Mental Health, Wellness, and Resilience for Transit System Workers (2024)

Chapter: 6 Toolkit

CHAPTER 6

Toolkit

Introduction

This toolkit reflects best practices identified through engagement with frontline workers and agency leadership from various transit agencies nationwide. Frontline transit workers shared the wide array of difficulties they face on the job and described the mental health programs they believed would best support them. Focus groups of transit workers and agency leadership also provided insight into the best format for this toolkit.

The toolkit provides guidance for enhancing existing mental health and wellness programs and for implementing new ones, with a range of formats tailored to the specific type of improvement or program (e.g., narratives, worksheets, checklists, frameworks, and step-by-step guides). The toolkit also provides research on the overall business value of establishing mental health and wellness programs for frontline workers, which can support efforts to identify dedicated resources to fund these initiatives. The primary aim of this toolkit is to assist agencies in supporting their frontline workers by facilitating the development and delivery of effective mental health and wellness programs.

How to Use This Toolkit

Table 6.1 is meant to help you navigate this toolkit. First, read the key issue statements, and identify those that resonate with your agency. One or more toolkit components are identified for each key issue statement. Read the descriptions and issues addressed, and click on the desired component to jump to that section of the toolkit.

Table 6.1. Toolkit components.

| Key Issue Statement | Toolkit Component* | Issues Addressed | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| My transit agency is unsure if our employee assistance program (EAP) offerings are adequate, unsure how often the offerings are used, or both. | Program Evaluation | Evaluating program performance or effectiveness. | This section includes a framework for how agencies can create procedures for program evaluation. |

| Evaluating and Improving EAPs and Union Assistance Programs | Increasing mental health and wellness offerings. | This section includes detailed worksheets (Tables 6.3, 6.4, 6.5, and 6.6) with probing questions to help transit agencies and unions document their current processes related to assistance programs and assess and identify opportunities to enhance them. |

| Key Issue Statement | Toolkit Component* | Issues Addressed | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| My agency has existing mental health and wellness programs, but we are unsure how effective they are. | Program Evaluation | Evaluating program performance or effectiveness. | This section includes a framework for how agencies can create procedures for program evaluation. |

| My agency is interested in expanding the mental health and wellness resources available to our frontline workers. | Establishing Wellness Program | Increasing mental health and wellness offerings. | This section includes information about wellness program components, steps for establishing a wellness program, and other considerations for building an effective wellness program targeting frontline workers. |

| Evaluating and Improving EAPs and Union Assistance Programs | Increasing mental health and wellness offerings. | This section includes detailed worksheets (Tables 6.3, 6.4, 6.5, and 6.6) with probing questions to help transit agencies and unions document their current processes related to assistance programs and assess and identify opportunities to enhance them. | |

| Increasing Training Offerings | Increasing mental health and wellness offerings. Building trust and empathy. |

This section identifies three types of trainings that frontline workers or their managers and supervisors identified as useful for coping better with certain on-the-job situations. | |

| My agency struggles to communicate with our frontline workers about mental health and wellness resources. | Support Mental Health in the Workplace: Checklist for Leadership and Senior Managers | Improving communications about mental health in the workplace. Building trust and empathy. |

This checklist provides a tool for agency leadership, union leaders, and those who manage frontline workers directly to better understand worker needs and communicate with them about mental health. |

| Improving Communications and Marketing of Resources | Increasing awareness of resources. Increasing program participant retention. |

This section addresses findings that frontline workers often feel uninformed about mental health resources by providing guidance on communicating and marketing these resources. | |

| Increasing Training Offerings | Better preparing employees for their work environment. Training managers on empathy/compassion for frontline workers. Increasing mental health and wellness offerings. Building trust and empathy. |

This section identifies three types of trainings that frontline workers or their managers and supervisors identified as useful for coping better with certain on-the-job situations. |

| Key Issue Statement | Toolkit Component* | Issues Addressed | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| I have an idea for a new or modified program or policy to improve the mental health or wellness of frontline workers, but I do not know how to implement it. | How to Make the Case for Increased Benefits to Support Mental Health and Wellness | Increasing mental health and wellness offerings. Funding and implementing a program. |

This section includes directions for agency staff on how to communicate the value of increased employee benefits to agency leadership. |

| Building Trust between Parties | Building trust and empathy. Promoting empathetic management. |

This section details a three-step process for building supportive, positive relationships and increasing trust between agency leadership, union leadership, and frontline transit workers. | |

| My agency’s frontline workers distrust leadership and feel disengaged. | Building Trust between Parties | Building trust and empathy. | This section details a three-step process for building supportive, positive relationships and increasing trust between agency leadership, union leadership, and frontline transit workers. |

| Fostering Community among Frontline Transit Workers | Increasing employee engagement. Building trust and empathy. |

This section includes creative ways to build a sense of community among frontline transit workers who may not naturally have an opportunity to regularly engage with their peers. | |

| Developing and Implementing Mentor and Peer Programs | Preparing employees for their work environment. Increasing employee engagement. Building trust and empathy. |

This section includes a framework for the development of a mentorship program based on research from other agencies and industries. | |

| My agency’s frontline workers feel unprepared or unsupported in their jobs. | Increasing Training Offerings | Increasing mental health and wellness offerings. Preparing employees for their work environment. Building trust and empathy. |

This section identifies three types of trainings that frontline workers or their managers and supervisors identified as useful for coping better with certain on-the-job situations. |

| Developing and Implementing Mentor and Peer Programs | Preparing employees for their work environment. Increasing employee engagement. Building trust and empathy. |

This section includes a framework for the development of a mentorship program based on research from other agencies and industries. |

| Key Issue Statement | Toolkit Component* | Issues Addressed | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Providing Support during and after Incidents | Supporting frontline workers during and following traumatic events. | This section includes best practices for supporting frontline workers in the field: specialized critical incident response teams that can respond to incidents in the field (e.g., vehicle crash or person under train incident) and improvements to post-incident support. | |

| Building Trust between Parties | Building trust and empathy. Promoting empathetic leadership. |

This section details a three-step process for building supportive, positive relationships and increasing trust between agency leadership, union leadership, and frontline transit workers. | |

| Some of my agency’s current policies and procedures are not supportive of employee work–life balance or mental health and wellness. | Providing Support during and after Incidents | Supporting frontline workers during and following traumatic events. | This section includes best practices for supporting frontline workers in the field: specialized critical incident response teams that can respond to incidents in the field (e.g., vehicle crash or person under train incident) and improvements to post-incident support. |

| Modernizing Operational Policies for a Healthy Workforce | Improving operational policies to provide flexibility and a better work–life balance to frontline workers. | This section includes ideas for modernizing operational policies and procedures to improve the work–life balance for frontline workers and provide more time to rest and recover from intense, stressful work. | |

| As a frontline worker, I want to learn how to advocate for myself and my peers to improve our overall well-being at work. | Self-Advocacy Tools | Empowering self-advocacy for frontline workers in the workplace. | This section includes resources for frontline workers to be their own advocates for mental health and wellness in the workplace. It includes information on worker rights, how to effectively communicate with management, how to leverage partnerships with human resources departments, and how to become a peer advocate or start a resource group. |

* Click on the titles of linked toolkit components to jump to those sections.

Program Evaluation

This project’s research findings indicate transit agencies are not consistently evaluating the effectiveness of their mental health and wellness programs, making it hard for them to know whether their strategies are working and how to adapt them as conditions change. Continuous improvement is vital for programs to effectively address constantly evolving issues. The guidance on capability maturity measurement in this section adds a tool to agencies’ and unions’ resource arsenals that can help them develop and continuously improve mental health and wellness programs.

