Launching Lifelong Health by Improving Health Care for Children, Youth, and Families (2024)

Chapter: 3 The Role of Children, Youth, Families, and Communities in Achieving Health Care System Transformation

3

The Role of Children, Youth, Families, and Communities in Achieving Health Care System Transformation

Getting health care should not require resilience. Health care should be prepared to deal with all families.

—Nikki Montgomery, Family Voice

As discussed in Chapter 2, clear scientific evidence demonstrates that safe, stable, and nurturing relationships are critical for healthy development and can buffer mechanisms of adversity and support positive trajectories for both children and youth. Children, youth, families, and the communities in which they live are therefore important partners across all facets of pediatric care, as they are experts in their health and health needs. They are also experts in how health care is currently delivered and have reported on the many challenges they encounter when seeking care. Disturbing trends in child health have prompted calls for the health care system, often characterized as industry centric and provider centric, to become child, family, and community centered (Neuwirth, 2019; see also Chapters 1, 2, and 4).

It is essential to understand the perspectives of children, youth, families, and communities on their health and health care needs. Their lived experiences and insights can provide valuable guidance for reimagining a more responsive health care system, and overlooking these perspectives, as illustrated in Figure 3-1, has led to the inefficiencies and distrust discussed in this chapter.

SOURCE: Anonymous child artist © Peace Child International, used with permission.

This chapter summarizes findings on common priorities for health care. It covers perspectives on the trustworthiness of the health care system and access to health care. It offers examples of how children, youth, families, and communities are currently engaged in decision making within the health care system. The committee acknowledges that children, youth, families, and communities are not monolithic entities. It is critical to recognize the diverse and intersecting identities that shape individual, familial, and communal experiences and health outcomes. While the chapter provides broadly applicable insights into health care system transformation, it underscores that effective and transformative actions must be tailored to address the unique needs and contexts of different groups.

CHILD- AND FAMILY-CENTERED HEALTH CARE

Patient experience has become an increasingly important focus in health care, with movement to encompass the overall quality of care from the patient’s perspective instead of just tracking clinical outcomes (Bastemeijer et al., 2019; National Academy of Medicine [NAM], 2023). The concept of patient- and family-centered care has emerged as a holistic approach to health care that emphasizes the importance of partnerships between health care providers, patients, and their families (Clay & Parsh, 2016; Hsu et al., 2019; Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care [IPFCC], n.d.). This model is particularly salient in pediatric health care, where the family plays a crucial role in children’s wellbeing (Meert, Clark, & Eggly, 2013; Seniwati et al., 2023). The goals of this approach are to improve health outcomes, enhance patient and family satisfaction, and ensure that care is respectful, responsive, and inclusive of the family’s needs and values (Clay & Parsh, 2016; IPFCC, n.d.; Hsu et al., 2019).

In this model, patients and families have the autonomy to define who constitutes their “family” and decide their level of involvement in care and decision-making processes (Hsu et al., 2019). Each child and family are recognized as unique, with specific needs and preferences (Clay & Parsh, 2016; IPFCC, n.d.; Hsu et al., 2019). Multiple studies have uncovered that patients want care that responds to their unique needs and actively involves them in care plans. These include studies on adolescents (Daley, Polifroni, & Sadler, 2017; see also Diaz et al., 2004; Fox, McManus, & Yurkiewicz, 2010; Ginsburg, Menapace, & Slap, 1997; Ginsburg et al., 2002; McIntyre, 2002; Rosen et al., 1997; Sadler & Daley, 2002; Tylee et al., 2007), pregnant people (Adalia et al., 2021; Jenkins et al., 2014; Petit-Steeghs et al., 2019), and families of children with special health care needs (Coker, Rodriguez, & Flores, 2010; Kuhlthau et al., 2011). For example, during interactions with health care professionals, adolescents desire to be treated as individuals and to engage in respectful communication with providers that helps them to better understand their health and treatment options (Hardin et al., 2021; Larcher, 2005). This includes accounting for concerns around sensitive health topics, including gender and sexual identity, drugs, sex, and mental health (Brown & Wissow, 2009; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [National Academies], 2023i).

COMMUNITY-CENTERED CARE

This report refers to communities as any configuration of individuals, families, and groups whose values, characteristics, interests, geography, and/or social relations unite them in some way (National Academies, 2017a). Community engagement in care or community-centered care is seen as the process of working collaboratively with and through groups of people affiliated by geographic proximity, special interest, or similar situations to address issues affecting their wellbeing (CDC, 1997). While communities are not a monolith, they generally expect pediatric health care system transformation to move beyond traditional medical models to more comprehensive, equitable, family-centered approaches that address the holistic needs of children and families in their communities (Center for Health Care Strategies, 2019a). In this vein, community engagement is a foundational aspect of developing effective health policies and programs (Aguilar-Gaxiola et al., 2022). The community mural in Figure 3-2 is an expression of the holistic health needs of families in a community.

“Community-defined” (or “practice-based”) evidence refers to the knowledge, experiences, and information generated and validated by a particular community to address its unique needs, challenges, and aspirations (California

NOTES: The Care We Create is a mural on the façade of the Westlake building of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in Los Angeles, California. The piece is a tribute to the enduring efforts of activists, organizers, and advocates across Southern California who have steadfastly fought and continue to fight for justice. Derived from the People’s Budget LA coalition, encompassing organizations such as Black Lives Matter—Los Angeles, People’s City Council, Ktown For All, and the TransLatin@ Coalition, the mural passionately advocates for diverting funds toward community care instead of policing. Collaborating closely with ACLU SoCal staff, coalition organizers generously contributed to the selection of portraits appearing in the mural. The individuals portrayed symbolize various issues such as racial justice in policing and legal matters, immigrants’ rights, LGBTQ+ rights, economic justice and housing, and First Amendment rights, as well as students and their rights.

SOURCE: Audrey Chan, The Care We Create, 2020. Painted mural and vinyl facade of the Los Angeles offices of the ACLU of Southern California (1313 West 8th Street, Los Angeles, CA 90017). Fabrication by the Los Angeles Art Collective and Wilson Cetina Group. Photo by Elon Schoenholz. Courtesy of the artist.

Pan-Ethnic Health Network, 2018; Isaacs et al., 2005). Box 3-1 details the California Reducing Disparities Project, an example of a community-defined evidence initiative. It encompasses a diverse range of locally relevant data, perspectives, and practices that may not fit traditional scientific or academic criteria but hold immense value within specific cultural, social, or geographic contexts (Bauer, Churchill et al., 2021). This type of evidence emphasizes the importance of community engagement, participation, and empowerment in defining, generating, and utilizing knowledge to inform decision making and problem solving. While evidence-based practices take a “top-down” approach (i.e., evidence is generated by researchers and then, with or without the partnership of communities, is implemented in target communities), community-defined evidence takes a more grassroots, “bottom-up,” approach, in which needs and practices are defined by communities, and then communities work to build evidence for these practices.

BOX 3-1

California Reducing Disparities Project

The California Reducing Disparities Project, a state-led initiative, has incorporated community-defined evidence to improve behavioral health outcomes across historically marginalized populations (California Pan-Ethnic Health Network [CPEHN], 2018). In 2009, a statewide policy initiative was launched that focused on prevention and intervention efforts for behavioral health conditions, with five priority populations: Latinxs, African American, LGBTQ, Native Americans/American Indians, and Asians and Pacific Islanders. The first phase of the project developed a strategic plan to transform the public mental health care system in California; the second phase focused on funding and evaluating these promising practices.

In 2022, the Children and Youth Behavioral Initiative (CYBHI) was established as part of a multiyear, public-sector investment of $4.7 billion in the behavioral health of children and adolescents in California. CYBHI was informed by community-defined practices in a report by CPEHN. It is currently scaling evidence-based practices, as well as promising community-defined practices, across several rounds of grant funding. In July 2023, the first round awarded over $30 million to 63 programs across California, with an emphasis on improving parenting support and practices. One example of a community-defined practice funded in the first round is the phidin ya’ ja’ (Celebrating Families Through Wellness) program that was awarded to the Sherwood Valley Band of Pomo Indians (n.d.). The program brings Native American families together to discuss issues related to boundary setting, healthy nutrition, drug and alcohol use, communication, and other skills to improve parenting practices.

