Launching Lifelong Health by Improving Health Care for Children, Youth, and Families (2024)

Chapter: 4 Children in the United States: Demographics, Health, and Wellbeing

4

Children in the United States: Demographics, Health, and Wellbeing

We need a focus on prevention with so many children already experiencing needs for tier 2 and 3 [mental health] intervention.

—Comment to Committee from Educator, Palmyra, Pennsylvania

This chapter builds on the science frameworks explored in Chapter 2 and the evidence that social, environmental, and relational factors influence trajectories in health, wellbeing, and development. Here the committee provides an overview of the health of children and youth in the United States and their demographics, along with the declining birth rate. As shown in recent reports by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (National Academies), the chapter describes higher rates of poverty among U.S. children than those of most other industrialized nations. The current state of child and adolescent health and wellbeing is discussed at length, as are significant family and community factors that influence child health. The committee reports that U.S. children are not doing well—they face major health problems with lasting impact on their overall growth and development and preparation for adult life.

CHILDREN AND YOUTH IN THE UNITED STATES

In 2022, there were 72.5 million children under age 18 years in the United States, accounting for nearly 22% of the total U.S. population (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics [FCFS], 2022b;

Kids Count Data Center, 2023b). While the number of children in the United States increased by nearly 2% from 2000 to 2015, the rest of the population grew 9 times faster during that same time (Myers, 2017). The child population has since decreased, from 74.2 million in 2010, to 73.1 million in 2020, to 72.5 million in 2022. This decrease in the child population reflects the decline in U.S. births, with an estimated 3.6 million births documented in 2020, compared with 4.0 million in 2010, resulting in fewer children under age 5 than in 2010 or 2000 (Census Bureau, 2023a).1

The Pew Research Center notes that three key demographic forces have reshaped the overall U.S. population recently: growing racial and ethnic diversity, increasing immigration, and rising percentage of older adults (Parker et al., 2018). However, these changes are uneven across the country, with a faster rate of change in urban counties than in suburban areas and smaller cities. Rates in rural counties have lagged the most, with half of rural counties having fewer residents in 2018 than they did in 2000. The number of children living in the 100 largest cities has decreased from 14.2 million in 2010 to 13.9 million in 2020 (a drop of 2.2%), consistent with the decrease in the number of children nationwide during this period (O’Hare & Mayol-Garcia, 2023). Immigration may also influence this reduction of children in urban areas, with settling of immigrants to rural counties steadily increasing over the past 10 years. Of note, the majority of rural counties had fewer U.S.-born residents in 2018 than they did in 2000 (Parker et al., 2018). Nonetheless, immigrants are still more concentrated in cities and suburbs than in rural areas.

Immigration

The overall U.S. population has grown more diverse in recent decades, with especially high rates of diversity among U.S. children. Analysis of child population Census data by the Annie E. Casey Foundation shows that the percentage of children of color has doubled in recent decades, from 26% in 1980 to 53% in 2020 (O’Hare, 2001; O’Hare & Mayol-Garcia, 2023).2 In 2023, non-Hispanic White children still accounted for the largest racial

___________________

1 Limitation of Census data in 2020: In the 2020 Census, there was a net undercount of 2.1% of all children (birth to age 17 years). Young children (birth to age 4 years) had a higher net undercount—5.4%—than any other age group. Preliminary analysis suggests young Black and Hispanic children were missed at a higher rate than non-Hispanic White children (Census Bureau, 2023a).

2 To assess demographic change, O’Hare and Mayol-Garcia compare data from the 2020 and 2010 censuses with previous Annie E. Casey Foundation analysis of data on the child population from the 2000 Census (O’Hare, 2001; O’Hare & Mayol-Garcia, 2023, Table 3).

and ethnic group, at 49% (FCFS, 2023a).3 Hispanic or Latino children represented 26% of children, Black children made up 14%, Asian children 6%, American Indian and Alaska Native 1%, and Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander less than 0.5% (FCFS, 2023a).

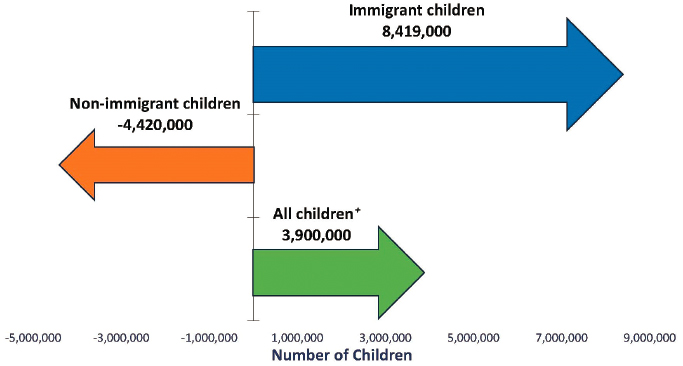

Regarding their households, in 2019, over a quarter (26.3%) of American children lived with a foreign-born parent (Anderson, Hemez, & Kreider, 2022),4 and 21% spoke a language other than English at home (FCFS, 2023a). In 2022, an estimated 25% of children lived in immigrant families, either born outside of the United States themselves or living with at least one parent born outside of the United States (KFF, 2023b; Kids Count Data Center, 2023c).5 In the past 30 years, the growth in the number of immigrant children offsets the decline in the number of nonimmigrant children (see Figure 4-1).

As of 2018, approximately 4 million children who are U.S. citizens lived with at least one undocumented parent; about 6 million in total lived with at least one undocumented family member (American Immigration Council, 2021). Between 2010 and 2021, the number of children with immigrant parents grew by 6%, a significantly slower rate of growth than from 2000 to 2010, when the number grew by 30% (Ward & Batalova, 2023).6 Almost all children in immigrant families were born in the United States (88% in 2021), yet they are less likely to access health care (Brooks et al., 2020; Keisler-Starkey & Bunch, 2022; Keisler-Starkey, Bunch, & U.S. Census Bureau, 2020) and other health-related services (Haley et al., 2020) than are children with native-born parents.7

___________________

3 FCFS (2023a) evaluates many sources of data when developing its yearly report on key national indicators of wellbeing. Sources used in this report, such as data from the U.S. Census Bureau, have implemented the standards for reporting race and ethnicity statistics issued in 1997 by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget.

4 To explore the living arrangements of children by selected characteristics, Anderson, Hemez, and Kreider (2022) used data from the 2008 and 2018 American Community Survey (ACS), 2007 and 2019 Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement, and 2014 Survey of Income and Program Participation.

5 The Kids Count Data Center at the Annie E. Casey Foundation relied on analysis by the Population Reference Bureau of data from the U.S. Census Bureau, Census Supplementary Survey, and ACS. KFF analysis was performed on a 2022 ACS 1-year Public Use Microdata Sample.

6 Ward and Batalova (2023) drew on statistics from the Migration Policy Institute, U.S. Census Bureau (using data from the 2021 ACS, 2022 Current Population Survey, and 2000 decennial Census), and the U.S. departments of Homeland Security and State.

7 More than one in four immigrant children did not have health coverage in 2019 (25.5%, compared with 5.1% of native-born citizen children; Keisler-Starkey, Bunch, & U.S. Census Bureau, 2020). As of January 2020, 35 states and the District of Columbia provided health coverage to lawfully residing immigrant children without a 5-year wait (Brooks et al., 2020), and as of July 2019, six states and the District of Columbia use state-only funds to provide Medicaid coverage to income-eligible children regardless of immigration status (Artiga & Diaz, 2019).

NOTE: Children who are foreign born or reside with at least one foreign-born parent are considered immigrant children. Foreign-born children with native-born parents are considered nonimmigrant children. “All children” includes ~100,000 children without an immigrant status (i.e., children living in households with no parents present).

SOURCE: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2024, with data from U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement, and Current Population Reports.

Children migrating with their parents are at higher risk for adverse childhood experiences, chronic health conditions, trauma and exposure to violence, and development of mental health disorders (Alegría et al., 2023; Chang & Slopen, 2023; Claypool & Moore de Peralta, 2021; Linton et al., 2020). Refugee or unaccompanied children have increased levels of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Frounfelker et al., 2020; Linton et al., 2020). Immigrant families may not have access to services; or, given their cultural views or worries about the cultural congruency of available services, they may not seek treatment because of shame and stigma related to mental health problems (Fendian, 2021; Mohammadifirouzeh et al., 2023). Integrating culturally sensitive mental health services into health care and schools allows for reduction in stigma and ease of access (Phelan et al., 2023).