This section summarizes core Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI) concepts. The conceptual framework of capability maturity was originally developed by researchers at Carnegie Mellon University. Formally known as CMMI, these concepts have been used for organizational performance improvement across many fields, including aerospace engineering and government. (For more information, see Godfrey, 2004). These concepts are especially useful for agencies, unions, and staff who are newer to evaluation, since the evaluation can be done qualitatively (What is working, and what needs improvement?) as well as quantitatively (How often does this need to happen to be successful?).

Table 6.2 defines five stages of capability maturity and provides examples of how these stages apply to management of mental health and wellness programs, namely employee assistance programs (EAPs) and union assistance programs (UAPs), at transit agencies. Capability maturity is used for evaluation throughout the transportation industry, most prominently by state departments of transportation for transportation systems management and operations (TSM&O).

Table 6.2. Capability maturity matrix.

| Stage | Characteristics | EAP/UAP Examples |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Initial | The work process is poorly controlled and reactive, relying on individual efforts on an individual basis—this stage has the highest risk of failure and greatest variability in quality. | Transit agency or union has secured a vendor for EAP/UAP services and offers other programs and resources through their healthcare provider. The burden is primarily on individual frontline workers to access services when they need them. |

| (2) Repeatable | The work process is documented well enough that it can be repeated the same way on a project basis, even for employees who are new to the process. Furthermore, work can be planned well in advance and monitored at a rudimentary level. | Transit agency or union has implemented a regular marketing plan to build awareness of EAP/UAP resources. However, resources are still dispersed among different websites, call centers, etc. Frontline workers must navigate various portals to find the resources they need. |

| (3) Defined | The work process is well-defined, and adoption is standardized. Processes of individual projects are tailored to the standard. Projects can verify and validate work integrity, and organizations can integrate the work of related projects. | In addition to having a marketing campaign that builds awareness of resources in various ways (flyers, lunch-and-learns, emails, etc.), the transit agency or union has also developed a single online resource hub that clearly explains where and how to access services. |

| (4) Managed | The organization quantitatively tracks process activities using standard metrics, such as hours worked, activity clearance, or percent complete, which makes complex organizational integration and performance management possible. | Building on the comprehensive marketing campaign and one-stop resource hub, the transit agency or union is also tracking which resources are most accessed as well as collecting metrics to see how worker well-being (e.g., absences, retention) has been impacted since the start of various activities and immediately following marketing blitzes. |

| (5) Optimizing | The organization engages in process analysis, which provides management and staff with sufficient visibility into relationships between processes and outcomes to collaborate for continuous improvement. | After reviewing utilization and outcome metrics, the transit agency or union begins measuring the effectiveness of individual EAP/UAP offerings to determine which should be discontinued, added, or expanded. The organization also uses employee focus groups and committees to help evaluate and improve EAP/UAP offerings and marketing of services. |

FHWA developed a suite of capability maturity matrix (CMM) tools focused on TSM&O work functions, such as ensuring travel time reliability, safety training, and timely asset management (National Operations Center of Excellence, n.d.). Transit agencies may consider perusing that guidance for examples and inspiration when employing CMM concepts.

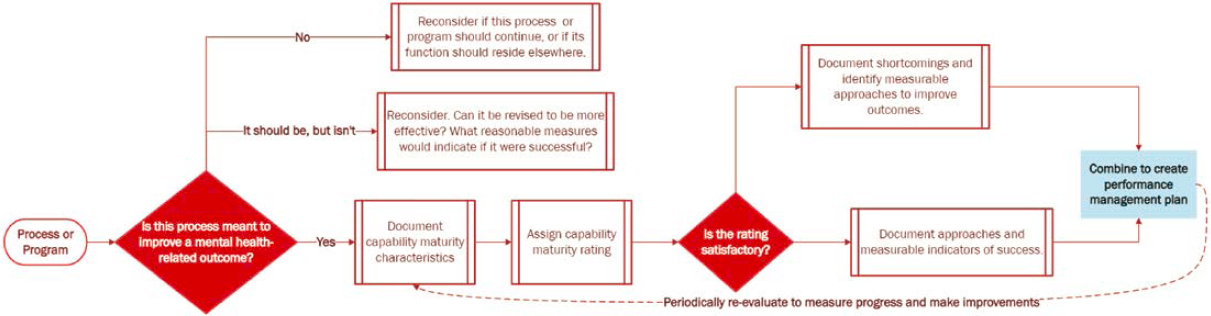

If desired, apply the CMM concept to worksheets throughout this toolkit by conducting a simple evaluation (Figure 6.1). Evaluation should rarely result in punitive action: Its purpose is to clarify what is and is not happening, clarify what is and is not in the program’s span of control, and make continuous improvements. Staff should work together to consider a program or its component processes’ functions and assign a capability maturity rating, preferably based on a categorical (yes or no) or quantitative indicator that measures the success of the desired outcome. If the function of a program or process is not related to improving mental health among transit workers, staff may consider whether it should be revised or managed elsewhere in the organization. Likewise, if a program or process could be used to improve mental health among transit workers but is not currently designed for such a purpose, staff may consider how to restructure and make it more effective.

Agencies and unions conducting the CMM evaluation need to use meaningful measures of success, periodically re-evaluate, and document progress. Staff may discover that creating a report on workforce mental health enhances organizational processes, clarifies their objectives, refines outcome measurement methods, and tracks progress toward these outcomes. This formalization can help structure continuous improvement by making it easier to trace how a program has evolved over time and prevent the repetition of unsuccessful strategies.

Additional Resources

For more information about the capability maturity matrix, see Godfrey (2004). See also FHWA’s developed suite of CMM tools focused on TSM&O work functions (National Operations Center of Excellence, n.d.).

Evaluating and Improving EAPs and Union Assistance Programs

While transit agencies and unions may offer assistance programs to their staff and members, research conducted for this project indicates the process for evaluating this programming is often unclear or nonexistent. Although employee assistance programs (EAPs) as offered by transit agencies may be more well-known, unions have also developed their own programming for

members. This section includes four tables, each one a detailed worksheet with questions to help transit agencies and unions document their processes related to assistance programs, as well as assess and identify opportunities to enhance them.

Union Assistance Programs

Transport Workers Union (TWU) Local 100 has provided a robust union assistance program (UAP) since 1988. The program provides members with assistance for substance misuse, psychological issues, family problems, and other personal issues on a voluntary and confidential basis.

The TWU Local 100 UAP was featured in a 2023 study commissioned by the International Transport Workers’ Federation. The report explored union-based initiatives to protect the mental health of young public transportation workers.

Each worksheet covers one of four main components:

- Marketing. Transit agency staff and union members may not be aware of the resources available to them. Table 6.3 helps agencies and unions identify the methods they are currently using.

- Accessing Services. Reducing barriers to access is a critical component of helping workers get the support they need. Since worker needs and preferences vary by individual, Table 6.4 helps transit agencies and unions document the different ways in which staff and members can access services.

- Vendor and Program Evaluation. The existence of a program provides a starting point to assist staff and members in addressing mental health and wellness needs, but agencies and unions need to conduct continuous quality control. Table 6.5 includes guiding questions to facilitate program evaluation.