As part of its deliberative process, the committee sought the input of a diverse group of individuals whose lived experiences and community engagement work intersects with the pediatric and maternal health care systems. Key takeaways from these information-gathering sessions1 included the need to welcome diverse forms of wisdom, including intergenerational and cross-cultural perspectives, the need to adopt practices of inviting and maintaining the presence of family leadership, the need to focus on language and communication exchanges for families and communities where literacy or access to information might be an issue, and the need to form partnerships with community entities to address holistic health needs. An important point was recognizing that members of a community are not necessarily hard to reach, as often believed, but engagement can be difficult if trust is not established (further discussion follows).

___________________

1 See Appendix C for agendas of public sessions. Further information on and archived recordings of these information-gathering sessions can be found at the project website: https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/improving-the-health-and-wellbeing-of-children-and-youth-through-health-care-system-transformation

SOURCE: Riley, 2023. Presentation to the Committee on Improving the Health and Wellbeing of Children and Youth through Health Care System Transformation.

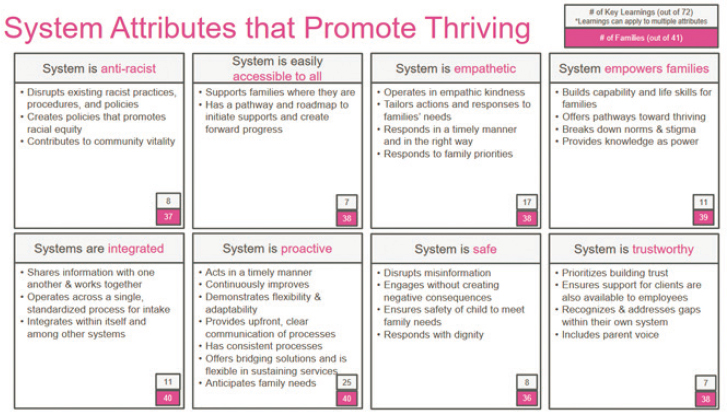

At one of these information-gathering sessions (June 15, 2023), Carley Riley spoke about Cincinnati Children’s Hospital’s increased commitment to and capacity for community-engaged co-production, in collaboration with All Children Thrive Learning Network Cincinnati. This initiative created a process to identify family-prioritized systems and policy changes to address their needs and hopes around equitable child and youth thriving.2 Eight ideal system attributes were determined to promote thriving: antiracist, accessible to all, empathetic, empowering to families, integrated, proactive, safe, and trustworthy (Riley, 2023; Figure 3-3).

The eight ideal system attributes for health care systems transformation promote a holistic approach to improving health outcomes and experiences for all individuals, families, and communities (Riley, 2023).

- The first attribute is being antiracist. An antiracist system actively works to dismantle systemic racism and promote equity in health care delivery and outcomes (Hassen et al., 2021). An antiracist health care system acknowledges the historical and ongoing impacts of racism and takes deliberate action to create racial equity (NAM, 2023).

___________________

2 This initiative included a recruitment period from November 2020 to May 2023, during which 44 families referred from school, community, and health care settings engaged for a median of 4 months in a multidisciplinary, cross-sector community–academic team process that co-developed a family-centered learning process.

- The second attribute is being accessible to all. This ensures that health care services and resources are readily available and easily obtainable for all individuals, regardless of their socioeconomic status, geographic location, or other potential barriers (Levesque, Harris, & Russell, 2013; Qi et al., 2023). Accessibility encompasses physical, financial, and cultural dimensions of access (Douthit et al., 2015; Thiede, Akweongo, & McIntyre, 2007).

- The third attribute is being empathetic. An empathetic health care system prioritizes compassionate care, understanding and addressing the emotional and psychological needs of patients and families (Hardy, 2022; Kerasidou et al., 2020; Moudatsou et al., 2020). This involves training providers in empathic communication and creating environments that support emotional wellbeing.

- The fourth attribute is being empowering to families. This means families are actively involved in decision-making processes and are provided with the necessary tools and information to manage their health effectively (Coyne, Holmström, & Söderbäck, 2018; Kubb & Foran, 2020; Kuo et al., 2012; Lorig & Holman, 2003). An empowering system recognizes families as partners in care and supports their capacity for self-management (Kuo et al., 2012).

- The fifth attribute is being integrated. An integrated system promotes seamless coordination and collaboration among various health care providers, services, and sectors to ensure comprehensive and continuous care (American Hospital Association, 2021; American Psychological Association, n.d.; World Health Organization [WHO], 2018). This reduces fragmentation and improves the patient experience across the care continuum.

- The sixth attribute is being proactive. A proactive system focuses on prevention and early intervention, addressing potential health issues before they escalate (Lobach et al., 2007). This involves population health management strategies and leveraging data to identify and address health risks (Lobach et al., 2007).

- The seventh attribute is being safe. In a safe health care system, patient safety is paramount, with systems in place to minimize errors, adverse events, and harm to patients. This involves a culture of safety, robust reporting systems, and continuous quality improvement efforts (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2020; Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2000; WHO, n.d.c.).

- The eighth and final attribute is being trustworthy. A trustworthy system fosters trust through transparency, accountability, and consistent delivery of high-quality care. This involves clear communication, ethical practices, and responsiveness to patient and community needs (IOM, 2000; Weaver et al., 2013).

These eight attributes collectively aim to create a health care system that is equitable, patient centered, and effective in improving overall population health. By striving to embody these attributes, health care systems can work toward transforming care delivery and addressing long-standing disparities in health outcomes (Riley, 2023).

COMMON CHALLENGES TO COMMUNITY-CENTERED CARE

Existing endeavors to advance health care transformation often fail to address health care system challenges and to include people with lived experience in their development and evaluation, resulting in a misalignment. Using the broad attributes of a thriving system above as a guide, this section explores the existing literature on challenges related to trustworthiness in the health care system; access to health care; and individual-level disempowerment.

Trustworthiness of Health Care Institutions

Trustworthiness has been identified as a key tenet of a health care system that promotes thriving (Riley, 2023). Unfortunately, many children, youth, families, and communities have reason to be wary of health care professionals and the broader health care system. A review of historical polling data by Blendon, Benson, and Hero (2014) on public trust in U.S. physicians and medical leaders from 1966 through 2014 found that public trust and confidence in U.S. medical leaders has declined sharply since the mid-20th century. The authors suggest that the overall decline in trust in U.S. health care is likely attributable to broad cultural changes in the United States, along with concerns around medical system leaders’ responses to major national problems impacting the U.S. health care system (Blendon, Benson, & Hero, 2014; Buhr & Blendon, 2011; Hetherington, 2005). These findings are echoed in survey results on trusted sources of health information on COVID-19 (Steel-Fisher et al., 2023).

Mistrust of the health care system, especially in communities of color in the United States, is grounded in current experience with structural inequities that permeate health care and other systems, as well as with the legacy of health care discrimination; medical research exploitation; and unconsented experimentation, particularly for Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, Hispanic, and other communities that have experienced racism in the United States (Frakt, 2020; Gamble, 1997; Hoffman, 2020; National Academies, 2020c). This section discusses encounters with unethical research and medical practices, practitioner bias, and misinformation and disinformation, which have all served to foster mistrust between the health care system and those it serves. Box 3-2 provides an illustrative personal narrative, informed by research and clinical practice, regarding distrust in the health care system and opportunities for building community trust.

BOX 3-2

Illustrative Example: Building Community Trust—Renée Boynton-Jarrett

For Renée Boynton-Jarrett, health care systems, like other institutions, are not automatically entitled to trust. Boynton-Jarrett’s view is informed by her deep background in the sociology of health: an associate professor at Boston University School of Medicine, she is trained as both an anthropologist and a pediatrician. From that perspective, the literature is clear: “Trustworthiness is a requisite condition to foster trust,” she said—in other words, institutions must earn trust.