According to estimates by the Migration Policy Institute and Urban Institute, at least 40% of children of immigrants had parents with limited English proficiency, which can pose challenges for parents in obtaining good jobs, finding and enrolling in public programs, navigating their

children’s education systems, and communicating with schools (Batalova, 2024; Lou & Lei, 2019). Children of parents who have low English proficiency are at increased risk of receiving suboptimal quality of care and worse health care access, including care for children with special health care needs (Blumberg et al., 2010; Dougherty et al., 2020; DuBard & Gizlice, 2008; Linton et al., 2020). Utilizing trained medical interpreter services appropriately alongside health care providers can improve care for this population (Linton et al., 2020). Additionally, depending on the legal status of the family, families may fear deportation or legal action when trying to seek services (Raphael et al., 2020; Rodriguez & McGrath, 2021). During the COVID-19 pandemic, immigrant families described hesitation in applying for benefits programs out of fear of deportation (Rodriguez & McGrath, 2021).

Poverty

Income level can have a significant impact on the health and wellbeing of children, as it impacts the capacity of their families to meet basic needs and can introduce high levels of family stress that impact important relationships and social interactions in a child’s life. Family income influences where a child lives, what they eat, and what child care settings and schools they are able to attend. Living in poverty leaves children vulnerable to environmental, health, educational, and safety risks.

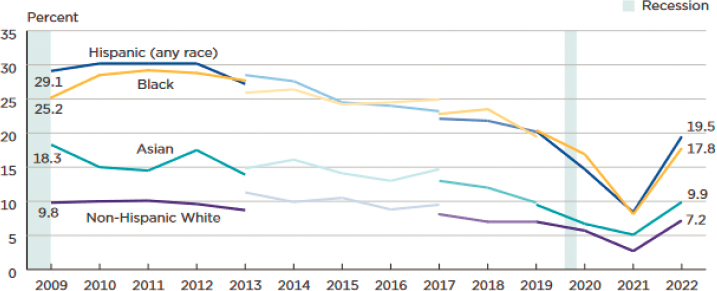

As noted, children in the United States experience high rates of poverty, substantially higher than in almost all other industrialized countries (National Academies, 2019a, 2023g). According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the United States is ranked 6th worst out of 41 countries for childhood poverty outcomes (Ingraham, 2014). Among children living in poverty in the United States, approximately three-quarters are children of color; two-thirds live in working families; and many live in single-parent households, primarily with their mothers (Haider, 2021; Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 2022a,b). More than 2 million children live in “deep poverty” (having family income below one-half of the poverty line; National Academies, 2019a). The highest rate of poverty of any age group is children under age 5 (Children’s Defense Fund, 2023). Children in the South experience higher poverty rates than in other regions of the country. In 2022, Hispanic children were the largest group of children living in poverty, followed by Black, Asian, and White children (see Figure 4-2; Shrider & Creamer, 2023). Poverty rates among immigrant children, especially Hispanic children, are the highest, with child poverty rates twice as high as among immigrant families as among nonimmigrant families (Acevedo-Garcia et al., 2021). The U.S. Department of Education

NOTE: Population as of March of the following year. The supplemental poverty measure estimates for 2019 and beyond reflect the implementation of revised methodology. The data for 2017 and beyond reflect the implementation of an updated processing system. The data for 2013 and beyond reflect the implementation of the redesigned income questions. The data points are placed at the midpoints of the respective years.

SOURCE: Shrider & Creamer, 2023; based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, 2010–2023 Annual Social and Economic Supplements.

indicated a median estimated poverty rate of nearly 14% for children ages 5–17 in U.S. school districts in 2022 (Lui, 2023). This average hides the massive variation across districts, with the poverty rate ranging from just 3.1% in some districts to as high as 42.4% in others.

In 2021, child poverty levels fell dramatically—by nearly half—with the help of pandemic-era government programs and cash assistance not typically seen in other years. However, the end of these pandemic-era social safety net programs led to a doubling of the supplemental poverty measure rate for children from 2021 (5.2%) to 2022 (12.4%), returning to prepandemic levels and affecting about 9 million children (Shrider & Creamer, 2023).

Food security intersects with economic status—children living in households with annual incomes below the official poverty line have higher rates of food insecurity, with rates varying between rural and urban areas (Carson & Boege, 2020; Economic Research Service, 2023a; Marshall et al., 2022). In 2022, approximately 7.3 million children lived in food-insecure households, and the number of food-insecure households with children (insecure at least some point during the year) increased from approximately 6% in 2021 to almost 9% in 2022 (Rabbitt et al., 2023a,b). A growing

body of evidence associates the negative consequences of food insecurity with children’s health and developmental outcomes (Wight et al., 2014). For example, children in households experiencing food insecurity have rates of lifetime asthma diagnosis and depressive symptoms that were 19.1% and 27.9% higher, respectively, compared with their food-secure counterparts (Thomas, Miller, & Morrissey, 2019).

Housing also affects children’s health outcomes. Housing that is inadequate, crowded, or too costly can pose serious problems for children’s physical, psychological, and social wellbeing (Breysse et al., 2004; Frederick et al., 2014; Krieger & Higgins, 2002; Kushel et al., 2006). In 2021, 39% of U.S. households with children had one or more of three housing problems: physically inadequate housing, crowded housing, or housing cost burden greater than 30% of household income (FCFS, 2023b). During 2022, an estimated 97,800 children were homeless at a single point in time, and 10% of these children were unsheltered (FCFS, 2023b).

Historically marginalized people and their families are disproportionately impacted by homelessness. Black and Hispanic youth face greater risks, spending more time homeless than their White counterparts (Gonzalez et al., 2021). Among youth aged 13–25, American Indian and Alaska Native, Black, and Hispanic youth experience higher rates of homelessness (11%, 7%, and 7%, respectively) than White, non-Hispanic youth (4%; Gonzalez et al., 2021). The intersection of marginalized identities exacerbates these inequities, with LGBTQ+-identifying Black youth facing especially high rates of homelessness.

An Aging Population and Life Expectancy

Two major demographic changes document the importance of strengthening the health and wellbeing of America’s children and youth: (1) major shifts in the population pyramid, with increasing longevity among older Americans and a declining birth rate and (2) major increases in chronic disease, disability, and early mortality among working-age U.S. adults. Numerous reports document the aging of the global population in recent years and in the United States, but few reference how rising lifespans of older populations relate to the decrease in birth rates and what changes in the population pyramid will mean for the country in the coming decades (National Academies, 2022a). In 1970, the population aged 65 and over was 9.8%, growing to 13% in 2010 and to 16.8%, or 55.8 million people, in 2020 (Caplan, 2023; Ortman, Velkoff, & Hogan, 2014). Conversely, the population of children has experienced a notable decline during the same time frame. In 1970, children under age 18 represented 36% of the total population, falling to 25% in 2010 and 22.1% in 2020 (Census Bureau,

1996, 2023a). This trend is expected to continue, presenting both social and economic challenges for policy makers and service providers (Caplan, 2023; Mather & Scommegna, 2024; Ortman, Velkoff, & Hogan, 2014; Urban Institute, 2024; Vespa, Medina, & Armstrong, 2020).

Beyond the dramatic increase in the ratio of older adults to children in the United States, the country has also experienced a marked decline in the fertility rate (Buckles, Guldi, & Schmidt, 2019). Since 2007, the number of U.S. births has declined and the fertility rate has dipped well below the “replacement rate” at which the number of births equals the number of deaths (Kearney & Levine, 2023). The end result of such a long-term trend will be an increasingly aging population and a declining economy as fewer workers care for more and more disabled citizens, a situation already evident in countries such as Japan and now China (Cheng et al., 2022).

Policies for supporting families with children, such as enhanced child leave, tax incentives, and increased educational support, have not coincided with a higher fertility rate in other countries even though they may be associated with improved outcomes for the children that are born (Malak, Rahman, & Yip, 2019). This points to other factors contributing to decreased birth rates, including shifts in social norms and attitudes. In the United States, immigration has maintained population numbers in spite of the declining fertility rates, although current political threats to immigration may limit its influence on numbers of workers and productivity (Pew Research Center, 2015).

The relative shortage of children and greater proportion of older adults in the United States will lead to an unbalanced level of workers and taxpayers supporting retired older adults (see The New Importance of Children in America; Myers, 2017). This imbalance will be felt unevenly, as urban areas have seen a sharp growth in the prime-age working population in recent years, while 88% of rural counties have lost prime-age workers since 2000 (Parker et al., 2018).