- Building Trust. The research conducted throughout this project indicates employees may be hesitant to seek assistance due to privacy concerns and the fear of repercussions (e.g., termination due to seeking treatment for substance misuse). Maintaining confidentiality is critical for the use and success of assistance programs (Table 6.6). While programs are generally confidential, there are some instances in which providers must inform authorities (e.g., if an employee or member wants to harm themselves or others).

Additional Resources

For more information on evaluating EAPs, see Evaluating Employee Assistance Programs in University of Maryland, Baltimore’s digital archive (Masi, 1997).

For information on working with EAP vendors to provide additional mental health resources, see the National Safety Council’s Working with Benefits Providers: Mental Health Issues Checklist.

Establishing Wellness Programs

The Society of Human Resource Management (SHRM) found that wellness programs can help increase employee morale and improve overall health while decreasing an employer’s healthcare costs. Wellness programs can also increase the productivity of employees by reducing sick days. According to a survey of over 700 frontline workers conducted for this report, workers value having a variety of resources available to them in different formats. This means that a successful

Table 6.3. Worksheet: Marketing in EAPs and UAPs.

| Guiding Questions | Agency/Union Answer | Notes on Process/Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Process Components | ||

| Advertising. How do employees, contracted staff, or union members learn about the assistance program? Check all the places where your agency/union advertises the program. |

Check all that apply:

□ Intranet □ Email to employees with agency addresses/email to members □ Text messages □ Flyers, posters, and postcards in common areas □ Sharing information during recurring meetings □ Sharing information during onboarding □ Sharing information during open enrollment periods □ Other (open-ended response) |

|

| Referrals. Is there any person or organization that can refer employees or members who may need assistance program services? List any people involved in the process. | ||

| Barriers to implementation. What steps, if any, has your agency or union taken to ensure all employees are being reached? | ||

| Metrics | ||

| For each marketing avenue identified, how often is the avenue used to make a referral? (For example, when a link to the EAP/UAP website is emailed, how many clicks does the link receive?) | ||

| How does awareness of EAP/UAP services compare to the utilization rate of services? | ||

Table 6.4. Worksheet: Accessing services in EAPs and UAPs.

| Guiding Questions | Agency/Union Answer | Notes on Process/Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Process Components | ||

| Eligibility. Who can access assistance program resources? |

Check all that apply:

□ Staff (direct hires) □ Staff (contracted) □ Staff (direct hires) and spouses □ Staff (contracted) and spouses □ Staff (direct hires) and extended family □ Staff (contracted) and extended family □ Union members □ Union members and spouses □ Union members and extended family |

|

| Access. How can employees or members access assistance program services? |

Check all that apply:

□ Virtual □ In-person, group setting □ In-person, individual □ On-site, group setting □ On-site, individual |

|

| Application. What is the process for staff or members to use assistance program services? Describe the steps that staff or members must take to request and use services, including the information they need to provide to access services and estimated wait times to receive services. | ||

| Barriers to access. What steps, if any, has your agency or union taken to address issues regarding access to services (including scheduling difficulties or technology challenges)? | ||

| Metrics | ||

| How many staff or members utilized assistance program services in the last calendar year? (Note: If you are unable to track the utilization of services, work with your vendor to identify ways of collecting the information.) | ||

| What was the most popular method of accessing program services? What was the least popular? | ||

Table 6.5. Worksheet: Vendor and program evaluation in EAPs and UAPs.

| Vendor and Program Evaluation | Agency/Union Answer | Notes on Process/Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Process Components | ||

| Vendor selection. Describe the process for selecting an assistance program vendor (where applicable). What factors were considered when evaluating vendors (e.g., cost, coverage, specific services provided)? | ||

| Service level agreements. Describe the process for monitoring the vendor, in particular the vendor’s adherence to agreed-upon service levels (e.g., response times, number of available counselors). Describe the process, if one exists, for taking corrective action if the vendor does not meet requirements. | ||

| Facility assessment. Does your agency or union conduct an on-site visit to the vendor’s facilities? If so, what aspects of the facilities are assessed? |

Check all that apply:

□ Condition of physical office □ Accessibility of physical office □ Office location and ease of access |

|

| Cost-benefit analysis. How does your agency or union calculate the cost and associated savings of programming, and what metrics are used to assess whether the program is operating effectively? (Note: There are costs associated with absenteeism, inability to recruit or retain talent, medical expenses, etc. How does your agency or union factor these costs into the analysis? Could the increased costs of offering more services be offset by savings achieved through more retention and less absenteeism?) | ||

| Reporting frequency. How often does your agency or union receive vendor reports? What do these reports measure? How are these reports used to assess performance and identify areas of improvement (including year-over-year)? | ||

| Surveying staff or members. Has your transit agency or union surveyed staff or members about the strengths and weaknesses of the program, as well as opportunities for enhancing it? If yes, describe the survey content, when the survey was administered, and the results as well as how they were addressed. | ||

| Vendor and Program Evaluation | Agency/Union Answer | Notes on Process/Metrics |

|---|---|---|

(Note: You might include questions related to the assistance program as part of other surveys, such as surveys for existing employee engagements.) Potential survey questions include:

|

||

| Surveying program users. Is there a process in place for surveying people who used the assistance program? If so, describe the process and how survey results are used to evaluate and enhance services. | ||

| Metrics | ||

| What is the current utilization rate for the assistance program? What is last year’s rate? (Note: If you are unable to track the utilization of services, work with your vendor to identify ways to collect that information.) | ||

| How many staff or members indicate they are satisfied with the program or services provided? | ||

Note: Masi (1997) was used to create this worksheet.

Table 6.6. Worksheet: Building trust in EAPs and UAPs.

| Guiding Questions | Agency/Union Answer | Notes on Process/Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Process Components | ||

| Confidentiality. Do you know what information about program use you are legally able to request? Is there a policy in place to prevent any “off-the-record” conversations about staff or member cases? | ||

| Barriers to entry. What steps, if any, has your agency or union taken to address the stigma of seeking help (e.g., fear of a loss of confidentiality, fear of professional repercussions for seeking help)? | ||

wellness program designed for frontline workers should contain distinct components and offer services across various formats. Table 6.7 lists several components that agencies and unions can consider when designing a wellness program.

Steps to Establish and Design a Wellness Program

The SHRM has identified nine steps to establish and design a wellness program. These steps are outlined in further detail in this section.

- Conduct assessments and determine needs.

- Build support and gain buy-in from leadership.

- Establish a wellness committee.

- Develop goals and objectives.

- Establish a budget.

- Design wellness program components.

- Develop wellness program incentives or rewards.

- Communicate the wellness plan.

- Evaluate the success of the program.

Conduct Assessments and Determine Needs

The best way to begin developing a successful wellness program is to survey employees directly and collect baseline health data. This will allow the program manager to measure success and make continuous improvements over time. Transit agencies and unions should start designing their wellness program by evaluating what employees need most. Consider conducting focus groups, employee surveys, or health risk assessments to identify and understand these needs. Likewise, it may be a good idea to review health plans and existing EAP and UAP offerings to understand what, if anything, is already covered or included in other services that the transit agency is paying for. Staff should consider periodically revisiting these assessments to see whether the program is achieving its goals.

Key questions include:

- What are the biggest challenges your frontline workers face with regard to mental health and wellness?

- What resources or tools would help your frontline workers cope with these challenges?

- What wellness resources does your agency already offer?

