition, the role of a volunteer would only appeal to certain people. As the participant explained, “To do it voluntarily, you would be doing it from the heart.”

Participants also provided potential strategies to protect employees against threats of harm, which was cited as the biggest concern among many. Several acknowledged that macrosocietal

issues greatly influence their experience as frontline workers, such as limited federal, state, and local policies as well as a lack of resources to support members of the public coping with mental illness or housing stability issues. One participant remarked that programs to build employee camaraderie were not valuable and would not generate sustained improvement of transit frontline worker mental health. Instead, he reported that transit agency leadership and government need to devote funds to address mental health and housing issues. Some key suggestions to protect frontline workers against harm are included in the following list.

- Implement programs to expand management’s understanding of frontline worker issues. For example, agencies could implement a program that requires senior management to ride the bus or train with an operator for a full shift or a full day so that management acquires firsthand experience regarding the work life of an operator.

- Increase security officer or personnel presence in the field as a strategy to protect operators. Increased security or police could be targeted at routes, transit lines, or stations with a higher number of safety incidents, assaults, or confrontations. Security officers can perform fare enforcement and address any issues on board related to passenger conduct.

- Erect safety features, including physical barrier protections or enclosures between passengers and operators to protect operators. Several participants noted that their agency had erected these enclosures and they have contributed to operator safety.

- Enforce existing agency policies related to passenger codes of conduct designed to protect frontline workers. The group strongly expressed that their agencies and local law enforcement too often do not enforce existing policies to protect workers.

- Engage in an ongoing dialogue with local law enforcement and the prosecutor’s office. Discussing strategies to enforce laws and policies designed to protect transit operators from being harmed by members of the public could help address enforcement concerns. Further, the group suggested that agency law enforcement be instructed to enforce passenger codes of conduct and be trained in addressing issues with passengers experiencing mental health issues.

- Expand communications with the riding public on the role of frontline transit workers in helping to meet community transportation needs. This could include installation of signage throughout buses and trains that inform passengers of the legal and financial consequences of engaging in operator assault or harassment. Bus and rail audio announcement systems could also be used to communicate the legal and financial consequences of engaging in operator assault or harassment.

- Improve lighting at bus depots to better protect operators who use these facilities daily. One participant shared that unhoused persons have been sleeping at transit stops, raising safety concerns among operators. Focus group participants believe that local law enforcement has not been helpful in remediating the situation, despite repeated requests for their involvement.

- Provide post-incident support for frontline workers. One participant shared that he was never offered peer support following any of the three assaults he experienced on the job, despite his agency’s policy of providing such support.

Key Takeaways from Frontline Worker Engagement

Focus group participants eagerly and openly shared their experiences. They discussed various factors that contribute to or cause stress and mental health problems for frontline transit workers; the messaging they receive from their workplace regarding worker mental health; the available resources at work to support their mental well-being; how they become aware of these resources; barriers to accessing resources; and suggested strategies to enhance the mental health and overall well-being of frontline workers.

The national survey of frontline workers further validated these individuals’ experiences, providing data that highlighted their shared experiences. The survey revealed consistent patterns concerning the factors that contribute to or cause stress and mental health problems. It showed evidence of anxiety and depression among frontline workers nationwide, echoing many of the issues expressed by the focus group participants.

The following list summarizes key takeaways from both the focus groups and the national survey of frontline workers.

- Frontline workers are experiencing elevated anxiety and depression at work. Frontline transit workers reported high levels of workplace stress. Over one-third (35.8%) of survey respondents met the criteria for probable anxiety and 27.2% for probable depression.

- Operator and other staff shortages were cited as a major factor contributing to stress in the workplace. This issue was validated in the workplace stressors section of the national survey, where nearly all respondents (87.3%) reported that their agency was currently understaffed. Focus group participants noted high stress levels due to workplace conditions and staffing shortages.