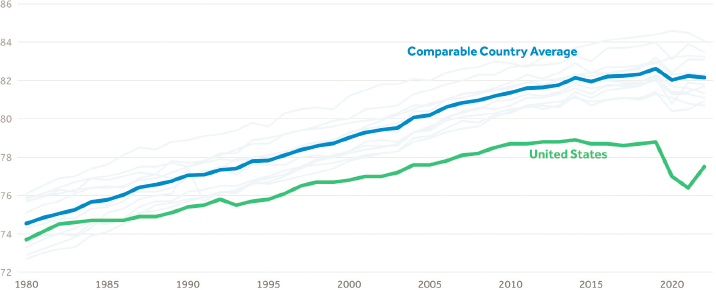

Trends in U.S. life expectancy also raise concerns and opportunities for the nation. Since 2010, U.S. life expectancy has been decreasing, in stark contrast with other industrialized countries (see Figure 4-3).

Despite increased longevity among older adult populations, U.S. life expectancy experienced notable declines, even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (Arias et al., 2023; Bastian et al., 2020; Woolf & Schoomaker, 2019). This decline has been driven by increasing mortality rates among younger populations (Woolf & Schoomaker, 2019; Woolf, Wolf, & Rivara, 2023). This change reflects increases in successful suicide, drug overdoses, and gun violence. These in turn reflect growing rates of anxiety and depression in children and youth, which continue into young adulthood, leading to “deaths of despair” among young and middle-aged adults (Case & Deaton,

NOTE: Comparable countries include Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. See Methods section of “How Does U.S. Life Expectancy Compare to Other Countries?” (Rakshit, McGough, & Amin, 2024).

SOURCE: Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker, 2022.

2022; see also Brignone et al., 2020). In addition, large increases in chronic conditions, especially obesity (Olshansky et al., 2005), pulmonary disease, and cardiovascular disease, have also made major contributions to increasing mortality. Most of these conditions have onset in childhood and adolescence, when opportunities to prevent them could result in major gains in U.S. life expectancy.

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the decline in life expectancy, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimating a drop of 0.1 to 6.6 years due to COVID-19 (Andrasfay & Goldman, 2021; Arias & Tejada-Vera, 2023; Shmerling, 2022). Life expectancy from COVID-19 dropped more among American Indian/Alaska Native, Hispanic, and African American groups, which experienced higher rates of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death than other groups (Andrasfay & Goldman, 2021; Arias & Tejada-Vera, 2023). Of note, however, life expectancy has recently begun to rise again (see Figure 4-3).

CURRENT STATE OF CHILD AND ADOLESCENT HEALTH

Chapter 1 noted that a growing proportion of children have chronic physical, mental, and social conditions and that this growth, particularly around mental and behavioral health, reflects early life experiences and community and environmental exposures. This section takes a closer look at the current state of the health and wellbeing of America’s nearly

73 million children and youth, examining adverse experiences, health risks, and protective factors, chronic health conditions, and key causes of mortality.

The United States lags well behind other wealthy Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries on numerous indicators of child wellbeing (OECD, 2020, 2022). This analysis ranks the United States near the bottom of dozens of wealthy nations for infant mortality, low-weight births, childhood poverty, and several education and school success indicators. The United States ranked 36th out of 38 countries evaluated in the 2020 UNICEF report Worlds of Influence: Understanding What Shapes Child Well-Being in Rich Countries, which focused on children’s mental wellbeing, physical health, and academic and social skills (Gromada et al., 2020). The United States ranks lowest among OECD countries for child physical health, including rates of childhood obesity (Fryar, Carroll, & Afful, 2020; Gromada et al., 2020). Additionally, the OECD 2022 Child Well-Being Dashboard ranks the United States well below average on life satisfaction among children, with only 31% of 15-year-old youth reporting high satisfaction with their life as a whole (OECD, 2022).

Consideration of the health status of children and youth must review not only the presence or absence of physical, developmental, and mental health conditions, but also their progress toward flourishing and wellbeing. Compared with ratings of children’s overall health status, parents/caregivers tend to rank their children lower on important indicators of flourishing that impact quality of life (Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative [CAHMI], 2024). Flourishing for children ages 6 months to 17 years has been assessed in the National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) by asking parents whether children show interest and curiosity in learning new things, are able to regulate emotions and behaviors when faced with a challenge, and can focus and persist to complete tasks (Bethell et al., 2019a). Studies using these measures of child flourishing find positive associations with school engagement, health behaviors, wellbeing, and life expectancy. They also note variations in flourishing among children with similar risks (e.g., poverty, disability, adverse childhood experiences) that link to measures of positive family relationship factors. (Bethell, Gombojav, & Whitaker, 2019; Kandasamy et al., 2018). Based on recent findings from the NSCH, only 21.5% of caregivers both report that their child’s overall health status is excellent or very good and that their child is also consistently flourishing (CAHMI, 2024).

As delineated in Chapter 2, whole child and family health and wellbeing emerges through a complex and dynamic development process that integrates a range of biological, interpersonal, social, environmental, and

behavioral influences. These factors can shape and modify brain development, gene expression, and physiologic, mental, emotional, social, and behavioral functioning. Several social and environmental influences can optimize health and wellbeing, including: (1) positive childhood experiences, whereby children and youth have a sense of being physically and emotionally safe, nurtured, and loved and that they belong at home, school, and in the community; (2) environments that support children’s emotional and cognitive engagement, curiosity and interest in learning, and activities for positive social interaction; (3) experiences that develop children’s skills for building and maintaining positive relationships and the capacity to sustain a sense of meaning and hope for the future; and (4) environments free from discrimination (La Charite et al., 2023; Sege & Harper Browne, 2017; Wallerich et al., 2023). Such enduring influences and childhood experiences promote wellbeing and can buffer the impact of adverse childhood experiences and other health risks.

Adverse Childhood Experiences

Adverse childhood experiences refer to potentially traumatic events that occur before age 18 years, including, among other forms, physical, emotional, or sexual abuse; neglect; and household dysfunction (CDC, 2019d). These experiences have been shown to have profound and long-lasting impacts on an individual’s physical and mental health, as well as their overall wellbeing. Adverse childhood experiences are common across all communities and socioeconomic groups in the United States but are more prevalent among historically marginalized populations (Camacho & Clark Henderson, 2022; Mersky et al., 2021; Sacks & Murphey, 2018).

CDC (2019d) estimates one in six adults have experienced four or more types of adverse childhood experiences, and research has now established numerous linkages between these experiences in childhood and lifelong health risks. Preventing adverse childhood experiences can help children and adults to thrive, reducing health conditions, risky behaviors, and socioeconomic challenges.

The consequences of adverse childhood experiences are far-reaching and can manifest in various ways throughout an individual’s life. Children who experience adversity are more likely to struggle with academic performance, behavioral issues, and mental health problems such as depression and anxiety (CDC, 2019d). As adults, those with a history of adverse childhood experiences are at increased risk for chronic health conditions such as heart disease, cancer, and substance abuse disorders, as well as shorter life expectancy and decreased life opportunities (e.g., educational achievement

and job potential; Brown et al., 2009; Dube et al., 2003; Elmore & Crouch, 2020; Grummitt et al., 2021; Iverson, Cook, & Iverson, 2024; Walker et al., 2022). Recognizing the impact of adverse childhood experiences, and implementing strategies for preventing and mitigating their effects, has become a public health priority, with efforts focused on promoting resilience and trauma-informed care and addressing the social determinants of health (Jones, Merrick, & Houry, 2020a).

Chronic Conditions and Disabilities

A large and increasing number of U.S. children have some chronic health condition, and many require substantial care by families and the health care system. Rates of chronic conditions have risen dramatically over the past half century, partly because of improved survival rates for more complex conditions that previously would have led to early death (e.g., spina bifida, cystic fibrosis, leukemia, sickle cell disease; Payot & Barrington, 2011). However, a larger contributor has been more common conditions that are not associated with early death—especially asthma, obesity, mental health conditions (especially anxiety, depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [ADHD], and substance use), and neurodevelopmental conditions (especially autism spectrum disorders, cerebral palsy; Jo et al., 2019; Perrin, Anderson, & van Cleave, 2014). Most of these conditions continue into adulthood and help account for growing chronic conditions among working-age adults (Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2007b).

Children who experience diverse conditions can be understood in overlapping categories: The first includes children with complex conditions involving multiple organ systems (e.g., mobility, lungs, feeding) and requiring multiple supports, including technological and equipment support. About 1% of U.S. children are in this category, although their care accounts for much higher expenditures than most other children (estimates range $50–$110 billion annually; Bergman et al., 2020; Berry et al., 2014; Cohen et al., 2011, 2018; Kuo et al., 2011; Murphy et al., 2020). The second category includes children with relatively low-prevalence but usually high-severity conditions (e.g., spina bifida, leukemia, arthritis, sickle cell anemia, cystic fibrosis; Perrin, Anderson, & van Cleave, 2014). These children, who represent at least 2% of the U.S. population, require ongoing support and access to specialized therapies and devices that may not be widely accessible in a child’s community or even state. The third category, about 10 times larger than the first two, includes high-prevalence conditions such as asthma, obesity, mental health conditions, and neurodevelopmental conditions (Maenner et al., 2023; Perrin, Anderson, & van Cleave, 2014). These are discussed in more detail below. The last category includes children in apparent good health, without any chronic

conditions, although they may face adversity in childhood as discussed above, putting them at risk for later chronic conditions.