Table 6.7. Components of a wellness program.

| Program Component | Description | Resources Required & Other Considerations | Magnitude of Cost (Low, Medium, High) |

|---|---|---|---|

| On-site health services | On-site health services reduce barriers to access by bringing health professionals to the job site for things like routine physicals, health screenings, counseling, and disease management. | Partnership with a healthcare provider as well as agency staff to help oversee the program’s execution are required. Additionally, space or facilities on-site would need to be identified to house the on-site clinic services. (See also Case Study 4: On-Site Health Clinic Services in Chapter 5.) | High |

| Health screenings | Health screenings can help detect diseases and other chronic health issues. Early detection can help employees achieve better health outcomes in the long term. Health screenings can be done in person or, to some extent, virtually. | Transit agencies can check with their healthcare providers and employee assistance program (EAP) or union assistance program (UAP) vendors to see if health screenings are included. If so, transit agencies will need to dedicate staff resources to promote the availability of free screenings. If not, agencies may need to procure a vendor to offer the screenings. In-person or on-site screening events may increase the utilization of this service, but this may also incur additional costs. |

Medium |

| On-site gyms and fitness equipment | An on-site gym can encourage employees to stay active by providing access to an exercise facility and equipment. On-site gyms can also be coupled with fitness classes or other fitness programs (see next component). | Transit agencies will need to purchase fitness equipment and identify a space onsite to house the equipment. Transit agencies also need to consider the costs of maintaining, cleaning, and potentially staffing a fitness facility. | Medium to high |

| Fitness programs and activities | Fitness and exercise programs are designed to encourage employees to stay active and lose weight. These programs can include recurring group exercise classes, one-off events like “fun runs,” and fitness challenges where employees earn rewards or compete with one another to meet various fitness goals. | Fitness programs range in cost depending on the type of event or ongoing activity and whether outside resources, like a fitness coach, are required. At a minimum, agencies would need to dedicate staff time to organizing and executing activities. | Low to medium |

| Program Component | Description | Resources Required & Other Considerations | Magnitude of Cost (Low, Medium, High) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stress-reduction programs | Stress-reduction programs aim to teach employees skills and techniques for reducing or managing stress at work and at home. Stress-reduction programs can include mindfulness or meditation sessions, yoga classes, and other techniques for stress reduction. They can be in person or virtual (either synchronous or on demand). | Depending on the offerings, stress-reduction programs can be led by agency employees or specialized instructors. For frontline workers, consider the format, time, and location of activities offered so that employees who work primarily in the field can still take advantage of stress-reduction programs. As with many other program components described in this table, transit agencies can check with their healthcare providers and EAP/UAP vendors to see if stress-reduction programs or mobile applications are included in their services. |

Low to medium |

| Lifestyle improvement programs | These can include weight loss, smoking cessation, and disease management programs (e.g., how to manage diabetes). Lifestyle programs target employees who may need help changing behaviors or managing certain chronic conditions. These programs can take a wide variety of formats—including one-on-one coaching, group sessions, virtual or in-person counseling—and may include educational components (e.g., newsletters, daily emails with tips, or webinar series). |

More hands-on components, such as coaching, require expertise to execute. Transit agencies can check with their healthcare providers and EAP/UAP vendors to see if they already offer these services. Promotion of lifestyle improvement programs and offerings requires a time commitment from transit agency staff. (See also the toolkit component Improving Communications and Marketing of Resources.) |

Low to high |

| Vaccination clinics or events | On-site events to provide vaccinations or other health screenings can be very effective in preventing illness and identifying chronic health issues. This type of event can remove barriers to employees | Consider working with your health insurance provider or a local pharmacy to set up an on-site clinic. Since many vaccinations and screenings are covered by health insurance, pharmacies and healthcare providers may be willing to host an on-site clinic at no cost to the transit agency. However, agency staff time will be required to organize and market the event. | Low to medium |

| Program Component | Description | Resources Required & Other Considerations | Magnitude of Cost (Low, Medium, High) |

|---|---|---|---|

| who would like to seek preventive care services but cannot do so because of their work schedule. | |||

| Lunch-and-learn or webinar educational series | Educational series can be deployed in person (e.g., lunch-and-learns) or virtually (e.g., webinars). These are usually short-format instructional events, usually dedicated to a single health-related topic. The benefit of a series is that employees get exposure to a wide variety of topics presented in a low-stakes, casual environment. This can make employees feel more comfortable learning about different topics. | Educational series take staff time to design, organize, and execute. Additionally, subject matter experts may need to be identified (internally or externally) and invited to speak on selected topics. In some cases, external experts may require consulting fees. | Medium |

| Reward or incentive programs | Reward or incentive programs are add-ons to a wellness program that encourage employees to increase their use of the resources an employer is already providing. A reward or incentive program can include nonmonetary rewards (e.g., a certificate and formal recognition in front of colleagues for completing a program), cash rewards, additional time off, or other prizes. |

Depending on the prizes or rewards available, the cost of this program component can be low or moderate. Consider what might motivate your employees. For example, tickets to a coveted sporting event may be more motivational than a cash prize. (See also Case Study 3: Incentives for Wellness Program Participation.) Additionally, transit agencies will need to dedicate staff time to organize, deploy, and track the rewards or incentive program. |

Low to medium |

Build Support and Gain Buy-In from Leadership

Buy-in from management and union leaders is essential for building support throughout the organization, approving related policies or processes, and securing funding. One of the best ways to gain management support is to clarify a wellness program’s impact on the bottom line. For more tips on how to gain buy-in and make the business case for a wellness program, see the toolkit sections Building Trust between Parties and How to Make the Case for Increased Benefits to Support Mental Health and Wellness.

Key questions include:

- What are the benefits of the wellness initiative to the employees and the organization?

- What are the strategic priorities of the organization, and how can a wellness program contribute to those priorities?

Establish a Wellness Committee

An internal, employee-driven committee contributes to a wellness culture and builds organizational support. A committee that represents employees across various departments builds in diversity of thought and perspective for the wellness program offerings. A committee can also help generate organizational support for the effort. Additionally, committee members can help get their peers onboard with wellness programs and activities, reducing the stigma associated with seeking mental health support.

Key questions include:

- What programs and services are currently available to employees, and how do they meet current needs?

- How can members of this committee best support and represent their peers?

Develop Goals and Objectives

With the information gleaned from assessments and surveys conducted in previous steps, the committee can develop goals and objectives for the wellness program. Goals are the intended long-term outcomes, while objectives support goals with time-limited wording that clearly defines achievement.

Key questions include:

- What are the main goals of the program (e.g., reduced healthcare costs, improved productivity, increased retention)?

- What are the success metrics of the program?

Establish a Budget

To ensure program longevity through steady funding, the wellness program budget needs to be informed by identified goals and objectives. A thorough budget estimate should include the cost of incentives, marketing, provider fees, meeting provisions, committee member time, etc.

Key questions include:

- Would employees be willing to contribute to the budget (e.g., paying for a yoga class)?

- What wellness benefits does the current health insurance provider offer? What wellness programs does the EAP or UAP vendor offer?

- Are there low-cost activities or free community resources that could help meet employee needs?

Design Wellness Program Components

The assessment data and budget can be used to design the wellness program itself. Managers must ensure that there are no legal or compliance conflicts regarding ADA and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. (See also Table 6.7 for wellness program components.)

Key questions include:

- What are the main risk behaviors to address? How would addressing these behaviors align with meeting the needs of employees?

- Does the proposed wellness program avoid discrimination?