In her clinical life, Boynton-Jarrett sees the other side of the coin: populations historically marginalized—and sometimes harmed—by medical institutions may hesitate to pursue recommended care. In some ways, that can be frustrating, she said. At the same time, Boynton-Jarrett gets it. “In the absence of trustworthiness, distrust is only rational,” she said. “It’s actually really rational to not trust an institution that has time and time again demonstrated a lack of trustworthiness.” That distrust too often comes with a double hit. Not only do these communities forgo care that could help them, she continued, but too often these “minoritized and marginalized populations” are stigmatized further when “the blame falls squarely on the[ir] shoulders.”

However, the thorny challenge of distrust is solvable, Boynton-Jarrett said. To her, there are three key ingredients:

First, invest in “community power and capacity building,” she said. That means setting up structures—closely tied to traditional health care systems—that build up the civic society of communities in ways that support health. Community health worker programs are a common example, she pointed out. Infrastructure networks and safety nets, such as the Boston Breastfeeding Coalition—a member-led initiative that promotes breastfeeding education and access—is another. “When I’m thinking about healing and thriving, I’m thinking about a whole child, person-centered, family-centered [approach],” Boynton-Jarrett said. “I think about it in the context of relationships.”

Second, she continued, “Recogniz[e] the abundance of leadership at the ready to actually support thriving and flourishing for children.” Investing in organizations alone is insufficient for creating meaningful or long-term impact, she asserted; health care systems must also lift up the people who operate and drive them forward—granting them both “authority” and “agency” in the same ways it uplifts its own employees. “When I think about culturally affirming models of care, I think about wisdom and knowledge that are held in the community with high levels of expertise—without a medical degree or a high set of academic credentials,” Boynton-Jarrett said, “and [I think] about us valuing them equally.”

Third, she urged, “Recenter voice, story, and experience.” These practices are critical for ensuring that health care systems address the right problems—for example, a breastfeeding coalition is useful only on paper if voices from the community say the more pressing needs are elsewhere. Recentering voice, story, and experience is also essential for fostering true inclusion and collaboration between institutions and communities. In this manner, health care systems must “cente[r] dignity to promote equity,” Boynton-Jarrett said. “One of our strongest mental models is that health care functions as an independent system,” she added; “we c[an] challenge that idea.”

Boynton-Jarrett is practicing these lessons through the Vital Village Network, an organization built with the three key ingredients in mind—designed, ultimately, to advance trust, rather than any specific intervention. “When we use the words ‘child wellbeing and wellness,’ it is very problematic to narrow that to a model that is devoted to reducing risk, reducing harm, and treating harm,” Boynton-Jarrett said. “I’m very much an advocate for us broadening the scope of how health care contributes to wellbeing.” Her goal in fostering trust is not only to understand what lies below the surface of the iceberg of illness when it comes to these communities, but also to understand “what keeps the water cold,” Boynton-Jarrett said—the forces that drive negative outcomes. Only then, she said, will health care systems support flourishing childhood—beyond risk reduction and harm alleviation.

Health care “is not just about how someone recovers,” Boynton-Jarrett said, “It’s about how someone can thrive.”

SOURCE: Correspondence with Renée Boynton-Jarrett, prepared by Eli Cahan, health communication advisor to the committee.

Historical and Contemporary Instances of Unethical Research and Medical Practices

Black people have been historically and continually subjected to intentionally inferior health care access and delivery and poor health outcomes; and ongoing health care system disparities and discriminatory events reinforce historical mistrust (Scharff et al., 2010). For instance, eugenic sterilization laws, which promoted forced reproductive sterilization, were prevalent throughout the United States until the mid- to late 1940s and were routinely used to rationalize the mistreatment of non-White individuals, people with attenuated financial means, and those who were neurodivergent (Reilly, 2015). Such practices continued to be used against the same populations beyond the 1940s, and some have suggested that they are still in use.

Between 1920 and 1945, sterilization laws in California were applied to Latinos disproportionately (Novak et al., 2018). From the 1940s to 1970s, the organization Birthright facilitated the sterilization of Black women, women living in rural areas, and women who were economically marginalized (Reilly, 2015). Moreover, the Indian Health Service is accused of using mass sterilization against Native American women throughout the 1960s and 1970s, and studies have shown that between

25% and 50% of childbearing-age Native American women lost their reproductive ability between 1970 and 1976 (Lawrence, 2000). Most recently, immigrant detainees have reported experiencing forced sterilization while in U.S. Immigrant and Customs Enforcement custody (Ghandakly & Fabi, 2021). Forced sterilization negatively impacted individuals, families, and communities, as evidenced by ruptured family and community relationships; increased susceptibility to psychological distress, substance abuse, and mental health impairment; and decreased economic freedom (Lawrence, 2000).

Unethical research practices have significantly contributed to mistrust in health care systems. Notable examples span several decades and highlight the evolution of research ethics, particularly concerning vulnerable populations. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study (1932–1972) stands as one of the most infamous cases of unethical research. Although not directly involving children, it set a precedent for mistrust in medical research. Researchers studied the effects of untreated syphilis in Black men without their informed consent, denying them treatment even after penicillin became available (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2022a). This study’s impact rippled through generations, affecting attitudes toward medical research in minority communities.

A recent study by Alsan and Wanamaker (2018) comparing older Black men with other demographic groups, before and after the information about the Tuskegee study was revealed and in varying proximity to the Tuskegee study’s victims, found that the public disclosure of the study in 1972 was associated with increases in both medical mistrust and mortality, and decreases in both outpatient and inpatient physician interactions for older Black men, with the largest effects found for Black men living in closest in geographic proximity to Tuskegee. Alsan and Wanamaker (2018) estimate that life expectancy fell for Black men by up to 1.5 years in response to the public disclosure of the Tuskegee study, accounting for approximately 35% of the reported life expectancy gap between Black and White men in 1980.

Several studies directly targeted children, often without proper consent or consideration for their wellbeing. The 1936 Monster Study, conducted by Wendell Johnson, experimented on orphans by assigning them to “stutter” and “normal speaker” groups regardless of their actual speech patterns (Erard, 2001). Children in the “stutter” group developed speech impediments, withdrawal, and speech refusal as a result. The negative psychological impact on the children labeled as stutterers led to these harmful outcomes, demonstrating the potential for severe adverse effects from unethical research practices on vulnerable populations such as children (Erard, 2001). Similarly, the Robbers Cave Experiment in the 1950s, led by Muzafer Sherif, manipulated 11-year-old boys to study

intergroup conflict. The study subjected participants to hostile interactions and psychological distress without parental consent or the option to withdraw (McLeod, 2023).

Other controversial studies involving children include the Little Albert Experiment, where John Watson conditioned an infant to fear harmless objects (Watson & Rayner, 1920), and child aggression studies on Black and Hispanic boys aged 6–10 years, which exposed them to potentially harmful situations (Klitzman & Kelmenson, 2020). The Willowbrook Hepatitis Experiments took ethical concerns to new heights by intentionally infecting institutionalized children with hepatitis to study the disease’s progression and potential treatments (Krugman, 1986).

These studies, conducted before the establishment of institutional review boards in 1974, highlight the critical need for strict ethical guidelines in research involving children. They serve as stark reminders of past transgressions and underscore the importance of protecting vulnerable populations in scientific research. The legacy of these unethical practices continues to influence public perception of medical research and emphasizes the ongoing need for transparency, informed consent, and rigorous ethical oversight in all human studies.

Additionally, many children and youth participate in research that is subsequently unpublished and in turn does not help to advance scientific knowledge. Pica and Bourgeois (2016) found that out of 559 randomized clinical trials involving children, 104 were discontinued early and 136 that were completed did not result in publication of findings.

Present-day distrust and mistrust can be attributed to past institutional failures and conceptualized as a rational response aimed at protecting against future harm (Griffith et al., 2021; Nweke, Isom, & Fashaw-Walters, 2022; Platt, Jacobson, & Kardia, 2018). Specifically, Griffith and colleagues (2021) identified an enduring trend of substandard care as one factor contributing to distrust among historically marginalized communities, and they identified unethical research as facilitating mistrust in the current health care system. Moreover, Miller and Miller (2021) argue that this legacy of injustice and violence toward Black bodies feeds into the collective experience of transgenerational trauma within the Black population, which fundamentally undermines trust between Black patients and their physicians.