Table 4-1 provides a comparative snapshot of national and state data on prevalence of chronic health conditions, special health care needs, and functional difficulties, using data from the 2021 and 2022 NSCH. The U.S. Census Bureau (2024) conducts the NSCH annually for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’s (HHS’s) Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Maternal and Child Health Bureau. All NSCH data collected are self-reported by parents or caregivers.

These data indicate that about 20% of children under age 18 years have a special health care need (HRSA, n.d.e). Over one in four households with children, 28.6%, has at least one child or youth with special health care needs (HRSA, n.d.e). These children are more likely to live in low-income neighborhoods and rely more on public health insurance; over half also have a co-occurring behavioral or mental health diagnosis such as ADHD or anxiety (Kids Count Data Center, 2023a). Among low-income children with special health care needs, about 85% of children do not receive needed health care, mainly because of cost and lack of access (Houtrow et al., 2020; Kids Count Data Center, 2023a).

Special Needs, Medical Complexity, and Functional Disability

Various agencies and clinical groups use different terms to describe chronic conditions among children, such as “disability,” “special health care need,” “functional limitation,” “complex medical condition,” and others. These terms describe overlapping groups, and in turn various strategies exist for identifying children and youth with these conditions. Some strategies use lists of specific conditions (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ], 2022b; Berry et al., 2015; Goodman et al., 2013; Simon et al., 2018). Others use a series of screening questions based on characteristics of chronic conditions, arising from the body of evidence regarding common needs or impacts across various conditions (McPherson et al., 1998; Stein et al., 1987; World Health Organization [WHO], 2013). In most cases, these approaches have been validated through studies of chronic physical conditions, with varied evidence of their ability to identify young people with chronic mental and behavioral conditions.

The definition of “children with special health care needs” emerged in 1998 to assist leaders in health policy, payment, and state programs in planning service delivery for this patient population (Kuhlthau et al., 2022). Children with special health care needs were defined as those “who have or are at increased risk for a chronic physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional condition and who also require health and related services of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally” (McPherson

| Chronic Health Condition, Special Health Care Need, and Functional Difficulty Indicators | National Prevalence, % (Across State Prevalence Range) | Children with Any Public Health Insurance, % | Children with Private Health Insurance, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Children with one or more of 24 chronic or lifelong health conditionsa | 38.8 (30.6–45.9) |

42.9 | 37.7 |

| Children diagnosed with one or more physical or genetic health conditionsb | 28.9 (23.1–34.6) |

31.7 | 28.1 |

| Children diagnosed with one or more mental, emotional, and/or behavioral health conditions | 18.4 (12.4–27.6) |

22.9 | 16.6 |

| Children diagnosed with one or more developmental health conditions | 12.5 (9.4–15.8) |

17.4 | 10.2 |

| Children with any chronic condition who also require an above-routine type/amount of health care services | 20.0 (13.9–25.3) |

25.9 | 17.5 |

| Children born premature and/or with a low birth weight (less than 2,500 grams at birth) | 15.3 (11.1–21.1) |

17.6 | 13.7 |

| Children with obesity (body mass index–for–age equal to or greater than the 95th percentile), ages 6–17 years | 18.1 (11.6–26.1) |

26.2 | 13.2 |

| Children experiencing one or more of 12 functional difficultiesc | 23.9 (16.7–30.7) |

32.0 | 19.3 |

a The 24 conditions asked about in the National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) include (1) physical or genetic health conditions: allergies (food, drug, insect, or other), arthritis/autoimmune disease, asthma, blood disorders (e.g., sickle cell disease, thalassemia, hemophilia), cerebral palsy, cystic fibrosis, diabetes, Down syndrome, epilepsy or seizure disorder, genetic or inherited condition, heart condition, frequent or severe headaches including migraine (3–17 years), hearing problems, and vision problems; (2) mental, emotional, and/or behavioral conditions: anxiety problems (3–17 years), depression (3–17 years), autism or autism spectrum disorder (3–17 years), attention deficit disorder or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (3–17 years); (3) developmental health conditions: Tourette syndrome (3–17 years), behavioral or conduct problem (3–17 years), developmental delay (3–17 years), intellectual disability (3–17 years), speech or other language disorder (3–17 years), or learning disability (also known as mental retardation; 3–17 years).

b Children with any chronic condition and need and/or use of an above-routine type or amount of health care services (national definition of “children and youth with special health care needs”) is assessed using the validated Children with Special Health Care Needs screener.

c The 12 functional difficulties asked about in the NSCH include (1) physical limitations: frequent or chronic difficulty with breathing or other respiratory problems; eating or swallowing; digesting food (including stomach/intestinal problems, constipation, or diarrhea); repeated or chronic physical pain (including headaches or other back or body pain); deafness or problems with hearing; blindness or problems with seeing, even when wearing glasses; (2) activity limitations: using their hands (0–5 years); coordination and moving around (0–5 years); serious difficulty walking or climbing stairs (6–17 years); difficulty dressing or bathing (6–17 years); difficulty doing errands alone, such as visiting a doctor’s office or shopping (12–17 years); (3) socioemotional difficulties: serious difficulty concentrating, remembering, or making decisions (6–17 years).

NOTES: “Public insurance” is defined as Medicaid, Medical Assistance, or any kind of government assistance plan for those with low incomes or a disability. “Private insurance” is defined as insurance through a current or former employer or union, insurance purchased directly from an insurance company, TRICARE or other military health care, or coverage through the Affordable Care Act or other private insurance.

SOURCE: 2021 and 2022 NSCH (CAHMI, 2024).

et al., 1998, para. 11; see also HRSA, n.d.a). The Children with Special Health Care Needs screener is used most commonly (Bethell et al., 2015, see Table 4-1).

The National Academies Committee on Improving Health Outcomes for Children with Disabilities (National Academies, 2018) defined “disability” as “an environmentally contextualized health-related limitation in a child’s existing or emergent capacity to perform developmentally appropriate activities and participate, as desired, in society” (National Academies, 2018, p. 23; see also Halfon et al., 2012). Its report notes also that the varied definitions and lack of a consistent framework led to different estimates of the size of the population of children with disabilities (Currie & Kahn, 2012; National Academies, 2018). In one estimate, the U.S. Census Bureau reports that the percentage of children in the United States with one of six types of functional limitations as a disability increased between 2008 and 2019, from 3.9% to 4.3%, to around 3 million children under age 18 (Young, 2021; Young & Crankshaw, 2021). In other surveys, an estimated 13–15% of children experience a larger range of functional difficulties that impact daily living (2020–2021 National Health Interview Survey; NSCH; see also Table 4-1).8

Government agencies that provide services for individuals with disabilities define “disability” in a way that is specific to their legislative mandate. For example, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (2004) defines disability more broadly than does the Social Security Administration (SSA), given the agencies’ disparate purposes. The Supplemental Security Income program, administered by SSA, provides cash support for children and other people with severe disabilities. To determine eligibility, SSA uses a combination of diagnoses with specific indicators of severity, along with some functional measures for people who may have severe disability but who do not meet the specific diagnostic criteria (National Academies, 2015). Given the complexity of multiple systems with different eligibility requirements, families face barriers and challenges in navigating the various programs that provide health, education, social, emotional, employment, and financial supports (National Academies, 2018).

___________________

8 The FCFS 2023 America’s Children report considers a child to be disabled if their daily activities are consistently impacted by any one of the 13 functional difficulties assessed through the 2020–2021 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), whether or not the child also experiences a diagnosed health condition. This method identifies 13% of children ages 5–17 as having a disability. The functional difficulties evaluated through the NSCH comprise a similar list as those used in the NHIS disability indicator. Yet, rather than label children as having a disability due to the presence of any functional difficulty, the NSCH identifies children with chronic conditions and special health care needs due to their condition and enables assessing whether or not these children also experience functional difficulties. Such a calculation results in identifying 15.2% of children ages 6–17 as having any chronic or lifelong health condition that requires above-routine health care services and who also experience one or more functional difficulty.