Develop Wellness Program Incentives or Rewards

Wellness programs can encourage participation by offering incentives with the hope of converting external rewards to intrinsic drive. Examples of incentives include the ability to accumulate points for participation in certain activities and exchange them for goods or gifts; other gifts or monetary rewards for participating in certain wellness program activities; and additional benefits, such as extra paid time off at work for completing certain activities. Competitions or challenges with prizes, such as a daily steps challenge, can also be effective at incentivizing participation in wellness activities.

Key questions include:

- What kind of reward system would best address the risk behaviors?

- How do the incentives help build long-term change?

Communicate the Wellness Plan

Once finalized, the wellness program needs to be communicated to the employees. A written wellness policy with a statement of intent and a description of involvement and the reward system can build participation. Marketing materials need to communicate that the organization’s social culture values health. (See also the Improving Communications and Marketing of Resources component of this toolkit.)

Key questions include:

- Which examples, based on anecdotal scenarios, would provide the most clarity on the initiatives?

- How can upper management support and endorse the program?

Evaluate the Success of the Program

Measuring the success of the program is essential in sustaining program support and participation. Baseline data from initial assessments can be used to monitor improvements. Examples of success indicators include participation rates, reduction in healthcare costs, and percentage of employees that stopped engaging in risk behavior. (See also the Program Evaluation and Evaluating and Improving EAPs and Union Assistance Programs components of this toolkit.)

Key questions include:

- How has this program affected the well-being of employees and the overall culture of the organization?

- How can you track the success of the wellness program against the identified goals and objectives?

Other Tips and Considerations for Building a Comprehensive Program

The following list includes some final considerations for developing a wellness program for frontline transit workers:

- Provide various offerings to cover the numerous challenges that frontline transit workers face, including wellness components that focus on both physical and mental health.

- Consider a variety of access methods: virtual, in person, group, and individual. Based on the survey of frontline transit workers (Chapter 3), there is a wide range of preferences for how to access wellness services.

- Build buy-in from top to bottom. Trust is a key reason why frontline workers feel isolated from transit agency managers and leaders. Involve frontline workers directly in program development to demonstrate that their employer values their input in agency decisions.

- Consider privacy—communicate to frontline workers that programs, activities, and other resources offered through the wellness program are confidential.

Additional Resources

For more information, see the how-to guide How to Establish and Design a Wellness Program and the article “The Real ROI for Employee Wellness Programs” from SHRM.

Support Mental Health in the Workplace: Checklist for Leadership and Senior Managers

According to the survey of over 700 frontline workers conducted for this report, frontline workers experience elevated anxiety and depression at work and reported high levels of workplace stress. Over one-third (35.8%) of survey respondents met the criteria for probable anxiety and 37% for probable depression. (For more detailed information on frontline worker survey findings, see Chapter 3.) Managers and leadership can do more to support the mental health and wellness of their employees. The following section is a modified version of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s (OSHA’s) Supporting Mental Health in the Workplace: Checklist for Senior Managers (OSHA, n.d.-a).

These checklists (Tables 6.8, 6.9, 6.10, and 6.11) are helpful tools that provide suggestions for agency leadership, union leaders, and those who manage frontline workers directly on how to frame worker needs, better support employees’ mental health, and alleviate stressors.

Table 6.8. Be a compassionate leader and establish a supportive tone.

| Checklist Item | Additional Suggested Actions |

|---|---|

|

□ Tell staff you are committed to supporting their mental health and well-being. |

|

|

□ Raise awareness about workplace stressors and reduce the stigma surrounding mental health issues and substance use. |

|

|

□ Be transparent. Ensure communication takes place regularly to alleviate the stress of uncertainty and to defuse misinformation or rumors that might be circulating. |

| Checklist Item | Additional Suggested Actions |

|---|---|

|

□ Consider creating a mental health task force or committee, with representatives from different levels of your organization (i.e., not only senior managers), to talk about existing and emerging workplace stressors and ways to reduce them. |

|

|

□ Build a culture of connection and encourage coworkers to be supportive of one another. |

|

Table 6.9. Assess whether you can modify operations, assignments, schedules, policies, or expectations to alleviate or remove stressors.

| Checklist Item | Additional Suggested Actions |

|---|---|

|

□ Examine workers’ tasks to determine whether their workload has increased, and if so: |

|

|

□ Revisit organizational policies and, when possible, allow for more flexibility with leave policies, work schedules, and telework. |

|

|

□ Provide training, tools, and equipment to help workers adapt to their job tasks and work environment. For example: |

|

|

□ Provide various methods for workers and supervisors to share their ideas on how to reduce or remove workplace stressors, without fear of scrutiny. Examples include: |

|

Table 6.10. Prepare supervisors to be empathetic and supportive.

| Checklist Item | Additional Suggested Actions | Potential Impact |

|---|---|---|

|

□ Train frontline supervisors on stress and mental health topics so that they have the skills and confidence to initiate discussions with workers and to recognize the signs and symptoms of stress and mental health emergencies. For example, consider requiring supervisors to take: |

|

Employees will be able to trust management with hard conversations and work together with management to discuss solutions. |

|

□ Ensure that supervisors understand their role: to listen and validate workers’ feelings, concerns, and experiences. Ensure that supervisors understand that being dismissive of workers can be damaging. |

Employees will feel supported by management. One reason why many frontline workers leave their jobs is due to issues with management. Genuinely empathetic management could improve retention rates. | |

|

□ Advise supervisors that they may need to alter their leadership style, including: |

|

Employees may learn from management’s examples and develop better self-care behaviors, which can improve performance and retention. |

|

□ Instruct frontline supervisors to watch for declines in worker performance, an indicator of problematic stress. |

By identifying stress early on, leadership can intervene and come up with solutions to ensure workers are taken care of and performance is improved. |

Table 6.11. Provide or share information about coping, resiliency, and mental health resources.

| Checklist Item | Additional Suggested Actions |

|---|---|

|

□ Provide self-care tools and stress management, mental health, and well-being resources: |

|

|

□ Share resources and outreach materials developed by entities outside your organization (e.g., federal and state governments, local support organizations) that raise awareness about the signs and symptoms of distress. Examples include: |

|

|

□ Participate in existing promotional campaigns on mental health throughout the year. For resources, promotional materials, and ideas, visit: |

|

|

□ Consider implementing a well-being challenge with self-care activities for workers. |

|

|

□ Promote free or low-cost online tools and apps for stress reduction, mindfulness, and personal resilience (e.g., the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs’ Mindfulness Coach, SAMHSA and the American Psychiatric Association’s My Mental Health Crisis Plan). |

Additional Resources

See the original checklist developed by OSHA (n.d.).

How to Make the Case for Increased Benefits to Support Mental Health and Wellness

Employee wellness is critical to maintaining a productive, resilient workforce in today’s rapidly changing employment landscape. Companies that prioritize the mental health and wellness of their employees not only exhibit a commitment to their staff’s overall well-being but also stand to yield substantial benefits in overall employee productivity and long-term business success. Specific benefits include lower healthcare costs, better recruitment and retention, reduced absenteeism, and improved employee engagement. Moreover, workplace health and wellness programs can help employees modify their lifestyles and move toward an improved state of wellness, even outside the

workplace. Worksite health and wellness interventions include health education, nutrition services, lactation support, physical activity promotion, screenings, vaccinations, traditional occupational health and safety, disease management, linkages to related employee services, and others.

This section of the toolkit includes example messages and some statistics to help agencies and unions make the case for increasing the benefits offered by mental health and wellness programs for frontline workers. The section concludes with a worksheet (Table 6.12) to help frame a “business case” for a particular program, policy, or pilot.