Finally, Platt, Jacobson, and Kardia (2018) found that a majority of the U.S. population has diminished confidence in the trustworthiness of the overall health care system. Numerous efforts are under way to rectify historical harms while rebuilding trust between the health care system and communities. Yet ongoing patient reluctance and health care disparities suggest these efforts are not achieving their desired outcomes. Future research is needed to elucidate how past mistreatment influences individual-level health care engagement and impacts health equity.

Practitioner Bias

Practitioner bias, frequently intertwined with the racial bias discussed in Chapter 2, can also contribute to mistrust in the health care system among children, youth, families, and communities (see, e.g., Blair, Steinerc, & Havranek, 2011; Canedo et al., 2018; FitzGerald & Hurst, 2017; Hall et al., 2015; Kugelmass, 2016; Vela et al., 2022). In pediatric health care, “practitioner bias” refers to the potential for health care providers to exhibit subjective judgments or preferences that may impact their decision making, diagnosis, and treatment of pediatric patients (Johnson et al., 2017; Schnierle, Christian-Brathwaite, & Louisias, 2019). This bias can stem from various factors, including personal beliefs, cultural background, stereotypes, or lack of awareness about one’s own biases (Schnierle, Christian-Brathwaite, & Louisias, 2019). It is essential to recognize bias as a normal but malleable aspect of human cognition, and to address practitioner bias in pediatric health care through targeted solutions that are rigorously tested across all levels of care (Raphael & Oyeku, 2020).

Several studies have explored the concept of bias in pediatric health care, highlighting how implicit and explicit biases contribute to experiences of racism and discrimination. It has been consistently documented that historically marginalized racial and ethnic populations are overrepresented among those who experience substantial pain yet receive inadequate pain management (Goyal et al., 2020; Mossey, 2011; Sabin & Greenwald, 2012). Research conducted in pediatric emergency departments has revealed disparities based on race and ethnicity in the management of analgesics for children who present with acute abdominal pain, sickle cell disease, and appendicitis (Fearon et al., 2019; Goyal et al., 2015; Johnson et al., 2013; Raphael & Oyeku, 2020). Disparities in both process and outcome measures based on race and ethnicity have also been observed in emergency departments’ management of pain in children with long-bone fractures (Goyal et al., 2020). Despite a higher likelihood for historically marginalized children to receive analgesics and experience more than a 2-point reduction in pain, they are less likely to receive opioids and achieve optimal pain reduction (Goyal et al., 2020). In addition, research has also shown that some providers perceive Black individuals as less likely than White individuals to adhere to medical advice, a perception that contributes to poor communication and care (Laws et al., 2014; van Ryn & Burke, 2000).

Gender bias is another barrier to achieving health equity, and predominantly impacts two aspects of health care (Carrilero et al., 2023). First, it can influence the diagnosis, affecting medical history, physical examinations, and the implementation of additional tests (Criado, 2019). Second, it plays a role in therapy, as the communication style and dynamics of the professional–patient relationship may vary based on whether professionals and patients share the same gender (Carrilero et al., 2023). Gender-diverse people are also

known to be at a greater risk for health disparities and for trauma as a result of mistreatment in a health care setting (Sherman et al., 2021).

Patients and families often cite mistrust of health care practitioners as a barrier to engagement, and evidence shows that practitioners do not always trust their patients (e.g., undertreatment of pain for women and people of color; failure to take health concerns, particularly women’s concerns, seriously; failure to listen to patients’ initial concerns without interruption; Curtis et al., 2019; Khan, Ramotar, & Landrigan, 2019; National Partnership for Women & Families, 2023). For example, practitioner bias has been shown to be detrimental to Black maternal health because of parents’ concerns being minimized or dismissed, resulting in increased infant and maternal mortality within the community (Saluja & Bryant, 2021). Furthermore, some research suggests that Black women are less likely than their White counterparts to receive an epidural during childbirth because of providers’ beliefs about the relationship between race and pain tolerance, as well as poor communication in racially discordant provider–patient relationships (National Academies, 2021a,c).

Additional reporting from 2020 by Public Agenda surveyed trust between people with Medicaid and primary care doctors. The report found that many participants from Medicaid focus groups described feeling disrespected or distrusted by their providers because of their race and insurance coverage (Silliman & Schleifer, 2020). However, Silliman and Schleifer (2020) also reported that primary care doctors largely identified patients with Medicaid coverage as equally trustworthy as those with other forms of insurance, and as more trustworthy when they are actively engaged in care. Relatedly, studies have shown that race, ethnicity, and poverty influence child maltreatment reporting in hospital settings (Rebbe, Sattler, & Mienko, 2022). For example, Rebbe, Sattler, and Mienko (2022) conducted a record review of children hospitalized for maltreatment; using diagnostic codes, they found that Native American families and children with public health insurance were more likely than those with private insurance to receive a maltreatment diagnosis code (a strong predictor of being reported to child protective services).

Misinformation and Disinformation

The growing prevalence of misinformation and disinformation3 has eroded trust between the health care system and children, youth, families, and communities in recent years. As stated by the U.S. Surgeon General,

___________________

3 “Disinformation” refers to false information that is deliberately created and spread with the intention to deceive or mislead (WHO, 2024). Unlike misinformation, which may be shared without malicious intent, disinformation is designed to cause harm, sow discord, or undermine trust in health care institutions, scientific experts, and public health agencies (WHO, 2024).

“Health misinformation is a serious threat to public health. It can cause confusion, sow mistrust, harm people’s health, and undermine public health efforts” (Murthy, 2021, p. 3). “Misinformation” is defined as “information that is false, inaccurate, or misleading according to the best available evidence at the time” (Murthy, 2021, p. 3).

For example, the lack of professional consensus regarding treatment and care during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, given the novelty of the virus, exacerbated people’s mistrust of the health care system, as new developments necessitated revised guidance (Frenk et al., 2022). During this period, misinformation and disinformation were also amplified across social media platforms leading to additional mistrust of the health care field (Benoit & Mauldin, 2021). National surveys conducted in 2022 and 2023 reflect polarized public opinions about the health care system and its actors (Del Ponte, Gerber, & Patashnik, 2023; Steel-Fisher et al., 2023). In this climate of polarization, misinformation and disinformation can thrive.

For pediatrics, controversy on the care of children with gender dysphoria has also been a flashpoint for polarization and misinformation, with implications for these children and families and far reach to other policies. While gender-affirming care has now been limited by more than 20 state legislatures, its prohibition has been also attached to many other pediatric policies unrelated to gender-affirming care (e.g., funding for graduate medical education in children’s hospitals, Medicaid participation).

The National Academies conducted a roundtable in December 2020 on addressing misinformation (National Academies, 2020a), finding that technology use plays a pivotal role, as a high percentage of those who use the Internet search for information around health. Misinformation is disseminated online, which also drives inequity, because the consequences of misinformation “disproportionately affect communities of color, communities with lower socioeconomic status, and queer communities” (National Academies, 2020a, p. 2). The report highlighted several strategies for combatting misinformation, including using fact-checking organizations; promoting health literacy; using digital platforms; and promoting science literacy, specifically “understanding the uncertain and evolving nature of science” (National Academies, 2020a, p. 6).

Access to Health Care and System Fragmentation

Health care experiences vary greatly depending on where families seek care. Presently, health care is a largely fragmented, disjointed system lacking care coordination. Communication across systems is often limited, resulting in minimal reciprocal communication between systems and incomplete information shared with families about next steps. As a result, patients and families are forced to navigate complex, heterogenous health care systems (see Chapter 5). The delivery of health care spread across an

excessively large number of poorly coordinated providers is a significant source of inefficiency in the U.S. health care system (Agha, Frandsen, & Rebitzer, 2019). Regional differences in practice styles contribute to varying levels of care fragmentation. Regions with higher levels of fragmentation are associated with increased care utilization and hospitalizations, suggesting that consistent relationships with primary care providers may reduce the demand for hospital care. Recent antifragmentation initiatives aim to reduce costly silos of care by altering provider financial incentives, but the effectiveness of these initiatives remains to be fully understood (Agha, Frandsen, & Rebitzer, 2019; see also Chapter 5).