- Nearly all (97%) of national survey respondents reported experiencing negative workplace conditions. On average, workers were exposed to several different negative workplace conditions, most commonly (1) working at an understaffed agency (87.3%), (2) being exposed to people using alcohol or drugs while on the job (69.1%), and (3) being verbally or physically threatened or witnessing it (68.7%). Focus group participants expressed personal safety concerns (e.g., constant hypervigilance and uncertainty) related to passengers, primarily those exhibiting mental illness symptoms, unhoused passengers, and passengers under the influence. Focus group and survey respondents brought up difficulties regarding the frequency of long runs that result in inadequate restroom, eating, and other break times; 66.8% of operators who were survey respondents reported having limited restroom access on the job as a stressor.

- A multifaceted approach to communicating and marketing mental health resources is ideal. On average, workers most often preferred to be informed about available mental health services by email (52.1%), at a training (47.6%), and via agency website (46.7%). A combination of passive communication strategies (e.g., posting on an internal website for employees to read) and active strategies (e.g., being told by a supervisor or trainer) would enhance awareness of available resources and optimize uptake. Focus group participants also shared various ways they have learned about the mental health resources available to them, primarily citing agencywide emails; flyers/bulletins; correspondence from HR, particularly during orientation; and word of mouth from peers. In discussing resources, mixed feelings were expressed about EAPs, with some noting these services can be helpful and others not as supportive. Barriers to mental health services can include a lack of awareness and issues related to continuity of service, such as limited counseling sessions.

Finally, the following strategies were recommended to improve the mental health of frontline workers.

- Agency policy–related changes would improve employee wellness. Focus group participants often felt they did not have adequate support from management regarding their mental health, particularly during and after incidents. The top-rated policy change recommendations to support mental health involved modifying the in-field experience by building more recovery or break time into transit timetables (48.8%) and improving access to restrooms and healthy foods during field work (45%), as well as increasing time off for mental health (48.1%) (Table A.22). Participants also said that even when time off is provided, it is not always respected by management, and being on call can cause serious stress. Adequate protection of paid time off or sick time is a vital agency policy–related change to ensure operators can rest. Enforceable policies for handling inappropriate passenger behavior and ensuring operator safety are also needed. Focus group

- Training programs were also widely endorsed as beneficial for improving employee mental health. Roughly 60% of workers noted that training for building empathy and compassion in the workplace would be beneficial, as well as trainings for employees on how to support their mental health and how to handle passengers with mental health or substance use issues. Training on the delivery of naloxone (opioid overdose reversal drug) was also suggested in both the survey and focus group. Respondents shared a preference for training delivery to be mandatory, offered during work hours (paid), and designed in an interactive manner. Focus group participants expressed interest in empathy training for supervisors so they can better support frontline workers experiencing mental health stressors and issues. Participants also showed interest in increasing the availability of operator counseling and mentorship opportunities for frontline workers and supervisors.

- Stress-reduction programs and programs increasing access to and awareness of mental health services were highly rated. The programs rated as the most helpful solutions were those focused on reducing sources of stress in the workplace (54.7%), free screening and referral to mental health services (46.1%), and increasing access to information about mental health resources (44.3%). While access to mental health services is important in any workplace, it is essential for frontline transit workers due to their high levels of stress and exposure to violent incidents and accidents.

- Frontline workers need greater support in the field, particularly after incidents. Many frontline workers are on their own most of the time, which can be isolating and lonely. They are often left to handle situations and conflicts on their own, which can be especially stressful for newer employees. Some strategies to address the lack of support include the implementation of staff trained in incidence response, such as critical response teams. When probed on types of mental health programs or wellness services that would be most helpful if offered in the workplace, 35.6% of survey respondents preferred designated staff to support operators after incidents. Ongoing support is also needed following incidents to ensure that frontline workers recover and can return to work without additional adverse impacts on their or others’ well-being. Some focus group participants suggested a program in which security officers or personnel travel aboard vulnerable bus routes as a strategy to protect operators.

- Increase privacy by offering one-on-one and small-group options for support and other services. Several focus group participants advised that programs offering one-on-one or small-group support can be particularly attractive and beneficial to frontline workers, and they may help reduce stigma concerns related to seeking assistance.

participants showed interest in the development of a professional support team to offer on-site and post-incident support to frontline workers.