Example Messages and Related Statistics

- Transit agencies will save money. Mental health support can help reduce overall healthcare and disability costs. Statistics from the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) suggest that people with depression have a 40% greater risk of developing cardiovascular and metabolic diseases (NAMI, n.d.). Moreover, people with a serious mental illness are nearly twice as likely to develop such conditions. Thus, supporting employees’ mental health is critical to avoid these conditions and the associated costs of treatment.

- Increased wellness and mental health offerings lead to increased retention. A survey conducted by Mind Share Partners (2021) found that approximately 50% of full-time workers in the United States have had at least one mental health reason for leaving a job. These points suggest a greater need for employers to provide mental health support for their employees.

- Mental health programs increase productivity. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), anxiety and depression cost the global economy around $1 trillion per year in lost productivity (WHO, n.d.). WHO also estimates that every $1 spent on treating common mental health concerns is associated with a return of $4 in improved productivity and health. A study by Goetzel et al. (2018) demonstrated that about 86% of employees receiving depression treatment were found to have improved work performance.

-

Employees will save money and be healthier. Participation in worksite health and wellness programs can help employees reduce their healthcare spending in the following ways:

- Through health education, employees can learn which preventive care services are covered by insurance, including screenings, immunizations, and well-woman exams. They can also have regular doctor visits for health assessment, lowering the long-term and more expensive costs that would be required to treat an illness.

- On average, smokers pay 15% to 20% more for monthly insurance premiums than nonsmokers (Tobacco-Free Life, n.d.). By participating in tobacco cessation programs, employees can manage or quit smoking, resulting in savings by reducing or eliminating tobacco costs in the short term and costs associated with chronic health issues caused by smoking in the long term.

- Creating a supportive and flexible working environment leads to enhanced performance and greater employee satisfaction. One study of employees found that working from home enhanced employee performance by 13%, increased job satisfaction, and led to a 50% drop in turnover rate (Jiang et al., 2023). This suggests that flexible work options, like remote work or flexible hours, can help employees better manage their mental health. In another study, nearly 50% of employees agreed that a strong relationship exists between the physical working environment and their motivation to perform (Bushiri, 2014). Therefore, creating a positive and supportive work environment can help employees feel more comfortable discussing and addressing their mental health needs.

Building Your Own Message

Building a case for a particular program or idea to improve the mental health or wellness of frontline employees may require convincing agency or union leaders that your idea is beneficial to the overall agency or to their personal workplace goals. To do this, think about how you will convey the idea and create a compelling case to leadership. Table 6.12 is a worksheet that agency or union staff can use to build a case for support.

Table 6.12. Worksheet: How to make the case for increased benefits.

| Prompt | Considerations | Agency Answer |

|---|---|---|

| How will you measure success? What tools, metrics, or data sources will you use to measure the program’s or policy change’s success? | Be prepared to explain how success will be measured and how you will know that the program delivered the desired results. | |

| Program or idea. Describe the program, policy change, or other idea you are proposing. | ||

| Purpose and goals. How will this program or policy change impact employee mental health and wellness? What specific goals will this program or policy change meet? | Think about the specific skills, tools, or resources that will be provided through this program or policy. | |

| Do your research. Is there independent research or literature that supports your ideas? Alternatively, is there a successful example from another transit agency that you can point to? What were the results of that program? | Others may be convinced by independently verified research. It will strengthen your case to have an example where such a program was successful. It may help to look beyond the transit industry for examples. | |

| Audience. Who are the key stakeholders that must be convinced to pursue this new program or policy? | Do you need to convince leadership? Your manager? The union? Your colleagues or peers? There may be more than one audience or group of stakeholders to convince that your new program or policy is worth investing in. List all the members of your audience. | |

| Audience values. What aspect of this program or its purpose will speak to each person or group identified in your audience? | Think about what is important to each audience member. What do they value? You may need to create a different pitch for each audience member. |

| Prompt | Considerations | Agency Answer |

|---|---|---|

| Operating and capital costs. What are the costs of implementing this program? | Think through a budget for the program or the cost implications of changing a policy (e.g., adding a paid mental health day). Will staff time be required to design, implement, or manage the program? How much time and at what rate? Will the time that employees take to participate in the program be paid or unpaid? Are there capital expenses to account for? |

|

| Return on investment (ROI). What gains or savings will this program create? | It is compelling to match capital and operating expenditures with a real, tangible return on that expense. For example, “We will retain more employees because [XYZ] research showed for every dollar invested, [#] employees stayed [#] years longer.” This will be the most challenging piece of the message to create. Sometimes ROI is not numbers but rather qualitative items, such as increased employee satisfaction. |

|

| Put it all together: Make the pitch. Write a compelling, brief message that explains the program idea and the impact it will have on employee mental health and well-being. Explain the ROI. | Think of this as the elevator pitch for your idea. Stick to only a few sentences. As you write your pitch, consider what is compelling to your audience members so you can align your goals with their goals. | |

Next steps:

|

||

Additional Resources

- Corporate Wellness Magazine article, “The Benefits of Employee Mental Health Programs.”

- Jiang et al. (2023) article, “More Flexible and More Innovative: The Impact of Flexible Work Arrangements on the Innovation Behavior of Knowledge Employees.”

- HR Exchange Network article, “Employee Experience: The Business Case.”

- Kaiser Family Foundation article, “2022 Employer Health Benefits Survey.”

- Goetzel et al. (2018) article, “Mental Health in the Workplace: A Call to Action Proceedings from the Mental Health in the Workplace: Public Health Summit.”

- Mind Share Partners (2021) report, 2021 Mental Health at Work Report.

- NAMI (n.d.) webpage, Mental Health by the Numbers.

- Bushiri (2014) dissertation, “The Impact of Working Environment on Employees’ Performance: The Case of Institute of Finance Management in Dar es Salaam Region.”

- The Work Foundation report, The Business Case for Employee Health and Wellbeing.

- Tobacco-Free Life (n.d.) webpage, Cost of Smoking.

- Understood for All, Inc., article, “Workplace Mental Health: 5 Ways to Support Employee Wellness.”

- U.S. Office of Personnel Management fact sheet, “Business Case for Employees: Worksite Health & Wellness Campaign Fact Sheet.”

- WHO (n.d.) webpage, Mental Health and Substance Use.

Improving Communications and Marketing of Resources

By effectively marketing your agency’s mental health resources for frontline workers, you can expand their utilization, increasing their benefit to your agency’s workforce. The distributed nature of transit industry jobs (i.e., frontline workers primarily work off-site and have work shifts at all times of day) necessitates deliberate planning to effectively communicate with frontline employees. To address findings that frontline workers often feel uninformed about this programming, this section includes guidelines for communicating and marketing mental health resources.

Understanding Your Audience

Effective communication requires an intimate knowledge of your audience. While the audience may seem obvious for communications with frontline employees, taking a few minutes to consider the job classifications that compose this group might yield some surprises. When interviewed about how best to communicate with frontline workers, transit workers generated substantially different answers to this question, even among individuals working at the same agency. Discussions with colleagues on how best to reach frontline workers ensure that marketing efforts reach all individuals who might benefit from mental health resources.