Other issues regarding access to health care involve the availability, churning, and state variations of health care insurance (see Chapter 6), as well as the proximity and availability of needed health care, particularly for rural communities (see Chapter 5).

Individual-Level Disempowerment: Literacy, Language, and Cultural Congruence

In addition to trustworthiness and fragmentation of the health care system, families have also identified challenges with individual-level disempowerment when engaging with the health care system. Individual characteristics playing into these challenges include limited parenting knowledge and skills (including knowledge about prevention and children’s health care needs), limited understanding of diagnosis and treatment options, and level of health literacy.4 A large body of research focuses

___________________

4 Sykes and colleagues (2013) describe “critical health literacy” as “a set of characteristics of advanced personal skills, health knowledge, information skills, effective interaction between service providers and users, informed decision making and empowerment, including political action” (para. 1). The potential consequences of critical health literacy, under this definition, are “improving health outcomes, creating more effective use of health services, and reducing inequalities in health” (Sykes et al., 2013, para. 1). Using a critical health literacy framework, Gould and colleagues (2020) identified three levels of literacy: functional, interactive, and critical (see also Nutbeam, 2000). The levels can be described using safe sex as an example (National Academies, 2021f):

Functional literacy would entail providing individuals with facts about having safe sex. Interactive health literacy would be reached when people have learned how to communicate about having safe sex and are able to problem solve and independently make decisions about safe sex. Critical health literacy, which is not taught much in the United States today [...] is about an individual’s understanding of the SDOH and their ability to take action at both the individual and the community level (p. 2).

In this example, critical health literacy would come into play when a safe sex problem is identified in the community (e.g., high levels of sexually transmitted infections or unplanned pregnancies) and the question is asked: “How can the community take action on the problem?” (National Academies, 2021f, p. 2).

on health literacy and physician–patient communication and patient outcomes. Belasen, Oppenlander, and Belasen (2020), for example, examined the relationship between provider–patient communication and data in the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems, noting that communication between health care providers and patients is a determinant of patient outcomes.

Language barriers have been shown to increase adverse health outcomes, such as having difficulty understanding instructions on how to take a medication (Al Shamsi et al., 2020). Moreover, families have reported language barriers, including lack of professional interpreters or use of informal ad hoc interpreters (Elderkin-Thompson, Silver, & Waitzkin, 2001), nontranslated or incorrectly translated health materials (Flores et al., 2000), and resources that are not tailored to be culturally appropriate or relevant (Falbe et al., 2015; Lopez et al., 2019; McCurley, Gutierrez, & Gallo, 2017). With over a quarter (26.3%) of children under age 18 in the United States living with at least one foreign-born parent, cultural and language challenges are common in the pediatric health care setting (Anderson & Hemez, 2022).

Research has also linked cultural competency or humility, cross-cultural communication (language proficient providers and families), and patient–provider racial/ethnic congruence to increased health care engagement and perception of quality care. For example, racial concordance between patient and physician has been associated with reduced health disparities and increased patient satisfaction (Alberto et al., 2021; Greenwood et al., 2020; National Academies, 2023g; Takeshita et al., 2020). A previous National Academies report, In the Nation’s Compelling Interest: Ensuring Diversity in the Health-Care Workforce, found that a more diverse health care workforce increases access to care for historically marginalized patients, improves patient choice and satisfaction, results in better patient–provider communication, and ultimately can produce better quality of care for all Americans (Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2004).

In a study of maternal mental health care, Matthews and colleagues (2021) conducted a series of focus groups and structured interviews to identify antiracist solutions to inequities in maternal care. The authors reported (Matthews et al., 2021):

Several participants expressed the need for services informed by cultural humility and holistic care, which is inclusive of dignified, respectful, humane, and empathetic care. [. . .] Active listening, answering a client’s questions, intentionally dismantling power dynamics, creating “brave spaces” (environments that foster critical dialogue and acknowledge varying perceptions and realities of safety) were reported as important strategies to build trust and respond to a client’s needs holistically. (p. 1600)

STRATEGIES FOR IMPROVEMENT

Fostering confidence and overcoming mistrust in the health care system requires strong relationships and an infrastructure that supports addressing the structural factors that create disparities in health outcomes. This section summarizes some of the strategies aimed at building trust. These include prioritizing health equity, family and community voice, a cultural humility in the health care workforce, patient- and youth-led services, and leveraging local anchor institutions.

Health care that centers on partnerships, strengths, and equity provides children with the greatest opportunities to receive care and resources to support their lifelong development. The joyful faces of these young Black children in the mural in Figure 3-4 serve as a powerful reminder of the importance of cultivating cultural humility, empathy, and antiracist practices in all areas of health care and social services, to ensure equitable, compassionate, and affirming support for children and families of color.

Advancing Health Equity with Communities

Building trust in health care systems, particularly with communities of color, needs to begin with acknowledgment of existing inequities and pursuits to combat such inequalities in communities (National Academies, 2021b,c). The 2017 National Academies report Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity shared the significance of the role of communities in promoting health equity. The report concluded that community-driven solutions are necessary, as communities are in a unique position to

SOURCE: Brent Billingsley, Cincinnati, OH. Photo by Pixxel Designs. Courtesy of the artist.

drive priorities and actions tailored to their needs that address many of the determinants of health (National Academies, 2017a, p. 179). In addition, the report encourages enhanced engagement of patients, families, and communities as a strategy in health policy change, research, and care delivery to improve the quality of care and drive health equity (National Academies, 2017a, p. 237). Reframing the health care system around the experiences, needs, and considerations of patients, families, and communities is a necessary precondition to achieve the values of equity, efficiency, and effectiveness. See Box 3-3 for a personal narrative of Tamela Milan-Alexander as she reflects on linking health care to community experiences.

Children, families, communities, providers, and other engaged stakeholders consistently identify achieving health equity as a fundamental goal. Achieving equity will require multilevel and multipronged strategies and interventions at the policy, system, and program levels to align with science and evidence around equity outcomes and to distribute resources to where they are needed most (National Academies, 2019a,c,d). The Center for Health Care Strategies (CHCS) brief Engaging Communities of Color to Promote Health Equity (2022) suggests partnering with patients and community members of color to understand their needs and preferences as an initial step toward improving health outcomes and advancing health equity (Spencer & Ohene-Ntow, 2022). This initial step can facilitate longer-term relationships that may develop into trusting and collaborative relationships between engaged parties. In its assessment of the experiences of learning collaborative participants across New York–based health care organizations, CHCS distilled five broadly applicable lessons for better understanding patient experiences and addressing long-standing health disparities (Spencer & Ohene-Ntow, 2022):

- Build trust with patient partners over time;

- Tailor outreach strategies to resonate with patient populations;

- Use trauma-informed approaches to strengthen relationships with patient partners;

- Collect and use data in partnership with patients; and

- Approach patient engagement with humility and patience (p. 2).

Building Trust through Engagement of Children, Families, and Communities

Engaging children, families, and communities is critical to overcoming the challenges identified in the previous section—specifically, engagement is critical to overcoming mistrust and building confidence in the health care system. Building trust requires a strong infrastructure and relationships that support organizing for policy change, providing accessible care, listening to the needs of communities, addressing the structural factors that create disparities in health outcomes, and ensuring measurement and transparent

BOX 3-3

Illustrative Example: Community Engagement—Tamela Milan-Alexander

Tamela Milan-Alexander grew up on Chicago’s West Side. “I definitely sought, outside the home, for different forms of recognition and acceptance,” Milan-Alexander said, “I felt smothered [. . .] and it was exciting to be out—to be in the hood, so to speak.”

“But of course,” she added, “that excitement led to some pivotal changes in my life.”