Chronic Conditions

Rates and types of chronic conditions vary across populations. For example, immigrant children have a notably lower likelihood of having one or more chronic conditions compared with native-born children (Singh, Yu, & Kogan, 2013), with a prevalence of 6.8% in Asian immigrant children, compared with 30.6% in native-born non-Hispanic Black children. Children living in English-speaking households are more than twice as likely to have a mental, emotional, or behavioral health diagnosis than those living in non-English-speaking households. Hispanic children have higher rates of obesity; dental caries; and some congenital conditions, such as spina bifida (Berry, Rock et al., 2013; Ogden et al., 2020; Palfrey et al., 2004). For some chronic conditions, such as autism spectrum disorder, rates of diagnosis continue to increase, in part because of better awareness of these conditions and improvement in screening practices.

Substantial variations are also observed consistently in the prevalence of chronic health conditions across communities, and these variations remain after adjusting for differences in the sociodemographic characteristics of children across states and align with variations in access to and quality of health care services and systems (Bethell et al., 2014; Blumberg et al., 2010). The severity of chronic health conditions varies across conditions, impacted by underlying medical factors, natural variation, the quality of health services children receive, and a range of social and environmental factors (Bethell et al., 2014).

Five conditions of high prevalence provide examples of how chronic conditions affect children and families and often persist into adulthood: asthma; overweight and obesity; neurodevelopmental conditions; mental, emotional, and behavioral health disorders; and substance use disorders. There are notable disparities in prevalence, outcomes, and care management for each condition. Certain populations, such as children in foster care and those in contact with the juvenile justice system, have elevated rates of chronic conditions, particularly mental, emotional, and behavioral health disorders. A high proportion of children and youth in foster care and those incarcerated have lapses in preventive care and unmet physical, developmental, and mental health needs. This is often the result of frequent changes in living situations and disruptions in continuity of care and access to health care coverage (Barnert et al., 2020; Committee on Adolescence, Braverman, & Murray, 2011; Deutsch & Fortin, 2015; Owen et al., 2020).

These conditions are preventable or manageable and offer opportunity for policy interventions and cross-sector collaboration. It is also important to recognize that among children with any one chronic condition most experience another condition as well. For example, 77% of children with asthma and most children with depression (93.5%) also experience at least one other condition (CAHMI, 2024). Common comorbidities have led to health care system efforts to integrate pediatric health care and related services.

Asthma

Asthma, a chronic lung disease, can affect people of any age, but it is one of the most common chronic conditions for children (WHO, 2023). In 2021, 6.5% of children under age 18 years were estimated to have an asthma diagnosis (CDC, 2023a; Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, n.d.), with wide variation across population groups, from 3.3% of Asian-American children to 5.9% of Hispanic children, to 11.6% of Black children (CDC, 2021d). With good care, most children manage their asthma well. However, if not properly managed, children may require emergency department visits and hospitalizations. In 2021, approximately 38.7% of children in the United States under age 18 years with asthma had one or more asthma attacks in the past 12 months (Elflein, 2023). This statistic underscores the persistent challenges in achieving optimal control over this chronic respiratory condition among the pediatric population. Data on asthma are collected through a variety of methods, leading to robust asthma surveillance across the country, including prevalence, medications used, emergency room visits, and days of work or school lost.

Many studies document disparities in asthma medication use (Amin et al., 2020; McQuaid, 2018), health care utilization (Fitzpatrick et al., 2019), and outcomes in low-income and racial/ethnic minority patients (Federico et al., 2020; Perez & Coutinho, 2021; Redmond et al., 2022). These disparities led to the creation of a federal task force to examine root causes and recommend remediations. The task force recommended controlling environmental exposures to air pollutants and environmental hazards, and improving access to care for communities with high asthma prevalence (Environmental Protection Agency [EPA], 2012). Current efforts to address environmental asthma triggers involve controlling environmental factors in schools, homes, and communities (EPA, 2012; Matsui, Abramson, & Sandel, 2016).

Asthma is a leading cause of school absenteeism (Qin et al., 2022). Students with asthma miss an average of 2.3 more days of school each year than those without asthma. Asthma is the most common cause of pediatric emergency department use (Butz et al., 2013; CDC, 2023c; Yoong et al., 2021). Morbidity remains high, especially among inner-city children (Butz et al., 2013; Poowuttikul, Saini, & Seth, 2019). Poor urban communities face higher rates of pollution and infestations that can exacerbate asthma, as well as other characteristics associated with higher rates of asthma (Aryee et al., 2022).

Overweight and Obesity

CDC (2024f,g) defines “obesity” as having a body mass index (BMI) greater than or equal to the 95th percentile for children overall. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (Fryar, Carroll, & Afful, 2020) indicate that nearly two in five children ages 2–19 (almost 40%) have obesity, a rate that has increased greatly from 13.9% in 2000. An additional 16% are “overweight,” defined as having a BMI between the 85th and

95th percentiles (Fryar, Carroll, & Afful, 2020). Rates of being overweight are highest among Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black children (26.2% and 24.8%, respectively; CDC, 2024e,f). The COVID-19 pandemic worsened the obesity epidemic, especially among children (World Obesity Federation, 2023). Childhood obesity has been linked to higher increased total medical costs, outpatient visit costs, and hospitalization costs than childhood overweight. By 2050 the annual direct costs related to childhood obesity will be $13.62 billion and the indirect health care costs will be $49.02 billion (Ling et al., 2023).

A complex interplay of genetic, environmental, and socioecological factors affects the development of obesity (Aris et al., 2022; Hampl et al., 2023), and higher rates are associated with low socioeconomic status, exposure to adverse childhood experiences, and high needs related to other social determinants of health (Bethell et al., 2014; Hampl et al., 2023). Contributing factors include food insecurity, restricted availability of healthy food choices, limited time and access to opportunities for physical activity and recreation, and discrimination and stigma (Williams, Burns, & Rudowitz, 2023). Notably, the rate of obesity continues to increase for children in low-income households (Hampl et al., 2023; Iacopetta et al., 2024; Lange et al., 2021). Obesity is associated with increased prevalence of later serious conditions, including hypertension, diabetes, metabolic dysfunction–associated fatty liver disease (previously termed “nonalcoholic fatty liver disease”), and obstructive sleep apnea (Dietz et al., 2015; Hampl et al., 2023).

U.S. children have low rates of physical activity, exacerbating the obesity epidemic. In 2021, over 54% of high schoolers said they were physically active for less than 60 minutes for 5 days of the week. Nearly 16% were physically active for less than 60 minutes on just 1 day (CDC, 2021c). According to 2021 NSCH data, only 20.3% of children ages 1–5 years experience at least five of the six evidence-based health behaviors associated with childhood obesity prevention, including daily consumption of fruits and vegetables, sufficient sleep and outdoor play, limited consumption of sugary drinks, and less screen time (HRSA, 2023k). This number increased to 30.7% for children living in households with incomes 400% or more above the federal poverty level (HRSA, 2023k). Children covered by Medicaid are more than twice as likely to experience obesity compared with those with private insurance: 26.0% of Medicaid-enrolled children have obesity, in contrast to 11.4% among children with private insurance alone (Estabrooks & Shetterly, 2007).

Obesity is a serious public health issue, associated with both immediate and long-term health problems (BeLue, Francis, & Colaco, 2009; Dietz, 1998; Ebbeling et al., 2002; Freeman, Walker, & Vrana, 1999; Gilliland et al., 2003; Luppino et al., 2010; Reilly et al., 2003). Children with obesity are five times more likely to be obese in adulthood and experience elevated risk for other illnesses and early death (Ferraro, Thorpe, & Wilkinson, 2003; Simmonds et al., 2016; Tsoi et al., 2022). Severe obesity was more common among individuals aged 40–59 than other age groups (Hales et al., 2020).

Neurodevelopmental Conditions

Neurodevelopmental conditions affect cognition, communication, behavior, and/or motor skills, stemming from irregularities in brain development (Mullin et al., 2013); they include intellectual disabilities, communication disorders, autism spectrum disorder, specific learning disorders, and movement disorders (Cainelli & Bisiacchi, 2023).

Autism spectrum disorder, a lifelong developmental disability, is associated with difficulties with social communication and interaction, and repetitive or restricted behaviors or interests, affecting one’s learning, cognitive organization, attention, and adaptive skills (Drmic, Szatmari, & Volkmar, 2017). Diagnoses of autism spectrum disorder have increased in recent decades, and prevalence of diagnoses among children has risen markedly in the United States between 2000 and 2020—in 2020 an estimated 2.8–3.5% of children were identified as having autism spectrum disorder (Li et al., 2022b; Maenner et al., 2023; Rice et al., 2012).