Equally critical to identifying your audience is recognizing their unique needs. An ideal means of communication for one transit worker might be totally inaccessible for another. The easiest way to understand what works for your employees or union members is to ask them. The Utah Transit Authority recruited a team of employees to develop a plan for connecting with employees to promote the accessibility of information. This approach ensures that diverse workforce needs are considered. If your agency does not have a task force dedicated to improving communications, then periodically check in with employees and ask what does and does not work for communicating mental health and wellness resources.

Making the Connection

Clearly communicating resources from onboarding through retirement is critical. Depending on your agency’s size, the agency may need to hire a dedicated staff person to coordinate

Tips to Make a Connection

- Be consistent and persistent: Market resources at regular intervals, from onboarding through retirement.

- Create a one-stop shop for employees to find information.

- Increase recognition by giving your mental health and wellness programs an identity under one wholistic brand.

- Share success stories of how resources have helped employees.

- Use a variety of media—in person, print, email, SMS, social media, etc.—to reach employees.

communications surrounding mental health and wellness resources (e.g., services available through an employee assistance program or union assistance program).

Maintaining a single source for this information ensures that while vendors might change, employees always know exactly where to turn for resources and information. Creating an intranet is a great way of compiling this information in a readily accessible location. When developing the site, ensure compatibility with mobile browsers, since many frontline workers will primarily access the intranet from a smartphone.

Another opportunity to increase utilization is by creating a compelling message to accompany resources. In creating an intranet, your agency has an opportunity to establish a brand for its resource hub. This brand gives efforts related to employee wellness an identity, encourages the use of these resources, and facilitates marketing efforts. Messaging on the benefits of resources may be the most powerful marketing tool at your agency’s disposal. Rather than relying on a vendor’s marketing materials, develop success stories attached to specific benefits, and share these alongside the resources on your intranet. Hearing or reading how resources helped employees is far more powerful than stock media, and it demonstrates how the resources can be used to address specific challenges unique to the agency and its employees. For example, transit agency employees have expressed concern about stress management, so success stories could demonstrate how an employee used stress management techniques gained from the resource hub.

Another critical element to improving communication is ensuring equal access to resources, regardless of work location or shift time. Consolidating resources is the first step in this process, but it is also critical to meaningfully engage with workers when and where they are available. Visiting break rooms and garages to speak with employees across shifts and distribute materials is a great way to ensure everyone hears the same message. Additionally, marketing across emails, SMS, social media posts, posters, and quick reference cards will help the message reach all employees, regardless of an employee’s preferred means of communication.

By leveraging technology, you can assess the effectiveness of your engagement and understand which marketing media work best. When directing employees to a resource hub, you can utilize a URL-shortening service (e.g., bitly) to create unique links and QR codes that can track how often a link is visited. Over time, you can identify trends across shifts and work locations to further refine your marketing efforts.

Communications and Marketing Worksheet

Table 6.13 presents a worksheet that transit agencies and unions can use to develop or refine a marketing approach for sharing information with frontline workers about available resources.

Table 6.13. Worksheet: Communicating and marketing mental health resources.

| Consideration | Item | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Audience. Who is your target audience? Consider who regularly interacts with your riders; these individuals are frontline workers, and they may benefit from mental health and wellness resources to help them manage the stress associated with this role. |

Identify frontline workers:

□ Operators □ Station attendants □ Fare inspectors □ Police officers and security personnel □ Outreach workers □ Field supervisors □ Maintenance personnel □ Cleaners □ Customer service representatives □ Dispatchers □ Other: |

|

| Means of communication. How will you reach your target audience? Consider the preferred methods of communication. Do communication methods differ for employees based on work location, shift time, and internet access? |

Digital:

□ Intranet □ SMS □ Social media |

Ensure that digital communications support mobile browsers. |

|

Use QR codes to link employees to resources. |

||

|

Identify opportunities for employees to share stories about leveraging agency resources to address their mental health challenges. |

||

| Marketing opportunities. When and where can employees learn about the resources available to them? Any gathering provides an opportunity to remind employees of mental health resources. |

When:

□ Onboarding □ Staff meetings □ Training courses |

|

| Ensure posted materials reach locations throughout your agency (i.e., not just headquarters). Materials that are regularly distributed to employees (e.g., run sheets) provide an opportunity to market resources. |

Additional Resources

See also the Mass Transit Magazine article “Improving Internal Communication” and the Transit Center article “Baltimore MTA’s ‘In-Reach’ Program Meets Bus Operators Where They Are.”

Building Trust between Parties

Trust can be defined as belief in the ability and integrity of another person or entity. It begins with authenticity from all parties involved and relies on the understanding that although there may be some interests at odds with each other, parties are engaging in conversations and collaborating in good faith. Trust between management, workers, and labor is integral for any transit agency to function well and provide high-quality service. Historically, trust has not been easy to maintain. Safety concerns, scheduling difficulties, operator pay, legislative changes, and budgetary constraints have frequently tested relations between parties, often diminishing recruitment and retention, employee satisfaction, and service.

Begin with Authenticity

Authenticity is crucial to the trust-building process. All parties must be ready to enter the trust-building process in good faith and with an awareness that collaboration will bring about culture change.

Likewise, COVID-19 had a profound effect on transit agencies and workers, making it even more difficult for agencies to recruit and retain frontline workers. This was particularly true early in the pandemic, when rapidly changing restrictions and conflicting messaging from local, state, and federal health officials made it difficult for frontline transit employees to know what was being done to keep them safe. Some employees interviewed for this study reported frustrations with the quality and consistency of contact tracing at their agency, making them wonder if administrative failures were leaving them unnecessarily vulnerable.

To address short staffing, workers at many agencies are being asked to pick up more hours to cover the shifts needed to deliver scheduled transit service. Transit agencies nationwide are facing shortages and low retention rates for frontline workers. One of the principal factors affecting retention rates is the mental and physical strain associated with operating a transit vehicle and handling passenger incidents. Now, more than ever, it is crucial for agencies and unions to work together to protect workers while ensuring that service is not diminished.

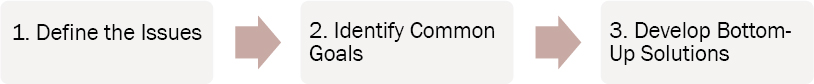

The following section of this toolkit describes a three-step process (Figure 6.2) to build and support positive relationships and increase trust between agency leadership, union leadership, and frontline transit workers.

Step 1: Define the Issues

Many of the issues faced by agencies, unions, and frontline workers are shared among all parties. From an agency perspective, low retention rates have directly affected the levels of transit service they can deliver. Workforce shortages have become common throughout the nation, and agencies are struggling to provide reliable transit services. Current workers have seen the effects of low retention rates and workforce shortages firsthand; demand for service has often led to workers taking on more or longer shifts to provide a minimum level of service. Transit operators have

also reported an increase in incidents involving aggressive or violent passengers. Recognizing the burden placed on their members, unions have sought to bargain for a healthier work–life balance for employees. Although many of these issues share the same solutions, distrust between agencies and unions remains, hindering the search for solutions that would solve common problems and improve the livelihoods of frontline transit workers.

Open and honest dialogue between agency leaders, frontline workers, and union representatives is required to help frame the shared challenges faced by workers. This can be achieved through a variety of ways, including town halls, coffee chats with leadership, dropping into existing meetings, digital engagement, labor-management committees, and collective bargaining.

- Town halls. Agency and union leadership can facilitate open conversations and collect feedback from workers directly by hosting a town hall–style meeting, where frontline workers can voice their thoughts among their peers and appeal directly to leadership. Agencies may consider holding such an event jointly with the labor union to demonstrate a united front in listening to frontline workers. Also consider the format and accessibility of the town hall format. More than one town hall event may be required to provide ample opportunities for workers to attend. A hybrid format (i.e., in person and virtual) may also allow more workers to attend.