By age 17, Milan-Alexander was pregnant. By age 18, she had her first child. By age 20, she was in a relationship riddled with domestic violence. And soon thereafter, she started using drugs, including crack cocaine. Things quickly spiraled as she found herself within the grips of dependency. “At some point it became physically necessary to my existence—the sickness of it became debilitating,” Milan-Alexander said, “Every day was a day to use.”

It was a challenging time to have a substance use disorder. People using crack cocaine faced harsh judgment. Despite her awareness and insight into her condition, Milan-Alexander did not feel that she could turn to the health care system. She could not share what was going on, and she could not ask for help. If anything, health care itself represented a threat rather than a safety net. “There was this fear of—or distress related to—the system,” Milan-Alexander said, “There was this environment of, you know, health care could take your kid.”

Eventually, Milan-Alexander did get help for her addiction—and eventually, she was able to overcome it. But she remembers how it felt to be marginalized from—and threatened by—the health care system. Some days, actually, Milan-Alexander still feels it, such as in interactions as simple as a vaccination visit: “That fear factor [is] ever present,” she said.

reporting of inequities (National Academies, 2021d). Patients and families generally desire to be involved and engaged in health care decisions; however, this desire varies depending on the individual, the number of treatment options available, and the certainty of those treatment options (Blumenthal Kostick, et al., 2015). Robust trust levels contribute to confidence, peace of mind, and a sense of security. Conversely, shattered trust can result in anxiety, second-guessing, and frustration (Sisk & Baker, 2019).

Most principles of engagement directly promote fostering trust. Frameworks of patient and family engagement can be understood as falling into one of three levels along a continuum: listening and advising, co-creation and co-design (Durrah, 2023a,b,c).

Listening

Listening involves point-of-care interactions where patients, families, and care team members engage in mutual respect, trust, and communication (Durrah, 2023b). This level of engagement is crucial for building trust

So, these days, Milan-Alexander is fighting to connect communities like hers with the health care system in ways she never benefited from. That means ensuring there are “access points” to health care for parents struggling with addiction, such as during a child’s routine physical, she said. It could also mean working with the state’s department of education to provide foundational care for families in school-based health centers—which are often more physically and emotionally accessible than are hospitals. This is the focus of the initiative her organization, EverThrive Illinois, is undertaking.

Health care systems need to form meaningful partnerships with the specific communities they serve, Milan-Alexander said. That could mean broadening colon cancer screening in one community, medication-assisted treatment in another, or physical therapy in a third. That also means health care systems ought to move from the gospel of the “melting pot” to that of the “salad bowl,” she said.

“I can’t ask a mushroom what a tomato is doing—I can’t be a carrot and a cucumber at the same time,” Milan-Alexander said, “the ingredients are very different, very unique to themselves—they [must be] separated out, and acknowledged for the differences they show.”

And, practically, it means health care systems need to look outwards for both inspiration and impact. “Look outside the four walls,” Milan-Alexander said, “if you don’t know what’s outside the walls, you don’t know what’s going on.”

Only then, she said—when health care systems truly meet families where they live, when they include the community institutions that families attend as equal partners—will parents, and their children, truly be able to thrive.

SOURCE: Correspondence with Tamela Milan-Alexander, prepared by Eli Cahan, health communication advisor to the committee.

because it ensures that patients and families feel heard and valued. For example, family-centered rounds, where providers include patients and families during bedside rounds, demonstrate respect and openness, which are essential for building trust (Carman et al., 2013; Durrah, 2023b). Effective communication by providers can significantly impact patient satisfaction, willingness to follow medical advice, and adherence to treatment plans (Boudreaux & O’Hea, 2004; Dorsey et al., 2022; Hall, Roter, & Rand, 1981; Herndon & Pollick, 2002; Kaplan, Greenfield, & Ware, 1989; Roter, 1983).

Advising

Advising involves patient and family advisory councils, where patients and families provide input on health care practices and policies. While this level of engagement still places decision-making power primarily with providers, it is a step toward more inclusive practices (Durrah, 2023b). Building diverse advisory councils and compensating advisors can enhance trust by showing a commitment to inclusivity and valuing the contributions

of all community members (Durrah, 2023a,b; Van Veen, 2014). Engaging advisors from historically marginalized communities and providing educational opportunities can build trust by ensuring that all voices are heard and respected (Durrah, 2023b).

Eliminating barriers to financially compensate patients and families for their participation in health care improvement efforts is crucial for ensuring diverse representation and meaningful engagement (Spencer & Ohene-Ntow, 2022). Financial compensation acknowledges the value of patients’ time and expertise while addressing socioeconomic barriers to participation (Domecq et al., 2014). The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2018) and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (2015) both emphasize the importance of this practice for better outcomes. However, health care organizations often face regulatory and administrative barriers in providing such compensation, including concerns about violating antikickback statutes and complexities in accounting (Deverka et al., 2012). Addressing these barriers requires policy changes, clear organizational guidelines, and education of health care administrators. Some health care systems, such as the University of Vermont Medical Center (2020), have successfully implemented compensation programs, leading to increased diversity in advisory councils and more impactful care improvements. By overcoming these barriers and establishing equitable compensation practices, health care organizations can foster more inclusive and effective improvement efforts, aligning with principles of health equity and patient-centered care (National Academies, 2019d).

Co-Creation and Co-Design

Co-creation and co-design represent the highest level of engagement, where patients, families, and communities are equitable partners in health care system transformation (Durrah, 2023a,b,c). This approach is built on shared power and responsibility, fostering active partnerships and shared decision making. By involving stakeholders in the design and implementation of health services, trust is built through transparency, collaboration, and mutual respect (Silvola et al., 2023). Co-creation and co-design ensure that health services are tailored to the real needs and desires of patients, which is essential for building trust (Silvola et al., 2023). These approaches have been used to improve health equity and promote accountability, further enhancing trust within communities (Andrews, Sahama, & Gajanayake, 2014; Reopell et al., 2023; Roche et al., 2020). Co-creation and co-design can be applied at the practice, system, research, and policy levels, but they require leadership support, flexibility and nimbleness, sharing of power and resources, and funding. Box 3-4 describes Southcentral Foundation’s Nuka System of Care, an example of a transformative model for a health care system that is coproduced with customer-owners.

BOX 3-4

Southcentral Foundation’s Nuka System of Care

Southcentral Foundation’s (SCF’s) Nuka System of Care is a relationship-based, Alaska Native–owned health care system. Relationships are a core concept within the Indigenous worldview, and the Nuka system was designed to center relationships across the spectrum of care (Healey, 2017). Based in Anchorage, Alaska, SCF’s Nuka system evolved out of the consumer-driven overhaul of the formerly centralized health care system overseen by the Indian Health Service (Gottlieb, 2013). Today, the nonprofit organization serves roughly 65,000 Alaska Native and American Indian people across Anchorage, the Matanuska-Susitna Borough, and 55 rural villages in the Anchorage Service Areaa (Healey, 2017). The Nuka system recognizes health as not just the absence of illness but a comprehensive, interconnected state of physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual wellbeing (Eby, 2023; Southcentral Foundation Nuka System of Care, n.d., 2019).

Upon assuming responsibility for primary care, SFC underwent a transformative process, gathering feedback from the Native community over the course of a year. The Nuka System of Care underwent a complete overhaul, focusing on two key elements: customer ownership and relationships (Transnational Forum on Integrated Community Care [TFICC], 2019). SCF avoids referring to the Alaska Native and American Indian individuals it serves as “patients” because the term is deemed passive and does not align with the high level of engagement SCF seeks. Instead, recognizing that those served are both customers and owners of the health care system, as well as their personal health journeys, they are termed “customer-owners” (Salinsky, 2017). SCF functions within the tribal authority of Cook Inlet Region, Inc., which appoints SCF’s seven-member board of directors. This board formulates policies and holds overarching control and management responsibilities for the organization. Notably, all members of SCF’s board of directors, the president/CEO, and over 60% of the management and leadership are customer-owners (TFICC, 2019).