Autism spectrum disorder is almost four times more common among boys than among girls (Maenner et al., 2023). Before 2016, more White children than Black or Hispanic children were diagnosed with autism by age 8 years (CDC, 2019c, 2023g). However, these disparities have decreased, with no overall difference observed in the percentage of Asia Pacific or Pacific Islander, Black, Hispanic, or White children identified with autism by age 8 in 2018. In 2018, however, a new trend emerged, with higher rates of 4-year-old Black and Hispanic children diagnosed with autism compared with their White counterparts (CDC, 2019c, 2023g). This pattern persisted in 2020 among 4-year-olds and was noted for the first time among 8-year-olds. These findings suggest potential advances in autism awareness, identification, and access to services for Black, Hispanic, and Asia Pacific children, indicating a need to investigate factors such as social determinants of health that may contribute to higher disability rates in historically underserved populations (CDC, 2019c, 2023g). Autism spectrum disorder presents with a diverse range of characteristics, including onset, symptoms, and severities, with needed variation in appropriate health care (Malik-Soni et al., 2022). Many children with autism also have ADHD, adding complexity to health and educational interventions (Zablotsky et al., 2023).

Intellectual and developmental disabilities constitute a broad group of differences that are usually present at birth and affect the trajectory of the individual’s physical, intellectual, and/or emotional development (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [NICHD], n.d.). Intellectual disability starts any time before age 18 years and involves limitations to both intellectual functioning or intelligence (e.g., ability to learn, problem solve) and adaptive behavior (e.g., everyday social and life skills). Developmental disabilities include a broader category of often lifelong challenges that can be intellectual, physical, or both. The term “intellectual and developmental disabilities” is often used to describe situations in which

both intellectual disability and other disabilities are present (NICHD, n.d.). Children with these disabilities from historically marginalized and ethnic backgrounds often encounter barriers to care related to negative social determinants of health, leading to unfavorable health outcomes (Magaña, Heydarian, & Vanegas, 2022; Parish et al., 2013).

Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Health

Concerns with children’s mental, emotional, and behavioral health have been growing in recent years, with greater recognition of its contribution to child wellbeing (see Chapter 2; see also Shim & Compton, 2020; Whitney & Peterson, 2019). Children’s mental health conditions are typically characterized by disruptions or alterations in thinking, behaviors, social skills, or emotional regulation (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP], 2021a; CDC, 2024q). These challenges interfere with the ability to function effectively at home, in school, or in other social settings. Common childhood mental health disorders include ADHD, anxiety (manifesting as fears or worries), depression, substance use, and behavior disorders (Bethell, Garner, et al., 2022; CDC, 2024q). In 2018–2019, 13.2% of U.S. children ages 3–17—just over 8 million—had a diagnosis of at least one of the following: depression, anxiety, ADHD, or a behavioral or conduct disorder (Census Bureau, 2024), with somewhat higher rates for non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black children. The conditions diagnosed most often were ADHD and anxiety, each affecting approximately 1 in 11 children (CDC, 2024r).

More than 19% of adolescents (ages 12–17) reported a major depressive episode in the past year (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2022a,b); 13.5% had serious thoughts of suicide, with 6.5% making a suicide plan, and nearly 4% attempting suicide. From 2019 to 2021, female adolescents had increased prevalence of seriously considered suicide (from 24.1% in 2019 to 30% in 2021), an increase in making a suicide plan (from 19.9% to 23.6%), and an increase in suicide attempts (from 11.0% to 13.3%; CDC, 2024k).

Typically, ADHD is first diagnosed in childhood and often persists into adulthood (Nigg et al., 2020; Salari et al., 2023; Wilens & Spencer, 2010). In 2018, nearly 10% of children ages 3–17 years had a diagnosis of ADHD (CDC, 2018). For Black children, this number was nearly 13%, but for Hispanic children, it was less than 7%, and for Asian children it was only 3.2%. Many evidence-based pharmacological and psychosocial treatments for ADHD exist, with increased utilization linked to enhanced acute and long-term outcomes (Baweja, Soutullo, & Waxmonsky, 2021); nonetheless, long-term results are often less optimal, as many individuals do not access multimodal treatments and many stop care prematurely (Froehlich & Brinkman, 2018; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2018; Wolraich et al., 2019). Over the life course, ADHD increases the risk for serious secondary mental health issues, such as substance use disorder,

depression, psychosis, and anxiety. The condition also affects life outcomes such as school and occupational underachievement, unemployment, poor overall health, housing instability, injuries, and suicide (Agnew-Blais & Seidman, 2013; Forte et al., 2020; Groenman, Janssen, & Oosterlaan, 2017; Kessler et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2011; Nigg et al., 2020).

The many children with mental health challenges face difficulty obtaining necessary diagnostic and treatment services (CDC, 2023e). Adolescents are more likely to receive any form of mental health treatment than younger children, although less than 20% in either group received services (Zablotsky & Ng, 2023). Across the lifespan, mental health and mental disorders are often comorbid with physical conditions and chronic diseases (Bitsko et al., 2022; Merikangas et al., 2015), indicating the need for integrated services that address both physical and mental health needs of children and youth (Arrojo et al., 2023; Catalano & Kellogg, 2020).

Mental and behavioral health conditions are often chronic. Half of all lifetime cases start by age 14 years and three-fourths start by age 24 years (National Research Council & IOM, 2009). Childhood mental health problems, if not addressed, may persist into adolescence and adulthood. Adverse childhood experiences, such as trauma or neglect, can further exacerbate mental health challenges (Ceccarelli et al., 2022). An accumulation of adverse childhood experiences raises the likelihood of developing psychopathology in adulthood, along with impairments in social functioning (Gu et al., 2022).

Substance Use Disorders

The initiation of substance use is common during adolescence and emerging adulthood. After seeing a decrease in youth substance use between 2020 and 2021, in 2022 substance use rates either remained stable (cannabis use and nicotine vaping) or returned to prepandemic levels (alcohol use). Rates of use vary by age with 15% of 8th graders and 52% of 12th graders using alcohol within the last 12 months (Miech et al., 2023). For some youth, early substance use can become problematic and result in substance use disorders as early as during adolescence and early adulthood.

Substance use disorders include the misuse or excessive use of drugs or alcohol (Nationwide Children’s Hospital, n.d.b; Thomasius, Paschke, & Arnaud, 2022) and are prevalent among adolescents, spiking during early adulthood. According to the 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, more than 17.3% of people (48 million) aged 12 and older had a substance use disorder in the previous year (SAMHSA, 2022a,b). Young adults ages 18–25 had the highest rates (25.6% or 8.6 million) of past-year substance use disorders, including binge drinking in the past month and heavy alcohol, marijuana, or prescription pain medication abuse. And 8.5% of adolescents ages 12–17 reported having a substance use disorder (2.2 million people; SAMHSA, 2021). Among youth, alcohol use disorder is the most common type, followed by marijuana use disorder. Prevalence of misuse of

prescription pain relievers among adolescents ages 12–17 was 1.9% and 3% among young adults ages 18–25 (SAMHSA, 2021). Beyond those diagnosed with substance use disorders, many more young people use substances regularly, an opportunity for prevention before use becomes a disorder. Among people aged 12 or older in 2022, nearly 60% (168.7 million) used tobacco products, vaped nicotine, used alcohol, or used an illicit drug in the past month (“current use”; SAMHSA, 2022a,b,d).

Rates vary among population groups, with illicit drug use disorder higher among those reporting two or more races (5.0%) and among American Indian/Alaska Native individuals (4.8%; Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2021). American Indian/Alaska Native individuals had higher rates of alcohol use disorder (8.3%) than other racial/ethnic groups; White individuals had higher rates (5.8%) than Black, Hispanic, and Asian individuals (4.8%, 5.2%, and 3.3%, respectively).

Substance use disorders often coexist with mental health conditions such as depression or anxiety (Alsheikh et al., 2020; Perrin et al., 2019). In 2021, nearly 4% of adolescents (ages 12–17) had both a substance use disorder and a major depressive episode in the previous year, with most reporting severe impairment to ability to function. Higher rates were found among multiracial, Hispanic, and White adolescents than among Black adolescents (SAMHSA, 2021). Adolescents with a past-year major depressive episode were more likely (27.7%) than their peers without such an episode (10.7%) to use illicit drugs, including marijuana use (20.3% vs. 8.0%; SAMHSA, 2021) and to binge alcohol and use tobacco products in the past month.

Addressing substance use in childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood through prevention, early identification, and treatment is crucial for their health and wellbeing (Camenga et al., 2022; Fadus et al., 2019; HHS, 2016; Hsiung et al., 2022). Failure to intervene early or provide age-appropriate substance use services can lead to significant and long-term adverse consequences for individuals and families, and across generations (Straussner & Fewell, 2018).