- Coffee chats with leadership. In this format, agency leaders meet frontline workers where they are for individual conversations. One-on-one conversations are less formal and more conversational than town halls, which can help gather feedback from workers who may be less inclined to speak in front of large groups. This also helps to build individual relationships that are more personal between agency leaders and workers. Agencies need to be thoughtful about how to capture feedback from a broad sampling of workers by holding events on different days (including weekends) and at various times of day.

- Dropping into existing meetings. Another option is to leverage existing meetings or events to engage with frontline workers about their issues and challenges. This can include visiting frontline workers when they are already gathered for mandatory training or for a benefits information session.

- Digital engagement. Consider soliciting information through surveys or internal social media (e.g., message boards on the intranet). This can be a low-cost way to collect data quickly; however, digital engagement may be interpreted as impersonal and may not contribute to building (or rebuilding) relationships between workers and leadership.

- Labor-management committees. Labor-management committees, such as the Joint Workforce Investment (JWI) organized by Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority (VTA) and the Amalgamated Transit Union (ATU) Local 265, are an innovative method for fostering cooperation around common goals, including frontline worker mental health and wellness. These partnerships allow workers to speak about the issues they face without fear of retribution, and they allow unions and agency leaders to work together to identify solutions.

- Collective bargaining. Collective bargaining is another effective tool for workers to ensure that their issues are heard and addressed by agency leadership. Open dialogue in the collective bargaining process is crucial to identifying the issues workers are facing.

Regardless of the means utilized to collect this information, it is important for agency and union leadership to communicate the next steps of this data collection process with employees. Be honest and realistic with employees about timelines for any solutions; emphasize that solutions are achieved over time and require ongoing communication and collaboration between parties.

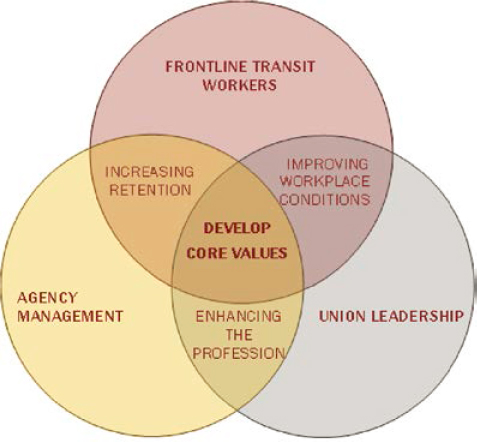

Step 2: Identify Common Goals

The next step to building trust is to take the feedback gained in Step 1 and identify common goals between parties. Although agencies, workers, and unions may have distinct issues that are

sometimes at odds with each other, there are undoubtedly common goals that can guide the collaborative development of solutions. For example:

- Agencies want to improve retention rates and identify strategies to improve the mental health and well-being of their workers.

- Unions want to improve the working conditions of their members and to create career pathways.

- Workers want a job that can offer them benefits that outweigh the difficulties of working in transit; they are looking for stability and a career.

In this case, all parties are looking for very similar outcomes. While issues with the methods for achieving these goals are bound to arise, if an agency and a union are committed to improving conditions for their workers, then any effort to implement change should be able to identify common solutions.

Union–agency partnerships that were developed to solve issues affecting operators have demonstrated success when they were conducted as a new effort based on shared goals (Figure 6.3). Some partnerships are conducted separately from the collective bargaining process to identify common goals rather than negotiate contract terms, which are based on differing interests. Collaborative efforts have seen success when there is buy-in on all sides, as well as champions who are willing to compromise to achieve common goals.

Tips for Identifying Common Goals

- Efforts should be coled by agency and union leadership to demonstrate trust and a united effort between leaders.

- Consider conducting partnerships separately from the collective bargaining process.

- Collaboration is most successful when there is buy-in from all parties: agency, union, and workers.

- Find a champion from each party, for each effort.

- Be willing to compromise.

Step 3: Develop Bottom-Up Solutions

The development of solutions is one of the most fundamental yet complicated aspects of trust building. Programs cannot be developed by one party as a solution for all, but rather as a collaborative investment that prioritizes the input of those most affected. At the core of solution development, agencies and unions need to listen to the changes and solutions their operators are proposing. Solutions should be developed from the bottom up to ensure that they are not seen as disconnected mandates imposed from the top or, worse, measures that make frontline workers’ jobs harder. By acknowledging that frontline workers understand their work best and are capable of creating innovative strategies, bottom-up solutions foster trust between agencies and frontline workers.

One important recommendation for solution development is the inclusion of a neutral third party that can identify commonalities across proposed solutions. Agencies and unions are often

The Joint Workforce Investment

The JWI was developed as a partnership between VTA and ATU Local 265 to improve retention rates and professionalize a career path for operators. Both union and agency members highlighted the importance of creating a safe space to speak about issues and solutions, where the collective bargaining process is separate from the program.

The JWI was created with common core values that prioritize operators: serving the public, creating workplace solutions, increasing professionalism, and improving health and wellness. See Case Study 9: Training and Mentorship for Retention and Advancement for more information.

at odds, so the inclusion of a neutral third party ensures shared leadership in the development of strategies and can foster open and honest communication, free from fear of retribution.

Amplify the Voices of Those on the Frontlines

Bottom-up solutions foster trust between agencies and frontline workers by acknowledging that frontline workers have agency and the capacity to create innovative strategies.

Tabletop Exercise: Building Trust

The worksheet in Table 6.14 provides issues identified through engagement with frontline workers, transit agency leadership, and union leaders. This role-playing exercise can be completed by agency managers or union leaders to understand how each party might view each situation or scenario. For this exercise, each person should be assigned one of three roles: frontline worker, union representative, or agency representative. All parties should participate in the exercise across all three steps: (1) Define the issues, (2) identify common goals, and (3) develop bottom-up solutions.

Table 6.14. Tabletop exercise: Building trust across parties.

| Situation | Define the Issues (How Does the Situation Affect Each Party?) | Identify Common Goals (What Are the Common Objectives Across All Parties?) | Develop Bottom-Up Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| The agency is dealing with low retention rates. Service is becoming less frequent, and drivers must take more shifts. |

Frontline Worker

Union Agency |

| Situation | Define the Issues (How Does the Situation Affect Each Party?) | Identify Common Goals (What Are the Common Objectives Across All Parties?) | Develop Bottom-Up Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operators have limited access to restrooms while on the job. |

Frontline Worker

Union Agency |

||

| Incidents involving passengers experiencing mental health crises are becoming more frequent. |

Frontline Worker

Union Agency |

||

| Incidents involving violent or aggressive passengers are becoming more frequent. |

Frontline Worker

Union Agency |

||

| The lack of exercise is having serious effects on the health of operators. Operators are taking more sick days due to the physical strain of the job. |

Frontline Worker

Union Agency |

| Situation | Define the Issues (How Does the Situation Affect Each Party?) | Identify Common Goals (What Are the Common Objectives Across All Parties?) | Develop Bottom-Up Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frontline transit workers are unaware of the existing resources available to them. There are several existing programs, but they are not used by employees. |

Frontline Worker

Union Agency |

||

| Frontline workers do not feel like there is a career path available within the agency. Internal promotions are few and far between. |

Frontline Worker

Union Agency |

Increasing Training Offerings