SCF aims to involve the entire Native community in the health care system. On an individual level, SCF acknowledges that individuals have more control over their health outcomes than providers do. Building strong, long-term relationships with customer-owners is emphasized, fostering understanding of their health issues and establishing trust (TFICC, 2019). This approach enables providers to more effectively support customer-owners in achieving wellness.

Redesigning behavioral health services was instrumental to the success of the Nuka system; it provided customer-owners with improved access to services, including (Salinsky, 2017):

group learning circles, individual appointments with a psychiatrist or behavioral health clinician, collocated psychiatrists in primacy care, same day appointments with a master’s level clinician in outpatient behavioral health, the integration of behavioral health consultants into primary care, and improved workflows to ensure timely handoffs between primary care and specialty behavioral health service (p. 2).

This has been a successful redesign, with participants reporting a nearly 50% reduction in substance abuse, depression, and trauma symptoms and a 25% reduction in anxiety. Nearly two-thirds reported an increase in self-esteem, cultural connectedness, and spiritual wellbeing (Huhndorf, 2017).

SCF actively engages with the community through various initiatives. They organize the Annual Gathering, a free event offering insights into SCF services, live entertainment, and activities for children, along with the opportunity to purchase Alaska Native art. SCF maintains strong connections with community organizations, such as the Alaska Federation of Natives and the Alaska Native Health Board. In addition, the Health Education department collaborates to provide a range of services, including group classes, workshops, health fairs, counseling, cooking classes, and educational demonstrations, fostering community wellbeing and education (TFICC, 2019).

Access to and quality of care for customer-owners has resulted in dramatic improvements since services were transformed under the Nuka system, with SCF reporting the following changes from 2000 to 2017: a 26%, 47%, and 59% drop in deaths due to cancer, heart disease, and cerebrovascular disease, respectively; a 58% drop in infant mortality; a 40% drop in emergency room visits; a 36% drop in hospital admissions; 97% customer-owner satisfaction; and 95% employee satisfaction (Huhndorf, 2017; Routledge, 2020; Salinsky, 2017).

By embracing cultural traditions, emphasizing community engagement, and prioritizing patient-centered care, the Nuka system has transformed health care delivery for Alaska Native communities. SCF has diverse funding streams, with support from, but not limited to, the U.S. Indian Health Service, private insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, private and public grants, and other third-party payers (TFICC, 2019). Its innovative principles and components hold promise for promoting health equity and improving outcomes for populations across the country. Groups such as CareOregon, the Cherokee Nation, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, and Harvard Medical School’s Center for Primary Care are a handful of the organizations adopting Nuka’s integrated-care approach (Huhndorf, 2017). Funding of SFC and related initiatives is a key concern for scaling up and sustaining the model.

SCF’s Nuka System of Care is a primary example of the possibility and power of incorporating patients and communities into extended community-based care teams and co-creating and co-designing health care. Nevertheless, achieving this integration requires time, the establishment of mutual trust, structured recruitment processes, clarification of roles, and sensitivity to professional and institutional barriers. The model emphasizes prioritizing community input and co-design and shaping the health care system based on community preferences. Allowing customer-owners to take ownership of their health care, coupled with a willingness to implement bold and comprehensive changes, facilitates the creation of a high-quality, sustainable system tailored to community needs (Eby, 2023).

a The Anchorage Service Area measures approximately 107,413 square miles and extends east to the Canadian border, north to Cantwell, west to the upper Kuskokwim Valley, and southwest to the Aleutian Pribilof Islands. The Anchorage Service Area has the largest urban population in the state, and the most diverse rural population (Indian Health Service, n.d.b).

Children can be encouraged to actively participate in their own health care by voicing their needs and preferences, which can help tailor care to be more child centered (Carter et al., 2024). With proper preparation, older children and adolescents can advocate for their health needs and those of their peers, and promote awareness and education about health issues within their communities, as represented in Figure 3-5 (Lee et al., 2016). Families can act as coordinators of care, ensuring that all aspects of a child’s health, including medical, social, and educational needs, are addressed comprehensively (Cady & Belew, 2017; Family Voices, n.d.). They can also be involved in shared decision-making processes with health care providers, ensuring that care plans align with their values and preferences. Additionally, families can provide emotional and practical support to other families navigating the health care system, fostering a community of shared experiences and resources (Gage-Bouchard, 2017). Engagement of children, youth, families, and communities can better address their needs and lead to development of more effective programs.

Communities also play a vital role in health care transformation. Community members can be trained as health workers to provide culturally sensitive care, bridge gaps between health care providers and families, and address social determinants of health (Lloyd, Moses, & Davis, 2020; Schaaf et al., 2020). Communities can also mobilize to advocate for policy changes that support health equity, such as improved access to health care services and antiracist practices. Furthermore, communities can establish

SOURCES: Dann Warrick, age 22, United States; © Peace Child International, used with permission.

resource hubs that provide access to health-related information, services, and support, promoting a holistic approach to child health and wellbeing (Gilbert et al., 2023; Manis et al., 2022). Each of these models of engagement can be used to redistribute power, and they value multiple forms of knowledge and can facilitate increased trust and improved outcomes for children, youth, families, and communities.

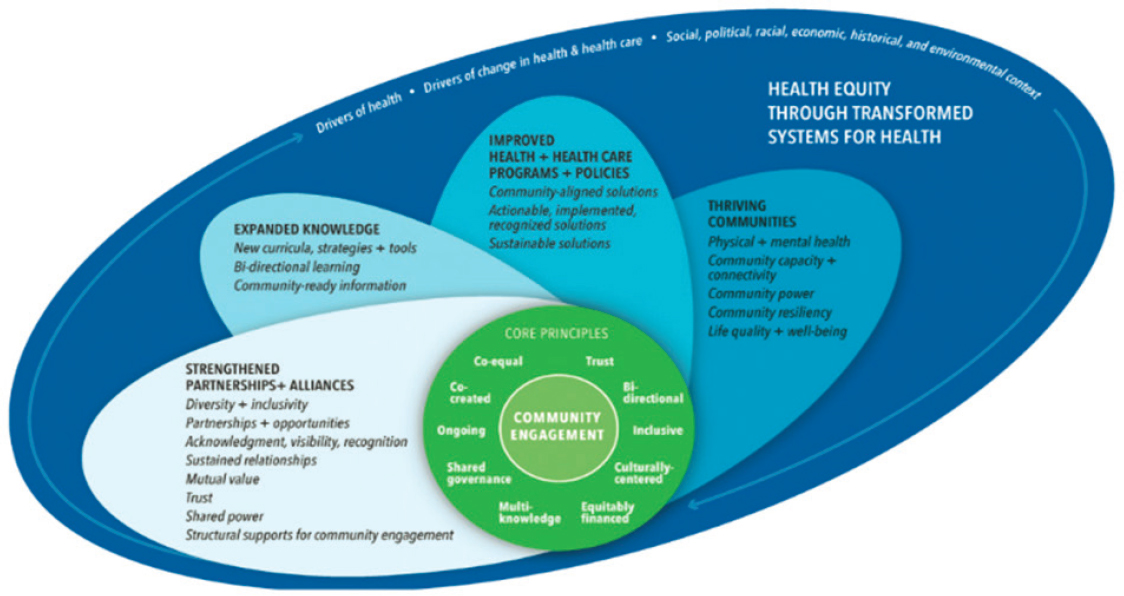

NAM developed a conceptual model to assess community engagement in the context of health equity and systems transformation, presented in Figure 3-6. This model identifies and defines core principles necessary to produce meaningful engagement, along with four outcome areas to evaluate community engagement efforts toward health equity (Aguilar-Gaxiola et al., 2022).

COMPREHENSIVE WORKFORCE TRAINING

Implementing comprehensive training programs is essential to ensure that the health care workforce is competent, diverse, team oriented, antiracist, and able to promote relational health. This includes efforts to increase diversity in the health care workforce, cultural humility training, and attention to compassionate care (Lloyd, Moses, & Davis, 2020). A well-trained and diverse workforce is better equipped to address the unique needs of children and families from various backgrounds. Research has shown that a diverse health care workforce can improve patient satisfaction, promote better communication between providers and patients, and reduce health disparities (Jongen, McCalman, & Bainbridge, 2018).