Typically, initial substance use begins during childhood or adolescence (Bahl et al., 2023; Forouzanfar et al., 2015). Individuals who initiate substance use at an early age face elevated risks of psychosocial problems across multiple life domains—including behavior patterns, psychiatric disorders, family dynamics, peer relationships, leisure and recreation, and work adjustment—compared with those who start substance use later in life (Poudel & Gautam, 2017). Promisingly, programs aimed at preventing adolescent substance use have the potential to cultivate lasting individual and interpersonal resilience factors (Camenga et al., 2022; Feinberg et al., 2022). These factors not only enable participants to navigate unforeseen periods of acute stress and adversity but also contribute to the wellbeing of both participants and their future children, with reduced deterioration in health and overall wellbeing.

Leading Causes of Mortality and Injury

Childhood mortality rates had decreased for decades until 2020, when the all-cause mortality rate for those between ages 1 and 19 increased by nearly 11% from the previous year (Woolf, Wolf, & Rivara, 2023). It then rose another 8.3% between 2020 and 2021. Although COVID-19 played an important role, the increase can be attributed mainly to injuries, including suicide, homicide, drug overdoses, transportation-related deaths, and fires or burns (CDC, 2021c; Woolf, Wolf, & Rivara, 2023). In 2020, the absolute increase in injury deaths alone for ages 1–19 was nearly 12 times higher (2.80 deaths per 100,000) than the mortality rate due to COVID-19 (0.24 deaths per 100,000; Murphy et al., 2021). Among children ages 1–9, injuries explained two-thirds (64%) of the increase in all-cause mortality in 2020. Suicide is the second-leading cause of death among children ages 10–14 and the third leading cause of death, behind homicide, for youth ages 14–18 years (Woolf, Wolf, & Rivara, 2023).

These risks and rates differ across population groups, with greater increases in injuries among males. Non-Hispanic Black youths accounted for nearly 63% of homicide victims ages 10–19 in 2020 (Woolf, Wolf, & Rivara, 2023). Notably, as well, the child mortality rate in the United States has been higher than other wealthy nations since the 1980s (Thakrar et al., 2018). This section continues with a focus on the top contributors to child mortality and injury: infant mortality, gun violence, self-harm and suicide, and child abuse and domestic violence.

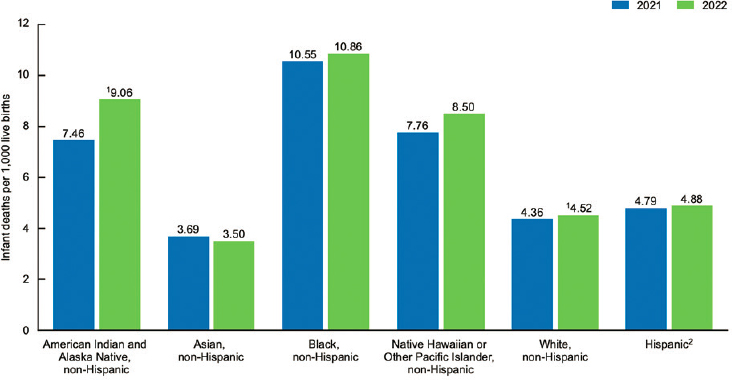

Infant Mortality and Low Birth Weight

According to CDC, in 2022, the United States had 20,538 infant deaths, a 3% increase from 2021 (Ely & Driscoll, 2022), representing 5.6 infant deaths per 1,000 live births, with variation across the states. In 2019, Massachusetts had the lowest rate at 3.8 deaths per 1,000 live births and Mississippi had the highest at 8.6 deaths per 1,000 live births. Similar to maternal mortality, infant death rates also differ by race (see Figure 4-4). Leading causes of death were typically related to maternal complications and bacterial sepsis of newborns (Ely & Driscoll, 2022). Other causes include low birth weight, circulatory system diseases, unintentional injury, and respiratory distress of the newborn. The United States has around 3.6 million live births annually, with approximately 10% categorized as preterm births (delivery before 37 weeks gestational age; WHO, n.d.b) and 8–9% as low birth weight (less than 2,500 grams or 5.5 pounds; Hamilton, Martin, & Osterman, 2023; National Academies, 2023f; Osterman et al., 2023). Most infants born preterm or with low birth weight have no severe developmental impairments; however, some may experience increased rates of mild to moderate chronic health issues, such as cognitive and behavioral

NOTES: (1) The increased rate for American Indian and Alaska Native, non-Hispanic, is significantly different from 2021. (2) Infants of Hispanic origin may be of any race.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System, linked birth/infant death file (Ely & Driscoll, 2022).

impairments, ADHD, autism spectrum disorder, cerebral palsy, hearing loss, vision loss, and chronic lung disease. These conditions can have significant functional impacts throughout the life course (Busque et al., 2022; National Academies 2023e; Orchinik et al., 2011).

Injury and Gun Violence

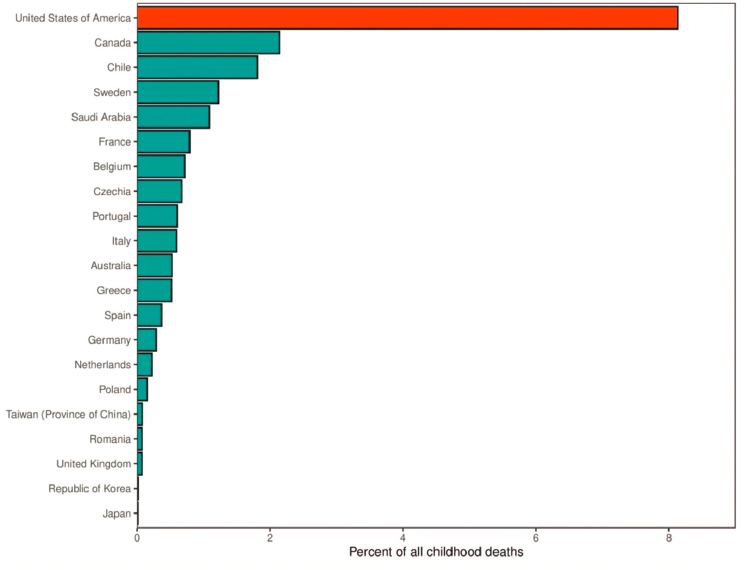

Nearly half of the increase in all-cause mortality in children has resulted from firearm-related injuries, the leading cause of death among young people ages 1–19 (CDC, n.d.d; Goldstick, Cunningham, & Carter, 2022; Woolf, Wolf, & Rivara, 2023) and more than 8% of U.S. deaths for those under the age of 20 (Leach-Kemon, Sirull, & Glenn, 2023). When infants less than 1 year of age are excluded, this number jumps to 15% of all deaths under age 20.

The United States also has experienced record levels of school shootings and mass shootings, which have become more deadly since the turn of the century (Mariño-Ramírez et al., 2022). In 2018–2019 alone, more than 100,000 children attended a school where a shooting took place (Mariño-Ramírez et al., 2022). School shootings occur in the United States 27 times more than all other major industrialized nations combined. These events have lasting impacts on children and adolescents, who are more likely to

abuse drugs and alcohol, suffer from mental illness, and engage in criminal activity (Finkelhor et al., 2009). Students who experience these events are also less likely to graduate high school, attend college, and graduate college; are less likely to be employed; and are more likely to have lower earnings into adulthood (Rossin-Slater, 2022). The toll of gun violence is both human and financial, with about $1 billion spent each year treating gunshot wounds, more than 50% of which was paid by Medicaid (Government Accountability Office, 2021). Compared with similar countries, the United States is an extreme outlier in childhood deaths (see Figure 4-5; Leach-Kemon, Sirull, & Glenn, 2023). Age-adjusted firearm homicide rates in the United States are 33 times greater than in Australia and 77 times greater than in Germany.

However, the risk of death from firearms is not evenly distributed around the country, and deaths due to firearm injuries occur disproportionately for children living in poverty and children from historically marginalized groups. Black children and adolescents accounted for approximately 46% of youth

SOURCE: Scott Glenn, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (Leach-Kemon, Sirull, & Glenn, 2023).

firearm deaths in 2021 (Mariño-Ramírez et al., 2022; Panchal, 2022). Specifically, gun-related deaths are highest among non-Hispanic Black youth ages 10–19, with rates doubling from 2018 to 2021, following a modest decrease in 2018 (Mariño-Ramírez et al., 2022; Panchal, 2022). The firearm suicide rate among young people has increased to its highest rate in more than 20 years, with White youth ages 10–19 and American Indian/Alaska Native youth having the highest rates of suicide (Everytown Research & Policy, 2022). Although not as high as rates among White youth, rates of suicide among Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black youth have also increased since 2018 to their highest level (AHRQ, 2022a; CDC, 2023b, 2024k).