The concepts of cultural humility and health equity can be interwoven to all aspects of graduate medical, nursing, and allied health education. For example, case studies in which students learn about the experience of a particular disease or strategies for disease prevention can be designed to model culturally humble approaches in the provision of care and the avoidance of stereotypical thinking (Foronda et al., 2016; Mosher et al., 2017). Research suggests one effective approach to cultivating cultural humility is to accompany experiential learning opportunities or case studies with reflection that expands learning beyond skills and knowledge. This includes questioning current practices and proposing changes to improve the efficiency and quality of care, equality, and social justice (Barton, Brandt, et al., 2020; Barton, Murray, & Spurlock Jr., 2020; Foronda, Liu, & Bauman, 2013). In the case of nursing education, programs designed to develop nurses’ cultural sensitivity and humility, as well as cultural immersion programs, have been developed, and research suggests that such programs can effectively develop skills that strengthen nurses’ confidence in treating diverse populations, improve patient and provider relationships, and increase nurses’ compassion (Allen, 2010; Gallagher & Polanin, 2015; National Academies, 2021e, p. 207; Sanner et al., 2010).

A burgeoning body of research points to the importance of empathy, compassionate care, and empathic engagement in patient care leading to better patient outcomes and improving the patient experience. Empathy involves

“understanding (rather than feeling) of a patient’s concerns, experiences, pain, and suffering combined with a capacity to communicate this understanding and an intention to help” (Hojat, 2007, para. 3). Compassionate care serves as the vehicle for care providers to express empathy toward patients and families, and supports a person-centered and relationship-based care model (Arnold P. Gold Foundation, 2014). Empathic engagement brings together empathy and compassionate care to fully recognize, acknowledge, and validate a larger understanding and appreciation of the experience patients and families (Guidi & Traversa, 2021). Emerging research also demonstrates how compassionate patient care can improve health outcomes and reduce workplace stress and burnout for health care professionals (Cochrane et al., 2019).

Recognize Activities Related to Patient and Family Experience

Accrediting bodies have begun recognizing activities related to assessing and improving patient and family experience. This recognition can drive improvements in care quality and patient satisfaction, ultimately leading to better health outcomes for children (Halfon, DuPlessis, & Inkelas, 2007). Patient and family education has been identified as a critical element in delivering quality health care services, emphasizing its importance in improving overall outcomes for consumers (Bhattad & Pacifico, 2022; Bombard et al., 2018; Patel, 2020). By incorporating patient and family experience metrics into accreditation standards, these bodies encourage health care organizations to focus on patient-centered care and family engagement.

Providing Support and Care through Youth-Led Services

Youth-led services encompass a variety of initiatives where young people take the lead in addressing issues pertinent to their communities, and typically include mental health initiatives, health promotion and education, community service and development, and participatory research (Ozer et al., 2020; Talbert, 2017; YouthPower Learning & YouthPower Action, n.d.). Youth-led mental health initiatives may involve creating safe spaces, reducing stigma through campaigns, and providing peer-support programs (Hogan et al., 2003; Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario, n.d.; World Health Organization, 2023). Health promotion efforts may include, for example, sexual and reproductive health education campaigns or health fairs organized by youth (AmeriCorps, 2024; Yun & Yun, 2023; YouthPower Learning & YouthPower Action, n.d.). Community service initiatives often involve volunteer programs and youth advisory councils that influence local policies (YouthPower Learning & YouthPower Action, n.d.). Participatory research, such as Youth Participatory Action Research, trains youth to conduct research on issues affecting their lives, leading to actionable insights and policy changes (Annie E. Casey Foundation, n.d.;

Ballonoff Suleiman et al., 2019; CDC, n.d.b; Morrel-Samuels et al., 2017; Ozer et al., 2020; Soleimanpour et al., 2008; Youth.gov, n.d.).

Youth-led services are intended to address significant gaps in traditional service delivery models by leveraging the unique perspectives and energy of young people (Talbert, 2017; YouthPower Learning & YouthPower Action, n.d.). Many current efforts are designed to address the growing mental health crisis among youth, which is exacerbated by factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic, racial injustices, and climate change (Bell et al., 2023; National Academies, 2022b; see also Chapter 2). Research shows that peer-to-peer support programs are associated with several positive benefits, including increased self-esteem and confidence, a heightened sense of control in bringing about life changes, and feelings of greater hope and inspiration (California Children’s Trust, 2022; Mental Health America, 2018). These positive outcomes are shown to help decrease substance use and depression as well as psychotic symptoms, and reduce hospital admission rates (California Children’s Trust, 2022; Mental Health America, 2018).

These services often struggle with sustainability and scalability due to limited funding and resources. Youth-led services require structured support, mentorship, and adequate funding to achieve their full potential and make a lasting impact (AmeriCorps, 2024; Learning to Give, n.d.). Several strategies have been suggested to scale and sustain youth-led services:

- Integrating youth participatory approaches into health equity initiatives (Ozer et al., 2020);

- Developing a developmental framework for youth-led programs (Ballonoff Suleiman et al., 2019);

- Establishing formal certification and training programs for youth peer-support specialists (California Mental Health Services Authority, n.d.);

- Fostering partnerships with established mental health organizations (American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, n.d.); and

- Implementing rigorous evaluation and research to demonstrate effectiveness (Ballonoff Suleiman et al., 2019; Ozer et al., 2020).

Initiatives such as AmeriCorps’s (2024) Healthy Futures provide critical opportunities to expand the workforce of youth leaders and provide consistency in the delivery of youth-led services (see also Talbert, 2017; Wong, Zimmerman, & Parker, 2010). Healthy Futures encompasses multiple projects and initiatives, often partnering with local health organizations, community centers, schools, and other institutions to maximize their impact (AmeriCorps, 2024). Healthy Futures programs have produced favorable outcomes, such as improved food security, increased utilization of health care, improved mental health, and reduced child maltreatment

(AmeriCorps, 2019, 2024). Moreover, these initiatives play a role in sustaining the development of the future health care workforce (Schultz Family Foundation, 2024; Soleimanpour et al., 2008).

Leveraging Anchor Institutions

Since the 1960s, discussions have been ongoing about the role of local community organizations and their abilities to address social determinants of health in cities and localities across the United States (Koh et al., 2020). Community organizations that impact education, health care, and infrastructure, along with public institutions such as local government entities, faith-based groups, and cultural establishments, were first identified as “anchor institutions” in 2001 (Fulbright-Anderson, Auspos, & Anderson, 2001; Harkavy et al., 2014) and described thereafter as “[a] new paradigm for understanding the role that place-based institutions could play in building successful communities and local economies” (Taylor & Luter, 2013, p. 4).

While there is no singular definition of anchor institutions, Taylor and Luter (2013) have identified the following common features: “anchors are large, spatially immobile, mostly nonprofit organizations that play an integral role in the local economy” (p. 8). For-profit hospitals, which are more likely to operate in vulnerable communities, also have the potential to serve as anchor institutions (Cronin et al., 2021; Franz et al., 2021). Because these groups are deeply embedded in their communities (Norris & Howard, 2015, p. 8), they have been described as “sticky capital,” a designation implying a vested economic self-interest in actively contributing to the wellbeing and prosperity of the communities where they operate, ensuring safety, vibrancy, and health (Serang, Thompson, & Howard, 2013, p. 4). The mission of anchor institutions has been identified as “a commitment to consciously apply their long-term, place-based economic power of the institution, in combination with its human and intellectual resources, to better the long-term welfare of the communities in which the institution is anchored” (Serang, Thompson, & Howard, 2013, p. 5). Hospitals dedicate significant financial, human, and intellectual assets to tackle societal issues, recognizing the interconnectedness of their future with the community beyond their confines. In 2017, hospitals allocated over $1.1 trillion annually (Koh et al., 2020) and constituted between 7.5% and 10.4% of the U.S. labor force, depending on the region, in 2016 (Koh et al., 2020; Statista, n.d.).

Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity discusses at length the significant impact of anchor institutions on their surrounding communities (National Academies, 2017a):