Compounding the dire problem of child deaths by firearms, almost 6,000 additional children and adolescents each year suffer injuries and disabilities from guns (Sun et al., 2022). Health care settings have been on the front line in coping with the immediate aftermath of firearm injuries (Sakran & Bulger, 2023). Emergency room visits, trauma surgeries, and rehabilitative services related to firearm injury have all increased. In addition, there is a growing recognition of frontline health care workers dealing with firearm victims as secondhand victims themselves, with associated stress, emotional reactivity, and burnout (Elwell, Krichten, & Mattocks, 2015; Ozeke et al., 2019; Salston & Figley, 2003).

Self-Harm and Suicide

Self-harm includes both suicide and other situations in which individuals intentionally hurt themselves without the intention of ending their lives (Klonsky, 2007; Klonsky, Victor, & Saffer, 2014; Nock & Favazza, 2009). The latter conditions have been labeled “nonsuicidal self-injury,” describing cutting and other forms of self-harm (AAP, 2023). Nonsuicidal self-injury occurs most commonly among adolescents and young adults (UNICEF, n.d.), potentially as a means for children to assert control over their bodies in situations where they perceive a lack of control or feel overwhelmed (Hampl et al., 2023). While nonsuicidal self-injury can lead to suicidal behaviors, it is often a coping tool used to feel better rather than an attempt to end one’s life (Whitlock & Lloyd-Richardson, 2019).

Suicide is a serious public health problem, responsible for more deaths among youth ages 10–24 years than any single major medical illness (AAP, n.d.; Asarnow, 2020). Suicide risk arises from a complex interplay involving underlying psychiatric conditions, family history of mental disorders, and family conflicts; it can be mitigated with support from friend networks and access to outpatient psychiatric resources. Specific life events such as interpersonal losses, academic stress, bullying, and physical/sexual abuse can set off a suicide attempt (CDC, 2021c, 2024k; Sekmen et al., 2023). Nonfatal attempts are more common, with roughly 100–200 suicide attempts for

every suicide death. The suicide rate for people ages 10–19 increased by 56% between 2007 and 2016 (Curtin et al., 2018; Lindsey et al., 2019). Adolescent boys complete suicide three times more often than girls, although girls make twice as many attempts (Miranda-Mendizabal et al., 2019). American Indian and Alaska Native males have the highest suicide rate, and Black females have the lowest (Shain et al., 2016).

FAMILY, CAREGIVER, AND COMMUNITY HEALTH

Parental, household, and community factors all influence children’s health and wellbeing.

Maternal Health

The first 1,000 days of development, from conception to age 2 years, is a particularly critical period. It is a time of incredible growth and development, crucial for the development of all body systems, such as the brain, metabolism, and immune system (Likhar & Patil, 2022). Nutrition, relationships, and physical environment during this time have long-term effects on the child’s health, development, and wellbeing. The health of mothers is a critical determinant to children’s health trajectory (De Genna et al., 2007; National Academies, 2019d). However, after many years of decline, rates of maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States have increased in recent years (Fleszar et al., 2023). The risk of death related to pregnancy and childbirth in the United States more than doubled between 1999 and 2019 (Fleszar et al., 2023). The United States is one of the only countries with an increase in this indicator in the past few decades, with mortality rates more than double that of similar countries, such as Canada, France, and Sweden, in 2018 (Kennedy-Moulton et al., 2022). Dramatic disparities in mortality exist between Black mothers (69.9 deaths per 100,000 live births) and those who identify as non-Hispanic White (26.6 per 100,000) and Hispanic (28 per 100,000; Joseph et al., 2021). In addition, approximately 60,000 women experience severe morbidity from labor and delivery each year, affecting their physical and mental health and making it difficult to provide the nurturing and healthy environment their child needs (Declercq & Zephyrin, 2021; Flagg et al., 2023). The 2020–2021 NSCH indicates that only 60% of children ages 0–17 have mothers who rate their overall physical and mental health status as being excellent or very good, with variation across racial/ethnic subgroups of children. For example, Hispanic (54.5%) and Black (55.2%) children are the least likely to have mothers reporting excellent or very good physical and mental health. Racial and ethnic variations are largely driven by physical health status differences, with more consistent reporting across subgroups on mental health status (Williams, 2018).

Community Health Crises

The recent opioid crisis is another example of a health phenomenon that has significantly affected U.S. children and families over the past decade. In 2019, 1.4 million children and adolescents lived with a parent with an opioid use disorder (Brundage & Levine, 2019). These children are at increased risk for being removed from the home and having a parent incarcerated because of opioids. Additionally, children of parents with a substance use disorder are more likely to experience maltreatment (Kepple, 2018). Parents also may overdose, with growing rates in recent years. Children of parents who overdose experience further consequences from bereavement, including an increased incidence of depression, primarily during the first 2 years, along with PTSD and functional impairment (Hulsey et al., 2020; Pham et al., 2018). It is estimated that by 2030, the cumulative lifetime cost of the “ripple effect” of the opioid crisis on children will be $400 billion (Brundage & Levine, 2019), based on additional spending in health care, special education, child welfare, and criminal justice.

Similarly, the COVID-19 pandemic affected parent and caregiver mental health, which increased difficulties coping with parenting demands (Hartley et al., 2021). In addition, during the pandemic, more than 229,000 children lost one or both parents due to COVID-19; 252,000 lost a primary caregiver; and 291,000 lost a primary or secondary caregiver (Hillis et al., 2021). Families and communities of color, including tribal communities, experienced the negative impact of these losses disproportionately. Compared with White children, American Indian and Alaska Native children were 4.5 times more likely to lose a parent or primary caregiver; Black children were 2.4 times more likely; and Hispanic children were nearly twice as likely (Coker et al., 2023; Hillis et al., 2021; National Academies, 2023c).

Relational and Social Health Risks

For some children, the home context and living conditions present social and relational health risks. Social health risks for children include economic hardship, food insecurity, living in unsafe neighborhoods with exposure to violence, and experiencing discrimination due to race or ethnicity. Over one-quarter of U.S. children and youth experience one or more of these risks, and more than 40% of those with chronic conditions face these risks (Bethell, Blackwell et al., 2022; Bethell, Garner et al., 2022).9 Relational

___________________

9 The Social Health Risk Index identifies children who sometimes or often could not afford enough food to eat; somewhat often or very often found it hard to cover the costs of basics needs, including housing; lived in an unsafe neighborhood or where the child was a victim of or witnessed violence; and witnessed their child being treated or judged unfairly due to his or her race or ethnic group (CAHMI, 2024).

health risks for children include having two or more adverse childhood experiences in the home environment, low parental coping, insufficient caregiver emotional support, and high levels of parental aggravation with their child (Merrick et al., 2019). Nearly 40% of U.S. children and more than 50% of children with chronic conditions experienced one or more of these risks (Bethell, Blackwell et al., 2022; Merrick et al., 2019).10 These findings and other studies link both social and relational health risks to higher prevalence of poor physical and mental health (Bitsko et al., 2022; Ghandour et al., 2018; O’Loughlin et al., 2022; Umberson & Montez, 2010) and point to the value of mitigating negative impacts of home contexts and living conditions. Studies on national trends in child wellbeing find that poor caregiver mental health and lower parental coping (both relational health risks) have increased in recent years (2016–2020) and household-based adverse childhood experiences (e.g., alcohol/substance abuse, domestic violence) have remained consistently high for all children (31.3% in 2021; Ceccarelli et al., 2022; Cree et al., 2018; Hutchins et al, 2022; Lebrun-Harris et al., 2022; O’Loughlin et al., 2022; Swedo et al., 2023).

Family and domestic violence affect approximately 10 million individuals each year, including child abuse, intimate partner violence, and elder abuse (Huecker et al., 2024). In 2020, 1,750 children in the United States died as a result of abuse and neglect (CDC, 2022b). Domestic violence can include economic, physical, sexual, emotional, and psychological abuse directed toward children, adults, or elders, and can lead to deteriorating psychological and physical health, reduced quality of life, diminished productivity, and mortality. Parents or caregivers involved in a turbulent relationship may think that the relationship does not affect their children; however, even children shielded from witnessing domestic violence can experience distress because of familial conflict (American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 2023; Office on Violence Against Women, 2023). Child abuse and exposure to domestic violence increase the risk of emotional and behavioral issues in children. Children living in poverty are more susceptible to abuse and neglect because of the stress associated with poverty (CDC, 2022b). Low-income families have child maltreatment rates five times higher than those of other families. The economic impact of child abuse and neglect in the United States was approximately $592 billion in 2018, rivaling the costs of prominent public health problems such as heart disease and diabetes (CDC, 2022b).

___________________